Oxford University Press's Blog, page 682

April 1, 2015

Monthly etymology gleanings for March 2014

One should not be too enthusiastic about anything. Wholly overwhelmed by the thought that winter is behind, I forgot to consult the calendar and did not realize that 25 March was the last Wednesday of the month and celebrated the spring equinox instead of providing our readership with the traditional monthly gleanings. To make things worse, while writing about 23 March, I had 23 June (the solstice) in mind and danced around a bonfire three months ahead of time. The first faux pas attracted almost no one’s attention (just one puzzled letter), but the second earned me some well-deserved mockery. The text was at once corrected, which made nonsense of the comments, but even with the help of computers, those wonderful machines that allow us to erase the past, one cannot undo what has been done. To entertain our readers and by way of making amends, I’ll quote a sentence from the beginning of Kipling’s “Elephant’s Child”:

“One fine morning in the middle of the Precession (sic) of the Equinoxes this ’satiable Elephant’s Child asked a new fine question that he had never asked before. He asked, ‘What does the Crocodile have for dinner?’”

In the spirit of following the precession of equinoxes I’ll provide a two course crocodile dinners: next week, another set of “gleanings” will follow this one.

StrawberryOne fine morning a faithful reader of this blog asked: “What is the origin of the word strawberry?” Before enlarging on this much-discussed moribund topic, I would like to quote another passage. It occurs at the end of the preface to Bartlett J. Whiting’s book Proverbs, Sentences, and Proverbial Phrases from English Writings Mainly Before 1500:

“In the third edition (1661) of the Compleat Angler (p. 118) Isaac Walton quotes Dr. Boteler (?William Butler) as having said of strawberries, ‘Doubtlesse (sic) God cou’d have made a better berry, but doubtlesse God never did’.”

Different opinions about the etymology of strawberry crowd out one another on the Internet. A page from my book Word Origins is also there, and I could (cou’d) have confined myself to a brief reference to Google, but I have something new to say in addition to what appears there and will therefore devote some space to the delicious berry.

The double trouble with strawberry is that no other European language has a similar name (one late occurrence in Swedish is of unknown provenance) and that, on the face of it, straw- makes little sense in it. The word goes back to Old English, and there must have been a serious reason for coining it or for changing the traditional denomination (that is, “earth-berry,” which did turn up at that time but, judging by the extant texts, was known very little). One thing is clear: the Germanic invaders of Great Britain did not bring the word strawberry to their new homeland from the continent.

A change reminiscent of the one known from the history of English also occurred in Swedish. Only in that Scandinavian language “earth-berry” was replaced with the obscure name smultron, a regional word, as it seems. The change occurred some time before the beginning of the fifteenth century. Several conjectures about the origin of smultron exist, but none is fully persuasive. I am sure heavy thoughts about etymology never bothered Ingmar Bergman, the producer of Smultronstället, known in English as Wild Strawberries (stället means “the place”).

Absolutely delicious and no straws attached.

Absolutely delicious and no straws attached. If we disregard Friedrich Kluge’s idea, which is wilder than wild strawberries, that straw- is related to Latin fragola “strawberry,” we will be left with trying to find out what straw has or had to do with this berry. (The editors of the OED knew the fragola idea and politely rejected it—politely, because scholars of Kluge’s stature have to be treated with deference.) The first element of the English word may have been strew rather than straw, with reference to the propagation by runners; Skeat found this explanation not improbable. Yet it is unlikely that the first element of the name in question was a verb. If straw was ever used in protecting strawberries, this practice would have been important only in gardening, but before naming the garden berry, whose cultivation is late, people gathered strawberries in the wild. Then there are straw-like particles (achenes) that cover the surface of this berry. So straw-like berry? This etymology is hesitatingly favored by the OED. Strawberries are often stringed, that is, collected and threaded on thin straws, another vague clue. It has also been suggested that strawberry is an alternation of strayberry. But what is strayberry? Folk etymology produces transparent words, not new riddles. According to the simplest guess known to me, strawberries often grow in grassy places and hayfileds. A tiny piece of evidence in support of this hypothesis is the fact that Swedish smultron first occurred in the compound smultronagræs around the year 1400.

We can see that the question remains open. After the publication of my book (all the suggestions listed above, except those related to Swedish, are listed there), a new work on this vexed subject appeared. It can be downloaded from the Internet (William Sayers, “The Etymology of strawberry”: Moderna språk 2009, 15-18). Most of the paper purports to show that all the previous suggestions are wrong (this is of course why scholarly papers are written). The author’s solution runs as follows:

“The most plausible origin for strawberry in its earliest reference to the Woodland Strawberry is as a name for plants growing at ground level (like straw spread as litter) irregularly distributed as the result of the spread of achenes by birds and animals—two interrelated senses of being strewn (this development was proposed by Leonard Bloomfield [in his book Language, pp. 433-434], who did not, however, recognize its exclusive relevance to the Woodland Strawberry). So reading the initial element of the compound then returns English strawberry to the Germanic fold as a variant on the ‘earth-berry’ designation.”

There is one thing that bothers me. If strawberry means approximately “earth-berry,” why did people go to the trouble of calling it something else, seeing that the most natural name (earth-berry) was available and widely known? So here we are: a delicious fruit and a troublesome word.

Can anything be higher? Still in Scandinavia

Can anything be higher? Still in Scandinavia A correspondent remembered his father’s saying ish varda when he dealt with something very unpleasant. He asks what varda, which he believes to be a Scandinavian adjective, means. I suspect that varda is Norwegian var da, not an adjective but a verb followed by an exclamation. The whole seems to mean “ish was there.” Da also occurs in the “famous” uff da, used for the same purpose as the phrase quoted by our correspondent (see it in the last volume of Dictionary of American Regional English, where a special entry is devoted to it). Ish probably needs no comment; ish var da must have meant “disgusting was it.”

Uppsala: the origin of the nameI don’t think there is a problem. The earliest Uppsala, first mentioned in historical documents in the tenth century, was known to the skalds, who used the name in the plural (Uppsalir). Uppsala turns up in so-called legendary sagas. The place designated a town or a group of houses “up there,” as opposed to an older place called Sala.

Much more next week.

Image credits: (1) Chocolate-Coated Strawberries. Photo by Garry Knight. CC BY 2.0 via garryknight Flickr. (2) Cold spring day in Uppsala, Sweden. Photo by Alexander Cahlenstein. CC BY 2.0 via tusken91 Flickr.

The post Monthly etymology gleanings for March 2014 appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford World’s Classics Reading Group Season 2: Dracula

‘It was butcher work…the horrid screeching as the stake drove home; the plunging of writhing form, and lips of bloody foam…’

— Bram Stoker, Dracula

Tales of vampire-like creatures, demonic consumers of human flesh and blood, have permeated the mythology of almost every culture since the dawn of time. Yet, while the vampire as we now know him became a popular source of folklore terror in Eastern Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries, it was not until 1897 that Bram Stoker introduced the world to the most famous vampire of all.

Tales of vampire-like creatures, demonic consumers of human flesh and blood, have permeated the mythology of almost every culture since the dawn of time. Yet, while the vampire as we now know him became a popular source of folklore terror in Eastern Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries, it was not until 1897 that Bram Stoker introduced the world to the most famous vampire of all.

Count Dracula is an ancient creature bent on bringing his contagion right to the heart of the British Empire: London. As the cunning and supernatural powers of the Count and his legions threaten destruction upon the city, only a handful of men and women stand between Dracula and his long-cherished goal. As the horrifying story unfolds in the diaries and letters of young Jonathan Harker, Lucy, Mina, and Dr Seward, Dracula will be victorious unless his nemesis Professor Van Helsing can persuade them that monsters still lurk in the era of electric light.

After a wonderful time exploring Wuthering Heights, culminating in a Reddit AMA with Professor Helen Small at the end of March, we would love to invite you to join us as we dive into the dark Gothic landscape of Victorian London, and seek to defeat the most terrifying and crafty horror of them all…

Our resident expert for this season of the Oxford World’s Classics Reading Group will be Roger Luckhurst, editor of the OWC edition of Dracula and professor in Modern and Contemporary Literature. He teaches horror and the occasional respectable novel by Henry James at Birkbeck College, University of London and tweets at @TheProfRog.

You can follow along, and join in the conversation by following us on Twitter and Facebook, and by using the hashtag #OWCreads.

Image: Ruins by ehrendreich. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Oxford World’s Classics Reading Group Season 2: Dracula appeared first on OUPblog.

The importance of antimicrobial stewardship

What is antimicrobial stewardship?

Antimicrobial stewardship refers to the judicious use of antibiotics. Since 2007, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) has recommended that all hospitals implement formal antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs), which should consist of an infectious diseases physician and a pharmacist with training in infectious diseases. The ultimate goal of such programs is to make sure patients receive the medicines they need, while at the same time reducing the side effects and costs associated with unnecessary antibiotic prescribing.

Specific elements of antimicrobial stewardship include:

Limiting inappropriate use of antibiotics. Making sure patients receive the correct dose of an antibiotic, based on the specific infection being treated, as well as the patient’s age, weight and underlying medical conditions. Knowing when antibiotics need to be given through an IV and when it is safe to give them by mouth. Knowing which conditions require long courses of antibiotics and which can be treated with shorter courses.Why is antimicrobial stewardship important?

Worldwide, the number of infections due to antibiotic-resistant bacteria is increasing. According to the CDC, there are 23,000 deaths and two million hospitalizations attributable to drug-resistant bacteria each year in the United States. At the same time, the number of new antibiotics is dwindling. In this context, it is crucial to use our existing armamentarium appropriately. The challenge of antimicrobial stewardship is to eliminate unnecessary antibiotic use while recognizing when broad spectrum antibiotics are truly needed. It is well documented that exposure to antibiotics is associated with the development of resistance. This is especially the case of healthcare-acquired infections, which occur in patients more likely to be exposed to antibiotics. Extended courses of antibiotic therapy are also more likely to lead to resistance.

US Navy Project Hope nurse listens to a child’s heartbeat while taking her vital signs. US Navy photo by Photographer’s Mate 2nd Class Erika N. Jones. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

US Navy Project Hope nurse listens to a child’s heartbeat while taking her vital signs. US Navy photo by Photographer’s Mate 2nd Class Erika N. Jones. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. While antimicrobial stewardship first began at adult hospitals, there is plenty of antibiotic use among pediatric patients. For instance, more than 60% of patients admitted to children’s hospitals receive at least one antibiotic prescription, with much higher rates in children admitted to intensive care units or undergoing surgery. At the same time there, more than 49 million children receive an outpatient prescription for an antibiotic each year; about half of these are for broad-spectrum antibiotics.

How many institutions have formal antibiotic stewardship programs, and what do we know about their impact?

The number of pediatric ASPs is growing. A recent survey conducted among 38 member hospitals of the Children’s Hospital Association found that 16 had a formal ASP and 22 did not; however, 15 were planning to implement a program and most hospitals without formal ASPs were still engaged in some sort of stewardship activities. One recently published study compared antimicrobial use in children’s hospitals with formal ASPs to use in hospitals without ASPs. The authors found that antimicrobial use decreased at all study hospitals after the publication of the IDSA guidelines in 2007, but this decrease was more pronounced in hospitals with ASPs. Decreases in three specific broad-spectrum antibiotics — vancomycin, carbapenems, and linezolid — were also more pronounced in hospitals with formal ASPs.

Where should we go from here?

As noted in our recently published systematic review, there is evidence that pediatric ASPs can reduce antimicrobial utilization, antimicrobial drug costs and prescribing errors. More research needs to be done looking at the impact of antimicrobial stewardship on other outcomes such as length of stay and improved clinical outcomes.

More importantly, the practice of antimicrobial stewardship needs to grow outside of the hospital setting. It is important for physicians to remember that antibiotics do have side effects — most commonly rash and diarrhea — and that misuse may contribute to resistance. It is also important to educate patients and their families that antibiotics are not needed for every fever. For instance, antibiotics are not effective for common conditions such as runny nose, non-specific cough illnesses, and sore throat (except for strep throat).

Heading image: Clindamycin by angela_sleeping. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The importance of antimicrobial stewardship appeared first on OUPblog.

Fool’s gold and the founding of the United States of America

“When the legend becomes fact, print the legend,” the hard-bitten newspaperman, Maxwell Scott says to Ransom Stoddard in the classic western film, The Man Who Shot Liberty Vallance. So many legends have been attached to the founding of the United States it is sometimes difficult to see through the haze of myths to the real beginnings. A number of direct predecessors to the nation are often sought through the activities of predominantly English-speaking settlers on the eastern seaboard. This is popularly recounted annually in the Thanksgiving Festival, of course, which celebrates the survival of a group of religious refugees who traveled on the Mayflower to New England in 1620. However, by the time they arrived a colony further to the south, at Jamestown, was already well-established and Virginia was within four years of formally achieving statehood in the form of recognition as a crown colony. In fact, the Mayflower pilgrims were aiming originally to join the Jamestown settlers but were blown off course.

The founding of Jamestown had much to do with fool’s gold, the common term for the glittering, golden, sulfide of iron mineral, pyrite. In fact, fool’s gold is a common thread linking the activities of all the early European explorers to North America. In each case, these pioneers shipped back tons of fool’s gold to Europe in more-or-less successful attempts to raise funding for further expeditions. Jacques Cartier led an expedition into Canada in 1536 and sent back “diamonds and gold” to France, which turned out to be quartz and fool’s gold, in a successful attempt to persuade King Francis I to fund further expeditions. Groups of merchant adventurers in London were encouraged by Queen Elizabeth I’s government to look for gold in the Americas, following the success of the Spanish conquistadors further south and the rumors of French successes further north. Martin Frobisher led an expedition in 1576 to the Arctic coast of Canada that involved a successful financial scam whereby hundreds of tons of pyrite, shipped back to England, were promoted as gold by a gang of highly-placed fraudsters. Walter Raleigh funded an expedition that established the now lost colony of Roanoke in the Carolinas in 1584. We know they were looking for gold since they had Joachim Gans, a distinguished Bohemian metallurgist on board and his goldsmith’s crucible has been found amongst the archaeological remains at the site, together with lumps of smelted copper ore.

Sir Walter Raleigh, pictured above, funded the 1584 expedition to found a colony in Roanoke. Many of the American colonies were founded in the pursuit of finding gold, and this colony was likely no exception since Joachim Gans — a skilled metallurgist — accompanied the trek to the Carolinas. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Sir Walter Raleigh, pictured above, funded the 1584 expedition to found a colony in Roanoke. Many of the American colonies were founded in the pursuit of finding gold, and this colony was likely no exception since Joachim Gans — a skilled metallurgist — accompanied the trek to the Carolinas. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. None of these early fool’s gold-fueled expeditions managed to establish a permanent settlement and even Cartier’s legacy at Charlesbourg-Royal on the St Lawrence River was abandoned in 1643. The first permanent European colony on the Atlantic seaboard was established by the Virginia Company at Jamestown in 1607 with a specific remit to look for gold. The captain of the first expeditionary fleet, Christopher Newport, was so sure that gold was to be found that he insisted that pyrite found near the settlement was real gold and shipped a load back to England. The idea was to encourage more immigrants to journey to the colony with the promise of gold — a sort of Elizabethan version of a 19th century gold rush. The puff achieved its aims; the rumor of gold was sufficient to lure more settlers. Captain Newport returned to Jamestown in 1608 with more settlers and the Jamestown settlement was established (in the sense that more people arrived than had died). It was after the Civil War, when the northern settlement in Massachusetts was written up by the victorious Union hagiographers, that the legend of a group of far-seeing and devout pilgrims became fact and they — rather than those duped by false promises offered by fool’s gold — became the Founding Fathers.

The idea that this great nation was founded on fool’s gold may seem particularly appropriate today. The recent financial crisis unearthed some really unpleasant financial verities about the richest nation on Earth. For example, one giant US finance house announced a loss of nine billion dollars on derivative trading in just one month in 2012. They essentially acted as bookmakers, spreading risks to other banks in a win-win situation – as long as the values of the primary assets (the houses) did not collapse. The operation has all the characteristics we associate with the idea of fool’s gold: a worthless asset believed by some people to be of real value. To put this in perspective, this one institution has some 70 trillion dollars tied up in derivatives, which is a banker’s way of saying that it’s 70 trillion dollars in debt. This amount of money is larger than the total global economy. It is extraordinary to think that the amount of money owed by just one US company is greater than all the money in the world.

The idea of a false certainty that is expressed in the term fool’s gold seems to be very appropriate today. April 1, All Fool’s Day, should be celebrated by all Americans.

Feature Image: Pyrite crystals. Photo by JJ Harrison, CC BY SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Fool’s gold and the founding of the United States of America appeared first on OUPblog.

DNA, colour perception, and ‘The Dress’

Did you see ‘blue and black’ or ‘white and gold’? Or did you miss the ‘dress-capade’ that exploded the Internet last month? It was started by this post on Tumblr that went viral.

Many people warned their heads risked exploding in disbelief. How could people see the same dress in different colours?

It appears the variation lies in the way we judge how light reflects off objects of different colours, as Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker explained in Forbes.

A follow-on, calmer discussion started about whether this trait could be in our DNA.

Michael Whitehead made an open call for 23andMe, the consumer genetics company, to test whether DNA might be responsible.

Giovanni Marco Dall’Olio opened a (private) thread inside the 23andMe discussion forum directly asking for users to record what they saw. At last check, more than 500 people had posted responses.

Indeed, 23andMe did launch an online survey.

This prompted discussions started by Carl Zimmer on Twitter. One scientist reported she saw ‘blue and black’ while her son saw ‘white and gold’. Another saw ‘blue and black’ while his identical twin saw ‘white and gold’.

Pinker said his intuition was that it was not genetic, but he’d be keen to see the data.

The first question to answer is this debate is whether the trait is heritable.

Darwin knew about inheritance, but not its mechanism. It wouldn’t be until the turn of the 20th century that Mendel’s experiments with sweet peas led to an understanding of how inheritance works and until the Avery-MacLeod-McCarty (1944) before it was known that genes resided in our DNA, the structure of which was cracked by Watson and Crick (1953) opening up the era of molecular biology.

Genomes aren’t needed to ask if a trait is heritable – just information from pedigrees. With his advanced undergraduate class in genetics, Steve Mount analyzed data crowdsourced from 28 families which showed no trend for the perceptions of parents to predict those of their children. The data did show some tendency for daughters to see the dress as fathers. Mount’s conclusion was that the trait can’t be strictly genetic, but could have an X-linked genetic component.

“[The Dress] marks a turning point in our thinking about how society can mobilize genomic data.”

23andMe then released the results of their far larger study as a blog article and a more detailed whitepaper. Amazingly, in a few short days, 23andMe had convinced more than 25,000 of their customers to complete #TheDress survey. Their data confirmed the lack of any clear genetic link with colour perceptions of the dress. Yet, it did reveal a potential association with a variant of the gene ANO6, a gene in the same family as ANO2, which is involved in light perception that might be significant in a larger sample size.

Rather than being down to DNA, the strongest determinant was age followed by where you grew up. You are more likely to see ‘white and gold’ as you approach the age of 60. Those who grew up in more urban areas also saw ‘white and gold’ in higher proportions.

23andMe suggest this work warrants further study, especially as it underlines the complex interactions of genetics and environment (the Nature versus Nuture debate).

The lasting significance of this wonderfully geeky chapter of ‘the dress’ debate is how quickly data was leveraged to sate scientific curiosity. A question was posed and answered in short order. It marks a turning point in our thinking about how society can mobilize genomic data. Cached data is just waiting to have questions asked of it; 23andMe have more than 900,000 customer DNA profiles to hand, 80 percent of whom consent to participate in research such as this survey.

Dall’Olio wrote in his 23andMe post that “if we are fast and we collect a good number of answers, this can be the fastest discovery of association between a trait and its genotype in the history of genetics”. His comment was prescient.

The catch is combining the DNA with information about individuals. Who knew to ask people before-hand when they signed up what colour that dress was? Absurd to think anyone ever would.

Another issue is that 23andMe examines a significant proportion of the variation in the human gene pool but not ‘the entire genome’. There could be genetic variation for particular traits that go undetected.

In an ideal scenario, the perfect genetic study of a heritable trait would involve a large cohort of individuals with Trait A and Trait B and the use whole genome sequencing. But no one would fund such a ‘Dress DNA’ study. Curing cancer is far higher up the priorities list. Thus, existing databases of millions of genomes open up new possibilities for discoveries that might otherwise never be made.

A current roadblock lying on the path towards this emerging vision of true ‘community genomics’ where the curious public can mine our collective DNA, is that only 23andMe have access to customer profiles. 23andMe contribute to peer-reviewed papers and have numerous academic collaborations, but beyond these agreed uses of their data, scientists and the general public alike can only play on the sidelines.

What if such data were opened up? Everyone, has access to data contributed to the openSNP genome sharing platform. The catch with openSNP is that the number of people willing to make their DNA public is still small, but growing.

Whitehead created a survey for the phenotype for perception of ‘The Dress’. The first user to record his phenotype was Bastian Greshake, the creator of the openSNP platform. Appropriately, the growing list of users is split on ‘blue and black’ and ‘white and gold’.

Feature image credit: Colours in paper, by Soorelis. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post DNA, colour perception, and ‘The Dress’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Tax facts

As long as rulers have needed money for the military, public works, or just to enrich themselves, they have relied on taxes. As Americans approach the dreaded April 15 income tax-filing deadline, it is worth considering some key facts about taxation.

There are many different modes of taxation: individual income taxes, corporate profits taxes, capital gains taxes, property taxes, inheritance taxes, sales taxes, social insurance taxes, taxes on imports, and a whole host of government-levied fees that look and feel a lot like taxes.

Because they did not have the sort of tax reporting information we have now, ancient bureaucracies put a premium on taxes that were easy to collect and hard to avoid. A head tax—that is, a fixed fee paid by everyone in the community—would have been difficult to dodge since most people living in a community would be known to the authorities. In biblical times, a head tax was collected in conjunction with the census: those who were counted were obliged to pay a half-shekel (Exodus 30:11-16).

Property taxes, such as a tax on real estate, were also a favorite of ancient tax authorities, since the owners of land and buildings were readily identifiable and could only sneak off without paying if they were willing to abandon their property. During the reign of William III, England introduced a tax on windows. Since glass was expensive, this would seem to have been an efficient way of imposing a higher tax on the well-to-do; however, wealthy homeowners who wanted to avoid paying the tax simply reduced the number windows in their homes.

An income tax was first introduced in the United States in 1862, when President Abraham Lincoln signed the Revenue Act into law. The act, which imposed a 3 percent tax on incomes between $600 and $10,000 and a 5 percent tax on incomes of more than $10,000, helped the North meet the high financial cost of the Civil War. After the war ended and the government’s fiscal situation improved, income tax rates were lowered; the tax was repealed in 1872.

President Grover Cleveland reinstated the income tax when he signed the Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act of 1894 into law. The main purpose of the law was to reduce tariffs—at the time, one of the government’s main sources of revenue–and a 2 percent income tax was included in the law to make up for the revenue lost because of lower import duties. The tax was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court the following year on the grounds that the income tax was a “direct tax” and that the Constitution (Article I, section 2) stipulated that direct tax taxes were to be apportioned among the states on the basis of population.

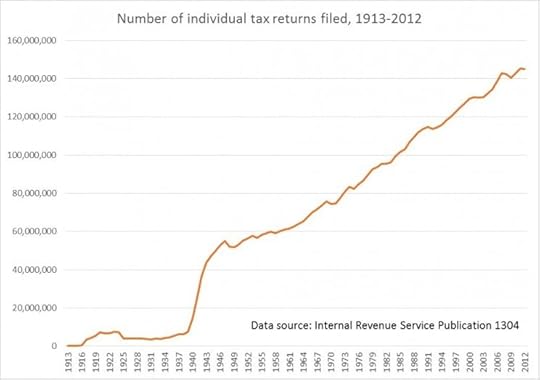

Figure 1, by Richard S. Grossman. Used with permission.

Figure 1, by Richard S. Grossman. Used with permission. The Supreme Court’s objection was overcome by the passage of the 16th amendment in 1913, which exempted the income tax from direct tax provision of the Constitution. In the ensuing tax law, a 1 percent tax was assessed on incomes above $3,000 (probably somewhere between $50,000 and $75,000 in today’s terms, depending on how inflation is calculated) for individuals and $4000 for married couples, with a 6 percent surtax on incomes of more than $500,000 (the equivalent to several million dollars today). During the subsequent century, the tax rate schedule would grow increasingly complex, but the income tax was here to stay.

We can get a sense of the income tax’s pervasiveness by dividing the number of tax returns filed by the total population (since many tax returns covered multiple people, this measure is only a rough approximation). Figure 1 plots the number of tax returns filed since the inception of the income tax. In 1913, 358,000 tax returns were filed—equivalent to less than 0.5 percent of the population. Both tax rates and the number of people subject to the income tax rose dramatically during World War I, as the government used the income tax to help finance the war effort: by 1917, the number of returns filed had increased ten times–to nearly 3.5 million (or about 3.5 percent of the population)—and by 1920, the number of returns filed rose to more than 7 million (nearly 7 percent of the population). With the sharp drop in personal income during the Great Depression, the number of returns filed declined to less than 3.5 million (2.75 percent of the population), before rising dramatically, to approximately 50 million (37.5 percent of the population), by the end of World War II. Today, approximately 144 million tax returns are filed annually, equal to about 45 percent of the population.

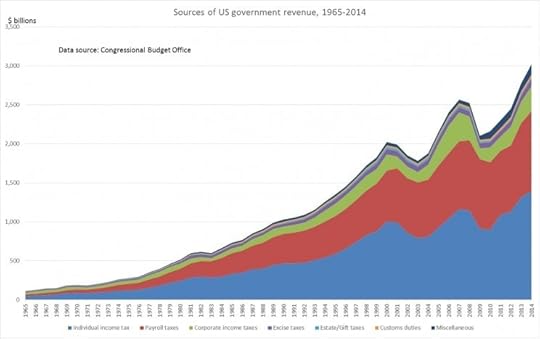

Figure 2, by Richard S. Grossman. Used with permission.

Figure 2, by Richard S. Grossman. Used with permission. As Figure 2 makes clear, the income tax has been—and continues to be—the most important source of revenue for the US government. In 1965, the individual income tax accounted for just under 41 percent of total US government revenue. The percentage has varied between 43 and 49 percent of government revenue, and currently stands at just over 46 percent (payroll taxes come in second, at just under 34 percent).

Finally, it is worth noting that during its century-long history, tax law and income tax forms have grown increasingly complicated. The original 1040 form (you can still read the 1913 version) was three pages long, with one page of instructions. For those of you filing 2014 tax forms, the Form 1040 instruction booklet is more than 100 pages long—and warns the taxpayer that the instructions do not include those for the various schedules. Just how many additional forms do you need to file with your 1040 form? The answer will vary from household to household; however, Form 8885, concerning the health coverage tax credit (and presumably one of the more recently added forms), indicates that it is 134 in the attachment sequence.

Some of the increased complexity of the tax code arises because personal finance is more complicated than it was 100 years ago, and important government programs necessitate additional paperwork. On the other hand, the increasing complexity of tax returns makes it more difficult for citizens to understand who benefits—and who loses—from tax policy. While filling out our tax forms, we should be mindful of the fact that some of this additional complexity may be intentional.

Feature image credit: Abraham Lincoln, by Alexander Hessler. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Tax facts appeared first on OUPblog.

March 31, 2015

A matter of death and life

It is something of a truism to say that “life-styles determine death-styles.” Not only do anthropologists and other scholars see the value of this point, but no less of an authority than Metallica incorporated it into “Frantic” on their 2006 album, St. Anger. Whatever Metallica meant, it is generally understood that if we want to understand a community’s treatment of, and attitude toward, the dead, we should look first to the values and priorities that shape their daily life. We should understand the construction of the dead’s identity by looking at how the living construct their identities. Why did the Egyptians imagine death as a journey to join Amon-Re in his boat? The answer is simple enough: because Egyptian life revolved around the Nile and pharaohs held their processions on boats rather than on land.

In Christian and other religious communities, though, we need to turn this truism on its head. It is just as likely that death-styles determine life-styles. Indeed, it is very often the case that what people think happens during or after death may very deeply affect how they live their lives and, more importantly, how they understand the makeup of their own community. A very basic example is a 2012 study that found a belief in Hell correlates to lower crime rates. This makes sense—if people imagine a punishment in the afterlife, they may try a bit harder to be good in this life. So, rather than death being merely modeled on life, it is equally true that we model life on death.

Among Byzantine Christians and their descendants, the Eastern Orthodox Churches, death impinges on life in some surprising ways. In the compendious Life of Basil the Younger (10th c.), we encounter a particular narrative of judgment that takes place directly after death. In this narrative, some of whose elements have their origins as far back as the Egyptian afterlife myths: the soul, recently ripped from its body, must pass through twenty-one “tollhouses” staffed by demons, whose titles resemble those of Byzantine court officials. Each “tollhouse” is dedicated to a particular sin—anger, gluttony, magic, slander, etc.—and at each one the soul must give an account of its actions in life and pay the associated “toll” in the form of good deeds. If the soul cannot pay, the demons presumably take it to punishment in Hell. This narrative of “tollhouses” offers a vivid albeit very idiosyncratic explanation of “particular judgment”: one that God enacts on an individual soul after its death as opposed to the cosmic judgment God performs at the end of the world.

Generally, Eastern Christian literature uses visions (or even mentions) of particular judgment to exhort readers to a life of virtue and piety. In the face of death that ends physical pleasures, and the judgment that condemns them, people are encouraged to live simply and to cultivate charity and love. The circumstances of judgment matter less than its criteria, which are generally drawn from the New Testament. But with the “Tollhouses,” something unexpected happened: this narrative became a watchword for the Eastern Christian community and a boundary marker against Rome and other Christians.

In fact, just before Constantinople’s fall, there was a concerted effort to reunite the Eastern and Roman Churches. Negotiations of a sort took place at the Council of Ferrara-Florence (1438-39) and were briefly successful in uniting the heads of East and West Churches. Of course, not all were satisfied with an agreement they saw as a surrender to Rome. Bishop Mark Eugenikos argued four great errors of the West that made reconciliation impossible: the primacy of the Pope (an ecclesiological problem), Western additions to the Nicene Creed (a doctrinal problem), unleavened bread (a ritual problem), and Purgatory, the Western doctrine of the purification of souls after death. Mark roundly rejected Purgatory as a Western innovation that took away God’s judgment. He was, however, quite content with the Tollhouses and their demonic masters. Mark used what many would see as speculaation in order to draw his line in the sand: the Tollhouses or Purgatory marked out a boundary point between two church communities.

Mark’s arguments would prove portentous for Orthodox Christians centuries after the collapse of the Byzantine Empire. Despite their popularity, the Eastern Churches have never rendered any opinion on the Tollhouses. So, in the 20th century, they once more became the topic of great debate.

“If the soul cannot pay, the demons get it and, presumably, take it to punishment in Hell.”

This time, though, both sides were composed of Orthodox theologians, priests, and bishops. Are the Tollhouses a dogma of the Church, a teaching of the Church that members are free to reject (a theologoumenon), or a heresy? For those engaged in them, this question is far from disinterested academic discussion. Opponents use fiery denunciations and shocking, even violent, language to describe the other. Each side musters its arms from centuries of Christian literature, seeking to establish its position on antiquity and neither hesitates to accuse the other of heresy, Gnosticism, and denial of the divinity of Christ—in short, of not being Orthodox Christians. The debate rages in internet forums, Facebook groups (there are now three, with total membership in the thousands), and church publications. Thus, the Tollhouses continue to serve as a boundary-marker: not only are they used to exhort people to lifestyles of piety, they are used as a shibboleth to discern whether a person is Orthodox and part of the ecclesial community, or a heretic and, therefore, outside the community.

Of course it all depends which side you speak to, what your answer means. And so whatever speculation one undertakes, one finds both a community to join and one to despise. So it is that an idiosyncratic and obviously fictive narrative of what happens after death has become, in the contemporary Orthodox Churches, a matter of life and death. Or perhaps I should say, of death and life.

Image Credit: “A grave pit” by Andreass. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post A matter of death and life appeared first on OUPblog.

A profile of Zelda Wynn Valdes: costume and fashion designer

In this interview with Professor Nancy Diehl, we look back in history to discuss and discover the life and accomplishments of Zelda Wynn Valdes, Master Teacher of Costume Studies at New York University, and designer of the original Playboy bunny costume.

* * * * *

Who was Zelda Wynn Valdes?

Zelda Wynn Valdes (1905-2001) was an African American fashion and costume designer whose career spanned 40 years. Working in and around New York City, the center of the American fashion industry, Valdes began her career as an assistant to her uncle in his White Plains, New York tailoring shop. In 1948, she opened her own shop on upper Broadway, and in the 1950s she moved her business to West 57th Street where, she had a boutique known as Chez Zelda. In the last chapter of her long career, she was the costumer for the Dance Theater of Harlem.

What set Valdes’s work apart from other designers of her time? What influence did she have on popular fashion of the 1940s and ‘50s?

The gauge of Valdes’s importance isn’t her influence on other designers; a better measure of her success would be the loyalty she enjoyed from her clients and the value they placed on her personal attention to their individual personalities and needs. The niche she occupied was quite particular: exquisitely finished special occasion dressing. She created wedding gowns, evening and cocktail dresses, and other luxurious ensembles. She dressed the entire bridal party at the 1948 wedding of Marie Ellington and Nat “King” Cole, an event that brought together the upper stratum of black society in New York, taking place at the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem which was officiated by Adam Clayton Powell, Jr.

Mae West, via New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Mae West, via New York Public Library Digital Collections. Who were some of her clientele?

Valdes had an established clientele especially among notable female entertainers and other prominent women within the black community. She counted among her entertainment-world clients Josephine Baker, Mae West, Ella Fitzgerald, Dorothy Dandridge, Eartha Kitt, and Marian Anderson. She also dressed the wives of famous black celebrities, including Nat “King” Cole and Sugar Ray Robinson. Unlike some other designers who exclusively created “costumes” versus “fashion”, Valdes moved between the two modes and her clients appreciated that as they ordered clothes for performance and also for their private wardrobes.

Every designer has that one design or outfit they are known for (like DVF and the wrap dress), is there an outfit that Zelda Wynn Valdes is most known for?

Valdes is perhaps best known as the designer of the original Playboy Bunny costume. While it’s not clear (and I’m currently researching this) that she was the sole creator of the costume, Valdes had an ongoing relationship with the Playboy Club in New York where she staged fashion shows so it makes sense that she was involved in the design. In addition, the snug satin Bunny outfit with its eye-catching décolletage is a reflection of her glamorous aesthetic.

New York Playboy Club Bunnies aboard USS Wainwright. By US Navy (US Navy All Hands magazine February 1972). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

New York Playboy Club Bunnies aboard USS Wainwright. By US Navy (US Navy All Hands magazine February 1972). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Why is Zelda Wynn Valdes’ story not only important to Black and Women’s History but Fashion History?

Zelda Wynn Valdes was one of the founders of the National Association of Fashion Accessory Designers, an industry group intended to promote black design professionals in a time when the fashion industry reflected the segregation of American society. It’s important that we not let the fact that Zelda Wynn Valdes was working within a segregated business environment restrict knowledge of her achievements. She dressed some of the most famous women in the world, for their private lives and for major performances, and her talent deserves an equally large stage.

Fashion is an aspect of culture — whether we think about it in financial or aesthetic terms — that affects most citizens in developed economies. That a fashion designer with such a long career and such renowned clients is virtually unknown today indicates that the prevailing narrative of American fashion is incomplete.

Heading image: Zelda Wynn Valdes. Courtesy of Dance Theater of Harlem. Used with permission.

The post A profile of Zelda Wynn Valdes: costume and fashion designer appeared first on OUPblog.

Cold War dance diplomacy

Why did the US State Department sponsor international dance tours during the Cold War? An official government narrative was sanctioned and framed by the US State Department and its partner organization, the United States Information Agency (USIA—and USIS abroad). However, the tours countered that narrative.

The State Department fed the notion that modern dance was quintessentially “American,” even as the tours themselves offered evidence of modern dance roots and influence from across the globe—notably German modern dance traditions and the importance of African diasporic arts movements to modern dance. While the USIA foreground the role of white male leaders, dancers such as Alvin Ailey explicitly countered this depiction. in his work Revelations, black Americans performed their struggle and their celebrations in dance works. The tours also accentuated the relationship among African anti-colonial movements and African American civil rights protests. Martha Graham had a pre-eminent role in touring for the State Department, who discussed how she was not “too sexy for export” but was rather just sexy enough.

But dance-in-diplomacy is not restricted to the Cold War era. The US State Department has begun funding tours again in the wake of the post 9/11. This return to cultural diplomacy more recently undertook a “collaborative turn,” foregrounding Americans and non-Americans working together, rather than only funding performances by American companies. The following slideshow depicts the contradictions in these narratives of dancers as diplomats.

American choreographers José Limón and Doris Humphrey

American choreographers José Limón and Doris Humphrey In this photo of

American choreographers José Limón and Doris Humphrey dine with German modern dance matriarch Mary Wigman in Berlin during the Limón company appearances at the 1957 Berlin Festival, one of many instances the Limón company appeared abroad under the auspices of the US State Department. The dinner, a formal one, was likely one of many occasions of dinners and receptions organized to introduce visiting American artists to locals, although this meeting did not bring together strangers, but instead luminaries of the transatlantic modern dance community.

Photograph courtesy of Charles Tomlinson, Pauline Lawrence Personal Collection, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

American dancers

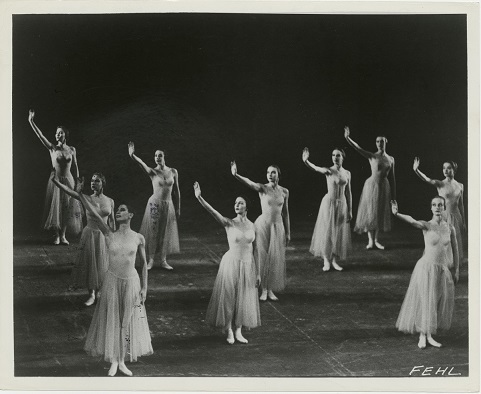

American dancers When the American national anthem played before a New York City Ballet performance of George Balanchine’s Serenade in Moscow in 1962 (during the Cuban Missile Crisis), the dancers rested their hands on their hearts, moved to the pose depicted above, and once again rested their hands on their hearts.

From left to right, first row front to back: Diana Adams, Niema Zweili, Carole Fields; Second row: Janet Greschler Villella; Third row: Victoria Simon, Una Kai, Francia Russell, Marlene Mesavage; Fourth row: Diane Conossuer, Joan Van Orden.

Photograph by Fred Fehl courtesy of Gabriel Pinski. Choreography by George Balanchine © The George Balanchine Trust

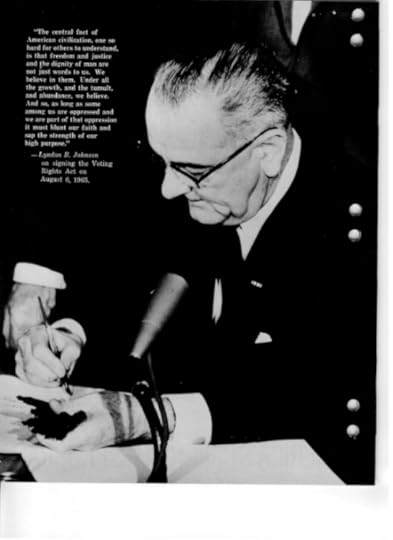

President Lyndon B. Johnson signing the 1964 Civil Rights Act

President Lyndon B. Johnson signing the 1964 Civil Rights Act From the inside cover of the USIA/USIS pamphlet, The Dignity of Man: President Lyndon B. Johnson signing the 1964 Civil Rights Act (with Martin Luther King, Jr. and other civil rights leaders who stood around Johnson at the moment of signing cropped from the photo).

Courtesy of the Lyndon B. Johnson Library and Museum.

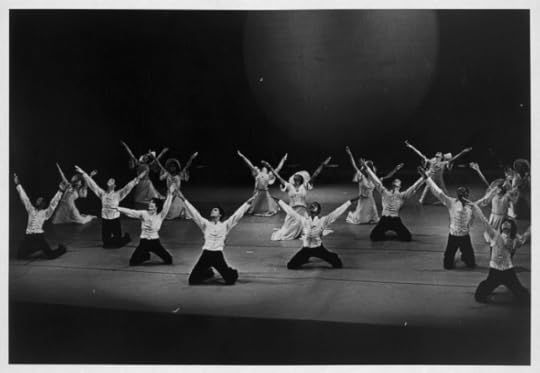

Alvin Ailey’s Revelations

Alvin Ailey’s Revelations The full Ailey company in the early 1970s in the final joyous movement of Alvin Ailey’s Revelations. Photo by Johan Elbers.

Courtesy of the Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc.

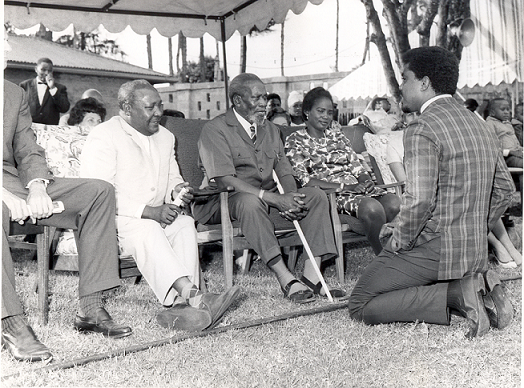

Alvin Ailey

Alvin Ailey Alvin Ailey kneels before Kenyan President Jomo Kenyatta, one of the best-known leaders of decolonization in Africa and the first president of Kenya. Mbiyu Koinage, Kenyan Minister of State, sits to Kenyatta’s right and Mama Ngina Kenyatta, Kenyatta’s wife, sits to his left.

Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Arkansas.

Martha Graham’s Phaedra

Martha Graham’s Phaedra This photograph is one of two photographs from Martha Graham’s Phaedra that appeared in LIFE Magazine in 1963 under the headline, “Is Martha Too Sexy for Export?”

From left to right: Bertram Ross as Hippolytus and Martha Graham as Phaedra.

Photograph © 2014 Jack Mitchell.

Bennalldra Williams

Bennalldra Williams In this photo, Bennalldra Williams, Urban Bush Women dancer, leaps in Jawole Willa Jo Zollar’s Walking with Pearl: Africa Diaries, one of the works performed on DanceMotion, USA’s first set of tours in 2010.

Photograph by Rose Eichenbaum.

Members of the Trey McIntyre Project and the Korea National Contemporary Dance Company

Members of the Trey McIntyre Project and the Korea National Contemporary Dance Company This photograph features members of the Trey McIntyre Project (TMP) and the Korea National Contemporary Dance Company (KNCDC) rehearsing McIntyre’s “The Unkindness of Ravens”.

From left to right: Chang An-Lee, Ryan Redmond, Lee So-Jin, Brett Perry, Kim Tae-Hee.

Photograph by Kyle Morck.

Headline Image: Ballet. Dancer. CC0 via Pixabay

The post Cold War dance diplomacy appeared first on OUPblog.

Beyond immigration detention: The European Court of Human Rights on migrant rights

The United Kingdom detains ‘far too many [migrants] unnecessarily and for far too long’. This makes the system ‘expensive, ineffective and unjust’. Such are the conclusions that a cross-party parliamentary inquiry reached earlier this month.

Over 30,000 migrants, including rape and torture victims, are detained in the UK in the course of a year, a third of them for over 28 days. Some detainees remain incarcerated for years, as Britain does not set a time limit to immigration detention (the only country in the European Union not to do so). No detainee is ever told how long his or her detention will last, for nobody knows. It can be days, months or years.

‘Shocked’ by some of the testimonies they heard, the members of the parliamentary inquiry have concluded that ‘little will be changed be tinkering with the pastoral care or improving the facilities’. They have said immigration detention must become a last resort and not be allowed to go on for over 28 days.

Activists have welcomed these recommendations, whose release has coincided with Channel 4’s broadcasting documentaries revealing the reality of life inside Yarl’s Wood immigration removal centre through the use of hidden cameras. The hope is that the UK is on the brink of a turning point in its immigration detention policy.

Improvements, however, will not go to the heart of the problem. Although the inquiry calls for ‘radical’ change, it stops short from recommending the abolition of immigration detention. As Bosworth observes, ‘there is still no principled discussion on the removal of liberty on the basis of immigration status, nor of its purpose and effect’. The crux is that immigration detention is wrong in principle.

If this is so clear, can we at least expect immigration detention to be unambiguously denounced from other quarters, such as the European Court of Human Rights?

“The hope is that the UK is on the brink of a turning point in its immigration detention policy.”

This may come as a surprise given the way the British government talks about Strasbourg, but the short answer is no.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers