Oxford University Press's Blog, page 667

May 16, 2015

Cold feet in literature

The act of writing has a long history of being associated with romantic reluctance. The figure of speech ‘cold feet’ made its debut in print in 1896 in Stephen Crane’s Maggie as a riff on the idea of writing as a kind of forward movement. Crane’s novel about the life of a New York slum girl called Maggie, begins with a decision to run; Maggie’s brother Jimmy thinks better of his resolution: “dese micks can’t make me run”, and sets off. Jimmy is a stand-in for the writer (who might be Crane or anyone) who has no appetite for his subject, and perseveres just for the sake of it. Later on, Crane imagines Jimmy “going into a sort of trance of observation” behind the reins of his horse-drawn truck, as if he were mentally describing the events of the story. In revising the book for republication, Crane strengthened this link between writerly and fictional progression by inserting the phrase ‘cold feet’ into the scene where Maggie’s lover Pete suddenly becomes fascinated by “a woman of brilliance and audacity” called Nell. Ironically, Pete reveals his ‘cold feet’ through his hot pursuit of someone new, whereas Crane is stuck with Maggie: his title commits him to maintaining an interest he often quite obviously doesn’t feel.

Or, this is the conceit. It rests on the illusion that Crane has no choice but to tell Maggie’s story: that he writes in a “trance of observation.” This idea of passive writing is one of the signals that Maggie is designed to be read as a Naturalist novel – that is, a novel that’s so comprehensive in describing the granular minutiae of a story that the writer can seem like a recording device, with no will of his own. In an anonymous review of Crane’s London Impressions (1897), the author of Maggie’s spin on the Naturalist method is compared to the efforts of a “locust in a grain elevator attempting to empty the silo by carrying off one grain at a time.” The motif of reluctance in Maggie could perhaps suggest that Crane saw his method in the way his reviewer saw it – as a kind of locustic Sisyphian labour – but whether or not this recognition is designed to cast doubt on its appeal and value (as it does in the review) is hard to know. Writerly ‘cold feet’ might be an effect we enjoy and credit with sophistication.

John Singer Sargent, ‘The Archers’. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

John Singer Sargent, ‘The Archers’. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.In the first half of the twentieth century, the Naturalist investment in telling a story step by step was offset by an investment in formal experimentation. The new avant-garde impulse to challenge convention by doing without plot in writing novels or ignoring metrical rules in writing poems, pulled attention away from what was going on on the level of a text’s content towards issues of expression. But within this preoccupation with form there was also a capacity for boredom and reluctance. In 1940, one of Modernist literature’s most acute early critics, Randall Jarrell, compared the experimental poems of the 1930s to a biological “species that [has] carried evolutionary tendencies so far past the point of maximum utility that they actually became destructive to them …” This ‘evolutionary’ process of overcomplication finds its modern-day equivalent in postmodernism. In David Foster Wallace’s Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way (1989), the sense that the only way to write fiction is to engage in “gratuitous cleverness, jazzing around, self-indulgence, no-handsism” afflicts the budding writer Mark Nechtr with a case of ‘cold artistic feet.’ Nechtr’s cynicism doesn’t put him off, however; he continues to write in dribs and drabs, just as he goes ahead with his marriage to a fellow writer called D. L. whose own knowing postmodernist ‘no-handsism’ turns his stomach. He doesn’t allow himself to translate reluctance into retreat.

Both the granular style of writing that characterises Naturalism and the preoccupation with form that characterises twentieth-century literature are likely to inspire reluctance, and the literature of the first half of the twentieth century is particularly likely to register these two kinds of reluctance at once. John Rodker’s Adolphe, 1920 (1929) is simultaneously conscious of itself as an overdetailed story and as a piece of metafiction. When Rodker’s protagonist, Dick, is cornered by an ex-girlfriend who wants him to explain his change of attitude towards her, Rodker draws our attention to his “difficulty” in “begin[ning] to talk” by reminding us of his cold feet; he writes: “How cold his feet were …” and “his feet were cold …” The act of writing itself can also be reluctant. In Jeremy Prynne’s A Gold Ring Called Reluctance (1968), the impetus to write is a kind of death wish; he opens: “As you drag your feet or simply being/tired, the ground is suddenly interesting;/not as metaphysic but the grave maybe …” The blank verse – made up of a series of five metrical ‘feet’, or two-syllable components – drags itself along in the absence of rhyme or much of an iambic pulse. The effect of this ‘dragging’ metre is reminiscent of mortality, but it’s ultimately just an ‘idea of the end’ that occupies the poem. What we get instead of a meditation on death is a meditation on writerly hesitancy that sometimes whimsically calls to mind death. And even this hesitancy isn’t terminal. The poem comes to a halt as soon as it directly states its reluctance to continue, with the lines: “The ground on which we pass,/Moving our feet, less excited by travel.”, but the echo between the idea of a focal gravitation towards the ‘ground’ and the opening impression that “the ground is suddenly interesting” creates a circuit, or a “gold ring” – a marriage – while the pun on “pass” invites us to find movement in cessation. We could say that, like Crane, Wallace, and Rodker, Prynne links the condition of ‘cold feet’ with perseverance, though the poem’s continuation relies on our willingness to project type into a blank space, like footprints in the snow.

The post Cold feet in literature appeared first on OUPblog.

May 15, 2015

Using Pop Up Archive for oral history transcription

After completing my first transcription process using Dragon NaturallySpeaking, I was asked to transcribe an interview using Pop Up Archive, an online platform for storing, transcribing, and searching audio content developed by the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). They explain the process in three steps:

1. You add any audio file.

2. We tag, index, and transcribe it automatically.

3. Your sound, in one place, searchable to the second.

I was assigned an interview from the University of Wisconsin collection of interviews regarding the Sterling Hall Bombing of 1970. This was a really interesting interview with a former undergraduate who was working at Sterling Hall on the night of the bombing. The uploading process is relatively simple, fitting well with the overall aesthetic of the website. You can either drag and drop files into the upload box or select one at a time. I chose to upload one file at a time, since I had four excerpts to work with. I later learned that if you choose to upload multiple files at once, they will merge into one large file. This, in my case, wouldn’t have been useful, as I wanted to test how long it took each excerpt to be transcribed.

The upload process was quick and painless, immediately giving me the option to add metadata, including the title, format, collection, images, and any tags. I decided to add a couple of tags (Sterling Hall, Sterling Hall Bombing, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Student protests, 1960s, 1970s) and a picture of Sterling Hall after the bombing. Without any prompting, Pop Up Archive began the transcription.

Here is the screen after the file was uploaded (Figure 1). The picture shows up as a little square next to the title. I find the screen to be a little too sparse. I understand that this website really focuses on being simplistic and easy to use, but I find the information to be oddly placed on the page.

The first excerpt was 4 minutes and 20 seconds long. I uploaded it at 3:20, and when I left my office for the day at 4:30, it was still transcribing. I received an email at 5:20 alerting me that the transcription was done. Whether this was exactly when the transcription finished, I’m not sure, but that seemed like an awfully long time for a short excerpt. Unfortunately, there isn’t a progress bar or anything along those lines to let you see how far along your transcription is.

“Figure 1, Sterling Hall Excerpt.” Photo by Samantha Snyder.

“Figure 1, Sterling Hall Excerpt.” Photo by Samantha Snyder.You can listen to the audio while the transcription is running in the background, so if this is an interview you haven’t heard, it’s a fun way to entertain yourself while waiting. I played around with the website to try and figure out what I could do while the file was being transcribed. I found that you can still edit the metadata while it is being transcribed and that there are additional metadata fields hidden away under a ‘more fields’ link, making it possible to add all kinds of information to the file.

When I got back to work the next day, I had the transcription ready and waiting for me to edit. I was incredibly impressed with the results. It did a nice job with the transcription, though I was able to spot some errors. The interviewee was soft-spoken and tended to run his words together slightly, so I was expecting there to be some editing that needed to be done. Besides the transcript, Pop Up Archive automatically adds suggestions for related topics that link to other interviews from other users. These are different than the user-created tags, because you cannot add more related topics, only delete suggestions that are not pertinent to your interview.

The transcription process had an easy learning curve and I felt like I was able to work efficiently. While you are editing the transcription, you can play the audio right along with it. You can stop and start the audio by pressing the Tab key and start the line over by using the command Shift and Tab. The one strange thing is that it splits the audio into separate lines, seemingly without any reasoning behind it, and there is no way to delete any of these line breaks, which sometimes were just a period or one word. You can add and delete words, but it will not recognize added words and move on to the next line if that is where it originally splits.

The software can differentiate between voices, but sometimes it recognizes too many voices. There were two interviewers and one interviewee in each piece, but the software recognized eight different voices in one excerpt. Fortunately, it’s an easy fix; you just assign speakers to the lines and it will fill down until it recognizes the next voice that you assigned. In the picture above, the letters “RW” are the initials of the interviewee.

I really enjoyed editing the transcription of the first excerpt and moved on to the second excerpt, which was a short 45 seconds. This took hardly any time at all. My third excerpt was seventeen minutes long, and I started the upload at 2:15 and received an alert email at 2:45. The fact that this took so much less time than the first excerpt makes me think that the platform may recognize voices after multiple files are uploaded with the same interviewer and interviewee.

“Pop Up Archive Transcription.” Photo by Samantha Snyder.

“Pop Up Archive Transcription.” Photo by Samantha Snyder.Though this excerpt was transcribed much faster, it had a larger amount of errors than the first and second excerpts. It also had lines that featured both the interviewer and interviewee speaking. Since there is no way to add new lines, I could only assign one speaker to the already created line. I had to be careful with this excerpt, since it was so long and had the bleed-over from interviewer to interviewee, there was a lot of room for mistakes. The picture above is of a portion of the transcription prior to editing. This section does not have any major mistakes, just some wording and grammar issues. To finish, I went through each excerpt to ensure the metadata was consistent, finished final edits of the transcripts, and confirmed they were all titled in a uniform fashion.

Since I was using this platform for research purposes, I did some searching to try and find exactly what software Pop Up Archive was using to do the transcribing and tagging. However, I had no such luck. This doesn’t worry me, but having a bit more information on how the transcription truly works would be helpful. I am slightly wary of putting faith in an online platform to transcribe and store all of your data, but they do give the option to download the audio and transcriptions which solves that, if you have adequate space to store the digital files. There is a possibility that the data could be lost or corrupt, but the same could happen when using servers and networks.

While there are things that could be improved, such as the ability to add and delete lines, a progress bar on the transcription process, and occasional grammar mistakes, this is a great program for oral history transcription. Transcribing these excerpts, which totaled about 23 minutes, took only about 20 hours to complete from start to finish, though most of this time was spent cutting the clips and uploading them to the service. With Dragon NaturallySpeaking, it took at least twice as long. I would highly recommend giving this platform a chance, though I cannot speak to the free transcription. I completed this process using the premium transcription.

Disclaimer: Pop Up Archive generously provided a free trial of their premium service for us to test out.

If you’ve tried transcription software, or other creative oral history methods, share your results with us in the comments below or on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or Google+.

Image Credit: “Plaque on the south side of Sterling Hall on the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus” by JabberWock. CC BY SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Using Pop Up Archive for oral history transcription appeared first on OUPblog.

The most exciting advances in intensive and acute cardiac care

Things move fast at the acute end of medicine — and nowhere is this more apparent than in the field of intensive and acute cardiovascular care. This important field (some say the development of the coronary care unit was one of the most important advances in cardiology) has been somewhat neglected at the expense of super-subspecialisation in cardiology. But times are changing. The increasing complexity of patients requiring acute cardiac care has demanded that we no longer ignore cardiac intensive care, including developing training and education programmes, transforming structural and organisational norms and focusing our attention on more research in these most challenging and high stakes areas. The argument that any cardiologist can assess and manage critically ill cardiac patients has long been lost, as the technical and clinical advances in intensive care have moved in parallel with, but separate from, those in cardiology. The coronary care unit (once a place to monitor and treat patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction) has largely been renamed the cardiac (intensive) care unit, reflecting the breadth and complexity of cardiovascular and associated diseases now presenting to the acute cardiac care cardiologist.

In areas that have remained seemingly static for years, we now have the potential to transform outcomes for our patients. The swine flu pandemic has led to a global resurgence of interest in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in adults, with emerging indications in cardiomyopathy, cardiogenic shock, and even as a salvage following cardiac arrest. Systematic application of research to the development of novel pharmacological vasoactive agents — so often disappointing in the past — provides us with opportunities to support circulation whilst minimising harm to other organs. But the greatest areas of potential development are surely where cutting edge cardiology meets the critically ill, thanks to true multidisciplinary collaboration. Examples include the potential for our electrophysiological colleagues to optimise the management of arrhythmia in the critically ill, and for our interventional colleagues and surgeons to develop smaller and safer percutaneous mechanical support, intervening in increasingly minimal access ways.

Clinicians in Intensive Care Unit by Calleamanecer. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Clinicians in Intensive Care Unit by Calleamanecer. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.This is best exemplified by the development of transcatheter valve interventions, which represent a true paradigm shift in the management of patients with severe valve disease. Patients previously deemed inoperable may now be offered life changing/saving therapies, and increasingly neglected techniques such as balloon aortic valvuloplasty are now being revisited in the most critically ill, with potential for definitive later intervention. At the other end of the technology spectrum, the appropriate and timely collaboration with teams providing comfort and support to critically ill patients and their loved ones is vital to delivering high quality intensive care. The demands provided by this are different from, but equally important to, those where we develop and implement novel therapies and techniques designed to save life. The intensive care cardiologist should always be mindful that high technology care must be mixed with compassion. The realities of doing so sometimes require great skill, and the importance of such a holistic approach, even in this most challenging of areas, is increasingly and explicitly recognised by specialists in the field.

Arguably the greatest collaboration, however, comes with the use of echocardiography in intensive care — with its potential to direct and change the management of the majority of patients. This technique was previously the sole domain of the cardiologist, but is now used throughout the patient pathway in acute cardiac care — with emerging evidence of its positive impact on assessment and management of critically ill patients, ranging from pre-hospital medicine, to the most complex and high-technology cardiac intensive care unit patient. This powerful bedside diagnostic and physiological monitoring technique has transformed cardiac intensive care, is increasingly recommended as standard of care in the acute setting, and is an example of effective multidisciplinary collaboration to improve care in the most critically ill.

This is truly an exciting time in the field of intensive and acute cardiac care. As a junior doctor training in cardiology, and then intensive care, I was always told this subspecialty was not important, and urged to focus my training elsewhere. I am glad I did not.

Featured image: Heartbeat by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post The most exciting advances in intensive and acute cardiac care appeared first on OUPblog.

All gone to look for America: Mad Men‘s treatment of nostalgia

The popularity of Mad Men has been variously attributed to its highly stylized look, its explication of antiquated gender and racial norms, and nostalgia for a time when drinking and smoking were not sequestered to designated zones but instead celebrated in the workplace as necessary ingredients for a proper professional life. But much of Mad Men’s lasting appeal lay in its complicated relationship with nostalgia. Hollywood fare typically adheres to historian Michael Kammen’s declaration that “nostalgia, with its wistful memories, is essentially history without guilt.” To view Mad Men, though, is to be inundated with uncomfortable truths from America’s past that, too often, linger in the present. There’s no shortage of guilt. The show’s most powerful analytical lens magnifies the construction of our present world—a world increasingly feared as absurd, and no longer tenable or sustainable.

One of Mad Men’s central themes reveals the tensions dominating daily life in postwar modernity, when the nuclear family was fetishized as the source of all social and emotional gratification, marginalizing former sites of community in favor of, as historian Elaine Tyler May describes, the safe haven of the home in the midst of the threatening chaos of the Cold War world. This impossible burden placed on the family meant that it could never really measure up to all of the hopes, dreams, and demands that were placed on it, making it a favorite target for advertisers playing on anxieties that one’s family was not meeting the idealized image put forth in popular television programs like Leave it to Beaver and Ozzie and Harriet.

The postwar family quickly became a commodified community, and admen, like Mad Men’s Don Draper, amassed cultural power through their mastery of language and symbols employed to produce powerful ads aimed at a yearning to achieve the idyllic community and home that was the stuff of endless dreams that could never quite be reached—but maybe the purchase of just one more product would finally mean fulfillment. (Or — as Theodore White wrote in his series of books on The Making of the President beginning in 1960 that detailed how politicians were increasingly marketed and sold to the public like any other product — maybe the election of just one more president.)

Mad Men suggests to contemporary viewers the disturbing origins of the simulacra of life in a hyper-consumer culture of surfaces, where characters playact a script written and re-written by generations of Don Drapers. One of the most talked about shows in the series is “The Wheel,” the final episode of the first season that finally delves directly into the quandary that by then has been laid bare. “The wheel” of the title refers, most concretely, to the carousel of a Kodak slide projector—so familiar to baby boomers—that is the focus of an advertising campaign created by Draper. He sells the slide carousel as a “time machine” that invites “nostalgia,” which he translates from Greek (incorrectly) as “the pain from an old wound.” The carousel “takes us to a place where we ache to go,” says Draper, “back home again, to a place where we know we’re loved.” But, of course, as Thomas Wolfe had already stated in 1940, “You Can’t Go Home Again.” Worse, as Mad Men continually makes plain, that “home,” whether in our individual or collective memories, never actually existed—Don Draper created it. “What you call love was invented by guys like me,” he reminds us, “to sell nylons.”

The cast of Mad Men (2011). Image courtesy of AMC.

The cast of Mad Men (2011). Image courtesy of AMC.The “Kodak moments” of life arranged in the slide carousel represent, in those days before Facebook and Instagram, idealized images plucked from lives that are anything but ideal. They are snapshots of those “instants” that most mimic life as it appears in mediated forms in Life magazine, movies, television, and, of course, advertising. Context is erased and forgotten, providing the illusion that all of life once felt like that perfect moment captured on film, and if we could just travel back to that place and time we might once again be happy and loved. But, as Svetlana Boym has stated, “The past for the restorative nostalgic is a value for the present—the past is not a duration but a perfect snapshot.”

Even as Draper is selling the “time machine” ad campaign to Kodak executives, and desperately trying to convince himself that the life projected is the life he’s living, viewers can see that the idyllic family images on the slides are moments from his own family life that, although it appears perfect in pictures, we know to be anything but. Despite appearances that he’s living the postwar suburban American dream, we know that his relationship with his Grace Kelly-esque wife is crumbling, he drinks too much, and he spends too little time with his children. The Kodak moments permit the construction of a life that, in reality, has never existed, and foster the yearning for community in an imagined past free from the complexities, compromises, and disappointments that have always accompanied living. As Paul Simon once sang in his song “Kodachrome” about the popular slides that filled carousels: “They give us those nice bright colors / They give us the greens of summer / Makes you think all the world’s a sunny day.”

The message is clear: our present nostalgia is for a world that exists only in media, advertising, and our imaginations. “There is no big lie. There is no system,” Draper warns a group of sixties counterculture activists, in a statement that captures the failed dreams of a generation. “The universe is indifferent.” That “universe,” in the context of Mad Men, is postwar corporate capitalism. As Simon concluded, “Everything looks worse in black and white.”

Faced with the inadequacy of the family to fulfill all that we seek in community, Americans retreat to their familiar posture of individualism. For Don Draper, this means leaving his family and immersing himself evermore deeply in the masculinity of postwar corporate capitalism. Draper and America increasingly measured manliness in terms of conquering consumer culture, women, and what Playboy founder Hugh Hefner liked to call “the great indoors.” Draper’s linguistic prowess (combined with his dreamy looks) makes him the master of this world, at once perfectly creating and embodying its signifiers. But beneath his surface of masculine perfection remains the reality of a deeply troubled and unhappy life. The impossible burden placed on individuals meant that they could never really measure up to all of the hopes, dreams, and demands that were placed on them.

In Mad Men’s final season, the erstwhile Sterling Cooper & Partners, the ad agency at its heart, is taken over by a monster corporation, and the world increasingly looks uncomfortably like our own. Don flees this indifferent universe. Heading west in his silver Cadillac, he is visited by the ghost of Bert Cooper, who cites Jack Kerouac’s On the Road: “Whither goest thou, America, in thy shiny car in the night?” Soon after this encounter, Don gives the car away to a small town kid who, like Draper in a previous life, dreams of making it big. But what meaning does a Cadillac hold in an America where, we learn, CEOs now travel in private Lear jets, leaving the rest of us ever further behind? “We’re flawed because we want so much more,” Don Draper once said of Americans, “We’re ruined, because we get these things and wish for what we had.” Many of us who are drawn to Mad Men feel this in our bones, and yearn for an America that might liberate us from our present state of disillusionment, delivering us, finally, to a mythical place of meaning and fulfillment.

Featured image courtesy of AMC.

The post All gone to look for America: Mad Men‘s treatment of nostalgia appeared first on OUPblog.

For the love of trees

I used to climb trees when I was young (and I still, on occasion, do). As a boy in Iraq I had a favoured loquat tree, with branches that bore leathery, serrated leaves, shiny on the upper surface, and densely matted with fine hairs underneath. It seemed so big, though I now reflect it was probably rather small. I would haul myself up and over the lowest branch, making whatever use of the twists and folds of the trunk as provided purchase to my small feet. Standing atop the lowest branch provided a keen sense of achievement, and revealed new vistas of adventure further up. Penetrating the upper layers where branches were more plentiful was easier, but was accompanied by the excitement of increasing exposure. A buzz of excitement would envelop me, as did the leaves around me, on reaching the upper canopy. Comfortably ensconced within the sweep of a branch, I would remain perched for a good many minutes, on some occasions hours, surveying the passage of time below. People passed, oblivious to my gaze, though they interested me little. Far more exciting were spiders and ants that wandered across the trunk and leaves. Insects came and went. Birds fluttered in, cleverly exploiting holes in the netting that clearly failed to protect the fruits. They did not mind me much if I remained still and quiet. I began to create new worlds in that tree. On moving to Britain, still a fairly young boy, I did the same, though this time it was a tall weeping willow that became my second home. Resting my ear against the tree revealed strange sounds which to this day perplex me.

I am far from unique in my love of climbing trees. Most boys and girls do the same, and a good many adults trace their love of trees from their childhood ramblings within them. We have a strong sense of connection with trees which is often difficult to articulate. People readily hug or pat trees, but with no clear sense of purpose – it just feels good and right to do so. We display an affection and tenderness for trees that we might show for a friend or family member. Our societies also nurture deep seated reverence for trees and woodlands, which are often symbolic of our origins. Ancient woodlands captivate us, perhaps for the sense of continuity that they provide to our past. Trees are woven into the fabric of our folkloric literature.

While we cherish our trees and woodlands we also, paradoxically, exploit them for their timber, and clear them entirely to make way for fields, houses and roads. Industrial exploitation of woodlands for fuel, timber, and agricultural land has a long history. The Romans discovered to their cost that woodland clearance leads to soil loss and the siltation of harbours. In the centuries following the Norman conquests in Britain, forests became sources of wealth, and new forest laws secured exclusive access to those with power.

Sequoia forest. Public domain via Pixabay.

Sequoia forest. Public domain via Pixabay.Trees became commodities, and the common folk were increasingly excluded from woodlands. As Europeans spread west into North and South America, forests with which they had no historical connection or familiarity were viewed as wasteland. On the American frontiers forests were imbued with a sense of malevolence, to be civilised and Christianised by settlement, cultivation and development. Tropical forests have suffered the same fate in recent decades, as our insatiable demand for raw materials and food turns ‘wasteland’ into productive land.

All the while many voices have spoken up in defence of forests. Plato in his dialogue Critias, as far back as 360 BC, bemoaned the loss of animals, the impairment of water supplies, and loss of soils that followed deforestation. In 1691 the botanist John Ray argued for the recognition of existential rights of all forms of life. In the late 19th century George Perkins Marsh railed against the ‘profligate waste’ in the destruction of North American forests. These early lone voices have now swelled to many millions across the world, each of whom celebrate the intrinsic biological and cultural values of woodlands, and are concerned about the destructive impact that human society is wreaking on forests. One particularly loud voice, and notable tree climber, must be Julia Butterfly Hill. In December 1997 she climbed to the top of a tall coastal redwood and stayed there for more than two years. She did so to protest reckless exploitation of forests, to protect the trees themselves from loggers. Her love of trees successfully stopped the continued destruction of the pristine ancient redwood forests.

Tomorrow, May 16th, is apparently, ‘Love a Tree Day’. We might express our love by patting or hugging a tree, or even climbing into its embrace. But how well do we know the objects of our affection? To love them better, and indeed to more effectively protect them, we should at least know who it is we profess to love. Our fascination of trees and woodlands is greatly enriched by understanding their identities, ecologies, and histories. Therefore, on May 16, rather than simply hugging a nearby tree, let’s also use the day to discover, explore, and learn about the trees and woodlands in our area, so that we might better care for them, and indeed love them all the more.

Featured image credit: Tree trunk. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post For the love of trees appeared first on OUPblog.

May 14, 2015

What puts veterans at risk for homelessness?

There has been an ongoing battle to end homelessness in the United States, particularly among veterans. Over the past three decades, considerable research has been conducted to identify risk factors for veteran homelessness, and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has funded much of that research.

In 2009, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) announced its commitment to end veteran homelessness in five years. As we near the end of that five years, it’s important to reflect on what we have learned and what we now know about veteran homelessness. We have recently conducted a systematic review of the literature and summarized our findings from 31 studies on veteran homelessness in a recently published article, “Risk Factors for Homelessness Among US Veterans.” Our questions, a few of which are included below, continue to be of critical importance to policymakers, local communities, and health providers seeking to assist those returning from war.

Are veterans at greater risk for homelessness than other adults?

The short answer is yes. The long answer is also yes, but that veterans from certain service eras are particularly at risk compared to other non-veteran adults. Female veterans are particularly at risk compared to other female non-veterans.

The military is an All-Volunteer Force where people enlist to be in the military. However, before 1965, people did not “volunteer” but were drafted into the military. We found that veterans who served in the early years of the All-Volunteer Force in the late 60s and early 70s were particularly at risk for homelessness, and it has been theorized that this was because many men volunteered to serve during this time to escape poor economic conditions or lack of family support.

“The battle, sir is not to the strong alone; it is to the vigilant, the active, the brave.”

—Patrick Henry

It is also notable that women veterans seem to be at particularly higher risk for homelessness than women non-veterans. As the number of women in our military climbs, VA women specialty clinics have been formed to try to address this issue. But generally, veterans as a whole are at slightly greater risk for homelessness. The most recent 2014 Annual Homeless Assessment Report estimates that 11% of homeless adults in the United States are veterans, while only 7% of Americans are veterans.

What are the major risk factors for veteran homelessness?

Besides poverty, the strongest and most consistent risk factors for veteran homelessness seem to be substance abuse and mental illness. This is not surprising, as this trio of poverty-substance abuse-mental illness also represents the major risk factors for homelessness among non-veterans. This trio is also associated with many other bad outcomes, such as stress, hospitalization, criminal justice involvement, etc. Research has shown there are strong associations between poverty-substance abuse-mental illness, and they often do not occur in isolation but together. And together, they may dramatically increase a veteran’s risk for homelessness.

One can easily understand how these factors could increase risk for homelessness. Money is needed to find and keep housing, so those in poverty struggle to earn money to afford housing. Mental illness, particularly psychotic disorders, can lead to difficulties with navigating everyday life, social interactions, and even understanding reality. Therefore, people with severe mental illness may have difficulties with finding housing, making payments for housing, and providing upkeep for their homes to keep them habitable. People with substance abuse problems also experience these same difficulties, and their housing problems can be exacerbated by spending money on substance use. For some veterans, their substance abuse began when they were in the military and continued after they left. There is some research, though, to suggest that recent homeless veterans who served in Iraq and Afghanistan have fewer substance abuse problems than homeless veterans from previous service eras such as Vietnam.

How are these issues viewed from a veteran’s perspective?

Kevin Payne, an Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) veteran in our lab, shared his thoughts with us:

As a veteran coming from an environment surrounded by poverty, substance abuse, and mental illness this topic is highly relatable. Many service members seek out the military as a way to escape the rigors of everyday life and family. Once sworn in, your problems become obsolete to your comrades and, in many instances, to yourself as well. For many, the military is a major detox of poverty, substance abuse, psychosocial issues, and homelessness. The military provides housing, medical and dental services, meals and other necessities, along with instruction and structure.

In a way, the military offers many of the tangibles that social services and healthcare institutions provide. Many soldiers are able to use the military to grow, learn independence, and carry out responsibilities in their everyday life. But unfortunately, some fall short of that. Some return home to the same environments they wanted to leave in the first place. Some have mental illness or indulge in substance abuse making their lives even harder, leading to problems like crime, unemployment, and of course, homelessness. Some have difficulty obtaining help, and at times, they may feel turning to the streets is their only option. Consistent with Dr. Tsai’s research, I think that veteran outreach, providing resources, and assuring multiple resources are in place for veterans prior to their leaving the military are keys to preventing veteran homelessness. We can only hope to continue to spread awareness and try to bring an end to homelessness among my fellow veterans.

What can we draw from research on veteran homelessness?

The battle against veteran homelessness continues to be one waged by many local communities, health providers, policymakers, and others across the country. The research suggests there are particular socioeconomic and mental health factors to target in prevention efforts. But more novel and innovative strategies to prevent and end homelessness are needed. Ending homelessness is an ideal that we should continue to pursue, particularly for those who have served us and our country.

Image Credit: “Veterans Day Wreath Laying 2013″ by Presidio of Monterey. CC BY NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post What puts veterans at risk for homelessness? appeared first on OUPblog.

Four steps to singing like a winner

Singing like a winner is what every emerging professional aspires to do. Yet there are so many hardships and obstacles; so much competition and heartache; so many bills to pay that more people sing like whiners than winners. To be fair, the pressures on singers in the 21st century are great. Research shows that only 6% of university-trained singers will gain management five to seven years after graduation. How will you forge a successful career against all odds? The answer is to sing like a winner every time you sing.

Here are four steps that may help you sing like a winner right now:

Know your strengths and milk them.

If you can rock high C’s night or day, with a cold or after a break up, make sure your repertoire has lots of high C’s. When you perform, show the audience, panel, or judges that you know you have those C’s in the bag. Savor them. Linger over them. Milk them for all you’ve got. The same goes with any special super power you have as a singer. Can you sing long phrases on one breath? Milk it. Can you sing runs faster than a speeding bullet? Milk it. Find your super power as a singer and show it off every time you sing.

Insert your personality for authenticity.

I’m not talking about Rosina’s personality; I’m not talking about Leporello’s personality; I’m talking about your personality. Figure out what you are known for and then, as the song says, let it go. Don’t hold back on being yourself. Are you known for acting silly? Goofy? Are you serious as a heart attack? Is your quirk being very picky or prickly? Are you like Droopy or any one of the seven dwarfs? Find ways to build the quality that is unique to you into your performance. It’s not like you are hiding it anyway. But wouldn’t it be great to really exaggerate that trait essentially turning your annoyingly adorable personality quirk into a strength on stage? Just ask your friends how they would describe you. Get two or three opinions until you find the trait that fits and then make it work for you every time you sing.

Female singer on stage. © IPGGutenbergUKLtd via iStock.

Female singer on stage. © IPGGutenbergUKLtd via iStock.Approach every singing opportunity like a winner.

According to Gurumayi Chidvilasananda, spiritual teacher and guide: “Whether you feel you are winning or losing ultimately depends on the way you approach things and the way you let them approach you.” Yes, I know, you lost your passport, got your luggage stolen, you have cramps, and the soprano ahead of you is wearing your same dress. You have a choice: you can either approach this singing opportunity like a loser and let it all get to you; or you can approach it like a winner with good humor and optimism and let it all roll off your back. This career is really and truly hard. Developing a strategy to approach it and let it approach you like a winner is one of your super powers. Use it every time you sing.

Have fun in the moment.

Let go of all possible rewards just for the time the music is playing. Make it your goal to go into that magical, musical, best-of-all-possible world where you are already a king or queen as soon as you hear the opening ambrosial sounds of your intro. Enjoy that magic. There is no judge or jury because it’s your world and you are too busy having a blast painting the scenery with your singing, or creating a moment of true love or heartbreak to worry about anything else. You are playing. You are having the time of your life. Don’t worry, the music will end and you can go back to your real life drama in three to five minutes; but for now, have a ball, and everyone listening to you will have a ball too.

Of course singing like a winner is within everyone’s power. You’d be amazed at how many singers don’t realize all the power they actually have. The world needs that special sound that only comes from your strength, personality, unique approach, and ability to have fun. Now that’s power. Sing like a winner every time you sing and see what happens.

The post Four steps to singing like a winner appeared first on OUPblog.

May 10, 2015

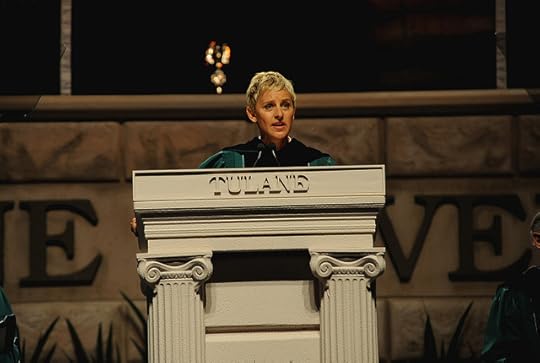

How to write a great graduation speech

It’s graduation time at many of the nation’s schools and colleges. The commencement ceremony is a great exhalation for all involved and an annual rite of passage celebrating academic achievements. Commencement ceremonies typically feature a visiting dignitary who offers a few thousand inspirational words.

Over the years, I’ve heard more of these speeches than I care to admit and have made my own checklist of suggestions for speakers. For those of you giving commencement speeches or listening to them, here’s my advice:

1. Be just funny enough

The best speakers are knowingly wry and a bit self-deprecating. Here’s Michael Bloomberg, opening his 2014 Harvard Commencement address, with a typical opening:

I’m excited to be here, not only to address the distinguished graduates and alumni at Harvard University’s 363rd commencement but to stand in the exact spot where Oprah stood last year. OMG.

Compare that with President Kennedy, speaking at Yale in 1962, who invoked the Cambridge-New Haven rivalry to tease his hosts a bit:

Let me begin by expressing my appreciation for the very deep honor that you have conferred upon me. As General de Gaulle occasionally acknowledges America to be the daughter of Europe, so I am pleased to come to Yale, the daughter of Harvard. It might be said now that I have the best of both worlds, a Harvard education and a Yale degree.

Then again, presidents can get away with that sort of thing, but most speakers can’t.

2. Be like Shakespeare

“Graduation 2009″ by Tulane Public Relations. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.

“Graduation 2009″ by Tulane Public Relations. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr. Keep the diversity of your audience in mind. You are speaking to students, but the students are not all the same. There are honor students—summa, magna, and cum laude–as well as those who are still sweating out a few grades. You are also speaking to families and to the university faculty. Shakespeare had that same problem—needing to address those in the Lord’s room, the galleries, and the ground pit. He solved it by repeating himself, expressing ideas in both the Latinate phrases and in plain Anglo-Saxon, as when he combined unfamiliar words like incarnadine with familiar ones like red.

Here is Ellen DeGeneres, giving the commencement speech at Tulane in 2009. Talking about the honorary degree she is receiving, she plays with the languages of her audience:

I thought that you had to be a famous alumnus – alumini – aluminum – alumis – you had to graduate from this school.

She speaks to both the people who are not quite sure of the singular of alumni, and to those who are.

3. Think about bite-sized ideas

Your speech is likely to come up as a topic of discussion later in the day at lunch or dinner, if only to deflect attention from other topics like job interviews and loan repayment. What will the different audiences take away from your speech? What will students say when Grandma asks, “So what did you think of the speaker?”

As you develop your theme, try to have a memorable, quotable line for each segment of your audience—the grads, the families, and the faculty. And remember that your audience can’t rewind your speech or mark it with a yellow highlighter, so be sure to illustrate your easily-recognizable theme with smaller, easily-digestable examples.

Neil de Grasse Tyson did this in his 2012 speech at Western New England University. His theme was the prevalence of fuzzy thinking and the desire for choices rather than fresh thought. He touched on the theme repeatedly, with examples ranging from a lunch date with his sister, to a spelling bee, to a job interview, throwing in an allusion to Plato (for the faculty) and ending up with the point that thinking is painful hard work. Journalist Sharyn Alfonsi also did it in her commencement address to the journalism school at Ole Miss in 2013, as she talked about work and perseverance, and illustrated those values through her own career’s challenges, including job applications, tough days, and bad bosses. Choose examples that everyone can relate to and can talk about over lunch.

4. Avoid the “Real World” and other clichés

Be careful when using clichés in your speech. Tempting as it may be to tell the graduates that they are about to enter the “Real World” (where you have thrived), you should avoid that. Savvy students will see you as out of touch, since many of them have been working all along and are often managing any number of real life issues.

You may want to avoid talking about the value of their education as well. They know the value. That’s why they went to college. (It’s the cost they are worried about.)

And don’t tell them they are going to die. What if someone had just died on campus? Steve Jobs could get away with talking about death at Stanford in 2005 (“And yet death is the destination we all share”), but he had cheated death at the time.

On a rare occasion, though, you can subvert the clichés. Jon Stewart, speaking at William and Mary in 2004, presents the so-called “Real World” this way:

Let’s talk about the “Real World” for a moment… I don’t really know to put this, so I’ll be blunt: we broke it… But here’s the good news: you fix this thing, you’re the next greatest generation, people.

“David Foster Wallace” by Steve Rhodes. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

“David Foster Wallace” by Steve Rhodes. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr. David Foster Wallace took the liberal arts cliché by the horns in his 2005 speech at Kenyon College, telling the audience:

So let’s talk about the single most pervasive cliché in the commencement speech genre, which is that a liberal arts education is not so much about filling you up with knowledge as it is about “teaching you how to think.”

Wallace then used that to suggest a new perspective—that education is about choosing what to think about.

And screenwriter Joss Whedon, of Buffy the Vampire Slayer fame, tricked up the death theme at Wesleyan in 2013, opening with a reference to the horror genre and the live-life-to-the-fullest cliché:

What I’d like to say to all of you is that you are all going to die.

5. Keep it short

Unless you are a national leader using the speech to announce a major policy, you won’t need more than 20 minutes, tops. Twelve minutes would be even better. The average speaker reads about 120 words a minute, so that’s about 1,400-2,400 words or 9-15 pages (double spaced, 16 point font). Sitting in the sun, the students, families, and faculty will all appreciate brevity.

Here is Poet Laureate Billy Collins speaking at Colorado College in 2008:

I am going to speak for 13 minutes. I think you deserve to know that this will be a finite experience. It is well-known in the world of public speaking that there is no pleasure you can give an audience that compares to the pleasure they get when it is over, so you can look forward to experiencing that pleasure 13 minutes from now.

One of the most memorable commencement addresses at my institution was given by a retired speech professor, Leon Mulling. It was just one-minute long, consisted entirely of verbs (Go. Do. Create. Laugh. Love. Live.) and received thunderous applause.

6. Above all: relax and enjoy yourself

To do well as a commencement speaker, you need gentle humor, Shakespearean universal accessibility, something memorable for each audience, both a theme and relatable examples, an awareness of clichés, and brevity. And if it makes you nervous to think that college graduates, families, faculty, and even YouTube will be scoring your speech, remember—there’ll be another commencement speaker up on the stage next year.

Image Credit: “Graduation Day” by Md saad andalib. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How to write a great graduation speech appeared first on OUPblog.

Neverending nightmares: who has the power in international policy?

Late last year, North Korea grabbed headlines after government-sponsored hackers infiltrated Sony and exposed the private correspondence of its executives. The more significant news that many may have missed, however, was the symbolic and long overdue UN resolution condemning the crimes against humanity North Korean committed against its own people.

In November 2014, the General Assembly voted overwhelmingly to condemn North Korea for its human rights abuses and to refer it to the International Criminal Court (ICC) for prosecution. The resolution was based on a UN report published earlier in the year that detailed widespread killings, starvation, and torture on a scale “without parallel in the contemporary world.” Yet the General Assembly lacks the power to refer North Korea to the ICC, and the ICC lacks the authority to prosecute non-member states. To make matters worse, the Security Council is not likely to refer North Korea for ICC prosecution due to explicit opposition from China and Russia.

North Korea is certainly not alone. Syria, Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Central African Republic, Burma, Rwanda, Afghanistan, and Nigeria have all been mired in unspeakable violence at different times over the last six decades. It’s puzzling that in a world where we cure diseases that were considered beyond reach even ten years ago, send people to the moon, and launch space crafts into the dark corners of the universe, we cannot figure out the what kinds of institutions we need to prevent such countries from committing oppression and unspeakable harm on a large scale.

The statues of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il on Mansu Hill in Pyongyang (april 2012). By J.A. de Roo. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The statues of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il on Mansu Hill in Pyongyang (april 2012). By J.A. de Roo. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. While the institutional technology to constrain the worst in the human impulses raises very different challenges than the technology to cure disease or explore outer space, experiments in democracy and the rule of law in different parts of the world have taught us a few things about how to prevent the concentration of power into the hands of a few — and how to insure a minimum of guarantees internal to states that protect individual rights.

However reliable those guarantees, for a variety of reasons they remain out of reach for large swaths of the globe. It is time to give the ICC more prosecutorial power, and create new international institutions whose main aim is to prevent massive human rights abuses and to step in when states are unable or unwilling to fulfill their most basic responsibility to their own citizens, namely the protection of physical safety and basic freedom.

Proposals such as these raise immediate questions about unjustified interference with state sovereignty, or evoke dark forebodings of a global leviathan. The first kind of skepticism is based on the assumptions that states should be the ultimate arbiter of justice on their territory and with respect to their citizens, and that they can competently thwart both internal and external threats.

This assumption has been with us since the rise of the modern state, yet it has never been warranted. Whatever power and resources enable states to protect their citizens also enables states to turn against them. Accepting the view that states are the final authority of right and wrong is tantamount to accepting, without question, whatever they choose to do to their citizens, however shocking to the moral conscience of mankind. This outdated defense of sovereign independence at all costs leaves hundreds of millions of people vulnerable to the efficacious killing machines of criminal states.

The other worry, that institutions such as the ICC could turn into a global leviathan, is worth heeding. Still, institutions such as the ICC and others whose task would be to protect the most basic level of physical security, such as a stronger policing and enforcement agency, are unlikely to turn into a global government, with the power to create zoning laws, welfare reform, or the right to holidays with pay. Not if those of us living in different countries, with the power to authorize, define and constrain the powers of such institutions, can minimize the dangers of institutional overreach. Our knowledge of how to build good institutions is limited, but doing nothing and hoping for the best is no longer acceptable in the face of such challenges.

With the recognition that states are imperfect, incomplete political forms should come a willingness to support institutions with the power to keep states in check and make sure they do not fall below the most minimal demands of their responsibilities to their citizens. It is the only hope for ending the nightmares of countless people living under the most brutal regimes in the world, whose odds in the survival game has depended on brute luck alone. It is time to change the odds.

Featured image: UN General Assembly bldg flags by Yerpo. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Neverending nightmares: who has the power in international policy? appeared first on OUPblog.

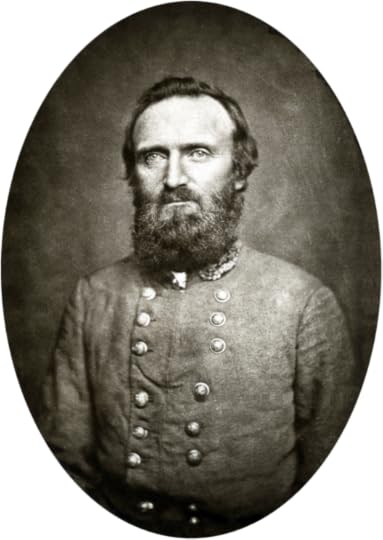

Stonewall Jackson’s “Pleuro-Pneumonia”

On this day in 1863, General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, one of the wiliest military commanders this country ever produced, died eight days after being shot by his own men. He had lost a massive amount of blood before having his left arm amputated by Dr. Hunter Holmes McGuire, arguably the most celebrated Civil War surgeon of either side. Initially, Jackson seemed to be recovering satisfactorily, but then deteriorated progressively with recurrent right-sided chest pain, difficulty breathing, and mounting fatigue. McGuire maintained that post-operative “pleuro-pneumonia” was the disorder that carried him off, a diagnosis that has since been the most widely accepted explanation for Jackson’s death.

Dr. McGuire was a careful observer with vast experience in managing such cases. However, the summary of Jackson’s fatal illness, which he published in the Richmond Medical Journal in 1866, makes no mention of the two cardinal features of fulminant pneumonia: fever and productive cough. If that account is accurate, and Jackson exhibited neither fever nor productive cough during his fatal illness, then recurrent pulmonary emboli, rather than pneumonia, would be the post-operative complication most likely responsible for his death.

General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. Photo by Nathaniel Routzahn, Valentine Richmond History Center, Cook Collection. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. Photo by Nathaniel Routzahn, Valentine Richmond History Center, Cook Collection. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Pulmonary emboli are blood clots generally originating in the legs, which dislodge and migrate via the veins to the lungs, where they come to rest in the pulmonary arteries. They create “difficulty breathing” of the kind Jackson experienced by destroying areas of the lung fed by the arteries in which they lodge and by inhibiting oxygenation of blood by a variety of other mechanisms. Jackson likely sustained his first pulmonary embolus at 10 a.m. on Sunday, 3 May 1863, approximately eight hours after having had his arm amputated, when he first complained of pain in his right chest accentuated by breathing. His risk of developing such blood clots would have been extremely high then. Aside from major trauma, which has been shown to render the blood hypercoagulable, age, need for surgery or blood transfusion, the presence of fractures and spinal cord injuries each has been shown to be an important risk factor for deep vein thrombosis in trauma patients. Jackson had several of these. He was also bedridden post-operatively, yet another important risk factor. During strict bed rest, blood tends to stagnate and clot in leg veins, because the pumping action of muscles responsible for propelling blood through these veins is markedly reduced during immobilization.

By the sixth post-operative day, Jackson was no longer having chest pain. However, his breathing was extremely labored, and he complained of total exhaustion. If he was having recurrent pulmonary emboli, as McGuire’s summary of his case suggests, he had by then reached a tipping point with respect to his pulmonary function. As the number of emboli increased, damage accumulated to such an extent that Jackson’s lungs were no longer able to oxygenate his blood sufficiently to sustain life, and his spirit “passed from earth to the God who gave it.”

Featured Image: The death of Stonewall Jackson by Currier & Ives. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Stonewall Jackson’s “Pleuro-Pneumonia” appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers