Oxford University Press's Blog, page 709

January 23, 2015

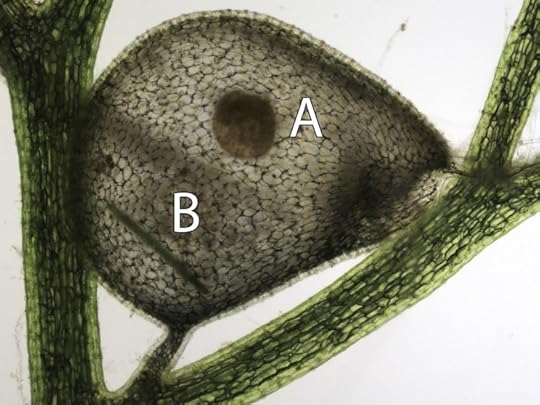

The Vegetarian Plant

Meet Utricularia. It’s a bladderwort, an aquatic carnivorous plant, and one of the fastest things on the planet. It can catch its prey in a millisecond, accelerating it up to 600g.

Once caught inside the prey suffocates and digestive enzymes break down the unfortunate creature for its nutrients. Anything small enough to be pulled in won’t know their mistake until it’s too late. But as lethal as the trap is, it did seem to have some flaws. The traps don’t just catch animals, they catch anything that gets sucked in, so often that’s algae and pollen too.

A team at the University of Vienna led by Marianne Koller-Peroutka and Wolfram Adlassnig closely examined Utricularia and found the plants were not very efficient killers. Studying over 2000 traps showed that only about 10% of the objects sucked in were animals. Animals are great if you want nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, but half of the catch was algae and a third pollen.

What was more puzzling was that not all the algae entered with an animal. If a bladder is left for a long while, it will trigger anyway. No animal is needed; algae, pollen, and fungi will enter. Is this a sign that the plant is desperate for a meal, and hoping an animal is passing? Koller-Peroutka and Adlassnig found that the traps catching algae and pollen grew larger and had more biomass. Examining the bladders under a microscope showed that algae caught in the traps died and decayed. This was more evidence that it’s happy to eat other plants too. It seems that it’s not just animals that Utricularia is hunting.

Koller-Peroutka and Adlassnig say this is why Utricularia is able to live in places with comparatively few animals. Nitrogen from animals and other elements from plants mean it is happy with a balanced diet. It can grow more and bigger traps, and use these for catching animals or plants or both.

Fortunately even the big traps only catch tiny animals, so if someone has bought you one for Christmas you can leave it on the dinner table without losing your turkey and trimmings in a millisecond.

Photos courtesy of Alun Salt.

The post The Vegetarian Plant appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesInsecticide, the fall armyworm, and maize in MexicoCelebrating Women in STEMAre wolves endangered with extinction in Alaska?

Related StoriesInsecticide, the fall armyworm, and maize in MexicoCelebrating Women in STEMAre wolves endangered with extinction in Alaska?

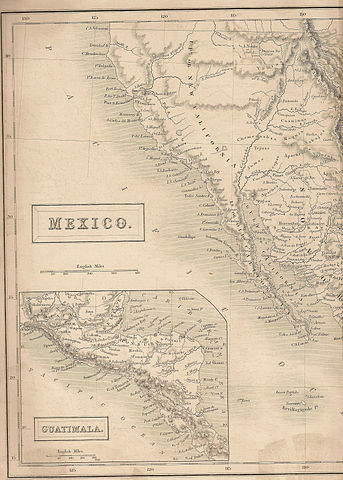

Immigration in the American west

The headline reads: “Border State Governor Issues Dire Warning about Flood of Undocumented Immigrants.” And here’s the gist of the story: In a letter to national officials, the governor of a border state sounded another alarm about unchecked immigration across a porous boundary with a neighboring country. In the message, one of several from border state officials, the governor acknowledged that his/her nation had once welcomed immigrants from its neighbor, but recent events taught how unwise that policy was. He/she insisted that many of the newcomers to his/her state were armed and dangerous criminals. Even those who came to work threatened to overwhelm the state’s resources and destabilize the social order.

Indeed, unlike earlier immigrants from the neighboring nation who had adapted to their new homeland and its traditions, more recent arrivals resisted assimilation. Instead, they continued to speak in their native tongue and maintain attachments to their former nation, sometimes carrying their old flag in public demonstrations. Worse still, the governor admitted that his/her nation seemed unwilling to “arrest” the flow of these undocumented aliens. Yet, unless the “incursions” were halted, the “daring strangers,” who are “gradually outnumbering and displacing us,” would turn us into “strangers in our own land.”

Today’s headline? It could be. The governor’s fears certainly ring familiar. Indeed, the warning sounds a lot like ones issued by Governor Rick Perry of Texas or Jan Brewer of Arizona. But this particular alarm emanated from California. That might make Pete Wilson the author of this message. Back in the 1990s, he was very vocal about the dangers that illegal immigration posed to his state and the United States. As governor, Wilson championed the “Save Our State” ballot initiative that cut illegal aliens from access to state benefits such as subsidized health care and public education. He campaigned on behalf of the initiative (Proposition 187) and made it a centerpiece of his 1994 re-election campaign.

Wilson, however, was not the source of the letter cited above. In fact, this warning dates back to 1845, almost 150 years before Proposition 187 appeared on the scene. Its author was Pio Pico, governor of the still Mexican state of California.

The unsanctioned immigrants about whom Pico worried were from the United States. Pico had reason to be concerned, especially as he reflected on events in Texas. There, the Mexican government had opted to encourage immigration from the United States. Beginning in the 1820s and continuing into the 1830s, Americans, primarily from the southern United States, poured into Texas.

Map of CA, NV, UT and western AZ when they were part of Mexico, “California1838″, by DigbyDalton. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Map of CA, NV, UT and western AZ when they were part of Mexico, “California1838″, by DigbyDalton. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

By the mid-1830s, they outnumbered Tejanos (people with Mexican roots) by almost ten to one. Demanding provincial autonomy, the Americans clashed with Mexican authorities determined to enforce the rule of the national government. In 1836, a rebellion commenced, and Texans won their war of secession. Nine years later, the United States annexed Texas. And now, claimed Pico, many officials of the United States government openly coveted California, their expansionist designs abetted by American immigrants to California.

In retrospect, the policy of promoting American immigration into northern Mexico looks as dangerous as Pico deemed it and as counterintuitive as it has seemed to subsequent generations. Why invite Americans in if a chief goal was to keep the United States out? Still, the policy did not appear so paradoxical at the time. There were, in fact, encouraging precedents. Spain had attempted something similar in the Louisiana Territory in the 1790s, though the territory’s transfer back to France and then to the United States had aborted that experiment. More enduring was what the British had done in Upper Canada (now Ontario). Americans who crossed that border proved themselves amenable to a shift in loyalties, which showed how tenuous national attachments remained in these years. From this, others could draw lessons: the keys to gaining and holding the affection of American transplants was to protect them from Indians, provide them with land on generous terms, require little from them in the way of taxes, and interfere minimally in their private pursuits.

For a variety of reasons, Mexico had trouble abiding by these guidelines, and, in response, Americans did not abide by Mexican rules. In Texas, American immigrants destabilized Mexican rule. In California, as Pico feared, the “daring strangers” overwhelmed the Mexican population, though the brunt of the American rush did not commence until after the discovery of gold in 1848. By then, Mexico had already lost its war with the United States and ceded California. Very soon, men like Pio Pico found themselves strangers in their own land.

Featured image credit: “Map of USA highlighting West”. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Immigration in the American west appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGender inequality in the labour market in the UKThe economics behind detecting terror plotsJust one of the millions of victims of his World Communist Revolution

Related StoriesGender inequality in the labour market in the UKThe economics behind detecting terror plotsJust one of the millions of victims of his World Communist Revolution

January 22, 2015

Insecticide, the fall armyworm, and maize in Mexico

From the comfort of a desk, looking at a computer screen or the printed page of a newspaper, it is very easy to ignore the fact that thousands of tons of insecticide are sprayed annually.

Consider the problem of the fall armyworm in Mexico. As scientists and crop advisors, we’ve worked for the past two decades trying to curb its impact on corn yield. We’ve tested dozens of chemicals to gain some control over this pest on different crops.

A couple of years ago, we were comparing information on the number of insecticide applications needed to battle this worm during a break of a technical meeting. Anecdotal information from other parts of the country got into the conversation. Some colleagues reported that the fall armyworm wasn’t the worst pest in a particular region of Mexico and it was easy to control with a couple of insecticide applications. Others mentioned that up to six sprays were necessary in other parts of the country. Wait a second, I said, that is completely ridiculous and tremendously expensive to use so much insecticide in maize production.

At that point we decided to contact more professionals throughout Mexico and put together a geographical and seasonal ‘map’ of the occurrence of corn pests and the insecticides used in their control. Our report was compiled doing simple arithmetic and the findings really surprised us: a conservative estimate of 3,000 tons of insecticidal active ingredient are used against just the fall armyworm every year in Mexico. No wonder our country has the highest use of pesticide per hectare of arable land in North America.

Spodoptera frugiperda (fall armyworm). CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Spodoptera frugiperda (fall armyworm). CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Mexican farmers are stuck on what has been called ‘the pesticide treadmill.’ The first insecticide application sometimes occurs at the time that maize seed is put in the ground, then a second one follows a couple of weeks later, then another, and another; this process usually involves the harshest insecticides, or those that are highly toxic for the grower and the environment, because they are the cheapest. A way of curtailing these initial applications can be achieved by genetically-modified (GM) maize that produces its own very specific and safe insecticide. Not spraying against pests in the first few weeks of maize development allows the beneficial fauna (lacewings, ladybird beetles, spiders, wasps, etc.) to build their populations and control maize pests; simply put, it enables the use of biological control. The combination of GM crops and natural enemies is an essential part of an integrated pest management program — a successful strategy employed all over the world to control pests, reducing the use of insecticides, and helping farmers to obtain more from their crop land.

We have good farmers in Mexico, a great diversity of natural enemies of the fall armyworm and other maize pests, and growers that are familiar with the benefits of using integrated pest management in other crop systems. Now we need modern technology to fortify such a program in Mexican maize.

Mexican scientists have developed GM maize to respond to some of the most pressing production needs in the country, such as lack of water. Maize hybrids developed by Mexican research institutions may be useful in local environments (e.g., tolerant to drought and cold conditions). These local genetically-engineered maize varieties go through the same regulatory process as corporate developers.

At present, maize pest control with synthetic insecticides has been pretty much the only option for Mexican growers. They use pesticides because controlling pests is necessary for obtaining a decent yield, not because they are forced to spray them by chemical corporations or for being part of a government program. This constitutes an urgent situation that demands solutions. There are a few methods to prevent most of these applications, genetic engineering being one of them. Other countries have reduced their pesticide use by 40% due to the acceptance of GM crops. Mexico, the birthplace of maize, only produces 70% of the maize it consumes because growers face so many environmental and pest control challenges, with heavy reliance on synthetic pesticides. Accepting the technology of GM crops, and educating farmers on better management practices, is key for Mexico to jump off the pesticide treadmill.

Image Credit: Maize diversity. Photo by Xochiquetzal Fonseca/CIMMYT. CC BY SA NC ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Insecticide, the fall armyworm, and maize in Mexico appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCelebrating Women in STEMThe economics behind detecting terror plotsAre wolves endangered with extinction in Alaska?

Related StoriesCelebrating Women in STEMThe economics behind detecting terror plotsAre wolves endangered with extinction in Alaska?

The quintessential human instrument

In late 2014, one particular video of a singer became immensely popular on Facebook. At first I thought my perception of its popularity might be skewed; I’m a singer, and have many friends who are singers, so there’s probably some selection bias in my sampling of popular posts on social media. But eventually I actually clicked on one of the many postings of the video on my feed, and with its 7.4 million views, it seemed likely that it was more than just my singer friends who had been watching it:

Overtone singing, defined in Grove Music Online as “A vocal style in which a single performer produces more than one clearly audible note simultaneously”, has been in existence for thousands of years, most famously in east central Asia. But I had never seen this much attention focused on it at once. The video is jaw-droppingly cool, in part because what’s happening doesn’t seem possible. But then, not that many people understand how singing just one note at a time actually works.

Simply trying to explain everything that happens when we breathe and phonate (i.e., make a vocal sound) requires discussion of various complex, unconscious physical phenomena. As the Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments article “Voice” puts it:

Phonation takes place during exhalation as the respiratory system supplies air through the vibrating vocal folds, which interrupt and break the air stream into smaller units or puffs of air. The resulting sounds are filtered through a resonator system and then transmitted outside the mouth. Singing, speaking, humming, and other vocal sounds usually involve practised regulation of air pressure and breath-stream mechanics, and balanced control of the inspiratory (chiefly the diaphragm) and expiratory muscles (chiefly the abdominal and intercostal muscles).

Even after understanding all that, it’s clear that what’s happening in the video above is not a typical vocal performance. So when you hear those overtones coming from Anna-Maria Hefele, just what exactly is happening?

Fortunately for all of us, Hefele also made another video which addresses the physics of this phenomenon:

When you sing different vowels, your mouth changes shape to form those vowels. You pull your lips to the side to make an “eee” sound, and your tongue arches up in your mouth; when you make an “ooo” sound, you purse your lips and your tongue flattens out. When you do this, you’re actually changing the shape of your instrument, which in turn changes the harmonics that are stressed above the fundamental frequency (the pitch at which you’re speaking or singing). This is why the vowels sound different from one another. This is clear in Hefele’s training video, where the loudest overtones change from vowel to vowel.

Stress of different overtones is one of the ingredients of timbre, or the quality of a sound beyond its pitch and amplitude. Timbre is what allows us to distinguish between, say, a flute and an oboe playing the same pitch. They simply sound different. This is partially (no pun intended) dependent on the stress of different overtones due to the varying shapes and materials of each instrument.

The neat thing about the voice is that, while we don’t usually change the material, the shape is very flexible, and we can manipulate it to change our timbre. Overtone singing like Hefele’s takes an element of vocal sound and turns it into a new sort of instrument, inverting the typical relationship between instrument and timbre.

Anyone who’s listened to master impressionists or Bobby McFerrin (beyond “Don’t worry, be happy”) can attest to the versatility of the human voice. Vocalists are the shape-shifters of the instrument world. But comparing the 52,251 views of Hefele’s visualization video with the 7.4 million views of her performance video, it seems like we also appreciate the masters of timbre-bending the same way we appreciate magicians; most of us would rather watch the trick than see it explained.

In the newly published second edition of the Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments, the voice is called “The quintessential human instrument.” But while almost all of us have voices, very few of us understand what is happening when we use them. Every once in a while I think it’s beneficial to see something extraordinary, if only so we remember to look at what seems ordinary a little more closely.

Headline image credit: A Sennheiser Microphone. Photo by ChrisEngelsma. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The quintessential human instrument appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSalamone Rossi as a Jew among GentilesTop 10 commercial law cases of 2014A Motown music playlist

Related StoriesSalamone Rossi as a Jew among GentilesTop 10 commercial law cases of 2014A Motown music playlist

Mental contamination in obsessive-compulsive disorder

When we think of obsessive-compulsive disorder or OCD for short, lots of examples spring to mind. For example, someone who won’t shake your hand, touch a door handle, or borrow your pen without being compelled to wash their hands, all because of a fear of germs. I’m sure many of us are guilty of using the phrase “you’re so OCD” to categorize our friends, family, and colleagues who have obsessive cleaning habits or use their antibacterial hand gel a few too many times a day.

Despite this being a very over-simplified idea of OCD, it’s based on an important and common feature for many sufferers; contact contamination fear. Contact contamination can be described as a feeling of dirtiness or discomfort that is felt in response to physical contact with harmful substances, disease or dirt, which will contaminate the body, most often the hands. Relief can be felt in response to cleansing the contaminated areas, for example through hand washing. Much of the focus by academics in previous literature has been on contact contamination, as well as focus from the media, which surrounds us with examples of contamination fears in OCD through TV series such as Obsessive Compulsive Cleaners and Monk.

However, for some sufferers the feelings of discomfort and dirtiness can also be caused without physical contact with something that is dirty or germy. Instead, feelings of contamination can be triggered by association with a contaminated person who has betrayed or harmed the sufferer in some way, or even by their own thoughts, images or memories. This ‘mental contamination’ leads to an internal sense of dirtiness, rather than being localized to a particular body part, and therefore can’t be cleansed away by hand washing. For example, one patient, “Jenny” started feeling internally dirty after she discovered that her husband had been unfaithful and her marriage broke down. She would feel dirty and wash her hands after touching any of his possessions or speaking to him on the telephone. “Steven” also experienced severe mental contamination that was triggered by intrusive images of harming others. The source of mental contamination is not an external contaminant such as blood or dirt but human interaction. The emotional violations that can cause mental contamination include degradation, humiliation, painful criticism, and betrayal.

Sink. Public Domain via Pixabay.

Sink. Public Domain via Pixabay. There is much less knowledge of mental contamination amongst the public, possibly due to a lack of focus on the topic by professionals, meaning we simply don’t recognize examples or situations in which we might feel mentally contaminated. Similar to the normative experience of contact contamination, there are numerous examples of feeling contaminated without touching something dirty in everyday life, for example the washing away of sins when being Baptized, or when cleansing the body for worship; known as Wudu in Islam. Sins here are referring to an internal type of uncleanliness, which can be provoked without contact, for example through having blasphemous thoughts. Another example is not listening to a song which reminds you of an ex-partner who wronged you, as it makes you feel tarnished inside. Even the phrases we use can be seen as representing a form of mental contamination, for example “dirty money”, “muck up”, and “feel like dirt”. Milder forms of mental contamination are prevalent in society, for example in the course of a bitter divorce, where a wronged person develops feelings of contamination that are evoked by direct contact with the violator or indirect contacts such as memories, images or reminders of the violation.

A lack of knowledge of mental contamination is perhaps also due to it being a harder concept to comprehend than contact contamination. We can all understand the math behind contact contamination; you touch something dirty, your hands become dirty, you wash your hands, the dirt is gone, you feel relief. The process makes logical sense, as the cause is visible. Mental contamination can be seen in the same way, it just doesn’t require a visible cause, and often the cause is associated with a previous psychological or physical violation. Without this visible cause for their problems, the true source of discomfort is often unknown to sufferers. Imagine you’re taking part in an experiment, you’re asked to try on a jumper which was brought from a charity shop, and report your feelings. If you know the jumper is physically clean, you’d probably feel fine, no discomfort, you might even like wearing it. Now, imagine being told that the jumper belonged to a murderer, and suddenly for no explainable reason you aren’t okay with wearing it anymore. You have that disturbing, spine-tingling, and shivery feeling as if the jumper were made of tarantulas. Despite knowing the jumper is physically clean, there’s a cloud of dirtiness hanging over it, and you feel mentally contaminated.

Intrusive thoughts associated with mental contamination are normal, but it is the interpretation of the thoughts that is important in determining whether or not the person will then engage in compulsive washing behaviour. To you or me, these are just weird feelings which are easily forgotten, but to someone with mental contamination they are harmful, and could damage their personality in some way. Take the jumper scenario; a person suffering from mental contamination might worry that somehow they will adopt the negative traits of the murderer through their clothing.

The discovery of mental contamination has large and immediate implications for clinical treatment. Cognitive behavioural therapy can be used to effectively treat mental contamination in OCD patients, by changing the meaning or interpretation of obsessive intrusive thoughts, so that they are no longer seen as harmful. Subsequently, this also reduces the frequency of compulsive washing behaviours. For many OCD sufferers Cognitive Behavioural Therapy provides hope that a life free from the daily interference of mental contamination and compulsions is achievable.

The post Mental contamination in obsessive-compulsive disorder appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat is it like to be depressed?Celebrating Women in STEMOur habitat: house

Related StoriesWhat is it like to be depressed?Celebrating Women in STEMOur habitat: house

Celebrating Women in STEM

It is becoming widely accepted that women have, historically, been underrepresented and often completely written out of work in the fields of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM). Explanations for the gender gap in STEM fields range from genetically-determined interests, structural and territorial segregation, discrimination, and historic stereotypes. As well as encouraging steps toward positive change, we would also like to retrospectively honour those women whose past works have been overlooked.

From astronomer Caroline Herschel to the first female winner of the Fields Medal, Maryam Mirzakhani, you can use our interactive timeline to learn more about the women whose works in STEM fields have changed our world.

With free Oxford University Press content, we tell the stories and share the research of both famous and forgotten women.

Featured image credit: Microscope. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Celebrating Women in STEM appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesReplication redux and Facebook dataOf black holes, naked singularities, and quantum gravityAre wolves endangered with extinction in Alaska?

Related StoriesReplication redux and Facebook dataOf black holes, naked singularities, and quantum gravityAre wolves endangered with extinction in Alaska?

January 21, 2015

Our habitat: house

It is astounding how mysterious the origin of such simple words as man, wife, son, god, house, and others like them is. They are old, even ancient, and over time their form has changed very little, sometimes not at all, so that we don’t have to break through a thicket of sound laws to restitute their initial form. They have been monosyllabic for millennia, and even in the reconstructed protolanguage they were only one syllable longer (an ending or a so-called thematic vowel followed by one consonant). But two thousand years ago they would already have puzzled us as they do today. Conventional wisdom suggests that to call a man a man and a house a house, people chose some easily available language material; yet we can seldom recover it.

If we look at the etymology of such well-known words for “house” as French maison, Italian casa, and Russian dom, we will see that they once referred to covering and hiding somebody or something, or to being “put, fitted together.” Users of English dictionaries will find some information about them in the entries on mansion, case “holder,” casement, and dome. Going further, they will discover the current connection between Latin domus and Engl. timber and tame. In light of such facts, the etymology of house, recognized by most language historians, even though sometimes with an ill grace, makes sense. The oldest recorded form of house is hus, with long u (long u is the vowel we hear in Modern Engl. too), and it seems to be related to the verb hide and through it to the noun hut. Hut came to English from French, but French had it from Old High German. Therefore, the comparison is legitimate. Trouble comes from the final consonant -s, for, if hide and hut are cognates, one expects -t or -d, rather than s, at the end of house (hus). This is not a good place for disentangling phonetic niceties, the more so as they have not been disentangled in a perfectly convincing way. We have a better chance of finding out what kind of a place the speakers of Old Germanic called hus.

Henryk Ibsen’s A Doll’s House

Henryk Ibsen’s A Doll’s HouseIn the fourth-century Gothic text, which is a translation of the New Testament, hus occurred only as the second element of the compound gud-hus “(Jewish) temple.” (Gud, of course, means “god”; Germanic had several words for “pagan temple”). The word for what we call “house” was razn. It corresponded to Old Engl. ærn ~ ern ~ ern, still preserved in barn (b- is all that is left of bere “barley”) and saltern “salt works.” The Old Icelandic cognate of razn was rann, and it too lingers in English as the first element of ransack, a borrowing from Scandinavian. There also were other Gothic words for “house,” namely gards and hrot (Engl. yard and quite possibly roost are related to them). No doubt, all of them referred to different structures and buildings, but we should note only one thing: the oldest Germanic family hardly lived in a place called hus.

This conclusion is borne out in a rather unexpected way. There must have been something about the function or appearance or both of the Germanic hus that distinguished it from its counterparts elsewhere, because the word for it made its way into Old Slavic. The Slavs lived in a dom. The hus served other purposes. Since the borrowing goes back to a remote past, we may assume that the word taken over from the Germanic neighbors meant in Slavic approximately or even exactly what it once meant in the lending language. The noun in question is extant practically all over the Slavic-speaking world (though more often in regional dialects than in the Standards). The present day senses of its reflexes do sometimes mean “house” and “home,” but these senses are swamped by “earth house,” “hut” (as in obsolete Polish chyz and Russian khizhina; I have highlighted the stressed root), “the place for building a house,” “a winter shed,” “a shed in the woods,” “storehouse,” hayloft,” “marquee,” “barn (granary),” “closet,” and “storehouse.” Thus, we find all kinds of names for “outhouses.” Even “monastery cell” occurs in the list, and, characteristically, this meaning was ascribed to Gothic hus (allegedly, a one-room structure) in gud-hus. If originally hus denoted a place for temporary protection of people from the elements (“a hut”) or for sheltering grain and other things, the connection of hus and hide is unobjectionable. As noted, it is only the last consonant that spoils the otherwise rather neat picture.

The word is and has always been neuter. The assignment of hus to this gender might be an accident of grammar, but it might be caused by its semantics. Two circumstances made me ask why hus and, incidentally, both Gothic razn and hrot were neuter. First, the situation in Icelandic comes to mind. What was called hús in Old Icelandic (ú designates vowel length, not stress) was not a separate building but a string of “chambers” that made up the farmhouse. Next to the living quarters, often without a partition, a sheepfold was situated; in winter, sheep’s breath served as “fuel” and warmed the room. So I wondered whether perhaps the old hus looked like the medieval Icelandic farm, with the word being coined as a collective plural. Later a singular may have been formed from it. This is a common process.

Then there is the word hotel (French hôtel), with its older form ostel, from which English has ostler. Hotel is related to hospital, hospitality, hospice, and host. The medieval “hotel” first designated any building for human habitation, though the modern sense is also old. Late Latin hospitale is the neuter plural of the adjective hospitalis turned into a noun (the technical term for such a change in grammatical usage is substantivization; thus, hospitale is a substantivized adjective). Again neuter plural! There must have been something in the concept of such “enfilades” that suggested plurality.

The Burning of the Houses of Parliament by JMW Turner

The Burning of the Houses of Parliament by JMW TurnerI am not jumping to conclusions. In etymology, he who jumps and leaps perishes, and I want to live long enough to produces many more posts. But it so happened that in my work I, on various occasions, keep encountering neuter plurals, and in the huge literature on the word house no one seems to have asked why the word is neuter (that is, perhaps someone did, but I missed the relevant place: one can never be sure), so I thought that there would be no harm in mentioning this detail.

As could be expected, etymologists spent some time hunting for distant congeners of house. A Hittite and an Armenian word have been proposed. As far as I can judge, neither has aroused any interest, and probably for good reason. House appears to have been a local (Germanic) coinage, but whether we have discovered its etymon remains unclear. That is why the most cautious dictionaries call house a word of uncertain etymology. It will probably remain such for all eternity. The time depth we command is insufficient for getting to the bottom of things, but we need not worry: this blog was conceived expressly as a forum for discussing obscure words.

Image credits: (1) The Burning of the Houses of Parliament by Turner. Public domain via WikiArt. (2) Alla Nazimova in the 1922 film of A Doll’s House. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Our habitat: house appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMonthly gleanings for December 2014, Part 2Season’s greetings, or “That’s the cheese”Moping on a broomstick

Related StoriesMonthly gleanings for December 2014, Part 2Season’s greetings, or “That’s the cheese”Moping on a broomstick

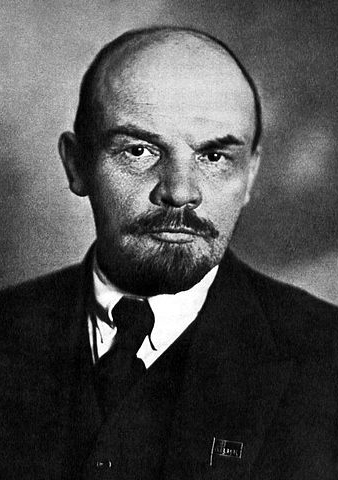

Just one of the millions of victims of his World Communist Revolution

Vladimir Ilich Ulyanov (aka Lenin) died on this day 90 years ago with cerebral vessels so calcified that when tapped with tweezers, they sounded like stone. He was only 53. He hadn’t smoked and, in fact, had prohibited smoking in his presence. He had consumed alcohol sparingly and had exercised regularly, swimming, biking, and walking as often as his schedule allowed. And yet, when only 51 years of age, he had a first stroke, seven months later a second, and then another before suffering his final, fatal one three months shy of his 54th birthday. How could a man so young with none of the usual risk factors for cerebrovascular disease have had cerebral vessels with walls so thick and calcified, that in many places, their lumens were either completely obliterated or narrowed to the dimension of tiny slits?

Syphilis was one of the earliest explanations considered. It is, after all, an infection that attacks the brain, one possibly passed on to Lenin by his mistress, Inessa Armand, a self-professed advocate of free love. However, whereas Treponema pallidum, the bacterium responsible for syphilis, does invade the vessels of the brain, it typically attacks the small arteries of the meninges, the brain’s membranous envelope, not the large feeder vessels responsible for the kind of strokes Lenin had. Moreover, several Wasserman tests (blood tests for syphilis) performed on Lenin prior to his death were all allegedly negative, though it should be noted that the official reports of these tests have since mysteriously vanished.

Lenin, 1920. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Lenin, 1920. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.A more likely explanation for Lenin’s premature cerebrovascular disease, one initially proposed by Dimitri Volkogonov, the first researcher to gain access to Lenin’s secret Soviet files, is that the vessels of his brain were “simply destroyed by the strains of power.” Prior to the October Revolution, Lenin had enjoyed a free and easy existence of literary activities, vacationing in the mountains, and Party squabbles in exile. This changed radically after he became the leader of the World Communist Revolution, when he was forced to work with a driving urgency that found him hardly bothering to undress before falling into an exhausted, troubled sleep. Brief naps no longer refreshed him. Every day brought some new disaster requiring his personal attention. Every day he woke with a dull headache. The tension of dealing with the ever-changing demands of State caused him to erupt in anger with frightening regularity. When his health began to fail, his physicians diagnosed “overstrain of the brain.”

In fact, numerous scientific investigations have since demonstrated a relationship between psychological stress and both cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, through mechanisms that have yet to be fully elucidated. Lenin was subjected to such stress in the extreme as the Supreme Soviet leader. Moreover, he was likely genetically predisposed to the adverse effects of such stress on his cerebrovascular system in that his father died at the same age with neurological complaints similar to his own. In addition, two of his brothers died of coronary artery disease and a sister of a stroke. Thus, Lenin’s genetic code likely dictated that sooner or later he would succumb to cerebrovascular disease, whereas the pressures of directing the World Communist Revolution likely caused this to transpire sooner rather than later.

Headline image credit: Vladimir Lenin speaking to a crowd. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Just one of the millions of victims of his World Communist Revolution appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLaying to rest a 224 year-old controversyWhat is it like to be depressed?Is yoga Hindu?

Related StoriesLaying to rest a 224 year-old controversyWhat is it like to be depressed?Is yoga Hindu?

Oppress Muslims in the West. Extremists are counting on it.

In the aftermath of the Paris terror attacks, the Islamophobia pervading Western democracies is the best recruitment tool for violent extremists.

Reports abound about anti-Islam protests, assaults of Muslim civilians, and movements to impose greater surveillance on Western Muslim communities, which have already been disproportionately subjected to “national security” measures.

These are precisely the experiences that provide talking points for extremist groups that might otherwise be frustrated.

I interviewed a number of such Islamic extremists during full-immersion fieldwork in the Bangladeshi community of London’s East End and the Moroccan community of Southern Madrid. As part of this research, I also attended over a dozen Islamic extremists’ meetings.

In the East End, extremists from the transnational Islamist group, Hizb-Ut-Tahrir, competed directly against street gangs, schools, sport teams, and mosques for the attention of young Muslim men and women.

For a several weeks, I attended Hizb-Ut-Tahrir gatherings that took place directly upstairs from a government-sponsored youth club, where neighborhood adolescents went to do homework, play video games, or shoot billiards. Each Thursday after school at about 5:00pm, a Hizb-Ut-Tahrir activist went into the club downstairs to recruit attendees for their meeting upstairs. They dangled free snacks and soda, and about half of the young men would oblige.

Meetings were run like talk shows. A member would introduce a guest speaker and they would discuss issues pertaining to Islam and British public affairs. Questions came from planted members in the audience, and the young men would listen while chewing and checking their phones.

If it weren’t for grievances against the British state and society, these meetings would be more like Quranic study with halal fried chicken.

NYC Pro-Muslim Rally Marching On Sept. 11th, 2010. Photo by Viktor Nagornyy. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

NYC Pro-Muslim Rally Marching On Sept. 11th, 2010. Photo by Viktor Nagornyy. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.Instead, there was always much to discuss. In the last decade, the British government extended pre-charge detention periods for terrorism suspects, police imposed greater surveillance on Muslim groups, and various Islamophobic groups such as the English Defence League and the English National Alliance attacked mosques and Muslim citizens.

For overseas extremists, Europe and North America appear as a fortress. Advanced intelligence and passport control limit the migration of known extremists. And Western Muslims are largely integrated, law-abiding, content members of society. So it is difficult to find recruits or embed them.

Survey research shows that French Muslims are predominantly secular and far less religious than they are portrayed. A recent poll shows that British Muslims identify more closely as British than most non-Muslim Britons. American Muslims, in particular South Asians and Arabs, are among the United States’ most affluent, well educated minorities. And every year, new generations of immigrant-origin Muslims become more integrated into their societies in the West—adapting, intermarrying, having children and grandchildren.

Extremist organizations appeal to the fringes of these communities, and must seek out ways to advance their agenda and recruit supporters among the few inclined to listen to their ideology.

Terrorists attacks help, but not by triumphantly assaulting innocent people. Rather terrorism produces an anti-Muslim backlash that frustrates and alienates Muslims over time.

And this backlash creates a sense of betrayal and disappointment among second and third generation Western Muslims who believe they are not receiving the equal treatment and justice as the rest of their countrymen.

This backlash corners Western Muslims into a greater awareness of their Muslim-ness. They feel obligated to defend their vilified Muslim identity, when it represents but one facet of their personalities. Muslims are soccer stars and violinists, engineers and drama queens, rappers and politicians. But social scrutiny makes them one-dimensional in the public eye.

This backlash is gold for the Hizb-Ut-Tahrir activist who was previously grasping for something new to inspire the young people sitting in front of him, gnawing on halal fried chicken.

Islamophobia is inherently wrong. But if that is not persuasive enough, it is also an enormous strategic mistake in the struggle against Islamic extremism.

Image Credit: Je_suis_Charlie-18. Photo by Valentina Calà. CC by SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Oppress Muslims in the West. Extremists are counting on it. appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGender inequality in the labour market in the UKDoes the class come out of the person after the person comes out of the class?Martin Luther King, Jr. on courage, equality, and justice

Related StoriesGender inequality in the labour market in the UKDoes the class come out of the person after the person comes out of the class?Martin Luther King, Jr. on courage, equality, and justice

Gender inequality in the labour market in the UK

The analysis of gender inequality in labour market outcomes has received substantial attention from academics of various disciplines. The distinct literatures have explored, often from differing perspectives and approaches, the various forms of inequality women experience in the labour market. Moreover, the issues and challenges the increasing participation of women in paid work poses has resulted in a substantial interest by policy makers, in many areas of policy, including taxation and benefits, health, caring, the provision of early years’ services, school and higher education.

The gender employment rate gap decreased by almost 30 percentage points since 1971, when data started to be recorded in the Labour Force Survey (LFS). Educational attainment gaps have not only narrowed over recent decades but girls’ education has overtaken that of boys. However, the labour market outcomes of women, both the jobs they do and the pay they receive, often do not reflect their personal qualification levels, at least relative to men, nor their improvement in recent years. There remain gender differences in pay that cannot be explained by educational attainment or other relevant factors, a sign perhaps that the labour market is failing to make the best use of women’s talents. The reasons for this inefficiency are numerous and complex.

We know that labour market inequality between men and women start earlier than entry into the labour market; and that, although gender gaps might not be very prominent in the early labour market years, they widen later on, and particularly important is the impact of having children and the associated career break. For example, the very distribution of where women and men work in the economy, both in terms of sectors and occupations, may not only lead to gender inequality directly, but is also inexorably linked to the subject choices boys and girls make at school. We know that segmentation in the occupations men and women do is substantial, and explains a large and increasing proportion of the gender pay gap, but the inequality within occupations is much wider. Similarly, although the gender pay gap for those in full time work is about 20%, the pay gap between low and high paid women is substantially higher. Gender interacts with other factors to create substantial inequalities. Reasons also include inequality within the household, and the constraints and barriers that an unequal distribution of labour in household production generates on women’s likelihood of participating in paid work. The latter is also linked related to the fiscal policies as well as social attitudes.

One Pound by Richard Cawood. CC-BY-NC-2.0 via flickr.

One Pound by Richard Cawood. CC-BY-NC-2.0 via flickr.What does this all mean for policy? In devising policy approaches and solutions, I think it is important to start from where there seems to be at least some good degree of consensus on the evidence. In fact, despite differences arising from disciplinary backgrounds, philosophical and political perspectives and methodological approaches, it appears that we have some overlapping consensus amongst scholars that:

gender inequality in the labour market is the product of many factors, most notably of a structured system of institutions and norms in which gender plays a very important part. The issues are complex, manifold and interrelated;

within group inequality are very large, which means we need to look at the interaction between gender and other and characteristics;

gender inequality have an important life-cycle dimensions, starting at school, going on during the transition into the labour market and then motherhood.

These are of course only starting points for policy makers. However, they do lead to the following considerations. First, the complexity mentioned above might have meant that policy makers have aimed to tackle various issues with separate discrete policies, in many instances failing to see the links between the issues. I would argue instead that such complexity does not justify separate discrete policies but a more targeted approach on a limited number of key variables, about which deep knowledge of how they relate to others is essential. More specifically, this means less of a proliferation of separate, discrete interventions and more of a set of targeted interventions that aim to address the key labour market inequalities.

Secondly, I would argue that the evidence on within-group inequality, the interaction of various factors, combined with the way gender inequality in the labour market develops through the life cycle, all suggests for a policy approach that is more sensitive to individual circumstances, recognises the variations around averages and therefore focuses on targeted, individual support, moving away from aggregate targets (i.e. all women, all mothers, all school girls). This is certainly more difficult but I do think unavoidable if we want to ensure greater success towards gender equality.

The post Gender inequality in the labour market in the UK appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCareer horizons for womenThe economics behind detecting terror plotsMaking choices between policies and real lives

Related StoriesCareer horizons for womenThe economics behind detecting terror plotsMaking choices between policies and real lives

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers