Oxford University Press's Blog, page 702

February 10, 2015

An African American in Imperial Russia: the story of Frederick Bruce Thomas

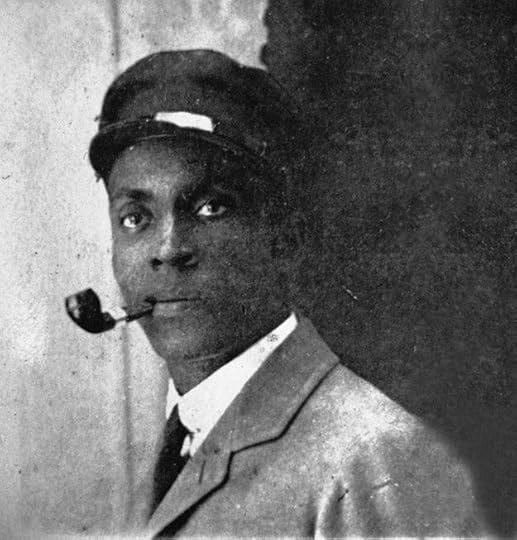

Decades before P. Diddy, Jay-Z, and Russell Simmons, there was Frederick Bruce Thomas, known later in his life as Fyodor Fyodorovich Tomas — one of the most successful African-American musical impresarios and businessmen of his generation.

Why isn’t he better known now?

The first reason is that a century ago, white America had no interest in celebrating black achievement.

The second is that he triumphed not in the United States, but in Tsarist Russia, which was one of the last places anyone would have expected to find a black American at the dawn of the twentieth century.

As we celebrate Black History Month, Thomas’s story — which until recently was virtually forgotten — provides a striking example of how blacks who fled the United States to escape racism could rise to the top of the economic pyramid in Europe and elsewhere, despite the wars, revolutions, and other hurdles they had to overcome.

Thomas was born in 1872 in Coahoma County, Mississippi and got his wings from his parents — freedmen who had become successful farmers. However, since the Thomas family lived in the Delta — which has been called the most “Southern place on earth” — their prominence was also the cause of their ruin. In 1886, a rich white planter who resented their success tried to steal their land. After fighting him as much as they could, the Thomases decided it would be prudent to get out of harm’s way and moved to Memphis.

Several decades before the Great Migration began, Thomas left the South and went to Chicago, and then Brooklyn. Seeking even greater freedom, he went to Europe in 1894, several decades before some black Americans began to seek a haven in Paris. And in 1899, after crisscrossing the Continent, mastering French, and honing his skills as a waiter and a valet, he signed on to accompany a nobleman to Russia, a country where people of African descent were virtually unknown.

Frederick Bruce Thomas, Paris, c. 1896. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Frederick Bruce Thomas, Paris, c. 1896. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Thomas’s career in Moscow proved to be more successful than he could ever have imagined. He found no “color line” there, as he put it, and in a decade he went from being a waiter to an owner of a large entertainment garden called Aquarium near the city center. Within a year of acquiring it, he had transformed a failing business into one of the most successful venues for popular theatrical entertainment in Moscow.

Were it not for the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, Thomas would have happily spent the rest of his life in his adopted country. He married twice, acquired a mistress who became his third wife, and fathered five children. He also took Russian citizenship, and was possibly the first black American ever to do so.

But when the Bolsheviks seized power, Thomas suddenly discovered that he was on the wrong side of history. His newly acquired wealth trumped his past oppression as a black man in the United States, and nothing could mitigate this class “sin.”

To save himself, Thomas fled Soviet Russia. In 1919, after surviving hair-raising perils, he managed to reach Constantinople. Although he had lost all his wealth, within three months of arriving he opened an entertainment garden on the city’s outskirts. He was the first person to import jazz to Turkey, and its popularity among the city’s natives and swarms of well-heeled tourists consolidated his success and made him rich once again.

However, after escaping from Russia, Thomas was never again free of the burden of race, and it would be his undoing. Although his skin color was of no concern to the Turks, he could not avoid dealing with the diplomats in the American Consulate General in Constantinople, or with their racist superiors in the State Department. When he most needed their help, they refused to recognize him as an American and to give him legal protection. Abandoned by the United States, and caught between the xenophobia of the new Turkish Republic and his own extravagance, he fell on hard times, was thrown into debtor’s prison, and died in Constantinople in 1928. The New York Times was one of the few American newspapers that noticed his passing, and on 8 July in an article about Constantinople, referred to him as the city’s late “Sultan of Jazz.”

Perhaps if the United States ever becomes a genuinely post-racial society, Black History Month will fade in importance. But in the meantime, we can at least try to recover and remember the lives of extraordinary individuals like Frederick Bruce Thomas.

Heading image: Red Square, Moscow. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post An African American in Imperial Russia: the story of Frederick Bruce Thomas appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe bicentenary of the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815)Fighting the threat withinAvarice in the late French Renaissance

Related StoriesThe bicentenary of the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815)Fighting the threat withinAvarice in the late French Renaissance

Breath is the basis of good singing

Giovanni Battista Lamperti (1839 – 1910), one of the first great vocal pedagogues, is quoted as saying in his Maxims that the breath is the basis of good singing.

”What is your approach to breath?” is a simple question, but the answers to this question are anything but simple. Master singers have varying ideas about breath control.

Breathing may be natural or unnatural, free or controlled, depending on the singer. Lawrence Brownlee speaks of “naturalness” and Nicole Cabell warns against it because “what seems natural could be incorrect.” Joyce DiDonato speaks of “freedom” of breath and Stephanie Blythe of “release”. Thomas Hampson advocates a conscious control of the breath.

Moreover, there are also various vocalizing techniques to command the flow of breath. Denyce Graves suggests using a hiss to control the breath flow. Another idea is the use of sirens, which helps to give a seamless sound throughout the range. An interesting suggestion from Eric Owens is to think of the inhalation as a note, an unwritten note, but a note. When the singer thinks of the inhalation as a note in the phrase, it becomes more natural and legato.

Indeed, singers may find lessons from many other areas of music. Although we are admonished that there is a difference in the more rigid support needed for the instrumentalist as opposed to the vocalist, Christine Goerke and Gerhard Siegel were thankful for their instrumental training because it helped them with their breath support. They reiterated that the singer needs flexibility in breathing or, as many say, a feeling of release, which is different from the instrumental breath support.

One recurring idea for breathing is that the breath is felt low in the body. According to Ana María Martínez, there “…is nothing high about the breath,” the breath fills the lower back with air while keeping the “…diaphragm low.” Joyce DiDnato says that one lets the air “drop like a weight”. With a certain amount of humor some suggest that the breathing is down and low, in the “bikinis,” or the belly gets “fluffy.”

But the true lesson from these masters is that each approach must be unique as each potential singer’s voice is unique. As Lamperti reminds us: “as a swimmer doesn’t fight the water, so should a singer not fight the breath.”

Headline Image: Theater Curtain. CC0 via Pixabay

The post Breath is the basis of good singing appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesReligion and the social determinants of healthTrains of thought: ZacThe impossibility of perfect forgeries?

Related StoriesReligion and the social determinants of healthTrains of thought: ZacThe impossibility of perfect forgeries?

February 9, 2015

Religion and the social determinants of health

Is religion a plus or minus when it comes to global health and the “right to health” in the twenty-first century? A little of both, I’d say, but what does that look like? For me the connection is seen most clearly in the “social determinants of health”; that is, “the everyday circumstances in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age.” This post considers a selection of photos that shape how I see social determinants intersecting with religion.

Child at the Kumbh Mela

Photo by S. R. Holman.

Photo by S. R. Holman.This child met my gaze at the 2013 Kumbh Mela, a Hindu bathing festival in rural India, where her family was working. She stands just a few yards from a new-built latrine and the faucet providing piped clean water to this workers’ camp. Simply because she is a poor girl, her chance of education is dismal and, according to recent research on maternal literacy, her literacy level will someday directly affect her children’s health. Yet unlike Americans, she lives in a nation that ratified (official accepted under law) the International Covenant on Social, Economic and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), meaning that families like hers ought to be able to enjoy equal rights to food, housing, and education. I see here a little girl hugging a beloved blanket. What do you see?

Leuven sanctuary

Photo by S. R. Holman.

Photo by S. R. Holman.This side aisle in the church of the Great Beguinage of Leuven, Belgium, reminds me that faith communities are sources for “religious health assets” (RHAs), that is, faith-based resources that contribute to individual health and the greater social good. A 2006 report of the African Religious Health Assets Programme (ARHAP) spells out a broad range of RHAs, including those that are tangible — e.g. rituals, medical facilities, education, funding, and opportunity for training in leadership — and those more intangible, e.g. prayer, advocacy, resistance, and belongingness.

Microscope and rosary

Photo by S. R. Holman

Photo by S. R. HolmanAmerican health policy today has roots in 18th- and 19th-century ideas that continue to shape decision making. My research on Dr. Henry Trevitt (whose ca. 1850 microscope is seen here) has shown me more clearly how complex connections are between medicine — individual disease treatment — and public health — which relates to groups, economics, and public policy. A Protestant Yankee, Trevitt got embroiled in a tangle of health controversies over prisoners, paupers, insanity, revolution, the medical marvel Phineas Gage, maternal mortality, and murder. The rosary here belonged to his wife who herself would die impoverished, a ward of the state.

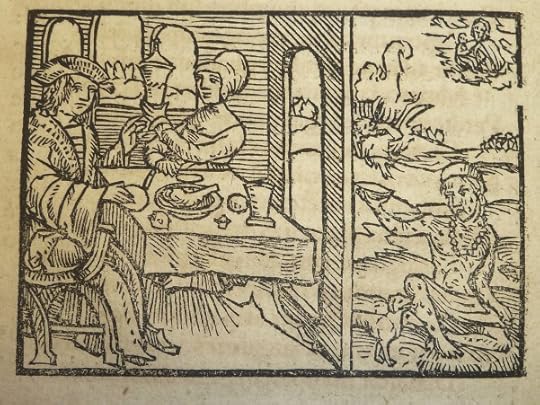

Dives and Lazarus

Woodcut illustration by Jacob Locher, used by Silvan Otmar of Augsburg (d. 1540). From the “

Provenance Online Project

” (at Penn Libraries). CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Woodcut illustration by Jacob Locher, used by Silvan Otmar of Augsburg (d. 1540). From the “

Provenance Online Project

” (at Penn Libraries). CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Global health crosses time, as our own heritage of religious tradition, class, and economics shapes present realities. The Protestant reformers who influenced so much North American policy leave us images such as this 1540 woodcut of the biblical story of Lazarus and the rich man (Luke 16:19-31). I’m struck by the spare simplicity of the rich man’s table, a contrast to our culture’s focus on “all you can eat.” But why is Lazarus wearing a necklace?

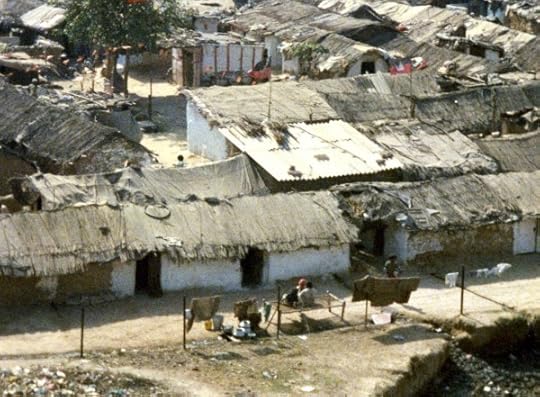

Informal settlement

Photo by S. R. Holman.

Photo by S. R. Holman.Human rights abuses often start with the rich. The Christian social worker who accompanied me through this informal settlement in urban Delhi, where residents of manifest dignity were creating beauty against impossible odds, told me how a rich NGO had taken photos of their poverty in order to profit from false charitable appeals. Katherine Boo’s recent book, Beyond the Beautiful Forevers, based on life in such an impoverished community, is a good companion for thinking about how we might engage with more responsible ethics.

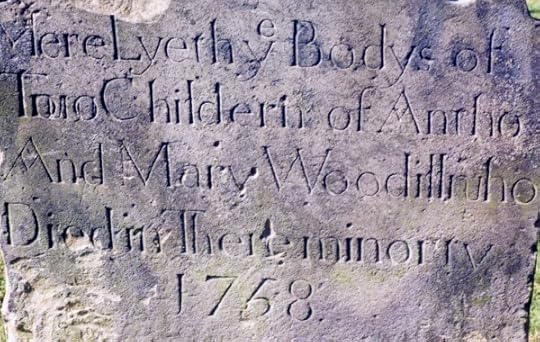

Scarborough gravestone

Photo by S. R. Holman.

Photo by S. R. Holman.This 1758 gravestone overlooking the North Sea mourns two children who died “in their minority.” Like them, more than half of the 6.3 million children under five who died around the world in 2013 also succumbed to conditions that could have been prevented or treated with better health care access. Such markers witness the fragility of children’s lives, and the role religion plays in the social fabric of such risks.

Works of mercy

Stained glass window by Lavers, Barraud and Westlake, 1884. All Saints’ Church, Mountfield, East Sussex, UK. Photo by jpguffogg. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr

Stained glass window by Lavers, Barraud and Westlake, 1884. All Saints’ Church, Mountfield, East Sussex, UK. Photo by jpguffogg. CC BY 2.0 via FlickrIn Matthew 25:31-46, illustrated here, Jesus describes faith-based “righteousness” as providing food, drink, housing, clothing, shelter, medical care, and relief to the needy. These are the same resource mandates affirmed in Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and human rights law under the ICESCR. They also define almsgiving in Islam (depicted vividly in Ismael Ferroukhi film on the hajj, “Le Grand Voyage”), Judaism, and even Hinduism, where “daan” is a secret donation that even the giver should forget.

Jerusalem street

Photo by S. R. Holman.

Photo by S. R. Holman.Sometimes the most enduring image of how religion affects health is not what you see, but what you don’t. Old Jerusalem’s alleys are narrow and usually crowded with vibrant markets, and religious pilgrims. This empty street, seen between Muslim and Christian neighborhoods a few years ago, is a haunting reminder of tensions in the body — individual and collective — that can follow when faith identities and health-related resources and practices go missing, or fail to connect equitable human rights with hope and health for all.

The post Religion and the social determinants of health appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTrains of thought: ZacOn the dark side of devoutnessThe impossibility of perfect forgeries?

Related StoriesTrains of thought: ZacOn the dark side of devoutnessThe impossibility of perfect forgeries?

The bicentenary of the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815)

The centenary of the Great War in 2014 has generated impressive public as well as scholarly attention. It has all but overshadowed some other major anniversaries in the history of international relations and law, such as the quarter-centenary of the fall of the Berlin Wall (1989) or the bicentenary of the Vienna Congress (1814–1815). As with the turn of the year the interest in the Great War seems to be somewhat subsiding, and the anniversary of the most epic and dramatic event of the Vienna period (the Battle of Waterloo of 18 June 1815) is approaching, the commemoration of the Vienna Congress gains a bit of the spotlight.

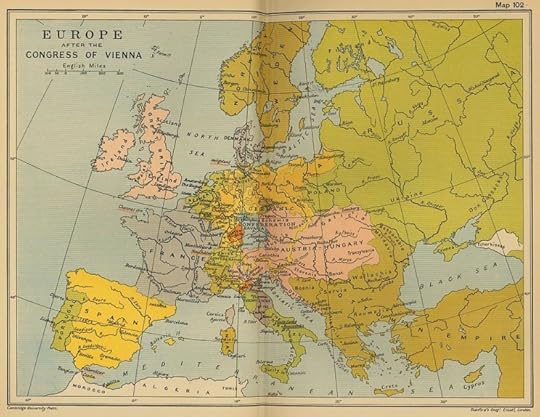

The Congress of Vienna marked the establishment of a new political and legal order for Europe after more than two decades of turmoil and war following the French Revolution. The defeat of Napoleon (1769–1821) in 1813–1814 by a huge coalition of powers under the leadership of Britain, Russia, Austria, and Prussia gave the victorious powers an opportunity to stabilise Europe. This they intended to do by containing the power of France and recreating the balance between the great powers.

At Vienna, between November 1814 and June 1815, the representatives of more than 200 European polities – many from the now-defunct Holy Roman Empire – met to debate a new European order. The Congress of Vienna stands in the tradition of great European peace conferences, beginning with Westphalia (1648) and continuing with Nijmegen (1678–1679), Rijswijk (1697), Utrecht (1713), Vienna (1738), Aachen (1748), and Paris (1763) to the Paris peace conference that ended the American War of Independence (1783). Yet, in several ways, it was also a departure from it.

Europe after the Congress of Vienna. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Europe after the Congress of Vienna. Public domain via Wikimedia CommonsAt the prior peace conferences, the major order of business had been to agree on the conditions to end war and restore peace. Whereas this implied discussions on the future order of Europe, the major interest was to settle the claims that lay at the origins of the war and the focus was thus largely backwards-looking. In the case of Vienna, peace had already been made between France and the major allies before the conference met. Peace had been formally achieved through the First Peace of Paris of 30 May 1814. This peace had taken the traditional form of a set of bilateral peace treaties between the different belligerents. In this case it concerned six peace treaties between France on the one hand and Britain, Russia, Austria, Prussia, Sweden, and Portugal on the other hand. These treaties were identical but for some additional and secret articles. Professor Parry published the treaty between France and Britain as well as these separate articles (63 CTS 171). On 20 July 1814, France concluded a seventh peace treaty with Spain (63 CTS 297). Article 32 of the identical treaties provided for a general congress at Vienna to ‘complete the provisions of the present Treaty’. The peace treaties contained the major conditions of peace, including the new borders of France. It was left to the Congress to lay out the conditions of the general political and legal order of Europe for the future.

Not even the return of Napoleon from Elba and the eruption of new war diverted the Congress from its forward-looking agenda. The congress was not suspended nor was a new peace treaty made at Vienna. After Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo and the second restoration of the Bourbons to the French throne, a new set of peace treaties was made under the Second Peace of Paris of 20 November 1815 (65 CTS 251), between France and each of the four great powers of the coalition. Numerous other powers later acceded to the peace.

As prior conferences had done, the Vienna Congress produced a whole set of – mostly bilateral – treaties. But the conference also chose an innovative form for its closing as its main conclusions were formally laid down in a general instrument, the Final Act of Vienna of 9 June 1815 (64 CTS 453). This act was signed and ratified by the seven powers which had concluded peace at Paris on 30 May 1814, with Spain and some other powers later acceding. Article 118 of the Final Act incorporated 17 treaties which had been concluded at Vienna and annexed them to the instrument, thus committing all signatories of the Final Act to them. In turn, Article 11 of the Second Peace of Paris would later confirm the Vienna Final Act, as well as the First Peace of Paris.

As it is generally established in the scholarly literature, the new order of Europe which came out of the Vienna Congress was based on two main pillars. Firstly, the Vienna powers aspired to restore and safeguard the balance of powers and made this into a leading maxim in drafting the new territorial map of Europe. This was done by reducing France to its borders of 1792 – allowing it to keep some of its conquests from the Revolutionary Period – and strengthening its neighbours. The greatest riddle to the balance of power was the future of Germany. The solution was found somewhere between the extremes of a return of the division of the Holy Roman Empire, which would have made it defenceless against new French expansionism, and its unification, which would have disrupted the balance of Europe. The new German Confederation would contain only 39 states instead of the over 300 of the old Empire. Within the Confederation, a balance was created between the two leading powers, Austria and Prussia, both of which made considerable territorial gains to ensure their capability to contain France, and each other.

Secondly, the Vienna order was built on the principle that the great powers – a group into which France retook its traditional place – would take common responsibility for the general peace and stability of Europe. The four victorious great powers had already agreed on this principle in different instruments prior to the Vienna Congress, the main one of these being the Treaty of Chaumont of 1 March 1814 (63 CTS 83). This ‘great power principle’ also determined the organisation and working of the congress itself. Although over 200 delegations were present, the major negotiations and decisions took place in the Committees of Five (Britain, Russia, Austria, Prussia, and France) and of Eight (also including Spain, Sweden, and Portugal), relegating the other powers to roles as lobbyists for their own interests. As the chief French negotiator, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord (1754–1838) had it, ‘Vienna was the Congress that was not a Congress’. The Final Act did, however, lack a provision for the future implementation of the great power principle apart from the fact that the eight great powers were bound to all its provisions and thus were all guarantors of the territorial and legal order of Europe as laid down in the act. This was remedied by the Second Peace of Paris of 20 November 1815. Article 6 of the bilateral treaty of alliance signed between Britain and Austria provided for the convening of conferences between the great powers to discuss matters of common interest and the maintenance of peace in Europe. Through its incorporation in the identical peace treaty, this committed all its signatories.

The basic features of the reorganisation of Europe from Vienna would survive for more than five decades, until the German unification. Whereas Europe was plagued by numerous armed conflicts and wars, the Vienna order proved at the same time sufficiently grounded and flexible to allow the great powers the leeway necessary to prevent these wars from escalating into a new general war. Even the disruption of the balance of power through the defeat of France in the Franco-German War and the ensuing unification of Germany in 1870 did not lead to an end to the endeavours by the great powers to manage the system and to sustain peace. The breakdown of the peace and the total conflagration of 1914–1918 destroyed the credit of one of the pillars of the Viennese settlement, the balance of power. But the other survived. Even more so, the idea that the best guarantee for order and peace was their joint management by the great powers became the backbone of the institutional organisation of collective security in the League of Nations in 1919 and the United Nations Organisation in 1945.

Headline image credit: Congress of Vienna. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The bicentenary of the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815) appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFighting the threat withinAvarice in the late French RenaissanceOn the dark side of devoutness

Related StoriesFighting the threat withinAvarice in the late French RenaissanceOn the dark side of devoutness

Trains of thought: Zac

Tetralogue by Timothy Williamson is a philosophy book for the commuter age. In a tradition going back to Plato, Timothy Williamson uses a fictional conversation to explore questions about truth and falsity, knowledge and belief. Four people with radically different outlooks on the world meet on a train and start talking about what they believe. Their conversation varies from cool logical reasoning to heated personal confrontation. Each starts off convinced that he or she is right, but then doubts creep in. During February, we will be posting a series of extracts that cover the viewpoints of all four characters in Tetralogue. What follows is an extract exploring Zac’s perspective.

Zac wants everyone to be at peace with everyone else, whatever their differences. He tries to intervene and offer a solution to the conflicts that arise between the other characters, but often ends up getting dragged in himself.

Sarah: It’s pointless arguing with you. Nothing will shake your faith in witchcraft!

Bob: Will anything shake your faith in modern science?

Zac: Excuse me, folks, for butting in: sitting here, I couldn’t help overhearing your conversation. You both seem to be getting quite upset. Perhaps I can help. If I may say so, each of you is taking the superior attitude ‘I’m right and you’re wrong’ toward the other.

Sarah: But I am right and he is wrong.

Bob: No. I’m right and she’s wrong.

Zac: There, you see: deadlock. My guess is, it’s becoming obvious to both of you that neither of you can definitively prove the other wrong.

Sarah: Maybe not right here and now on this train, but just wait and see how science develops—people who try to put limits to what it can achieve usually end up with egg on their face.

Bob: Just you wait and see what it’s like to be the victim of a spell. People who try to put limits to what witchcraft can do end up with much worse than egg on their face.

Zac: But isn’t each of you quite right, from your own point of view? What you—

Sarah: Sarah.

Zac: Pleased to meet you, Sarah. I’m Zac, by the way. What Sarah is saying makes perfect sense from the point of view of modern science. And what you—

Bob: Bob.

Zac: Pleased to meet you, Bob. What Bob is saying makes perfect sense from the point of view of traditional witchcraft. Modern science and traditional witchcraft are different points of view, but each of them is valid on its own terms. They are equally intelligible.

Sarah: They may be equally intelligible, but they aren’t equally true.

Zac: ‘True’: that’s a very dangerous word, Sarah. When you are enjoying the view of the lovely countryside through this window, do you insist that you are seeing right, and people looking through the windows on the other side of the train are seeing wrong?

Sarah: Of course not, but it’s not a fair comparison.

Zac: Why not, Sarah?

Sarah: We see different things through the windows because we are looking in different directions. But modern science and traditional witchcraft ideas are looking at the same world and say incompatible things about it, for instance about what caused Bob’s wall to collapse. If one side is right, the other is wrong.

Zac: Sarah, it’s you who make them incompatible by insisting that someone must be right and someone must be wrong. That sort of judgemental talk comes from the idea that we can adopt the point of view of a God, standing in judgement over everyone else. But we are all just human beings. We can’t make definitive judgements of right and wrong like that about each other.

Sarah: But aren’t you, Zac, saying that Bob and I were both wrong to assume there are right and wrong answers on modern science versus witchcraft, and that you are right to say there are no such right and wrong answers? In fact, aren’t you contradicting yourself?

Have you got something you want to say to Zac? Do you agree or disagree with him? Tetralogue author Timothy Williamson will be getting into character and answering questions from Zac’s perspective via @TetralogueBook on Friday 13th March from 2-3pm GMT. Tweet your questions to him and wait for Zac’s response!

The post Trains of thought: Zac appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTrains of thought: BobThe impossibility of perfect forgeries?On the dark side of devoutness

Related StoriesTrains of thought: BobThe impossibility of perfect forgeries?On the dark side of devoutness

February 8, 2015

A history of paleontology in China

Life is the most exquisite natural outcome on our planet, arising as an evolutionary experiment that has persisted since the formation of this planet 4.5 billion years ago.

The enormous biodiversity we see today represents only a small fraction of life that has existed on earth. As the most intelligent (and probably lucky!) species, we humans, with our unique and conscious minds, have never stopped inquiring where we came from.

By unearthing and examining fossils—petrified remains left behind by prehistoric organisms—paleontology deciphers the biological messages of past organisms.

Fossils were discovered early in human history, and their meaning was interpreted in various ways by Western wisdom and by Chinese naturalists for over 2000 years.

Paleontology as a scientific discipline took shape in 18th-century Europe and grew quickly during the 19th century. After Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, paleontology as a school of natural sciences refocused on understanding the evolutionary path of life.

Along with developments in geology, biology, and modern technology in the 19th and 20th centuries, the traditional practice of paleontology using morphology, taxonomy, and biochronology evolved into a form that is equipped with multidisciplinary approaches and is technically and methodologically sophisticated. New concepts, theories, and methods that developed along with the appearance and progress of plate tectonics, radiometric dating, stable isotopic studies, and molecular biology are now blended into the blood of traditional paleontology.

Searching for the mechanisms behind the diversification of life, mass extinctions, and the paleoenvironmental background, paleontology has been brought to a new stage in which organisms and their surroundings have become a single multifaceted research subject commonly tackled by joint international teamwork.

Paleontology in China has blossomed into a strong research enterprise during the last two decades, thanks to an enriched intellectual atmosphere, the energy of a promising economy, and the groundwork laid by generations of scientists.

China contains rich and unique fossil resources, such as the Precambrian Weng’an Biota, the early Cambrian Chengjiang Biota, and the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota, to name but a few. Numerous important fossils, some of which are considered to be ‘missing links’ in the chain of organismal evolution, have been discovered in the strata of various geologic time intervals.

Research on these fossils has significantly advanced our knowledge of the history of life as a whole.

Discoveries are forever, and our efforts to search for the history of life are endless. What has been achieved in paleontology in China is undoubtedly superb, but it is only the opening statement of an influential speech; much remains to be said in the decades to come. The great potential for research opportunities needs to be cultivated and numerous scientific problems remain to be solved. Looking into the history of life, we see a bright future for the study of paleontology in China and the rest of the world.

Image Credit: “Death Throw.” Photo by Mike Beauregard. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post A history of paleontology in China appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGroundhogs are more than just prognosticatorsKin selection, group selection and altruism: a controversy without end?The Vegetarian Plant

Related StoriesGroundhogs are more than just prognosticatorsKin selection, group selection and altruism: a controversy without end?The Vegetarian Plant

Jonathan Nagler: writing good code

Today’s data scientist must know how to write good code. Regardless of whether they are working with a commercial off-the-shelf statistical software package, R, python, or perl, all require the use of good coding practices. Large and complex datasets need lots of manipulation to wrangle them into shape for analytics, statistical estimation often is complex, and presentation of complicated results sometimes requires writing lots of code. To make sure that code is understandable to the author and others, good coding practices are essential.

Many who teach methodology, statistics, and data science, are increasingly teaching their students how to write good computer code. As a practical matter, if a professor requires that students turn in their code for a problem set, that code needs to be well-crafted to be legible to the instructor. But as increasing numbers of our students are writing and distributing their code and software tools to the public, professionally we need to do more to train students how to write good code. Finally, good code is critical for research replication and transparency — if you can’t understand someone’s code, it might be difficult or impossible to be able to reproduce their analysis.

When I first started teaching methods to graduate students, there was little in the methodological literature that I found useful for teaching graduate students good coding practices. But in 1995, my colleague Jonathan Nagler wrote out some great guidance on good methodological practices, in particular guidelines for good coding style. His piece is available online (“Coding Style and Good Computing Practices”), and his advice from 1995 is as relevant today as it was then. I use Jonathan’s guidelines in my graduate teaching.

Over the past few years, as Political Analysis has focused resources on research replication and transparency, it’s become clear that we need to develop better guidance for researchers and authors regarding how to write good code. One of the biggest issues that we run into when we review replication materials that are submitted to the journal is poor documentation and unclear code; and if we can’t figure out how the code works, I’m sure that our readers will have the same problem.

We’ve been thinking of developing some guidelines for documentation of replication materials, and standards for coding practices. As part of that research, I asked Jonathan if he would write an update of his 1995 essay, and for him to reflect some on how things might have evolved in terms of good computing practices since 1995. His thoughts are below, and I encourage readers to also read Jonathan’s original 1995 essay.

* * * * *

Coding style and good computing practices: it is easy to get the style right, harder to get good practice, by Jonathan Nagler, NYUMany years ago I was prompted to write Coding Style and Good Computing Practices, an article laying out guidelines for coding style for political scientists. The article was reprinted in a symposium on replication in PS (September 1995, Vol. 28, No. 3, 488-492). According to Google Scholar, it has rarely been cited, but I’m convinced it has been read quite often because I’ve seem some idiosyncratic suggestions made in it in the code of other political scientists. Though re-reading the article I am reminded how many people have not read it, or just ignored it.

Ladies coding event by Jon Lim. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Ladies coding event by Jon Lim. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Here is a list of basic points reproduced from that article:

Labbooks: essential. Command files: they should be kept. Data-manipulation vs. data-analysis: these should be in distinct files. Keep tasks compartmentalized (‘modularity’). Know what the code is supposed to do before you start. Don’t be too clever. Variable names should mean something. Use parentheses and white-space to make code readable. Documentation: all code should include comments meaningful to others.And I concluded with a list of rules:

Maintain a labbook from the beginning of a project to the end. Code each variable so that it corresponds as closely as possible to a verbal description of the substantive hypothesis the variable will be used to test. Errors in code should be corrected where they occur and the code re-run. Separate tasks related to data-manipulation vs data-analysis into separate files. Each program should perform only one task. Do not try to be as clever as possible when coding. Try to write code that is as simple as possible. Each section of a program should perform only one task. Use a consistent style regarding lower and upper case letters. Use variable names that have substantive meaning. Use variable names that indicate direction where possible. Use appropriate white-space in your programs, and do so in a consistent fashion to make them easy to read. Include comments before each block of code describing the purpose of the code. Include comments for any line of code if the meaning of the line will not be unambiguous to someone other than yourself. Rewrite any code that is not clear. Verify that missing data is handled correctly on any recode or creation of a new variable. After creating each new variable or recoding any variable, produce frequencies or descriptive statistics of the new variable and examine them to be sure that you achieved what you intended. When possible, automate things and avoid placing hard-wired values (those computed ‘by-hand’) in code.Those are still very good rules, I would not change any of them. I would add one, and that is to put comments in any paper citing the piece of code that produced the figures or tables in the paper. In 20 years a lot of things have changed about how we do computing. It has gotten much easier to follow good computing practices. Github has made it easy to share code, maintain revision history, and publish code. And the set of people who seamlessly collaborate by sharing files over Dropbox or one of its competitors probably dwarfs the number of political scientists using Github. But to paraphrase a common computing aphorism (GIGO), sharing or publishing badly written code won’t make it easy for people to replicate or build on your work.

I was motivated to write that article because as I stated then, most political scientists aren’t trained as computer programmers. Nor were most political scientists trained to work in a laboratory. So the article covered both style of code, and computing practice to make sure that an entire research project could be reproduced by someone else. That means keeping track of where you got your data, how it was processed, etc.

Any computer code is a set of instructions that produces results when read by a machine, and we can evaluate the code based on the results it produces. But when we share code we expect it to be read by humans. Two pieces of code be functionally equivalent — they could produce identical results when read by a machine — even though one is easy to read and understand by a human; while the other is pretty much unintelligible to a human. If you expect people to use your code, you need to make the code easy to read. I try to ask every graduate student I am going to work with to read several chapters from Brian W. Kernighan and Rob Pike’s, The Practice of Programming (1999), especially the Preface, Chapters 1, 3, 5, 6, and the Epilogue.

It has turned out to be easier to write clean code than to maintain good computing practices overall that would lead to easy reproducibility of an entire research project. It is fairly easy to post a ‘replication’ dataset, and the code used to produce the figures and tables in a paper. But that doesn’t really tell someone everything they need to know to try to reproduce your work, or extend it to other data. They need to know how your data was generated. And those steps occur in the production of the replication dataset, not in the use of it.

Most research projects in political science pull in data from many sources. And many, many coding decisions are made along the way to a finished product. All of those decisions may be visible in the code; but keeping coherent lab-books is essential for sifting through all the lines of code of any large project. And ‘projects’ rarely stand-alone anymore. Work on one dataset is linked to many projects, often with over-lapping sets of co-authors.

At the beginning of a research project it’s important for everyone to agree where the code is, where the data is, and what the overall structure of the documentation is. That means decisions about whether documentation is grouped by project (which could mean by individual paper), or by dataset. And it means reaching some agreement on whether there is a master document that points to many smaller documents describing individual tasks, or whether the whole project description sits in a single document. None of this is exciting to work out, certainly not as exciting as doing the research. But it is essential. A good goal of doing all this is to make it as easy as possible to make the whole bundle of documentation and code public as soon as it is time to do so. It both saves time when it is time to release documentation, and imposes some good habits and structure along the way.

Heading image: Typing computer screen reflection by Almonroth. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Jonathan Nagler: writing good code appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesReplication redux and Facebook dataGary King: an update on DataverseDon’t blame Sykes-Picot

Related StoriesReplication redux and Facebook dataGary King: an update on DataverseDon’t blame Sykes-Picot

Fighting the threat within

The recent attacks on Charlie Hebdo, the siege in Sydney, and the Canadian parliament attack have heightened fears of the type of home-grown security threats that had been realised earlier in the July 2005 London bombings. Looking to the future, security agencies and governments have warned grimly of battle hardened jihadists returning home from Middle Eastern and North African theatres of war. For better or worse, robust internal security, heightened surveillance, and preventative law enforcement targeting suspect individuals and communities have been presented as unavoidably necessary for democratic states the world over. But in searching for security, these liberal democracies are now confronted with difficult questions about how to provide public safety and state security within the framework of the rule of law. If there are enemies within, how can they be dealt with while still preserving the civil liberties and rights of all citizens? Can the state zero in on a particular segment of the population without actively and illegally discriminating against them? One particularly thorny issue is what to do about those returning from jihadist wars. Can they be stripped of their citizenship and barred from re-entering their old homeland? Is citizenship a privilege to be revoked at will, or does the state have a responsibility to all of its citizens, no matter how unsavoury? Do seemingly exceptional times permit legally exceptional measures?

While the reality of today’s terrorist violence has upped the stakes, these legal dilemmas are not new. Prior to World War I, European states also tussled with the dilemma of what to do with citizens they suspected of disloyal or treasonous intent. One of the central preoccupations of nineteenth century Germany, for example, was what to do with elements of the population viewed as internal enemies of the state, so-called Reichsfeinde. The communities coming under suspicion then might seem surprising today; Catholics, socialists, French, Danes, and Poles. Individuals from these groups who weren’t citizens were simply expelled from the country, but for those who had the rights of a citizen, the situation was far trickier. Germany prided itself on its reputation as a state governed by the rule of law, and the law explicitly forbade capricious measures like expelling citizens. How could a constitutional state find legal ways to put pressure on its internal enemies?

![Otto Fürst von Bismarck by AD.BRAUN & Cie Dornach via Wikimedia Commons [public domain]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1423475817i/13630575._SY540_.jpg) Otto Fürst von Bismarck by AD.BRAUN & Cie Dornach. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Otto Fürst von Bismarck by AD.BRAUN & Cie Dornach. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons To deal with these domestic threats, German authorities had to be far more inventive, using a host of strictly speaking legal but nonetheless punitive measures to harass suspect populations. Irredentists Danes in the North with German citizenship were targeted for economic ruination; French-speaking Germans were shifted out of their jobs in the militarily sensitive railways of Alsace-Lorraine; Protestant German colonists were sent to dilute the Polish complexion of the east; Jesuits were banned from the Catholic Ruhr; and socialists were pushed out of Berlin, Hamburg, and Leipzig into the countryside. New laws were passed and existing laws were reinterpreted to allow for new repressive uses. The custodians of the German Rechtsstaat sought safety not by side-stepping the law, but by passing and enforcing coercive laws that affected broad segments of the population, in the hope that the actual targets of the laws would be amongst the number affected.

Did these rather blunt internal security measures work? No. In fact, all of this was highly counterproductive. The attitude of Germany’s Danes, Poles, and French towards the German state hardened after being targeted by these legal forms of oppression, while both the socialist and Catholic political milieux went from strength to strength as a result of the experience of being suppressed. Frustrated in particular by his lack of success against the socialists, Bismarck even sought to have their citizenship revoked in the hope of forcing a definitive reckoning with those he saw as dangerous revolutionaries. But this didn’t lead to the destruction of German socialism, but to Bismarck’s own political downfall. The German constitutional state, flexible enough to offer its own forms of legally sanctioned persecution, always baulked at attempts to use unlawful or exceptional measures, despite the air of crisis that surrounded them. Even the measures they did take did little except alienate the broader population.

In their willingness to use violence to pursue their political goals, the jihadists of today are unlike the perceived threats of nineteenth-century Germany. Yet the response of constitutional states bears a remarkable resemblance to these earlier measures. No rolling state of exception or martial law has been declared. Instead, new laws are passed and old ones have been retooled to deal with newly arising threats. Now, as then, the constitutional state, governed by law, has found its own ways to apply pressure to its domestic enemies. Bespoke law, some of it good, some of it horrifying, has stretched but has not severed the commitment to legal and constitutional limits. Warts and all, the liberal constitutional state has shown itself capable of mounting its own stiff defence.

Headline image credit: Security fence by cobalt123. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr

The post Fighting the threat within appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAvarice in the late French RenaissanceOn the dark side of devoutnessDon’t blame Sykes-Picot

Related StoriesAvarice in the late French RenaissanceOn the dark side of devoutnessDon’t blame Sykes-Picot

The impossibility of perfect forgeries?

Imagine that Banksy, (or J.S.G. Boggs, or some other artist whose name starts with “B”, and who is known for making fake money) creates a perfectly accurate counterfeit dollar bill – that is, he creates a piece of paper that is indistinguishable from actual dollar bills visually, chemically, and in every other relevant physical way. Imagine, further, that our artist looks at his creation and realizes that he has succeeded in creating a perfect forgery. There doesn’t seem to be anything mysterious about such a scenario at first glance – creating a perfect forgery, and knowing one has done so, although extremely difficult (and legally controversial), seems perfectly possible. But is it?

In order for an object to be a perfect forgery, it seems like two criteria must be met. First of all, the object must be a forgery – that is, the object cannot be a genuine instance of the category in question. In this case, our object, which we shall call X, must not be an actual dollar bill:

1.) X is not a dollar bill.

Second, the object must be perfect (as a forgery) – that is, it can’t be distinguished from actual instances of the category in question. We can express this thought as follows:

2.) We cannot know that X is not a dollar bill.

Now, there is nothing that prevents both (1) and (2) from being simultaneously true of some object X (say, our imagined fake dollar bill). But there is an obstacle that seemingly prevents us from knowing that both (1) and (2) are true – that is, from knowing that X is a perfect forgery.

Imagine that we know that (1) is true, and in addition we know that (2) is true. In other words, the following claims hold:

3.) We know that X is not a dollar bill.

4.) We know that we cannot know that X is not a dollar bill.

Knowledge is factive – in other words, if we know a claim is true, then that claim must, in fact, be true. Applying this to the case at hand, this means that claim (4) entails claim (2). But claim (2) and claim (3) are incompatible with each other: (2) says we cannot know that X isn’t a dollar, while (3) says we know it isn’t. Thus, (3) and (4) can’t both be true, since if they were, then a contradiction would also be true (and contradictions can’t be true).

‘Dollars’ by 401(K), 2012, CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

‘Dollars’ by 401(K), 2012, CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr. Thus, we have proven that, although perfect forgeries might well be possible, we can never know, of a particular object, that it is a perfect forgery. But an important question remains: If this is right, then what, exactly, is going on in the story with which we began? How is it that our imagined artist doesn’t know that he has created a perfect forgery?

In order to answer this question, it will help to flesh out the story a bit more. So, once again imagine that our artist creates the piece of paper that is visually, chemically, and in every other physical way indistinguishable from a real dollar bill. Call this Stage 1. Now, after admiring his work for a while, imagine that the artist then pulls eight genuine, mint-condition dollar bills out of his wallet, throws them on the table, and then places the forgery he created into the pile, shuffling and mixing until he can no longer identify which of the pieces of paper is the one he created, and which are the ones created by the Mint. Let’s call this Stage 2. How do Stage 1 and Stage 2 differ?

At Stage 1 we do not, strictly speaking, have a case of a perfect forgery. Although the piece of paper the artist created is physically indistinguishable from a dollar bill, the artist can nevertheless know it is not a dollar bill because he knows that he created this particular object. In other words, at Stage 1 he can tell that the forgery is a forgery because he knows the history, and in particular the origin, of the object in question.

Stage 2 is different, however. Now the fake is a perfect forgery, since it still isn’t a dollar, but we can’t know that it isn’t a dollar, since we can no longer distinguish it from the genuine dollars in the pile. So in some sense we know that the fake dollar in the pile is a perfect forgery. But we can’t point to any particular piece of paper and know that it, rather than one of the other eight pieces of paper, is the perfect forgery. In other words, in Stage 2 the following is true:

We know there is an object in the pile that is a perfect forgery.But the following, initially similar looking claim, is false:

There is an object in the pile that we know is a perfect forgery.We can sum all this up as follows: We can know that perfect forgeries exist – that is, we can know claims of the form “One of those is a perfect forgery”. But we can’t know, of a particular object, that it is a perfect forgery – that is, we can never know claims of the form “That is a perfect forgery”. And it is this latter sort of claim – that we know, of a particular object, that it is a perfect forgery – that leads to the contradiction.

The post The impossibility of perfect forgeries? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAccusation breeds guiltThe impossible paintingOn the dark side of devoutness

Related StoriesAccusation breeds guiltThe impossible paintingOn the dark side of devoutness

February 7, 2015

Don’t blame Sykes-Picot

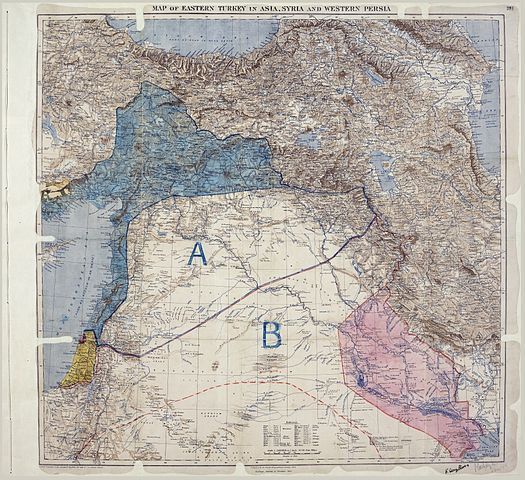

What do Glenn Beck, Bashar al-Assad, the Islamic State, and Noam Chomsky have in common? They all place much of the blame for the current crisis in the Middle East on the so-called “Sykes-Picot Agreement,” a plan for the postwar partition of Ottoman territories drawn up during World War I.

Named after the two diplomats who negotiated the secret deal in 1915-16—Sir Mark Sykes of the British war office and François Georges-Picot, French consul in Beirut—the Sykes-Picot Agreement divided up the Asiatic provinces of the Ottoman Empire into zones of direct and indirect British and French control. It also “internationalized” Jerusalem—a bone thrown to the Russian Empire, a British and French ally, which worried that Orthodox Christians might be put at a disadvantage if the Catholic French had final say about the future of the holy city. Although Russia never officially signed the agreement, it acquiesced to it in return for its allies’ reaffirmation of postwar Russian control over Istanbul and the Turkish Straits and direct Russian control over parts of eastern Anatolia.

“I know I read about [the Sykes-Picot Agreement] years ago when we were at Fox,” Glenn Beck reported in September 2014, “and I put it up on the chalkboard….But it didn’t all fall into place until I learned about ISIS and ISIL…Now it all makes sense to me, and now you’ll be able to figure out what is really going on.”

Bashar al-Assad concurs: “What is taking place in Syria is part of what has been planned for the region for tens of years, as the dream of partition is still haunting the grandchildren of Sykes–Picot.”

So does al-Assad’s sometime enemy, the Islamic State, which wrote in its glossy magazine, Dabiq, “After demolishing the Syrian/Iraqi border set up by the crusaders to divide and disunite the Muslims, and carve up their lands in order to consolidate their control of the region, the mujāhidīn of the Khilāfah delivered yet another blow to nationalism and the Sykes-Picot-inspired borders that define it.”

Even Noam Chomsky got into the act, opining, “I think the Sykes-Picot agreement is falling apart.”

The fact is, however, that it’s way too late for that. By the end of World War I, the Sykes-Picot Agreement was already a dead letter.

“MPK1-426 Sykes Picot Agreement Map signed 8 May 1916.” Photo by Royal Geographical Society (Map), Mark Sykes & François Georges-Picot (Annotations). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

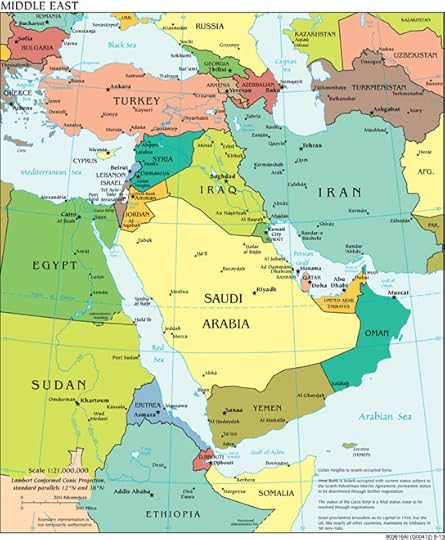

“MPK1-426 Sykes Picot Agreement Map signed 8 May 1916.” Photo by Royal Geographical Society (Map), Mark Sykes & François Georges-Picot (Annotations). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. “‘Political Middle East’ map from the CIA World Factbook Website.” Photo by Central Intelligence Agency. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“‘Political Middle East’ map from the CIA World Factbook Website.” Photo by Central Intelligence Agency. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Compare a map of the contemporary Middle East (right) with the map proposed by the Sykes-Picot Agreement (above). Is any area of the region under direct British, French, or Russian administration? How do the horizontally delineated zones of indirect control and the vertically delineated zones of direct control compare to the crazy quilt map of the Middle East today? Is Jerusalem (and the adjoining region) under international control? Do France and Russia directly control parts of Anatolia, and does Britain directly control parts of Iraq and the Arabian peninsula?

For the most part, the current boundaries in the Levant, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia came about as the result of two factors. The first is the establishment of the mandates system by the League of Nations, which not only allotted Britain and France temporary control over territory in the region, but enabled the two powers to combine or divide territories into proto-states in accordance with their imperial interests. Thus, Britain created Iraq and Trans-Jordan after the war (Israel and Palestine would come even later); France did the same for Lebanon and Syria. Second, Anatolia remained undivided because Turkish nationalists fought a grueling four year anti-imperialist campaign that drove foreigners out of the peninsula.

Why, then, have so many placed the blame for today’s instability on an agreement that was all but ignored once the Great Powers got down to business in Versailles in 1919? Certainly it is not because it was the first of the secret agreements that set the precedent for dividing Ottoman lands among the allies after the war. That honor belongs to the Constantinople Agreement of 1915. Nor was it the last: the Treaty of St. Jeanne de Maurienne, which gave Italy control over territory in western Anatolia, was signed in 1917.

Perhaps the reason people speak of the “Sykes-Picot boundaries” is that it assigns culpability to individuals rather than complicated historical events or faceless apparatchiks meeting behind closed doors. For Middle Easterners, “Sykes-Picot” became code long ago for imperialist arrogance and the illegitimacy of the contemporary state system, whatever the agreement’s actual historical significance. Once the phrase struck roots in the region, it spread globally, particularly after Al-Qaeda made it a focal point of its polemics.

Poor Sykes, poor Georges-Picot. Just as Arthur Balfour has, for more than ninety years, borne responsibility for an eponymous declaration written by others and approved by the British prime minister and cabinet, Sykes and Georges-Picot have become the obligatory villains in narratives that give pride of place to the imperialist perfidy that has frustrated Arab or Islamic unity and is responsible for the multiple failures of the contemporary Middle Eastern state.

Image Credit: “Yemeni Protests 4-Apr-2011 P01.” Photo by Email4mobile. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Don’t blame Sykes-Picot appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesUsing religious repression to preserve nondemocratic ruleAtheism: Above all a moral issueThe food we eat: A Q&A on agricultural and food controversies

Related StoriesUsing religious repression to preserve nondemocratic ruleAtheism: Above all a moral issueThe food we eat: A Q&A on agricultural and food controversies

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers