Oxford University Press's Blog, page 707

January 28, 2015

The influence of economists on public policy

There’s a puzzle around economics. On the one hand, economists have the most policy influence of any group of social scientists. In the United States, for example, economics is the only social science that controls a major branch of government policy (through the Federal Reserve), or has an office in the White House (the Council of Economic Advisers). And though they don’t rank up there with lawyers, economists make a fairly strong showing among prime ministers and presidents, as well.

But as any economist will tell you, that doesn’t mean that policymakers commonly take their advice. There are lots of areas where economists broadly agree, but policymakers don’t seem to care. Economists have wide consensus on the need for carbon taxes, but that doesn’t make them an easier political sell. And on topics where there’s a wider range of economic opinions, like over minimum wages, it seems that every politician can find an economist to tell her exactly what she wants to hear.

So if policymakers don’t take economists’ advice, do they actually matter in public policy? Here, it’s useful to distinguish between two different types of influence: direct and indirect.

Direct influence is what we usually think of when we consider how experts might affect policy. A political leader turns to a prominent academic to help him craft new legislation. A president asks economic advisers which of two policy options is preferable. Or, in the case where the expert is herself the decisionmaker, she draws on her own deep knowledge to inform political choices.

This happens, but to a limited extent. Though politicians may listen to economists’ recommendations, their decisions are dominated by political concerns. They pay particular attention to advice that agrees with what they already want to do, and the rise of think tanks has made it even easier to find experts who support a preexisting position.

Research on experts suggests that direct advisory effects are more likely to occur under two conditions. The first is when a policy decision has already been defined as more technical than political—that experts are the appropriate group to be deciding. So we leave it to specialists to determine what inventions can be patented, or which drugs are safe for consumers, or (with occasional exceptions) how best to count the population. In countries with independent central banks, economists often control monetary policy in this way.

Experts can also have direct effects when possible solutions to a problem have not yet been defined. This can happen in crisis situations: think of policymakers desperately casting about for answers during the peak of the financial crisis. Or it can take place early in the policy process: consider economists being brought in at the beginning of an administration to inject new ideas into health care reform.

But though economists have some direct influence, their greatest policy effects may take place through less direct routes—by helping policymakers to think about the world in new ways.

For example, economists help create new forms of measurement and decision-making tools that change public debate. GDP is perhaps the most obvious of these. A hundred years ago, while politicians talked about economic issues, they did not talk about “the economy.” “The economy,” that focal point of so much of today’s chatter, only emerged when national income and product accounts were created in the mid-20th century. GDP changes have political, as well as economic, effects. There were military implications when China’s GDP overtook Japan’s; no doubt the political environment will change more when it surpasses the United States.

Money, by 401(K). CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

Money, by 401(K). CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.Less visible economic tools also shape political debate. When policymakers require cost-benefit analysis of new regulation, conversations change because the costs of regulation become much more visible, while unquantifiable effects may get lost in the debate. Indicators like GDP and methods like cost-benefit analysis are not solely the product of economists, but economists have been central in developing them and encouraging their use.

The spread of technical devices, though, is not the only way economics changes how we think about policy. The spread of an economic style of reasoning has been equally important.

Philosopher Ian Hacking has argued that the emergence of a statistical style of reasoning first made it possible to say that the population of New York on 1 January 1820 was 100,000. Similarly, an economic style of reasoning—a sort of Econ 101-thinking organized around basic concepts like incentives, efficiency, and opportunity costs—has changed the way policymakers think.

While economists might wish economic reasoning were more visible in government, over the past fifty years it has in fact become much more widespread. Organizations like the US Congressional Budget Office (and its equivalents elsewhere) are now formally responsible for quantifying policy tradeoffs. Less formally, other disciplines that train policymakers now include some element of economics. This includes master’s programs in public policy, organized loosely around microeconomics, and law, in which law and economics is an important subfield. These curricular developments have exposed more policymakers to basic economic reasoning.

The policy effects of an economic style of reasoning are harder to pinpoint than, for example, whether policymakers adopted an economist’s tax policy recommendation. But in the last few decades, new policy areas have been reconceptualized in economic terms. As a result, we now see education as an investment in human capital, science as a source of productivity-increasing technological innovations, and the environment as a collection of ecosystem services. This subtle shift in orientation has implications for what policies we consider, as well as our perception of their ultimate goals.

In the end, then, there is no puzzle. Economists do matter in public policy, even though policymakers, in fact, often ignore their advice. If we are interested in understanding how, though, we should pay attention to more than whether politicians take economists’ recommendations—we must also consider how their intellectual tools shape the very ways that policymakers, and all of us, think.

The post The influence of economists on public policy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe economics behind detecting terror plotsGender inequality in the labour market in the UKUnderstanding the local economic impacts of projects and policies

Related StoriesThe economics behind detecting terror plotsGender inequality in the labour market in the UKUnderstanding the local economic impacts of projects and policies

January 27, 2015

Their blood cries out to God

Not long after the beginning, Genesis tells us that there were two brothers. One killed the other. “And the Lord said, ‘What have you done? Listen; your brother’s blood is crying out to me from the ground’” (Gen. 4:10). This is the Lord’s response when the murderer denies knowing where his brother is and asks, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” We humans are our brothers’ and sisters’ keepers; and yet we have been disowning and killing each other since the beginning.

On this day seventy years ago, the last prisoners were liberated from Auschwitz. On this day today, we commit to remembering the more than six million Jews, Gypsies, homosexuals, and others who were rejected and murdered by their fellow humans. Their blood still cries out to God from the ground.

When we remember the Shoah, always but especially on this day, we must focus our energies on remembering those who we have lost. Those who murdered them dehumanized them. Let us defy that curse and celebrate their thoughts, beliefs, feelings, and experiences – the fullness of their humanity.

Let us sit in the memory of those who we have lost. Those of us without memories of our own must humbly seek welcome in the memories of others, to the extent that they are knowable. When we cannot know what the people who perished were like, let us grow in our awareness of our ignorance. We can never fully understand what we have lost. Let us mourn both what we know and what we know we cannot know.

The words of the victims themselves offer the clearest hope of seeing and remembering through their eyes, of knowing what the Shoah was and what it destroyed, even as it defies human comprehension. In 1947, writing from Sweden, poet, refugee, and future Nobel laureate Nelly Sachs offered words of caution to her fellow humans: “We the rescued beg you: Show us your sun slowly. Lead us step by step from star to star. Let us quietly learn to live again. Otherwise the song of a bird or the filling of a bucket at a well could unleash our ill-sealed ache and wash us away.”

There is beauty in the world. There is hope. There is joy to be found in the midst of the ordinary. But there is also great darkness within those around us and even, at times, within ourselves. We have killed our brothers and sisters since the beginning of humanity, it seems. We are each other’s keepers. We learn to keep each other in the present, in part, by keeping the memories alive of those who have gone before, especially of those who were the victims of immeasurable evil.

This remembering can be no mere intellectual exercise of memorizing facts and figures. As heirs of the memories of the victims, we must take their legacy personally. Some felt anger and indignation, a few even hate, but for many the overwhelming response was one of sorrow. Entire communities, villages, towns, families, clans, cultures, and sub-cultures that once thrived are now gone.

The Talmud teaches that “anyone who destroys a life is considered by Scripture to have destroyed an entire world” (Mishnah Sanhedrin 4:9). In the Shoah, more than six million worlds were wiped out. Let us mourn their loss. Let us seek to remember. Their blood still cries out to God. Let us listen.

Image Credit: Holocaust Remembrance Day. Photo by Brittney Bush Bollay. CC by NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Their blood cries out to God appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe lost stories of Muslims in the HolocaustThoughts in the necropolisHave we become what we hate?

Related StoriesThe lost stories of Muslims in the HolocaustThoughts in the necropolisHave we become what we hate?

Holocaust consciousness must not blind us

While nascent talk of the Holocaust was in the air when I was growing up in New York City, we did not learn about it in school, even in lessons about World War II or the waves of immigration to America’s shores. There were no public memorials or museums to the murdered millions, and the genocide of European Jewry was subsumed under talk of “the war.”

My father was a somber man who arrived here from Poland after the war and, like many survivors, kept to himself, trying his best to block out the past. Growing up, my connection to my father’s lost world consisted of names mentioned in hushed tones and photographs retrieved from hidden boxes.

But as I grew older, I watched with great interest, more than a little curiosity, and a good deal of relief as it became more acceptable to talk about “our” tragedy. By the 1980s, lessons about the genocide of European Jewry became de rigueur in high schools through the nation. In the following decade, people could flock to a hulking museum in our nation’s capital that told the story for all who cared to listen.

The Holocaust became a universal moral touchstone that called upon us to defend our common humanity against the capacity for evil. But today, on the eve of International Holocaust Remembrance Day on 27 January, the lesson we Jews seem to draw from our history is that those outside the tribe cannot be trusted.

In the wake of the recent terrorist attack on a kosher food store in Paris, and as anti-Semitism rises in France and elsewhere, these fears seem understandable. I know these kinds of fears well. Even in the relative comfort of his postwar existence, my father had a recurring nightmare that he was being chased by German shepherds.

But when such fears lead to catastrophic thinking, they harden our hearts to the suffering of others and contribute, paradoxically, to a sense of Holocaust fatigue among many Jewish Americans — particularly younger ones.

“I’m sick of the Holocaust as a shorthand for ‘we suffered more than you, so we should get the piece of cake with the rosette on it,’” a 20-something columnist wrote in the Forward. Peter Beinart in The Crisis of Zionism argues that the growing emphasis on the Holocaust in American life beginning in the 1960s and 1970s marked the end of Jewish universalism.

“Liberalism was out,” Beinart wrote. “Tribalism was in.”

Beinart and others are partly right: Holocaust trauma is too readily exploited. But historically, Holocaust commemoration efforts have been more than simply exercises in tribalism. They often emerged from an urge to acknowledge and alleviate human suffering writ large.

Raphael Lemkin, the Polish-Jewish legal scholar and Holocaust survivor who coined the term “genocide” and fought to have the concept recognized by the United Nations, exemplified this impulse. So did the mobilization of the Holocaust second generation. Descendants of survivors, empowered by the progressive movements of the 1960s and 1970s, coaxed our parents to share their stories. The Holocaust consciousness we helped build was part of a larger search for self-expression and human rights.

Today, many Holocaust commemoration activities reflect this universal spirit as well, including the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s efforts to promote awareness of genocide in Sudan and elsewhere. Jewish-American donors provided the bulk of the funds for a memorial to the more than two million Cambodians murdered during the brutal reign of the Khmer Rouge, an acknowledgement of a shared tragic history.

These and other efforts to remember the suffering of others should be applauded, but they must be more than window dressing. They should also spur our own collective soul-searching. Committing funds for projects in places where Jews have few political or emotional investments, such as Cambodia or Sudan, is relatively easy. Subjecting our own deeply felt loyalties to Israel to scrutiny is a much more difficult, but no less important, task.

The truth is that at times our privileges may in fact be implicated in the suffering of others in the Palestinian territories, where life is brutal and frequently too short. A sense of hopelessness prevails among both Israelis and Palestinians, fueling acts of desperation and violence in the Middle East and beyond.

A chorus of leaders on both sides is promoting a politics of fear, declaring I cannot be my brother’s keeper when my brother is out to murder me. But on this Holocaust Remembrance Day, let us honor the memory of the parents and grandparents, uncles and aunts, and all of the unknown others we have lost by resisting such talk and redoubling our efforts to seek peace.

A version of this article first appeared on New Jersey Jewish News.

Headline image credit: Ruins of barracks at Birkenau. Photo by Dennis Frank (WeEzE). CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Holocaust consciousness must not blind us appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe lost stories of Muslims in the HolocaustA brief history of Data Privacy Law in AsiaThe inspiration of Alice in Wonderland: 150 years on

Related StoriesThe lost stories of Muslims in the HolocaustA brief history of Data Privacy Law in AsiaThe inspiration of Alice in Wonderland: 150 years on

The lost stories of Muslims in the Holocaust

Even in this place one can survive, and therefore one must want to survive, to tell the story, to bear witness; and that to survive we must force ourselves to save at least the skeleton, the scaffolding, the form of civilization. We are slaves, deprived of every right, exposed to every insult, condemned to certain death, but we still possess one power, and we must defend it with all our strength for it is the last — the power to refuse our consent.

― Primo Levi, Survival in Auschwitz

On the 70th anniversary of the liberation of the German Nazi concentration and death camp at Auschwitz, I hope we can keep telling the stories of survival and miracles that the victims experienced. But never shall we forget the six million Jews that were murdered. There are many stories of the Shoah (Holocaust) that are told over and over again by survivors, witnesses, and children of survivors. Today, the tenuous relationship between Jews and Muslims around the world echoes negative sentiments and feelings about these two rich traditions. Anti-Semitism has been on the rise in Europe and unfortunately some of the weight of this tide rests on the shoulders of Muslim immigrants in Europe.

As an Islamic and Holocaust scholar, I was always saddened to witness such animosity and tension between the two traditions and decided to take another turn in the field of the Holocaust: Muslims and the Holocaust. I am a Muslim woman who teaches the Holocaust, Genocide, World Religions, and Islam; many questions are raised about my work and identity. Some scholars and community members view the two areas of study, Holocaust and Islam, in contradiction; they seem puzzled and at times, accuse me of being “divided.” They ask me: “How can you teach two unrelated fields? How can a Muslim teach the Holocaust? What kind of a scholar are you?” I am amused by these questions as I think of how much esoteric knowledge rests on dusty shelves, for I believe there is an important connection between my two areas of research.

Birkenau-Auschwitz Concentration Camp. Photo by Ron Porter. CC0 via Pixabay.

Birkenau-Auschwitz Concentration Camp. Photo by Ron Porter. CC0 via Pixabay.My work has steered me to confront my own Muslim community on the suffering of “others,” which I argue can become a bridge of mutual understanding and interreligious dialogue. How can we create interreligious dialogue and confront the suffering of one another at different historical moments? How can we discuss and sustain dialogue, which by its very nature also risks dehumanizing the “other”? What aspects about Islam and about the Holocaust might connect both Muslims and Jews? And in a greater sense, what does my work offer students, communities, and academia? These and other questions haunt me every day, knocking on my faith, my study of Holocaust memoirs, my study of new research on Muslims and Jews during the Holocaust and colonialism.

The lost stories of Muslim rescuers and the relationship between Jews and Muslims in Arab countries have been lost under the noise of media portrayal of these faiths being at war throughout time. Israel and Palestine seems to carve the relationship for the rest of us and I feel that we must change that for the future of Judaism and Islam. To tell the stories of positive cooperation between Jews and Muslims is crucial in my work. To reflect on the deep-rooted anti-Semitism and Islamophobia within each community is an important.

Teaching the Holocaust to young students with very little knowledge of the Holocaust or Islam has been challenging. I invite Holocaust survivors to visit our classes and they are stunned and shocked at the stories of survival and loss. The personal connection creates an intimate reaction within the classroom and that is why I embarked on the idea of interviewing survivors. Interviewing survivors as a Muslim was an uncomfortable experience because I did not know what to expect and neither did they. There is one man I will never forget for the rest of my life:

On February 27th, 2010, I looked into the sky-blue eyes of Albert Rosa, an 85-year-old Shoah survivor, for three hours as he spoke about his experience at Auschwitz-Birkenau. As I left him, he told me with tears in his eyes that he wanted someone to write his life story, since he had very little formal education and would not be able to express in writing his feelings on the Shoah. He asked me, “How can I express in words how I felt when my sister was bludgeoned to death in front of me by a Nazi woman, or when I saw my elder brother hanging from a rope when I had tried to defend him?” I looked into his eyes, which had pierced me all day, and wondered how I could tell his story in words without losing the sense of the emotional and physical strength it had taken him to survive the horror of his life in the camps. He spoke of maggots crawling on his body as he was ordered to move the dead Jewish bodies, the gold he stole from the teeth of the dead, the urine he saved to nurse the wounds inflicted by a German Shepherd, the plant roots that he dug out with his fingers for nourishment, the ashes he swallowed from the crematorium as he helped build Birkenau. How was I to give these events any life with mere words? These feelings of paralysis emerge as I write this testimony; how I can give the Shoah a life of its own without trespassing on politics, ethics, and the millions of victims? In some ways, I felt like abandoning this project because I feared that I could not do it justice. (Shoah through Muslim Eyes (Academic Studies Press, 2015))

Finally, I hope to take the testimonies of survivors, lost stories of Muslims during the Holocaust, and the memory of two traditions to a new level where one can speak up for one another.

The post The lost stories of Muslims in the Holocaust appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFour reasons for ISIS’s successSalamone Rossi as a Jew among GentilesThe myth-eaten corpse of Robert Burns

Related StoriesFour reasons for ISIS’s successSalamone Rossi as a Jew among GentilesThe myth-eaten corpse of Robert Burns

The inspiration of Alice in Wonderland: 150 years on

This Christmas, London’s Royal Opera House played host to Christopher Wheeldon’s critically acclaimed Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, performed by the Royal Ballet and with a score by Joby Talbot. Indeed, Lewis Carroll’s seminal work Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) has long inspired classical compositions, in forms as diverse as ballet, opera, chamber music, song, as well as, of course, film scores. Examples include English composer Liza Lehmann’s Nonsense songs (1908); American composer Irving Fine’s two sets of Choruses from Alice in Wonderland (1949 and 1953); and contemporary composer Wendy Hiscock’s ‘Jill in the box’, commissioned by the BFI to accompany the first footage of Alice in Wonderland – a 1903 silent film directed by Percy Stow and Cecil Hepworth.

In the Oxford catalogue, the influence of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland can be seen in choral pieces by Maurice Bailey, Bob Chilcott, and Sarah Quartel, and it is interesting to observe the similarities in their treatment of this famous text. Maurice Bailey selects seven poems from the book to produce a set of seven songs for upper voices and piano or instrumental ensemble. The set begins with a short narration—a direct quotation of the book’s first four paragraphs—and the first song takes up the image of Alice sitting by the riverbank, setting the scene with the performance direction ‘like a warm and lazy summer afternoon’. Each song has a distinct character:

‘Twinkle, twinkle, little bat!’ is jovial, with a gentle swing feel;

‘You are old, Father William’ is solemn and dramatic;

‘How doth the little crocodile’ is a peaceful, chorale-like setting;

‘Will you walk a little faster?’ has a deliberate feel, featuring call-and-response imitation;

‘Beautiful Soup’ is in the manner of a leisurely waltz; and

‘They told me you had been to her’ is mysterious and energetic, with evocative musical language.

In all the songs, the piano or instrumental ensemble is a key component in the drama, rather than being simply a supportive accompanying force. There is also some scat singing, recitation, and spoken text. ‘You are old, Father William’ in particular exploits recitation to great dramatic effect, requiring a member of the choir to take on the part of Father William, which is entirely spoken, while the rest of the choir adopt the role of narrator, with sung interjections that complete the story.

Chilcott’s Mouse Tales, for SA and piano, is in two movements: the second setting the familiar poem ‘The Mouse’s Tale’ from the published version of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland; and the first setting the poem that Carroll included in its place in his original manuscript. Both movements have an abundance of character, and Chilcott marks the first movement ‘sassy’, a term that perfectly describes the musical style and that encourages the singers to give a characterful performance. The first movement has a jazz flavour, while the energetic second movement features driving ostinatos in the piano and accents in the vocal lines that place emphasis on unexpected beats of the bar, keeping the singers on their toes. Like Bailey, Chilcott employs scat singing and spoken interjections such as ‘you did?’ and ‘nice!’ for dramatic effect, as well as a catchy refrain to present the well-known proverb ‘when the cat’s away, then the mice will play’.

Sarah Quartel. Devin Card Photography

Sarah Quartel. Devin Card PhotographyUnlike the other two composers, Sarah Quartel uses Carroll’s story as the basis for her own text, in which we encounter characters such as the White Rabbit, the Cheshire Cat, and the Hatter. The piece, for SSA and piano, has great potential for dramatic performance, with sections of a cappella scat singing and spoken text and a catchy refrain that centres around the Cheshire Cat’s declaration that ‘we’re all mad here’, where the part-writing encourages playful interaction between the different sections of the choir. The choir adopts the role of Alice, and Quartel helps the singers to convey Alice’s responses to the narrative through performance directions such as ‘with distinct character, telling a story’, ‘playful, like a caucus-race’, ‘indignant!’, and ‘with awe!’. Naturally, the music itself contributes to the characterization. For example, a march-like figure is employed to represent the Queen, while the music for the flustered White Rabbit features rapidly ascending and descending scales in the piano. Indeed, once again, the piano is a key component in the portrayal of the drama, and the rapid movement through different keys also helps to convey Alice’s mixture of confusion and wonder at the strange world she inhabits.

As we have seen, there are certain similarities in the three composers’ responses to this influential work of children’s literature. Perhaps unsurprisingly, each of the composers elected to write for upper voices, so that their settings might be performed by children’s choir. Imaginative and descriptive performance directions play an important part, assisting the singers in their characterization of the unusual protagonists in the story that they are telling. Again, unsurprisingly, the book appears to inspire a certain theatricality in the writing and music; it requires the performers to give a dramatic performance that has a strong sense of fun. Spoken text and scat singing are also prevalent in all three works, and the piano makes an integral contribution to the musical characterization. With its adventurous heroine, extraordinary characters, and unapologetic celebration of the quirky and the ‘mad’, it is little wonder that the text has proven a source of inspiration for composers since its inception and will undoubtedly continue to do so.

Headline image credit: Иллюстрация к главе Бег по кругу книги Алиса в стране чудес. Image by Gertrude Kay. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The inspiration of Alice in Wonderland: 150 years on appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe myth-eaten corpse of Robert BurnsOxford’s top 10 carols of 2014A composer’s thoughts on re-presentation and transformation

Related StoriesThe myth-eaten corpse of Robert BurnsOxford’s top 10 carols of 2014A composer’s thoughts on re-presentation and transformation

A brief history of Data Privacy Law in Asia

The OECD’s Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data (1980) were an early influence on the development of data privacy laws in Asia. Other bodies have since also been influential in the formulation of data privacy laws across Asia, including the 1981 Council of Europe Data Protection Convention, the United Nations Guidelines for the Regulation of Computer Data Files, the European Union’s Data Protection Directive, and the APEC Privacy Guidelines.

This timeline below shows the development of data privacy laws across numerous different Asian territories over the past 35 years. In each case it maps the year a data privacy law or equivalent was created, as well as providing some further information about each. It also maps the major guidelines and pieces of legislation from various global bodies, including those mentioned above.

Featured image credit: Data (scrabble), by justgrimes. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post A brief history of Data Privacy Law in Asia appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIs London the world’s legal capital?Parental consent, the EU, and children as “digital natives”Public health in 2014: a year in review

Related StoriesIs London the world’s legal capital?Parental consent, the EU, and children as “digital natives”Public health in 2014: a year in review

January 26, 2015

Is London the world’s legal capital?

2015 may be a watershed year for one part of the UK economy—the market for legal services.

Much is made of London’s status as the world’s legal capital. This has nothing to do with the legal issues that most people encounter, involving crime, wills, houses, or divorce. It concerns London’s pre-eminence in the resolution of international commercial disputes— those substantial business disputes, often involving foreign parties or contracts performed abroad, which might in principle be heard anywhere. That an English court is everyone’s court of choice in such cases has long been an article of faith, at least for English lawyers.

English law is often chosen as the law governing commercial contracts, even those having little or no connection with England, because it is valued for its certainty and commercial approach. So whether, say, a German company is liable for failing to perform a contract in Kazakhstan may depend on English rules. If English law is to be applied, however, it is perhaps obvious that this will be done best in the English courts. Those courts are also widely respected for their impartiality, for the quality of the judges, and for their experience in commercial matters. The quality and expertise of English lawyers, confirmed in a recent survey, and the availability of remedies unknown elsewhere, notably injunctions to prevent foreign proceedings and to freeze a defendant’s foreign assets, are also powerful attractions.

The assumption that London is the market leader in commercial disputes is also reflected in the numbers. Since 2008, when cases arising from the economic downturn began to emerge, more than 1,000 claims have been made each year in the London Commercial Court (housed in the state-of-the-art Rolls Building). But it is the nature of these cases, not the quantity, which is striking. 81% of those started in 2013 involved at least one foreign party, and 48% involved no party from the UK at all. The message is that the Court is not just a national court, but an international court favoured by litigants from around the world who could no doubt have taken their dispute elsewhere.

The effects of this dominance are significant. English law is recognized as setting the standard in resolving business disputes, and English judgments (and the work of English writers) are widely read around the world. The economic value of such disputes is also considerable, and the resolution of such cases is a major invisible export.

But London’s profile in resolving transnational disputes cannot be taken for granted. Even if the parties’ obligations are subject to English law, how their dispute is handled may not be. Whether a court can hear a case at all (the issue of jurisdiction) is in large part governed by EU law. Cases may ultimately be resolved not in London, but by the European Court in Luxembourg, under rules less flexible, and less commercially attuned, than the English courts have traditionally used. This matters because jurisdiction is at the heart of most commercial cases.

The threats to London’s prominence are also home-grown. The much prized certainty of English contract law has become less secure as the courts have toyed with requiring parties to comply not just with a contract’s terms but with an ill-defined duty of good faith. The courts have also become increasingly intolerant about failure to meet procedural deadlines, a hard thing to achieve in complex cases, which undermines (or may be seen to undermine) their traditionally flexible, common sense approach to litigation. They are also less willing to allow lengthy arguments about which country’s courts should hear a case, a particular issue when so many cases have little connection with England, which for the parties at least is usually the heart of their dispute. Most striking of all, the government has proposed charging premium fees for using the Commercial Court, significantly increasing the cost of litigation, partly to reflect concerns that the taxpayer should not be subsidising a court largely used by foreign litigants.

Some courts have sought to limit the fallout from this new approach, at least when it comes to contractual certainty, and managing cases inflexibly. There are also signs that the government has back-tracked on the controversial proposal to penalize commercial litigants with higher fees, given concerns that London’s dominance in the legal marketplace would suffer. But the genie is out of the bottle, and lawyers have become uneasy about official commitment to London’s role as a legal hub.

Such doubts, justified or not, are a dangerous thing in a competitive market, and London certainly faces increased competition from overseas courts. New commercial courts established in Dubai, Qatar and Singapore, generously funded by the state, may threaten London’s traditional dominance.

Neither the English courts nor Parliament can resolve the uncertainties of EU procedural law—short of leaving the EU altogether. But any damage done by making English law less certain, or by over-regulating civil disputes, or by exposing litigants to additional costs, is avoidable. Whether such self-inflicted injuries can be avoided and whether the English courts remain competitive depends, however, on making a choice—a choice for the courts and for politicians. Whether or not London is the world’s legal capital, do we want it to be?

The international standing of the English courts is unlikely to be featured in most people’s New Year’s resolutions. But for the courts and government perhaps it should.

Image Credit: Courts Closed. Photo by Chris Kealy. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Is London the world’s legal capital? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPublic health in 2014: a year in reviewThoughts in the necropolisHave we become what we hate?

Related StoriesPublic health in 2014: a year in reviewThoughts in the necropolisHave we become what we hate?

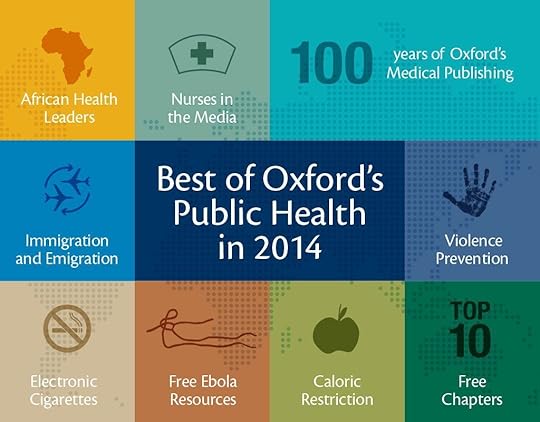

Public health in 2014: a year in review

Last year was an important year in the field of public health. In 2014, West Africa, particularly Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea, experienced the worst outbreak of the Ebola virus in history, and with devastating effects. Debates around e-cigarettes and vaping became central, as more research was published about their health implications. Conversations surrounding nutrition and the spread of disease through travel and migration continued in the media and among experts.

We’ve chosen a selection of articles that discuss public health issues that arose in 2014, their effects on the present and implications for the future.

Header image: US specialist helping Afghan nomads by Sfc. Larry Johns (US Army). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Public health in 2014: a year in review appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhich health messages work?Have we become what we hate?Working in the intensive care unit: an interview with Dr. Robert Stevens

Related StoriesWhich health messages work?Have we become what we hate?Working in the intensive care unit: an interview with Dr. Robert Stevens

Which health messages work?

Is it better to be positive or negative? Many of the most vivid public health appeals have been negative – “Smoking Kills” or “Drive, Drive, and Die” – but do these negative messages work when it comes to changing eating behavior?

Past literature reviews of positive- or gain-framed versus negative or loss-based health messages have been inconsistent. In our content analysis of 63 nutrition education studies, we discovered four key questions which can resolve these inconsistencies and help predict which type of health message will work best for a particular target audience. The more questions are answered with a “Yes,” the more a negative- or loss-based health message will be effective.

Is the target audience highly involved in this issue?The more knowledgeable or involved a target audience, the more strongly they’ll be motivated by a negative- or loss-based message. In contrast, those who are less involved may not believe the message or may simply wish to avoid bad news. Less involved consumers generally respond better to positive messages that provide a clear, actionable step that leaves them feeling positive and motivated. For instance, telling them to “eat more sweet potatoes to help your skin look younger” is more effective than telling them “your skin will age faster if you don’t eat sweet potatoes.” The former doesn’t require them to know why or to link sweet potatoes to Vitamin A.

Is the target audience detail-oriented?People who like details – such as most of the people designing public health messages – prefer negative- or loss-framed messages. They have a deeper understanding and knowledge base on which to elaborate on the message. In her coverage of the article for the Food Navigator, Elizabeth Crawford, noted that most of the general public is not interested in the details and is more influenced by the more superficial features of the message, including whether it is more positive or attractive relative to the other things vying for their attention at that moment.

Is the target audience risk averse?When a positive outcome is certain, gain-framed messages work best (“you’ll live 7 years longer if you are a healthy weight”). When a negative outcome is certain, loss-framed messages work best (“you’ll die 7 years earlier if you are obese”). For instance, we found that if it is believed that eating more fruits and vegetables leads to lower obesity, a positive message (“eat broccoli and live longer”) is more effective than a negative message.

Is the outcome uncertain?When claims appear factual and convincing, positive messages tend to work best. If a person believes that eating soy will extend their life by reducing their risk of heart disease, a positive message stating this is best. If they aren’t as convinced, a more effective message could be “people who don’t eat soy have a higher rate of heart disease.”

These findings show how those who design health messages, such as health care professionals, will be impacted by them differently than the general public. When writing a health message, rather than appealing to the sentiment of the experts, the message will be more effective if it’s presented positively. The general public is more likely to adopt the behavior being promoted if they see that there is a potential positive outcome. Evoking fear may seem like a good way to get your message across but this study shows that, in fact, the opposite is true—telling the public that a behavior will help them be healthier and happier is actually more effective.

Headline image credit: Newspaper. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Which health messages work? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHave we become what we hate?Building community and ecoliteracy through oral historyGait disturbances can help to predict dementia in older adults

Related StoriesHave we become what we hate?Building community and ecoliteracy through oral historyGait disturbances can help to predict dementia in older adults

Thoughts in the necropolis

One of Glasgow’s best-known tourist highlights is its Victorian Necropolis, a dramatic complex of Victorian funerary sculpture in all its grandeur and variety. Christian and pagan symbols, obelisks, urns, broken columns and overgrown mortuary chapels in classical, Gothic, and Byzantine styles convey the hope that those who are buried there—the great and the good of 19th century Glasgow—will not be forgotten.

But, of course, they are mostly forgotten and even the conspicuous consumption expressed in this extraordinary array of great and costly monuments has not been enough to keep their names alive. And, of course, we, the living, will soon enough go the same way: ‘As you are now, so once was I’, to recall a once-popular gravestone inscription.

Is this the last word on human life? Religion often claims to offer a different perspective on death since (it is said) the business of religion is not with time, but with eternity. But what, if anything, does this mean?

‘Eternal love’ and ‘eternal memory’ are phrases that spring to the lips of lovers and mourners. Even in secular France, some friends of the recently murdered journalists talked about the ‘immortality’ of their work. But surely that is just a way of talking, a way of expressing our especially high esteem for those described in these terms? And even when talk of eternity and immortality is meant seriously, what would a human life that had ‘put on immortality’ be like? Would it be recognizably human at all? As to God, can we really conceive of what it would be for God (or any other being) to somehow be above or outside of time? Isn’t time the condition for anything at all to be?

Entrance to the Necropolis. Photo by George Pattison. Used with permission.

Entrance to the Necropolis. Photo by George Pattison. Used with permission. If we really take seriously the way in which time pervades all our experiences, all our thinking, and (for that matter) the basic structures of the physical universe, won’t it follow that the religious appeal to eternity is really just a primitive attempt to ward off the spectre of transience, whilst declarations of eternal love and eternal memory are little more than gestures of feeble defiance and that if, in the end, there is anything truly ‘eternal’ it is eternal oblivion—annihilation?

Human beings have a strong track record when it comes to denying reality.

One fashionable book of the post-war period was dramatically entitled The Denial of Death and it argued that our entire civilization was built on the inevitably futile attempt to deny the ineluctable reality of death. But if there is nothing we can do about death, must we always think of time in negative terms—the old man with the hour-glass and scythe, so like the figure of the grim reaper?

And instead of thinking of eternity as somehow beyond or above time, might not time itself offer clues as to the presence of eternity, as in the experiences that mystics and meditators say report as being momentary experiences of eternity in, with, and under the conditions of time? But such experiences, valuable as they are to those who have them, remain marginal unless they can be brought into fruitful connection with the weave of past and future.

From the beginnings of philosophy, recollection has been valued as an important clue to finding the tracks of eternity in time, as in Augustine’s search for God in the treasure-house of memory. But the past can only ever give us so much (or so little) eternity.

A recent French philosopher has proposed that time cannot undo our having-been and that the fact that the unknown slave of ancient times or the forgotten victim of the Nazi death-camps really existed means that the tyrants have failed in their attempt to make them non-human. But this is a meagre consolation if we have no hope for the future and for the flourishing of all that is good and true in time to come. Really affirming the enduring value of human lives and loves therefore presupposes the possibility of hope.

One Jewish sage taught that ‘In remembering lies redemption; in forgetfulness lies exile’ but perhaps what we it is most important to remember is the possibility of hope itself and of going on saying ‘Yes’ to the common, shared reality of human life and of reconciling the multiple broken relationships that mortality leaves unresolved.

Pindar, an ancient poet of hope, wrote that ‘modesty befits mortals’ and if we cannot escape time (which we probably cannot), it is maybe time we have to thank for the possibility of hope and for visions of a better and more blessed life. And perhaps this is also the message that a contemporary graffiti-artist has added to one of the Necropolis’s more ruined monuments. ‘Life goes on’, either extreme cynicism or, perhaps, real hope.

Featured image credit: ‘Life goes on.’ Photo by George Pattison. Used with permission.

The post Thoughts in the necropolis appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesImmoral philosophyHave we become what we hate?Four reasons for ISIS’s success

Related StoriesImmoral philosophyHave we become what we hate?Four reasons for ISIS’s success

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers