Oxford University Press's Blog, page 690

March 10, 2015

Threats, harassment, and murder: being an abortion provider is a dangerous job

Twenty-two years ago today, Dr. David Gunn was shot and killed outside the medical facility where he worked. This was no ordinary murder, though; Dr. Gunn was assassinated because of his profession.

Dr. Gunn was an OB/GYN who provided abortion services. He was murdered by an anti-abortion extremist who had been protesting outside the Pensacola, Florida abortion clinic where he worked. Michael Griffin, now serving a life sentence in prison for the murder, spent the morning of the murder praying among other protesters. When Dr. Gunn arrived at the clinic that morning and got out of his car, Griffin yelled, “Don’t kill any more babies” and shot him three times in the back, killing him.

Dr. Gunn’s murder was the first of what is now a list of eight targeted murders of abortion providers in this country. Dr. George Tiller was the most recent murder victim. He was shot in his church foyer in Wichita, Kansas on 31 May 2009. In between, two other doctors (John Britton and Barnett Slepian) have been killed, along with a volunteer escort (James Barrett), two receptionists (Shannon Lowney and Leanne Nichols), and a security guard (Robert Sanderson).

All were killed for the same reason — they helped provide women with the safe, legal abortions.

Abortion providers are seriously affected by the violence of the past. Everyday incidents of harassment that they deal with are so threatening and terrorizing precisely because they conjure the murders and violence of their colleagues. And for women who need to access abortion services, this violence and harassment is another contributing factor to the reduction in abortions taking place in the United States.

In memory of these eight fallen abortion providers, today is National Abortion Provider Appreciation Day in the United States. While the day is intended to honor those providers who were murdered by showing appreciation for those currently working, it is also a timely occasion to look at abortion access. We often hear about new abortion restrictions that are making abortions harder to obtain in certain parts of the country, but the day-to-day experiences of abortion providers are largely left out of the national dialogue.

“Abortion kills children” by University of Toronto Students for Life. CC BY-SA 2.0 via .

“Abortion kills children” by University of Toronto Students for Life. CC BY-SA 2.0 via . Providers endure all sorts of targeted and individualized harassment. Before Dr. Gunn was murdered, he was subject to other kinds of targeted harassment — being followed at night, receiving hate mail and death threats, being yelled at and called a murderer. This type of targeted harassment of abortion providers continues to this day and is a constant threat to women’s access to abortion.

Over the past four years, we have interviewed almost ninety providers across the country about their experiences with this kind of targeting by anti-abortion extremists. One common theme among our interviews is that providers are acutely aware that they work in a profession where their colleagues have been murdered for doing the same job they do. For instance, after local protesters recently began picketing one Midwest doctor at home, he took precautions specifically because of the 1998 murder of Dr. Barnett Slepian in Buffalo. (Dr. Slepian was shot by a sniper through his kitchen window on a Friday night.) With Dr. Slepian’s murder in mind, this Midwest doctor told us, “When I’m in the kitchen and it’s dark outside and I’m standing in front of my kitchen window, more than just a couple of times I’m thinking ‘is there going to be a rifle shot coming through this window?’ And I never used to think that. That was the furthest from my mind until these protests started.”

Dr. Tiller’s murder also weighs heavily on this provider, especially since this doctor has also been protested at his church. “George Tiller was supposed to be safe in his church. You just never know. Some of the folks out there are just really insane, and the world is so black and white to them.”

The Midwest doctor is not alone in connecting his experiences with harassment to the past murders. Many providers often speak about the ways that their memories of these past murders continue to affect them. Another doctor told us that he bought a house in a private location because he likes to play piano at night and doesn’t want “someone to blow me away like Dr. Slepian,” or “shoot me in the back, while I am playing piano.” Yet another doctor said that to her, Dr. Tiller’s murder was “the most frightening because of where it happened — not on clinic grounds. Which is really what concerns me more than here at the clinic — everywhere else I’m circulating.”

So today, when you are thinking about those who work for clinics that provide abortions, remember that they are not only providing necessarily medical services, but also for risking their safety in the process.

Heading image: A pro-life group protesting at Supreme Court in Washington, DC, by SchuminWeb. CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Threats, harassment, and murder: being an abortion provider is a dangerous job appeared first on OUPblog.

Beethoven and the Revolution of 1830

That Beethoven welcomed the French Revolution and admired Napoleon, its most flamboyant product, is common knowledge. So is the story of his outrage at the news that his hero, in flagrant disregard of liberté, égalité, fraternité, had himself crowned emperor: striking the dedication to Napoleon of his “Eroica” symphony, he addressed it instead “to the memory of a great man.” Less well known is how the memory of another great man, Beethoven himself, figured in the lead-up to the second French Revolution – the one that toppled the Restoration Monarchy in a mere three days of July 1830, and that Delacroix commemorated in his provocative “Liberty Leading the People.” That story, too, bears telling, not least because it encapsulates one of the great revolutionary shifts in the history of Western music.

Beethoven died a celebrity in his homeland, in 1827, but virtually unknown in France, where fledgling regimes following 1789 clung all the more tenaciously to Classicism in the arts as innovative currents challenged it more radically elsewhere. Romanticism, as it came to be called, erupted belatedly in France in the 1820s, fed by growing discontent under the Restoration Monarchy established after Waterloo. In the fall of 1827 Victor Hugo’s iconoclastic Preface to Cromwell served as a pivotal rallying call, together with eye-opening performances of Shakespeare. When the newly formed Société des Concerts du Conservatoire orchestra began to introduce Beethoven to Paris, in March 1828, the audience was primed: the “Eroica” Symphony, plainly chosen for its Napoleonic associations, opened the series to electrifying success. It was the Fifth Symphony, to be sure, that soon became the favorite, not for its now-iconic first movement, but for the apotheosis Finale, heard as a Napoleonic triumphal march.

Berlioz remains our best witness to what he called the “thunderbolt” revelation of Beethoven in Paris. For him, the experience was transformational. It upset in one blow the grounding assumption of his Conservatoire training, namely that instrumental music was inferior to dramatic, and that Haydn, in any case, had taken the symphony as far as it could go. Within two years, Berlioz had written a symphony of his own, the first of four within a decade. Composed in the early months of 1830 as Victor Hugo was leading the Romantics to victory in the Classical bastion of the Comédie française, the Symphonie Fantastique premiered in December 1830, closing out the tumultuous year.

The entire decade surrounding 1830 was in fact tumultuous, especially for music. At the Conservatoire, the Beethoven concerts did more than introduce a new composer: they upset an entire world view. They brought into existence, among other things, the first great modern orchestra, formed of virtuoso performers led by a standing conductor, the orchestra that gave Beethoven’s symphonies their first world-class performances. Those symphonies, in turn, prompted a new kind of listening and a new kind of writing about music. As challenging for audiences of the time as contemporary music can be today, they needed the guidance of critics who wrote not as professional writers who happened to like music (as was the Classical way) but as professional musicians who – like Berlioz and Schumann – were equally skilled as writers. Not by accident did the same decade see the emergence of the first successful French music journals, and of a canon in music equivalent to that of the art in the Louvre. Not by accident did it see a surge in status, in France, for musicians and music itself. But if Beethoven revolutionized music in France, France returned the favor. It was in Paris, then the center of Western culture, that Beethoven acceded to the world stage. It was in French writings, notably those of Berlioz, that the world beyond Germany learned to revere Beethoven as the supreme musical genius who embodied all that was best in the Revolutionary heritage.

Headline Image: Napoleon’s coronation by Jacques-Louis David. Louvre Museum. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Beethoven and the Revolution of 1830 appeared first on OUPblog.

March 9, 2015

Bizarre elements: a timeline

The periodic table has experienced many revisions over time as new elements have been discovered and the methods of organizing them have been solidified. Sometimes when scientists tried to fill in gaps where missing elements were predicted to reside in the periodic table, or when they made even the smallest of errors in their experiments, they came up with discoveries—often fabricated or misconstrued—that are so bizarre they could have never actually found a home in our current version of the periodic table.

In The Lost Elements: The Periodic Table’s Shadow Side, Marco Fontani, Mariagrazia Costa, and Mary Virginia Orna share many tales of scientists who introduced these bizarre elements to the scientific community. What follows are the stories of some of these elements.

Image Credit: “Autunite.” Photo by Tjflex2. CC by NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Bizarre elements: a timeline appeared first on OUPblog.

The two faces of Leo Tolstoy

Imagine that your local pub had a weekly, book themed quiz, consisting of questions like this:

‘Which writer concerned himself with religious toleration, explored vegetarianism, was fascinated (and sometimes repelled by) sexuality, and fretted over widening social inequalities, experienced urban poverty first hand while at the same time understanding the causes of man made famine?’

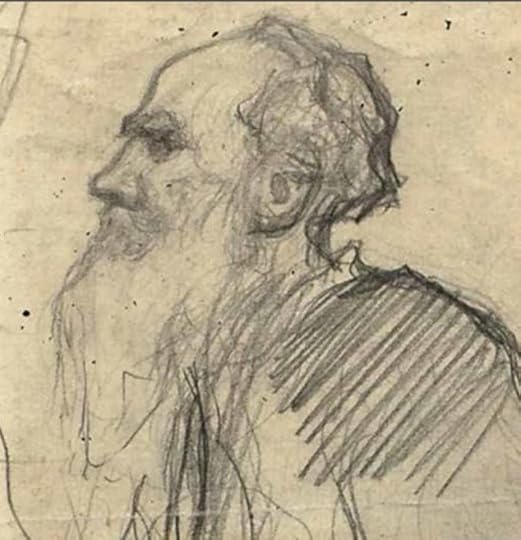

Would you be buying the drinks that night, or going home penniless? To be fair, it’s a difficult question, and the answer — Tolstoy — might not come immediately to mind. Yet he does tick all these boxes, even though we tend to think of him first as the definitive Russian nineteenth-century realist and a great sage of timeless values. Tolstoy’s death in 1910 made front pages news across the world because of his moral authority rather than literary genius. (The final chapter of his life, cloaked in family drama, also made a gripping film — The Last Station in which Christopher Plummer incarnates Tolstoy right down to the tip of his — very prominent — nose). Yet looking at a contemporary pencil portrait gives a glimpse of the complexity of the man and, yes, his brand and image:

Pencil portrait of Tolstoy by Russian painter Leonid Pasternak. Courtesy of Nicolas Pasternak Slater. Used with permission.

Pencil portrait of Tolstoy by Russian painter Leonid Pasternak. Courtesy of Nicolas Pasternak Slater. Used with permission. This sketch of the older Tolstoy — Tolstoy as he was when he wrote the Death of Ivan Ilyich and the Purloined Coupon — is the work of Leonid Pasternak, father of the poet and novelist Boris Pasternak, and grandfather of Nicolas Pasternak Slater who worked with me on the new Oxford World’s Classics edition of Tolstoy’s later works. Leonid Pasternak, a marvelous colorist in the Impressionist manner, was also a gifted illustrator of fiction, which earned him a medal at the World Fair in Paris (1900). He created haunting illustrations for Tolstoy’s Resurrection (1892). His style combines a wash of gray pencil that is softly textured, and sharply drawn facial features, especially brooding eyes.

This sketch from the family collection is unpublished, and it is generous of Nicolas to share a striking, unknown image. In profile he looks grand, focused to the outer world without worldly vanity. His stillness has hidden energy (those cross-hatchings seem like coiled springs read to pop). Tolstoy in old age was small of stature, as many visitors and acquaintances noted with surprise. But his presence here seems massive. Broad-shouldered, his hands tucked into the sides of his peasant blouse; if you look at the torso then you think this is the Tolstoy who boasted to Gorky, the real son of a real peasant, that ‘I am more of a peasant than you, and can feel things the way peasants do better than you can!’ But if you concentrate on the head, the brow slightly furrowed in thought, it seems worthy of a classical bust. The look is more Aristotle or Epicurus, or any ancient philosopher, than it is the Russian mouzhik or peasant male, and somehow Pasternak caught the two elements Tolstoy tried to fuse in his personality.

From a literary point of view, perhaps we might compare Tolstoy to one of the great Victorians: a Russian George Eliot in his moral compass and conjuring of village life, a Russian Trollope in his understanding of hierarchies and institutions. But labels can’t really contain him. In many ways Tolstoy is timeless, like Homer, due to his ability to capture the breadth of human variety. He is timeless in the sense of belonging to all times. Yet in the portrait, and in his later work, I recognize a completely timely figure. We are in touch with him not only because put his finger on so much about living. He speaks to us because he fused a transcendent view with a grasp of the realities of nineteenth society, political economy, and the law that remain with us in some degree. Credit crunch? The schoolboy who forges the coupon is hardly a Wall Street insider-trader. Yet in a world of credit everything and everyone turn out to be connected. Moral discredit could be said to be a derivative of minor fraud.

Lord Skidelsky, the economic historian and biographer of Keynes and his son Edward, recently published an essay with the title How Much is Enough?: Money and the Good Life. That very question in relation to money and possession permeates Ivan Ilyich and Tolstoy’s other short stories. In these parables Tolstoy implies answers by creating virtuous characters. They don’t live in the real world — their economic circumstance and outlook belong to a vision of an early, a historical Christianity, and they are to be contemplated like saints or icons. In his true fictions, working out the answer to the question, ‘how much is enough?’ can be a matter of trial and error in which the margin for error is very slender. The difference between a healthy capitalist appetite and greed isn’t clear-cut. After all, it’s not obvious that Vasily, the merchant in ‘Master and Workman’ is being punished, is it? But Tolstoy seems to suggest that he, and Ivan Ilyich, have been dulled by their wants into being less than alert about the dangers of circumstance. Memento mori: the stories remind that a good life might be measured by a good death, which involves a moral reckoning and not an actual balance sheet.

Tolstoy the ‘wannabe’ peasant, as portrayed in the Pasternak pencil portrait, has turned his back on a material life. His genius at contemplating human beings in the round as biological, psychological, spiritual, individual, familial, social creatures is well appreciated. But it’s easy to forget – and the point really came home to me as I worked on the Ivan Ilyich collection — what a great modern he is and how strongly he reflects fin-de-siècle anxieties. Tolstoy is no less a student of decadence, sexual obsession, stifling bourgeois convention, environmental degradation than an Ibsen or Maeterlinck or, for that matter, Beckett. It’s not for nothing that Gabriel Josipovici, one of the great advocates as fiction-writer and critic of European modernism, identifies The Death of Ivan Ilyich as one of the ten greatest novellas ever published. He puts him in the company of authors great fathomers of the existential puzzle like Melville and Kafka, Mann — yes, we can see that — and, very discerningly, playful ‘meta’ authors such as Robert Pinget (Passacaglia) and George Perec (Un Cabinet d’Amateur). Tolstoy is so readable and so clever at quickening and slowing the reader’s own pulse (are there better page turners than Master and Worker? could any work go more deliberately than The Death of Ivan Ilyich? — that we can forget that like the cutting edge modernists he recreates forms of storytelling to delve into consciousness. He has everything — the real and traditional, the modern and even the post-modern. That adds up to the timeless, I think.

The post The two faces of Leo Tolstoy appeared first on OUPblog.

Racial terror and the echoes of American lynchings

In February, the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) in Montgomery Alabama released a report, Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror. In researching for the report, EJI examined the practice of lynching in twelve southern states between Reconstruction and 1950. The report’s conclusions and recommendations provide important lessons about the past, present, and future of society.

Among the findings, EJI counted 700 more lynchings than had previously been reported for a total of 3959 racial terror lynchings of African Americans between 1877 and 1950 in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia. Many of the victims of terror lynchings were killed for small social transgressions or for demanding basic rights, as perpetrators often used lynching to try to control African-American communities through fear.

The revelations in the report do more than document the past; they critique our modern failures. For example, the report notes that many southern communities have erected monuments to memorialize the Civil War and the Confederacy, while at the same time “[t]here are very few monuments or memorials that address the history and legacy of lynching in particular or the struggle for racial equality more generally.” Thus, EJI and its Executive Director Bryan Stevenson are striving to raise funds to erect memorials and markers at the sites of past lynchings.

To understand the modern significance of the report, one need only look to the deaths of Trayvon Martin in February 2012 in Sanford, Florida, of Eric Garner in July 2014 in Staten Island, New York, and of Michael Brown in August 2014 in Ferguson, Missouri. The movements around those killings mourned the men and also implored society to understand the past’s role in the acts of the present. We only can begin to comprehend these and other tragedies by remembering the racial past that laid the foundation for today’s United States.

Lynchings’ legacy remains connected to our modern legal system in many ways. As lynchings declined in the early 1900s and criminal laws that overtly discriminated against African-Americans were gradually changed, racial prejudice continued to infect the legal system.

The practice of using violence to enforce racial oppression became more reliant on using the legal system as a means of racial oppression, including through the use of capital punishment and discriminatory jury selection systems. Thus, by the 1930s as lynchings became limited to a few per year, within the court system two-thirds of all executions were of black defendants. Even though most northern states had eliminated the spectacle of public executions by the middle of the nineteenth century, some southern states retained public hangings in an obvious nod to the practice of lynching. For example, Kentucky had abolished public executions as early as 1880 but brought back public hanging forty years later as an option for rape and attempted rape crimes. Further, just as the EJI’s research revealed that lynchings often were concentrated in certain counties, the death penalty is similarly used at a higher rate in the South and in only a small percentage of counties in the country.

“What is Past is Prologue” statue, Washington, D.C. Photograph by Mike Peel (www.mikepeel.net). CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“What is Past is Prologue” statue, Washington, D.C. Photograph by Mike Peel (www.mikepeel.net). CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Today, US courts have failed too often to acknowledge the history of racial violence. In 1987, the Supreme Court considered the case of Warren McCleskey — a black man who had been sentenced to death for killing a white police officer. McCleskey’s lawyers presented the courts with statistical evidence that race still infected the death sentencing process. In particular, a defendant who was charged with killing a white person was around twice as likely to be sentenced to death as someone who killed an African-American. The US Supreme Court in a 5-4 decision in McCleskey v. Kemp assumed that the statistical findings of racial bias were correct, but it held that McCleskey’s death sentence did not violate the Eighth Amendment or the Fourteenth Amendment of the US Constitution.

Justice Lewis Powell, who wrote the McCleskey majority opinion and who would later regret his decision in the case, believed that the racial discrimination of 1987 significantly differed from the discrimination and the racial violence of the past. While 1980s America did not look like 1880s America, they were still connected. Warren McCleskey himself would have recognized that connection, as he grew up in a town where blacks could not go to school with whites and in a state with a flag that incorporated the Confederate battle flag.

Only thirty years before Warren McCleskey was born, one of the most famous lynchings in US history occurred in his hometown of Marietta, Georgia when people from that town lynched Leo Frank, a possibly innocent man lynched largely because he was Jewish. In 2008, more than 90 years after the lynching, the Georgia Historical Society along with several organizations erected an historical marker at the location where Frank was killed. Having visited the site of the lynching, I recognized how a modern-day marker, even in the midst of fast food restaurants on a busy street, could make one pause and reflect.

As the Equal Justice Initiative and others continue to work to memorialize other lynchings around the country, these monuments will not only help us remember those who died but also help us understand today’s society. Billie Holiday recognized this point when she performed the powerful anti-lynching song “Strange Fruit,” as did Woody Guthrie when he wrote the lesser-known song “Don’t Kill My Baby and My Son,” about an Oklahoma lynching witnessed by his father.

The ongoing work of activists to erect memorials at lynching locales is about who we are as much as it is about who we were. Just as it is important to remember the battlefields of war, we also need monuments to remember the battles for racial justice. As William Shakespeare wrote in The Tempest and as slightly altered in stone next to the entrance of the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C., “What is Past is Prologue.” We need memorials dedicated to the prologue of racial violence in order to effectively address our present and our future.

The post Racial terror and the echoes of American lynchings appeared first on OUPblog.

The third parent

The news that Britain is set to become the first country to authorize In Vitro Fertilisation (IVF) using genetic material from three people—the so-called ‘three-parent baby’—has given rise to (very predictable) divisions of opinion. On the one hand are those who celebrate a national ‘first’, just as happened when Louise Brown, the first ever ‘test-tube baby’, was born in Oldham in 1978. Just as with IVF more broadly, the possibility for people who otherwise couldn’t to be come parents of healthy children is something to be welcomed. On the other side, the cry goes up that this is a slippery slope, the thin end of the wedge, or any other cliché that you care to click on: at any rate, it is not a happy event, and it takes us one step further towards the spectre of ‘designer babies’. The issue here is about meddling with nature for the sake of hubristic human desires: seeking to ensure the production of a ‘perfect’ baby, and in the process creating the new monstrosity of triple parenthood.

The negative line about the new baby-making procedure is most often countered in these arguments by pointing out how negligible, in reality, is the contribution of the shadow third party. All that happens is that a dysfunctional aspect of the (principal) mother’s DNA is, as it were, written over by the provision of healthy mitochondrial matter from the donor; this means that the resulting baby will not go on to develop debilitating hereditary diseases that might otherwise have been passed on. The handy household metaphor of ‘changing a battery’ is much in use for this positive line: the process should be seen as just an everyday update. But the way that the argument is made—presenting the new input as a simple enabling device—reveals a need to switch off any suggestion that this hypothetical extra parent has any fundamental importance. The real identity of the future child must be seen to come from a primary mother and father, and them alone.

Mother’s Day Card, by Pugh, Daily Mail. February 4, 2105. CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

Mother’s Day Card, by Pugh, Daily Mail. February 4, 2105. CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0 via Flickr. But in actuality, three-parent babies already exist. According to the established facts of life, it seems obvious enough that a baby has two biological parents, and that the contribution is distributed between them with the god-given genetic equality of exactly 23 chromosomes each. But that is to forget a further biological element, the female body in which the new baby grows from conception (or just after, in the case of IVF) to birth. This used to be elided in the obvious certainty of maternal identity: if a woman gives birth, then the baby is ‘biologically’ hers: she was pregnant, the ovum came from her. (Whereas a father, until DNA testing, was always uncertain—pater semper incertus est, in the legal phrase—in the sense that there was no bodily evidence of any particular man having engendered any particular child.) But modern medical science has brought about the practical as well as the theoretical separation of egg and womb, breaking up what had previously appeared as—and still usually is—one single biological mother. With this not uncommon doubling of motherhood through IVF, three-parent babies have been with us for quite some time.

Twofold motherhood plays out in various possible scenarios. Conception outside the womb—in other words, in vitro fertilization—leads to the possibility of a woman giving birth to a baby of which she is not the genetic mother, because the embryo implanted in a womb doesn’t have to be formed from an egg taken from the same woman. Depending on whether that baby is going to become, postnatally, the child of the birth mother or else of the woman who provided the egg, this pregnant woman will be referred to as either the mother or the surrogate. Or, to tell the same story from the genetic point of view: IVF leads to the possibility of one woman’s egg making an embryo which develops in another woman’s womb. Depending on which of them is to raise the child, she will be regarded either as the egg donor (for the ‘real’ mother who becomes pregnant), or as the mother (who used a surrogate).

In all these scenarios—two in reality, four in story—biological motherhood is already divided between two women, with one or other element—the egg or the pregnancy—emphasised, depending on which of them is to become, in practice, the baby’s mother. The drive is always towards the subordination of one biological contribution so as to validate the other (and to remove the risk that the discounted proto-parent, the ‘donor’ or the ‘surrogate’, might have any postnatal responsibilities or rights). This is what is happening again with the controversy over the additional mitochondrial ‘parent’. But biologically three-parent babies are nothing new.

Featured image credit: Needle, by Melissa Wiese. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post The third parent appeared first on OUPblog.

March 8, 2015

Domestic violence: still a women’s issue?

In 1878, Frances Power Cobbe had published in Contemporary Review an essay entitled ‘Wife Torture in England’. That essay is noted for the its influence on the Matrimonial Causes Act 1878 that, for the first time, allowed women living in violent relationships to apply for a separation order. In the intervening 150 years, concern about violence experienced by women at the hands of their husbands, boyfriends, ex-husbands, ex-boyfriends, and other family members has reached around the world. Domestic violence is now a key concern discussed in a range of venues, from global summits to college campuses to sporting events to the Grammys. Domestic violence is now ‘everyone’s business’ (as the HMIC rightly titled its most recent inspection), but is it still a women’s issue? As research across the world shows, most physical and sexual violence in an intimate relationship is committed by men against women. In this sense, such violence is still a women’s issue. However, a few moments of reflection on the debates that have ensued since Cobbe’s intervention might suggest otherwise. Contemporarily there are three bones of contention: evidence (who does what to whom?); policy (how do we make a difference?); and politics (whose issue is this?).

Who does what to whom? Frances Power Cobbe was an influential voice of the suffragette movement. However, it was not until the presence of second wave feminism during the 1960s that domestic violence and marital rape became a focus of feminist campaigning and research. As a result of listening to women’s voices, feminist research spawned not only new empirical insights, but afforded a platform for theorizing violence through a gendered lens and carved out new methodological and epistemological terrain. However, such a lens is still resisted. Recurring questions include: Are women as violent as men in relationships? Don’t men suffer from domestic violence too? This ‘gender symmetry’ debate has occupied a fair few academics over their entire careers. Funnily enough, those working outside the ivory tower do not spend much of their time questioning whether women suffer the brunt of most violence and abuse dished out in private life. In the service delivery arenas occupied by police officers, accident and emergency staff, victim advocates, social workers, probation officers, and the like, it is self-evident that they do. Over time, domestic violence scholarship and research evidence has become much more nuanced, and our understanding of both the diversity of people who are affected by such violence, as well as the diversity of their individual experiences, grows each year. This more nuanced understanding makes it easier, rather than harder, for us to say that, yes, domestic violence is still a women’s issue.

How do we make a difference? Much of the effort worldwide has focused on the efficacy of a criminal justice response. As we have both written previously, any adversarial system of justice is inherently unsuitable and creates a number of dilemmas for those experiencing domestic violence as well as those whose job it is to deal with this high volume crime. It is time we reflect on what has been gained, as well as what has been lost or indeed what was never possible to have, from this focus on criminal justice. The problems with the police response noted in HMIC’s 2014 inspection echoed those in the 2004 inspection, which were the same failures that had been acknowledged for years. Jayne Mooney (2007) asked some time ago why violence against women was such a public anathema and a private commonplace all at the same time. Answering this question requires some imaginative interventions outside the criminal justice system; a range of community-based services for victims, as well as multi-agency partnerships and health-based initiatives, are notable steps in the right direction. Regardless of the form that domestic violence responses and services take, women will likely constitute the largest clientele—so is this still a women’s issue? You bet!

Since its emergence, domestic violence has been a political issue, one intertwined with women’s rights and debates about the role of the state in ‘private’ matters. Far from being a fringe issue, domestic violence is now a topic to which all politicians must pay lip-service, if nothing else. However, politically-minded individuals and organizations often disagree sharply over the idea of domestic violence being seen as a ‘women’s issue’. Does a focus on women benefit or hinder the creation of effective policy and legislative responses to domestic violence? Divergent answers to this question were apparent in the recent controversy regarding the Welsh Government’s legislative proposals to ‘end violence against women, domestic abuse, and sexual violence in Wales’. Only time will tell what the most politically expedient course of action might be, but at present it would be impossible to imagine domestic violence not as a women’s issue.

For International Women’s Day 2015 the theme is ‘Make it Happen’. Coming to grips with some of the persistent and knotty issues that pertain to understanding violence against women and making a difference in anyone’s life so blighted by such violence is a constant battle to ‘Make it Happen’.

Image Credit: “Never Alone.” Photo by Raul Lieberwirth. CC by NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Domestic violence: still a women’s issue? appeared first on OUPblog.

Copenhagen and the European jihad

The shooting spree in Copenhagen combines the old and the new of European jihadist phenomenon.

Like virtually all European Holy Warriors, Omar Abdel Hamid El-Hussein is not an immigrant, but the son of immigrants, Palestinians who settled in Denmark before his birth. He is thus but one of the “second generation” Muslims who have terrorized Europe, like Mohammed Siddique Khan and his collaborators who attacked the London transit system in July 2005.

The Muslim post-migrant faces a baffling clash of civilizations — the values and expectations of his hearth have been formed in a pre-modern village, but the street outside is drug infested. He encounters an alluring yet forbidden mass culture that encourages sexual liberation and economic ambition, even as the economy shrinks.

To whom does the troubled young Muslim, who is certainly not in the majority, turn in his identity crisis? Not to the family’s imam — imported from the home country. Instead he often turns to Saudi-financed Salafi preachers ranting that the folk Islam of his immigrant parents is mere “superstition” and “innovation” (bida). They stress that traditional Islam is what sanctions clan customs, such as the parental injunction to wed your distant cousin, unable to speak the language of her new home.

Salafi-Jihadis (such as the late Saudi Osama bin Laden and his Al Qaeda and ISIS disciples) denounce the elders’ Islam — with its rituals of dance and song, its ornamented mosques, and its saints and holy men seeking to mediate between worshipper and Allah.

Flowers in front of the Great Synagogue, Copenhagen, 15 February 2015 by Kim Bach. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Flowers in front of the Great Synagogue, Copenhagen, 15 February 2015 by Kim Bach. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Like the first European jihadi who bombed French trains in 1993, El-Hussein was radicalized in jail. El-Hussein also shares traits with at least two of the militants responsible for the Paris violence — not only homicidal anti-Semitism, but a criminal record, jail time, and an abrupt transition to militancy. The connection between criminal gangs and Islamic extremism is closer in Denmark than in most other European countries. But, though that nexus exists elsewhere in Europe, we should not draw the conclusion that most jihadis are former gangsters. The London bomber was not; neither were those who planned to attack American air bases in Germany, or those who sought to crash transatlantic flights leaving for the US from London’s Heathrow airport.

Research has uncovered no single profile for European jihadis, quite the contrary. They may be idealists, indigents, privileged, drop-outs, university graduates, psychopathic, or completely sane; former drug addicts or straights, men or women. He or she may come from a ghetto or a wealthy suburb, be born Muslim or a convert; may have traveled to Syria or Pakistan or simply been inspired by social media. Most European Muslims emigrated from Sunni countries like Algeria, Pakistan, Morocco, and Turkey, and therefore Europe’s jihadis are mainly Sunni. If he is Sunni, Shias are number one on his hit list (and vice versa if Shia), followed by Jews, homosexuals, and Westerners, not to mention cartoonists who publish images of Mohammed.

What they hold in common is a synthesis of revivalism and anti-imperialism. That Islam needs to return to the days of Mohammed and his companions (Salafs) the “corruption” of their parents’ traditional Islam. They long have blamed the West for the perceived degeneracy of their culture and armed interventions in Muslim lands. And their anti-Semitism, while hardly new, has been intensified by events in Gaza and by growing echoes from other European quarters.

But there is something really new here. The atrocities in Paris and Copenhagen mark an evolution in strategy. What used to distinguish Islamic from past terrorism (e.g. in Ireland) was spectacular mass murder of civilians. Now, after many foiled such efforts to reproduce 9/11 or the London bombings, Europe’s jihadis have grasped that they do not need mass murder to be spectacular. Moreover, social media has afforded a means to motivate a lone wolf or wolf packs (the latter seem to be the case in Paris and Copenhagen) to produce acts attracting enormous international attention and accomplishing the aim of terrorism — to terrorize the public and provoke authorities into thoughtless blunders like the Iraq intervention.

In jail, El-Hussein, according to the Danish press, spoke openly of his intention to travel to Syria to fight with the Islamic State. ISIS is another new element of attraction to Europe’s would-be Holy Warriors. Its effective, unspeakable homicide videos, expansion from Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon into Libya and Afghanistan, and its methodical use of social media and claim to a Caliphate, have energized European extremists.

What should the West do to cope? Our most urgent need is for information, which requires informants. And the most effective informants are Muslims. It is politically correct to attack so-called “Islamophobia,” but holding responsible Islam itself for jihadism is not only illiberal, illiterate, and intolerant, it is strategic idiocy. Our journalists and pundits need to recall that Islamic jihadis are not the first Holy Warriors. Let them try reading from the Book of Joshua or recalling the Christian conquest of Latin America, or, if memory will not serve that far back, North Ireland of the 20th century. If it does, they should explain that in Europe’s Dark Age, the Islam civilizations in Damascus, Baghdad, and Cordova literally preserved Western culture in the Europe’s Dark Ages and brought us mathematics and modern numbering from India.

The solidarity shown in Raleigh, North Carolina after the murder of three Muslim professionals should be exemplary. Failing that, exposing ignorant bigotry would be helpful. Beyond sympathetic informants, our intelligence and surveillance should focus on returning Western jihadis and current wannabees instead of scaring our citizens into imagining Big Brother is watching us and we live in Orwell’s 1984.

Secondly, we must avoid the trap of terrorist provocation. The current Salafist revival has spread to Mali and Nigeria, to India and Central Asia. We should be prepared to see this atrocious war (which is predominantly an intra-Islam, Sunni-Shia, war much like the Catholic-Protestant wars of the 16th and 17th centuries) to last far more than 30 years. We need a long-term strategy to prevent our being continuously bogged down, drained of our treasure, sacrificing the lives and limbs of our “volunteer” soldiers, and politically distracted by a conflict we cannot resolve. Our television stations should follow the precedent hopefully established by the current banning of ISIS video of a Jordanian pilot being burned alive. Television channels might supplement that step with clear and deep reporting instead of chorusing the identical, sensational, redundant, repeated coverage of a single transitory event. Our politicians and pundits should refrain from calling that essentially regional conflict a “threat to our freedom.” Terrorism has never been an existential threat, not even to small, isolated Israel, but certainly not to a country as wealthy and powerful as the United States, or to a region as rich and resourceful as Europe.

Finally we must not allow jihadism to distract us from the real existential threat could is brewing in the Pacific as China’s long-range geopolitical strategy reveals itself. So to combat jihadism, we need not only information, surveillance, and historical consciousness, but patience, self-restraint, and a view of the big picture.

Heading image: A danish flag in Hillerød by hjalmarGD. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Copenhagen and the European jihad appeared first on OUPblog.

What do you mean “woman problem”?!

They don’t like to admit it, but a lot of politicians have a “woman problem”. The phrase has become common parlance in British politics. David Cameron is widely considered to have a “woman problem” after patronising comments such as “calm down, dear”, and a raft of austerity policies made in the absence of women that have disproportionately hurt women voters. Recent polling data shows that women are more likely than men to vote Labour and less likely to vote Conservative. They are less likely to vote for UKIP, with Nigel Farage’s ill-chosen comments on breastfeeding doing little to help his party’s image with women. Labour have also struck the wrong note with women after using a bright pink bus to promote politics to women. The Lib Dems face a host of problems including an all-male front bench, prospective wipe-out of their female MPs, and the Lord Rennard scandal.

While David Cameron might be worried about appealing to women voters, there are two woman problems he doesn’t have. The first is domestic; Samantha Cameron is an asset to her husband and their relationship appears to be beyond reproach. The second is political; while Theresa May is still the favourite to succeed Cameron as party leader, there is no credible threat from a female-led political party in the coming election.

David Cameron thus offers a striking contrast to French president François Hollande. In terms of women’s representation, France is currently doing better than the UK. They have (a few) more women in parliament (currently 26.5%) and, unlike Cameron, Hollande kept his promise to have more women in government. Excluding the (male) prime minister, the French government and cabinet have comprised 50% women since Hollande was elected president in 2012. Hollande also reinstated a fully-fledged women’s ministry, led by a member of cabinet. With women highly visible in decision-making roles, Hollande has evaded claims of ignoring and mistreating women voters.

That doesn’t mean, however, that Hollande has no “woman problem”. Far from it. He has several. His first problem is both personal and political; his girlfriends keep getting him into trouble. For nearly thirty years, he was in a relationship with Ségolène Royal, the mother of his four children. They had separated by the time she ran for the presidency in 2007, although their separation was only announced formally after the end of her campaign. He had left her for a journalist, Valérie Trierweiler. In 2012, having lost the presidential nomination to Hollande, Royal gave him her public backing. In return, he supported her candidacy in the legislative elections held shortly after his presidential victory. Then came the devastating blow – in a fit of jealously, Trierweiler tweeted her support for Royal’s opponent, who went on to win the seat. Hollande’s carefully crafted image of a calm, presidential figure (in contrast to his predecessor Nicolas Sarkozy, whose frenetic style was underpinned by a divorce and whirlwind remarriage while in office) was undone in 140 characters. His poll ratings took a tumble. And the damage continued; in early 2014 it emerged that he was having an affair with an actress, precipitating his break up with Trierweiler. She took her revenge later that year, publishing memoirs that hit Hollande where it most hurt: politically. She painted him as a snob who despised poor people — a devastating critique for a Socialist president. His poll ratings tumbled further.

Dusk over Assemblee Nationale, French Parliament seen across the Pont de la Concorde and Seine river. © Shelly Perry via iStock.

Dusk over Assemblee Nationale, French Parliament seen across the Pont de la Concorde and Seine river. © Shelly Perry via iStock.A very different woman has compounded this woe for Hollande. While the centre-right UMP party has wobbled under its own leadership crises, the far-right Front National has gone from strength to strength under the leadership of Marine Le Pen. She has worked hard to “detoxify” the party’s image and has lent a rejuvenated, modernised and more approachable face to the party. She has helped to bring more women voters to the traditionally male-dominated party, and the FN are currently enjoying record performances in the polls. More than a third of voters now see the FN as a credible choice, and Le Pen tops polls for the first round of the 2017 presidential election. While she would certainly lose in the second round, her qualification would likely come at the expense of Hollande, adding humiliation to the pain of defeat.

Can women voters save the day for Hollande? The likely answer is ‘no’. While Hollande has not excluded them à la Cameron or abused them DSK-style, nor has he earned their unqualified support. His government, while respecting gender parity, has women mostly in less prestigious, stereotypically “feminine” portfolios, while most of the heavy-hitting top jobs have gone to men. The women’s ministry was downgraded after two years and buried within the much larger Ministry for Social Affairs, Health and Women’s Rights. Perhaps most importantly, his infidelity and commitment phobia in his personal relationships are mirrored by indecisiveness and weakness in his political leadership.

Why should politicians worry about women? Several reasons. First, women are the majority of the electorate. Second, women largely want the same things as men: strong leadership and a healthy economy. And third, it’s simply good politics. Utilising all the talent within your party and ensuring that your policies and personal conduct do not marginalise large groups of voters is basic common sense. So why do politicians find it so hard?

The post What do you mean “woman problem”?! appeared first on OUPblog.

March 7, 2015

The paradox of generalizations about generalizations

A generalization is a claim of the form:

(1) All A’s are B’s.

A generalization about generalizations is thus a claim of the form:

(2) All generalizations are B.

Some generalizations about generalizations are true. For example:

(3) All generalizations are generalizations.

and some generalizations about generalizations are false. For example:

(4) All generalizations are false.

In order to see that (4) is false, we could just note that (3) is a counterexample to (4). The following argument is a bit more interesting, however.

Proof: Assume that sentence (4) is true. Then, given what (4) says, all generalizations are false. But (4) is a generalization, so (4) must be false, making (4) both true and false. Contradiction. So (4) can’t be true, and hence must be false.

(4) has an interesting property, however. Although, as we have seen, not all generalizations are false, and hence (4) fails to be true, it is itself a false generalization, and hence is a supporting instance of (4). In other words, since (4) is false, the existence of (4) provides some small amount of positive evidence in favor of the truth of (4), even if, in the end, our proof of (4)’s falsity trumps this small bit of defeasible evidence.

Thus, we can introduce the following terminology. A generalization about generalizations of the form:

(5) All generalizations are B.

is a self-supporting generalization if it in fact has property B – that is, if it has the property that it ascribes to all generalizations (regardless of whether all other generalizations have this property, and thus regardless of whether the generalization in question is itself true or false). In short, a generalization about generalizations is self-supporting if it has the property that it says all generalizations have.

Jackson Pollock, Convergence 1952. Photo by C-Monster CC-BY-NC-2.0 via Flickr

Jackson Pollock, Convergence 1952. Photo by C-Monster CC-BY-NC-2.0 via FlickrIt is easy to show that any true generalization about generalizations will be self-supporting (proof left to the reader). But false generalizations might be self-supporting, like (4) above, or they might not. For example:

(6) All generalizations are true.

is false, since (4) is false, and hence a counterexample to (6). But it is not self-supporting, since it would have to be true to be self-supporting.

To obtain the paradox promised in the title of this post, we need only consider:

(7) All generalizations are not self-supporting.

Note that we could express this a bit more colloquially as “No generalizations are self-supporting.”

Now, (7) is clearly false, since we have already seen an instance of a self-supporting generalization. But is (7) self-supporting? As the reader has no doubt guessed, there is no coherent answer to this question:

Proof of Contradiction: (7) is either self-supporting, or it is not self-supporting.

Case 1: Assume that (7) is self-supporting. If (7) is self-supporting, then it has the property that (7) says all generalizations have. (7) says that all generalizations are not self-supporting. So (7) is not self-supporting after all. Contradiction.

Case 2: Assume that (7) is not self-supporting. But (7) says that all generalizations are not self-supporting. So (7) has the property that (7) says all propositions have. So (7) is self-supporting after all. Contradiction.

Note that this paradox, unlike the Liar paradox (“This sentence is false”) does not involve any problems with regard to determining the truth-value of (7). As we have already noted, we can straightforwardly observe that (7) is false. The paradox arises instead with regard to whether (7) has the rather more esoteric property of being self-supporting. It turns out that (7) has this property if and only if it doesn’t.

The post The paradox of generalizations about generalizations appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers