Oxford University Press's Blog, page 694

February 28, 2015

Wolf Hall: count up the bodies

Historians should be banned from watching movies or TV set in their area of expertise. We usually bore and irritate friends and family with pedantic interjections about minor factual errors and chronological mix-ups. With Hilary Mantel’s novels Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies, and the sumptuous BBC series based on them, this pleasure is denied us. The series is as ferociously well researched as it is superbly acted and directed. Cranmer probably didn’t have a beard in 1533, but, honestly, that’s about the best I can do.

In any case, criticising historical fiction for being fiction is not particularly clever. The imaginative space through which novelists and screen-writers move is one historians can only look in on from outside with envy, and from which we should learn lessons about practicing our own craft. Yet writing historical fiction, as opposed to another kind, means operating within a set of constraints, as well as investing one’s work with a particular kind of moral authorization. It involves drawing on a well of audience knowledge and expectation, even as it sets out to challenge or surprise.

Here historians do have the right to comment. The question is not whether fiction gets the past exactly right (no two historians would agree upon this anyway), but how claims about the past are used to address questions about the human condition. All historical writing, fictional and ‘factual’, is a kind of conversation between past and present. And in any conversation, we need to listen as well as talk.

In making Thomas Cromwell the focus of attention, Mantel believes she is enabling a suppressed voice to be heard. As chief minister of Henry VIII, Cromwell is not an obscure figure, but he left few records of an intimate or revealing kind. Moreover, his popular reputation suffered in the later twentieth century due to the success of Robert Bolt’s play, A Man for All Seasons (turned into a critically-acclaimed 1966 film), where he serves as foil to the hero, Thomas More, whose lonely refusal to recognise Henry VIII’s Supreme Headship of the Church marks him out as a martyr for individual conscience.

“Although a major protagonist, More’s ‘big moments’ are routinely silenced or sidelined.”

Wolf Hall is a riposte to A Man for All Seasons as much as it is a fresh reimagining of the Tudor World. Bolt’s More, gentle family-man and courageous non-conformist, becomes in Mantel’s vision a cruel, conceited misogynist; Bolt’s Cromwell, a brutal pragmatist, unfolds before us as complex, passionate, and profoundly humanitarian.

This is not as iconoclastic as recent commentary suggests. Zinneman’s film of A Man for All Seasons was from the moment of its cinematic release a spur to revisionist historical scholarship on More, drawing attention to his hatred of heresy, and the implausibility of his holding or expressing the views on the inalienable rights of conscience that Bolt (in the aftermath of McCarthyism) attributed to him. As Wolf Hall replaces Man for All Seasons as the lens through which most people will view the 1530s, let’s hope it will similarly energise historians.

After catching up on iPlayer, this historian’s reaction is of (almost) admiration for the thoroughness with which the ‘dismanteling’ of More has been carried through. A revealing line is given to Cromwell, as More maintains his frustrating ‘silence’ over the Oath: ‘he wrote this play years ago, and he sniggers every time I trip over my lines’.

Cromwell need not have worried: suspecting that the garrulous More wrote the historical script to his own advantage, Mantel and her adapters, assisted by Anton Lesser’s outstanding performance, have systematically – ruthlessly – rewritten it, down to costume and props. The historical More’s lack of care over personal appearance becomes here distasteful and unsettling. Cromwell – in common with the entire membership of Facebook – likes playful kittens; More appears cradling a showy, and eerily inert, long-eared white rabbit. And is it me, or does Mark Rylance resemble the More of Holbein’s famous portrait much more than he does the corresponding painting of Cromwell? A particularly mischievous touch robs More of the one distinction guaranteed to score points with a modern secular audience: his unusual concern for the education of his daughters. Cromwell’s ill-fated little girls – implausibly – are being taught Latin and Greek too.

Thomas More statue, Chelsea Old Church. By Edwardx. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Thomas More statue, Chelsea Old Church. By Edwardx. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Although a major protagonist, More’s ‘big moments’ are routinely silenced or sidelined. We see, but do not hear, the conversation accompanying his surrender of the chancellorship to Henry (who promised ever to be his ‘gracious lord’); nor his words at the block, where he joked with the executioner and announced, with characteristic irony, that he died ‘the king’s good servant, but God’s first.’ More’s eloquent speech at the end of his trial is reduced to the shouting of hackneyed slogans. And Mantel wants us to think (against the balance of probability) that his conviction was not caused by Richard Rich’s perjury; rather, More carelessly lets slip his real opinions because he thinks Rich is a person of no importance.

More’s most poignant utterance was made (during an interrogation) in Cromwell’s presence: ‘I do nobody harm, I say none harm, I think none harm, but wish everybody good. And if this be not enough to keep a man alive, in good faith I long not to live’. In Wolf Hall, More only has time to utter the first few words before an enraged Cromwell cuts him off: no harm! What about Bilney, what about Bainham? These Protestants were burned during More’s period as Lord Chancellor, and we have seen More personally supervising Bainham’s torture. His own fate is more merciful than the treatment he dished out to others.

Mantel’s revisionism seems here to be on strong moral and historical turf. More did believe – an embarrassment to his modern admirers – that unrepentant heretics deserved to die. Yet this was an utterly conventional sixteenth-century opinion, and although More detested ‘heresy’, for both theological and social reasons, he hardly initiated a genocidal slaughter. Six Protestants were burned during his Chancellorship, and he was personally involved in only three of the cases. The accusation of overseeing torture – though made by his enemies at the time – is almost certainly false. More, who had a marked aversion to perjury, denied it in detail in print.

As (Mantel’s) More’s refusal to take the Oath of Succession drags on, Anne Boleyn suggests the wrack. ‘No madam, we don’t do that’, Cromwell icily retorts. Cromwell’s occupancy of the higher moral ground defines his relationship with the supposedly urbane More, and is the marrow of our moral kinship with him.

But does he really deserve to stand there? The historical Cromwell was deeply involved in the fate of the Carthusian monks who, like More, could not bring themselves to recognise Henry’s new title: half a dozen were butchered after spending weeks chained to posts by their necks and legs, stewing in their own excrement. A further ten starved to death in prison. They were executed for ‘treason’, which to modern minds tends to seem less unwarranted than punishing heresy. But Cromwell was implicated in heresy cases too, arranging the burning in 1538 of a Franciscan for the political heresy of saying Rome was the true Church. And in June 1535, it was under commission from Cromwell as the king’s vicegerent (or deputy) that at least ten Flemish immigrants were executed for denying infant baptism. They died so that Henry VIII could demonstrate that – despite rejecting the pope – he was still an orthodox Christian. Cromwell personally promised the emperor’s ambassador that the sentences would be carried out. Thomas Cromwell, in fact, was instrumental in more burnings for heresy than Thomas More was, though his reasons were different.

Whether the motivations behind coercive violence really make some instances of it more defensible than others is a question the past can fairly ask the present. And one which historical fiction might help us honestly explore.

The post Wolf Hall: count up the bodies appeared first on OUPblog.

February 27, 2015

Four remarkable figures in Black History

For Black History Month, entries from Oxford University Press’s African American National Biography (AANB) have appeared weekly on The Root, an online magazine of African American culture an politics. The Root’s Editor in Chief, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., of Harvard University is also Editor in Chief of Oxford’s African American Studies Center, which includes the online incarnation of the AANB. Here, Steven Niven highlights four remarkable black lives that feature on the site.

Given the scope and the length of time I’ve been working on the African American National Biography (over 13 years and counting), selecting just a few biographies that were somehow “representative” of the overall project would have been an impossible task. Instead, working with The Root’s managing editor, Lyne Pitts, I chose four entries that showcased some of the diversity of the collection, but focused on hidden or barely remembered figures in black history.

William ShoreyA late 19th century whaling captain, known as the “Black Ahab”

Shorey’s biography is in many ways a classical 19th century tale of individual courage. Born the mixed race son of a Scottish sugar planter and a Barbadian woman, and with dwindling economic opportunities for people of color in the Caribbean, he left for New England in 1870. There a long tradition of African American whaling offered him a chance to rise through the ranks and by courage, hard work, and luck—he nearly drowned on an early voyage—came to command his own vessel in his twenties, by which time he had moved from the frigid North Atlantic whaling grounds to the more temperate Pacific coast, based in San Francisco.

Gladys BentleyThe 1920s blues singer and Harlem Renaissance figure

Bentley offered a rare opportunity to examine the life and career of an openly lesbian woman; our 5,500 biographies undoubtedly include a significant number of subjects whose sexual identity is unknown. Although a pioneer in the 1920s and the early 1930s—even famously claiming to have married a white woman in New Jersey–by the end of her career in the 1950s, Bentley proclaimed that she had been “cured” of her homosexuality by a combination of hormones, psychotherapy, and faith. Like all of us, Gladys Bentley left behind fragments of her words, performances, and acts. The challenge for the biographer is to patch the fragments together, summarize them as accurately as possible, and connect the individual life to their broader time and space. Gladys Bentley’s biography, for example, certainly contrasts the relative sexual freedom of the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s with Cold War conformity—and the same could be said for contemporaries like Bayard Rustin, the gay architect of the 1963 March on Washington.

1920 painting of Marie Laveau (1794–1881) by Frank Schneider, based on an 1835 painting (now lost?) by George Catlin. Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Marie Laveaux

1920 painting of Marie Laveau (1794–1881) by Frank Schneider, based on an 1835 painting (now lost?) by George Catlin. Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Marie Laveaux The vodou queen of New Orleans

Unlike Shorey and Bentley, Laveaux, is hardly a figure “hidden from history”; after all her grave is allegedly the second most visited in the United States, after Elvis Presley’s. But her life (and after life) has been shrouded in so much mystery and confusion over the role and meaning of vodou that Marie Laveuax’s actual biography is often lost, like the last letter of her name, which is nearly always given as Laveau. Adapting this entry, written in 2004, also served the purpose of updating the historical record. New evidence shows that the father of Marie’s three daughters was white, and not a free man of color as most biographies have stated, including our own. Thankfully, such corrections can easily be updated online.

Charles CaldwellA Mississippi Reconstruction politician

As a former slave and pioneering member of the first black political generation, Charles Caldwell allows us to see both the democratic and revolutionary potential of the Reconstruction Era, and the chilling violence that prevented the full enactment of those ideals until the Second Reconstruction after World War II. Mississippi’s white Democrats fought hard to maintain the political supremacy they had won by defeating Caldwell and the Republicans in 1875.

The response to the biographies on the Root website, Twitter feed, and Facebook page, has been overwhelmingly positive. The series will now continue into March, featuring four additional African American National Biography entries on notable black women for Women’s History Month.

Headline image credit: New Orleans, sketched from the opposite side of the river upon a mast of a vessel during a very low water / sketched in October 1839 by S. Pinistri, arch’t. and civil engr. Library of Congress.

The post Four remarkable figures in Black History appeared first on OUPblog.

Are you as smart as a dolphin? [quiz]

Dolphins are famous not only for their playful personalities, but also for their striking level of intelligence. After half a century of study, scientists have learned a lot about these beloved mammals, gaining valuable insight into their unique behavior. However, many myths surrounding dolphin behavior still exist, making it difficult to discern fact from fiction. Can you tell the difference? Take this quiz and find out!

Get Started! Your Score: Your Ranking:Image Credit: “Jumping Dolphins.” Photo by Tambako The Jaguar. CC by ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Are you as smart as a dolphin? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

The sombre statistics of an entirely preventable disease

Sore throats are an inevitable part of childhood, no matter where in the world one lives. However for those children living in poor, under-resourced and marginalised societies of the world, this could mean a childhood either cut short by crippling heart failure or the need for open-heart surgery. Rheumatic heart disease, a permanent condition affecting the heart valves and can result in heart failure, arrhythmias (irregular heartbeat), and stroke, is entirely preventable by treating streptococcal sore throats at the outset. Those who live with the condition in developing countries are young, largely female and are suffering with a significant disease. My team and I conducted a recent study featuring 25 hospitals in developing countries (12 African nations, Yemen, and India), which once again exposed the sombre statistics of this disease.

There were several important findings of our study. First, it revealed the stark reality of the patients affected by the disease. The median age of the 3,343 patients enrolled was only 28, with two-thirds of them being female. The majority were in a severe condition with established heart failure, and evidence of atrial fibrillation (an irregular and often abnormally fast heart rate) and pulmonary hypertension (raised blood pressure in the pulmonary artery). These complications imply long-standing disease with further potential for additional consequences such as stroke, commonly caused by rheumatic heart disease in the developing world. Such advanced disease may require invasive intervention such as percutaneous or surgical management, which is often not available in the countries that need it the most. Our second finding was the clear disparities in both the management and the resources to deal with severe disease in patients living in low-income countries compared to those living in high-income countries. Only 1% of the patients in low income countries underwent a percutaneous procedure, compared to 11 % in lower middle income countries, while 8% of the patients in low-income countries had had surgery compared to 61% in middle-income countries. Cardiac surgery is at an absolute premium in developing countries, with only a handful of established teaching and training units in Africa capable of conducting high-volume paediatric and adult cardiac surgery, despite the great need.

Rheumatic heart disease affects the most vulnerable people and once again, this is evident, not only in the youth of the cohort but also their gender. Two-thirds of the patients enrolled in the study were women, 82.5% of which were of childbearing age. Valve disease results in significant physiological effects during pregnancy and thus rheumatic heart disease is associated with maternal mortality and fetal loss. A previous study of 46 pregnant Senegalese women with rheumatic heart disease reported 17 maternal deaths (34%), six fetal deaths, and five therapeutic abortions.

Children Burkina Faso. Public domain via Pixabay

Children Burkina Faso. Public domain via Pixabay

Women in Africa, Yemen, and India are young and seriously affected by their disease, however almost all were not on contraception. Moreover, some were already pregnant and managed with warfarin, a drug known to cause fetal loss, fetal abnormalities, and additional complications during pregnancy.

Rheumatic heart disease is a permanent condition, with medical management only limiting the progression of the disease. A key management tool is secondary prevention with penicillin prophylaxis to stop further attacks of streptococcus, which exacerbates valve damage. For severely affected post-operative patients, lifelong secondary prevention is vital, yet only 55% of patients were prescribed secondary prophylaxis. This percentage was even lower (29%) in middle-income countries, despite the fact that these countries have published national guidelines dictating lifelong use of penicillin. Thus, physicians dealing with patients with rheumatic heart disease need to urgently review the reproductive services and advice given to women with rheumatic heart disease, while adhering more closely to national and international guidelines for secondary prophylaxis.

Patients with stroke, atrial fibrillation and mechanical valves are managed in part with anticoagulants, predominantly with warfarin. This drug, although inexpensive, requires regular monitoring and review. This is another major area of concern as a third of patients with the need for oral anticoagulation were not prescribed them; almost half of those on anticoagulants had inappropriate monitoring. There are several reasons for this, including the unavailability of medication and a lack of monitoring. It is clear that there are multiple challenges at every level of dealing with this disease, many reflecting critical health system roadblocks such as delivery of safe and affordable medication.

What does the future hold for the millions (estimated at over 30 million) living with and newly diagnosed with this disease? This study represents not only the reality of patients living in developing countries but also a group of physicians and researchers committed to describe the burden of this disease in the developing world while seeking innovative, affordable, and accountable solutions to the challenges set forth in this report. Several have been involved in recent publications, research and awareness events and the determination to address this disease in all spheres is evident.

The re-emergence of rheumatic heart disease as a priority condition and the sombre profile of this disease deserves the fullest attention of the world.

Heading image: Very high magnification micrograph of rheumatic heart disease by Nephron. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The sombre statistics of an entirely preventable disease appeared first on OUPblog.

Why we should read Dante as well as Shakespeare

Dante can seem overwhelming. T.S. Eliot’s peremptory declaration that ‘Dante and Shakespeare divide the modern world between them: there is no third’ is more likely to be off-putting these days than inspiring. Shakespeare’s plays are constantly being staged and filmed, and in all sorts of ways, with big names in the big parts, and when we see them we can connect with the characters and the issues with not too much effort.

Dante is much more remote – a medieval Italian author, writing about a trip he claims to have made through Hell, Purgatory and Paradise at Easter 1300, escorted first by a very dead poet, Virgil, and then by his dead beloved, Beatrice. and meeting the souls of lots of people we only vaguely know of, if we’ve heard of them at all. First he sees the damned being punished in ways we are likely to find grotesque or repulsive. And then, when he meets souls working their way towards heavenly bliss or already enjoying it, there are increasing doses of philosophy and theology for us to digest.

Yet we might feel we should give it a go and grit our teeth, get hold of one of the hundreds of translations that have appeared since the first complete one of 1802 by Henry Boyd. With luck we will make it through to the end of Inferno, impressed by the geography of the afterworld and by Ulysses, Francesca da Rimini and some of the other leading figures, but generally still feeling uncomfortable with the idea that Dante might be doing something up to Shakespeare’s standard. In 1818 a friend of Byron’s, John Cam Hobhouse, was told by an acquaintance working for the Longman’s publishing firm that ‘the world was sick of Dante’. And even the well-intentioned contemporary reader can feel much the same deep down.

The fact is Dante has never been for wimps. There are stories of Florentine workmen chanting bits of the poem (badly), but serious early readers needed help almost as much as we do. Manuscripts produced less than twenty years after his death in 1321 are already full of notes explaining what words mean, who the characters are, what Dante is really saying. In other words Dante asks his readers to be ready to work at his poem, to put themselves into it, rather than just be passive recipients of otherworldly wisdom, and if they do, his bet is that they will get a great deal out of it.

![The Parnassus, by Raphael [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1425143759i/13852858._SY540_.jpg) The Parnassus, by Raphael. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The Parnassus, by Raphael. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons That too may sound off-putting. Do you have to put in a daily dose of study over fifty years as W.E. Gladstone apparently did? Modern scholarship often gives the impression of being a hotbed of internal dissent, but it seems united in presuming that to understand Dante you have to know the Bible, Aristotle, the byways of Medieval thought and much more. If that’s the situation, maybe Dante really is unreadable for most people.

The opposite is true. With a modest amount of patience the busy modern reader, Italophone or not, should be able to get a long way into Dante and to enjoy him. There isn’t an end-point, any more than there is with Shakespeare. Dante presses his readers to think (and to enjoy thinking) in a way Shakespeare doesn’t, and he has some very clear ideas he wants us to accept and assimilate. But he provides fewer definitive answers to the problems he obviously raises than we might expect. That is one of the reasons for dissent among scholars, and also one of the reasons why every reader, given a certain amount of information about the context, idiom, and history, can think things through for himself or herself, and up to a point to construct his or her own Dante. And what we think about regards not just the fate of souls after death but even more human life on this earth. The idiom may be foreign, the world view long vanished, but, though Dante is not our contemporary, much of what he says about morality, politics, language and love bears in on our lives today (for instance, his insistence that organised religion and the secular state must not interfere with each other).

And then of course there is the poetry. The power, economy and delicacy of the phrasing may or may not trickle through into English, but it’s hard not to be swept away by the sheer inventiveness of his imagery, ranging from the suicide Pier della Vigna transformed into a barren but strangely articulate tree to lovers of wisdom appearing to Dante’s amazed gaze in heaven like circles of dancing stars; from the sad father-figure of Virgil to the beautiful, authoritative Beatrice.

The addictiveness is evident from the fact that Dante enthusiasts, Christian or not, find it hard to imagine Hell in any other way, and spend happy minutes musing about which circle is best suited to some particular friend, enemy or public figure. Dante thought Paradise was much more difficult to get into and much more difficult to describe. We are certainly not accustomed to prolonged evocations of happiness. Paradiso gives us one way, and an astoundingly dynamic one, of thinking about what human happiness might ultimately be.

Featured image credit: Beatrice Addressing Dante, by William Blake. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why we should read Dante as well as Shakespeare appeared first on OUPblog.

February 26, 2015

Iggy (Azalea) pop: Is cultural appropriation inappropriate?

Popular music is much more than mere entertainment—it helps us make sense of who we are or who we hope to be. Although music is but one of pop culture’s media outlets, our tendency to embody and take ownership of sound—whether through our headphones, MP3 downloads, dancing, or singing—often makes it difficult to separate our personal connection to popular music from the cultural context in which it was created. But if we listen carefully to its reverberation throughout the nation, we might better understand how the subconscious of our society is shaped by what gets recorded and distributed to the masses. Our sonic diets might be more detrimental to our well being than we might think; especially if we consume popular music without attention to its ingredients.

One of the key ingredients of today’s popular music—cultural appropriation—is a hot-button issue. It’s been the subject of a recent and rather unprecedented court dispute (Marvin Gaye’s estate vs. Robin Thicke and “Blurred Lines”), as well as in heavy rotation on social and other popular media in response to the recent popularity of hip-hop-signifying white performers, such as Mackelmore & Ryan Lewis, Kreayshawn, Miley Cyrus, and Iggy Azalea. Katy Perry, among others, suggests that without the “blending” that results from cultural appropriation, popular music in the United States might only be about “hot dogs and baseball.” Yet, the blending, mixing, and hybridizing of culture into popular music are not without consequences. The “diversity” of popular sound in the United States is often in conflict with the lack of diversity and prejudices embedded into its societal structures. However, the performative scripts that are derived from the margins of culture and limited by discriminatory systems—racism, sexism, classism, and homophobia, etc.—are often what drive the appeal of popular media, music, and images in our capitalist culture. Cultural appropriation in contemporary pop music is defined by this paradox, but as the old saying goes, “ain’t nothing new under the sun.”

“When the relay starts I’m a runaway slave-master

Shittin’ on the past gotta spit like a pastor”

When the Australian-born Iggy Azalea—in her distinctly choreographed, somewhat caricatured “black”-sounding, southern-influenced rap voice—spit this culturally offensive lyric in her 2012 song, “D.R.U.G.S.,” she unknowingly connected her impending success to America’s often unspoken, yet fairly recent and real troubled past. With her vocal and lyrical stylings, Azalea indirectly invokes America’s history of the commodification of black people and tropes of blackness through slavery and blackface minstrelsy. Created during enslavement and persisting through Emancipation, Jim Crow, and Civil Rights, blackface minstrelsy gained widespread popularity and became the first and most ubiquitous form of popular entertainment native to the United States. In blackface makeup, white men performed their imagined, stereotyped tropes of black(male)ness (angular posture, broken dialect, dumb, overtly sexual, violent, machismo, lewd movement, etc.) for mostly white audiences throughout the country.

The music that developed from these wildly popular performances (think on the level of American Idol or The Voice) was a combination of what was drawn or “appropriated” from real and imagined African American performance practices, as well as from their own white cultures, particularly of Anglo, Irish, and Jewish heritage. On the one end, what resulted from blackface minstrelsy were popular, everyday reinforcements of racial stereotypes and prejudices against African Americans that have persisted in society’s popular imagination since enslavement. On the other, what developed was a new, lucrative form of popular music—created by white performers’ select appropriation of black signifiers—that established the structural and aesthetic development of the mass music and entertainment industry. When we consider appropriation in the context of America’s cultural and musical past, we might continue to think more about who stands to gain the least/lose the most and gain the most/lose the least by appropriating black signifiers in popular music and society, why that might be, and why we (or our ears) should care.

In his 2003 book of the same title, music and cultural critic Greg Tate defines the “burden” of being black in America as a “systematic denial of human and constitutional rights and equal economic opportunity.” Fast-forward to over a decade later, and we now find ourselves in a time where our President is black, “post-racial” is a buzz word, and hip hop performance signifiers are all-the-rage in the “pop” music of many of the top-selling, record-breaking, non-black (well, mostly white) performers—even Taylor Swift has shed her country-pop roots for more urban (i.e., black) ones as she proclaims the “haters gonna hate” in her recent album’s lead hit, “Shake it Off.”

Iggy Azalea’s hip hop pop has also broken records; she is currently the female rapper with the longest running number one single on the Billboard Hot 100, received four huge Grammy nominations, as well as won awards for best hip hop album at the People’s Choice, Kid’s Choice, and American Music Awards. Although a contemporary female rap artist like Nikki Minaj has had a significant artistic/aesthetic impact upon contemporary pop and hip hop, and creative rap artists like Azealia Banks (a huge critic of Iggy Azalea) have significant underground followings, (black) women have not gained such popular acclaim as Iggy in hip hop since Lauryn Hill’s genre-defying and genre-defining 1998 album, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill.

While the crossover appeal of white artists employing black tropes might gain mass popularity and signal racial progress to some, the many recent cases of police injustice and brutality, the black and brown base of mass incarceration, and the economic, health, and educational disparities faced by African Americans and other communities of color require us to interrogate the extent of this “progress” in society.

“To live so completely impervious to one’s own impact on others is a fragile privilege,

which over time relies not simply on the willingness but the inability of others…

to make their displeasure heard.”

— Patricia J. Williams

Given the privileged history of white performers’ and consumers’ ability to commodify and delimit idea(l)s of blackness through slavery and blackface minstrelsy, to appropriate signifiers and/or stereotypes of blackness for personal, economic, or aesthetic benefits as performer or consumer of contemporary popular music—without the experience or “burden” of being black or interrogating the systematic privilege of whiteness, maleness, as well as heterosexual and class privilege—is to remain complicit in the history of covert and overt acts of racial and other forms of structural oppression.

If we, as artists, industry executives and producers, critics, and consumers don’t take the time to critically interrogate our own fears, desires, and points of privilege in the production of the music that we help make popular, then the possibility for politically generative, cross-cultural works of popular art that are economically, socially, and morally beneficial for all parties involved (and just not those with structural access and privilege) simply become another form of inappropriate and often damaging cultural appropriation. If we take the time to interrogate and not just consume America’s sonic “melting pot,” we might better hear how the abuse of cultural appropriation in popular music is a key ingredient to how cultural retrogress persists under the guise of societal progress.

Headline image credit: Color Concert. By Eduardo Merille. CC BY SA 2.0 via flickr.

The post Iggy (Azalea) pop: Is cultural appropriation inappropriate? appeared first on OUPblog.

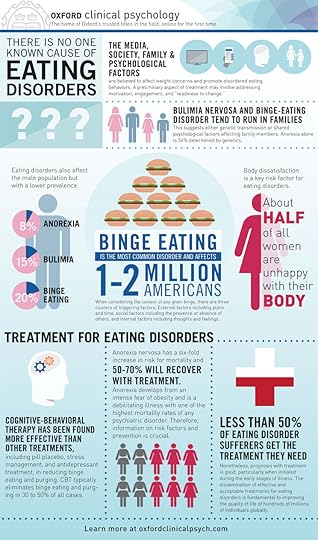

Understanding the psychology of eating disorders [infographic]

More than 30 million people in the United States suffer from an eating disorder. In acknowledgement of National Eating Disorders Awareness Week, we’ve put together a detailed infographic with facts and statistics based on information from Oxford Clinical Psychology. Explore the infographic for a better understanding of what millions of Americans suffer through on a daily basis. For more information on eating disorders, such as bulimia nervosa, treatments for binge eating and purging, and the significance of body image, visit Oxford Clinical Psychology.

Download the infographic in pdf or jpeg.

Headline image credit: Hamburger. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Understanding the psychology of eating disorders [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

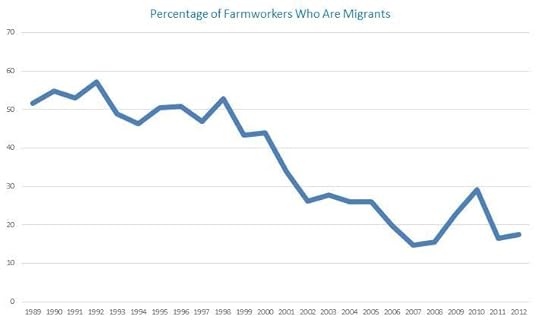

Are migrant farm workers disappearing?

Migrant farmworkers plant and pick most of the fruits and vegetables that you eat. Seasonal crop farmers, who employ workers only a few weeks of the year, rely on workers who migrate from one job to another. However, farmers’ ability to rely on migrants to fill their seasonal labor needs is in danger.

From 1989 through 1988, roughly half of all seasonal crop farmworkers migrated: traveled at least 75 miles for a U.S. job. Since then, the share of workers who migrate has dropped by more than in half, hitting 18% in 2012. Because of this drop in the number of migrants, farmers are increasingly struggling to find workers to pick their crops before they spoil.

Graph by Jeffrey M. Perloff. Used with permission.

Graph by Jeffrey M. Perloff. Used with permission. What explains this pronounced drop in migrants? The two main explanations are

(1) Governmental and economic changes in the United States and Mexico made immigration less attractive.

(2) Demographic changes made farm workers less willing to migrate.

Governmental and economic changes reduced the number of undocumented immigrants from Mexico. After 9/11, new laws and greater enforcement increased the difficulty for undocumented workers to cross the border. Undocumented workers who were already in the United States became more fearful of moving for work because of new federal, state, and local laws and increased resources for local immigration enforcement to apprehend them. In addition, Mexicans are less likely to want to work in U.S. agriculture than in the past due to a falling birth rate, an improving economy, and increased social welfare programs.

Migrant farm workers. Image by Jeffrey M. Perloff. Used with permission.

Migrant farm workers. Image by Jeffrey M. Perloff. Used with permission. Migrants have different characteristics than non-migrants. For example, since 1999, 55% of migrant agricultural workers, but only 40% of non-migrants are undocumented. A non-migrant is roughly twice as like as a migrants to be female (27% versus 15%) or speak English (40% versus 20%). Migrants are younger than non-migrants. Migrants are less likely than non-migrants to speak English, live with their family in the United States, or have a U.S. home.

In the 2000s, in large part due to the governmental and economic changes, the composition of the hired agricultural work force has changed. Among other changes, these workers are now older, wealthier, more likely to be female, and more likely to live with their families in a U.S. home. Because of these and other demographic changes, a smaller share is willing to migrate than in the past.

According to our statistical analysis, one-third of the reduction in migration rates was due to demographic changes, while the remaining two-thirds was the result of governmental and economic changes.

Farmers have responded to the reduction of migrants in several ways, they have changed cropping patterns, worked harder to retain workers, made jobs more attractive to female workers, adopted labor-saving technologies, and increasingly turned to guest worker programs. During this time, the number of agricultural guest workers more than doubled from 20,192 in 1998, to 44,847 in 2009 and almost doubled again to 85,248 in 2012.

Because migrants play a crucial role in many labor-intensive, seasonal, agricultural crops, the dramatic decrease in migration rates significantly reduced the ability of agricultural labor market to respond to seasonal shifts in demand during the year. If the current downward trend of migration continues and no alternative supply (such as from a revised H-2A program or earned legalization program) becomes available, farmers will probably experience greater difficulty finding workers during planting and harvesting seasons.

Featured image credit: Agricultural work, by catkin. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Are migrant farm workers disappearing? appeared first on OUPblog.

February 25, 2015

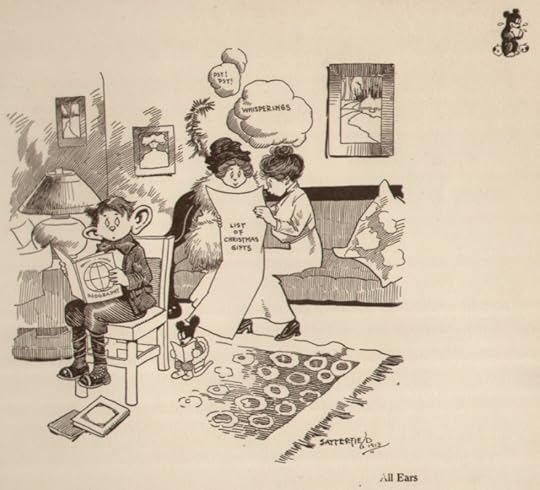

Monthly etymology gleanings for February 2015

One month is unlike another. Sometimes I receive many letters and many comments; then lean months may follow. February produced a good harvest (“February fill the dyke,” as they used to say), and I can glean a bagful. Perhaps I should choose a special title for my gleanings: “I Am All Ears” or something like it. Unfortunately, every good title, witty pun, and memorable rhyme, including The Importance of Being Earnest and intellectual / hen pecked you all, has already been used by others. Perhaps my “ears” have also occurred to some gleaner more than a hundred years ago. I did not check.

House between Germanic and SlavicHow do we know that Slavic borrowed Germanic hus (long u, that is, a vowel of Modern Engl. boo, coo, woo), the older form of house, rather than the other way around? Could hus be a loanword from Slavic? The situation is apparently so obvious that no one found it necessary to discuss it, not even A. Stender-Petersen, the author of the old but still most useful book Slavisch-germanische Lehnwortkunde (1927). The same holds for the etymological dictionaries of Slavic and Germanic I have consulted. At best, they say: “The word was borrowed by Slavic.” This omission is irritating. I think the reason for the universally shared conclusion is of phonetic nature. Contrary to Slavic, all the Old Germanic languages have the same old form (hus). It is easy to show how, with regard to the vowel and the consonants, Polish, Russian, and other Slavic languages modified hus, but reconstructing the early Slavic protoform that was supposedly taken over by Germanic would pose a nearly insoluble problem. Also, the impression is that Germanic hus occurred earlier than its Slavic modifications.

Does French hameau have a suffix? I am all ears.

I am all ears. My statement that hameau does not have a suffix pertains to the modern form. Engl. hamlet has a pseudo-suffix: -let, as in ringlet or starlet, is a viable morpheme, but if we subtract the last three letters from hamlet, the stub will carry no meaning because hamlet is not a small ham. Nor would we have any luck with -et. But at least there is a feeling that hamlet contains two parts. The situation is familiar: some element (in the past, certainly a suffix) has attached itself to a sound complex that no longer has an independent existence. In Modern French hameau, there is not even anything to subtract. That is why I wrote that this word has no suffix. Its etymology is another matter, and I discussed it in my post.

Man, earth, world, and wormMost etymologists recognize the kinship between Latin homo “man” and humus “earth.” But the path from Latin vir “man” (a cognate of Old Engl. wer “man,” which is also the first element of Old Engl. weor-old “world”) to vermis “worm” (a cognate of worm) leads nowhere, because the root of the word for “worm” has been found in several verbs meaning “to turn” (one of them is Latin vertere, familiar to English speakers from revert, subvert, convert, verse, and others). Worms certainly wriggle (“turn”). (By the way, that is why the suggestion that squirm is a blend of some verb and worm looks plausible.)

Thresh versus thrash and thresholdIt is tempting to refer the difference between the vowels in thrash and thresh to dialectal differences. But, as noted in the previous post, almost identical doublets existed in Old English, and this fact complicates the picture. Reference to dialects does not absolve us from going further and formulating certain phonetic regularities. It appears that no line separates English dialects with e preserved and e broadened before r. The case of marry, merry, and Mary in some varieties of American speech is irrelevant to thresh ~ thrash: there the three words have merged, while here the difference has been retained.

The importance of the threshold in various superstitions is a well-known and well-understood phenomenon, but the word seems to have been coined in a secular context. German Kobold, meaning “goblin” and sounding very much like goblin (a word cited by the same correspondent who offered his comments on threshold), does not seem to have anything to do with cave.

The initial group dw- in EnglishInitial dw- indeed occurs in very few English words, and I mentioned this circumstance in my dictionary (the entry dwarf). Such gaps are always puzzling. Initial tw-, outside expressive or sound symbolic words like tweak, twitch, can be found almost exclusively in the words related to two (twin, twist, etc.) No English word begins with tl, though speakers have no trouble pronouncing little. In Russian, only two words begin with tl-. No one has been able to explain why in English kn- and gn- were simplified to n (knock, gnaw), while elsewhere in Germanic those groups do reasonably well. Phonotactics (the branch of phonetics dealing with the distribution of sounds) is full of such capricious rules.

Slavic mirFrom an etymological point of view, Slavic mir “world” and mir “peace” are indeed the same word. Mir meant “community” (a sense still understood in Russian: compare, among others, phrases like vsem mirom “all together”). Living with those belonging to one’s own group promised peace. Later the word split into two. In Russian, for some time, they even had different shapes on paper: mir “world, cosmos” was at some time spelled with the roman letter (that is i) in the middle. A careless typesetter printed the second noun in the title of Tolstoy’s novel War and Peace with this i, a mistake that gave the publisher much trouble and resulted in a long, useless discussion about Tolstoy’s intentions. Did he mean War and the World? No, he did not. The best work on the etymology of Indo-European words for “peace” is still Karl Brugmann’s monograph.

Unrelated WordsCan host and guest go back to the root of Latin os “mouth”? From what we know about those words, no connection between host and os can be established. Similarly, os has nothing to do with the place name Hastings, which goes back to a tribal name. In host and Hastings, initial h is an integral part of their roots, while os never had the form hos.

Nor do the verb be, even though spelled bee in some early texts, and the noun bee go back to the same source. It is usually believed that the original meaning of be was “to grow” or “to become” and that of bee “trembling (insect),” from the movement of the creature’s wings. (Worms turn, bees quiver, and so it goes.)

I’ll now quote the beginning of a letter I received more than a year ago:

“I found it funny that the word for ‘food’ in Italian is like an exact description of where it comes from …ci in cibo [may] come from Greek gi for ‘earth’ and bo is a kind of being like a shortened bero for ‘borne’. So food being what grows from the earth, ‘earthborne’ [sic].”

The writer continues with a long list of similar hypotheses. This is the way some people tried to discover word origins in the Middle Ages. Since that time linguists have developed a more reliable method of treating their material. In etymology, ingenious speculation, unsupported by method, seldom results in viable conjectures. I can suggest to our correspondent that, whenever he feels an interest in such matters, he make use of some good dictionary. The answer given there may not be fully convincing, it may even say only “origin unknown,” but at least it won’t offer a fanciful guess.

Spelling bee, the bane of our being. A Note on Spelling and Spelling Reform

Spelling bee, the bane of our being. A Note on Spelling and Spelling Reform I agree that a good deal in the spelling of English makes sense from a historical point of view, but this is exactly the point. Like many people in my profession, I am conservative when it comes to usage, that is, I accept the fact that Old English became Middle English and study both periods with great pleasure, but I don’t want Modern English to become Postmodern and wince at he has showed (though American dictionaries say that the past participle showed is a legitimate competitor of shown) and keep saying sneaked for snuck. But in spelling loyalty to tradition is (even in my view) detrimental, the more so as tradition does not always deserve admiration. I see no sense in spell versus dispel, till versus until, full versus the suffix -ful, and even in all versus always and also.

Valerie Yule’s list of 38 very common words that cry out for change is excellent, but we need a more systematic approach to the reform. That is why I would support regularizing the use of double letters, abrogating x and q, as well as the digraph ph, and so on. (Apophthegm is not my favorite English word, though I have nothing against it in Greek.) However, my approach is opportunistic. I will accept any version of the reform the public will agree to instil(l). Certain things will be impossible to implement, for instance, “phonics” or the introduction of diacritics for sh, and ch, however reasonable their introduction may be. I see no point in fighting a battle we are sure to lose despite my acceptance of Cyrano’s aphorism (“aforism”): “One does not always fight to win.” As regards the causes of our erratic rules, see the comments by Masha Bell. Something could be added to her points, but for initial orientation her list will suffice.

Image credits: (1) A child listens discreetly as his mother and her friend discuss Christmas presents, 1913. Cartoon by Bob Satterfield. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) National Spelling Bee. Photo by erin m. CC BY-NC 2.0 via erin_m Flickr.

The post Monthly etymology gleanings for February 2015 appeared first on OUPblog.

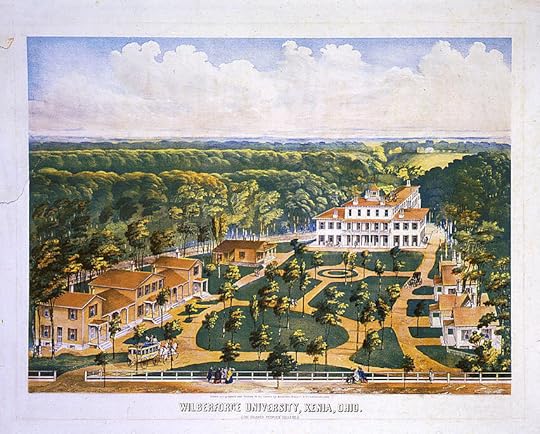

Wilberforce University: a pioneering institution in African American education

What do opera singer Leontyne Price, activist Victoria Gray Adams, civil rights organizer Bayard Rustin, and Harvard sociologist William Julius Wilson have in common? They all attended or graduated from Wilberforce University. Located outside of Dayton, Ohio, Wilberforce was the first institution of higher education to be owned and operated by African Americans.

As we celebrate Black History Month, it is fitting to examine one of the oldest historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) in the United States as a way to commemorate more broadly the achievements of African Americans. When Carter G. Woodson established Negro History Week (the precursor to Black History Month) in 1926, he aimed to shift the traditional focus on great men to a celebration of a great race. Woodson announced that the second week of February, when black communities typically commemorated the births of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, would be an opportunity to recognize less well-known individuals and events.

The history of black education in the United States illustrates African American advancement. Before and after Emancipation, black men and women pooled their meager resources and built schools because they recognized education as a key to a larger world and freedom itself. African Americans established over 100 HBCUs in the United States, often with the assistance of northern religious groups. While most of these institutions were founded after the Civil War, the Institute of Colored Youth (present-day Cheyney University), Lincoln University of Pennsylvania, and Wilberforce University opened before 1865.

The Methodist Episcopal Church and the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church joined forces in 1856 to provide African Americans with post-secondary education. The collaborators named the college Wilberforce in memory of William Wilberforce, a British statesman who had worked to abolish the slave trade in the British empire during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. By 1860, Wilberforce University had more than 200 students, most of whom were the mixed-race sons and daughters of southern white planters. The institution’s early success, however, faltered during the Civil War as student enrollment and financial support decreased significantly. Wilberforce closed its doors in 1862.

Wilberforce University, Xenia, Ohio. Public Domain via Library of Congress.

Wilberforce University, Xenia, Ohio. Public Domain via Library of Congress. Understanding the importance of education to the destiny of African descended people, the AME Church refused to give up on Wilberforce. Bishop Daniel A. Payne and countless other unnamed members of the first black independent denomination in the United States purchased the Wilberforce property in 1863. In later years, the AME Church established several other colleges including Allen University, Morris Brown College, and Paul Quinn College. When Wilberforce reopened under complete AME control, Bishop Payne served as president. He became the first African American to lead a university, doing so at a time when many white Americans questioned racial equality. Payne’s successors as Wilberforce’s chief leader include renowned historian Charles H. Wesley and congressman Floyd Flake (D-NY).

During the nineteenth century, Wilberforce taught its students Greek, Latin, and science, demonstrating the intellectual potential of black Americans. The university also established a theology department in 1866 to train black ministers as spiritual leaders and agents of social change. The department became the autonomous Payne Theological Seminary in 1891.

Payne Theological Seminary is not the only institution whose roots can be traced to Wilberforce. The Ohio General Assembly established a Combined Normal and Industrial Department at Wilberforce in 1887, granting the institution both denominational and public financial support. The state-sponsored department provided teacher training and vocational education. In 1947, the department formally separated from Wilberforce and became what is presently known as Central State University.

Some of the most distinguished black intellectuals who dedicated their lives to helping African Americans secure full freedom served on Wilberforce’s faculty. W.E.B. DuBois, Mary Church Terrell, William Scarborough, and Anna Julia Cooper taught at the institution. Benjamin O. Davis, Sr., the first African American general of the United States Army, was Professor of Military Science for several years in Wilberforce’s military training program, the first of its kind at an HBCU.

Today, Wilberforce is a four-year, fully accredited liberal arts institution. The university is a member of the United Negro College Fund, a philanthropic organization that provides scholarship funds to forty private HBCUs. Like many other black colleges, Wilberforce has faced significant challenges in the twenty-first century. The institution’s main issues are lack of funding and declining student enrollment. Yet, Wilberforce’s doors remain open. The steely determination that led AME Church members to revive the institution in the midst of Civil War continues to live on.

Wilberforce’s history illustrates Carter G. Woodson’s assertion that black history is more than the study of great men. It is and should always be the study of collective achievement and strivings of African-descended people. Wilberforce has persevered through slavery, segregation, poverty, and persistent racial discrimination. Its graduates have influenced the social, political, cultural and economic structures of the United States and world. May we all celebrate this pioneering institution and the role it has played in making our nation a more inclusive and advanced society.

The post Wilberforce University: a pioneering institution in African American education appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers