Oxford University Press's Blog, page 689

March 12, 2015

Alhazen’s problem

The International Year of Light aims to raise global awareness about how light-based technologies can promote sustainable development and provide solutions to global challenges in energy, education, agriculture, and health. To celebrate this special year over the course of March, three of our authors will write about light-based technologies and their importance to us. This week, Stephen R. Wilk discusses the contributions of Alhazen to the field of optics.

One of the reasons that 2015 has been declared the International Year of Light is that it marks the 1000th year since the publication of Kitāb al-Manāẓir, The Treasury of Optics, by the mathematician and physicist Abu Ali al-Hasan ibn al-Hasan ibn al-Haitham, better known in Western cultural history as Alhazen. Born in Basra in present-day Iraq, he is acknowledged as the most important figure in optics between the time of Ptolemy and of Kepler, yet he is not known to most physicists and engineers.

A quick survey of my own optics books reveals that almost none of them even mention him. My first introduction to him came in the form of a Ripley’s Believe it or Not! cartoon that claimed his interest in optics was sparked by his contemplation of the iridescent colors of a soap bubble. I have not, however, been able to find any reference to the story outside of Ripley.

Much of the material in the first three books of the Treasury is concerned with color theory and visual perception. But you would think that the material in the fourth and fifth books, being devoted to the problems of reflection and refraction, would be of greater relevance. Aside from his ideas about vision, about the only element that gets touched on in most mentions of Alhazen is his provision of the earliest description of the camera obscura.

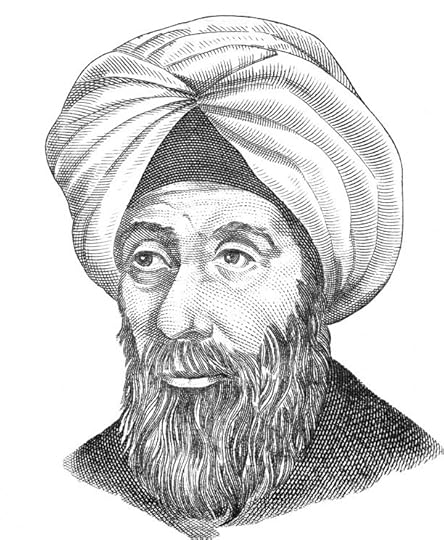

“Ibn al-Haytham [Alhazen] as shown on the obverse of the 1982 Iraqi 10 dinar note.” Scan by Jacob L. Bourjaily; Banknote produced by Iraqi government. CC by SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“Ibn al-Haytham [Alhazen] as shown on the obverse of the 1982 Iraqi 10 dinar note.” Scan by Jacob L. Bourjaily; Banknote produced by Iraqi government. CC by SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. He did much more, of course. He came very close to discovering the law of refraction. He solved multiple problems in reflection, building upon the notion that the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection, along with the tenets of geometry. That most people are unaware of this might be the real Alhazen’s Problem.

But there is one specific detail he examined that captured the attention of Christiaan Huygens and others who sought to find a simpler algebraic solution than the rather complex geometrical one found by Alhazen himself; Huygens described it as longa admodum ac tediosa–“too long and tedious”. The problem asks that, if light emanates from one point and reflects from a spherical mirror to a second given point, at which point does the ray strike the mirror? This has given rise to a whimsical name for the situation–Alhazen’s Billiard Problem–since it is equivalent to assuming that one strikes a ball on a circular billiard table with the aim of sending it to a designated second point. At what point on the circular cushion should one aim the ball?

It’s conceptually a simple problem and can be solved on the basis of the assumptions of circular geometry and the law of reflection. But the problem resists an easy solution using compass and straightedge.

Alhazen’s solution was achieved by use of six subsidiary proofs or lemmas (Arabic muqaddamāt). Alhazen was able to show, by purely geometrical arguments, that the location of the point on the circular mirror at which the reflection must occur lies at the intersection of that circle with a hyperbola.

Modern treatments solve the problem by a combination of analytical geometry, algebra, and trigonometry. At this point, the impatient engineer, who simply wants a solution, asks in exasperation, “Why don’t you simply divide up the circumference into equally spaced points, calculate the angles of incidence and reflection, and take the position where these are the closest? If you’re going to use a computer anyway, why not simply use the Brute Force approach?”

In fact, we may ask why it is that this problem is not more widely known among optical scientists and engineers. Reflection from a concave or convex spherical surface is one of the most basic problems in geometrical optics. It’s taught in every introductory class on geometrical optics, but Alhazen’s name is virtually never associated with it. Why not?

The problem, as stated above, is not one of great utility in optics and optical design. One rarely asks, “Where must a ray coming from point A and going to point B strike by spherical mirror in order to get there?” One asks, “Where do these rays, leaving point A, go after they have struck the spherical mirror?” In the usual paraxial optical formulation, the student uses the approximation that virtually every point from a point A that is further than a focal point away from a concave mirror will pass through the same point B in the corresponding image. Teaching them about Alhazen’s Problem will only confuse them, without the compensating virtue of teaching them a general principle.

So why is Alhazen’s problem important to anyone but circular billiards players? It’s because Alhazen himself did not see this as the end of his calculations, but as another step that was necessary for the solution of his ultimate problem–the way that light reflected from curved surfaces.

To cite historian A.J. Sabra:

“The problem of finding the reflection-point occurs in [The Treasury of Optics] as part of a long series of investigations of specular images which occupy the whole of Book V, and these investigations in turn presuppose a theory of optical reflection which is expounded in Book IV. Much of the character of Ibn Al-Haytham’s treatment of reflection-points can only be appreciated if understood with reference to this wider context… Ibn Al-Haytham was therefore aiming to solve a wider and more complex set of problems than “Alhazen’s problem” in Huygens’ limited sense.”

In other words, Alhazen’s “complicated and tedious” solution was simply one piece in his carefully argued development for calculating how light was reflected from non-planar mirrors. Concentrating only on this one piece of the puzzle might provide diversion for mathematicians, but that was not Alhazen’s goal. Modern beginning optical students do learn Alhazen’s results, although they no more use his methods than modern students of algebra use those of medieval scholars.

Image Credit: “Optics Final” by Bryan. CC by NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Alhazen’s problem appeared first on OUPblog.

Ten fun facts about the Irish Fiddle

Even though the harp is Ireland’s national symbol, the fiddle is the most commonly played instrument in traditional Irish music. Its ornamental melodies are more relaxed than the classical violin and improvisation is encouraged. The fiddle has survived generational changes from its start as a low-class instrument popular among the poor. Now, the Irish fiddle is playing an instrumental role in preserving traditional Irish music and culture.

Fiddles have been in existence as far back as the Middles Ages but the modern fiddle did not gain popularity in traditional Irish Music until around the 17th century. The violin and the fiddle are the exact same instrument. Some will argue that while a violin is a fiddle, not every fiddle is a violin. Old-fashioned musicians prefer the word ‘fiddle’ instead of ‘violin’ to differentiate their music and their style of playing from other music. The word “fiddle” is a colloquial term used in traditional or folk music references. The fiddle is called fidil or veidhlín in modern Irish. The fiddle thrived among rural populations in Ireland due to its low-cost, low maintenance and how easy it is to learn. Fiddlin Bill Henseley, Mountain Fiddler, Asheville, North Carolina by Ben Shahn, 1937. Library of Congress. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. The body of a fiddle is made of about seventy wooden components and the bow is wound with horse hair. The Irish Famine of 1845-1851 caused thousands of Irish natives to immigrate to the United States. At this time, many Irish musicians sought employment in minstrel and vaudeville shows to make decent money as fiddlers. There are many styles of Irish fiddle music that vary from county to county; Donegal, Sligo, Galway, Clare, Kerry and Cork to name a few. Generally, most fiddlers play upbeat music you can dance to. Sligo-style fiddler, Michael Coleman, popularized the fiddle in the 1920s with his commercial recordings of lively melodies and bouncy rhythms. Outside of traditional Irish dance music, the fiddle can be heard in New England’s country dance, western swing and upbeat bluegrass music in the upper South.

Fiddlin Bill Henseley, Mountain Fiddler, Asheville, North Carolina by Ben Shahn, 1937. Library of Congress. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. The body of a fiddle is made of about seventy wooden components and the bow is wound with horse hair. The Irish Famine of 1845-1851 caused thousands of Irish natives to immigrate to the United States. At this time, many Irish musicians sought employment in minstrel and vaudeville shows to make decent money as fiddlers. There are many styles of Irish fiddle music that vary from county to county; Donegal, Sligo, Galway, Clare, Kerry and Cork to name a few. Generally, most fiddlers play upbeat music you can dance to. Sligo-style fiddler, Michael Coleman, popularized the fiddle in the 1920s with his commercial recordings of lively melodies and bouncy rhythms. Outside of traditional Irish dance music, the fiddle can be heard in New England’s country dance, western swing and upbeat bluegrass music in the upper South. Headline image credit: Violin. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Ten fun facts about the Irish Fiddle appeared first on OUPblog.

Citizenship and community mental health work

My eureka moment with citizenship came one morning during the mid-1990s. The New Haven Mental Health Outreach team that I ran was meeting for rounds. Ed, a peer outreach worker (a person with his own history of mental health problems who’s made progress in his recovery and his now working with others), didn’t look happy. This was surprising, given that two weeks ago he’d been the toast of the team for housing one of the people that some of our office-based colleagues were telling us we’d never be able to reach.

Jim, one of Ed’s clients, was sleeping on a ledge under an I-95 highway bridge when we met him. He had a serious mental illness and alcoholism and had been estranged from his family for many years. He told Ed and the rest of us that he didn’t deserve any help and wanted to be left alone. But Ed was persistent. He built a relationship with Jim, starting small — a sandwich, a cup of coffee, new socks — and eventually got him to see our team psychiatrist and to apply, successfully, for federal disability income. And to top all this off, Ed persuaded Jim to accept housing. The day he moved in, with Ed’s help, was a day of celebration for the outreach team. If we could get Jim housed, we could do anything.

When Ed’s turn came up in rounds that day, he said Jim had told him he wanted to go back to sleeping under the highway bridge. He didn’t know how to manage apartment living, felt out of place around others there, and missed his bridge buddies. He wanted to go back to where he belonged. We came up with a short-term solution for Jim — Ed spent more time with him, showed him how to use the stove, took him over to the local social club for people with mental illnesses, and Jim did pretty well for a while. But for me, Ed’s announcement in outreach rounds was a eureka moment because I realized that while we could do many things for our clients – hook them up with mental health and substance use treatment, help them apply for entitlements, find rental subsidy housing for them, and more — what we couldn’t do was help them become neighbors, community members, and citizens.

Citizenship can be an awfully broad term, but it can also be too narrow. In everyday discourse it often refers to legal citizenship, or to people’s rights, or somewhat less often, to responsibilities such as paying taxes, serving on a jury, and obeying the law. But there’s another kind of citizenship, one that focuses on civic participation and association with others. It seemed that the citizenship our clients with mental illnesses needed, including those who were homeless or had criminal histories, should incorporate all of the above.

Circle by Nemo. CC0 via Pixabay.

Circle by Nemo. CC0 via Pixabay. We define citizenship as the person’s strong connection to the 5 Rs of rights, responsibilities, roles, resources, and relationships that a democratic society offers to its members through public and social institutions and associations, and through free social interactions among its members.

We’ve approached citizenship at both the community level and individual levels. At the community level, we’ve learned how to build connections with neighborhood associations, civic leaders, and the everyday interactions (community gardening, neighborhood clean-ups) — building bridges from community mental health centers to local neighborhoods and City Hall. We connect people with mental illnesses to others in their communities via their passions, whether playing chess or doing crafts, rather than encouraging generic “get-out-into-the-community” activities that just leave people floundering.

At the individual level, we have a “citizens project” involving peer mentor support and practically-oriented classes based on the 5 Rs, followed by community valued role projects such as teaching police cadets how to approach a person on the street who’s homeless, has a mental illness, and fears being locked up — the rejects of society becoming the teachers of the protectors of society. Our randomized study of this intervention showed decreased drug and alcohol use, and increased quality of life and satisfaction with work for those employed, compared to people receiving usual mental health services. The study also showed increased anxiety and depression for the citizenship group when the intervention ended, suggesting perhaps that we need to provide more peer mentor support and next-step help for our citizenship graduates. We’ve developed an individual scale to measure citizenship based on the citizenship ideas and aspirations of people with mental illnesses, others with major life disruptions such as a serious medical illness, and people without such disruptions. This scale is also helping us hone our citizenship support efforts, based on identifying the groups of items that people need the most help with, or the identified strengths they can lead with, or both.

The next step for this work is to make it more available to people with mental illnesses, through use of a just-developed manual that can be used to “replicate” the citizens project, and by taking citizenship to scale through modifying the citizenship project for use in a variety of mental health treatment settings. The “citizenship” term is still fairly new in mental health care, but it hearkens back to a longstanding goal of community mental health treatment, announced in the 1961 report of the Eisenhower Commission on Mental Health: supporting a life in one’s community “in the normal manner” for people with mental illnesses.

The post Citizenship and community mental health work appeared first on OUPblog.

Beyond Budapest: how science built bridges

Fin de siècle Hungary was a progressive country. It had limited sovereignty as part of the Austro-Hungarian dual monarchy but industry, trade, education, and social legislation were rapidly catching up with the Western World. The emancipation of Jews freed tremendous energies and opened the way for ambitious young people to the professions in law, health care, science, and engineering (though not politics, the military, and the judiciary). Excellent secular high schools appeared to challenge the already established denominational high schools; there was a healthy competition and the result were graduates that would become major players in world science and culture. They included seven future Nobel laureates, among them Eugene P. Wigner and Dennis Gabor, and the five so-called Martians of Science, among them John von Neumann and Leo Szilard.

The happy peacetime of fin de siècle Hungary changed drastically after World War I. Firstly, there was the brief, ruthless, Red Dictatorship (March-August 1919), followed by the equally ruthless White Terror (1920-1944). Hungary had the sad record of introducing the first anti-Jewish legislation in post-World War I Europe. The so-called numerous clausus (closed number) law in 1920 severely restricted the number of Jewish students in Hungarian higher education. Toward the end of Nicholas Horthy’s anti-Semitic regime, it became numerus nullus, and hundreds of thousands of Jews were killed in 1944 and 1945. The lucky ones had already left the country. In the 1920s, they mostly left for a democratic Germany. After the Nazi takeover of Germany, they fled to Great Britain and the United States. The exodus of young, ambitious Jews has continued ever since. In fact, nowadays, it is not only a Jewish phenomenon. Economic opportunities in the West and the shortage of democracy in Eastern Europe pull many young people of varying backgrounds to the West.

The Abel-Prize winning mathematician Peter Lax, of New York University, was 15-years old when he left Hungary for the United States with his family in 1941. They were lucky to take the last boat from Lisbon to New York. Until his departure, he was a student of the ‘Minta,’ the Model Gimnázium in Budapest, where before him, among others, the US aerodynamicist Theodore von Kármán, the economist-historian Karl Polanyi, the chemist turned philosopher Michael Polanyi, the UK economists Baron Thomas Balogh and Baron Nicholas Kaldor, and the US nuclear physicist Edward Teller had studied.

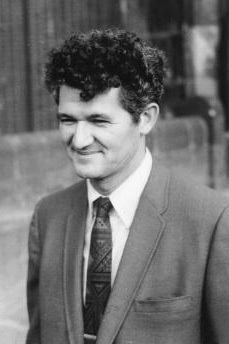

Peter Lax, by Konrad Jacobs. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Peter Lax, by Konrad Jacobs. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Lax had excelled in math in Budapest and his physician father consulted von Neumann as to where his son should continue his education. In New York, Lax attended the Stuyvesant High School, but he did not take math. Instead, he became a member of the math team of Stuyvesant. In the year when Lax was member of the team, Stuyvesant won the national competition in math. The Stuyvesant—now occupying a different campus—has graduated four future Nobel laureates.

The Budapest high schools are notorious for producing world-famous scientists and other contributors to world culture. Don’t be too quick to idealize these schools, however. The “drill-like” atmosphere was not pleasant, even for their best pupils. The lessons started with recitation and the teacher could call upon any pupil at any time, so all were in frightened anticipation. Lax’s experience is unique in that he could compare his experience in the Minta and in the Suyvesant.

Lax was a good student yet his teachers petrified him at the Minta. At the Stuyvesant, Lax felt his teachers were friends. In a conversation with us, Lax admitted that despite the unpleasant “drill-like” atmosphere, Hungarian high schools proved efficient in preparing its pupils for life. The pupils found themselves in a realistic life situation with powerful enemies. They all recognized who their enemy was: the teacher.

Dennis Gabor (1900-1979) attended another high school in Budapest, a generation before Lax. It was the Berzsenyi Gimnázium. This school also produced notable graduates, perhaps more in the humanities and social sciences. Following high-school graduation, Gabor continued in Berlin and trained to become an engineer-physicist to acquire skills and knowledge that would guarantee his employment in Great Britain. In England, he held research and development jobs in industrial laboratories, followed by professorial appointments at Imperial College in London. He invented holography, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1971.

These are just two examples. Both Gabor and Lax demonstrated parallel lives that linked two cities. Budapest, on the one hand, and New York and London, on the other. Budapest ejected them whereas New York and London welcomed them. Thus, science has built bridges, albeit highly asymmetric ones, between Budapest and New York and Budapest and London. Sadly, none of the Hungarian scientists who have won the Nobel Prize went to Stockholm from Budapest to claim it; they went there from other lands. Yet, we are proud of them, and their impact on science in their birth city of Budapest.

Featured image credit: ‘Anonymous’, by Jenny Downing. CC-by-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Beyond Budapest: how science built bridges appeared first on OUPblog.

March 11, 2015

Shooting one’s bolt from North to South

I was twelve years old when I first read Jack London’s novel Martin Eden, and it remained my favorite book for years. Few people I know have heard about it, which is a pity. Jack London was a superb story teller, but his novels belong to what is called politely the history of literature—all or almost all except Martin Eden. Shortly before the end, we are allowed to read Martin’s thoughts: “He had shot his bolt, and shot it hard, and now he was down on his back.” The phrase struck me as wonderfully picturesque, and I never forgot it. I thought about it while writing my previous post, and John Cowan, as I learned from his recent comment, had a similar association. The bolt is indeed “shot,” and it seems that the Anglo-Saxons locked their doors only with the help of a bolt (or scyttel, the ancestor of Modern Engl. shuttle). This may have been the reason they borrowed the dialectal Scandinavian adjective for “crooked” and turned it into kaigjo- “key” (that is, if my reconstruction is right). Perhaps the borrowing coincided with the invention of a more sophisticated key, or they might have observed such an implement in the houses of the Vikings, their uninvited neighbors. By the year 1000, the date of the first attestation of key in English texts, the Vikings were everywhere, especially in the north of the country.

Today I would like to say something about latches in several languages and the role of bolts and thresholds in the myths of medieval England, Scandinavia, and beyond. My story begins with Grendel, the monster conquered by Beowulf. Little is known about Grendel except that he was a cannibal and an enemy of mirth, while the king’s hall was the center of merriment and joy (fun, as we today would say), where, among other things, the retinue listened to songs of exile and of women’s mourning for their husbands. Grendel is said to belong to Cain’s progeny. This Christian allusion must be a late touch, almost a metaphor. Although it is unlikely that the Beowulf poet invented the monster’s name, despite a probable connection between it and some place names, nothing can be said about Grendel’s prehistory. Since he lives with his mother, we only know that the story is an example of the type “The Devil and his dam.” His name, we suppose, reflects his essence.

A bolt of lightning

A bolt of lightning The etymology of Grendel remains controversial. Among the proposed hypotheses several are reasonable, and it is hard to choose the best. I’ll very briefly go over the most plausible ones. The name reminds one of grind. Grendel was perhaps a kind of grinder, though swallowing twelve warriors in one go can hardly be called grinding: “gulper” or “glutton” would fit him better. Then there were Old Icelandic nouns grand “evil” and grindill “storm.” Neither word has cognates in English. Grindill had irresistible appeal to those nineteenth-century scholars who identified all mythological figures with natural forces. To them Grendel was the embodiment of spring floods. Also, the noun grand “sand, bottom of a body of water” has been reconstructed. This word, if it were of any use, would have pointed to Grendel as a water demon, which he certainly was. However, it is strange that, given such an appellation, we do not find any cognate of Grendel outside Old English.

I would not have embarked on this topic but for one more suggestion that seems especially attractive to me and has a direct bearing on the subject at hand. Old Engl. grindel meant “bar, bolt.” Bolts, it will be remembered, are at the center of the present post. Originally, bolt, with a broad spectrum of cognates, meant “arrow” (hence a bolt of lightning), like Old Engl. scyttel, mentioned above. “Peg, bolt for the door” would be easily associated with an outer boundary, and it is characteristic that in Hessen (Germany) grindil ~ grendel means “enclosure.” For comparison: the cognates of Old Saxon fercal “lock, bolt, bar” are Russian porog “threshold” (stress on the second syllable: see more on thresholds in a recent post) and Sanskrit Parjána, the name of the weather god in a Vedic hymn. I believe that Grendel, assuming that this creature has respectable mythological roots, was known at one time as the master of the underworld and that his name meant something like “enclosure for the dead” and “bolt, bar.” If so, it referred to a latch that did not allow the dead to leave his kingdom. In Scandinavian mythology, the reigning divinity of the Underworld was a female goddess called Hel (one l!). This name is related to Engl. hell; its root means “to hide,” as is still obvious in German hehl-. Grendel’s mother is stronger than her son. Originally she did not need offspring, but with time a story of mother and son or husband and wife (“The Devil and his dam”) developed: the terrible deity acquired a male companion.

I find partial confirmation of my belief in the myth of Loki, a Scandinavian demon who, although accepted by the gods as one of their own, ultimately rebelled against them. Stories of his once ruling the underground kingdom have come down to us (both of our greatest medieval authorities—Snorri Sturluson, an Icelander, and Saxo Grammaticus, a Dane, recorded them), and he never lost his ambiguous status of both a monster and a god. If the history of Grendel’s name is a problem, the origin of Loki is a quagmire. At least a dozen etymologies compete for recognition. As usual in such cases, some of them have been refuted, some forgotten, and a few look equally or almost equally good. The almost obvious derivation of Loki from the verb lock or some of its cognates runs into serious difficulties, whose discussion here would take us too far afield.

The god of death Othin on his eight-legged horse.

The god of death Othin on his eight-legged horse. It may perhaps be advisable to choose the following solution. One of the forms that corresponds to Loki is German Loch “hole.” Loki in his most primitive form seems to have been a divinity of the Underworld, like Grendel, as I represented him above, a personified enclosure or grave, or bolt (bar, latch). He did not let his “population” out. Othin, the supreme god of the ancient Scandinavians, was, according to one tale, Loki’s sworn brother, and Othin was certainly a god of death. He killed his victims; Loki kept watch over them. The two had a good deal in common.

It will be remembered that the word deadline is an Americanism, and before it began to refer to the time at which some task has to be finished, it meant a real dead line around a stockade for prisoners, the line they might not cross on the peril of death. I think both Grendel and Loki were such “dead lines” or, more probably, bars (bolts), the earliest “keys” of the Germanic-speaking peoples. As noted, the Russian cognate of the Old Saxon word for “lock, bolt” means “threshold.” The connection is too apparent to need elucidation. We can now wrap up our story of keys, bars, and thresholds. The words for them no longer fill us with horror: a latch is just a latch, and a key is a key. To alleviate our fears, latchkeys were invented. To put the kibosh on the monsters, people opened a café called Loki in Reykjavík and a restaurant in Harvard Square (Cambridge, Massachusetts) that they named Grendel’s Den. The latter is not an underwater establishment, but, to remain true to the spirit of the myth, it has a bar. Pity the demoted gods or rejoice in their downfall.

Image credits: (1) Lightning by Andrei. CC BY 2.0 via svnbg Flickr. (2) Odin. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Shooting one’s bolt from North to South appeared first on OUPblog.

Preparing for the next Ebola

As Ebola recedes from the headlines, amid long awaited declines in incidence in West Africa, a long overdue commitment to developing vaccines and adequate health care infrastructure is underway. The importance of these approaches should not to be minimized. Yet we need to remember that health promotion and protection, as well as social development, ultimately hinge on people, not simply drugs or clinics.

“The people” on whom so much rests, certainly include health care workers, who in the case of Ebola often gave unstintingly, suffered a 55% mortality rate, and were (appropriately) named Time Magazine’s 2014 Persons of the Year. Yet to really be successful in health promotion and disease prevention and control, “the people” also must prominently include community leaders and members, whose deeper engagement, farther into the Ebola outbreak, helped improve outcomes.

In stressing the need for elevating community engagement, we in no way mean to downplay the critical importance of addressing the broader socio-structural factors that create the environments in which deadly diseases can flourish. Yet, we health professionals must, at the same time, reframe our approach to diseases like Ebola, viewing communities as part of the solution, and indeed pivotal to success. Early pictures of outside experts in “space suits,” unceremoniously taking away bodies and spraying residents with chlorine, are seared into our collective memory. So, too, are images like one of a young woman, trying desperately to throw dirt on the rapidly departing, triple wrapped body of her deceased sister, in a final attempt to provide some dignity, some modicum of cultural appropriateness.

There was a better way, and while it was increasingly exhibited in the waning stages of the outbreak, how much better it would have been to follow some simple steps from the beginning, ideally averting such deadly practices as hiding ill family members and unsafe burials.

We created an eight step process to better address disease outbreaks through early and sustained community engagement. These steps include ensuring that outside health care workers familiarize themselves with a community (its customs, beliefs, and informal leaders) before entering; that they enter accompanied by a respected local leader, and with “cultural humility” (showing respect for the community’s knowledge and assets); that they listen and learn, not simply give orders and take unexplained and fear-producing actions. A meeting in the community, called by local leaders and to which outside health workers are invited as guests, is another important step; it allows outsiders to share what they know while promoting reciprocal learning, and establishing trust and respect. Community meetings also provide a good platform for assessing “community readiness” to work with health care workers in identifying aspects of the standard infection prevention and control (IPC) protocol that might be adjusted to improve their cultural congruence, without compromising safety.

Social mobilization being applied to curb Ebola in Sierra Leone. UN Photo/Martine Perret. 22 December 2014. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via United Nations Photo Flickr.

Social mobilization being applied to curb Ebola in Sierra Leone. UN Photo/Martine Perret. 22 December 2014. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via United Nations Photo Flickr. The WHO identified several such modifications with respect to the most dangerous practice: the ritual washing and burying of the newly deceased. Inviting the bereaved to help dig graves of sufficient depth, and lower the coffin/body while wearing protective gloves, respected local beliefs and practices while ensuring safety. In our conversations with residents and health care workers in Sierra Leone and other African nations, we learned of other promising practices, as well as important local assets that could be mobilized to help. A song about Ebola by the popular “Sierra Leone Refugee All Stars,” that played on local radio stations, and short, locally-made films in which “real people” convey accurate information conversationally, were among these assets. From Kenya, we were reminded of the key role local members of Slum/Shack Dwellers International can play in providing detailed information about informal settlements where disease outbreaks too often become epidemics.

The development of a safe, collaborative community-medical IPC protocol, adjusted to include safe modifications based on the “community protocol” (local customs, beliefs, knowledge and practices), may make a substantial difference in community responses and contributions, and save lives. So too can the active engagement of once shunned Ebola survivors, who now are playing a critical educational and supportive role in many communities.

Although rigorous testing of such an approach still is needed, and assessment processes and plans for sustainability must be built into each application, more recent involvement of local leaders and residents, including survivors, suggests the promise of a more community-engaged approach.

Encouraging, too, is the recent commitment of the presidents of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone to reaching “Zero Ebola Infection in 60 Days,” with an operational framework that includes standard infection prevention and control, social mobilization, and community engagement among its key elements. Although we applaud these efforts, we suggest that community engagement and social mobilization must be a core part of, and not a supplement to, the development and deployment of a sound IPC. Such engagement may have helped prevent recent rumors that the spraying/disinfecting of schools was actually spreading Ebola — rumors which led to the burning of a vehicle and Medecins Sans Frontieres office in Guinea in mid-February. Now is the time to fully develop, test, deploy, and sustain a more robust community-engaged approach to IPC. Doing so may help achieve the ambitious goal of Zero Ebola Infection in 60 Days. It will also help build capacity and readiness before the next Ebola, or other serious infectious disease, has a chance to take hold.

The post Preparing for the next Ebola appeared first on OUPblog.

Losing control: radical reform of anti-terror laws

The violent progress of the Islamic State (IS) through towns and villages in Iraq has been swift, particularly when aided by foreign fighters from Britain. IS has now taken control of large swathes of Iraq and there are growing concerns amongst senior security officials that the number of British men and women leaving their country to support and fight alongside the extremist group is rising. Today marks ten years since the introduction of the Prevention of Terrorism Act 2005–but how effective has terrorist legislation been in tackling terrorism?

The exportation of British-born violent jihadists is nothing new, but the call to arms in Iraq this time around has been amplified by a slick online recruitment campaign, urging Muslims from all over the world to join their fight and post messages of support for IS.

In response to increased threats from IS, the British government has introduced a range of powers that form the basis of the new Counter-Terrorism and Security Bill, which seeks to prevent British citizens from engaging in terrorist activity.

Over the course of many years, the British government has gained substantial legislative experience in tackling different forms of terrorism, introducing new powers and provisions. For example, in order to respond to terrorist threats relating to the long and violent struggle in Northern Ireland, legislators created five separate pieces of legislation. This included the Prevention of Violence (Temporary Provisions) Act of 1913 and the Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) Acts of 1974, 1976, 1984, and 1989.

While this was a swift response to terrorist threats at the time of their enactment–arming law enforcement and the military with greater provisions to tackle dissidents and paramilitaries–the post-9/11 genre of international terrorism represented a very different threat to national security and public safety. As terrorist threats from Northern Ireland waned, the world bore witness to the full extent of the threats arising from the indiscriminate mass-casualty attacks of al-Qaeda.

Because the anti-terror measures designed to pursue domestic terrorists in Northern Ireland were made up of a collection of temporary provisions, the British government realised that a changing security landscape required updated, permanent measures.

Prior to 9/11, the Terrorism Act of 2000 had already been created in the wake of the largest overhaul of terrorism legislation in British legal history. While it still remains the primary piece of terrorism legislation in operation today, new pieces of legislation were also introduced in direct response to 9/11 and the subsequent backlash against terrorism overseas.

These new pieces of legislation included the Anti-Terrorism, Crime, and Security Act of 2001, which was designed to cut off terrorist funding and protect the aviation and nuclear industry, as well as the Prevention of Terrorism Act of 2005, which introduced Control Orders to monitor and restrict the movements of suspected terrorists.

After the London bombings of 2005, legislators introduced the Terrorism Act of 2006, responding to the growing numbers of British terrorist recruits. This piece of legislation extended police powers by creating nine new terrorism-related offenses, significantly lowering the threshold for individuals to be arrested.

Soon, the Counter-Terrorism Act of 2008 was added to this expanding legal framework, tightening controls on terrorist finances and fund-raising, in addition to introducing measures for questioning of terrorist suspects charged with specific terrorism-related offenses.

During December 2011, the Terrorism Prevention and Investigations Measures Act of 2011 introduced the new system of Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures (TPIMs). These measures replaced the controversial Control Orders and were designed to better protect the public from deported foreign nationals and a small number of people who posed a real terrorist threat but could not be prosecuted.

The latest addition to the anti-terror legal framework is the new Counter-Terrorism Security Bill, which provides the government with the power to seize passports, bars the return of foreign fighters, and re-introduces compulsory relocation powers under the Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures Act of 2011, marking the return of old measures to tackle a contemporary threat.

Evidently, the post-9/11 pace of legal change regarding anti-terror laws has been relentless and unprecedented. The five previous anti-terror acts, which established temporary provisions, had been brought to the statue book over a period of eighty years; the government’s legislative response to the mass-casualty threats of al-Qaeda and IS, on the other hand, has introduced seven pieces of legislation over the course of just fourteen years.

People in positions of authority have come to learn that political stakes are high in the aftermath of terrorist attacks. Legislators, afraid of being perceived as lenient or indifferent, often grant broader powers to the executive branch without thorough debate. New special provisions intended to be temporary turn out to be permanent.

This haphazard approach to tackling contemporary terrorism cannot continue. Surely, now is the time to introduce a Consolidation Act, a single statute into which all counter-terrorism legislation can be placed and codified? It would be for the benefit of all if counter-terrorism law set the example for the codification of British criminal and regulatory law.

No doubt, the hope we all share is that exceptional powers–which almost all counter-terrorism laws provide–will cease to be necessary. But it is important that we recognise an uncomfortable truth: the terrorist attacks we have seen in Britain are not simply random plots by disparate and fragmented groups. The majority of the attacks, successful or otherwise, have taken place because terrorists have a clear determination to mount attacks in an attempt to destroy our free and democratic way of life. This remains the case today and there is no sign of it diminishing.

Image Credit: “Tribute in Light” by Tim Drivas. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Losing control: radical reform of anti-terror laws appeared first on OUPblog.

How to make regulations a common good?

Differences in regulatory norms are increasingly seen as the key barriers to the growth of regional and global markets, and regulatory disputes make up some of the most contentious issues in world politics. Negotiations among the most developed economies of the world about regulatory synchronization have made little progress in the last decade, and nearly all harmonization attempts failed when they had involved economies at lower levels of development.

In a world in which almost all multilateral efforts at creating common market rules fail, and a regional agreement on common rules in a single policy area is described as a major breakthrough, the experience of the smooth transfer of nearly 80 thousand pages of regulations to the Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries in 33 policy areas offers some interesting lessons.

Explanations for this exceptional success have relied on arguments based on the skillful use of conditionality linked to EU membership. Citizens in the Eastern peripheries of Europe, as we have seen in several cases, were ready to make considerable sacrifices for the promise of membership in the richest club of the globe. Brussels, indeed, had exceptional leverage, when it has negotiated with countries waiting outside the gates of the EU. Ten years after the CEE countries were invited to join the European Union, the power of such explanations necessarily declines. If it is about honoring EU regulations, the not-so-new EU members from Central and Eastern Europe perform at least as well as the most developed core economies in Europe.

The high sustainability of the common market rules in these countries calls attention to a lesser-known aspect of the regulatory integration of the CEE countries. The EU differed from other regions of the world by its encompassing experimentations with strategies to change local conditions and increase the capacity of domestic actors to benefit from taking the common rules of the EU market. To do so, the EU has created regional capacities to anticipate and alleviate the potential negative developmental consequences of transferring to lesser-developed countries the market rules of the most developed European countries.

“Citizens in the Eastern peripheries of Europe, as we have seen in several cases, were ready to make considerable sacrifices for the promise of membership in the richest club of the globe.”

Instead of using solely the incentives linked to membership, the Commission involved the governments of the applicant countries in a nearly decade-long joint problem solving in more than thirty different policy areas. Special attention was devoted in these processes to building elementary economic state capacities in the CEE countries. State restructuring was growingly embedded by the Commission in twinning programs, a transnational network of technical assistance mobilizing thousands of public and private actors in the old EU member states.

Besides creating domestic capacities to implement the European policies and rules, the Commission also tried to strengthen (or in many cases, to create) basic planning capacities, abilities to foresee and manage potential negative development externalities of integration. The EU’s assistance programs that have transferred in the first wave of Eastern enlargement 28 billion Euros to the CEE countries, had been linked to the problems detected by domestic developmental plans, several times done in collaboration between domestic and external actors.

While the direct beneficiaries of these strategies were in the CEE economies, the goal of these institutional experimentations was primarily to defend the interests of the EU insiders. The old member states were at least as afraid that the applicant countries will not be able or willing to play by the common market rules than from the success of imposing tens of thousand of pages of regulations on the CEE countries. In the first case, fearing the new members deviating from EU rules, the primary fear was that the new members will out-price compliant firms in the old member states, provoke a race to the bottom and, in the end, might induce the disintegration of the common market. In the latter, the case of successful imposition, the fear was that the rules that have worked in the most developed economies might have unpredictable negative developmental effects in the less developed economies. The old member states might not be able externalize the costs of political and/or economic crises and the costs of enlarging the common market might way surpass its gains.

More generally, these programs were based on the recognition that strategies that focus on the short term interests of the more powerful actors alone can have welfare effects that are inferior to solutions based on collaborative exploration of opportunities to reduce in time the potential negative developmental consequences of regulatory integration.

On a much smaller scale, there are several similar experimentations in other regions of the world. Regional developmental banks in several continents experiment with solutions linking regulatory integration with the production of regional public goods. In specific transnational or global policy fields we can witness the coming about of experimental forms of governing rule harmonization involving a big variety of transnational private and public actors. Street level bureaucrats in several evolving market economies are given discretion to involve diverse domestic actors and multinational firms in creating local settlements that could make implementing transnational rules rewarding to the involved actors.

While these strategies differ dramatically in their scope, they have in common the goal to create sustainable common regulations by way of making them a common good. This implies a joint search for ways to get in synch the requirements of implementing uniform transnational rules with the interests and capacities of domestic actors operating in multiple diverse local institutional contexts. There are no universal recipes, the policies that work might differ across countries, sectors and policy areas. The governance of such regulatory integration thus presupposes in most of the cases the simultaneous upgrading of the coordinating and policy making capacities of domestic and transnational institutions.

Featured image credit: Dead Tree Pattern, by Rolf Brecher. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr

The post How to make regulations a common good? appeared first on OUPblog.

March 10, 2015

Visualizing same-sex desire

History is surfeited with examples of the interactions between society and individual sexuality. Same-sex desire in particular has been, up until the present moment, a topic largely shrouded in shame, secrecy, and silence. As a result, it is often visualized through the image of ‘the closet,’ conveying notions of entrapment, protection, and potential liberation. Dominic Janes, author of Picturing the Closet: Male Secrecy and Homosexual Visibility in Britain, recently sat down with us to talk about the visualization of same-sex desire in eighteenth-century Britain to the present.

How can you picture ‘the closet?’ Doesn’t it intend to keep same-sex desire invisible?

But the point is that it often fails to do just that. This is what Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick attacked in her book, Epistemology of the Closet (1990), through conceptualizing the closet as ‘the defining structure for gay oppression in this century.’ The closet was a space of darkness and fear precisely because of its fragility. Moreover, she argued, the role of the ‘camply’ effeminate man was deployed in order to create a spectacle of the closet as an open secret. These issues are not peripheral to the struggle for individual self-determination and self-expression over the last several decades. As the preface to the second (2008) edition of her book made clear, Sedgwick had not merely been exploring the category of the homosexual as a homophobic creation, but had been doing so at a time when the experience of AIDS had led to a massive political backlash against lesbian and gay liberation in the United States and around the world. Something that was particularly dangerous about the closet at this time was that it implied that only a small proportion of the population possessed problematic forms of sexual desire since only they, the flamboyant few, were clearly visible.

How can you picture ‘the closet’ prior to the twentieth century, when the term first came into use?

The force of Sedgwick’s arguments presented clear evidence for the phenomenon of the closet before that particular term came into use. It might be best to say that there is a history of closet-like formations that relate to the fear or reality of being revealed as say, a sodomite in the nineteenth century, a homosexual in the early twentieth century, or as gay in the decades thereafter. This means you can ask to extent people thought they could identify an ‘obvious’ sodomite before the construction of the homosexual as a type of person during the latter part of the nineteenth century. Moreover, we can ask what roles secrecy and denial played in relation to the visual expression of same-sex desire before the term ‘the closet’ came into widespread use in the latter part of the twentieth century.

For example?

The cover of Picturing the Closet uses part of a fascinating print, ‘How d’Ye Like Me,’ which was published in London by Carington Bowles on 19 November 1772. The classical discourse of the hermaphrodite was referenced in this work by depicting this simpering figure with a vestigial sword and a prominent vulva-like crease where his penis ought to be. This figure is a ‘macaroni,’ a forerunner of the dandies of the Regency associated with effete Continental tastes (such as for Italian food) that had supposedly been picked up on the Grand Tour. Those who argue that it was only through the trials of Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) that dandified behaviour became firmly associated with sodomy would suggest that earlier effeminacy debates were all about gender rather than sexual tastes. But in fact this print was published in the wake of a major sodomy scandal concerning Captain Robert Jones, who was a fashionable figure in London society. The cover of the book suggests that we need to look at images such as this print again and explore a longer history that reflects the social legibility of transgressive sexual desires.

You’ve emphasized the importance of looking at visual culture since the eighteenth century. Does this topic still matter today?

While gay and lesbian rights are barely entrenched in some parts of the world, there is a mood of justified satisfaction in some countries, including the United Kingdom, where same-sex marriage has been signed into law. But I am not convinced that we have, in any sense, reached the sexuality equivalent of Francis Fukyama’s The End of History and the Last Man (1992). If the closet was never a single construction but evolved to contain new sexual secrets, it is hardly likely to disappear for good in the age of paedophile scandal. In Britain, the former TV presenter Jimmy Saville (1926-2011) has become the media face of sexual perversion in a way that directly echoes the earlier spectacularisation of various ‘effeminate’ men as sexual perverts. ‘Coming out’ as gay or queer as a normative process may not, in fact, spell the end of a cultural structure that seeks to focus on coded spectacle. It may be that homosexuality as the secret of the twentieth-century closet was simply a phase in the ongoing life of a much more deep-rooted cultural construction.

What led you to write about this subject?

In 2009, I published Victorian Reformation: The Fight over Idolatry in the Church of England, 1840-1860 with OUP. In that study, I focused on disputes over elaborate Catholic rituals and argued that the reinterpretation of such religiosity by Protestant opponents as a site of Gothic excitement led to the production of texts (such as novels and newspapers) that were sold as commodities. In this way, the challenging, bodily ‘primitiveness’ of medieval Catholic forms of ritual and material culture was uneasily incorporated into the world of Victorian textuality and capitalism. It became clear to me that sodomy and effeminacy were entwined as themes that underlay attacks on various aspects of Victorian Catholicism. I then wondered what led Oscar Wilde’s satanic creation, Dorian Gray, to collect exquisitely embroidered ecclesiastical vestments. This led me to a British Academy Mid-Career Fellowship focused on exploring the subject of queer visibility and invisibility in what turned out to be a very long nineteenth century.

Image Credit: “Union Jack at Harrods” by Cassia Noelle. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Visualizing same-sex desire appeared first on OUPblog.

Thomas B. Reed: the wittiest Speaker of all

Speaker of the House John Boehner is learning the enduring truth of Lyndon Johnson’s famous distinction between a cactus and a caucus. In a caucus, said LBJ, all the pricks are on the inside. Presumably Speaker Boehner seldom thinks about his Republican predecessors as leaders of the House. Boehner might want to reflect about one former GOP Speaker who was both witty and effective. Thomas B. Reed, who was a Republican Speaker from 1889 to 1891, and again from 1895 to 1899, set a high standard for wit and repartee in debate. A long-time House member from Maine, Reed was a large man at 6-foot 3-inches tall and close to 300 pounds. When a questioner asked him how much he weighed, he responded: “No gentleman ever weighed over two hundred pounds.”

His quick responses in debate became legend. He said the Senate was “a place where good Representatives went when they died.” Of the religious sentiments of his colleagues, he observed: “One, with God, is always a majority, but many a martyr has been burned at the stake while the votes were being counted.” And, of course, when a Democratic member proclaimed, following the Whig leader Henry Clay, that he would rather be right than be president, Reed replied that “the gentleman need not be disturbed — he will never be either.”

Thomas Brackett Reed. Public domain via the Library of Congress.

Thomas Brackett Reed. Public domain via the Library of Congress. Assuming the speakership in late 1889, Reed confronted a House paralyzed by the tactics of the opposition Democrats who refused to answer to their names in the roll call, thereby denying Republicans the quorum they required to do business and then, in the absence of such a quorum, insisting upon adjournment. As the party of state rights, limited government, and racism in the South in that distant era, the Democrats sought to hamstring the Republicans by every means possible. With only a small working majority about six seats at best, the Republicans seemed destined for futility. In January 1890, when the Democrats shouted “no quorum,” Reed directed the clerks to record the names of those members who were present but refusing to vote. When an angry Democrat protested, Reed said: “The Chair is making a statement of fact that the gentleman from Kentucky is present. Does he deny it?”

With control of the rules and House procedures from then onward, Reed pushed through a sweeping program of legislation on the tariff, antitrust, and the currency that reflected the economic nationalism that marked the GOP before 1900. “The danger in a free country is not that power will be exercised too freely, but that it will be exercised too sparingly,” Reed contended. The House has never returned to the days of the disappearing quorum.

For Reed, the heady days of his first speakership represented the high point of his political career. He had hopes to be the Republican nominee for president in 1896, but his political base in Maine was too narrow to give him a real chance against the more popular William McKinley. Reed observed bitterly, as would many aspirants who followed him, that the party’s national convention “could do worse” than nominate himself “and probably will.” When the Republicans regained control of the House in 1894, Reed was once again Speaker, but he was out of step with the overseas expansionist policies of the McKinley administration. Contemptuous of the president, whom he thought his intellectual inferior, Reed resigned as Speaker in 1899, left the House, and practiced law until his death in 1902. He was already a forgotten figure who had outlived his fame.

Reed’s turbulent career looks back to an age when Republicans still believed in the precept that no single individual was bigger than the party itself. Strict party discipline enabled Reed to keep his members in line, do away with the vanishing quorum, and conduct the legislative business of the country in an orderly and constructive manner. If his skills now seem something out of a quaint period of the nation’s past, Reed also stand as a lesson about what a constructive political leader can do to advance the national interest with skill and determination. John Boehner is no Tom Reed and his caucus is certainly not composed of the kind of Republicans who followed Reed into power in 1889-1890. Whether the nation is better for the changes that have overtaken the House and made Speaker Boehner’s leadership task so difficult would be a topic worth a serious debate, and one which has enduring relevance.

Featured image: United States Capitol, Washington, D.C., east front elevation. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Thomas B. Reed: the wittiest Speaker of all appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers