Oxford University Press's Blog, page 665

May 21, 2015

The missing emotion

Wrath, people say, is not an emotion but a sin; and a deadly sin at that.

Yet anger is just as much an emotion as anxiety or misery. Like them, it is an inescapable part of life; like them, it can be necessary and useful; and like them, an excess can wreck lives. Mental health language, however, has not elevated the extreme into a syndrome comparable to depression or anxiety states. Perhaps if it did we would understand better the good and the ill in us. “Anger control” is widely taught (perhaps more widely than successfully); but why is it uncontrolled? What lies behind it? Aggression might indeed be a behaviour to be learned or unlearned; but what about the variety of emotions that are behind it?

Righteous fury: Righteous fury can make us reformers, as Dean Swift’s “saeva indignatio” made him.

Wrath: Whether justified or not, wrath can — like that of Achilles — change the fates of cities and people.

Tantrums: Tantrums typically, about trivia such as cold food or peanuts served in a bag — make us ridiculous, and sometimes dangerous. Crazy rages are the extreme of tantrums. Charles VI of France (“le Fou”) was afflicted. He flew into such a frenzy while hunting that he killed his companions, and it was a premonition of his decline into insanity.

Irritability: Irritability describes those of us who can’t, or don’t choose to, keep our tantrums in check. Psychiatry regards it as potentially part of depression, or mania, or autism, or ADHD, or indeed most disorders of mental health.

Resentment: Resentment is much more inward than the explosive kinds of anger. It is bitter, hateful, revengeful and enduring. It poisons those who harbour it, and endangers those who occasion it.

Great Day of His Wrath by John Martin. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Great Day of His Wrath by John Martin. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) is a newly minted psychiatric illness, describing a combination of gross irritability and resentment in young people. It has been invented for the American classification scheme (“DSM5”) but not, or not yet, accepted by the international scheme of the World Health Organization.

DMDD is defined in a way to make it a condition arising in young people, but one that can persist into adult life: it should not be diagnosed for the first time before age six or after age 18; and the onset needs to have been before age ten. Most of the features are also seen in oppositional-defiant disorder (ODD), so it is important to recognize that it is conceptualized as a more serious problem than ODD: severe verbal or behavioural temper outbursts at least three times a week, angry mood nearly all the time, all evident in different situations. These are some of the most common reasons for troubled youngsters to come to mental health services. One hope is that the diagnosis will promote good clinical practice – for instance, in discouraging a trend in some countries to over diagnose bipolar disorder in young children; and in allowing proper recognition of the emotional basis of many types of antisocial behaviour. It should allow more focussed research than has been possible previously. It could also give rise to some difficulty for clinical diagnosticians, because of the overlap with other conditions such as agitated depression and ADHD. Guidelines for clinicians and standards for clinical trials will need further development.

Shall we accept this new condition? Will it make a new pathology out of the normal human drive to overcome frustration? Or will it allow us to be more understanding towards children and teenagers who are taking their frustrations out on others — and losing their friends, and sometimes their futures, in the process? Can we understand the biology of the emotional extremes of anger; and might doing so invalidate legitimate rage? DMDD seems likely to put anger extremes into a central position in psychiatry. One thing is clear: it is not just a matter of bad behaviour.

The post The missing emotion appeared first on OUPblog.

Traumatic brain injury in the military

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) has often been called the “signature wound” of the recent conflicts in the Middle East. While some tend to discuss TBI as an overarching diagnostic category, there is a plethora of evidence indicating that severity of TBI makes a large difference in the anticipated outcome. Since the year 2000, slightly less than 10% of all head injuries to service members around the world have resulted in moderate to severe TBI, while most TBIs (about 82.5%) have been categorized as mild in severity. As mild injuries are less obvious than more severe injuries in the acute phase—typically there is little or no loss of consciousness, for example—the US Department of Defense and Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) have taken action to try to prevent missing some of these more subtle injuries.

The screening of returning veterans has become a mandatory component of routine care within VA facilities. Veterans who describe experiences with mild TBI (mTBI) often primarily endorse persisting symptoms like headaches and memory or concentration problems, among other symptoms. One challenge that VA providers face is that persisting symptoms of TBI, such as sleep disturbance, anxiety or depression, and cognitive difficulties, often overlap with those of other problems faced by returning veterans, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Much of the research literature on mTBI in returning veterans has focused on the interplay or distinction between mTBI and PTSD. One of the more interesting frequent findings has been that individuals with mTBI report more distressful psychological symptoms than do individuals with more severe injuries. One potential explanation for this is that individuals with more severe injuries have extensive neurological damage affecting their self-awareness. Another explanation, though, is that persisting mTBI results from a complex array of biological, psychological, and social contributions that are rooted less in neurological damage than in factors specific to the individual and his or her environment.

Soldiers preparing to fold an American flag. Photo by Vince Alongi. CC BY 2.0 via Free Stock Photos.

Soldiers preparing to fold an American flag. Photo by Vince Alongi. CC BY 2.0 via Free Stock Photos.In support of such a perspective, the severity of reported cognitive symptoms has been shown to be associated with depression and PTSD, but not with severity of the head injury itself. In fact, the neuropsychological research on mTBI demonstrates little to no effect of injury on cognitive functioning beyond the first few weeks post-injury, once other variables such as motivation are controlled. Motivation affects the validity of cognitive testing results and is especially important to consider in this population, as about 40% of all evaluation results are ultimately found to be invalid and not representative of the individual’s current brain functioning.

Regardless of the cause of the cognitive complaints, returning US veterans are subjectively experiencing increased problems with memory and attention. Our methods of assessing these symptoms are widening, with the increased use of paper-and-pencil clinical measures in-theater and at home, as well as continued efforts to develop computerized measures that can be easily administered, but currently have questionable reliability and therefore lesser utility. In response to the cognitive and psychological concerns reported by veterans, there are many programs being developed in the military, in the VA system, and in the private sector to help rehabilitate the cognitive symptoms experienced by returning veterans and to help them function better on a day-to-day basis and to achieve the post-deployment goals they have set for themselves.

Featured Image Credit: Soldiers crawling on the ground in basic training. United States Air Force photo by Master Sgt. Scott Reed. Public Domain via Free Stock Photos.

The post Traumatic brain injury in the military appeared first on OUPblog.

The genetics of consciousness

Nipple of a cat. Nose of a pig. Hair of a poodle. Eyes of a baboon. Brain of a chimpanzee. If this sounds like a list of ingredients for a witches’ cauldron, think again, for it’s merely a reminder of how many general characteristics we share with other mammals. This similarity in basic body parts has a genetic basis. So humans and chimps share 99 percent DNA similarity in our protein–coding genes and even the tiny mouse is 85 percent similar to us in this respect. Yet what is most remarkable about human beings is not what we have in common with other animals, but what distinguishes us as a species.

One key human difference is our capacity to shape the world using tools. Although some other species also use tools, what distinguishes humans is the way we have made tool use a systematic part of our lives, as well as the fact that our tools evolve with each new generation. So while there is little sign that the life of a chimpanzee in the jungle is that different from when our two species diverged seven to eight million years ago, in the last 50,000 years humans have gone from living in caves to sending spaceships to Mars.

Another unique attribute of our species is our capacity for language. This capacity is central to our ability to communicate with other humans, but is far more than just a communication system, being also a conceptual framework of symbols that makes our relationship to the world completely different to any other species. It is this that allows us to describe the properties and location of things, what happened to them in the past and might happen in the future.

Such unique features must ultimately be based on differences in the biology of the human brain, and the genetic information that underpins this. Our brains are the most complex structures in the known universe, containing around 100 billion nerve cells joined by some 100 trillion nerve connections. Understanding how human self-conscious awareness arose within this organ, why it is lacking in the brains of our closest biological cousins, and relating this to genetic differences between humans and chimps, is the biggest challenge in biology today.

DNA brain, © comotion_design, via iStock Photo.

DNA brain, © comotion_design, via iStock Photo.Importantly, recent studies have identified major differences in the times at which particular genes are expressed during development of human brains compared to those of chimps. Such differences are especially prominent in the prefrontal cortex, a brain region involved in complex thought, expression of personality, decision making and social interaction. In particular, genes involved in formation of new synapses – the connections between nerve cells – peak in expression several months after birth in chimp prefrontal cortex but only after five years of age in this region in humans. This fits with the fact that human children have a much more extended period of learning than apes, and indicate that our brains are being restructured in response to such learning for a far longer period.

The many differences identified in the patterns of gene expression in the human brain compared to that of the chimp complicates the process of trying to identify the key ones that underlie our unique attributes of consciousness and self-awareness. As such, there is increasing interest in identifying whether these large scale differences reflect alterations in a much smaller number of ‘master–controller’ genes that code for proteins that regulate other genes. One such protein is of interest both because it is a master regulator of synapse formation, and because its action was subtly different in Neanderthals, suggesting that delayed synapse formation was one factor distinguishing Homo sapiens from these proto-humans.

Until recently gene expression was thought to be only regulated by proteins. However, recent studies show that certain forms of RNA, DNA’s chemical cousin, also play a key role in this process. One such regulatory RNA, abundant in the prefrontal cortex of humans, but not of chimps, has been shown to be an important regulator of nerve stem cell proliferation. This is interesting since neurogenesis – the growth of new neurons from such stem cells – is important not just during embryonic brain development, but is increasingly being recognised as an important process in the adult human brain.

Such a reassessment of the importance of RNA as a regulatory molecule is only one way our concept of the genome is changing. So we are also recognising that far from being a fixed DNA ‘blueprint’, the genome is a complex entity exquisitely sensitive to signals from the environment. These so–called ‘epigenetic’ signals can affect genome function in a finely graded fashion like a dimmer switch, and even have a built–in timing mechanism due to the fact that different genome modifications can be reversed at different rates. All this makes this type of gene regulation ideally suited for involvement in the complex processes of learning and memory. And indeed recent studies have shown that interfering with epigenetic changes in brain cells has profound effects on memory and learning processes in animal models.

Perhaps most surprisingly the genome’s very stability is being called into question, with evidence that genomic elements called transposons, can move about, sometimes to the detriment of normal cellular function, but also acting as a new source of genome function. Intriguingly, the hippocampus, a brain region associated both with memory formation and forming new nerve cells through neurogenesis, is particularly prone to transposon activity.

Some scientists believe increased transposon activity could either change human behaviour allowing the individual to become more adaptable to a new environment, or alternatively increase the risk of mental disorders, depending on the particular environmental pressure. This would challenge the long–held idea that at the genomic level, all cells in an individual’s brain are essentially equivalent. Instead, an individual’s life experience may profoundly the genomes of different brain cells, and even identical twins may differ considerably in their brain function, depending on their particular experiences in life.

In studying how epigenetic information might be transmitted to the genome, the main focus has been upon adverse effects such as stress. So, a recent study showed that telomeres, the protective structures at the ends of our chromosomes, can shorten much more rapidly in some children exposed to extremely stressful situations. But there are also tantalising hints that more positive life events might have a beneficial effect upon the brain through an epigenetic route.

Most controversial is the question of whether epigenetic effects upon the genome can be passed down to future generations. In particular, the finding that effects of stress in mice can be passed on to offspring by a route involving regulatory RNAs that may originate in the brain, and travel in the blood to the sperm, suggests that the connection between the sex cells and the rest of the body, particularly the brain, may be more fluid than previously thought.

Such findings have led epigenetic researcher Brian Dias of Emory University, Atlanta, to recently say that ‘if science has taught me anything, it is to not discount the myriad ways of becoming and being’. All of which means that for those interested in the complex nexus of biological and social influence, even more exciting findings undoubtedly lie ahead.

The post The genetics of consciousness appeared first on OUPblog.

May 20, 2015

Putting one’s foot into it

Last week, I wrote about the idiom to cry barley, used by children in Scotland and in the northern counties of England, but I was interested in the word barley “peace, truce” rather than the phrase. Today I am returning to the north, and it is the saying the bishop has put (or set) his foot in it that will be at the center of our attention. Both bishop and foot, deserve special posts, but they will have to wait: one for an explication of its strange phonetics, the other for laying bare its Indo-European roots.

Here is the relevant context for the bishop-and-foot idiom, as it was given in 1876:

“[The phrase] is used by farmers’ wives and cooks, who have pretty frequently occasion to boil milk to prevent it from spoiling…. Whatever care may be taken, it is sometimes very difficult to boil it without burning it…. When such a mishap occurs, the wife or a cook will say, ‘The bishop had a foot in it’.”

This odd phrase has been discussed many times, and my search on the Internet has shown that I don’t have more sources of information than that omniscient machine. But perhaps our readers do. In any case, the saying has never been explained to everybody’s satisfaction, and I have one or two feeble ideas to offer. Incidentally, when the same “mishap” ruins broth, porridge, or pudding, the result is laid at the door of the same mysterious miscreant. Mulled port is also called “bishop.”

The examples of the idiom in texts don’t antedate the sixteenth century, or, to be more precise, Thomas Tusser’s amusing and edifying poem Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry (my spelling of the title is modernized). Tusser devoted a good deal of attention to cheese and explained what good cheese should not be. The section “Lesson for Dairy-Maid Cisley” opens with a proem from which we learn, among a few other things, that “bishop… turneth and burneth up all.” The special couplet on this subject reads so: “Bless Cisley (good mistress) that bishop doth ban / For burning the milk of her cheese to the pan.” Cisley must have been a name popular among the women belonging to “the lower orders” and thus servants. If I understand the couplet correctly, good mistress is a form of address, and Tusser apostrophizes the lady who employs Cisley, while bless and ban mean “forgive” and “curse” respectively: “Good mistress, forgive your maid Cisley, who burned the milk. She is not to blame: it was the bishop who caused the damage.” However, in the verse there may have been a double entendre we no longer hear (see below).

Tusser (ca. 1524-1580) was born in Essex, and later we find him in Oxfordshire, London, at Eton, and in Suffolk, while in the modern period the idiom that interests us was popular in Derbyshire and more to the north. But sixteenth-century poets wouldn’t have used the language that their readers were unable to understand. For example, when Shakespeare said (in Macbeth and King Lear) aroint thee, he must have relied on an audience at the Globe that knew what he meant. (Now aroint seems to be limited to Lancashire.) Likewise, we should probably conclude that in Tusser’s days the reference to the bishop and burned milk had wider currency than it did three hundred years later. All attempts to find the origin of the idiom have so far failed. The great William Tyndale wrote in his book The Obedience of a Christian Man (1528; this is an often-quoted passage; it will be reproduced below in its original orthography):

“When a thinge speadeth not well [does not succeed] we borrow speech and say the byshope hath blessed it, because that nothinge speadeth well that they medyll withal [meddle with]. If the podech [porridge] be burned to, or the meate ouer rosted, we saye the byshope hath put his fote in the potte, or the byshope hath playd the coke [cook]. Because the bishopes burn who they lust and whosoever displeaseth them.”

Several tentative conclusions can be drawn from this severe statement. First, it may not be too rash to suggest that at the beginning of the sixteenth century foot and pot almost rhymed; foot still had the vowel of Modern Engl. awe and differed from the short o of pot only in length. The alliterative idiom ran somewhat like to put the “fawt” in the pot and was equivalent to the modern put one’s foot into it. In the Protestant camp, Catholic bishops must have been accused of ruining and destroying things. The only remnant of that usage seems to be the ridiculous idea that bishops were responsible for burned food and, much less certainly, the verb bishop “to make an old horse look young.” The conclusion that burned milk, porridge, and the rest is due to bishops’ cruelty because those people burned heretics cannot be taken seriously: the contexts, one grim, the other almost humorous, do not match.

Is this bishop at fault?

Is this bishop at fault? Two folk-etymological explanation of the idiom exist. Allegedly, in the pre-Reformation days the country people used to go out of their houses to ask the bishop’s blessing when he passed through a village, and in their hurry they would leave the boiling milk to be burned. This derivation looks like pure fantasy. Jonathan Bouchier (1738-1804), a serious philologist, also cited another explanation, namely that the phrase “was a popular allusion to the Bishops Gardiner and Bonner, of fiery disposition.” Naturally, he found that connection improbable. It seems that the Protestants ascribed all evil deeds to Catholic bishops, and the idiom reminds us of that attitude. Despite occasional references to broth, pudding, and so forth, the association with milk is surprisingly stable.

As usual, irritating snags appear in the most reasonable conjectures about etymology. The same remark (about cooks running out for a blessing and leaving the food to burn) has been recorded in French Flanders, a fact that is harder to connect with the Reformation. Moreover, French pas de clerc “the priest’s foot” means “a blunder caused by ignorance or ineptitude.” In the Middle Ages, Scotland had strong ties with France, and therefore Scots is full of French borrowings. The French phrase could have migrated to Scotland and northern England and to the midlands and received a reinterpretation in the sixteenth century. There does not seem to be an English analog of pas de clerc, so that the English idiom is hardly a direct rephrasing of the French one. All over Europe, people commented on the poverty and incompetence of priests in worldly matters.

I have only a short remark to add to what has been said above. It concerns a possible double entendre. Tusser wrote: “Blesse Cisley (good mistress) that bishop doth ban.” In this line, bless might have had the opposite (ironic) meaning, so perhaps the injunction was: “Curse the maid already cursed by the bishop.” But this is unlikely, even though I don’t quite understand why a maid who spoiled a dish should be blessed.

Image credits: (1) Burnt milk. © esvetleishaya via iStock. (2) A bishop from the set of medieval Lewis chess pieces. Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh. Photo by Jim Forest. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via jimforest Flickr.

The post Putting one’s foot into it appeared first on OUPblog.

Edward Jenner: soloist or member of a trio? Part 2

In 1805 a Dorset farmer, Benjamin Jesty arrived in London on an invitation from the Original Vaccine Pock Institute to describe his cowpox vaccination procedure on his own family which included a real time inoculation of his son Robert with smallpox. This new institute was formed by the anti-Jenner physician George Pearson in an attempt to shift the credit for vaccination discovery away from Jenner. Despite the prevailing view amongst Jenner supporters, it was clear from the records at the time that Jesty had carried out his vaccine attempts some 22 years before Jenner’s experiments with Sarah Nelms and James Phipps, yet until 1805 had been essentially unrecognized. On the basis of this some writers have sought to ascribe the invention of vaccination to Jesty.

What is evident however is that while vaccinating his family with cowpox secretions, Jesty appears not to have immediately followed that up with variolation, a sine qua non for proof of any hypothesis on the cowpox protective effect. A further intriguing fact is that a third surgeon and older colleague of Jenner, John Fewster who lived in a village near to Berkeley, also appeared to have made the connection between cowpox exposure and smallpox immunity. It has been suggested he presented a paper to the London Medical Society in 1765 entitled “Cowpox and its ability to prevent smallpox” but no evidence of that exists (Jesty and Williams). Fewster had a lucrative business in variolation the financial success of which may have led him to downgrade the importance of the cowpox approach. On the other hand, as a colleague and young apprentice member of the same local medical society where Fewster discussed his observations that individuals exposed to cowpox were ‘uninfectable’ with smallpox, it would be surprising if Jenner had not taken on board the connection. So, in chronological order, Fewster, Jesty, Jenner. Equal members of a vaccination trio or professional soloist and amateur accompanists?

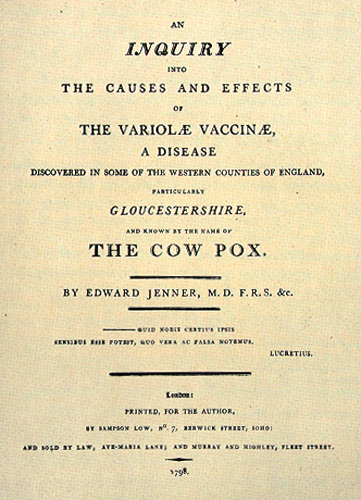

Edward Jenner Book. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Edward Jenner Book. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. As Sir Francis Darwin observed, “In science credit always goes to the man who convinces the world, not the man to whom the idea first occurs”. (Darwin, 1914).

Is this principle supportable even if common today? In discussing the problem of attribution of credit (also quoting Francis Darwin), Sir William Osler, commenting on the discovery of anaesthesia attributed to William Morton in 1848 observed that, despite many who had practiced or had ideas on anaesthesia, from Diascordes to Hickman in 1844,

“Time out of mind patients had been rendered insensible by potion or vapours, or by other methods, without any one man forcing any one method into general acceptance, or influencing in any way surgical practice.” (Osler, 1917)

Therein perhaps lies the answer to the question that still lingers in the historical literature, with its scientific Whigs and Tories debating the creditworthiness of farmer Jesty’s amateur experiments over Jenner’s scientific method (Pead, 2014). The crucial question it seems to me is not who was first but, had Jesty been the only proponent of cowpox vaccination, would the method have had ‘general acceptance’ and further would it have ‘influenced medical practice’? Even with Jenner’s reputation the vehement objections to the cowpox procedure that included claims that patients receiving the vaccine “rendered them liable to particular diseases, frightful in their appearance and hitherto unknown” (The Jennerian Society, 1809) created serious questions about the efficacy and indeed the morality of the procedure. In assessing the validity of these objections, a report of the Medical Committee of the Jennerian Society on the subject of vaccination, contributed to by “21 Physicians and 29 surgeons of the first eminence in the Metropolis”, was published in the Belfast monthly Magazine in 1809. In addressing the alleged claims, 22 separate statements based on analysis of the information by the committee were made. The conclusion of the report states “that it is their full belief, that the sanguine expectations of advantage and security, which have been formed from the inoculation of the cow pox, will be ultimately and completely fulfilled.”

In the end, credit usually gets to the right place, and there would seem to be only one historically supportable conclusion. Jesty was certainly an intelligent amateur who was first to apply the secretions of cowpox as a protection against smallpox, and Fewster was perhaps closer to being in a position to turn the phenomenon into a generally accepted procedure, but chose to maintain his variolation business for whatever reasons. But it was the painstaking scientific methods and the driven ardour of Edward Jenner that overturned the engrained establishment skepticism and established vaccination as a widely adopted procedure. By 1800, Jenner had provided vaccines to a colleague in Bath, England who passed it to a Professor at Harvard, who then introduced vaccination into New England and with Thomas Jefferson’s mediation, into Virginia. As a result the US National Vaccine Institute was set up by Jefferson. By 1803 it was reported that 17,000 vaccinations had been performed in Germany alone, 8,000 individuals of which had been tested by variolation and found to be immune to smallpox. In France, Jenner was revered by Napoleon for his vaccination impact on the health of the Grande Armée, despite being at war with England. By 1810 or so cowpox vaccination had been adopted in most of Europe, the United States, South America, China, India, the Far East, and many other parts of the globe with outstanding success. All this as a result of Jenner’s almost fanatical belief in the importance of a correct procedure in preparing and administering the cowpox vaccine and critically, his ability to garner support from the highest scientific and medical influences.

Had there been a Nobel Prize committee in 1805, would Jenner and Jesty have shared the prize? We shall never know but it’s mighty intriguing to think about.

This is part two of a series about Edward Jenner and the discovery of the smallpox vaccine. Read part one, “Edward Jenner: soloist or member of a trio? Part 1“, which addresses Edward Jenner’s early education and medical career.

Featured image: The Cow Pock, James Gillray. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Edward Jenner: soloist or member of a trio? Part 2 appeared first on OUPblog.

Where was Christopher Columbus really from?

Of the many controversies surrounding the life and legacy of Christopher Columbus, who died on this day 510 years ago, one of the most intriguing but least discussed questions is his true country of origin. For reasons lost in time, Columbus has been identified with unquestioned consistency as an Italian of humble beginnings from the Republic of Genoa. Yet in over 536 existing pages of his letters and documents, not once does the famous explorer claim to have come from Genoa.

Moreover, all of these documents, including letters to his brothers and various people in Italy, are written in Spanish or Latin rather than in Italian. If Columbus was from Genoa, why wouldn’t he write in his native tongue? Additionally, in official Castilian documents in which his origin should have been specified, he is simply referred to as “Cristóbal de Colomo, foreigner” or “Xrobal Coloma” with no qualifying adjective, when other foreign mariners were invariably identified in royal documents by their places of origin—”Fernando Magallanes, Portuguese,” for example, and “Amerigo Vespucci, Florentine.” Why was that? And when Columbus returned from his first voyage to the New World in 1493, ambassadors to the court of Ferdinand and Isabella from Genoa said not a word about him being one of their countrymen in letters they wrote home.

Not once does the famous explorer claim to have come from Genoa.

Equally strange is the fact that there are no existing documents indicating that Cristoforo Colombo, a master mariner who supposedly discovered America, had any meaningful sailing experience prior to his epic voyage of 1492. What is more intriguing is that this same son of a lowly wool carder was addressed as don, had his own coat-of-arms, and married a Portuguese noblewoman, all before his historic voyage of discovery. This would have been impossible in the rigidly class-conscious Iberian society of the 15th century if Columbus had not himself been of noble birth.

Those who doubt Columbus’ Genoese origin maintain that the reason why he concealed his true origin was because he was a Catalan naval captain who fought against Ferdinand’s cousin, King Ferrante of Naples, in the Catalan civil war of 1462-1472. Many Portuguese fought on the Catalan side in that war, including Peter of Portugal, close relative of the Portuguese king. If this story is true, it explains how Columbus honed his nautical skills prior to his voyage to the New World, how he might have been introduced to the Portuguese noblewoman who became his wife, and why he would have concealed his (Catalan) heritage from the royal couple who sponsored his voyages of discovery.

Image Credit: “Columbus’ expedition by Gustav Adolf Closs (1864-1938).” Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Where was Christopher Columbus really from? appeared first on OUPblog.

Field experimenting in economics: Lessons learned for public policy

Do neighbourhoods matter to outcomes? Which classroom interventions improve educational attainment? How should we raise money to provide important and valued public goods? Do energy prices affect energy demand? How can we motivate people to become healthier, greener, and more cooperative? These are some of the most challenging questions policy-makers face. Academics have been trying to understand and uncover these important relationships for decades.

Many of the empirical tools available to economists to answer these questions do not allow causal relationships to be detected. Field experiments represent a relatively new methodological approach capable of measuring the causal links between variables. By overlaying carefully designed experimental treatments on real people performing tasks common to their daily lives, economists are able to answer interesting and policy-relevant questions that were previously intractable. Manipulation of market environments allows these economists to uncover the hidden motivations behind economic behaviour more generally. A central tenet of field experiments in the policy world is that governments should understand the actual behavioural responses of their citizens to changes in policies or interventions.

Field experiments represent a departure from laboratory experiments. Traditionally, laboratory experiments create experimental settings with tight control over the decision environment of undergraduate students. While these studies also allow researchers to make causal statements, policy-makers are often concerned subjects in these experiments may behave differently in settings where they know they are being observed or when they are permitted to sort out of the market.

For example, you might expect a college student to contribute more to charity when she is scrutinized in a professor’s lab or when she can avoid the ask altogether. Field experiments allow researchers to make these causal statements in a setting that is more generalizable to the behaviour policy-makers are directly interested in.

To date, policy-makers traditionally gather relevant information and data by using focus groups, qualitative evidence, or observational data without a way to identify causal mechanisms. It is quite easy to illicit people’s intentions about how they behave with respect to a new policy or intervention, but there is increasing evidence that people’s intentions are a poor guide to predicting their behaviour.

However, we are starting to see a small change in how governments seek to answer pertinent questions. For instance, the UK tax office (Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs) now uses field experiments across some of its services to improve the efficacy of scarce taxpayers money. In the US, there are movements toward gathering more evidence from field experiments.

In the corporate world, experimenting is not new. Many of the current large online companies—such as Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft—are constantly using field experiments matched with big data to improve their products and deliver better services to their customers. More and more companies will use field experiments over time to help them better set prices, tailor advertising, provide a better customer journey to increase welfare, and employ more productive workers.

Governments deliver many important services to their populations, and these services have implicit costs, advertising, information, and education. Not knowing how these four factors impact on the behaviour of their citizens means that governments are potentially misallocating taxpayers’ money. Using field experiments helps policymakers understand how to causally improve the welfare of their citizens.

Headline image credit: Statistics, by geralt. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Field experimenting in economics: Lessons learned for public policy appeared first on OUPblog.

May 19, 2015

Do we choose what we believe?

Descartes divided the mind up into two faculties: intellect and will. The intellect gathers up data from the world and presents the mind with various potential beliefs that it might endorse; the will then chooses which of them to endorse. We can look at the evidence for or against a particular belief, but the final choice about what to believe remains a matter of choice.

This raises the question of the ‘ethics of belief,’ the title of an essay by the mathematician William K. Clifford, in which he argued that ‘it is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence.’ If people choose what they believe, we can ask when it is morally right or wrong for them to entertain certain beliefs. Clifford’s stern moral position was famously challenged by William James, but not his crucial premise that we choose what to believe. Some philosophers have taken this premise to extremes; Jean-Paul Sartre went as far as to suggest that we are always to blame for our own suffering, since however much the evidence might suggest that our situation is a miserable one, it is always our choice to believe that it really is so.

But do the ‘ethics of belief’ rest upon a false presumption? Spinoza believed so (as was observed by Edwin Curley). He opposed Descartes’ two-faculty psychology. Will and intellect, he argued, are one and the same; as soon as the intellect gathers up its data, the mind is thereby made up on what to believe. We may think we choose what to believe, but this, Spinoza claims, is an illusion arising from ignorance. The human mind grinds out beliefs from the data it receives in a blindly mechanical fashion; in an early work, Spinoza called the mind a ‘spiritual automaton.’ We think of ourselves as free only because we fail to consciously note all the inputs that set the direction of our thought.

Does it make sense to mock, to hate, to be angry with, to disesteem others for their differences of opinion?

Many important things follow from Spinoza’s alternative picture of the mind. People with opposing views cannot disagree because they choose to respond differently to the same data. There must be a difference in the data to which they have access, even if neither is conscious of this. When people disagree with us, there is no point in imploring them to ‘face facts.’ The problem is not that they are refusing to face the facts; it is that they haven’t been exposed to the same facts as us, at least not in the same way.

Similarly, our value judgments, whether truth-apt or not, are straightforward functions of the influences upon us. Exposure to given phenomena will generate a set of value judgements with the certainty of a chemical reaction. It makes little sense to describe anybody’s values as corrupt or perverse. Each person’s values are appropriate in terms of the influences to which she has been subjected; if we wish her values to change, we must subject her to new influences. Thus the doctrine that will and intellect are one and the same, Spinoza averred, teaches us ‘to hate no one, to disesteem no one, to mock no one, to be angry at no one, to envy no one.’

This doctrine was of great importance in Spinoza’s age—the age of religious conflicts. People were condemning each other’s beliefs when, according to Spinoza, they should have been trying to understand the processes producing the divergences. You cannot intimidate somebody into changing beliefs that are the result of processes over which she has no control. The idea of Pascal’s Wager rests upon a misunderstanding of the mind. Even God cannot change our beliefs by offering rewards and punishments; that is like trying to pay somebody not to sneeze.

After an election, like the one we just had in the United Kingdom, I often find myself thinking about Descartes’ and Spinoza’s opposing pictures of the mind. Does somebody who disagrees with me, even while seeming to be exposed to precisely the same facts, just perceive a different world? Or do they choose to believe different things about a world we perceive with equal clarity? Does it make sense to mock, to hate, to be angry with, to disesteem others for their differences of opinion? Or is the burden on us to find out what it is they have failed to notice and show it to them?

The answers hang upon the strength of Spinoza’s arguments against Descartes’ position. My critical analysis of these arguments has been highly favourable. But we are dealing with two philosophical giants, and there is much still to be said on either side.

Image Credit: Photo by secretlondon123. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Do we choose what we believe? appeared first on OUPblog.

Remembering the “good” and “bad” wars: Memorial Day 40, 50, and 70 years on

Memorial Day is always a poignant moment — a time to remember and reflect on the ultimate sacrifice made by so many military personnel over the decades — but this year three big anniversaries make it particularly so.

Seventy years ago, Americans celebrated victory in a war in which these sacrifices seemed worthwhile. When, shortly afterwards, President Harry Truman implemented a plan to find and repatriate the remains of those bodies not yet recovered, he summed up the prevailing mood. The nation, Truman declared, wanted to show its “deep and everlasting appreciation of the heroic efforts” of those who had made the “supreme sacrifice” in such a noble cause. On the day that the first 6,200 coffins arrived from Europe many grieving relatives found it difficult to cope. Some wept openly on New York’s streets, while others could hardly bear to look. One woman screamed “There’s my boy, there’s my boy,” as she stared at a coffin, shaking with emotion.

For the country as a whole, however, World War II caused no real casualty hangover. Unlike other twentieth-century wars, the so-called “good war” certainly failed to engender a sense of never-again that had underpinned the isolationist revulsion to World War I during the 1920s and 1930s — so much so that for twenty years after 1945, successive presidents felt relatively unhampered when deciding to send troops to intervene in faraway conflicts.

Fifty years ago, President Lyndon Johnson was in the process of taking the last fateful last steps toward the most important of these overseas interventions. While the United States had been gradually escalating its involvement in Vietnam for more than a decade, July 1965 marked the decisive point. This was the month when Johnson sent the first of more than half a million troops to defend South Vietnam against the communist assault.

When this “bad war” ended a little over forty years ago, more than 50,000 Americans had been killed. Although fewer in number than the dead in the “good war,” their sacrifices had a far more profound impact on the country as a whole. Indeed, they underpinned the so-called Vietnam syndrome, which has often forced subsequent presidents to think twice about sending large numbers of troops into potentially open-ended and bloody commitments.

US casualties of the Vietnam War (above) elicited a different response among the American people than military deaths during World War II. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

US casualties of the Vietnam War (above) elicited a different response among the American people than military deaths during World War II. CC by 2.0 via Flickr. Why did the nation react so differently to these two wars? On Memorial Day, it is worth considering the importance of how the public was exposed to American casualties at the time. We are often told that Vietnam marked the nadir of government candor: a time when presidents were so mendacious about every dimension of the war, including casualties, that the so-called credibility gap became a yawning chasm. If true, then perhaps the public became so suspicious of official casualty figures that they thought the government was concealing the true cost of the war. But is this argument correct?

Johnson certainly did his best to put a positive spin on American losses, especially with his constant claims that these sacrifices would soon result in ultimate victory. Then, when these claims of progress turned out to be false, more and more Americans did indeed begin to question the veracity of government figures. Yet the importance of this lack of trust needs to be considered against two countervailing facts. One is that, in key respects, Johnson’s government was actually more truthful in revealing US casualties than any other. Each week from the summer of 1965, it issued unprecedented details on American losses, with press releases that included both battlefield and non-battlefield losses, severe wounds as well as injuries not serious enough to warrant a purple heart. The other countervailing fact is that a lack of trust affected the Roosevelt administration, too — and with better reason. Not only did officials during World War II try to conceal the cost of big defeats like Pearl Harbor, but they also failed to release any casualty totals at all during bleak moments of the war, which in turn encouraged the media to publish inflated enemy estimates instead.

If the Vietnam credibility gap has often been exaggerated, what about media coverage of American casualties? According to another common argument, the media during the Vietnam War inflamed the public’s response to casualties. Television is generally singled out as the central culprit, its ability to beam gruesome images into the nation’s living rooms seen as a major change in how the public responded negatively to war. Yet this argument has also been overstated. During the 1960s, the main TV networks invariably depicted combat in an anodyne and antiseptic fashion, partly because cameras were too cumbersome to lug around the battlefield and partly because executives and advertisers balked at the airing of anything too graphic.

American corpses sprawled on the beach of Tarawa, November 1943. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

American corpses sprawled on the beach of Tarawa, November 1943. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Once again, World War II was very different. Although Roosevelt was prepared to mask casualty information whenever the fighting went badly, he went out of his way to encourage visual images of battlefield death at times of victory, convinced that the public had to be jolted out of its complacent conviction that final victory was just around the corner. For this reason, Roosevelt personally authorized the release not just of still images of American dead, but also of a training movie, With the Marines at Tarawa. Based on graphic combat footage, it included film of wounded marines on stretchers and casualty-identification teams at work on the beach. “These are the marine dead,” intoned the narrator toward the end, over pictures of prostrate bodies lying on the sand and bobbing in the shallow sea. “This is the price we have to pay for a war we didn’t want.”

This last sentence offers a major clue to why the two wars actually bequeathed such different legacies. Before the United States fully entered World War II, Roosevelt led a nation that remained desperate to stay out. Only the surprise Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor destroyed the isolationist consensus against sending American troops to fight and die in overseas wars. Johnson never faced a similar moment: there was never a clear-cut case of communist aggression he could point to in order to convince the public that its boys were obviously fighting in self-defense.

Once the United States went to war, Roosevelt also developed a strategy that helped to keep the cost low, at least compared to other belligerents. Although his decision to lean heavily on the Soviet Union became deeply controversial when Stalin emerged as America’s archenemy after 1945, during the war Americans could see that the Red Army was bearing the main burden of fighting and dying to destroy Hitler’s armies. Johnson would have liked nothing better than to let his South Vietnam ally shoulder the main responsibility for fighting the communists, but he could not hide the fact that within a year of massively escalating the nation’s commitment US losses were more than double the amount of the South Vietnamese ally that GIs were purportedly fighting to protect.

Most importantly, seventy years ago World War II resulted in a stunning victory, while forty years ago Vietnam ended in an ignominious defeat. The images Americans received at the very end also shaped their understanding of the purpose of these two wars. Just weeks before Germany’s unconditional surrender, US troops had liberated a series of Nazi concentration camps, whose actual horrors surpassed even the worst depictions of Allied propagandists. At the moment of South Vietnam’s final defeat, Americans left Saigon in such a hurry that they had to abandon their allies to the clutches of a communist regime known for its brutality.

Success was therefore crucial to the way these two wars have been remembered, but so was the morality of the cause. As America remembers its dead, it is tempting to recall President Abraham Lincoln’s stirring words at Gettysburg about whether America’s war dead “have died in vain.” Americans seventy and forty years ago reached very different conclusions about whether the sacrifices in their “good” and “bad” wars had been worthwhile, with consequences that linger to this day.

Featured image: National World War II Memorial, Washington, DC. Public domain via the United States Navy.

The post Remembering the “good” and “bad” wars: Memorial Day 40, 50, and 70 years on appeared first on OUPblog.

The destruction of an Assyrian palace

In March 2015, ISIS released a video depicting the demolition of one of the most important surviving monuments from the Assyrian empire, the palace of Ashurnasirpal in the ancient city of Nimrud.

As archaeologists, we are all too familiar with destruction. In fact, it is one of the key features of our work. One can only unearth ancient remains, buried long ago under their own debris and those of later times, once. It brings with it an obligation to properly record and make public what is being excavated. The documentation from Ashurnasirpal’s palace is generally disappointing. This is due to the palace mostly having been excavated in the early days of archaeology. Still, the resulting information is invaluable and will continue to allow us to answer new questions about the past.

Ashurnasirpal’s palace was constructed around 865 BCE during a period in which Assyria was slowly becoming the empire that would rule most of the Middle East two centuries later. The palace had probably been emptied by those who conquered the empire in 612 BCE and by those who reoccupied its remains thereafter. (This explains why its rooms were mostly devoid of precious objects.) It is the first known royal palace from the Assyrian Empire (little has survived from the centuries before), and is among the few Assyrian palaces to have been excavated (more or less) in its entirety. Measuring at least two hectares, it must have been one of the largest and most monumental buildings of its time. Though Nimrud itself is 180 times the size of the palace, and still mostly unexplored, the palace’s destruction is yet another blow to the cultural heritage of Iraq. It was without doubt one of the most important sites from that time in the world.

The palace was first excavated from 1847 onwards by Austen Henry Layard, with most finds ending up in the British Museum, which was just being constructed. Contrary to the later royal palaces, it used war scenes sporadically in the decoration of the palace, only using them in the throne-room and in the two reception rooms to its southwest. Hardly any of these reliefs remained in Nimrud, many were taken away during the reign of King Esarhaddon (680-669 BCE), when the palace no longer functioned as a royal residence, to be reused in his new palace. Most reliefs with war scenes were later shipped to the British Museum by Layard.

The British Museum: Room 7 – ‘Paneled Wall Reliefs from the North West Palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud’ by Mujtaba Chohan. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The British Museum: Room 7 – ‘Paneled Wall Reliefs from the North West Palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud’ by Mujtaba Chohan. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons The other monumental rooms of the palace were decorated with apotropaic scenes that depicted different otherworldly creatures. The palace depicted a varied group of such figures, but most walls depicted only a single type. In order to limit the number of reliefs coming their way, the British Museum asked Layard not to send “duplicates”. Layard therefore started giving them away to people visiting his excavations. People continued to visit the site in the decades thereafter to take away reliefs for their own, and as a result, the palace’s reliefs ended up throughout the world. ISIS has now destroyed the last reliefs that remained in Nimrud.

The remaining contents of the palace were also taken away during excavations, with the valuable finds mostly ending up in museums in Iraq and England. Original items still remaining included architectural features, such as floors and drainage, and stone reliefs that had been deemed less valuable by European museums and collectors. The walls blown up by ISIS were mostly reconstructed during the past decades.

A sense of irony pervades the tragedy of the destruction. The Assyrians were renowned destroyers of cultural heritage themselves and masters in letting the world know about their deeds. They were highly skilled in the art of propaganda and used all the media available at the time. Their propaganda was so effective that the Assyrians have had a bad reputation throughout most of history.

ISIS uses propaganda as an art of misdirection. Overall it has been destroying less than it claims, and much more than the ones that have made headlines. To a considerable degree, ISIS was blowing up a reconstructed, excavated, and emptied palace. There should, however, be no doubt about the cultural and scientific value of what had remained. The damage is irreparable and heart breaking. The amount of destroyed heritage is only countered by the daunting potential for more damage. ISIS controls numerous archaeological sites of universal importance. Some of these are known to have been pillaged in order to profit from the illegal sale of antiquities. It is a problem that goes well beyond the area controlled by ISIS and one of which Europe is not always on the good side. Unsurprisingly, ISIS has been less eager to highlight how the art they say to despise is supporting them financially. Since sites can only be dug up once, looting forever robs us of the chance to learn about the past.

Headline image: Portal guardians mark the entrance to what once was the Northwest palace in the ancient city of Calah, which is now known as Nimrud, Iraq. Photo by Staff Sgt. JoAnn Makinano. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post The destruction of an Assyrian palace appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers