Oxford University Press's Blog, page 697

February 21, 2015

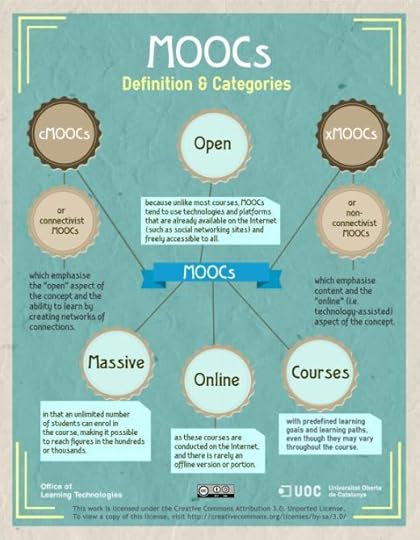

Does the MOOC spell the end for universities?

The seemingly unassailable rise of the MOOC – the Massive Open On-Line Course – has many universities worried. Offering access to millions of potential students, it seems like the solution to so many of the problems that beset higher education. Fees are low, or even non-existent; anyone can sign up; staff time is strictly limited as even grading is done by peers or automated multiple-choice questionnaires. In an era of ever-rising tuition fees and of concerns about the barriers that stop the less well-off from applying to good universities, the MOOC can seem like a panacea.

Certainly, it has attracted some big names. Harvard, MIT, and Stanford are all involved. In Britain, MOOCs of various sorts have been started by universities from Leeds to Leicester and from Sheffield to Strathclyde. Time magazine has talked about the MOOC as an ‘Ivy League for the Masses’, and scarcely a week goes by without the professional press running yet another enthusiastic article on the subject.

Little wonder, then, that some have started to see in the MOOC a harbinger of doom for the traditional university. In a recent piece, for instance, one journalist even speculated that ‘the bricks-and-mortar elite will end up on the wrong side of history’, replaced by this cheaper, easily accessible, apparently more democratic mode of learning. Politicians, too, have shown enormous enthusiasm for the MOOC as a plausible replacement for the expensive, elitist institutions that so many of their constituents dislike (and fear their children will be unable to attend).

It’s impossible not to applaud the ambition of widening participation in higher education, not just to hundreds or thousands, but to many millions. MOOCs, by their sheer scale, seem to offer far more than the traditional university extension or adult education programmes that have been running for the last century or so. The emphasis on technology that any on-line course inevitably brings with it is also intriguing. Indeed, it plays to all our fears and hopes about the future. A virtual university sounds like exactly the sort of thing we ought to be expecting – and so the MOOC is, in many minds, granted a horrible sort of inevitability. As it rises, it is reasoned, so the older idea of the university must fall.

Definition of MOOC by Universitat Oberta de Catalunya via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.5)

Definition of MOOC by Universitat Oberta de Catalunya via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.5) Yet there are very good reasons for thinking this assumption not merely mistaken, but quite the reverse of the truth. It’s worth reiterating the point that critics always make, for instance, and drawing attention to the MOOCs’ quite remarkably low completion rates. Millions may sign up, but fewer than one in ten stay the course. And this is not merely because MOOCs do not produce a degree-level qualification. After all, the degree-awarding ‘E-University’ set up by the UK government in 2003 cost £50 million and attracted only 900 students. In the words of one expert, Michael Shattock, it was ‘perhaps the biggest financial white elephant in Britain’s higher education history’.

Even the success of the Open University, Britain’s pioneering attempt to provide an alternative route to higher education, tells a rather different story from the one that MOOC fans will want it to and MOOC-phobes may fear. Delivered on-line and on-air, its courses lead to degrees – one can even get a doctorate – and have attracted thousands of takers. Indeed, the OU is now Britain’s biggest university.

The truth is, however, that the OU is actually a rather traditional university; indeed, it is establishing a MOOC of its own for precisely that reason. It may use technology, but – in the end – it relies on a mixture of lectures (however delivered) and personal tutorials. Work is marked by a person, not a PC, and students meet real, live tutors for regular tutorials.

What this suggests is that people want and expect something rather more than a purely virtual, entirely electronic experience of university. They expect it to be a place. Indeed, the last two hundred years, which have seen the foundation, consolidation, and expansion of hundreds of new campuses in England alone, have only served to reinforce the sense that a university is somewhere as well as something. A disembodied, displaced university does not quite do the job.

Indeed, this emphasis on the university as a distinctive and distinctly different place has actually intensified in recent years. The number of students who wish to live in university accommodation has increased, with only 6% of prospective undergraduates surveyed last year wanting to stay at home and study. The other 94% expected and hoped to move away to a different place for their degrees. This, it should be recalled, is the internet generation; the natural consumers, one might have thought, of on-line offerings. It turns out that they are even more wedded to older ideas about the nature of the university than those who went before them.

Historians study the past, not future; we tend to make poor prophets. Perhaps improvements in technology will make the MOOCs more appealing in the end. Certainly, if tuition fees continue to rise, it’s difficult to see how the very poorest will be able to aspire to life at the very best universities. They may be forced to turn to a virtual university, however much they’d rather not.

But the idea of the university as a place; of university life as one lived out on campus: this seems so deeply-ingrained that it’s hard to see how even the most exciting MOOC can ever really challenge it. It seems more likely that the MOOC will prove to the loser in this battle, as students and their parents seek somewhere to study, just as they have for centuries.

Headline image: Victoria Building, University of Liverpool, by Ian-S. CC-BY-NC-2.0 via Flickr

The post Does the MOOC spell the end for universities? appeared first on OUPblog.

February 20, 2015

The art of listening

A few months ago, we asked you to tell us about the work you’re doing. Many of you responded, so for the next few months, we’re going to be publishing reflections, stories, and difficulties faced by fellow oral historians. This week, we bring you the first post in this series, focusing on a multimedia project from Mark Larson. We encourage you to engage with these posts by leaving comments on the post or on social media, or by reaching out directly to the authors. If you’d like to submit your own work, check out the guidelines. – Andrew Shaffer

I believe that “all stories are partial” and that “we need a multiplicity of stories to tell the whole story of our democratic experiment,” as author and poet Keith Gilyard has said. I curate a website, American Stories Continuum, the purpose of which is to share the voices of people I am listening to across our country as they explore aloud their own thoughts, beliefs, emotions, and experiences. The conversations revolve around specific topics like teaching in the 21st century, our personal relationships with money, and change. I am not a pundit, analyst, or debater. My aim is to hear them so I might briefly view the world through their eyes and share what I have heard.

I have undertaken this project for two reasons: I was interviewed twice by the great interviewer Studs Terkel and have seen him work. I know what it is like to be listened to for an extended session and with intense curiosity. I believe everyone deserves a chance to be heard that way. Secondly, I have grown weary and cynical of the cacophony of arguments that pose as discussion on television and radio. In Studs’ tradition, my message is: I am here to listen. I want to know what you make of your life, of life itself, of what is happening in our world. Like Theodore Zelden, I’m interested in the kind of conversation in which “you start out with a willingness to emerge a slightly different person.” I believe it’s possible to better know ourselves, both collectively and as individuals, when we allow ourselves to better know one another.

Most of my interviews generally take 60 to 90 minutes, with follow-up for clarification or to delve more deeply into previously glossed over topics. Some are phone interviews, but I make a rule of insisting on face-to-face conversations as often as possible.

I have a few prepared questions, but I am not seeking particular responses. I derive great pleasure in seeing where conversations will go within the framework of the topic–discovering, along with my interviewee, the story that he or she has to tell. It is always a fresh process of discovery, which is repeated in the editing phase, then again as the interviewee responds to the edited text, and finally as readers respond to what they read. The final pieces posted on the site are the version both they and I agree most accurately represents their voice and their story.

I take liberty in constructing the narratives from verbatim transcripts for the sake of teasing out the story that I sense is emerging. This requires rearrangement and elimination. But I adhere to the interviewees’ actual words and each person has vetted and approved them. This is a partnership in which my singular aim is faithfulness to what the subject feels and expresses.

Included here are brief clips from two of my interviews. The interview with 97-year-old Civil Rights activist and author, Grace Lee Boggs, came about when I heard that a 36-year-old teacher named Julia Putnam planned to open a school in Detroit based in Grace’s writings and philosophy. I have always been fascinated by the interplay between generations, so I asked to interview both of them together to talk about the aspirations for this school, which had not yet opened. We met in Grace’s living room in Detroit on a hot afternoon. As you listen, tune into the way these two generations, separated by half a century, play off one another. They’d known each other for 20 years, since Julia was 16 and signed on as the first member of Detroit Summer, which Grace and her husband, Jimmy Lee Boggs founded.

The interview with educator and author Gloria Ladson-Billings was one of my first. When I was a student of education, Gloria’s writings were highly influential to me. I wanted very much to meet her. The interview was almost just an excuse to spend time with her. She quickly granted the interview and we met in her University of Wisconsin-Madison office. In these clips, she talks about how she always views world events in an historical context. I reposted these interviews after the Ferguson, MO, Grand Jury Decision in the shooting of Michael Brown because she had offered a useful and comforting way to consider troubled times.

I was pleased recently to see that Gloria posted the clips to her Facebook page and said, “I really like the photos he chose. He got it.” That’s my aim. Faithfulness.

Image Credit: “Mark and Terri.” Photo used with permission from Marc Perlish.

The post The art of listening appeared first on OUPblog.

Speaking to the heart of what matters: a Q&A with Editor in Chief, Adam Timmis

Meet Professor Adam Timmis, the Editor in Chief of the latest member of the European Society of Cardiology journal family, the European Heart Journal — Quality of Care and Clinical Outcomes (EHJ-QCCO). We spoke to Timmis about how he became involved in cardiology, the challenges and developments in his field, and his plans for EHJ-QCCO.

* * * * *

What encouraged you to pursue a career in the field of cardiology?

In 1987, when I took up my first consultant job, cardiology was on the brink of a revolution that I wanted to be part of. The trials of coronary bypass surgery were already published and the trials of coronary stenting and thrombolytic therapy were coming on line. Add to this the emerging medical treatments for coronary disease and heart failure, plus the more recent advances in interventional electrophysiology. There is no doubt that cardiology was – and remains – the most exciting medical specialty on offer.

What do you think are the challenges being faced in the field of cardiovascular care, health economics, and prognosis today?

The challenges we face are, in many respects, welcome challenges because they stem from the variety of investigatory and therapeutic options that are now available in clinical cardiology. We are spoilt for choice and it is important that we make those choices wisely, considering not only the evidence base for investigation and treatment but also the costs at a time when healthcare budgets are stretched to the limits of what we can afford

How do you see this field developing in the future?

“Quality of Care and Outcomes” speaks to the heart of what matters to patients. As the field develops it must be the patient’s voice that we listen to in developing our research programmes. This will require more attention to patient related outcome measures and a focus on research to enhance the quality of life, not prolong the process of dying.

Professor Adam Timmis, the new Editor-in-Chief of European Heart Journal — Quality of Care and Clinical Outcomes

Professor Adam Timmis, the new Editor-in-Chief of European Heart Journal — Quality of Care and Clinical OutcomesWhat are you most looking forward to about being Editor in Chief for the EHJ-QCCO?

I am looking forward to working with my Editorial Team to make this a high quality journal that meets the needs of both researchers and readers. I want EHJ-QCCO to join Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes as a leader in this emerging field of outcomes research.

What do you envisage your typical day as the Editor in Chief looking like?

Having spent seven years editing Heart I recognize that there is no such thing as a typical day! Most of the work is done online and can be picked up in dedicated time slots. However, regular contact with the Editorial Team and the publishers (Oxford University Press) is important and I will need to make time for that as well. The availability of videoconferencing software for office use and use by mobile phone helps to make the workload manageable

Is there any aspect of the Editor in Chief role that has surprised you so far?

Surprise is perhaps the wrong word but I have been delighted by the support on offer from the European Society of Cardiology, Oxford University Press, and the excellent Editorial team I have built around me.

Can you tell us about the new journal? Its aims, and the scope of the papers that you are publishing?

We will seek to publish high quality cardiovascular research into quality of care and outcomes, our key aims being:

conducting outcome comparisons at hospital regional national and international level

benchmarking quality of care

setting new publication standards for outcomes research

encouraging young investigators and supporting growth of the outcomes research community

informing cardiovascular public health policy internationally

Why do you see this as an important addition to the ESC Journals portfolio?

Prognosis research has been something of a Cinderella interest but recognition that patient outcomes may vary widely between hospitals and also between healthcare systems has now identified it as one of the most important growth areas in contemporary academic medicine.

Read the instructions to authors and learn how to become part of this new community.

Heading image: Heart beat. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Speaking to the heart of what matters: a Q&A with Editor in Chief, Adam Timmis appeared first on OUPblog.

Thoughts on teaching in prison on World Day of Social Justice

On an overcast day in January 2013, with no criminal justice background and no real teaching experience, I entered the stark grounds of New Jersey’s only maximum-security women’s prison to co-teach a course on memoir writing. The youngest in a classroom of thirteen women, many of whom were serving life or double-life sentences, plus my two mentors and co-teachers, Courtney Polidori and Michele Tarter, my mind began spinning with concern and doubt. How could I pull this off? How could we bring these women, some of whom had been hardened, seemingly for life, by the “punishment industry,”to trust us enough to help them find their voices as empowered writers? The only answer was for me—myself—to trust. To trust in the transitive power of words, in the aching souls yearning for solace, in the mad, wide world that brought me here with a willingness to try.

Some context: Dr. Tarter had begun “Woman is the Word,” the course at the prison, over a decade before I enrolled in her capstone literature seminar on autobiography as a junior at The College of New Jersey. Meaning that some of the “wisewomen” (our students, whom we never refer to as “inmates”) she taught nearly fifteen years ago were still incarcerated, many anxiously waiting for her return. Why? Because she changes lives. I carry her words with me to this day, using her strength and the strength of our students to keep my mind open to whomever I may meet: “If you walk from a state of love, and not a state of fear, all these walls around you will be shattered.”

From left: Zimbler, Tarter, artist Russell Craig, and Polidori at Rutgers’ “Marking Time” Conference, 2014

From left: Zimbler, Tarter, artist Russell Craig, and Polidori at Rutgers’ “Marking Time” Conference, 2014The course is based off the pedagogy of powerful women across time and place, particularly scholars and activists Audre Lorde and bell hooks. As we spent months preparing our syllabus and course materials from scratch, Lorde’s words, from a 1977 speech to the MLA, kept ringing in my ears: “What are the words you do not yet have? What do you need to say? What are the tyrannies you swallow day by day and attempt to make your own, until you will sicken and die of them, still in silence?… I am myself, a black woman warrior poet doing my work, come to ask you, are you doing yours?”

The first day we toured the facility, as soon as we left the minimum-security grounds and took the barren, sobering walk to “max,” I began to realize why Michele had refused to teach anywhere but in maximum-security.

The stately yet broken-down buildings along the path to “max” are eerily reminiscent of a southern plantation rather than a place of rebirth. This, along with other intrusive sensory effects—silence is no friend, and the smells and sights bring comparable insanity—and even the spellbinding interactions we had with our students, are all impossible to describe properly.

When you leave the facility, when you re-don your underwire bra and collect your cell phone and car keys and feel your tires crunching down Freedom Road, there is an overwhelming feeling of emptiness you still carry with you. The inability to record those moments, to even mention any names and wave them in the faces of the otherwise careless and say “look! look at the beauty of human potential through our eyes!” can be the cement block in the way of real social change. In The New Jim Crow, scholar Michelle Alexander writes that today, while women are a small portion of incarcerated Americans, they represent “the fastest-growing segment of the prison population.” We leave the facility understanding the power of our freedom, and the burning fire beneath it — our responsibility to act on it.

Zimbler speaking at the Campaign to End the New Jim Crow’s “Read-Out,” Princeton.

Zimbler speaking at the Campaign to End the New Jim Crow’s “Read-Out,” Princeton.The purpose of memoir-writing is not to excuse oneself from past actions, but to reflect on those actions with strength and use them to understand the present and change the future. To do so, one must be ready to go to those dark places. A writer myself, I never mustered the strength to write a full autobiography, but we had students who wrote hundred-page books with appendices of letters, poetry, lyrics, and confessions. Our “wisewomen” inspired me to write more than I could ever fit into one lifetime, but they also encouraged me to write with them and challenged me to share my own work with them.

This wasn’t a typical classroom dynamic — we were all students of one another. The writing our students produced was far more gripping, grittier, and moving than anything I had seen in an undergraduate writing workshop. But the system has been trying to define these women their whole lives, so how can it expect change without giving them a voice to prove they can?

Dropping my creative writing minor in favor of true active learning was not a difficult decision: complete a writing workshop with words I’d already written and wait nervously for other students’ nervous feedback, or advocate the written word in a powerfully raw and innovative classroom experience? Wasn’t the prison the exact place to engage with the human condition? To discover the writers’ purpose, audience, and potential? Working through the stories these women kept inside and helping them bring their struggles and victories to light would influence my life, and every life in that classroom, in ways we could never imagine. More importantly, it would contribute to a much-needed sense of humanity in a place devoid even of proper health and mental care.

Since our “Woman is the Word” workshop, Courtney and Michele have continued teaching courses at the prison and we have presented scholarship throughout the country on the profound experiences we had with our students — at various academic conventions, meetings with local Quaker Friends, the Campaign to End the New Jim Crow, and, most recently, Rutgers University’s “Marking Time” conference, where we met and shared our writing with exceptionally talented artists inspired by their former incarcerations. After fifteen years of volunteering in the prison, Michele is finally on sabbatical this year, but not to rest — to write the book.

“As I have found over the years of volunteering in the prison,” Michele told me, “these women hold so much insight and lived experience about our culture’s social injustices and gender inequities.” Life Sentences: Writing with Wisewomen behind Bars, the tentative title for the book Michele hopes to complete by this summer, will be a testament not only to the importance of education in the prison but to the wisdom of these women who have been locked up and, as such, silenced.

Cover of chapbook created for students by Samantha Zimbler.

Cover of chapbook created for students by Samantha Zimbler.>A few months back, Courtney sent me a voicemail after returning from the first NJ prison graduation ceremony rewarding students with community college associate’s degrees. Many of our workshop participants received their degrees that day.

Although it was just her recorded voice speaking to me, I shared something with her at that moment, something that can’t be shared with those who have no experience with the prison system. But that didn’t make it unreal — some of the students who earned their degrees that day included women we saw evolve from introverted, broken people to lively, philosophical artists.

If this is not astounding evidence of human potential among those many deem unfit for society, then we have nothing to fight for. But these women don’t need teachers to give them hope or humanity; it is already there. Our job is to nourish these bonds, and to show the world that the “madness” often associated with the inmate does not indicate an inability to relate to others or to reality. It is a misnomer used to intimidate the entitled from being “contaminated” by people they see as damaged, which disables us from seeing truth and demanding justice.

How should you celebrate World Day of Social Justice this year?

Consider starting a prison course of your own, using our freely downloadable portfolio of teaching materials.

Consider donating to a maximum-security prison complex’s library.

Read, share, and find power in the stories of the oppressed.

>Don’t let your silences take advantage of your life. Remember our classroom mantra: freedom is a not a state of bars — it’s a state of mind.

You can also learn more about the effects of mass incarceration on those behind and beyond bars, their families, and society at large with the below readings from Oxford Handbooks Online:

The Collateral Effects of Imprisonment on Prisoners, Their Families, and Communities

Life on the Outside: Transitioning from Prison to the Community

The Psychological Effects of Imprisonment

Living Life Behind Bars in America

Mass Incarceration: From Social Policy to Social Problem

American Corrections: Reform Without Change

Introduction to The Oxford Handbook of Gender, Sex, and Crime

Image Credit: “Old Women’s Prison: Chiang Mai, Thailand 2014.” Photo by drburtoni. CC by NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Thoughts on teaching in prison on World Day of Social Justice appeared first on OUPblog.

Psychotherapy now and in the future

The following in an extract from Psychotherapy: A Very Short Introduction, by Tom Burns and Eva Burns-Lundgren, in which they discuss the future of psychotherapy.

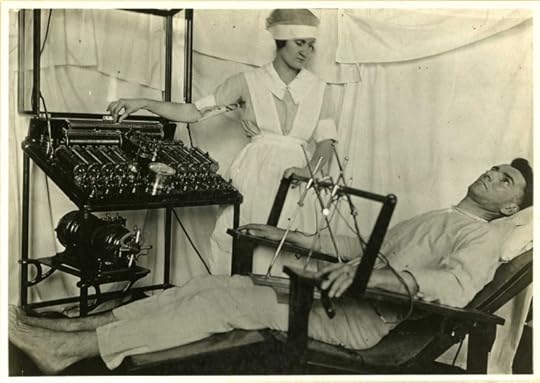

The 20th century has been called ‘the century of psychiatry’, and in many ways one could read that as ‘the century of psychotherapy’. A hundred years ago, at the onset of World War I, psychotherapy had touched the lives of only a tiny number of people, and most of the population had simply never heard of it. Since then it has reached into almost every aspect of our lives—how we treat the mentally ill, how we understand our relationships, our appreciation of art and artists, and even how we manage our schools, prisons, and workplaces. Our culture has become one quite obsessed with understanding how people feel and our daily language is peppered with psychotherapy language.

What does the future hold? Have we witnessed the flowering of a cultural movement that is tied to just one unique time and place, or is it a fundamental step forward in human thinking and relationships? In our increasingly global world will it spread ever more widely or perhaps fade away altogether? Have the various changes in its practice made it more relevant to modern man or less so? Will the enormous advances in medicine, neuroscience, and psychology, and our move into the digital age of social media, render it obsolete?

How we judge psychotherapy’s future will probably reflect what we think of it now: as a profound breakthrough in understanding ourselves and a step forward in social evolution, or as simply one among many technical procedures to reduce distress and improve human well-being. Reducing distress is certainly not a trivial achievement, but it does not satisfy psychotherapy’s strongest advocates—they believe it has irrevocably changed the way we see the world and how we behave. From a different perspective, psychotherapy has been criticized right from the beginning for having ‘cult-like’ and religious overtones.

We have roughly divided psychotherapy’s century into two halves. Up to the 1960s it was either psychoanalysis or one of its modifications. Therapies were verbal, protracted, and intensive, drawing on a detailed theory of unconscious forces. Understanding was the key to recovery. Later therapies have been much more experiential. Understanding remains important, but the process of psychotherapy and the therapeutic relationship have come to the fore.

Psychotherapy in World War One, by otisarchives4. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Psychotherapy in World War One, by otisarchives4. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.Some people are struck by the similarities between these psychotherapies and some by their differences. Are they adaptations of the same basic model or new and original approaches? It is a bit like deciding whether a glass is half full or half empty. Therapists usually stress the differences and the unique therapeutic mechanisms in their approach. Psychoanalysts and CBT therapists have traditionally had very little positive to say about each other’s practice.

You may have found yourself drawn to one or other specific therapy. Alternatively you may come to the conclusion that they have more elements in common than divide them. The latter perspective is probably how we view things. Yes, CBT is undoubtedly radically different in tone, duration, and immediate focus from psychoanalysis. But both work by helping troubled individuals understand better the mental mechanisms that have caused and sustain their problems.

One thing the psychotherapies share is that they have all expanded their reach. The threshold for seeking psychotherapy or counselling has steadily lowered over the decades, and our demand for it seems inexhaustible. Their goals have also expanded—from just the reduction or removal of symptoms, towards self-fulfilment and well-being.

We can be certain that psychotherapy will undergo changes in both theory and practice. What is impossible to foresee is precisely where these changes will occur. The trend towards shorter, more structured and democratic therapies seems inexorable, but radical changes may come out of the blue. Will they come from developments such as computer science, or perhaps from other cultures than the Judeo-Christian origins of most current therapies? Prediction is a risky business.

The post Psychotherapy now and in the future appeared first on OUPblog.

February 19, 2015

Chinese New Year and psychology [infographic]

With China’s continued emergence as an economic and political superpower, there is a growing need for those in the West to understand the distinct way in which the Chinese people view the mind and its study. Although Chinese philosophy is steeped in considerations of the nature of the mind, psychology as it is understood in the West was not a discipline practiced in China until its introduction in the 19th Century.

In The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Psychology, edited by Michael Harris Bond, a variety of leading experts provide a detailed yet accessible exploration of topics related to Chinese thought processes and identity, analysing their role in the creation of Chinese culture as it exists today as well as focusing on inter-cultural relations with the Chinese, showing how professionals can work more effectively when conducting business with Chinese people.

To celebrate Chinese New Year, here is an infographic detailing the adoption and transformation of psychology as a subject of study in China.

Download the infographic in pdf or jpeg.

Image Credit: “Edmonton Chinese New Year 2015.” Photo by IQRemix. CC by SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Chinese New Year and psychology [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

Great man drumming: Birdman, Whiplash, and myth of the male artist

Among this year’s Oscar nominees for Best Picture were two films with drum scores: Whiplash, in which a highly regarded but abusive conductor molds an aspiring young jazz musician into the genius he was meant to be, and Birdman, in which an aging film actor who was never a genius at all stars in a play and possibly flies. In spite of their innovative soundtracks, neither film received an Oscar nomination for Best Original Score. In the case of Whiplash this was unsurprising; the film’s key scenes use jazz standards, not new music. However, the exclusion of Birdman was controversial. The executive committee of the Academy’s music branch determined that Antonio Sanchez’s drum score was “diluted” by the classical music also featured within the film and thus ineligible for nomination. I want to consider what that ruling, which was unsuccessfully appealed by the film’s director, Alejandro G. Iñárritu, says about the meaning of rhythm, music, and masculinity in a year of “great man” pictures.

“Great man” films are comforting because they confirm the inevitability of achievement. Whether they are based on historical figures or merely suggest them, we watch these movies with an expectation that the hero will overcome obstacles through personal conviction and dedication to his craft. Director Damien Chazelle delivers on this promise with Whiplash. Andrew, the film’s young drummer, aspires to play charts to perfection. His practice sessions, to which Chazelle devotes rather fetishistic attention, are rife with photogenic blood and sweat, not unlike training sequences in sports films. Indeed, Fletcher, the conductor of the school’s most prestigious jazz band, has more in common with the cinematic stereotype of a sports coach than a professor. If his homophobic insults and physical abuse seem out of place in a conservatory, it’s because Whiplash isn’t about making music, but making men.

In Whiplash, rhythm is precise, directional, owned. “Not my tempo,” Fletcher repeats again and again, as he asks Andrew to follow his lead, to assimilate. Drumming in Whiplash is an elaborate ritual of induction into an elite club of men, for the fictional conservatory’s unmentioned exclusion of female students can be no accident. Andrew will be “great” because he plays well-known jazz tunes accurately, alone, in a practice room, until he bleeds. Rhythm provides the structure for the entrance into manhood and the mechanism for disciplining masculine behavior.

Birdman, on the other hand, uses rhythm as an expression of being, an extension of the character’s perspective into the shared experience of the viewer. Drum solos follow the film-turned-stage actor, Riggan, as he moves about the theater or weaves his way through the city. Our perception of the drumming mirrors how Riggan understands the fantastic elements of his life. He hears the voice of Birdman, the superhero he once played on film, and he seems to possess superhuman abilities himself, yet both are impossible within the boundaries of the world inhabited by the characters. Several of Sanchez’s drum solos consist of layered tracks, making them similarly impossible, for no live performer could replicate the sound. In spite of its inexecutability, at times the music becomes diegetic—a drummer will appear in the theater’s kitchen or on a city street—although we are never certain whether to accept him as an objective figure revealed by the film’s narrator or an illusory character generated by Riggan’s mind. Unreal and real at once, the drumming, like the special effects, is only possible because of the cinema.

As in this clip, the drums provide a structure for Birdman’s conspicuously long tracking shots (the film tricks us into imagining it is a single take). Sanchez’s cues make up approximately 30 minutes of the score, giving life to sequences that might otherwise drag, yet they are not directional; Sanchez’s improvisations neither comment on Riggan’s intentions nor insist that he adopt a more worthy set of narrative goals. Because of the affinity between Riggan and the drums, rhythm ties us to the character. Iñárritu asks us to experience the uncertainty of Riggan’s venture along with him; success is by no means guaranteed.

The radically different meaning of rhythm in Whiplash and Birdman reflect two distinct worldviews, not only in their representation of men, but also in their perception of time. In Whiplash, time is external and objective, and yet, as Henri Bergson writes, this understanding of duration is “a fiction whose origin is easy to discover”. This is time in service to the “great man” narrative, the “fiction” of masculine expectations, the Romantic tale of the male artist at work. Andrew will be great, Whiplash tells us, because he has found the “right” rhythm, a rhythm he can share with no one, appreciated only by the sadistic father figure who reigns over the film’s presentation of patriarchy. Although he performs no music himself, Riggan’s rhythm is subjective; drumming in Birdman makes audible the duration of his reality. Bergson says, “to perceive consists in condensing enormous periods of an infinitely diluted existence into a few more differentiated moments of an intenser life.” Unlike Fletcher and Andrew, Riggan perceives the preposterous image of the masculine ideal—not even he really wants to be Birdman. The intensity of Iñárritu’s single take paired with the audacity of Sanchez’s drums unravels the fiction of the “great man.” Riggan doesn’t become “great” by shooting himself in the face; rather, he becomes conscious of the incompatibility of the male artist with the culture of celebrity.

So what does the ineligibility of Birdman’s score tell us about the myth of the male artist? It may suggest that the Academy doesn’t see drumming as original music, certainly a position that ought to invite our scrutiny. But it also exposes a problem with the idea that film music should exist in service to the narrative. When that narrative is repeatedly devoted to the imminent triumph of great men, is it any wonder that Sanchez’s improvisations would fall on deaf ears?

Headline Image: Drum. © carloscastilla via iStock.

The post Great man drumming: Birdman, Whiplash, and myth of the male artist appeared first on OUPblog.

Why are some residency programs better than others?

Considerable variation in quality exists among residency programs in the United States, even among those in the same specialty, such as surgery, pediatrics, or internal medicine. Some are nationally and internationally renowned, others are known regionally, and still others are known only locally. The strongest programs, invariably at major teaching hospitals, attract far more applicants than they possibly can accommodate. The weakest programs, most commonly located at smaller community hospitals, encounter difficulty filling their residency positions. These programs, if they are to have a house staff, often have to fill their positions with graduates of foreign rather than US medical schools, and even then many of their positions frequently go unfilled. At the best programs, virtually all graduating residents pass their board examination on the first try; at the weaker programs, only one-third.

What accounts for the differences in educational quality among residency programs? Certainly, it is not anything that can be readily measured. All programs have adequate physical facilities, enough beds and teachers, good laboratories and libraries, and sufficient formal lectures and teaching conferences. Had they not, they would not have been accredited by the relevant Residency Review Committee. The structural characteristics of residency programs do not provide the answer.

Rather, the differences in quality among residency programs results from differences in their learning environment. Facts and procedures can be taught in school-child fashion from lectures and demonstrations. This is not the case, however, for higher intellectual abilities such as analytical rigor, problem-solving skill, creative capacity, or the ability to manage uncertainty. Clinical judgment simply cannot be learned from books. Rather, it involves informal learning from conversations, discussions, reflection, role modeling, and absorption of the values and attitudes of the faculty. The better these elements, the stronger the residency program.

US Navy Ens. Frank Percy, right, a physician’s assistant from Naval Medical Center San Diego. US Navy, photo by journalist Seaman S. C. Irwin. Public domain via

US Navy Ens. Frank Percy, right, a physician’s assistant from Naval Medical Center San Diego. US Navy, photo by journalist Seaman S. C. Irwin. Public domain via

Transgender culture and community, now and then

Trans issues have been in the news lately — from Orange is the New Black to Laverne Cox on the cover of Time– but the trans community has a long history. It’s LGBT History Month in the United Kingdom this month, so we sat down with Trans Bodies, Trans Selves contributor Genny Beemyn to discuss the past and future of transgender culture.

In your opinion, what was the most important moment in history for the transgender community?

It would be easy to say the riots at the Stonewall Inn in New York City in 1969 or the earlier acts of resistance by drag queens at Cooper’s Donuts in Los Angeles in 1959 or Compton’s Cafeteria in San Francisco in 1966. But I will say the development of and growing access to the Internet. The ability to learn about different trans identities and to connect with others like themselves has enabled trans people even in isolated places to better understand their gender identity and have a sense of community.

How has transgender culture changed in recent years?

Well, that there is not one culture. When I came out about 20 years ago, you basically had two options in many transgender communities: to be a crossdresser or transsexual. As I identified as neither but as gender nonconforming, most other trans people I knew, who were older than I was, did not get me. Today, there are countless ways to identify as trans, with new ways being created all the time, mostly by younger trans people. Gender was never a binary, and that has become especially evident in recent years.

Taiwan transgender triangle. Photo by Jidanni. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia.

Taiwan transgender triangle. Photo by Jidanni. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia.How does transgender culture/perception still need to change in the future?

I think the bigger issue is how society, including many primarily lesbian and gay organizations, still has to change to recognize and embrace trans people. Trans people have an incredibly high murder rate—being driven to suicide and being killed by people who hate us because of our gender identities. Yet when it comes to LGBT people, the focus of most of the media and of many gay communities is on same-sex marriage. Many predominantly white trans communities can be faulted is their failure to address racism and classism and to acknowledge race and class privilege. The vast majority of trans people killed in the United States every year are poor trans women of color.

Do you have any advice/resources for those who are new to or simply would like to learn more about the transgender community?

There are many great websites and blogs on Tumblr. For news and information, I particularly like Monica Roberts’ TransGriot. For a trans person who is in crisis, there is a new helpline called Trans Lifeline: 877-565-8860. Beyond the chapter I wrote in Trans Bodies, Trans Selves, I would suggest Susan Stryker’s Transgender History for an overview of trans history.

The post Transgender culture and community, now and then appeared first on OUPblog.

Fairy tales explained badly

What are the strange undercurrents to fairy tales like ‘Hansel and Gretel’ or ‘Little Red Riding Hood’? In November 2014, we launched a #fairytalesexplainedbadly hashtag campaign that tied in to the release of Marina Warner’s Once Upon a Time: A Short History of the Fairy Tale. Hundreds of people engaged with the #fairytalesexplainedbadly hashtag on Twitter, sparking a fun conversation on the different ways in which fairy tale stories could be perceived. While the tweets began on 24 November and they continued to roll in until January this year. We loved reading everyone’s wildly different take on these classic stories and chose a selection of the best tweets for you to enjoy below.

[View the story “Fairy Tales Explained Badly” on Storify]

Wish you’d taken part? Why not post your own #fairytalesexplainedbadly synopsis in the comments below? We look forward to reading them!

Featured image credit: Trees at sunrise. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Fairy tales explained badly appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers