Oxford University Press's Blog, page 701

February 12, 2015

Darwin’s dice [infographic]

Charles Darwin’s theory of Natural Selection changed the way scientists understood our evolutionary past, and is a concept with which most people are quite familiar. One often overlooked element of Natural Selection, however, is the role that chance plays in guiding this process. In Darwin’s Dice: The Idea of Chance in the Thought of Charles Darwin, Curtis Johnson examines many of Darwin’s most significant writings through this lens. Celebrate Darwin Day by discovering the important role chance plays in Darwinian Theory.

Download the infographic in jpeg.

Image Credit: “Evolution Schmevolution.” Photo by Brent Danley. CC by NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Darwin’s dice [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDid you say millions of genomes?The love song and its complex gender historyWhat’s love got to do with it?

Related StoriesDid you say millions of genomes?The love song and its complex gender historyWhat’s love got to do with it?

The love song and its complex gender history

A recent study of commercial recordings finds that 90% are attributed to men—and most often men in their peak years of sexual activity. Perhaps this discrepancy is the result of bias in the music industry or among audiences, or maybe a little of both. Or perhaps we can conclude that Darwin was right about music. He believed that songs originated as a tool for courtship, not much different from the vocalizing of male birds during mating season. From this perspective, all songs are love songs, and men take the lead in this process as part of their biological mandate.

Yet close study of the cultural evolution of romantic music reveals that women contributed most of the key innovations in the love song. Even when men took most of the credit—which often happened—they frequently constructed their songs by imitating the earlier works of female singers. To some extent, the history of the love song can be described as the process of men learning to sing as if they were women.

In many times and places, this gender shift has led to criticism, and sometimes prohibition. Quintilian, complaining about the music of the early Roman Imperial era, griped that songs had been “emasculated by the lascivious melodies of our effeminate stage.” These have “no doubt destroyed such manly vigor as we still possess.” Did effeminate love songs lead perhaps to the fall of Rome? I doubt it, but many leaders of antiquity bemoaned these melodies. Seneca the Elder warned that “the revolting pursuits of singing and dancing have these effeminates in their power; braiding their hair and thinning their voices to a feminine lilt….This is the model our young men have!”

A similar backlash can be traced, even earlier, to ancient Greece. Here the lyric tradition created by a famous woman, Sappho, was inherited by men. They took bold steps to make the lyric a more manly and sober affair. Pindar, lauded by Quintilian as the greatest of the lyric poets, used his art to sing the praises of worthy men. But even here, the gender shift was inescapable—the lyric was, in its essence, all too clearly marked by Sappho’s legacy. Pindar was forced to admit, in a revealing confession: “I must think maidenly thoughts. And utter them with my tongue.”

This aspect of the lyric helps us understand other apparent anomalies. A papyrus discovered in an Egyptian tomb in 1855 contains previously unknown verses of a partheneion, or maiden song, from the earliest days of Greek lyric. But—strange to say—the composer of the song is a man, the poet Alcman. He is the earliest of the great male lyric poets of ancient Greece, but his surviving work is clearly composed for young women to sing. Like Pindar, Alcman served as spokesman for maidenly thoughts.

Half a world away, Confucius is credited as the esteemed authority who gathered the most famous ancient Chinese love songs into the collection known as the Shijing or Book of Songs. Many of the songs in this collection adopt a female narrative voice. How odd that Confucius, operating at almost the same time as Pindar, would also be linked with “maidenly thoughts.” Later Confucian scholars exerted a great deal of effort toward explaining away this apparent paradox. They hoped to prove that these songs weren’t really about women’s romantic yearnings—and some still aim to prove this. But few modern readers will be convinced by these attempts to remove the romance from these heartfelt love lyrics.

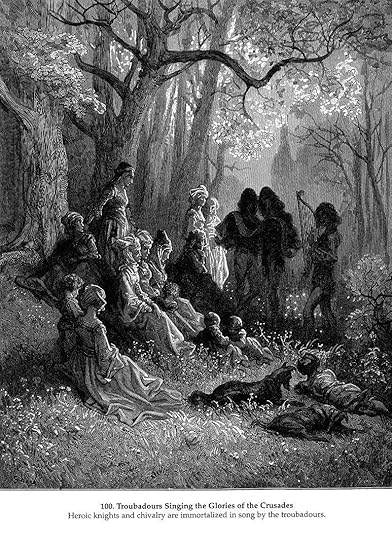

Troubadours singing the glory of the Crusades. Illustration by Gustave Dore. Public domain via WikiArt.

Troubadours singing the glory of the Crusades. Illustration by Gustave Dore. Public domain via WikiArt. Yet the most famous attempt to do just this comes from the Judeo-Christian tradition. The Biblical Song of Songs, the most famous love lyric in history, is attributed to King Solomon, but many of the sentiments expressed in the scriptural text are clearly from a female perspective. Scholars still argue over explanations for this anomaly. How did all this eroticism get into the Bible? But they rarely note (and are probably unaware of) how frequently famous men in other cultures also take credit for the love songs of women. Perhaps from a theological perspective, this state of affairs appears peculiar, but viewed in the context of the history of the love song, it is a familiar pattern, repeated again and again over the centuries.

In almost every instance, the names of the female innovators have not survived. They are the first undocumented workers in music history. Yet their contributions can still be traced and, more to the point, heard even today in the love songs that we use in courtship and seduction, or merely personal fantasy and idle entertainment.

The story of the female innovators behind the troubadours of southern France may be the most fascinating chapter in this mostly unwritten history. Scholars remember the names of the famous troubadours who are given credit for inventing key elements of the Western love song, but neglect to tell us of their predecessors, the elite female singing slaves of the Muslim world. These women, known as qayna, anticipated almost every key element in the ethos of courtly love long before the troubadours arrived on the scene. Indeed, the most distinctive element of troubadour song—namely, the singer’s posture of servitude and bondage to the beloved—was adopted by these women because they were in a state of actual servitude.

Many other medieval love lyrics have puzzled scholars, who have tried to explain why men are adopting a woman’s perspective. We find this with the chansons de toile, the spinning songs of the French trouvères. We encounter this with the Old English love lyrics from the Exeter Manuscript, “The Wife’s Lament” and “Wulf and Eadwacer.” And we find this in the Islamic world as well, where a host of effeminate singers, the so-called mukhannathun, enjoyed enormous popularity.

The surviving documents are filled with many puzzles, but they make clear that audiences responded enthusiastically to men who performed music as if they were women. One commentator ranked the eighth century performer Ibn Surayj as the best of the female singers. But he was clearly a man. The context makes it impossible to know whether this critic is making a joke, offering a musical judgment on Ibn Surayj’s performances, or merely referring to the singer’s way of life. In a similar vein, the celebrated master of Abbasid love lyrics Abbas Ibn al-Ahnaf, another man who composed ghazals performed in the caliph’s court, is described as “delicate, attractive, tender and full of ideas”—and here the qualities emphasized are clearly personal ones. We are left with an almost inescapable conclusion, that both performers and audiences saw a link between feminine qualities and skill as a purveyor of musical entertainment, especially love songs.

How did patrons and audiences react to this “effeminate” manner of singing? The story is told of a noble singer of the old style who was chastised by his son for changing his approach in his old age, and adopting the popular vocal style of the mukhannathun. He replied: “Be quiet, ignorant boy!” and pointed out that he had lived in poverty for sixty years singing in the old style, but now had “made more money than you’d ever seen before” by adapting to the new manner of performing.

This aspect of the love song continues in the current day. The gender complexities of The Rocky Horror Picture Show and Ziggy Stardust may have seemed radical to 20th century audiences, but the epicene stars of modern times were simply repeating a formula as old as the love song itself. Perhaps most of the recording royalties generated by our favorite love songs have gone to men, but at every step in the evolution of this music, the influence of women—whose names are rarely preserved—provided the foundation for their successes. It is high time that we revised our historical accounts of this music to acknowledge their contributions.

Headline image credit: Sappho. Portrait by Gustave Moreau. Public domain via WikiArt.

The post The love song and its complex gender history appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWe’ll have Manhattan: 10 hits from Richard Rodgers and Lorenz HartBreath is the basis of good singingWhat’s love got to do with it?

Related StoriesWe’ll have Manhattan: 10 hits from Richard Rodgers and Lorenz HartBreath is the basis of good singingWhat’s love got to do with it?

What’s love got to do with it?

‘The deepest need of man is the need to overcome his separateness, to leave the prison of his aloneness.’ (Fromm, E. 1957)

The time of year approaches that has gaggles of teenage girls quivering anxiously in school corridors: outwardly bemoaning the late arrival of the postman, while inwardly breathing a huge sigh of relief. At the other end of the spectrum, jaded 75-year-old-long-marrieds dust off last year’s card, re-presenting it safe in the knowledge that (a) it won’t be remembered and (b) he won’t care that much either way. It’s a day that hints at the arrival of Spring, when a question mark can create a frisson of excitement in a recipient or a knowing smile from a long-suffering spouse.

Saint Valentine’s Day, where millions of British pounds are spent on grand, kitsch, or anonymous romantic gestures (chocolate, flowers, lacy underwear, and dinner reservations, not necessarily in that order). It’s become a British industry. It celebrates love or as Samuel Johnson put it, the ‘triumph of hope over experience’.

Valentine’s Day juxtaposes our desire for romance at its best. At its worst, it exemplifies another defining contemporary human characteristic: consumerism. This Western tradition can be tenuously traced back to Valentine of Terni, martyred circa AD 197, for his Christianity. Another possible origin, Valentine of Rome, circa AD 289, was imprisoned for continuing to wed soldiers after Claudius had outlawed marriage, decreeing armies of single men fought better than those distracted by conjugal delights. Awaiting execution, Valentine is reported to have cured the jailer’s daughter of blindness and fallen in love, his final letter to her signed, ‘from your Valentine’.

Historian Noel Lenski, classics professor at the University of Colorado, has unearthed evidence to suggest an ancient pagan fertility festival on 14th February. Lupercalia, a celebration of love, which saw young Roman men strip naked and use goat skins to brush the backsides of young women and crop fields to improve fertility, followed by a matchmaking lottery where men drew women’s names from a jar. Little wonder card manufacturers have chosen to shift their focus from death, sadism, imprisonment, and swinging, from whence Valentine’s Day tradition is suggested to have sprung.

From a partisan standpoint, as a couple psychotherapist, the idealised romance of Valentine’s Day with its fantasy-laden, unconscious projection onto a ‘love object’ is not necessarily good news. The lover’s notion, that the strength of his emotion will ensure a yearned for relationship metamorphoses into a-glorious-sunset-happy-ending, doesn’t predict a stable, long-lasting, and fulfilling relationship. Come to that, neither does love at first sight or your partner resembling one of your parents. And yet romantic gesture, prolific at a relationship’s birth, is the bedrock of most unions and forms part of their narrative. Just ask a couple how they met.

The romantic notion of reality (two individuals from similar socio-economic backgrounds, attracted by their differences/irritating and lovable idiosyncrasies) becoming fantasy (thinking as one, able to read each other’s mind and anticipate each other’s needs) can be traced back to the Bible, ‘Wherefore they are no more twain, but one flesh. What therefore God hath joined together, let no man put asunder’ (Matthew, 19.6).

For the Victorians, love was a periphery consideration. A relationship between a man and a woman was a business contract between two families, with the woman as product and land as prize. Choice in love is a new Western trend. Forced by female emancipation and latterly such freedoms as same-sex relationships, emphasis has shifted away from acreage and towards how to attract a partner, how to fashion yourself as the prize.

Erich Fromm in his seminal work The Art of Loving, advocates love as a skill, to be honed and worked at, requiring knowledge and effort, rather than ‘something one falls into if one’s lucky’. From a consulting room vantage point, the idea of a relationship created between a couple that takes work and attention can come as something of a revelation. There is often real confusion between a falling in love state for couples and the permanent state of being in love. ‘I don’t feel the same about her as when we met and it’s making me depressed,’ is not an unfamiliar complaint.

Falling in love is an exhilarating, almost psychotic experience for everyone that is fortunate enough to feel it. The tragedy is that this new and precious intimacy, triggered by sexual attraction, is impossible to sustain. The infatuation stage, where everything else falls away, is commonly described as a ‘coming home feeling’, where a sense of familiarity nestles amongst the thrill. The bad news is it burns itself out. Nothing except the most dangerous attraction can sustain that undiluted intensity. Who would do the work? Captains of Industry would just stay in bed. Reality must test each new relationship. Can it survive meeting the in-laws? When do the stains on her teeth come into focus – and hopefully not matter. When do the stresses of work and mundane domesticity creep back into consciousness?

Many couples seeking help with their relationship are burdened with the expectation that their love should feel natural; fulfilment of sexual desire, rather like the Holy Spirit, should be around at all times, despite inhabiting a time-pinched world of Internet dating, Viagra, and plastic surgery. They feel that loving should be accompanied by an ease and constant lightness, and so feel cheated or deficient, even deviant in some way when it doesn’t feel like that. Their internal echo of why isn’t every day like Valentine’s Day infuses their relationship with an uncomfortable and unspoken ennui.

So where is the relationship advice at this most quixotic of times? As Valentine’s Day dawns, perhaps Honore de Balzac’s suggestion in ‘La physiologie du marriage’ will resonate: ‘No man should marry until he has studied anatomy and dissected at least one woman.’ Permit a translation. Take it slow, have some fun, keep past relationships in mind, especially that of your parents, and remember, ‘Love is, above all, the gift of oneself.’ (Anouilh, J. 1948)

Headline image credit: Heart. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post What’s love got to do with it? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDid you say millions of genomes?The economics of chocolateWe’ll have Manhattan: 10 hits from Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart

Related StoriesDid you say millions of genomes?The economics of chocolateWe’ll have Manhattan: 10 hits from Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart

Did you say millions of genomes?

Watching the field of genomics evolve over the past 20 years, it is intriguing to notice the word ‘genome’ cozying up to the word ‘million’. Genomics is moving beyond 1k, 10k and 100k genome projects. A new courtship is blossoming.

The Obama Administration has just announced a Million Genomes Project – and it’s not even the first.

Now both Craig Venter and Francis Collins, leads of the private and public versions of the Human Genome Project, are working on their million-omes.

The company 23andMe might be the first ‘million-ome-aire’. By 2014, the company founded by Ann Wojcicki processed upwards of 800,000 customer samples. Pundit Eric Topol suggests in his article “Who Owns Your DNA” that without the skirmish with the FDA, 23andMe would already have millions.

In 2011, China’s BGI, the world’s largest genomics research company, boldly announced a million human genomes project. Building on projects like the panda genome and the 3000 Rice Genomes project, the BGI is building new next-generation sequencing technologies to support its flagship project.

Also in 2011, the United States Veterans Affairs (VA) Research and Development program launched its Million Veteran Program (MVP) aiming to build the world’s largest database of genetic, military exposure, lifestyle, and health information. The “large, diverse, and altruistic patient population” of the VA puts it ahead of the others in collecting samples.

Venter’s path will be through his non-profit Human Longevity, Inc (HLI), launched in San Diego, California in 2014 with $70 million in investor funding. To support the company’s tagline — “It’s not just a long life we’re striving for, but one which is worth living” — Venter aims to sequence a million genomes by 2020.

At a price tag of $1000 dollars per genome, one million genomes could cost a billion US dollars. The original human genome project cost $3 billion only 13 years ago, but produced 1 trillion US dollars in economic impact.

The Collins’ ‘million-ome’ will pull together new and existing genomes, with an initial budget of $215 million dollars. This includes genomes from the MVP, which has already enrolled 300,000 veterans and sequenced 200,000. The focus will initially be on cancer but subjects will be healthy and ill, men and women, old and young; it is the foundation of a Precision Medicine Initiative.

3D DNA, © digitalgenetics, via iStock.

3D DNA, © digitalgenetics, via iStock. In addition to these projects we will have millions anyway. ARC Investment Analysis suggested we could see 4 to 34 billion human genomes by 2024 at historical rates of sequencing – if current trends in dropping costs and demand continue.

How could we have more genomes than humans living on earth? Cancer genomics is in ‘gold rush’ phase. Steve Jobs was famously one of the first 20 people to have his genome sequenced. He paid $100k but did so to also have the genome of the cancer that killed him sequenced. He left a personal genomics legacy to the world, but his investment in DNA sequencing also serves as a reminder that a genome is not the same as a cure. Hopes are high, though, especially for cancer diagnostics. The International Cancer Genomics Consortium is already backed with a billion dollar budget and the field continues to explode.

Further, an adult human body consists of 37 trillion genomes all working together (plus the 100 trillion genomes of the microbial cells in our microbiome). There is mounting evidence we are all genomic mosaics, meaning we all have more than one genome (e.g. from pre-cancerous cells, transplants, and mothers who carry the genomes of past live-born babies).

It is good to cultivate a healthy skepticism and not be drawn into the hype. Critics exist, as always. At the other end of the continuum, Ken Weiss of The Mermaid’s Tale blog, a geneticist himself, has outlined reasons to put valuable research dollars elsewhere than a million genomes project or precision medicine, but given than they will happen, he also contemplates what should be done with resulting data.

Eric Topol said in response to the rise of ‘million-ome’ projects, that there are now many 100k projects and he “might rather have 100,000 people with ‘pan-oromic definition’ than 1 million with just native DNA”. By high definition he means all the mapping (sensors, anatomy, environmental quantified, gut microbiome, etc.) that belongs to his vision of a “Google medical map”.

There are huge differences between “projections,” “announcements,” and “hard (published) data.” Big projects can fall by the way-side. 23andMe hit a barrier with the FDA decision. The BGI is still tooling up. Obama hasn’t yet secured a budget. Venter is giving himself time. Everyone is starting to think about genomes inside the systems in which they exist in (cells, organs, organisms, ecosystems).

Regardless of trajectory, it is a foregone conclusion that, counting all sources, the number of sequenced genomes will pass one million in 2015, if it hasn’t already.

Google is imagining the day when researchers compute over millions of genomes and is building the infrastructure to support it; Google Genomics has launched offering $25/year pricing to hold your genome in the Cloud.

Why stop at millions? Jong Bhak is calling for billions. He is suggesting that “the genomics era hasn’t even started.” Bhak, a leader of the Korean Personal Genomes Project, a project to sequence the genomes of all 50 million Koreans, has outlined a vision for a Billion Genome Project.

The first to talk of ‘a genome for everyone’ was perhaps George Church, technologist and founder of the Personal Genome Project. He wrote 2005 a paper entitled “The Personal Genome Project.” In it he recalled talking with Wally Gilbert that “Six billion base pairs for six billion people had a nice ring to it”—back in 1976, soon after Gilbert invented DNA sequencing, for which he won a Nobel Prize.

The fact that more voices in global science are debating the pros and cons of ‘millions and billions of genomes’ is evidence that 2015 marks a shift towards a Practical Genomics Revolution. It is becoming practical to think big(ger).

The post Did you say millions of genomes? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe practical genomics revolutionFive tips for women and girls pursuing STEM careersKin selection, group selection and altruism: a controversy without end?

Related StoriesThe practical genomics revolutionFive tips for women and girls pursuing STEM careersKin selection, group selection and altruism: a controversy without end?

February 11, 2015

We’ll have Manhattan: 10 hits from Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart

With the catchy melodies of Richard Rodgers’ music, and the cheeky wit of Lorenz Hart’s lyrics, the early collaborative songs of Rodgers-and-Hart are characteristic of 1920s jazz at its finest — and some of the best examples of early classics from the Great American Songbook. Most of the shows from this period have sunk into obscurity, but the songs have stood the test of time. You won’t be able to resist tapping your feet along to these ten great hits!

“Any Old Place with You”

Bob Shaver

This was the first Rodgers and Hart song to feature in a Broadway show. It was snapped up by Lew Fields (formerly of the celebrated Weber and Fields vaudeville act) for his 1919 show A Lonely Romeo. At the time, the boys thought they had made the big time, but it would be another six years before they really struck success. Lew Fields would go on to be one of their most committed supporters, producing several of their 1920s shows; his son Herbert also became their most significant lyricist throughout the 1920s.

“Manhattan”

Ella Fitzgerald

“Manhattan” was the first real hit the boys would have, though its first incarnation was in the unperformed show Winkle Town (1923), written by Rodgers and Hart with a script by Herbert Fields and Oscar Hammerstein II. The boys played the score of Winkle Town to producer Max Dreyfus. “There’s nothing of value here,” was his response. The rest is history. It’s interesting to listen to this song and “Any Old Place With You” together though—they’re similar songs, but you can hear a transition from the old style of “Any Old Place” to the jazz-age informality of “Manhattan.” This is Ella Fizgerald singing the song, one of the superlative interpreters of Rodgers and Harts’ songbook.

“Mountain Greenery”

Matt Dennis

The success of one Garrick Gaieties almost inevitably spawned a second. Many of the same team reunited, and although the result was not as striking as their previous effort, The Garrick Gaieties of 1926 was still a success. In “Mountain Greenery” the boys penned a riposte to the urban delight of “Manhattan”. Here the cosy couple imagine a country retreat in a song that really showcases the trademark Rodgers and Hart style of the period: catchy music and witty lyrics with a wealth of outrageous rhymes.

“Here in My Arms”

Phyllis Dare / Jack Hulbert

Finally, the boys got to write their own full-length show, an American Revolutionary tale recounting the British invasion of Manhattan. In Dearest Enemy (1925), an American girl falls in love with a British Officer before thwarting the invasion under his nose. Their main love song, reprised throughout the show, was “Here In My Arms”. Only a year later, the boys would be summoned to London’s West End to produce a show for British audiences. “Here in My Arms” received its second outing in Lido Lady (1926), though British reviewers were not as favourable as the New York press. Here is the original recording from the 1926 production of Lido Lady, featuring Phyllis Dare and Jack Hulbert.

“The Girlfriend / The Blue Room”

Richard Rodgers

1926 marked the most successful year yet for Rodgers and Hart, now firmly part of the Lew Fields stable and churning out hit after hit. The Girlfriend was one of their biggest successes, featuring a number of songs that would become representative of their 1920s style, featuring prominently the new jazz sound of the Charleston. The title number from the show later served as inspiration for the 1950s British pastiche, The Boyfriend. Here, Richard Rodgers himself offers his take on both “The Girlfriend” and “The Blue Room,” capturing poignantly the infectious sound that epitomizes the character of the 1920s.

“This Funny World”

Susannah McCorkle

One of Rodgers and Hart’s least auspicious shows was the Florenz Ziegfeld-produced Betsy (1926). This was written at a time when the boys were at their height, and very busy—indeed another of their shows, Peggy-Ann, opened on Broadway the previous evening. Perhaps they were simply too busy to do both shows justice. The intended hit song, written for star Belle Baker, was “This Funny World,” a charming, rueful ballad. To their horror, Ziegfeld decided it wasn’t good enough, and without even consulting the boys, he replaced this with Irving Berlin’s “Blue Skies,” which was a tremendous success. Not for the first time Rodgers and Hart would have their noses put out by this snub, following which Rodgers did not speak to Berlin for ten years. Here’s Susannah McCorkle in a quintessentially 1970s recording of the song.

“My Heart Stood Still”

Rod Stewart

Despite a troubled experience on their first trip to England, Rodgers and Hart were soon enticed back by producer C.B. Cochran to write another revue. One Dam Thing After Another (1927) allowed them to explore a number of ideas that would feature in subsequent shows, and one song in particular (“My Heart Stood Still”) travelled back across the Atlantic to become just one of several hits in A Connecticut Yankee (1927). This recording features Rod Stewart, offering a recent version from his Great American Songbook period.

“To Keep My Love Alive”

Anita O’Day

Above all, the Rodgers and Hart songbook is full of wit and irreverence. Here is one of their classic comedy numbers, “To Keep My Love Alive” from A Connecticut Yankee (1927), their biggest hit of the 1920s, in which Queen Morgan Le Fay sings of the various ways she has dispatched her lovers. It’s sung by Anita O’Day, who captures the casual attitude of the character whilst creating a great swing version of the song.

“Thou Swell”

Sammy Davis, Jr.

One of Rodgers and Hart’s most celebrated hits, this song has been covered numerous times. It really captures the whole conceit of A Connecticut Yankee (1927)—the juxtaposition of dialogue from the time of King Arthur and the modern day, encapsulated in the title alone. Here, Rodgers is at his jazzy best and Hart is preposterous in the way he rhymes nonsense words, archaic phrases, and contemporary slang—classic 1920s musical comedy! Here’s Sammy Davis, Jr. milking the verse only to give the refrain his characteristically virtuosic rendition.

“You Took Advantage of Me”

Bobby Short

By the late 1920s, Rodgers and Hart’s 1920s success was beginning to wane. They would reappear in the 1930s to even greater success, but the turn of the decade marked a period of reflection and a flirtation with Hollywood. From this period, the shows they produced produced far fewer song hits. But here is one, from Present Arms (1928), which has become a household standard. Here, Bobby Short gives some class and pizzazz to “You Took Advantage of Me”.

The full playlist:

Headline Image: New York City. CC0 License via Pixabay

The post We’ll have Manhattan: 10 hits from Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBreath is the basis of good singingReligion and the social determinants of healthTrains of thought: Zac

Related StoriesBreath is the basis of good singingReligion and the social determinants of healthTrains of thought: Zac

Our habitat: threshold

One does not have to be a specialist to suggest that threshold is either a disguised compound or that it contains a root and some impenetrable suffix. Disguised compounds are words like bridal (originally, bride + ale but now not even a noun as in the past, because -al was taken for the suffix of an adjective) or barn, a blend of the words for “barley,” of which only b is extant, and Old Engl. earn “house.” I cited æren ~ earn in the post on house. Nor is it immediately clear whether we are dealing with thresh-old or thresh-hold. Some of our earlier etymologists (among them Junius, 1743, in a posthumous edition of his dictionary, and Mahn, the 1864 editor of etymologies in Webster) thought that threshold was indeed thresh + hold. They were wrong. An attempt to identify -shold with sill is a solution born of etymological despair. This Germanic word for “threshold” was opaque as far back as the time of the oldest written monuments. For some reason, Latin limen and Russian porog (stress on the second syllable), both meaning “threshold,” also lack a definitive etymology.

The attested forms are many. Old English had þrescold, þerxold, and even þrexwold (þ = th), which shows that the word’s inner form made little sense to the speakers. Thus, -wold meant, as it more or less still does, “forest.” Hence the persistent belief that the threshold is a board or a plank on which one thrashed. This interpretation survived the first edition of Skeat’s dictionary (about which more will be said below) and surfaced in numerous books derivative of it. But wold never meant “wood, timber.”

Swedish tröskel and Norwegian terskel go back to Old Norse þresk(j)öldr, which, like its Old English congener, underwent several changes under the influence of folk etymology; the second element was associated with the Old Norse word “shield.” The fact that the threshold has nothing to do with shields did not bother anyone; folk etymology gets its nourishment from outward similarity and ignores logic. Old High German driscubli ~ driscufli live on only in dialects. The Standard Modern German word for “threshold” is Schwelle, a cognate of Engl. sill, as, among others, in windowsill.

On the threshold.

On the threshold. The Scandinavian forms look like the English ones, but those of the Low (= northern) German-Dutch-Frisian area bear almost no resemblance to them. Modern Dutch has drempel and dorpel. The suffix -el causes no problems. The fact that in drempel r precedes the vowel, while in dorpel r follows it, can be explained away as a typical case of metathesis (see Old Engl. þrescold and þerxold, above). An extra m in drempel need not embarrass us either, for such nasalized forms are plentiful. Thus, Engl. find may be allied to Latin petere “to seek,” and if it is not, there are dozens of other examples. Consider stand—stood; though, when one word requires so much special pleading, some feeling of unease cannot be avoided. The English noun makes us think of thrash and its doublet thresh, while Dutch drempel seems to be cognate with Engl. trample. Now the threshold comes out as that part of the floor on which we tread, rather than thrash, though neither trample nor especially thresh ~ thrash are close synonyms of tread. In making this argument, Germans often glossed threshold as Trittholz (Tritt “step,” Holz “wood”).

Jacob Grimm, who sometimes made mistakes but never said anything that failed to provoke and enrich thought, believed that threshold designated the part of the house in which corn was threshed or stamped upon (stamping constituted the primitive system of threshing) and had some following, but Charles P. G. Scot, the etymologist for The Century Dictionary, noted that “the threshing could not have been accomplished on the narrow sills which form thresholds, and it was only in comparatively few houses that threshing was done at all.” Some time later Rudolf Meringer, who devoted much energy to researching people’s material culture in the German and Slavic-speaking areas, said the same. He pointed out that, as a general rule, the oldest Germanic threshing floors were situated outside living houses and that the only exceptions could be found in Lower Saxony.

Not without some reluctance we should accept the conclusion that in the remote past the threshold denoted an area next to the living quarters, rather than what we today understand by this word, assuming of course that thresh- in threshold is identical with thresh ~ thrash. However, this assumption seems inevitable. The verb in question could perhaps at some time mean “rub,” as shown by the possible cognates of thrash ~ thresh in Latin (terere) and Russian (teret’; stress on the second syllable), not “beat repeatedly and violently.” Yet this nicety will only obscure the picture, for the threshold was not a board people’s feet “rubbed.”

We should now turn our attention to -old. The OED, in an entry published in 1912, cautiously identified thresh- with the corresponding verb and called the residue of threshold (that is, -old) doubtful. The much later Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology shifted accents somewhat: the first element is said to go back to Old Engl. þerscan, retained as Modern English thrash in the primitive sense of “tread, trample,” while the second element is called not identifiable, which sounds more ominous than “doubtful.” (The entry has yet to be revised as part of OED‘s current comprehensive revision.) In my opinion, the situation with the second element is not so hopeless.

The famous German linguist Eduard Sievers isolated the ancient suffix -ðlo (ð = th in Modern Engl. the). Its existence cannot be put into question, and it is still almost discernible in words like needle. Sievers reconstructed the etymon of threshold as þersc-o-ðl(o). Old High German drisc-u-bli (see it above) looks almost like his etymon. In that form, ðl changed to dl and allegedly underwent metathesis: dl to ld (a common process: even needle has been recorded in the form neelde); hence threshold. Skeat must have read the article suggesting this reconstruction too late (it is not for nothing that the Germans sometimes accused him of not following their publications!), but, once he became familiar with it, he accepted Sievers’s reconstruction with undisguised enthusiasm. Although he usually reported new findings in his Concise Dictionary, strangely, for many years the old derivation remained the same in the subsequent editions of the smaller book, despite the fact that in his ambitious work Principles of English Etymology (1887) the new solution was presented as self-evident. Surprisingly, the last Concise published in his lifetime appeared in two versions. In one, Sievers is only mentioned; in the other, the reference to the volume and page is given, exactly as in a note published many years earlier. This shows that even an accurate reference can be misleading and lead critics astray.

The line shows the border of the territory to which the Romans laid claim. It was called limes, that is, “threshold.” Engl. limen, limit, and subliminal have the root of limes.

The line shows the border of the territory to which the Romans laid claim. It was called limes, that is, “threshold.” Engl. limen, limit, and subliminal have the root of limes. I don’t know the reason for the OED’s caution (in 1912), seeing that Sievers’s article appeared in 1878 and that Skeat first defended it in print in 1885. Some dictionaries follow Sievers, but isolate the suffix -wold in threshold. One of the Old English forms did end in -wold, but, as noted, it must have been the product of folk etymology. Scandinavian scholars are especially prone to favoring this suffix because the Old Norse for thrash ~ thresh was þryskva, but þryskva can be dismissed as a doublet of þreskja. Besides, once we allow w in the suffix to take a permanent place, there is no way of getting rid of it in other forms.

Thus, threshold is less troublesome than our reference books sometimes make it out to be. At one time, it appears, the threshold was not part of a doorway. The word’s original form became obscure quite early and produced a whole bouquet of folk etymological doublets. Old High German driscubli stands especially close to the sought-after etymon. Most probably, the threshold was a place where corn was threshed (a threshing floor). The word contained a root and a suffix. That suffix has undergone numerous changes, for people tried to identify it with some word that could make sense to them. What remains unclear is not this process but the semantic leap. We are missing the moment at which the threshing floor, however primitive, began to denote the entrance to the room.

Image credits: (1) ‘Dweller on the Threshold’ by Arthur Bowen Davies, circa 1915. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Hadrian’s Wall. Photo by Glen Bowman. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Our habitat: threshold appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOur habitat: one more etymology brought “home”Monthly gleanings for January 2015Our habitat: house

Related StoriesOur habitat: one more etymology brought “home”Monthly gleanings for January 2015Our habitat: house

Discussion questions for Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights

Last week we announced the launch of the Oxford World’s Classics Reading Group, and the first book, Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë. Helen Small, editor of the Oxford World’s Classics edition of the book, has put together some helpful discussion questions that will help you gain a deeper understanding of the text as you read it and when you finish it.

Even the early critics who were revolted or dismayed by the violence of Wuthering Heights admitted the ‘power’ of the novel. What seems to you to be the best explanation of that power? How ‘moral’ a story is Wuthering Heights? More specifically, is moral justice a concern in the shaping of the story and its characters? Catherine Earnshaw comes across as many things: passionate, rebellious, full of laughter and of scorn for others, driven by social ambition but careless of social expectations, self-seeking but ultimately self-destructive (willing herself to die). Is it a problem for our reading of her that we never hear her voice unmediated? How far did you feel inclined to trust what you are told of her by others?

Heading image: Top Withens by John Robinson. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Discussion questions for Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAnnouncing the Oxford World’s Classics Reading GroupEmbark on six classic literary adventuresBreath is the basis of good singing

Related StoriesAnnouncing the Oxford World’s Classics Reading GroupEmbark on six classic literary adventuresBreath is the basis of good singing

Warm father or real man?

In 1958, the prominent childcare advice writer and pediatrician Dr. Benjamin Spock told readers that ‘a man can be a warm father and a real man at the same time’. In this revised edition of the bestseller Baby and Child Care, the American author dedicated a whole section to ‘The Father’s Part’. This was a much lengthier discussion of men’s role in caring for their babies and young children than in the first edition, but the role of the father remained very much secondary to that of the mother. Though Spock advised readers it was ‘the wrong idea’ to consider childcare as the sole responsibility of the mother, it was clear that he thought the father’s responsibility in day-to-day care remained rather minimal, in part because of the lack of interest of fathers themselves. He added that it was ‘Better to play for fifteen minutes enjoyably, and then say, “Now I’m going to read my paper,” than to spend all day at the zoo, crossly.’

Having children had long been understood as a sign of manhood, proving men’s virility and adult status. Jim Bullock, for example, who was born in 1903, recollected the definite ideas around virility and masculinity in the mining village of Bowers Row in Yorkshire. He described:

The first child was conceived as soon as was decently possible, for the young husband had to prove his manhood. If a year passed without a child—or the outward sign of one being on the way—this man was taunted by his mates both at work and on the street corner by such cruel remarks.

He added that men were expected to suffer some of the same symptoms as their wife during pregnancy, such as morning sickness and toothache, as well as losing weight as their wife gained it. If he didn’t experience these effects, his love for and fidelity to his wife could be questioned.

With increasing knowledge about birth control, sex, and childbirth across many parts of British society as the twentieth century progressed, these views became outdated.

Having children was still a sign of achieving adult masculinity. However, too much interaction with anything to do with pregnancy, birth and babies could also be emasculating—this was, of course, ‘women’s business’. David, a labourer from Nottingham, who became a father in the 1950s, highlighted how he kept his distance from both the birth and caring for his new baby, ‘because it wasn’t manly’.

Some fathers were becoming more willing to help out with children. Mr. K from Preston described how ‘relaxing’ he found it to sit giving one of his babies a bottle after work. Yet, though attitudes to men’s roles in childcare were gradually shifting, it was the relationship between masculinity and fatherhood that changed more substantially in the middle of the twentieth century.

What can be found in the 1940s and 1950s in Britain was a new kind of relationship between fatherhood and masculinity. This was, in fact, a time when the ‘celebrity dad’ became prominent in the press. In 1955, for example, the Daily Mirror published a feature on actor Kenneth More, interviewed whilst he took care of his toddler. In 1957, it featured an article and large image of the singer Lonnie Donegan with his three-year-old daughter, apparently enjoying singing together at home. Sports stars and royals were also the subject of this kind of attention, and seemed to embody Spock’s claim that men indeed could be a real man and a warm father at the same time. More ‘ordinary’ dads also hinted at this change. Whilst taking an overly active role in the physical care of babies remained potentially tricky for many men, their identities were increasingly encompassing a more caring and fatherly side. Mr. G, born in 1903, suggested that there was change around the First World War; by the 1920s, men were much happier to be seen taking their child for a walk in the area he lived in Lancashire. And Martin from Oldham, whose first child was born in the mid-1950s, described how he proudly took his child in its pram for a beer in his local pub. Men’s roles with their children hadn’t been radically reshaped. But whilst in earlier generations, it was simply having children that was a sign of manliness, by the 1950s, being seen as an involved father was becoming part of an ideal vision of masculinity.

The importance of fatherhood to the achievement of certain ideal of masculinity has ebbed and flowed across the twentieth century; it could both prove and challenge a sense of manliness. Today we see plenty of evidence of men proudly displaying their fatherhood—the man with a pram or carrying a baby in a sling isn’t so rare any more. Yet, in every generation there are more or less involved fathers; plenty of men throughout the twentieth century, and much earlier, enjoyed spending time with their children and felt close to them. Today, women, for the most part, still take on the burden of childcare, even if there are plenty of couples who do things differently. Historical research helps question the idea that the ‘new man’ of the last couple of decades is quite so new—and by thinking about how fatherhood relates to masculine identity, we can better understand changes to parenting and gender roles over time.

Image Credit: “Father’s Strength” by Shavar Ross. CC by NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Warm father or real man? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAn African American in Imperial Russia: the story of Frederick Bruce ThomasFighting the threat withinWhy are missionaries in America?

Related StoriesAn African American in Imperial Russia: the story of Frederick Bruce ThomasFighting the threat withinWhy are missionaries in America?

The economics of chocolate

Cocoa and chocolate have a long history in Central America but a relatively short history in the rest of the world. For thousands of years tribes and empires in Central America produced cocoa and consumed drinks based on it. It was only when the Spanish arrived in those regions that the rest of the world learned about it. Initially, cocoa production stayed in the original production regions, but with the local population decimated by war and imported diseases, slave labor was imported from Africa.

The ‘First Great Chocolate Boom’ occurred at the end of the 19th and early 20th century. The industrial revolution turned chocolate from a drink to a solid food full of energy and raised incomes of the poor. As a result, chocolate consumption increased rapidly in Europe and North America.

As the popularity of chocolate grew, production spread across the world to satisfy increasing demand. Interestingly, cocoa only arrived in West Africa in the early 20th century. But by the 1960s West Africa dominated global cocoa production, and in particular Ghana and Ivory Coast have become the world’s leading cocoa producers and exporters.

Not surprisingly, given the growth in trade of cocoa and consumption of chocolate, governments have intervened in the markets through various types of regulations. The early regulations (in the 16th–19th centuries) focused mostly on extracting revenue from cocoa production and trade through, for example, taxes on cocoa trade and the sales of monopoly rights for chocolate production.

The world is currently experiencing a ‘Second Great Chocolate Boom.’

More recent regulations have focused mostly on quality and safety. With growing demand for chocolate in the 19th century, chocolate producers substituted cocoa with cheaper raw materials, going from various starchy products and fats to poisonous ingredients. Scientific inventions of the 18th and 19th centuries allowed better testing of the chocolate ingredients. Public outrage against the use of unhealthy ingredients (now scientifically proven), led to a series of safety regulations on which specific ingredients were not allowed in chocolate – and in countries such as France and Belgium also in a legal definition of ‘chocolate’.

Chocolate consumption has many fascinating aspects. It is bought both for the pleasure of consumption and as a gift. It has been considered a healthy food, a sinful indulgence, an aphrodisiac, and the cause of obesity.

For much of history, chocolate (or cocoa drinks more generally) was praised for its positive effects on health and nutrition (and other benefits for the human body). As people were poor, hungry, and short of energy, chocolate drinks and later chocolate bars became an important additional source of nutrition.

In recent years, chocolate consumption is often associated with negative health issues, such as obesity. Recent research has shown that its health potential is closely linked to the composition of the final product and, not surprisingly, to the quantity consumed: darker, lower-fat, and lower-sugar varieties, consumed in a balanced diet are more likely to be healthy than the opposite consumption pattern.

Fresh Cacao from São Tomé & Príncipe, by Everjean. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr

Fresh Cacao from São Tomé & Príncipe, by Everjean. CC-BY-2.0 via FlickrIn today’s high income societies where hunger is an exception, food is cheap, and obesity is on the rise, systematic overconsumption of chocolate – often associated with impulsive consumption and lack of self-control – is more associated with health problems. New research in behavioral engineering is targeted to help consumers deal with situational influences, and change behavior in a sustainable way, i.e. by ‘nudging’ them to change their consumption behavior and resisting the lure of chocolate.

One of the intriguing aspects of chocolate is its ‘quality’. Different from many other foods (such as cheese or wine) perceived chocolate quality is not related to the location where the raw material is grown or produced, but to the chocolate manufacturing process and location.

Some countries, such as Switzerland and Belgium are associated with prestigious traditions of chocolate manufacturing. However, perceptions do not always fit reality. ‘Belgian chocolates’, such as pralines and truffles, are now world famous but until 1960, Belgium imported more chocolate than it exported. Since then its “Belgian chocolates” have conquered the world – while the world has taken over the Belgian chocolate (companies). Most “Belgian chocolates” are now owned by international holdings – and a sizeable amount is produced outside the country.

Moreover, consumer perceptions of ‘quality’ are strongly influenced by consumer experiences with their local chocolate – this includes the smoothness of Swiss chocolate from long conching, the milkiness of British chocolate, and the preference of American consumers for chocolate that Europeans consider inferior.

In fact, the integration of the UK, Ireland and Denmark into the (precursor of the) European Union, which included France and Belgium in 1973 resulted in a ‘Chocolate War’ which lasted for 30 years. Disputes between the old and the new member states of the definition of “Chocolate” (and its ingredients) made that British chocolate was banned from much of the EU continent for three decades.

Ethical concerns about chocolate have been triggered by the specific structure of the structure of the global cocoa-chocolate value chain. For most of the past century, the value chain was characterized by a South-to-North orientation, with most of the raw material (cocoa beans) produced in developing countries (‘the South’) and most chocolate manufacturing and consumption in the richer countries (‘the North’). Another characteristic is that cocoa production in the South is almost exclusively by smallholders, while cocoa grinding and (first stage) chocolate manufacturing processes are often dominated by very large companies.

The cocoa-chocolate value chain has undergone significant transformations in recent years. First, in the 1960s through the 1980s the cocoa production and marketing in developing countries was strongly state regulated, often dominated by (para-)statal companies and state regulated prices and trade, etc. In recent years there has been substantial liberalizations of these sectors and the market plays a much larger role in price setting and trading, often resulting in new hybrid forms of ‘public-private governance’ of the world’s cocoa farmers.

Second, these new regulatory systems are reinforced by consumer awareness around labour conditions and low incomes in African smallholder production related to structural imbalances in the value chain. Consumer concerns and civil society campaigns around poor socio-economic conditions of producers (such as child labor) have affected companies’ strategies and responses. These involved (a) sustainability initiatives with civil society and governments, (b) certification initiatives including Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance and Utz, and (c) various forms of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) activities.

The world is currently experiencing a ‘Second Great Chocolate Boom’. Rapidly growing demand is now not coming from ‘the North’, but from rapidly growing developing and emerging countries, including China, India and also Africa. The unprecedented growth of the past decades, the associated urbanization, and the huge size of their economies have turned China and India into major growth markets for chocolate. While consumption is highest in China, and the growth is strong, the country with – by far – the highest growth rates in chocolate consumption is India. In addition, significant African growth of the past 15 years is now also translating into growing chocolate consumption on the continent where most of the cocoa beans are produced.

Headline image: Fresh Cacao from São Tomé & Príncipe, by Everjean. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post The economics of chocolate appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe influence of economists on public policyGender inequality in the labour market in the UKThe economics behind detecting terror plots

Related StoriesThe influence of economists on public policyGender inequality in the labour market in the UKThe economics behind detecting terror plots

February 10, 2015

Five tips for women and girls pursuing STEM careers

Many attempts have been made to explain the historic and current lack of women working in STEM fields. During her two years of service as Director of Policy Planning for the US State Department, from 2009 to 2011, Anne-Marie Slaughter suggested a range of strategies for corporate and political environments to better support women at work. These spanned from social-psychological interventions to the introduction of role models and self-affirmation practices. Slaughter has written and spoken extensively on the topic of equality between men and women. Beyond abstract policy change, and continuing our celebration of women in STEM, there are practical tips and guidance for young women pursuing a career in Science, Technology, Engineering, or Mathematics.

(1) &nsbp; Be open to discussing your research with interested people.

From in-depth discussions at conferences in your field to a quick catch up with a passing colleague, it can be endlessly beneficial to bounce your ideas off a range of people. New insights can help you to better understand your own ideas.

(2) &nsbp; Explore research problems outside of your own.

Looking at problems from multiple viewpoints can add huge value to your original work. Explore peripheral work, look into the work of your colleagues, and read about the achievements of people whose work has influenced your own. New information has never been so discoverable and accessible as it is today. So, go forth and hunt!

Meeting by StartupStockPhotos. Public domain via Pixabay.

Meeting by StartupStockPhotos. Public domain via Pixabay.(3) &nsbp; Collaborate with people from different backgrounds.

The chance of two people having read exactly the same works in their lifetime is nominal, so teaming up with others is guaranteed to bring you new ideas and perspectives you might never have found alone.

(4) &nsbp; Make sure your research is fun and fulfilling.

As with any line of work, if it stops being enjoyable, your performance can be at risk. Even highly self-motivated people have off days, so look for new ways to motivate yourself and drive your work forward. Sometimes this means taking some time to investigate a new perspective or angle from which to look at what you are doing. Sometimes this means allowing yourself time and distance from your work, so you can return with a fresh eye and a fresh mind!

(5) &nsbp; Surround yourself with friends who understand your passion for scientific research.

The life of a researcher can be lonely, particularly if you are working in a niche or emerging field. Choose your company wisely, ensuring your valuable time is spent with friends and family who support and respect your work.

Image Credit: “Board” by blickpixel. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Five tips for women and girls pursuing STEM careers appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCelebrating Women in STEMJonathan Nagler: writing good codeTrains of thought: Zac

Related StoriesCelebrating Women in STEMJonathan Nagler: writing good codeTrains of thought: Zac

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers