Oxford University Press's Blog, page 678

April 12, 2015

‘Buyer beware': how the Federal Trade Commission redefined the word ‘free’

Last month marked the 100th anniversary of the Federal Trade Commission, the regulatory agency that looks after consumer interests by enforcing truth in advertising laws. Established by the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914 and signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson, the FTC opened its doors on 16 March 1915, taking the place of the older Bureau of Corporations.

The FTC got off to a rocky start. In its early years, it was underfunded, hobbled by in-fighting among the commissioners, and was challenged regarding its mission to combat “unfair methods of competition.” In time, the commissioners came to view deceptive advertising as a means of unfair competition, falsely attracting customers from one’s competitors. But the courts were not always sympathetic to this idea. In 1925, the Third Circuit Court took a caveat emptor approach in the case of John C. Winston Co. v. Federal Trade Commission. The Winston Company offered consumers free encyclopedias but required buyers to pay $49.00 for “encyclopedic and research services.” The court wrote that “a very stupid person might be misled by this method of selling books, yet measured by ordinary standards of trade and by ordinary standards of the intelligence of traders, we cannot discover that it amounts to an unfair method of competition.” In order words: let the buyer beware.

By the 1930s, consumers were getting more protection from “free” offers like the so-called Standard Education Society. Targeted consumers were told they had been chosen by an elite group to receive a deluxe edition of the New Standard Encyclopedia; they were even asked if their names could be used in advertisements. Again, the encyclopedia was free but ten-year supplements (a required “loose leaf extension service”) had a charge of $69.50, which is more than $1000 in today’s money.

The Second Circuit rejected the FTC’s claim of unfair trade practices, with Judge Learned Hand writing, “We cannot take seriously the suggestion that a man…will be fatuous enough to be misled by the mere statement that the first are given away and that he is paying only for the second.” The Supreme Court reversed that opinion, with Justice Hugo Black writing that “Laws are made to protect the trusting as well as the suspicious…The rule of caveat emptor should not be relied upon to reward fraud and deception.” Not long afterward, the Wheeler–Lea Act of 1938 formally broadened the FTC’s powers to include protecting consumers from false advertising.

There was still more to be settled about the hidden conditions of “free gifts.” In the 1950s, the Book-of-the-Month Club published advertisements that had the word “FREE” in large print at the top, offering a featured book at no cost to those who joined. The very fine print at the bottom explained that members were obligated to “purchase at least four books-of-the-month a year” or be charged the full price of that initial free book. The FTC told them to stop using the word “free” and when the book club challenged that, the Second Circuit Court agreed with the FTC. Later, in the 1960s, the FTC and the courts took on the “buy-one-get-one free” strategy. It was paint, not books, this time. In the case Federal Trade Commission v. Mary Carter Paint, the Supreme Court affirmed that an advertiser could not promote a “buy-one-get-one free” offer if the total price was greater than the regular price for the individual item.

Current FTC guidelines stress that “free” means the consumer is paying nothing for the item in question and no more than regular price for any accompanying purchases. The guidelines also explain that special conditions—the fine print—must be “set forth clearly and conspicuously.” The FTC does more than just monitor “free” offers of course. Today, it investigates all sorts of unfair, deceptive, and fraudulent practices in the marketplace, from car dealership practices to cigarette warning labels, to fake dating profiles and wireless phone service cramming.

So happy belated birthday, Federal Trade Commission. Here’s to your next hundred years. Caveat venditor.

Image Credit: “Federal Trade Commission, Washington, D. C.” by the Boston Public Library. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post ‘Buyer beware': how the Federal Trade Commission redefined the word ‘free’ appeared first on OUPblog.

A better strategy for presidential candidates

The invisible primary is well underway. From Jeb Bush to Hillary Clinton, Rand Paul to Marco Rubio, candidates are already angling for votes in the prized Iowa caucus. News cycles are abuzz with speculation about who the candidates will be and what their chances are, but much of this coverage asks the wrong question. Instead of focusing on the candidates themselves and their fundraising spoils, we should pay close attention to who the candidates hire as their pit crew for their field campaign. Campaign managers must secure staff who know how to build people power in an electoral system where money, marketing, and data are king. Nothing wins elections like votes, and to win votes, you have to know how to win people.

It was famed community organizer Saul Alinsky who once said that there are two forms of power: organized money and organized people. Our electoral system weeds out candidates without access to money, and both the eventual Republican and Democratic candidates will enjoy sizable war chests once partisan donors close ranks around their respective nominees. Candidates’ competitive advantage can come from the ways in which their staff — particularly their chosen field operatives — decide to organize the candidate’s constituents.

In a world of increasingly polarized politics and hyper-competitive presidential campaigns, most of what the campaigns actually do does not have much impact on the outcome of the race. Despite all the focus on the horse race in political campaigns, the effect of party conventions, presidential debates, and candidate gaffes pale in comparison to the effect of voters’ perceptions of the economy. Much of what the campaigns do in the horse race cancels each other out.

The challenge for candidates seeking to build a winning campaign in 2016, then, is to identify a team of people who know where to find a competitive edge in a world where those edges are increasingly elusive.

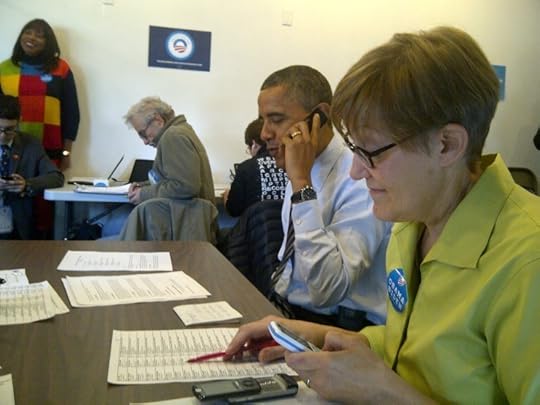

Obama thanking his volunteers on Election Day 2012 by TonyTheTiger. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Obama thanking his volunteers on Election Day 2012 by TonyTheTiger. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. For many years, campaigns thought that organizing people meant marketing candidates to voters in the same way that we market cereal, ketchup, or cars. In 2012, however, Obama’s ground game engaged more people in the campaign than any other campaign that preceded it, with over 2.2 million volunteers. Those volunteers were organized into 10,000 neighborhood teams, each of which were staffed by 30,000 leaders and core team members who devoted more than ten hours per week to the campaign. How?

They hired organizers. In so doing, they made the campaign a vehicle for political participation.

Obama staffers were trained to organize themselves out of a job by enlisting supporters like Shirley Bright. Bright, an Obama volunteer from North Philadelphia, had never before been involved in electoral politics. She remembers walking into a field office in 2008 and asking what she could do to help. Instead of thrusting a get-out-the-vote script and a telephone upon her, the organizer asked her why she supported Obama, shared his personal story, and then asked her to take on a volunteer leadership role. After all, Bright knew the intricacies of her community far better than a 20-something staffer who had just arrived, bleary-eyed from working nonstop in other primary states. “It’s urban,” Bright said of her community. “It’s in transition right now. It’s been becoming gentrified, but a lot of the people still live here who lived there for 30, 40 years or more. It has projects. It has newly redeveloped houses. It has row houses that have been on a block for many years, co-existing with blocks where houses have been torn down.”

Research tells us that ground games are at their best when local volunteers like Bright are engaging their peers and neighbors in authentic conversations about the election. Recruiting, training, and managing the armies of volunteers needed to do that at the scale needed to win a presidential election is no easy task, however. What the Obama campaign taught us is that organizing people is not about marketing a candidate, but instead about building a campaign that gives real responsibility to ordinary people.

Replicating what the Obama campaign did is not as easy as learning a formula. Candidates who hope to model themselves on the Obama campaign by imitating high-tech start-ups will find themselves with long voter lists and lots of money, but nobody to do the work of actually speaking with the voters. If candidates really want an Obama-style ground game, they must hire staff who know how to lead an operation that puts people at the center, invests in training them, and is willing to take risks by empowering them with access to resources, like both parties’ much-vaunted voter databases.

Every 2016 presidential candidate is going to have an expert team of lawyers, consultants, and media leads. What could differentiate the campaigns from each other is the extent to which they hire field staff who know how to build people power.

Heading image: Obama Austin by roxannejomitchell. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A better strategy for presidential candidates appeared first on OUPblog.

Jonas Salk and the polio vaccination

Today, 12 April 2015 marks the sixtieth anniversary of the announcement that Jonas Salk’s vaccine could prevent poliomyelitis. We asked Charlotte Jacobs, author of Jonas Salk: A Life, a few questions about this event.

What is the significance of this date?

Ever since 1916, when poliomyelitis struck 27,000, mostly children, in America’s first large epidemic, parents had feared the onset of summer. As the number of victims increased yearly, pictures of children on crutches and in iron lungs filled the news. Then, on 12 April 1955, a waiting world learned that Jonas Salk’s vaccine could prevent polio. Two remarkable aspects stand out with regard to that accomplishment: First, Salk and his small research group, not some large pharmaceutical company, prepared the vaccine in only three months. Secondly, the American public, through the March of Dimes, funded his work and conducted the national trial, including over a million children, which confirmed the vaccine’s effectiveness.

alk became an international hero overnight, yet he received few accolades from the scientific community. Why not?

In the wake of his achievement, Salk did receive a staggering number of awards. While heads of states around the world rushed to honor him, the scientific community—the one group whose adulation he craved—remained ominously silent. “The worst tragedy that could have befallen me was my success,” Salk later said. “I knew right away that I was through—cast out.” This young researcher, not yet a member of the scientific brotherhood, had made and initially tested the polio vaccine in secret while challenging one of their firmly held principles—that only a vaccine made of live virus could impart lifelong immunity. They accused Salk of failing to give proper credit to other researchers; senior scientist Albert Sabin promulgated the impression of Salk as a technician who borrowed others’ methodologies to concoct the vaccine, calling him a “kitchen chemist.” To make matters worse, because Salk reached out to the public in ways scientists had never done, many accused him of crossing the line of academic decorum by soliciting media attention.

What is the difference between Salk and Sabin’s vaccines?

At the time of the polio trial, most virologists believed that only live viruses could provide lifetime protection by inducing a low-grade, almost imperceptible infection. They held fast to this tenet with what one epidemiologist called “an almost religious fervor.” Salk thought that a killed virus, although it had lost its ability to cause infection, could still stimulate production of antibodies. Thus, the first successful vaccine was made from killed poliovirus. Over the next five years, it reduced the incidence of paralytic polio in the United States by ninety percent.

Most senior scientists, led by Albert Sabin, still maintained that only a vaccine made from live, weakened virus could eradicate polio. Sabin prepared and tested such a vaccine. In 1961, the US Public Health Service replaced Salk’s vaccine with Sabin’s oral vaccine, delivered in a sugar cube, citing cost and convenience. Salk warned that live virus, although weakened, could revert to its virulent form and cause polio. In his efforts to have Sabin’s vaccine de-licensed, he was overruled by the major medical decision-makers.

By 1968, US pharmaceutical companies had stopped manufacturing the Salk vaccine. Although most cases of paralyzing polio in the United States could be traced to Sabin’s vaccine, it had become entrenched. Salk set out to reverse what he called a risky, politically-driven decision—a sole warrior in a fight that lasted the rest of his life. In 1999, the US government recalled the Sabin vaccine, replacing it with a newer version of Salk’s vaccine. By then, Salk was dead.

Today a great deal of controversy surrounds vaccination of children. Did Salk face any public controversy?

In the 1950s, the paralysis and death of children was so devastating that parents pleaded for their children to be vaccinated. Yet Salk did have his detractors. Among the most vitriolic was D. H. Miller, self-proclaimed president of Polio Prevention, Inc., who circulated anti-vaccination literature nationwide. One, entitled “Little White Coffins,” began, “Only God above will know how many thousands of little white coffins will be used to bury the victims of Salk’s heinous, fraudulent vaccine.”

Just weeks before the national trial of Salk’s vaccine commenced, Walter Winchell, a popular newsman for ABC, announced on his Sunday night radio program: “Good evening, Mr. and Mrs. America and all the ships at sea! Attention, everyone! In a few moments I will report on a new polio vaccine. It may be a killer!” An estimated 150,000 children were kept from participating in the field trial by frightened parents.

In 1955, after the vaccine was released to the public, the state of Massachusetts closed its vaccination program because of a manufacturing misstep leading to contaminated vaccine. Even though this was quickly corrected, Massachusetts didn’t reopen its program upon the advice of several Nobel-Prize laureates. That summer the state suffered an epidemic of polio. Four thousand contracted the disease, 1700 were paralyzed.

What would have happened if Jonas Salk set out to accomplish the same feat today?

Today development of a vaccine is a much more complex undertaking and can take ten to fifteen years from concept to public availability. Salk made his vaccine in a time of dire need, completely funded through the March of Dimes, and with almost no government regulations. Given Salk’s legendary perseverance, however, I have no doubt he would accomplish the same today.

Feature Image: Bundesarchiv B 145 Bild-F025952-0018, Bonn, Gesundheitsamt, Schutzimpfung. Photo by Jens Gathmann. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post Jonas Salk and the polio vaccination appeared first on OUPblog.

Older adult’s social networks and volunteering

We know that volunteering is important for health and well-being among older people. While higher education is known to facilitate volunteerism, much less is known about the role of social networks. Networks are a social resource, important because of the relationships they engender and because they change over time. They may grow or diminish in size, and change in composition to include those who are in general older or younger, family, or friends. Changes in network size and composition offer opportunities to bridge or connect the individual to others. Moreover, network members may live closer or further away and engage in more or less contact over time. Changes in geographic proximity and contact frequency tap into bonding aspects of networks. We examine changes in social networks that promote connections with others through bridging and bonding, and then investigate whether such changes influence volunteerism directly, or in conjunction with education.

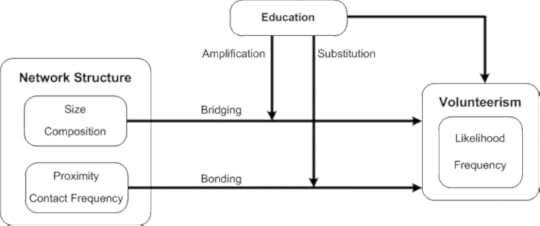

Education and social network characteristics may interact with one another to influence volunteering activities. One question we address in this study concerns a situation of substitution. Can access to advantageous social networks (e.g., larger, frequently seen, more proximal, higher proportion of friends) compensate for low education levels to predict volunteerism? In other words, will lacking in one resource (education) be substituted, and compensated for, by the strength inherent in the other (networks)? On the other hand, a situation of amplification may be more likely. Amplification emphasizes a cumulative advantage position because those who have high levels of education are better able to leverage advantages that come with helpful network characteristics. Hence, we draw from the traditions of social network theory as well as social gerontology to identify multiple dynamic dimensions of network structure and education as key factors that influence the outcome of volunteerism both directly and in conjunction with one another (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Interplay of Social Relations, Education, and Volunteerism

Figure 1: The Interplay of Social Relations, Education, and Volunteerism Unique data on social networks collected from the same people in 1992 and 2005 (13 years apart) were used to identify how network changes influence the likelihood and frequency of volunteering through bridging and bonding mechanisms directly and in conjunction with education. The sample consisted of 543 adults living in the metro-Detroit area who ranged in age from 50 to 100 in 2005. Approximately one-third (32%) of participants reported volunteering. The amount of hours per year spent volunteering ranged from 0-780 hours. On average, those who volunteered did so approximately 67 hours during a year.

Network changes resulted in both bridging and bonding to influence whether or not people volunteer. Bridging elements that surfaced as important for volunteering has to do with who is in one’s network more than the size of one’s network. As networks change over time to comprise less family, the likelihood of volunteering increases. Bonding elements also mattered. As older adults developed more geographically proximal networks, they were more likely to volunteer. This bonding dimension may serve as a resource in an increasingly mobile society simply because proximity promotes face-to-face interactions, an important aspect of sociability, especially for older adults.

While bridging and bonding facilitate the likelihood of volunteering, bridging elements of networks also influence how often people volunteer. Again, it’s who is in the network that seems to matter most. As the older adults’ networks acquired younger members, volunteer frequency increased. It may be that volunteerism fills a void created by the loss of older network members. Additionally, having younger network members may simply prompt more activity and opportunities for volunteering among those 50 years and older.

Higher education levels were associated with a greater likelihood of volunteering. Interestingly, however, higher education levels had no effect on the number of hours people volunteered per year. In terms of the combined influence of education and social networks on volunteering, how much people volunteer is influenced by bonding aspects over time only in the context of low levels of education. In this context, as networks become more geographically proximal and older adults are in more frequent contact with their networks, they are more likely to volunteer at higher levels. So lacking in one resource (education) is substituted for, and compensated by, the strength inherent in the other (social networks). Such findings make visible the potential impact of a social resource.

Future studies will need to better specify the direction of the links between social network change and volunteerism. It could be that volunteering initiated this study’s detected changes in network characteristics. If so, it may be that the act of volunteerism promotes change in social networks that incur both bridging and bonding tendencies rather than the reverse. Regardless, social network change is clearly associated with volunteerism, and we expect that it is most likely bi-directional, that is, both are causing changes in the other.

This study characterized social networks in terms of bridging and bonding aspects that can change over time. This approach positions networks as an important resource for integration, embeddedness, and ultimately continuous and long lasting engagement in various social roles. As such, policy makers and program planners should not view pathways to volunteerism simplistically. The ways social networks change have significant implications for the roles older adults play in society.

Featured image credit: Hands in old age. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Older adult’s social networks and volunteering appeared first on OUPblog.

The world as hypertext

We all have experiences as of physical things, and it is possible to interpret these experiences as perceptions of objects and events belonging to a single universe. In Leibniz’s famous image, our experiences are like a collection of different perspective drawings of the same landscape. They are, as we might say, worldlike.

Ordinarily, we refer the worldlike quality of our experiences to the fact that we all inhabit the same world, encounter objects in a common space, and witness events in a common time.

J.S. Mill thought that we should abandon this way of thinking. According to Mill, the world is a collection of “permanent possibilities of sensation”–fundamental propensities for conscious experiences to occur in certain patterns rather than others (or in no pattern at all). The physical world that we perceive doesn’t explain the worldlike quality of our experiences: it is the worldlike quality of our experiences, or rather it is the tendency for experiences to constitute a worldlike totality of the sort that our experiences do, in fact, constitute. This proposal has come to be known as “phenomenalism.”

The phenomenalist sees the physical world as an all-encompassing hypertext. The cantaloupe on the table is not an independently-given thing-in-itself that lies behind my visual experiences of it. The cantaloupe is a network of phenomenological hyperlinks. Click for visual sensations of something round and beige. Click again for tactile sensations of something cold and rough. With luck, the next click will take you to flavor sensations of something sweet and juicy.

The hypertext analogy must be handled with care. In an actual hypertext (like the one you’re reading now), the links are grounded in some underlying computer hardware: take away that underlying hardware, and you take away the hypertext. In the phenomenalist’s world, the only thing that underlies a hyperlink is more hyperlinks. The computer hardware is itself nothing but a system of hyperlinks. It’s hyperlinks all way down.

Colour Abstract, by @Doug88888. CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr

Colour Abstract, by @Doug88888. CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr Another potentially misleading feature of the hypertext analogy is that the navigator of an actual hypertext (like you) is not part of the hypertext that he or she navigates. But when a phenomenalist says that the world is an all-encompassing hypertext, he means it. Not only is the melon a network of phenomenological hyperlinks: so is the refrigerator that chills the melon, the knife that cuts the melon in half, the hand that holds the knife, and the mind that guides the hand. A cantaloupe is a tendency for conscious experiences to occur in one sort of pattern; a mind is a tendency for conscious experiences to occur in a different sort of pattern.

Because phenomenalism has never been very popular, the theory hasn’t really evolved since Mill introduced it to the world in 1865. One significant development during the intervening 150 years was a revolution in our understanding of time. Time, it turns out, is not an independent dimension, but merely an aspect of relativistic spacetime. And in relativistic spacetime, there is no way for things to relate temporally without also relating spatially.

This has important implications for phenomenalism. A physical object, on Mill’s view, is a tendency for conscious experiences to occur in certain temporal sequences rather than others. This makes sense only on the assumption that conscious experiences occur in time, which, in a relativistic context, makes sense only if the experiences also occur in space.

But if conscious experiences are in space as well as time, physical things start to look more like geometrical than logical constructions of experiences (assuming that they are experiential constructs at all). Mill’s position devolves into a panpsychism that differs from common materialism mainly in its attribution of sentience to fundamental particles.

To avoid this slide into panpsychism, a phenomenalist has only one choice. He has to take consciousness out of time.

Now, most people, including Mill, think it is beyond obvious that experiences occur in, extend through, and change over time. To them, the suggestion that consciousness might not be in time is not just wrong, but unintelligible.

But is it?

“The natural world is far less mysterious to us than it was just a few centuries ago—except for that bit of it called ‘consciousness.'”

When I gaze at the full Moon, I have an experience as of something round and enduring: my experience has the qualities of phenomenal roundness and phenomenal duration. From the fact that the experience is phenomenally round, I don’t infer that it is literally round (like the Moon itself). So why should I infer from the fact that the experience has the property of phenomenal duration that the experience literally endures? Why should the evidence of introspection lead me to infer that my experiences have any objective temporal features at all?

Once we see that there’s no incoherence in the idea that consciousness transcends time, an intriguing possibility comes into view: the possibility that consciousness might serve as a suitable basis for the metaphysical reduction of temporal phenomena, including time (or spacetime) itself.

Phenomenalism can easily seem out of touch with modern ways of thinking. The natural world is far less mysterious to us than it was just a few centuries ago—except for that bit of it called “consciousness.” Putting consciousness at the foundation of our metaphysics can easily look like trying to explain the well-understood in terms of the poorly-understood.

But sometimes the best thing to do with something that resists explanation is to cast it in the role of unexplained explainer. (The evolution of scientific thinking about gravitation is a good case in point.) That is the role that Mill envisioned for consciousness in relation to the physical world.

Is philosophy ready to take phenomenalism seriously? I don’t know. It depends on how willing we are to step back and survey the field of metaphysical possibilities as if for the first time. “Common sense,” writes Russell, “leaves us completely in the dark as to the true intrinsic nature of physical objects, and if there were good reason to regard them as mental, we could not legitimately reject this opinion merely because it strikes us as strange. The truth about physical objects must be strange.” Phenomenalism might be that strange truth.

The post The world as hypertext appeared first on OUPblog.

April 11, 2015

Shakespeare’s false friends

False friends (‘faux amis’) are words in one language which look the same as words in another. We therefore think that their meanings are the same and get a shock when we find they are not. Generations of French students have believed that demander means ‘demand’ (whereas it means ‘ask’) or librairie means ‘library’ (instead of ‘bookshop’). It is a sign of a mature understanding of a language when you can cope with the false friends, which can be some of its most frequently used words. Having a good grasp of the false friends is a crucial part of ‘learning to speak French.’

Shakespeare has false friends, too. A 16th- or 17th-century word may look the same as its Modern English equivalent but its meaning has radically changed. Naughty doesn’t mean ‘naughty.’ Revolve doesn’t mean ‘revolve.’ Ecstasy doesn’t mean ‘ecstasy.’ Some of these words occur so often in the plays and poems that they can be a regular source of misunderstanding. The obvious solution—as we do in learning a foreign language—is to get to know them in advance as part of the process of ‘learning to speak Shakespearian.’ A succinct account is all that we need, with the chief points of semantic contrast noted and the usage well illustrated.

wink (verb)‘close and open one eye, suggesting a meaning’

In modern usage, the wink is always significant, suggesting that the winker is aware of a secret, a joke, or some sort of impropriety. Although this usage was possible in Shakespeare’s day (‘I will wink on her to consent’, says Burgundy to Henry, of Princess Katherine, in Henry V, V.ii.301), the usual usage was simply to ‘shut the eyes.’ Without appreciating this, we can read quite the wrong meaning into an utterance. When York advises his friends to ‘wink at the Duke of Suffolk’s insolence’ (Henry VI Part 2, II.ii.70), he is telling them to ignore it, not to connive with it. And when Othello castigates Desdemona for her supposed wrongdoing by saying, ‘Heaven stops the nose at it, and the moon winks’ (Othello, IV.ii.76), we must avoid the modern implication that the matter is not serious.

dear (adjective)‘loved, highly regarded, esteemed’

This word has a range of positive meanings dating back to Old English and all are found in Shakespeare, including some which are no longer current, such as ‘glorious,’ ‘precious,’ or ‘heartfelt.’ But the major problem comes with the word in its negative meanings—‘grievous,’ ‘harsh,’ ‘dire’—that didn’t last much beyond the end of the 18th century. Examples include Hamlet talking about his ‘dearest foe’ (Hamlet, I.ii.182) or Prince Henry reacting to the ‘dear and deep rebuke’ he has received (Henry IV Part 2, IV.v.141). Offences, guilt, exile, peril, groans, and other unwelcome things can all be dear. Usually, the context indicates the right sense but we have to be careful not to be caught off guard. When Romeo realizes who Juliet is (Romeo and Juliet, I.v.118), he exclaims: ‘Is she a Capulet? / O dear account!’ He isn’t calling her a beloved treasure. It’s a harsh reckoning.

naughty (adjective)‘badly behaved’ [of children], ‘improper’ [playfully, of adults], ‘sexually suggestive’ [of objects, words, etc]

Modern English has totally lost the grave implications of the words that were normal in Shakespeare’s day. When Gloucester describes Regan as a ‘naughty lady’ (King Lear3.7.37) or Leonato calls Borachio a ‘naughty man’ (Much Ado About Nothing 5.1.284) we cannot now avoid the impression that these are mild, ‘smack-hand’ rebukes. It is all the more important, therefore, to stress the strong sense the word had in Elizabethan English when referring to people: ‘wicked, evil, vile’. This is especially relevant in contexts where the jocular sense might seem acceptable, as when Falstaff (pretending to be King Henry) calls Prince Hal a ‘ naughty varlet’ (Henry IV Part 1 2.4.420). Concepts—such as the world, the times, and the earth—can also be ‘naughty’ and here too we need to note that the tone is serious not playful, as in Portia’s description of a candle flame in the darkness, ‘So shines a good deed in a naughty world’ (The Merchant of Venice 5.1.91). And where a sexual sense would be relevant, there is always a note of real moral impropriety, as in Elbow’s description of Mistress Overdone’s abode as ‘a naughty house’ (Measure for Measure 2.1.74).

fact (noun)‘actuality, datum of experience’

This word arrived in the language in the 16th century, and quickly developed a range of senses. The one which has survived is ‘actuality,’ but in Early Modern English other senses were more dominant. The neutral idea of ‘something done’ gained both positive and negative associations: a noble thing done or a bad thing done. The pejorative sense was commonest—‘evil deed, wicked deed, crime’—and fact always has this connotation in Shakespeare. Murder, rape, cowardice, and other transgressions are all referred to as ‘facts.’ Gloucester describes the cowardice of Falstaff (the soldier) as an ‘infamous fact'(Henry VI Part 1 IV.i.30). Warwick cannot think of a ‘fouler fact’ than Somerset’s treason (Henry VI Part 2 I.iii.171). The rape of Lucrece is described as a ‘fact’ to be abhorred (The Rape of Lucrece 349). And Lennox describes the way Duncan died as a ‘damned fact’ (Macbeth III.vi.10). The old sense hasn’t entirely disappeared, however. It will still be encountered in a few legal phrases, such as ‘confess the fact.’

temper (noun)‘angry feeling; proneness to anger’

This word has developed its meaning over the centuries, from physical state to mental state to a particular kind of mental state. Today, the ‘anger’ meaning is the dominant one, but this is an 18th-century development and is never found in Shakespeare. The dominant meaning then was ‘frame of mind’—what today we should call ‘temperament.’ When Aufidius says to Coriolanus, ‘You keep a constant temper’ (Coriolanus, V.ii.90), he does not mean that the latter is always cross. Often there is a clue in the associated adjective; for instance, ‘good temper’ (Henry IV Part 2, II.i.79), ‘feeble temper’ (Julius Caesar, I.ii.129), ‘noble temper’ (King John, V.ii.40), ‘comfortable temper’ (Timon of Athens, III.iv.72). The second most common meaning was in relation to swords, which all have a ‘temper’—that is, a desirable quality or condition; ‘Between two blades, which bears the better temper,’ says Warwick (Henry VI Part 1, II.iv.13). Temper for Angelo means ‘self-control'; ‘Never could the strumpet … / Once stir my temper’ (Measure for Measure, II.ii.185). And when Lear says, ‘Keep me in temper’ (King Lear, I.v.44), he means ‘keep me stable.’

A version of this blog post first appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Image Credit: “Name That Shakespeare Play!” by Tracy Lee. CC BY NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Shakespeare’s false friends appeared first on OUPblog.

Lincoln’s eleven greatest speeches

Leaving behind a legacy that transcends generations today, Abraham Lincoln was a veteran when it came to giving speeches. Delivering one of the most quoted speeches in history, Lincoln addressed the nation on a number of other occasions, captivating his audience and paving the way for generations to come. Here is an in-depth look at Lincoln’s eleven greatest speeches, in chronological order.

(1) Speech at Peoria, Illinois, 16 October 1854

Lincoln made an argument against the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the repeal of the Missouri Compromise. He spoke for three hours, and offered a relentless assault upon the logic and morality of slavery: “If the negro is a man, why then my ancient faith teaches me that ‘all men are created equal'; and that there can be no moral right in connection with one man’s making a slave of another.” Five years later, in a campaign autobiography, he declared, “I was losing interest in politics, when the repeal of the Missouri Compromise aroused me again. What I have done since then is pretty well known.”

(2) Speech at Springfield, Illinois, 16 June 1858

Lincoln gave the speech after being nominated by the Republican Party as candidate for Senator of Illinois. He would lose the contest to Stephen Douglas, but not before making himself into a notable national political figure. Famously he declared, “’A house divided against itself cannot stand.’ I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other.”

(3) Speech at New York City, 27 February 1860

Lincoln came east to give what he knew would be a major address at the Cooper Institute. In the speech, he presented his research to argue that Congress had the power to prohibit slavery in the territories and that Southerners, not Northerners, were the ones who, in advocating secession, had rejected the policies of the Founding Fathers. He ended with a rousing message to his fellow Republicans: “Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.”

(4) Speech at Springfield, Illinois, 11 February 1861

Elected to the Presidency, Lincoln faced an unprecedented crisis as he prepared to leave Springfield for his inauguration. Seven states had seceded and it appeared as if the Union was to be dissolved. In what is known as his farewell address, he spoke at the railroad depot to those gathered to send him off. Here are his remarks, as finalized after the train pulled away:

“My friends — No one, not in my situation, can appreciate my feeling of sadness at this parting. To this place, and the kindness of these people, I owe every thing. Here I have lived a quarter of a century, and have passed from a young to an old man. Here my children have been born, and one is buried. I now leave, not knowing when, or whether ever, I may return, with a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington. Without the assistance of the Divine Being who ever attended him, I cannot succeed. With that assistance I cannot fail. Trusting in Him who can go with me, and remain with you and be everywhere for good, let us confidently hope that all will yet be well. To His care commending you, as I hope in your prayers you will commend me, I bid you an affectionate farewell.”

(5) Speech at Washington, D.C., 4 March 1861

No inaugural address has ever been delivered under more trying circumstances. Lincoln explained why he would never accept the legality of secession, tried to reassure Confederates that they had nothing to fear from his Presidency, and yet made clear that while he would not provoke a fight he would defend the Union. In his final appeal he moved from policy to poetry:

“I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”

(6) Speech written as a letter to James C. Conkling, dated 26 August 1863, and delivered by I.J. Ketchum in Springfield, Illinois, 3 September 1863

Invited to speak at a rally of Union men in Springfield, Lincoln explained he could not attend but instead sent a letter. He instructed James C. Conkling, former mayor of Springfield, to “read it very slowly.” Lincoln offered a robust defense of the Emancipation Proclamation that he had issued on 1 January 1863 and which included a provision for the enrollment of black troops. In the aftermath of Gettysburg and Vicksburg, Lincoln had peace on his mind and he gazed into the future:

“Peace does not appear so distant as it did. I hope it will come soon, and come to stay; and so come as to be worth the keeping in all future time. It will then have been proved that, among free men, there can be no successful appeal from the ballot to the bullet; and that they who take such appeal are sure to lose their case, and pay the cost. And then, there will be some black men who can remember that, with silent tongue, and clenched teeth, and steady eye, and well-poised bayonet, they have helped mankind on to this great consummation; while, I fear, there will be some white ones, unable to forget that, with malignant heart, and deceitful speech, they have strove to hinder it.”

(7) Speech at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, 19 November 1863

Commentary unnecessary. Just read it again:

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

“Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

“But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

(8) Speech at Baltimore, Maryland, 18 April 1864

During his presidency, Lincoln delivered only three speeches outside of Washington. The first was at Gettysburg. Baltimore was the second. The third would come in Philadelphia two months later. In both Baltimore and Philadelphia he spoke at Sanitary Fairs, events organized to raise money to support the troops. When the war began, Union troops were assaulted passing through Baltimore; now the President spoke there. “The world moves,” Lincoln observed as he offered a striking analogy to explain different understandings of liberty:

“The shepherd drives the wolf from the sheep’s throat, for which the sheep thanks the shepherd as a liberator, while the wolf denounces him for the same act as the destroyer of liberty, especially as the sheep was a black one. Plainly the sheep and the wolf are not agreed upon a definition of the word liberty; and precisely the same difference prevails to-day among us human creatures, even in the North, and all professing to love liberty. Hence we behold the processes by which thousands are daily passing from under the yoke of bondage, hailed by some as the advance of liberty, and bewailed by others as the destruction of all liberty. Recently, as it seems, the people of Maryland have been doing something to define liberty; and thanks to them that, in what they have done, the wolf’s dictionary, has been repudiated.”

(9) Speech at Washington, D.C., 10 November 1864

Lincoln feared he would not be reelected, but when he was overwhelmingly returned for a second term he took the time to offer more than a few spontaneous remarks. He used the occasion to discuss the meaning of democracy:

“We can not have free government without elections; and if the rebellion could force us to forego, or postpone a national election, it might fairly claim to have already conquered and ruined us…. Human-nature will not change. In any future great national trial, compared with the men of this, we shall have as weak, and as strong; as silly and as wise; as bad and good. Let us, therefore, study the incidents of this, as philosophy to learn wisdom from, and none of them as wrongs to be revenged.”

Abraham Lincoln giving his second Inaugural Address. Photo by Alexander Gardner. Public domain. Library of Congress.

Abraham Lincoln giving his second Inaugural Address. Photo by Alexander Gardner. Public domain. Library of Congress. (10) Speech at Washington, D.C., 4 March 1865

The second inaugural has received nearly as much attention at the Gettysburg Address. As evidenced from his reelection speech, Lincoln had revenge and mercy on his mind. In the second inaugural, Lincoln spoke of the reasons for the war, which was now winding its way toward Union victory. He also spoke about God and Christian forgiveness: “Let us judge not that we not be judged,” he intoned. The closing is as fine as anything he ever wrote or spoke:

“With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

(11) Speech at Washington, D.C., 11 April 1865

Lincoln waited two days after the surrender at Appomattox to speak. He wrote the first two paragraphs that day and drew for the rest of the speech on material he had written two months earlier in support of the readmission of Louisiana, which had adopted a new state constitutions that abolished slavery. He opened, “we meet this evening, not in sorrow, but in gladness of heart.” It was classic Lincoln. Modest, reserved, even in victory. “Not in sorrow.” Lincoln had known so much of it in his life and throughout the war. “Gladness of heart” was something quite different from happiness. Lincoln looked ahead to the reconstruction of the nation, but it would take place without his wisdom and guidance.

Featured Image: Lincoln Memorial. Photo by Jeff Kubina. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post Lincoln’s eleven greatest speeches appeared first on OUPblog.

What evidence should be used to make decisions about health interventions?

When making decisions about health interventions in whole populations, many people believe that the best evidence comes from analysis of the results of randomized control trials (RCTs). This belief is reinforced by the notion of a hierarchy of evidence in which the RCT is close to the pinnacle of evidence. It has that position because the RCT is a powerful tool for eliminating bias. Through randomization and careful following of protocols, the likelihood that an observed effect in a study group compared to a control group is due solely to the intervention rather than some other factor is greatly increased.

My colleagues and I agree that the RCT is the best form of evidence to use when making decisions about new drugs and technologies. However, there are often circumstances when a robust scientific decision can be made about the benefit of an intervention without the use of RCTs. This is very important when considering public health interventions because there are few RCTs of public health interventions on which to base decisions.

The crux of this idea is that you need a RCT only when you are in doubt that an intervention will produce a net benefit. Consider, for example, a new drug that has been tested and considered safe to trial in humans. You can’t know beyond reasonable doubt that this new drug does not cause harm so you need a RCT. The first function of a RCT is to establish with statistical confidence that an intervention is effective i.e. causes benefit rather than harm. Once an RCT has shown that the study group did better than the control group the issue is no longer whether the intervention is effective (causes benefit rather than harm) but whether the intervention is more cost effective than alternatives.

Vegetables by condesign. CC0 via Pixabay.

Vegetables by condesign. CC0 via Pixabay. Now, consider a public health intervention that is highly unlikely to cause harm, for example, one that is about getting one group to have the health behaviour of another group in the population. Such an intervention would be giving families that do not eat many vegetables subsidized vegetables and cooking classes in an attempt to increase their vegetable consumption. We would argue that for this intervention you don’t need RCT evidence because you know beyond reasonable doubt that the intervention does not cause net harm. You know that increased vegetable consumption will improve health, albeit by a tiny amount, and you also know it would be perverse if making vegetables cheaper and inspiring people to use them made their overall diet poorer. Before making a decision about whether to implement the intervention, you do, however, need to consider its cost effectiveness. Are the benefits (increased vegetable consumption) worth the cost (subsidy and cooking class), and could the resource be better spent on an alternative?

Current practice for recommending health interventions tends to treat all interventions as if they were harmful and seeks definitive evidence of effectiveness. When trials do not exist, current practice often declares a lack of conclusive evidence of effectiveness and this acts as a huge barrier to implementation. This means that many cheap potentially cost effective interventions are disregarded not because they don’t work, but because there are no trials able to statistically demonstrate their benefit. What is missing in this process is the correct use of theory. In many cases where there is an absence of good trials, theory and causal models can be used to establish beyond reasonable doubt that a public health intervention does not cause harm. Our proposed approach is to consider all relevant evidence, including theory, in a transparent process that aims to reduce doubt about whether an intervention causes net harm. If we do this we can uncover many harmless cheap interventions which have important benefits at the whole population level and implement those that are found to be cost effective.

Heading image: Test tubes by PublicDomainImages. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post What evidence should be used to make decisions about health interventions? appeared first on OUPblog.

Diversity in policing, really?

There have been lots of recent debates, both in the police service and in the news, about the importance of having a diverse workforce. What does that really mean?

Senior leaders in policing have called for police forces to positively discriminate in favour of black and ethnic minority officers (BME) in the face of a growing diversity crisis. Nationally, 14% of the population is from black and multi-ethnic communities, compared with 5% of police officers. Only 10% of Metropolitan Police officers are from an ethnic minority population, compared with 55% of Londoners. In November 2013, the government issued guidance to police forces to encourage them to use “positive action” to address their lack of race diversity. It is my view that positive action will not solve the lack of BME officers and staff in the police service: this would be short term solution to a long term problem.

Some initiatives that have been talked about to increase diversity in policing include:

Direct Entry: An 18-month course where management staff from a diverse range of backgrounds are trained to be police leaders, entering the force at Superintendent level Fast Track: A programme allowing serving constables to progress to inspector level over three years, a process that usually takes around eight years BME Progression 2018 Programme: A national programme led by the College of Policing, aiming to improve the recruitment, development, progression, and retention of officers and staff from BME backgroundsWhilst there might be a flurry of activity to address this issue, these initiatives are short term, reactive, and – in this current climate of austerity – will not be sustained.

In my opinion, the police service is not dealing with the real issues about the lack of race diversity within the police service. So let’s talk about race with regards to positive discrimination and positive action. What does that truly meas for BME offices and staff in the police service?

There is often a lack of understanding about the difference between positive discrimination and positive action. Because of this, BME officers and staff have to deal with the backlash from their peers who think that they are getting preferential treatment: misunderstanding discrimination for action. There have been accusations about lowering standards to allow progression for BME officers and staff and, most importantly, racial bias. There is a resistance in the police service to having meaningful engagement and involvement with BME staff support associations such as the National Black Police Association and local Black Police Associations.

It has already been voiced by senior officers that there is an operational need for a more diverse workforce. If the police service needs victims to report crime, witnesses to prosecute criminals, and for BME communities to have trust and confidence in the police service, and if we are to truly have a diverse workforce, then we need to have a grown up conversation about race.

Let’s talk about race.

Headline Image Credit: “Rainbow Paper Chain People” by Emily Barney. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Diversity in policing, really? appeared first on OUPblog.

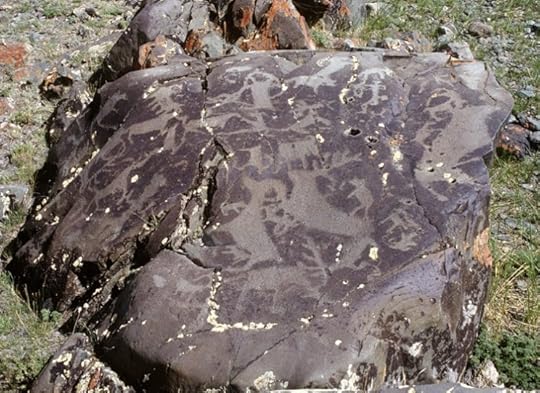

Animal Mother, Mother of Animals, Guardian of the Road to the Land of the Dead

We were working in Baga Oigor II when I heard my husband yelling from above, “Esther, get up here, fast!” Thinking he had seen some wild animal on a high ridge, I scrambled up the slope. There, at the back of a protected terrace marked by old stone mounds was a huge boulder covered with hundreds of images. Within that maze of elements I could distinguish a hunting scene and several square patterns suggesting the outlines of dwellings. The most remarkable scene, on the left half of the boulder, included several profile elk and frontal birthing figures. Stylized, crude, this pairing of stags and female figures rendered me speechless. In one moment a rough boulder had crystalized and drawn together so many of the tropes I had earlier noted in this and other rock art complexes of the Altai—hunters and animals suggesting the bounty of nature, malevolent wolves, the signs of home and well-being, and most importantly an essential connection between birthing women and wild animals. This boulder became the lynchpin in an inquiry in which I may have been the discoverer — but which actually taught me how to look and think about the archaeology of belief.

Our project was located in northwestern Mongolia where the Altai Mountains spill over into Russia and China. In that vast and seemingly empty landscape we discovered huge repositories of ancient rock art and surface monuments dating back to the Bronze Age and earlier, virtually all unknown to any but local herders. Our ostensible purpose was to survey, record, and document this material. But gnawing at me always was the question, is it possible to see a pattern in the complicated procession of cultural tropes and periods? How do the images and surface monuments relate, finally, to the immense landscape in which they have survived for thousands of years? And how does one begin to reconstruct the lives and beliefs of ancient cultures in the absence of written texts?

By the time we discovered the boulder at Baga Oigor II, I was already familiar with massive stones from the Minusinsk Basin, carved with the masks of horned animals, the jaws of ferocious beasts, and female breasts. I had earlier been drawn to the pecked images of female moose, striding above the rivers of the Siberian taiga, and to bird-women from Kalbak-Tash. These strange beings—so often of a distinctly female character—as well as standing stones, great mounds and elaborate altars, suggested a cultural river that flowed over a vast region of northern Asia, its currents shifting with space and time. This land of rivers, taiga, and steppe had been populated by prehistoric hunters and herders over thousands of years. They moved through forests following wild animals, fished in cold rivers, or drove their animals from lowland to highland pastures in a regular seasonal rhythm. Some of these people left behind poor burials and settlement sites; most seem to have disappeared without a trace within a land that until the twentieth century seemed empty, without visible human roots, deeply impressive and strangely silent.

But that appearance of emptiness is misleading. From as early as 11,000 years before the present, within this vast and harsh landscape people were erecting monumental stones and mounds and recording their world, their ways of life, their spirit figures, and heroic narratives in stone-pecked imagery. These are the materials I gathered over a period of twenty years of fieldwork; they are the texts to which I turned in order to understand the human, expressive life of ancient North Asia.

Over time I began to discern the outlines of a mythic narrative of birth, death, and transformation generated by the realities of ancient hunters’ and herders’ lives. Of the central protagonists, we have tended to privilege the hero hunter of the Bronze Age and his re-incarnation as a warrior in the Iron Age. But before him and, in a sense, behind him was a female power, half animal, half human. She was the source of life and death, the guardian of the road to the lands of the dead. From her came permission to hunt the animals of the taiga, and by her they were replenished. She was the source of the hunter’s success and thus the mainstay of a peoples’ existence. Within this tale, the stag was a latecomer, a complex symbol of death and transformation embedded in what ultimately became a struggle for priority between female deity and hero hunter.

My approach is rooted in the conviction that human expression is shaped by ecological processes in its emergence, development, and disappearance. Viewed within integrated compositions, set within postural and spatial indications of action and response, the changing details of pecked imagery reflect dynamically shifting constructs in the way people oriented themselves to each other, to their past, and to their physical world. No less important is the location of monuments in their landscapes: their immediate placement, their orientation, and what they “see” from their site. With time it became clear that this magnificent but somehow mute material had to be considered in ecological terms, where change in one area shifts the interrelationships of the constituent parts and their basic signification.

This study has required a wide-ranging inquiry into the visual material itself—both excavated and found in situ; into the region’s paleoenvironment, social economy, and social order. It has necessitated an investigation into the mythic beliefs and shamanic practices of Paleo-Siberian and Tungusic groups whose origins go back to the Sayan and Altai regions in the Bronze Age. Within these beliefs and practices can be found signs of patterns that parallel and lend credence to what we perceive within the ancient rock art and standing stones.

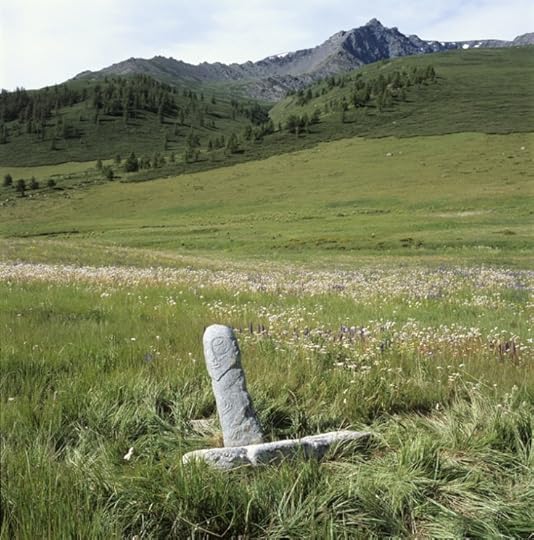

1. View southwest over steppe of Baga Oigor Gol, Bayan Ölgiy aimag, Mongolia. Photo: Gary Tepfer.

1. View southwest over steppe of Baga Oigor Gol, Bayan Ölgiy aimag, Mongolia. Photo: Gary Tepfer.  2. Boulder with hunting scenes, dwellings, stags, and birthing women. Late Bronze Age. Baga Oigor II, Bayan Ölgiy aimag, Mongolia. Photo: Gary Tepfer.

2. Boulder with hunting scenes, dwellings, stags, and birthing women. Late Bronze Age. Baga Oigor II, Bayan Ölgiy aimag, Mongolia. Photo: Gary Tepfer.  3. Tavan Bogd and the Potanin Glacier at the juncture of Mongolia, Russia, and China. Photo: Gary Tepfer.

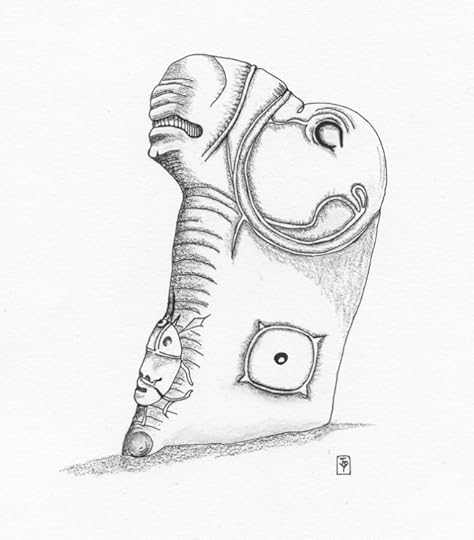

3. Tavan Bogd and the Potanin Glacier at the juncture of Mongolia, Russia, and China. Photo: Gary Tepfer.  4. Monolith with ram head, female mask, and breasts. Verkh-Bidzhin, Ust’-Abakan Region, Khakassia, Russia. Red sandstone, 150 x 55 x 32 cm. Drawing: L.-M. Kara, after Kyzlasov 1986.

4. Monolith with ram head, female mask, and breasts. Verkh-Bidzhin, Ust’-Abakan Region, Khakassia, Russia. Red sandstone, 150 x 55 x 32 cm. Drawing: L.-M. Kara, after Kyzlasov 1986.  5. Bird-woman with raised arms. Petroglyph, approximately 30 cm. Kalbak-Tash, Altai Republic, Russia. Drawing L.-M. Kara, after Kubarev and Jacobson 1996.

5. Bird-woman with raised arms. Petroglyph, approximately 30 cm. Kalbak-Tash, Altai Republic, Russia. Drawing L.-M. Kara, after Kubarev and Jacobson 1996.  6. Deer stones seen from north to south. Tsagaan Asgaat, Bayan Ölgiy aimag, Mongolia. Photo: Gary Tepfer.

6. Deer stones seen from north to south. Tsagaan Asgaat, Bayan Ölgiy aimag, Mongolia. Photo: Gary Tepfer.  7. Khirigsuur with stone altars on the south side. View to the north. Bronze Age. Dood Khalga, Bayan Ölgiy aimag, Mongolia. Photo: Gary Tepfer.

7. Khirigsuur with stone altars on the south side. View to the north. Bronze Age. Dood Khalga, Bayan Ölgiy aimag, Mongolia. Photo: Gary Tepfer.  8. Boulder covered with animals, hunters, and a frontal birthing woman (left side). Bronze Age. Tsagaan Salaa IV, Bayan Ölgiy aimag, Mongolia. Photo: Gary Tepfer.

8. Boulder covered with animals, hunters, and a frontal birthing woman (left side). Bronze Age. Tsagaan Salaa IV, Bayan Ölgiy aimag, Mongolia. Photo: Gary Tepfer.  9. Scene with hunter and frontal woman (lower left) and aurochs or wild yak. Bronze Age. Baga Oigor III. Bayan Ölgiy aimag, Mongolia. Photo: Gary Tepfer.

9. Scene with hunter and frontal woman (lower left) and aurochs or wild yak. Bronze Age. Baga Oigor III. Bayan Ölgiy aimag, Mongolia. Photo: Gary Tepfer.  10. Standing and fallen stone images. Turkic Period. Elt Gol, Bayan Ölgiy aimag, Mongolia. Photo: Gary Tepfer.

10. Standing and fallen stone images. Turkic Period. Elt Gol, Bayan Ölgiy aimag, Mongolia. Photo: Gary Tepfer. Feature Image: Suvarga khairkhan (3) by Jargalsaikhan Dorjnamjil. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Animal Mother, Mother of Animals, Guardian of the Road to the Land of the Dead appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers