Oxford University Press's Blog, page 660

June 1, 2015

What can green fluorescent proteins teach us about diseases?

Green fluorescent proteins, or GFPs for short, are visibly advancing research in biology and medicine. By using GFPs to illuminate proteins otherwise undetectable under the microscope, scientists have learned a great deal about processes that take place within our cells. Particularly beneficial are the advances scientists have made in understanding diseases—from HIV to malaria and cancer, to name a few—by utilizing GFPs in their research.

But what are these advances, and how do scientists actually use GFPs in their experiments? In Illuminating Disease: An Introduction to Green Fluorescent Proteins, Marc Zimmer details the stories of many scientists who made great strides in their research by using GFPs. In this slideshow we’ve summarized some of those stories, accompanied by captivating images of GFPs in action.

DISCOVERING GFPs

DISCOVERING GFPs For over 40 years, Osamu Shimomura studied Aequorea victoria, crystal jellyfish that thrive in the Pacific Northwest. Through his research, Shimomura revealed that A. victoria emit green light through a cellular process that involves two proteins. The first protein, aequorin, emits a blue light energy when it binds to calcium. The second protein absorbs the energy from the aequorin and reemits it as green light. The process of converting the blue light to green light is referred to as fluorescence, and the protein responsible for this conversion is appropriately named green fluorescent protein, or GFP.

GFPs and HEART DISEASE

GFPs and HEART DISEASE Scientists often tag other proteins in our cells with GFPs—by binding the GFPs to these proteins—as a way to monitor proteins of interest throughout a variety of biological processes. For example, in humans there is a protein that regulates the calcium levels in our body, and in doing so, this protein controls our heartbeat—the calculated contractions in our muscle cells that take place through reactions with free calcium. To mimic this process, and understand why it’s so important, Andres Villu Maricq scanned the genome of Caenorhabditis elegans to find a regulatory protein similar to the one found in humans. After tagging this protein with GFPs, Maricq could test what happens when this protein’s function is turned off. Depending on location, the regulator protein governed the timing of swallowing, digestions, and fertilization, thus demonstrating the important role regulator proteins play in our bodies.

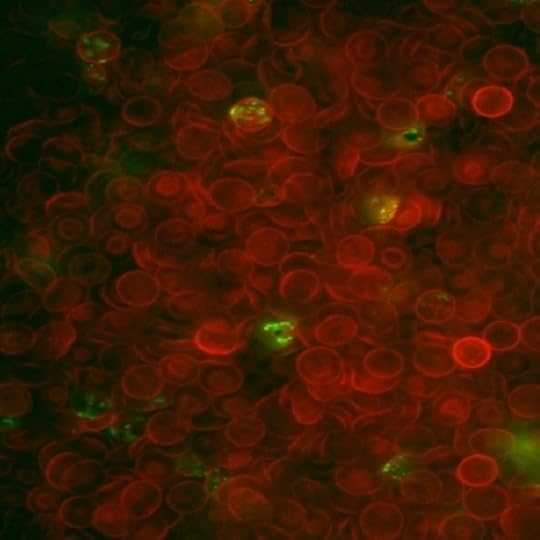

GFPs and MALARIA

GFPs and MALARIA Malaria has been infecting people for as long as humans have been recording history. The disease is caused when a protozoan host called Plasmodium enters the body, and the most common form of transmission is through mosquito bites. Since Plasmodium targets hemoglobin in the blood stream, one common response to malaria is the sickle cell mutation. When the hemoglobin in blood cells of individuals with this genetic mutation are attacked by Plasmodia, the blood cells collapse—thereby inhibiting the parasite from living within the human body. By tagging Plasmodia with GFP, scientists can observe this phenomenon first hand.

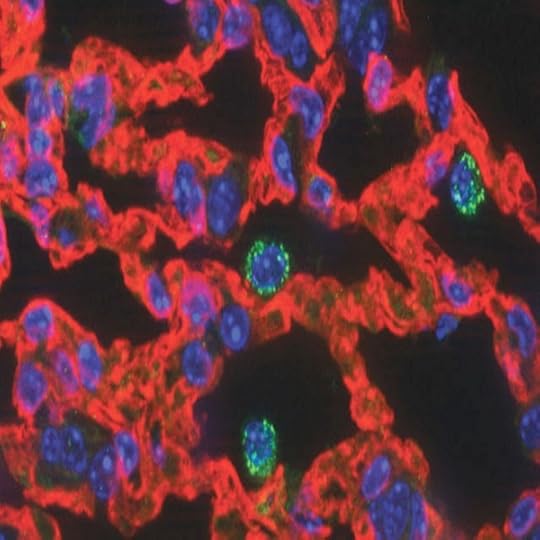

GFPs and CANCER

GFPs and CANCER By orthotopically implanting GFP-expressing cancer cells in nude mice—a perfect model organism because nude mice’s immune systems do not reject foreign cells—scientists can observe the development and spread of cancer cells, a process called metastasis. Because they are hairless fluorescence imaging software and scanners allow scientists to view the tumors through the mice’s skin, while they are still alive. Every strain of cancer acts in a different way, and accordingly responds to treatment in various manners. As such, illuminating cancerous tumor activity with GFPs has been very helpful in advancing scientists’ understanding of this disease, because it allows them to witness these varying strains firsthand.

GFPs and HIV/AIDS

GFPs and HIV/AIDS One of the deadly aspects of the HIV virus is its ability to kill host T-cells. Scientists such as Gary Nabel and his colleagues have used GFPs to demonstrate exactly how the HIV virus accomplishes this task. Most mammalian cells protect themselves against DNA damage with repair enzymes; however, in HIV activated T cells a special repair enzyme that initiates cell death is released. Nabel and his colleagues revealed this process by illuminating these enzymes with GFPs. Scientists also study HIV/AIDS treatments using GFPs. For example, Eric Poeschla and his colleagues have tested the effectiveness of inserting both a gene known to inhibit HIV-1 and FIV (feline immunodeficiency disorder) in rhesus monkeys and a gene that codes for GFPs into cats. This model for gene therapy in humans with HIV is still under investigation, but seems to be producing positive results.

TO LEARN MORE ABOUT GFPs

TO LEARN MORE ABOUT GFPs To learn more about GFPs and what they have taught scientists about diseases, check out Illuminating Disease: An Introduction to Green Fluorescent Proteins.

Slideshow Image Credits:

Image 1: Aequorea victoria emitting florescent light, courtesy of Steven Haddock.

Image 2: Rhythm proteins within a genetically modified C. elegans, courtesy of Ken Norman, University of Utah.

Image 3: Red blood cells infected with a GFP-expressing strain of malaria. This image was originally published in Nature News and has been used with permission.

Image 4: Breast cancer cells labeled with GFPs. This image was originally published in Cell and has been used with permission.

Image 5: Kitten with GFP-tagged restriction factor from a rhesus monkey, testing its effect on FIV. This image was originally published in Nature Methods and has been used with permission.

Image 6: GFP-expressing spinal motor neurons in a chicken embryo. This image was originally published in Cell and has been used with permission.

Feature Image: Mammalian axons illuminated with GFPs. This confocal image was originally published in Nature and has been used with permission, courtesy of Jean Livet.

The post What can green fluorescent proteins teach us about diseases? appeared first on OUPblog.

Has ISIS become the new pretext for curtailing our civil liberties?

A series of measures put in place in the years following 9/11 have now become a fixture of Western government: mass warrantless surveillance, longer periods of detention without charge, and greater state secrecy without accountability. The United States finds itself at the vanguard of this movement with its embrace of executive authority to carry out targeted killing of its own citizens. Many of these measures arose in part as an over-reaction to the threat of al Qaeda. But they were also due in part to a plausible concern that terrorism had come to pose a threat of a much greater magnitude than was previously thought possible. For many, terrorism had become closer in nature to war than to crime, justifying a host of invasive measures.

Almost 15 years later, the continuing argument for those measures rests on the belief that terrorism still poses a threat tantamount to war. In the wake of recent attacks in Paris, Ottawa, and Sydney, governments have sought to make this argument by linking the threat of domestic terrorism to ISIS. The link is necessary because ISIS is now the only entity capable of serving as a plausible basis for the claim that jihadist terrorism continues to be potentially war-like in scale. The need to see terrorism on this scale to justify extraordinary measures points to an earlier shift in perceptions of terror.

Prior to 9/11, terror on domestic soil was seen as a criminal act, regardless of its scale. Conventional prosecutions followed the Oklahoma City and Air India bombings, and earlier events involving the IRA and other political groups.

After 9/11, terrorism in much of the West came to be understood in terms of what can be called the harbinger theory. This was a belief that 9/11 was not an anomaly in the history of terrorism, but the harbinger of a new order of terror — one in which future attacks on the part of al Qaeda or an analogous group would soon occur in a major Western city on a similar or greater scale, possibly involving weapons of mass destruction. It now seemed plausible that terrorism could involve tens or hundreds of thousand of casualties, even millions, the threat was comparable to war. As a consequence, for Dershowitz, Posner, and others, the conventional limits on state power in constitutional and human rights were no longer tenable.

In the United States, the harbinger theory still forms a crucial basis for national security policy. Following the Snowden revelations, for example, President Obama defended the continuing use of bulk metadata surveillance by asserting: “the men and women at the NSA know that if another 9/11 or massive cyberattack occurs, they will be asked by Congress and the media why they failed to connect the dots.” A bill before Congress purporting to overhaul the Patriot Act has been lauded for ending bulk data collection by the NSA. But to appease concerns about “another 9/11,” it will retain the practice of bulk data collection by shifting it to third parties.

The evidence of domestic terrorism in Western nations in recent years runs directly contrary to the harbinger theory. As Mueller and Stewart and others have shown, the future of terrorism is likely to be more like the pre-9/11 past: lone-wolves or small, disparate groups with more limited capabilities. Recent attacks in Paris, Ottawa, and Sydney confirm this. One of the principals in the Charlie Hebdo killings had received training from an al Qaeda affiliate in Yemen in 2011, but little more. The men involved in the Ottawa and Sydney events were known to police and acted alone.

Security. CC0 via Pixabay.

Security. CC0 via Pixabay. Yet, in keeping with the harbinger theory, governments have been quick to draw a connection between recent terror and ISIS, a large transnational entity with greater capacity. In the wake of the attack on Parliament, Canada’s Prime Minister Stephen Harper asserted: “The international jihadist movement has declared war…” The epicenter of the threat is the “entire jihadist army that is now occupying large parts of Iraq and Syria.” The US and French governments have also tied ISIS to the prospect of further domestic terror, ignoring ample evidence that ISIS is, as Ahmed Rashid put it, “not waging a war against the West.”

Despite the tenuousness of a link to ISIS, Canada, France, and Australia have sought to justify significant new measures in light of it. Canada’s bill C-51 gives security intelligence service the unprecedented power to seek a warrant to breach any Charter right — not only those protecting against unreasonable search and seizure — if believed to be necessary to thwart a terror plot. France is debating a mass surveillance bill, while Australia will likely adopt a law that strips terror suspects of citizenship.

In each case we have to ask: What will the new powers accomplish? Would they have prevented attacks in Sydney, Ottawa, or Paris? Looking back, it’s hard to see how. Even with full surveillance, it would likely have been impossible to know how far along the path of radicalization certain individuals were prepared to go, until they got there. Yet by maintaining the perception of domestic terrorism as part of a larger war, questions of cause and effect become moot, and de facto emergency powers persist.

The post Has ISIS become the new pretext for curtailing our civil liberties? appeared first on OUPblog.

Who was Amelia Edwards?

Surprisingly few people have heard of Amelia Edwards. Archaeologists know her as the founder of the Egyptian Exploration Fund, set up in 1882, and the Department of Egyptology at University College London, created in 1892 through a bequest on her death. The first Edwards Professor, Flinders Petrie, was appointed on Amelia’s recommendation and her name is still attached to the Chair of Egyptian Archaeology.

Edwards did more than anyone in the late nineteenth century to encourage interest in ancient Egypt. During a trip along the Nile in 1873, at the age of 42, she was so excited by doing a little amateur digging at Abu Simbel that she returned to England determined to devote the rest of her life to promoting Egyptology as a scientific discipline. She read up on the subject and she taught herself hieroglyphics. In 1877 she published a lengthy account of her trip, A Thousand Miles up the Nile, which was readable, as well as scholarly, and beautifully illustrated with her own watercolours. The book marked a turning point in women’s travel writing by concentrating on the traditionally masculine sphere of history and research and mostly ignoring female domestic life, which Amelia said she had very little opportunity to study.

![Abu Simbel drawn by Amelia B. Edwards, 1870, via Wikimedia Commons [public domain].](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1433188965i/15061384._SX540_.jpg) Abu Simbel drawn by Amelia B. Edwards, 1870. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Abu Simbel drawn by Amelia B. Edwards, 1870. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Within a decade Amelia Edwards had become such a specialist on ancient Egypt that she was regularly contributing to academic journals. She was also canvassing professional and popular support for excavation and for the systematic and accurate recording of monuments. She had enormous energy and physical stamina as well as a talent for public speaking which was brilliantly displayed in 1889 when she embarked on an extraordinary lecture tour to the United States. For five months she criss-crossed the continent, sometimes speaking to audiences of over two thousand people. When she broke her arm a few hours before a lecture in Columbus she found a surgeon to set the bone and went ahead with the event. She was awarded three honorary degrees from American universities.

Not surprisingly, Edwards’ life is remembered in the context of archaeology. But she was a polymath. The trip up the Nile was a mid-life journey undertaken when she had already made her name as a travel writer with an account of a trek through the Dolomites. Published in 1873, Untrodden Peaks and Unfrequented Valleys is still one of the best travel books ever published on the region and an exuberant and witty introduction to the glorious beauty of the mountains and their previously isolated communities. Unlike the Alps, the region was not overcrowded with tourists. There were plenty of opportunities for sketching, botany, and mountain-climbing. Yu might even hear Verdi arias, perfectly performed in a village inn by local tenor. For Edwards, a talented singer herself, this was a bonus.

![Photo of Amelia B. Edwards, 1890, via Wikimedia Commons [public domain].](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1433188965i/15061385.jpg) Amelia B. Edwards, 1890. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Amelia B. Edwards, 1890. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. By the time she made the trip to the Dolomites, Edwards was also a well-known novelist. She wrote articles, poems, and mystery stories for several journals including Charles Dickens’s Household Words, and she was one of the first contributors to the feminist English Woman’s Journal, launched in 1858. Her best-selling novel, Barbara’s History, touches on edgy but popular Victorian themes of bigamy and infidelity, while its eponymous heroine is feisty, well-travelled, and erudite.

Amelia Edwards later became a vice-president of the Society for Promoting Women’s Suffrage. She was one of a number of multi-talented European women who changed the nature of women’s travel writing. Jane Dieulafoy, Ella Sykes, Isabella Bird, Lady Anne Blunt, and Gertrude Bell all contrived in their different ways to break the conventional boundaries of female travel. Whether single or married, they no longer accepted that their interests and writing should be confined to literary and domestic subjects in order to guarantee publication. Although they sometimes differed in their attitude towards the women’s suffrage campaign, they all asserted their right to be taken seriously in the masculine world of science, geopolitics and diplomacy.

Archaeologist? Travel writer? Novelist? Journalist? Musician? Linguist? Fund-Raiser? Feminist? Amelia Edwards was more than equal to any task. After her death, at the age of 60, her cousin, Matilda Betham-Edwards, said that if she had lived longer Amelia would probably have thrown Egyptology to the winds and embarked on a new project with equal success. “Who knows? She might have thrown herself heart and soul into the Women’s Rights agitation … Not only might we have had in her a powerful statesman and party leader, but a lady Prime Minister.”

Headline image: Abu Simbel. Photo by Dennis Jarvis. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Who was Amelia Edwards? appeared first on OUPblog.

May 31, 2015

Will data privacy change the law?

It is customary to distinguish between three different forms of jurisdiction. As is well known, prescriptive (or legislative) jurisdiction relates to the power to make law in relation to a specific subject matter. Judicial (or adjudicative) jurisdiction, as the name suggests, deals with the power to adjudicate a particular matter. And, finally, enforcement jurisdiction relates to the power to enforce the law put in place, in the sense of arresting, prosecuting, and punishing an individual under that law.

However, not least due to the increase in cross-border contacts stemming from the Internet, it is useful to also consider a fourth type of jurisdiction. Indeed, what we can call “investigative jurisdiction” protects a state’s power to investigate a matter without exercising adjudicative jurisdiction, applying prescriptive jurisdiction, or enforcing actions against the subject of its investigation. It is particularly useful in the context of data privacy law and consumer protection—areas where complaints are often best pursued by bodies such as privacy commissioners/ombudsmen and consumer protection agencies.

In light of this, it does not make sense to bundle investigative jurisdiction with enforcement jurisdiction, as is traditionally done. Indeed, the crucial importance of distinguishing investigative jurisdiction from other forms of jurisdiction was at the core of a 2007 decision by the Federal Court of Canada.

In Lawson v Accusearch, Inc.[2007] 4 FCR 314, the Privacy Commissioner of Canada was forced to defend, in court, her decision to decline to investigate a complaint made by Lawson of the Canadian Internet Policy and Public Interest Clinic against a corporation based in the United States. Sean J. Harrington of the Federal Court stated that:

I agree with her [the Privacy Commissioner of Canada] that PIPEDA [Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act] gives no indication that Parliament intended to legislate extraterritorially. […] [However, the] Commissioner does not lose her power to investigate because she can neither subpoena the organization nor enter its premises in Wyoming. […] It would be most regrettable indeed if Parliament gave the Commissioner jurisdiction to investigate foreigners who have Canadian sources of information only if those organizations voluntarily name names. Furthermore, even if an order against a non-resident might be ineffective, the Commissioner could target the Canadian sources of information. I conclude as a matter of statutory interpretation that the Commissioner had jurisdiction to investigate, and that such an investigation was not contingent upon Parliament having legislated extraterritorially[.]

Moreover, the ongoing dispute between Microsoft and the United States government, in which the government attempted to force Microsoft into providing details about an e-mail account held by its subsidiary in Ireland, further illustrates why it is the right time to distinguish, define, and delineate investigative jurisdiction.

As I have argued elsewhere, there are strong reasons to think Microsoft will be successful in the dispute. Yet the very fact that dispute arose in the first place highlights the fact that contemporary jurisdictional thinking has failed to adequately address the challenges posed by the Internet in general, and perhaps cloud computing as well. This failure may partly be blamed on the law’s unwillingness to part with traditional categorisations rather than recognizing models and structures that better correspond to the new technological reality.

Image Credit: “Microsoft” by SimeonK. CC BY NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Will data privacy change the law? appeared first on OUPblog.

Over-consumption in America: beyond corporate power

It is easy enough for critics to trace America’s over-consumption of things like food and fuel to the excess power of our profit-making corporations. Americans consume more food and fuel than Europeans in part because these companies in America are better able to resist taxes and regulations. Yet the deeper source of this greater corporate power is surprisingly non-corporate.

America is the king of over-consumption when it comes to both food and fuel. CO2 emissions per capita and obesity rates in America are in each case twice as high as averages on the European continent. Corporate power contributes to both outcomes when it blocks tax and regulatory measures that might correct the excess. But private companies have more room to do this in America because of the nation’s unique culture, political institutions, and material resources.

Starting with fuel, Americans consume far more oil, coal, and gas than Europeans because consumption here is less heavily taxed. Combined federal and state consumption tax rates on petroleum in the United States are only a sixth of the level in France, and a seventh of the level in Italy, Norway, and the Netherlands. Gasoline taxes in America are just an eighth of the average in Western Europe. Higher fuel taxes are blocked because our fossil fuel industry is so much larger and richer, and thus better positioned to lobby for governmental favors. We have this bigger fossil fuel industry because our proven reserves of coal, oil, and gas are in each case two to three times as large as in all of Europe combined. A fundamental material resource endowment is thus at the base of the over-consumption outcome.

Regarding America’s over-consumption of food, our distinct national culture is more important than resource endowments. Compared to Europeans, Americans believe far more in personal responsibility, and much less in social or governmental responsibility. Freedom-loving, individualistic Americans do not want the government telling them, or their children, what to eat or how much to eat. Only 23% of Americans believe the federal government should have any direct role at all in setting nutritional standards for public schools, and only 22% support taxes on caloric soda. Industry-wide regulations on food advertisements to kids are legally blocked in America by a unique presumption that such ads are “commercial speech” protected under the First Amendment. This libertarian legal view enjoys bipartisan political support. When the Obama Administration in 2011 dared to suggest “voluntary” guidelines on food ads to children, Congress rejected the idea by a 3-to-1 vote in the House and a 2-to-1 vote in the Senate.

The New Fred Meyer on Interstate on Lombard by By Original: lyzadanger Derivative work: Diliff. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The New Fred Meyer on Interstate on Lombard by By Original: lyzadanger Derivative work: Diliff. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. There is also a populist streak in American culture, one that tends to block regressive consumption taxes on the poor. Only 8% of public sector revenues in America derive from consumption taxes, compared to roughly 20% in Europe. Congress failed in 2009 to support a cap-and-trade measure to limit fossil fuel consumption in part because – as Warren Buffett said at the time – it was “pretty regressive.” Grocery sales in America are essentially untaxed for the same reason. European governments routinely impose consumption taxes on food (using a value added tax, or VAT), which helps to explain why food is 30% more expensive in Europe, and hence more lightly consumed. In America, Republicans as well as Democrats have rejected the VAT approach. In 2010, a resolution against any federal VAT tax was approved in the Senate by a 6-to-1 margin, once fears were voiced that it would “cripple families on fixed income.”

America’s unique political institutions are another important non-corporate source of corporate power. The nation’s pre-modern Constitution was intentionally written to create a weak central government, and to the present day it provides both corporate and non-corporate actors with multiple “veto points” they can use to block government action. The Senate itself is a major veto point, since majority votes are often blocked on the floor by a rule requiring 60 votes simply to take a vote, or in committee by an informal tradition that allows individual Senators to place a “hold” on any measure they don’t like. In 2009, the cap-and-trade bill to reduce fossil fuel consumption actually passed the House, but was then blocked in the Senate. President Clinton’s fuel tax proposal in 1993 also made it through the House, only to be blocked in the Senate.

Exploring these material, cultural, and institutional foundations of America’s over-consumption in some detail, little in the way of corrective action will be possible. Our nation’s dominant policy response to both climate change and obesity will be adaptation rather than mitigation. The result in the first case will be deeper international inequalities, and in the second case deeper domestic inequalities. But that could be the subject for another entry.

Featured image: Breezewood, Pennsylvania by SchuminWeb. CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Over-consumption in America: beyond corporate power appeared first on OUPblog.

Authoritative speech

There are various more or less familiar acts by which to communicate something with the reasonable expectation of being believed. We can do so by stating, reporting, contending, or claiming that such-and-such is the case; by telling others things, informing an audience of this-or-that, or vouching for something; by affirming or attesting to something’s being the case, or avowing that this-or-that is true.

What do these acts have in common? Each is an instance of the kind of speech act known as an assertion.

Acts of assertion are of great philosophical significance.

For one thing, assertions are apt for transmitting knowledge, and so they are of interest to the theory of knowledge. (What is knowledge, such that it can be transmitted through speech in this way?) For another, it is by asserting things that speakers typically express their beliefs. As a result, acts of this type can shed light on the relation between mind and language, thought and speech.

Third, assertions appear to be part of a very complicated social practice, one in which speakers and hearers expect things of one another, and hold one another responsible in various sorts of ways. For this reason, assertions should be of interest to social philosophy and ethics. (How does it come to pass that speakers and hearers have these expectations of one another, and what entitles us to hold each other responsible in these ways?)

The systematic study of assertion, then, would appear to require a mixture of philosophy of language, philosophy of mind, epistemology (theory of knowledge), ethics, and social philosophy. Is there any way to discern order in this chaos?

Recently, a number of philosophers have proposed that we think of assertion as a particular type of move in a “language game.” On the most basic versions of this proposal, the rule for making the move of assertion is simple: one must do so, only when one is relevantly authoritative on the matter at hand; that is, only when one has the relevant evidence or knowledge. For example, a speaker who asserts that it is sunny, but who fails to have evidence (let alone the knowledge) that it is sunny, has violated the assertion rule.

According to such a proposal, the assertion rule characterizes the nature of assertion, and distinguishes it from other kinds of speech act (requests, commands, speculations, promises, offering congratulations, and so forth). In effect, the assertion rule suggests that “assertions are the only speech act backed by the promise of the speaker’s authoritativeness”. If we assume that this rule is common knowledge to all members of the language community, then the rule of assertion would appear well-positioned to account for assertion’s philosophical significance.

Meyer London giving a speech, 1915. The Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives in the ILR School at Cornell University. CC BY 2.0 via kheelcenter Flickr.

Meyer London giving a speech, 1915. The Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives in the ILR School at Cornell University. CC BY 2.0 via kheelcenter Flickr. To see this, suppose Sally makes an assertion that it is sunny today, and that Nancy observes and recognizes the assertion that is being made. Then (given that the assertion rule is common knowledge) it is common knowledge that Sally’s act is proper only if she has the relevant evidence or knowledge: this is something that both Nancy and Sally know, and that each knows that the other knows. But then Nancy would hold Sally responsible for having the relevant evidence or knowledge, and Sally would expect as much.

On this account, the rationality of Sally’s hope of being believed lies in this: she can anticipate that Nancy appreciates the promise of relevant authoritativeness in her assertion. Insofar, as Nancy is entitled to think that this promise was kept, Nancy is entitled to think that Sally has the relevant evidence or knowledge, in which case it would be reasonable for Nancy to believe her.

Something along these lines would also appear to explain the role assertion plays in the spread of knowledge.

In a similar way, we might think to develop an account of the ethics of communication by using the assertion rule. On such a view, what we are entitled to expect of one another in our information-exchanging practices is governed (at least in part) by that rule. The rule itself entitles hearers and speakers to expect things of one another, and the failure to satisfy those mutual expectations generates the possibility of moral censure.

The assertion rule also holds out the prospect of shedding light on other features of our linguistic practices. For example, we might hope to be able:

to explain why conditions of anonymity have characteristic effects on the quality of assertions made under such conditions. to understand when it is proper to retract an assertion under conditions of disagreement. to model the way in which members of various groups “calibrate” their expectations of one another in contexts of information exchange. to highlight the nature of what Miranda Fricker calls the “epistemic injustice”, perpetrated when a hearer dismisses another’s assertion out of prejudice. to think about the reformation of our practices of assertion, so as to ensure fair treatment to all in our knowledge communities.In sum, assertion is a topic that will repay sustained philosophical reflection, and the rule of assertion appears to unify what otherwise might seem to be a host of unrelated facts about our linguistic practices.

The post Authoritative speech appeared first on OUPblog.

Unequal at birth

Recent events in Baltimore, Ferguson, and other places have highlighted the explosive potential of discrimination and inequality. Much attention has been paid to police practices, the long-term effect of joblessness, and the trauma of the criminal justice system incarcerating large numbers of African-Americans. This focus on the present is understandable. It is also insufficient. There is a need to understand and address the huge disadvantages, and indeed disabilities, imposed on future generations by pre-natal conditions.

As James Heckman, a Nobel Prize-winning economist, has noted, “Children born into disadvantage are, by the time they start kindergarten, already at risk of dropping out of school, teen pregnancy, crime, and a lifetime of low-wage work. This is bad for all those born into disadvantage and bad for American society.” Disastrous is more like it. The injustice of inequality actually precedes birth as its corrosive effects are at work already in the womb. With around 22% of African American families and 38% of children and youth living in poverty, the implications are profound.

Insights into the implications are found through combining an understanding of biology and economics—the focus of emerging field of economics and human biology. Thanks to the work of David Barker we now know that human capital formation begins in the womb. The nature of the fetus’ environment during the short period between conception and birth has lifelong consequences on it, including birth defects and chronic conditions such as coronary heart disease, stroke, type II diabetes, and hypertension. Babies born prior to the 37 weeks of gestation or weighing less than 5.5 pounds will be disadvantaged for the rest of their lives in just about everything—their height, cognitive abilities, educational attainment, employment, and their lifetime earnings. Those exposed to toxins or infections in the womb will be irreparably damaged. While we talk about equality of opportunity and equality of outcomes, the elephant in the room that we’ve been ignoring for the most part is that inequality–the disrupting social issue of our time–begins amazingly during those 37 weeks.

Here is where economics comes in—both economic conditions and economic methods. The environment of a fetus in midtown Manhattan, where the annual income is $2.9 million, is coddled: absolutely no toxins or infections, certainly no shortage of micronutrients, and a stupendous team of doctors will make sure that it sees the light of day with optimal weight under optimal circumstances. A few miles away, the fetus in the Melrose-Morrisania neighborhood of the South Bronx, where in some housing projects half the households have less than $9,000, the fetus faces a very different environment.

And the environment matters greatly. There are numerous of well-known negative effects if a fetus experiences stress, anxiety, abuse, poor nutrition, infrequent doctor’s visits, or no visits at all until the time of delivery because of lack of money and lack of health insurance. Inadequate micronutrients, insufficient vitamin B, or infections lead to all sorts of complications and suboptimal outcomes including birth defects, stillbirths, pre-term delivery, and low birthweight followed by high infant mortality. The emotional stress that invariably accompanies such poverty all too often makes things much worse as it leads to drug use or alcohol abuse.

Protests in front of the Ferguson Police Department (and fire station and municipal court), over the Thanksgiving weekend. Photo by Mike Tigas. CC0 1.0 via madmannova Flickr.

Protests in front of the Ferguson Police Department (and fire station and municipal court), over the Thanksgiving weekend. Photo by Mike Tigas. CC0 1.0 via madmannova Flickr. The data are stark and unmistakable. In every single metric that matters to long-run health or earning capacity African American babies are disadvantaged by the time they take their very first breath. Blacks have a much higher rate of preterm births than whites (20% vs. 12%). Low birth weight (LBW) is also a major setback (it is 8% among whites but 16% among blacks). Low birth weight, defined as a weight of less than 5.5 pounds, has harmful effects that last forever, such as stunted educational achievement and lower lifetime earnings, and is also a main cause of infant mortality. No wonder that the mortality rate among African American infants is more than twice that of whites and higher than that of 60 countries in the world in a league with Russia, Serbia, Thailand, and Sri Lanka. (Actually, those of Russia and Serbia are slightly better.) The Washington Post refers to it as a “national embarrassment.”

It is also very costly in terms of lives. Maternal mortality is high in the United States: 1 in 1800 pregnancies, which is about 6-7 times as high as in Western Europe where mothers have free medical care. The first year of medical costs for a preterm baby is some $32,000–ten times as much as for normal term infants–for a total cost of not less than $26 billion a year. In other words, neglecting the uterine environment during pregnancy has immense immediate financial consequences as well.

Although it is obvious, we should nonetheless stress that the fetus has no agency; it did not choose the womb in which it finds itself. Yet it will soon enter the world and have to bear the consequences and responsibility of its experience in the womb. The tremendous variation in its fate depending on the zip code of its conception cannot be considered “just”. Luck ought not be the basis of justice as the political philosopher John Rawls taught us. Yet, society has a tremendous stake in the fate of that fetus, because the future of the country depends on the fate of such fetuses.

Benign neglect is a no-win strategy. Pay later is inefficient, an immense waste of human and financial resources. At a time when some parents can afford to spend over a quarter million dollars on their children’s playhouses, it seems like we should be able to scrape enough money together to help provide optimal maternal environment. Warren Buffett said recently that the American Dream “has been an American Nightmare” for many families and we “can do better than that.” What better opportunity to start “doing better than that” and break the vicious cycle of poverty and inequality than during that miraculous nine months in the womb that separates conception from birth.

The post Unequal at birth appeared first on OUPblog.

An interview with the Editor of The Monist

Oxford University Press has partnered with the Hegeler Institute to publish The Monist, one of the world’s oldest and most important journals in philosophy. We sat down with the Editor of The Monist, Barry Smith, to discuss the Journal’s history and future plans.

What is the history of The Monist?

The Journal was founded by Edward Hegeler, a German entrepreneur who immigrated to the United States in 1856 and started a zinc manufacturing company in LaSalle, Illiniois. The company became extremely successful during the Civil War, in which Union artillery used cartridges with zinc components. In 1887 Hegeler launched Open Court Publishing Company with the goal of propagating Ernst Haeckel’s monism as an alternative to traditional religion. He attracted a number of dissident intellectuals to his cause, and succeeded in establishing a publishing forum in the US that would promote the sort of discussion of philosophical, scientific and religious ideas that he had known in Germany. The first issue of The Monist was published by Open Court in 1890, the Journal’s title reflecting Hegeler’s continuing interest in a quasi-religious version of Haeckel’s monism – a broadly Spinozistic belief in the unity of organic and physical nature, including social phenomena and mental processes.

After some false starts, Hegeler appointed Paul Carus, a more recent German immigrant, as editor of the Journal. Carus remained in this role until his death in 1919, when he was succeeded by his wife Mary, Hegeler’s daughter, who edited the Journal until her death in 1936.

Carus is notable not least for the role he played as patron, correspondent, and provider of much-needed moral, intellectual and financial support to C. S. Peirce. Carus interacted with many other prominent figures of his day, including Tolstoy, Edison, Tesla, Houdini, Einstein, Alexander Graham Bell, Upton Sinclair, Ezra Pound and Booker T. Washington, and his vast network of correspondents and collaborators also extended beyond the US and Europe to include the Far East. (D. T. Suzuki, later the world’s most prominent exponent of Zen Buddhism, worked in LaSalle for 11 years as assistant editor and translator of Asian religious and philosophical classics. Suzuki also translated Carus’s own Gospel of Buddha into Japanese for use in Buddhist seminaries in Japan.)

How has the Journal changed with the field over the years?

During the Carus period from 1890 to 1936 the Journal published work by almost all of the important intellectual figures of the day. This included philosophers such as:

Peirce, Dewey, Eucken, Poincaré, Schroeder, Trendelenburg (with a posthumous treatise edited by Eucken entitled “A Contribution to the History of the Word ‘Person’”), Cassirer, Frege, Lovejoy, Jourdain, Russell, T. S. Eliot, Kurt Grelling, Friedrich Jodl, Weiss, Hartshorne, Charles Morris, Neurath, C. I. Lewis, as well as Victoria, Lady Welby, Mary Boole, and Susan Langer

But The Monist also published thinkers prominent in other disciplines, including Mach, Boltzmann, Haeckel, Veblen, Hilbert, Ostwald, Julian Huxley, Lombroso, and Piaget.

With the death of Mary Hegeler Carus, the Journal ceased publication until 1962, when it was re-established by Mary’s daughter Elizabeth Hegeler Carus, the new manager of Open Court Publishing Company, which continued to function at the Hegeler-Carus Mansion in LaSalle, IL. Elizabeth appointed as editor the Peirce scholar Eugene Freeman, who was succeeded in 1983 by John Hospers, a prominent analytic philosopher and also the first ever candidate of the Libertarian Party in a US Presidential election. Under the reign of Freeman and Hospers the Journal took up from where Paul and Mary Carus had left off, publishing work by almost all the leading philosophers of the day, including (in roughly this order):

Chisholm, Toulmin, Donagan, Norman Malcolm, Fitch, Findlay, Grünbaum, Feinberg, Winch, Alistair McIntyre, Geach, Anscombe, Ackrill, Benacerraf, Körner, Garver, Hiż, Hamlyn, Spiegelberg, J.R. Lucas. J.J.C. Smart, Prior, Tooley, Laudan, Hampshire, Hesse, Dworkin, Jaegwon Kim, Thalberg, Armstrong, Asa Kasher, Peter Singer, Goodman, Margolis, R. M. Hare, Judith Thomson, Rorty, Edwards, Devitt, Fisk, R.H. Thomason, Barbara Partee, Stalnaker, Lehrer, Saarinen, Michael Ruse, Blanshard, Mandelbaum, Engelhardt, Stich, Fodor, Ruth Marcus, Herb Hochberg, John McDowell, Gareth Evans, Searle, Mourelatos, Scheffler, Quine, Lycan, Kivy, Warnock, Rorty, Sellars, Dennett, Grene, Firth, Fogelin, Gutting, Haack, Parsons, Veatch, Peter Forrest, Brandom, Michael Levin, Penelope Maddy, Georg Kreisel, Michael Friedman, George Smith, D.C. Phillips, David Woodruff Smith, Virginia Held, Chris Menzel, Hao Wang, Alston, Raz, Ernie Sosa, Foley, Lakoff, Van Cleve, Ginet, Jacquette, Isaac Levi, Richard Jeffrey, Kyburg, Wolterstorff, Stephen R. L. Clark, Korsgaard, Henry Allison, Onora O’Neill, Audi, Matson, Gian-Carlo Rota, John O’Neill, Gaus, T.H. Irwin, Annas, and Zemach.

In this era we see a move towards a more strictly philosophical focus, and above all towards mainstream Anglo-Saxophone philosophers, though there are also contributions from Finns such as Hintikka and Hilpinen, Austrians such as Haller, Czechs such as Čapek, Swiss such as Guido Küng, Germans such as Apel, and Frenchmen such as Vuillemin and Ricoeur. That the Journal was able so consistently to publish authors of such prominence was due not least to the initiation by Freeman of the practice of devoting each issue to some single theme, and including in each issue not only papers submitted for refereeing but also papers solicited by the editor. Freeman thereby continued, under a new set of rules, the tradition initiated by Paul Carus, whereby the editor of The Monist serves as a kind of intellectual entrepreneur.

The Hegeler-Carus Mansion in LaSalle, Illinois. In 1887, Hegeler launched Open Court Publishing Company in the mansion. CC-BY-SA- 2.0 via Flickr.

The Hegeler-Carus Mansion in LaSalle, Illinois. In 1887, Hegeler launched Open Court Publishing Company in the mansion. CC-BY-SA- 2.0 via Flickr. Can you say something about the factors which led you to be chosen as Editor of the journal?

When I took over as editor from John Hospers in 1991 I was still working as a philosopher of a rather traditional sort, focusing in part on philosophical ontology, in part on the analytic-Continental philosophical divide. I believe that I was chosen as editor not least because of my interests in the Vienna Circle, and in the wider tradition of analytic philosophy in the German-speaking world and in the former Austro-Hungarian Empire. My interest in libertarianism, and in the ideals of liberal education (thus of truth, reason, freedom of thought), surely also played a role. All of these were seen as positive qualities by the current generations of the Carus family, who still take a strong interest in matters philosophical.

How do you decide upon the themes for future issues and what themes do you have in the pipeline?

The choice of topics is in the first place opportunistic. For each issue I appoint an Advisory Editor who is responsible for devising the precise scope of the issue and for soliciting papers from prominent experts. My selection of topics then depends in part on identifying persons suitable for the task of serving as advisory editor, and in part on what topics can be predicted, roughly three years in advance, to be of interest to potential authors. There is a fine balance between originality of topic – its closeness to the cutting edge of what people are working on – and the existence of a cadre of philosophers who are already able to write intelligently about it.

There is however another factor, which has been working more or less behind the scenes in my choice of topics in recent years, reflected in the gradually increasing number of issues on topics in the area of ‘applied philosophy’ broadly conceived. The tendency is illustrated in the first and only double issue of the journal edited by Robert George on the topic of Marriage. It is illustrated in issues on themes such as Death and Dying, Academic Ethics, Nationalism, Cognitive Theories of Mental Illness, Genetics and Ethics, Sovereignty, Privacy, and Philosophy and Engineering. Issues in the pipeline in this spirit include: Conservatism, Philosophy of War, and Trust and Democracy.

Tell us about your work outside of the Journal.

I, too, have in recent years become progressively more and more engaged in work in applied philosophy – or more precisely: in work in applying ontology in fields such as medicine and biology, military intelligence, economics, or law. My work in all of these areas involves close collaboration with experts in the corresponding disciplines and also with computer scientists and data engineers. At the University of Buffalo I hold positions not only in the Department of Philosophy but also in Biomedical Informatics, Computer Science, and Neurology. Currently I am working for the US Air Force on an ontology of adaptive planning, and for United Nations on an ontology framework to support the consistent collection of data relating to the UN’s new set of Sustainable Development Goals. The role of ontologists, in projects of this sort, consists in building and formalizing coherent classifications – called ‘ontologies’ – of the entities and relations in the relevant domains. These ontologies then provide common benchmarks for the consistent description of data across disciplines and communities. The task of building and formalizing ontologies of this sort is still recognizably philosophical in nature – and I believe that the growing interest in applied ontology in so many different fields is revealing a new and potentially highly fruitful way in which philosophical ideas and methods can be of extra-philosophical significance.

The post An interview with the Editor of The Monist appeared first on OUPblog.

May 30, 2015

Getting to know Scott Morales, Stock Planning & Publications Coordinator

From time to time, we try to give you a glimpse into our offices around the globe. This week, we are excited to bring you an interview with Scott Morales, a US Stock Planning & Publications Coordinator in New York. Scott has been working at the Oxford University Press since July 2008.

What is your typical day like at OUP?

I handle corrections for reprints in the New York office. On a typical day at OUP, I check my e-mail and the Corrections mailboxes. Then I send out my corrections, take lunch, and spend the later part of the day working on reports. Sometimes I plan parties.

What is the most important lesson you learned during your first year on the job?

I learned the nuances of a 9-5 job, honestly. I had been temping for most of my existence prior. I also began to learn that, in order to understand OUP, I would have to brush up on my intuitive understanding of acronyms.

What’s the most surprising thing you’ve found about working at OUP?

The longevity of some people’s tenure here. I’m amazed to see that people have been here for 20, 30 years. Not because OUP isn’t a great place to work, but because in my background people don’t really stay in their jobs long.

What’s the least enjoyable part of your day?

Waking up early. Gross.

What is the strangest thing currently on or in your desk?

People who have been to my desk know that is a difficult thing to identify (I have a lot of stuff on my desk). If I had to pick the strangest, I suppose it would have to be either a trophy from a Carnival cruise trivia that I won, an Easter bunny toy that lays candy eggs, or perhaps a bottle of BBQ sauce. Or an ad from the 80s for a Wendy’s Bacon Double Cheeseburger Deluxe (only $1.99!). Top of my head.

What’s your favourite book?

Hmm, so much pressure. I recently finally read The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon and adored it. I’ll say that.

If you didn’t work in publishing, what would you be doing?

Well I’m an actor in my other life, so that I suppose? Or a fighter pilot.

Open the book you’re currently reading and turn to page 75. Tell us the title of the book, and the third sentence on that page.

“Scooting the damn thing down the hallway’s easy; getting it around the corners proves more difficult; but as he’s already mastered the space, understands when to shove and when to yank, he easily shimmies the table through the gray-carpeted labyrinth, until the window is straight ahead of him.” A Once Crowded Sky by Tom King

Who inspires you most in the publishing industry and why?

This might sound like I’m sucking up, but OUP really does inspire me. We are an organization committed to enhancing academia. We literally help the world learn. We may not be perfect, but that is an amazing contribution to society.

Tell us about one of your proudest moments at work.

We once raised a lot of money to help out staff that had been affected by Hurricane Sandy a couple of years ago by holding a fundraiser and a potluck. Some of the people who received help came up to me afterward and expressed how much it helped them and their families. That was cool.

If you could trade places with any one person for a week, who would it be and why?

Would I inhabit them, like Quantum Leap? If so, then Gary Oldman, so I could try to steal some of his acting secrets.

If you were stranded on a desert island, what three items would you take with you?

A Bible, a buffet restaurant, and a sweet tea factory, which would essentially make it like the suburbs.

How would you sum your job up in three words?

“Correct this book”

Most obscure talent or hobby?

I can tap dance like a champion.

Image Credit: “Film” by Marta Wlusek. CC BY NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Getting to know Scott Morales, Stock Planning & Publications Coordinator appeared first on OUPblog.

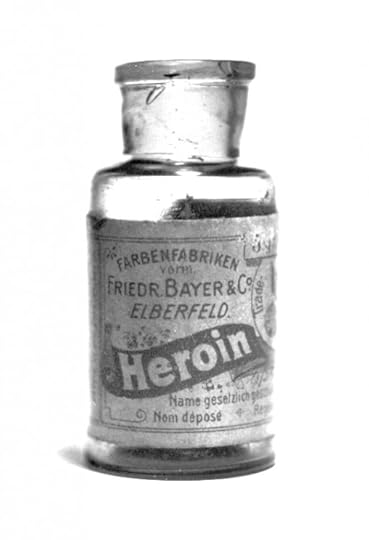

Harris Wittels: another victim of narcotics and America’s drug policy

Harris Wittels, stand-up comedian, author, writer, and producer for Parks and Recreation – and generally a person who could make us laugh in these seemingly grim times — died of a drug overdose at the age of thirty. He joins the list of people who brought pleasure to our lives but died prematurely in this manner: Corey Monteith, Whitney Houston, Philip Seymour Hoffman, John Belushi, River Phoenix, Janis Joplin, and Chris Farley, among others. Moralists will point out that these untimely deaths reveal the danger of narcotics, and they do, but they also reveal the dangers of our anti-narcotics legislation.

Heroin and cocaine aren’t good for your body, but they aren’t lethal drugs. They are only lethal when they are taken in excessive amounts, which generally occurs because they are sold on the street, without adequate control of quality or dose amounts. Many legal substances, including acetaminophen and sleeping pills, can kill you if taken in improper dosages. But few people die from them — unless they are trying to commit suicide — since they are marketed by reputable companies in carefully controlled and labelled form. These companies can’t market narcotics, however, because our policy is that selling or taking these substances is a serious criminal offense.

Pre-War heroin bottle, originally containing 5 grams of heroin substance, by Mpv_51. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Pre-War heroin bottle, originally containing 5 grams of heroin substance, by Mpv_51. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The reason for our narcotic laws, according to their proponents, is that we are trying to protect people from themselves. But declaring people criminals and putting them in prison seems like a peculiar way to protect them. Conviction and imprisonment are designed to punish, that is, to inflict harm. In practical terms, a conviction often ruins one’s career and prison often ruins one’s life. Another claim is that narcotics laws protect those dependent on the users, such as their partners or children. But even if a person inflicts indirect harm on his or her dependents by using drugs — failing to keep a job for example — it seems unlikely that those dependents are better off if the person is taken to prison and deprived of an entire career. As for using criminal punishment to deter others from undesirable behavior, our society allows the use of only blameworthy persons for this purpose. We might deter poor performance in school by imprisoning children who consistently get failing grades, but we tend to avoid such expedients.

It is certainly true that a person who is addicted to narcotics is likely to lead a sub-optimal existence. But we generally don’t declare people criminals for failing to achieve their full potential. Addicts are not the walking dead; they can have stable and productive lives, at least if they are not hounded and oppressed by the criminal justice system. Perhaps, had they not been opium addicts, William Wilberforce would have succeeded in abolishing slavery in the British Empire ten years earlier, Samuel Coleridge would have written more poetry (although he might not have written “Kubla Khan”), and Wilkie Collins would have developed another new genre besides detective fiction. Perhaps Sigmund Freud would have plumbed further recesses of the human mind if he hadn’t been a cocaine addict, and the Beatles would have stayed together and produced another fifteen albums if they hadn’t taken hallucinogens. But all these heavy drug-users contributed to our society, and the people listed above didn’t do so poorly either.

The real reason why we maintain our irrational narcotic policies is the survival of pre-modern morality, which can be described as a morality of higher purposes. According to that morality, people are supposed to serve the state and the society by contributing to the economic order. The defining feature of the substances that have been criminalized — which are after all quite different in their chemistry and their effects — is that they produce enjoyable experiences. This leads to concern that people will spend too much of their lives in a drug-induced haze instead of reporting to work in the office, the factory, and the toll booth.

But these laws are ineffective, they are cruel, they are phenomenally expensive. They corrupt the police, and they unleash savage criminal cartels on our democratic allies such as Columbia and Mexico. We need to distance ourselves from the old morality of higher purposes and embrace the newly developing morality of mental health and human self-fulfillment. For a fraction of the money that we spend in our hyper-aggressive, inhumane War on Drugs, we could provide treatment for everyone who wanted to escape from addiction. This would be a much better way to control the drug problem. And it would be nice to have Harris Wittels, Corey Monteith, Whitney Houston, Philip Seymour Hoffman, John Belushi, River Phoenix, Janis Joplin, and Chris Farley still with us to enrich our lives.

Featured image: Cocaine by sammisreachers. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Harris Wittels: another victim of narcotics and America’s drug policy appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers