Oxford University Press's Blog, page 677

April 15, 2015

Who was Leonardo da Vinci? [quiz]

On 15 April, nations around the globe will be celebrating World Art Day, and also Leonardo da Vinci’s birthday. A creative mastermind and one of the top pioneers of the Italian Renaissance period, his artistic visions fused science and nature producing most notably the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper. He was a painter, sculptor, inventor, and architect who produced several pieces and drafts, many of which went unfinished. Test your knowledge on Leonardo da Vinci to see how much you know about one of history’s greatest artists.

Featured Image: Design for a Flying Machine. Photograph by Luc Viatour / www.Lucnix.be. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Who was Leonardo da Vinci? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Greece vs. the Eurozone

The new Greek government that took office in January 2015 made a commitment during the election campaign that Greece would stay in the Eurozone. At the same time, it also declared that Greece’s relations with its European partners would be put on a new footing. This did not materialize. The Greek government accepted the continuation of the existing agreement with its lenders, the International Monetary Fund, the European Commission, and the European Central Bank. This was the only way of ensuring Greece would not run out of funding.

Throughout the negotiations, the crisis in Greece received intense media attention. Again, the very future of the Eurozone became a subject of much discussion on the international stage. Following days of uncertainty, public opinion in Greece appeared to have endorsed the softening of the government’s position vis-à-vis its lenders. But doubts about the future remain. The most pressing problem to be tackled by the government is covering its funding needs over the next few months. Greece will have to make a tremendous effort to meet the terms of the agreement. Within the Eurozone, there is a growing feeling that Greece is particularly problematic. The perception that the ‘Greek question’ has not yet been settled and that new difficulties will arise in the future still persists.

This most recent phase in the Greek crisis allows us to draw some general conclusions about the future of the Eurozone. The Eurozone is a project that goes well beyond the joint endeavors of its member states to implement a common monetary policy. The Eurozone has evolved into a very close form of cooperation, a joint system of addressing economic problems and building tools for its economic governance. In this context, wider political considerations cannot be disassociated from the economics of running Europe’s single currency. The recently enacted Banking Union is further evidence of the Eurozone’s continually expanding remit. In this new, more intensive form of cooperation, member states have far less room to act independently. Greece’s desire to be a part of the club without fully committing to its rules is increasingly out of touch with reality. All member states that are committed to this joint endeavor cannot neglect their responsibilities or pursue their own ‘independent’ agendas.

Despite its recent reforms and expanded remit, the Eurozone remains an unsatisfactory system of governance. While the Eurozone is now better prepared to deal with future financial crises, its ability to address their deep-rooted causes effectively is still limited. The pace of economic growth in Europe is sluggish, and—despite contrary proclamations—the problem has not yet been dealt with effectively. The initial reaction to the Greek debt crisis in 2010 failed to adequately assess the country’s economic problems, making a bad situation worse. The inability of the Eurozone’s political institutions to articulate a coherent response to the crisis put the spotlight on the European Central Bank (ECB) as a key player in overcoming the deadlock. In January 2015, the ECB launched a massive program of quantitative easing in order to boost economic growth. The ECB, however, is not a democratically accountable institution and its activities are not the subject of parliamentary scrutiny. In this sense, the ECB should not be permitted to assume the duties of a government.

Exit from the Eurozone, it seems, is not a feasible option.

During Syriza’s confrontation with the Eurozone, many predicted a ‘Grexit,’ or a Greek withdrawal from the Eurozone. Ultimately, Greece’s lenders did not push for it although there was incomprehension of the Greek stance. Hardliners back in Greece who had previously claimed that the Russians, the Chinese, or even the United States would come to Greece’s rescue also hesitated to press the ‘Grexit’ nuclear button. Exit from the Eurozone, it seems, is not a feasible option. Any country that attempts it will risk financial ruin. For the Eurozone itself, the financial cost of a potential exit may be manageable but the reputational damage to the project is too high to bear.

Despite the widespread belief that the Greek crisis highlighted the need for greater economic and political integration in Europe, recent developments in Athens point to the reverse. The Eurozone’s problems persist not because member states act too fast, but because they procrastinate. These problems will only multiply if each country continues to follow its own fiscal policy or implement Treaty provisions at its own discretion. A fiscal union encompassing a common budget and a common European tax regime, redistributive policies to mediate inequalities in the productive base of different countries, and the pooling of European debt in order to support the development of less successful economies, are both desirable and feasible. They must all be linked to the strengthening of the European Parliament or the creation of a Eurozone Parliament so that the leadership of the Union can be held accountable.

These developments will ensure that no member state—Greece, in particular—will be able to pursue its economic future outside the context of the Eurozone. It is only through cooperation with other member states that a country can improve its negotiating position and change the balance of power within the Eurozone. Greece’s own desire to remain in the ‘core’ of the European Union is inextricably linked to overcoming its own backwardness, pursuit of continuous reform in the public administration so that it is more cost-effective and productive, changes in its economy in order to enhance the productive and technological potential of the country, persistent efforts to defeat clientelistic networks and free-riding attitudes, as well as a new thinking on how to promote social justice and cohesion. Greece must also adopt a European policy that breaks away from its ‘traditional’ attitude of seeking exemptions and defending the self-defeating notion of its own exceptionalism. It is in every country’s interest not to be seen as a perpetual exception—a ‘problem’ that never goes away.

Image Credit: “Not not not” by Pinelopi Thomaidi. CC BY NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Greece vs. the Eurozone appeared first on OUPblog.

Capital flight from Africa and financing for development in the post-2015 era

The more money you make, the more you lose. That is the story of Africa over the past two decades. Indeed, along with the impressive record of economic growth acceleration spurred by booming primary commodity exports, Africa continent has experienced a parallel explosion of capital flight. From 2000 to 2010, the African continent lost $510.9 billion through capital flight, or $46.4 billion per year. This is nearly equal to the cumulative amount over 1980-1999 (a total of $537.6 billion, or $26.8 billion per year). In other words, Africa is losing capital twice as fast as in the past, even as its growth has accelerated over the past decade. The explosion of capital flight in a period of accelerating economic growth and improved macroeconomic environment is at odd with conventional economic theory, which would suggest that an improvement in economic performance would attract foreign capital seeking to take advantage of ensuing higher returns on capital.

Fifteen years ago, the United Nations set 2015 as the target for developing countries to reduce poverty by half. The date has come, but most African countries are far from reaching this goal. While many countries in the continent have experienced some reduction in poverty headcount, a large number of people in the continent continue to live in dire conditions where they lack of access to basic social and human services. In fact, the World Bank’s data shows that sub-Saharan Africa is the only place where the number of poor people has increased consistently over the past two decades – from 210 million in 1981 to 415 million in 2011. Will the situation be better in fifteen years? No one knows for sure. What would it take for Africa to improve its odds of conquering poverty faster over the next decade? For most African countries this will require growing faster, and for all African countries this will require an improvement in the distribution of the gains from growth; that is, a substantial reduction in inequality. Achieving these goals will, however, necessitate substantially higher financing for development.

Where will the additional financing come from? The focus today is on improving domestic resource mobilization and attracting more foreign capital. Indeed, improvements in governance, reforms in the tax system, and innovations in the financial sector hold real potential for increasing tax revenue and private savings above the current levels. Efforts along those fronts will not only generate much needed fiscal space, but also buy more policy independence.

Returning home. Photo by martapiqs. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via poma Flickr

Returning home. Photo by martapiqs. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via poma FlickrThere is another important source of additional financing that has thus far been untapped. It is the large amounts of resources that can be saved from curbing capital flight and additional capital that can be mobilized through stolen asset recovery. In order to design effective policies and strategies to combat capital flight and entice repatriation of private capital held abroad, it is essential to understand the drivers of capital flight in the first place. Capital flight from Africa is driven by factors pertaining to domestic conditions as well as external factors related to the global financial system. Thus, in its quest to fight capital flight to improve its capacity to finance its development agenda in the post-2015 era, Africa needs to tackle these domestic and external drivers of capital flight. While addressing domestic, economic, and institutional problems that induce capital flight is challenging, tackling the external pull factors of capital flight will be particularly daunting.

A key external driver of capital flight is the proliferation of offshore finance and the facilities offered by tax havens that enable the smuggling of legally and illegally acquired capital from Africa, and the concealment of private wealth outside of sight of national regulatory authorities. This expansion of offshore finance is partly a byproduct of the triumph of free market ideology that drove deregulation of finance in advanced economies in the “new golden age”. Moreover, the high volumes of profits generated in safe havens make them politically powerful, enabling them to directly and indirectly undermine policies aimed at cleaning up the global financial system. Clearly, the fight for transparency in the global economic and financial system will be challenging. There is no option other than to forge ahead in this indispensable fight.

On the African side, there is a need for collective efforts to increase awareness on the problem of capital flight and its high opportunity costs in terms of forgone development opportunities. It is encouraging that important initiatives are already underway on the continent for this purpose. On the policy dialogue front, a major development was the establishment of the High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa which is providing a framework to engage policy makers in the search for practical strategies to stem capital flight. On the knowledge generation front, research institutions and networks (such as the African Economic Research Consortium) are engaged in gathering country-specific information on the scope, nature, and mechanisms of capital flight to inform policy design. It is critically important for African governments to take initiatives to leverage the growing volume of knowledge in this area, and integrate combatting capital flight into their national development agenda.

On the international front, the ongoing high-level debates on the post-2015 sustainable development agenda offer an opportunity for a global compact towards financial transparency and responsible management of international borrowing and lending as part of the overall strategy for scaling up financing for development. As the potential for increasing conventional official development assistance is limited, it is urgent to harness new and innovative sources of financing in order to expand the resource envelope. One such source is stemming capital flight and recovering stolen assets from past capital flight. This is a win-win solution for Africa and its development partners: the continent will get more non-debt generating resources in its purse, while donors will buy more development for their buck without adding more pressure on their budgets.

Featured image: World Grunge Map – Sepia. Image by Nicolas Raymond, www.freestock.ca. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr

The post Capital flight from Africa and financing for development in the post-2015 era appeared first on OUPblog.

April 14, 2015

Boko Haram and religious exclusivism

How do violent Muslim groups justify, at least to themselves, their violence against fellow Muslims? One answer comes from Nigeria’s Boko Haram, which targets the state as well as both Muslim and Christian civilians. Boko Haram is infamous for holding two ideological stances: rejection of secular government and opposition to Western-style education. “Boko Haram,” a nickname given by outsiders, means “Western education is forbidden by Islam.” Underlying the rejection of both democracy and Western schooling, however, is another concept: al-walā’ wa-l-barā’, which for Boko Haram means exclusive loyalty (al-walā’) to “true” Muslims and disavowal (al-barā’) of anyone the group considers an infidel.

Al-walā’ wa-l-barā’ derives from various passages in the Qur’an, which sometimes uses words deriving from the same tri-consonantal roots, such as walī, or protector. There are many ways to interpret such passages. Boko Haram, as discussed below, has chosen a particularly harsh and exclusivist reading. Al-walā’ wa-l-barā’ was a key element of Boko Haram’s early teachings, and the group continues to reference the concept in its propaganda. Boko Haram’s brutality toward civilians cannot be understood without taking into account its exclusivist stance.

Al-walā’ wa-l-barā’ has been a theme for other jihadis as well. As Joas Wagemakers has explained, the concept has been transformed in recent decades. Jihadi thinkers like Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi (b. 1959) developed al-walā’ wa-l-barā’ from a theological doctrine into a political ideology. This ideology is used in an effort to justify violence against those whom jihadis regard as false Muslims – including Muslim political leaders, rival Muslim scholars, and Muslim civilians. The ideology also valorizes the notion of small, committed bands of “true” Muslims living apart from and in resistance to a larger, fallen society.

Boko Haram was founded around 2002 in the northeastern city of Maiduguri by Muhammad Yusuf (1970-2009), a self-made preacher. For much of the period 2002-2009, Yusuf was able to preach openly. When his ideas met disapproval from prominent Muslim scholars in Nigeria, Yusuf supplemented his lectures with a manifesto, entitled Hādhihi ‘Aqīdatunā wa-Manhaj Da‘watinā (This Is Our Creed and the Method of Our Preaching). The book outlines his positions on various issues, including Western education. One theme was Yusuf’s interpretation of al-walā’ wa-l-barā’.

Boko Haram Logo Image Credit: “Logo of Boko Haram” by ArnoldPlaton. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Boko Haram Logo Image Credit: “Logo of Boko Haram” by ArnoldPlaton. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia CommonsIn the conclusion, Yusuf discusses al-walā’ wa-l-barā’ as a framework for understanding Islam as a completely self-sufficient system, and therefore for rejecting any other system:

Al-walā’ wa-l-barā’ is one of the pillars of belief in the unity of God (al-tawḥīd) and of the creed (al-‘aqīda). And it is in implementing al-walā’ wa-l-barā’ that the Muslim joins the party of God (ḥizb Allāh), those whom God has promised victory and prosperity (p. 159).

Yusuf quotes two Qur’anic verses (5:55-56) that use words derived from the same tri-consonantal root as al-walā’. These verses suggest that God and His Messenger alone are the protectors of the believers. Yusuf offers another verse (58:22) to support the remaining part of the formula, al-barā’ or disavowal of non-believers. He comments:

In this holy verse the Most High shows that those who believe in God and the last day do not make friends with the infidels who oppose God and His Messenger, even if these infidels are their parents, their children, or their tribe. Rather, the believers disavow them completely…. We believe that al-walā’ wa-l-barā’ is one of the foundations of Islam, and a prominent sign of faithfulness (pp. 160-161).

For Yusuf and the early Boko Haram, rejecting secularism and Western-style education was not just a political choice or a religious decision made on a case-by-case basis; this rejection was part of a larger conception of what it meant to be Muslim. Yusuf arrogated to himself and his followers the right to decide who was and was not a genuine Muslim.

Like many other jihadi groups around the world, Boko Haram claimed the right to pronounce other Muslims to be unbelievers, a process known as takfīr. Al-walā’ wa-l-barā’ is not just a synonym for takfīr however. Takfīr is the endpoint, but for Boko Haram, al-walā’ wa-l-barā’ is the framework for evaluating people, communities, and systems according to what the movement perceives as scriptural dictates. Al-walā’ wa-l-barā’ is not just a formula for anathematizing other Muslims but also for cultivating intense in-group loyalty.

Yusuf was killed in police custody in the aftermath of Boko Haram’s mass uprising in 2009. Since his death, Boko Haram has not engaged in much scholarship, but has explained its worldview largely through propaganda. Operating in the latter genre, Boko Haram’s current leader Abubakar Shekau (b. ca. 1968-1975), a companion of Yusuf, has not systematically elaborated his understanding of al-walā’ wa-l-barā’. Yet Shekau does invoke the concept in ways that audiences attuned to jihadi discourses would recognize.

In his February 2015 video “Message to the Leaders of the Disbelievers,” Shekau rebukes Niger’s President Mahamadou Issoufou and Chad’s President Idriss Deby, both Muslim, for their participation in Nigeria’s fight against Boko Haram. Shekau questions both presidents’ religious credentials, denouncing their alliances with French President Francois Hollande, a non-Muslim. Shekau quotes the Qur’anic verse 5:51, “O you who believe, do not take the Jews and Christians as allies.” The word “allies” here is awliyā’, from the same root as al-walā’. Later in the video, Shekau turns to the Nigerian elections, at that time still weeks away. Shekau makes the connection between practice and identity explicit: “The people of democracy are unbelievers (arna, a Hausa word meaning ‘pagans’).” He then addresses the audience:

These words are not a fight I’m picking with you, but a call I make to you…. The one who comes and repents and returns to Allah, and supports the Qur’an and the Sunnah (model) of the Prophet, he is our brother! The one who goes and supports Francois Hollande, and Obama… [and] he supports Israel and he supports the infidels of the world, he is our enemy.

The logic of al-walā’ wa-l-barā’ remains at work here. Shekau anathematizes any Muslim who takes non-Muslims for allies. He disavows them (al-barā’) precisely because in his eyes they have not practiced the proper loyalty (al-walā’) to other Muslims. But he also holds out the possibility of inclusion for those who join Boko Haram.

Boko Haram’s understanding of intra-Muslim solidarity has underlain its ferocious violence. Boko Haram considers anyone outside the group to be a legitimate target, because the only illegitimate targets are those whom it defines as Muslim – in other words, only those who belong to the group or share its beliefs. When Boko Haram kidnaps Muslim schoolchildren, summarily executes Muslims who refuse to join the group, attempts to assassinate hereditary Muslim rulers, and targets popular Muslim politicians, it is implementing its understanding of al-walā’ wa-l-barā’.

Image credit: “Islam” by Firas. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Boko Haram and religious exclusivism appeared first on OUPblog.

The top sci five classical receptions on screen

Recently, a number of prominent publications have featured a growing body of work on classical receptions in science fiction and fantasy, including Mélanie Bost-Fiévet’s and Sandra Provini’s collection L’Antiquité dans l’imaginaire contemporain (Garniers Classiques 2014), a special issue of the journal Foundation on “Fantastika and the Greek and Roman Worlds” (Autumn 2014), and our own collection, Classical Traditions in Science Fiction (OUP 2015).

This focus on science fiction, now an important part of popular culture, reveals much about how ancient classics are being received by modern audiences, particularly when it comes to the silver screen. For example, contributors to our collection wrote on topics including inorganic beings and tropes of disability in Blade Runner and ancient literature; how Forbidden Planet evokes mid-20th-century Aristotelian visions of tragedy; and modern Hollywood visions of imperial Rome in The Hunger Games trilogy. Still other examples were discussed at the recent “Once and Future Antiquity” international conference.

However, this burgeoning field is wide open for exploration not only by professional classicists, film theorists, and other scholars, but also by fans of all of these genres. In order to invite readers to join the ongoing conversation, we note the Top Sci Five Classical Receptions on Screen that we would love to see examined at greater length and depth.

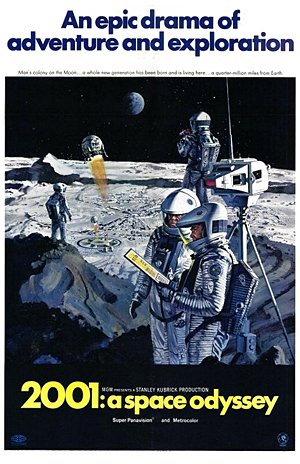

“Poster for 2001: A Space Odyssey” by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Fair Use via Wikimedia Commons.

2001: A Space Odyssey

“Poster for 2001: A Space Odyssey” by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Fair Use via Wikimedia Commons.

2001: A Space Odyssey

Stanley Kubrick’s seminal film, developed in close collaboration with Arthur C. Clarke, is a bald-faced classical reception. Kubrick deliberately chose the subtitle to suggest that this–a long and fantastic journey through the mystery and remoteness of space–is perhaps the modern Odyssey. Yet unlike some other notable examples of ‘incredible voyages,’ 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick 1968) is neither parodic nor vaguely monomythic, devoting as much attention to the disconcerting metaphysical implications of homecoming as to its spectacularly realistic depictions of travel through space.

As outer space and inner spaces overlap, ‘What is out there?’ becomes a way of exploring ‘What is in here?’ and ‘Who are we / am I?’ in ways readers of Homer and Virgil are apt to recognize. Although such questions can be attributed to the film’s modern sources of inspiration—above all Clarke’s own “The Sentinel” (1951) and Childhood’s End (1953)—they also resonate deeply with ancient themes, including Odysseus’s various self-descriptions when confronted with versions of his past and Aeneas’ question of what it means to pursue a new home by divine command.

Deleted scene: As if in unconscious evocation of classical antiquity, the film’s most iconic character, the artificial intelligence and archvillain HAL 9000, was originally going to be named Athena.

StargateAlthough not strictly ‘classical’ in its involvement with Greece or Rome, Stargate (Emmerich 1994) is enthusiastic about ancient studies insofar as ancient Egyptian culture is, in the film’s central conceit, the result of an intervention by a technologically advanced visitor from another world. The film thus presents a variation of gods as extraterrestrials, a theme related to both the ancient theory of Euhemerism (stating that gods are post-humans) and the modern ‘Chariots of the Gods’ theory (after Erich von Daniken’s 1968 book.) Moreover, it envisions a universe in which the study of ancient language and culture is, paradoxically, a guide to humankind’s possible future.

Of course, the film operates under somewhat unexamined assumptions about American exceptionalism, as Egyptologist Daniel Jackson (James Spader) certainly conforms to assorted stereotypes of his academic field: e.g., he is white, male, heterosexual, bespectacled, physically unprepossessing, and allergic to seemingly everything. But Jackson nonetheless also embodies a kind of triumph of the intellectual over the merely physical, leading not only to military victory against the cruel alien masquerading as Ra, but also to cross-cultural understandings.

Bonus feature: The film inspired several television series of the same name, one of which centers on the lost city of Atlantis, reimagined as an ancient city-sized spaceship.

AlienPrometheus (Scott 1979 & 2012). Ridley Scott’s two films in the Aliens series reveal a sustained interest in icons from classical myth that explore and articulate human suffering. In Alien, the human crew of the spaceship Nostromo encounter the deadly xenomorphs on a planetoid identified as Acheron LV-426, a name that not only alludes to one of the rivers of the Underworld but anticipates the living hell the humans will experience. This makes Ellen Ripley, the film’s lone survivor, into a kind of science-fictional Greek hero who returns from the realm of the dead but now questions the very meaning and limits of humanity. Alien also complicates notions of humanity through the android Ash, who betrays the human crew in favor of his creators, the Weyland-Yutani Corporation, hardening distinctions between the human and inhuman. Scott later complicates such thinking in Prometheus, wherein the android David, once liberated from his human master Weyland, proves more sympathetic—and even more humane—than human characters themselves.

Prometheus engages more obviously with the classics than Alien, evoking the ancient myth of Prometheus and his gift of fire to humankind in order to explore the unintended consequences of technoscientific discovery and reimagine the confrontation between humankind and its own creator. While Prometheus, at its outset, shares Stargate’s perspective that the study of ancient languages and cultures–in this case, archaeology and the myth of Prometheus–serves as a guide to for the future, the crew of the ship Prometheus soon discover that they have instead opened Pandora’s jar, as it becomes clear that humankind’s creators, the Engineers, seek to obliterate them with biological weapons (stored in actual jars).

Language selection: Prometheus includes a version of Proto-Indo-European, which the android David studies, with on-screen assistance from real-life linguist Anil Biltoo, in order to speak with the Engineers; one Engineer returns the linguistic courtesy by decapitating David.

The Rocky Horror Picture ShowThis cult favorite, based on a 1973 stage musical, is a science fiction/horror film ending in the revelation that the main characters are aliens from the planet Transsexual in the galaxy of Transylvania. And yet, amidst its rampant, Dionysiac transgression of generic and sexual boundaries, Rocky Horror (Sharman 1975) shows a marked interest in classical hard bodies, not only through the repeated appearance of neo-classical statuary but also in its focus on the mythic figure of Atlas.

Rocky, the creation of scientist Dr. Frank N. Furter, evokes in his physical appearance not Frankenstein’s monster (as we might expect) but the exquisitely sculpted Charles Atlas, the mid-20th century guru of masculine fitness and self-transformation. However, Rocky discovers himself not to be a self-made man like Charles Atlas, but rather a prisoner in a state of perpetual bondage like the mythic Titan Atlas, known for his perpetual suffering in holding the heavens upon his shoulders and depicted in stained glass over Furter’s bed. Rocky Horror thus mobilizes an ancient icon to cast doubts upon the promised liberation of the self through modern sex and science, hinting at the complex horrors inherent in practices of classical reception.

Easter egg: When Dr. Furter captures several of the characters towards the end of the film, he transforms them into statues using a weapon called ‘the Medusa transducer,’ whose sing-song name of course recalls the petrifying Gorgon.

The Transformers: The MovieThe last item on our list is, in a way, also the first—the 1986 film that first crystallized our interest in classical receptions in science fiction. Like all Transformers properties, the film depicts an enduring war between forces of good and evil in the forms of Autobots and Decepticons. As fans will know, important Autobots have Latinate names; their leader is Optimus Prime, who is later replaced by Rodimus Prime. Important Decepticons, in contrast, have Hellenic names; their leader is Megatron, who is later upgraded into Galvatron. That contrast alone would have been sufficient fodder for the Wacky Classics Movie Night we held in our Greek and Latin House at Reed College in the fall of 1997: Are Latinates/Romans thus ‘good’ while Hellenics/Greeks are somehow ‘evil’?

But the film goes further in its tagline, ‘Beyond good, beyond evil, beyond your wildest imagination,’ to envision a universe inhabited by sentient machines taking a wide range of forms and occupying an equally wide range of moral positions. Five-faced judges with monstrous animal helpers recall the multiple judges of the ancient Underworld and the guard dog Cerberus, while scavengers who live on the scraps of earlier cultures emphasize practices of recomposition in post-classical periods. Above all, there is Unicron—also known as the Lord of Chaos, the Chaos Bringer, and the Planet Eater—whose destabilizing presence seems to evoke third-century BCE Hellenistic politics or, later on, the ‘barbarian invasions’ from the north.

Image Credit: “Planet Space Universe Blue Background Light” by spielecentercom0. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The top sci five classical receptions on screen appeared first on OUPblog.

“Under the influence of rock’n’roll”

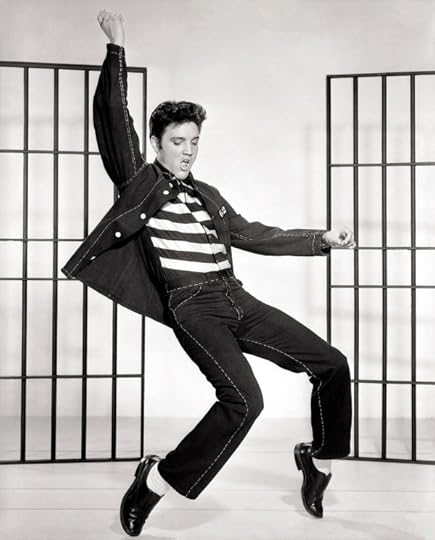

Rock’n’roll music has defied its critics. When it debuted in the 1950s, many adults ridiculed the phenomenon. Elvis, Chuck Berry, and their peers would soon be forgotten, another passing fancy in the cavalcade of youth-induced fads. The brash conceit, “rock’n’roll is here to stay,” however, proved astute.

Why were American adults and, for that matter, their Soviet counterparts frightened of rock’n’roll? Commentators ranted indignantly about the new music. Frank Sinatra complained that rock’n’roll featured: “cretinous goons” who used “almost imbecilic reiteration and sly, lewd, . . . dirty, lyrics” to become the “martial music of every side-burned delinquent on the face of the earth.” The New York Times quoted psychiatrist Francis Braceland, who called rock’n’roll, “a cannibalistic and tribalistic form of music.”

Rock’n’roll’s destructive and subversive force knew no bounds. A Florida minister claimed that “more than 98% of surveyed unwed mothers got into their predicament while under the influence of rock’n’roll.” New Jersey Senator, Robert Henrickson claimed, “Not even the Communist conspiracy could devise a more effective way to demoralize, confuse, and destroy the United States.”

Behind the Iron Curtain, Russian officials claimed that rock’n’roll was “an arsenal of subversive weapons aimed at undermining the commitment of young Russians to Communist ideology.” An East German observer believed rock’n’roll would “lead them [German youth] into a mass grave.” If these officials were correct, rock’n’roll was truly one of the most destructive forces in history.

Rock’n’roll inspired a conspiracy theory in a decade rife with conspiracies. How did rock displace established musical styles? Patti Page’s rendition of “How Much Is that Doggie (In the Window)” reached the top of Billboard’s chart, an indication of the popular pabulum pervading America during the early 1950s.

Elvis Presley, Jailhouse Rock. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Elvis Presley, Jailhouse Rock. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. How could rock’n’roll compete with “How Much Is that Doggie?” The answer, my friend, was flowing out of wallets. Independent record producers paid disc jockeys to play daring, new forms of music. Authorities claimed that rock’n’roll would have proved stillborn, had it not been for subversion by good, American dollars. The rock’n’roll cretins had usurped the air time of wholesome performers.

Songwriters paying performers to play their songs was a long-standing tradition. This practice, known as payola, was a way for newcomers to break into the music business. Many of the top music publishers had once engaged in payola.

When independent record label producers began paying disc jockeys to play songs by unknown performers, the practice raised the ire of public crusaders and legislators who viewed the practice as novel and sinister. The 1950s were a decade of America “losing its innocence.” Rock’n’roll joined quiz-show rigging, the U-2 (the spy plane, not Bono), and a host of other incidents of lost innocence; Americans must have been careless with their innocence back then.

Rhode Island Senator John Pastore discounted payola’s importance by comparing the practice to paying a headwaiter to get a better table. Other legislators, though, recognized a heaven-sent opportunity to garner publicity and to curry favor with the legions of decency: Commercial corruption and rock’n’roll have got to go. Arkansas representative Oren Harris claimed that payola, “constitute[s] unfair competition with honest businessmen who refuse to engage in them. They tend to drive out of business small firms who lack the means to survive this unfair competition.”

Ronald Coase, Nobel-Prize Winner in Economics, pointed out the fallacy of this argument. Banning payola benefited established music publishers and producers, who could afford lavish marketing and distribution campaigns. Payola was an effective way for independents to enter the market.

Coase argues out that disc jockeys could not indiscriminately play any song for payola. Disc jockeys had to weigh the cash inducement against the effects upon his program’s ratings. If the disc jockey played unpopular music, his cachet and his job might disappear. Disc jockeys, therefore, would only accept payola for unknown songs and performers with potential appeal.

The legislators also had difficulty finding a law that payola participants violated. It was not necessarily bribery because station owners often approved of payola, since it meant more people wanted to be disc jockeys, thereby lowering salaries. Legislators eventually enacted legislation making payola illegal.

Disc jockey Alan Freed was rock’n’roll’s first martyr. Freed’s popularity plunged after he admitted accepting cash.

By the 1980s, even Ronald and Nancy Reagan claimed to be fans of the Beach Boys, although Secretary of the Interior James Watt tried to ban the group from playing on the National Mall for a Fourth of July celebration. Watt believed the band’s fans indulged in drug use and alcoholism. Even the Soviet Union was now happy to invite the band to play in Leningrad (the imagery of Lenin bopping to the Beach Boys’ beat tickles the imagination).

The furor over payola is largely forgotten, but rock’s beat remains.

Heading image: Chuck Berry 1971 by Universal Attractions. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post “Under the influence of rock’n’roll” appeared first on OUPblog.

Iconic trumpet players who defined jazz history

Since emerging at the beginning of the 20th century, jazz music has been a staple in American culture. Historians are not clear on when exactly jazz was born or who first started playing it, but it can be agreed upon that New Orleans, Louisiana is the First City of Jazz. Amidst the inventive be-bop beats filling up NOLA bars are the iconic trumpet players who still continue to inspire musicians and new music every day.

Buddy Bolden – Bolden had a magnetic personality and a musical gift that combined ragtime and the blues. His career defined jazz and he was crowned the first jazz trumpeter. He was very popular in turn-of-the-century New Orleans and kept local crowds returning to his lively shows. Even though Bolden never recorded any of his music, he was an inspiration to all the jazz legends that came after him.

King (Joe) Oliver – Oliver was praised for being an excellent band leader, imposing discipline on his musicians while skillfully playing along with them. His music was expressive, theatrical, and known for its wa-wa effects. He later enlisted Louis Armstrong to play in his band and the group was a national sensation on the jazz scene. His career as a top band leader in New Orleans and Chicago dissipated in the 1930s, but his influence on Armstrong was the beginning of jazz history.

Louis Armstrong – Affectionately known as “Satchmo” and “Pops,” Armstrong is one of the most influential people in jazz and the Harlem Renaissance. His recognizable name and iconic sound reached audiences beyond jazz and established him as a monumental force in music. In his lifetime, Armstrong toured internationally, recorded almost 1500 tracks, and was the first jazz musician to appear on the cover of Time (1949).

Louis Armstrong, jazz trumpeter. 1953. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection.

Louis Armstrong, jazz trumpeter. 1953. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection. Dizzy (John Birks) Gillespie – As one of the pioneering innovators of jazz, Gillespie lead the way for bebop and set a new standard for jazz music. Growing up, Gillespie had little formal training. He practiced the trumpet incessantly and taught himself music theory. His exuberant personality and prankish ways earned him the nickname Dizzy. In his six-decade career, Gillespie played alongside the likes of Cab Calloway, Ella Fitzgerald, and Duke Ellington.

Lee Morgan – Deemed one of the greatest trumpet players of all time, Morgan was hailed for his individual style and rich tones. Morgan’s talent landed him a spot in Dizzy Gillespie’s orchestra soon after his high school graduation. He enhanced his popularity with his own recording, “The Sidewinder.” It was an instant hit that sparked a mini jazz-funk movement. Morgan’s vibrant career and life came to an end after a jealous female friend shot him in a nightclub.

Miles Davis – American jazz trumpeter and bandleader, Miles Davis led the cool jazz movement with his relaxed rhythms focused in the middle register. Described as a ‘living legend,’ he got his start at the ripe age of 13. Not one to stick to standards, Davis was the most consistently innovatory musician in jazz from the late 1940s until the mid-1970s. He bounced from bop to modal playing to jazz rock and built an impressive musical resume. His technical mastery and progressive approach remains a teaching tool for aspiring musicians to follow.

Chet Baker – Baker developed a distinct emotionally-detached sound while playing the trumpet in army bands. It’s estimated that he recorded over 900 songs in his lifetime. He was a hallmark of West Coast cool jazz and dominated the domestic and international jazz scenes. After battling drug addiction, two imprisonments and losing teeth, the post-war trumpeter regained his intellectually complicated sound and recorded some of his best work in his later years.

Art Farmer – Farmer was always in high-demand for his smooth interpretations of complex arrangements and his talent of sounding laid-back. With the rise of rock and political unrest, Farmer moved to Europe and established a music career in Austria. Before his death, Farmer invented the Flumpet, a fusion of the flugelhorn and the trumpet.

Donald Byrd – Trumpet legend Donald Byrd cultivated a vivacious career with his hard-bop beats and warm tone. He studied the trumpet and composition and played in bands while in the military. Playing into a post-jazz movement, Byrd turned towards R&B and funk music leaving his faithful fans disappointed. The commercial success of his pop-oriented albums overshadowed the trumpet but his musical legacy in jazz remained.

Wynton Marsalis – Hailed as an extraordinarily gifted trumpeter, Marsalis is also an exceptional educator and composer in jazz. He is the first musician to win Grammy Awards for a jazz recording, classical recording, and his recording of trumpet concertos by notable musicians. Marsalis tirelessly made it his mission to educate the masses and reel in a young audience to the world of jazz.

Headline image: Trumpet Macro by Jameziecakes. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Iconic trumpet players who defined jazz history appeared first on OUPblog.

April 13, 2015

Signs, strategies, and brand value

The semiotic paradigm in market research gives new meaning to the expression, “You are what you eat.” The semiotic value of goods, from foodstuffs to cars, transcends their functional attributes, such as nutrition or transportation, and delivers intangible benefits to consumers in the form of brand symbols, icons, and stories. For instance, Coke offers happiness, Apple delivers “cool,” and BMW strokes your ego.

Brand meaning is not just a value added to products but has direct impact on financial markets as well. Market experts find a direct relationship between semiotics, the science of signs, and economics since they evaluate brands on the basis of their semiotic reach, depth, and cultural relevance. In effect, brands structure an economy of symbolic exchange that gives value to the meanings consumers attach to the brand name, logo, and product category.

Marketing semiotics research enables management to leverage consumer investments in the cultural myths, social networks, and ineffable experiences they seek in brands by finding out what consumers yearn for, what new cultural trends they are following, and how they incorporate brands into their lifestyles and social media streams. Rooted in the theory and methods of Lévi-Strauss’s structural anthropology, semiotics-based market research accounts for the mutual influences of category codes, brand codes, and cultural norms on the perception of value in a given market. These codes and norms apply not only to the structure of advertising and popular culture, but also to the organization of retail space, the ritual behavior of consumers, the meaning of package design, and the structure of multimedia hypertexts.

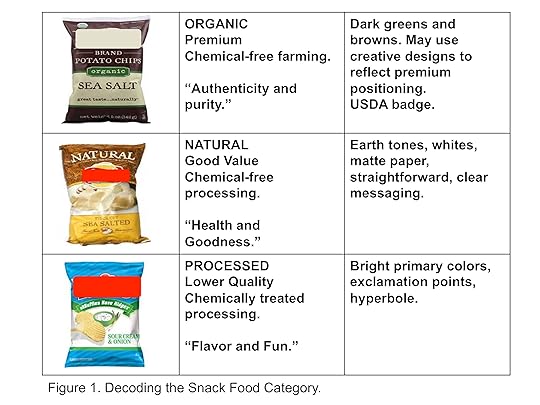

For example, package design conforms to general category codes that represent, in shorthand, the product’s value proposition in relation to other products. In the Food and Beverage category, for instance, contrasts between the perceived quality of Natural and Processed foods are inscribed on packaging in terms of binary oppositions related to colors, shapes, and even the rhetorical style of the message. As illustrated in Figure 1, Processed foods use chemical flavors and preservatives, featuring bold primary colors on their packaging. Natural foods, on the other hand, are chemical-free and feature muted earth tones.

Given the current demand for food health and wellness, consumers are willing to pay more for brands that are Natural. Thus, the Processed/Natural binary generates a paradigmatic system of binaries that structure the representation of value on the supermarket shelf. They include chemical free/chemicals, earth tones/primary colors, and lower quality/higher quality. These kinds of binaries have strategic implications for brands because they entail shifts in the perceived quality and value of the products they represent. The introduction of Organic products added another level of quality to the equation because Organic foods are chemical free at the food source. The Natural/Organic binary entails a paradigmatic series of its own, including contrasting signifiers and quality standards [See Figure 1.]  Created by Laura Oswald. Used with permission.

Created by Laura Oswald. Used with permission.

In the same way they acquire language, consumers acquire fluency with these codes through repeated encounters with packaging in the supermarket. They learn to associate the bright primary colors, flashy paper, and hyperbolic product claims with Processed products; they associate clean lines, whites, and earth tones with Natural products; and associate dark greens, browns, authenticity claims, and muted colors with Organic products. Each design scheme also references a different value proposition based on quality.

To develop a design scheme for a new product, management must adhere more or less to these codes or risk confusing consumers and losing brand equity. Marketing semiotics research defines these codes by tracing recurring themes and patterns in a generous sampling of ads and packaging for the category. Researchers submit findings to a binary analysis, which reveals the underlying paradigmatic structure of value for the category.

After decoding the product category, management must then decide on a creative strategy for the brand that both adheres to the general category codes and also differentiates the brand from competitors. For another business case, semiotic research in the disposable diaper category revealed an underlying paradigmatic system based upon the binary opposition of Dry Baby/Wet Baby. Dry babies are happy and reflect the Good Mother and the victory of Culture over Nature; wet babies are unhappy and reflect the Bad Mother and the victory of Nature over culture.

The Pampers brand claims the dominant share of the category by mastering the semiotics of the Good Mother in advertising and on packaging, including serene moms cuddling quiet babies in their arms, rendered in soft pastels. Competitors face the challenge of differentiating their brand from Pampers without falling into the negative territory of wet, unhappy babies and bad mothers.

Researchers mapped the Dry/Wet paradigm on Greimas’ double-vector Semiotic Square, which deconstructs the strict binary logic of the Dry/Wet binary into a series of negations, such as not-wet/not dry, not good/not bad. The analysis illustrates that the Dry/Wet binary is an ideal, since real babies soil their diapers no matter how virtuous the mother. Likewise, real mothers are never just good or bad but do the best they can. The semiotic research process identified a distinct cultural space and competitive positioning for Baby’s Best as a realistic brand for real mothers, and proposed a creative strategy that substituted bright primary colors for soft pastels and featured happy, active babies and independent moms. The semiotic strategy grew brand value for Baby’s Best by strengthening the brand’s competitive positioning in relation to category leader Pampers.

Image Credit: “Times Square, NYC 2011″ by Pauldc. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Signs, strategies, and brand value appeared first on OUPblog.

Reflections on the Reith Lectures: the future of medicine

The Reith lectures were inaugurated in 1948 by the BBC to celebrate and commemorate Lord Reith’s major contribution to British broadcasting. Many distinguished names are to be found in the alumni of lecturers, whose origins are not confined to this sceptred isle in which the concept of these educational, thought-provoking radio talks were conceived. The first lecture in 1948 was delivered by the distinguished philosopher and Nobel Laureate Bertrand Russell, who talked on ‘Authority and the Individual’, and subsequent talks covered in these lectures have embraced a wide range of topics from the arts, humanities, politics, economics, to the scientific disciplines often thought unfairly to be too abstruse a subject for the ordinary non specialist listener.

Medically-themed lectures have included the 1976 lectures ‘Mechanics of the Mind’, on the topic of brain and consciousness, delivered by Colin Blakemore, aged 30, and at the time the youngest Reith lecturer to Sir Ian Kennedy’s series on ‘Unmasking medicine’, which argued that medicine was too important a subject to be left to doctors alone. Steve Jones, in 1991, talked about the ‘Language of Genes’, and in 2001 the distinguished gerontologist Tom Kirkwood discussed issues about aging and man’s inevitable fate, in talks entitled ‘The End of Age’.

Atul Gawande. John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Atul Gawande. John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Atul Gawande, a Harvard Professor, distinguished writer, and last year’s Reith Lecturer, must surely be the first practicing surgeon to deliver these lectures. His topic was ‘The Future of Medicine’. The four lectures were full of good simple advice and we could all profit from some of the ideas discussed whether we are deliverers or consumers of healthcare. Dr Gawande’s great interest is in the currently fashionable topic of patient safety, and he has made important contributions in this area with his research and writing, and with the concept of checklists. Patient safety and human error are interlinked, and doctors fail because of the immense complexity of multiple tasks and processes involved in day to day patient care. Systems fail, although individuals often take the blame. He suggests that in the 21st century, the volume of knowledge has exceeded individual capabilities, and systems have to be designed to minimize problems.

Good healthcare systems require efficient, comprehensive, and accessible primary care systems with well coordinated patient pathways. In addition, safe hospital systems are needed to complement the primary care systems. Even simple tasks such as hand washing can make a difference. Constant encouragement is required to prevent staff burnout, and this happens because no one seems to notice excellence and tend to concentrate continually on negative aspects of healthcare. In addition, high technology medicine needs to be used with caution and appropriately with special reference to antibiotic usage, surgical procedures and imaging, areas which are growing unchecked in the Western world and will become issues in the developing nations too.

As societies age, end of life issues become important, and it is critical to acknowledge individual needs by simple tasks, such as asking patients what they want. Doctors need to talk less and listen more. We need to ask patients what they know and fear about their illness and what outcomes they are happy to accept. We need to refrain from ‘overmedicalizing mortality’,

The four lectures were illustrated with personal anecdotes and experiences, from the ill health of family members, as well as an interesting case from the history of medical imaging.

Gawande quoted the story of Forsmann, the maverick doctor from Eberswalde in Germany, who in 1929 performed a cardiac catheter on himself to push back the frontiers of knowledge and paid the price by being sacked from his job. Today this procedure is routine and saves many lives, but would mavericks like Forsmann be nurtured in today’s modern over-regulated climate?

Header image: Sound studi0. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Reflections on the Reith Lectures: the future of medicine appeared first on OUPblog.

Who was the first great Shakespearean actress?

When women first appeared on the English stage, in 1660, Shakespeare’s reputation was at a relatively low ebb. Many of the plays which provide his best female roles, especially the romantic comedies but also including for instance Measure for Measure, Troilus and Cressida, Antony and Cleopatra, Cymbeline, Coriolanus, and The Winter’s Tale, had fallen into disfavour.

In the years that followed, other plays, such as Romeo and Juliet, Richard III, and Macbeth, were acted only in radically adapted texts which distorted the female roles. Moreover, evidence is scarce; theatre criticism was slow to develop and accounts of performances tend to be anecdotal and effusively uncritical.

The first female Juliet appears to have been Mary Saunderson, to Henry Harris’s Romeo in 1662 when her future husband, Thomas Betterton, played Mercutio. Later she acted admirably as Ophelia and Lady Macbeth but nothing I have read characterizes her as great. Elizabeth Barry (c.1658–1713) succeeded her as Betterton’s leading lady, excelling in pathetic roles and achieving her greatest successes in the heroic tragedies of her own time. Conversely Anne Bracegirdle (c.1671–1748), renowned for her modesty in an age when most actresses were notorious for flamboyant sexuality, was clearly a great comic actress.

Sarah Siddons as Euphrasia, 1782. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Sarah Siddons as Euphrasia, 1782. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. She was the first Millamant in William Congreve’s The Way of the World (1700), but her principal Shakespeare roles were given in heavily adapted texts — Charles Gildon’s version of Measure for Measure and George Granville, Lord Lansdowne’s of The Merchant of Venice, in which she became the first woman to play any version of Portia.

Another fine comedienne, Anne Oldfield (1683–1730), played almost no Shakespeare. Margaret (‘Peg’) Woffington (c.1714–60) worked with David Garrick and was for a while his lover; in breeches roles she appealed especially to women in the audience, but her harsh voice resulted in her being dubbed ‘the screech-owl of tragedy’. Garrick’s principal leading lady, Hannah Pritchard (1711–68), supported him successfully in Macbeth even though, by her own admission, she had read only the scenes in which she appeared; this provoked Samuel Johnson to tell Sarah Siddons that ‘she no more thought of the play … than a shoemaker thinks of the skin out of which the piece of leather of which he is making a pair of shoes is cut’.

And Sarah Siddons (1755–1831) is the first indisputably great Shakespeare actress, a performer of towering reputation whose art inspired eloquent tributes in both prose and verse from some of the finest writers of her time, as well as almost as many paintings and drawings as there are of Garrick. They include a splendid canvas by Gainsborough and Sir Joshua Reynolds’s commanding portrait of her as Melpomene, the Greek muse of tragedy. Shadowily visible behind her stand embodiments of the Aristotelian emotions of tragic passion, Pity and Terror.

The post Who was the first great Shakespearean actress? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers