Oxford University Press's Blog, page 668

May 10, 2015

What can we learn from Buddhist moral psychology?

Buddhist moral psychology represents a distinctive contribution to contemporary moral discourses. Most Western ethicists neglect to problematize perception at all, and few suggest that ethical engagement begins with perception. But this is a central idea in Buddhist moral theory. Human perception is always perception-as. We see someone as a friend or as an enemy; as a stranger or as an acquaintance. We see objects as desirable or as repulsive. We see ourselves as helpers or as competitors, and our cognitive and action sets follow in train.

We can explain or express this in the Buddhist language of sparsa (contact), vedanā (hedonic tone), samjña (ascertainment), chanda (action selection) and cetanā (intention). Every perceptual episode, while it might begin with sensory contact, has some hedonic tone. We experience the object with which we have contact on a continuum from pleasurable to distasteful. Perception involves ascertainment–the representation of the object perceived as of a kind. This ascertainment and hedonic tone lead us to ready action appropriate to the object and its affective valence, and as we do so, we form an intention to act, perhaps before we even become aware that we do so. Perception is always part of a contact-cognition-action cycle in which there is no bare awareness of an object disjoint from our interests or affect.

It is hard to avoid the conclusion that perception itself is morally charged. If I see women as tools, or Latinos as fools, the damage is done. That perception involves the formation of intentions that are morally problematic on their face, and that lead to harms of all kinds. Perceiving in that way makes me a morally reduced person. If, on the other hand, I perceive people as opportunities to cooperate, or to provide benefit, I perceive in a way that involves the construction of morally salutary intentions, good on their face, and productive of human goods. For this reason, much Buddhist ethical discourse eschews the articulation of duties, rules or virtues, and aims at the transformation of our mode of perceptual engagement with the world. Moral cultivation, on this view, is the cultivation of a way of seeing, not in the first a instance a way of acting.

Buddha head at Ayuthaya, by McKay Savage, CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Buddha head at Ayuthaya, by McKay Savage, CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr. The importance of moral perception is well-illustrated by the phenomenon of implicit bias. Since Greenawald et al. (1998) a raft of evidence has demonstrated both the omnipresence and the pernicious effects of implicit bias. Implicit bias—the subliminal association of negative traits with members of groups that are the victims of bias and positive traits with dominant goups—is evident in the implicit bias association task, in experiments asking professionals to evaluate resumés with stereotypical names, in salary decisions regarding candidates of opposite genders, in tasks asking participants to identify objects carried by individuals in rapid presentation, in medical decisionmaking, etc. It is far too widespread, and far too robust a finding to be dismissed. While it is possible to reduce the effect of implicit bias through training, that training must be regular, and must be regularly repeated if the effects are to be significant or lasting, and the most effective methods in reducing implicit bias are affective, not cognitive. Changing people’s explicit beliefs or attitudes, and even making them aware of their own implicit bias has no real effect. Only training that involves changing the immediate affective valence of the perception of others has any lasting effect.

Implicit bias demonstrates that the roots of virtue and vice, or of good and evil lie not in what we do, but in how we see. The fact that in the moment we have no control over our implicit bias may excuse us from culpability of that bias in the moment, but it does not excuse us from responsibility to transform ourselves so as to eliminate that bias. Involuntariness, that is, may excuse the act, but it does not absolve us of moral blameworthiness. The same goes, mutatis mutandis, for morally salutary perceptual sets. We have an obligation, once we recognize our implicit biases, to remediate them. We cannot reflectively endorse being the kind of person who perceives the world in this way.

Implicit bias is only the tip of the moral iceberg of our perceptual lives. The very processes that are salient when we investigate racial or gender bias in these disturbing studies are ubiquitous in our psychology. It is not only racial stereotyping that is problematic; the representation of Maseratis as desirable, or of insect protein as undesirable may be just as morally charged, and just as deeply implicated in perceptual processes. And the powerful effects not merely of implicit social pressures at work in the cases of racial stereotyping, but also the deliberate efforts of advertisers, demagogues, preachers and moral philosophers to distort our perception must be morally scrutinized, for just as implicit bias demonstrably distorts our explicit reasoning and judgments in invidious ways, the panoply of subliminal processes to which it is kin have the same effect across the domains in which agency is manifest.

A Buddhist moral psychology shows us just how and why our moral lives begin with perception, and Buddhist meditative practices provide an avenue to eradicate the vices of perception and to encourage more virtuous ways of seeing the world.

Featured image credit: Prayer Wheel, by Brandon. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post What can we learn from Buddhist moral psychology? appeared first on OUPblog.

May 9, 2015

The evolution of the word ‘evolution’

It is curious that, although the modern theory of evolution has its source in Charles Darwin’s great book On the Origin of Species (1859), the word evolution does not appear in the original text at all. In fact, Darwin seems deliberately to have avoided using the word evolution, preferring to refer to the process of biological change as ‘transmutation’. Some of the reasons for this, and for continuing confusion about the word evolution in the succeeding century and a half, can be unpacked from the word’s entry in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED).

Evolution before DarwinThe word evolution first arrived in English (and in several other European languages) from an influential treatise on military tactics and drill, written in Greek by the second-century writer Aelian (Aelianus Tacticus). In translations of his work, the Latin word evolutio and its offspring, the French word évolution, were used to refer to a military manoeuvre or change of formation, and hence the earliest known English example of evolution traced by the OED comes from a translation of Aelian, published in 1616. As well as being applied in this military context to the present day, it is also still used with reference to movements of various kinds, especially in dance or gymnastics, often with a sense of twisting or turning.

In classical Latin, though, evolutio had first denoted the unrolling of a scroll, and by the early 17th century, the English word evolution was often applied to ‘the process of unrolling, opening out, or revealing’. It is this aspect of its application which may have been behind Darwin’s reluctance to use the term. Despite its association with ‘development’, which might have seemed apt enough, he would not have wanted to associate his theory with the notion that the history of life was the simple chronological unrolling of a predetermined creative plan. Nor would he have wanted to promote the similar concept of embryonic development, which saw the growth of an organism as a kind of unfolding or opening out of structures already present in miniature in the earliest embryo (the ‘preformation’ theory of the 18th century). The use of the word evolution in such a way, radically opposed to Darwin’s theory, appears in the writings of his uncle, Erasmus Darwin, in Zoonomia (1801).

The world…might have been gradually produced from very small beginnings…rather than by a sudden evolution of the whole by the Almighty fiat.

Use of ‘evolution’ elsewhereCharles Darwin’s caution, however, was futile—the word was ahead of him. By the end of the 18th century, evolution had become established as a general term for a process of development, especially when this involved a gradual change (‘evolutionary’ rather than ‘revolutionary’) from a simpler to a more complex state. The notion of the transformation of species had become respectable in academic circles during the early 19th century, and the word evolution was readily in hand when the geologist Charles Lyell was writing Principles of Geology (Second Edition, 1832):

The testacea of the ocean existed first, until some of them by gradual evolution, were improved into those inhabiting the land.

By the 1850s, astronomers were also using the word to denote the process of change in the physical universe, and it would inevitably become central to the reception of Darwin’s work.

‘Evolution’ in Darwin’s theoryOnce Darwin’s theory had been published to widespread debate and acclaim, discussion was often made more difficult by the persistent assumption that evolution must necessarily involve some kind of progress or development from the simple to the complex. This notion was present in the account of évolution in human society by the French philosopher Auguste Comte, and it was central to the metaphysical theories of the English speculative philosopher Herbert Spencer. Already in 1858, a year before On the Origin of Species appeared in print, Spencer was enthusiastically endorsing ‘the Theory of Evolution’— by which he meant the transformational theory of Lamarck, which Darwin’s work was set to supersede — and his keen advocacy of Darwin’s theory led to some confusion between Darwin’s ideas and his own. Even now, biologists have frequently had to explain that the theory of evolution concerns a process of change, regardless of whether the change can be regarded in the long run as ‘progress’ or not.

Nevertheless, despite his reluctance to call evolution by that name, Darwin did famously dare to use the corresponding verb for the very last word in his book:

From so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

A version of this blog post first appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Image Credit: “Origin of Species” by Paul Williams. CC BY NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The evolution of the word ‘evolution’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Brain function and brain surgery in children with epilepsy

Our actions, thoughts, perceptions, feelings, and memories are underpinned by electrical activity, which passes through networks of neurons in the brain. As a child grows and gains new skills their brain changes rapidly and brain networks are formed and strengthened with learning and experience. Neurons within brain networks form a unique representation of a person’s external and internal world, storing information from the past and capturing new experiences and knowledge. A person’s brain will continue to develop throughout their life, but the greatest changes take place early.

Epilepsy affects around one in every 100 people, most of whom experience their first epileptic seizure during childhood or old age. Seizures are the result of abnormal electrical activity in neurons, which disrupts normal brain function and behaviour: people may abruptly change what they are doing, lose consciousness, or suddenly fall down to the ground and shake. Frequent seizures can have a profound effect on a child’s cognitive abilities, such as their attention, reasoning skills, language, and memory. The recurrent abnormal electrical activity disrupts the function and development of the healthy brain networks. Children with severe epilepsy often don’t learn as quickly as their peers, and as a result often fall behind in school.

Medications usually control epilepsy well, but in 30% of people, the drugs just don’t work. Where the source of abnormal electrical activity can be pinpointed in the brain, surgery can be option for treatment. However, surgery for epilepsy is not straightforward: whilst taking out the brain tissue responsible for causing seizures, the surgeon might also remove tissue that supports important cognitive abilities. This happened in 1953 to a young man called Henry Molaison. To treat his highly disabling epilepsy, surgeons removed tissue in both of the temporal lobes of his brain. The procedure was successful in treating his epilepsy, and in many ways he was unchanged — he retained his sense of humour, language skills, intellect, interests, and values. But Henry couldn’t keep hold of any new personal memories. At age 82 he died with the memories of a 27-year-old man.

Comparison of healthy brain (bottom) and different temporal lobe surgeries in three children with epilepsy (above). Image by Caroline Skirrow and Torsten Baldeweg. Used with permission.

Comparison of healthy brain (bottom) and different temporal lobe surgeries in three children with epilepsy (above). Image by Caroline Skirrow and Torsten Baldeweg. Used with permission. Although we now know that the temporal lobes are vital for creating and storing new memories, they continue to be vulnerable to frequent, devastating and drug resistant seizures. As a result, temporal lobe surgery has endured as a treatment for epilepsy to this day. Surgical methods have changed notably. For example, brain tissue is now only ever removed from one temporal lobe, which limits risks of amnesia like Henry’s. Surgeons can also more carefully target brain tissue involved in generating seizures through modern brain imaging and new surgical techniques. Even so, adults with temporal lobe surgery often have memory problems. Most often, problems with remembering lists of words and stories are reported after surgery to the left temporal lobe.

Almost two thirds of children and adults are cured of their seizures after temporal lobe surgery. When faced with a choice between living with frequent and impairing seizures for the indefinite future, and brain surgery with risks to their cognitive abilities, many patients and their families choose surgery. Doctors will advise earlier surgery if a child rapidly starts to fall behind their peers and lose skills. The hope is that stopping the seizures will also stop the child from losing skills, and that the adaptability of the young brain will help them to recover after brain tissue has been removed.

Until recently, the long-term impacts of epilepsy surgery in childhood were unclear. New research published in the journal Brain finds that surgery for drug resistant epilepsy not only reduces seizures, but also has a protective effect on the memory of children. A group of 53 children with drug-resistant epilepsy, 42 of whom had temporal lobe surgery, were re-evaluated on average nine years after surgery. Seizures had stopped after surgery in 36 children (86%), and overall their memory had improved. Those with right temporal lobe surgery had improved memory for stories, whilst those with left temporal lobe surgery had improved memory for simple drawings. Better memory was seen after smaller surgical interventions, with less brain tissue removed. An earlier research report published in 2011 in the journal Neurology, showed that these same children also improved in a measure of intelligence (IQ) after surgery, which was linked to greater growth of grey matter in the brain after surgery.

This new research suggests that uncontrolled seizures may obstruct cognitive development in children. After temporal lobe surgery, brain function in healthy and intact brain tissue can be restored or even improved. However, while surgery benefited most children in this study, responses to surgery varied greatly from child to child. Some improved straight away, others lost skills and then improved, some showed no change, and others declined. The finding that less extensive surgery can help to improve memory may be an important first step in bettering outcomes after epilepsy surgery in children. Ever evolving and improving brain imaging techniques can help us to better target brain tissue causing seizures, and tailor surgery to help improve memory outcome. Beyond this, what makes different children respond so differently to severe epilepsy, and to epilepsy surgery remains a puzzle to be solved.

Featured image: Computed tomography of human brain. Department of Radiology, Uppsala University Hospital. Uploaded by Mikael Häggström. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Brain function and brain surgery in children with epilepsy appeared first on OUPblog.

Why Lincoln’s last speech matters

Lincoln’s last speech, delivered on 11 April 1865, seldom receives the attention it deserves. The prose is not poetic, but then it was not meant to inspire but to persuade. He had written the bulk of the speech weeks earlier in an attempt to convince Congress to readmit Louisiana to the Union. But Congress had balked. With Robert E. Lee having surrendered on 9 April, Lincoln now took the opportunity to take the case for Louisiana directly to the people.

Lincoln’s last speech was about reconstruction, a subject that had been on Lincoln’s mind from the beginning—it occupied “a large share of thought from the first,” he declared. Under the terms of his Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction, issued on 8 December 1863, loyal Louisianans had organized a new state government. They had also adopted a new state constitution that abolished slavery. But Congress had reservations about how many voters participated and whether the business of reconstruction belonged properly to the executive branch or to the legislative. Before going into recess until December, Congress had refused to seat Louisiana’s newly elected representatives.

The president was undeterred. As he often did to simplify difficult issues and appeal to people’s common sense he used an analogy to compare Louisiana’s new state constitution to what it might become in time. He said it was as the egg is to the fowl and asked whether “we shall sooner have the fowl by hatching the egg than by smashing it?” Many laughed at the analogy, and some were no doubt reminded of Lincoln’s admonition in 1862 that “broken eggs cannot be mended.” In editorials the next day, some insisted that rotten eggs should indeed be smashed, and Louisiana might just be a rotten egg.

Abraham Lincoln’s first inauguration which took place in Washington, DC. Lincoln stands underneath the covering at the center of the photograph. The scaffolding at upper right was being used in construction of the Capitol dome. Photo by Associated Press. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Abraham Lincoln’s first inauguration which took place in Washington, DC. Lincoln stands underneath the covering at the center of the photograph. The scaffolding at upper right was being used in construction of the Capitol dome. Photo by Associated Press. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons To persuade radicals that he took seriously their concerns that abolishing slavery was not enough and that more needed to be done, Lincoln publicly embraced limited black suffrage:

“It is also unsatisfactory to some that the elective franchise is not given to the colored man. I would myself prefer that it were now conferred on the very intelligent, and on those who serve our cause as soldiers. Still the question is not whether the Louisiana government, as it stands, is quite all that is desirable. The question is, ‘Will it be wiser to take it as it is, and help to improve it; or to reject, and disperse it?’ ‘Can Louisiana be brought into proper practical relation with the Union sooner by sustaining, or by discarding her new State government?’”

Lincoln had previously supported black suffrage in a private letter to Louisiana’s Governor Michael Hahn written in March 1864. Now he publicly endorsed the step. John Wilkes Booth was among the crowd who listened to Lincoln’s address. Hearing the call for limited black suffrage, Booth declared “that is the last speech he will ever make.” A conspiracy to assassinate Lincoln was already afoot. But Lincoln’s speech on 11 April, and his call for black suffrage, led to the tragic event of 14 April when Booth made good on his word.

Lincoln died “not in sorrow, but in gladness of heart.” We will never know what might have been had he lived to complete his second term, but one statesman grasped fully the tragedy when he predicted hat “the development of things will teach us to mourn him doubly.”

Featured Image: Lincoln Memorial and a drained reflection pool. Photo by Jason Pratt. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr

The post Why Lincoln’s last speech matters appeared first on OUPblog.

Literary fates (according to Google)

Where would old literature professors be without energetic postgraduates? A recent human acquisition, working on the literary sociology of pulp science fiction, has introduced me to the intellectual equivalent of catnip: Google Ngrams. Anyone reading this blog must be tech-savvy by definition; you probably contrive Ngrams over your muesli. But for a woefully challenged person like myself they are the easiest way to waste an entire morning since God invented snooker.

My addiction started innocently enough, when my student sent me an Ngram with ‘Shelley’, ‘Byron’, ‘Keats’, and ‘Romanticism’ as search terms since 1800. Like a genie at your command, Google will search all the books it has ever scanned looking for the occurrence of your terms and chart them. Thus, Ngrams are perfect for intellectual horse races, since mentions of names are a rough index of influence. Take those four dragon slayers of traditional thought — Marx, Darwin, Nietzsche, and Freud — and plot those proper nouns since 1850 until Google’s current end-date, 2008. What one gets is the pattern that one might expect with the work of a great intellectual. Nietzsche is the flattest parabola and has chugged along a plateau since the First World War. Darwin, too, surged from 1850 to 1890, then gently declined to the Second World War but has stayed consistent since. It is Marx and Freud, perhaps unsurprisingly, who show both enormous elevations and precipitous declines. Marx shot off in 1920 to reach dizzying heights in 1980, but has fallen from grace dramatically; Freud took off soon after his death in 1939 and stayed high from 1950 to 1990, but he, too, has plunged since then. Sic transit gloria mundi.

That intellectual parabola is evident in another four-horse race. Let a literary professor who is ambivalent about Theory release the four great Francophone intellectuals in the field — Foucault, Derrida, Lacan, and Barthes — in 1970. They remain remarkably flat until 1980; by the middle of that decade Foucault and Derrida have pulled ahead of the field (with Foucault a racing certainty) and all reach high points around the new millennium. Then the parabola exerts its gravitational pull, and all four terms show pronounced declines in the last five years or so — in the English-speaking world that is; not in the French. ‘Hurrah’, says the unreconstructed Leavisite in me: until I run a two-horse race between my intellectual beloved and Derrida since 1930. Derrida takes the lead from Leavis in 1980 and disappears into the empyrean. Leavis quietly fades, and even though Derrida’s recent decline is marked, he still towers over the ancient British literary critic — as one would expect.

So much for intellectuals. The parabola shape is exactly what one would expect when new ideas are presented, find their disciples, and eventually, inevitably, fade — though Darwin’s longevity is a significant exception to that rule. (Is that to do with the natural sciences versus the social ones? Or the remarkable capacity of Darwinism to leak into other intellectual disciplines besides biology?) How do poets and novelists shape up? Leavis had his ‘Great Tradition’ of Anglophone novelists: Jane Austen, George Eliot, Henry James, and Joseph Conrad. If I start them in 1880 (as references before that date are insignificant) what I get is pure chaos, compared with thinkers of a more formal variety. Joseph Conrad is a tiny figure, I must report straight away, with deep regret. Take him out and one gets a ragged range of astonishing rises and falls, but some smoothing eventually begins to show something of a pattern.

Lord Byron coloured drawing. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Lord Byron coloured drawing. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. All were quiet, generally speaking, until around 1940 when a huge though erratic spike took place that lasted until — reader, can you guess? — 1970. What we are surely seeing is the rise of the study of the serious novel in English departments right around the Western world, until those departments themselves began to decline and took their pet authors with them, nearly fifty years ago. Of the four, James had the most staggering rises and falls; but a two-horse race between him and Mark Twain were to be announced at Doncaster this weekend, I know where I’d put my money. Since 2005 Twain has taken off for the stratosphere, while James has continued to coast towards obscurity.

Not perhaps unexpected, these results. I was gratified by running four twentieth-century masters against each other since 1950. Hemingway is going nowhere; Woolf is hanging on in quiet desperation; Joyce shows vast peaks in the 1970s and the 1990s (the latter surely part of the Theory effect); and my favourite (ever the Leavisite), D. H. Lawrence, whom I would have expected to be six feet under, given our general attitude towards him, climbed after the Lady Chatterley trial of 1961, peaked in 1970 (who remembers the film of Women in Love?), dribbled away most grievously until about 2003, but is staging a comeback of hockey-stick proportions since that date, much higher now than the other three. (This is when I do not want to be told that an identity named Lawrence has won American Idol or Britain’s Got Talent, unbeknownst to me, and is kinking the data. Let me have my dream.)

But I am the editor of a new selection of Lord Byron’s letters and journals, and I have one more story to tell. Let me take the ‘big six’ Romantic poets — Blake, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Shelley, and Keats — and regrettably drop William Blake, because his name is common. Let me also drop Shelley, because there are two Shelleys of literary renown. But let me add Jane Austen. And let us run the five from 1800 to 2008 in the English corpus overall — though the American and British records are strikingly similar in any event. Byron of course takes off in 1812 and dominates the field until the new millennium. The pattern is again observable with varying degrees of smoothing: steady rise in all of them (though Keats and Austen off a far smaller base) until 1900. Keats and Austen plateau then; the other three Romantics drop precipitously with the new century, with the War, and with the arrival of Modernism. And then, in 1920, the pendulum starts to swing in the other direction. All rise, Keats soars, and they all re-plateau at a far higher rate between — reader, can you guess? — 1940 and 1970. Like the great novelists (but coming earlier, in the twenties rather than the forties) the great Romantics have hitched their wagons to the rise of the English discipline. Calamitous drop between 1970 and 1980; new lower plateau; and then, since 2000 a clear sign of recovery. That recovery is most beautifully to be seen in the most beautiful of English novelists when I add her alongside Lawrence, Woolf, Hemingway, and Joyce since 1950. Between about 2000 and 2004 Jane Austen was no more popular than Ernest Hemingway. Since then she has taken off like a rocket (I assume courtesy of the British film industry) and is breathing down D. H. Lawrence’s neck. And my dark horse, the other Nottinghamshire supernova, Lord Byron? He is a rather distant third.

The moral of this story is that the intellectuals, the philosophers, and the scientists have their stratospheric rises and vast influences, as their ideas are born and taken up by others. But once those ideas decline there is no coming back for them. Imaginative writers have far less momentous effects, as a general rule; but they can refute the parabola-effect and come back, again and again as they are rediscovered. I’ll live with that.

The post Literary fates (according to Google) appeared first on OUPblog.

May 8, 2015

How can we reconstruct history on the silver screen?

A perpetual lament of historians is that so many people get their historical knowledge from either Hollywood or the BBC. The controversies that surrounded Lincoln and Selma will no doubt reappear in other guises with the release of Wolf Hall, based on Hilary Mantel’s popular historical novel. Historical films play an outsize role in collective historical knowledge, and historians rightly bemoan the inaccuracies and misleading emphases of popular film and television; no doubt a generation of viewers believe that the Roman Republic was restored by a dying gladiator.

However, these reactions are somewhat misplaced. The problem with historical films is not so much the historical falsities, as it is the kind of narrative vehicle always deployed. Hollywood has a problem with form, not facts.

Historians, especially popular ones, feel comfortable launching factual critiques rather than formal ones because they themselves generally present their own research in prose narratives that depict the past as a settled issue. As most academic historians will insist, however, the past is a messier business than our clean narratives imply.

Popular historians, just like Hollywood histories, borrow heavily from the rich legacy of realism, especially what Roland Barthes termed the “reality effect” of realist discourse, the network of details and signifiers that are marshaled to give the illusion of immediacy (in the literal sense of “not-mediated”). Historians who tell us just how cold it was when Washington crossed the Delaware are deploying historical facts that perform the same function Austen’s description of a ballroom. No wonder some theorists of history dub mainstream historical narratives as “realist,” and that realist novels translate so well into realist cinema. The Victorian triple-decker maps wonderfully onto a long BBC mini-series, and even more impressively, a realist classic like Austen’s Emma can either work as historical comedy (Emma, 1996) or contemporary comedy (Clueless, 1995).

“Hollywood has a problem with form, not facts.”

Realism in fiction, cinema, and history has been so successful because of the unique pact it offers to readers and viewers. Realism is adept at hiding its own labor, which is why no mode is better at inducing a suspension of disbelief, for example during my binge watchings of Game of Thrones. In terms of history, however, such a pact has social costs: a reader immersed in a impressively rendered account of ancient Rome might feel like they are present at the stabbing of Caesar, but such an illusion implies that the past is a vistitable place. It’s not. We can look at its postcards and souvenirs—the documents of a historical archive—but no plane will take us there. History is an affair of the present, a profession and occupation for historians, and a process of reading or watching for the rest of us. For a population raised on historical realism, the dilemma is not so much factual as procedural, as viewers and readers are rarely granted access to the laborious and fractured work of historical reconstruction.

If the mode of realism moves so fluidly between fiction, cinema, and history, but proves socially worrisome for historical transmissions, then we might look to a mode that has not had much success in either film adaptations or historical appropriation: modernism. Why does Austen work so well on the screen, but never Woolf or Proust? For one thing, the plots (but not narratives) of Mrs. Dalloway or Swann’s Way are hopelessly dull: woman goes for walk and buys flowers for a party; boy cries and goes on a walk and then later takes another walk. (The only successful translation of modernism to screen remains Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, which demonstrates the extent to which one must violate a work such as Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.) Historical narrative has also been modernist-averse. Historians have had no trouble borrowing from Balzac or Tolstoy, but leave Joyce and Mann to their experiments.

“Movie Theater” by Sara Robertson. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

“Movie Theater” by Sara Robertson. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr. What would a work of modernist history even look like? We could list some examples from creative historians, but let’s see what happens in cinema when modernism and history collide. Michael Winterbottom’s 24 Hour Party People (2002) is a history of the Factory label, which for a brief time made Manchester the world’s music capital. (Some might quibble with my use of the word “history” here, but us Joy Division fans will insist on the gravitas of the material, and that the Factory story is equal to the fall of Rome.) Rather than employing a realist mode, Winterbottom shows us the seams of his work, his-story. British comedian Steve Coogan plays Factory head Tony Wilson, but in one scene Wilson himself has a cameo in which he disagrees with the portrayal of the events of the scene. This is history, but history as argument, not as a settled case. Ir is small wonder that when Winterbottom opted to adapt a work from the English literary canon, the result was Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story (2005), which is a film about the making of a film based on the novel, which is a narrative about constructing a literary narrative. Viewers coming away from Winterbottom, I’ll argue, will have more productive discussions and arguments about history than those watching standard historical recreations. Instead of picking out factual elements that, if just fixed, would provide a perfect history, Winterbottom viewers debate the very process of narrative construction itself. Such a debate is modernism’s great legacy.

Image Credit: “Movie” by Van Ort. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How can we reconstruct history on the silver screen? appeared first on OUPblog.

Body weight and osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis is a chronic condition of the synovial joint. The disease develops over time and most commonly affects the knees, hips and hands, and less commonly the shoulder, spine, ankles, and feet. It’s a prevalent, disabling disease, and consequently has a formidable individual and social impact. Approximately 10-12% of the adult population have symptomatic OA, and knee OA alone is considered more responsible for increasing the risk of mobility disability (requiring help to walk or climb stairs) than any other medical condition in people aged 65 and over.

OA reduces the quality and quantity of life. By using Quality adjusted life Years (a measure of disease burden taking life quality into account) it can be said that the average, 50-84 year old, non-obese person with knee OA will lose 1.9 years. With obesity, this figure increases to 3.5, and estimated quality-adjusted life expectancy falls by 21% to 25%. Such an impact is similar to that of metastatic breast cancer, showing that OA of any kind should never be underestimated.

Studies like these show the importance of weight control in the management of OA. Excess weight burdens weight-bearing joints like the back, hips, knees, ankles and feet, and when applied to joints with OA, increases stress and worsens symptoms. The relationship is also causal in the opposite direction. Abnormal loads on joints overwhelm their capacity for self-repair, and trigger cartilage mechanisms that produce harmful material, which can lead to the joint’s destruction.

While not everyone who has OA is overweight, obesity is considered a great risk factor for its development. A body Mass Index of over 30 increases the risk of OA in women by fourfold, and in men by almost 5 times. Researchers have noted the increased risk in obese patients of OA in non-weight-bearing joints, for example, the thumb. Fat cells release molecules causing inflammation in the whole body, affecting all susceptible joints. These molecules not only increase risk of developing OA, but also its severity.

Feet on scale by Bill Branson, National Cancer Institute. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Feet on scale by Bill Branson, National Cancer Institute. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Luckily, even a few kilograms of weight loss can have a beneficial effect. Losing five kilograms has been shown to reduce the risk of developing OA by half, and one study showed a 10% body weight reduction can result in up to a 50% reduction in pain. 38% of participants in the same study even reported no pain after they’d taken steps to lose weight.

Many health professionals use the body mass index (BMI in units of kg/m2) to assess patient’s weight, with a BMI of less than 25 indicating a normal weight, 25 to 29.9, overweight, and 30 or above, obese.

BMI = Weight (Kg)/Height2 (Metres2)

The relationship between obesity and OA is undeniably complex, varying from patient to patient, but the bottom line is that joints react badly to excess weight. With the number of OA patients expected to double by the year 2020, due in large part to the prevalence of obesity, and the graying of the ‘baby boomer’ generation, OA’s impact on healthcare resources will inevitably increase. Most western countries already spend 1 to 2% of their gross domestic product on arthritis care. The good news, however, even for sufferers of OA, is that positive changes and efforts to lose weight can make an enormous difference to both joint and general health.

The post Body weight and osteoarthritis appeared first on OUPblog.

How complex is net neutrality?

Thanks to the recent release of consultation paper titled “Regulatory Framework for Over-the-top (OTT) services,” for the first time in India’s telecom history close to a million petitions in favour of net neutrality were sent; comparable to millions who responded to Federal Communications Commission’s position paper on net neutrality last year.

Since the controversial term “net neutrality” was coined by Professor Tim Wu of Columbia Law School in 2003, much of the debates on net neutrality revolved around the potential consequences of network owners exercising additional control over the data traffic in their networks. Presently the obvious villains in the show are the Telecom Service Providers (TSPs) and the Internet Service Providers (ISPs) as they provide the last mile bandwidth to carry the content and applications to the end users.

Net neutrality is a specific approach to the economic regulation of the Internet and requires context in the wider literature on the economic regulation of two-sided markets.

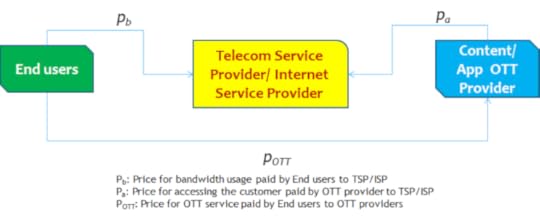

A platform provider (TSPs; ISPs) connects end consumers and over-the-top content (OTT) as given in the diagram below.

As per the theory of two-sided markets, the provider is justified in charging a toll to avoid congestion in the network. The toll can be raised from the end user or the OTT or both. The consumer is usually more price sensitive than the OTT so the tendency of the ISP is to raise the toll from the OTT.

The market power of the provider would result in a total levy (sum of levy on OTT and end user) that is too high from the point of view of efficiency. Even if the levy falls within the efficient range, it may tend to be in the higher parts of the range. This tendency is checked by ‘cross-group externalities’ – the value enhancement obtained by the end users from the presence of OTTs and vice versa. Cross group externalities soften the impact of the market power of the provider. Nevertheless, the fact of market power cannot be denied, given the low likelihood that an ordinary OTT can hurt a provider’s business by refusing to connect through that provider.

The principles of static efficiency outlined above do not suggest that over-the-top contents cannot be charged, only that market power of the ISP needs regulation. However the principle of dynamic efficiency, i.e. the optimization of the rate of technological progress in the industry, suggests that OTTs, especially startups, need extra support. Indeed the rapid growth of the Internet is a result of the low barriers to entry provided by the Internet. When the considerations of dynamic efficiency outweigh the considerations of static efficiency there may be justification in reversing the natural trend of charging OTTs and, instead, charging consumers. This has been the practice so far. It must however be noted that innovation is also needed in the ISP layer.

The situation becomes more complex when there is vertical integration between an OTT and a TSP/ISP. This vertical integration can take several forms:

App store of a Content Service Provider (CSP) bundled (preferred bundling) by the TSP/ISP; Peering arrangements between ISP and CSP; ISPs providing content caching services, becoming content distribution networks, or even content providers.Examples of such vertical integration, small and big, are many. Recent announcements by Google that they will provide Internet access through balloons. and storing its data on the servers of ISPs for better access speeds.

One view on vertical integration is that it allows complementarities to be tapped and is undertaken when the gains outweigh the known restrictions in choice faced by the consumer. For this view to hold, all linkages should be made known to the consumer, who must be deemed to be aware enough to understand the consequences. The other view is that vertical integration inhibits competition as potential competitors have to enter both markets in order to compete.

Further, when a provider provides communications services on its own, there is a conflict of interest with communications over-the-top content, for example between voice services provided by a telco and Skype.

As we contemplate moving away from the traditional regime of the Internet, we must therefore be prepared to countenance the curbing of dynamic efficiency and the limitation to competition due to vertical integration and conflicts of interest between the provider and the OTT.

The following are some of the principles that emerge from economic models:

There is efficiency of congestion pricing and the admissibility of charging above marginal cost for a toll good, if marginal cost is less than average cost. The water bed effect: in two-sided markets where one side is multi-homing and the other is single homing, the intermediary can make high profits of the multi-homing side and pass on some of these profits to the single homing side. Social welfare may decrease with net neutrality if the caps are sufficiently diverse. Quality may decrease with tiered pricing because of the incentive of providers to degrade the quality of the best effort Internet in order to force everyone to pay for access.Finally, the objectives of regulation must also include universal access to the Internet.

The following approach can be suggested:

There should be no distinction made for OTTs transmitting the same kind of data (e.g. VoIP, audio streaming, video streaming, video download); If there is a conflict of interest, then there should be an attempt to create a level playing field between the service provided by the provider and the OTT which is in competition with that service. The pricing in this area can be under forbearance by the regulator; A portion of the Internet can be reserved as the ‘classical Internet’ where OTTs are not charged at all, and a minimum quality of service is assured in a ‘best effort paradigm’.It is also a valid position that principle 3 is not workable in the light of current regulatory capacity on quality of service. First the regulatory capacity should be built and then the three principles adopted. Until then OTTs should not be charged.

It is important to discuss the business models of large OTTs (e.g. Google and Facebook) and their market power in the context of the debate on net neutrality. For examples, Google AdWords sponsored search platform ranks the advertisements based on the maximum bid price per clickthrough offered by the corresponding advertiser and is based on Generalized Second Price auction. Hence those who bid lowest will end up in the 100th or 1000th pages of the search page. This is akin to “fast laning” in the context of net neutrality based on payment by the advertiser to platform provider. Further, Google has more than 65% of the search market. The share is even higher in India (the only exception to Google’s dominance is China). Google’s search algorithm is proprietory and is also vertically integrated with services such as email (Gmail) and shopping (Google Compare).

The important point is significant market power and associated negative externalities can either come from TSPs/ISPs or from large OTTs. Two wrongs do not make one right. Hence the debate on net neutrality should consider perspectives from both sides, while controlling both in the interest of continued innovation and rapid diffusion of service.

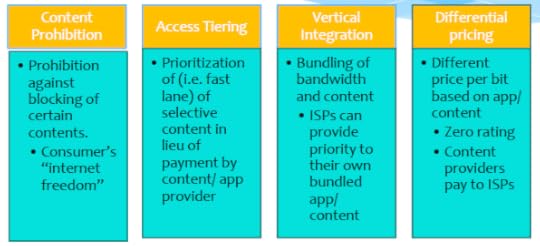

The following are the four broad issues with reference to net neutrality.

The case in which all bits are accorded the same priority, but are priced differently is a hybrid case of net neutrality. While it satisfies net neutrality with respect to priority it does not satisfy with respect to price. Zero rating is an indicative of this where the bits of selected applications are priced at zero for the consumer that fall under this plan while they are not given either higher/ lower priority compared to others. However, zero rating is a form of an extreme pricing. We can envision a situation that this will lead to large OTTs tying up with large TSPs/ISPs to provide zero rating scheme. Smaller and start-up OTTs will be left out of this equation due to economics of subsidy.

The other case is when TSP charges the same for each bit, but prioritizes certain OTT content. This case involves TSP implementing technologies such as advanced cache management and Deep Packet Inspection amongst others. From the consumer point of view, it provides better Quality of Experience (QoE) without additional price. Hence can possibly increase consumer surplus. This may also involve close cooperation and agreement between select content and service providers. This also might decrease the quality of experience of other content services that are not in the scheme.

Image credits: (1) “Towers” by davide ragusa, CC0 via Unspalsh. (2) Charts courtesy of the authors.

The post How complex is net neutrality? appeared first on OUPblog.

Hillary Clinton and voter disgust

Hillary Clinton declared that she is running for the Democratic Party nomination in a Tweet that was sent out Sunday, April 12. This ended pundit conjecture that she might not run, either because of poor health, lack of energy at her age, or maybe she was too tarnished with scandal. Yet, such speculation was just idle chatter used to fill media space. Now that Clinton has declared her candidacy, the media and political pundits have something real to discuss. Her tweet was followed by staged media events in her “listening” tour: the ever-fervid investigative press reported her entering a Mexican chain restaurant, and ordering a chicken dish with a side of guacamole. At least she was not confused between guacamole and mushy green peas, unlike a prominent British politician was a few years ago.

The U.S. electoral system might confuse the British with a presidential campaign already underway well-before the election that will take place in November 2016. While Britain is in the throes of a current election (pitting Tories against Labour, with the Scottish National Party as a wild card) that will end today, American voters see Hillary Clinton, going unchallenged at this point, for the Democratic Party nomination. Meanwhile, the Republicans have some-odd twenty candidates are vying for their party’s presidential nomination.

The British and American electoral systems are quite different, but they share one thing in common -many voters on both sides of the Atlantic are disgusted with politics-as-usual. In America, only about fifty percent of eligible voters (those bothering to register) vote in presidential elections. Those declaring themselves independents, not aligned with either party, compose thirty percent of the electorate. Large numbers of British and American voters simply believe that the political classes do not represent their interests and campaign pledges by candidates just don’t mean much. It’s all theatre to get media coverage and play to their political bases in hopes that the growing independent vote will swing their way.

What’s striking about American politics is that the primary and party convention systems were developed to ensure voters’ voices were heard and to take control away from political bosses and insiders. The American Founders who wrote the U.S. Constitution in 1787 feared above all else political parties and the excesses of majoritarian rule. They distrusted direct democracy, feared demagogues, and were terrified by centralized government that they believed could be corrupted by self-interested factions. By George Washington’s second term, however, political parties had emerged in loose coalitions around John Adams-Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson-James Madison.

The emergence of these new proto- political parties left the question as to how party presidential nominees were to be selected. The U.S. Constitution did not provide a guide to this issue. Party nominees at first were chosen by caucuses held by members of Congress. In 1831, a short-lived Anti-Masonic Party held the first national convention with state delegates voting for the presidential nominee. The national convention system for selecting party nominees was taken up by the National Republican Party (a precursor to the Whig Party) a short time later, followed by the first Democratic national convention a short time later.

The People March. Public domain via Pixabay

The People March. Public domain via Pixabay Still, the convention system had not taken firm root. In the presidential election of 1836, the recently formed Whig Party avoided a national convention and nominated regional candidates. By the next presidential election cycle in 1840, however, the Whigs held a national convention. With the emergence of the Republican Party in 1856, and the continuation of the Democratic Party, the two-party system was well-established in American politics, with an occasional challenge of third parties that did not go anywhere, even when they excited discontented voters.

National party conventions became the mainstay of American politics. Delegates from across the country came together for days of celebration, endless speeches, demonstrations, and roll calls. Votes were held back, deals made, and negotiations took place in smoke-filled rooms where political bosses negotiated final presidential nominees. It all made for exciting press, but local and state political bosses often had the final say in who was nominated.

As the late 19th century drew to a close, reformers called for an end of politics-as-usual. Reformers called for the primary elections that allowed for votes to select their candidates. Because state governments control election rules, the primary system was a kaleidoscope of different rules in different states.

Demands for full voter participation in primaries, easing of eligibility rules, and the selection of candidates continued to be heard. Following the tumultuous Democratic National Convention in 1968, new rules were implemented by reform Democrats headed by George McGovern that prodded most states to hold primaries and establish quotas for black, female, and community delegates.

The single impetus for the emergence of the American two-party system with its presidential primaries and national conventions was the call for democracy – let the voices of the people be heard. The age of mass media and television though meant any candidate wanting to win election needed big money to run a campaign. Hillary Clinton expects to spend more than $2 billion in her campaign, double what Barack Obama spent to win reelection in 2012.

The electorate has expanded in both Britain and the United States. Both systems today allow for greater voter participation. Yet, the irony is that more and more voters feel disconnected from politics, their elected representatives, and government itself. This discontentment challenges politics- as-usual, even when country expects the first women—Hillary Clinton—to be nominated by a major political party to run for the President of the United States.

Featured image credit: Statue of Liberty. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Hillary Clinton and voter disgust appeared first on OUPblog.

May 7, 2015

What if printed books went by ebook rules?

I love ebooks. Despite their unimaginative page design, monotonous fonts, curious approach to hyphenation, and clunky annotation utilities, they’re convenient and easy on my aging eyes. But I wish they didn’t come wrapped in legalese.

Whenever I read a book on my iPad, for example, I have tacitly agreed to the 15,000-word statement of terms and conditions for the iTunes store. It’s written by lawyers in language so dense and tedious it seems designed not to be read, except by other lawyers, and that’s odd, since these Terms of Service agreements (TOS) concern the use of books that are designed to be read.

But that’s OK, because Apple, the source of iBooks, and Amazon, with its similar Kindle Store, are not really publishers and not really booksellers. They’re “content providers” who function as third-party agents. And these agents seem to think that ebooks are not really books: Apple insists on calling them, not iBooks, but “iBooks Store Products,” and Amazon calls them, not Kindle books, but “Kindle Content.”

Here’s an excerpt from Apple’s iBooks agreement:

You acknowledge that you are purchasing the content made available through the iBooks Store Service (the “iBooks Store Products”) from the third-party provider of that iBooks Store Product (the “Publisher”); Apple is acting as agent for the Publisher in providing each such iBooks Store Product to you; Apple is not a party to the transaction between you and the Publisher with respect to that iBooks Store Product; and the Publisher of each iBooks Store Product reserves the right to enforce the terms of use relating to that iBooks Store Product. The Publisher of each iBooks Store Product is solely responsible for that iBooks Store Product, the content therein, any warranties to the extent that such warranties have not been disclaimed, and any claims that you or any other party may have relating to that iBooks Store Product or your use of that iBooks Store Product.

Wade through twenty-two pages of this and Finnegans Wake will be a walk in the park, or as Apple might call it, a pedestrian experience integrating analog recreational green space. And if you get hurt in the park while reading an iBook, don’t blame Apple—they’re simply go-betweens who provide the product but take no responsibility for it:

IN NO EVENT SHALL LICENSOR BE LIABLE FOR PERSONAL INJURY OR ANY INCIDENTAL, SPECIAL, INDIRECT, OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES WHATSOEVER, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION . . . DAMAGES OR LOSSES, ARISING OUT OF OR RELATED TO YOUR USE OR INABILITY TO USE THE LICENSED APPLICATION, HOWEVER CAUSED, REGARDLESS OF THE THEORY OF LIABILITY (CONTRACT, TORT, OR OTHERWISE) AND EVEN IF LICENSOR HAS BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES. [Caps in the original]

Conventional printed books, or “book books”—which in the old days we simply called books—don’t require a click-to-agree before reading. Imagine if Gutenberg made his readers accept these conditions from Amazon’s Kindle Store before they could read the Bibles he printed on that first printing press, back in the 1450s (readers is an archaic term for what we call end users today):

Unless specifically indicated otherwise, you may not sell, rent, lease, distribute, broadcast, sublicense, or otherwise assign any rights to the Kindle Content or any portion of it to any third party, and you may not remove or modify any proprietary notices or labels on the Kindle Content. In addition, you may not bypass, modify, defeat, or circumvent security features that protect the Kindle Content.

I mean, try plugging that into Google translate and see what comes out.

When Amazon entices you to buy an ebook now with 1-click, you’re not really buying that book, you’re renting it. As Kindle’s TOS puts it,

Kindle Content is licensed, not sold, to you by the Content Provider.

Ebook publishers limit what you can do with their products as well. This copyright notice for Julia Angwin’s Dragnet Nation, published by Macmillan, warns:

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law.

What if that applied to “book books” as well? An analog version of Kindle’s Digital Rights Management agreement (DRM) wouldn’t let you lend your Gutenberg Bible to a friend, give it away, sell it at a garage sale, donate it to an adult literacy program, or use it to press flowers. Nor could you make it publicly available, for example, by reading it aloud during a religious service. Plus it turns out that unlike Apple, which has more money than God, Gutenberg barely made ends meet selling his Bibles, even though the few copies that survived the ravages of time are worth millions today. If Gutenberg had had the foresight to license his Bibles instead of selling them outright, his descendants and heirs would still own the rights to those first books, or as they might prefer to call them, those Analog Scriptural Piety Artifacts (aSPAs).

What if you had to click to agree before reading one of Gutenberg’s 15th-century Bibles—er, I mean, Scriptural Piety Artifacts?

Today a digital content provider can take back their ebook if you violate any of the DRM’s terms. As Amazon puts it:

Your rights under this Agreement will automatically terminate if you fail to comply with any term of this Agreement. In case of such termination, you must cease all use of the Kindle Store and the Kindle Content, and Amazon may immediately revoke your access to the Kindle Store and the Kindle Content without refund of any fees. . . . If you do not accept the terms of this Agreement, then you may not use the Kindle, any Reading Application, or the Service.

That’s not an empty threat. When Amazon discovered it had sold copies of George Orwell’s 1984 even though it didn’t own the American rights to that particular edition, it quietly and without notice removed the title from Kindles throughout the United States. That struck readers as the height of Big Brotherism, but the giant bookseller didn’t care, because like Big Brother, Amazon had the majesty of the law behind it. If Gutenberg Bibles were covered by a similar End-User Licensing Agreement (EULA) that you had to agree to by inking your initials with your goose quill before you could access its holy content, Gutenberg dot com could have your Bible repossessed if it thought you weren’t pious enough, or if you spilled coffee on it, or if you used it not to read but for hiding money or pressing flowers.

Today’s readers accept these ebook licensing agreements without a thought; despite the legal shrink wrap, ebooks are selling more and more. But if Gutenberg’s legal team had figured out a similarly creative way to limit what readers could do with analog books, I’m wondering whether readers at the time would have stuck with their parchment and their clay tablets, and the print revolution might never have taken place. After all, the vendors of ebooks aren’t selling books as physical objects, like Gutenberg and his successors did. Instead, they’re selling us the right to read. That’s more like selling us the right to vote, or think, or breathe. Gutenberg’s readers wouldn’t have put up with that. Today’s readers shouldn’t have to put up with it either.

A version of this blog post first appeared on The Web of Language.

Image Credit: “iRiver Story eBook Reader Review” by Andrew Mason. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post What if printed books went by ebook rules? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers