Oxford University Press's Blog, page 666

May 19, 2015

A sugar & sweets music mixtape

Incorporating the idea of sweetness in songs is nothing new to the music industry. Ubiquitous terms like “sugar” and “honey” are used in ways of both endearment and condescension, love and disdain. Among the (probably) hundreds of songs about sweets, Aaron Gilbreath, essayist and journalist from Portland, Oregon, curated a list of 50 songs, which is included in The Oxford Companion of Sugar and Sweets.

We’ve selected a few from the list and present you with a mixtape of sweet songs:

Do you know any other sweet songs? Let us know in the comments!

Headline Image Credit: Lollipops. Photo by ddouk. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post A sugar & sweets music mixtape appeared first on OUPblog.

Companies House and the £9m typo

Conducting business through a company provides tremendous benefits. The price to be paid for these benefits is disclosure – companies are required to disclose substantial amounts of information, with much of this information being disclosed to Companies House. Every day, suppliers, creditors, potential investors, credit agencies and other persons utilise information provided by Companies House to make informed commercial decisions. It is therefore vital that when Companies House records this information into the register of companies, that it is recorded accurately, with the recent case of Sebry v Companies House [2015] EWHC 115 (QB) providing a stark example of the disastrous consequences that can occur if information is incorrectly recorded.

The case concerned two companies with very similar names. Taylor & Sons Ltd was a successful Cardiff-based company, whereas Taylor & Son Ltd was a Manchester-based company that was experiencing financial difficulties and was wound up in January 2009. Companies House received the winding up order in February 2009 but it was wrongly recorded on the register against Taylor & Sons. The results of the error were catastrophic. Given that Companies House sells information to credit agencies, and anyone can sign up to receive email updates on any company via Companies House’s Monitor service, news of Taylor & Sons apparent liquidation spread very quickly. Suppliers terminated their contracts, creditors refused to provide any more credit, and key customers cancelled their orders with the company. In April 2009, the company entered administration and over 250 employees lost their jobs. Mr Sebry, Taylor & Sons’ managing director, commenced proceedings against Companies House and the Registrar of Companies for negligence and breach of statutory duty.

The case was heard by Edis J in the High Court, with the key issue being whether or not Companies House owed a duty of care to the company. In finding that Companies House did owe a duty of care, Edis J stated that:

“It appears to me that where the Registrar undertakes to alter the status of a company on the Register which it is his duty to keep, in particular by recording a winding up order against it, he does assume a responsibility to that company (but not to anyone else) to take reasonable care to ensure that the winding up order is not registered against the wrong company.”

For two reasons, this duty is a narrow one. First, the duty only arises in relation to the recording of information, and does not extend to verifying the accuracy of information received. Second, the duty is only owed to the company whose records are being amended, and does not extend to third parties who may rely on such information. As this was a preliminary judgment, Edis J did not consider the issue of damages – this will be resolved at a later date, but it was widely reported that the claimant was seeking damages of £8.8 million. Companies House is expected to appeal.

Sebry is an important case as it is the first case to establish that Companies House does owe a duty when registering information provided to it. However, it is important to note that cases such as Sebry will be very rare due to the narrowness of the duty imposed. Another factor that will reduce the likelihood of such claims is that Companies House rarely makes errors. The investigation conducted by Companies House in the wake of the Taylor & Sons error revealed that 99% of information recorded is free of errors. Whilst this is a low error rate in percentage terms, given the sheer number of filings that need to be made to Companies House, even a 1% error rate represents a notable amount of information and, as the Sebry case indicates, even a single seemingly minor error can have disastrous consequences.

Irrespective of whether an appeal is lodged or is successful, Companies House will doubtless exercise more vigilance when updating the register, which will likely result in more company returns and filings being rejected. With nearly 3.3 million companies on the register, there are likely to be many companies with very similar names (for example, there are currently 21 companies on the register with the words ‘Taylor’, ‘Son’ or ‘Sons’ in their name). Coincidentally, five days after the judgment in Sebry was handed down, new legislation came into effect that will actually make it easier to create companies with similar names to existing companies. The Company, Limited Liability Partnership and Business (Names and Trading Disclosures) Regulations 2015 substantially reduces the list of words and phrases that can be disregarded when determining whether a company has a name that is the same as another. Accordingly, it will become even more important for Companies House to ensure that it is registering information against the correct company, lest the disastrous events of Sebry be repeated.

Featured image credit: Lady Justice, by AJEL. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Companies House and the £9m typo appeared first on OUPblog.

May 18, 2015

The final years of Fanny Cornforth

Family historians know the sensation of discovery when some longstanding ‘brick wall’ in their search for an elusive ancestor is breached. Crowds at the recent ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’ exhibition at Birmingham explored the new resources available to assist their research and millions worldwide subscribe to online genealogical sites, hosting ever-growing volumes of digitized historical records in the hope of tracking down their family roots.

These methods and discoveries are proving no less familiar in the updating of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. While the Dictionary is a selective source whose (currently) 59,453 lives are included on the basis of their noteworthiness in the British past, many of its subjects remain—as individuals—obscure, lacking even in the modern period precise details of birth, marriage, and death, which are the basic factual components of Dictionary entries. Their achievements may be described and assessed, yet key information about their lives can remain stubbornly elusive. Celebrity is no bar to gaps in vital data. Charlie Chaplin’s birth was apparently not registered and the exact date and place remain matters in dispute.

The latest update to the ODNB, to be released on 28 May, includes a discovery on an equally visible subject: Fanny Cornforth, ‘artists’ model and intimate companion of Dante Gabriel Rossetti.’ The daughter of a Sussex blacksmith, she sat for many of Rossetti’s best-known works and was part of the artist’s circle who, the Dictionary entry notes, ‘enjoyed Fanny’s high spirits, good nature, and untutored Sussex vernacular.’ Yet for over a century her last years have been a mystery. She received no obituary and on her inclusion in ODNB in 2004, the trail of her life ended in 1905 when, twice widowed, her faculties failing, and in financial difficulties, she was removed from her last known lodgings. ‘There is neither record of her death nor trace of her grave’ was all that could be said.

At the turn of this year the contributor of the Dictionary entry, Christopher Whittick, senior archivist at East Sussex Record Office, made the crucial breakthrough in the recently-digitized manuscript ledgers of the Commissioners in Lunacy, held in the National Archives. These recorded her admission to the West Sussex County Asylum in March 1907, though not under the name Fanny Cornforth, but as Sarah (her baptismal name) Hughes (her first married name). Also as Sarah Hughes her death in the asylum in February 1909 was officially registered. The discovery of her burial in a common grave in Chichester cemetery followed, as did—strikingly—the photograph taken on her admission to the asylum, located among the patients’ case notes now preserved at the West Sussex Record Office.

Such new information is regularly incorporated in the Dictionary’s updates. As well as Cornforth’s death, this May’s ODNB release sheds light on the origins of the bandleader Bert Ambrose (recent research notified to the Dictionary places his birth in Warsaw, Poland, rather than London, as previously thought); it establishes the vital dates of three generations of the Copper dynasty of Sussex folk singers, the subject of a family entry in the Dictionary; and completes the accounts of some individual members of the group of women who attempted to gain professional qualifications from the University of Edinburgh between 1860 and 1873, included in the ODNB group entry on the ‘Edinburgh Seven.’

Such approaches can also extend the range of lives that can be written and included in the Dictionary. A generation ago, attention was drawn to a Victorian historian Georgiana Hill, who in 1896 published an over-arching survey of Women in English Life from Medieval to Modern Times. Library catalogues also identified her as a prolific author of cookery books. Hill was intended as a subject for inclusion in the 2004 edition of the Dictionary, but it proved impossible to disentangle her life using the sources then available. The online census and digitized newspapers have since solved that puzzle. Entries on two namesakes, Georgiana Hill (1825-1903), who wrote a string of cookery titles in the 1860s from her home on the Hampshire/Berkshire border, and Georgiana Hill (1858-1924), a South London journalist, writer on women’s history, and advocate of women’s role in administering relief to the poor, were added to ODNB in 2014—and library catalogues can at last distinguish the two.

As the ODNB brings previously obscure or conflated lives more sharply into focus, the challenge is to place them in context. The year of Fanny Cornforth’s admission to the West Sussex asylum marked a doubling, within the space of a generation, of the number of individuals classified as lunatics, a trend for which contemporaries pondered explanations, whether medical, social, or administrative. Her period as a ‘pauper’ patient coincided with the protracted debates on the British poor law, focussed on the sittings of a royal commission. And her death came just weeks after the first state old age pensions were paid to men and women over the age of seventy (Fanny had by then turned seventy-four though her status as a pauper asylum inmate would have disqualified her from receiving it). So while the recovery of Cornforth’s final years offers a formal closure for the biography of a mid-Victorian artists’ model, it opens up an individual perspective on some of the questions of public policy being contested on the national stage in the new century.

Image Credit: “Fair Rosamund, modelled by Fanny Cornforth” by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The final years of Fanny Cornforth appeared first on OUPblog.

May 17, 2015

What’s so fascinating about plants?

On 18 May, plant lovers around the world take part in “Fascination of Plants Day” to raise awareness of the importance of plant science to our lives. Well, what is so fascinating about plants? We asked some of our authors and editors to share why they think plants are fascinating and why they are worth studying.

* * * * * * * * *

‘Fascination is the right noun to summarize my thoughts about plants: from enjoying entire ecosystems in the wild, to the beauty and flavours of the individuals, to understanding their growth, reproduction, cell biology and genomes. Of course, plants are the source, direct or indirect, of all the food we eat, and plants fixed the carbon for 88% of all the energy we use in biomass and fossil fuels. I enjoy the range of challenges, requiring continuously changing approaches, to study plants in the lab, and the opportunity to choose the crops and wild species we work with in the field, as well as the number of collaborations with people from throughout the world. It is very satisfying when your work can have both intellectual and applied outcomes in the ways that crops can be improved as crops and plants safeguarded in the environment.’

—Pat Heslop-Harrison is Professor of Plant Cell Biology and Molecular Cytogenetics at the University of Leicester and Chief Editor of Annals of Botany.

* * * * * * * * *

‘For me, it is in their endless ability to come up with new solutions to all the problems of life while rooted to the spot. This is most apparent when you think about flowers and reproduction. Plants have to meet a mate and exchange gametes without themselves moving – so they recruit animals to do the work for them. And the endless forms of flowers are a series of responses to the challenge of attracting the interest of enough animals of the right kind. You can see this clearly when you look at the different colours, textures, shapes, sizes, scents and patterns that have evolved to advertise flowers to different animal pollinators. A particularly fascinating example that we are working on is the South African daisy Gorteria diffua, which has hit on the great idea of attracting male flies to pollinate it by pretending it already has female flies sitting on its petals – the development of these fly-mimicking spots is a really exciting problem that we’re trying to solve in the lab.’

—Beverley Glover is Director of Cambridge University Botanic Garden and author of Understanding Flowers and Flowering.

* * * * * * * * *

‘As a child, I was mesmerized by the fantastic colors and shapes of flowers. Poets and artists of all stripes have found endless inspiration in them as well. Who needs a psychedelic drug if you have flowers? My childhood fascination with columbines, morning glories, and poppies later evolved into a question: why are there so many different kinds of flowers? Charles Darwin, known best for his theory of evolution, asked the same question. He demonstrated over and over again that the varied colors, shapes, and smells of flowers are finely-tuned adaptations for conning the birds and the bees (not to mention the moths and the bats) into transporting their pollen. Delving deeper into the lives of plants, one finds great variation in their less flamboyant parts as well, all of which has meaning. The long, straight fibers of papyrus stems, the nicotine that permeates the tobacco leaf, the lightness of balsa wood (and the heaviness of mahogany), and the rapid regrowth of grass after mowing can all be explained as adaptations that enhanced the survival of their ancestors. Every tiny feature of a plant has a story, and the great excitement of being a botanist is in uncovering those stories.’

—Frederick B. Essig is Associate Professor Emeritus at the University of South Florida, author of Plant Life: A Brief History.

* * * * * * * * *

‘While it can be hard to see the forest for the trees, trees and the forests they create are fascinating and important for a host of reasons. Tree stems contain lignin, which provides strength to the wood. Lignin allows tree trunks to withstand the enormous tensions required to pull water from soils up to the leaves, which are often tens of meters in the air so they can reach the light needed to fix CO2 (and simultaneously shade out nearby, shorter trees). But the strength of wood also makes it a perfect building material for humans: global exports of forestry-based products were worth $246 billion U.S. dollars in 2013. And while from a tree’s perspective, stems transport water to enable tiny stomatal pores on the leaf surface to open, letting CO2 in at the inevitable cost of water loss from the cells inside the leaf, the cycling of water through forest systems helps provide clean drinking water (and reduces water treatment costs!) for human users downstream. So, while studying how trees function is fascinating in its own right, it’s also in our own selfish interest to promote research in tree physiology.’

—Danielle Way is Assistant Professor of Biology at Western University, Canada, editor of Tree Physiology, and author of a number of articles including Tree phenology responses to warming: spring forward, fall back?

* * * * * * * * *

‘Plants sustain all life on this planet: they give us oxygen, food, water, shelter, and endless sources of beauty and delight in an extraordinary diversity ranging from tiny wolffia to 300 feet-high redwood trees. Wander in a forest in spring time breathing in the scent of a thousand bluebells, listening to the wind in the tree-tops, feeling the softness of moss underfoot, and catching glimpses of all the wildlife that live there, and you start to understand and appreciate the true fascination of plants, the backdrop to the world that we take for granted, but without which life as we know it would be impossible.’

—Lucy Nash is Assistant Commissioning Editor for Biology and is inspired by such iconic bluebell woods (and books about woods) as Wytham Woods.

* * * * * * * * *

Why do you think plants are fascinating? Let us know using the comments below.

Image Credit: “Photo of a field of oilseed rape canola by rotofrank.” Used with permission.

The post What’s so fascinating about plants? appeared first on OUPblog.

The dangers of evolution denial

As the 2016 presidential election season begins (US politics, unlike nature, has seasons that are two years long), we will once again see Republican politicians ducking questions about the validity of evolution. Scott Walker did that recently in response to a London interviewer. During the previous campaign, Rick Perry answered the question by observing that there are “some gaps” in the theory of evolution and that creationism is taught in the Texas public schools (it isn’t, of course). In the campaign before that, Mike Huckabee went further, asserting that humans were the “unique creations” of God, and not descended from other animals.

Statements such as these should simply disqualify a candidate from public office. Why would we want a leader who is willing to ignore established facts? After all, no reputable scientist disputes the validity of evolutionary science. The politicians who reject it, however, generally do so by invoking their religious beliefs, and most reasonable people (that is, people who recognize that evolutionary science is valid) want to respect the religious beliefs of others. The way they usually resolve this conflict is to suggest that Christianity is not inconsistent with evolution, as long as you don’t read Genesis is a mindlessly literal way. But that’s too easy a response; in fact, there is an inconsistency, and the way many Republican politicians respond to it makes them even more unfit to be our leaders.

Charles Darwin, age 51. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Charles Darwin, age 51. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. The process of natural selection that Darwin discovered (many people already believed in evolution but didn’t know how it occurred) reveals an apparently godless world. Christian doctrine had a well-developed theory to explain the multiplicity of animal life — it was called the Great Chain of Being. If God only does what is best, Christians wondered why, having created angels, why he created obviously inferior humans. And why, having created humans, did he then create banana slugs? The answer was that multiplicity is better than uniformity, and you can’t have multiplicity unless there are some things that are lesser than others. But, the theory went on to assert, everything fit together in God’s overall plan. Everything had its appointed place in the harmonious totality, the Great Chain of Being.

The natural selection process that Darwin discovered reveals an entirely different kind of world. It is a world a savage conflict and merciless competition, where the weakest members of a species perish and only the fittest survive. It bears little resemblance to any world that one can imagine being created, as a unified whole, by an all-controlling, benevolent deity. In fact, responding to the shock of Darwin’s discoveries, many political and social theorists decided that we must dispense with benevolence entirely. Life is intrinsically a struggle for survival they said. Nations that are weak will perish. Public policies that protect or reward the weak will inevitably fail, or will undermine the nation that adopts them and lead it to lose out in the competition with its rivals.

That is simply the wrong lesson to derive from Darwin’s theory, however. We are not compelled to reiterate the natural struggle for survival any more than we are compelled to live in naturally occurring caves, or on the open savanna. The true glory and grandeur of humans, as a species, or America, as a nation, is the regime of justice, kindness and mutual support that we have created for ourselves. We did so in the face of, and in opposition to, the cruelties of nature and the primordial struggle for survival. At the most basic level, the task of any leader we elect is to maintain and extend that victory. A politician who ignores the Darwinian realities of the natural world is likely to fail at that task. He is likely to endorse “days of prayer for rain” as Rick Perry did in 2011 instead of addressing water conservation, or declare, as did Jim Inhofe, that “God’s still up there. The arrogance of people to think that we, human beings, would be able to change what He is doing in the climate is to me outrageous.” Our nation needs leaders who recognize harsh realities and respond to them in an effective, rational manner, not ideologues who invoke God to deny established truths.

Featured image: Evolution-des-wissens By Johanna Pung. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The dangers of evolution denial appeared first on OUPblog.

Female service members in the long war

We are still in the longest war in our nation’s history. 2.7 million service members have served since 9/11 in the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Thousands have been killed, tens of thousands wounded, and approximately 20 to 30% have post-traumatic stress disorder and/or traumatic brain injury.

For many years, approximately 15% of the active duty force have been female. Of those deployed to the wars since 9/11, it is a slightly smaller fraction, at 10%. Too little attention has been paid to the specific strengths and needs of female service members.

Most of it is primarily paid to two issues: (1) sexual assault in the military; and (2) the repeal of the Combat Exclusion Rule. The latter opens up all Military Occupational Specialties (MOS) to women. The media focused on sexual assault in the military for many years (although recently attention has turned to sexual assault on college campuses). Now much reporting is given to whether women can pass various strenuous trainings, formerly only open to men.

There is no question that that these are important issues, but there are many others which trouble active duty females.

If you are in the “field” (e.g. a training exercise or deployed environment), the ever important question is of bathrooms. By bathrooms, I mean a place to urinate or defecate. Sounds simple, but often the Porto-potties are overflowing or, as in Somalia, the only two female latrines are overwhelmed.

The genito-urinary anatomy of women is different than men. This sounds very basic, but to remind the reader: women usually sit down to go urinate, as well as defecate. They have shorter ureters, and are more susceptible to urinary tract infections.

When you are wearing all your “battle-rattle” — helmet, TA-50 (straps over the uniform to hold everything on), Kevlar vest, weapon, etc. — you cannot simply lay it on the ground when you get to a place to relieve yourself. Men don’t need to take it all off, women do (except for the helmet).

I remember being about to go on a twelve-mile road march to attain a much coveted Expert Field Medical Badge (EFMB), in Camp Edwards, Korea. I had a buddy hold my gear. The Porto-potties had feces on the seat. So I squatted, which I had learned to do, but it was disgusting. (I also succeeded in the road march and got my badge.)

American women in World War II. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

American women in World War II. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons In Bosnia and Iraq, there were bombs at the side of the road and female service members avoided drinking too much water, so that they did not have to relieve themselves. However, this could lead to dehydration and urinary tract infections, bad things either in training exercises or on the battlefield.

The vast majority of female service members are of child-bearing age, here loosely defined as 18 through 40. Reproductive issues thus are critical, including pregnancy, child-bearing, and breast-feeding. If you are pregnant, you have modified duties and physical fitness tests, and cannot deploy to war or other austere environments. However, after giving birth, you may deploy after six months.

If you have had a Cesarean section, are you able to do enough sit-ups six months later, to pass your physical fitness test? What about exposures from petroleum, if you are a fuel handler, during pregnancy or breast-feeding? If you want to maintain breastfeeding for a year, but are sent to the field, how do you do that? Once you are finally a mother, who do you leave your children with, when you go back to the battlefield? If you are wounded, how do you maintain your self-image of being attractive?

Fortunately all of these challenges are surmountable, with enough discussion and planning. There are many other issues of course, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, traumatic brain injury, and intimate partner violence, which are harder than bathrooms or lactation rooms. They must also be discussed and planned for.

Women are an essential part of the military. We need to know how to make them, and the military as a whole, totally successful.

Featured Image: Four F-15 Eagle pilots at Elmendorf Air Force Base, Alaska,. U.S. Air Force photo by Tech. Sgt. Keith Brown. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Female service members in the long war appeared first on OUPblog.

Philosopher of the month: Søren Kierkegaard

This May, the OUP Philosophy team are honouring Kierkegaard as the inaugural ‘Philosopher of the Month’. Over the next year, in order to commemorate the countless philosophers who have shaped our world by exploring life’s fundamental questions, the OUP Philosophy team will celebrate a different philosopher every month in their new Philosopher of the Month series.

Søren Kierkegaard (5 May 1813 – 11 November 1855) was a Danish philosopher, theologian, and the father of existentialism. At the age of 17, Kierkegaard enrolled at the University of Copenhagen where he was awarded a degree in theology. He is widely known today for his critiques of Hegel and the Lutheran state church. Kierkegaard believed Hegelianism attempted to put man in the place of God and ignore that human judgment is subjective. He rejected collective thinking and stressed the importance of the individual’s religious experience. Although little attention was paid to his work until the late 19th century, Kierkegaard’s preoccupation with the self and existence made him immensely popular in the 20th century. By affirming that one can only know God through a ‘leap of faith’ and not through doctrine, Kierkegaard is considered by many as the father of modern existentialism. His major works include Enten-eller (1843, translated as Either/Or: A Fragment of Life, 1944), Afsluttende Uvidenskabelig Efterskrift (1846, translated as Concluding Unscientific Postscript, 1941), and Sygdomen Til Døden (1849, translated as The Sickness unto Death, 1941). You can learn more about Kierkegaard’s life and major works in the timeline below:

Keep a look out for #PhilosopherOTM across social media and follow @OUPPhilosophy on Twitter for more Philosopher of the Month content.

Featured image credit: Copenhagen, by vic xia. CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Philosopher of the month: Søren Kierkegaard appeared first on OUPblog.

May 16, 2015

Getting to know Sara McNamara, Associate Editor

From time to time, we try to give you a glimpse into our offices around the globe. This week, we are excited to bring you an interview with Sara McNamara, an Associate Editor on our Journals team in New York. Sara has been working at the Oxford University Press since September 2012.

When did you start working at OUP?

I joined OUP in September 2012. I had spent the previous year working as an adjunct professor at Hofstra University and John Jay College after completing my Ph.D. in philosophy at Stony Brook University in 2011.

What’s the most surprising thing you’ve found about working at OUP?

Prior to joining Oxford University Press, having both a background in academia and previous experience working on a bioethics journal, I would have said that I had an above average understanding of OUP as an academic publisher. It was, therefore, startling to learn how little I knew, not just about the full size and scope of OUP’s products and publishing operations but also about the global business of academic publishing. There is much I still need to learn about this innovative and competitive industry.

What is your typical day like at OUP?

There are very few ‘typical’ days in journals publishing. Because I am responsible for overseeing the operations of multiple journals, with editorial, production, and marketing team members located across the country, each day can be very different. On the days when I am in the office I spend a lot of time on email, communicating with clients and coordinating with the different OUP staff members dedicated to each journal, and in meetings, discussing company- or department-wide initiatives/developments or working on an upcoming presentation. I also frequently spend time away from the office, traveling to meet with journal stakeholders or to attend academic conferences.

“Sara McNamara, Editorial Assistant.” Photo by the Oxford University Press.

“Sara McNamara, Editorial Assistant.” Photo by the Oxford University Press.What’s the most enjoyable part of your day?

Spending time with the other members of the Journals team is the most enjoyable part of my day. Whether we are together working on a project or presentation, or goofing around during a moment of down time, I am always pleased and proud to be part of such a talented, passionate, and fun group.

What is the strangest thing currently on or in your desk?

Though it is a new addition to my desk at OUP, my Sigmund Freud action figure has adorned desks of mine for over a decade. My college friends and I each bought an action figure as an emblem of our shared appreciation for Freud’s work. Now, I keep it both for its sentimental value and as a good luck charm.

What are you reading right now?

I do not typically read multiple books at once, but when friend and OUP colleague Robert Repino’s debut novel Mort(e) was released in January I started reading it immediately, even though I was already in the middle of Dan Jones’ The Plantagenets: The Warrior Kings and Queens Who Made England. I am thus alternating between Mort(e) in print and The Plantagenets on my Kindle. I am also listening to the audiobook of Edmund Morris’ fabulous The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt on my walk to and from work.

What’s your favorite book?

Pride and Prejudice is my favorite novel. I have a particular fondness for epic historical fiction (e.g., War and Peace), but nothing can ultimately compete with this work of Jane Austen for the first place in my heart.

What is your favorite album?

Neutral Milk Hotel’s haunting masterpiece “In the Aeroplane Over the Sea” is one of the best albums of all time. It is beautiful and evocative, and every time I listen to it I am transported to the dreamlike, melancholic world created by singer and songwriter Jeff Mangum’s voice and lyrics. I was able to see Neutral Milk Hotel perform most of the album when they played in Brooklyn this summer, and it was easily the best concert I have ever attended.

If you were stranded on a desert island, what three items would you take with you?

Since I am convinced that I could survive almost anything as long as I have reliable access to multiple seasons of The West Wing, I would bring my iPad, a solar power kit, and something sensible like a survival knife.

What is your favorite word?

My favorite word is the one that hovers on the tip of your tongue, or floats just at the edge of your brain. It is the word that perfectly captures the exact thing you want to communicate in that particular moment. There is nothing better than the feeling you get when that elusive world finally fully materializes in your mind.

Image Credit: “Books” by Curtis Perry. CC BY NC SA 3.0 via Flickr.

The post Getting to know Sara McNamara, Associate Editor appeared first on OUPblog.

Edward Jenner: soloist or member of a trio?

This month marks 266 years since the birth of one of the most celebrated names in medical discovery. Edward Jenner, credited with the discovery of the smallpox vaccination, was born on 17 May 1749 (6 May by the Julian calendar, still in use in England by a quirk of anti-papal authoritarianism until 1752) in the village of Berkeley in Gloucestershire, England. He went to school in Wotton-under Edge and Cirencester, and between the ages of 13 and 21, studied surgery as an apprentice in Chipping Sodbury under the surgeon apothecary Daniel Ludlow, and later the country surgeon, George Hardwicke. He then took a position at St George’s Hospital in London under the wing of the well-known ‘scientific surgeon’, John Hunter. In 1772 Jenner returned home to Berkeley where he became practitioner and surgeon to the local community.

He was only 23 years of age, but had amassed nine years of knowledge and experience in dissection and investigation, an extraordinary erudition for one so young. Jenner’s interest in the smallpox disease may have been sparked during his earlier apprenticeship with Ludlow and Hardwicke where it is said (not everyone agrees) that he came across the dairy maid folklore ‘If I am exposed to and succumb to cowpox I will never get smallpox’. A well-known 17th century nursery rhyme, combined with some poetical exegesis, supports perhaps this folklore assertion “Where are you going to my pretty maid? I’m going a milking sir, she said… What is your fortune my pretty maid? My face is my fortune sir, she said”. (Weiss, R.A. & Esparza, J. 1755)

Smallpox and its treatment

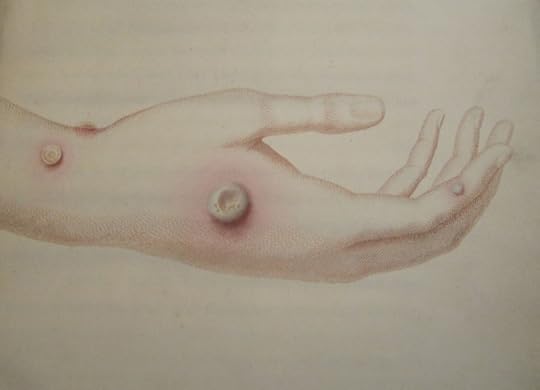

Image courtesy of Dr Jenner’s House, Museum, and Garden

Image courtesy of Dr Jenner’s House, Museum, and GardenDuring the 18th century, smallpox claimed around 400,000 lives per year in Europe. Of the survivors a third became blind. Although the method of variolation (Lat. varius = spotted or stained), in which fluid from a live smallpox sore was injected into individuals subcutaneously, had been known for some hundreds of years its adoption in Europe only began after a series of procedures had been carried out initially on members of the English aristocracy and then in a more controlled set of trials on Newgate prisoners and later orphaned children, with some success. By 1757 Jenner, now eight years of age, became a beneficiary, along with thousands of other English schoolboys of the vastly superior ‘Suttonian’ method of smallpox ‘inoculation’, developed by a Suffolk surgeon Robert Sutton, and later improved by his son Daniel. In this procedure a shallow stab with a lancet dipped in smallpox matter was made, penetrating only about a millimeter or so into the skin. This reduced the severity of post-inoculation symptoms but conferred immunity as effectively as earlier procedures and, despite clear cut differences in the morbidity statistics on natural exposure to smallpox (anything from 1-15% of those infected) and the Suttons’ inoculation exposure (perhaps lower than one in a thousand), the widely practiced Sutton procedures were not published until 1796.

Vaccination or variolation?

Jenner’s analytical approach to the relationship between exposure to cowpox and the subsequent immunity to smallpox, is reflected in his report of 23 case studies involving individuals or groups of individuals 1. who had been exposed naturally to cowpox and then smallpox, 2. who had been naturally exposed to cowpox and were then variolated, and 3. those who had experienced neither infection and were then inoculated with cowpox followed by smallpox. The first of the case studies appear to have occurred in 1743 but it was only the last seven of these occurring after 1790 that Jenner became personally aware of or involved with. The most famous of these was the case of Sarah Nelms, a milkmaid on a farm near to Berkeley. Reported as case XVI Jenner observes:

“SARAH NELMS, a dairymaid at a Farmer’s near this place, was infected with the Cow Pox from her master’s cows in May, 1796. She received the infection on a part of the hand …. A large pustulous sore and the usual symptoms accompanying the disease were produced in consequence…”

Image courtesy of Dr Jenner’s House, Museum, and Garden

Image courtesy of Dr Jenner’s House, Museum, and GardenJenner was convinced this was a genuine case of cowpox with a clean presentation. Here was the opportunity to test the hypothesis in a rigorous experiment. Jenner identified a young village boy, James Phipps, who had not yet been variolated, and injected the secretions from Sarah Nelms’s sores under Phipps’s skin as “two superficial incisions, barely penetrating the cutis, each about half an inch long…” This was in May 1796 and was the first example of a human-to-human vaccination. Two months later, Phipps was variolated by the same procedure and “… as I ventured to predict, produced no effect. I shall now pursue my experiments with redoubled ardour”. Jenner’s attempt to get his results published by the Royal Society of London failed for ‘lack of sufficient experimental evidence’. His conviction that this was an enormously important medical advance led him to finance the publication himself. This was not enough however to convince the entire medical community. Skepticism abounded until several renowned London physicians supported Jenner’s procedure.

Feature image credit: Edward Jenner vaccinating his young child. Coloured engraving by C. Manigaud after E Hamman, Wellcome Library. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Edward Jenner: soloist or member of a trio? appeared first on OUPblog.

DSM-5: two years since publication

It is now two years since the publication of DSM-5. As one might expect when a widely used manual is revised, some mental health clinicians were worried they would have to learn diagnosis from scratch. But the idea that the fifth edition would be a “paradigm shift” for psychiatry turned out to be hype. Few revisions were really major, although practitioners have to become familiar with some new terminology (such as somatic symptom disorder, neurocognitive disorder, or intellectual deficiency).

Some unanswered questions remain. Just as DSM-5 was published in the spring of 2013, Thomas Insel, Director of the National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH), attacked it, declaring that “psychiatry deserves better.” So what did Insel propose instead? The ensuing controversy gave him the opportunity to promote his own system, the Research Domains Criteria (RDoC). This model, although hardly ready for use in clinical practice, will be required as a framework for all NIMH grant applications. RDoC is an interesting but speculative system that aims to reduce all mental disorders to problems in the “connectome,” i.e., how neurons are wired up. Some consider RDoC visionary, while others think it will add little to the understanding of mental illness. We had similar hopes for the Genome Project, and they were disappointed.

Another question concerns potential disjunctions between DSM-5 and the upcoming eleventh edition of the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), expected in 2017. While ICD is, by treaty, the official system (even in the United States), its coding more or less corresponds to DSM diagnoses. Few clinicians in North America will have read the classification prepared by WHO.

A final question is whether the next edition, DSM-6, will only appear in 20 years, or whether there will be, as originally planned, a DSM-5.1 in the next few years. If there is, it might introduce diagnoses that were not accepted in DSM-5 a second chance. Some of these proposals can be found in Section III of the manual (containing diagnoses requiring further study). There seems no current groundswell of opinion to bring back the concept of risk psychosis. However, since the alternative model for personality disorders was not accepted because research on this model was in such an early stage, its the supporters are actively promoting it through research, in the hope that it will replace the old system retained in Section II.

My guess is that given the expense and trouble of preparing further revisions, DSM-5 will not be revised unless major research breakthroughs are made. I am old enough to remember the fierce arguments over DSM-III, which gradually became accepted, after which criticisms were fairly muted.

Since DSM-5 has all the limitations of previous editions, it should be considered the best we can do at the present state of knowledge. There is no point changing psychiatric diagnoses on the basis of speculation of what we might find in the future. Once we understand the causes of mental disorders, that will be the time for major revisions. Until then, DSM-5 still works–as a common language for clinicians.

Featured image: Narcissus by Caravaggio. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post DSM-5: two years since publication appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers