Oxford University Press's Blog, page 670

May 4, 2015

How many of these famous political quotes have you heard before?

The week of the UK general election has finally arrived. After suffering weeks of incessant sound-bites, you will soon be free of political jargon for another few years. Phrases like “long-term economic plan” have been repeated so often that they have ceased to mean anything. However, at OUP, we remember a time when political speeches had a huge impact on the country. From Margaret Thatcher to Harold Wilson, from Benjamin Disraeli to Winston Churchill, British prime ministers and politicians have uttered phrases that have echoed throughout history. How many of these famous political quotes do you remember? See if you can match up the quote to the politician who said it in the quiz below.

Quiz image credit: Winston Churchill. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image credit: Houses of Parliament, by [Duncan]. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post How many of these famous political quotes have you heard before? appeared first on OUPblog.

May 3, 2015

Five years of Labour opposition

The 7 May 2015 marks the conclusion of a long and challenging five years for Ed Miliband as leader of the opposition. After one of the worst defeats in the party’s history in May 2010, he took over as the new leader of the Labour party with the mission to bring the party back into power after only one term in opposition. A difficult task at the best of times, Miliband’s political mandate was made even harder due to internal tensions between Blairites and Brownites, Blue Labour and New Labour, as well as many voters blaming the previous Labour government for the economic state of the country immediately after the 2010 election.

Five years later, with the election fast approaching, Ed Miliband’s mission is entering its final stages. Tasked with restoring faith in Labour across a wide range of issues, Miliband—alongside his fellow candidates—has been put under a microscope, his political history a matter of public record. The timeline below is a look at the key events of Ed Miliband’s time as leader of the opposition and his attempt to put Labour back into power.

Image Credit: “Houses of Parliament” by Andrew Vella. CC BY NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Five years of Labour opposition appeared first on OUPblog.

Fig leaves and fairy tales: political promises and the Truth-O-Meter

The Tampa Bay Times is a very fine newspaper. One of its most insightful features — indeed, a feature that was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 2009 — is its PolitiFact website. This is an independent on-line platform through which a legion of reporters and editors fact-check every statement, promise and half-hearted mumble ever made by a politician, political candidate, political party, or campaign group. In many ways this is public service journalism of the very highest standard, and what’s interesting about the website is that very often — deep intake of breath before I even dare to write these words — sometimes politicians tell the truth!

Such definitive judgements are clearly difficult and therefore a lot of political statements or promises result in a ‘mostly true’ or ‘mostly false’ conclusion that begins to tease apart the complexity of the issue being discussed. Or, put slightly differently, that there are no simple answers to complex questions that anyone can offer — be they politicians, candidates, parties, or advocacy groups. But taking to this to the top of the political tree in the United States what’s interesting about the ‘Obameter’ (which is following more than 500 promises made by President Obama in the 2008 and 2012 election campaigns) is that the might of American journalism seems to conclude the following:

Promise kept — 239 (45%)

Compromise — 130 (24%)

Promise broken — 116 (22%)

Stalled — 6 (1%)

In the works — 39 (7%)

Not yet rated — 2 (0%)

Truth lie sign by geralt. CC0 via Pixabay.

Truth lie sign by geralt. CC0 via Pixabay.Now I can already hear the mass ranks of ‘disaffected democrats’ stamping their feet and sharpening their pencils in light of any evidence that politics might actually — even in some small way — ‘work’. I’m also sure that the statistics may well contain subtle but important nuances that rotate around the fact that some promises may well be far more significant than others. But for the time being let’s just use the Truth-O-Meter as a concept that deserves further discussion, specifically in relation to how it relates to politicians, for at least three reasons.

First and foremost, the Truth-O-Meter works on the basis that politicians will always tell the truth. This is — at first glance — a fairly simple and straightforward assumption that would seem to exist (alongside motherhood, breast feeding, cuddly pets, and apple pie) in the pantheon of ‘good things’. Now I am not for one moment arguing against the centrality of political truth telling or the need for high levels of democratic accountability but I do wonder if the assumption is not — how can I put it — a little simplistic. Once in power even the most idealistic politicians will quickly realize that politics is a worldly art in terms of negotiating with rivals (within and beyond their party) and particularly when it comes to working with non-democratic regimes. Truth is and can be a difficult concept simply because politics is a messy business.

I would at this point invoke the arguments of Bernard Crick and heap praise on his In Defence of Politics (1965) but regular readers of this column know the intellectual canvas on which I write. Far better to move on to a second element of the Truth-O-Meter that democratically dubious — that ‘Promise kept’ seem to be rated above above ‘Compromise’. The immediate logic of such a position seems obvious . . . until you think about the incredible complexity and fluidity of modern politics. To be a politician is to exist in a world of ever-increasing and rarely compatible demands in a context of shrinking resources. This is the simple problem. The great beauty of democratic politics (here comes the ‘Crick moment’) is that it provides a way of squeezing collecting decisions out of a great multitude of conflicting demands. The process might not be pretty or easy for outsiders to understand but the central emphasis of the whole democratic structure is towards achieving consensus and compromise. Put slightly differently, the risk of keeping promises in an over-simplistic manner in order to please the Truth-O-Meter is that I may actually lead to decisions being made that are simply irrational and ‘bad’ or simply undemocratic and designed to appease a vocal minority.

My aim is not to defend those devilish politicians but simply to highlight that the Truth-O-Meter may — in some strange ways — end up valuing and measuring the wrong things. The stateswoman or statesman politician will be the one that stands up and says ‘I was wrong’ and reneges upon a promise or commitment made in haste or under undue pressure.

This thought brings me to my third and final point and shifts our focus across the Atlantic from the United States to the United Kingdom. With just days to go before the General Election all of the main political parties are engaging in what can only be termed a ‘promise orgy’. Money is being found for just about anything; you want a budget protected from future cuts – ‘you got it!’; you want to pay less tax – ‘you got it!’; you want to pay no tax – – ‘you got it!; you want to fill the rivers and streams of England with Cola – – ‘you got it! (This last promise was just my own personal fairy tale but you know what I mean.) To some extent the whole game of democratic politics forces politicians to over-promise but my concern in the UK is that the promises have become ridiculous and the public simply do not believe it. ‘Where exactly will the money come from?’ is the core question that has no real answer. This has been an anti-political General Election.

So please can I say to the Tampa Bay Times: keep up the good work, but it’s probably best if you don’t bring the Truth-O-Meter to the UK in the near future.

Heading image: Road sign by geralt. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Fig leaves and fairy tales: political promises and the Truth-O-Meter appeared first on OUPblog.

Destination India

What would it be like driving overland from London — East of Suez and over the Khyber Pass — to India ? Day by day and mile by mile, we found out, recording our impressions and experiences of people, landscape, and encounters as we drove a 107″ wheel base Land Rover from London to Jaipur. The year was 1956; the months July and August. Our 5,000 mile journey took us across the ecological and cultural limes distinguishing Europe from Asia and into the Indian subcontinent. As freshly minted PhDs, 26- and 28-years-old, we were open to adventure and to knowledge of the other. Funded by a Ford Foundation Foreign Area Training fellowship, we found ourselves positioned at the cusp of the area studies era generated by the end of colonial rule.

Modernization theory was regnant then and we argued that it was wrong to suppose that tradition would be swept into the dust bin of history; that “they” would become like “us”. We showed how and why tradition was often adaptive, change dialectical not dichotomous, and “we” could learn from “them.” We also learned an important methodological lesson being there. Many western scholars of “new nations” sought to find universal truths, truths that were said to be true everywhere and always. We found ourselves learning from the other and grounding our concepts and categories in local knowledge and practice. We characterized our approach as situated knowledge, knowledge that arises out of particular times, places and circumstances, and that results in contextual rather than universal truths. Travelling through countries of western Asia — Turkey, Iran, and Afghanistan — shaped our perspective. We learned that if India was less developed than the countries of Western Europe, it was more developed than the countries lying between western Europe and South Asia.

Land Rover at Kuindorf

Land Rover at Kuindorf, Susanne’s ancestral home in Germany, on the way to India in 1956. She is at the rear and cousin Britta at the front washing the car. Image courtesy of Lloyd Rudolph and Susanne Rudolph.

Rashtrapati Bhavan

Lloyd and Susanne with President R. Venkataraman, Mrs Venkataraman, Gopal Krishan Gandhi at Rashtrapati Bhavan. Image courtesy of Lloyd Rudolph and Susanne Rudolph.

Land Rover in Rajasthan, 1956

Land Rover in Rajasthan, 1956. Susanne with unknown friend. Image courtesy of Lloyd Rudolph and Susanne Rudolph.

Land Rover in Rajasthan, 1956

Land Rover in Rajasthan, 1956. Susanne seated at picnic lunch table. Image courtesy of Lloyd Rudolph and Susanne Rudolph.

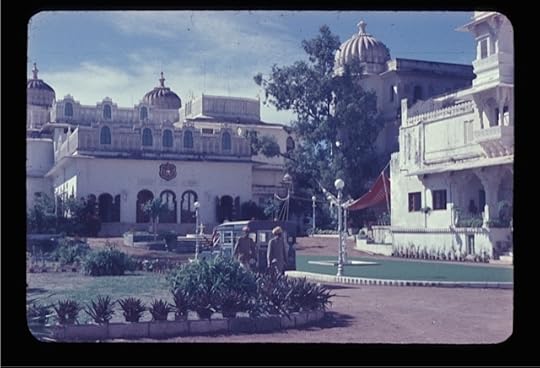

Jai Mahal Palace Hotel, Jaipur 1956

Land Rover at Jai Mahal Palace Hotel, Jaipur 1956. Image courtesy of Lloyd Rudolph and Susanne Rudolph.

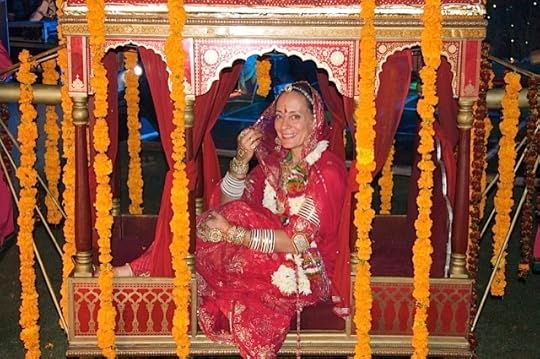

Daughter Amelia's Indian wedding

Daughter Amelia's Indian wedding, Jaipur

Daughter Amelia’s Indian wedding, Jaipur. Image courtesy of Lloyd Rudolph, Susanne Rudolph.

At Harvard where we did our PhDs in Political Science, we studied comparative politics and nationalism with Samuel Beer, Rupert Emerson, and Carl Friedrich. We learned to analyze institutions, politics, and, even then, policy as they were defined by European and American historical experience. Our graduate education at Harvard in the mid-1950s didn’t equip us (as our students at the University of Chicago were equipped from the mid-1960s onward) with knowledge of South Asian languages, history, and culture. (The Eisenhower administration introduced the National Defense Education Act (NDEA) South Asia area and language programs in the post-Sputnik area.) We learned Hindi on our own and at the Landour Language School and about India’s history, culture, and society while doing research in India. Our openness to area and language knowledge was partly a consequence of working while junior faculty at Harvard with David Riesman in his course on American Character and Social Structure, and with Erik Erikson in his course and seminar on life history and identity formation. These experiences prepared us intellectually and emotionally better than did our graduate education in political science to respond to living in and learning from India. They liberated us from the disciplinary straight-jacket of political science and opened the way for us to be humanistic social scientists more concerned with meaning than with causation.

From 1956-57 onward, roughly every fourth year until 1999-2000, we took leave to do research in India. In all, we spent eleven years on the sub-continent doing research. Starting with our second research year, 1962-63, the first of our three children accompanied us. Over the subsequent nine research years our children travelled to India with us. They attended Indian schools: St. Xaviers and Maharani Gayatri Devi Girls Public School in Jaipur, the Woodstock School in Mussoorie/Landour. Living in India they experienced Indian family life and formed lasting friendships. In the process they acquired a passable Hindi. Beginning in 2001, as an aspect of our retirement arrangements, we have been able to spend the winter months, January through March, living and working in Jaipur.

India captured our imagination as a place to encounter, study, and learn from. We drove to overland from London in a Land Rover in order to be there. And we’ve spent the subsequent 50 years researching, theorizing, teaching, and writing about this country.

Featured image: In front of the Jaipur Palace, India, 1956. Photo by Marc Riboud. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Destination India appeared first on OUPblog.

Reference and the election of the new Italian President

After three inconclusive rounds in the preceding days, in which nobody secured the two-thirds majority needed to win, on the morning of 31 January 2015 a fourth round of voting was held in the Italian Parliament to elect the country’s President.

This time, a simple majority of the 1,009 eligible voters (the members of both Chambers of the Parliament plus some delegates from the Regions) was enough to decide the election. To vote, the voters had to write a name on a ballot paper and insert it into one of the several ballot boxes. When the ballot boxes were opened, it turned out that 665 of the 995 ballot papers had the word “Mattarella” written on them, sometimes together with other expressions (e.g., “on. Mattarella”, “Mattarella S.”, “Mattarella Sergio”, “Sergio Mattarella”, “prof. Sergio Mattarella”, “S. Mattarella”, “on. S. Mattarella”, “on. prof. Mattarella”).

As a result, the Constitutional Court judge Sergio Mattarella, a former member of the Parliament (from 1983 to 2008) and Minister of Education (from 1989 to 1990) and of Defence (from 1999 to 2001), was proclaimed the 12th President of the Italian Republic.

As a President he’ll probably follow in his predecessor, Giorgio Napolitano’s, footsteps and act as an impartial arbiter and defender of the Constitution, not a bad thing in the present Italian political situation. Politics, however, is not the real subject of this post.

Instead, I’d like to ask you to pause on the phrase above, “as a result”. On the face of it, it sounds quite natural. It was used to state a connection between two indisputable facts, that concerning the ballot papers and what was written on them and that concerning the proclamation of Mattarella as President: given the constitutional background and various other things, the former fact, we meant to say, brought about the latter. But, even granting the background, how is it that the 665 ballot papers having the word “Mattarella” written on them determined the election of that particular person, Sergio Mattarella?

The natural answer is, of course: this is so because those 665 ballot papers counted as votes for him, and they counted as votes for him because of the scribbles the voters made on them. Here, however, is where the problems begin. What do those scribbles have to do with Sergio Mattarella?

Sergio Mattarella, by the Polish Senate. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Sergio Mattarella, by the Polish Senate. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Well, they are his name, one could say: the ballot papers had his name written on them. But the fact is that there are a lot of other persons named “Mattarella” in Italy. And a quick search on the web suffices to verify that some of them have “Sergio” as their first name. Notice, moreover, that the eligible voters didn’t have to choose between listed candidates. Indeed, the Constitution of the Italian Republic states that “any citizen who has attained fifty years of age and enjoys civil and political rights can be elected President of the Republic” (art. 84).

As a matter of fact, a number of surprising people — e.g., the folksinger Francesco Guccini, the actress Sabrina Ferilli, the comedians Ezio Greggio and Enzo Iacchetti, and even the thirty-eight-year-old and hence non-eligible soccer player Francesco Totti — received votes during the four rounds of these elections. (Just for the record, in the second round of the preceding elections (April 2013) Sophia Loren, Giovanni Trapattoni and the porn star Rocco Siffredi received one vote each, which may tell you something about Italy.) Why, then, shouldn’t we consider any of these other persons named “(Sergio) Mattarella” satisfying the conditions stated by the Constitution to be the new President?

“Wait a moment,” one might sensibly object, “isn’t it clear that the 665 voters who wrote ‘Mattarella’ on their ballot paper intended to vote precisely for the person who was proclaimed President?” Maybe so, although intentions are sometimes murky and not easily ascertainable. But, even granting that in this case the intentions to vote were indeed clear, it should be noted that there is sometimes a gap between intending to do something and doing that something, and voting doesn’t seem to constitute an exception: one can intend to vote for someone but actually vote for someone else.

If someone intending to vote for Sergio Mattarella, for example, had by mistake written “Mastella” on his or her ballot paper, we would say that he or she did vote for another well-known Italian politician, the much discussed former Minister of Justice Clemente Mastella, in spite of his or her intentions. Hence, the problems mentioned above cannot be solved simply by appealing to intentions: to explain why exactly the Constitutional Court judge Sergio Mattarella is the new legitimate President we need to resort to something else.

In a nutshell, what we are looking at here is the problem of reference, which became central in the philosophy of the last century. What we should say, in fact, is that the 665 ballot papers having the name “Mattarella” written on them counted as votes for Sergio Mattarella because, on that occasion, the words written on them referred to him. But, again, what makes it the case that, on that occasion, the words referred to him?

Nowadays, probably the majority of philosophers, influenced by the work in the late Sixties and early Seventies of Keith Donnellan, who has recently sadly passed away, and Saul Kripke, certainly one of the most important living philosophers, believe that the answer lies in some sort of historical (or, as many also like to say, causal) connection between those particular uses of the words and Sergio Mattarella himself. However, what this connection amounts to is still a matter of some controversy.

This, of course, doesn’t mean that Sergio Mattarella is not the legitimate President of the Italian Republic. My perhaps surprising contention is merely that, for a complete and philosophically satisfying explanation of why he is so, we may have to wait for developments in the study of reference.

Featured image credit: Palazzo del Quirinale, by Bernardo Marchetti. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Reference and the election of the new Italian President appeared first on OUPblog.

May 2, 2015

What is the history of the Green Berets?

With Memorial Day fast approaching, it is worth examining the history of our armed services, including the modernization of the military during the Cold War. This excerpt from The U.S. Special Forces: What Everyone Needs to Know® by John Prados explains how the Special Forces, also known as the Green Berets, evolved during President John F. Kennedy’s term.

How did President Kennedy change Special Forces?

President Kennedy showed himself to be very concerned about the ability of the United States to meet challenges at the brush-fire level, short of conventional war. Counterinsurgency became a watchword in the Kennedy administration. Indeed, at the topmost level of government Kennedy created a subpanel of his National Security Council, the Special Group (Counterinsurgency), specifically dedicated to monitoring US efforts in this field and providing impetus to new policy and technological initiatives. Kennedy aides encouraged the creation of a “counterinsurgency seminar” that would impart knowledge of the problems of brush-fire contingencies to officials across government, and the White House paid attention to its attendance and performance statistics. Kennedy aides, among them Walt W. Rostow, exhibited specific concern regarding Special Forces. Rostow spoke at the Special Warfare Center at Fort Bragg and arranged for President Kennedy to visit there.

John F. Kennedy went to Fort Bragg on October 12, 1961. The day is renowned in Forces’ lore as the moment when Special Forces was awarded the Green Beret. Armies throughout the world distinguished themselves, and even their particular units, with berets of varied color and design, something the US military had resisted. From the early days of Special Forces the A-Teams had adopted “unauthorized” forms of headgear including (but not limited to) berets, but these had always been unauthorized. Theoretically a trooper could be disciplined for being caught wearing one. The exotic headgear had mostly been used away from base and the eyes of senior officers. By the time Kennedy came to Fort Bragg most Special Forces had the berets, still officially illegal. The top Special Forces commander, Brigadier General William P. Yarborough, took a chance and received his president and commander in chief wearing a green beret. Jack Kennedy, a twinkle in his eye, saw the hat and asked, “Those are nice. How do you like the Green Beret?” Yarborough replied, “They’re fine, Sir. We’ve wanted them a long time.” Upon returning from his trip President Kennedy sent a thank you message that said, “I am sure that the Green Beret will be a mark of distinction in the trying times ahead.”

Ever since then Army Special Forces have been known as the Green Berets. Not only did Kennedy officially approve them, he used nearly identical language in his memorandum. Air Force Special Forces soon followed suit and adopted berets for their unconventional warfare units. Later the Army Rangers would be distinguished by red berets. After 9/11 berets were adopted for all army forces, with certain combat arms identified by color like the Rangers and the Special Forces. Here the Green Berets made a naming and fashion statement for the entire US military.

But the armed services did more than change hats. President Kennedy’s emphasis on limited wars and counterinsurgency led to a host of changes. Kennedy reprised his compliment to the Green Berets in an April 1962 letter “To the United States Army.” The army got the message. Officials hastened to assemble and print a slick pamphlet, Special Warfare, U.S. Army: An Army Specialty, released shortly thereafter. Among other things the book reprinted the president’s letter and Walt Rostow’s speech at Fort Bragg, and had Secretary of the Army Elvis J. Stahr Jr. saying, “I expect commanders to draw upon this material in their training … for proficiency in Special Warfare is an indispensable requirement for the effective soldier and combat leader in today’s Army.” Not to be outdone, the US Marines released their own selection of readings on counterinsurgency and guerrilla warfare.

The moment came when Special Forces, like US intelligence, could really be called a “community.” The navy and air force both got serious about unconventional warfare. The seamen supplemented their underwater demolition teams with Sea, Air, Land, or SEAL teams, with one created on each coast in January 1962. In Florida, at Eglin Air Force Base, that service created a mixed attack-transport-military advisory capability in its 4400th Combat Crew Training Squadron, familiarly known as “Jungle Jim.” It reprised the air commandos of Burma fame, forming the First Air Commando Wing, which traced its lineage directly to the World War II formation with this number. Both the wing and a Special Air Warfare Center were created at nearby Hurlbut Field in April 1962. The army and air force both established special warfare staff at the Pentagon level.

By far the largest personnel growth took place in the Green Berets. All three existing Special Forces Groups were built up to their full strengths of about 1,500 soldiers. Four new groups appeared, a new provisional group for the Far East (which would become Fifth Special Forces in Vietnam), the Eighth Group in Panama and oriented to Latin America, and at Fort Bragg the Third and Sixth Groups, focused on Africa and the Middle East respectively. New groups were also added to the Army Reserve and National Guard. To staff all these forces far more people were required. The Special Warfare School began to graduate many more volunteers (“wash out” rates fell from nearly 90 percent to about 70 percent), producing many more Green Berets—over three thousand annually compared to about four hundred previously. For the first time, to meet its 1965 manpower goals Special Forces accepted army recruits on their first term of service. That meant the army stopped insisting that the Green Berets be composed entirely of highly experienced soldiers. Within a few years that standard had expanded further to include draftees. A Pentagon report to President Lyndon Johnson in early 1965 tabulated army special warfare forces at 11,343 as of November 30, 1964.

The original Green Beret concept of fomenting resistance to an occupying enemy also widened in the counterinsurgency era. Now Green Berets assisted host country armed forces to combat guerrilla threats by means calculated to win the hearts and minds of indigenous populations. The Berets already helped train foreign troop units and mobilize local fighters. Now they aimed to help increase the efficiency of governments. The idea of increasing public acceptance for a government through civil affairs became a new technique. This meant improving village and regional infrastructures and local conditions by means of medical services and construction work. Psychological warfare efforts aimed to cement the public’s support. Special Forces added civil affairs groups, psychological warfare battalions, and engineer detachments. Augmenting the intelligence resources necessary to serve this variety of missions brought the addition of intelligence detachments and radio spies, elements of the Army Security Agency, the army’s radio intelligence service. The old Special Forces “group” suddenly morphed into a “special action force.” Four groups—those focused on Asia, Latin America, Africa, and the Middle East—acquired this status.

Innovation did not confine itself to organizations. Special Forces interest resulted in the development of new techniques and technology as well. Not satisfied with standard US Army issue, Special Forces sought the best equipment for its operators. If that meant Swedish submachine guns, German-made hiking boots, or extra-large backpacks, so be it. Special Forces had the funds and outside-of-channels contracting authority to procure what they needed. Some of this stuff was quite exotic, such as the rocket belt that carried a Green Beret through the air to land in front of President Kennedy for the climax of his Fort Bragg visit. More practical was the technique evolved for an aircraft snatching a man from the ground without landing, an innovation of interest to both the Forces and the CIA. The SEALs developed underwater sleds capable of transporting a half-dozen swimmers. All were popularized in James Bond movies of the 1960s.

Probably the most remarkable Special Forces technology initiative was its early adoption of the Armalite AR-15 semiautomatic rifle, a lightweight but powerful gun. As the M-16, this became the standard weapon for the US armed forces during the later part of the Vietnam War. After teething troubles in Southeast Asia, it not only survived to become the service weapon for many armed forces and paramilitary groups across the globe, but remains today (in its M-4 variant) the regular armament of the US military, including Special Operations Forces.

Image Credit: Photo by The U.S. Army. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post What is the history of the Green Berets? appeared first on OUPblog.

Authors for Indies: Oxford University Press celebrates Canada’s independent bookstores

This year, Authors for Indies Day takes place on Saturday, 2 May. To celebrate, the staff at Oxford University Press Canada have decided to highlight some of their favourite independent bookstores. Here are some of Canada’s favourite literary hangouts, and where you can find them.

* * *

Novel Idea

156 Princess Street, Kingston, Ontario

This is a cozy little locally owned bookstore, conveniently located in Kingston’s downtown core. They carry a good selection of fiction, non-fiction, children’s books, books by local authors, and magazines. They will cheerfully order titles not in stock. The Staff are friendly and knowledgeable – helping out when you need them, or otherwise letting you linger over possibilities!

– Brooke Healey (Sales and Marketing Assistant, ELT)

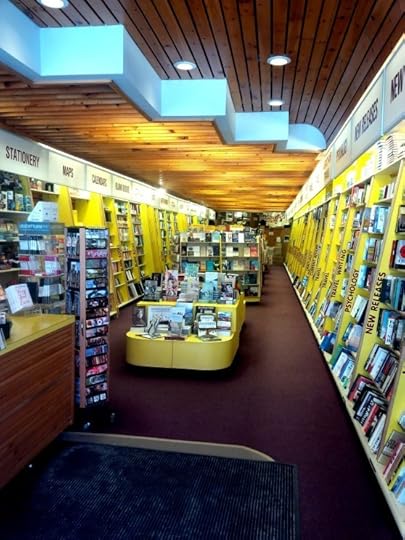

Bookmark

5686 Spring Garden Rd, Halifax, Nova Scotia

Bookmark Bookstore, Halifax, Nova Scotia. By Maïca Murphy for Oxford University Press.

Bookmark Bookstore, Halifax, Nova Scotia. By Maïca Murphy for Oxford University Press. Nestled near the end of one of the most frequented shopping streets in Halifax, Bookmark is a cozy bookstore that will capture the spirit of any bibliophile as well as casual literary explorers. You can go in looking for a travel guide, the newest Gibson, or nothing at all in particular and walk out with your newest treasure. The store will often carry new literary gems (both local and not) that big box stores won’t bother stocking. It is filled with a carefully considered, yet somewhat eclectic mix of books organized by genre demarcated with overly bright yellow signage, which is lovely. The store has a remarkably large selection given the small footprint. The staff is knowledgeable without being intimidating and strike the perfect balance between letting their customers get lost in exploration and making suggestions (if asked). I find myself going back over and over.

– Maïca Murphy (Sales and Editorial Representative, Higher Education)

* * *

Curiosity House Books & Gallery

178 Mill Street, Creemore, Ontario

This little place looks exactly like a bookstore should. Wooden shelves are stocked with books of every variety, and the store is full of an ever-changing selection of art, not to mention lots of people browsing the shelves and chatting with the kind and knowledgeable staff. The store hosts and takes part ton of readings and events all around the Barrie/Creemore area, including a recent reading and signing by Canadian literary legend Margaret Atwood. The store is committed to turning kids and teens into book lovers, and kids are encouraged engage in lively debates with employees about their current faves. There are even a few young readers that spend an afternoon or two volunteering in the store, which is a wonderful thing to see. Curiosity House is a true member of the community, and a great place to spend an afternoon. Whenever I’m in town, I always make sure to stop in, and I inevitably leave with a few new treats for my bookshelf.

– Kate Abrams (Sales and Marketing Assistant, Retail and Wholesale)

* * *

The Bookshelf

41 Quebec St, Guelph, Ontario

The Bookshelf in Guelph, Ontario was my favourite haunt while completing my undergrad at the local university. I loved reading staff recommendations on the shelf tags and would quite often be persuaded to buy a book by a well-placed review by a community member. While my grades (and wallet) may have suffered slightly by the amount of time perusing this quaint shop and then evaluating my purchases at the attached café, the contents of my bookshelf are that much richer.

– Krista Westmaas (Sales Representative, Retail and Wholesale)

* * *

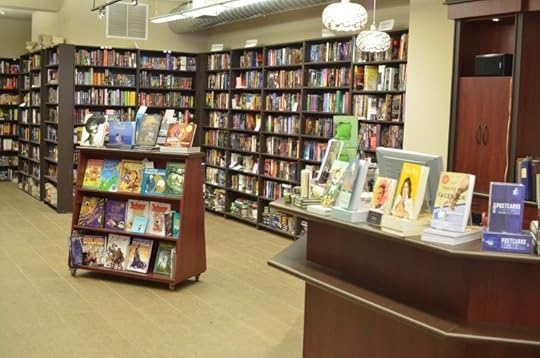

Bakka-Phoenix Books

84 Harbord St, Toronto, Ontario

My favourite independent bookstore is Bakka-Phoenix Science Fiction & Fantasy Bookstore in Toronto.

Bakka Phoenix Books, Toronto, Ontario. By Stephen Kotowych for Oxford University Press.

Bakka Phoenix Books, Toronto, Ontario. By Stephen Kotowych for Oxford University Press. Bakka-Phoenix is Canada’s oldest science fiction and fantasy specialty bookstore, and after more than 40 years in business I suspect they’re one of the oldest in the world.

Yes, you can find great books here, and discover fantastic new authors and obscure gems from the recommendations of their incredibly well-read and friendly staff. But more than that, Bakka-Phoenix is the hub of a vibrant literary and fan community in Toronto. It’s the kind of bookstore where you become friends with the people who work there. You come in to buy books, and end up having hour-long conversations about, well, anything and everything going on in each other’s lives. Bakka-Phoenix hosts author appearances, readings, and panels; they participate in offsite events at libraries and conferences, too. Many noted Canadian science fiction and fantasy authors—including Cory Doctorow, Nalo Hopkinson, and Robert J. Sawyer, amongst others—have worked there at one time or another.

It’s this commitment to community, in addition to great selection, that I suspect is the secret of their success despite the vicissitudes of bookselling over the last several decades. Long may they continue! I, for one, couldn’t imagine my city without them.

– Stephen Kotowych (Acquisitions Editor, Higher Education)

* * *

Munro’s Books

1108 Government St, Victoria, British Columbia

I love a bookstore with history. Munro’s books dates back to the early sixties, and was started by Jim and Alice Munro (yes, the author!). The architecture is beautiful – the location is a former bank, built in 1909 in the heart of downtown Victoria, and its loved by locals and tourists alike. What I like most, though, is their selection; in addition to the usual popular fiction selections, Munro’s features a ton of local and region-specific sections; from baby board books on First Nations History and Legends, to BC book prize winners, to Canadian-specific cookbooks or biographies. It’s rare to get a rainy day on the island, but when one comes along, Munro’s books is the perfect place to go poking around – you’re always sure to find something new and unexpected here.

– Bethany Joliffe (Sales and Editorial Representative, Higher Education)

* * *

Do you have a favourite independent bookstore? Let us know in the comments below.

Heading image: Munro’s Bookstore. By Bethany Joliffe for Oxford University Press.

The post Authors for Indies: Oxford University Press celebrates Canada’s independent bookstores appeared first on OUPblog.

What has been your most memorable election experience?

We asked three OUP authors to describe their most memorable election experience in the build up to next week’s general election in the UK. Their stories range from Press Association mishaps to covering elections in New Zealand to the importance of voting. What has been your most memorable election experience? Let us know in the comments below.

**********

Accuracy takes precedence over speed when reporting election results, but that doesn’t mean things can’t go wrong – as I learned one night covering the local count in Harrogate for the Press Association. Somehow we caused a small political earthquake in the normally calm North Yorkshire town.

It was back in the 1990s when the Liberal Democrats ran the council, which is one of those on which only a third of seats are up for grabs at any one time.

My one simple task was to phone London with the tally of seats won by each party as soon as the final result was declared. PA subs would calculate the effect on the overall make-up of the council and within seconds the information would arrive in newsrooms: Lib Dem, no change.

So it was with some surprise that, having delivered this unremarkable fact in the early hours of the morning, I turned on the car radio to hear Lib Dem leader Paddy Ashdown on the BBC coming to terms with the shock news that his party had just lost its flagship authority of, er, Harrogate.

By the time I got back on the line to London a hasty post-mortem examination had already discovered that somebody on the PA election desk had put all the Lib Dem victories in Harrogate under Labour. That created an entirely unprecedented (and unlikely) surge for the latter, which had actually won zero seats.

The most striking thing about the incident was not the fact that mistakes happen – they do. Rather, it was the smooth job that Ashdown made of explaining how this setback had to be seen in the context of what was overall a good night for the party. That was certainly one occasion on which he was not caught with his pants down – we were.

— Tony Harcup, author of The Oxford Dictionary of Journalism

**********

Elections produce a most singular feeling for me. The very act of putting a cross in a box, next to a name, is one that captures a very complex set of emotions. On the one hand, I have come to appreciate the genuine value of having a vote at all, a right that was hard fought for and whose worth we too easily dismiss: the power to make a free choice about who represents us and who governs us is one that I often find myself discussing with students, colleagues, family and friends (which may be why I don’t get invited out to dinner so much).

On the other hand, I also know that my vote, my cross, will probably not result in my preferred candidate getting elected: my track record of living in constituencies where another party has a sake majority is impressively consistent. Indeed, it was only when I moved to Belgium in the late 1990s that I got to vote in (European) election where I could be secure in the knowledge my representative would have a chance, thanks to a proportional representation system. But I have still yet to help return someone to my national parliament, something that looks set to continue.

That mixture of feelings as I stand in the voting booth always makes me ask the question: why do I put up with it? Why do I accept the result?

Part of me doesn’t actually accept it, and tries to push for electoral reform whenever I get the chance (like now). But most of me does abide and for a simple reason. Democracies aren’t perfect – they can’t be – but they are still a lot better than the alternatives out there. And that brings me full circle: as I step out of the polling station, I get to reflect that millions of people don’t have the luxury of voting like I do, and in my own small way, my vote can reaffirm its worth, whatever the outcome.

— Simon Usherwood, co-author of The European Union: A Very Short Introduction

**********

It was 2002, and it was winter in July in New Zealand. I’d hoped to relish the chance that New Zealand’s MMP system gave me to make two choices – one for the MP representing my constituency and a second for whichever party I most wanted to govern the country as a whole. But there wasn’t much time. I’d messed up. A couple of months before, I’d agreed to write a post-election column analysing the results for a national newspaper. Then, a couple of weeks before polling day, National Radio asked me if I’d be the academic expert in their all-night, live election coverage.

I’d accepted, blithely assuming that a fortnight’s notice meant that I could let the paper know I’d have to cry off the column. I was wrong. I wasn’t going to pass up the opportunity to do the radio show, so I had only one option. The election could go four ways, so I would have to write four columns during the day, then, as the results came in, decide which one to go with. I could then tweak it during any breaks I was allowed to take and dispatch it before getting on with the rest of the show. As the results came in I realised, that one of my guesses seemed about right.

I went with that version, touched it up as others were talking, and then, taking the least comfortable comfort break ever, popped out for a few minutes to polish and press send. The result of the election? A second consecutive win for Labour. They followed up with a third in 2005 before losing power to the conservatives, who then went on to win three on the trot themselves. Ed Miliband, I assume, will be hoping there’s no such thing as a precedent for British politics from the land of the long white cloud.

— Tim Bale, author of Five Year Mission: The Labour Party under Ed Miliband

Featured image credit: Polling Station, by secretlondon123. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post What has been your most memorable election experience? appeared first on OUPblog.

May 1, 2015

Later interviews as counter narratives: Treblinka and the ardent lover

A few months ago, we asked you to tell us about the work you’re doing. Many of you responded, so for the last few months, we’ve been publishing reflections, stories, and difficulties faced by fellow oral historians. This week, we bring you another post in this series, in which Henry Greenspan offers a compelling assessment of the life stories approach to oral history. We encourage you to engage with these posts by leaving comments on here or on social media, or by reaching out directly to the authors. If you’d like to submit your own work, check out the guidelines. Enjoy! – Andrew Shaffer

Oral historians differ on the utility of retrieving participants’ full life stories, but we agree that “full” is a relative term. There is always much unsaid in any life’s retelling, and for a wide range reasons. Drawing on forty years of interviewing Holocaust survivors, I emphasize here that what is unsaid in early interviews often emerges in later ones. Indeed, later interviews may even become counter narratives to earlier recounting—a way for participants to tell us not to “peg” them too easily or too soon.

For example, simply by inviting someone to speak “as a Holocaust survivor” foregrounds the Holocaust as cause and much of the rest a survivor may have to retell as some version of effect. Such attributions of causality may or may not be true. What is beyond dispute is that attributions in any life are complex, that survivors themselves wonder about them all the time, and that their answers change over sustained conversation. When one goes beyond single survivor “testimonies” to multiple interviews with survivors, which has been my own approach, this happens commonly.

Victor, a survivor of Treblinka, initially explained two critical choices of his—working in a factory and marrying a non-Jewish woman after the war—as direct results of the Holocaust and the anti-Semitism that was its foundation. Regarding the former, he reflected:

I wasn’t in business. I went to work in a factory. Do you know for what reason? Because I was sick and tired of Polish people saying that Jews are always in business. “The Jews are always in business.”…This pierced my heart. I was one Jew in a factory of a thousand people.

While it evokes more evident conflict, his marrying a non-Jewish woman—“going out of the line,” as he calls it—is similarly explained:

At that time, there was the feeling to get away from all that happened. And, in the future, to keep it away from those who come after me. Because there was the feeling that no one can stop another wave of that.

History can repeat itself. I don’t want that my children should suffer the way I did. I don’t want to have on my conscience that I lead them to another Holocaust.

Victor has specific memories of some who did curse their ancestry in the midst of the destruction. They are part of what informs these reflections.

It came as a surprise, then, that several months into our conversations Victor offered additional—and quite different—explanations for his choices. Regarding factory work, Victor recalled that this was his preference and that choosing it over business was not reducible to Polish anti-Semitism. Indeed, many years before the war, Victor’s preference for working in a factory had been a source of conflict with his father, who was himself a successful businessman.

My father didn’t want me to work in a factory. He wanted me to be a businessman. To do the same thing he does.

(HG: He said that’s what he wanted?) Yeah. He criticized me. That nobody in the family should work in a factory. And I work in a factory….I liked work in the factory. I liked it. My father didn’t like it. But I did like it.

Here, a fully normal father-son conflict was recalled, revealing a choice not attributed to hatred or the Holocaust.

While Victor’s readiness to marry a Catholic woman may well have been conditioned by the destruction, there were also far more affirmative reasons why he married the particular woman he did. Choosing for love and against business were, in fact, related, as he explained regarding his briefly working in in the jewelry business with a surviving brother when he first came to the United States in 1950.

I started with my brother in the business. But then I went back to Italy after three months because I left my heart over there.

(HG: You “left your heart”?) I fall in love in Rome. So I make three trips there and back. I was already here three months, and I go back to Italy. Where I stayed six months with my wife.

I even read, every month there is a Jewish newspaper. And in it they write about some woman, her husband died, and they are looking for someone to marry her and take him into the business. This was Jewish people. I read it. I paid no attention. I was in love with her. You understand?

The word “love” was startling in our conversations because of its complete absence up until that point. As Victor surrendered to the thrall of these memories, his description of his relationship with his son—embattled because of his son’s own romantic relationship (reflecting the cost of phone calls, not faith)—took on an entirely different tone.

I was the same. When I was in love, I was the same. Ardent. An ardent lover. I see me in him. I see, when I look back, I see where I was. Three times, three times I went back over to Italy!…I was also in love. I was also crazy.

What began as an interview with a Holocaust survivor became a kind of “guy talk”—much of which I won’t repeat here, both out of respect for Victor’s privacy and that of all “ardent lovers.”

We are not used to imagining a Treblinka survivor and a crazy, ardent lover as the same person. We almost always assume that having endured the Holocaust or another mass “trauma” must be the axis around which the rest of a life turns, and that presumption tends to be confirmed in single testimonies precisely because they are based on only single interviews. But we will have to move beyond such assumptions if we are to avoid mistaking the “life stories” generated in our projects—and especially those generated early in our projects—for the far more complex ways in which lives are actually lived and, given the opportunity, recounted, whether the lives of Holocaust survivors or of anyone else.

Image Credit: “Embrace Sculpture” by Eric Kilby. CC BY SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Later interviews as counter narratives: Treblinka and the ardent lover appeared first on OUPblog.

Cultural origins of residency training

Given the highly scientific and technical nature of medical practice, it is tempting to assume that the system of residency training developed in response to intellectual forces within medicine. There is much truth to this. After all, the need to learn scientific concepts and principles, to develop skills of critical reasoning, to acquire the capacity to manage uncertainty, to master technical procedures, and to learn how to assume responsibility for patient care all reflected powerful professional demands.

However, residency training in America also developed within a specific cultural context. These cultural forces indelibly shaped the system as well. Their influence was more subtle than those of the internal forces, but it was just as powerful and important.

One important example is that the residency system in the United States developed within a system of charity care. It was this fact that allowed the residency system to provide interns and residents the opportunity to assume responsibility in patient care. The United States, like the rest of the industrialized world before World War II, used indigent patients as “clinical material.” These patients, in keeping with a long-standing Western tradition, received free care in exchange for their participation in clinical education and research. Paying patients, in contrast, were used only in limited ways in medical education-for histories and physical examinations, for example, and only then when they granted permission. Only the indigent patients on the “teaching service” afforded house officers the opportunity to develop management plans, make important therapeutic decisions, and perform surgery and other procedures.

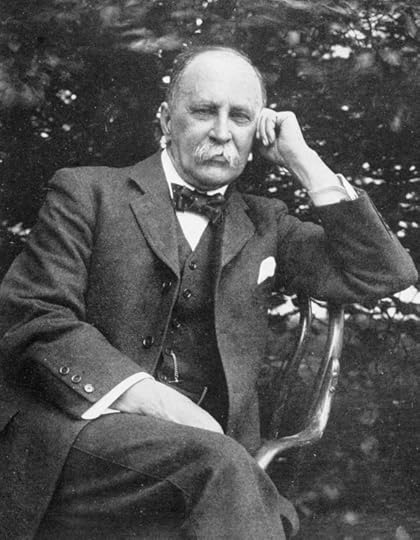

Sir William Osler 1912. Wellcome Library, London. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Sir William Osler 1912. Wellcome Library, London. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Cultural attitudes toward work and family life of the pre-World War II era also helped shape graduate medical education in America. Learning and practicing medicine were demanding activities, often presenting what seemed like 36 hours of work to do in a 24-hour day. William Osler, the iconic professor of internal medicine at Johns Hopkins, called work “the master-word in medicine.” To succeed, doctors needed to focus nearly totally on medicine, to the exclusion of family, friends, hobbies, and a balanced life.

Cultural attitudes of the period supported physicians in their efforts to learn and practice medicine. The United States as a society had always had a high regard for those who could work themselves up to financial and professional success. It was the country’s strong work ethic and entrepreneurial spirit that attracted many ambitious immigrants hoping to leave poverty behind. Moreover, during the creation and early development of the residency system, a strong union movement had yet to arrive, and there were no restrictions on the length of the work day or work week or even on child labor. Accordingly, Americans were accustomed to hard work. Few eyebrows were raised when medical students and house officers threw everything into their training and gave up their twenties for their future.

Attitudes toward marriage and family life reinforced the strong work ethic. Medicine, like virtually all professional fields at the time, was overwhelmingly a male career. Marriage was viewed as women’s work; the physician’s spouse was expected to support her husband, raise the family, manage the household, and take charge of social affairs. As Osler, who did not marry until he was 42, once stated: “What about the wife and babies, if you have them? Leave them. Heavy as are your responsibilities to those nearest and dearest, they are outweighed by the responsibilities to yourself, to the profession, and to the public . . . Your wife will be glad to bear her share in the sacrifice you make.” Such cultural attitudes validated the importance of professional work and undoubtedly influenced the choices and behaviors of almost every physician.

In short, the development of the residency system was influenced by cultural conditions as well as by professional forces. A two-tiered system of health care with an abundance of charity patients provided the “clinical material” with which house officers could learn to assume responsibility for patient care. The strong work ethic of the era, a culture in which delayed gratification was the norm for those aspiring to professional success, and the view that marriage was “women’s work” made it easier for young physicians to submerge themselves in their training and careers. Few medical educators considered these social circumstances in relation to residency training at the time, so much a part of the natural order did they seem. Even fewer contemplated what the implications for residency training might be should social conditions change.

Image: Queensland State Archives 1580 Womens Hospital Ward Eventide Home Sandgate c 1950. Agriculture And Stock Department, Publicity Branch. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Cultural origins of residency training appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers