Oxford University Press's Blog, page 706

January 31, 2015

College Arts Association 2015 Annual Meeting Conference Guide

The Oxford University Press staff is happy that the College Arts Association 2015 Annual Conference (11-14 February 2015) will be held in our backyard: New York City! So we gathered together to discuss what we’re interested in seeing at this year’s conference, as well as some suggestions for those visiting our city.

Alodie Larson, Editorial:

I look forward to CAA. I love having the opportunity to meet authors, see old friends, and get together with the outstanding group of scholars who make up the Editorial Board for Grove Art. The years that New York hosts CAA are low-key for me, as I don’t need to travel.

I recommend heading to MoMA to hold meetings over coffee and snacks in their cafes. If you need a break from the din of the conference and/or architectural inspiration, slip over to Cram and Goodhue’s beautiful St. Thomas Church 5th Avenue for a moment of quiet reflection.

Joy Mizan, Marketing:

This will be my first time attending CAA with OUP. I’m excited to help set up our booth and display our latest books and online products in Art, but I’m really excited to meet our authors, board members, and academics to learn more about their interest in Art. (It’s always great to meet in person after only interacting over email or the phone.)

Need a place to eat? There’s a great food cart called Platters right outside the hotel, so I definitely suggest attendees try it out while in NYC. It opens at 7:00 p.m. though!

Sarah Pirovitz, Editorial:

I’m thrilled to be attending CAA this year as an acquiring editor for monographs and trade titles. I look forward to hearing about interesting new projects and connecting with scholars and friends in the field.

Mohamed Sesay, Marketing:

I’m delighted to attend my first CAA conference with Oxford University Press. This conference will be a great opportunity to meet authors in person, and to get to know some of our Art consumers.

If you’re looking for a great place to eat in New York City I suggest Landmarc in Columbus Circle. The restaurant has great food and it’s right next to Central Park.

Here are just a few of the sessions that caught our eyes:

The Trends in Art Book Publishing, on 10 February at 6:00 p.m. in the New York Public Library, Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, South Court Auditorium (Yes, we work in publishing!)

Original Copies: Art and the Practice of Copying, on 11 February at 9:30 a.m. in the Hilton New York, 2nd Floor, Sutton Parlor South

Building a Multiracial American Past (Association for Critical Race Art History), on 11 February at 12:30 p.m. in the Hilton New York, 2nd Floor, Sutton Parlor Center

Making Sense of Digital Images Workshop, on 11 February at 2:30 p.m.

CAA Convocation and Awards Presentation, including Dave Hickey’s Keynote Address, on 11 February at 5:30 p.m. in the Hilton New York, 3rd Floor, East Ballroom

Chelsea Gallery District Walking Tour, on 12 February at 12:00 p.m.

Presenting a Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts (CAA Committee on Intellectual Property), on 13 February at 12:30 p.m.

New York 1880: Art, Architecture, and the Establishment of a Cultural Capital on 13 February at 2:30 p.m. in the Hilton New York, 2nd Floor, Beekman Parlor

Art Lovers and Literaturewallahs: Communities of Image and Text in South and Southeast Asia (American Council for Southern Asian Art), on 14 February at 9:30 am in the Hilton New York, 3rd Floor, Rendezvous Trianon

The Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, 2nd Edition (Oxford University Press – that’s us!) on 14 February at 12:30 p.m. in the Hilton New York, 2nd Floor, Sutton Parlor Center

Of course, we hope to see you at Oxford University Press booth 1215. We’ll be offering the chance to:

Check out which books we’re featuring.

Browse and buy our new and bestselling titles on display at a 20% conference discount.

Get free trial access to our suite of online products.

Pick up sample copies of our latest art journals.

Enter our raffle for free OUP books.

Meet all of us!

And don’t forget to learn more about the conference on the official website, or follow along on social media with the #CAA2015 hashtag.

Featured Image: Reflection / Kolonihavehus by Tom Fruin and CoreAct @ DUMBO Arts Festival, Brooklyn Bridge Park, NYC by Axel Taferner. CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post College Arts Association 2015 Annual Meeting Conference Guide appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFluorescent proteins and medicineRotten fish and Belfast confettiThe 11 explorers you need to know

Related StoriesFluorescent proteins and medicineRotten fish and Belfast confettiThe 11 explorers you need to know

Essential considerations for leadership in policing (and beyond)

There are problems with defining the term ‘leadership’. Leadership often gets confused with the management function because, generally, managers are expected to exhibit some leadership qualities. In essence, leaders are instruments of change, responsible for laying plans both for the moment and for the medium and long-term futures. Managers are more concerned with executing plans on a daily basis, achieving objectives and producing results.

Top police leaders have a responsibility for deciding, implementing, monitoring, and completing the strategic plans necessary to meet the needs and demands of the public they serve. Their plans are then cascaded down through the police structure to those responsible for implementing them. Local commanders may also create their own plans to meet regional demands. The planner’s job is never finished: there is always a need to adapt and change existing measures to meet fresh circumstances.

Planning is a relatively mechanical process. However, the management of change is notoriously difficult. Some welcome change and the opportunities it brings; others do not because it upsets their equilibrium or places them at some perceived disadvantage. Mechanisms for promoting plans and dealing with concerns need to be put in place. Factual feedback and suggestions for improvement should be welcomed as they can greatly improve end results. When people contribute to plans they are more likely to support them because they have some ownership in them.

Those responsible for implementing top-level and local plans may do so conscientiously but arrangements rarely run smoothly and require the application of initiative and problem solving skills. Sergeants, inspectors, and other team leaders – and even constables acting alone – should be encouraged to help resolve difficulties as they arise. Further, change is ever present and can’t always be driven from the top. It’s important that police leaders and constables at operational and administrative levels should be stimulated to identify and bring about necessary changes – no matter how small – in their own spheres of operation, thus contributing to a vibrant leadership culture.

The application of first-class leadership skills is important: quality is greatly influenced by the styles leaders adopt and the ways in which they nurture individual talent. Leadership may not be the first thing recruits think of when joining the police. Nonetheless, constables are expected to show leadership on a daily basis in a variety of different, often testing situations.

“Leaders are instruments of change, responsible for laying plans both for the moment and for the medium and long-term futures.”

Reflecting on my own career, I was originally exposed to an autocratic, overbearing organisation where rank dominated. However, the force did become much more sophisticated in its outlook as time progressed. As a sergeant, inspector, and chief inspector, my style was a mixture of autocratic and democratic, with a natural leaning towards democratic. Later, in the superintendent rank, I fully embraced the laissez-faire style, making full use of all three approaches. For example, at one time when standards were declining in the workplace I was autocratic in demanding that they should be re-asserted. When desired standards were achieved, I adopted a democratic style to discuss the way forward with my colleagues. When all was going well again, I became laissez-faire, allowing individuals to operate with only a light touch. The option to change style was never lost but the laissez-faire approach produced the best ever results I had enjoyed in the police.

Although I used these three styles, the labels they carry are limiting and do not reveal the whole picture. Real-life approaches are more nuanced and more imaginative than rigidly applying a particular leadership formula. Sometimes more than one style can be used at the same time: it is possible to be autocratic with a person who requires close supervision and laissez-faire with someone who is conscientious and over-performing. Today, leadership style is centred upon diversity, taking into account the unique richness of talent that each individual has to offer.

Individual effort and team work are critical to the fulfillment of police plans. To value and get the best out of officers and support staff, leaders need to do three things. First, they must ensure that there is no place for discrimination of any form in the police service. Discrimination can stunt personal and corporate growth and cause demotivation and even sickness. Second, they should seek to balance the work to be done with each individual’s motivators. Dueling workplace requirements with personal needs is likely to encourage people to willingly give of their best. Motivators vary from person to person although there are many common factors including opportunities for more challenging work and increased responsibility. Finally, leaders must keep individual skills at the highest possible level, including satisfying the needs of people with leadership potential. Formal training is useful but perhaps even more effective is the creation of an on-the-job, incremental coaching programme and mentoring system.

Police leaders need to create plans and persuade those they lead to both adopt them and see them through to a satisfactory conclusion. If plans are to succeed, change must be sensitively managed and leaders at all levels should be encouraged to use their initiative in overcoming implementation problems. Outside of the planning process, those self-same leaders should deal with all manner of problems that beset them on a daily basis so as to create a vibrant leadership culture. Plans are more liable to succeed if officers and support staff feel motivated and maintain the necessary competence to complete tasks.

Headline image: Sir Robert Peel, by Ingy The Wingy. CC-BY-ND-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Essential considerations for leadership in policing (and beyond) appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTransforming the police through scienceJudicial resistance? War crime trials after World War IThe not so thin blue line: policing economic crime

Related StoriesTransforming the police through scienceJudicial resistance? War crime trials after World War IThe not so thin blue line: policing economic crime

January 30, 2015

Judicial resistance? War crime trials after World War I

There was a great change in peace settlements after World War I. Not only were the Central Powers supposed to pay reparations, cede territory, and submit to new rules concerning the citizenship of their former subjects, but they were also required to deliver nationals accused of violations of the laws and customs of war (or violations of the laws of humanity, in the case of the Ottoman Empire) to the Allies to stand trial.

This was the first time in European history that victor powers imposed such a demand following an international war. This was also the first time that regulations specified by the Geneva and Hague Conventions were enforced after a war ended. Previously, states used their own military tribunals to enforce the laws and customs of war (as well as regulations concerning espionage), but they typically granted amnesty for foreigners after a peace treaty was signed.

The Allies intended to create special combined military tribunals to prosecute individuals whose violations had affected persons from multiple countries. They demanded post-war trials for many reasons. Legal representatives to the Paris Peace Conference believed that “might makes right” should not supplant international law; therefore, the rules governing the treatment of civilians and prisoners-of-war must be enforced. They declared the war had created a modern sensibility that demanded legal innovations, such as prosecuting heads of state and holding officers responsible for the actions of subordinates. British and French leaders wanted to mollify domestic feelings of injury as well as propel an interpretation that the war had been a fight for “justice over barbarism,” rather than a colossal blood-letting. They also sought to use trials to exert pressure on post-war governments to pursue territorial and financial objectives.

The German, Ottoman, and Bulgarian governments resisted extradition demands and foreign trials, yet staged their own prosecutions. Each fulfilled a variety of goals by doing so. The Weimar government in Germany was initially forced to sign the Versailles Treaty with its extradition demands, then negotiated to hold its own trials before its Supreme Court in Leipzig because the German military, plus right-wing political parties, refused the extradition of German officers. The Weimar government, led by the Social Democratic party, needed the military’s support to suppress communist revolutions. The Leipzig trials, held 1921-27, only covered a small number of cases, serving to deflect responsibility for the most serious German violations, such as the massacre of approximately 6,500 civilians in Belgium and deportation of civilians to work in Germany. The limited scope of the trials did not purge the German military as the Allies had hoped. Yet the trials presented an opportunity for German prosecutors to take international charges and frame them in German law. Although the Allies were disturbed by the small number of convictions, this was the first time that a European country had agreed to try its own after a major war. General Stenger. Public domain via the French National Archive.

General Stenger. Public domain via the French National Archive.

The Ottoman imperial government first destroyed the archives of the “Special Organization,” a secret group of Turkish nationalists who deported Greeks from the Aegean region in 1914 and planned and executed the massacre of Armenians in 1915. But in late 1918, a new Ottoman imperial government formed a commission to investigate parliamentary deputies and former government ministers from the Turkish nationalist party, the Committee of Union and Progress, which had planned the attacks. It also sought to prosecute Committee members who had been responsible for the Ottoman Empire’s entrance into the war. The government then held a series of military trials of its own accord in 1919 to prosecute actual perpetrators of the massacres, as well as purge the government of Committee members, as these were opponents of the imperial system. It also wanted to quash the British government’s efforts to prosecute Turks with British military tribunals. Yet after the British occupied Istanbul, the nationalist movement under Mustafa Kemal retaliated by arresting British officers. Ultimately, the Kemalists gained control of the country, ended all Turkish military prosecutions for the massacres, and nullified guilty verdicts.

Like the German and Ottoman situations, Bulgaria began a rocky governmental and social transformation after the war. The initial post-war government signed an armistice with the Allies to avoid the occupation of the capital, Sofia. It then passed a law granting amnesty for persons accused of violating the laws and customs of war. However, a new government came to power in 1919, representing a coalition of the Agrarian Union, a pro-peasant party, and right-wing parties. The government arrested former ministers and generals and prosecuted them with special civilian courts in order to purge them; they were blamed for Bulgaria’s entrance into the war. Some were prosecuted because they lead groups of refugees from Macedonia in a terrorist organization, the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization. Suppressing Macedonian terrorism was an important condition for Bulgaria to improve its relationship with its neighbor, the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. In 1923, however, Aleksandar Stambuliski, the leader of the Agrarian Union, was assassinated in a military coup, leading to new problems in Bulgaria.

We could ask a counter-factual question: What if the Allies had managed to hold mixed military tribunals for war-time violations instead of allowing the defeated states to stage their own trials? If an Allied tribunal for Germany was run fairly and political posturing was suppressed, it might have established important legal precedents, such as establishing individual criminal liability for violations of the laws of war and the responsibility of officers and political leaders for ordering violations. On the other hand, guilty verdicts might have given Germany’s nationalist parties new heroes in their quest to overturn the Versailles order.

An Allied tribunal for the Armenian massacres would have established the concept that a sovereign government’s ministers and police apparatus could be held criminally responsible under international law for actions undertaken against their fellow nationals. It might also have created a new historical source about this highly contested episode in Ottoman and Turkish history. Yet it is speculative whether the Allies would have been able to compel the post-war Turkish government to pay reparations to Armenian survivors and return stolen property.

Finally, an Allied tribunal for alleged Bulgarian war criminals, if constructed impartially, might have resolved the intense feelings of recrimination that several of the Balkan nations harbored toward each other after World War I. It might also have helped the Agrarian Union survive against its military and terrorist enemies. However, a trial concentrating only on Bulgarian crimes would not have dealt with crimes committed by Serbian, Greek, and Bulgarian forces and paramilitaries during the Balkan Wars of 1912-13, so a selective tribunal after World War I may not have healed all wounds.

Image Credit: Château de Versailles Hall of Mirrors Ceiling. Photo by Dennis Jarvis. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Judicial resistance? War crime trials after World War I appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTheir blood cries out to GodRotten fish and Belfast confettiIs London the world’s legal capital?

Related StoriesTheir blood cries out to GodRotten fish and Belfast confettiIs London the world’s legal capital?

Fluorescent proteins and medicine

Fluorescent proteins are changing the world. Page through any modern scientific journal and it’s impossible to miss the vibrant images of fluorescent proteins. Bright, colorful photographs not only liven-up scholarly journals, but they also serve as invaluable tools to track HIV, to design chickens that are resistant to bird flu and to confirm the existence of cancerous stem cells. Each day, fluorescent proteins initially extracted from jellyfish and other marine organisms illuminate the inner workings of diseases, increasing our knowledge of them and providing new avenues in the search for their cures.

It is important to realize that these incredibly useful and now very common tools might not have been found if it were not for decades of basic research funded by the US government — research that would probably not be funded by most current funding agencies as the research would be deemed too fundamental in nature and not applied enough to qualify for funding. This fundamental research that formed the basis for all the fluorescent protein based technologies, such as super-resolution microscopy and even optogenetics, was performed by Osamu Shimomura.

Aequorea victoria emitting fluorescent light. Image credit: This photo has been used courtesy of Steven Haddock.

Aequorea victoria emitting fluorescent light. Image credit: This photo has been used courtesy of Steven Haddock.While a research scientist at Princeton University and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, Shimomura spent more than 40 years trying to understand the chemistry responsible for the emission of the green light in A. victoria, and in the process, he caught more than a million jellyfish. Every summer for more than twenty years, Shimomura and his family would make the 3,000-mile drive from Princeton, New Jersey, to the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor laboratory, where they would spend the summer days catching crystal jellyfish from the side of the pier. For 20 well-funded years at Princeton and an additional 20 years at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, Shimomura spent his days, and sometimes his nights, unraveling the mysteries of the jellyfish’s glow.

The crystal jellyfish was the first organism known to use one protein to make light, aequorin, and another to change the color of this light, GFP. There was no precedence in the scientific literature for this type of bioluminescence, and so Shimomura had to break new ground. Additionally it was laborious and painstaking work to isolate even the smallest quantities of GFP. Fortunately Shimomura had both funding and a purist’s fascination with bioluminescence to unlock the secrets of GFP.

Although he was the first to discover GFP and isolate it, he was not interested in the applications of this protein. Doug Prascher, Martin Chalfie and Roger Tsien were responsible for ensuring that the green fluorescent protein from crystal jellyfish, Aequorea victoria, has been used in millions of experiments all around the world. They took the next step, but without Shimomura’s first essential step there may have been no flourescent future.

Featured image: Aequorea victoria by Mnolf (Photo taken in the Monterey Bay Aquarium, CA, USA). CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Fluorescent proteins and medicine appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAre the mysterious cycles of sunspots dangerous for us?Public health in 2014: a year in reviewRotten fish and Belfast confetti

Related StoriesAre the mysterious cycles of sunspots dangerous for us?Public health in 2014: a year in reviewRotten fish and Belfast confetti

Rotten fish and Belfast confetti

Winston Churchill’s Victory broadcast of 13 May 1945, in which he claimed that but for Northern Ireland’s “loyalty and friendship” the British people “should have been confronted with slavery or death,” is perhaps the most emphatic assertion that the Second World War entrenched partition from the southern state and strengthened the political bond between Britain and Northern Ireland.

Two years earlier, however, in private correspondence with US President Roosevelt, Churchill had written disparagingly of the young men of Belfast, who unlike their counterparts in Britain were not subject to conscription, loafing around “with their hands in their pockets,” hindering recruitment and the vital work of the shipyards.

Churchill’s role as a unifying figure, galvanising the war effort through wireless broadcasts and morale-boosting public appearances, is much celebrated in accounts of the British Home Front. The further away from London and the South East of England that one travels, however, the more questions should be asked of this simplistic narrative. Due to Churchill’s actions as Liberal Home Secretary during the 1910 confrontations between miners and police in South Wales, for example, he was far less popular in Wales, and indeed in Scotland, than in England during the war. But in Northern Ireland, too, Churchill was a controversial figure at this time. The roots of this controversy are to be found in events that took place more than a quarter of a century before, in 1912.

Then First Lord of the Admiralty, Churchill was booed on arrival in Belfast that February, before his car was attacked and his effigy brandished by a mob of loyalist demonstrators. Later at Belfast Celtic Football Ground he was cheered by a crowd of five thousand nationalists as he spoke in favour of Home Rule for Ireland. Churchill was not sympathetic to the Irish nationalist cause but believed that Home Rule would strengthen the Empire and the bond between Britain and Ireland; he also saw this alliance as vital to the defence of the United Kingdom.

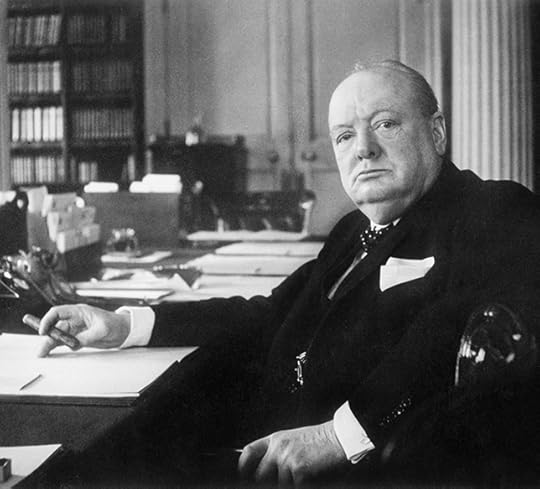

Winston Churchill As Prime Minister 1940-1945 by Cecil Beaton, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Winston Churchill As Prime Minister 1940-1945 by Cecil Beaton, Public Domain via Wikimedia CommonsLoyalists were outraged. Angry dockers hurled rotten fish at Churchill and his wife Clementine as they left the city; historian and novelist Hugh Shearman reported that their car was diverted to avoid thousands of shipyard workers who had lined the route with pockets filled with “Queen’s Island confetti,” local slang for rivet heads. (Harland and Wolff were at this time Belfast’s largest employer, and indeed one of the largest shipbuilding firms in the world; at the time of the Churchills’ visit the Titanic was being fitted out.)

Two years later in March 1914 Churchill made a further speech in Bradford in England, calling for a peaceful solution to the escalating situation in Ulster and arguing that the law in Ireland should be applied equally to nationalists and unionists without preference. Three decades later, this speech was widely reprinted and quoted in several socialist and nationalist publications in Northern Ireland, embarrassing the unionist establishment by highlighting their erstwhile hostility to the most prominent icon of the British war effort. Churchill’s ignominious retreat from Belfast in 1912 was also raised by pamphleteers and politicians who sought to exploit a perceived hypocrisy in the unionist government’s professed support for the British war effort as it sought to suppress dissent within the province. One socialist pamphlet attacked unionists by arguing that “The Party which denied freedom of speech to a member of the British Government before it became the Government of Northern Ireland is not likely to worry overmuch about free speech for its political opponents after it became the Government.”

And in London in 1940 Victor Gollancz’s Left Book Club published a polemic by the Dublin-born republican activist Jim Phelan, startlingly entitled Churchill Can Unite Ireland. In this Phelan expressed hopes that Churchill’s personality itself could effect positive change in Ireland. He saw Churchill as a figure who could challenge what Phelan called “punctilio,” the adherence to deferential attitudes that kept vested interests in control of the British establishment. Phelan identified a cultural shift in Britain following Churchill’s replacement of Chamberlain as Prime Minister, characterised by a move towards plain speaking: he argued that for the first time since the revolutionary year of 1848 “people are saying and writing what they mean.”

Jim Phelan’s ideas in Churchill Can Unite Ireland were often fanciful, but they alert us to the curious patterns of debate that can be found away from more familiar British narratives of the Second World War. Here a proud Irish republican could assert his faith in a British Prime Minister with a questionable record in Ireland as capable of delivering Irish unity.

Despite publically professed loyalty to the British war effort, unionist mistrust of the London government in London endured over the course of the war, partly due to Churchill’s perceived willingness to deal with Irish Taoiseach Éamon de Valera. Phelan’s book concluded with the words: “Liberty does not grow on trees; it must be fought for. Not ‘now or never’. Now.” Eerily these lines presaged the infamous telegram from Churchill to de Valera following the bombing of Pearl Harbor the following year in 1941, which, it is implied, offered Irish unity in return for the southern state’s entry into the war on the side of Allies, and read in part “Now is your chance. Now or never. A Nation once again.”

The post Rotten fish and Belfast confetti appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe death of Sir Winston Churchill, 24 January 1965Misunderstanding World War IIAre the mysterious cycles of sunspots dangerous for us?

Related StoriesThe death of Sir Winston Churchill, 24 January 1965Misunderstanding World War IIAre the mysterious cycles of sunspots dangerous for us?

The 11 explorers you need to know

The list of explorers that changed the way we see the world is vast, so we asked Stewart A. Weaver, author of Exploration: A Very Short Introduction, to highlight some of the most interesting explorers everyone should know more about. The dates provided are the years in which the explorations took place. Let us know if you think anyone else should be added to the list in the comments below.

Pytheas of Massalia, 325 B.C.E.: The first known reporter of the arctic and the midnight sun.

The Greek geographer sailed out of the Bay of Biscay and did not stop until he had rounded the coast of Brittany, crossed the English Channel, and fully circumnavigated the British Isles. Pytheas was an independent adventurer and scientific traveler—the first, for instance, to associate ocean tides with the moon. Whether he made it as far north as Iceland is doubtful, but he somehow knew of the midnight sun and he evidently encountered arctic ice. Even conservative estimates give him credit for some 7,500 miles of ocean travel—an astounding feat for the time and one that justifies Pytheas’s vague reputation as the archetypal maritime explorer.

Abu ’Abdallah Ibn Battuta, 1349-1353: The first known crossing of the Sahara Desert

The greatest of all medieval Muslim travelers was a Moroccan pilgrim who set out for Mecca from his native Tangier in 1325 and did not return until he had logged over 75,000 miles through much of Africa, Arabia, Central Asia, India, and China. He left the first recorded description of a crossing of the Sahara desert, including the only eye-witness reports on such peripheral and then little-known lands as Sudanic West Africa, the Swahili Coast, Asia Minor, and the Malabar coast of India for the better part of a century or more. His journeys included some high adventure and shipwreck worthy of any great explorer.

Zheng He 1405-1433: China’s imperial expeditions

The “Grand Eunuch” and court favorite of the Yongle Emperor of China, Zheng He led seven formidable expeditions through the Indian Ocean. The first voyage alone featured 62 oceangoing junks—each one perhaps ten times the size of anything afloat in Europe at the time—along with a fleet of 225 smaller support vessels, and 27,780 men. With the admiral’s death at sea in 1433, the great fleet was broken up, foreign travel forbidden, and the very name of Zheng He expunged from the records in an effort to erase his example. In 1420 Chinese ships and sailors had no equal in the world. Eighty years later, scarcely a deep-seaworthy ship survived in China.

Christopher Columbus, 1492: God, gold, and glory in the discovery of the Americas

Lured by flawed cartography, Marco Polo’s Travels, the legends of antiquity, and the desire for title and dignity, Columbus weighed anchor on August 3, 1492, in search of a westward route to China and resolved, as he said in his journal, “to write down the whole of this voyage in detail.” From the Canaries, the seasoned navigator picked up the northeast trades that swept his little flotilla directly across the Atlantic in a matter of 33 days. The trans-Atlantic routes he pioneered and the voyages he publicized not only decisively altered European conceptions of global geography; they led almost immediately to the European colonial occupation of the Americas and thus permanently joined together formerly distinct peoples, cultures, and biological ecosystems.

Bartolomeu Dias, 1488: The first European to round the Cape of Good Hope

For six months, Portuguese commander Bartolomeu Dias battled his way south along the coast of Africa against continual storm and adverse currents in search of an ocean passage to India. Finally, unable to do much else, Dias stood out to sea and sailed south-south-west for many days until providentially around 40° south he picked up the prevailing South Atlantic westerlies that carried him eastwards round the southern tip of Africa without his even noticing it. The Indian Ocean was not an enclosed sea; it was accessible from the Atlantic by way of what Dias fittingly called the Cape of Storms and his sponsor, King João of Portugal, named the Cape of Good Hope.

James Cook, 1768-1779: The Christopher Columbus of the Pacific Ocean

James Cook did not in any sense “discover” the Pacific or its island peoples. But he was the first to take full measure of both, to bring order, coherence, and completion to the map of the Pacific, from the Arctic to the Antarctic, and to disclose to the world the broad lineaments of Polynesian cultures. His voyages set a new standard for maritime safety and contributed decisively to the development of astronomy, oceanography, meteorology, and botany and to the founding, in the next century, of ethnology and anthropology. They also did much to integrate Oceania into modern systems of global trade even as they stimulated a fondness for the primitive and the exotic.

“David Livingstone statue, Princes Street Gardens” by kim traynor. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“David Livingstone statue, Princes Street Gardens” by kim traynor. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.David Livingstone, 1856: The first European to transverse sub-Saharan Africa from coast to coast

Born in a one-room tenement in Scotland, this most famous of 19th century explorers had gone to Africa as medical missionary in 1841, but Livingstone’s wanderlust ran ahead of his proselytizing purpose. His sighting of the Zambezi river in June 1851 encouraged a vision of a broad highway of “legitimate commerce” into regions still blighted by the slave trade, and one year later he returned to explore its upper reaches, with the indispensable guidance and cooperation of the indigenous Makololo and other tribes. In May 1856, after years of harrowing travel, he became the first European to traverse sub-Saharan Africa from coast to coast

Nain Singh, 1866-1868: The first cartographer of the Himalayan Mountains

Starting in the winter of 1866, Nain Singh began a two-year trek across the Himalayan Mountains. Known to his British employers as “Pundit No. 1,” Singh surveyed the height and positions of numerous peaks in the Himalayan range, and many of its rivers during his 1,500-mile trek. Recognized by the Royal Geographical Society on his retirement in 1876 as “the man who has added a greater amount of positive knowledge to the map of Asia than any individual of our time,” Singh provided Western explorers the tools to navigate on their own, rather than to rely on local guides.

Roald Amundsen, 1910-1912: The winner of the ‘race to the South Pole’

During his three-year journey through the Northwest Passage beginning in 1903, Roald Amundsen learned to adapt to harsh polar conditions. The Norwegian learned to ski, appreciated the essential role of dogs in polar travel, and adapted to some native Inuit practices. Above all, learning to think small—in terms of ship size and crew—and to travel light , helped him beat his rival explorer, Englishman, Robert F. Scott to the South Pole by over a month. Scott, who considered Amundsen an interloper with a passion for chasing records, died with his four-person crew eleven miles short of their food depot.

Alexander von Humboldt, 1799-1804: Enlightenment scientist and romantic explorer of Latin America

A Prussian geographer, naturalist, and explorer whose five-year expedition through Latin America cast him as a “second Columbus.” Humboldt confirmed the connection of two river systems, the Amazon and the Orinoco, and is most noted for his attempt to climb Chimborazo, then mistakenly thought to be the highest peak in the Americas. A crevasse stopped his team just short of the summit, but at 19,734 feet, they climbed higher than anyone else on record. Sometimes reviled as an example of the explorer as oppressor, one whose travel writing reduced South America to pure nature, drained it of human presence or history, and thus laid it open to exploitation and abuse by European empires, Humboldt has more recently been recovered as an essential inspiration of modern environmentalism.

Leif Eriksson (Son of Eirik the Red), 1001: Northern Europeans’ discovery of America

Bjarni Herjolfsson accidentally triggered the European discovery of America in about 985 when he was blown off course while en route from Norway to Greenland. His adventure stirred an exploratory spirit in his countrymen. Fellow Norseman Leif Eiriksson had no known destination in mind when he set out across the North Atlantic in the year 1001. He sought something new, found it, occupied it, and then returned to tell others. While his journey from Greenland to the “new world” occurred roughly five hundred years before Columbus, it was not immediately celebrated in print and made no lasting cultural impression. Still, Leif’s landfall in “Vinland” led to the first attempt at a permanent European settlement in the Americas at L’Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland.

Featured image: “Hodges, Resolution and Adventure in Matavai Bay” by William Hodges. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The 11 explorers you need to know appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHolocaust consciousness must not blind usThe lost stories of Muslims in the HolocaustA brief history of Data Privacy Law in Asia

Related StoriesHolocaust consciousness must not blind usThe lost stories of Muslims in the HolocaustA brief history of Data Privacy Law in Asia

January 29, 2015

Kin selection, group selection and altruism: a controversy without end?

I recall a dinner conversation at a symposium in Paris that I organized in 2010, where a number of eminent evolutionary biologists, economists and philosophers were present. One of the economists asked the biologists why it was that whenever the topic of “group selection” was brought up, a ferocious argument always seemed to ensue. The biologists pondered the question. Three hours later the conversation was still stuck on group selection, and a ferocious argument was underway.

Group selection refers to the idea that natural selection sometimes acts on whole groups of organisms, favoring some groups over others, leading to the evolution of traits that are group-advantageous. This contrasts with the traditional ‘individualist’ view which holds that Darwinian selection usually occurs at the individual level, favoring some individual organisms over others, and leading to the evolution of traits that benefit individuals themselves. Thus, for example, the polar bear’s white coat is an adaptation that evolved to benefit individual polar bears, not the groups to which they belong.

The debate over group selection has raged for a long time in biology. Darwin himself primarily invoked selection at the individual level, for he was convinced that most features of the plants and animals he studied had evolved to benefit the individual plant or animal. But he did briefly toy with group selection in his discussion of social insect colonies, which often function as highly cohesive units, and also in his discussion of how self-sacrificial (‘altruistic’) behaviours might have evolved in early hominids.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the group selection hypothesis was heavily critiqued by authors such as G.C. Williams, John Maynard Smith, and Richard Dawkins. They argued that group selection was an inherently weak evolutionary mechanism, and not needed to explain the data anyway. Examples of altruism, in which an individual performs an action that is costly to itself but benefits others (e.g. fighting an intruder), are better explained by kin selection, they argued. Kin selection arises because relatives share genes. A gene which causes an individual to behave altruistically towards its relatives will often be favoured by natural selection—since these relatives have a better than random chance of also carrying the gene. This simple piece of logic tallies with the fact that empirically, altruistic behaviours in nature tend to be kin-directed.

Strangely, the group selection controversy seems to re-emerge anew every generation. Most recently, Harvard’s E.O. Wilson, the “father of sociobiology” and a world-expert on ant colonies, has argued that “multi-level selection”—essentially a modern version of group selection—is the best way to understand social evolution. In his earlier work, Wilson was a staunch defender of kin selection, but no longer; he has recently penned sharp critiques of the reigning kin selection orthodoxy, both alone and in a 2010 Nature article co-authored with Martin Nowak and Corina Tarnita. Wilson’s volte-face has led him to clash swords with Richard Dawkins, who says that Wilson is “just wrong” about kin selection and that his most recent book contains “pervasive theoretical errors.” Both parties point to eminent scientists who support their view.

What explains the persistence of the controversy over group and kin selection? Usually in science, one expects to see controversies resolved by the accumulation of empirical data. That is how the “scientific method” is meant to work, and often does. But the group selection controversy does not seem amenable to a straightforward empirical resolution; indeed, it is unclear whether there are any empirical disagreements at all between the opposing parties. Partly for this reason, the controversy has sometimes been dismissed as “semantic,” but this is too quick. There have been semantic disagreements, in particular over what constitutes a “group,” but this is not the whole story. For underlying the debate are deep issues to do with causality, a notoriously problematic concept, and one which quickly lands one in philosophical hot water.

All parties agree that differential group success is common in nature. Dawkins uses the example of red squirrels being outcompeted by grey squirrels. However, as he intuitively notes, this is not a case of genuine group selection, as the success of one group and the decline of another was a side-effect of individual level selection. More generally, there may be a correlation between some group feature and the group’s biological success (or “fitness”); but like any correlation, this need not mean that the former has a direct causal impact on the latter. But how are we to distinguish, even in theory, between cases where the group feature does causally influence the group’s success, so “real” group selection occurs, and cases where the correlation between group feature and group success is “caused from below”? This distinction is crucial; however it cannot even be expressed in terms of the standard formalisms that biologists use to describe the evolutionary process, as these are statistical not causal. The distinction is related to the more general question of how to understand causality in hierarchical systems that has long troubled philosophers of science.

Recently, a number of authors have argued that the opposition between kin and multi-level (or group) selection is misconceived, on the grounds that the two are actually equivalent—a suggestion first broached by W.D. Hamilton as early as 1975. Proponents of this view argue that kin and multi-level selection are simply alternative mathematical frameworks for describing a single evolutionary process, so the choice between them is one of convention not empirical fact. This view has much to recommend it, and offers a potential way out of the Wilson/Dawkins impasse (for it implies that they are both wrong). However, the equivalence in question is a formal equivalence only. A correct expression for evolutionary change can usually be derived using either the kin or multi-level selection frameworks, but it does not follow that they constitute equally good causal descriptions of the evolutionary process.

This suggests that the persistence of the group selection controversy can in part be attributed to the mismatch between the scientific explanations that evolutionary biologists want to give, which are causal, and the formalisms they use to describe evolution, which are usually statistical. To make progress, it is essential to attend carefully to the subtleties of the relation between statistics and causality.

Image Credit: “Selection from Birds and Animals of the United States,” via the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

The post Kin selection, group selection and altruism: a controversy without end? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Vegetarian PlantAre wolves endangered with extinction in Alaska?Are the mysterious cycles of sunspots dangerous for us?

Related StoriesThe Vegetarian PlantAre wolves endangered with extinction in Alaska?Are the mysterious cycles of sunspots dangerous for us?

Sospiri’s Jenny Forsyth on voice and song

Throughout the month, we’ve been examining the myriad aspects of the human voice. But who better to discuss it than a singer herself? We asked Jenny Forsyth, member of the Sospiri choir in Oxford, what it takes to be part of a successful choir.

Which vocal part do you sing in the choir?

I sing soprano – usually first soprano if the parts split, but I’ll sing second if I need to.

For how long have you been singing?

I started singing in the training choir of the Farnham Youth Choir, in Surrey, when I was seven. Then I moved up through the junior choir when I was about 10 years old and then auditioned and moved up to the main performance choir at the age of 12 and stayed with them until I was 18. After this I studied for a Bachelors in Music, then did a Masters degree in Choral Studies (Conducting).

What first made you want to join a choir?

I had recently started having piano lessons and my dad, a musician himself, thought it would be good for my musical education to join a choir. We went to a concert given by the Farnham Youth Choir and after that I was hooked!

What is your favourite piece or song to perform?

That’s a really difficult question – there is so much great music around! I enjoy singing Renaissance music so I might choose Taverner’s Dum Transsiset. I also love Byrd’s Ne Irascaris Domine and Bogoroditse Devo from Rachmaninoff’s Vespers.

I also sing with an ensemble called the Lacock Scholars, and we sing a lot of plainsong chant, a lot of which is just so beautiful. Reading from historical notation – neumes – can give you so much musical information through such simple notation; it’s really exciting!

I’ve recently recorded an album of new commissions for the centenary of World War I with a choir from Oxford called Sospiri, directed by Chris Watson. The disk is called A Multitude of Voices and all the commissions are settings of war poems and texts. The composers were asked to look outside the poetical canon and consider texts by women, neglected poets and writers in languages other than English. I love all the music on the disk and it’s a thrilling feeling to be the first choir ever to sing a work. I really love Standing as I do before God by Cecilia McDowall and Three Songs of Remembrance by David Bednall. Two completely different works but both incredibly moving to perform.

However I think my all-time favourite has to be Las Amarillas by Stephen Hatfield – an arrangement of Mexican playground songs. It’s in Spanish and has some complicated cross rhythms, clapping, and other body percussion. It’s a hard piece to learn but when it comes together it just clicks into place and is one of the most rewarding pieces of music!

Photo by Jenny Forsyth

Photo by Jenny ForsythHow do you keep your voice in peak condition?

These are the five things I find really help me. (Though a busy schedule means the early nights are often a little elusive!)

Keeping hydrated. It is vital to drink enough water to keep your whole system hydrated (ie., the internal hydration of the entire body that keeps the skin, eyes, and all other mucosal tissue healthy), and to make sure the vocal chords themselves are hydrated. When you drink water the water doesn’t actually touch the vocal chords so I find the best way to keep them hydrated is to steam, either over a bowl of hot water or with a purpose-built steam inhaler. The topical, or surface, hydration is the moisture level that keeps the epithelial surface of the vocal folds slippery enough to vibrate. Steaming is incredibly good for a tired voice!

I’m not sure what the science behind this is but I find eating an apple just before I sing makes my voice feel more flexible and resonant.

Hot drinks. A warm tea or coffee helps to relax my voice when it’s feeling a bit tired.

Regular singing lessons. Having regular singing lessons with a teacher who is up to date on research into singing techniques is crucial to keeping your voice in peak condition. Often you won’t notice the development of bad habits, which could potentially be damaging to your voice, but your singing teacher will be able to correct you and keep you in check.

Keeping physically fit and getting early nights. Singing is a really physical activity. When you’ve been working hard in a rehearsal or lesson you can end up feeling physically exhausted. Even though singers usually make singing look easy, there is a lot of work going on behind the scenes with lots of different sets of muscles working incredibly hard to support their sound. It’s essential to keep your body fit and well-rested to allow you to create the music you want to without damaging your voice.

Do you play any other musical instruments?

When I was younger I played the piano, flute and violin but I had to give up piano and flute as I didn’t have enough time to do enough practice to make my lessons worthwhile. I continued playing violin and took up viola in my gap year and then at university studied violin as my first study instrument for my first two years before swapping to voice in my final year.

Do you have a favourite place to perform?

I’ve been fortunate enough to travel all around the world with the Farnham Youth Choir, with tours around Europe and trips to both China and Australia. So, even before I decided to take my singing more seriously, I had had the chance to sing in some of the best venues in the world. It’s hard to choose a favourite as some venues lend themselves better to certain types of repertoire. Anywhere with a nice acoustic where you can hear both what you are singing and what others around you are singing is lovely. It can be very disconcerting to feel as though you’re singing completely by yourself when you know you’re in a choir of 20! I’m currently doing a lot of singing with the Lacock Scholars at Saint Cuthbert’s Church, Earl’s Court, so I think that’s my favourite at the moment. Having said that, I would absolutely love to sing at the building where I work as a music administrator – Westminster Cathedral! It’s got the most glorious acoustics and is absolutely stunning.

What is the most rewarding thing about being in a choir?

There are so many great things about singing in a choir. You get a sense of working as part of a team, which you rarely get to the same extent outside of choral singing. I think this is because your voice is so personal to you can find yourself feeling quite vulnerable. I sometimes think that to sing well you have to take that vulnerability and use it; to really put yourself ‘out there’ to give the music a sense of vitality. You have to really trust your fellow singers. You have to know that when you come in on a loud entry (or a quiet one, for that matter!) that you won’t be left high and dry singing on your own.

What’s the most challenging thing about singing in a choir?

I think this is similar to the things that are rewarding about being part of a choir. That sense of vulnerability can be unnerving and can sow seeds of doubt in your mind. “Do I sound ok? Is the audience enjoying the performance? Was that what the conductor wanted?” But you have to put some of these thoughts out of your mind and focus on the job in hand. If you’ve been rehearsing the repertoire for a long time you can sometimes find your mind wandering, and then you’re singing on autopilot. So it can be a challenge to keep trying to find new and interesting things in the music itself.

Also, personality differences between members of the choir or singers and conductors can cause friction. It’s important to strike the right balance so that everyone’s time is used effectively. The dynamic between a conductor and their choir is important in creating a finely tuned machine, and it is different with each conductor and each choir. Sometimes in a small ensemble a “Choirocracy” can work with the singers being able to give opinions but it can make rehearsals tedious and in a choral society of over a hundred singers it would be a nightmare.

Do you have any advice for someone thinking about joining a choir?

Do it! I think singing in a choir as I grew up really helped my confidence; I used to be very shy but the responsibility my youth choir gave me really brought me out of myself. You get a great feeling of achievement when singing in a choir. I don’t think that changes whether you’re an amateur singing for fun or in a church choir once a week or whether you’re a professional doing it to make a living. I’ve recently spent time working with an “Office Choir”. All of the members work in the same building for large banking corporation, and they meet up once a week for a rehearsal and perform a couple of concerts a year. It’s great because people who wouldn’t usually talk to each other are engaging over a common interest. So it doesn’t matter whether you’re a CEO, secretary, manager, or an intern; you’re all in the same boat when learning a new piece of music! They all say the same thing: they look forward to Wednesdays now because of their lunchtime rehearsals, and they find themselves feeling a lot more invigorated when they return to their desks afterwards.

Lastly, singing in a choir is a great way to make new friends. Some of my closest friends are people I met at choir aged 7!

Header image credit: St John’s College Chapel by Ed Webster, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr

The post Sospiri’s Jenny Forsyth on voice and song appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe quintessential human instrumentThe myth-eaten corpse of Robert BurnsMonthly gleanings for January 2015

Related StoriesThe quintessential human instrumentThe myth-eaten corpse of Robert BurnsMonthly gleanings for January 2015

Are the mysterious cycles of sunspots dangerous for us?

Galileo and some of his contemporaries left careful records of their telescopic observations of sunspots – dark patches on the surface of the sun, the largest of which can be larger than the whole earth. Then in 1844 a German apothecary reported the unexpected discovery that the number of sunspots seen on the sun waxes and wanes with a period of about 11 years.

Initially nobody considered sunspots as anything more than an odd curiosity. However, by the end of the nineteenth century, scientists started gathering more and more data that sunspots affect us in strange ways that seemed to defy all known laws of physics. In 1859 Richard Carrington, while watching a sunspot, accidentally saw a powerful explosion above it, which was followed a few hours later by a geomagnetic storm – a sudden change in the earth’s magnetic field. Such explosions – known as solar flares – occur more often around the peak of the sunspot cycle when there are many sunspots. One of the benign effects of a large flare is the beautiful aurora seen around the earth’s poles. However, flares can have other disastrous consequences. A large flare in 1989 caused a major electrical blackout in Quebec affecting six million people.

Interestingly, Carrington’s flare of 1859, the first flare observed by any human being, has remained the most powerful flare so far observed by anybody. It is estimated that this flare was three times as powerful as the 1989 flare that caused the Quebec blackout. The world was technologically a much less developed place in 1859. If a flare of the same strength as Carrington’s 1859 flare unleashes its full fury on the earth today, it will simply cause havoc – disrupting electrical networks, radio transmission, high-altitude air flights and satellites, various communication channels – with damages running into many billions of dollars.

There are two natural cycles – the day-night cycle and the cycle of seasons – around which many human activities are organized. As our society becomes technologically more advanced, the 11-year cycle of sunspots is emerging as the third most important cycle affecting our lives, although we have been aware of its existence for less than two centuries. We have more solar disturbances when this cycle is at its peak. For about a century after its discovery, the 11-year sunspot cycle was a complete mystery to scientists. Nobody had any clue as to why the sun has spots and why spots have this cycle of 11 years.

A first breakthrough came in 1908 when Hale found that sunspots are regions of strong magnetic field – about 5000 times stronger than the magnetic field around the earth’s magnetic poles. Incidentally, this was the first discovery of a magnetic field in an astronomical object and was eventually to revolutionize astronomy, with subsequent discoveries that nearly all astronomical objects have magnetic fields. Hale’s discovery also made it clear that the 11-year sunspot cycle is the sun’s magnetic cycle.

Sunspot 1-20-11, by Jason Major. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Sunspot 1-20-11, by Jason Major. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.Matter inside the sun exists in the plasma state – often called the fourth state of matter – in which electrons break out of atoms. Major developments in plasma physics within the last few decades at last enabled us to systematically address the questions of why sunspots exist and what causes their 11-year cycle. In 1955 Eugene Parker theoretically proposed a plasma process known as the dynamo process capable of generating magnetic fields within astronomical objects. Parker also came up with the first theoretical model of the 11-year cycle. It is only within the last 10 years or so that it has been possible to build sufficiently realistic and detailed theoretical dynamo models of the 11-year sunspot cycle.

Until about half a century ago, scientists believed that our solar system basically consisted of empty space around the sun through which planets were moving. The sun is surrounded by a million-degree hot corona – much hotter than the sun’s surface with a temperature of ‘only’ about 6000 K. Eugene Parker, in another of his seminal papers in 1958, showed that this corona will drive a wind of hot plasma from the sun – the solar wind – to blow through the entire solar system. Since the earth is immersed in this solar wind – and not surrounded by empty space as suspected earlier – the sun can affect the earth in complicated ways. Magnetic fields created by the dynamo process inside the sun can float up above the sun’s surface, producing beautiful magnetic arcades. By applying the basic principles of plasma physics, scientists have figured out that violent explosions can occur within these arcades, hurling huge chunks of plasma from the sun that can be carried to the earth by the solar wind.

The 11-year sunspot cycle is only approximately cyclic. Some cycles are stronger and some are weaker. Some are slightly longer than 11 years and some are shorter. During the seventeenth century, several sunspot cycles went missing and sunspots were not seen for about 70 years. There is evidence that Europe went through an unusually cold spell during this epoch. Was this a coincidence or did the missing sunspots have something to do with the cold climate? There is increasing evidence that sunspots affect the earth’s climate, though we do not yet understand how this happens.

Can we predict the strength of a sunspot cycle before its onset? The sunspot minimum around 2006–2009 was the first sunspot minimum when sufficiently sophisticated theoretical dynamo models of the sunspot cycle existed and whether these models could predict the upcoming cycle correctly became a challenge for these young theoretical models. We are now at the peak of the present sunspot cycle and its strength agrees remarkably with what my students and I predicted in 2007 from our dynamo model. This is the first such successful prediction from a theoretical model in the history of our subject. But is it merely a lucky accident that our prediction has been successful this time? If our methodology is used to predict more sunspot cycles in the future, will this success be repeated?

Headline image credit: A spectacular coronal mass ejection, by Steve Jurvetson. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Are the mysterious cycles of sunspots dangerous for us? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCelebrating Women in STEMOf black holes, naked singularities, and quantum gravityStardust making homes in space

Related StoriesCelebrating Women in STEMOf black holes, naked singularities, and quantum gravityStardust making homes in space

January 28, 2015

Monthly gleanings for January 2015

I am pleased to report that A Happy New Year is moving along its warlike path at the predicted speed of one day in twenty-four hours and that it is already the end of January. Spring will come before you can say Jack Robinson, as Kipling’s bicolored python would put it, and soon there will be snowdrops to glean. Etymology and spelling are the topics today. Some other questions will be answered in February.

Etymology

Sod, seethe, suds

Our correspondent Paul Nance is not satisfied with the idea that sod is related to seethe because the senses don’t match; he also wonders where suds in the triad seethe-sod-suds comes in. As concerns his doubts about sod and seethe, he is in good company. Yet Skeat was probably right and the two words seem to be related. We should first note that sodden, the petrified past participle of seethe, contains the syllable sod. The form of some importance is Dutch zode “sod,” “boiling,” and “heap, a lot,” the latter usually occurring in the forms zooi or zo. It is not immediately clear whether all of them are related and with how many words we are dealing (one, two, or three).

I think the best clue to the sod – seethe question is provided by Engl. suds (the singular sud also exists, but its meaning can be left out of the present discussion). English has a regional verb suddle “to sully,” a congener of German sudeln “to daub; sully; do dirty work,” often translated rather misleadingly as “to botch.” Sudeln is believed to have arisen as the result of the confusion of two different roots: one meant “cook” (compare “boil,” above); the other, which meant “sap, moisture,” referred to small bodies of water (pools, puddles, wells, and so forth) and is present in many words of the Indo-European languages, Old English among them. But it is not the ancient history of sudeln that matters. Engl. suddle looks like a borrowing from Dutch or Low German. The same is true of Standard German sudeln, which does not antedate the 15th century, and of Engl. suds, which goes back to the fifteen-hundreds. They emerged too late to be classified with native words. Finally, the same holds for sod, another fifteenth-century intruder, and here comes the main point: sod is almost certainly allied to suds and suds is almost certainly allied to seethe. By the law of transitivity, sod is also allied to this verb. Mr. Lance writes: “In Upstate New York, sod is only occasionally sodden.” But the semantic history of the entire group (sod, suds, sudeln, and suddle) should be looked for in the Low Countries.

Suds are good for babies and etymology.

Suds are good for babies and etymology.House and hood

Even though house might refer to “covering,” while hood, a cognate of hat, certainly does so, they are not related. The ancient vowel of hood was long o (as in Engl. ore, without the r glider after o), while house, from hus, had long u (as in Engl. too), and no bridge connects them.

Engl. house and German Haus

Why do the cognates Engl. brother and German Bruder (to cite one typical example) have only br- in common, while house and Haus sound alike? House and Haus owe their similarity to good luck. It was the so-called German Consonant Shift that drove a wedge between German and the other Germanic languages. Engl. tide and German Zeit “time” are cognates, but the new consonants in Zeit destroyed the similarity. The consonants s and h stayed intact in German, and the vowel (long u) changed the same way in both German and English; hence house and Haus. However, the vowel shift, great or not so great, had partly unpredictable results; compare Dutch huis. The vowel in bread has undergone many changes since the Old English period, and it is hard to believe that both o in German Brot and ea, pronounced as short e, in Engl. bread go back to the same diphthong au. I have known a student who tried to translate an English text into Russian with the help of a German dictionary and, miraculously, had some success. Foreign languages are tough. One’s mother tongue may also look foreign. Thus, ea in bread, as opposed to e in bred, does not increase the amount of happiness in English spellers, and the horror of lead/led is known to many of us.

Latin antiquus

Thomas Lambdin, Professor in Harvard Department of Near Eastern Studies, once suggested that the Latin adjective antiquus “old, ancient” was a borrowing of Aramaic attiq “old.” One of his former students asked me what I can say about this conjecture. I have known for a long time that scholars’ etymologies of English words depend very strongly on their professional orientation. Those linguists who specialize in Old Norse point to possible Scandinavian etymons of English words, while Romance scholars find equally plausible Old French roots. (I am not speaking of the monomaniacs who trace all words of English, and not only of English, to Hebrew, Irish, Slavic, and so forth: those are simply crazy.) Similar things happen in some other areas. Modern linguistics is strongly influenced by the concepts of English phonetics and syntax, because the Chomskyan revolution, before spreading to the rest of the world, took place in the United States and its creator was a native speaker of English. Someone noted that, if N. S. Trubetzkoy were not a native speaker of Russian, some of the central ideas developed in his epoch-making book The Bases of Phonology (Grundzüge der Phonologie) may not have occurred to him.

Professor Lambdin is an expert in Semitic linguistics and, naturally, receives impulses from the material he knows best. I happen to be well-acquainted with his books and even reviewed the etymologies offered in his untraditional manual of Gothic. It is true that that the etymology of antiquus entails several difficulties, but, in my opinion, suggesting that that adjective came from Aramaic is hard to justify. As usual, the closeness of forms is not a sufficient argument. We would like to know why such a basic concept had to be taken over from a foreign language, under what circumstances the borrowing took place, and whether it filled a lacuna in Latin or superseded a native synonym. In the absence of additional arguments I would stay away from such a bold hypothesis.

Dwell and its Latvian parallels

I read the comment on the subject indicated in the title of this section with great interest. Such parallels are of utmost importance. They prove nothing but add credence to some of our conjectures. If a certain semantic shift happened in one language, it may, theoretically speaking, have happen in another. In etymology, high probability and verisimilitude are often the only criteria of truth. That is why Carl Darling Buck’s dictionary of synonyms in the Indo-European languages is so useful.

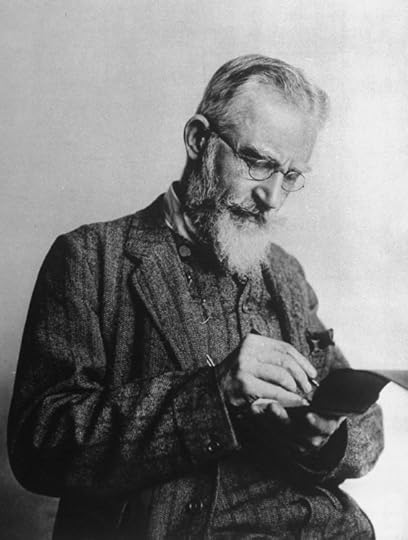

George Bernard Shaw. A glowing example of a man who not only advocated Spelling Reform but also supported it financially.

George Bernard Shaw. A glowing example of a man who not only advocated Spelling Reform but also supported it financially.Spelling and spelling reform

Spelling: whose cup of tea?

One of our correspondents wonders why Modern English spelling is so irrational. It would take a book to answer this question in detail, but the main reasons are two.

After the Norman Conquest of 1066 French and French-educated scribes imposed their habits on English spelling, and the medieval norm has more or less stayed intact to this day.

The second reason is the loyalty of English to foreign spelling. The Spanish don’t mind writing futbol, while English speakers live with monsters like committee, though one m and one t would have been quite enough. Nor do we need s ugar, ch agrin, and sh rine, to say nothing of fuchsia, despite its origin in a proper name.

Thus, the chaos most of us bemoan stems from reverence for tradition. Shureli, a tru skolar wud be imensli shagrind if he were made to put a spoon of shugar in his cup of tee. The tee would taste bitter and the world wud kolaps, wudnt it?

News about spelling reform

I am afraid to sound too optimistic, but it may be that the Spelling Society is making progress, that is, it seems to have feasible plans for effecting the reform and not only ideas about how to spell the words of Modern English. English children take up to two years longer to master basic words than those of other countries (the torture imposed on dyslexics and foreigners should not be forgotten either, for aren’t we all against torture?). The sound system of English is such that we’ll never reach the elegance of Finnish spelling, but something can and should be done. For that purpose, the institution of INTERNATIONAL ENGLISH SPELLING CONGRESS has been proposed. Everyone is welcome to join it. The Expert Committee will be appointed by the delegates who will make the final decision on the alternative scheme. The main virtue of the proposal is that it seeks to engage as many people in the movement as possible. Some publishers of visible journals are already showing an interest in the cause. The public should be informed that the preservation of the status quo has serious negative economic consequences. It is no longer a virtue to smoke. Perhaps the Spelling Congress will be able to explain to the world that retaining a medieval norm in spelling (arguably the most complicated in the world) is not a virtue either. Mr. Stephen Linstead, the Chairman of the Society, has spoken on the BBC and was mocked by many for offering to tamper with a thing of beauty. This is a good sign: no success without public outrage before a novelty is accepted. A report of these events has also been published by the Chicago Tribune.

Image credits: (1) A baby in a bathtub with soap foam. © artefy via iStock. (2) George Bernard Shaw, 1914. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Monthly gleanings for January 2015 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMonthly gleanings for December 2014, Part 2Our habitat: houseOur habitat: dwelling

Related StoriesMonthly gleanings for December 2014, Part 2Our habitat: houseOur habitat: dwelling

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers