Oxford University Press's Blog, page 696

February 23, 2015

Is Broadchurch a classic crime drama?

January saw the critically acclaimed and award winning Broadchurch return to our TV screens for a second series. There was a publicity blackout in an attempt to prevent spoilers or leaks; TV critics were not sent the usual preview DVDs. The opening episode sees Joe Miller plead not guilty to the murder of Danny Latimer, a shock as the previous season’s finale ended with his admission of guilt. The change of plea means that the programme shifts from police procedural to courtroom drama — both staples of the TV schedules. Witnesses have to give evidence, new information is revealed through cross-examination, and old scores settled by witnesses and barristers.

The Sandbrook case, which featured marginally in the first series chiefly as a device to explain DI Hardy’s (David Tennant) arrival at Broadchurch, now takes centre stage alongside the trial. This case revolves around the murder and disappearance of two cousins. Hardy found the body of the younger cousin, aged twelve, but the body of the second girl was never found. For some viewers, the Sandbrook case is less plausible than the murder of Danny Latimer but as a plot device it functions as a classic crime drama case that ‘got away’.

Sandbrook haunts DI Hardy for several reasons. He found the murdered girl who was the same age as his daughter — identification with a child victim is another typical plot device — and the man he thought was guilty walked free. He was professionally ridiculed for his failures in the national press. It is the case that broke him and almost literally it broke his heart — in this series we see him undergo a heart operation to have a pacemaker fitted. These murders are the case he can’t (and won’t) let go of, and one that he continues to illegally investigate. In this respect he is the classic maverick cop, sidestepping lawful and organizational boundaries to get to the truth. It is presented as a noble quest to amend for his previous failures and redeem himself but his actions could potentially lead to his own downfall.

Hardy’s sidekick DS Miller (Olivie Coleman) is equally seeking redemption for very different reasons. Married to the killer, the new series finds her completely ostracized from her community. Like many women in this situation, she is guilty by association. Although the earlier unmasking of her guilty husband shocked everyone in Broadchurch, there is an assumption that she must have known or suspected something. She has left her old job and home, and her eldest son Tom is refusing to live with her. The implication here is that all women know or should know what the man they are sleeping with, the father of their children, is capable of.

Broadchurch. © BBC America

Broadchurch. © BBC America

DS Miller is in a ‘no win’ situation. At the end of the first series she physically attacks her husband after she learns of his guilt, leading to his guilty plea being declared inadmissible evidence because of injuries sustained during her attack. This provokes Beth Latimer (Danny’s mother) to accuse DS Miller of deliberately hurting her husband to get him off the murder charge. There is also the consideration of her job: if she was a good police officer how did she miss the clues that her husband was a killer? A thread running through this series is that on some level, acknowledged or not, women always know.

Set in a fictional picturesque seaside town, Broadchurch has all the ingredients we love in a classic cop drama. Flawed, maverick, wounded in some way but essentially ‘good’ cops bringing killers to justice. Unlike some recent portrayals of cops on TV, Miller and Hardy do not seek solace in alcohol; giving too much to the job has not damaged their relationships. But essentially, the job remains the source of their damage and to some extent their downfall. Hardy’s professionalism has been questioned, his health damaged, and his marriage ended because of the Sandbrook murders. Miller’s emotional fragility stems from her husband’s guilt and self-blame, leading to her multiple losses as a police officer, wife, and mother. Ultimately, like most good dramas, Broadchurch succeeds through a plot revolved around relationships, love, loss, redemption, and a good cliffhanger.

The post Is Broadchurch a classic crime drama? appeared first on OUPblog.

Trains of thought: Sarah

Tetralogue by Timothy Williamson is a philosophy book for the commuter age. In a tradition going back to Plato, Timothy Williamson uses a fictional conversation to explore questions about truth and falsity, knowledge and belief. Four people with radically different outlooks on the world meet on a train and start talking about what they believe. Their conversation varies from cool logical reasoning to heated personal confrontation. Each starts off convinced that he or she is right, but then doubts creep in. During February, we will be posting a series of extracts that cover the viewpoints of all four characters in Tetralogue. What follows is an extract exploring Sarah’s perspective.

Sarah is busy with a scientific solution to every problem, and quite willing to change her mind. She clashes violently with Roxanna, and finds Zac and Bob frustrating, but is willing to keep talking until one side is proven right (preferably hers).

Sarah: Did you see that woman? The one in lurid pink. She slapped her little boy, quite hard, just because he was crying. I’ve a good mind to report her. Look! She’s done it again.

Bob: My mum often slapped me, when I got too much for her. It never did me any harm. I preferred being slapped to when she was angry with me in a cold, silent way.

Zac: Times have changed, Bob.

Sarah: It’s outrageous to use violence on a child. The social services should intervene.

Bob: And take her son into care?

Sarah: If necessary.

Bob: That would be much worse for him than being looked after by his own mum and getting a few slaps.

Sarah: How can you be so complacent, Bob? That child is being physically and psychologically hurt in front our eyes.

Bob: He looks happy enough now, playing.

Sarah: You have no idea of the long-term effects. That child may be damaged for life.

Bob: Like me?

Sarah: You might not have needed to take refuge in absurd superstitions if your mother hadn’t abused you.

Bob: It wasn’t abuse, just slapping.

Sarah: Slapping is abuse, Bob. If I slapped you right now, which I almost feel like doing just to make you see sense, I could be prosecuted for assault. Defenceless children deserve to be protected at least as much as adults are by law, especially when their attackers are the very people who are supposed to be protecting them.

Bob: You keep saying we must be scientific about everything. What’s the scientific evidence for your ideas about slapping, then?

Sarah: I’m sure there’s plenty of statistical evidence for the damaging long-term effects of hitting children.

Bob: You mean you don’t know of any, you’re just sure there is some. Anyway, parents have the right to bring up their children as they see fit. They know best what their children need.

Sarah: Not always. That woman clearly doesn’t. Some parents kill their own children. Is that knowing best what they need?

Bob: Killing a child isn’t bringing it up. Anyway, I wasn’t talking about mad parents. I meant normal parents. That woman down the carriage isn’t mad, just tired and fed up, with a whining brat to look after all the time. Normal parents have the right to bring up their children as they see fit.

Sarah: Even if their methods are scientifically proven to harm children?

Bob: It’s not some scientist’s right to decide how that boy should be looked after. It’s his mum’s right. Whether she brings him up on scientific advice is up to her. Sometimes a good old-fashioned cuff round the ear is just what a boy needs.

Sarah: I don’t believe she has any idea what the scientific advice is.

Bob: Well, go and tell her then, if you’re so worked up about it.

Sarah: I will do exactly that. Someone needs to take some action.

Zac: Are you sure that’s wise, Sarah? . . . Too late.

Bob: I didn’t think she’d take what I said seriously. She puts her money where her mouth is, our action woman Sarah. She’s talking to that woman now. It’s so noisy, I can’t hear what they’re saying. Can you, Zac?

Zac: No, I can’t. Bob, perhaps you should be more careful about provoking Sarah.

Bob: I know, she takes everything so seriously. I can’t quite see what’s happening. . . . Ah, she’s coming back. What did she say, Sarah?

Sarah: I could only make out half her words. Most of those were obscenities I’d rather not repeat.

Bob: Did her boy say anything?

Sarah: He started to cry again. Then she threatened to set the police on me, for upsetting him—I could make that much out. There was no point continuing.

Bob: There was no point starting.

Sarah: The whole incident simply confirms my suspicion. The child should be taken into care.

Bob: Is that what science tells you, or are you just cross with her for swearing at you?

Sarah: You’re right, I must be careful not to lose my objectivity. But I objected to her slapping him even before I went and talked to her.

Bob: She had a moral right to slap him, whatever the law says. None of your science can prove otherwise.

Sarah: It can prove the damaging long-term effects of parental violence on the health and happiness of children.

Bob: I’m talking about a mother’s right. She has the right to use her own judgement in bringing up her child.

Sarah: Not when her own judgement manifests so much ignorance and stupidity.

Bob: She had a right to slap him!

Sarah: You’re wrong, she had no right!

Zac: Bob and Sarah, this is where I came in. You’re deadlocked again.

Roxana: What does Sarah’s science say about moral rights?

Sarah: Well, ‘moral right’ isn’t a scientific term. You can’t measure moral rights. But you can measure health, and even happiness. It would be more scientific to talk about them.

Bob: Don’t change the subject. I’m talking about a mother’s moral rights.

Sarah: That sort of emotive language gets us nowhere. To make progress in discussing children’s upbringing, we need to start using more factual vocabulary.

Bob: It’s a fact that a mother has a moral right to slap her child.

Sarah: Moral rights aren’t facts, they are matters of opinion. Matters of fact are the sort of thing that can be measured scientifically.

Roxana: Once scientists have made all their measurements, how do they decide what ought to be done?

Sarah: They recommend the option that maximizes probable health and happiness.

Roxana: They assume the moral theory that we ought to maximize probable health and happiness?

Sarah: What’s the alternative?

Roxana: There are infinitely many.

Zac: Sarah, health and happiness are not the only things a moral theory might say you ought to maximize. Some people say you ought to maximize total pleasure minus total pain.

Have you got something you want to say to Sarah? Do you agree or disagree with her? Tetralogue author Timothy Williamson will be getting into character and answering questions from Sarah’s perspective via @TetralogueBook on Friday 29th March from 2-3pm GMT. Tweet your questions to him and wait for Sarah’s response!

The post Trains of thought: Sarah appeared first on OUPblog.

February 22, 2015

The audience screams; people duck

Millions of Americans are eagerly anticipating this year’s Academy Awards ceremony. For over a century, motion pictures have been a dominant cultural and leisure medium. There are, however, two aspects worth highlighting: the sheer novelty of motion pictures and the medium’s initial democratic nature.

Twenty-first century Americans have difficulty imagining the wonder and awe motion pictures inspired in the early 1900s. To simply see people running, jumping, and cavorting on a screen was mesmerizing. There is a wonderful scene in The Grey Fox, a movie about aging stagecoach robber Bill Miner. Upon release from the penitentiary, he wanders into a storefront theater. The theater is showing Edwin Stanton Porter’s The Great Train Robbery. At the end of the short film, a character points his revolver at the camera and fires. The audience screams; people duck. Bill Miner, stunned at first, realizes what has happened and begins to clap enthusiastically. Today’s audience would find little drama in the scene and it’s unlikely that anyone would duck. Motion picture technology has advanced so rapidly and so amazingly that it is hard to imagine what would spur today’s audience to similar reactions.

Another easily neglected aspect of motion pictures is the surprisingly democratic nature of the American movie industry in its initial stages. Although Thomas Edison hoped motion pictures would promote high culture, he completely misread the public’s use of the technology. Crowds of Americans, including many immigrants, flocked to converted storefronts serving as theaters, where they sat in a motley of chairs watching images flicker on a makeshift screen. Upper-crust Americans shuddered with disapproval at the spectacle of men, women, and children huddling in darkened rooms watching the films.

Staid Americans hoped motion pictures would be a passing fad, destined to fade away. When this hope proved stillborn, these Americans sought to repress motion pictures or at least cleanse the movies’ contents. In 1896, an obscure short film—all of forty-seven seconds long—descriptively titled The Kiss, showed May Irwin and John Rice, stage musical performers, recreating their stage kiss. Although audiences had seen performers kiss live on stage, the spectacle of seeing such activity on a large screen prompted one critic to complain,

“Neither participant is physically attractive, and the spectacle of the prolonged pasturing on each other’s lips was hard to bear. When only life size it was pronounced beastly. But that was nothing to the present sight. Magnified to gargantuan proportions and repeated three times over it is absolutely disgusting….The Irwin kiss is no more than a lyric of the Stockyards.”

The critic, by calling it the Irwin kiss, leaves no doubt as to whom he blamed for the scandal, although obviously it took two to kiss. A century later, Americans still debate the morality depicted in motion pictures. Movie kisses, however, remain crowd-pleasing.

Image still from “The Kiss” by Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image still from “The Kiss” by Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The industry was also initially democratic on the production side. Because the industry was new and only required modest amounts of capital to set up primitive theaters or to produce simple films, even recent immigrants could enter the industry and eventually gain dominance; the Warner brothers and Louis B. Mayer exemplified this phenomenon. The story of the five Warner brothers pooling their meager funds to purchase a projector and renting space to show films is an embodiment of the American Dream.

Unfortunately, there were dark sides to these rags-to-riches tales. Motion picture moguls, as people dubbed them, proved ruthless, tying actors to long-term, one-sided contracts similar to those imposed on baseball players. Although prominent actors made much greater incomes than the average American—and the motion picture executives made sure the public was well informed of such—actors were exploited economically because they were tied to a single studio and could not seek bids from other studios. What the motion picture moguls did to the most prominent of their employees, they did to the unsung. Motion picture crews formed unions to gain bargaining leverage, but the industry was not known for good treatment of its workers.

The motion picture executives, appearing just after the apogee of the titans of industry—men such as Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, J.P. Morgan—emulated their formation of industry concentration. By the 1920s, the industry was in the hands of a few companies. Even the much bally-hooed morality codes played into the hands of the major studios. Smaller independent studios might have hoped to gain an entrance into the industry by showing daring topics or actions, but the morality codes squelched such efforts.

A century on, motion pictures remain popular with Americans. The glamorous aspects of the industry often camouflage the raucous history of the medium, but the history is, in many ways, more interesting than the legend.

Image Credit: “Film Reels” by Global Panorama. CC by SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The audience screams; people duck appeared first on OUPblog.

The neuroscience of cinema

Why do we flinch when Rocky takes a punch in Sylvester Stallone’s movies, duck when the jet careens towards the tower in Airplane, and tap our toes to the dance numbers in Chicago or Moulin Rouge? With this year’s Academy Awards upon us, we want to know what happens between your ears when you sit down in the theatre and the lights go out. Take a look at some of the ways our brains work when watching a movie—you may just find some of them to be all too familiar.

What was the last movie that made you jump, cry, or laugh out loud? Let us know in the comments below.

Headline image credit: Warren G. Harding, movie operator. Library of Congress.

The post The neuroscience of cinema appeared first on OUPblog.

What Pakistan’s history means for its future

The story of Pakistan is the story of missed opportunity. As I began to write about the history of this land, I could not help feeling a sense of an intertwining of personal and national destiny in what was necessarily an account of my own missed opportunities, and those of my country, making me record an anecdotal account of events as l experienced them over the last forty years. The narrative that l have recorded may have interest for people living in Pakistan, the Pakistani diaspora, and among foreigners who follow and seek to understand South Asian issues.

My political journey started during the Z. A. Bhutto years, when Pakistan had been truncated, after the loss of East Pakistan. Bhutto struggled to modernize Pakistan on the one hand, while sinking it into a quagmire of controversies on the other, during the course of his five years in power. His unquestionable brilliance made him not just the voice of the downtrodden in our country but also the spokesman of the entire Muslim world. However, the Establishment in Pakistan blamed him for the loss of East Pakistan, which eventually led him to the gallows. His successor in power General Zia ul Haq, failed to prevent us from becoming embroiled in conflict in Afghanistan, which, had it been avoided, may have spared us from becoming entangled in religious conflicts and controversies that continue to engulf us right up until today.

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. National Dutch Archives. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. National Dutch Archives. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.With the end of the Cold War and the disappearance of Zia ul Haq, after eleven years in power, Pakistan obtained the gift of democracy, personified by Bhutto’s glamorous daughter Benazir, while our now wary Establishment anointed Nawaz Sharif as a counter. The pendulum of power swung, twice over, between these two young leaders after roughly every two and a half years, which came to represent Pakistan’s lost decade. During this period, democracy appeared to fail and economic failure seemed to rise, alongside of a creeping religious extremism, which started in Zia’s time but which, both Benazir, as well as Nawaz, did not succeed in reigning in.

Ousted by General Parvez Musharaf, Nawaz became recipient of hospitality from the House of Saud at Jeddah, while Benazir self-exiled to Dubai, allowing Musharaf a free hand to steer Pakistan out of stormy waters. But Musharaf, according to many, was simply not the stuff that able helms men are made of. When asked his opinion about the General who had assumed power in Pakistan, George W. Bush, who a year later was elected President of the United States, said “I don’t know the guy’s name, but I know he is on our side.” Post 9/11, Musharraf became a crucial US ally, yet he failed to serve American as well as Pakistani interests adequately. Religious extremism increased greatly and the War on Terror came to be hopelessly bogged down. Musharraf, by and large, relinquished power leaving Pakistan in a worse state than when he had assumed his role as dictator, nine years earlier.

Almost from the outset in my country, State power has been exercised in a manner that ultimately served to erode it. Greater caution and lesser commitment to power as an end in itself might have helped reduce our involvement in the ‘Great Game’ that has been played to the North West of our country, where extremism and militancy have loomed large on the landscape. As a result thereof we came to be immersed in an intolerant version of religion,with our credo, which stands for peace, almost reversing as it encountered increasing levels of violence, and brutality.

In the face of depressing realities, most Pakistanis nonetheless remain committed to the goal of achieving a balanced State, which enshrines the values for which our country was created. We may have suffered power failure in our past but our future holds promise, in view of our vibrant and well informed younger generation, who are better prepared as they appear on the anvil of moving into positions of decision making and power.

Headline image credit: Dome of Main Hall by Adeel Anwer. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post What Pakistan’s history means for its future appeared first on OUPblog.

An A-Z of the Academy Awards

After what feels like a year’s worth of buzz, publicity, predictions, and celebrity gossip, the 87th Academy Award ceremony is upon us. I dug into the entries available in the alphabetized categories of The Dictionary of Film Studies — and added some of my own trivia — to highlight 26 key concepts in the elements of cinema and the history surrounding the Oscars.

A – Academy AwardsAMPAS (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences) is an honorary professional organization set up in 1927 to provide a support network for industry professionals and as a way of promoting the US film industry.

Winners of Academy Awards receive a gold-plated, Art Deco-style, statuette of a male figure holding a sword and standing on a reel of film with five spokes said to represent actors, writers, directors, producers, and technicians, the predominant trades of AMPAS members in the 1920s.

The Academy Awards have also been the site of controversy: George C. Scott refused the Best Actor award in 1970 for Patton, stating, ‘The whole thing is a goddamn meat parade. I don’t want any part of it.’

B – BiopicA film that tells the story of the life of a real person, often a monarch, political leader, or artist. Popular candidates for Best Picture. Four of the 2015 Best Picture nominees (The Theory of Everything, The Imitation Game, Selma, and American Sniper) may be considered biopics.

C – CannesAn international film festival is held here each spring, during which time a number of films are screened on successive days. The Cannes Film Festival, founded in 1946, is the world’s best‐known festival, with a range of international films submitted for competition and screening.

Film festivals are a major marketplace for producers and distributors from around the world; many films are made with the explicit aim of being ‘discovered’ at a festival. Winners and nominees tend to be inspiration for Oscar nominations the following year.

D – DirectorArguably, one of the six top awards at the Academy Awards ceremony (the others being Best Actress, Best Actor, Best Supporting Actress, Best Supporting Actor, Best Picture). A director guides the creative and stylistic elements of the filmmaking process within an environment of skilled and talented collaborators. While direction plays a decisive role in the filmmaking process, the authority of the role is often overstated in popular culture (because films are promoted through named directors)

American film editor Thelma Schoonmaker at 2010 Karlovy Vary International Film Festival (2010). Photo by Petr Novák, Wikipedia. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. E – Editing

American film editor Thelma Schoonmaker at 2010 Karlovy Vary International Film Festival (2010). Photo by Petr Novák, Wikipedia. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. E – Editing An Academy Award for Editing honors the creative work beyond assembling the separate pieces of film. Editing is complex process informing decisions about what setups, shots, and scenes to shoot, and which of these will be included in the final film and in what order.

The work of editing has often been the province of women: Elisaveta Svilova edited Dziga Vertov’s films, for example, and Esfir Shub is known for documentary films composed almost wholly of intricately edited archival material. American editor Thelma Schoonmaker has worked with Martin Scorsese for over thirty-five years, receiving three Academy Awards for best editing for Raging Bull (1980), The Aviator (2004), and The Departed (2006).

The nominees for the 2015 Academy Award for Best Film Editing include American Sniper (Joel Cox and Gary D. Roach), Boyhood (Sandra Adair), The Grand Budapest Hotel (Barney Pilling), The Imitation Game (William Goldenberg), and Whiplash (Tom Cross).

F — Foreign FilmNon-Hollywood, or non-Western, or non-mainstream films. While some non-US films have been nominated for Best Picture in the past (e.g. 2008’s Slumdog Millionaire by Danny Boyle), most nominees fall into the Foreign Film category. A good deal of recent and current work in this area focuses on China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Japan, and South Korea, whose cinemas have become increasingly visible and popular in the West.

G – Gangster FilmAspects of the gangster film surface in Hollywood genres of the 1940s and 1950s and continued to be made into the 1960s. A few notable films that fell into this category, including Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967) and Francis Ford Coppola’s Godfather trilogy (1972–90), received immense critical acclaim leading to Academy Award nominations and wins.

H – Hollywood A district of Los Angeles, California with historical and continued associations with the US film industry A general term denoting the entire phenomenon of popular entertainment cinema, or a synonym for the film industry, in the US.The Academy Awards ceremony has always been held in Los Angeles. Bollywood (Bombay + Hollywood) and Nollywood (Nigeria + Hollywood) describe the cinemas of India and Nigeria respectively and produce a tremendous number of films every year.

I — Independent CinemaInitially, only a small number of “independent films” experienced the kind of Academy Award success of Hollywood’s big budget films. But a number of well-known, award-winning US directors have made the move from independent films to semi-independent: David Lynch, Spike Lee, and Richard Linklater, whose Boyhood is nominated for several Academy Awards this year, for example. Indeed, Woody Allen, one of the US’s best-known directors, has made over 40 independent features since the late 1960s.

Red carpet at 81st Annual Academy Awards in Kodak Theatre, Los Angeles (2009). Photo by Greg in Hollywood (Greg Hernandez). CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. J — Journalism

Red carpet at 81st Annual Academy Awards in Kodak Theatre, Los Angeles (2009). Photo by Greg in Hollywood (Greg Hernandez). CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. J — Journalism Pejoratively, a form of entertainment that reports the sensational or lurid aspects of news and also gossip about celebrities (see also sensationalism). An unfortunate but prevalent part of the Academy Award hype, particularly in terms of coverage of Red Carpet Fashions.

K — Kung FuThe martial arts film has long attracted audiences worldwide and exerted influence on the cinemas of other countries. Most recently, the Matrix franchise (Larry and Andy Wachowski, 1999–2003) employed Hong Kong martial artist Yuen Wo Ping to choreograph its many action sequences. The Best Picture winner in 2000, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (Ang Lee, 2000) is a self-conscious return to the wu xia origins of the genre.

L — Literary AdaptationA pre-existing work, often literary or theatrical, that has been made into a film. More commercial properties such as musical theatre, best-selling fiction and non-fiction, comic books, and so on, are also regularly adapted for the cinema.

It is claimed that adaptations account for up to 50% of all Hollywood films and are consistently rated amongst the highest grossing at the box office, as aptly demonstrated by the commercial success of recent adaptations of the novels of J.R.R. Tolkien. The top screenplays based off of a previously published work are honored with a Best Adapted Screenplay nomination. 2015 nominees include American Sniper, The Imitation Game, Inherent Vice, The Theory of Everything, and Whiplash.

M – MusicA central component of a film’s soundtrack, including the score and any other musical elements. While there is not explicitly an Academy Award for “soundtrack” the Best Song category has drawn attention in recent years.

From the late 1970s it became common to appoint a music supervisor to handle the placement and copyright clearance of licensed music, as, for example, with music producer Phil Ramone’s work on Flashdance (Adrian Lyne, 1983).

N — New HollywoodBonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967) and Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper, 1969) are important films in marking Hollywood’s new direction. Both achieved box-office success (and Oscar nods) by disregarding stylistic convention, showing characters rebelling against the mainstream, refusing happy endings, and harnessing the sensationalism of the exploitation film.

During this period, a new generation of creative talent entered the industry, including such directors as Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, William Friedkin, Paul Schrader, and Terrence Malick. These directors, along with rising actors such as Robert De Niro, Al Pacino, Warren Beatty, and Jane Fonda, appealed to the youth audience. All have been recognized by the Academy over the course of their careers.

CHICAGO – JANUARY 23: Oscar statuettes are displayed during an unveiling of the 50 Oscar statuettes to be awarded at the 76th Academy Awards ceremony January 23, 2004 at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, Illinois. The statuettes are made in Chicago by R.S. Owens and Company. (Photo by Tim Boyle) © EdStock via iStock. O — Oscar

CHICAGO – JANUARY 23: Oscar statuettes are displayed during an unveiling of the 50 Oscar statuettes to be awarded at the 76th Academy Awards ceremony January 23, 2004 at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, Illinois. The statuettes are made in Chicago by R.S. Owens and Company. (Photo by Tim Boyle) © EdStock via iStock. O — Oscar The Oscars are an informal name for Academy Award statuettes, prizes awarded annually for services to the cinema by the US Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. The award ceremony is held in the spring following the relevant year. The gold-plated bronze statuettes stand 25cm (13.5in) high.

Why is it called an “Oscar”? There are some speculations…

P — PerformanceA term commonly used to describe the work of acting, with the actor or the film star said to have given a remarkable performance, for example. A Best Actor and Actress announcement is described as “the best performance by an actress in a leading role.” Among 2015’s nominees, Eddie Redmayne and Julianne Moore are tipped to win on Sunday.

Q — Queer CinemaThe term, conceived initially in film studies scholarship, has extended to more mainstream films, such as The Adventures of Priscilla Queen of the Desert (Stephan Elliot, Australia/UK, 1994), Boys Don’t Cry (Kimberley Peirce, US, 1999), Far from Heaven (Todd Haynes, US, 2002), and Ang Lee’s highly successful queer western, Brokeback Mountain (US, 2005). All of these films have received recognition from the Academy.

R — Release StrategyThe way in which a distributor chooses to ‘open’ a film, i.e. make it available to the audience. Based on the Summer Blockbuster successes, and the December 31 deadline for Feature film Academy Award nominations, the Fall and Winter tend to be seasons when “Oscar hopefuls” are released.

S — Short FilmA broad category of films defined by their short running time in comparison with that of the feature film. For the purposes of the ‘Animated Short Film’ and ‘Live Action Short Film’ categories in the Academy Awards, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences defines a short film as 40 minutes or less.

Filmmakers working in the short film format generally rely on competitions and film festivals to get their work seen.

T — TitanicNominated for 14 and winning 11, Titanic made Oscar History at the 1997 ceremony. Everything in director James Cameron’s previous career has now been surpassed by the extraordinary tour-de-force of Titanic (1997), which set a new budget record, proved cinema’s biggest ever success at the box office, and won eleven Oscars, thereby equalling the record of Ben Hur in 1960.

U — US FilmIn the 2010s Hollywood continues to dominate cinema screens worldwide and remains an avowedly commercial cinema now geared to the production of high concept blockbuster films designed to exploit multimedia platforms and sell through to global markets.

Many of the major studios have also set up semi-independent production companies that provide a space for directors such as Quentin Tarantino, David Fincher, Paul Thomas Anderson, and the Coen Brothers to make challenging films with mid-range budgets. These films are popular contenders for Oscar nominations which drives publicity and ticket sales.

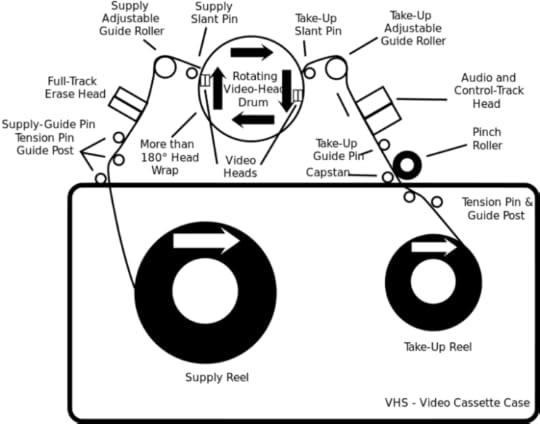

Diagram of a VHS tape. Image by Asenine; derivative of work by StG1990. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. V — VHS

Diagram of a VHS tape. Image by Asenine; derivative of work by StG1990. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. V — VHS The creation of VHS lead to increased awareness on a global scale of the films nominated for awards. In the 1980s, the adoption and use of this home video technology became widespread. VCRs had a significant impact on the ways films were viewed: films broadcast on television could be recorded and viewed at a later date, for example, and films could be rented or purchased for home viewing.

W — Women and FilmOnly four female directors have been nominated for Best Director. Most recently, The Hurt Locker (Kathryn Bigelow, 2009) won Best Picture, but Bigelow lost to Danny Boyle.

In 2015, Daisy Jacobs, director of The Bigger Picture, is nominated for Short Film – Animated.

X — X-Rated FilmIn 1990, the MPAA introduced NC-17 in an attempt to reduce the stigma attached to the X rating, which had been in use since 1968 and which for many had become synonymous with pornography. Distributors of X-rated titles, including non-pornographic films such as Midnight Cowboy (John Schlesinger, 1969), could not secure advertising on television or in the popular press. Midnight Cowboy remains the only X-rated film to ever win Best Picture.

Y — Yes, But Also…In all this talk about Hollywood commercialism, it would be an oversight not to mention another mainstream cinema giant whose films have steadily trickled into the Academy Award nominee pool: Bollywood. Its influence is apparent in such recent western-made films as Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge (2001) and Danny Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire (2008).

Z — Zoom ShotA zoom in can be effective in rapidly and dramatically drawing the viewer into a scene or bringing the viewer’s attention to a detail; and a zoom out in revealing the background and the surroundings of a character or activity. Keep an eye out for these when the Oscar clips at the ceremony start rolling…

Headline image credit: CHICAGO – JANUARY 23: Oscar statuettes are displayed during an unveiling of the 50 Oscar statuettes to be awarded at the 76th Academy Awards ceremony January 23, 2004 at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, Illinois. The statuettes are made in Chicago by R.S. Owens and Company. (Photo by Tim Boyle) © EdStock via iStock.

The post An A-Z of the Academy Awards appeared first on OUPblog.

Mood food: a brief look at addictive eating

Researchers have noted that some addictive behaviours may partly depend upon gender. For instance, men are more likely to be addicted to drugs, gambling, and sex whereas women are more likely to suffer from ‘mall disorders’ such as eating and shopping. Food is – of course – a primary reward as it is necessary for our survival. However, it is this reward that gives highly palatable food (such as sugar) its addictive potential, leading to excessive eating as an addictive behaviour. Possible reasons behind such excessive eating in today’s society are many, including the increasing availability of food, a more inactive lifestyle, and financial considerations. Furthermore, as a means of mood enhancement, food is highly rewarding, easily available, low-cost, and most of all it is legal.

Such justifications demonstrate some degree of explanatory power, contributing to research into the topic of excessive eating as an area of increasing interest. However, no such explanations address the critical question of why certain people seem to overeat, despite repeated efforts not to. The majority of obese cases tend to result from an over-consumption of energy, independent from a lack of physical activity. Therefore it may be people, rather than food, that need to be the focus here.

Prevalence rates for excessive and addictive eating are highly variable. Past year prevalence rates of eating disorders (particularly binge eating disorder, among older teens and adults typically) varies between 1 to 2%, but much higher figures have been reported in a variety of studies in a number of different countries (between 6% and 15% depending upon the sample). Based on these studies (that included samples of at least 500 participants), Steve Sussman, Nadra Lisha, and I estimated a past year prevalence rate of 2% for eating addiction among general population US adults.

Reward sensitivity is one possible factor in excessive eating. A personality construct of Jeffrey Gray’s Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory, reward sensitivity is thought to control approach behaviour, by means of the dopamine reward centre. Individuals that are highly sensitive to reward are more prone to detect signals of reward in their environment (such as food) resulting in approaching these rewards more frequently, along with responding quicker and more strongly. Research demonstrates associations between reward sensitivity and increased food cravings, body weight, binge eating, and a preference for high fat food. Such findings offer a possible explanation for why only some individuals eat excessively when that reward is a process available to all.

Emotion is yet another possible factor. An excessive appetite for food has long been linked to emotional eating with research demonstrating that refined food addicts specifically report eating when they feel anxious. Research dating back to the early 1990s found that women being treated for eating disorders described feeling less anxious as an episode of binge eating went on. Such research suggests that highly anxious people are more likely to turn to food for comfort, leading to excessive eating, yet in turn cause themselves more anxiety when this comfort is unavailable. For instance, this is demonstrated in the eating habits of overweight Americans, revealing that women tend to binge eat when they feel lonely or depressed, while men overeat in positive social situations.

Moreover, research has shown that obese people score higher on impulsiveness personality scales. Impulsivity is a tendency to ‘act on the spur of the moment’, often associated with a failure to learn from negative experience, wherein individuals know the appropriate way to behave but fail to act accordingly. Refined food addicts eat for a ‘pick-me-up’, although they are aware that they are not hungry, suggesting a correlation between reward sensitivity and impulsive reactions to such reward cues. Impulsive individuals have a tendency to react to stress and anxiety, with a craving for immediate satisfaction as a form of relief. Although eating may deliver this reward or relief, it may then condition impulsive individuals to react quickly, with this inapt response, to such feelings in the future, such as with feelings of hunger when feeling anxious. This could explain why repeated attempts to restrict food intake and lose weight, so often results in relapse in obese people.

Associations have also been observed between self-esteem and a variety of excessive eating behaviour populations, such as restrained eaters, bulimic patients, and binge eaters. One explanation suggests that individuals with low self-esteem have lower expectations for personal performance, resulting in less effort being made to resist challenges and temptations to their diets. This offers another explanation that individuals with low self-esteem depend more on external cues to control eating, such as how food looks, rather than internal cues, such as hunger, indicating reward sensitivity and resulting in dieters with low self-esteem overeating. Here, low self-esteem combined with reward sensitivity and its further correlations to impulsivity and anxiety, seem to demonstrate a destructive model of influence on behaviour, one trait further amplifying the next leading to continuous eating to excess.

In relation to low self-esteem, low social desirability has been seen to correlate significantly with restrained eating in obese people. High social desirability is most commonly associated with a desire for thinness. Therefore, although an association with eating behaviour exists, high social desirability is more likely to correlate with anorexic behaviours as opposed to excessive eating. Low social desirability, combined with low self-esteem as a cause or effect, could contribute to explaining excessive eating in some individuals, which in turn could be reasoned by contributions of all traits previously mentioned.

Finally, Professor Elizabeth Hirschman at Rutgers University has proposed a general model of addictive consumption that interrelates excessive and compulsive consumption behaviour. This model suggests similar characteristics people exhibit, along with common causes, patterns of development, and the similar functions such behaviours serve for individuals. Many of these have been previously associated with excessive eating in particular, further suggesting a general consumption personality principle.

Headline image credit: Cakes. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Mood food: a brief look at addictive eating appeared first on OUPblog.

The philosophy of perception

Parmenides, in the Way of Mortal Opinion, envisions the sensible world to be governed by Fire and Night, understood as cosmic principles. As a consequence, Parmenides conceives of the colors as themselves mixtures of light and dark. Parmenides’ view, here, is in line with an ancient tradition dating back at least to Homeric times. In his notorious study, among the five “signs of the immaturity” of the Homeric color scheme, W.E. Gladstone cites the following: “The vast predominance of the most crude and elemental forms of colour, black and white, over every other, and the decided tendency to treat other colours as simply intermediate modes between these two extremes.” That Parmenides took the colors to be mixtures of light and dark places him squarely within this Homeric tradition. Gladstone took this perceived limitation to the Homeric color scheme to be evidence that the ancient Greeks were color blind. Ironically, Gladstone makes this diagnosis just as archaeological evidence was revealing ancient Greek statuary to be multi-colored. While Gladstone’s study played an important role in the development of ethnolinguistics, Gladstone’s skepticism is no longer widely shared.

One of the most important developments of 5th century BC painting, variously attributed to Apollodorus and Zeuxis, was the development of skiagraphia, shadow painting, or in modern parlance, chiaroscuro. In archaic Greek painting, figures appear outlined and uniformly colored in a two-dimensional pictorial plane. Moreover, the color of the figures tended to complement and support the overall two-dimensional composition. However, in the 5th century BC, the “shadow painters” came to emphasize, instead, lightness and darkness in organizing their compositions. There was less reliance on outlining, figures were no longer uniformly colored as primitive methods of shading were developed, and as a result, the figures began to emerge from the two-dimensional pictorial plane. To emphasize the importance of relative brightness in their composition, the shadow painters worked with a limited palette. Nevertheless, they were able to produce the appearance of a variety of colors by combining the colors of this limited palette.

An ancient viewer of skiagraphia, familiar with Parmenides’ poem, would have seen in these paintings the pictorial realization of Parmenides’ cosmology. Just as the combination of Fire and Night suffices to give rise to the colors of the sensible world, the shadow painters’ combination of light and dark pigments suffice to represent the colors encountered in the sensible world.

Acrylic spin painting, by Mark Chadwick, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr

Acrylic spin painting, by Mark Chadwick, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr These ideas and practices have a remarkable afterlife. In the development of modern chiaroscuro, Renaissance painters reconstructed the practice of skiagraphia from the writings of Pliny and Quintilian. (Alas, the paintings themselves have not survived the ravages of history.) Thus, for example, Titian uses Apollodrus’ four color palette in painting Christ Crowned with Thorns. And Goethe, in his Theory of Colors, will defend the ancient view as a means of attacking Newton’s own theory. White or light, instead of being mixed in various proportions to produce the chromatic hues, is conceived by Newton to be the mixture of all the spectral colors. Newton describes this as “the most Paradoxicall of all my assertions, & met with the most universall & obstinate Prejudice”. This paradoxical assertion is nothing less than the demolition of the explanatory framework of the ancient tradition, and it is this which most likely drew Goethe’s ire.

Newton’s own view, however, has not survived unscathed. Richard Sorabji writes:

“At Cornell, I had heard Edward Land, the inventor of the Polaroid camera, lecture on his discovery that Newton’s theory of colour is wrong. The eye responds not to absolute wavelengths of light, but to the more complicated property of reflectance, which involves the proportions among wavelengths in the available scene. Land was able to cast on the screen at Cornell a slide showing all the colours of the garden, yet he was using wavelengths only from within the yellow waveband.”

Many color realists these days follow Land in thinking of the colors as at least a construction from reflectances, a disposition to reflect a certain amount of light from each of the wavelengths of the visible spectrum. But reflectance theories, themselves, have an ancient heritage. Aristotle, like Parmenides, belongs to this Homeric tradition and inaugurates a certain genus about the metaphysics of color. In De Anima II 7. Aristotle defines colors as ways of affecting light. Only two claims separate a simple reflectance theory from Aristotle’s definition. The first claim is a specification. In maintaining that color is a disposition to reflect, transmit, or emit a certain amount of light, modern reflectance theories specifies the way in which color affects light—by reflection, transmission, or emission. Moreover, the amount of light reflected, transmitted, or emitted just is the mixture of light and dark.

The second claim is that there are different kinds of light. Newton recognized the necessity of distinguishing different kinds of light in the way that Aristotle did not. Though Goethe saw matters differently, the intrusion of the Newtonian distinction between kinds of light, while anachronistic, is nevertheless a consistent extension of Aristotle’s metaphysics. Conjoining the specification of Aristotle’s definition with the Newtonian extension just is a statement of a simple reflectance theory. That colors are ways of affecting light is an important genus in the metaphysics of color, one that Aristotle’s definition of color belongs to, and it is arguable that Aristotle inaugurates this metaphysical tradition.

The post The philosophy of perception appeared first on OUPblog.

February 21, 2015

Celebrating linguistic diversity on International Mother Language Day

It’s Thursday evening in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh. I am late for an appointment to see my friend Shimanto (lit. boundary [Sanskrit]). On the street I shout ‘ei mama jaben?’ (Hey uncle, will you go? [Bangla]) to catch an auto-rickshaw (auto [English] man-powered-wheeler [Japanese]). After striking the deal, I sit inside the three-wheeler. As the young driver speeds up almost hitting passers-by and curses ‘jyam khub kharap!’ (Traffic jam [English] is very bad! [Persian]), I recollect the writing at the back of the car: ‘allāḥ sarvaśaktimān’ (God [Arabic] almighty [Sanskrit]). After a while, we safely arrive the destination. As we part, I say ‘dhanyavāda’ (Thank you [Sanskrit]). dekha hobe! (See you! [Bangla]) and the driver returns ‘xoda ḥafīẓ!’ (God [Persian] be with you! [Arabic]).

Everyday conversation in Bangla is thus rich with linguistic diversity. Bangla is the national language of Bangladesh, which Bangladeshis are very proud of. However, behind the current prestige of Bangla lies a tragic memory of Bangladeshis’ struggle for cultural, linguistic, and ethnic freedom.

Bangladeshis symbolically commemorate that struggle every year on February 21st, calling the day Shoheed Divosh (Martyrs’ Day) or more commonly, Ekushey (Twenty-first). Ekushey became the cultural symbol of Bangladesh because several sacrificed their lives and hundreds were injured during a march on February 21, 1952, in their effort to promote Bangla as a national language of Pakistan.

As a result of the independence movement that ended the British colonial rule, Dominion of India (current Republic of India) and Dominion of Pakistan (later Islamic Republic of Pakistan) were created in 1947. Pakistan was formed under the leadership of Muhammad Ali Jinnah who led the Muslim League. The nation then consisted of East Pakistan (which later became Bangladesh) and West Pakistan. They were two regionally, ethnically, and linguistically distinct regions. Nevertheless, since the majority of people in these two regions were Muslims the leaders of the Muslim League hoped that their shared religious identity was strong enough to tie them together.

“An auto rickshaw.” Photo courtesy of Kiyokazu Okita.

“An auto rickshaw.” Photo courtesy of Kiyokazu Okita. However, maintaining this hope became increasingly challenging as people in East Pakistan quickly realized their economic and cultural differences with West Pakistan. In this context, the status of Bangla in Pakistan became the most explosive political issue. Despite the repeated demand from East Pakistan that Bangla be made one of the state languages alongside Urdu, the most prominent language in West Pakistan, leaders in West Pakistan never acknowledged the demand. In 1948, Ali Jinnah visited East Pakistan and publically announced that only Urdu can be the state language, arguing that among many languages spoken in Pakistan, Urdu best represented Islamic culture and tradition. In the nineteenth century, Urdu became the symbol of Islamic language in South Asia due to its use of Arabic letters and its shared vocabulary with Arabic and Persian. Moreover, Bangla was typically associated with Hindu culture due to its connection with Sanskrit.

In January 1952, the Muslim League finally made Urdu the official state language of entire Pakistan. Political leaders, the representative of cultural organizations, and students in East Pakistan immediately expressed their opposition, leading to a demonstration on February 21st. In the demonstration, several people died and many were injured as they clashed with the police.

In the following years, Shaheed Minar (Martyrs’ Column) was erected and the celebrated song, Amar Bhaiyer Rakte Raṅgano (Colored in the blood of my brother), was composed. The collective memory of this tragic event fostered the development of the regional identity distinct from that of West Pakistan, which eventually led to the independence of East Pakistan as People’s Republic of Bangladesh in 1971. The language of Bangla thus became a symbol of Bangladeshis’ cultural, regional and ethnic identity.

After independence, the memory associated with Ekushey increased. Nowadays, Bangladesh dedicates the entire month of February to celebrate the Bangla language. A large book fair is organized in Dhaka and various cultural performances are conducted throughout the country. The significance of Ekushey further became international when, in 1999, UNESCO declared February 21st as International Mother Language Day in order to celebrate language diversity worldwide.

“Pride in mother tongue does not have to lead to narrow-minded sense of superiority.”

It is certainly important to learn one’s mother tongue because language is the vehicle of culture and tradition. Thus older generations’ complaints about young generation’s Hinglish and Banglish is well justified. That said, since language and nationalism are closely related, we should be careful that emphasis on mother tongue not lead to a narrow-minded linguistic nationalism either. Unfortunately, however, this is what happened in post-independent Bangladesh.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the first Prime Minister of Bangladesh, sought to build the new nation on the principles of nationalism, secularism, democracy, and socialism. In his effort to unite the country, he promoted Bangla as the national language of Bangladesh. However, while Bangla is the language spoken by the majority of people in Bangladesh, there are minority communities such as Manipuris, Chakmas, and Santals whose mother tongues are not Bangla. Nevertheless, Mujibur asked them to embrace Bangla, rejecting their right to maintain their mother tongues. This is sad as it undermines the very principle of Ekushey, through which Bangladesh claimed its independence from Pakistan.

When those who are dominant – due to their strength or numbers – force the other to adopt their language, as West Pakistan did to East Pakistan, or Mujibur to minorities in Bangladesh, it becomes a form of violence. However, pride in mother tongue does not have to lead to narrow-minded sense of superiority in one’s ethnicity or nation. As in the case of Bangla, we can observe in any language the influence from other languages. On International Mother Language Day, perhaps we can reflect on the linguistic diversity within our mother tongue that reflects a rich history of interaction.

Image Credit: “Shaheed Minar on Ekushey, 21st February.” Photo courtesy of Kiyokazu Okita.

The post Celebrating linguistic diversity on International Mother Language Day appeared first on OUPblog.

Trust in the aftermath of terror

In the days following the terrorist attack in Paris on 11 January, thousands of people took to the street in solidarity with the victims and in defense of free speech, and many declared ‘Je suis Charlie’ on social media around the world. The scene is familiar with what we have seen in several other countries in the aftermath of major terrorist attacks. Rather than driving people away from the public sphere, these events seem to bring people together and mobilize the social capital of society.

One may think that acts of terrorism would lead to increased cynicism and distrust towards fellow citizens and in the authorities that failed to protect us. However, rather than becoming misanthropes locking ourselves behind doors, we seem to rally around the core values and institutions of state and society, especially when the targets of terror are loaded with symbolic meaning as they were in the United States in 2001, in Norway in 2011, and now recently in Paris. If we look at the United States and Norway we find in both countries a significant increase in trust in other people and in government institutions in the immediate aftermath of the terrorist attacks.

In both cases the boost in trust was only temporary and after a while it fell back to pre-terror levels. In Norway, public debate very quickly started to focus on how the police had handled the terror incidents. As it became increasingly clear that serious mistakes had been made, it was assumed that trust in the police would fall well below previous levels. However, despite the “harsh” conclusion of the government-appointed commission in Norway, polls taken immediately after the publication of the report showed that trust in the police was only slightly lower than prior to the attack. Further polls taken a month after the release of the report also showed no significant difference. Moreover, while a majority of the citizens appeared to be critical of the way the police handled the events on 22 July 2011 and in the aftermath, particularly at the island of Utøya, it did not translate into a significant drop in trust.

Police car in Paris, May 4, 2009 by Andre Bulber. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Police car in Paris, May 4, 2009 by Andre Bulber. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. The seemingly paradoxical co-existence of strong criticism and a high level of trust in the police makes sense if viewed within the framework of procedural justice theory. This theory suggests that the perceived motives and intentions of the police matter more to people than the effectiveness and outcome of police work. Thus when the Norwegian police seriously acknowledge the criticism from the commission and signaled a will to change, this appeared to have a greater impact on trust in the police than the failures that had led to the criticism. The initial high level of trust may of course also explain why it has such a resilient position in Norwegian society, therefore it would be premature to conclude that trust is equally resilient in a setting with lower initial levels of trust as is the case in France.

While trust appears to be quite resilient even in the face of a major terrorist attack, at least in countries where there is high level of trust, it would be premature to conclude that terrorist attacks have no effect. The terrorist attacks may lead to policy responses that indirectly and in the long run influence trust in a negative manner. While both the 11 September Commission and the 22 July Commission basically concluded that the problem prior to the attacks was not so much a lack of resources and legal powers, but rather a lack of imagination and coordination, the main political response in both countries has been to increase resources and legal powers to the police. In Norway, for example, the political discourse in the last couple of years has focused mainly on centralization, surveillance, and whether to permanently arm police officers. While this may improve police preparedness, it may also increase the distance and reduce everyday interaction between police and the public. Moreover, if this is combined with more aggressive police tactics with reduced emphasis on procedural justice, trust is likely to erode.

But isn’t somewhat less trust a price worth paying if we can become better prepared to prevent terrorism? Well, the thing is that trust is also an important predictor when it comes to levels of cooperation and compliance with the police. In the context of preventing terrorism, it is vital that the general public is willing to share their concerns about persons, groups and activities with the authorities. Thus, by sacrificing trust we may in fact undermine police efficiency in the long run. Finally we also argue that if the result of terror is a police force that builds its legitimacy on fear instead of trust, then the terrorists will have won, not only the battle, but the war.

Note from the Editor: this post was written in January 2015, before the shootings in Copenhagen in February.

Headline image credit: Utøya by Paalso Paal Sørensen 2011. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Trust in the aftermath of terror appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers