Oxford University Press's Blog, page 663

May 25, 2015

Did dark matter kill the dinosaurs?

In 1980, Walter Alvarez and his group at the University of California, Berkeley, discovered a thin layer of clay in the geologic record, which contained an anomalous amount of the rare element iridium. They proposed that the iridium-rich layer was evidence of a massive comet hitting the Earth 66 million years ago, at the time of the extinction of the dinosaurs. The Alvarez group suggested that the global iridium-rich layer formed as fallout from an intense dust cloud raised by the impact event. The cloud of dust covered the Earth, producing darkness and cold, and lead to the extinction of 75% of life on the planet. At first, there was much resistance in the geological community to this idea, but in 1990, the large 100-mile diameter crater produced by the impact was found in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula.

The timing of this impact, together with the fossil record, has led most researchers to conclude that this collision caused the mass extinction of the dinosaurs and many other forms of life. Subsequent studies, determined from the record of more than 150 impact craters on the Earth, found evidence for other mass extinctions in the geologic past, which seem to have happened at the same time as pulses of impacts. These coincidences occurred about once every 30 million years. Why do these extinctions and impacts happen with an underlying cycle? The answer may lie in our position in the Milky Way Galaxy.

Our Galaxy is best understood as an enormous disc. Our Solar System revolves around the circumference of the disc every 250 million years. But the path is not smooth; it’s “wavy”. The Earth passes up or down through the mid-plane of the disc once every 30 million years. The cycle of extinctions and impacts is related to times when the Sun and planets plunge through the crowded disc of our Galaxy. Normally, comets orbit the Sun at the edge of the Solar System, very far from the Earth. But when the Solar System passes through the crowded disc, the combined gravitational pull of visible stars, interstellar clouds, and invisible dark matter, disturbs the comets and sends some of them on alternate paths, sometimes crossing the Earth’s orbit where they can collide with the planet.

Meteor crater by dbking. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Meteor crater by dbking. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr. Recognition of this 30 million year Galactic cycle is the key to understanding why extinctions happen on a regular schedule, but it may also explain other geologic phenomena as well. In further studies, it was found that a number of geological events, including pulses of volcanic eruptions, mountain building, magnetic field reversals, climate and major changes in sea level, show a similar 30 million year cycle. Could this also be related to the way our Solar System travels through the Galaxy?

A possible cause of the geological activity may be interactions of the Earth with dark matter in the Galaxy. Dark matter, which has never been seen, is most likely composed of tiny sub-atomic particles (Weakly Interacting Massive Particles or WIMPS) that reveal their presence solely by their gravitational pull. As the Earth passes through the Galaxy’s disc, it will encounter dense clumps of dark matter. Physicists have argued that the dark matter particles can be captured by the Earth, and will build up in the Earth’s core. If the dark matter density is great enough, the dark matter particles eventually annihilate one another, adding a large amount of internal heat to the Earth that can drive global pulses of geologic activity.

Dark matter is concentrated in the narrow disc of the Galaxy, so geologic activity should show the same 30 million year cycle. Thus, the evidence from the Earth’s geological history supports a picture in which astrophysical phenomena govern the Earth’s geological and biological evolution.

Headline image:The majestic spiral galaxy NGC 4414. Hubble Space Telescope. NASA. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Did dark matter kill the dinosaurs? appeared first on OUPblog.

In the service of peace

May 29th marks the International Day of United Nations Peacekeepers, during which the world pays tribute to those who are serving, those who have served, and those who have lost their lives in the service of peace. Although peacekeeping was not envisaged in the UN Charter, it has become the flagship activity of the Organisation and perhaps the most innovative evolution within the UN collective security system. It is a truly collective effort of UN Member States. Mandated by the Security Council, peacekeeping operations comprise troops, police, and civilians who are under the command and management of the UN. It is dependent upon military and police personnel voluntarily contributed by Member States, who are reimbursed for their activities through the UN budget, met by assessed contributions of all UN members.

Since the first operation was established in 1948, the UN has deployed 69 operations across the world, including to the Middle East, Africa, Europe, South America, and Asia. Peacekeeping has undergone a remarkable evolution, from interpositional ceasefire monitoring missions deployed in response to interstate conflicts, to robust, multidimensional operations deployed to protect civilians in internal wars. This dynamism and flexibility has allowed UN peacekeeping to respond effectively to the changing international security environment, and enabled it to maintain continued relevance as a key instrument for the maintenance of international peace and security.

The development of peacekeeping has been characterised by six key trends:

Deployment of operations into internal, as well as interstate conflict situations; Deployment of operations to respond to humanitarian crisis and gross violations of human rights; Deployment of operations in partnership with other security actors, such as regional organisations; Inclusion of early peacebuilding activities in mission mandates; Inclusion of robust peace enforcement activities in mission mandates; and Inclusion of civilian protection activities in mission mandates.The evolution of UN peacekeeping has not been without challenge and controversy. But the thing that most threatened the credibility of the instrument, and of the Organisation as a whole, was the failure to protect civilians during the 1994 Rwandan genocide and the 1995 Screbenicia massacre. While following these events the international community grappled with the humanitarian intervention concept and the Responsibility to Protect doctrine, from 1999, UN peacekeeping missions began to be mandated to use force to protect civilians under imminent threat of physical violence. The protection of civilians peacekeeping mandate differs from the other concepts in that peacekeeping missions are deployed with the consent of the host State, and therefore such missions don’t represent a coercive use of force against a State.

Since the UN Mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL) was provided with a civilian protection mandate, almost every subsequent peacekeeping operation has been mandated to protect. Currently, 97% of UN peacekeepers serve in missions with protection of civilians mandates, and the Security Council has made clear that civilian protection is the primary function of the UN’s largest missions, currently deployed to the Central African Republic (MINUSCA), Darfur (UNAMID), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) (MONUSCO), Mali (MINUSMA), and South Sudan (UNMISS).

Dia Internacional dos Peacekeepers 29/05/2014, Brasília by Tereza Sobreira, Ministério da Defesa. CC BY 2.0 via ministreiodadefesa Flickr

Dia Internacional dos Peacekeepers 29/05/2014, Brasília by Tereza Sobreira, Ministério da Defesa. CC BY 2.0 via ministreiodadefesa Flickr The protection of civilians by UN peacekeepers raises many challenging issues. Practically, it raises the expectations of local populations, which UN peacekeepers are often unable to meet, including due to a lack of resources and capabilities–most notably force enablers, such as helicopters. The use of force to protect civilians potentially puts peacekeepers at higher risk of injury or fatality, risks that troop contributing countries may not be willing to take. The mandate also carries with it certain political challenges. Missions are often mandated to assist the forces of the host government to execute their civilian protection responsibilities. Where the government forces are a party to the conflict, this may compromise the impartiality of the UN force supporting them. It may also have flow-on effects for the political engagement of the mission with the host government. Conversely, protection of civilians by UN forces against violence perpetrated by host government, or government-backed, forces may result in the withdrawal of host State consent for the mission to remain in the country.

In addition to the practical and political issues, the protection of civilians presents a number of legal challenges. In the pursuit of the protection of civilians, a mission may be mandated to offensively target a particular party to the conflict. In MONUSCO, both the UN’s support for military operations of national Congolese forces, as well as the mission’s Force Intervention Brigade being mandated to ‘neutralise’ specific armed groups in Eastern DRC, reinforced the International Committee of the Red Cross view that the UN military forces had lost the protection of international humanitarian law (IHL). The consequence of which is that the UN military forces in the DRC are now understood as a ‘legitimate target’, having become a ‘party to the conflict’. This is the case for the entire UN military presence, whether Force Intervention Brigade or regular MONUSCO contingent.

Despite the numerous challenges associated with the protection of civilians by UN peacekeeping forces, it remains an important aspect of the peacekeeping tool. Beyond that, it is reflective of a remarkable evolution in the UN collective security system. A system that, over the course of 70 years, has transformed from a regime concerned with classical interstate warfare to one focussed on the security of the human population within States. Unfortunately, the system remains selective and uneven in its application, as the lack of Security Council action on the situation in Syria highlights. Yet, as the international community pays homage to UN peacekeepers past and present, it is appropriate to reflect on the remarkable impact that UN peacekeeping has had on the maintenance of international peace and security.

Featured image: United Nations peacekeepers from Sri Lanka by SMCC Spike Call, US military. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post In the service of peace appeared first on OUPblog.

Remembering Buddhas in Japan

Commemoration of the birthday of Sakyamuni Buddha forms an important but relatively small part of a remarkable emphasis on wide-ranging types of memorials that continue to be observed in modern Japan. However, celebrations in remembrance of death, including for all deceased ancestors who are regarded as Buddhas (hotoke) at the time of their passing marked by ritual burial, generally hold far greater significance than birth anniversaries.

Buddha’s birthday is celebrated in Japan every year on 8 April. With the adoption of the Gregorian calendar in 1873 as part of Meiji-era modernization, the date has become regularized and invariable. The occasion takes place four to six weeks in advance of most other Asian countries that have made memorials for Buddha a national holiday by following a traditional lunar calendar so that the anniversary usually occurs some time in May, according to Western dating, although during a leap year it could vary from late April to early June. The time for the holiday in some countries is linked to the full moon of the Indian month of Vaisakha, and in others it coincides with the full moon of the fourth month of the old Chinese calendar.

In Japan this commemoration is called Busshō-e or Kanbutsu-e, and the ritual held at many temples features a small statue of Buddha in the form of a child as he appeared at birth when, as legend suggests, he took seven steps forward and with his right hand held upward and left hand pointing downward declared, “I alone am honored in heaven and earth.” The statue is sprinkled with scented water or hydrangea tea in a small temporary shrine decorated with flowers. An alternative name is Hana Matsuri, or Floral Festival, in part because the time of year corresponds to the custom of enjoying the blooming of cherry blossoms by gazing at flowers (hanami) in gardens, parks, or other public spaces, including the grounds of some Buddhist temples that make this event part of their ritual cycle.

There are two additional annual holidays dedicated to remembering the Buddha, including Nehan-e on 15 February, when Sakyamui is said to have passed into the Great Final Nirvana (Maha Parinirvana in Sanskrit), and Jodo-e (also known as Rohatsu) on 8 December, which marks the anniversary of the time Buddha initially attained enlightenment after years of ascetic practices and meditation.

‘Daibutsu’ (Great Buddha) – Kamakura, Japan. By Greg Younger. CC-BY-SA-2.0, via Flickr.

‘Daibutsu’ (Great Buddha) – Kamakura, Japan. By Greg Younger. CC-BY-SA-2.0, via Flickr. New Year’s Eve on 31 December is another Buddhist holiday when, as a kind of atonement, the temple bell is rung 108 times to signify the number of human defilements as well as the blessings required to remove them.

Rituals are also held in Japan for nearly all ancestors, who are considered Buddhas regardless of affiliation or actual behavior while living. These Buddhas so designated are provided with funerary rites that include bathing to purify karma, shaving the head to symbolize adhering to precepts, wearing a robe to represent holiness, holding a wake to recall their main life events and values, and the bestowing of a posthumous ordination name to mark their departure to join the realm of Nirvana (nehan) that was first realized by Sakyamuni.

The dead are memorialized on a daily and yearly as well as longer-term basis through various ceremonies performed by family members. These include the veneration of a Buddhist altar (butsudan) installed in a room of the home, regular visits to cemeteries by loved ones, and an extensive range of festivals that are often local to a neighborhood or village.

There are three memorial days that are part of the yearly cycle of remembrances for deceased ancestors. These include Higan-e, which marks both the spring equinox on 21March and the fall equinox on 21 September with outings to graves (haka-mairi) that take place during the week before, and Obon or Urabon-e, which is often called the Ghost Festival as the spirits of the dead are thought to return to the earthly realm so as to be honored with offerings and ceremonies. Originally held on the full moon of the seventh month of the Chinese lunar calendar as a way of highlighting the transition from the Yang or living sector of the year to the Yin or dying division, in Japan the Obon festival is usually regularized as either 15 July or 15 August.

Another form of memorial is the veneration of the medieval founders of the major Buddhist sects, whose death is commemorated annually but is especially highlighted with dedicatory rituals at the time of fifty-year anniversaries. In 2011, for example, there were huge celebrations held in Kyoto for the two main leaders of Pure Land Buddhism: Honen, who originated the school and died 800 years before; and his disciple Shinran, who broke off to establish a different school and died 750 years before. Old-timers were nostalgic for the previous festivity held in 1961.

Featured image credit: Amitābha, by D. Moreno. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Remembering Buddhas in Japan appeared first on OUPblog.

May 24, 2015

How much do you know about Søren Kierkegaard? [quiz]

This May, we’re featuring Søren Kierkegaard as our philosopher of the month. Born in Copenhagen, Denmark, Kierkegaard made his name as one of the first existentialist philosophers of his time. Centuries later, scholars continue to comb through his works, which were produced in such abundance that it is difficult, even now, to come away with a cohesive portrait of the Danish scholar; not to mention the fact that many details of Kierkegaard’s personal life remain unknown. Even so, he remains one of the most influential people of his time, as well as ours. Take our quiz to see how much you know the life and studies of Søren Kierkegaard.

You can learn more about Kierkegaard by following #philosopherotm @OUPPhilosophy.

Image Credit: “Denmark Copenhagen Boats Port” by Witizia. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post How much do you know about Søren Kierkegaard? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

The unfinished work of feminism

These transnational feminist movements are rich and diverse. Their origins and struggles are located in anti-imperialist, anti-colonial, civil rights, anti-war, pro-democracy, indigenous peoples, workers, peasants, youth, disability, and LGBT movements, among others. They seek to transform patriarchal institutions in all their manifestations — from violations of intimate relations to the discriminatory and unequal gender norms of political, economic, social, and cultural institutions.

The work of transnational feminism has challenged gender discrimination and inequalities, but it is clear we still have work to do. There are continuing and increasing gender differentials within and across countries in both the global South and North. Women still have unequal access to fundamental human rights such as food and shelter. Their bodily integrity and sexual and reproductive rights are deeply contested. Women in the global South and North perform the lion’s share of care and social reproduction, are segregated into low-paying occupations, earn less than men for work of equal value, and have unequal control over economic resources. There are still gender gaps in health, education, employment, poverty, entrepreneurship, and decision-making. Violence against women continues in epidemic proportions across the world. As we move solidly into the 21st century the question becomes, how do we do justice to the momentum created by those who came before us? Where do we focus our continued effort?

I believe that the unfinished work of feminism centers around two critical areas: economics and militarism.

Despite five decades of feminist organizing on the economy, the multilateral trading system, gender-responsive budgeting, the care economy, poverty eradication, and the global financial crisis, feminist economics is still viewed as an add-on to mainstream neoliberal economic theory and practice.

Women at farmers rally, Bhopal, India, Nov 2005, by Ekta Parishad. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Women at farmers rally, Bhopal, India, Nov 2005, by Ekta Parishad. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.In The Oxford Handbook of Transnational Feminism, Professor and Head of Social Development at the University of Cape Town, Viviene Taylor argues that currently, “global governance is … about managing … the global market economy to secure the interests of global capital, [where] women’s rights and human security tend to fall off the agenda. While women have been visible in mobilizing and proposing changes … at the global level, it is … at the national and regional levels that systems of inequality and repression remain intact and women’s voices are absent.”

Dismantling these quiet and pervasive structures of inequality in our economics is no small task. However, in the area of militarism, peace building, and post-conflict rebuilding, feminist movements face an even greater challenge.

Maryam Khalid, PhD in gender, orientalism, and war at the University of New South Wales and another contributor to the Handbook, points out that militarism underpins the patriarchal state, the national interest, and the state’s engagement in international relations. Militarism functions to “normalize a view of the world … as marked by war, violence, and aggression.” Increasing numbers of women in the military has not led to a rejection of militarism, but rather they support the masculine military state. Khalid also states that feminist arguments were co-opted to justify the military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq, in the aftermath of 9/11. And Seema Kazi, Fellow at the Centre for Women’s Development Studies, New Delhi, points out that Afghan (and one could add Iraqi) women are far from securing substantive political representation, or achieving economic and social empowerment.

Transnational feminist movements need to take advantage of this pivotal moment of Beijing+20 and the post-2015 agenda to regroup globally, in concert with progressive people of all genders, to challenge existing institutions, to rethink a coherent political-economic paradigm based on peace and security for all, equitable economic distribution and social protection, respect for the limits of the planet’s carrying capacity, and limits on corporate control and commodity speculation. Such a framework would acknowledge the crucial role of women in the formal and care economy and in rural livelihoods, and include comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services.

Featured image: March 8 rally in Dhaka, organized by Jatiyo Nari Shramik Trade Union Kendra (National Women Workers Trade Union Centre) by Soman. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The unfinished work of feminism appeared first on OUPblog.

Bessie Smith: the Empress of the Blues

The filming and recent airing of the HBO film Bessie, which stars Queen Latifah as Bessie Smith, serves as a perfect excuse to look back at the music and life of the woman who was accurately billed as the Empress Of The Blues.

When Bessie Smith made her recording debut in 1923, she was not the first blues singer to record. Ma Rainey’s “Crazy Blues” in 1920 had been such a major hit that it began a blues craze with scores of African-American female singers being documented. While many were quickly forgotten, Ethel Waters and Alberta Hunter were the biggest discoveries before Smith finally appeared on record. She was also not the first jazz singer to record, being preceded by most notably Cliff Edwards (Ukulele Ike) and Marion Harris. However Bessie Smith soon became widely recognized as the most important female blues and jazz singer of the 1920s, and her impact can still be felt nearly a century later.

A listen to some of Bessie Smith’s recordings from 1923 and early 1924 can be a revelation. The recording quality is primitive and much of her accompaniment, even from such pianists as Fletcher Henderson and Clarence Williams, is barely adequate. And yet Smith ignores everything else and sings with power, sincerity and passion that still communicate very well to today’s listeners. It is not just the volume of her voice or her general sassiness and strength. There is an intensity to her interpretations that lets listeners know that she will not stand for any nonsense, that she is a strong independent woman, and that she is a force to be reckoned with.

Bessie Smith Photographed by Carl Van Vechten. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Bessie Smith Photographed by Carl Van Vechten. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Bessie Smith was born in Chattanooga, Tennessee on 15 April 1894. Not only did she grow up poor and black in the South but she lost both of her parents before her tenth birthday. Smith sang in the streets after school, gaining important experience while raising some money for her family. In 1912 when she was 18, she joined the Moses Stock Troupe as a dancer and an occasional singer. She traveled with the company throughout the South and learned about show business and life from their main vocalist Ma Rainey who is considered the first blues singer. Smith switched her emphasis from popular songs to the blues during this period.

Bessie Smith’s singing talents were very obvious as she entered her twenties and worked with other troupes. Her charismatic performances were often hypnotic not only due to the power of her voice but in the directness and truth of the words that she sang. Although the first wave of the blues craze somehow missed her, in 1923 she had her chance. Her very first released recording, Alberta Hunter’s “Downhearted Blues,” was a major hit that eventually sold 800,000 copies. During 1923-33 Smith recorded 160 songs and those often-timeless recordings are Bessie Smith’s musical legacy.

In her recordings, Bessie Smith (as with virtually all of the singers of the era) did not sing directly about racism. Her label (Columbia) would not have released anything that could offend whites in the South. But while many of her recordings dealt with the ups and downs of romances, she also sang about the difficulties of poverty, being treated poorly by men, and even about a few topical events such as floods (“Backwater Blues”). While she did not mince words, one always felt that she would overcome her difficulties. There were also bits of humor in some of the lyrics along with an occasional more light-hearted and jazz-oriented piece. Among the songs that she turned into classics were “’Tain’t Nobody’s Biz-ness If I Do” (which later on was a hit for both Billie Holiday and Jimmy Witherspoon), “Careless Love,” “Backwater Blues,” “Muddy Water,” “Send Me To The ‘Lectric Chair,” “Mean Old Bed Bug Blues,” “Empty Bed Blues,” and “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down And Out.” Both the recording quality and the quality of her sidemen improved by 1925. Louis Armstrong on cornet holds his own with Bessie Smith (and vice versa) on “Careless Love” and “St. Louis Blues,” the superb stride pianist James P. Johnson is perfect on a series of late 1920s recordings, and other favorite players included cornetist Joe Smith and trombonist Charlie Green. Smith also starred in the 1929 short film St. Louis Blues, her only movie appearance.

Unlike many of her contemporaries, Bessie Smith was able to adapt to changing musical and social conditions. She survived both the end of the blues craze and the Depression although the latter and the collapse of the record industry resulted in her only having one record date after 1931. She musically reinvented herself from a blues singer into a bluesy jazz vocalist, a move that unfortunately was not documented on records. In 1935 Bessie sang at the Apollo Theater and appeared in several shows, gearing herself for what would certainly have been a major comeback during the swing era.

It took the tragic car accident of 26 September 1937, which resulted in her death at the age of 43, to stop her — but nothing, not even the passing of 90 years, lessens the impact of the recordings of the Empress of the Blues.

The post Bessie Smith: the Empress of the Blues appeared first on OUPblog.

Cured with sparks: a history of electrotherapy for functional neurological symptoms

Functional disorders are one of the most common reasons for attendance at the neurology clinic. These disorders — at other times and in other places called psychogenic, non-organic, conversion, or hysterical — encompass symptoms such as paralysis, tremor and other abnormal movements, gait disorders, and seizures. The term functional disorder refers to a genuinely experienced symptom which is often disabling and distressing but which relates to abnormal nervous system functioning, rather than a conventional disease process such as epilepsy or multiple sclerosis (Figure 1). Modern treatment involves making a clear diagnosis, educating patients about the disorder, and sometimes offering cognitive behavioural therapy or physiotherapy. But despite growing interest and awareness of these disorders, our treatments are often not effective and many patients have longstanding disability requiring, for example the use of a wheelchair.

Figure 1. Functional leg weakness and functional hand dystonia are some of the common and disabling symptoms of functional disorders seen in modern neurological practice (courtesy of Neuro Symptoms).

Figure 1. Functional leg weakness and functional hand dystonia are some of the common and disabling symptoms of functional disorders seen in modern neurological practice (courtesy of Neuro Symptoms).In recent years, small trials of treatments using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and other forms of electrical stimulation have produced very promising results. TMS, and its cousin TDCS is also being used in conditions like migraine and even as a cognitive enhancer. A commercial market has appeared for these devices. This looks at first sight like a surprising new turn. Yet, little is as new as it looks; electricity has been used medically since the 18th century, and has been used to treat functional disorders — identified, anachronistically, in our review of historical medical case reports, treatises, and textbooks — from the moment devices were capable of delivering a ‘shock’.

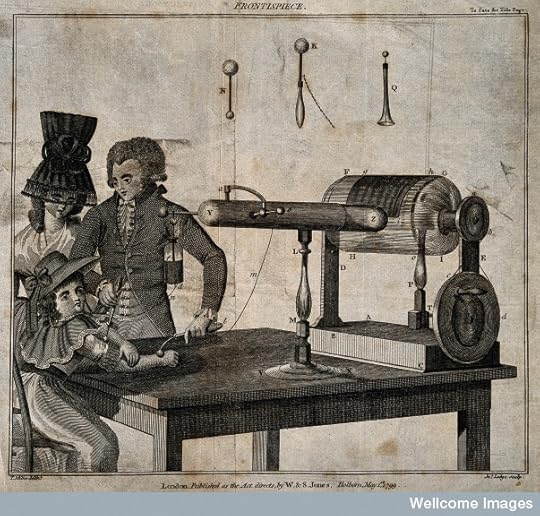

The Leyden Jar (Figure 2, Figure 3) was invented in 1745-6: a portable device for storing and discharging sparks. The earliest descriptions of medical use of the Leyden Jar include reports of sudden cures of weakness and contractures which are highly suggestive of modern functional disorders.

Figure 2. George Adams demonstrates his electrotherapy machine to a woman and her daughter. Line engraving by J. Lodge, 1799, after T. Milne. Wellcome Library, London. CC BY 4.0 via Wellcome Images.

Figure 2. George Adams demonstrates his electrotherapy machine to a woman and her daughter. Line engraving by J. Lodge, 1799, after T. Milne. Wellcome Library, London. CC BY 4.0 via Wellcome Images.Cleric John Wesley, in his 1759 Desideratum: Or Electricity made Plain and Useful by a Lover of Mankind and of Common Sense describes treating a 22-year-old woman with likely dissociative (non-epileptic) seizures (part of the spectrum of functional disorders) using the ‘ethereal fire’ of electricity: ‘On the first Shock her struggling ceased, and she lay still. At the Second her Senses returned. After two or three more, she rose in good Health.’ Similarly Benjamin Franklin, in 1754, successfully treated a 24-year-old woman with multiple ‘hysterical’ symptoms including ‘cramps in different parts of the body’ and ‘general convulsions of the extremities.’

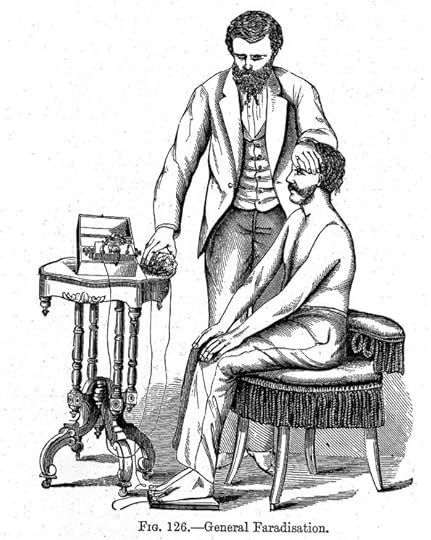

By the mid 19th century many large hospitals had electrical departments with Leyden jars, batteries (developed by Galvani and Volta between 1791 and 1800), and after Faraday’s discovery in 1831, electromagnetic induction machines. Some advocated localized faradization, applying electrical current to the functionally weak body part. Others, believing hysteria to be a constitutional disorder, recommended general faradization (Figure 3) to the body as a whole.

Figure 3. General Faradization, from A treatise on medical electricity, by Julius Althaus. Wellcome Library, London. CC BY 4.0 via Wellcome Images.

Figure 3. General Faradization, from A treatise on medical electricity, by Julius Althaus. Wellcome Library, London. CC BY 4.0 via Wellcome Images.At the turn of the 20th century, Charcot, Babinski, and Freud used static baths, sparks and faradization in the diagnosis and treatment of hysterical symptoms, although Freud later rejected electrotherapy stating (in An Autobiographical Study) that any good results were entirely the result of suggestion.

In contrast, Lewis Yealland, who described extensive use of electrical therapy in shell-shocked soldiers in his 1918 Hysterical Disorders of Warfare, believed that electricity worked purely by suggestion and was no less effective or valuable for this reason. Some of Yealland’s methods now seem cruel: the application of electricity to the tongue in soldiers with hysterical aphonia, so vividly portrayed in Pat Barker’s novel Regeneration and in the film adaptation of the same. Its reputation tainted, reports of electrotherapy diminish after World War I as psychotherapy gained ground as the treatment of choice.

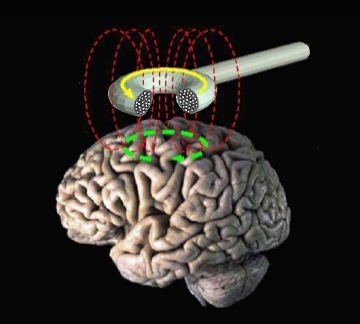

All was then quiet, until the most recent wave of electrical treatments for functional disorders. The first ‘new’ treatment, Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS), developed during the 1970s and a refined form of early cutaneous faradization, has been trialed with some promise in an uncontrolled series of 19 patients with functional movement disorders.

Figrue 4. Transcranial magnetic stimulation by Eric Wassermann, M.D. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Figrue 4. Transcranial magnetic stimulation by Eric Wassermann, M.D. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) (Figure 4) differs from peripheral TENS by delivering a magnetic burst rather than electrical shock and targeting the motor cortex of the brain rather than the motor nerve of an affected limb. But the effect is somehow similar: a shock-like sensation and sudden involuntary movement. The first case report of a patient with functional symptoms improving with TMS was published in 1992, and several subsequent studies have investigated TMS as a treatment, one study describing success in 89% of 70 patients and another 75% of 24 patients.

Authors of these modern studies tend not to reference older electrical treatments. Yet, not only has the treatment been around for a long time, but so have the various ideas about how it works. Modern TMS researchers acknowledge some role for suggestion or placebo but also speculate about changes in the brain, for example suggesting “rTMS may have the ability to restore an appropriate cerebral connectivity by activating a suppressed motor cortex.”

In our article published in Brain we argue that TMS in functional disorders is the latest expression of a repeating cycle of electrical experimentation — first with Leyden Jars, then early batteries, then electromagnetic apparatus — recurring since the mid-18th century. Doctors first attribute improvement, or cure, to powerful biological or even metaphysical effects. With time and experience these explanations are replaced with a view that the treatment works by suggestion, placebo, or by demonstrating the possibility of improvement. This does not rest well with many practitioners, and the treatment is set aside. We suspect that emerging technology such as transcranial direct current stimulation will follow a similar pattern.

Difficulties remain. If these treatments do work through suggestion, modifying expectation or perhaps just demonstrating the potential for recovery is that necessarily a bad thing if they ultimately help the patient? Is there a way we can use the treatments explicitly with patients explaining all of this while keeping the efficacy of the treatment? Discomfort with these questions has in the past discouraged ongoing use of electrical treatments, even when they really seem to have helped. A recently-proposed paradigm of the basis of functional disorder suggest that high order beliefs can influence sensorimotor processing at a neuronal level. Distinctions between what a biological and psychological mechanism are at last starting to break down.

Perhaps we do not need to discard these treatments, which after all have repeatedly been shown to help patients. Maybe by confronting transparently, with patients, the uncertainties regarding mechanism of action we can continue to use these treatments as part of our armoury of techniques to help individuals with functional disorders.

Featured image: Apparatus for applying an electric shock. Showing Leyden jar, Lane’s electrometer and ‘directors’ or conductors. Wellcome Library, London. CC BY 4.0 via Wellcome Images.

The post Cured with sparks: a history of electrotherapy for functional neurological symptoms appeared first on OUPblog.

Being true to your true self

Huckleberry Finn, when faced with the opportunity to turn in the slave Jim, is tortured about what to do. At first he leans in favor of turning him in, because Jim is someone else’s property. And as he was taught in Sunday school, acting as he had been toward Jim was what got people sent to hell. But he can’t stop thinking about Jim’s companionship on the river, and how Jim had been nothing but kind to him all along, a real source of comfort and friendship. So Huck, with trembling hands, finally declares, “All right, then, I’ll GO to hell,” and decides not to turn Jim in. In doing so, Huck rejects his upbringing, societal norms, conscience, and eternal happiness (so he thinks). He clearly thinks he is doing the wrong thing. We, by contrast, know he is not.

Now consider JoJo, who is the son of a cruel dictator on an isolated island. JoJo adored his father, and because he was exposed only to his father’s values, when JoJo grew up he naturally adopted his father’s values as his own. When he came into power himself, he beat peasants on a whim, just like daddy. (This is drawn from a case by Susan Wolf.) JoJo clearly thinks he is doing the right thing. We, by contrast, know he is not.

Both Huck and JoJo do what they do out of moral ignorance. Because of their upbringing, they have each been deprived of some moral knowledge: in Huck’s case, the knowledge that slavery is wrong (and that slaves aren’t property); in JoJo’s case, that beating peasants on a whim is wrong. So what bearing might that moral deprivation and ignorance have on their moral responsibility for doing what they do?

Philosophers who work on the nature of responsibility very often insist that ignorance of the moral status of one’s action is sufficient to excuse — or at least mitigate — one from responsibility. If you didn’t know that what you were doing was wrong, after all, how could it be appropriate to hold you responsible for not refraining from doing it? This view is thought to hold symmetrically across negative and positive cases: not only does ignorance excuse (or mitigate) one from blame for bad actions, it also excuses (or mitigates) one from praise for good actions to the same extent.

Reflection on a droplet, by Takashi Hososhima. CC by SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Reflection on a droplet, by Takashi Hososhima. CC by SA 2.0 via Flickr.This is not, however, how ordinary people view the matter. My colleague David Faraci and I have investigated the matter several times, and each time we get the same results. When asked about JoJo, people overwhelmingly think that his moral ignorance does mitigate his blameworthiness, albeit only a little bit (versus someone like him without that background). However, when people are asked about a case like Huck’s, they respond that his moral ignorance doesn’t mitigate his praiseworthiness at all; indeed, in some studies, we have found that people think his moral ignorance actually makes him more praiseworthy for what he did than a morally undeprived counterpart.

This is a very interesting asymmetry in people’s views of the role of moral deprivation in moral responsibility. It looks like it mitigates attributions of responsibility only in negative cases, when agents do something wrong. But why would that be?

Inspired by the excellent work of Joshua Knobe, George Newman, Paul Bloom, and Julian De Freitas, we have explored the issue further by asking whether people thought that the actions in question expressed the agent’s true self, the person he really is deep down inside. And did they ever! It turns out people’s beliefs about whether the action expresses the agent’s true self actually determine their answers about whether his responsibility was mitigated or not. In other words, the more people think the action expresses who the agent really is, the more they think he’s responsible for it.

Obviously, then, people tend to think that what JoJo did didn’t express who he was as much as what Huck did, despite their similar morally deprived upbringings. And a leading explanation for the different assessments is that we tend to think people’s true selves are fundamentally good. Consequently, when we do what’s bad, various factors (like a morally deprived upbringing) excuse or mitigate to the extent that they are thought to obscure the expression of our true (good) selves. But when we do something good, well, that’s just our good self shining through, regardless of our upbringing, and so our action is attributable to us for purposes of responsibility.

“If you didn’t know that what you were doing was wrong, after all, how could it be appropriate to hold you responsible for not refraining from doing it?”

The story about the good true self gains support from additional asymmetries. The most interesting ones involve people with conflicting beliefs and feelings. For example, when presented with the case of a Christian who believes homosexuality is wrong but who has homosexual feelings against which he struggles, most liberals think the feelings are more expressive of his true self, whereas conservatives tend to think not. When presented with a secular person who believes homosexuality is fine but who nevertheless struggles against feelings of disgust toward homosexuals, liberals tend to think his beliefs are more expressive of his true self, whereas conservatives tend to think it’s really his feelings that reveal who he is deep down inside. (This is from a study by Newman, Knobe, and Bloom.) So it looks as if one’s antecedent moral views determine one’s views of the true self as well as what actions reflect it.

This is really interesting and, for a cynic like me, downright puzzling. What makes it even more puzzling is that this result is found in only some asymmetries involving positive and negative agential appraisal, and it’s unclear why it’s not found across the board. Of course, it’s also unclear why moral deprivation and ignorance should be thought to block the good true self’s expression only in negative cases. And there may be other more general reasons for why we mitigate blame but not praise, having to do with the harsh treatment that typically follows verdicts of blame. And finally, what “ordinary people” think about responsibility might just be irrelevant to more considered theorizing about it. Nevertheless, these are results that need to be grappled with by theorists of responsibility in one way or another.

The post Being true to your true self appeared first on OUPblog.

May 23, 2015

16 words from the 1960s

As the television show Mad Men recently reached its conclusion, we thought it might be fun to reflect on the contributions to language during the turbulent decade of the 1960s. This legacy is not surprising, given the huge shifts in culture that took place during this point in time, including the Civil Rights movement, the apex of the space race, the environmental movement, the sexual revolution, and—obviously—the rise of advertising and media. With this in mind, we picked 16 words from the 1960s that illuminate this historical moment.

1. sexploit

Given the advent of the sexual revolution in the 1960s, the appearance of the blend sexploit (sex + exploit), an ‘instance of engaging in sexual activity of a casual or illicit nature’, is not all that surprising. Related words include sexploitation and sexcapade.

2. trendsetter

A trendsetter is something that leads the way in fashion or ideas. Today, trendsetter is more likely to refer to a person, but the word may also refer to a thing, such as a magazine, or a particular style of clothing.

3. A-OK

Although ‘OK’ in various forms had been around for more than a century, the form of ‘A-OK’ only really came into vogue in the early 1960s, a result of its repeated use during the transmissions of the Mercury 7 NASA mission. The phrase is a shortened version of ‘all systems OK’.

4. grok

We have science fiction writer Robert Heinlein to thank for the word grok—which means to ‘understand (something) intuitively or by empathy’—which first appeared in his 1961 novel Stranger in a Strange Land. (The word grok also appears in Season 6 of Mad Men.)

5. paparazzo

The word paparazzo comes from Federico Fellini’s 1960 film La Dolce Vita, which features a freelance society photographer named Paparazzo. The word paparazzo soon came to mean ‘a freelance photographer who pursues celebrities to get photographs of them.’ Today, one usually hears the plural ‘paparazzi’ rather than the singular paparazzo.

Bait-and-switch refers to the generally illegal action of advertising goods that seem to be a bargain, with the intention of substituting either inferior or less expensive goods. While the term began its life in the advertising world, it soon found its way into general usage, eventually referring to the deceitful substitution of one thing for another.

7. miniseries

A development in television during the 1960s was the miniseries, a television drama that aired in a number of episodes rather than in a single broadcast or across several ‘seasons.’

8. phat

Meaning ‘excellent,’ the word phat emerged from African-American slang and is probably a respelling of the word fat, rather than an acronym referring to aspects of a woman’s anatomy, as some have suggested.

9. scam

Of unknown origin, the word scam refers to a ‘dishonest scheme’ or a ‘fraud’, and is also used as a verb in the sense of perpetrating such an action.

10. skateboard

An offshoot of the surfing culture in southern California during the 1940s and 1950s, the practice of skateboarding only really took off in the 1960s, when skateboard manufacturers began promoting and distributing their wares more widely. Wakeboarding was similarly popularized a few years later.

11. glitch

A slang term popularized by astronauts and NASA engineers in the early 1960s, glitch referred to a ‘sudden surge of current’ that would cause equipment to temporarily malfunction. Despite its surge in popularity in the 1960s, glitch was first used by radio operators in the 1940s. Today, the word refers more broadly to any snag, irregularity, or setback, especially one in video games or software.

12. braless

Marking the importance of the women’s liberation movement in the 1960s, the adjective braless emerged, referring to a woman not wearing a bra. Contrary to popular belief, there are no records of bras being burned during protests, although some women did throw them away.

13. biohazard

The ecological movement of the 1960s led to major changes in how people considered their effect on the environment. One word that emerged to express some of these issues was biohazard, referring to a ‘risk to human health or the environment arising from biological work, especially with microorganisms’.

14. teenybopper

The rise of rock and roll in the 1960s was paralleled by the rise of the teenybopper, referring to a young teenager (typically a girl) who follows the latest trends in pop music and fashion.

15. surf ‘n’ turf

Dating from the early 1960s, the delectable ‘surf ‘n’ turf’ (or ‘surf and turf’) on restaurant menus refers to a dish combining seafood and meat, especially one that includes lobster tail and steak.

16. head-trip

Among other things, a head-trip refers to a hallucinatory experience or altered state produced by consuming drugs. The term has come to refer more broadly to an experience likened to a drug hallucination, or a strange or profound experience.

A version of this blog post first appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Image Credit: “Mad Men Smoke” by amira_a. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post 16 words from the 1960s appeared first on OUPblog.

Philosophie sans frontières

“East is East and West is West, and ne’er the twain shall meet.”

Well, no. Kipling got it wrong.

The East and the West have been meeting for a long time. For most of the last few hundred years, the traffic has been mainly one way. The West has had a major impact on the East. India felt the full force of British imperialism with the British East India Company and the British Raj. Japan fell in love with German culture — especially military culture — after the Meiji restoration. The French colonization of Vietnam drew it inexorably into the Vietnam War.

In the last 40 years, however, a lot of the trade has been going the other way. The post-war developments in Japanese electronics and motorbikes came to dominate the West. Many global IT developments — not to mention call-centers — are now firmly based in India. And it is impossible for Westerners to miss all the garments now bearing the label “Made in China.”

Economy moves at the speed of money. Philosophy moves at the speed of ideas, which is somewhat slower. But the story is similar. In the last 150 years, Western philosophy has made a major impact on the East. The British Raj brought German Idealism — or at least the British take on it — to 19th and early 20th century Indian philosophy. The Japanese Kyoto school absorbed influences from Bergson, James, and — above all — Heidegger. And the influence of Marx on Chinese thinkers hardly needs emphasis.

The influence in the reverse direction is still nascent, but it is now gathering pace. As little as 30 years ago, there was hardly a course on an Eastern philosophical tradition in any Western philosophy department. In fact, it was common to hear Western philosophers claim that the Eastern traditions were merely religion, mysticism, or simply oracular pronouncements. That view was held by philosophers who had never taken the trouble to engage with any of the texts. Had they read them, with care, they would have realized that the philosophy behind them is clear, once one has learned to see beyond the cultural and stylistic differences.

Now, however, many good Western philosophy departments teach at least one course on some Eastern philosophical traditions (at least in the English-speaking world). Good translations of Asian texts are being made by Western philosophers with the appropriate linguistic skills (in the past, translation was firmly in the domain of philologists and scholars of religion). Articles which draw on Eastern ideas are starting to appear in Western philosophy journals. PhD theses are being written comparing Confucius and Aristotle, Buddhist ethics and Stoic ethics, Nyāya and contemporary metaphysical categories. Introductory text books are appearing.

A seated wooden Bodhisattva statue, Jin dynasty (1115–1234), Mountain at Shanghai Museum. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

A seated wooden Bodhisattva statue, Jin dynasty (1115–1234), Mountain at Shanghai Museum. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.There is still a long way to go until the institution of Western philosophy understands that it is just that — Western philosophy. But at least the movement is under way, though it will certainly take time to overcome the current marginalization of the other half.

What will happen to Western philosophy when full realization sets in? Of course, if we knew what philosophy was going to emerge, it would already have done so. And predictions in this area are worth little. However, I will venture a theory.

We are in the situation that arises when different cultures meet. This has happened before in philosophy. It happened when Greek philosophy met the ideas of the Jewish break-away sect based on the life and death of Yeshua Bar-Yosef. The result was the remarkable development of Christian philosophy. It happened when the ideas of Indian Buddhism came to infuse Chinese thought in the early years of the Common Era. The result was the remarkably distinctive forms of Chinese Buddhisms, such as Chan (Zen). It happened when the new scientific culture which developed in Europe around the Scientific Revolution impacted late Medieval Philosophy, to give us the wealth of Modern Philosophy. I predict that we will witness a similar progressive moment in the present context.

Why do these meetings of culture deliver such progress? It is hard to answer this question without talking about what progress in philosophy amounts to. I can only gesture at an answer here. Progress in philosophy is not like progress in science — whatever that is: as philosophers of science know, this is not an easy question either. One way to see this is to note that philosophers still read Plato, Augustine, Hume. No scientist, qua scientist, reads Newton, Darwin, or even Einstein. Nor is this because the philosophers are simply doing the history of philosophy. They read because the texts contain ideas from which one can still learn.

Cynics might say that what this shows is that there is no progress in philosophy. I demur. Progress in philosophy certainly arises when we become aware of new problems and new arguments. But old problems of importance rarely go away. Yet even here there is still progress in the depth of our understanding. We see new ways to articulate ideas, new aspects of problems, new possible solutions to them.

Now, there are at least two reasons why the impact of a new culture promotes such progress. First, it is a truism that the best way to understand your native tongue is to learn another; and the best way to understand your culture is to become familiar with a radically different one. The contrast throws into prominence things so obvious as to have been invisible. So it is in philosophy. And when these assumptions become visible, they can be scrutinized in the cold hard light of day, to expose any shortcomings.

Secondly, there is genuine innovation in philosophy, but it does not arise ex nihilo. Philosophers draw on their philosophical background for ideas, problems, solutions. The more they have to draw on, the greater the scope for creation and innovation. In the same way, when good Western chefs learn about Eastern cuisine (ingredients, preparations, dishes), they do not simply reproduce them — though of course they can do this, and they do. The most creative draw on the Eastern and Western traditions is to produce entirely new dishes. Call this “fusion cuisine” if you like, but the name is not a great one, since what emerges is not simply merging two cuisines, but creating genuinely novel fare. So it is with philosophy. An understanding of Eastern traditions, when added to an understanding of Western traditions will allow creative philosophers to come up with philosophical ideas, questions, problems, which we cannot, as yet, even imagine.

Over the last couple of decades, it has been my privilege — and that of a small band of other Western-trained philosophers — to help bring the Asian philosophical traditions to the awareness of Western philosophers. For all of us, I think it is true to say, our own philosophical thinking has been enriched by an understanding of Eastern philosophical traditions. If we can enrich the thinking of our Western philosophical colleagues in the same way, our time will have been well spent.

Featured image: “Golden Buddha Statue of Gold Buddhism Religion” by Epsos.de. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Philosophie sans frontières appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers