Oxford University Press's Blog, page 708

January 25, 2015

Have we become what we hate?

In 1971, William Irvin Thompson, a professor at York University in Toronto, wrote an op-ed in the New York Times entitled, “We Become What We Hate,” describing the way in which “thoughts can become inverted when they are reflected in actions.”

He cited several scientific, sociocultural, economic, and political situations where the maxim appeared to be true. The physician who believed he was inventing a pill to help women become pregnant had actually invented the oral contraceptive. Germany and Japan, having lost World War II, had become peaceful consumer societies. The People’s Republic of China had become, at least back in 1971, a puritanical nation.

Today, many of the values that we, as a nation, profess — protection of civil rights and human rights, assistance for the needy, support for international cooperation, and promotion of peace — have become inverted in our actions. As a nation, we say one thing, but often do the opposite.

As a nation, we profess protection of civil rights. But our criminal justice system and our systems for federal, state, and local elections discriminate against people of color and other minorities.

As a nation, we profess protection of human rights. But we have imprisoned “enemy combatants” without charges, stripped them of their rights as prisoners of war, and tortured many of them in violation of the Geneva Conventions.

As a nation, we profess adherence to the late Senator Hubert H. Humphrey’s dictum that the true measure of a government is how it cares for the young, the old, the sick, and the needy. But we set the minimum wage at a level at which working people cannot survive. We inadequately fund human services for those who need them most. And, even after implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, we continue to be the only industrialized country that does not ensure health care for all its citizens.

As a nation, we profess support for international cooperation. But we fail to sign treaties to ban antipersonnel landmines and prevent the proliferation of nuclear weapons. And we, as a nation, contribute much less than our fair share of foreign assistance to low-income countries.

As a nation, we profess commitment to world peace. But we lead all other countries, by far, in both arms sales and military expenditures.

In many ways, we, as a nation, have become what we hate.

Image Credit: Dispersed, Occupy Oakland Move In Day. Photo by Glenn Halog. CC by NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Have we become what we hate? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWorking in the intensive care unit: an interview with Dr. Robert StevensFour reasons for ISIS’s successImmoral philosophy

Related StoriesWorking in the intensive care unit: an interview with Dr. Robert StevensFour reasons for ISIS’s successImmoral philosophy

Four reasons for ISIS’s success

The editors of Oxford Islamic Studies Online asked several experts the following question:

The world has watched as ISIS (ISIL, the “Islamic State”) has moved from being a small but extreme section of the Syrian opposition to a powerful organization in control of a large swath of Iraq and Syria. Even President Obama recently admitted that the US was surprised by the success of ISIS in that region. Why have they been so successful, and why now?

Political Scientist Robert A. Pape and undergraduate research associate Sarah Morell, both from the University of Chicago, share their thoughts.

ISIS has been successful for four primary reasons. First, the group has tapped into the marginalization of the Sunni population in Iraq to gain territory and local support. Second, ISIS fighters are battle-hardened strategists fighting against an unmotivated Iraqi army. Third, the group exploits natural resources to fund their operations. And fourth, ISIS has utilized a brilliant social media strategy to recruit fighters and increase their international recognition. One of the important aspects cutting across these four elements is the unification of anti-American populations across Iraq and Syria — remnants of the Saddam regime, Iraqi civilians driven to militant behavior during the US occupation, transnational jihadists, and the tribes who were hung out to dry following the withdrawal of US forces in 2011.

The Sunni population’s hatred of the Shia-dominated government in Baghdad has allowed ISIS to quickly overtake huge swaths of Iraqi Sunni territory. The Iraq parliamentary elections in 2010 were a critical moment in this story. The Iraqiyya coalition, led by Ayad Allawi, won support of the Sunni population to win the plurality of seats in Iraq’s parliament. Maliki’s party came second by a slim two-seat margin. Despite Allawi’s electoral victory, Maliki and his Shia coalition — backed by the United States — succeeded in forming a government with Maliki as Prime Minister.

Inside of the Baghdad Convention Center, where the Council of Representatives of Iraq meets. By James (Jim) Gordon. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Inside of the Baghdad Convention Center, where the Council of Representatives of Iraq meets. By James (Jim) Gordon. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. In the months following the election, Maliki targeted Sunni leaders in an effort to consolidate Shia domination of Baghdad. Many of these were the same Sunni leaders successfully mobilized by US forces during the occupation — in an operation that became known as the Anbar Awakening — to cripple al-Qa’ida in Iraq strongholds within the Sunni population. When the US withdrew, they directed the aid to the Maliki government with the expectation that Maliki would distribute it fairly. Instead, the day after the US forces withdrew in December 2011, Iraq’s Judicial Council issued an arrest warrant for Iraqi Vice President Hashimi, a key Sunni leader. Arrests of Sunni leaders and their staffs continued, sparking widespread Sunni protests in Anbar province. When ISIS — a Sunni extremist group — rolled into Iraq, many in the Sunni population cooperated, viewing the group as the lesser of two evils.

The second element in the ISIS success story is their military strategy. Their leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, spent four years as a prisoner in the Bucca Camp before assuming control of AQI (ISIS’s predecessor) in 2010. He seized upon the opportunity of the Syrian civil war to fuel a resurgence of the group. As a result, today’s ISIS militants are battle-hardened through their Syrian experience fighting moderate rebels. The Washington Post has described Baghdadi as “a shrewd strategist, a prolific fundraiser, and a ruthless killer.”

In Iraq, ISIS has adopted “an operational form that allows decentralized commanders to use their experienced fighters against the weakest points of its foes,” writes Robert Farley in The National Interest. “At the same time, the center retains enough operational control to conduct medium-to-long term planning on how to allocate forces, logistics, and reinforcements.” Their strategy — hitting their adversaries at their weakest points while avoiding fights they cannot win — has created a narrative of momentum that increases the group’s morale and prestige.

ISIS has also carved out a territory in Iraq that Shia and Kurdish forces will not fight and die to retake, an argument articulated by Kenneth Pollack at Brookings. ISIS has not tried to take Baghdad because they know they would lose; Shia forces would be motivated to expend blood and treasure to defeat ISIS on their home turf. Some experts believe the Kurds, likewise, are unlikely to commit forces to retake Sunni territory. This mentality also plays into the catastrophic performance of the Iraqi Security Forces at Mosul, forces composed disproportionately of Kurds and Sunni Arabs; when confronted with Sunni militants, these soldiers “were never going to fight to the death for Maliki and against Sunni militants looking to stop him,” writes Pollack.

Third, ISIS has also been able to seize key natural resources in Syria to fund their operations, probably making them one of the wealthiest terror groups in history. ISIS is in control of 60% of Syria’s oil assets, including the Al Omar, Tanak, and Shadadi oil fields. According to the US Treasury, the group’s oil sales are pulling in about $1 million a day. This enables ISIS to increasingly become “a hybrid organization, on the model of Hezbollah,” writes Steve Coll in The New Yorker — “part terrorist network, part guerrilla army, part proto-state.”

Finally, ISIS has developed a sophisticated social media campaign to “recruit, radicalize, and raise funds,” according to J. M. Berger in The Atlantic. The piece details ISIS’s Arabic-language Twitter app called The Dawn of Glad Tidings, advertised as a way to keep up on the latest news about the group. On the day ISIS marched into Mosul, the app sent almost 40,000 tweets. The group has displayed a lighter side to the militants, such as videos showing young children breaking their Ramadan fast with ISIS fighters. These strategies “project strength and promote engagement online” while also romanticizing their fight, attracting new recruits from around the world and inspiring lone wolf attacks.

Since June 2014, the United Sates has pursued a policy of offshore balancing — over-the-horizon air and naval power, Special Forces, and empowerment of local allies — to contain and undermine ISIS. The crucial local groups are the Sunni tribes. These leaders were responsible for the near-collapse of AQI during the Anbar Awakening, and could well be able to defeat ISIS in the future.

This is part two of a series of articles discussing ISIS. Part one is by Hanin Ghaddar, Lebanese journalist and editor. Part two is by Shadi Hamid, fellow at the Brookings Institution. Part three is by Charles Kurzman, Professor of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Headline image credit: Coalition airstrike on ISIL position in Kobane on 22 October 2014. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Four reasons for ISIS’s success appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesISIS’s unpredictable revolutionIdeology and a conducive political environmentISIS is an outcome of a much bigger problem

Related StoriesISIS’s unpredictable revolutionIdeology and a conducive political environmentISIS is an outcome of a much bigger problem

The myth-eaten corpse of Robert Burns

‘Oh, that this too, too solid flesh would melt,’ so wrote the other bard, Shakespeare.

Scotland’s bard, Robert Burns, has had a surfeit of biographical attention: upwards of three hundred biographical treatments, and as if many of these were not fanciful enough hundreds of novels, short stories, theatrical, television, and film treatments that often strain well beyond credulity.

Burns has been pursued beyond (or properly in) the grave in even more extreme ways. His remains have been disinterred twice, the second time so that his skull might be examined for the purposes of phrenology. In death he has been bothered again very recently in the run up to Scotland’s referendum in October 2014. Would Burns have been a ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ voter, a Nationalist or a Unionist, was often posed and answered across media outlets.

This de-historicised Burns, someone who never actually had any kind of political vote in life, who had no access to nationalist, or indeed, unionist ideology, in the modern senses is nothing new. During World War I, the minute book of the Dumfries Volunteer Militia, in which Burns had enlisted in 1795 in the face of threatened French invasion, was rediscovered. It was published in 1919 by William Will of the London Burns Club with a rather emotional introduction claiming that the minute-book’s records showing Burns’s impeccable conduct as a militiaman was proof of the poet’s sound British patriotism and how he might be compared to the many brave British soldiers who had just taken on the Kaiser. In response, those who had been recently constructing a pacifist Burns spluttered with indignation. Wasn’t the Scottish Bard the man who had written ‘Why Shouldna Poor Folk Mowe [make love]’ during the 1790s:

When Princes and Prelates and het-headed zealots

All Europe hae set in a lowe [noisy turmoil]

The poor man lies down, nor envies a crown,

And comforts himself with a mowe.

Portrait of Robert Burns, Ayr, Scotland. Library of Congress.

Portrait of Robert Burns, Ayr, Scotland. Library of Congress. This is an increasingly obscene song, an anti-war text saying, ‘a plague on all your houses’ (to paraphrase the other bard again): the poor should choose love, and not war – the latter being the result of much more shameful shenanigans by their supposed lords and masters.

Ironically enough in ‘To A Louse’, Burns wrote:

O wad some Pow’r the giftie gie us

To see oursels as others see us!

It wad frae monie a blunder free us

An’ foolish notion

The problem is that Burns would be dizzy with the multifarious contradictoriness of it all if he could truly emerge from the grave and attempt to see himself as others have seen him. Ultimately, what we have with Burns is the man who may or may not have been Scotland’s greatest poet, but who is certainly Scotland’s greatest song-writer (with the production of twice as many songs as poems) — the nearest Scotland has, a bit cheesy though the comparison is, to Lennon and McCartney. These songs and poems express indeed many different ideas, moods, emotions, and characters. They sympathise with radically different viewpoints (for instance, Burns can write empathetically on occasion about both Mary Queen of Scots (Catholic Stuart tyrant) and the Covenanters (Calvinist fanatics, according to their respective detractors)). Burns’s work is both his living achievement and the real remains over which we ought to pore. In the end there is no real Burns, but instead a fictional one and the important fictions are of his making.

Image Credit: Scottish Highlands by Gustave Doré (1875). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The myth-eaten corpse of Robert Burns appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe quintessential human instrumentClues, code-breaking, and cruciverbalists: the language of crosswordsThe death of Sir Winston Churchill, 24 January 1965

Related StoriesThe quintessential human instrumentClues, code-breaking, and cruciverbalists: the language of crosswordsThe death of Sir Winston Churchill, 24 January 1965

Immoral philosophy

I call myself a moral philosopher. However, I sometimes worry that I might actually be an immoral philosopher. I worry that there might be something morally wrong with making the arguments I make. Let me explain.

When it comes to preventing poverty related deaths, it is almost universally agreed that Peter Singer is one of the good guys. His landmark 1971 article, “Famine, Affluence and Morality” (FAM), not only launched a rich new area of philosophical discussion, but also led to millions in donations to famine relief. In the month after Singer restated the argument from FAM in a piece in the New York Times, UNICEF and OXFAM claimed to have received about $660, 000 more than they usually took in from the phone numbers given in the piece. His organisation, “The Life You Can Save”, used to keep a running estimate of total donations generated. When I last checked the website on 13th February 2012, this figure stood at $62, 741, 848.

Singer argues that the typical person living in an affluent country is morally required to give most of his or her money away to prevent poverty related deaths. To fail to give as much as you can to charities that save children dying of poverty is every bit as bad as walking past a child drowning in a pond because you don’t want to ruin your new shoes. Singer argues that any difference between the child in the pond and the child dying of poverty is morally irrelevant, so failure to help must be morally equivalent. For an approachable version of his argument see Peter Unger, who developed and refined Singer’s arguments in his 1996 book, Living High and Letting Die.

I’ve argued that Singer and Unger are wrong: failing to donate to charity is not equivalent to walking past a drowning child. Morality does – and must – pay attention to features such as distance, personal connection and how many other people are in a position to help. I defend what seems to me to be the commonsense position that while most people are required to give much more than they currently do to charities such as Oxfam, they are not required to give the extreme proportions suggested by Singer and Unger.

Saving lives, by Oxfam East Africa, CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Saving lives, by Oxfam East Africa, CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons So, Singer and Unger are the good guys when it comes to debates on poverty-related death. I’m arguing that Singer and Unger are wrong. I’m arguing against the good guys. Does that make me one of the bad guys? It is true that my own position is that most people are required to give more than they do. But isn’t there still something morally dubious about arguing for weaker moral requirements to save lives? Singer and Unger’s position is clear and easy to understand. It offers a strong call to action that seems to actually work – to make people put their hands in their pockets. Isn’t it wrong to risk jeopardising that given the possibility that people will focus only on the arguments I give against extreme requirements to aid?

On reflection, I don’t think what I do is immoral philosophy. The job of moral philosophers is to help people to decide what to believe about moral issues on the basis of reasoned reflection. Moral philosophers provide arguments and critique the arguments of others. We won’t be able to do this properly if we shy away from attacking some arguments because it is good for people to believe them.

In addition, the Singer/Unger position doesn’t really offer a clear, simple conclusion about what to do. For Singer and Unger, there is a nice simple answer about what morality requires us to do: keep giving until giving more would cost us something more morally significant than the harm we could prevent; in other words, keep giving till you have given most of your money away. However, this doesn’t translate into a simple answer about what we should do, overall. For, on Singer’s view, we might not be rationally required or overall required to do what we are morally required to.

This need to separate moral requirements from overall requirements is a result of the extreme, impersonal view of morality espoused by Singer. The demands of Singer’s morality are so extreme it must sometimes be reasonable to ignore them. A more modest understanding of morality, which takes into account the agent’s special concern with what is near and dear to her, avoids this problem. Its demands are reasonable so cannot be reasonably ignored. Looked at in this way, my position gives a clearer and simpler answer to the question of what we should do in response to global poverty. It tells us both what is morally and rationally required. Providing such an answer surely can’t be immoral philosophy.

Headline image credit: Devil gate, Paris, by PHGCOM (Own work). CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Immoral philosophy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe works of Walter Savage LandorWorking in the intensive care unit: an interview with Dr. Robert StevensImmigration in the American west

Related StoriesThe works of Walter Savage LandorWorking in the intensive care unit: an interview with Dr. Robert StevensImmigration in the American west

January 24, 2015

Clues, code-breaking, and cruciverbalists: the language of crosswords

The recent release of The Imitation Game has revealed the important role crosswords played in the recruitment of code-breakers at Bletchley Park. In response to complaints that its crosswords were too easy, The Daily Telegraph organised a contest in which entrants attempted to solve a puzzle in less than 12 minutes. Successful competitors subsequently found themselves being approached by the War Office, and later working as cryptographers at Bletchley Park.

The birth of the crossword

The crossword was the invention of Liverpool émigré Arthur Wynne, whose first puzzle appeared in the New York World in 1913. This initial foray was christened a Word-Cross; the instruction in subsequent issues to ‘Find the missing cross words’ led to the birth of the cross-word. Although Wynne’s invention was initially greeted with scepticism, by the 1920s it had established itself as a popular pastime, entertaining and frustrating generations of solvers, solutionists, puzzle-heads, and cruciverbalists (Latin for ‘crossworders’).

“Bletchley Park.” Photo by Adam Foster. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

“Bletchley Park.” Photo by Adam Foster. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.Crosswords consist of a grid made up of black and white boxes, in which the answers, also known as lights, are to be written. The term light derives from the word’s wider use to refer to facts or suggestions which help to explain, or ‘cast light upon’, a problem. The puzzle consists of a series of clues, a word that derives from Old English cleowen ‘ball of thread’. Since a ball of thread could be used to help guide someone out of a maze – just as Ariadne’s thread came to Theseus’s aid in the Minotaur’s labyrinth – it developed the figurative sense of a piece of evidence leading to a solution, especially in the investigation of a crime. The spelling changed from clew to clue under the influence of French in the seventeenth century; the same shift affected words like blew, glew, rew, and trew.

Anagrams, homophones, and Spoonerisms: clues in crosswords

In the earliest crosswords the clue consisted of a straightforward synonym (Greek ‘with name’) – this type is still popular in concise or so-called quick crosswords. A later development saw the emergence of the cryptic clue (from a Greek word meaning ‘hidden’), where, in addition to a definition, another route to the answer is concealed within a form of wordplay. Wordplay devices include the anagram, from a Greek word meaning ‘transposition of letters’, and the charade, from a French word referring to a type of riddle in which each syllable of a word, or a complete word, is described, or acted out – as in the game charades. A well-known example, by prolific Guardian setter Rufus, is ‘Two girls, one on each knee’ (7). Combining two girls’ names, Pat and Ella, gives you a word for the kneecap: PATELLA.

Punning on similar-sounding words, or homophones (Greek ‘same sound’), is a common trick. A reference to Spooner requires a solver to transpose the initial sounds of two or more words; this derives from a supposed predisposition to such slips of the tongue in the speech of Reverend William Archibald Spooner (1844–1930), Warden of New College Oxford, whose alleged Spoonerisms include a toast to ‘our queer dean’ and upbraiding a student who ‘hissed all his mystery lectures’. Other devious devices of misdirection include reversals, double definitions, containers (where all or part of word must be placed within another), and words hidden inside others, or between two or more words. In the type known as &lit. (short for ‘& literally so’), the whole clue serves as both definition and wordplay, as in this clue by Rufus: ‘I’m a leader of Muslims”. Here the word play gives IMA+M (the leader, i.e. first letter, of Muslims), while the whole clue stands as the definition.

Crossword compilers and setters

Crossword compilers, or setters, traditionally remain anonymous (Greek ‘without name’), or assume pseudonyms (Greek ‘false name’). Famous exponents of the art include Torquemada and Ximenes, who assumed the names of Spanish inquisitors, Afrit, the name of a mythological Arabic demon hidden in that of the setter A.F.Ritchie, and Araucaria, the Latin name for the monkey puzzle tree. Some crosswords conceal a name or message within the grid, perhaps along the diagonal, or using the unchecked letters (or unches), which do not cross with other words in the grid. This is known as a nina, a term deriving from the practice of the American cartoonist Al Hirschfield of hiding the name of his daughter Nina in his illustrations.

If you’re a budding code-cracker and fancy pitting your wits against the cryptographers of Bletchley Park, you can find the original Telegraph puzzle here.

But remember, you only have 12 minutes to solve it.

A version of this blog post first appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Image Credit: “Crosswords.” Photo by Jessica Whittle. CC by NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Clues, code-breaking, and cruciverbalists: the language of crosswords appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWalking in a winter wonderland . . . of wordsOrphants to foster kids: a century of AnnieThe advantage of ‘trans’

Related StoriesWalking in a winter wonderland . . . of wordsOrphants to foster kids: a century of AnnieThe advantage of ‘trans’

Working in the intensive care unit: an interview with Dr. Robert Stevens

When patients are discharged from the intensive care unit it’s great news for everyone. However, it doesn’t necessarily mean the road to recovery is straight. As breakthroughs and new technology increase the survival rate for highly critical patients, the number of possible further complications rises, meaning life after the ICU can be complex. Joe Hitchcock from Oxford University Press’s medical publishing team spoke to Dr. Robert D. Stevens, Associate Professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, to find out more.

Can you tell us a little about your career?

As a junior doctor in the intensive care unit, I observed that prowess in resuscitation is a double edged sword. We were getting better and better at promoting survival, but at what cost in the long term? I decided I would dedicate my career to the recovery process that follows severe illnesses and injuries. Currently, my team has several cohort studies under way in human subjects with head injury, stroke and sepsis. We’re looking at their long term outcomes and also imaging their brains. I have a laboratory in which we are studying a range of neurologic readouts in mice following brain injury. We’re looking at the biology of neuronal plasticity and studying stem cells as a treatment to promote recovery of function.

What is Post-ICU medicine and what does it aim to achieve?

Medicine is increasingly a victim of its own successes. People are surviving complex and terrifying illnesses, which only years ago would almost certainly have been fatal. This means there is an ever-growing population of “survivors”. Like survivors of cancer, survivors of intensive care bring with them an entirely new set of clinical problems, demanding new approaches. We propose Post-ICU Medicine as an umbrella term for this new domain of medical practice and research, which is specifically concerned with the biology, diagnosis and treatment of illnesses and disabilities resulting from critical illness.

What do you mean by the “legacy” of critical illnesses?

The “legacy” of critical illness refers to what people “carry with them” after living through a life threatening illness in the intensive care unit (ICU). It is the sum of consequences, both physical and mental, some temporary others permanent, which unfold in the weeks, months and years after someone is discharged from the ICU.

In what ways might a patient’s post-ICU experience differ from public/idealized expectations?

There is a widely held perception, or perhaps an anticipation, that acute and severe illnesses, such as sepsis or respiratory failure, are a zero-sum game: You may die from this illness, but if you survive you have a good chance of recovering completely and of going on with your life as if nothing had happened. This notion has been turned on its head. We know now that the post-ICU experience presents physical and psychological challenges for a high proportion of patients. Even the most fortunate, those we might regard as having recovered successfully, often acknowledge problems months after they have left the hospital. They report that they feel weak, have difficulties concentrating, are impulsive, anxious or depressed. When tested formally, they are often score below population means on tests of memory, attention, and functional status.

Clinicians in Intensive Care Unit by Calleamanecer. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Clinicians in Intensive Care Unit by Calleamanecer. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Have you observed patterns in the way patients recover?

I do not know that there are any easily classifiable patterns. There are countless possible trajectories of recovery which we are only beginning to characterize with some degree of scientific rigor. In reality, just as each patient is biologically unique, so too is his or her recovery. One of the main tasks of Post-ICU Medicine is to identify and validate markers (e.g. genetic variants, protein expression) that allow us to predict and track recovery patterns with a much higher level of confidence and reliability.

How do you assess and treat patients who have a multitude of Post-ICU conditions, psychological and physical?

Ideally, a single provider would be able to follow and treat patients in the post-ICU period. However, the range of different problems — neurologic, cognitive, psychological, cardiac, pulmonary, renal, musculoskeletal, digestive, nutritional, endocrine, social, economic — which these patients present with, are beyond the scope of even a very knowledgeable practitioner. Some groups that specialize in post-ICU follow up care have adopted a different approach, in which patients are evaluated by a multi-disciplinary “Recovery Team” with a wide array of minimally-overlapping knowledge and skills. The latter may include internists, specialists in rehabilitation, psychiatrists, neuropsychologists, neurologists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, orthopaedic surgeons, rheumatologists, and social workers. Patients recovering from critical illness are evaluated periodically and referred to the different members of the Recovery Team depending on clinical symptoms and signs. While evidence is mounting regarding the benefits of integrated post-ICU Recovery Team approach, such interventions area resource intensive and costly and are not currently available to the vast majority of recovering post-ICU patients.

Is it possible to accurately predict patient rehabilitation and recovery trajectories?

This is the “holy grail” of post-ICU medicine, and even of critical care medicine more generally. We desperately need discriminative methods to predict recovery trajectories. Current predictive approaches rely on multiple logistic regression models often using a mix of demographic and clinical severity variables. These models are terribly inaccurate, to the point of being quite useless in the clinical setting. New approaches are needed which analyse large biological datasets – patterns of gene and protein expression, changes in the microbiome, changes in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, alterations in brain functional and metabolic activity. The great hope is that models emerging from these more sophisticated data sets will allow individualized or personalized approaches to outcome prediction and treatment.

If recovery is considered a gradated process, when is a patient “cured”?

The World Health Organization states that physical and mental well-being are a right of all human beings. It is likely that the insults and injuries suffered in the ICU can never be completely healed or cured. However, the good news is that some ICU survivors achieve astonishing levels of recovery. We need to study these individuals – the ones who do very well and surpass all expectations for recovery– as they seem to have biological or psychological characteristics (e.g. resilience factors, motivation) which set them apart. Knowing more about these characteristics may help us treat those with less favorable recovery profiles.

What might the post-ICU medicine look like in the distant future?

I believe that mortality will continue to decline for a range of illnesses an injuries encountered in the ICU. The key task will be to maximize health status in those who survive. I expect that major discoveries will be made regarding organ-specific patterns of gene and protein expression and molecular signalling which drive post-injury recovery versus failure — and that this knowledge will enable novel treatment strategies. I anticipate that important advances will be made in the regeneration tissues and organs using stem cell and tissue engineering approaches.

The post Working in the intensive care unit: an interview with Dr. Robert Stevens appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Vegetarian PlantMental contamination in obsessive-compulsive disorderThe works of Walter Savage Landor

Related StoriesThe Vegetarian PlantMental contamination in obsessive-compulsive disorderThe works of Walter Savage Landor

The death of Sir Winston Churchill, 24 January 1965

As anyone knows who has looked at the newspapers over the festive season, 2015 is a bumper year for anniversaries: among them Magna Carta (800 years), Agincourt (600 years), and Waterloo (200 years). But it is January which sees the first of 2015’s major commemorations, for it is fifty years since Sir Winston Churchill died (on the 24th) and received a magnificent state funeral (on the 30th). As Churchill himself had earlier predicted, he died on just the same day as his father, Lord Randolph Churchill, had done, in 1895, exactly seventy years before.

The arrangements for Churchill’s funeral, codenamed ‘Operation Hope Not’, had long been in the planning, which meant that Churchill would receive the grandest obsequies afforded to any commoner since the funerals of Nelson and Wellington. And unlike Magna Carta or Agincourt or Waterloo, there are many of us still alive who can vividly remember those sad yet stirring events of half a century ago. My generation (I was born in 1950) grew up in what were, among other things, the sunset years of Churchillian apotheosis. They may, as Lord Moran’s diary makes searingly plain, have been sad and enfeebled years for Churchill himself, but they were also years of unprecedented acclaim and veneration. During the last decade of his life, he was the most famous man alive. On his ninetieth birthday, thousands of greeting cards were sent, addressed to ‘The Greatest Man in the World, London’, and they were all delivered to Churchill’s home. During his last days, when he lay dying, there were many who found it impossible to contemplate the world without him, just as Queen Victoria had earlier wondered, at the time of his death in 1852, how Britain would manage without the Duke of Wellington.

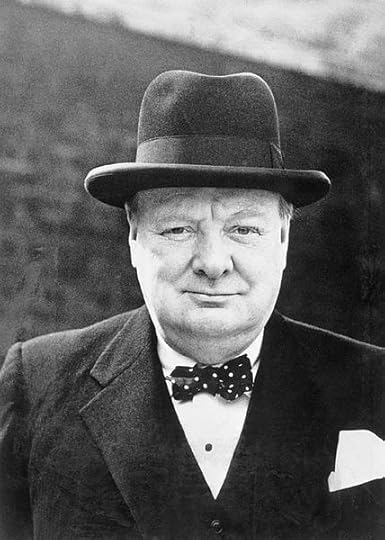

Winston Churchill, 1944. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Winston Churchill, 1944. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Like all such great ceremonial occasions, the funeral itself had many meanings, and for those of us who watched it on television, by turns enthralled and tearful, it has also left many memories. In one guise, it was the final act homage to the man who had been described as ‘the saviour of his country’, and who had lived a life so full of years and achievement and honour and controversy that it was impossible to believe anyone in Britain would see his like again. But it was also, and in a rather different emotional and historical register, not only the last rites of the great man himself, but also a requiem for Britain as a great power. While Churchill might have saved his country during the Second World War, he could not preserve its global greatness thereafter. It was this sorrowful realization that had darkened his final years, just as his funeral, attended by so many world leaders and heads of state, was the last time that a British figure could command such global attention and recognition. (The turn out for Margaret Thatcher’s funeral, in 2013, was nothing like as illustrious.) These multiple meanings made the ceremonial the more moving, just as there were many episodes which made it unforgettable: the bearer party struggling and straining to carry the huge, lead-lined coffin up the steps of St Paul’s; Clement Attlee—Churchill’s former political adversary—old and frail, but determined to be there as one of the pallbearers, sitting on a chair outside the west door brought especially for him; the cranes of the London docks dipping in salute, as Churchill’s coffin was born up the Thames from Tower Pier to Waterloo Station; and the funeral train, hauled by a steam engine of the Battle of Britain class, named Winston Churchill, steaming out of the station.

For many of us, the funeral was made the more memorable by Richard Dimbleby’s commentary. Already stricken with cancer, he must have known that this would be the last he would deliver for a great state occasion (he would, indeed, be dead before the year was out), and this awareness of his own impending mortality gave to his commentary a tone of tender resignation that he had never quite achieved before. As his son, Jonathan, would later observe in his biography of his father, ‘Richard Dimbleby’s public was Churchill’s public, and he had spoken their emotions.’

Fifty years on, the intensity of those emotions cannot be recovered, but many events have been planned to commemorate Churchill’s passing, and to ponder the nature of his legacy. Two years ago, a committee was put together, consisting of representatives of the many institutions and individuals that constitute the greater Churchill world, both in Britain and around the world, which it has been my privilege to chair. Significant events are planned for 30 January: in Parliament, where a wreath will be laid; on the River Thames, where Havengore, the ship that bore Churchill’s coffin, will retrace its journey; and at Westminster Abbey, where there will be a special evensong. It will be a moving and resonant day, and the prelude to many other events around the country and around the world. Will any other British prime minister be so vividly and gratefully remembered fifty years after his—or her—death?

Headline image credit: Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, New Bond Street, London. Sculpted by Lawrence Holofcener. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The death of Sir Winston Churchill, 24 January 1965 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesNew lives added to the Oxford DNB include Amy Winehouse, Elizabeth Taylor, and Claude ChoulesAn interactive timeline of the history of anaesthesiaThe quintessential human instrument

Related StoriesNew lives added to the Oxford DNB include Amy Winehouse, Elizabeth Taylor, and Claude ChoulesAn interactive timeline of the history of anaesthesiaThe quintessential human instrument

The works of Walter Savage Landor

Though he’s largely forgotten today, Walter Savage Landor was one of the major authors of his time—of both his times, in fact, for he was long-lived enough to produce major writing during both the Romantic and the Victorian eras. He kept writing and publishing promiscuously through his long life (he died in his ninetieth year) which puts him in a unique category. Maybe the problem is that he outlived his own reputation. Byron, Shelly and Keats all died in their twenties, and this fact somehow seals-in their importance as poets. Landor’s close friend Southey died at the beginning of the 1840s. Landor lived on, writing and publishing poetry, prose, drama, English and Latin. He forged friendships now with men like Robert Browning—who was deeply influenced by Landor’s writing—John Forster and Charles Dickens (Dickens named his second son Walter Savage Landor Dickens in his friend’s honour). His Victorian reputation was higher than his sales; but and if we’re puzzled by how completely his literary reputation was eclipsed during the 20th century in part that may simply be a function of his prolixity. Landor’s Collected Works was published between 1927 and 1936 in sixteen fat volumes; and even that capacious edition doesn’t by any means contain everything Landor published. It omits, for instance, his voluminous Latin writing—for Landor was the last English writer to produce a substantial body of work in that dead language. In late life he once said ‘I am sometimes at a loss for an English word; for a Latin—never!’

His most substantial prose writings were the Imaginary Conversations: dozens and dozens of prose dialogues between famous historical figures, and occasionally between fictionalised versions of living individuals, varying in length from a few pages each to seventy or eighty. The prose is exquisite, balanced, beautifully mannered and expressed and full of potent epigrams and apothegms on art, society, history, morals and religion. Nobody reads the Imaginary Conversations any more. Then there are the epics—his masterpiece, Gebir (1798), an heroic poem of immense ambition, was greeted by bafflement and ridicule on its initial publication. Landor’s experimental epic idiom was simply too obscure for his readers even to understand—though Lamb claimed the poem has ‘lucid interludes’, and Shelley loved it. Critic William Gifford was less kind: he called the poem ‘a jumble of incomprehensible trash; the effusion of a mad and muddy brain.’ Landor decided to address the question of the poem’s obscurity the best way he knew: by translating the entire epic into Latin (Gebirus, 1803). Ah, those were the days!

He wrote shoals of beautiful lyrics and elegies. He wrote volumes-full of plays, all cod-Shakespearian blank-verse dramas. He wrote historical novels, one of which (Pericles and Aspasia, 1836) is very good. He wrote classical idylls, pastoral poetry—he was a passionate gardener—epigrams and epitaphs in English and Latin. The sheer amount of work he produced may explain the decline in his reputation; for looking new readers surveying the cliff-face of text to climb may find it offputting.

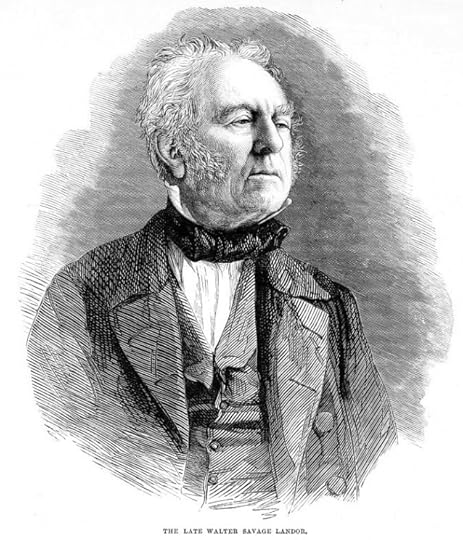

The late Walter Savage Landor. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The late Walter Savage Landor. Public Domain via Wikimedia CommonsIt’s worth the ascent, though. Landor was a choleric individual, given to sudden rages, whilst also magnanimous, kind-hearted and loyal to his friends. Dickens wrote him into Bleak House as the character Boythorn; and a Boythorn-ish energy and vitality very often breaks through the classical refinement of the verse. Unhappily married (he and his wife separated in 1835) he lived through a series of towering, unrequired passions for other, married women. This hopelessness, paradoxically, gives force to some of the best poetry Landor ever wrote: love poems in which the impossibility of love only magnifies the intensity of affection. It’s idea Landor understands better almost than any other writer: that the strongest feelings are predicated upon absence rather than presence. Here’s his short lyric ‘Dirce’ (1831):

Stand close around, ye Stygian set,

With Dirce in one boat convey’d,

Or Charon, seeing, may forget

That he is old, and she a shade.

This says that Dirce is so beautiful that, were he to see her, Charon might ‘forget himself’, and presumably ignore the obstacles of his own dotage and the fact that she is ‘a shade’ to make erotic advances. But in fact the ‘forgetting’ in this lyric involves a much more complex mode of amnesia. It’s tempting to read the poem as being about a particular affect: the melancholy, hopeless desire of an old man for the ideal of youthful female beauty. Desire haunted by the sense that, really, it would be better not to feel desire at all—that to desire is in some sense to ‘forget yourself.’ That idiom is an interesting one, actually; as if an old man feeling sexual desire is in some sense ‘forgetting’ not just that he is old, and that young girls aren’t interested in clapped-out old codgers, but more crucially forgetting that he isn’t the sort of person who feels in that way at all. Perhaps we tend to think of desire not as something to be remembered or forgotten, but as something experienced directly. In its compact way this poem suggests otherwise.

Renunciation is another of Landor’s perennial themes. One of his most famous quatrains runs:

I strove with none, for none was worth my strife;

Nature I loved; and next to Nature, Art.

I warmed both hands before the fire of life;

It sinks, and I am ready to depart.

Written in 1849, on the occasion of Landor’s 74th birthday, this has a certain clean dignity, both stylistically and in terms of what it is saying; although it takes part of its force from the knowledge that (as I mention above) Landor actually strove with people all the time, all through his life: personally, cholerically, in law courts, in print and face-to-face. The second line of the poem, by (it seems to me) rather pointedly omitting ‘people’ from the things that Landor has spent his life loving, rather reinforces this notion. One consequence of a man, particularly a large man like Landor, standing in front of the fire to warm his hands is to block off the heat from everybody else in the room. And that seems appropriate too, somehow.

Featured image credit: ‘Inscription from Walter Savage Landor (1775-1864) to Robert Browning (1812-1889)’ by Provenance Online Project. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr

The post The works of Walter Savage Landor appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesImmigration in the American westThe quintessential human instrumentMental contamination in obsessive-compulsive disorder

Related StoriesImmigration in the American westThe quintessential human instrumentMental contamination in obsessive-compulsive disorder

January 23, 2015

Building community and ecoliteracy through oral history

For our second blog post of 2015, we’re looking back at a great article from Katie Kuszmar in The Oral History Review (OHR), “From Boat to Throat: How Oral Histories Immerse Students in Ecoliteracy and Community Building” (OHR, 41.2.) In the article, Katie discussed a research trip she and her students used to record the oral histories of local fishing practices and to learn about sustainable fishing and consumption. We followed up with her over email to see what we could learn from high school oral historians, and what she has been up to since the article came out. Enjoy the article, and check out her current work at Narrability.com.

In the article, you mentioned that your students ’ youthful curiosity, or lack of inhibition, helped them get answers to tough questions. Can you think of particular moments where this made a difference? Were there any difficulties you didn’t expect, working with high school oral historians?

One particular moment was at the end of the trip. Our final interview was with the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s (MBA) Seafood Watch public relations coordinator, who was kind enough to arrange the fisheries historian interviews and offered to be one of the interviewees as well. When we finally interviewed the coordinator, the most burning question the students had was whether or not Seafood Watch worked directly with fishermen. The students didn’t like her answer. She let us know that fishermen are welcome to approach Seafood Watch and that Seafood Watch is interested in fishermen, but they didn’t work directly with fishermen in setting the standards for their sustainable seafood guidelines. The students seemed to think that taking sides with fishermen was the way to react. When we left the interview they were conflicted. The Monterey Bay Aquarium is a well-respected organization for young people in the area. The aquarium itself is full of nostalgic memories for most students in the region who visit the aquarium frequently on field trips or on vacation. How could such a beloved establishment not consider fishermen voices, for whom the students had just built a newfound respect? It was a big learning moment about bureaucracy, research, empathetic listening, and the usefulness of oral history.

After the interview, when the students cooled off, we discussed how the dynamics in an interview can change when personal conflicts arise. The narrator may even change her story and tone because of the interviewer’s biases. We explored several essential questions that I would now use for discussion before interviews were to occur, for I was learning too. Some questions that we considered were: When you don’t agree with your narrator, how do you ask questions that will keep the communication safe and open? How do you set aside your own beliefs from the narrator, and why is this important when collecting oral history? In other words, how do you take the ego out of it?

Oral history has power in this way: voices can illuminate the issues without the need for strong editorializing.

The students were given a learning opportunity from which I hoped we all could gain insight. We discussed how if you can capture in your interview the narrator’s perspective (even if different than your own or other narrators for that matter), then the audience will be able to see discrepancies in the narratives and gather the evidence they need to engage with the issues. Hearing that Seafood Watch doesn’t work with fishermen might potentially help an audience to ask questions on a larger public scale. Considering oral history’s usefulness in engaging the public, inspiring advocacy, and questioning bureaucracy might be a powerful way for students to engage in the process without worrying about trying to prove their narrators wrong or telling the audience what to think. Oral history has power in this way: voices can illuminate the issues without the need for strong editorializing. This narrative power can be studied beforehand with samples of oral history, as it can also be a great way for students to reflect metacognitively on what they have participated in and how they might want to extend their learning experiences into the real world. Voice of Witness (VOW) contends that students who engage in oral history are “history makers.” What a powerful way to learn!

How did this project start? Did you start with wanting to do oral history with your students, or were you more interested in exploring sustainability and fall into oral history as a method?

Being a fisherwoman myself and just having started commercial fishing with my husband who is a fishmonger, I found my two worlds of fishing and teaching oral history colliding. Even after teaching English for ten years because of my love of storytelling, I have long been interested in creating experiential learning opportunities for students concerning where food comes from and sustainable food hubs.

Through a series of uncanny events connecting fishing and oral history, the project seemed to fall into place. I first attended an oral history for educators training through a collaborative pilot program created by VOW and Facing History and Ourselves (FHAO). After the training, I mentored ten seniors at my school to produce oral history Senior Service Learning Projects that ended in a public performance at a local art museum’s performance space. VOW was integral in my first year’s experience with oral history education. I still work with VOW and sit on their Education Advisory Board, which helps me to continue my engagement in oral history education.

In the same year as the pilot program with VOW, I attended the annual California Association of Teachers of English conference in which the National Oceanic Atmospheric Association’s (NOAA) Voices of the Bay (VOB) program coordinator offered a training. The training offered curriculum strategies in marine ecology, fishing, economics, and basic oral history skill-building. To record interviews, NOAA would help arrange interviews with local fishermen in classrooms or at nearby harbors. The interviews would eventually go into a national archive called Voices from the Fisheries.

The trainer for VOB and I knew many of the same fishermen and mongers up and down the central and north (Pacific) coast. I arranged a meeting between the two educational directors of VOW and VOB, who were both eager to meet each other, as they both were just firing up their educational programs in oral history education. The meeting was very fruitful for all of us, as we brainstormed new ways to approach interdisciplinary oral history opportunities. As such, I was able to synthesize curriculum from both programs in preparing my students for the immersion trip, considering sustainability as an interdependent learning opportunity in environmental, social, and economic content. When I created the trip I didn’t have a term for what the outcome would be, except that I had hoped they would become aware more aware of sustainable seafood and how to promote its values. Ecoliteracy was a term that came to fruition after the projects were completed, but I think it can be extremely valuable as a goal in interdisciplinary oral history education.

I believe oral history education can help to shape our students into compassionate critical thinkers, and may even inspire them to continue to interview and listen empathetically to solve problems in their personal, educational, and professional futures.

What pointers can you give to other educators interested in using oral history to engage their students?

With all the material out there, I feel that educators have ample access to help prepare for projects. In the scheme of these projects, I would advise scheduling time for thoughtful processing or metacognitive reflection. All too often, it is easy to focus on the preparation, conducting and capturing the interviews, and then getting something tangible done with it. Perhaps, it is embedded in the education world of outcome-based assessment: getting results and evidence that learning is happening. With high school students, the experience of interviewing is an extremely valuable learning tool that could easily get overlooked when we are focusing on a project

For example, on an immersion trip to El Salvador with my high school students, we were given an opportunity to interview the daughter of the sole survivor of El Mozote, an infamous massacre that happened at the climax of the civil war. The narrator insisted on telling us her and her mother’s story, despite the fact that she had just gotten chemotherapy the day prior. She said that her storytelling was therapeutic for her and helped her feel that her mother, who had passed away, and all those victims of the massacre would not die in vain. This was such heavy content for her and for us as her audience. We all needed to talk, be quiet about it, cry about it, and reflect on the value of the witnessing. In the end, it wasn’t the deliverable that would be the focus of the learning, it was the actual experience. From it, compassion was built in the students, not just for El Salvadorian victims and survivors, but on a broader scale for all people who face civil strife and persecution. After such an experience, statistics were not just numbers anymore, they had a human face. This, to date, for me has been the most valuable part of oral history education: the transformation that can occur during the experience of an interview, as opposed to the product produced from it. For educators, it is vital to facilitate a pointed and thoughtful discussion with the interviewer to hone in on the learning and realize the transformation, if there is one. The discussion about the experience is essential in understanding the value of the oral history interviewing.

Do you have plans to do similar projects in the future?

After such positive experiences with oral history education, I wanted a chance to actively be an oral historian who captures narratives in issues of sustainable food sources. I have transitioned from teaching to running my own business called Narrability with the mission to build sustainability through community narratives. I just completed a small project, in which I collected oral histories of local fishermen called: “Long Live the King: Storytelling the Value of Salmon Fishing in the Monterey Bay.” Housed on the Monterey Bay Salmon and Trout Project (MBSTP) website, the project highlights some of the realities connected to the MBSTP local hatchery net pen program that augments the natural Chinook salmon runs from rivers in the Sacramento area to be released into the Monterey Bay. Because of drought, dams, overfishing, and urbanization, the Chinook fishery in the central coast area has been deeply affected, and the need for a net pen program seems strong. In the Monterey Bay, there have been many challenges in implementing the Chinook net pen program due to the unfortunate bureaucracy of a discouraging port commission out of the Santa Cruz harbor. Because of the challenges, the oral histories that I collected help to illustrate that regional Chinook salmon fishing builds environmental stewardship, family bonding, community building, and provides a healthy protein source.

Through Narrability, I have also been working on developing a large oral history program with a group of organic farming, wholesale, and certification pioneers. As many organic pioneers face retirement, the need for their history to be recorded is growing. Irene Reti sparked this realization in her project through University of California, Santa Cruz: Cultivating a Movement: An Oral History Series on Organic Farming & Sustainable Agriculture on California’s Central Coast. Through collaboration with some of the major players in organics, we aim to build a comprehensive national collection of the history of organics for the public domain.

Is there anything you couldn ’ t address in the article that you ’ d like to share here?

I know being a teacher can be time crunched, and once interviews are recorded, students and teachers want to do something tactile with the interviews (podcasts/narratives/documentaries). I encourage educators to implement time to reflect on the process. I wished I would have done more reflective processing in this manner: to interview as a class; to discuss the experience of interviewing and the feelings elicited before, during and after an interview; to authentically analyze how the interviews went, including considering narrator dynamics. In many cases, the skills learned and personal growth is not the most tangible outcome. Despite this, I believe oral history education can help to shape our students into compassionate critical thinkers, and may even inspire them to continue to interview and listen empathetically to solve problems in their personal, educational, and professional futures. This might not be something we can grade or present as a deliverable, it might be a long-term effect that grows with a students’ life long learning.

Image Credit: Front entrance of the Aquarium. Photo by Amadscientist. CC by SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Building community and ecoliteracy through oral history appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesUsing voice recognition software in oral history transcriptionThe Vegetarian PlantInsecticide, the fall armyworm, and maize in Mexico

Related StoriesUsing voice recognition software in oral history transcriptionThe Vegetarian PlantInsecticide, the fall armyworm, and maize in Mexico

An interactive timeline of the history of anaesthesia

The field of anaesthesia is a subtle discipline, when properly applied the patient falls gently asleep, miraculously waking-up with one less kidney or even a whole new nose. Today, anaesthesiologists have perfected measuring the depth and risk of anaesthesia, but these breakthroughs were hard-won. The history of anaesthesia is resplendent with pus and cadavers, each new development moved one step closer to the art of the modern anaesthesiologist, who can send you to oblivion and float you safely back. This timeline marks some of the most macabre and downright bizarre events in its long history.

Heading image: Junker-type inhaler for anaesthesia, London, England, 1867-1 Wellcome L0058160. Wellcome Library, London. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post An interactive timeline of the history of anaesthesia appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesJust one of the millions of victims of his World Communist RevolutionImmigration in the American westThe quintessential human instrument

Related StoriesJust one of the millions of victims of his World Communist RevolutionImmigration in the American westThe quintessential human instrument

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 237 followers