Oxford University Press's Blog, page 680

April 6, 2015

Who are the forgotten Shakespearean actors?

Many of you will have heard of Lord Laurence Olivier and Sir Kenneth Branagh and will be able to recognise the names of other famous Shakespearean actors. But how much do you know about Edmund Kean, Charlotte Cushman, or Tommaso Salvini? Below, Stanley Wells reveals some of the lesser remembered actors of the past that he would have loved to have seen perform live on stage.

Edmund Kean (1787?-1833)

I’d love to have seen Kean. Coleridge said ‘to see him act, is like reading Shakespeare by flashes of lightning’. It’s not entirely a compliment but it does pinpoint something in Edward Kean; that he tended to flash, to have moments, and to perhaps not sustain the role with the sort of continuity and growth of character that some other actors did. But he was a wonderful character, a rip-roaring, fantastical, high-living man who wore himself out, sadly. Towards the end of his career, dissipation and drink had taken their toll and he died relatively young. His last performance was Othello, he collapsed into the arms of his son, Charles Kean who was playing Iago, and said ‘speak to them for me Charles’, and went off. But he must have been a terrifically exciting actor to see.

Charlotte Cushman (1816-76)

Another I would have very much liked to have seen is the American Charlotte Cushman. She was a remarkable lady in her own right, not a beauty. She referred to her face as ‘my unfortunate mug’, for example. But she had great power as an actress, and specialised in male roles. She played Hamlet, of course, and she played Cardinal Wolsey. But her greatest role was oddly enough Romeo, which she played rather bizarrely to her sister Susan Cushman’s Juliet.

When Charlotte Cushman was playing Romeo, she was seen by a distinguished playwright called James Sheridan Knowles, and he compared the impact of her acting in Romeo’s scene with the Friar favourably with Kean’s in the third act of Othello, which was one of his greatest triumphs. He said:

Tommaso Salvini as Otello. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Tommaso Salvini as Otello. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.‘I was not prepared for such a triumph of pure genius … It was a scene of topmost passion; not simulated passion,–no such thing; real, palpably real. The genuine heart-storm was on, – on in the wildest fitfulness of fury; and I listened and gazed and held my breath, while my blood ran hot and cold.’ [Wells, Great Shakespeare Actors]

And another fellow actor was impressed by her overt sexuality as Romeo, saying ‘her amorous endearments were of so erotic a character that no man would have dared to indulge in them coram public [in a public place]’. She was a great character and a great actress. She was American but played quite a lot in England, as did quite a lot of the other American actors like Edwin Booth for example who acted with Henry Irving in his very famous Hamlet.

Tommaso Salvini (1829-1915)

Another actor that I got very interested in was an Italian called Tommaso Salvini. He is particularly odd in some ways because he always played in Italian, even though he was playing with English-speaking actors in both England and America. It’s a very artificial thing to do, and makes demands on the other actors; coming in with your cues is quite difficult if you don’t understand Italian. And it’s quite demanding on the audiences, too. But they lapped it up. It still happens occasionally in our days but usually in the operatic field where sometimes an opera singer will sing in one language while the rest of the cast sing in another.

So Tommaso Salvini, the great Italian actor, had enormous success, especially as Othello. He was a very powerful looking man, the photographs I’ve been able to find of him are quite forbidding. He looks a bit like Lord Kitchener calling the troops, with a long moustache in the Victorian style.

He was clearly a formidable actor, especially as Othello. He was very physical, and there’s a rather shocking description of how he played the murder of Desdemona. A critic saying that:

‘he seizes her [Desdemona] by the hair of her head, and, dragging her on to the bed, strangles her with a ferocity that seems to take delight in its office… Nearing the end he rises, and at the supreme moment cuts his throat with a short scimitar, hacking and hewing with savage energy, and imitating the noise that escaping blood and air may together make when the windpipe is severed’. [Wells, Great Shakespeare Actors]

You can understand that when he was playing that scene he was very violent with his Desdemona which meant that several actresses declined the honour of playing Desdemona with him. They were scared stiff, I expect. But nevertheless, he was clearly a very great actor, and I’d have loved to have seen him.

The post Who are the forgotten Shakespearean actors? appeared first on OUPblog.

April 5, 2015

Vote Jeremy Clarkson on 7 May! Celebrity politics and political reality

The news this week that Jeremy Clarkson’s contract with the BBC will not be renewed might be bad news for Top Gear fans but could it be good news for politics? Probably not…

I wonder what Jeremy Clarkson is up to as you read this blog. Could he be casting his eye over the jobs pages in the newspapers, possibly signing-up to some on-line employment agencies, or simply staring at his mobile phone in the hope that it will ring with the message that says ‘The BBC has changed its mind! All is forgiven’? The answer is ‘probably not’ but lets run with the idea for a moment and think of what a slightly grumpy Jeremy with time on his hands might do for his next big project.

I must at this point admit that the testosterone soaked, ‘man-fun’ focus of Top Gear has never quite rung my bell, but as a political scientist (yawn, yawn, yawn) I can’t help but think that there is something going on. Top Gear seems to be spreading as some form of international cultural craze. Indeed, its global reach appears unstoppable and so far includes over sixty countries from Argentina to Australia and Israel to Ireland. At the same time a quite different cultural craze that was popular in recent decades (i.e. democracy) appears to be in something of a retreat. This is reflected in a massive body of evidence and data that reveals increasing levels of public disenchantment with traditional politics.

Take the United Kingdom as an example. With just weeks before the 2015 General Election the latest ‘Audit of Political Engagement’ from the Hansard Society suggests that just 49% of the public says they are certain to vote. In relation to 18-24-year-olds the picture of democratic desire is more bleak with just 16% saying they are certain to vote, but nearly twice as many saying that they definitely will not be voting. Those who claim to be a strong supporter of a political party is down to just 30% and the general picture is one of decline.

Jeremy Clarkson and James May Top Gear presenters with my Lancia Beta Coupe Stanford Hall 2008 by Tony Harrison. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Jeremy Clarkson and James May Top Gear presenters with my Lancia Beta Coupe Stanford Hall 2008 by Tony Harrison. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.The number who believe themselves to be registered to vote? Decline. Those that feel they have some influence over local issues? Decline. Satisfaction with the overall system? Decline. Petition to reinstate Jeremy Clarkson? Surpasses one million voters.

Hold on a minute! Have I spotted something? Politics and politicians appear to be in big trouble; Clarkson appears to be surfing a wave of popular support that most politicians could never dream of. Add the fact that Jezza has a bit of unexpected free time on his hands and ‘hey presto’ — Jeremy Clarkson MP.

Such simple and outlandish (or should that be ‘out-laddish?) calculations would be funny if it were not for the fact that Jeremy Clarkson has already threatened to stand for election to Parliament. In September 2013 he used the Internet to tell his followers ‘I’m thinking I might stand in the next election as an independent for Doncaster North, which is where I’m from. Thoughts?’ he wrote.

A cruel twist of fate and a lack of hot food in a Northern hotel now makes this question all the more interesting.

What are my thoughts?

This is, of course, all hypothetical but there is a devil in me that would quite like to see Clarkson stand and there is little doubt that he could give Ed Miliband a run for his money in a town where my family is also from. But would this really be good for democracy? Would it make Jeremy or break Jeremy? The answer is that we will never know but there is a broader question about celebrity politics and the power of populism.

With comedians like Al Murray, Russell Brand, and others increasingly entering the political arena and posing as joke candidates, making ‘mockumentaries’, or attempting to make some sort of political intervention our political reality seems to be becoming somewhat warped or distorted: politics as a farcical parody of itself. Let’s remember that the celebrities are themselves, whether they admit it or not, a form of social elite. Swapping one elite for another does not sound like a way to cure the political disengagement that appears so pronounced. So Jeremy, just jump in your car and keep on driving…

The post Vote Jeremy Clarkson on 7 May! Celebrity politics and political reality appeared first on OUPblog.

Is caffeine a gateway drug to cocaine?

Caffeine is the world’s most commonly abused brain stimulant. Daily caffeine consumption by adolescents (ages 9-17 years) has been rapidly increasing most often in the form of soda, energy drinks, and coffee. A few years ago, a pair of studies documented that caffeine consumption in young adults directly correlated with increased illicit drug use and generally riskier behaviors. However, these correlational studies never examined the long-term consequences of caffeine consumption, i.e. does long-term coffee consumption during adolescence lead to riskier behaviors during adulthood?

How might caffeine consumption produce such long-lasting changes? The answer lies in understanding the actions of caffeine in the brain. In adults, caffeine appears to indirectly enhance the activity of dopamine within the brain’s pleasure centers. Drinking coffee produces a mild euphoria due to this effect and encourages the brain to crave more coffee. Yes, coffee is addicting, but only mildly so as compared to many other drugs of abuse such as tobacco and cocaine.

The adolescent brain responds differently to caffeine as compared to the adult brain. Caffeine produces a more dramatic increase in motor activity in adolescents. In addition, long-term caffeine consumption produces more tolerance faster as compared to adults, suggesting that caffeine might produce greater changes in brain chemistry in the developing adolescent brain. This speculation was strengthened by the finding that long-term caffeine consumption during adolescence leads to greater sensitivity to amphetamine-like drugs that are used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorders. Fortunately, there is no current evidence that caffeine consumption leads to attention deficit hyperactivity disorders in children.

A recent study, published in January 2015 in the journal Neuropsychopharmacology by neuroscientists at the University of Colorado at Boulder, investigated whether long-term caffeine consumption during adolescence could enhance the sensitivity of the adult brain to cocaine. They reported that adolescent caffeine exposure heightens the sensitivity to cocaine-induced euphoria and related behaviors via its parallel actions on dopamine in the brain’s pleasure center. Adolescent consumption of caffeine actually altered the brain’s neurochemistry so that the adult brain’s response to cocaine was enhanced.

Interestingly, consuming caffeine as an adult for the same length of time didn’t produce the same type of behavioral or neurochemical alterations. This finding suggests that the developing adolescent brain is vulnerable to the effects of caffeine on dopamine signaling and that these changes can linger into adulthood and influence the abuse potential of euphoria-producing drugs such as cocaine. By any definition, caffeine is clearly a gateway drug. Is caffeine a drug or a food? Sometimes it is very hard to tell the difference.

Featured image credit: Coffee. Photo by Petr Kratochvil. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Is caffeine a gateway drug to cocaine? appeared first on OUPblog.

Mixed Yablo Paradoxes

The Yablo Paradox (Yablo, Stephen 1993) is an infinite sequence of sentences of the form:

S1: For all m > 1, Sm is false.

S2: For all m > 2, Sm is false.

S3: For all m > 3, Sm is false.

: : : :

Sn: For all m > n, Sm is false.

: : : :

Loosely put, each sentence in the Yablo sequence ‘says’ that all of the sentences ‘below’ it on the list are false. The Yablo sequence is paradoxical – there is no coherent assignment of truth and falsity to the sentences in the list – as is shown by the following informal argument:

Proof of paradoxicality: Assume that Sk true, for arbitrary k. Then, for every m > k, Sm is false. It follows that Sk+1 is false. In addition, it follows that, for every m > k + 1, Sm is false. But given what Sk+1 says (that every sentence ‘below’ it is false), it follows that Sk+1 is true. Contradiction. Thus, Sk cannot be true, and must be false. Since k was arbitrary, it follows that, for any n, Sn is false. So S1 is false. In addition, for all n > 1, Sn must be false. But given what S1 says (that every sentence ‘below’ it is false), it follows that S1 is true. Contradiction.

Not too long after the discovery of the Yablo Paradox, Roy Sorensen published a paper that included a variant of the Yablo Paradox called the Dual of the Yablo Paradox, which we obtain by replacing the universal quantifications (the “for all”s) with existential quantifiers (“there exists”s). Thus:

S1: There exists an m > 1 such that Sm is false.

S2: There exists an m > 2 such that Sm is false.

S3: There exists an m > 3 such that Sm is false.

: : : :

Sn: There exists an m > n such that Sm is false.

: : : :

Loosely put, each sentence in the Dual Yablo sequence ‘says’ that at least one of the sentences ‘below’ it on the list is false. The Dual of the Yablo Paradox is also, as its name suggests, paradoxical. The proof is left to the reader (hint: the reasoning is a sort of ‘mirror image’ of the reasoning for the Yablo paradox: begin with “Assume that Sk is false, for arbitrary k…)

Paradox Box by Playful Geometer. CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0 via Deviant Art.

Paradox Box by Playful Geometer. CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0 via Deviant Art. So there are (at least) two sorts of sentences that might occur in infinite Yabloesque sequences – sentences of the form:

Sn: There exists an m > n such that Sm is false.

which we shall call Y-exists sentences, and sentences of the form:

Sn: For all m > n, Sm is false.

which we shall call Y-all sentences (having grown up in the South of the United States, I quite enjoyed writing that!) One obvious question to ask is what happens when we consider infinite sequences of sentences where some of the sentences are Y-exists sentences, and some of the sentences are Y-all sentences – we can call such a sequence a mixed Yablo sequence. The answer is relatively straightforward:

Theorem 1: Any mixed Yablo sequence containing only finitely many Y-all sentences is paradoxical.

Proof: If there are only finitely many Y-all sentences in the list, then there is a k such that all sentences below Sk are Y-exists sentences. Assume, for any j > k, that Sj is false. It follows that Sj+1 is true. In addition, it follows that, for every m > j + 1, Sm is true. But given what Sj+1 says (that some sentence ‘below’ it is false), it follows that Sj+1 is false. Contradiction. Thus, Sj cannot be false, and must be true. Since j was any arbitrary number greater than k, it follows that, for any n > k, Sn is true. So Sk+1 is true. In addition, for all n > k+1, Sn must be true. But given what Sk+1 says (that some sentence ‘below’ it is false), it follows that Sk+1 is false. Contradiction.

Theorem 2: Any mixed Yablo sequence containing only finitely many Y-exists sentences is paradoxical.

Proof: A dual, ‘mirror-image’ of the reasoning in Theorem 1, left to the reader.

Theorem 3: Any mixed Yablo sequence containing infinitely many Y-all sentences and infinitely many Y-exist sentences is not paradoxical.

Proof: If there are infinitely many Y-all sentences in the list, and infinitely many Y-exists sentences in the list, then there is a Y-all sentence ‘below’ any Y-exists sentence, and a Y-exists sentence ‘below’ any Y-all sentence. Assign truth to each Y-exists sentence and falsity to each Y-all sentence. Then any Y-exists sentence will indeed be true, since there will be at least one false Y-all sentence ‘below’ it, and any Y-all sentence will be false since there will be at least one true Y-exists sentence ‘below’ it.

These technical results have the following, rather interesting upshot: When we move from consideration of the Yablo Paradox and its Dual in isolation to a consideration of mixed Yabloesque sequences more generally, it turns out that most of these sequences are not paradoxical. In technical jargon, both the collection of sequences that contain only finitely many Y-all sentences, and the collection of sequences that contain only finitely many Y-exists sentences, are countably infinite – they are infinitely many such sequences, but this collection of sequences is the smallest size of infinite collection. The collection of infinite Yabloesque sequences that contain both infinitely many Y-all sentence and infinitely many Y-exists sentences, however, is a much larger collection. It is what is called continuum-sized, and a collection of this size is not only infinite, but strictly larger than any countably infinite collection. Thus, although the simplest cases of Yabloesque sequence – the Yablo Paradox itself and its Dual – are paradoxical, the vast majority of mixed Yabloesque sequences are not!

Featured image credit: ‘Wormhole’, by Paco CT. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr

The post Mixed Yablo Paradoxes appeared first on OUPblog.

April 4, 2015

How has Venezuela’s foreign policy changed in the 21st century?

With the recent uproar surrounding President Obama’s executive order declaring Venezuela a national security threat, it is worth reading up on how this Latin American country has changed since the end of the 20th century. This excerpt from Venezuela: What Everyone Needs to Know by Michael Tinker Salas examines the impact of the election of Hugo Chávez on Venezuelan politics.

How did the election of Chávez transform foreign relations?

Having functioned largely in the US political sphere of influence for most of the twentieth century, Venezuela sought to chart its own course in international affairs after the election of 1998. Since 1999, the Venezuelan government has pursued new foreign policy initiatives, advanced the idea of a multipolar world, assumed a greater role on the international stage, and promoted hemispheric integration. These positions clashed with long-held assumptions about the nature of Venezuela’s relations with the world. Critics contended that many sectors in society conflated the oil economy with their own sense of nationalism; the oil economy—with the bulk of Venezuela’s production destined for US markets—necessitated good relations with Washington.

Efforts to alter how the nation conducted its foreign affairs heightened tensions between the government and a conservative opposition. Venezuelan relations with the United States did not solely concern the nature of international relations; it also embodied important cultural and social symbolism. For upper- and middle-class sectors of society, relations with the United States expressed acceptance of a way of life, defined largely by US values, which served to affirm their own social standing. By not favoring relations with the United States, the Venezuelan government no longer legitimated and promoted these perceptions, but rather became a vocal critic of this lifestyle. The changing nature of the relationship also raised concerns in Washington, long accustomed to having Venezuela follow US initiatives in foreign affairs.

The constitution of 1999 outlined the objectives of Venezuela’s new foreign policy. Besides traditional pronouncements about the country’s sovereignty in international matters and nonintervention, it explicitly promoted policies that favored the integration of Latin America and the Caribbean, with the goal of “creating a community of nations that would defend the economic, social, cultural, political, and environmental interests of the region.” In addition, Venezuela refused to be party to any international agreement that recognized the authority of a supra-national judicial body to resolve disputes, a direct reference to treaties with international lending institutions such as the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank.

Guided by the proposition of a multipolar world, the Venezuelan government sought to establish equitable relations in a post-Cold War era. It affirmed Latin America’s role on the world stage and used this approach to prevent the isolation experienced by previous leftist governments such as Guatemala in the 1950s and Cuba in the 1960s. Hoping to strike a balance in its international affairs, Caracas endorsed economic arrangements with China, Cuba, Iran, and Russia, especially in areas such as health, telecommunications, auto manufacturing, oil explorations, and the production of machinery. The Chinese constructed and launched into space Venezuela’s two orbiting telecommunication satellites. Iran operates a tractor and car factory in the country and the Russians have become one of the leading arms suppliers of the Venezuelan military. In the United Nations, Venezuela has openly sought the revolving position in the United Nations Security Council. As part of a policy to promote South-South relations, the country expanded diplomatic relations with most countries in Africa and in 2009 hosted the Africa-South America summit.

In the first decade of the 21st century, the Venezuelan government became one of the most fervent critics of Washington’s sponsored Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA), asserting that it would heighten and institutionalize inequalities already present in economic relations between Latin America and the United States. As evidence, critics of the FTAA pointed to the convulsions evident in Mexico after it signed a similar agreement: the devastation of its rural sector, the outmigration of millions, and the monopolization of the economy by a handful of families. By 2005, Venezuela’s position on the FTAA increasingly found support among a majority of South American nations.

Image Credit: “Canción patriótica” by Cristóbal Alvarado Minic. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How has Venezuela’s foreign policy changed in the 21st century? appeared first on OUPblog.

No cure for the diseases of American democracy?

The American political system is a mess, but don’t expect that introducing reform and changing how the government is structured will cure all the diseases of American democracy. There is no magic bullet. No simple panacea.

It would be difficult to argue that things are going well in Washington today. Every week, it seems, a new report comes out of Washington that raises questions about the behavior of our government, be it the near shut down of the Department of Homeland Security or House Speaker Boehner’s controversial invitation to the Israeli prime minister to address Congress or the resignation of Rep. Aaron Schock, who stepped aside after a spate of media stories appeared raising questions about the Downton Abbey-styled décor in his office.

Certainly, the American public believes things are not going well. Surveys by the Pew Research Center, Gallup, and others have long noted the public’s dissatisfaction with American government, especially Congress. In February, the Rasmussen Poll found that only 16% of Americans believe that Congress is doing a good job. The ironic aspect of the poll is that the results were reported in the media as a positive sign, for this was the best approval rating of Congress since 2010. Apparently, 16% is the new good.

What can be done? An endless number of proposals have been put forward by political reformers, editorial writers, and bloggers on how to fix American politics. One of the major targets is strengthening campaign finance rules. There may be no issue that is perceived as more damaging to American politics by many than the Citizens United decision, which opened the spigot to unlimited spending in elections by corporations, unions, and other associations.

Obama Health Care Speech to Joint Session of Congress. Lawrence Jackson (whitehouse.gov. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Obama Health Care Speech to Joint Session of Congress. Lawrence Jackson (whitehouse.gov. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Of course, campaign finance is but one problem targeted by reformers. Many reformers focus on the polarization in American politics, advocating for changes that would reduce polarization by limiting the power of political parties or expanding the electorate. Conversely, others argue that polarization can be reduced by actually strengthening party organizations or by placing limitations on individual campaign contributors, who tend to be more ideologically extreme.

Rather than campaign finance and polarization, others focus on making changes within Congress to reduce gridlock, including placing presidential nominations on a fast track, ending the filibuster, and docking members’ pay if they do not pass the budget on time. A recent article in the Washington Monthly called for strengthening Congress’s capacity as a means for it to counter the influences of corporate money and excessive partisans.

While the American political system is clearly a mess, we should be as skeptical of reform proposals as we are with the current status quo.

One reason to be skeptical is that reforms do not always deliver what they promise. In some cases, the proposed reform is simply not going to attain the goals touted by their evangelical supporters. Take term limits for example. At times advocates argue that term limits will make legislators more attentive to the voters in their districts, while at other times they argue that term limits will make legislators less beholden to local interest and thus better able to address national problems. You can’t have both. Or take campaign finance reform. It seems like the flow of money to campaigns is like a sieve: once you plug one hole, the money will find another in which to flow.

The reason for skepticism, though, goes beyond questioning whether reforms will work. One also has to be skeptical because no one particular political structure is able to attain everything that people want out of a democracy. The reason for this is simple: what we want is conflicting. We want a government that works efficiently to solve problems, yet we also want to make sure that minority views get considered. We want to limit the involvement of money in election campaigns, yet we also want greater voter turnout and better informed voters. Or as in the case of term limits, we want legislators to pay attention to their voters back home, but we also want them address broad social problems.

This is not to say that the problems in our political system are not real and significant. Certainly, excessive corporate money in politics means that some voices are being better heard than others, which goes against the democratic ideal of fair representation. And clearly, a government that is so mired in political polarization and gridlock is one that cannot address the nation’s most pressing problems.

Instead, what it is saying is that we shouldn’t expect that introducing reform will automatically cure all of America’s ills. Even the best designed law to limit money in politics can also reduce voter awareness and turnout, limit expression, and in some cases actually dampen electoral competition rather than improve it. Reforms to increase government efficiency may limit the ability of political minorities to have a say in our laws. Even something like strengthening Congress’s capacity, which may seem a simple solution, can have contradictory effects. While it may improve Congress’s ability to challenge corporate money, it will also likely enhance Congress’s ability to challenge the White House, which may mean more conflict and a less efficient government.

This doesn’t mean we should give up on reform. Rather it means we need to look critically at reform proposals before jumping on a bandwagon in support. Even more important, it means we need to weigh the benefits of proposed reforms against the costs, because there always will be some.

Heading image: United States Capitol. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post No cure for the diseases of American democracy? appeared first on OUPblog.

The Erdős number

The idea of six degrees of separation is now quite well known and posits the appealing idea that any two humans on earth are connected by a chain of at most six common acquaintances. In the movie world this idea has become known as the “Bacon number”; for example Elvis Presley has a Bacon number of 2 since he appeared in a film with Edward Asner who in turn appeared in a film with Kevin Bacon.

The mathematical equivalent of the Bacon number is the “Erdős number”. Paul Erdős (1913-1996) was the most prolific mathematician of recent times with more than 1,500 papers, including more than 500 co-authors. The Erdős number now describes how close you are to Paul Erdős in terms of mathematical publications. So, for example, Robin Wilson has an Erdős number of 1 because he co-authored a paper with Erdős, whereas John Watkins has an Erdős number of 2 because he co-authored a paper with Robin Wilson (incidentally he co-authored a paper with Peter Cameron who also has an Erdős number of 1). Even the physicist Albert Einstein had an Erdős number of 2, though this is hardly his greatest claim to fame.

Paul Erdős, Budapest 1992, by Kmhkmh. CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Paul Erdős, Budapest 1992, by Kmhkmh. CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons. Having a low Erdős number is a matter of great pride for mathematicians. The highest known is 7, although there are also mathematicians who had no connection with Erdős and whose Erdős number is defined as “infinity”. Erdős was so open to working with other mathematicians that it will forever be a deep regret for those of us whose Erdős number is greater than 1 that we never collaborated on a paper with him. Even the great Giancarlo Rota shared this same regret and recalled an evening when he mentioned to Erdős a problem he was working on and Paul provided a hint that eventually led to a complete solution. While Erdős was appropriately thanked in the paper’s introduction, Rota always regretted that he did not include Erdős as a co-author.

Erdős was indeed a genuine mathematical prodigy, and at the age of 19 gave a new and gorgeously simple proof for a well-known theorem about numbers: between any number n and its double 2n there is a prime number. This was his very first mathematical paper.

His supposed obsession with mathematics to the exclusion of anything else in life is now legendary. With no real home base, he traveled the world, staying with friends, visiting math departments, and attending mathematical conferences. He always looked the same, in a suit and a white shirt with an open collar. But, inevitably, he could always be found seated on a couch talking to someone about a mathematical problem.

At conferences he almost always gave a version of a one hour talk he called “open problems” in which, without notes, he would discuss in great detail the current open mathematical problems he was interested in. For many of these problems he would offer monetary rewards for solutions, $100 for a fairly routine problem or perhaps $1,000 or more for a problem he considered especially difficult or important. He knew he could never be able to pay for solutions for all of these problems if they were actually solved, but he also knew that most of them would remain unsolved during his lifetime.

There are countless anecdotes that capture the spirit of Paul Erdős. He could be whimsical: at one conference he announced that he was 81 and most likely a square for the last time. Another time he visited a friend at Santa Clara University in California and upon arrival asked his host “what was the temperature in this valley during the Ice Age?” But, the best stories are from his closest mathematical friends with whom he stayed throughout the years. Many of these have a central theme: at some point in the early morning, about 2 or 3 am, Paul would wander into their bedroom, and with no preamble whatsoever, say something like “about the problem we were discussing last night, what if …”.

The famous neurologist and writer Oliver Sacks said of Paul Erdős: “a mathematical genius of the first order, Paul Erdős was totally obsessed with his subject — he thought and wrote mathematics for nineteen hours a day until the day he died.”

Featured image credit: At the math grad house by kimmanleyort. CC by ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The Erdős number appeared first on OUPblog.

The myth of the pacific woman

The flow of girls in particular from the safety of Britain into the war zones of the Middle East causes much hand-wringing. A report from the Institute for Strategic Dialogue says one in six of foreigners going to Syria and Iraq are women or girls.

The march of women warriors into the Al-Khansaa brigade and other military groupings goes against a deep seated myth: that women as a gender are anti-war to a far greater extent than men. This remains to be demonstrated, though the notion has a long history.

One of the principal reasons in the nineteenth century for the opposition to women’s getting the vote was their presumed weak and pacific nature. A nation where women had political power would be at the mercy of more martial nations, it was said, as women would not go to war.

The supposed peace-spreading effect of the women’s ballot was also a profound belief of the suffragists themselves. It was promoted as a reason why women should have the vote, for they would end wars. Mary Stritt, president of the German Woman Suffrage Society, wrote to the International Woman Suffrage Alliance in February 1918, near the end of the First World War: “When responsibility for the welfare of the people and humanity is in our hands, in the hands of the mothers, there can be no return to the horrors we have had to experience.” It was a statement markedly deficient in predictive power, as demonstrated by the history of Germany after the enfranchisement of women later that year.

The pacifism of most suffragists – or at least of their leaders – really should have been an overwhelming problem for gaining women’s suffrage once the First World War started. In fact it became a problem for the suffrage organisations, causing divisions in the US and UK movements. As soon as danger threatened, support for the war became stronger than any principles most suffragists held for pacifism. Carrie Chapman Catt, head of the National American Woman Suffrage Association in 1917, became a supporter of the war against her previous conviction, for she had been a lifelong pacifist.

Allied women in Paris to plead for international suffrage. Underwood & Underwood, Photographer War Department. US National Archives and Records Administration. 27 February 1919. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Allied women in Paris to plead for international suffrage. Underwood & Underwood, Photographer War Department. US National Archives and Records Administration. 27 February 1919. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. War work was eagerly sought out by suffrage women who could thereby respond to the argument that women should not vote as they did not bear arms. In a modern war far more needed to be done to maintain forces in combat than bearing arms. Catt pledged that the NAWSA would stand by the government and she served on the Women’s Committee of the Council on National Defence.

On the other hand, Jeanette Rankin from Wyoming, the first woman senator, felt obliged as a strong pacifist to vote against US entry into the war, which led to suggestions that women were unpatriotic. A least she had the courage of her convictions. It is good to see a politician stand by the principles by which they have risen, and not jettison their values when it becomes challenging to hold them.

In the UK pacifism wasn’t just dropped by the women’s suffrage leaders, pacifists were purged and expunged from history. Millicent Fawcett worked to expel the “poisonous pacifists” from the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies which she led. In 1915 pacifists had been in the majority on the NUWSS executive but even their names were excluded from the official history, The Cause. Emmeline Pankhurst was such an enthusiastic supporter of the war that the government that had previously imprisoned her now paid the bill for a ‘Call to Women’ demonstration organised by the suffragettes.

As time passed and women took positions of political power previously held exclusively by men, the question of women as war leaders was put to the test. It emerged that when they had the opportunity to wage war, women leaders did so with no less reservation than men. The first women leaders of nations: Sirimavo Bandaranaika of Ceylon, Golda Meir of Israel, Indira Gandhi of India, and Margaret Thatcher of Britain were not notably pacific; their governments directed the armed forces as they felt necessary. Gandhi and Thatcher were markedly decisive war leaders.

It may be that the schoolgirl jihadists are not a terrifying manifestation of a new horror of modernity, but a realisation, a long time in coming, that women are no more pacific than men, whatever their culture. Perhaps we should not be surprised, when looking at any playground: mean girls don’t get any less mean because they wear a yashmak.

The post The myth of the pacific woman appeared first on OUPblog.

Thoughts on the crucifixion of Jesus

As is well known, the death of Jesus was a problem. How do you explain that your elevated hero ended up dead on a Roman cross? Or, as Paul famously put it, “we proclaim Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to gentiles.”

Trying to reconstruct in any detail the historical realities which may (or may not) have generated the story of the Passion is extremely difficult. Even if we side-stepped the problem of how the information about a trial or trials might have been acquired, the death of Jesus was to undergo relentless interpretation and reinterpretation. It might be possible to argue that Jesus did something in the Temple that worried certain people at a potentially tense festival of Passover (celebrating, of course, the escape from imperial bondage). This, it might be argued, led to his execution for — what the authorities at least claimed — sedition. Perhaps, but even these things are difficult to establish with any degree of certainty.

But at the same time we might embrace the role of relentless interpretation and reinterpretation in historical reconstruction, even when ostensibly discussing the historical Jesus. For instance, once the potentially controversial idea of the death of the elevated figure was known then how was this to be interpreted? One way (and one that the earliest followers obviously chose) was the idea that, borrowing from long-established ideas of martyrdom (e.g. the celebrated Maccabean martyrs), Jesus’ death had some sort of redemptive function. Much, of course, has been written on this.

Other interpretations were happening too. Part of the problem was that Jesus’ death involved questions of masculinity, as Coleen Conway has shown in detail. Jesus could, after all, be understood as another emasculated, passive victim at the hands of the Empire. There are indications of this sort of understanding in Mark’s Gospel. Others were less prepared to present Jesus so emasculated; Paul, for instance, constructs Jesus in more manly and heroic terms. And we should not necessarily succumb to the old temptation of layering these interpretations, as if the emasculated construction came first, followed later by the masculinizing of Jesus’ death. This theoretically could have happened, and indeed may have happened for all we know. Nevertheless, different, perhaps contradictory constructions could have co-existed from the moment that Jesus’s crucifixion became clear. This sort of scenario has to be taken as a serious possibility given that so much interpretation of Jesus’ death was happening so soon and among different audiences.

Crosses, CCO via Pixabay

Crosses, CCO via Pixabay Indeed, writers could hold seemingly contradictory ideas together without it being much of a problem. Mark’s Gospel, after all, can simultaneously present Jesus in more heroic and domineering language. The problems of gender construction and controlling problematic gender allegations would have been a problem in Galilee from around the time Jesus was understood to be active. The building and rebuilding of Tiberias and Sepphoris would have changed perceptions of traditional patterns of households and led to displacement, as Josephus indicates in the case of Tiberias. Halvor Moxnes argues that this would have led to challenges to traditional understandings of masculinity in Galilee. For instance, it might be thought that a son should be heading a household rather than wandering around Galilee. Did this happen in the case of the historical Jesus? Again, it is possible but we would be on firmer ground by thinking more in terms of this as a social history of ideas or tradition rather than trying to prove whether such ideas do or do not go back to Jesus.

Problematic as all such gender chaos may have been for the Jesus movement, it could not escape the ideologies associated with imperialism, whether they related to gender or class. The tradition in Jesus’ name may have presented him in terms of an alternative family but it could not escape the language of traditional family, with, if anything, the most domineering father figure imaginable. Jesus may have been understood as a victim of Roman imperial violence but it was likewise understood that a new imperial order would soon be established on earth, which would wipe out Rome’s dominance and in which Jesus would play a domineering role and the right people would benefit. Certainly there were promises of peace and prosperity but all dictatorships make such promises, do they not?

The post Thoughts on the crucifixion of Jesus appeared first on OUPblog.

Easter for a non-believer

I have ambivalent feelings about Easter. I am sure I am not alone in this attitude towards the greatest of events on the Christian calendar, especially among people who grew up, as I did, in intensely religious (and loving) families but who have long put their Christian beliefs behind them. As it happens, my family were Quakers and that religion does not mark out the church festivals. But I went to a school that had a great musical tradition and each year there was a performance of one of the Bach Passions, alternating the St Matthew with the St John. No one could have them as a major presence during adolescent years without echoes in some sense resonating through the rest of one’s life. A fact that, I should say, gives me ongoing joy, for each year around this time, if only on disc, I listen to one or other or both of these incredible works – and end, if not in tears, then very close.

And yet, if I look intellectually – I am a professional philosopher – at the Sacrifice on the Cross, not to mention the Resurrection, I start to have grave doubts. I am not so much concerned about the miracle aspect – although I do think rather daft those folk who spend so much time trying to prove the historical authenticity by worrying about the stone and so forth. Why not simply say that the disciples felt in their hearts that their Lord was risen, and leave it at that, whatever the psychological reasons? I am concerned about the whole point of the Sacrifice.

Assume that we are all sinners and that we need saving. I personally cannot see why the misdeed of one person, Adam – real or symbolic – should condemn the rest of us to a life of sin. And that is apart from what seems to me to be a bit of an overreaction by God. A naïve chap, sitting stark naked in a garden, seduced by a wily reptile, grabs a piece of fruit, and the whole of humankind is condemned for all eternity? God is starting to sound like some of the legislators in my home state of Florida, who argue that it is perfectly appropriate to lock up troubled fourteen year olds for life, without hope of parole, ever.

Even worse is why a death on the Cross should do the trick. It all seems a bit pointless to me. If Jesus had been an aid worker in Pakistan and had been killed while trying to give polio vaccines to kids I could start to see it. I don’t think Jesus should have been crucified for being a rabble rouser, but I don’t see that what he did was so very great – especially since the apocalyptic language of the gospels rather suggest that until virtually the end Jesus thought that God was going to rescue him.

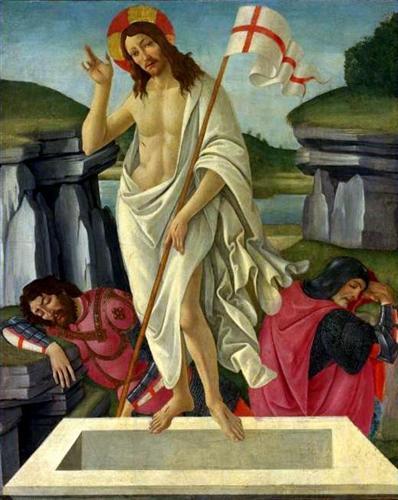

The Resurrection of Christ, by Sandro Botticelli 1490, Public Domain via WikiArt

The Resurrection of Christ, by Sandro Botticelli 1490, Public Domain via WikiArt Nor do I buy the fact that the sacrifice was the greatest moral act ever. I don’t think it even starts to compare with Sophie Scholl, one of the White Rose group in Germany during the War who passed out pamphlets against the Nazis and who was discovered, condemned and lost her life on the guillotine. As she went to her death, she said: “Such a fine, sunny day, and I have to go, but what does my death matter, if through us, thousands of people are awakened and stirred to action?” That for me is an act of moral bravery before which I can only bow, humbled.

Most importantly, why should Jesus’ act do anything for my sins? We have a group of kids all in trouble and one, who was blameless, steps forward and accepts the punishment. I don’t think that gets the rest of us off the hook at all. If anything we are worse. If we have done wrong, then we and we alone are responsible for our sins. God can forgive us or not, but keep Jesus out of it, please.

And yet – again! Emotionally I cannot escape from my Christian heritage, nor do I very much want to. I did not bring my kids up as Christians and I think that was the right thing for me to do. But I do feel a bit guilty that at some level they are missing out on something. What? For me, whatever the theological and philosophical issues, Easter is truly a time when I do stop and ask myself about meaning and sacrifice and duties to others.

I don’t think it has to be Easter per se. As one who came to North America, in major respects Thanksgiving – a festival that was new to me – is more significant, as I celebrate the love and kindness that people showed to me, a stranger to their land. But I do think it is important to have those times in one’s life when one pauses and takes stock – realizes what one has done and what one has not done and whether things can be improved. As I listen to those great Bach pieces, that for me is what they make me think and reflect. And for that I am very glad.

I don’t want to end on too serious or preachy a note. I am old enough that, to show my hatred of nuclear weapons, I marched around 1960 with the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament at Easter from Aldermaston. Ban the Bomb! I am not sure we did much good, but they were wonderful times of friendship and fun – although after four days of sleeping in one’s clothes on floors one was, let us say, a bit fruity. Easter for me therefore is also memories of being young and how good it is to be alive and have friends and have missions – not to mention, the virtues of soap and water! All in all, non-believer though I may be, I love Easter. And now back to the music.

Featured image credit: Easter-Eggs-1, by Lotus Head from Johannesburg, Gauteng, South Africa. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Easter for a non-believer appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers