Oxford University Press's Blog, page 673

April 25, 2015

Remembering Anzac Day: how Australia grieved in the early years

Today marks the 100th anniversary of the start of the Gallipoli campaign of the First World War, which took the lives of over 10,000 members of Australian and New Zealand Army Corps. A momentous event in both nations’ histories, it is marked every year as Anzac Day. We take a look at how Australians began commemorating Anzac Day in the first few years with the following extract from the forthcoming The Centenary History of Australia and the Great War Series – Volume 4: The War at Home, by John Connor, Peter Stanley, and Peter Yule. (Please note: This is an excerpt from a manuscript. This book is currently being edited and proofread; the final product may differ.)

‘Anzac’ (soon transmuting from acronym to word) came to sum up the Australian desire to reflect on what the war had meant. What was the first Anzac Day? At least four explanations exist of the origins of the idea of Anzac, the most enduring legacy of Australia’s Great War. Gareth Knapman has shown that Adelaide held an ‘Anzac day’ on 15 October 1915, a renaming of the traditional eight-hours festival. Eric Andrews dubbed the seemingly ‘spontaneous’ ceremonies held in Cairo and London on 25 April 1916 ‘a propaganda triumph’.

Early in 1916 the Bulletin urged the government to ‘take out patent rights for the name “Anzac”’. Unless it did, the name would be used by ‘every quack and dead-beat from Port Darwin to Stewart Island, foreseeing Anzac tearooms, potatoes and pills’. After the war, it hoped, Australians would ‘hold its name only in our songs and traditions’. By 1917 Anzac Day had become established as a major fund-raising day. Sydney’s George Street became ‘a live antbed’ with all of those trying to get into the free concert in the Town Hall, with 3000 people—twice its capacity—trying to get in. At the ecumenical service earlier that day the wife of the Governor-General, Lady Helen Munro Ferguson, dressed in mourning garb as ‘a tribute to the dead of Gallipoli’ and a reminder that Anzac Day at first had no connotation beyond the Dardanelles.

On the first anniversary of the invasion of Gallipoli the Bulletin’s Red Page ran the products of a competition for ‘The Anzac Sonnet’. Although the judges found many ‘fatally flawed by technical errors’ (such gaffes as rhyming ‘saw’ with ‘war’), they demonstrated that at the time the identification of Gallipoli with, as Bill Gammage later put it, ‘nationhood, brotherhood and sacrifice’ had already begun. The journalist Guy Innes, despite the solecism of using the awkward ‘withnesseth’, wrote of the Anzacs being ‘baptised by fire’ who ‘made fair Australia’s honour with their dying breath’. The winner of the competition, Bartlett Adamson, expressed the essence of Anzac:

And Anzac now is an enchanted shore;

A tragic splendour, and a holy name;

A deed eternity will still acclaim;

A loss that crowns the victories of yore …

In 1915 enough babies to fill a crèche were christened ‘Anzac’, although the Protection of Anzac regulations curtailed that, and prevented bereaved mothers naming houses after the place where their sons died. ‘Mother of One’ objected that ‘we’ve got into the way of calling the little pet “Anzay” [sic]’ and, wondering whether to use his second name, ‘Pozières’, concluded: ‘I tell you what, I wish the old war had never started!’8 No doubt it was a sentiment widely shared.

To whom did the war now belong? A century on, the rhetoric of official commemoration would assert that ‘all Australians’ shared in the pain and the pride. The contemporary record suggests that just as the experience and sacrifices of war were unevenly distributed, so its memory was felt more in some than others. Anzac Day—the ‘Diggers’ day’—developed through the advocacy of returned soldiers’ organisations, and through the energy of several influential figures, notably Canon David Garland, whose formula of light Christian symbolism found a ready acceptance among those with most cause to want to recall the sacrifices and comradeship of wartime. In a deeply sectarian society Catholics long remained largely excluded from civic rituals, but Anzac comradeship extended beyond the liturgical, most characteristically expressed in the great Anzac Day marches that became the norm in communities throughout the nation by the late 1920s. In the capital cities huge, mostly silent crowds—80,000 in Sydney in 1928—watched columns of returned men—perhaps 15,000 of them—marching to reunions and commemorative gatherings. By 1930, aided by the introduction of the microphone and the wireless, the ‘dawn service’ had become established as the uniform commencement to a morning of solemn remembrance, albeit one typically shared in the privacy of a living room.

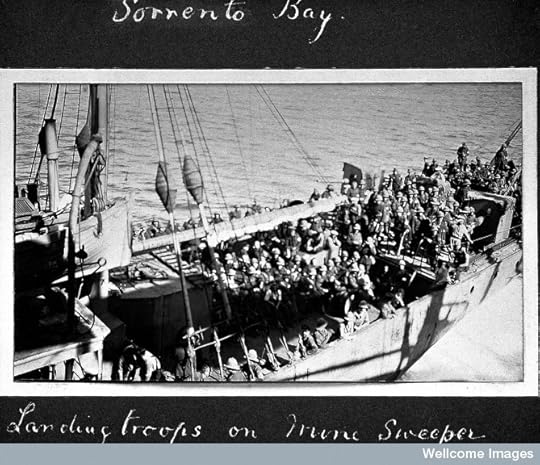

First World War: landing troops on mine sweeper. Photograph collection of Lieutenant Colonel G.J.S. Archer, RAMC. 9, album of photographs of No. 40 Field Ambulance at Gallipoli during the First World War. 1915. Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

First World War: landing troops on mine sweeper. Photograph collection of Lieutenant Colonel G.J.S. Archer, RAMC. 9, album of photographs of No. 40 Field Ambulance at Gallipoli during the First World War. 1915. Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Although, as we have seen, the war intruded into homes and communities, the dead lay in graves and (for about a third of them on battlefields) far away. Almost no Australian parents were granted the opportunity to mourn at their dead son’s graveside, ‘a crucial condition of wartime loss’ for Australians, Bart Ziino judges. (The exceptions were those who died lingering and often painful deaths in hospitals at home or who died post-war.) Comrades, brothers, chaplains, units and ultimately the war graves authorities went to considerable trouble to send to families depictions and descriptions of, as a booklet put it, Where the Australians Rest. This brought a measure of consolation; perhaps as much as they expected.

Pat Jalland, the premier authority on Australian ways of dying, concedes that the surprisingly limited evidence of how families actually coped with soldiers’ deaths leaves us largely ignorant of all but the more extreme cases. One is Garry Roberts, whose enormous memorial scrapbooks in the State Library of Victoria testify to his obsessive search for certainty about his son Frank’s death. Another is John Cooper, who, traumatised by his experience as a stretcher-bearer at Pozières, was so violent towards his family that they bured him in 1935 in an unmarked grave. Jalland is surely right in observing that ‘large numbers of parents and widows may have remained in a state of chronic grief’. But she shares with the premier scholar of war memorials in Australia, Ken Inglis, a scepticism over the consolatory value of the public war memorials largely constructed in the years after the war, too late to serve as ‘sites of healing meditation’. At the same time, the stereotype of the elderly bereaved mother laying a wreath at a municipal war memorial remains a compelling image.

It was, a writer in the Lone Hand thought, ‘not possible to find even a single individual in the Commonwealth who was not an acquaintance at least of someone who died a hero’s death’. (The easy recourse to describing war dead as ‘heroes’, long in abeyance, enjoyed a renaissance in popular use a century on, an expression of the politicisation of more recent wars through which we see the Great War.) Even at the time, however, ‘in the magnitude of a country’s bereavement there is something which leads to almost callous indifference’; that is, ultimately bereavement was a personal and a family matter. Efforts both determined and sensitive have been made to penetrate the privacy of grief, yet ultimately what has been most studied is that which was most visible: the extraordinary phenomenon of war memorials. This is not to say that memorials do not reveal a complex pattern of personal and public grief, mourning and memory, but they do not disclose the full emotional impact of the war; that is, perhaps, gone beyond recall. Although the difficulties of learning the secrets of a private people’s hearts have so far made it almost impossible to discern the real effects of the war, hints suggest that the war, and the psychic disruption it brought, made real inroads into the certainties prevailing in 1914. As Jill Roe found, the Theosophical Society of Australia doubled its membership by 1919, to more than 2300. Conversely, as the 1933 census disclosed, ‘the Christian churches had lost their hold on as many as 20 percent of the population’. Some might have embraced the consolations of Christianity in wartime, but for others the travails of loss and trauma eroded their faith.

As Ken Inglis has shown in his masterly study of ‘war memorials in the Australian landscape’, the commemoration of war barely impinged upon Australian consciousness in 1914. From 1915 memorials began to appear, disturbingly unfinished in lists of names and date ranges. War memorials of many kinds became a part of life. (If asked to unveil an honour board, a woman asked the Sydney Mail’s ‘Housewife’ whether it was necessary to say anything. ‘Not if she is nervous’, was the reply.) Memorials naturally reflected the communities that erected them. Bill Stegemann thought that they expressed a mixture of ‘grief and pride’. (Or indeed unease—Koroit’s Methodists began an honour roll in 1916 but, reflecting its ambivalence in wartime, the town as a whole took until 1928 to erect a memorial.)

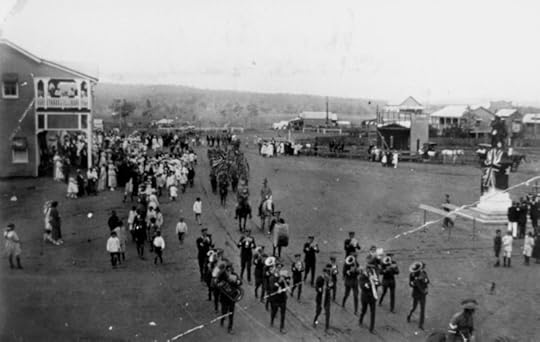

Returned servicemen and a marching band form a procession along Lamb Street for the unveiling of the Murgon War Memorial on Anzac Day, 1920. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Returned servicemen and a marching band form a procession along Lamb Street for the unveiling of the Murgon War Memorial on Anzac Day, 1920. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Disputes occurred over the position, size, cost and especially the design of memorials. Wagga’s archway proceeded only after a law suit; Goulburn’s rocky hillside site was among thirty-seven designs considered and succeeded only through the advocacy of Mary Gilmore, but even then controversy dogged the venture for longer than the war had lasted. Sectarianism almost scuppered the unique memorial at Berridale, a township on the Monaro, which erected a marble wayside crucifix of the kind the AIF had encountered in France and Belgium. Although the cross was proposed by the town’s Anglican minister, the state government’s advisory board considered it ‘too overtly Roman Catholic’. After ‘intense difficulty and frequent agitation’, as the RSL newspaper Reveille reported, it was accepted, most townsfolk accepting that the figure of the crucified Christ was a fitting symbol. The 600 people who attended the unveiling in November 1922 applauded references to the memorial’s originality, a curious blend of solemn remembrance and local boosting. The great debate concerned the form such memorials should take. Neville Howse, VC, spoke for those who favoured useful memorials: ‘no cold stone or brass for me; gather a big lumping sum … and expend it later in assisting the education of the loved ones of those who have made the great sacrifice’.

Knowing of the widespread desire to erect statues, the New South Wales Public Monuments Advisory Board advised that gateways, obelisks, arches or gardens would be preferable to a poorly executed statue. In fact, most memorials do not conform to the archetypal digger-on-a-pillar. A vogue for ‘Trees as Memorials’ arose. The movement for living memorials was most strongly taken up in Victoria, yet one of the first memorial trees was planted in Annandale in Sydney to commemorate Harry Jiffkins, the suburb’s first dead ‘hero’, who died on 6 May 1915. In 1916 the local council planted a tree that, commentators thought, would become known as the ‘Jiffkins Tree’, at which ‘children of future generations will be told the story of why Harry Jiffkins fought, and the splendid cause in which he died’. An elaborate service was held in the street in May 1918 but, sadly, the tree no longer exists, nor is Harry remembered locally.

A version of this article originally appeared on the Oxford Australia blog.

The post Remembering Anzac Day: how Australia grieved in the early years appeared first on OUPblog.

Finding Trollope

Finding Trollope is one of the great pleasures of life. Unlike other Victorian authors Trollope is little studied in schools, so every reader comes to him by a different path. It might be a recommendation by a friend, listening to a radio adaptation or watching a TV production that leads to the discovery of Trollope and his world.

I stumbled across Trollope in the early 1990s. I had recently graduated, moved to London and found myself working in a bookshop. A new edition of Trollope’s novels had just been published, and it was at the suggestion of the publisher’s rep that I picked up my first Trollope, Barchester Towers.

Over the next few years I would return again and again to Trollope when I was short of something to read. He became my default author. I read the novels in no particular order, just picking them up in bookshops whenever I could find them. I developed a strong relationship with Mr Trollope, his authorial voice connected with me, and his characters seemed so real that I felt that they were alive. At this time I was a lone Trollope. I didn’t know anyone else who read him and the only outlet for my enthusiasm was leaving quotes on friends’ answer machines, ‘nuisance quotes’ they became known as.

This was neither satisfactory for myself, or my friends. What I needed was a community of like-minded enthusiasts, and I found them in The Trollope Society. The first Trollope Society event that I attended was a garden party in Hampshire. I had got it into my head that it was a fancy dress affair, so turned up on a blisteringly hot summer’s day in full nineteenth century clerical garb, complete with gaiters, frock coat and shovel hat, dressed to my mind as the very picture of Archdeacon Grantly. The other members of the society were delighted with my efforts. I was warmly welcomed and mistaken by everyone for Mr Slope.

The Trollope Society is a wonderful institution. It is run by volunteers, who give up their time to run seminar groups up and down the country, to arrange play readings at the Royal Opera House, or plan trips to Ireland, Scotland or anywhere with a Trollope connection. We plan parties, lectures, dinners and holidays, and at the heart of it all is a love of reading Trollope.

The Great Barsetshire Balloonathon. Photo used with permission of The Trollope Society. Do not reproduce without permission.

The Great Barsetshire Balloonathon. Photo used with permission of The Trollope Society. Do not reproduce without permission.We have over the last few years been planning celebrations for Trollope’s 200th anniversary in 2015. In February we launched the bicentenary with an international balloon race, ‘The Great Barsetshire Balloonathon’, with balloons released in London, New York, California, Belgium, Australia, and Japan. As we approach the date of Trollope’s birth, 24 April, things are reaching fever pitch. The British Library is hosting ‘A Celebration of Anthony Trollope’ on 23 April and the society is commemorating the 200th anniversary of Trollope’s birth with a dinner at the Athenæum the following day. Later in the summer the Trollope Society is hosting the Alliance of Literary Societies AGM weekend in York. In August a new play, Lady Anna: All at Sea, commissioned by the society will be performed at The Park Theatre in London. The bicentenary year draws to a close on 4 December with a special Evensong at Westminster Abbey followed by a dinner at the House of Lords.

Aside from these grand celebrations, the aim of the bicentenary year is to get people to pick up a Trollope and give him a go. On 24 April, in partnership with Oxford World’s Classics, we are holding a Book Giving. We are asking anyone who has read Trollope to give a copy of one of his novels to a friend, and asking the recipient to let us know what they think on our Facebook page.

The Society is also holding a Trollope Big Read on Facebook and in our local seminar groups. Starting on 24 April, everyone is encouraged to join in and read Barchester Towers. John Bowen, the editor of the new Oxford World’s Classics edition of the novel, will be joining the Facebook group so we will have expert guidance. If you haven’t yet found Trollope, there’s never been a better time to give him a go!

Headline image credit: Trollope 200, used with permission from The Trollope Society.

The post Finding Trollope appeared first on OUPblog.

April 24, 2015

Ten tips for making a successful clinical diagnosis

Making a successful clinical diagnosis is one of the most important things a medical student can learn, and it’s not as easy as matching a list of symptoms to a condition or illness. Editor of Clinical Skills, T. A. Roper, gives us a run-down of ten tips and skills he deems most important for making a successful clinical diagnosis.

* * * * *

1. Listen to the presenting complaint

This is both the beginning and the cornerstone of the diagnostic process. It’s the key reason(s) why the patient is seeking medical help, so resist the temptation to jump in with your set of pre-rehearsed questions, and listen. Sometimes this is straight-forward, but unfortunately we humans are complex creatures. We carry our own set of unique expectations, driven by culture, taboos and individual eccentricities that can lead to cross-wires and an unfulfilled consultation. Explore their ideas, concerns and expectations (ICE); a model used in General Practice that adds a visceral dimension to the complaint. “What do you think is causing the problem?” (Ideas); “Do you have any particular worries about this?” (Concerns), and “what were you hoping from this visit?” One big tip is that cancer is a huge worry and is often lurking in the back of patients’ minds.

2. Listen to the past medical history

The past can sometimes point to the present. The patient may present with a flare up of a previous medical condition, or may suffer a complication of a previous problem. For example a patient who has had previous bowel surgery can develop an acute bowel obstruction because of adhesions produced by the past surgery. Conversely it can help by ruling out a possibility. A patient with right lower quadrant pain in the abdomen cannot have appendicitis if the appendix has already been removed.

3. Listen to the drug history

According to the National Institute for Health and Care Institute (NICE), it is estimated that 6-7% of hospital admissions are due to adverse drug reactions. As these are under-reported it’s likely to be even more. This does not include expected side effects from medication or even the misery patients can experience due to errors in drug prescription. They can be a powerful source of suffering and to paraphrase an old saying, “Drugs are poisons with the occasional beneficial side effects”, So beware and be aware.

4. Listen to the carers

The carers will have invaluable insights into the patient’s problems and their behaviour. They’re indispensable when it comes to certain presentations such as blackouts, where an eye-witness account is essential, or if the patient has a poor memory for reasons such as delirium or dementia.

5. Listen to the health care professionals

This can be nurses, health care assistants, therapists, or anyone who has been in contact with your patient. People vary in how they report signs and symptoms. Some exaggerate, some underplay their symptoms and some get it just right (Goldilocks patients). Unfortunately you don’t always know which camp they fall into. A healthcare professional, on the other hand, should be able to give you a dispassionate, accurate record of any sign or symptom to help in your quest for a diagnosis.

6. Listen to what is not said

This tip may only be needed occasionally but can be powerful if spotted. I looked after a man who had repeated admissions to hospital with chest pain, and yet when he arrived he often seemed to be well and was certainly independent. He did however have a wife who had advanced dementia. The penny dropped later in his admission. Most patients who have a sick relative are anxious to go home so they can look after their spouse, sometimes putting their own health in jeopardy. However, at no point during his time with us did this man mention his wife to anyone. It wasn’t because he didn’t love his wife, but, rather than admit he couldn’t cope, he escaped his dilemma by assuming the sick role and getting himself admitted.

Doctor discussing diagnosis with patient, by CDC. Public domain via

Doctor discussing diagnosis with patient, by CDC. Public domain via

A thousand words: Photography in the Lincoln era

Lincoln was not the first president of the United States to be photographed, but he was the first to be photographed many times, and not only in the portrait studio. His photo archive makes him a modern figure, a celebrity. His short presidency happened just at the time when photography first became straightforward and reliable. Many of the Lincoln photographs were taken by Scottish-born Alexander Gardner. It was Gardner who took the magnificent photograph of Lincoln on 6 November 1863 at his fashionable studio in Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington DC. But it was Gardner who also made photographs of Lincoln visiting Civil War sites and, after the assassination, took the extraordinary picture of the co-conspirator Lewis Payne held in custody at the Navy Yard.

Later he caught the distant but terrible view of the assassination executions, a photograph that stands at the head of a photojournalistic line stretching through toTiananmen Square. Add also to this Gardner’s fuzzy picture of the crowd on the afternoon of Lincoln’s Gettysburg address, taken almost exactly one hundred years to the day before the assassination of the 35th president in Dealey Plaza, Dallas.

Each one of these images was caught in silver salt in a film of collodion spread on a glass plate. The silver image was a negative, from which many positive prints could be made. This was the new, dependable and greatly superior method of photography that had largely displaced the earlier daguerreotype. Collodion was a transparent coating used to bind the light-sensitive crystalline particles of silver bromide. It was made by dissolving gun-cotton in an ether/alcohol solvent, the same gun-cotton that was to be used as the explosive in the shells of all the wars of the late nineteenth century, and that was made from the cotton of the southern states.

The physicist Lawrence Slifkin called silver photography a miracle. What he meant was that some Goldilocks physics and chemistry was at work in the tiny crystals of silver bromide. As a result, a single photon of light (a gleam from Lincoln’s button shall we say) leaves a minute and invisible footprint in a silver bromide crystal, a speck of a few silver atoms. This is Slifkin’s miracle, the ‘latent image’, which can later, at leisure, be developed by chemical treatment. The dots which are the invisible specks can be joined to produce a photograph. And the single negative image can be used in turn to produce unlimited positive prints. So we have photography as we know it. From Alexander Gardner, we go directly to the movies, to photojournalism, to Kodak and mass photography, democratizing the image.

Lincoln Portrait, by Alexander Gardner. Public domain. Held by Library of Congress.

Lincoln Portrait, by Alexander Gardner. Public domain. Held by Library of Congress. For more than 100 years, silver bromide was at the heart of all this. Then, over twenty years, it disappeared, replaced by digital image-making, nothing to do with silver. When Bunker Hunt cornered the world silver market in 1980, Hollywood was alarmed as much as the Fed, and urgently demanded movie producers to leave less film on the cutting-room floor. In 1979, two-thirds of US silver production went to photography. By 2013 it was less than one-tenth, and falling fast. The disappearance of silver photography is one of the greatest of technological mass extinctions.

More than half of the life history of silver photography happened without the benefit of scientific theory. It turned out to understand what happens when a particle a light, a photon, strikes a particle of silver bromide needed a bit of Einstein. So it was not until 1938, eighty years after Gardener and Lincoln, that the Bristol physicists Ronald Gurney and Nevill Mott wrote the landmark scientific paper which explained it all. The theory was an early example of applying quantum mechanics to chemistry. When the back-of-the-envelope calculations were done, it was clear how Goldilocks was at work. The sequence of atomic processes which lay between the arrival of the photon on the photographic plate and the development of the silver speck which it produced were ‘just right’ at every stage. In the century of silver photography there were many technical developments but nothing ever replaced silver bromide at its heart. Silver photography made the image-rich world of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and its discovery was one of the most pervasive and transformative events in the history of materials.

Featured image credit: Lewis Payne (co-conspirator), by Alexander Gardner. Public domain. Held by Library of Congress.

The post A thousand words: Photography in the Lincoln era appeared first on OUPblog.

April 23, 2015

No frigate like a book

A friend has recommended a new novel to you. You save it for the holiday and then, sitting out in the sun and feeling relaxed, you start reading. And something strange happens: the little black signs on the page before your eyes draw you into a world that has nothing to do with the sights and sounds of your surroundings, which quickly fade from your consciousness. Your thoughts are shaped by ideas that are not yours, your feelings are stirred by unfamiliar emotional currents, and your mind is populated by newly-minted images. People you have never encountered before become real to you, conversations unlike any you have taken part in resound in your ears, scenes foreign to your experience unfold around you. Even your body responds to this new world you have entered; your skin tautens or your eyes prick with incipient tears or you laugh out loud.

And yet—and this is what is strangest of all—you remain perfectly aware that you are reading a book, and that your experience of new thoughts, feelings, and images has been brought about by someone’s skilful handling of language, by his or her precise choice of words to convey sights and sounds, motions and emotions, sculpting sentences into sequences that amuse and arouse, arrest and lull, increase tension or achieve relaxation. You may know a great deal or nothing at all about this author; the words may have been written a year or several centuries ago. But your pleasure in being carried along by the fiction is enriched by your admiration for the creativity of the person who created it.

These are some of the remarkable features of an experience that we tend to take for granted. Of course, much of our reading of literature—in the broadest sense of that word—involves the enjoyment of what is familiar rather than the feeling of being taken into new worlds. But even the most formulaic of genre novels or the most conventional of poetic stanzas can surprise one with a little charge of the unfamiliar, a sense that the exact tinge of a colourful scene, or the fine nuance of an expertly conveyed emotion, breaks new ground in one’s appreciation of what it means to live on this earth.

The challenge for the literary critic or theorist, as I see it, is to understand and articulate this experience, which has its analogies in the other art forms too. Moreover, it is important to do so without becoming, on the one hand, captivated by the dream of reducing all aesthetic matters to the facts of scientific truth, or on the other hand, becoming prey to a mystical apprehension shrouded in vagueness and hyperbole. This is not to say that we can’t learn interesting details of the operations of the brain encountering a poem from cognitive theorists, or valuable sociological knowledge from carefully accumulated data sets; nor is it to devalue accounts of literary experience that are themselves highly literary. But when I read Donne’s “Valediction: Forbidding Mourning” and feel all over again that clutch at the heart when the perfect rhymes reinforce the speaker’s loving reassurance; or when I see on stage once more—but always as if for the first time—human lives undergoing a sudden and dangerous transformation when Shakespeare’s Beatrice utters her sober command, “Kill Claudio,” no amount of scientific enquiry or lyrical imagery can do justice to the intensity and singularity of what I live through.

There are no doubt a number of different vocabularies and philosophical approaches that would be helpful in meeting this challenge; the language I have found most useful is drawn, above all, from the ethical thinking of Emmanuel Levinas (even though he did not himself rate literature very highly among human endeavours), the meditations on literature of Maurice Blanchot, and the notions of hospitality, justice, and responsibility of Jacques Derrida.

The work of literature or any work of art, if it achieves what art uniquely can achieve, calls out for a response that does justice to its uncharted ways of thinking and feeling, modes of knowledge, or emotional experience whose newness may be combined with a sense of rightness and truth. That response is deeply pleasurable (though what is depicted in the work might be painful) because it involves a momentary expansion of one’s being, a venture into places formerly blocked off, a sharpening of a dulled palate. And although it’s never possible to predict exactly what effect a work will have on a reader, or even to state afterwards what its effect has been, one thing is certain: we’re never exactly the same when we’ve been through the powerful transformations a great work of literature can perform. Literature is a social good not because it can be hijacked for this or that cause, but because it fosters an openness to otherness and to the future.

Image Credit: “Reading” by Jonathan Kim. CC BY NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post No frigate like a book appeared first on OUPblog.

Advocacy and pedagogy in secondary school singing

Music as a school subject, it so often seems, retains its apparently perilous position in the school largely as a result of the unstinting pressure of advocacy groups. The 2004 Music Manifesto that underpins much of the current drive to keep school music alive was unashamedly “a voluntary, apolitical 13-strong Partnership and Advocacy Group”. Personally, I find this slightly challenging because I was fortunate enough to attend a school during the 1960s where advocacy was quite unnecessary. The important position of music was never doubted within a curriculum organized along classical, liberal principles. Plato’s instruction that “children enter school at six where they first learn the three Rs (reading, writing and counting) and then engage with music and sports” was part of the very fabric of the place.

In mature years as a researcher, I have come to realize just how privileged I was. Advocacy of music in an educational world that sees little value in it seems an ever-present necessity for many children if they are to receive any music education at all. Much of this advocacy, however, seems to me to be based upon extrinsic benefits. Music develops perceptual and language skills; it helps with literacy and numeracy; it promotes intellectual development and creativity; it engenders social and personal development and promotes health and well-being. These are all very worthy in themselves, but what about music for music’s sake? And how valid are the claims for extrinsic benefits anyway? How do we know that this isn’t just another so-called “Mozart effect,” ill-supported by serious, replicable research? How can we be confident that other activities such as drama or foreign languages don’t equally confer such benefits?

Susan Hallam has recently conducted an extensive analysis of this question. She concludes that there is indeed a strong case for the benefits of active engagement with music throughout the lifespan. She adds, though, a most important caveat: “…the positive effects of engagement with music on personal and social development only occur if it is an enjoyable and rewarding experience. This has implications for the quality of the teaching.” If this is true for music in general, how much more true might it be for singing, a musical activity that has had more than its fair share of advocacy in recent years? Graham Welch speaks for many when he writes about the “sense of embarrassment, shame, deep emotional upset, and humiliation” felt by many adults recalling their experience of school singing. He notes how these feelings are “usually accompanied by reports of a lifelong sense of musical inadequacy.”

Courtesy of Martin Ashley

Courtesy of Martin Ashley My own position on this is quite clear. As well as being positive and non-threatening, singing must serve a clear purpose in the development of musical skill and knowledge, and be perceived by students to do so. Mere participation advocacy is insufficient and there’s been rather too much of it. What is needed is the advocacy of good pedagogy and the advocacy of a clear pedagogical rationale. The late Brian Simon wrote that “pedagogy—the act and discourse of teaching—was in England neither coherent nor systematic, and that English educators had developed nothing comparable to the continental European ‘science of teaching’.” Recalling this, Robin Alexander has been critical of approaches to innovation that “rely on large print, homely language, images of smiling children, and populist appeals to teachers’ common sense.”

Why do we want children to sing? Why should it be advocated by Darren Henley that all children (boys as well as girls) should sing in school up to the age of fourteen? Could such an ambition be counter-productive if the consequences are boredom, anxiety, or even humiliation? Or if children develop no skills or learn nothing worthwhile about music through singing? Young people, boys in particular, do sing. Listen outside the bathroom door or watch them when their iPods are plugged in and they think they’re not being judged. Why should they then waste their time on a “school song” that embarrasses, bores, and frustrates them because it’s pitched outside the tessitura of their changing voices and contributes nothing positive to their learning? What is needed is the advocacy of a sound music pedagogy in which singing has a clear part to play in the development of audiation (the ability to hear and think about music internally). OFSTED have made their second priority for improving music education to “improve pupils’ internalization of music through high-quality singing and listening.” This demands more than homely language and images of smiling children.

The post Advocacy and pedagogy in secondary school singing appeared first on OUPblog.

What is Positive Education? Lessons from a Year 3 classroom

What is Positive Education? This is a question I am asked on a weekly, sometimes daily, basis. Whenever I am asked this question, what immediately comes to mind is a visit to Bostock House, one of Geelong Grammar School’s junior campuses.

At the time of my visit, the Year 3 students were preparing to go on a camp. At 8 and 9 years old, the students were quite young to be away from home for three days and two nights. The Bostock staff had decided to focus on teaching the children some skills and mindsets for well-being — and specifically skills of resilience — to help them to really connect with each other and engage fully while on camp. With this end in mind, the teaching staff had taken the research and theory of leading scholars in the field, such as Karen Reivich, Jane Gillham, and Martin Seligman, and explored ways of making key ideas meaningful and relevant for young students.

Throughout the weeks leading up to camp, students completed projects exploring ways in which various plants and animals adapted to the environment as they survived and thrived in different terrains. Students read stories and considered how characters had used their strengths to overcome difficulties and embrace opportunities. The class had completed a (somewhat messy) experiment on the difference between an egg and a bouncy ball… and unanimously decided that they would prefer to go through life with the capacity to ‘bounce and not break’.

The classroom learning had been so well scaffolded, that when the word ‘resilience’ was finally introduced, the students were able to make meaningful insights into how they could be resilient in their own lives on a daily basis. Students provided examples of times they had overcome disappointments, let go of grudges after conflict with a friend, took on an exciting challenge, or came together to support another student during a family difficulty. Students also shared what they had learnt with their parents and families, and the language of resilience spread beyond the classroom and into the home. Needless to say, students used their new understanding and skills to have a brilliant time together while on camp.

Children. Public Domain via Pixabay

Children. Public Domain via Pixabay Now, as an academic, I have always been captivated by the concept of knowledge translation. How do we move advances in science into the realm of real life application? How do we translate a growing evidence base in ways that make a meaningful difference to the community? To me, these Year 3 students discussing, exploring, and applying the skills and mindsets for well-being and resilience in such creative and tangible ways is an example of the translation of science at its best. This is how I understand Positive Education — taking the most recent scientific understanding of physical, psychological, emotional, and social health and making it real, applicable, and helpful for children, young people, adults, and communities.

The official definition, used by Geelong Grammar School, is that Positive Education brings together the science of well-being and positive psychology with best practice teaching and learning to encourage and support schools and members of the school community to flourish. Central to the approach is the Model for Positive Education and its six domains of: positive relationships, positive emotions, positive engagement, positive health, positive accomplishment, and positive purpose. Character strengths such as gratitude, curiosity, forgiveness, leadership, and spirituality, provide an underpinning framework for Positive Education and help to bring core learning to life for members of the school community of all ages.

And why does Positive Education matter? The statistics on depression, anxiety, stress, and other mental health concerns in adolescents and adults are frighteningly high. It is estimated that one quarter of young people in Australia live with a mental illness. Positive Education is a proactive and preventative approach to building well-being and health in schools and communities and aims to reduce the worrisome prevalence of mental illness across the lifespan. There is also the irrefutable fact that students who are physically and mentally well are better equipped to learn and achieve academically and more effectively manage the transition to further study or employment after secondary school. Furthermore, well-being matters — helping students and staff to nurture strong relationships, develop and maintain healthy lifestyles, be engaged in their studies, and give back to the community are valued outcomes in themselves.

Throughout my time at Geelong Grammar School, I was blown away by the skill and creativity of teachers in making the skills and mindsets of well-being real for their students. I witnessed children as young as three and four practicing mindfulness and meditation, older students discussing the importance of growth mindsets in tackling difficult academic concepts, and students of all ages communicating about their emotions and actively looking to support the well-being of others.

Perhaps the only thing that has struck me more than the innovation of the school staff in teaching well-being was the role of relationships and communities in building mental and physical health. In Positive Education, supporting and nurturing the well-being of others and the community is considered as important as looking after the well-being of the self. Schools are dynamic, complex, ever-changing communities. They are also natural homes for the science of well-being. It is the coming together of the skills and mindsets for flourishing and what schools do best in terms of educating young minds that truly paves the way for flourishing futures.

The post What is Positive Education? Lessons from a Year 3 classroom appeared first on OUPblog.

The ‘Golden Nikes’ for Greek tragedy

With Greek tragedies filling major venues in London in recent months, I have been daydreaming about awarding my personal ancient Greek Oscars, to be called “Golden Nikes” (pedantic footnote: Nike was the Goddess of Victory, not of Trainers). There has been Medea at the National Theatre, Electra (Sophocles’ version) at the Old Vic, and Antigone, which recently opened at the Barbican. There are yet more productions lined up for The Globe, Donmar, and RSC.

Most obviously, there has to be the Golden Nike for ‘Best Tragic Heroine’. And it goes to Kristin Scott Thomas for her tense, nuanced and moving Electra – although Helen McCrory’s Medea would win if there were an award for ‘Voice’. (I’m afraid that Juliette Binoche showed that she is better in the cinema than the theatre.) ‘Best Supporting Actor’ definitely goes to Diana Quick’s dignified but hopelessly damaged Clytemnestra in Electra.

In the long run, though, it may be more interesting to think about the huge differences between these three productions, and how each found such very different tensions and tones and thought-patterns in three plays that all come from the same society and setting and the same brief period in the Athens of nearly 2,500 years ago. Medea tapped into a dark undergrowth of resentment and deceit; Electra revolved around the pathology of grief and the cramping bonds of family ties; Antigone brought out the menace of power and the allure of death-wish. And they were so fascinatingly varied in their incorporation of music, for example, their use or non-use of the chorus, their playing on light and dark, and the degree to which they were in some way “Greek”.

The Goddess Nike (Winged Victory) on top of Skipton War Memorial by Chris Tomlinson. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The Goddess Nike (Winged Victory) on top of Skipton War Memorial by Chris Tomlinson. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Naturally, as a translator, I have a special interest in their scripts – the degree of adaptation, their diction and poetry, their use of the familiar and the strange. You might say that they could hardly have been more different. Actually, the range of modern versions is so incredibly various that you could put another twenty versions side-by-side and find them no less different from each other than these three.

Ben Power’s Medea, called “a new version”, was the most adapted and furthest away from the Greek original. Critics praised it as “lean and mean”. This is one way of saying that only about a quarter of the Euripides made it into the version. And there is a significant layer of additions, including most of the opening scene. Power’s priorities are open: he is going for clear basic narrative, simple accessible language. His driving priorities might be put as negatives: “avoid making it difficult or strange or high-flown”. Complex ideas, striking twists of expression, musical sound-patterns: these are all avoided like the plague in this simplified version.

Electra used a pre-existent text by the Irish playwright Frank McGuinness. This is relatively complete and close to the original, and does more to reflect the non-naturalistic dictions and rhythms of Sophocles. The word most used of it by reviewers was “strong”. This is high praise – I would be delighted if my versions were called “strong”. At the same time McGuinness’ language did not surprise or disconcert; it felt well worn rather than fresh.

Anne Carson is the only one of three writers to have worked from the Greek, and so it is all the more remarkable that her Antigone is by far the strangest and most idiosyncratic. Carson is both a classical scholar and an exceptional lyric poet. Her own poetry has an unmistakable “voice” – a poignant terseness, a sardonic wit, and an unpredictable swooping between highly wrought artifice and almost bathetically everyday idioms. She has not changed her voice at all for confronting tragedy, and the result is that this new Antigone has a script that is full of strange surprises and puzzling twists, darting between high peculiarity and deflationary colloquialism. This is not merely willful because the Sophocles original is also variable and unexpected in tonal variation – it is quite mistaken to think that the language of Greek tragedy was level and stately.

At the same time, I have to say that the Carson is so odd and individual that, in my opinion, it works better on the page than it does in performance on stage. So the Golden Nike for ‘Best Acting Script’ goes to Frank McGuinness and the Golden Nike for ‘Best Creative Translation’ to Anne Carson. And what her version does do in the theatre is to call for its audience to listen to every word, and to realise that this drama is not expressed in simple everyday language. I like that. I hope that my versions, in their different way, do the same.

Featured image credit: Winged victory, Nike statue, Rome, Italy, by Mstyslav Chernov. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The ‘Golden Nikes’ for Greek tragedy appeared first on OUPblog.

April 22, 2015

Is asylum a principle of the liberal democratic state?

Asylum is the protection that a State grants on its territory or in some other place under its control—for instance an Embassy or a warship—to a person who seeks it. In essence, asylum is different from refugee status, as the latter refers to the category of individuals who benefit from asylum, as well as the content of such protection. Recently, there has been renewed interest in the debate on asylum. The highly publicised decision by Ecuador to grant asylum to WikiLeaks’ founder Julian Assange in June 2012 (which prompted a Resolution of the Organisation of American States), as well as the international dispute in 2013 involving several countries across the world in the case of Edward Snowden (which prompted the European Parliament to call on European States to grant him asylum) brought this debate back into focus, particularly as it relates to issues of State sovereignty.

The international regime on the status of refugees was born in the inter-war period in the early 20th century. Today, it is internationally agreed upon in accordance with the 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol. Although asylum is a much older institution in international law and its rich historical roots in State practice are well established, the Refugee Convention does not officially recognize a right of asylum. Despite attempts to codify it in international human rights treaties of universal scope, States’ objections left asylum unwritten in the UN system, although international human rights treaties of regional scope in Latin America, Africa, and Europe all recognize a right to asylum. The lack of a “written rule” in the UN system has contributed to the perception that there is no right to asylum in international law, other than a right of States to grant it at will.

Yet international law is not only about written rules, but also about unwritten principles. The actual legal rules exist to carry an idea of Justice at the service of the human person and therefore their lawfulness requires that they comply with such ideals. The former President of the International Court of Justice, Dame Rosalyn Higgins, expresses this duality in the following terms: “International law is not rules. It is a normative system…. The role of law is to provide an operational system for securing values” (Problems and Process, 1995).

Asylum has long constituted one of the fundamental principles ensuring the well-being of human persons. By providing a historical normative framework common to different societies, it has shaped relations between sovereigns. Evidence of its ancient normative character can be found in its nature as a religious command, a call for divine protection against human injustice. All three monotheistic religions impose a duty of hospitality and protection to strangers, which constitutes the anthropological and historical background to the law and practice of asylum over time.

Today, asylum is enshrined in most constitutions across different legal cultures. They all draw from the liberal-democratic tradition that emerged from the French Revolution, which changed the conception of the State and the relationship between individuals and the State. The wording of constitutions and the broad range of beneficiaries of asylum reflect the historical tradition of an institution that offers protection on a variety of grounds, including but not limited to those that give rise to refugee status. In addition to refugees, those who flee persecution on account of their fight for freedom, democracy, and the rights of others are also protected by asylum.

The constitutional rank of asylum speaks to its nature as a ruling principle of the State itself and the values that it protects worldwide. As such, it informs international law itself. The protective nature of asylum is therefore twofold. On one hand, it protects the person who is persecuted, and on the other, it protects the higher values upon which the State is founded: freedom, justice, democracy, and human rights. These values also form the core of international law, recognised in Article 1 of the United Nations Charter on the purposes of the United Nations. The continuous historical presence of asylum across civilizations and over time, as well as its crystallization in a norm of constitutional rank among States worldwide, suggests that asylum constitutes a general principle of international law, and is legally binding when it comes to the interpretation of the nature and scope of States’ obligations towards individuals seeking protection.

Image Credit: “Refugees from DR Congo board a UNHCR truck in Rwanda” by Graham Holliday. CC BY NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Is asylum a principle of the liberal democratic state? appeared first on OUPblog.

An embarrassment of riches

A priest can be defrocked, and a lawyer disbarred. I wonder what happens to a historical linguist who cannot find an answer in his books. Is such an individual outsourced? A listener from Quebec (Québec) asked me about the origin of the noun bar. He wrote: “…we still say in French barrer la porte as they still do (though less and less) on the Atlantic side of France. I understand bar the door is also used in English…” and added that, according to what he had heard, bar might be of Celtic or of Germanic origin. He would like to know what the etymology of this word is. The answer to this question is too long for my monthly gleanings, and I decided to devote a special post to it, though I am afraid that in the end our correspondent will be none the wiser.

Only two things are clear and indisputable: in English, bar is from Old French, and this French word has cognates in several Romance languages. However, the Latin source is absent, which seems to suggest that the Romance word was borrowed, and Celtic has often been advocated as the lender. But this path of discovery has a prehistory. The earliest hypothesis on the origin of bar known to me occurs in the English etymological dictionary by Franciscus Junius, who can be called the founder of Germanic philology. He died in 1677; his dictionary was published posthumously only in 1743. Junius cited (without comments but, seemingly, with approval) an earlier conjecture that the word goes back to Hebrew baria, which he glossed as “vectis” (Latin), that is, “a strong pole, bar, crowbar, etc.” (here and below, I will reproduce the Hebrew forms as I found them in my authors). The correspondence looks perfect, but, as always when borrowing is suggested, to confirm the reconstruction, we have to show how a certain word made its way “abroad.” If we were dealing with an extremely ancient noun common to both Indo-European and Semitic, we would have most probably discovered its traces somewhere between the Middle East and Germania, but as noted, Latin lacks it and so does Greek.

In 1917, 170 years after Junius’s death, Albert Carnoy, a distinguished Belgian scholar, whose ideas, however ingenious and brilliant, should be taken with a sizable grain of salt, offered, though hesitatingly, another Hebrew derivation of bar, namely from barzel “iron,” to which he also traced Engl. brass and Latin ferrum “iron.” The triad barzel / ferrum / brass occurs elsewhere in the scholarly literature, but this is no place to discuss its merits; each of the three words presents a huge problem. Even if it were possible to prove their affinity, the way from them to bar in Romance would be hard to trace. Italian and Spanish have barra, and this is the form posited for its Medieval Latin source. Works on the ties between Semitic and Indo-European keep proliferating. Bar does not turn up in those I have consulted. I conclude that nowadays the Hebrew hypothesis is dead, though it may be that today no one remembers it! Etymologists tend to have a short memory. Some people in the first half of the nineteenth century tried to connect bar with Old English beorgan “to save; guard, defend” (compare German bergen) and return the word to the Germanic stock. This is a wild guess.

Behind bars.

Behind bars. We can now return to Ireland, Wales, and Brittany. At one time, it became commonplace to derive the unattested Latin form barra, the alleged etymon of Germanic bar (as in English) and Barre “sandbank” ~ Barren “metals rod” (as in German), to Celtic. Indeed, a similar form (barr) exists in Irish and Welsh, but in both it means “summit, peak.” Breton barri “branch” must have developed from “peak.” The semantic gap between “summit, peak” or even “bushy end” and “rod; barrier” has never been accounted for, and the former enthusiasm for the Celtic trace, though still smoldering, has waned considerably. We may note that this enthusiasm was tempered even in the beginning. In the first edition of Skeat’s dictionary (1882), the Celtic connection is given as fairly certain (the same in the most often used dictionaries by Skeat’s English predecessors Müller and Wedgwood), but in the last, fourth edition of his great work (1910) only a question mark remained of it. The old and more cautious Skeat followed the OED; James Murray, the OED’s first editor, called the Celtic etymology discredited on semantic grounds. He may have come to this conclusion himself, or he may have consulted Professor John Rhys, his usual authority on things Celtic. The OED’s popular descendant, The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, whose format (one volume) precluded it from going into the discussion of controversial hypotheses, stated curtly that the unattested Romance word barra is of unknown origin.

It certainly is. However, it must have come from somewhere. Harri Meier, the author of many contested Romance etymologies, compared barra with Latin vittis “hatband.” His reconstruction is too involved to do it justice in this post, but the interchange between initial b- and v- in Latin is common, and barra has often been compared with names like Varro. One finds a more interesting conjecture in a 1921 article by Alois Walde, an eminent Austrian scholar, the author of a Latin etymological dictionary and a monumental dictionary of Indo-European. If I understand him correctly, he believed that barra was a regular Indo-European word related to Latin forus “gangway, passage”; its better-known cognates are foris “door” and forum. (It seems that wherever I go, doors and thresholds are always with me: see the blog post of 11 February this year.) He thought of the ancient (unattested) word bhoros “wood cut into planks or boards.” Both forus and barra would have emerged as its offspring. Despite Walde’s great name, his idea seems to be lost.

A Bar Exam

A Bar Exam It is unfortunate that most of our popular and semi-popular dictionaries can rarely sift the multiple guesses of which the “art and science” of etymology is so full. The public wants easy answers to difficult questions, and it loves “fun,” a legitimate wish, for everybody wants to be entertained. No doubt, the origin of cat’s pyjamas is more exciting than a possible Indo-European etymon of bar. The market can sustain with utmost difficulty the likes of Feist’s etymological dictionary of Gothic, von Wartburg’s multivolume dictionary of French, or the excellent etymological dictionary of Old High German, which now, after several decades of highly professional labor, has reached its middle. Funding agencies divide the number of dollars required for the completion of such projects by the number of words to be included, refer to the needs of the ever-hungry group known as taxpayers, and shake their heads, while commercial publishers bring out books to sell them. In the area of etymological apparel, cat’s pyjamas are doomed to remain in fashion. As a result, even such a skimpy essay as the present one is hard to come by. One ends up with a shelf of reference books that list a few cognates and conclude the entry with the statement “Origin unknown.” At present, I’ll leave our correspondent with a welter of conflicting ideas (Hebrew: most probably wrong), (Celtic: extremely doubtful), Indo-European (untested) — that is, “none the wiser,” as I warned him at the beginning of the post.

It remains for me to say that the earliest recorded sense of Engl. bar is “a rod of metal or wood for fastening a gate.” In every other context (I would like to say “bar one,” but no, everywhere), whether in a court of justice, an inn, or in a drinking establishment, the word refers to the counter. Some of the words reminding us of bar are indeed related (for instance, barrier). Barricade, barrack, and especially barrel are worthy of a closer look. Perhaps the most curious one is the verb embarrass, an extension of embar “to enclose within bars,” hence “hamper; perplex,” a seventeenth-century borrowing from French.

Image credits: (1) Jaguar Behind Cage Bars. © Auke Holwerda via iStock. (2) Fans at the pub. © Deklofenak via iStock.

The post An embarrassment of riches appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers