Oxford University Press's Blog, page 679

April 8, 2015

Nasra Gathoni: an unsung hero

Recently, Research4Life and its partners, including Oxford University Press, have embarked on a campaign, “Unsung Heroes: Stories from the Library,” to raise awareness about the heroic and life-saving work being done by librarians in the developing world. In this new video, we follow a day in the life of Nasra Gathoni, Head Librarian at the Aga Khan University hospital in Kenya. The training she provides to doctors and nurses helps them locate the evidence-based information they need to improve healthcare for patients in their country.

Image Credit: “Bookshelves” by Ari Moore. CC by NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Nasra Gathoni: an unsung hero appeared first on OUPblog.

Are inheritances really that bad?

On the surface, inheritances are a source of moral repugnance. When we think of inheritances, we tend to think of families like the Rockefellers and Vanderbilts whose great fortunes were passed from one generation to the next. We also tend to think of “trust fund babies” – those rare individuals who have received enough money in inheritances or gifts (often in the form of a trust fund) so that they have no need to work over the course of their lifetime. As a result, many individuals feel that inheritances are morally wrong. Consequently, they advocate any measure that will eliminate inheritances and other wealth transfers, such as a confiscatory estate tax.

It is true that inheritances and gifts (collectively, “wealth transfers”) are incredibly unequal. Calculations from the Federal Reserve Board’s 2007 Survey of Consumer Finances show that only about a fifth of families had ever received a wealth transfer. Among recipients alone, only a very small percentage received substantial wealth transfers – 48 percent more than $100,000, 16 percent more than $500,000, 7.4 percent more than $1,000,000, and 4.2 percent more than $2,000,000. The top-one-percent received 35 percent of all wealth transfers in 2007, the top five percent received 61 percent, and the top 20 percent received 84 percent. The bottom 80 percent collected only 16 percent. The inequality of wealth transfers among recipients is about the same as that of household net worth.

It is also true that today’s rich have received more in the way of inheritances and gifts than the middle class or poor. This relation holds by income class, by wealth class, and by level of educational attainment (particularly between college graduates and all others). It is also the case that even among young people today the richest of these generally have richer parents and receive higher wealth transfers than those who are poorer. The evidence based on the Federal Reserve Board’s triennial survey, the Survey of Consumer Finances, over years 1989 to 2010 for the United States suggests that inheritances do not actually exacerbate household wealth inequality nor do they account for an increasingly larger share of household wealth. It is true that the average value of inheritances in constant dollars did increase by 24 percent, but this works out to a meager annual growth rate of 1.0 percent per year, less than the 1.7 percent per year annual growth in net worth, which occurred despite the steep recession of 2007 to 2010. As a result, wealth transfers as a proportion of current net worth actually dipped over these years from 29 to 26 percent. In sum, the evidence does not support the hypothesis that there has been an inheritance boom in the U.S. over the last few decades.

“It is also true that today’s rich have received more in the way of inheritances and gifts than the middle class or poor.”

Likewise, contrary to popular belief, the proportion of net worth of the very rich attributable to wealth transfers is surprisingly low—less than 20 percent—at least according to direct survey evidence. This figure compares to a ratio of about a third for the middle class. Moreover, the proportion of net worth attributable to wealth transfers fell very sharply between 1989 and 2010 for the very rich (the top income and wealth class) and for college graduates. In particular, the share among the top one percent of the wealth distribution fell from 23 percent in 1989 to 11 percent in 2010, or by 12 percentage points.

There are several possible explanations for these results. First, mortality rates among elderly people were declining, and, as a result, the number of bequests per year went down. Second, as people live longer, their medical expenses would likely increase as they age and, as a result, less money is transferred to children at time of death. Third, the share of estates dedicated to charitable contributions might be rising over time. This trend may be particularly true for the extremely rich. Likewise, the very rich while alive may be giving more money away to charitable organizations (think of the Bill Gates Foundation).

Despite seeming counter-intuitive, wealth transfers actually tend to be equalizing. Indeed, the addition of wealth transfers to other sources of household wealth had a sizeable effect on reducing the inequality of wealth. Richer households do receive greater inheritances and other wealth transfers than poorer ones. In particular, the proportion of households receiving a wealth transfer climbs sharply with both household income and wealth, as does the value of these transfers. However, as a proportion of their current wealth holdings, wealth transfers are actually greater for poorer households than richer ones. In other words, a relatively small transfer to poorer households counts more in percentage terms than a large gift to the rich. As a result, net worth excluding wealth transfers and wealth transfers themselves are negatively correlated.

Since wealth transfers and net worth have a negative correlation, adding transfers to net worth actually reduces overall wealth inequality. The calibration results indicate that eliminating inheritances either in full or in part actually increases overall wealth inequality.

In general wealth transfers flow from richer to poorer, satisfying the so called Pigou-Dalton principle. This is notably the case with gifts but also characterize most inheritances as well. This is also generally true when the very wealthy make a wealth transfer to their children. While the children are typically better off than others of their age group, still their parents are richer than they are and the transfers are made from richer to poorer. These transfers redistribute and reduce overall wealth inequality

In the case of gifts, transfers are almost always made from the more to the less wealthy, as the great majority of such transfers are from an older (and likely richer) to a younger (and likely poorer) person – in particular, from parent to child. Such inter-vivos transfers will reduce measured wealth inequality. Inheritances are similar, generally flowing from a (richer) parent to a (poorer) child. Of course, the most basic way in which inheritances reduce wealth inequality is through estate splitting. In a world without primogeniture (a system by which the eldest son inherits the entire estate by law), estates are normally split among heirs. The more children a family has, the more the estate is split. In this case, the net worth of the heirs is each less than that of the original decedent. The massive wealth of the original plutocrat is dissipated over several generations as the original estate is further and further split – think of the Rockefellers, for example. This process also reduces wealth inequality.

Between 1989 to 2010 there was a downward trend in the share of wealth transfers in household wealth, at least in the United States. Even if the opposite were the case, inheritances and gifts do not lead to ever rising wealth inequality but quite the opposite. Thus, a world with rising wealth transfers would not raise wealth inequality but lower it. Indeed, maybe society should encourage people to give greater gifts and leave more money in inheritances.

Feature image credit: “Torn & Cut One Dollar Note Floating Away in Small $ Pieces,” by photosteve101. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr

The post Are inheritances really that bad? appeared first on OUPblog.

April 7, 2015

How does handwashing help prevent undernutrition?

Three-year old Asha died last night, her tiny body wracked with diarrhea. Two-month old Abu is vomiting. His mother is dead and his grandmother is finding it difficult to prepare safe artificial food for him. Asha and Abu are just two reasons why Food Safety is the theme of World Health Day 2015. Asha and Abu became ill because their porridge and milk were contaminated with lethal bacteria.

Food safety means ensuring that food remains safe to eat as it travels along its path from ‘field’ to ‘plate’; and in these days, where many food paths are very long, it is not only the responsibility of governments but international producers, processors, and retailers too.

Safe food is food that is uncontaminated by:

Pathogenic micro-organisms including bacteria, viruses, amoebae, or giardia Parasites such as roundworm eggs or tapeworm cysts Toxins such as aflatoxin or cyanide in bitter cassava Harmful chemicals such as pesticides, fertilizers, and heavy metalsThese things can cause immediate food poisoning or more long term chronic conditions such as roundworm infection (ascariasis) that infest tens of millions of children living in communities where water, hygiene, and sanitation conditions are poor.

Food safety seems to be slowly improving in many developing countries–when we go to a local market the foods are usually hygienically displayed off the ground (Figure X) although much progress still needs to be made. Hygiene conditions in supermarkets, where an increasing number of people from both urban and rural areas shop, are usually good.

Figure X “A fish market in Africa.” ©Felicity Savage King and Ann Burgess, 1992; artist Jill Last. Used with permission.

Figure X “A fish market in Africa.” ©Felicity Savage King and Ann Burgess, 1992; artist Jill Last. Used with permission. Even so, it is not easy in many rural and urban communities to prevent food and water-borne disease; pathogen loads are often high, sanitation and water supplies often inadequate, and few homes have refrigerators or safe conditions for protecting or storing food. Added to this is the increasing availability and use of ‘ready-to-eat’ meals and snacks prepared by a variety of food vendors, often under non-ideal conditions. As more women work outside the home, these ‘street foods’ are becoming a popular way of feeding children. It is small wonder, then, that few have escaped bouts of food poisoning and many have had worm infections during childhood.

If we examine why Asha was fed contaminated porridge and became sick, we find several underlying reasons–her family is short of fuel, clean water, hand washing facilities, and time. The milky porridge her mother prepared each morning was easily contaminated and, because it was fed throughout the day, bacteria could multiply exponentially.

One of the chief dangers of food-borne diseases is that they are an immediate cause of undernutrition, especially in young children, because they lead to nutrients being poorly absorbed or lost due to diarrhea, vomiting, and fever, and reduced food intake due to decreased appetite.

However, there are simple measures which, if followed, can help mothers and other family caretakers keep food and water safe at the household and community level:

Wash your hands with soap Use a safe water supply Use a toilet and keep it clean Keep food covered Cook food thoroughly Eat meals soon after they are cooked so that bacteria have little time to multiply Allow children and pregnant women to be dewormed.Of these, the most important message is ‘washing hands properly.’ How many of us know or follow the six steps for safe handwashing?

Wet hands with running water Apply soap Rub hands vigorously to produce foam. Rub the backs of hands, between fingers, under fingernails and wrists Clean nails Rinse Shake hands dry, do not dry on clothes.As World Health Day reminds us about food safety this year and in the future, let us think carefully how we can protect children like Asha and Abu from food and water-borne diseases. In many situations, the most important actions are working with and supporting women. Not only do they need better resources, facilities, and information within the home, but their own health and nutrition needs protecting so that they remain healthy and able to exclusively breastfeed their babies (Figure xx). Therefore, our additional key food safety message is to ‘protect and promote breastfeeding.’

![Figure xx [11.1] Breast milk – the safest food of all Figure XX © Felicity Savage King 1985, artist Sara Kiunga Kamau.](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1428491502i/14433065._SY540_.jpg) “Figure xx Breast milk – the safest food of all.” © Felicity Savage King 1985, artist Sara Kiunga Kamau. Used with permission.

“Figure xx Breast milk – the safest food of all.” © Felicity Savage King 1985, artist Sara Kiunga Kamau. Used with permission. Image Credit: “Tammanna Akter and Joy in Barisal, Bangladesh” by Bread for the World. CC by NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How does handwashing help prevent undernutrition? appeared first on OUPblog.

The Civil War’s final battlefront

Desperation set in among the Confederacy’s remaining troops throughout the final nine months of the Civil War, a state of despair that Union General Ulysses S. Grant manipulated to his advantage. From General William T. Sherman’s destructive “March to the Sea” that leveled Georgia to Phillip H. Sheridan’s bloody campaign in northern Virginia, the Union obliterated the Confederacy’s chance of recovery.

As Civil War historian Elizabeth R. Varon recounts in Appomattox: Victory, Defeat, and Freedom at the End of the Civil War, by April 1865, General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia was primed for defeat. Here, we trace the events that led to Lee’s surrender to Grant, agreed upon in the parlor of a civilian home in Appomattox Court House, Virginia.

Featured image: Robert E. Lee accepts Ulysses S. Grant’s terms for surrender at the McLean home on April 9, 1865. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Civil War’s final battlefront appeared first on OUPblog.

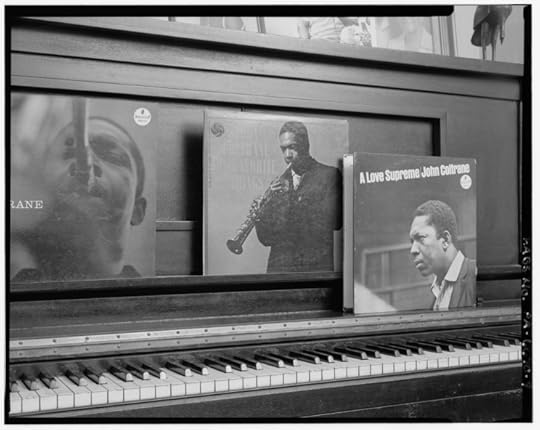

Religion in and beyond A Love Supreme

John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, which the famed saxophonist performed live only once, has the distinction of being one of jazz’s most widely celebrated yet imperfectly understood recordings. At its half-century, the devotional piece is seen as the culmination of Coltrane’s “dark night of the soul,” the sound of his heroic overcoming, and his personal entreaty to the divine. None of this is wrong, but lost is the resonance the album would have beyond its own musical particulars and its potential significance for the study of American religions and jazz. If we examine Coltrane’s own development following its release, as well as the recording’s subsequent history, we see that A Love Supreme captures a series of abiding religiosities within jazz itself. Thus, the album is not just an aural formatting of a particular religiosity, but an ongoing lens through which to propose new ways of hearing and locating religion.

By the mid-1950s, Coltrane was legendary for his “monastic” practice habits. After a period of difficulty, he experienced what he called a “spiritual awakening.” At his lowest point, Coltrane prayed to God to give him the capacity to bring people joy through music. From this point, Coltrane gave up his vices, and vowed to “dedicate his music to God, in whom he believed with increasing involvement.” The music he created between the late 1950s and his death in 1967 was increasingly exploratory, in ways that paralleled his religious investigations. As he got further from established chord structures and harmonic constraints, Coltrane read obsessively. After a period of doubt represented by 1964’s searching Crescent, A Love Supreme represents the crowning achievement in Coltrane’s self-discovery, a sonic offering to the One. His music moved beyond elongated modalism into an exultant, shouting sound that found Coltrane moving outwards into an area defined by its own motivic urgency and propulsion. Consisting of four movements – “Acknowledgment,” “Resolution,” “Pursuance,” and “Psalm” – this record marked the beginning of Coltrane’s movement, over his final three years, into a galvanic, questing, at times stratospheric music.

The suite itself has had a curious, multiple life since its release. A Love Supreme is heard, first and foremost, as Coltrane’s own mystical poetry. Ostensibly beyond specific reference, it is often adduced as the sound of African-American Christianity meshed with the growing appetite for Asian religions in the mid-1960s. Yet as important as the work was to Coltrane and his audience, its significance may actually be in its scrambling of such associations and settled formations. Coltrane started hearing sound as emanating from an agentive power beyond him. He read Edgar Cayce, Madame Blavatsky, and Cyril Scott’s Theosophical book Music: Its Secret Influence Through the Ages, scientific and mathematical theory, the New Testament, and Hazrat Inayat Khan’s The Mysticism of Sound and Music. He became influenced by the notion – popular among Swedenborgians, Theosophists, and various mystical traditions – that insight was to be gained by establishing correspondences between temporal-physical locations, musical tones, and celestial spheres. Yet many of his key influences (like Khan) disdained jazz, dismissing it as “decadent” and unworthy of religiosity.

John Coltrane House, 1511 North Thirty-third Street, Philadelphia, PA. Library of Congress

John Coltrane House, 1511 North Thirty-third Street, Philadelphia, PA. Library of Congress A Love Supreme is also heard as inaugurating a tradition. Certainly there is much evidence for this in the establishment of the Saint John Coltrane African Orthodox Church in the 1970s. In 1970s San Francisco, the Pentecostal-reared Bishop Franzo King had what he avows was a religious awakening while listening to A Love Supreme. King was inspired by his “sound baptism” to begin a ministry, combining social outreach with a fusion of traditional liturgy with veneration of Coltrane-as-saint and its use of A Love Supreme in services. But the record crosses and blends traditions in many ways. This is true not just in Coltrane’s combination of multiple musics and religiosities, or in its exemplification of the “seeker” spirituality that throve during the high point of his career. It is also visible in the album’s own crossings beyond jazz: into the MC5’s use of pure sound, into La Monte Young’s eternal drone, and into Alice Coltrane’s late writings for Hindu devotional settings, along with a broader range of religio-musical institutions in American life.

A Love Supreme is finally heard as a musical template, an expressive model for those who would follow it into constructing “religion” from improvised materials. Beyond the regular assertions of Coltrane’s divine inspiration, the notion that the religious must be indexed as overtly as on A Love Supreme if it is to be acknowledged sits awkwardly not only in the study of religion, but in the richly multifaceted history of jazz and religion both prior and subsequent to Coltrane. Coltrane rarely played music quite so structured as “Acknowledgment,” “Resolution,” “Pursuance,” and “Psalm” after this album. The attempt to reckon with religion and jazz through this album’s influence reveal limits quickly hurdled.

Coltrane, his band, and his contemporaries were also clearly aware of the album’s resonance within a wider soundscape of not simply American religious music but continual efforts by jazz musicians to articulate the sonic divine, to establish improvising rituals, to narrate African-American religious history against detractors, crafting musical metaphysics, or cultivating musical relations with sacred presence. A Love Supreme announces this breadth, drawing together some of these pursuits in a formally legible and discursively direct expression whose significance is best understood as part of an abundant, generative genealogy of improvisations of, toward, and on religions, in all of their multiplicity, in the family of music contentiously called (and denounced as) jazz. Just as Coltrane’s music gave us new ways of hearing possibility in that dusty singularity, jazz, so does A Love Supreme give us keys and cues for understanding beyond its own particulars — the ways jazz has improvised on that other moldy singularity, religion.

Headline image credit: Saxophone. CC0 via Pixabay

The post Religion in and beyond A Love Supreme appeared first on OUPblog.

Do you know your Potter from your Paddington?

The last three decades have seen arguably the most fertile periods in the history of children’s literature, across the field. The phenomenon that is Harry Potter, the rise of YA, and books that tackle difficult subjects for younger readers are just a few examples of the material included in the new edition of The Oxford Companion to Children’s Literature by Daniel Hahn. It is the first new edition in thirty years.

In celebration of the Companion’s publication, we bring you this quiz to test your knowledge of children’s literature.

Quiz image: Children reading. Public domain via Pixabay

Feature image credit: Harry Potter figure. Public domain via Pixabay

The post Do you know your Potter from your Paddington? appeared first on OUPblog.

April 6, 2015

Indiana’s RFRA statute: a plea for civil discourse

On one level, I admire the public furor now surrounding Indiana’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA). In an important sense, this discussion reflects the Founder’s vision of a republican citizenry robustly debating the meaning of important values like nondiscrimination and religious freedom. On the other hand, this public controversy has, at times, regrettably reflected failure on both sides to respect their fellow citizens and confront the merits of the issue in civil fashion.

Opponents of Indiana’s RFRA find themselves explaining why the Hoosier State’s new law differs from the federal RFRA signed by President Bill Clinton as well as many state RFRAs. All of these statutes forbid the government from imposing a substantial burden on a person’s right to exercise religion unless it has a compelling interest and the law in question is the least restrictive means of advancing that interest. These ideas embody the jurisprudence of such civil liberties giants as Justices William Brennan, Jr. and Thurgood Marshall who promulgated these concepts by dissenting in Employment Division, Department of Human Resources v. Smith.

Among the most strident critics of the Indiana law is Governor Dan Malloy of Connecticut, chairman of the Democratic Governors Association. Governor Malloy denounced Indiana’s governor, Mike Pence, as a “bigot” for signing the Indiana statute. He also issued an executive order forbidding state-funded travel to Indiana because of the state’s new RFRA law. Malloy tweeted that his opposition to the Indiana act sent “a message that discrimination won’t be tolerated.”

Unfortunately, Malloy has encountered one major problem: Connecticut has a substantively identical statute known as the Connecticut Act Concerning Religious Freedom. Indeed, Connecticut was one of the first states to adopt a state RFRA in 1993. Even as Malloy denounces Indiana’s substantively identical law as embodying bigotry, he has not called for the repeal of his own state’s RFRA. Instead, he has argued that Indiana’s law differs from Connecticut’s because the former protects the religious practices of corporations, whereas other state RFRA laws do not.

This argument is wrong. In Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., the U.S. Supreme Court held that the federal RFRA protects closely-held corporations. This conclusion is compelling as a matter of statutory terminology because the federal RFRA applies to “persons,” a term that is conventionally understood in legal discourse to include corporations. Conversely, when laws are meant to apply only to “individuals,” that is the word used. Therefore, the Hobby Lobby interpretation suggests that state RFRAs apply not only to “individuals” but to corporations that legally qualify as “persons.”

Balancing equally compelling values—like religious freedom and nondiscrimination—often requires compromise, though such compromise does not satisfy the hardcore advocates on either side of the spectrum.

This interpretation also makes sense as a matter of policy. The Congress and state legislatures that adopted RFRA statutes wanted to protect religious practices; a kosher butcher, for instance, should not lose his rights under RFRA and be forced to abandon Jewish slaughtering practices. In explicitly including corporations in its RFRA, the Indiana legislature simply codified the conventional legal understanding of the term “persons” as including corporations and similar legal entities.

Some claim Connecticut’s RFRA law differs from Indiana’s because it has protected its citizens from gender identity discrimination since 2013. As a Connecticut resident, I supported the adoption of this legislation. However, for two decades before this clause was introduced, Connecticut’s RFRA did not extend legal protection to members of the LGBT community. During these two decades, no one—including Dan Malloy—suggested that the Connecticut RFRA was an act of bigotry.

Strident rhetoric from both sides obscures the important point we should be confronting: Balancing equally compelling values—like religious freedom and nondiscrimination—often requires compromise, though such compromise does not satisfy the hardcore advocates on either side of the spectrum.

Consider one of the most frequently cited examples, a commercial photographer whose Christian beliefs sincerely lead him to favor only Christian marriage. Suppose that a couple walks into the photographer’s studio to buy film for their wedding. Imagine that the photographer rejects the validity of this couple’s wedding because they are a same-sex couple. In this example, a society that believes in the equality of its citizens will require this photographer to sell a commodity like film to any customer willing to pay the price.

On the other hand, the photographer should not be forced to photograph a ceremony against his religious beliefs. Unlike simply selling a roll of film, the photographer would be required to perform personal services by participating in an event that violates his religion. His right to refuse clients should remain valid as the photographer has engaged in the commercially and legally reasonable course of incorporating his business.

Ironically, the strongest argument against the Indiana law is one which, to the best of my knowledge, no opponent of that law has advanced: that given the legislative history of the statute, the Indiana courts will construe it, not in the tradition of Brennan and Marshall, but to limit gay rights. However, it is equally plausible that Indiana’s courts, looking at the history of federal and state RFRA laws, will engage in a more careful balancing of interests, especially when a society like ours holds values that must be reconciled in a sensitive manner.

There are thoughtful opponents of the Indiana law such as Professor Garrett Epps who, in The Atlantic, argues that RFRA doesn’t apply to corporations. My Cardozo colleague, Marci Hamilton, makes the equally thoughtful argument that there should be no RFRA statutes at all, since detailed decisions accommodating religious freedom should be made by democratically-elected legislatures. Professor Daniel O. Conkle balances his thoughtful support of the Indiana law while supporting legal protections for gay rights. In contrast to the above arguments, I think that courts, with all of their evident limitations, are often better for making fact-specific decisions, such as drawing a legal distinction between selling a commodity like film and personally attending a wedding.

I respect these commentators even if I disagree with some of them and look forward to further discussion. To the extent that law professors have provided civil voices in this debate, I am proud to be one. At the end of the day, the issues raised by this controversy are too important for strident voices on either side to dominate the debate.

Image Credit: “RFRA Protests in Indianapolis on March 28, 2015″ by Justin Eagan. CC by SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Indiana’s RFRA statute: a plea for civil discourse appeared first on OUPblog.

We should celebrate the decline of large scale manufacturing

One of the most important and unremarked effects of the revolution in information technology is not to do with information services at all. It is the transformation of manufacturing. After a period of two or three hundred years in which manufacturing consolidated into larger and larger enterprises, technology is restoring opportunities for the lone craftsman making things at home.

Before powered machinery, few enterprises achieved much scale. Those that did were often owned by local rulers like the Ptolemies’ perfume factories or Roman aristocrats wanting to put their slaves to use by making pottery out of the clay on their estates. To build a large business as a private entrepreneur was much harder. In the freest market of all in ancient times, Athens between 500 and 300 BC, there were only a few ways you could do it.

One was to be first in to a restricted site; tanneries were only allowed to operate in certain districts and the people who first took up sites in the permitted districts could expand without fear of competitors entering. Tannery owners had large workplaces and made a lot of money. You could achieve the same thing by being first to set up an ore processing facility near a mining site or an oil press near a group of farms. As long as your prices were reasonable, no one would try to challenge you.

Without these preemptive opportunities, to build a large business you have to win more volume than your competitors; this means having an advantage they cannot match, otherwise they can stop you gaining market share. For a competitive advantage to be of value, it must be manifested in one of the elements of return on capital: revenues (price), costs, or capital employed. With no industrial machinery, and relying on for much of the work on slaves whose capital cost reflected their skills, it was not possible to get an advantage in costs or in capital utilization. To compete successfully, you had to differentiate your product. In some products this was impossible: no one really cared about the quality of basic cooking pots and kitchen plates. In others, like customized jewellery, you might make the best product in Athens but if your customers associated the work with you as an individual, you could make a lot of money but could not expand your business by using other fabricators. To grow, it was necessary to have a product whose quality mattered but had to be made by a team of people so the market could not point to individual craftsmen as being the ones to buy from. Shields are a fine example; each required a team of eight to manufacture and Athens’ largest manufacturing operation was a shield factory with 120 slaves.

Greece-0103 by Dennis Jarvis. CC BY-SA 2.0. via Flickr

Greece-0103 by Dennis Jarvis. CC BY-SA 2.0. via Flickr The existence of this and several other large factories in classical Athens did not mean that most manufacturing was done there. For a huge range of other products, which made up most of consumption like clothes, shoes, simple metalwork and carpentry, there was no basis for differentiation. Almost all Athenian citizen households would have made their own clothes and many would have made simple wooden, ceramic or metal objects for their own use and sometimes to exchange with neighbours and sell in the Agora. Some would develop a high degree of skill making complex products but most made simple undifferentiated items. Using their own hands (and a slave or two) and with no competitors advantaged over any others, they could work or not as they pleased, confident of receiving the standard (not very high) price for their wares whenever it suited them to produce something. They had a rich and varied life; by reducing their expenditure and bringing in some income through making simple household products, they found the time to attend religious festivals and plays, serve in the army or navy at short notice if there was a war on, and (with some compensation for loss of earnings), get involved in civic affairs like attending the democratic assembly and serving on juries. The flexibility offered by casual manufacturing underpinned the practice of democracy and Athens’ wonderful achievements in architecture, drama, art, and philosophy.

The Industrial Revolution changed all this by creating new forms of advantage based upon operating costs and capital investment. Starting in the eighteenth century, the lower costs offered by mechanization, mass production and shared information have driven production into fewer and larger units and the amateur craftsman in the family workshop has been squeezed almost out of existence.

Pottery is an excellent example. Most potteries in Athens were small; one potter could shape enough pieces to fill a kiln in a day and only needed two or three people to help prepare the clay and manage the firing. No one seems to have had two kilns; the risks were too great. If the first kiln was successful in making highly decorated vases that sold on the basis of the artist’s skills, you couldn’t assume that an additional artist would be equally in demand. And if the product was basic kitchenware, a new kiln would have to cut price to win business and competitors were sure to retaliate. Pottery was a naturally fragmented industry until powered machinery, vastly improved temperature control and new glazing and drying technologies enabled high quality pieces to be mass produced at cost much lower than could be achieved without significant capital investment and scale. Craft potters continue to exist, though few make much of a living from their work, and the vast majority of the business became controlled by major companies operating large factories. Similar changes consolidated industries ranging from shoe-making to metal work and furniture.

From a social point of view, manufacturing had ceased to be an opportunity for modestly skilled craftsmen to supplement their living through casual engagement, mixing it with a range of other useful or interesting activities. By the twentieth century, pretty much the only way to make a living manufacturing things was in full-time employment, and those involved had little time for any other activities, let alone the sort of things that made Athens great.

But a remarkable thing seems to be happening! Just as technology transformed the economics of manufacturing in a way that encouraged consolidation, so new technology is making fragmented manufacturing viable again by removing or minimizing the benefits of scale. There is no need for in-house knowledge or apprenticeships: online courses range from a few hours to many months in any handicraft you can name. Programmable micro controllers, desktop CNC milling and routing and 3D printing make it easier and cheaper to make things to your own designs. Raw materials, even specialized ones, can be sourced on the internet, and to any required degree of pre-processing. Crowdfunding sites like Indiegogo and Kickstarter can help with finance. Makers’ Row, Ali Baba, and similar ventures enable makers to find customers without heavy advertising expenditure. Consumer preferences for non-mass produced goods and the maker’s satisfaction from autonomy and the productive exercise of skills reinforce the trend. Hence the increasing popularity of ever more sophisticated forms of DIY and of the maker movement: MAKE magazine has a paid circulation of over 100,000 growing fast and 120,000 people attended the “Maker Faire” in California in 2012.

Competitive equality between the home craftsman and the large factory is being restored. Can we use the opportunities it offers to create a great society in the way the Athenians did?

Featured Image: Sarcophagus. By dynamosquito. CC BY-SA 2.0. via Flickr.

The post We should celebrate the decline of large scale manufacturing appeared first on OUPblog.

Preparing for the 109th ASIL Annual Meeting

The 109th ASIL Annual Meeting is taking place from 8-11 April 2015, at the Hyatt Regency Capitol Hill, in Washington, DC. The ASIL Annual meeting is one of the most important events on the international law community calendar, and 2015 proves to be no exception.

This year’s conference theme will tackle the highly topical subject of ‘Adapting to a Rapidly Changing World’. Attendees will be exploring how effectively international law and international institutions are adjusting to recent, dramatic geopolitical developments. Sessions will delve into various subject areas relating to international law including: territorial disputes, human rights, energy demands, arms proliferation, shifting balances of power, and the rise of social media and its impact on international relations.

In preparation for this meeting, we asked some of our key authors to share their thoughts on the ways in which their specific areas of international law have adapted to our rapidly changing world. How can we expect international law to adapt, in the face of cyber-conflicts, new environmental challenges, and still-unanswered demands for LGBT rights, corporate responsibility, and the protection of people from mass atrocities? Can international law truly intervene to resolve global issues? We have also created a collection of free journal articles and online resources, as well as a specially selected list of books, which focuses on ASIL’s conference theme.

With more than 175 speakers and panelists, and attendees from more than 75 countries there is a lot on offer. Here are our top picks from the conference program:

Thursday, 9 April 2015International Law and the Future of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, 9:00 a.m. – 10:30 a.m.: Join moderator Sean Murphy (George Washington University Law School, author of Litigating War), speaker William Schabas, (Middlesex University, author of Unimaginable Atrocities), and others to discuss how international law can influence the realization of a lasting peace agreement.

Legitimacy, Adaptability, and Consent in Modern International Law, 9:00 a.m. – 10:30 a.m.: This session discusses the growing tension between adaptability and legitimacy in international law making. Joseph Weiler (New York University School of Law, and Editor-in-Chief of the European Journal of International Law) will moderate this timely debate. Speakers include Jutta Brunnée (Metcalf Chair in Environmental Law at the University of Toronto, co-author of International Climate Change Law) and Benedict Kingsbury (Murray and Ida Becker Professor of Law at New York University’s School of Law, Editor-in-Chief of the American Journal of International Law, and co-author of Governance by Indicators).

The Stagnation of International Law, 11:00 a.m. – 12:30 p.m.: To what extent are traditional lawmaking processes actually stagnant? What accounts for any stagnation? What is the proper role of international lawyers if law as law is marginalized? Speakers Dinah Shelton (George Washington University Law School, Editor of The Oxford Handbook of International Human Rights Law), Ingo Venzke (University of Amsterdam, author of How Interpretation Makes International Law), and Kal Raustiala (Professor of Law at UCLA, co-author of The Knockoff Economy) weigh in on this important topic.

ASIL-ICCA Task Force on Issue Conflicts in International Arbitration: Briefing and Discussion, 11:00 a.m. – 12:30 p.m.: Join the ASIL and ICCA joint task force to explore the question of “issue conflict” bias with the aim of developing guidance for the international arbitration community. Speakers include Laurence Boisson de Chazournes (University of Geneva, author of Fresh Water in International Law).

The Revival of Comparative International Law, 1:00 p.m. – 2:30 p.m.: Speakers including Lauri Mälksoo (University of Tartu, author of Russian Approaches to International Law) will explore the notion of “comparative international law” and examine how actors from different legal systems are likely to interpret and apply the norm differently.

ASIL Annual General Meeting, 2:45 p.m. – 4:15 p.m.: Remarks from the ASIL President, and the presentation of the Deák Prize!

The Role of International Law in Negotiating Peace, 2:45 pm – 4:45 pm: To what extent can negotiators help drive the peacemaking process or achieve a lasting peace? This two-hour session includes a viewing and moderated discussion of the documentary film, “The Agreement”. Panel speakers include Marc Weller (University of Cambridge, Editor of The Oxford Handbook of the Use of Force in International Law).

International Criminal Law: New Voices, 4:30 p.m. – 6:00 p.m.: Concluding remarks will be given by former Nuremberg Military Tribunals (NMT) prosecutor Benjamin B. Ferencz.

Friday, 10 April 2015Complicity in International Law, 9:00 a.m. – 10:30 a.m.: This panel brings together leading experts in the field to discuss the meaning, significance, and overlap of complicity in a rapidly changing world. Expert speakers include André Nollkaemper (Amsterdam Center for International Law, University of Amsterdam, and author of National Courts and the International Rule of Law).

Does TTIP Need Investor-State Dispute Settlement?, 9:00 a.m. – 10:30 a.m.: Learn more about the most significant international economic law treaty since the formation of the WTO. Join moderator Andrea Bjorklund (McGill University Faculty of Law, Editor of Yearbook on International Investment Law & Policy) and panelist Mark Kantor (Georgetown University Law Center, Editor of Reports of Overseas Private Investment Corporation Determinations) to discuss these controversial issues.

Perspectives on the Restatement (Fourth) Project, 9:00 a.m. – 10:30 a.m.: This Roundtable including speaker Campbell McLachlan (Victoria University of Wellington Faculty of Law, Editor in Chief of ICSID Review – Foreign Investment Law Journal) offers a range of US and comparative perspectives on the potential contribution of a Fourth Restatement.

The International Legal Framework for Outer Space in a Rapidly Changing World, 9:00 a.m. – 10:30 a.m.: Participants, including Irmgard Marboe (University of Vienna, author of Calculation of Compensation and Damages in International Investment Law) will debate the sufficiency of the international legal framework for outer space.

Global Public Interests in International Investment Law, 11:00 a.m. – 12:30 p.m.: David Caron (Dickson Poon School of Law, Kings College London, Editor of The UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules: A Commentary) will moderate this debate on how international investment law currently deals with global public interests and finding the right balance between investment and non-investment concerns.

The Hudson Medal Luncheon: “The Unity of International Law,” 1:00 p.m. – 2:30 p.m.: Don’t miss this year’s honoree speaker Professor Pierre-Marie DuPuy, the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva.

Adapting to Change: The Role of International Organizations, 1:00 p.m. – 2:30 p.m.: This panel focuses on the practices and strategies by which international organizations respond to contemporary challenges. Join August Reinisch (University of Vienna, Editor of The Privileges and Immunities of International Organizations in Domestic Courts) and others for this lively debate.

OUP Book Signing with Jens David Ohlin, 2:30 p.m.: Jens David Ohlin will be signing copies of his new book, The Assault on International Law. Join us at the OUP Booth #9-11 for this special event.

Human Rights and Sustainable Development in the Context of Fragile States, 3:00 p.m. – 4:30 p.m.: This panel considers the potential relevance of human rights standards and principles for different stages of development in conflict states. Speakers include Jan Wouters (University of Leuven, author of The Law of EU External Relations) and Andrew Clapham (the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva, Editor of The Oxford Handbook of International Law in Armed Conflict and The Geneva Conventions in Context).

Gala Dinner, 8:00 p.m. – 10:00 p.m.: Judge Rosemary Barkett, Iran-United States Claims Tribunal presentation of the Society Honors and Awards including: Certificate of Merit Award Winners Ben Saul, David Kinley, and Jacqueline Mowbray (The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: Commentary, Cases, and Materials) for high technical craftsmanship and utility to practicing lawyers and scholars; and Symeon C. Symeonides (Codifying Choice of Law Around the World: An International Comparative Analysis) in a specialized area of international law. Congratulations also to Gilles Giacca, winner of the ASIL Francis Lieber Prize for his book Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights in Armed Conflict.

Saturday, 11 April 2015Ethical Issues in International Law Practice, 9:00 a.m. – 10:30 a.m.: Catherine Rogers (Penn State Law & Queen Mary, University of London, author of Ethics in International Arbitration) and others explore ethical issues in a variety of international law-related settings.

If you are lucky enough to be joining us in DC, don’t forget to visit the Oxford University Press booth #9-11, where you can browse our award-winning books, and take advantage of the 30% conference discount. Stop by to enter our prize draw for a chance to win $250 worth of OUP books, pick up a free access password to our collection of online law resources, and browse our international law journals.

As a thank you to American Society of International Law and our customers, we are also running a special ASIL eBooks promotion, offering 50% off some of our bestselling International Law eBooks. Visit your preferred retail partner to take advantage of this offer. This offer is a consumer-only promotion available for customers in North and South America and is not valid for renewals. Offer ends 20 April 2015.

To follow the latest updates about the 109th ASIL Annual Meeting as it happens, follow us on Twitter @OUPIntLaw, and on Facebook, using the hashtag #ASILAM15.

See you in DC!

Image credit: Ocean by Jon Vlasach. The Pattern Library.

The post Preparing for the 109th ASIL Annual Meeting appeared first on OUPblog.

International law in a changing world

“For better or worse, international law is confronting a period of profound change.”

– American Society of International Law

The American Society of International Law’s annual meeting (8 – 11 April 2015) will focus on the theme ‘Adapting to a Rapidly Changing World’. In preparation for this meeting, we have asked some key authors to share their thoughts on the ways in which their specific areas of international law have adapted to our rapidly changing world. How can we expect international law to adapt, in the face of cyber-conflicts, new environmental challenges, and still-unanswered demands for LGBT rights, corporate responsibility, and the protection of people from mass atrocities? Can international law truly intervene to resolve global issues?

* * * * *

“There is increasing concern about global environmental problems like climate change, but the obstacles to collective action on an international scale continue to block progress. While international law suggests that enforcement of global environmental treaties ought to be possible, the actual machinery for ensuring compliance is almost non-existent. Thus, the only hope is to rely on consensus building strategies for generating treaties which produce ‘compliance without enforcement.’ There are dozens of global environmental treaties on the books, but it turns out to be much more difficult to modify and adapt these treaties to reflect changing political and ecological circumstances, than many experts assumed. The most effective and pragmatic path forward is to create informal problem-solving opportunities for groups of countries to modify timetables and targets without having to re-engage all the countries of the world in formal efforts to modify existing treaties. Countries concerned about their sovereign rights are often unwilling to give non-governmental organizations a formal role in environmental treaty negotiation, modification and enforcement. Yet, without the full participation of these groups, nothing important tends to happen. Environmental treaty-making today is nothing like it was in 1992 when the Rio Summit was held to kick off global efforts to respond to climate change and threats to biodiversity. Global efforts today focus on informal problem-solving, the involvement of non-governmental actors, and incentives for compliance rather than threats of enforcement. There is much more of an emphasis on capacity-building than enumerating largely unenforceable timetables and targets. Such a process might not be optimal in terms of efficient outcomes but it is more realistic and likely to be functional in a pluralistic global legal arena. Perhaps what should be further harnessed are the peace dividends which such consensus-building processes may also provide between adversaries for whom the environment could be a ‘superordinate goal’ for cooperation.”

— Saleem H. Ali, Professor at the Sustainable Minerals Institute, University of Queensland, and Lawrence Susskind, Ford Professor of Urban and Environmental Planning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, authors of Environment Diplomacy, Second Edition

* * * * *

“As dominant global frameworks for acknowledging and addressing mass harm, international and transitional justice look to the future. Through the redress of state harm, they seek to effect social, legal and political change in order to pave the way for a more just communal existence. Global and national change is thus framed as progressive; indeed transitional and international justice both position themselves as constituent movements in the building of a more humanitarian socio-legal order in which human rights abuses will no longer go unpunished. In this context, our scholarly intervention has been to refocus attention on the past and its enduring implications. Our article, and the broader Minutes of Evidence project of which it is a part, draws attention to the ongoing significance of settler colonialism, in particular the structures of injustice it enabled and continues to maintain. Our aim is to unsettle the presentist and future-oriented approach of international and transitional justice as a means of thinking more holistically about what injustices may demand redress and, in turn, what a committed ‘justice agenda’, what we term structural justice, may require. As such, we would flip the question posed, from one of how international law can adapt to the rapidly changing world to whether and how international law can look back and acknowledge and account for history and its continued significance.”

— Jennifer Balint, Lecturer in Socio-Legal Studies, Julie Evans, Senior Lecturer in Criminology, and Nesam McMillan, Lecturer in Global Criminology, School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Melbourne, authors of ‘Rethinking Transitional Justice, Redressing Indigenous Harm: A New Conceptual Approach’ in the International Journal of Transitional Justice

* * * * *

“Practice is the magic word for international lawyers to justify legal claims, to account for a particular interpretation of a rule or to explain the development of the law over time. The interesting thing is that no one really cares to explain what is practice and whose practice matters, let alone international law scholars who engage themselves in a form of (theoretical) practice. ‘Practice’ is something that goes without saying in the profession. As such, it means different things to different people in different contexts. Interestingly, questions such as ‘what is practice?’, ‘whose practice?’, and ‘how does practice work?’ are not questions that the law alone can answer. To understand the societal structure of a group (be it the international community or the ‘invisible college of scholars’), how its members behave, and what kind of strategies they deploy to achieve certain ends are not issues that international lawyers generally feel concerned about. This is a pity, as sometimes an interdisciplinary inquiry allows a better grasp of legal phenomena. Overall, practice in its ‘infinite variety’ is the best instrument we have to adjust to a rapidly changing world. It would be good if we could understand better what’s going on… in practice.”

— Andrea Bianchi, Professor of International Law, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva, and author of ‘Gazing at the Crystal Ball (again): State Immunity and Jus Cogens beyond Germany v Italy’ in the Journal of International Dispute Settlement

* * * * *

“International law and US domestic law have become much more intertwined in recent years, in areas ranging from international human rights litigation, to foreign official immunity, to military commission trials for suspected terrorists. The international law that is applied in the US legal system is inevitably shaped and altered by its interaction with domestic rules and doctrines. There has also been more inter-branch disharmony in foreign relations in this period, a phenomenon that has manifested itself in greater congressional efforts to direct U.S. foreign policy, more executive branch reliance on executive agreements and soft law as an alternative to treaty-making, and less systematic deference by the courts to executive branch claims about US foreign relations interests. Scholarship concerning foreign relations law also has evolved, with somewhat less focus on originalist accounts of the distribution of foreign relations authority and more consideration to longstanding patterns of historical practice as well as empirical assessments of how aspects of the law operate in practice.”

— Curtis A. Bradley, William Van Alstyne Professor of Law, Duke University School of Law, and author of International Law in the U.S. Legal System, Second edition

* * * * *

“Victim participation in international criminal trials is a relatively new field of law. While this right had been recognised by some legal systems around the world, mainly civil law systems, developments at the international level only started in the 1980s with the adoption of United Nations’ declarations recognising victims’ rights to justice and reparations. Later, with the wake of the ad hoc international criminal tribunals (for Rwanda and the Former Yugoslavia), the world was confronted with trials that discussed the suffering of thousands of individuals without giving them an independent voice or role (they only intervened as witnesses for the prosecution). The adoption of the Statute of the International Criminal Court introduced, for the first time in the history of international criminal tribunals, the possibility for victims to act as independent participants in proceedings and to receive reparations in the context of a criminal trial. Being a new field of law, international courts have encountered a number of challenges in the implementation of victims’ rights to participation in international criminal proceedings. We believe that victims are the raison d’être of these tribunals and the ultimate beneficiaries of the justice they deliver; more needs to be done to ensure that they can genuinely be involved in justice processes that affect them.”

— Gaëlle Carayon, International Criminal Court Legal Officer, REDRESS UK, and Mariana Pena, independent expert in international justice and victims’ rights, authors of ‘Is the ICC Making the Most of Victim Participation?’ in the International Journal of Transitional Justice

* * * * *

“The ‘rapidly changing world’ has and will continue to challenge the efficacy of many areas of international law, in many cases generating important evolutions in the law. The law of armed conflict, also known as international humanitarian law, is in many ways an iconic example of this process of ‘responsive evolution.’ The military response to internal and transnational non-state threats, to include transnational terrorist organizations, has been the focal point of this evolution during the last two decades. The invocation of what might best be called, ‘wartime powers’ to address these threats has stressed this area of the law significantly, but has in many ways compelled a recommitment to the core principles of the law and the essential balance between authority and humanitarian restraint that lies at the very foundation of the law.”

— Geoffrey S. Corn, Presidential Research Professor of Law, South Texas College of Law, and co-author of The War on Terror and the Laws of War: A Military Perspective, Second Edition

* * * * *

“I work on several areas of law including human rights law, humanitarian law, refugee law, and national security law. Each of these has been impacted by incessant armed conflict in the Middle East, especially in recent years. This includes civil war in Syria, which has caused an exodus of Syrian refugees and the secondary forced displacement of Palestinian refugees, thus testing the limits of temporary protection regimes and the adequacy of UN interagency collaboration; targeted killings in Yemen and, beyond the Middle East, in Afghanistan and Pakistan, thus redefining the law of self-defense and particularly the temporal element of imminence; and Israel’s third assault on the besieged Gaza Strip in the past six and a half years, putting into question the adequacy of the laws of occupation and the legal mechanisms meant to enforce them. What I have found in these instances, and the many I do not have room to describe, is that during armed conflict, the law rapidly adapts to expand the authority of belligerent states rather than to restrict them. History has shown that social movements contract those powers to expand protection to civilians once the conflict is over.”

— Noura Erakat, Assistant Professor, New Century College, George Mason University, and author of ‘Palestinian Refugees and the Syrian Uprising: Filling the Protection Gap during Secondary Forced Displacement’ in the International Journal of Refugee Law

* * * * *

“It might be better to ask how international law generally has (or is) adapting to a rapidly changing world – and if that were the question the answer would have to be that it has not yet begun to recognise, let alone accept or respond to the changing natures of communities, identities and how they relate to one another. Turning to one of ‘my’ areas, it is increasingly obvious to me that the manner in which international law engages with issues of human rights is antediluvian. Although there have been innovations, the primary tool at the disposal of the UN Human Rights Treaty Bodies remains the ‘reporting procedure’ – first devised over 50 years ago and replicated in one form or another in most of the treaties ever since. The theory, and to an extent the practice, of that system still remains locked in the politics of a by-gone era and does much to perpetuate them in the one place above all others where there really should have been some adaptation to a rapidly changing world. But then, international law has never been particularly adept at dealing with egregious wrongs, though if this were a school report, surely it would say ‘could try harder’?”

— Malcolm Evans, Professor of Public International Law, University of Bristol, Co-Editor in Chief, Oxford Journal of Law and Religion, editor of Blackstone’s International Law Documents, and editor of International Law, Fourth Edition

* * * * *

“Russia’s ongoing intervention in the Ukraine in 2015, and fears of further ‘muscle-flexing’ in the Baltic states, suggest that the continued presence of NATO’s ‘Missile Defence Shield’ will remain an invaluable strategic ‘feature and fitting’. The much broader question of whether the use of missile defence shields helps support the existence of a wider right of anticipatory self-defence and the point at which an ‘automated’ response takes place. Does such a response fall within the barometers of necessity and proportionality that govern a state’s lawful recourse to self-defence under international law? Against these legal concerns, one obviously needs to also factor in policy and strategic reasons for having Missile Defence Shields as a ‘necessary’ defence in the modern world. This of course presumes that necessity, proportionality and imminence are, or could be, easily and uncontrovertibly discerned.”

— Francis Grimal, Senior Lecturer in Public International Law, University of Buckingham, and author of ‘Missile Defence Shields: Automated and Anticipatory Self-Defence?’ in the Journal of Conflict and Security Law

* * * * *

“As a generalist in international law, but with specialties in human rights, armed conflict, and foreign investment, I would say there’s absolutely no doubt that the rise of NGO involvement in lawmaking and law application has fundamentally changed these fields. States can no longer make law without involving the nongovernmental stakeholders, and international organizations rely on them for expertise and credibility as well. Even the law of war has evolved in large part due to the work of the ICRC, an usual NGO but still nongovernmental in nature. The current stresses faced by investor-state arbitration are also a product of NGO activism. Given their new roles, NGOs need to be responsible players in lawmaking and law implementation too.”

— Steven R. Ratner, Bruno Simma Collegiate Professor of Law, University of Michigan Law School, and author of The Thin Justice of International Law: A Moral Reckoning of the Law of Nations

* * * * *

“The 1951 Geneva Convention relating to the Status of Refugees is the cornerstone of international protection law. Drafted when the atrocities of the Second World War were within recent memory, the Convention is recognized as a ‘living instrument’ that is ‘constant in motive but mutable in form’. From protecting political dissidents during the Cold War to extending asylum to persons at risk of being persecuted because of their gender or sexual identity, the Convention has proven capable of adapting to the diversifying profile of asylum-seekers in a globalised world. At the same time, a wider field of international protection law has developed to accommodate persons who do not fit within the narrow refugee definition under the 1951 Convention, for example people fleeing from indiscriminate violence. Today, the world is facing environmental and demographic ‘mega-trends’ including rapid population growth and global climate change, which together can contribute to refugee-like cross border displacement. Recognizing that a number of the necessary preconditions for an effective new international agreement on the protection of ‘environmental migrants’ are unfulfilled, a pressing question for international protection law concerns the extent to which new forms of displacement can be accommodated by ‘living instruments’.”

— Matthew Scott, Doctoral Candidate in Public International Law, Faculty of Law, Lund University, and author of ‘Natural Disasters, Climate Change and Non-Refoulement: What Scope for Resisting Expulsion under Articles 3 and 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights?’ in the International Journal of Refugee Law

* * * * *

“Adaptability is just one of several features for applying human rights, the others being availability, accessibility, and acceptability. Adaptability applies particularly to economic, social, and cultural rights such as education. The concept means that human rights are flexible (that is, amenable to the needs of changing societies and communities) and responsive (to individual and community needs within diverse social and cultural settings). A dynamic environment offers opportunities to fully develop the human personality in exciting ways. But human rights must be safeguarded so as not to lose sight of the non-negotiables, like ensuring respect for human dignity. Advocates undertake a constant effort, getting their hands filthy with the mechanics of interrelatedness and pragmatism to get the engine going. So human rights adapt – perhaps more by necessity than deliberation – through greater inclusiveness (multiple participants), confronting realities (e.g. what technology can and cannot do) and accommodating other influences, especially money. Travelling to the outer edges oftentimes requires revisiting the essentials, such as what is a human right and what purpose does, or should, a human right serve. This faithful self-scrutiny makes human rights more resilient, and bestows them with an enduring relevance, whatever else might be bubbling along in the moment.”

— Stephen Tully, barrister, St James’ Hall Chambers, and author of ‘A Human Right to Access the Internet? Problems and Prospects’ in the Human Rights Law Review

* * * * *

“International economic law has not adapted very well to the rapidly changing world. On the one hand, preferential trade agreements have been proliferating, while on the other hand, negotiations in the World Trade Organization (WTO) have faced numerous setbacks and delays. The validity of preferential trade agreements under WTO law and their role in enhancing welfare through liberalising trade remain dubious, particularly given problematic ‘WTO-plus’ elements in these agreements, such as the imposition of ever higher intellectual property standards. In the investment context, states are increasingly questioning the absolute nature of many investment obligations, as well as the legitimacy of the investment treaty arbitration system. At the same time, the most-favoured-nation obligation and the ability of multinational companies to restructure themselves and manipulate their investments and nationality continue to erode the significance of carefully drafted treaty terms in international investment agreements. The current haphazard nature of international trade law and international investment law may undermine regulatory sovereignty, development efforts, and the underlying rationales for these regimes, and neither regime has yet been able to find multilateral solutions to these issues.”

— Tania Voon, Professor at Melbourne Law School, University of Melbourne, and author of ‘Legal Responses to Corporate Manoeuvring in International Investment Arbitration’ in the Journal of International Dispute Settlement

* * * * *

Headline image credit: Sunset over South Africa by Harvepino via Shutterstock.

The post International law in a changing world appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers