Oxford University Press's Blog, page 684

March 27, 2015

Affirmative action for immigrant whites

In mid-February the Public Broadcasting Service aired a four-hour documentary entitled The Italian Americans, an absorbing chronicle of one immigrant group’s struggles and successes in America. It has received rave reviews across the country. For all its virtues, however, the film falls short in at least one important respect: while it claims to overcome “the power of myth” to tell the “real history of Italian Americans,” that history is at best incomplete. To be sure, the documentary captures an important part of the story: the grinding poverty and prejudice that many Italians overcame to reach the “highest echelons of American society,” and the grit, determination, courage, and hard work that helped make this epic rise possible.

But this rise had another, critical source that is too often missing from popular memory about Italian and other European immigrants’ success in America: white privilege. The truth is that these immigrants entered a country with a long, bloody history of drawing deep and distinct color lines — chasms, really — between people socially-defined as white and everyone else, and then assigning rights and resources, power and privilege, accordingly. True, some Americans debated for a time where exactly to place Italians and other Europeans in relation to these lines. At a hearing for the House Committee on Immigration, in 1912, a Pennsylvania congressman wondered whether the “south Italian” constituted a “full-blooded Caucasian.” But, with very few exceptions, European immigrants, Italians included, lived and built their lives on the white side of these color lines. It made all the difference in the world.

It allowed them, first, to become US citizens. During the period of mass European immigration, the right to naturalize was reserved solely for “free white persons” and, after the Civil War, for people of African nativity and descent. And while US courts and government officials in this period routinely blocked Asian immigrants’ efforts to become citizens, they never did so for European newcomers. As a result, migrants from places like Italy, Germany, Poland, and Russia always had relatively easy access to citizenship and, eventually, to its broad range of concrete benefits — voting power, government jobs, and, depending on state law, the ability to own land or to work in certain occupations or to serve in public office.

As Italian and other European immigrants settled throughout the United States, their white racial status came to matter monumentally in other ways as well. Today, it is too often forgotten that the urban North of the interwar years, where most Italian and other European immigrants lived, had its own extensive Jim Crow system of sorts. In Chicago, for example, a black-white (and sometimes white-nonwhite) color line wended its way through nearly every imaginable aspect of city life — hospitals and day care centers, camps and schools, nursing homes and YMCAs, workplaces and unions, churches and settlement houses, bars and cafes, roller rinks and billiard halls, swimming pools and beaches, neighborhoods and public housing projects. In concrete terms, this meant that Italians, and everyone on the white side of these lines, enjoyed immense advantages when looking for work, joining a union, buying a home, attending school, receiving medical care, even relaxing on one’s day off — that is, when making the big and small decisions that fashion a life.

Emigrants coming up the board-walk from the barge, which has taken them off the steamship company’s docks, and transported them to Ellis Island. Public domain via the Library of Congress.

Emigrants coming up the board-walk from the barge, which has taken them off the steamship company’s docks, and transported them to Ellis Island. Public domain via the Library of Congress.By the 1930s and 1940s, these white advantages only became more deeply entrenched on a national scale. Southern Democrats’ control of Congress meant that many New Deal laws, which built postwar middle class America, contained subtle clauses that channeled hundreds of billions of dollars in government benefits toward whites. Whether it was low-interest home loans or unemployment insurance, Social Security retirement funds or GI Bill benefits, the New Deal amounted to, in the phrase of political scientist and historian Ira Katznelson, “affirmative action for whites.” (An extreme version of affirmative action, it should be emphasized, since none of the more recent programs designed to offset centuries of racism ever came close to distributing resources on the sweeping scale of these New Deal programs.)

But it was affirmative action for immigrant whites, too, sometimes especially so. In a groundbreaking recent study, sociologist Cybelle Fox found that, unlike today, New Dealers often intentionally made welfare programs available to immigrants — particularly European immigrants — regardless of their citizenship or even their legal status. She discovered, furthermore, that European immigrants like Italians were at times New Deal programs’ biggest beneficiaries. Regarding Social Security, which initially failed to cover certain types of work (in which, not coincidentally, African Americans were disproportionately represented), European immigrants were “more likely than even native-born whites to work in occupations covered by Social Security, and they were also more likely to be nearing retirement when the program was instituted. Consequently, they ended up contributing little to the system but by design benefited almost as much as those who would contribute their whole working lives. “For retirees of European origin,” she writes, “Social Security was more akin to welfare than insurance but without the means test and without the stigma.”

The point of highlighting this history is not to insist that European immigrants had it easy. They didn’t. Nor is the point that they had few of the favorable qualities — grit, determination, hard work — honored in The Italian Americans and in popular memory. Many did have these qualities, as did (and do) many immigrants from all backgrounds. The point, instead, is that they received countless advantages in America that nonwhites — foreign-born and native-born alike, especially blacks among them — did not. Those advantages deserve a central place in any honest recounting of European immigrant success in America.

And yet, despite the work of numerous scholars, too few people seem to know anything about them. For the last twenty years, one national poll has found that an overwhelming majority of American residents agree with the following statement: “Irish, Italian, Jewish, and other minorities overcame prejudice and worked their way up. Blacks should do the same without special favors.”

A much better understanding of “special favors” — and who got them — comes from a political cartoon that appeared in the Chicago Defender, a prominent black newspaper, in 1924. It featured an African-American man struggling to open an “equal rights” safe. In the background, Uncle Sam whispers to “the foreigner” (a man with stereotypically Italian features, incidentally — handle-bar mustache, dark, curly hair, dark eyes), “He’s been trying to open that safe for a long time, but doesn’t know the combination — I’ll give it to you.”

Featured image: Mulberry Street, the center of New York City’s Little Italy, ca. 1900. Public domain via the Library of Congress.

The post Affirmative action for immigrant whites appeared first on OUPblog.

Looking back at Typhoid Mary 100 years later

Typhoid Mary Mallon is one of the best known personalities in the popular history of medicine, the cook who was a healthy carrier of typhoid fever, who spread illness, death, and tragedy among the families she served with her cooking, and whose case alerted public health administrations across the world to this mechanism of disease transmission. Alongside John Snow and the Broad Street Pump, Mary and her germ are iconic figures in the history of diarrhoeal diseases, the bright side and the dark side, but both in their own way communicators of important lessons in public health and disease transmission.

Typhoid was a big killer in nineteenth century cities, and as an indigenous disease the world over wrought a quiet and continuous devastation that may have matched or even outstripped the more blatant global eruptions of cholera. It remained a problem in many places, including North America, until well into the twentieth century, and counted some famous victims: Virginia Woolf’s brother Thoby Stephen caught it in Greece, and died in 1906, the novelist Arnold Bennett succumbed after incautiously drinking tap water in Paris in 1931. Today, however, it is still a killer in developed countries, and remains a very real hazard in regions where drinking water supplies are subject to contamination, and where personal hygiene is poorly understood. Food and water may act as the vehicles of infection, but the source is always the excreta, either or both urine and faeces, of another human being, a sufferer or a survivor, a healthy carrier.

Yet typhoid is only the spearhead of a much larger problem. Diarrhoeal diseases still cause much human misery and death across the planet, and represent a serious economic problem everywhere. One of the major perpetrators of this is the typhoid family, typhoid’s lesser cousins, the Salmonella family, some 2,500 of them and counting. While typhoid itself seems to be exclusive to humans, its cousins can inhabit both human and animal guts, can survive in contaminated environments for considerable periods of time, and can travel the world on and in contaminated foodstuffs from lettuce, and seeded sprouts to tomatoes, melons, meat, fish, poultry, and other more unlikely seeming sources like raw milk and cheese. Like typhoid itself, these Salmonella can create carriers and they infect a wide range of creatures, from humans and domestic poultry and livestock, to rodents and reptiles. Salmonella Sam, the pet tortoise, is far from unknown in the annals of food poisoning. Most humans do not call in a doctor when suffering from food poisoning, and a great many have no idea that they have become carriers. Unless they practice scrupulous personal hygiene they will, like Mary Mallon, almost certainly go on to infect other people. That, dear reader, could be you. Nor are Salmonella the only infections to be spread in this way: large outbreaks of hepatitis A, for example, have been caused by contaminated frozen raspberries.

Mary Mallon in hospital. The New York American magazine, June 1909. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Mary Mallon in hospital. The New York American magazine, June 1909. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.For much of the twentieth century the Salmonella were thought to be the main food poisoning organisms in Britain and Europe, while in the USA botulism predominated until the 1930s, after which staphylococcal intoxications were considered the main culprits. In the late 1970s, however, this picture began to change as new microbiological techniques came into use. Known food poisoning bacteria and viruses now include campylobacter, cryptosporidium, giardia, E.coli 0157: H7, and norovirus. The world of diarrhoeal infections is very much more complex now than it was in 1970. Antibiotic-resistant strains of Salmonella began to appear in the 1980s, and recent research conducted on multi-drug resistant Salmonella strains emerging in Africa suggests that HIV/AIDS infections and their treatments have established new ecological niches favouring the development of these Salmonella. In this twenty-first century, in which emergent new forms of terrorism, extreme sectarian violence, religious intolerance, and imperialist national ambitions are emerging at a scarifying rate, concerns over Typhoid Mary’s successors may seem on the trivial side. Yet it is worth remembering that each incidence of diarrhoeal infection is also an individual act of bioterrorism. Salmonella Typhimurium was actually used as a terrorist weapon in the United States in 1984, and the report on the incident was suppressed for fear of copycat incidents until after the Sarin attack on the Tokyo underground in 1995. In failing to wash our hands after visiting the lavatory, or before preparing food and drink for the table, we are each of us in danger of inflicting serious distress on one or more fellow human beings. Mary Mallon did not set out to become a domestic terrorist, but in refusing to acknowledge her condition when diagnosed, and in persisting to follow her profession without safeguard, she became precisely that.

Heading image: Salmonella NIAID. National Institutes of Health, United States Department of Health and Human Services. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Looking back at Typhoid Mary 100 years later appeared first on OUPblog.

Heroes of Social Work

Few professions aspire to improve the quality of life for people and communities around the globe in the same way as social work. Social workers strive to bring about positive changes in society and for individuals, often against great odds. And so it follows that the theme for this year’s National Social Work Month in the United States is “Social Work Paves the Way for Change.”

This March, we recognize the humanitarians who have ‘paved the way for change,’ in the arts, politics, medicine, education, and social work. Drawn from the most recent biographies added to the Encyclopedia of Social Work, the following represents a small sample of the thousands of people who have changed the course of our future and our world for the better, leaving a legacy as significant and inspiring as Van Gogh’s breath-taking irises.

Image credit: Irises by Van Gogh. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Heroes of Social Work appeared first on OUPblog.

What is Corporate Social Responsibility?

What is Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) all about? Companies appear to be adopting new attitudes and activities in the way they identify, evaluate and respond to social expectations. Society is no longer treated as a ‘given’, but as critical to business success. In some cases this is simply for the license to operate that social acceptability grants. In others, companies believe that favorable evaluations by consumers, employees and investors (who are, after all, members of society) will improve business performance. In part these developments also arise from employees, investors and customers taking a greater interest in the social credentials of companies they work for, invest in, and buy from, what I call ‘the socialization of markets’.

Moreover, CSR has travelled from its North American home to become a concept understood and deployed in business worldwide. Yet this is not a ‘one size fits all’. Rather CSR tends to connect with prevalent ethical and legal expectations of business in different societies, often reflecting more ancient and pre-industrial ethical mainsprings of responsible business.

Thus, companies deploy CSR, in communities, in the workplace, in the environment, and markets, and also to address organizational challenges that these new agendas pose.

Whilst CSR presumes that corporations should and can take social responsibility, one of the most interesting developments in recent decades is that CSR has expanded from simple self-regulation by companies to a combination of self- and social regulation (e.g. by civil society, government, international agencies). As a result various CSR systems have emerged to guide companies in all manner of activities, from equal opportunities employment, to ethical sourcing and reporting of social, environmental and governance issues.

Nevertheless, CSR (that ‘ghastly acronym’ according to Virgin founder, Sir Richard Branson) is a source of much skepticism. Academics often dismiss it as ‘an oxymoron’. More serious critiques come from those who, like Milton Friedman, believe that through profit-maximization in free markets business best serves society. Secondly, critiques come from those who believe that the state, not business, is the proper provider of societal welfare.

Regarding the first criticism, it is assumed by most CSR writers that markets too often operate without companies taking proper account of their negative social and environmental impacts or ‘externalities’. So CSR provides systems by which companies can understand these and learn from best practice. It is also assumed by CSR writers that there can be market rewards for identifying social values and meeting them in a company’s products and services. So CSR can be profitable as well as a basis for compliance with social expectations that business should be ethical and legal.

Turning to the view that governments should regulate responsible business, it is assumed by most CSR writers that whilst governmental regulation may be important for responsible business, it can lack sensitivity to business circumstances and social agendas. So, social regulation of business through CSR is regarded as a complement to governmental regulation rather than as an alternative. As a result CSR is not only significant in business to society relations but also in understanding new features of ‘the way we are governed’.

There are, of course dangers and shortcomings in CSR. There is a risk of ‘greenwash’, whereby companies simply ‘talk’ CSR without ‘walking it’ in the expectation that this will be sufficient to win legitimacy and secure their social brand. However, companies that rely on marketing are likely to pay a high reputational price if they are exposed as be exposed as hypocrites. There are also CSR gaps, such as responsibility for political roles that companies perform, ranging from lobbying, to paying taxes, and to the responsibility for the provision of public goods (e.g. water, energy) or critical infrastructure (e.g. information and communications technology). And new social, environmental and governance challenges continually emerge bring the question about the nature and direction of business responsibility. So there is always unfinished CSR business.

Feature image credit: Singapore, by cegoh. Public domain via Pixabay.

This post originally appeared on The Business of Society on March 18, 2015.

The post What is Corporate Social Responsibility? appeared first on OUPblog.

March 26, 2015

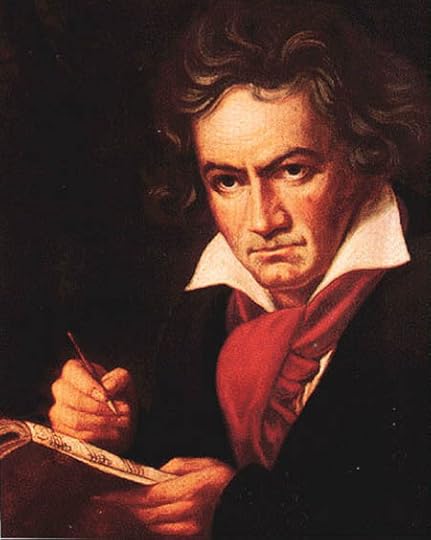

Beethoven’s diagnosis

Since Beethoven’s death on this day 188 years ago, debate has raged as to the cause of his deafness, generating scores of diagnoses ranging from measles to Paget’s disease. If deafness had been his only problem, diagnosing the disorder might have been easier, although his ear problem was of a strange character no longer seen. It began ever so surreptitiously and took over two decades to complete its destruction of Beethoven’s hearing.

Deafness, however, was but one of many health problems that plagued Beethoven throughout his lifetime. He suffered with intermittent episodes of abdominal pain and diarrhea from early adulthood until his death at age 56. Beginning in his 30s, he had recurrent attacks of “feverish catarrhs” (bronchitis), “rheumatism” of his hands and back, tormenting headaches, and incapacitating inflammation of his eyes. During his final year, he developed massive ascites accompanied by bloody vomitus indicative of cirrhosis of the liver. Post-mortem examination revealed vestigial auditory nerves, atrophy of the brain, an abnormally thick and dense skull, a fibrotic liver riddled with nodules the size of beans, an enlarged, hard pancreas, and abnormal kidneys. A recent analysis of a lock of hair purported to be Beethoven’s detected high levels of lead but no mercury.

If, as some have suggested, all of these abnormalities were the work of several different disorders gathered together in one poor soul, irritable bowel syndrome, alcoholic cirrhosis, and chronic lead intoxication would be three of the most likely culprits. Beethoven’s recurrent episodes of abdominal pain and diarrhea are certainly consistent with a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. However, this is a diagnosis in name only since its cause is unknown and it has no effective treatment. Alcoholic cirrhosis is a reasonable explanation for Beethoven’s fibrotic liver, although cirrhosis due to alcohol does not typically exhibit nodules of the size described in Beethoven’s post-mortem report, nor would it explain the destruction of Beethoven’s auditory nerves. Chronic lead intoxication does damage nerves, and given the high levels of lead detected in the sample of Beethoven’s hair as well as the possibility that the wine he consumed was adulterated with lead, chronic lead intoxication is a diagnosis that can’t be ignored. However, although lead is toxic to nerves and also causes abdominal distress, it characteristically impairs the function of motor nerves (producing palsies), not sensory nerves such as the auditory nerves. Moreover, the abdominal complaints most commonly associated with chronic lead intoxication are recurrent pain, which Beethoven had, and nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, and constipation (not diarrhea), which he did not have.

“Ludwig van Beethoven” by Joseph Karl Stieler. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Ludwig van Beethoven” by Joseph Karl Stieler. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.If Beethoven’s various disabilities were the result of a single disease rather than a multitude of diseases congregated in one unfortunate person, only syphilis could explain the character and course of his illness, in addition to virtually all of the post-mortem findings. Syphilis, the “great imitator,” has clinical manifestations so protean that Sir William Osler was moved to remark: “He who knows syphilis, knows medicine.” In its advanced stage, which may take decades to reach climax, syphilis can inflict heavy damage on all of the organs affected by Beethoven’s illness. The full spectrum of disabilities orchestrated by the infection has largely been forgotten thanks to the advent of penicillin, which is spectacularly effective in eradicating the infection. However, if one examines the extensive literature devoted to syphilis prior to the antibiotic era, the disorder emerges as a highly satisfactory explanation for virtually all of Beethoven’s ailments.

Beethoven’s deafness, for example, had a course along with associated abnormalities of the acoustic nerves found on post-mortem examination that are unlike any disorder encountered today. In over three decades of practice as an infectious diseases consultant, I have encountered no such patient, nor have several prominent neurologists and ear specialists, with whom I’ve discussed Beethoven’s case. Those who practiced medicine in the pre-antibiotic era saw many such cases of slowly progressive, bilateral destruction of the acoustic nerves. More often than not, the cause was syphilis.

Beethoven’s episodes of eye inflammation, which today we would call “interstitial keratitis,” his thick cranium, non-deforming rheumatism, macro-nodular cirrhosis, irritable bowel, tormenting headaches (“migraines”), and abnormal pancreas were likewise manifestations of advanced syphilis encountered during the pre-antibiotic era.

Unlike more exotic disorders offered over the years as Beethoven’s diagnosis, syphilis is a disease some would consider too banal and unbecoming to have extinguished the life of such a remarkable patient. The very thought that syphilis might have been the disease that silenced the source of some of the most sublime sounds ever conceived offends our sense of cosmic harmony. Nevertheless, whereas Beethoven was an artist, he was also a man. It made no difference to the disease that his nine symphonies, five piano concertos, violin concerto, seventeen string quartets, opera, and thirty-two piano sonatas were some of the most brilliant ever composed. Nor did it pause to consider whether the deafness it induced might impair the composer’s creativity, or to the contrary, enhance it by allowing Beethoven to perceive the new brand of polyphonic music that was to be his greatest gift to mankind.

Image Credit: “Piano Keys.” Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Beethoven’s diagnosis appeared first on OUPblog.

Purple Day: a day for thinking about people with epilepsy

Purple Day started with the curiosity and of a girl in eastern Canada, in the province of Nova Scotia, who had epilepsy. It soon became a world-wide success. Purple Day is now an international initiative and effort dedicated to increasing awareness about epilepsy around the globe.

Why is it so important to create awareness around people with epilepsy? Up to 10% of the general population suffers from a single seizure at some point in their lives, and up to 1% tend to have repeated unprovoked seizures, which per definition, is called epilepsy. So we are looking at a frequent medical condition in the range of insulin-dependent diabetes. On an individual level, a seizure event, particularly one that is accompanied with a loss or impairment of consciousness, almost always results in a deep disturbance of inner balance, autonomy, and self-confidence. The fact that these seizures can occur any time and anywhere is extremely frightening for the affected human being. The “unexpected part” is the scary part, as most of the people with epilepsy feel otherwise entirely healthy and often live a totally normal life. Family, close friends, and members of the social and professional environment often feel shocked and helpless in the first confrontation of such an event. It is not too surprising that this disorder — mentioned already in the first readings of humankind almost 4,000 years ago — created for centuries and millennia a huge confusion and misconceptions in society with regard to underlying causes and ways of potential treatments. People with epilepsy subsequently have often become victims of stigmatization and prejudices, leading to social isolation and higher rates of unemployment and comorbidities, even up to the modern times of the 21st century.

An epileptic or sick person having a fit on a stretcher, two men try to restrain him. Ink drawing attributed J. Jouvenet. CC BY 4.0 via Wellcome Library, London.

An epileptic or sick person having a fit on a stretcher, two men try to restrain him. Ink drawing attributed J. Jouvenet. CC BY 4.0 via Wellcome Library, London.Here’s the good news. Over the last 150 years, our understanding of the underlying causes of seizures and epilepsy — the scientific basis — has grown enormously. Epilepsy could be identified by means of functional tests such as EEG and structural tests such as MRI as highly diverse brain diseases in which a critical interplay of acquired and genetic factors create an individual brain environment with increased “hyperexcitability,” resulting in all kinds of clinical types of seizures.

The other really good news is that individually tailored treatment strategies, including medication, nerve stimulation, or resections of epileptogenic brain tissue, can lead to long-lasting seizure freedom in up to 80% of all affected people.

Knowledge transfer and making the patient the expert of his or her medical condition is a key component in a successful treatment approach in epilepsy. This is as important as all the new scientific fascinating insights in diagnosis and therapy. Getting patients involved, helping them to understand the disease, providing them with all available information, addressing all thinkable questions, and encouraging disease leadership and responsibility will create a powerful, trustful, and respectful relationship between patient, physicians and care givers. This team approach will lead to awareness and carefulness from all sides regarding disease management and immediate action taking. Compliance – defined as a reliable interaction between physician in patients with regards of agreed medical advice, prescriptions, and treatment goals – will significantly increase and impact a favorable prognosis for both the medical and social condition.

Purple day is a wonderful, annual opportunity to challenge all of us and help us to think how we can improve the lives of people with seizures in concert of all new exciting tools and insights. It is growing time and awareness time for everybody.

Heading image: EEG recording cap By Chris Hope. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Purple Day: a day for thinking about people with epilepsy appeared first on OUPblog.

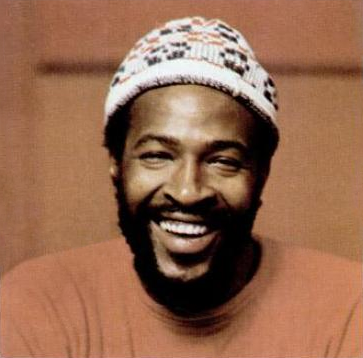

Gaye vs. Thicke: How blurred are the lines of copyright infringement?

In 2013, R&B singer Robin Thicke became a household name. “Blurred Lines” was Thicke’s fortuitous soul-disco-funk-influenced “pop” collaboration with producer Pharrell Williams and rapper Clifford Harris, Jr. (aka “T.I.”). It became the top-selling single of the year globally (selling over 14.8 million units), spent the longest time at the top of the Billboard’s Hot 100, set the all-time record for reaching the largest US radio audience, and also reached no. 1 in 80 countries.

Since then, however, “Blurred Lines” and Thicke’s overwhelming success have been eclipsed by the recent federal court case, in which a jury decided that its creators infringed upon the copyright of Marvin Gaye’s 1977 Billboard Hot 100 chart topper, “Got to Give It Up.” In an unprecedented verdict and after two years of litigation in various courts, the Gaye estate was awarded $7.4 million in recuperative damages.

While many debates have been sparked about the precedence this case and its verdict set for copyright law and artistic freedom, one of the more striking observations worth consideration is how the legal proceedings of the trial reflect the complex evolution of and relationship between sound, intellectual property, and (recorded) music from the advent of copyright law in the United States until the present. This grounding of copyright law in the context of US history might also help to unpack both the legal and cultural contentions that arise from the case. It might also point towards ways in which law and creativity—particularly within the popular music industry—might productively interconnect. Such a consideration might help to ground how we understand the idea of positing sound as intellectual property.

From Copyright to Intellectual Property in the United States

Trade ad for Marvin Gaye’s album Anthology. Billboard, page 1, 27 April 1974. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Trade ad for Marvin Gaye’s album Anthology. Billboard, page 1, 27 April 1974. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The nation’s first copyright law was passed in 1710, and was the first time an author could claim the right to their own written work beyond the printing guilds that published them. It was not until 1831 that music legally became the first “creative” work under protection. Still, the protection was based on the written document, the musical score in this case, and it was the publishers who gained copyright protection for their scores, not the author of the tune or music.

It was not until the International Copyright Act of 1891 that authors of musical works retained exclusive rights to their copyrighted scores, and publishers were required to obtain permission from them for printing. To whom the law granted property ownership, however, was restricted. Throughout most of the 19th century, as African Americans were structurally denied access to many civic, economic, and political rights, Irish-, Jewish-, and Anglo-American publishers and performers gained unprecedented success in the establishment of the nascent popular music industry through blackface minstrelsy—the first original and popular form of mass entertainment in North America. The founders of the US popular music industry—and those who would begin to claim copyrights through its sheet music—were mostly (white) men who, in blackface, “appropriated” real and imagined performances of black culture and blended them with others (classical, Irish folk music, etc.) during enslavement, emancipation, and Jim Crow, into a complexly amalgamated popular style.

To protect their “intellectual property,” composers in the 1890s began to lobby for greater legal protection of written and scored works, as the cultural autonomy of the “author” continued to develop in the late 19th century. After the intense lobbying efforts of Tin Pan Alley-based composers, due to then recent developments in recording and reproduction technologies, the passage of the Copyright Act of 1909 allowed them to claim authorship of their scores for mechanical reproduction, and record companies were required to either ask permission for the initial recording, or a flat fee for subsequent ones. These protections, however, were still based on the written score—leaving the sounds that went into their live realizations up for legal grabs.

The latest revision of copyright law did not occur until 1976, after music (and film) piracy became widespread with the mass introduction of tape and cassettes in the 1960s, threatening the pockets of the entertainment industry. Fortunately, the new Act included revisions that also extended the terms of ownership for authors, and extended the general rights of ownership for publishers and authors alike. This Act also confirmed that the “original” sound of sound recordings—as produced by those involved in the recording’s creation—became copyrightable material. After almost two centuries of copyright law and practice, ideas and laws of intellectual property began to extended beyond the “text,” or written score and lyrics, to include its performance and realization.

The Case of “Blurred Lines”

Coincidentally, it was a legal loophole from the 1976 Act, the cultural expansion of what constitutes “intellectual property,” and the limitations of our current copyright system that set the stage for how the “Blurred Lines” case was argued and adjudicated in the US District Court of California.

After the Marvin Gaye estate formally requested some sort of recompense from Thicke, Williams, Harris, and the distributors of “Blurred Lines” for its sonic similarity and “feel” to Gaye’s “Got to Give It Up” in 2013, the trio launched a “Complaint for Declamatory Relief” against the Gaye estate. In this case, the creators of “Blurred Lines” claimed, “Defendants continue to insist that plaintiff’s massively successful composition, ‘Blurred Lines’…and ‘Got to Give It Up’ ‘feel’ or ‘sound’ the same. Being reminiscent of a ‘sound’ is not copyright infringement. The intent in producing ‘Blurred Lines’ was to evoke an era. In reality, the Gaye defendants are claiming ownership of an entire genre, as opposed to a specific work.” After sufficient evidence was produced to suggest a discrepancy between the plaintiff and defendant’s claims, however, the summary judgment was denied, and the historical court case was initiated.

There are two basic matters that must be proved to establish copyright infringement under our current law.

Ownership of a valid copyright, and

copying of “original” constituent elements of the copyrighted work.

As the case’s court instructions indicate, to prove infringement under copyright law, one has to prove the copying of an expression of an idea, and not just an idea itself.

The legal loophole found in copyright law by the Thicke/Williams camp was that Gaye’s commercial sound recording of “Got to Give It Up”—which contains many of the sonic and performative elements that suggest the “groove” and “feel” of the song, including Gaye’s voice—was not admissible court evidence. The lead sheet (a truncated score that contains limited musical indications) and commercial recording to Marvin Gaye’s “Got to Give It Up” were deposited for copyright before the new 1976 Copyright Act went into effect in 1978. This loophole suggested that Gaye only owned the copyright to the lead sheet and did not legally own any rights to the recording of “Got to Give It Up,” and it therefore could not be used in court. This required both camps to provide sufficient competing evidence, through a cyber forensic analysis of digital sound and the analysis of expert music scholars, to show whether the relationship between the songs was one of inspiration or exploitation.

While many (including Thicke in his early discussions of his song) have admitted to the relationship between the “feel” or “groove” of the two pieces, the language and tools for proving such claims are limited under copyright law. Because the law is still primarily steeped in assigning copyright to “original” written works, lyrics, or recordings generally owned by record companies, a legal discussion of “groove” or “feel” leads to what musicologists call “structural listening/analysis”—where musical elements are singled out by the chosen examiner to show how what we hear might be quantified. In doing so, the experts in this case were charged with providing evidence to convince the jury of the following questions on their verdict form:

Do you find by a preponderance of evidence that the Thicke parties infringed the Gay Parties’ copyright in the musical composition “Got to Give It Up” and “Blurred Lines”?

Do you find by a preponderance of the evidence that the Thicke parties’ infringement of the copyright in “Got to Give It Up” was willful?

Do you find by a preponderance of the evidence that the Thicke parties’ infringement of the copyright in “Got to Give It Up” was innocent?

With only the limited lead sheet that Gaye deposited for copyright, an edited recording of the copyrighted elements (sans Gaye’s voice) of “Got to Give It Up,” statements made by the creators, and the music analysis, the Gaye party and its expert witnesses relied on an expanded understanding of sound as intellectual property in order to make the musical case that “Blurred Lines” went beyond mere homage to illegal imitation. In accordance with copyright law, the “similarities” under consideration had to be proven independently of one another in order to show infringement.

However, it was not the actual discussion of “groove” or “feel,” or a legal consideration of these concepts as copyrightable elements (e.g., sources of intellectual property) beyond what the court deems as “scènes à faire” (or “generic ideas”). It was the way in which groove was broken down into a traditional structural analysis, something that could be proven as a copyrightable text, something “scientifically quantifiable,” that effectively convinced the jurors that there was “direct and circumstantial evidence” that “Blurred Lines” was in some part derived from Gaye’s work.

The Future of Copyright Law

Single cover for Blurred Lines by Robin Thicke featuring T.I. and Pharrell. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Single cover for Blurred Lines by Robin Thicke featuring T.I. and Pharrell. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The verdict is a huge win for the Gaye estate. Symbolically, it is also a win for the many artists, especially African American artists in the United States, who have historically suffered unfair use of and unequal compensation for works, or who have been denied access to copyright their original creations. The verdict is also a victory for those whose creative intellectual property—particularly of the sonic and corporeal variety—has only recently been valued and upheld by law.

On the other hand, because of the traditional and structural approach to presenting the case, the verdict could also lead to some artists feeling limited by their creative license to explore sounds and styles of previous eras, or it might encourage shrill industry executives to create practices that exploit both the freedoms and limitations of copyrighted and potentially copyrightable material.

Albeit a difficult task, this significant case begs for new considerations of what constitutes intellectual property in music, for interrogating the full-range of music’s constituent components beyond structural listening, and for how we understand the copyright potential of music beyond its textual and recorded basis. If artists, musicologists, litigators, and lawmakers begin to reorient themselves around the history and recent developments in copyright, as well as ideas of what might constitute intellectual property in music (i.e., sound and groove), we might find ourselves lobbying for changes to the 1976 Copyright Act that reflect 21st century needs, rather than trying to find ways around outdated laws and procedures in contentious litigations on sound.

Feature Image: CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Gaye vs. Thicke: How blurred are the lines of copyright infringement? appeared first on OUPblog.

Lament of an educator/parent

My seventeen-year-old son has just completed fifteen examinations in the course of two weeks. They varied in length – some in excess of three hours, with a half hour break before the next exam – and we are still feeling the fallout from this veritable onslaught. These were not ‘the real exams’ – the ones that ‘counted’ – the ones that will help to discriminate between the sheep and the goats, who gets into university (and which ones of course), and who will be left outside the doors. Theoretically, then, the pressure on him should not have been so very great, at least not as pronounced as it will be a few months from now.

Not only as a mother, but as an educator, I cannot help but wonder about this process. Looking at my son, increasingly silent and exhausted, it is hard not to feel that formal education – at least at this particular juncture in his life – is anything but a stimulus to thinking in a deep and creative way about the world around him. As a young child he was nick-named ‘What if’, always posing questions about how the world might be transformed. It will be a miracle if that sense of curiosity and wonder is not beaten out of him by the time he graduates.

Writing nearly 40 years ago, philosopher Mary Warnock summarized the challenge of teaching in the following way:

The belief that there is more in our experience of the world than can possibly meet the unreflecting eye, that our experience is significant for us, and worth the attempt to understand it… this kind of belief may be referred to as the feeling of infinity. It is a sense… that there is always more to experience, and more in what we experience than we can predict. Without some such sense, even at the quite human level of there being something which deeply absorbs our interest, human life becomes perhaps not actually futile or pointless, but experienced as if it were. It becomes, that is to say, boring (1976: 202).

Igniting imagination is, or should be, the purpose of education, as this provides the impetus to explore what lies beyond known experience. The issues which Warnock eloquently identifies here are indeed some of the major challenges which confront those of us who teach. How do we effectively communicate to our students that what they experience in their own worlds is important and even significant, but that the world extends far beyond this? It is challenge enough oftentimes to demonstrate to our students that what we wish to teach them has relevance to their own lives. But we must be able to take them further than that, to show them ‘that there is always more to experience, and more in what we experience than we can predict’. If we can even begin to demonstrate to students that there are important connections between their individual lives and the world of ideas – in other words to make them thirsty for a sense of what lies beyond – then we have done much.

Warnock refers to the aim of ‘imaginative understanding’ (1989:37). This requires us both to make connections between things, to synthesize, as well as to throw that which seems of a whole into chaotic disarray. Warnock identifies different levels at which the imagination is employed:

If…our imagination is at work tidying up the chaos of sense experience, at a different level it may, as it were, untidy it again. It may suggest that there are vast unexplored areas, huge spaces of which we may get only an occasional awe-inspiring glimpse, questions raised by experience about whose answers we can only with hesitation speculate (1976: 207).

It is our imagination which pushes us to see beyond that which already is apparent, either experientially or perceptually. As Warnock indicates, it is this ‘looking beyond’ which has the potential to spark the curiosity of students, to lift them from ‘boredom.’ Paradoxically, through the exercise of our imagination, we can begin to perceive alliances and contradictions that were previously hidden from our view. In this sense, one can see the basis of an argument that a multi- and particularly interdisciplinary approach to teaching (and research) creates an atmosphere which is fertile for the imagination.

Pile of notebooks for Molly Andrew’s son. Courtesy of the author.

Pile of notebooks for Molly Andrew’s son. Courtesy of the author.Of course in order to nourish imagination in students, teachers must have the preparedness to see it. The poet John Moat argues that many teachers are themselves so beaten down by the system, that their own imaginations are being starved of air. When this is so,

…it is unreal to suppose they could find time or energy to foster their own self-expressive imaginative lives. The consequence is predictable enough – teachers come to the view the Imagination not as a reality in their own lives, but as some technical application that can be ear-marked and graded by the system. As a result they are often taken out of their depth by the raw, unruly Imagination of their students, are perhaps intimated, and haven’t the experience to either encourage or discipline it (2012: 212).

We cannot blame the teachers. Not only are they themselves deprived of oxygen for their own creativity, but they operate within a system in which intellectual engagement is measured almost wholly in terms of a student’s ability to reproduce standardized formulas in all areas, creating a certain bland sameness which mitigates against creativity. Samuel Coleridge argued that it is the imagination which brings into balance opposite or discordant qualities (Murphy 2010: 103). Building on this precept, Peter Murphy elaborates:

…creative acts are formed of elements which are borrowed from widely separated domains. That is why disciplinary drudges, even highly published ones, who plough the same field continuously, produce little or nothing of interest. The imagination borrows things from the most unlikely sources and compounds them (Murphy 2010: 103).

But even while imagination inclines us towards synthesis, the same ability to re-conceptualise what holds things together can also serve to break down that which had seemed whole. Imaginative understanding can lead us to question the very foundations on which we have built order in our lives. Thus it is that we use our imagination to detach ourselves from that which is familiar, giving us a new perception of not only that which is there, but also that which is absent. Warnock, elaborating on the views of Sartre, writes about the crucial relationship between presence and absence in the creative functioning of the imagination:

…there is a power in the human mind which is at work in our everyday perception of the world, and is also at work in our thought about what is absent; which enables us to see the world, whether present or absent as significant, and also to present this vision to others, for them to share or reject. And this power, though it gives us ‘thought- imbued’ perception …is not only intellectual. Its impetus comes from the emotion as much as from the reason, from the heart as much as from the head (Warnock 1976: 196).

So what can we do to stimulate this ‘thought-imbued perception’? How can we encourage the next generation to think meaningfully about their experiences, to gain a deeper understanding not only of their individual lives but of their wider social contexts, and further, to move beyond that known world? What can we do as teachers and as parents to help them to experience ‘the feeling of infinity’, the imaginative emotion John Stuart Mill once described as the feeling we get when ‘an idea when vividly conceived excites in us’ (cited in Warnock 1976: 206).

Somehow these days I cannot escape the feeling that the only ‘feeling of infinity’ that my son is experiencing is that of endless examination.

The post Lament of an educator/parent appeared first on OUPblog.

Dogs in digital cinema

Performances by dogs are a persistent feature of contemporary cinema. In recent years, audiences have been offered a wide range of canine performances by a variety of breeds, including Mason the collie in the remake of Lassie, Jonah the labrador retriever in Marley & Me, the akita in Hachi: A Dog’s Story, the dogo argentino in Bombón: El Perro, Uggie the Jack Russell terrier in The Artist, and numerous others.

However, a number of recent films aimed at children present performances by dogs in which a new phenomenon is visible. Films such as Cats & Dogs (and its sequel), Underdog, Beverly Hills Chihuahua, and Marmaduke combine the traditional canine actor with digital effects. Unlike films in which animal characters are wholly constituted through computer-generated imagery, the animals which feature in this group of films are composite beings, in which the bodies of the animal actors used during the shoot work in tandem with the virtuosity of visual effects personnel in post-production.

Supplementing real dogs with digital animation produces performances that have benefits on many different levels. Firstly, they are much more effective dramatically because they can become more anthropomorphically expressive to suit the needs of the story. Economically they are less time-consuming and therefore less expensive because the performance is no longer determined by the unpredictable or intractable volition of real animals, however ‘well-trained’. The problems that arise even when working with ‘professional’ dog actors can be exasperating, as Lance Bangs’ short film The Absurd Difficulty of Filming a Dog Running and Barking at the Same Time (shot on the set of Spike Jonze’s Where The Wild Things Are) makes abundantly clear. The technological mediation of dog actors’ performances by digital effects allows contemporary filmmakers to overcome such problems and present, should they so wish, dogs flying and talking at the same time.

Marmaduke on set, by Patty Mooney. CC-BY-SA-NC-2.0 via Flickr.

Marmaduke on set, by Patty Mooney. CC-BY-SA-NC-2.0 via Flickr.While the Palm Dog, a fixture at the Cannes Film Festival since 2001, has been awarded to both live (such as Lucy, from Wendy and Lucy) and animated dogs (such as Dug, from Up) – it is now the case that much popular children’s media features performances by dogs in which the distinction between real and animated animals is blurred. Two Great Danes, Spirit and George, are credited for the lead role in Marmaduke (with Owen Wilson providing the voice), but the characterization owes as much to the expertise of various modellers, riggers, texturers and compositors as it does to either of the dogs. A ‘digital muzzle replacement’ enables Marmaduke to appear to address the spectator directly, while the digital manipulation of the dog’s eyebrows and ears allows for a range of facial expressions that coincide with the inflections of Wilson’s vocal performance (the flatulence was presumably also added in post-production). While computer-generated visual effects are used throughout the film to ‘animate’ the various dog actors’ faces in ways that support the human actors’ vocal performances, they are also deployed in certain comic sequences. For example, when Marmaduke breakdances or goes surfing, the body of the dog is completely replaced with digital animation for the purpose of presenting ‘moves’ that a real dog would be incapable of executing (such as head-spins and somersaults). Nowadays, digital effects routinely provide the comic spectacle of such ‘realistic’ dogs moving and talking like cartoon canine characters through the photographically real spaces presented by the live-action film.

“The algorithmic programming which enables such composite canine performances is, in important respects, analogous to the manipulation of dogs’ genetic code in selective breeding”

The algorithmic programming which enables such composite canine performances is, in important respects, analogous to the manipulation of dogs’ genetic code in selective breeding. Yi-Fu Tuan has described domestication as involving the manipulation of a species’ genetic constitution through breeding practices. For dogs, this involved their transformation into aesthetic objects. Harriet Ritvo has argued that when breeders ‘redesigned’ the shape of dogs in accordance with ‘swiftly changing fashions’ the dog’s body ‘proclaimed its profound subservience to human will,’ becoming ‘the most physically malleable of animals, the one whose shape and size changed most readily in response to the whims of breeders’.

The manipulability of dogs, in other words, anticipates the inherently malleable digital image. The various exaggerated morphological features that characterize the conformation of the pedigree dog – such as the large head, the flat face, the long ears or the short legs – were produced by a systematic stretching and shrinking of the species according to specific aesthetic criteria, with serious implications for the physical and psychological well-being of the individual dogs.

Composite animal performances like those featured in Marmaduke or the Beverly Hills Chihuahua films can thus reveal for us the repressed histories of such subjection. These hybrid performances, which present personified and plasmatic domestic pets for our entertainment, remind us that dogs have long endured such subjugation. Indeed they remain subordinate to, and constituted by, an aesthetic and technological regime in which they are exploited as if they were already CGI images, and ‘redesigned’ according to the logic of what Philip Rosen has called the ‘practically infinite manipulability’ of digital cinema.

Featured image credit: Robert Bray and Lassie, 1967. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Dogs in digital cinema appeared first on OUPblog.

March 23, 2015

A new philosophy of science

One of the central concepts in chemistry consists in the electronic configuration of atoms. This is equally true of chemical education as it is in professional chemistry and research. If one knows how the electrons in an atom are arranged, especially in the outermost shells, one immediately understands many properties of an atom, such as how it bonds and it’s position in the periodic table. I have spent the past couple of years looking closely at the historical development of this concept as it unfolded at the start of the 20th century.

What I have found has led me to propose a new view for how science develops, a philosophy of science if you will, in the grand tradition of attempting to explain what science really is. I am well aware that such projects have fallen out of fashion since the ingenious, but ultimately flawed, attempts by the likes of Popper, Kuhn, and Lakatos in the 1960s and 70s. But I cannot resist this temptation since I think I may have found something that is paradoxically obvious and original at the same time.

The more one looks at how electronic configurations developed the more one is struck by the gradual, piecemeal and at times almost random development of ideas by various individuals, many of whose names are completely unknown today even among experts. Such a gradualist view flies in the face of the Kuhnian notion whereby science develops in a revolutionary fashion. It goes against the view, fostered in most accounts, of a few heroic characters who should be given most of the credit, like Lewis, Bohr, or Pauli.

If one looks at the work of the mathematical physicist John Nicholson, one finds the idea of the quantization of electron angular momentum that Bohr seized upon and made his own in his 1913 model of the atom and his own electronic configurations of atoms. In looking at the work of the English chemist Charles Bury, one finds the first realization that electron shells do not always fill sequentially. Starting with potassium and calcium, a new shell is initiated before a previous one is completely filled, an idea that is especially crucial for understanding the chemistry of the subsequent transition elements, starting with the element scandium.

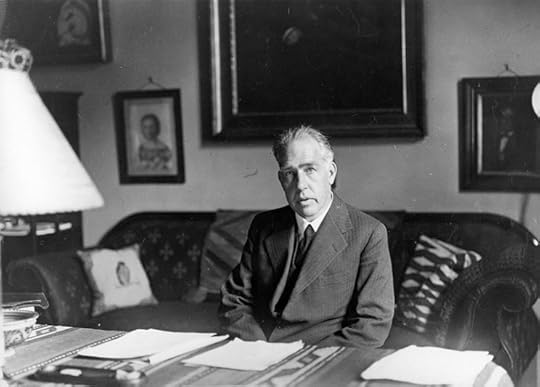

Niels Bohr. Image Credit: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Niels Bohr. Image Credit: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. This was followed by the work of the then Cambridge University graduate student, Edmund Stoner, who was the first to use the third quantum number to explain that electron shells were not as evenly populated as Bohr had first believed. Instead of a second shell consisting of two groups of four electrons that Bohr favored, Stoner proposed two groups of two and six electrons respectively. The Birmingham University chemist John Main Smith independently published this conclusion at about the same time. But who has ever heard of Main Smith? The steps taken by these almost completely unknown scientists catalyzed the work of Wolfgang Pauli when he proposed a fourth quantum number and his famous Exclusion Principle.

What I am groping towards, more broadly, is a view of an organic development of science as a body-scientific that is oblivious of who did what when. Everybody contributes to the gradual evolution of science in this view. Nobody can even be said to be right or wrong. I take the evolutionary metaphor quite literally. Just as organic evolution has no purpose, so I believe it is true of science. Just as the evolution of any particular biological variation cannot be said to be right or wrong, so I believe is true of scientific ideas, such as whether electron shells are evenly populated or not. If the idea is suited to the extant scientific milieu it survives and leads others to capitalize on any aspect of the idea that might turn out to be useful.

Contrary to our most cherished views that science is the product of brilliant intellects and that logic and rationality are everything, I propose a more prosaic view of a great deal of stumbling around in the dark and sheer trial and error. Of course such a view will not be popular with analytical philosophers, in particular, who still cling to the idea that the analysis of logic and language holds the key to understanding the nature of science. I see it more like a craft-like activity inching forward one small step at a time. Language and logic do play a huge role in science but in what I take to be a literally superficial sense. The real urge to innovate scientifically comes from deeper parts of the psyche, while logic and rational thought only appear at a later stage to tidy things up.

In recent years many scholars who write about science have accepted limitations of language and rationality, but the same authors have generally tended to concentrate instead on the social context of discoveries. This has produced the notorious Science Wars that so polarized the intellectual world at the close of the 20th century. What I am trying to do is to remain focused on the grubby scientific details of concepts like electron arrangements in atoms, while still taking an evolutionary view which tracks what actually takes place in the history of science.

Feature Image: Test tubes by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post A new philosophy of science appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers