Oxford University Press's Blog, page 704

February 5, 2015

Teen dating violence: myths vs. facts

Teen dating violence is a major public health concern, with about 1 in 10 teens experiencing physical violence or sexual coercion, and even higher rates of psychological abuse. Some progress toward awareness, prevention, and intervention with these youth has been made. Organizations like loveisrespect, Futures without Violence, and Break the Cycle have increased awareness and provided resources for teens. Congress too has joined the call to end dating abuse by dedicating the month of February to teen dating violence awareness and prevention. Unfortunately, we have far to go in raising awareness of this problem; 81% of parents believe that teen dating violence isn’t an issue. Additionally, teens aren’t seeking out the help being offered. In fact, less than 10% of teen victims report seeking help. These statistics are concerning.Kids are being abused, resources are available, but the link between the two is missing. Let’s take a step back and think like the kids. What follows are some myths about teen dating violence that may prevent youth from seeking help, or receiving help when they do reach out.

Myth: If a person stays in an abusive relationship, it must not really be that bad.

Fact: When things get bad, people leave, escape, or protect themselves. Right? Not always true. Almost 80% of girls who have been physically abused will continue to date their abusers. There are a variety of reasons why people stay. These include fear, emotional dependence, low self-esteem, feeling responsible, confusing jealousy and possessiveness with love, threats of more violence, or hope that the abuser will change. For teenagers, these reasons are compounded by peer pressure, a fear of getting in trouble with adults, and the potential loss of friends. We need to find ways to lessen the stigma and perceived consequences of asking for help among teens.

Myth: Teen dating violence is just arguing. It doesn’t have the same consequences/isn’t as dangerous as domestic violence in adult relationships.

Fact: First, teen dating violence isn’t just limited to arguing. It includes physical, sexual, and emotional/psychological abuse, and stalking — all of which are very real and can be very damaging. Emotional abuse and stalking can take place in person, electronically, via text, or online. Secondly, teen dating violence is just as dangerous and the impact is just as far reaching. Beyond the immediate impact of abuse, victimized teens are also at risk for serious health issues. Research shows that abused teens are more likely to use alcohol, tobacco, and cocaine, engage in unhealthy weight control behaviors and risky sexual behaviors, are more likely to become pregnant, and are more likely to seriously consider or attempt suicide. These are serious, long-term consequences that can negatively affect lifetime well-being.

Sadly, there is also an increase in indirect self-destructive behaviors. For example, after such an assault, it is not uncommon to see teenagers neglecting schoolwork, neglecting friends, neglecting family, and neglecting sports activities. It is also important to note, that a crucial line of defense is that of primary care medicine – whether it be pediatrics or OB/GYN. While these victims may not necessarily seek out mental health care, it is not uncommon for victims of such violence to see their pediatrician or their OB/GYN for what presents as a physical or medical dilemma, but what in truth is actually the psychological reaction to trauma. Oftentimes, these symptoms are indicative of increased levels of depression, alcohol and substance abuse, and post-traumatic stress.

Myth: Teen dating violence only occurs between boys and girls.

Fact: Violence can occur in any relationship. In fact, LGBTQ youth may be more likely to experience dating violence compared to heterosexual youth. These youth are at higher risk for being victimized and are experiencing the same types of violence as those in opposite-sex relationships, but are the least likely to tell anyone or seek help. Why is this? Along with the same reasons why people don’t leave heterosexual relationships, LGBTQ youth also have to worry about the threat and fear of being outed by their partner. Knowing this, interventions tailored specifically to the LGBTQ community should be developed. Once again, we need to help these youth feel safe enough to ask for help.

Myth: Only girls can be victims of dating violence.

Fact: The reality is that anyone can be a victim of dating violence. Research has shown that 2 out of 5 females and 1 out of 3 males report being victimized in a dating relationship. Additionally, males aren’t the only abusers. One study found that more girls (41%) than boys (29%) reported perpetrating at some point in their lives. The media typically shows male perpetrators, so what message do our teens receive about abusers? Will victimized boys feel like they can come forward if they think they’re the only ones?

So, what can we do? It’s obvious that we need to be educating kids at the most basic level. We can’t expect them to seek out help or use the resources provided if they’re too scared, too confused, or are unaware of what’s really happening to them. We need to challenge their beliefs about teen dating violence and provide resources designed specifically for teens involved in violent relationships. There are several promising school-based programs available, influencing attitudes, reducing bullying, and reducing teen dating violence. By educating our youth, we can empower them to be their own advocates, encouraging each other to seek help and stop the cycle of abuse.

Headline image credit: Skater. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Teen dating violence: myths vs. facts appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA timeline of the ReformationOur habitat: one more etymology brought “home”Reading on-screen versus on paper

Related StoriesA timeline of the ReformationOur habitat: one more etymology brought “home”Reading on-screen versus on paper

A timeline of the Reformation

The Reformation was a seismic event in history, whose consequences are still working themselves out in Europe and across the world. The protests against the marketing of indulgences staged by the German monk Martin Luther in 1517 belonged to a long-standing pattern of calls for internal reform and renewal in the Christian Church. But they rapidly took a radical and unexpected turn, engulfing first Germany and then Europe as a whole in furious arguments about how God’s will was to be discerned, and how humans were to be ‘saved’. However, these debates did not remain confined to a narrow sphere of theology. They came to reshape politics and international relations; social, cultural, and artistic developments; relations between the sexes; and the patterns and performances of everyday life.

Below we take a look at some of the key events that shaped the Reformation. In The Oxford Illustrated History of the Reformation Peter Marshall and a team of experts tell the story of how a multitude of rival groups and individuals, with or without the support of political power, strove after visions of ‘reform’.

The post A timeline of the Reformation appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA vision of New York City’s transit system, from 1940-1968 [slideshow]Announcing the Oxford World’s Classics Reading GroupWorld Religion Day 2015

Related StoriesA vision of New York City’s transit system, from 1940-1968 [slideshow]Announcing the Oxford World’s Classics Reading GroupWorld Religion Day 2015

February 4, 2015

Our habitat: one more etymology brought “home”

When it comes to origins, we know as little about the word home as about the word house. Distinguished American linguist Winfred P. Lehmann noted that no Indo-European terminology for even small settlements has been preserved in Germanic. Here an important distinction should be made. Etymologists have spent centuries searching for the ancient roots that spawned the vocabulary of our old and modern languages. To be sure, the reconstructed roots of the ancient Indo-Europeans never floated independently of whole nouns and verbs; they are only the common part of the words that according to our theories are related, but the established relations are probably real. Fierce debates about minutiae only show that modern scholars don’t know how to deal with the embarrassment of riches; yet one of the variants they have proposed may be correct—no small achievement. This is where Lehmann’s conclusion comes in. Let us suppose that the ancient root of the word house meant “to hide” (this is an example from the previous post). There were many non-Germanic words having this root, but none of them meant “house.” Although the requisite stock in trade was present, different languages produced different words from it.

Here is a short list that illustrates Lehmann’s point: burg, thorp (its German cognate Dorf “village” has much greater currency than Engl. thorp), yard, and the nouns that interest us most of all: house and home. One example to make the situation clear will suffice. Let us agree for the sake of argument that thorp is akin to a Hittite verb meaning “to collect.” If so, thorp was coined to designate a collection of houses. This makes good sense (regardless of whether the etymology is correct or wrong), but outside Germanic no word related to thorp means “village.” The development is local.

Haims, the Gothic noun allied to Engl. home, occurs in the texts twice. From Gothic, as noted in this blog many times, parts of a fourth-century translation of the New Testament have come down to us. Gothic is a Germanic language. Haims glossed two Greek nouns for “village” (as opposed to “town”). This makes the idea of what the Goths called home quite clear. Modern German Heimat means “homeland, native land.” No less instructive is Old Icelandic heimr “world,” though it could refer to a more narrow space. Old Engl. ham (with long a, as in Modern Engl. spa) also denoted a village, an estate, and only sometimes a house. The progression was evidently from “abode” to “one’s native place.” Perhaps the most general senses of home have been retained in two Gothic adjectives with prefixes: ana-haims “present,” that is, “at home” and af-haims “absent,” that is, “not at home” (each has been recorded only once and only in the plural). Dutch has a close analog: inheems “native, homebred” and uitheems “foreign” (heem “home”).

Home, Sweet Home

Home, Sweet Home We can also remember the convoluted history of hamlet “small village” (no connection with Shakespeare’s hero). Old English had the noun hamm “a piece of pasture land; enclosure; house.” The Middle Low [= northern] German cognate of this word, with a diminutive suffix, made its way into French and returned to English with -et, a French diminutive suffix. (However, Modern French hameu does without any suffix!) The etymology of hamm is disputed, and one can sometimes read that it has been confused with ham, the word known from place names like Nottingham and Birmingham (the same in German: Mannheim, etc.) Allegedly, hamm is akin to hem “edge.” I have always thought that hamm had nothing to do with hem. The word, I believed, referred to a place smaller than a “ham”; to emphasize the difference, speakers shortened the vowel. Serious linguists treat such guesses with disdain, and I would not have dared to mention mine even for the purpose of self-immolation, but for a partial support of Skeat. He indulged in none of my semiotic fantasies, but he also wrote that ham and hamm are related. He was a man of rare common sense. Be that as it may, wherever we look, “home” returns us to a village or a piece of pastured land, apparently owned by a village community.

Today the words of the song “Home, Sweet Home” and “There is no place like home” epitomize the idea of home quite well, though clearly the beginning was less poetic. Yet one’s home, even if not “a castle,” is indeed “sweet,” and it may be that the idea of the “sweet” comfort associated with one’s dwelling is not recent. It has been suggested that home is allied to Irish cóim “pleasing; pleasant.” This connection is often ignored, but I have never seen it refuted. To repeat, “the place owned by the community; village; settlement” preceded the idea of satisfaction of communal living, but home was as dear to its inhabitants long ago as it is dear to us. Not a parallel but an instructive case is the Slavic word that means both “world” and “peace.” If we remember that Icelandic heimr means “world,” we will understand that, contrary to the dream of privacy in today’s overpopulated, overcrowded world, in the past being together, in a place open to the members of the community and to no one else, was the source of peace and pleasure.

In the post on house, I made much of the fact that hus was neuter. The word for “home” was feminine, but it showed a rare irregularity. In Gothic, haims belonged to one declension in the singular and to another in the plural. This oddity has a close analog in Greek, and it has often been commented upon but never explained. Perhaps the true etymology of home will be revealed only when we account for that irregularity and realize that the speakers of Old Germanic looked on one home and a multitude of homes as different entities. The branch of linguistics that deals with such phenomena is called grammatical stylistics. For comparison’s sake I can add that the etymology of wife remained hidden so long because researchers did not begin by asking the main question: How could a word meaning “woman” be neuter?

Two homeless children accused of having eaten their parents out of house and home.

Two homeless children accused of having eaten their parents out of house and home. The old Indo-European root of home remains, as usual, a matter of dispute. At one time, Gothic haims was compared with a verb for “live” (compare the English verb while, as into while away the time). Although phonetically and semantically not implausible, today this etymology has no advocates. Most dictionaries state that haims is a cognate of Greek kóme “village” and reconstruct the root with the sense “to lie, to be situated.” (Other cognates of kóme are Latin civis “citizen” and Russian sem’ia “family,” the latter sounds similar elsewhere in Slavic.) However, the path from “lie” to “settlement” is far from obvious. Besides, for kóme to match haims, its o should have gone back to oi, and the possibility of this change has been challenged with seemingly good reason. Still other scholars consider the relationship between the word for “home” and Engl. hem “edge.” This idea is already familiar to us, though we looked at it from a different perspective. I’ll pass over some fanciful suggestions, even when they have eminent proponents. Hunting for Indo-European roots resembles chasing the rainbow: the shining arch exists but remains out of reach. Let us rather remember the main things: home is a local Germanic coinage (whether it has an ancient Indo-European root is interesting but not very important), speaking about one home and about many homes was marked in a non-trivial way, and on Germanic soil home probably had positive connotations already in the remote past.

Image credits: (1) Cover of sheet music for “Home! Sweet Home!” words by H.R. Bishop [and John Howard Payne], music by H.R. Bishop, Chicago: McKinley Music Co., c. 1914. Project Gutenberg. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Hänsel und Gretel (um 1940), Johann-Mithlinger-Siedlung, Raxstraße 7-27, Wien-Favoriten. Image by Buchhändler (2010). CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Our habitat: one more etymology brought “home” appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMonthly gleanings for January 2015Our habitat: houseMonthly gleanings for December 2014, Part 2

Related StoriesMonthly gleanings for January 2015Our habitat: houseMonthly gleanings for December 2014, Part 2

Reading on-screen versus on paper

If you received a book over the holidays, was it digital or printed on paper? E-books (and devices on which to read them) are multiplying like rabbits, as are the numbers of eReading devotees. It’s easy to assume, particularly in the United States, with the highest level of e-book sales worldwide, that the only way this trend can go is up.

Yes, there was triple-digit e-book growth in 2009, 2010, and 2011, though by 2014 those figures had settled down into the single digits. What’s more, when you query people about their reading habits, you find that wholesale replacement of paper with pixels will be no slam-dunk.

Over the past few years, my colleagues and I have been surveying university students in a variety of countries about their experiences when reading in both formats. Coupling these findings with other published data, a nuanced picture begins to emerge of what we like and dislike about hard copy versus digital media. Here are five facts, fictions, and places where the jury is still out when it comes to reading on-screen or on paper.

Cost is a major factor in choosing between print or the digital version of a book.True.

College students are highly cost-conscious when acquiring books. Because e-versions are generally less expensive than print counterparts, students are increasingly interested in digital options of class texts if making a purchase. (To save even more, many students are renting rather than buying.)

Yet when you remove price from the equation, the choice is generally print. My survey question was: If the price were identical, would you prefer to read in print or digitally? Over 75% of students in my samples from the United States, Japan, Germany, and Slovakia preferred print, both for school work and when reading for pleasure. (In Germany, the numbers were a whopping 94% for school reading and 90% for leisure.)

The “container” for written words is irrelevant.False.

There’s a lot of talk these days about “content” versus “container” when it comes to reading. Many say that what matters in the end is the words, not the medium through which they are presented. The argument goes back at least to the mid-eighteenth century, when Philip Dormer, the Earl of Chesterfield, advised his son:

Due attention to the inside of books, and due contempt for the outside is the proper relation between a man of sense and his books.

When I began researching the reading habits of young adults, I assumed these mobile-phone-toting, Facebooking, tweeting millennials would be largely indifferent to the look and feel of traditional books.

I was wrong. In response to the question of what students liked most about reading in hard copy, there was an outpouring of comments about the physical characteristics of printed books. Many spoke about the aesthetics of turning real pages. One said he enjoyed the feel of tooled Moroccan leather. They enthused about the smell of books. In fact, 10% of all Slovakian responses involved scent.

E-books are better for the environment than print.Unclear.

Debate continues over whether going digital is the clear environmental choice. Yes, you can eliminate the resources involved in paper manufacturing and book transport. But producing – and recycling – digital devices, along with running massive servers, come with their own steep costs. The minerals needs for our electronic reading devices include rare metals such as columbite-tantalite, generally mined in African conflict-filled areas, where profits often support warlords. Recycling to extract those precious metals is mostly done in poor countries, where workers (often children) are exposed to enormous health risks from toxins. The serried ranks of servers that bring us data use incredible amounts of electricity, generate vast quantities of heat, and need both backup generators and cooling fans.

Today’s young adults are passionate about saving the environment. They commonly assume that relying less on paper and more on digits makes them better custodians of the earth. When asked what they liked most about reading on-screen – or least about reading in hard copy – I heard an earful about saving (rather than wasting) paper. Despite their conservationist hearts, internal conflict sometimes peeped through regarding what they assumed was best for the environment and the way they preferred to read. As one student wrote,

I can’t bring myself to print out online material simply for environmental considerations. However, I highly, highly prefer things in hard copy.

Users are satisfied with the quality of digital screens.False.

Manufacturers of e-readers, tablets, and mobile phones continue to improve the quality of their screens. Compared with devices available even a few years ago, readability has improved markedly. However, for university students who often spend long hours reading, digital screens (at least the ones they have access to) remain a problem. When asked what they liked least about reading on-screen, there was an outpouring of complaints in my surveys about eyestrain and headaches. Depending upon the country, between one-third and almost two-thirds of the objections to reading on-screen involved vision issues.

It’s harder to concentrate when reading on a screen than when reading on paper.True – by a landslide.

My question was: On what reading platform (hard copy, computer, tablet, e-reader, or mobile phone) did young adults find it easiest to concentrate? “Hard copy” was the choice of 92% (or more) of the students in the four countries I surveyed. Not surprisingly, across the board, respondents were two-to-three times as likely to be multitasking while reading on a digital screen as when reading printed text. It goes without saying that multitasking is hardly a recipe for concentrating.

How does concentration relate to reading? There are different ways in which we can read: scanning a text for a specific piece of information, skimming the pages to get the gist of what is said, or careful reading. The first two approaches don’t necessarily require strong concentration, and computer-based technologies are tailor-made for both. We search for specific keywords, often using the ‘Find’ function to cut to the chase. We jump from one webpage to the next, barely reading more than a few sentences. When we wander off from these tasks to post a status update on Facebook or check an airfare on Kayak, it’s not that hard to get back on track.

What computer technology wasn’t designed for is deep reading: thoughtfully working through a text, pausing to reflect on what we’re read, going back to early passages, and perhaps writing notes in the margins about our own take on the material. Here is where print technology wins.

At least for now, university students strongly agree.

Headline image credit: Books. Urval av de böcker som har vunnit Nordiska rådets litteraturpris under de 50 år som priset funnits by Johannes Jansson/norden.org. CC-BY-2.5-dk via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Reading on-screen versus on paper appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRevising the expectations argumentA vision of New York City’s transit system, from 1940-1968 [slideshow]Announcing the Oxford World’s Classics Reading Group

Related StoriesRevising the expectations argumentA vision of New York City’s transit system, from 1940-1968 [slideshow]Announcing the Oxford World’s Classics Reading Group

Freedom of the press and global jihad

Since the attacks on Charlie Hebdo on 7 January, the saying (wrongly attributed to Voltaire), “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it,” has become a motto against radicalism. Unfortunately, this virtuous defense of freedom of speech is not only inefficient but is backfiring, as demonstrated by protests in Muslim countries against the latest issue of Charlie Hebdo, which was released in the aftermath of the attacks.

The challenge of global jihad in Europe is broader and is the result of the lack of symbolic integration of Islam within liberal democracies, as well as the preeminence of a global theology of intolerance which Al Qaida and ISIS have used to build their political ideology.

First, symbolic integration of Islam is different from socio-political integration of Muslims. European politicians have addressed the former through different educational and socio-economic policies, without paying attention to the latter, which refers to the recognition of Islam as part of the respective national culture and history of European countries. This lack of symbolic integration has translated into increasing discriminatory policies vis-à-vis a number of religious practices, from the use of the hijab and the building of mosque minarets, to circumcision and halal food, all deemed “illiberal” and “uncivic.” This discrimination leads a lot of Muslims, even the secular ones, to think that they are not accepted as full members of European societies. This amplifies anti-Islamic discourse, which is no longer the monopoly of extreme right wing movements, but comes to be shared by all political actors from the right to the left.

Islam is presented as an external religion that threatens the core liberties of European democracies and therefore needs to be limited or circumvented. At the same time, since World War II, most European democracies have limited freedom of speech and press when it propagates racial hatred and negation of the Holocaust. That is why, since the Danish cartoons controversy of 2006, some Muslims have argued they should be protected by these same laws, drawing a line between legitimate critique and insult.

Pilgrimage site, Masjidul Haraam, Makkah. Photo by Menj. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

Pilgrimage site, Masjidul Haraam, Makkah. Photo by Menj. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr. Although the distinction can be blurry, Charlie Hebdo satires have not always been funny critiques but blatant insults to the basic creeds of Muslims. This incapacity to differentiate between critique and insult has been played out by radical groups like Al Qaida and ISIS, both of whom seek to recruit members from Western democracies. Both justify global jihad for the sake of Islam, which must be saved from the decadent western enemy. Because this “us versus them” mentality is very accessible to young Muslims everywhere, through the internet and other social media, it is no surprise that this rhetoric resonates with their daily experience in European societies and therefore make some of them easy recruits for global jihad.

In this regard, the preeminence of Salafi-jihadi discourses, which have monopolized the debate on “true” Islam, not only among Muslims but also in the eyes of the general population across Europe, reinforces the antinomy between the West and Islam. This discourse operates on the conceptualization of the “West” as a threat to Islam, not only through military means, but most importantly through attacks on Islamic creeds and practices.

As an inverted image, “Islam” in the eyes of most Europeans is perceived exactly in the same terms: a religion that is a threat to western values. In this sense, the clash is not between civilizations but between negative, inverted perceptions of Islam and Muslims. It will require courage on the part of European politicians, media, and public intellectuals to address Islam as a legitimate part of national communities in order to diminish the sense of alienation that can make some Muslims more vulnerable to the strategy of Al Qaida or ISIS.

The second reason why freedom of the press is irrelevant in the fight against global jihad is the powerful presence of the Salafi version of Islam in the religious market of ideas. This is problematic because, even as most Muslims in the West are not Salafis and the majority of Salafis are not jihadists, groups like Al Qaida and ISIS have a Salafi background. It means that their theological view comes from a particular interpretation of Islam rooted in Wahhabism, an eighteenth-century doctrine adopted by the Saudi kingdom.

“The clash is not between civilizations, but between negative, inverted perceptions of Islam and Muslims.”

In the West, Salafis incite people to withdraw from mainstream society, which is depicted as impure, in order to live by strict rules. These reactionary interpretations do contain similarities with jihadist discourse. So even if Salafism is, in itself, no root cause of radicalization into violence, it serves as the religious framework of radical groups such as ISIS. While there is no doubt that the majority of Muslims do not follow this radical strategy, it is difficult to demystify this theology of intolerance from a traditional Islamic perspective.

In other words, there is an urgent need for Muslim clerics everywhere to systematically overpower the influence of politicized interpretations of Islam, whether through employing the Internet, social media, or other educational tools.

Addressing the need for the symbolic integration of Islam, as well as the global revival of the Islamic tradition, requires Muslim leaders, secular politicians, and lay citizens to share responsibility and common action to overcome the “us versus them” mentality which is at the foundation of all extremism.

Regretfully, the political and religious consensus that dominated the demonstrations against terror in France could have been a symbolic first step in this direction, but is rapidly dissipating.

Image Credit: “Islam.” Photo by Firas. CC by NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Freedom of the press and global jihad appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFour reasons for ISIS’s successAn estate tax increase some Republicans might supportTrains of thought: Bob

Related StoriesFour reasons for ISIS’s successAn estate tax increase some Republicans might supportTrains of thought: Bob

Quantitative easing comes to Europe

Last month, the European Central Bank (ECB) announced its plans to commence a €60 billion (nearly $70 billion) of quantitative easing (QE) through September 2016. In doing so, it is following in the footsteps of American, British, and Japanese central banks all of which have undertaken QE in recent years. Given the ECB’s actions, now is a good time to review quantitative easing. What is it? Why has the ECB decided to adopt this policy now? And what are the likely consequences for Europe and the wider world?

What is quantitative easing (QE)?Under normal circumstances, central banks undertake monetary policy via open market operations. This typically involves buying (or selling) securities in a short-term money market to lower (or raise) the interest rate prevailing in that market. Central banks are well equipped to do this. They have large inventories of securities that they can easily sell in order withdraw money from the market and push interest rate up. They also have a monopoly on the creation of their particular currency, which they can use to buy securities and push the interest rate down. Open market purchases and sales usually only last for a day or two (through repurchase agreements, or repos), but can be repeated as often as necessary and adjusted in size to achieve the targeted rate.

For an economy that is mired in recession, open market purchases can be a good policy move: buying securities lowers short-term interest rates and increases the money supply. In time, such expansionary monetary policy can also reduce longer-term interest rates, which may stimulate spending on new houses, factories, and equipment, since such investment spending is often made with borrowed money. Expansionary monetary policy will also lead to a decline in the value of the domestic currency on international markets (i.e., depreciation), which will help domestic exports. Too much sustained monetary expansion can lead to inflation, which is one of the main risks of this policy.

In the current economic climate, however, short-term interest rates are already hovering around zero. Although some central banks have flirted with the idea of negative interest rates, there is not much room for conventional expansionary monetary policy to do much good.

Enter quantitative easing. Using quantitative easing, central banks purchase longer-term securities and, unlike open market operations, the purchases are usually permanent instead of for just a few days. This lowers longer-term interest rates. Since individuals and firms that borrow money to invest in homes, factories, and equipment generally do not finance these long-loved assets with overnight borrowing (for mortgages, 15- and 30-year terms are more typical), lowering longer-term interest rates may be a good way to stimulate such long-term investment.

Mario Draghi, President of the ECB, World Economic Forum 2013. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Why now?

Mario Draghi, President of the ECB, World Economic Forum 2013. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Why now? The European economy is listless. GDP appears to have grown—just barely—during the year just finished. Although 2014’s performance was an improvement over 2013’s decline in GDP, the EU’s growth forecasts for 2015 and 2016 are far from rosy. The job market is sluggish: EU-wide unemployment was 11.6% in 2014, down slightly from 12.0% in 2013. And a pick-up in inflation, which should accompany growth, was absent in 2014: the authorities have set a 2.0% for inflation; instead prices rose by an anemic 0.4% in 2014. Several countries have made progress toward much-needed structural reform; however, it is not clear that such reforms alone will get the European economy out of the doldrums anytime soon.

Other dangers facing the European economy also argue in favor of quantitative easing. To the east, tensions with Russia could flare at any time. The terrorist attacks in France have given a boost to right-wing parties throughout Europe, another threat to stability. And the election victory of the anti-austerity Syriza party in Greece, suggests that relations between Greece and the EU are about to get rockier.

What are the consequences?Quantitative easing will strengthen Europe’s wobbly recovery. The announcement quickly lifted European stock markets—the Euro Stoxx 50-share index rose 1.6% on the news. Lower longer-term interest rates should encourage more borrowing and investment spending. And QE will lead to a continued depreciation in the value of the euro, already at a decade-low against the US dollar, which will make European exports more competitive in world markets. The results will not be so pleasant for American exports, since the euro’s depreciation will cut into recent American export growth, which has benefitted from three rounds of American QE, the last of which ended a few months ago.

Quantitative easing will not sit well with all Euro-zone countries. Germany, which is economically far more robust than its European partners, is not a fan of QE. Memories of a destructive hyperinflation in the 1920s still linger in the national consciousness, lead Germans to be far more skeptical of a potentially inflationary policy that they see as bailing out their more profligate neighbors at their expense.

Finally, the European Central Bank has not said exactly which bonds it will buy. When the US Federal Reserve undertook QE, it had a wide variety of Treasury securities to purchase. Given the high credit-worthiness of the US government and the fact that the market for US Treasury securities is the most liquid market in the world, it was not difficult to find suitable securities to purchase. Will the ECB buy the debt of the fiscally weak euro-zone nations and put their balance sheet at risk? Or will it restrict its purchases to only the most credit worthy countries and risk the ire of the citizens from less well-heeled nations?

Despite these legitimate concerns, Europe’s weak economic performance requires bold action. Quantitative easing is an important step in the right direction.

Featured image credit: Growing Euros, by Images_of_money. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Quantitative easing comes to Europe appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRevising the expectations argumentThe influence of economists on public policyA different kind of swindle

Related StoriesRevising the expectations argumentThe influence of economists on public policyA different kind of swindle

February 3, 2015

Revising the expectations argument

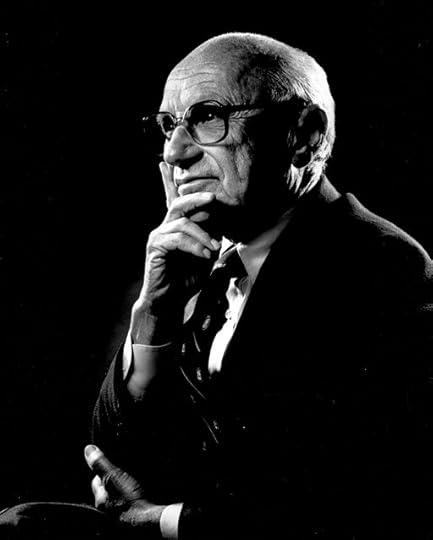

The way most economists organize their ideas about the development of macroeconomics says that 1968 was a crucial year in the demise of old-fashioned Keynesianism. That was the year of the publication of Milton Friedman’s Presidential Address for the American Economic Association. Friedman argued that if policymakers caused a bit of inflation, this would temporarily reduce unemployment, but the effect would only be temporary, so that in due course, unemployment would return to its previous level and the inflation would remain. The reason he gave was that wage-bargainers’ expectations would adjust to the occurrence of inflation, they would incorporate their expectations into their bargain, and inflation would consequently lose its beneficial effect.

I am always surprised anyone believes that. The argument itself amounts to saying that expectations adjust to reality. Well, yes. But how could it be that economists did not know that until 1968?

That, though, is only the beginning, because Friedman’s supposed innovation is the beginning of a story about a whole revolution of thought in macroeconomics. Supposedly, up to 1968, policymakers had believed that a policy of inflation would be effective in lowering unemployment – an idea often labelled ‘the Phillips curve trade-off.’ After 1968, apparently, they had to rethink this.

That again, supposedly, led to a great debate at the end of the 1960s and into the 1970s about whether Friedman was right. In due course, says the story, with inflation seeming to rise ever higher, Friedman’s side was seen to have won that debate. This was a great intellectual victory of ‘monetarism’ and a defeat for ‘Keynesianism’. All these things can easily be found in undergraduate textbooks of macroeconomics, and make pretty frequent appearances in bulletins of central banks as well.

Portrait of Milton Friedman, The Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice. Photo via RobertHannah89. CC0 1.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of Milton Friedman, The Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice. Photo via RobertHannah89. CC0 1.0 via Wikimedia Commons It sounds like an important story, and makes Friedman’s Address a key moment in the history of economics. But it sounds like an unlikely story as well. Not only did no one think of expectations adjusting until 1968, but when it was suggested, apparently they denied it. What else was that great debate about?

There is an interesting resolution. The argument Friedman made was very old news in 1968. Everyone already knew it. There a number of earlier statements, plenty of them by prominent authors in highly visible places. Moreover, Friedman’s own statement gave it no fanfare at all; he stated it just as if it were a well known argument. But more than that, Friedman himself had already made the argument on four previous occasions, the first of them a decade before the supposedly crucial lecture.

People write that Edmund Phelps had the same argument in print before Friedman. But that was in 1967, so it hardly makes a difference. There are two much more interesting things than that though. One is that Phelps did not even use the argument – as Friedman did – to say that inflationary policy was a bad idea. He was just using it – mathematical-economics-style – to work out how quickly inflation should gradually be raised to bring the biggest benefit. But the other interesting thing is this: he even said the argument was not original, naming some of those who had made it before. For some reason, that fact has made no impact at all on all the authors who quote him as joint-originator of the argument.

The fact that the Friedman/Phelps argument was so well-known is the first clue that the rest of the story about the Phillips curve is all wrong as well. The idea that policymakers thought that a policy of inflation would reduce unemployment is a long way from the truth. The idea that there was any argument about whether expectations would adjust to reality has almost nothing going for it – of course they do. On the other hand, there were arguments that the association of slow inflation with lower unemployment had nothing to do with mistaken expectations, but rather everything to do with overcoming various sorts of frictions. The same thing is widely believed today, so it was certainly not the subject of any revolution started by Friedman. The debate in the 1970s was about other, much more interesting matters entirely.

Not only have we all been teaching a story about the Phillips curve which just is not true, but we have been teaching one which makes economists look very foolish as well. It is a strange thing what a bit of actual reading of old arguments in economics can turn up.

Headline image: Saturn envy by woodleywonderworks. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr

The post Revising the expectations argument appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA vision of New York City’s transit system, from 1940-1968 [slideshow]Announcing the Oxford World’s Classics Reading GroupAn estate tax increase some Republicans might support

Related StoriesA vision of New York City’s transit system, from 1940-1968 [slideshow]Announcing the Oxford World’s Classics Reading GroupAn estate tax increase some Republicans might support

A vision of New York City’s transit system, from 1940-1968 [slideshow]

Streetcars “are as dead as sailing ships,” said Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia in a radio speech, two days before Madison Avenue’s streetcars yielded to buses. Throughout history, New York City’s mayors have devoted much time and energy to making the transit system as efficient as possible, and able to sustain the City’s growing population. The history of New York’s transit system is a mix of well-remembered, partially forgotten, and totally obscure happenings that illustrate the grit, chaos, and emotion of the five boroughs at different points in history.

The images in this slideshow look at New York transit between 1940 and 1968 — a pivotal period when technology was developing rapidly and the City was seeing intense growth. They are taken from Andrew J. Sparberg’s book From a Nickel to a Token: The Journey from Board of Transportation to MTA.

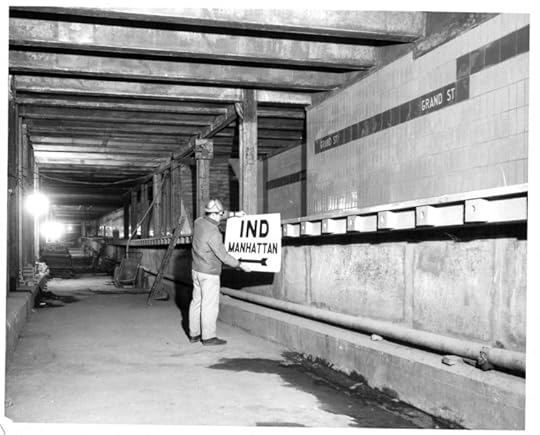

Chrystie Street connection opens, 1967

Chrystie Street connection opens, 1967 In November 1967, work was completed on a significant new subway under Chrystie Street on the Lower East Side. Above, work proceeds on the new Grand Street Station, a part of the project. Photo credit: New York Transit Museum.

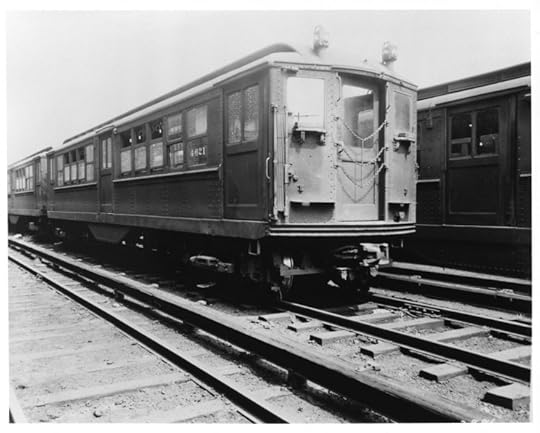

A BMT car in 1940

A BMT car in 1940 In June 1940, New York City’s government purchased two privately owned subway companies, one of which was the Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit Corp. (BMT). Photo credit: New York Transit Museum.

An IRT car in 1940

An IRT car in 1940 The other subway company purchased by the city in 1940 was the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT). BMT and IRT were unified with the Independent Subway System to form one giant system. The NYC Board of Transportation operated the entire system. Photo credit: New York Transit Museum.

BMT Brooklyn trolleys in 1940

BMT Brooklyn trolleys in 1940 Subway unification also included the BMT’s very large trolley and bus system. Pictured here is Court Street in Downtown Brooklyn. Photo credit: New York Transit Museum.

9th Avenue El in 1940

9th Avenue El in 1940 As soon as unification occurred, some elevated lines in Manhattan and Brooklyn were closed and razed. This is Manhattan’s 9th Avenue Elevated at 110th Street, shortly before it went out of service. The double decker bus shown operated until 1953. Photo credit: New York Transit Museum.

NYC Board of Transportation bus, 1941

NYC Board of Transportation bus, 1941 Mayor LaGuardia replaced a number of Brooklyn trolley routes with buses in 1941. Above is one of those new buses at Fulton Street. Photo credit: New York Transit Museum.

Third Avenue elevated closes

Third Avenue elevated closes In May 1955, Manhattan’s Third Avenue Elevated made its final run and the structure was soon removed. Pictured is a southbound express train charging through 34th Street Station. Photo credit: New York Transit Museum.

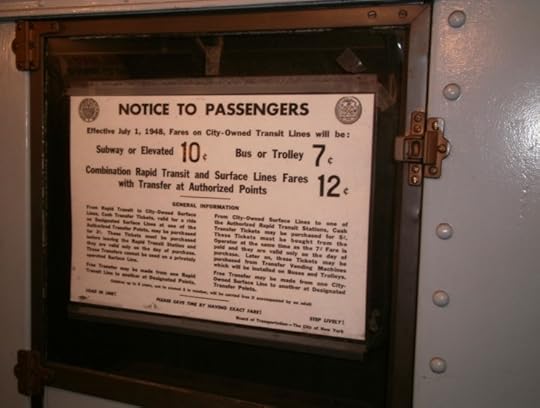

The "nickel ride" ends in 1948

The "nickel ride" ends in 1948 The historic 5¢ fare ended on July 1, 1948, when the subway fare was raised to 10¢. Bus and trolley fare was 7¢ while riders outside of Manhattan paid 12¢ to ride a combination of the subway and buses. Photo credit: Andrew J. Sparberg

New IRT subway car, 1957

New IRT subway car, 1957 Beginning in 1955, large numbers of new subway cars appeared. Above is a R21 IRT car on the #1 Broadway line. It’s shown at the 240th Street Yard in the Bronx. Photo credit: New York Transit Museum.

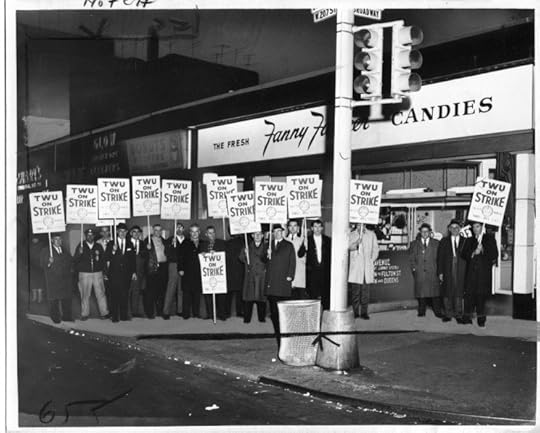

Transit strike, 1966

Transit strike, 1966 In January 1966, a twelve day citywide transit strike occurred, beginning on the first day mayor John Lindsay took office. Above, pickets are seen at the 207th Street and Broadway subway station. Photo credit: TWU Local 100 Archives

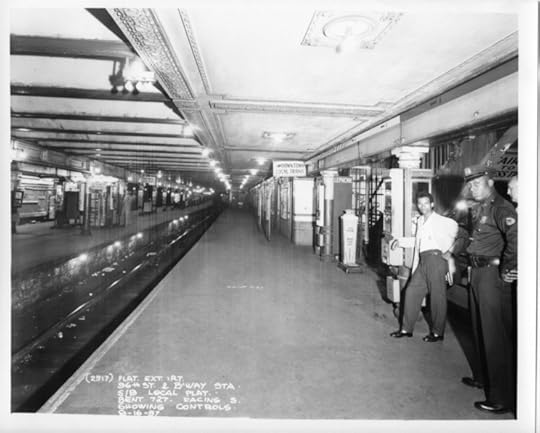

IRT West Side Line is rebuilt, 1957-‘59

IRT West Side Line is rebuilt, 1957-‘59 In 1957-‘59, the Transit Authority rebuilt seven stations on the IRT West Side Line (todays 1, 2, and 3 trains) to accommodate 10 car trains. Shown above is 96th Street before it was modified, showing the separate local platforms that were closed in 1959. Photo credit: New York Transit Museum.

R42 car fleet ordered, 1968

R42 car fleet ordered, 1968 On March 1, 1968, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) became the parent body for the New York City Transit Authority, an arrangement which continues today. The first subway cars the new agency ordered were the R42 class; the R42 was the first car class 100% equipped with A/C. About 50 R42s are still in service in 2015. Photo credit: New York Transit Museum.

Heading image: New IRT subway car, 1957. New York Transit Museum. Used with permission.

The post A vision of New York City’s transit system, from 1940-1968 [slideshow] appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSelma and re-writing history: Is it a copyright problem?Announcing the Oxford World’s Classics Reading GroupTrains of thought: Bob

Related StoriesSelma and re-writing history: Is it a copyright problem?Announcing the Oxford World’s Classics Reading GroupTrains of thought: Bob

Announcing the Oxford World’s Classics Reading Group

We’re excited to announce the launch of the Oxford World’s Classics Reading Group, an online group for everyone who is interested in reading and discussing the classics. The Oxford World’s Classics social media channels will provide a forum for conversation around the chosen book, and every three months we will choose a new work of classic literature for the group to read. The editor of the Oxford World’s Classics edition of the book will provide literary context, discussion questions, and lead an online question-and-answer session around the book.

We’re starting our first season of the Oxford World’s Classics Reading Group with Wuthering Heights, Emily Brontë’s classic love story that incorporates themes such as social class, death and the afterlife, and the supernatural. The setting, a remote farmhouse on the moors of Northern England, is bleak, harsh, wild, and unpredictable, reflecting many of the novel’s characters. Helen Small, Professor of English Literature at the University of Oxford and editor of the Oxford World’s Classics edition of Wuthering Heights, will be leading the Reading Group this season.

If you have a classic that you’ve always wanted to read, let us know and we’ll consider it for next season. In this video, Oxford University Press staff from offices all over the world talk about classic books they’ve always wanted to read but haven’t yet:

You can follow along, and join in the conversation by following us on Twitter and Facebook, and by using the hashtag #OWCreads.

Heading image: Old books. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Announcing the Oxford World’s Classics Reading Group appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEmbark on six classic literary adventuresVirginia Woolf’s Orlando and the country houseTrains of thought: Bob

Related StoriesEmbark on six classic literary adventuresVirginia Woolf’s Orlando and the country houseTrains of thought: Bob

Ballet in black and white: the ‘piano reduction’

For ballet rehearsals in theatres around the world the piano has long been the musical instrument of choice. To engage orchestras to do the detailed, volatile work required in routine rehearsals would be impractical and prohibitively costly, and only at the dress rehearsal will dancers and the orchestra finally come together. The music at all earlier rehearsals is provided through a specially written version of the score called a ‘piano reduction’, containing all the music’s essentials, but ‘reduced’ for one player – a practical, pragmatic realization of the composer’s vision with which dancers and production team can work. Pyotr Tchaikovsky (or his publisher) delegated the creation of Swan Lake and The Nutcracker reductions to others, while the piano versions of Claude Debussy’s commissioned ballet scores Jeux and Khamma were made by the composer himself. Whether created by the composer or another musician, the reduction is an essential component in any ballet production.

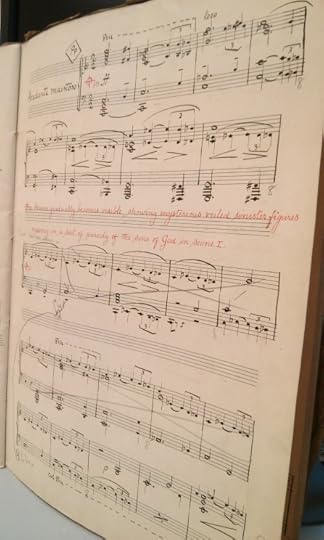

The piano reduction can itself play a critical role in the balletic creative process. Ralph Vaughan Williams’s orchestral score Job: a masque for dancing (intended for a danced masque founded on William Blake’s illustrations for the biblical book of Job) was first performed as a concert work in 1930. The staged premiere took place in July 1931, when Constant Lambert conducted the Carmargo Society’s production at London’s Cambridge Theatre; the choreography was by Ninette de Valois and designs by Gwendolen Raverat. Lambert had also adapted the orchestration to suit the theatre’s small orchestra pit. Vaughan Williams, too busy himself, asked Gustav Holst’s amanuensis Vally Lasker to create a piano score (‘something simple and practical’) for the rehearsals. Quickly completed, several copies were then made for the production staff: ‘Copy No. 2’ was produced in May 1931 and survives in Oxford University Press’s archive. It was neatly calligraphed in black ink (stage directions in red) but soon overlaid with numerous pencilled comments and amendments, each reflecting a rehearsal event, a last-minute change, or a refinement to the stage action or choreography. Bars are added where the stage required more music, or deleted when there was too much; re-voicing and corrections to the music are slipped in; stage instructions are changed or elaborated. A long-vanished but truly creative dialogue between composer, choreographer, and producer is silently re-enacted within this simple, handwritten score.

The Job score. Courtesy of OUP Archives.

The Job score. Courtesy of OUP Archives. After the production, ‘Copy No. 2’ became the basis for the published edition of the reduction brought out by OUP later in 1931. This proudly proclaimed ‘Pianoforte arrangement by Vally Lasker’ on the cover, and it was to be several years before OUP issued the composer’s full orchestral score, with the rehearsal changes duly incorporated. The music of Job thereby reached its definitive form through the vehicle of Lasker’s piano reduction.

An unexpected parallel life emerges. The piano reduction, being a complete and accurate ‘black and white photograph’ of an orchestral score, has its own existence, robust and independent, away from the floor-markings, bar, and rigour of the dance studio. The piano score of Estancia, Alberto Ginastera’s 1941 ballet of the South American pampas, was the source for the separately-issued ‘Pequena Danza’ for piano solo, while Debussy’s posthumously produced children’s ballet La boîte à Joujoux indeed began its life in piano form in 1913 (it was only later orchestrated). Edition Durand’s published edition of the piano score contains André Hellé’s delightful children’s storybook-style coloured illustrations, already envisaging perhaps a life for the music beyond the rehearsal room. The Job printed edition, too, was lavish, with one of the Blake illustrations shown as a frontispiece.

Pianists, perhaps belatedly, are realizing that here lies a hidden, new seam of repertoire, just for them: fine music in expertly crafted arrangements, with a potential life in the concert hall. Here is music to be appreciated on its own merits, highlighting not only the skill of a composer, but of the arranger too, shining new and often revealing light on the structure and textures of the ballet score itself. Jean-Pierre Armengaud, for example, has recorded for Naxos the piano versions of music from Francis Poulenc’s three commissioned ballets (Les animaux modèles, Les biches, and Aubade) – the latter, being originally scored for solo piano and eighteen instruments, is, in the composer’s own reduction, a particular tour de force. Igor Stravinsky’s own brilliantly idiomatic transcription of his 1910 ballet The Firebird is also available as a Naxos recording, played by Idil Biret. And that visionary musical exploration of William Blake’s Job illustrations by Vaughan Williams can now be experienced through the focussed clarity of Vally Lasker’s piano realization in Ian Burnside’s recent recording of Job: a masque for dancing for Albion Records. The music’s inner voicing, and many points of articulation and phrasing emerge in an entirely new way, while the solo medium in no way diminishes the sweep and insight of Vaughan Williams’s conception. The humble piano reduction takes centre stage!

Image credit: Piano keys via iStock.

The post Ballet in black and white: the ‘piano reduction’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe inspiration of Alice in Wonderland: 150 years onOxford’s top 10 carols of 2014A composer’s thoughts on re-presentation and transformation

Related StoriesThe inspiration of Alice in Wonderland: 150 years onOxford’s top 10 carols of 2014A composer’s thoughts on re-presentation and transformation

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers