Oxford University Press's Blog, page 675

April 20, 2015

Autonomy: the Holy Grail

When within the European Union the Lisbon Treaty was elaborated, the negotiators easily reached agreement on subjecting the EU to the constraints of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). It seemed to be an anomaly that all the Member States should be subject to the review power of the Strasbourg Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) while the EU itself was exempt from that control procedure. Accordingly, Article 6(2) of the Treaty on the European Union (TEU) states in categorical terms that “the Union shall accede” to the ECHR. Coordination with the ECHR was necessary for that purpose since originally provision was made only for States as contracting parties. This obstacle was overcome in 2010 by the entry into force of Protocol No. 14 to the ECHR, which cleared the way for the EU’s participation in the Strasbourg system.

The further steps were at first deemed to be just a matter of juridical routine. A draft agreement was adopted in 2013 that seemed to meet with no serious objections. However, the opinion delivered by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) on 18 December 2014 declaring the incompatibility of that agreement with the requirements under the integration treaties came as a surprise, even as a shock to most observers. It may have brought the project to the end of the road. Essentially, the CJEU found that the draft agreement did not sufficiently respect the autonomy of the EU, permitting interferences of the ECtHR with the exclusive competences of its parent body in Luxembourg. No substantive criticisms were raised, understandably so since Article 6(2) TEU enjoins the EU to adhere to the ECHR.

A basic misconception underlies the opinion of the Court of Justice as well as the views of its Advocate-General. Both assess the institutional linkage from the vantage point of the EU. Although conceding in principle that as a treaty party the EU must accept all the obligations deriving from the European Convention on Human Rights, they hold that in integrating the ECHR into the legal system of the EU, making it an integral part of that latter system with all of its procedural articulations, the CJEU holds a monopoly of authoritative interpretation of the ECHR in relationships among EU member states. This approach overlooks the elementary rule of general international law that the different methods of domestic implementation of an international treaty may not change the substance of that treaty. Primarily, a treaty concluded by the EU remains an international instrument with a binding effect under general international law. A State cannot escape from the clauses of a treaty which it has accepted by invoking its sovereignty, nor can the EU arrogate to itself special rights because it is an entity under international law with specific characteristics. The EU is of course not a State, but under no circumstances can it claim more rights than a State.

The opinion of the Court of Justice remains consistently within this ill-defined conceptual framework. Reference to the basic philosophy of the EU that it has arisen as “a new legal order” (para. 157) is irrelevant regarding its status under general international law. Likewise, when the CJEU emphasizes that the protection of fundamental rights within the EU must be ensured “within the structure and objectives of the EU” (para. 170), it comes close to denying the gist of the European Convention on Human Rights if that proposition is applied to the ECHR as well. The observer is reminded of the attempts by the former socialist countries to adapt the interpretation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights to the essential features of a socialist State, thereby emasculating the Covenant of its essential characteristics of democratic freedom and equality. The autonomy which the EU enjoys does not lift it up in its external relations to a higher level than the other States parties to the ECHR.

Council of Europe member states, as of 2009. Image by Hayden120 and NuclearVacuum. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Council of Europe member states, as of 2009. Image by Hayden120 and NuclearVacuum. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.A particularly disturbing element of the opinion is the passages where the Court of Justice unhesitatingly affirms that the principle of mutual trust, anchored in the Treaties of the European Union (TFEU), must prevail over the protective function assigned to the Strasbourg Court of Human Rights. It is undeniable, as the jurisprudence of the ECtHR has shown, that even EU members may occasionally or even structurally breach their commitments under the European Convention on Human Rights. By affirming stubbornly that in the area of mutual recognition of national decisions the ECtHR should be prevented from exercising its powers the CJEU seeks to apply its doctrine of primacy of integration law inappropriately, denying the EU’s position of subordination to the ECHR and inflicting at the same time a harsh blow on the role of the ECtHR as the ultimate guardian of human rights in the whole of Europe.

The same criticisms is deserved by the holding of the Court of Justice that the accession agreement must exclude any recourse to the Strasbourg Court where no prior involvement of the EU courts was possible because of the restriction of their powers in the field of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). It is one thing for the EU treaties to exclude its courts from reviewing acts of the CFSP on account of their inter-governmental nature. However, the wish to discard the ECtHR in instances where plausibly an allegation of individual injury can be made amounts to a head-on attack on the supervisory role of the ECtHR which the Council of Europe should not accept.

In sum, an ambiguous picture emerges. On the one hand, in the past the Court of Justice of the European Union has consistently followed the jurisprudence of the Strasbourg Court of Human Rights as far as the definition and the meaning of human rights is concerned. Article 52(3) of the European Charter has enjoined the CJEU to continue on that path regarding the rights under the Charter. On the other hand, in Kadi (judgments of 3 September 2008 and 18 July 2013) the CJEU has commenced a line of setting apart the European system of protection of human rights from the framework of general international law, where the UN Security Council plays a pivotal role. With some kind of righteous arrogance, the CJEU claimed a position of superiority without sufficiently explaining its position. Now, by invoking the argument of autonomy, the CJEU claims a position of superiority in respect of the ECtHR.

The Court of Justice must take care to recognize the limits of its jurisdiction. It is an error to believe that the autonomy of the EU elevates the European entity to an unparalleled higher level of juridical status. Autonomy should not be mistaken for the dignity deserved by a holy grail. It must be admitted, though, that the CJEU is not to blame alone. Criticism is also deserved by the ambiguous drafting of the instruments governing the EU’s accession to the European Convention on Human Rights where autonomy is given such a prominent role. However, it remains a fundamental error of the CJEU and its Advocate-General not to have distinguished clearly enough the two functions of the ECHR within the framework of the EU legal order. On the one hand, by the act of accession, the ECHR will become an integral component part of that legal order. On the other hand, however, this does not change the basic fact that the EU, as a contracting party to the ECHR, will become subject to the system of the ECHR with all of its implications, where its internal complexities must be disregarded to the greatest extent possible.

Headline image credit: Courtroom of European Court of Human Rights. Photo by Adrian Grycuk. CC BY-SA 3.0 PL via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Autonomy: the Holy Grail appeared first on OUPblog.

Earth Day: A reading list

To celebrate Earth Day on 22 April, we have created a reading list of books, journals, and online resources that explore environmental protection, environmental ethics, and other environmental sciences. Earth Day was first celebrated in 1970 in the United States. Since then, it has grown to include more than 192 countries and the Earth Day Network coordinate global events that demonstrate support for environmental protection. If you think we have missed any books, journals, or online resources in our reading list, please do let us know in the comments below.

Only One Chance, by Philippe Grandjean

The book is a powerful call to action against chemical pollution and makes a strong case for how pollution harms the developing brain. The author goes into detail about the various chemicals including mercury, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), arsenic, and certain pesticides that we have evidence of polluting our brains. He goes on to discuss various development issues that may be caused by chemical poisoning including mental retardation, cerebral palsy, autism, ADHD, and learning disabilities.

From Field to Fork, by Paul B. Thompson

With over 30 years of experience, Thompson tackles the social injustices in the food industry including workers and farmer’s rights, animal production, health issues caused by GMO-based foods, and more. This is a great book for those who have a general idea of food issues but would like to delve deeper into the matter.

A Perfect Moral Storm, by Stephen M. Gardiner

Stephen Gardiner views the growing issue of climate change through an ethical lens, considering it an ethical failure. He discusses unethical dilemmas including how first world countries tend to pass the cost of climate change to poorer countries. He also remarks on how the current generation of citizens would rather pass this problem to future generations, rather than dealing with it now.

The Oxford Handbook on Climate Change and Society, edited by John S. Dryzek, Richard B. Norgaard, and David Schlosberg

This major work covers various topics on the world’s growing concern on climate change and how societies and government should respond. A wide range of topics are discussed including the history of the issues, social and political reception of climate science, the denial of that science by individuals and organized interests, the nature of the social disruptions caused by climate change, and more.

A Philosophy of Gardens, by David E. Cooper

This book discusses the history of gardening through ancient times to present, covering both Western and Eastern civilizations. Cooper discusses how garden appreciation is a distinct type of phenomenon differing from aesthetic or art appreciation. Various garden practices and methods are discussed, and Cooper explains how these meditative activities can lead to a better sense of life. Reading this may give you a better perspective of your own garden.

Environmental Ethics, Second Edition, edited by David Schmidtz and Elizabeth Willott

This revised textbook on environmental ethics has new chapters on climate change, technology, and urban management. There is also updated content on human relationship with the wilderness and on practical issues such as GMO-based foods. This is a great book for those who want to have a general foundation and understanding of ethics and moral philosophy as applied to the environment.

‘The Future of Ecology and the Ecology of the Future’, from Foundations of Environmental Sustainability, edited by Larry Rockwood, Ronald Stewart, and Thomas Dietz

This book provides a unique view of the development of environmental policy in the US and abroad, particularly conservation policy in Africa and Asia. This chapter on ecology discusses advances in ecology including the theory that ecology systems are not steady state, but that time and space vary within. The chapter concludes with a section on what issues need to be addressed in ecology, including fashionability, dynamic nature, theory, valid experiments and more.

‘Future climate change’, from Climate: A Very Short Introduction , by Mark Maslin

, by Mark Maslin

This chapter discusses why changes in the current climate system will lead to more unpredictable weather patterns. The chapter starts off with evidence for human induced climate change, providing data from various global groups including the IPCC. It goes on to discuss what safe level-changes are and how global energy and food demands will impact our climate system.

Effects of Regional Climate Warming on Phenology of Butterflies in Boreal Forests in Manitoba, Canada in Environmental Entomology, by A. R. Westwood and D. Blair

This article focuses on the Boreal Forest ecosystem and how regional climate changes affect native butterflies. Over 19 species were tested, and temperature and flight periods were observed between the Autumn/Winter and Spring/Summer seasons.

Featured image credit: Forest Trees and Light, by Republica. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay

The post Earth Day: A reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

April 19, 2015

Crazy Horse and Custer

Fifteen years ago, not long after publishing Anthology of Modern American Poetry with Oxford, I began to receive the typical mix of complimentary and complaining letters. In the latter category, faculty members wanted to know why a favorite poem or poet was left out and some poets who were not included wrote pointed letters to let me know they weren’t happy with the fact. But one poet, William Heyen, took a different approach. He sent me a large (actually very large) box of his books, chapbooks, and broadsides and said, “Judge for yourself whether I should have been in your collection.” I suppose I could have just set the unexpected gift aside, but I felt I had been given both an intellectual challenge and an ethical burden. Meanwhile, from time to time, smaller packages from Bill arrived, updating me on his publications. I sent a brief thank you note, saying I was eager to read what he had sent. People in the book world learn to do this promptly. If you wait too long, people expect you to comment on their book.

Anyway, I began to read the collected works of William Heyen. I had read those of his poems that were regularly anthologized but had never sat down with his books. Heyen writes regularly about the Holocaust. Years later, when I began teaching a seminar on Holocaust poetry, I assigned his book, Shoah Train. And I let the question of whether I ought to have included him in the anthology play lightly at the edge of my thoughts. But it wasn’t a pressing question until I read Crazy Horse in Stillness, his 464-poem “dialogue” between the great Ogalala Lakota war chief Crazy Horse and General George Armstrong Custer, all leading up to the June 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn, when Custer and all the troops under his command were defeated and killed.

Successful poems about Native American history and culture by non-Indian writers are few and far between. Unlike minorities that have regular and widespread contact with majority America, Indians remain partly separate. Unlike the very rich and powerful traditions of Native American poems, a tradition stretching back into the 19th century, I am aware of only a tiny handful of poems by non-Indians that I consider first rate. But suddenly I was reading a tour-de-force poem sequence that showed intricate knowledge of Indian culture and was both incredibly inventive as literature and forceful as political statement. The first poem below is from Crazy Horse’s perspective, the second from Custer’s. “One World” embodies Native American myth and spirituality, along with the sense of individual quest, whereas “Treaty” is a testament to the cold exercise of the power of the whites:

One World

At a small pond ringed by willows and twilight,

Crazy Horse, who had not slept for how many days,

stared into his face filled with frogspawn,

with stars. So that was where the dead lived,

& waited, there behind his eyes. He’d never again

worry where he would spend eternity, this now, as long

as one Lakota lived to contain the world…

His horse snuffled from its tether in the willows—

they’d return to the village, & fall awake,

& dream the stars in the pond, the spawn in the stars.

Treaty

Said Custer, Here’s how it’s going down:

we’ll ration water to the fish first come,

first served; grass o the buffalo by rank;

sky to the hawks one windgust at a time.

Keep your people quiet and in single file.

For any trouble, you’ll sacrifice a child

a minute for as many of your moons

as ever bled your dirty women. Keep

questions to yourself, and call me friend.

Crazy Horse in Stillness is a completely unique and compelling book, but it is also very much a single coherent work. How could I excerpt from 464 poems so as to do justice to the whole project? I really had no answer. But then I wasn’t faced with a real challenge to do so, so the question only troubled me slightly. Indeed, I mostly decided it couldn’t be done. But in time, Oxford invited me to do a new, expanded edition of the anthology. Now Crazy Horse and Custer were priorities.

Years earlier, I had confronted the need to choose selections from Ezra Pound’s Cantos. Most anthologists simply look for what they think are the best poems in the book. But the goal I set myself instead was to pick a group of Pound’s Cantos that I felt represented the spine of the book. I wanted what amounted to a miniature, condensed version of Pound’s masterwork. Could I do the same with Crazy Horse in Stillness?

It was not just a question of what to include but also of what to exclude. I decided that the poems I selected had both to embody the most essential elements of the confrontation between the two men and their individual inner worlds. That meant leaving out many of the threads woven into the book, including observations in the voice of Custer’s wife. And I wanted the selection to cohere as a narrative, to tell the story in miniature. Like Heyen’s book, the narrative based on a subset of poems had to drive inexorably toward the battle and Custer’s death but also leap forward and harvest the confrontation’s long-term spiritual and historical implications. For we know that the Battle of the Little Bighorn, in fact, heralded the defeat of the Plains tribes and the possession of their homeland by the expansion of white culture:

Disequilibrium

When only a thousand buffalo were left alive on the plains,

one old bull hid inside a tree, crossed its growth rings

inward toward dead heartwood where it somehow knew

it would have to live. Each year the tree added a ring.

& each year the buffalo receded further toward its future.

Meanwhile, from beyond the riverbank where the tree lived,

soldiers were galloping toward him with politicians

& lawyers & dozers & cement trucks on their shoulders.

Thinking about the project of excerpting poems took many months, but eventually I ended up with a 17-poem sequence that I felt made a compelling mini-narrative, a representation of the much longer book. I sent it off to Bill Heyen with some trepidation, since many poets would not appreciate this sort of intervention, instead finding it presumptuous. But Bill liked it and felt it condensed the book’s aims well. He only asked that I add one more poem, “The Tooth,” which I of course agreed to do.

Poems from Crazy Horse in Stillness, copyright 1996 by William Heyen, are reprinted here with the author’s permission.

Image Credit: “Crazy Horse” by Great Beyond. CC BY NC-SA via Flickr.

The post Crazy Horse and Custer appeared first on OUPblog.

A woman’s journey in Kashmiri politics

Nyla Ali Khan’s recent book The Life of a Kashmiri Woman: Dialectic of Resistance and Accommodation, though primarily a biography of her grandmother Akbar Jehan, promises to be much more than that. It is also a narration of the story of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, the charismatic political leader who is still recognized as the greatest political leader that Kashmir ever produced. It is also a depiction of Kashmiri identity politics as it evolved and took shape during various phases. However, most significantly, it is a feminist narrative of gender dimensions of Kashmiri politics and an account of women’s place and role in it.

The central character of the book is Akbar Jehan, whose life is intrinsically linked with the political trajectory of Kashmir. Hailing from an aristocratic background, she left the life of protection and comfort to marry Sheikh Abdullah, who was pursuing a political life fraught with challenges. Akbar Jehan, as the book informs us, remained committed to her husband’s ideology and made his political struggle her own, standing by him through the turbulent years of the twentieth century. In 1947 when the state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) faced a tribal attack and the National Conference organized a local militia, Akbar Jehan led the Women’s Self Defence Corps, which provided military training to Kashmiri women. Later, she helped in the task of repatriation and rehabilitation of abducted young women. In 1953, when Sheikh Abdullah was incarcerated, she took it upon herself the task to singlehandedly raise her young family while at the same time taking over some of duties of leadership from her husband. This was especially difficult, given that her relatives and friends had abandoned her by then. Isolated due to the hostile attitude of the political authority in Jammu and Kashmir, she was also to face the “conspiracy case” against her husband, in which the Sheikh was accused of being the Pakistani agent in receipt of huge sum of money from the government of Pakistan. Akbar Jehan was accused of being the conduit through which the money exchanged hands. (The case was later withdrawn.)

Rather than serving as a mere shadow of her husband, Akbar Jehan emerged as the symbol of continuity of Sheikh’s politics and led his followers while he was jailed — organizing protest demonstrations and leading processions. As a result of her years of political experience, she had the opportunity to prove her own mantle as a Parliamentarian following her election in 1977. Even in the midst of party turmoil, which involved the fall of her son Farooq Abdullah from power, Jehan managed to win reelection in 1984.

The author, Nyla Ali Khan. Photo by Nyla Ali Khan. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The author, Nyla Ali Khan. Photo by Nyla Ali Khan. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. In a world of male dominated politics with few women role models to emulate, Akbar Jehan’s journey remains important. Kashmiri politics has generally remained bereft of women leaders. It is only recently that women such as Mehbooba Mufti have had some presence, following the path first tread by Akbar Jehan.

However, it was tragic that, following the Sheikh’s death in 1982, she had to witness the decline of the political edifice that he had built. Throughout the period of militancy, when many of the leaders of the National Conference left Kashmir for safer places, she continued to stay on, still acting as a rallying force for the party loyalists. But having witnessed the decimation of her husband’s political agenda as well as anger and hostility of the people, she died a sad woman.

By exploring the context of Akbar Jehan’s career, Khan has sought to represent the story of Kashmir’s politics from a gender perspective. It is a story of a woman located in the “rigidly entrenched gender hierarchy” who moves “beyond the pigeonholes that conventional narratives have constructed for women.” This narrative represents the immense potential that Kashmiri women have vis-a-vis the sphere of politics.

By bringing women to the center of Kashmir’s political discourse, Nyla has sought to question not merely the academic silence around the gender dimensions of Kashmir’s politics but has also sought to challenge the dominant paternalistic notions about the relationship between women and politics. Even when women are portrayed in academic work, their role as agents in their own rights can often go missing. In her story of Akbar Jehan, Khan reveals her agential role.

To do this, Khan follows an unconventional approach. Rather than dividing the life of Akbar Jehan between public and private, she sees one realm as the extension of the other. Finding an overlap between Jehan’s familial and political roles, Khan notes that there was no part of her personal life which was not political. From her decision to marry Sheikh Abdullah, to her struggle in bringing up the family in the absence of her husband in the situation of hostility and isolation, to her decision to continue staying in Kashmir during the period militancy — all these were overtly political acts. The “personal is political” is what was inscribed in the life story of Akbar Jehan.

Writing the story of politics from the perspective of woman is not easy. There is a paucity of documented material on women and the role that they play in society and politics. As Khan notes, there is a general reluctance to recognize the progressive role of women in the larger political context of Kashmir — hence no documentation of their role. Reconstructing the story therefore takes lot of research. There are many gaps, and one gets the feeling that there are various dimensions of Akbar Jehan’s life which could have provided more depth to her story. It would for instance have been interesting to know the critical side of Akbar Jehan and her personal response if not towards her husband’s political decisions, at least toward her son Farooq Abdullah’s follies.

That said the book is a very important contribution to the literature on Kashmir’s politics. It is one of those rare personal accounts written with empathy and academic dexterity.

Featured Image: Shikara, Dal Lake. © MaresaSmith via iStock.

The post A woman’s journey in Kashmiri politics appeared first on OUPblog.

Learning country music in the digital age

Recently reading through the Notes and Discographies section of Greil Marcus’s book Mystery Train (first published in 1975), I was struck by Marcus’s meticulousness when it came to recommending records. When remarking on “Rock A Little Baby,” a 1958 single by rock pioneer Harmonica Frank Floyd, Marcus is kind enough to observe in a footnote that the album can be ordered by mail from Down Home Music, and goes on to provide an address for the company and even a telephone number.

Instead of all that, I pull up Google, type “Harmonica Frank Floyd Little Baby,” find the song on YouTube, and – voilà! – thirty seconds later, I am listening to Harmonica Frank. For us denizens of the digital age, there’s obviously no longer any reason to shell out a dozen bucks and wait four weeks to understand what Greil means when he calls “Rock A Little Baby” a “dazzling 1958 single” when the answer is at our fingertips. These days, we can just find the song and press play.

At this point in our media-saturated existence, this seems like nothing special; we pretty much take the instant gratification of the Internet as a given. Haven’t heard that song before? No problem. The Internet will find it. Any unfamiliar morsel of culture that someone pushes your way during a dinner conversation, you can sneak off to the bathroom, whip out the ol’ trusty smartphone, and figure out what they’re talking about in seconds.

The benefit of this approach to digitized culture that it took some time for me to see, though, was how it might help me in exploring entire discographies of musical artists, or even subgenres and genres. For instance, with the help of the Internet, it becomes easy to spend a day listening to the Rolling Stones from their 1964 self-titled debut all the way through to 1971’s Exile on Main Street. (I did this, and it was awesome.) What got me thinking, though, was the kind of deep dive into the entire genre of country music I could do with help of The Encyclopedia of Country Music, Second Edition, a copy of which sat on my desk at work.

It didn’t take long before I decided to start in on the daunting task of “learning,” or, well, at least getting to know, country music. For those who are not familiar with the Encyclopedia, it is no light read, containing over 1,200 entries on country artists, producers, businesspeople, TV shows, organizations, subgenres, and just about everything relating to country music that you can imagine. In short, it is an exhaustive resource, covering everything from Pure Prairie League to the Louisiana Hayride to forgotten A&R men of the 1930s.

Picking my way through the book one entry at time, I selected a song or two from each musical artist or instrumentalist and – if I could locate a verifiable version on Spotify – I would add the songs to a growing playlist. As I worked my way from A to Z in the Encyclopedia, the playlist, which I would listen to on random as I assembled it, ballooned from the manageable size of a few hundred songs to the rather alarming size of nearly 1,500 songs, totaling nearly 75 hours of music, touching on everything from conjunto to Patsy Cline.

But the most shocking part of it all, more so than the sheer lunacy of the project, was how much of this music the Internet seemed to have available. It became almost a game to see what musical artist recognized by the Encyclopedia couldn’t be located on at least Spotify. (I found recordings every artist mentioned at least somewhere on the Internet.) I would hold my breath while searching for Narmour & Smith – “one of the most popular instrumental duos on records in the late 1920s.” No way they would be on Spotify, right? But no: Spotify helpfully had the entirety of Narmour & Smith Vol. 1: Complete Recorded Works (1928-1930). How about the 1920s gospel group Smith’s Sacred Singers, which “never toured or pursued extensive radio work – and personnel typically shifted from [recording] session to session”? Oh, but of course, there is an entire album of songs available, including the group’s 1926 debut single “Pictures from Life’s Other Side.”

Today, you don’t need to be a record collector to follow along – no need to reach out to Down Home Music for that long-lost single – it’s probably somewhere on Spotify, or elsewhere on the Internet. For whether it’s Frank Blevins and his Tarheel Rattlers or The Pickard Family, digging deep in musical history isn’t nearly so hard as it used to be. You want to learn a genre? It’s easier than you might think. No need to pick through bargain bins of dusty records – a Spotify playlist, a trustworthy guide (in this case, the Encyclopedia!), and a certain sense of self-punishment will suffice.

Featured image credit: Grand Ole Opry performers at Carnegie Hall. Photo by William P. Gottlieb. Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Learning country music in the digital age appeared first on OUPblog.

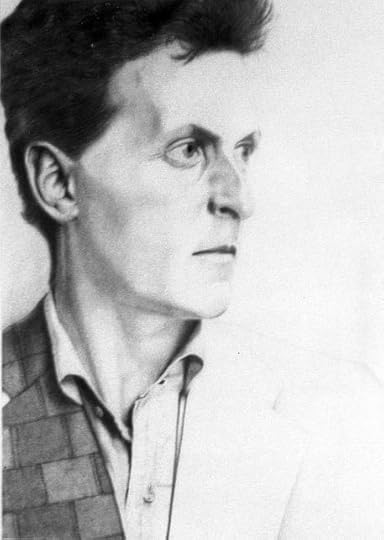

Wittgenstein and natural religion

In the philosophy of religion ‘Wittgensteinianism’ is a distinctive position whose outlines are more or less unanimously agreed by both its defenders and detractors.

By invoking a variety of concepts to which Wittgenstein gave currency – language games, forms of life, groundless believing, depth grammar, world pictures – the defenders aim to defuse rationalistic criticisms of religion by showing them to be, in the strict sense, impertinent.

In the light of these very same concepts, however, the detractors claim that ‘religion’ is being isolated from intellectual inquiry and rendered immune to critical scrutiny.

The dispute began in 1962 at a conference in Princeton Theological Seminary when John Hick raised objections to a line of thought about religious belief that Norman Malcolm, inspired by Wittgenstein, seemed to be adopting.

The most prominent ‘cold warriors’ of this particular debate were Kai Nielsen and the late D Z Phillips, who, astonishingly, kept it going for nearly forty years. A great many other philosophers participated, mostly on one side or other of the battle line, though occasionally in the role of mediators seeking to find middle ground.

Like so many philosophical disputes, this one was never really resolved, and for the most part has burnt itself out.

“Should we conclude from this that Wittgenstein’s philosophy has no light to shed on religion?”

In careful retrospect, however, what is striking is just what a very tenuous connection it all had with Wittgenstein’s philosophical writings. It is widely acknowledged that the Philosophical Investigations have nothing to say about religion, On Certainty almost nothing, and the Tractatus just a few propositions towards the end that touch on ethics, mysticism and life after death.

Quite a lot has been made of the remarks about religion, and Christianity in particular, that can be found in Culture and Value. But these were collected and published by Von Wright, not Wittgenstein.

Maurice O’Connor Drury’s ‘recollections’ of conversations about religion with Wittgenstein are another source to which philosophers of religion have turned. Yet Drury tells us that these conversations followed Wittgenstein’s explicit refusal to ‘talk philosophy’.

In addition to these observations, it is salutary to note that the ‘key’ concepts of language games, forms of life, groundless belief, and so on, occur relatively rarely in the philosophical works. ‘Language games’ for instance, appears in only 50 of the 673 paragraphs that constitute Part One of the Investigations, while ‘form of life’ is used just five times in the entire work.

Drawing of Ludwig Wittgenstein by Christiaan Tonnis. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Drawing of Ludwig Wittgenstein by Christiaan Tonnis. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. In short, the superstructure of ‘Wittgensteinianism’ in philosophy of religion rests upon a very small foundation indeed.

Should we conclude from this that Wittgenstein’s philosophy has no light to shed on religion? This is a plausible conclusion to reach, but there is reason to think that it would be a little hasty.

Wittgenstein was undoubtedly interested in religion. He evidently read William James’s Gifford Lectures on The Varieties of Religious Experience with close attention. He was suitably incensed by the misguided conception of religion that he found at work in J G Frazer’s Golden Bough. And the remarks he recorded that found their way into Culture and Value show a similar concern with a certain sort of error.

Eighteenth century philosophers, including Hume and Kant, would have identified the kind of error in question as a failure to distinguish between ‘true’ and ‘false’ religion, the sort of error that people make when they mistake lust for love, or flattery for praise.

Hume thinks that ‘true religion’ is neither superstition nor dogmatism, though religious believers are no less likely to make this misidentification as the critics of religion (of which he was one). True religion for Kant (as for Spinoza) is to be sharply distinguished from all the ecclesiastical trappings by which it is so often surrounded.

William James is equally anxious to discount the theological and philosophical constructs that pass for religion – ‘an absolutely worthless invention of the scholarly mind’ he calls them. It is this anxiety with which Wittgenstein is profoundly sympathetic, and his sympathy shows itself in many of the passing remarks that have so impressed some philosophers.

But what does it have to do with his philosophy properly so called?

The answer, I think, is this. We can abandon the whole conceptual panoply of language games, forms of life, depth grammar and the like. It is Wittgenstein’s method of philosophical investigation that promises to throw new, and critical, light on the nature and value of religion as a human phenomenon.

There is a lot to be learned if we reorient the subject away from philosophical theology, towards the philosophy of ‘true religion’, and employ Wittgenstein’s philosophical method to explore once more some of the themes that, in some of their works, occupied Spinoza, Hume, Smith, Kant, Schleiermacher and Mill.

Featured image credit: Farm Garden with Crucifix by Gustav Klimt (1912). Public domain via WikiArt.

The post Wittgenstein and natural religion appeared first on OUPblog.

April 18, 2015

Getting to know Brian Muir

From time to time, we try to give you a glimpse into our offices around the globe. This week, we are excited to bring you an interview with Brian Muir, an Online Marketing Assistant on our Direct Marketing team in New York. Brian has been working at the Oxford University Press since March 2014.

What is the most important lesson you learned during your first year on the job?

Sometimes you learn more from your failures than from your successes (not that I’ve made any horrible mistakes).

What is your typical day like at OUP?

I spend about half of my time working on various email campaigns, which include e-newsletters, conference emails, and white sale promotions. The other half of my work is on the website. I help with general upkeep, build landing pages for sales, and work on special projects like the WWI Centennial page.

What’s the most enjoyable part of your day?

I like meetings in which we “talk shop” about our overall marketing strategy. We’re always looking for ways to improve our email campaigns, as well as the OUP site itself, so it’s nice when the whole team sets some time aside to just brainstorm and share ideas.

What’s the least enjoyable?

Dealing with the inevitable anxiety that comes moments before pushing something live on the Internet.

Photo by Aparna Rishi for Oxford University Press.

Photo by Aparna Rishi for Oxford University Press. What is the strangest thing currently on or in your desk?

A postcard depicting a bunch of anthropomorphic lobsters hanging out in a seafood restaurant. My mom gave it to me.

What are you reading right now?

Playing for Thrills by Wang Shuo. It’s a Chinese noir from the 1980s. I bought it for two dollars at a used book fair and so far it’s pretty good.

What’s your favorite book?

Gould’s Book of Fish by Richard Flanagan. So weird and so fun.

If you didn’t work in publishing, what would you be doing?

I live around the corner from a cute little cheese shop. If I didn’t work in publishing, I’d probably try to get a job there, maybe working the cash register or something. There’s something romantic about having your life confined to a one-block radius.

Tell us about one of your proudest moments at work.

During one of my first days, my supervisor approached me with a printed email I had heavily marked up. She said, “Did you do this? If I could give you a gold star for effort, I would.” I don’t think I’ll ever outgrow the excitement that comes from earning a gold star.

If you were stranded on a desert island, what three items would you take with you?

Plenty of canned goods (for sustenance), a good book (for entertainment), and a cellphone containing emergency contacts (so I could leave whenever).

What drew you to work for OUP in the first place? What do you think about that now?

I was an English major and was interested in publishing. Oxford seemed like an especially great place to work, since you learn something new every day. Sometimes I think working at OUP is like going to grad school for free.

What is in your desk drawer?

Spiderman fruit snacks and a broken desk fan.

Most obscure talent or hobby?

I’m pretty good at impressions. Somebody recently told me that I do a pretty mean Truman Capote. Does that count?

Headline image credit: Window at the Oxford University Press New York office. Photo by Sara Levine for OUP.

The post Getting to know Brian Muir appeared first on OUPblog.

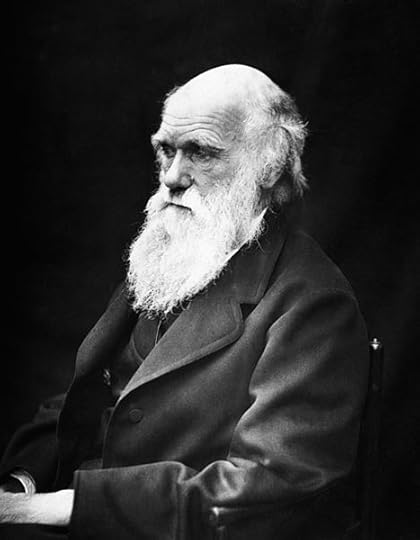

Darwin’s “gastric flatus”

When Charles Darwin died at age 73 on this day 133 years ago, his physicians decided that he had succumbed to “degeneration of the heart and greater vessels,” a disorder we now call “generalized arteriosclerosis.” Few would argue with this diagnosis, given Darwin’s failing memory, and his recurrent episodes of “swimming of the head,” “pain in the heart”, and “irregular pulse” during the decade or so before he died.

There is, however, considerable disagreement as to the cause of the “gastric flatus” that plagued him for nearly thirty years after his return to England from his voyage aboard the HMS Beagle. That mysterious illness consisted of repeated sudden attacks of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and retching, two to three hours after eating. During the worst periods, he vomited after nearly every meal, sometimes for years on end. And yet, because he seldom regurgitated food, “only acid & morbid secretion,” his vomiting did not interfere with his intake or digestion of food, his general nutritional status, or for that matter, his scientific productivity. After creating psychological havoc for three decades, the gastric disorder faded and then disappeared as mysteriously as it had arisen.

Darwin’s physicians were totally nonplussed by his gastric complaints. When they could find no evidence of organic mischief, they assured him that eventually he would recover. They told him he had “suppressed gout,” “an excess of gastric acid,” “inadequate amounts of gastric acid,” “mucous dyspepsia,” “an allergic reaction,” or “over-breathing,” for which they plied him with a host of treatments, none of which produced any lasting relief.

Charles Darwin. J. Cameron, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Charles Darwin. J. Cameron, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Many of Darwin’s friends and later would-be diagnosticians thought he was a hypochondriac. However, hypochondriacs typically are reluctant to acknowledge the role of psychological factors in causing their symptoms; misinterpret benign physical sensations as evidence of serious illness; tend to respond to reassurance with anger rather than relief; and are frequently functionally impaired to a severe degree by the disorder. Darwin exhibited none of these characteristics.

It has also been suggested that Darwin’s gastric disorder was the result of an infection called Chagas disease, which he contracted while exploring in the Pampas of Argentina. Suffice it to say that the character and course of his intestinal disorder (not the least of which was its mysterious, spontaneous resolution after rampaging for 30 years) is inconsistent with published descriptions of Chagas disease.

In the final analysis, of the myriad diagnosis offered to explain Darwin’s strange illness, only cyclic vomiting syndrome has characteristics consistent with the full spectrum of the great man’s gastric disorder. The syndrome, though little known, is currently being diagnosed with surprising frequency. It consists of recurrent episodes of nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain separated by asymptomatic periods. Migraine headaches and intense anxiety induced by the uncontrollable episodes of vomiting (both of which afflicted Darwin greatly) are common, as are cardiac arrhythmias and other neurological complaints (as, for example, numbness of the extremities and nervous tics, of which Darwin also complained).

If Darwin were alive today, he would be subjected to a host of examinations in an effort to diagnose his illness, all of which would likely prove to be negative. Having excluded all other diagnoses through such testing, the physician specializing in gastrointestinal disorders to whom Darwin would be referred, would eventually offer him a diagnosis of cyclic vomiting syndrome as reassurance that he was not alone in his suffering. Although that diagnosis has been consecrated by Rome III diagnostic criteria with its own symptom-based definition, it provides no insight into the disorder’s cause, the mechanisms by which it arises or is sustained, or an effective means of preventing or treating it. Like diagnoses such as irritable bowel syndrome, attention-deficit disorder, chronic hyperventilation syndrome, restless leg syndrome, sudden infant death syndrome, posttraumatic stress disorder, and many others given to patients today, cyclic vomiting syndrome does little more than paraphrase the complaints for which the patient seeks medical attention. Ultimately, it is no more enlightening or helpful in relieving the suffering of patients like Darwin than “excess gastric acid” or “suppressed gout” or “mucous dyspepsia” was over a century ago.

Feature Image: HMS Beagle. R. T. Pritchett, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Darwin’s “gastric flatus” appeared first on OUPblog.

A Jazz Appreciation Month Playlist

Established in 2001, Jazz Appreciation Month celebrates the rich history, present accolades, and future growth of jazz music. Spanning the blues, ragtime, dixieland, bebop, swing, soul, and instrumentals, there’s no surprise that jazz music has endured the test of time from its early origins amongst African-American slaves in the late 19th century to its growth today. Often characterized by improvisation, syncopation, and usually a regular or forceful rhythm, jazz is commonly played on brass and woodwind instruments, pianos, guitars and violins, sometimes accompanied by smooth melodic vocals. In celebration of Jazz Appreciation Month, we’ve compiled a list of timeless classic jazz songs for the enjoyment of aficionados and new listeners alike.

Dizzy Gillespie – “Salt Peanuts“ Billie Holiday – “Strange Fruit“ Mary Lou Williams – “Willow Weep For Me“ Bing Crosby – “White Christmas“ Frank Sinatra – “Fly Me to The Moon“ Ella Fitzgerald – “Dream a little dream of me“ Portrait of Dizzy Gillespie by Carl Van Vechten. Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Louis Armstrong

– “What a Wonderful World“

Herbie Hancock

– “Rockit“

John Coltrane

– “A Love Supreme“

Count Basie

– “One O’Clock Jump“

Benny Goodman

– “Sing Sing Sing“

Duke Ellington

– “It Don’t Mean A Thing“

Chet Baker

– “My Funny Valentine“

Nina Simone

– “Four Women“

Portrait of Dizzy Gillespie by Carl Van Vechten. Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Louis Armstrong

– “What a Wonderful World“

Herbie Hancock

– “Rockit“

John Coltrane

– “A Love Supreme“

Count Basie

– “One O’Clock Jump“

Benny Goodman

– “Sing Sing Sing“

Duke Ellington

– “It Don’t Mean A Thing“

Chet Baker

– “My Funny Valentine“

Nina Simone

– “Four Women“ Cover image: “Political cartoon by Clifford Berryman, published in the Washington Evening Star on 19 February 1922.” US National Archives and Records Administration. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post A Jazz Appreciation Month Playlist appeared first on OUPblog.

The long history of World War II

World War Two was the most devastating conflict in recorded human history. It was both global in extent and total in character. It has understandably left a long and dark shadow across the decades. Yet it is three generations since hostilities formally ended in 1945 and the conflict is now a lived memory for only a few. And this growing distance in time has allowed historians to think differently about how to describe it, how to explain its course, and what subjects to focus on when considering the wartime experience.

For instance, as World War Two recedes ever further into the past, even a question as basic as when it began and ended becomes less certain. Was it 1939 when the war in Europe began? Or the summer of 1941, with the beginning of Hitler’s war against the Soviet Union? Or did it become truly global when the Japanese brought the USA into the war at the end of 1941? And what of the long conflict in East Asia, beginning with the Japanese aggression in China in the early 1930s, ending with the triumph of the Chinese Communists in 1949?

From Japanese aggression against China in the early 1930s to the transition from World War to Cold War in the late 1940s, this timeline puts the events into their wider context and illustrates how they shaped the war.

Featured image credit: Near Algiers, “Torch” troops hit the beaches behind a large American flag “Left” hoping for the French Army not fire on it. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The long history of World War II appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers