Oxford University Press's Blog, page 681

April 3, 2015

Oral histories of student veterans at Monmouth University

A few months ago, we asked you to tell us about the work you’re doing. Many of you responded, so for the next few months, we’re going to be publishing reflections, stories, and difficulties faced by fellow oral historians. This week, we bring you another post in this series, focusing on an oral history project from Melissa Ziobro. We encourage you to engage with these posts by leaving comments on here or on social media, or by reaching out directly to the authors. If you’d like to submit your own work, check out the guidelines. Enjoy! –Andrew Shaffer, Oral History Review

“There’s really no excuse for failure, really. You can’t really come up with a reason as to why you didn’t get something done, other than you just didn’t do it. So that’s kind of helped me complete a lot more of my assignments than I probably would have done (before my military service).”

Interview 1: 21 March 2013

USMC, Enlisted, 2005-2010

In the Fall of 2012, I decided to offer to conduct oral history interviews of Monmouth University’s student veterans to donate to the Library of Congress Veterans History Project. I hadn’t conducted any oral histories since leaving government service the prior year. I missed the craft, and thought this a truly worthwhile endeavor.

The concept seemed full of potential and I thought it would capture valuable experiences for the greater historical record. I assumed (based on my experience as a civilian historian for the Army) that few, if any, of these men/women had had their stories preserved previously, given that the military’s oral history programs often focus only on senior leaders and not the “boots on the ground.” I thought the program might also help to show the student veterans that the University recognized their unique identity and cared about their military experience. Lastly, a comprehensive analysis of the completed interviews might show the University how better to serve its student veteran population. At the time I devised and first started researching the idea of a student veteran oral history program, I found (to my pleasant surprise) that similar ones existed at several institutions around the country, perhaps most notably in the state of Kentucky university system.

It is one thing for a University like Monmouth to choose to start a program to collect these oral histories, but I’ve found that it is another thing entirely to entice student veterans to sit for an interview. I’d say the Department of History and Anthropology has a good overall working relationship with the Student Veterans Association (SVA), with several of our faculty members regularly attending SVA events. I even won first place in their chili cook-off last year! Oddly enough, although I won a fantastic trophy, my victory didn’t have the vets signing up for interviews in droves.

While the Student Veterans Faculty Coordinator and SVA President have both endorsed the oral history program, only a handful of interviews have been conducted to date. I realized at the outset that many student veterans might be reluctant to participate, particularly those who had served recently and didn’t want to re-hash old wounds. I have taken great pains to explain the process and assure the student vets that they don’t have to discuss anything that might make them uncomfortable. I also realized that many simply might not have the time to sit down with me – and that’s fine. I have found participation even lower than expected, though.

I’d love to hear from anyone conducting similar work. In the meantime, I’ll just continue advertising the program at the start and end of each semester to let the student vets know I’m there if ever they want to share and document their experiences.

Discussion Questions:

Has anyone considered a student veteran oral history project for their campus and decided against it? Why? How do you advertise your student veteran oral history programs? Do your student veteran oral history interviews focus on just their military service? On just their college career? Or both? Has anyone supervised a seminar course in which students learning oral history interview student veterans? I personally felt this ill-advised, but would love to hear your thoughts. How have you used your student veteran oral histories? Monographs? Campus newspaper articles? Social media? Any reports to the campus administration?For additional interview excerpts, or more information about the project, visit the Student Veteran Oral History Project at Monmouth University. If you’d like to chime into the discussion, comment below or on the Oral History Review Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, and Google Plus pages.

Headline image credit: Monmouth University, West Long Branch, NJ. Photo by Sinead Friel. CC BY 2.0 via sineadfriel Flickr.

The post Oral histories of student veterans at Monmouth University appeared first on OUPblog.

Residency training and social justice

It is axiomatic in medical education that an individual is not a mature physician until having learned to assume full responsibility for the care of patients. Thus, the defining educational principle of residency training is that house officers should assume the responsibility for the management of patients. To acquire this capacity, interns and residents evaluate patients themselves, make their own decisions about diagnosis and therapy, and perform their own procedures and treatments. House officers assume responsibility in a graded fashion: the more senior the resident, the more responsibility allowed. For safety and learning purposes, residents are supervised by and accountable to their attending physicians.

The result is a system of training in which house officers receive major responsibilities for the care of patients. They typically are the first to evaluate the patient on admission, speak with the patients on rounds, make all the decisions, write the orders and progress notes, perform the procedures, and are the first to be called should a problem arise with one of their patients. The distinctive feature of the system is that residents are given full responsibility for the diagnosis and treatment of seriously ill patients. Such responsibility allows house officers not only to develop independence but also to acquire ownership of their patients-the sense that the patients are theirs, that they are the ones responsible for their patients’ medical outcomes and well-being. Medical educators have long recognized that the assumption of responsibility is the factor that transforms physicians-in-training into capable practitioners.

The ethical challenge of residency training is to find a way to balance the educational needs of residents, who require increasing independence, with the safety needs of patients, who benefit when being cared for by the most experienced physicians and surgeons available. The learner will benefit, as will patients of the future, when the least experienced resident is permitted to perform the appendectomy or cholecystectomy. The needs of the patient at hand are best served when the most experienced surgeon available performs the operation. This tension has always afflicted the residency system, but during the past few decades it has become particularly intense, as hospitalized patients have become much sicker and medical practice ever more powerful but dangerous. Mistakes of omission and commission potentially carry greater consequences today than before.

Operation by frank23. CC0 via Pixabay.

Operation by frank23. CC0 via Pixabay. The assumption of responsibility has thrived as the dominant principle of residency training because graduate medical education in the United States developed within a system of charity care. It is this historical fact that has allowed the residency system to provide interns and residents the opportunity to assume major responsibilities in patient care. The United States, like the rest of the industrialized world, has always used indigent patients as “clinical material.” These patients, in keeping with a long-standing Western tradition, receive free care in exchange for their participation in clinical education and research. In contrast, paying patients are used in much more limited ways in medical education. Professional responsibility for their care belongs to their personal physicians, and this responsibility is only sparingly delegated. Only the medically indigent patients on the “teaching service” afford house officers the full opportunity to develop management plans, make important therapeutic decisions, and perform surgery and other procedures.

The residency system-and, specifically, the principle of graded responsibility-clearly serves the national interest. There is no avoiding the moment when a doctor operates or assumes the management of complex patients for the first time without the direct supervision of a more experienced physician. From this perspective, the only question before medical education and the public is the circumstances in which this would happen. There has always been unanimity on this matter. The profession and public have both believed that it is far better for this moment to occur as part of the graded responsibility of residency, where help can be immediately summoned, rather than to wait until physicians are in practice, where help might not be immediately available and where mistakes from inexperience on their unsuspecting patients would pass undetected. Medical educators have always pointed out the importance of appropriate supervision and the immediate availability of help to residency training, as well as the high quality of care provided by the resident staff.

Nevertheless, most resident learning continues to take place with less advantaged patients. Though the number of insured patients has risen as private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, and most recently, the Affordable Care Act have taken effect, the number of uninsured and medically indigent patients remains large, and it is with such patients that medical and surgical residents continue to derive their major educational experiences. Most medical teaching and learning continues to occur on the vulnerable those with lower incomes and less social status. This is in marked contrast to a true one-class system of care, where all patients would be used equally in teaching. In such a system, the surgical resident might operate on the bank president, while the patient on Medicaid would have the same opportunity as a wealthy individual to have his operation performed by the hospital’s most senior surgeon.

In short, neither medical educators nor the public have figured out a way to involve private patients more fully in residency training. Some educational leaders have tried, arguing the quality of care provided by residents at major teaching hospitals is as good as or better than that provided by private physicians. However, most private physicians like maintaining control of their own patients, most well to-do patients do not wish residents to replace their private doctors, and there is little national will at the moment to change the system. A modified two-class system of care continues. Part of the challenge of achieving greater social justice in America in the future will be to determined procedures for using all classes of patients equally in medical education.

Heading image: Doctor care by DarkoStojanovic. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Residency training and social justice appeared first on OUPblog.

Anthony Trollope and ‘The Story of a Cheque for £20, and of the Mischief Which It Did’

One of the more affordable forms in which it is possible to acquire the manuscript signatures of Victorian writers today is the used cheque. Quantities of these minor, sometimes biographically revealing, documents left the archives of banks and went onto the open market in the 1990s; they now circulate through the catalogues of manuscript dealers and in the online pages of eBay, some of them leaving traceable e-narratives of their patterns of ownership.

The particular cheque described in the Explanatory Notes to the new edition of The Last Chronicle of Barset is only one of several Trollope cheques currently on the market. It records a payment, on the Union Bank of London, of £205 to Frederic Chapman, dated 17 December 1868. As the note to the new edition points out, Trollope has crossed out the ‘or bearer’ option for the payee, and substituted ‘order’, meaning that the bank is instructed to pay only Frederick Chapman himself or a specific person Chapman endorses in his place. The purpose (not of course stated on the cheque) was to secure acquisition of a third stake in Chapman and Hall publishing company for Trollope’s son (you can learn more from this earlier dealer’s description). The cheque was presumably acquired at auction by its present owner who is now selling it again on eBay, priced at £329-99. Some reader of this blog may even want to bid.

Early Edition of The Last Chronicles of Barset from 1867. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Early Edition of The Last Chronicles of Barset from 1867. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. This and similar surviving examples of Trollope’s day-to-day financial practices show him exercising a basic precaution in the transfer of money (like crossing out ‘or bearer’) that would have saved the protagonist of his novel a world of trouble. The Last Chronicle is, like most of Trollope’s fiction (and indeed most Victorian realist fiction), acutely alert to how money operates in the world to shape individual and collective narratives for good and ill. Often, the main novelistic interest shown in money is moral and political (Trollope’s own satire The Way We Live Now is a good example). But in this, the last of the Barsetshire series, Trollope’s focus is more intimate, and much closer to the plot gearings and the mood of tragedy. For Josiah Crawley, impoverished cleric, unable to scrape a living in the under-remunerated curacy of Hogglestock, the unthinking use of a cheque made out to its payee ‘or bearer’ (not crossed out, and therefore able to act in effect as cash) is a personal disaster. It brings him under suspicion of theft, and (in his own eyes) puts his sanity in doubt, since he cannot recall how he came by the cheque in the first place.

Editing this novel, one becomes aware how far the technicalities of the financial plot may be moving out of memory for readers today—though one could readily enough substitute modern forms of payment equally capable of giving rise to suspicion of misappropriation of funds (the online fraud; the computer error). The financial instruments change, but the personal predicaments they may generate are strikingly persistent. Trollope’s working title for the novel was, for a while, ‘The Story of a Cheque for £20, and of the Mischief Which It Did’—which would have made for a cluttered title page, and put Victorian readers in expectation of a much more conventional ‘it-narrative’: the picaresque adventures of a cheque, circulating through society and articulating, for us, a moral portrait of that society. This isn’t that kind of novel: it is much less programmatically moral, much more psychologically subtler, and (its plot technicalities notwithstanding) it is a remarkably topical portrait of how far our dealings with money may still expose us to public, and the most intimate forms of private, scrutiny.

Heading image: An 1870 Bill of Exchange payable in London with British Foreign Bill revenue stamps attached, Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Anthony Trollope and ‘The Story of a Cheque for £20, and of the Mischief Which It Did’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Good Friday: divine abandonment or Trinitarian performance?

There are scenes in the Bible that cause a visceral reaction for even the most disinterested reader. As we view the Garden of Gethsemane in our mind’s eye, we see one of Jesus’ closest companions, Judas Iscariot, leading a band of men. He smiles broadly, “Rabbi!,” greeting Jesus with a kiss. The kiss, that universal sign of intimacy and affection, lands on Jesus like a knife twisting in the back.

Even though it is a stock feature of literature, cinema, and life, like those passing by a car wreck, we can’t seem to avert our eyes when we see betrayal — even when its appearance is an unsurprising cliché. But as cold-hearted as Judas’ kiss might be, it is not the kiss that causes chills. It is Jesus’ response, “Friend, do what you came to do” (Matt. 26:50). The traitor is embraced as friend, and Jesus urges Judas to complete the betrayal, even though he knows the agony of the cross awaits.

A couple scenes later we find ourselves riveted by betrayal once more. As his limbs are stretched on the cross, Jesus flings out the words, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Matt. 27:46). We stare in fascinated horror. Surely God has not gone the way of Judas? Even if Jesus’ words are not themselves accusatory, we cannot seem to avoid sitting in the judge’s seat, while we place God in the dock. A weight of unfairness, of divine unfairness, is heavy in the air.

If God, the one Jesus called Abba-Father, truly did forsake Jesus — the Greek verb in question, enkataleipō (Hebrew = ʿāzab; Aramaic = šābaq), entails active and intentional movement away from — then why would the Father abandon the Son at his moment of sharpest need? Was it a final test of the Son’s obedience? An excruciating but essential self-emptying for the Son? Could it be that the holy Father could not stand to gaze upon the Son as he carried the ugly sin of the world? Reinforced by lines such as “the Father turns his face away” in popular hymnody, the latter remains a common explanation among professional scholars and pew-filling Christians. For theologian Jürgen Moltmann in his The Crucified God, this abandonment is a genuine, radical separation between the Father and the Son in which God ultimately forsakes his very self. According to Moltmann, in so doing God is able to take creaturely suffering into his own divine self-life, to suffer alongside creation. Yet these theological speculations assume rather than prove that God truly did temporarily forsake Jesus. In light of evidence in the Gospels that Jesus knew that the Father would not abandon him (John 16:32) and that he would rescue him on the other side of the grave (Luke 9:22; 13:32; 17:4–5; 18: 33 and parallels), perhaps we are justified in searching for a different solution.

Crucify, by Erik Aldrich, CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr

Crucify, by Erik Aldrich, CC BY-ND 2.0 via FlickrAs we investigate the scene of the divine treason more carefully, our impression that this is betrayal begins to melt away as we read the Jewish Scripture, the Christian Old Testament. For Jesus is not giving a spontaneous accusation, but is uttering the first lines of Psalm 22, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” Could it be that Jesus was voicing his feelings of despair even while expressing hope — that Jesus was entering a well-rehearsed script, beginning a theodramatic performance? Although the point has been under-appreciated among scholars and theologians, this is precisely how the earliest Christians who interpreted Psalm 22 seem to have understood it: the Gospel-writers, the author of Hebrews, Clement of Rome, Justin Martyr, and others.

That is, Jesus and others seem to have believed that David as the inspired author of a psalm could slip into an alternative guise, adopt a different person, and speak as that person (cf. esp. Acts 2:30–31; Justin 1 Apol. 36.1–2). For instance, when Jesus interprets Psalm 110 (in Mark 12:35–37 and parallels), he points out that David is not God’s ultimate dialogue partner with respect to the words, “The Lord said to my Lord, ‘Sit at my right hand until I make your enemies a footstool for your feet,’” because the person addressed by God is described as “my Lord” by David. Jesus carefully points out that David said these words while speaking “by the Holy Spirit” (Mark 12:36), which I believe (in conjunction with other evidence) suggests that Jesus was focused on David’s prophetic ability to adopt a different “person” as the Holy Spirit supplied the script to be performed. If this is the case, then Jesus seems to have made intriguing proto-Trinitarian assumptions in his interpretation of what Christians call the Old Testament. For Jesus, a Father-Son-Spirit script was written by the prophets long ago in anticipation of his own future actualizing performance. Many other examples in which Jesus and others use this theodramatic reading technique (prosopological exegesis) could be adduced.

So if for Jesus, David spoke the words, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Ps. 22:1) from the person of the Christ, and Jesus understood himself to be the Christ who was now incarnating the script, then what did Jesus think the performance would entail? And how would it end? The psalm itself gives the story. The mocking crowd would appear, sneering, “He saved others; let him save himself if he is the Christ of God, the chosen one!” (Luke 23:35) and “He trusts in God; let God rescue him now, if he wants him!” (Matt. 27:43; cf. Ps. 22:8; 1 Clem. 16.15–16). The words, “they divided my clothes among themselves, and for my garment they cast lots” (Ps. 22:18) would come to pass (Mark 15: 24 and parallels; cf. John 19:24), as would other specific details, “my tongue is stuck fast in my throat” and “they pierced my hands and my feet” (Ps. 22:15-16).

Yet this would not be the end of the story. Jesus would be rescued (cf. Ps. 22:21 with Ps. 22:22). And this rescue allowed the Christ to say, “I will tell your name to my brothers; I will sing your praise in the midst of the assembly. You who fear the Lord, praise him! . . . he did not turn his face away from me, and when I cried to him, he heard me” (Ps. 22:22–24). We find an echo of this in Hebrews (paraphrasing):

Jesus (speaking to God the Father): “I, Jesus, will proclaim your name, O my Father, to my brothers, in the midst of the congregation I will sing your praise.” (Heb. 2:11–12 citing Ps. 22:22)

Indeed as Jesus leads the congregation in acclaiming God, the circle of praise widens so that not just Israel, but “the ends of the earth” and “all the families of the nations” worship God (Ps. 22:27).

Just as with Judas’s betrayal, I find myself gazing in fascination at Jesus’ words, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” This time I stare because what appears to be a betrayal is not one at all, but rather the start of a Trinitarian theodramatic performance rooted in the psalter. Jesus, the forsaken one, is rescued, and Jesus through the Spirit lauds God the Father in ever-expanding circles of praise.

*Note: all translations follow the Greek text of the Scripture as this reflects the usage of the earliest extant Christian authors.

Featured image credit: ‘it is finished’ by Leslie Richards, CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr

The post Good Friday: divine abandonment or Trinitarian performance? appeared first on OUPblog.

The origins of Easter

In order to celebrate Good Friday, we are exploring the fascinating origins of the Christian festival of Easter. The following is an extract from The History of Time: A Very Short Introduction by Leofranc Holford-Strevens.

Easter, commemorating the Resurrection of Jesus Christ, is historically the most important of all Christian festivals, even though in some Western countries it has largely lost the religious significance it retains amongst the Orthodox; nevertheless it merits discussion in a broader context not only because it is often a public as well as a religious holiday, or indeed because even Christians may be baffled by its apparently capricious incidence, but because the history of its calculation illustrates many complexities of time-reckoning.

The origin of Easter is the Jewish Passover, known in Hebrew as pesaḥ but in Aramaic, the normal spoken language of Jews in Roman Palestine, as pasḥā, which in Greek became páscha. (From this comes our adjective ‘Paschal’; the name ‘Easter’ is transferred from a Germanic festival.) Passover, in biblical times, was the slaughter of the Paschal lamb on 14 Nisan; it was eaten at nightfall, the beginning of the 15th by Jewish reckoning, and therefore of the seven-day Feast of Unleavened Bread.

According to St John’s Gospel, the Crucifixion took place in the daytime of 14 Nisan; this date seems more plausible than the 15th offered by the other three gospels, since that day would have been profaned by the proceedings. It was therefore natural for early Christians, many of them still Jews, to commemorate the Crucifixion on 14 Nisan, making Jesus the Lamb of God sacrificed to redeem humanity; the association was all the easier because in Greek páscha suggested the verbpáschein, ‘to suffer’. Even after Christianity had become a largely Gentile religion, the practice continued in Asia Minor, where the authority of St John was claimed for it, long after most other Christians had abandoned it. Such persistence was eventually classed as a heresy, known as Quartodecimanism.

However, since Jesus had risen on Sunday, that day was observed as a weekly feast day; in time it became normal, rather than to keep the anniversary of the Crucifixion, to celebrate that of the Resurrection, in the eastern provinces on the Sunday after Passover, elsewhere on the Sunday after a date found by independent calculation, both to avoid dependence on the Jews and because the increasingly widespread custom of fasting before it required knowing the date in advance. This entailed finding the 14th day of the first lunar month, called simply tessareskaidekátē, ‘fourteenth’, in Greek, but in Latin luna quartadecima, literally the ‘fourteenth moon’, abbreviated below as luna XIV. Once luna XIV had been found, the next Sunday had to be identified. The method of making these calculations is known as computus.

‘Rafael’, from the Sao Paulo Museum of Art. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

‘Rafael’, from the Sao Paulo Museum of Art. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

From the 3rd century onwards, most churches agreed that Easter should be the Sunday after luna XIV; but that was only the beginning. Two questions of principle remained: when the first lunar month began, and whether, should luna XIV be a Sunday, to observe Easter on that day or the following Sunday in order to keep apart from the Jews, who had not yet adopted a rule by which 14 Nisan could never be a Sunday. The latter became the more widespread practice; at Rome the conception of 14 Nisan as the first Good Friday caused Easter to be postponed even when luna XIV fell on Saturday, so that the feast was never earlier than the 16th lune or day of the lunar month (luna XVI), on which the Resurrection had taken place, and might be as late as the 22nd (luna XXII).

On the other hand, it was essential that it should not fall after 21 April, the day of the Parilia, celebrating Romulus’ foundation of the City, lest Christians, forced to fast on a civic feast, should be subject to hostility or temptation. Both the lunar limit of the 16th to 22nd lunes, and the lower solar limit of 21 April, are found in a calendar with base-year 222 inscribed in Greek on a stone chair now standing at the foot of the stairs in the Vatican Library.

In this calendar Easter may fall as early as 18 March; but Christians began to complain that Jews were no longer following their own rule that Passover should not precede the vernal equinox. This allegation was due partly to a misunderstanding of the Jewish rules, but partly to demonstrable variety in practice between one Jewish community and another. But if the Jewish Pascha ought not to precede the vernal equinox, it followed that the Christian Pascha ought not to do so either; by the 4th century the Church at Rome, where the date of the equinox was still taken to be 25 March, seems to have taken that view, though it could not be sustained in practice. At Alexandria the more rigorous principle was adopted that luna XIV itself, the proper date of Passover, must not precede the equinox, which was (more accurately) equated with 25 Phamenoth = 21 March; on the other hand, there was no lower limit, since 21 April (locally 26 Pharmouthi) was of no significance.

Featured image credit: Gordale Beck, by David Benbennick, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post The origins of Easter appeared first on OUPblog.

April 2, 2015

Ideas with Consequences – Episode 21 – The Oxford Comment

How did the Federalist Society manage to revolutionize jurisprudence for the most important issues of our time? The conservative legal establishment may claim 40,000 members, including four Supreme Court Justices, dozens of federal judges, and every Republican attorney general, but its strength extends beyond its numbers. From gun control to corporate political speech, the powerful organization has exerted its influence by legitimizing novel interpretations of the constitution and acting as a credentialing institution for conservative lawyers and judges.

In this month’s episode, we sat down with Amanda Hollis-Brusky, author of Ideas with Consequences: The Federalist Society and the Conservative Counterrevolution, to discuss the organization at a time when its power has broader implications than ever.

Image Credit: “Supreme Court” by WEBN-TV. CC by ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Ideas with Consequences – Episode 21 – The Oxford Comment appeared first on OUPblog.

When is it Fiddle time?

How do you create a repertoire for all levels of learning in music education? Kathy and David Blackwell’s repertoire for beginner to intermediate string players covers a huge range of styles whilst introducing new technical points in a step by step way. Their Fiddle Time, Viola Time, and Cello Time series offer attractive tunes that are fun to learn and provide quality teaching material. Find out how and why they wrote their very first tunes for young string players:

Headline image credit: Violin. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post When is it Fiddle time? appeared first on OUPblog.

Love and sex: perspectives from emerging adults

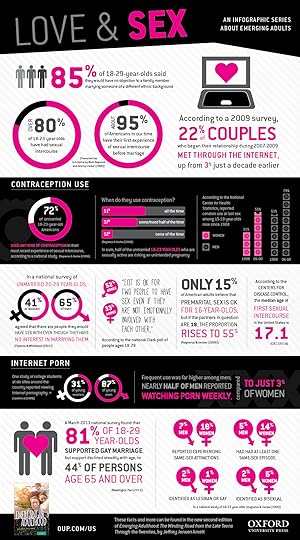

Attitudes towards love, sex, sexuality, and gender have changed rapidly over the last decade. What role do emerging adults play in this phenomenon? Are they really more open-minded than the previous generations — or more at risk?

Whether it’s Internet dating, dating across cultures, or same-sex marriage, people in this new life stage are marked by a greater openness to sex and sexuality. However, while many emerging adults are sexually active, they are often not taking precautions and risk not only pregnancy, but sexually transmitted infections. Moreover, many in this life stage don’t select their sexual partners based on seeking future marriage partners, and sexual intercourse no longer requires emotional involvement with the other party. With data from the new edition of Jeffrey Jensen Arnett’s Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens Through the Twenties, we present this infographic on emerging adults’ attitudes towards love and sex.

Download the pdf or jpg of the infographic.

Headline image credit: Group of young men and women enjoying at nightclub. © GlobalStock via iStock.

The post Love and sex: perspectives from emerging adults appeared first on OUPblog.

An Orthodox Passover

I remember the Passover Seder as a very special time. My brothers and I got new clothes that we had to save specially until that evening; this heightened our sense of anticipation and symbolized the special nature of this holiday.

I can still envision preparing for Passover in the Orthodox home of my childhood: I remember the frenzied work of emptying out all our cabinets, packing up the food we ate for the other 357 days of the year and lining all the cabinets, the stove, and the refrigerator with extra thick aluminum foil. In keeping with the commandments of the holiday, Orthodox families had two separate sets of dishes, (meat and dairy), silverware and table linens that they took out for just these eight days. The stress of the religious imperative to clean and rid the house of temporarily taboo foods heightened in the last week before the holiday. Until, the evening before the holiday began with the Seder, the Father of the family, with the children in tow, went through each room with a single feather, dusting surfaces to ensure no crumbs of forbidden foodstuff remained. The period of intense cleaning had ensured that. We all breathed a sigh of relief: now, we can get into the delights of the holiday.

The festival of Passover has its roots in the Hebrew Scriptures: the ancient Israelites were commanded to avoid all leavened foods—hametz—for the eight days of this holiday. Members of the various groupings Orthodox Jews begin preparing their homes one month in advance, right after the holiday of Purim, a festival celebrated annually to commemorate the salvation of the Jewish people in ancient Persia from Haman’s plot “to destroy, kill and annihilate all the Jews, young and old, infants and women, in a single day.” Not only are Orthodox Jews forbidden to eat hametz, they must work to ensure they do not have even the minutest speck of it in their homes.

“Passover @ Marilyn’s 2008″ by Joshua Bousel. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

“Passover @ Marilyn’s 2008″ by Joshua Bousel. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.The central ritual of the holiday is the Seder, which is the Hebrew word for order. The Seder is an annual holiday reconstructing the experiences of the ancient Israelites from their enslavement in Egypt. All participants, men, women and children, are commanded to not only remember the Exodus, but to feel as if they themselves, in their own lives, had actually been freed of slavery. The metaphor suggests a newfound sense of freedom, as if we all had moved out of the narrow constraints of oppression and into of the self-determination of free people. The entire evening is laid out with 15 specific elements that are to be highlighted, performed, eaten, or spoken in a carefully choreographed order. For example, the Seder begins with a recitation of these elements, which include two separate rituals of hand-washing, (one with and one without a blessing), a blessing over wine, a Seder plate with items commemorating the ancient Temple in Jerusalem, and most centrally, the vivid and detailed telling, retelling and elaborating upon the story of the Israelite’s exodus from Egypt. As an Orthodox family, we strove to do everything commanded in the Bible as well as the additional details added by the ancient rabbis, over the millennia in an effort to explicate and elaborate precisely how to observe this holiday.

As I learned Hebrew, beginning at age 5, I began to understand the language of the prayers, Biblical passages, rabbinic writings, and the recitation of the Exodus that comprise the Seder service. As my facility with the language grew, I came to see that some of the scriptural passages describing the Exodus were actually interpreted differently by the very ancient rabbis who were quoted in the Haggada. Their quotations revealed numerous different ways scripture could be interpreted. Here is my favorite illustrative passage.

In telling the story of the exodus from Egypt, the Haggada quotes from Deuteronomy 7: 18-19, a passage depicting the strength and power with which God intervened in history to save the Jews from slavery:

“_MG_0425″ by Eliya. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.

“_MG_0425″ by Eliya. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.“The Lord took us out of Egypt with a strong hand and an outstretched arm, and with a great manifestation, and with signs and wonders.”

The rabbis quoted in the Passover service all strove to understand the meaning of this Biblical passage, by parsing its language:

“And with an outstretched arm,” this refers to the sword, as it is said: “His sword was drawn, in his hand, stretched out over Jerusalem.”

Another explanation: “Strong hand” indicates two [plagues]; “Outstretched arm,” another two; “Great manifestation,” another two; “Signs,” another two; and “Wonders,” another two.

Now, how often were they smitten by “the finger”? Ten plagues! Thus you must conclude that in Egypt they were smitten by ten plagues, at the sea they were smitten by fifty plagues!

Rabbi Eliezer said: How do we know that each individual plague which the Holy One, blessed be He, brought upon the Egyptians in Egypt consisted of four plagues?

Rabbi Akiva said: How do we know that each individual plague which the Holy One, blessed be He, brought upon the Egyptians in Egypt consisted of five plagues?

Although I had been brought up to understand Orthodoxy as an absolute and complete way of life commanded by God whose observance I had to follow, the stark realization that the rabbis disagreed with each other undermined the religious absolutism that shaped my socialization as a young Orthodox girl. The Passover Haggada, the compilation of rules and recitations of Biblical and Rabbinic texts that form the foundation of the Seder, revealed that the great Rabbis who compiled this text actually differed in their interpretations of the meaning of this Scriptural passage. Their disagreements ironically undermined the religious absolutism with which I was raised and led to my asking fundamental questions: Who was to say that the Orthodox way of life was the only true way? How could my religious community be so certain its way of life represented the most true and accurate way of understanding and following the commandments of the ancient texts? By revealing the variety of interpretations one could make of God’s given laws, this religious holiday brought me a glimpse of relativism.

With that thought, the literal and metaphoric sacred canopy under which I lived within my family’s Orthodox community, showed its first tear.

The post An Orthodox Passover appeared first on OUPblog.

April 1, 2015

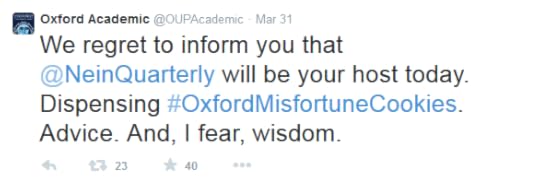

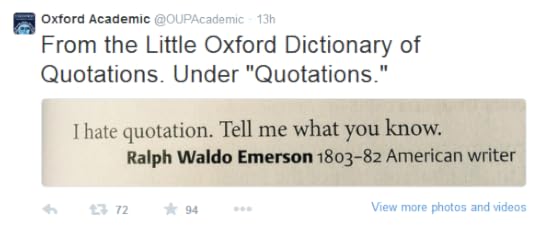

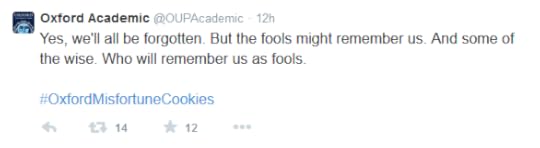

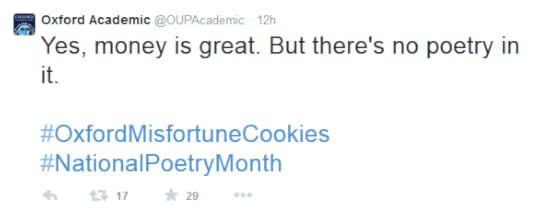

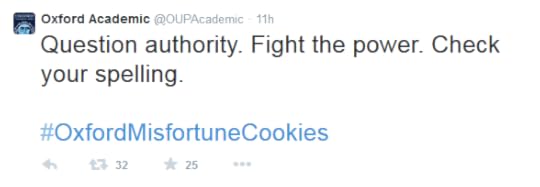

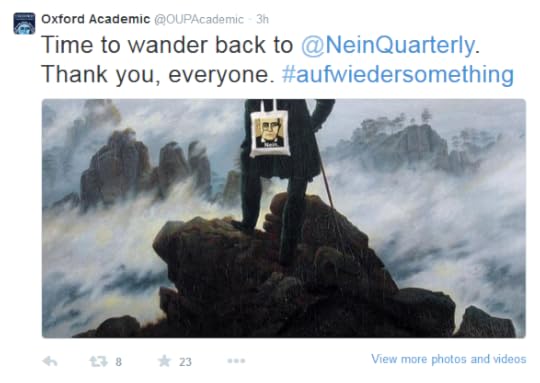

April Fool’s Day with Nein Quarterly

Yesterday, we invited Eric Jarosinski, aka Nein Quarterly, to guest tweet on the Oxford Academic Twitter account. Instead of our usual academic news and insights, followers were treated to #OxfordMisfortuneCookies and other wisdom. As a former professor, Eric is all too familiar with the many absurdities of academia, which he addresses with his trademark voice of “utopian negation”. Here’s a brief compilation of his tweets.

The post April Fool’s Day with Nein Quarterly appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers