Oxford University Press's Blog, page 700

February 14, 2015

Fresh Off the Boat and the language of the Asian-American experience

Fresh Off the Boat, the newest addition to ABC’s primetime lineup, has garnered more than its share of attention in the lead-up to its February debut: based on restaurateur Eddie Huang’s critically-acclaimed memoir, it’s the first sitcom in 20 years since Margaret Cho’s All-American Girl to feature an Asian-American family at its epicenter, rightfully assuming its place among the network’s recent crop of 21st-century family comedies, including Modern Family, Blackish, and Cristela.

This fanfare comes at a time when Asian-American identity politics is, for all intents and purposes, increasingly front and center in our national dialogue; in the wake of Wesley Yang’s seminal “Paper Tigers” essay in New York Magazine, Jeremy Lin’s meteoric rise to athletic fame, and the ascendance of YouTube personality KevJumba, Fresh Off the Boat makes strides in shattering what is known as the ‘bamboo ceiling’, a term frequently employed to describe the range of obstacles Asian-Americans encounter in collision with mainstream society.

It’s a new era which, alongside ushering in new attitudes about race, has also pioneered a new vocabulary, one illustrative of multiculturalism as modern American ideal. From the inventive terms ABC to nisei, there is revived interest in the language of the immigrant experience: its tensions, complexities, and — above all else — its vibrancies. Language, in this case, becomes less an heirloom than a living thing, evolving to represent a changing landscape for generations of immigrants, all of whom have strained under the weight of racial discrimination.

There is revived interest in the language of the immigrant experience: its tensions, complexities, and — above all else — its vibrancies.

Give me your tired, your poor

Parsing this “new vocabulary,” of course, involves unraveling the historic origins of the ‘immigrant experience.’ Many invoke textbook narratives, recalling Emma Lazarus’ most memorable lines from the poem ‘The New Colossus’, inscribed on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty: ‘Give me your tired, your poor/ Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.’

But Lazarus’s words, poetic as they were, mostly belied the actual immigrant experience: the phrase ‘fresh off the boat’, first employed against European immigrants, swiftly developed derogatory connotations—alongside other racial slurs like mick, wog, and wop — to deride those who hadn’t fully assimilated into mainstream culture.

No different in their fervid pursuit of ‘the American dream’, hundreds of thousands of Chinese immigrants arrived on the heels of the California Gold Rush in the mid-19th century. And no different than their European counterparts, they too were ostracized by the ‘native’ population, as terms like Chink, coolie, and Chinaman enjoyed widespread use by politicians, including Samuel Gompers of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). This fear of racial otherness manifested itself in the all-encompassing term “Yellow peril,” owing much of its prevalence to use in newspapers owned by William Randolph Hearst.

Language became law when, in 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act suspended all Chinese immigration to the United States until 1943. Even so, this wasn’t the first occasion where Chinese immigrants endured scrutiny: an earlier piece of legislation, colloquially known as the ‘Anti-Coolie’ Act of 1862, imposed special taxes on Chinese businesses in California. Eventually, the phrase ‘Chinaman’s chance’—meaning very poor or negligible prospects—came to appropriately symbolize the unequal treatment Chinese immigrants experienced in their new country of residence.

From San Francisco to New York, the immigration waves of mid-19th century arguably marked the beginning of America as it is contemporaneously known: a heterogeneous country that, in theory, would house democratic multitudes. But for many, there was a chasm between the American ‘dream’ and the actual immigrant experience. From private beliefs to public action, xenophobia spread unchecked, even leading to massacres of Chinese immigrants in Los Angeles, and—most famously—in Rock Springs, Wyoming.

Reclaiming identity

During the mid-20th century, following the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act, Chinese immigration to America resurged, as did use of the phrase ‘fresh off the boat’, revived in 1968 partly thanks to the acronym FOB. Coinciding with the rise of FOB, however, was the spread of the acronym ABC (American-Born Chinese), similar in meaning to the derisive terms ‘banana’ and ‘Twinkie’, denoting a person of Asian descent who is ‘yellow on the outside and white on the inside.’

This dichotomy, above all else, speaks to the duality of the immigrant experience: an external struggle against mainstream perceptions, as well as an internal struggle to tread a middle ground between Americanization and ethnic preservation. For instance, where first-generation immigrants are more likely to resist cultural integration, their children — and grandchildren — more often than not embrace assimilation. These differences are reflected in linguistic distinctions like issei, nisei, and sansei, now used to identify first, second, and third-generation Japanese-Americans.

Indeed, a new generation of Asian-Americans—of which Eddie Huang is a part—grapples with the language of belonging. For many, identity formation becomes a balancing act, ranging from sensitive negotiation to violent oscillation between opposing cultural forces: family and country. Not to mention lingering tensions with racism; while, in recent years, ethnic slurs have declined in mainstream use, familiar stereotypes of Asians have been slower to improve.

In recent years, there has been a renewed effort to reclaim derogatory slurs like ‘fresh off the boat’, as the title of Huang’s memoir and subsequent TV adaptation suggest. ‘Fresh off the boat’ has evolved from slanderous term to unabashed badge of honor, re-appropriated by immigrants themselves as a product of changing times. Eddie Huang’s sitcom, in this sense, could very well transcend itself as the expression of a painful history: it has the potential to shed old hatreds and breathe life into a new vocabulary.

A version of this blog post first appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Image Credit: “An English class for Asian American ILGWU members of Local 23-25, December 15, 1968.” Photo by Kheel Center. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Fresh Off the Boat and the language of the Asian-American experience appeared first on OUPblog.

5 Guys and a Girl pick their all-time favorite NBA All-Stars

As the city buzzes around us in preparation for the 2015 NBA All-Star Weekend, hosted jointly by the New York Knicks and Brooklyn Nets, we caught up with a few of our office’s basketball fans to reflect on their all-time favorite NBA All-Stars — and their entries in the Oxford African American Studies Center. Without further ado, Oxford University Press New York’s ‘5 Guys and a Girl’ weigh in:

* * * * *

Everett Jones: NY Office Services

Top Pick: Julius Erving

Second Pick: Bernard King

“Dr. J made it popular to dunk and have an above the rim game.”

Known to fans and announcers as Dr. J, Julius Erving set new standards of performance in his sport and made the slam-dunk into one of the most exciting moves in professional basketball.

* * * * *

Kishiem Laws: NY Office Services

Top Pick: Kobe Bryant

Second Pick: Kevin Durant

“Kobe has 18 straight All-Star appearances.”

At age seventeen, Kobe Bryant became the youngest guard to be drafted in the history of the National Basketball Association. Bryant blossomed into an NBA superstar within his first three years and went on to lead the Lakers to three consecutive championships from 2000 to 2002.

* * * * *

Michael Franks: NY Office Services

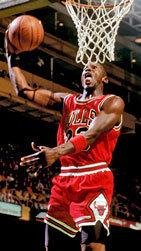

Top Pick: Michael Jordan

Second Pick: Dominique Wilkins

“The 1987 Slam Dunk Contest says it all!”

In 1987, Michael Jordan ran from beyond half-court, leaped from the free-throw line, and glided through the air in a seemingly effortless manner—lifting the ball and then lowering it, contracting his legs and then spreading and extending them—finally dunking the ball fifteen feet later cinching the Dunk Contest Title over Dominique Wilkins.

* * * * *

Godwin Joseph: NY Office Services

Pick: Shaquille O’Neal

Second Pick: Dwayne Wade

“With 15 All-Star Team selections, how could I not pick Shaq?”

A 15-time NBA All-Star, Shaquille O’Neil quickly became one of the NBA’s top centers, and only one of three players in the history of the NBA to win the NBA MVP, All-Star game MVP and Finals MVP awards in the same year.

* * * * *

Fred Hampton: OUP US IT

Top Pick: Wilt Chamberlain

Second Pick: Kareem Adbul-Jabar

“He is the ORIGINAL.”

A legendary basketball player, Wilt Chamberlain was a gifted offensive shooter who scored and rebounded prolifically. In 1978 Chamberlain was elected to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, and in 1996 for the NBA’s fiftieth anniversary he was named one of the fifty greatest players in NBA history.

* * * * *

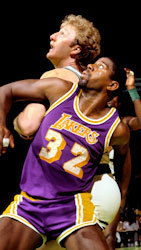

Ayana Young: Online Marketing

Top Pick: Magic Johnson

Second Pick: Jerry West

“There’s a reason they called him Magic.”

Considered one of the greatest point guards and play-makers in the history of the NBA, Magic Johnson ended his 13-year professional career in 1991, but returned to play in the 1992 All-Star Game becoming the first and only retired player to do so and win the All-Star MVP Award.

* * * * *

Image credits: (1) Knicks v Thunder 2010 MSG. Photo by Matt Pirecki. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Julius Erving, 6 November 1974, Sport Magazine Archives. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Kobe Bryant of the Los Angeles Lakers drives to the basket against the Washington Wizards in Washington, D.C., USA on February 3, 2007. Photo by Keith Allison. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (4) Michael Jordan, Chicago Bulls, 1997. Photo by Steve Lipofsky at Basketballphoto.com. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (5) Shaquille O’Neal preparing to shoot a free throw in 2009. Photo by Keith Allison. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (6) Wilt Chamberlain, 1967. Philadelphia 76ers press photo. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (7) Los Angeles Lakers Magic Johnson and Boston Celtics Larry Bird in Game two of the 1985 NBA Finals at Boston Garden. Photo by Steve Lipofsky at Basketballphoto.com. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post 5 Guys and a Girl pick their all-time favorite NBA All-Stars appeared first on OUPblog.

Love stories of America’s founding friends

On Valentine’s Day, we usually think of romance and great love stories. But there is another type of love we often overlook: love between friends, particularly between men and women in a platonic friendship. This is not a new phenomenon: loving friendships were possible and even fairly common among elite men and women in America’s founding era. These were affectionate relationships of mutual respect, emotional support, and love that had to carefully skirt the boundaries of romance. While extravagant declarations of love would have raised eyebrows, these friends found socially acceptable ways to express their affection for one another. Learn more about some special pairs of platonic friends from early America, including some very familiar names.

Eloise Payne and William Ellery Channing

William was best known as a Unitarian minister and early transcendentalist, but to a bright young teacher named Eloise he was “my dear friend.” Eloise looked to William, seven years her senior, for religious and professional advice, but she wasn’t afraid to rebuke him when he became too critical. When she worried that his affections were waning after he started courting the woman who would become his wife, he replied, “You hold the same place in my heart as ever, and I can now say to you with more propriety than before, that few hold a higher.” (Photo credit: Public Domain via The Frick Collection.)

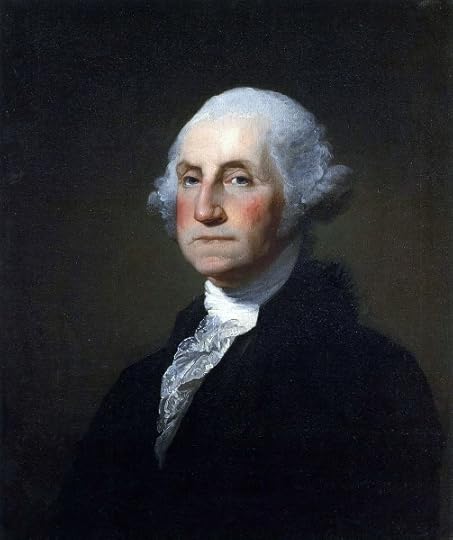

George Washington and Elizabeth Powel

George and Elizabeth met while George was in Elizabeth’s hometown of Philadelphia for the Constitutional Convention. George often spent the evening with Elizabeth and she later visited him at Mount Vernon. They had frank political discussions and exchanged gifts for over a decade. For her fiftieth birthday, George sent her a poetic tribute written by a friend of Elizabeth’s, and he signed one of his last letters to her before his death, “I am truly yours.” (Photo credit: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.)

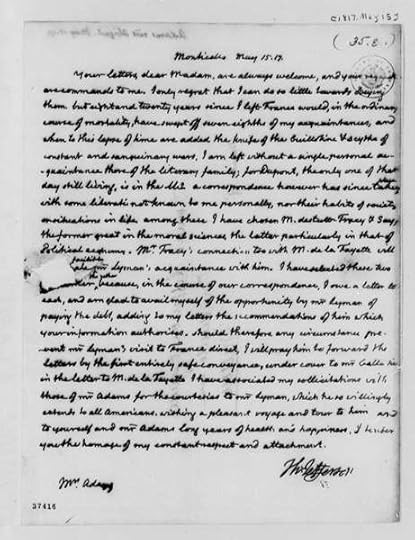

Thomas Jefferson and Abigail Adams

Abigail Adams called her friend Thomas Jefferson “one of the choice ones on earth,” and Thomas greatly admired the wife of his long-time friend John Adams. They both lived in Paris in the 1780’s and attended plays and other events together. Later, he jokingly referred to her as Venus; he wrote from Paris that while selecting Roman busts to send for the Adams’ London home, he passed over the figure of Venus because he “thought it out of taste to have two at table at the same time.” (Photo credit: Public Domain via Library of Congress.)

Margaret Bayard Smith and Anthony Bleecker

Margaret and Anthony first met as young adults in New York City as part of the same circle of writers and intellectuals. Some twenty-five years later, Margaret wrote a novel which Anthony helped to edit. The novel’s central love story was based upon her friendship with Anthony. “Has not friendship recollections as sweet and dear as those of love?” she wrote to him. Her answer: “Yes, indeed it has—at least in my heart.” (Photo credit: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.)

John Rodgers and Anne Pinkney

John Rodgers is best remembered as a navel hero who fought the Barbary pirates and fired the first shots of the War of 1812. But while he was across the Atlantic fighting pirates, he relied on his friend Ann Pinkney at home in Maryland to help further his courtship of a young woman named Minerva Denison. Ann reported back to John on his “goddess” and was pleased to extract a confession of Minerva’s love for John which she passed along. John and Minerva married, while John and Ann remained friends. (Photo credit: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.)

Benjamin Franklin and Georgiana Shipley

Benjamin Franklin was notorious for his flirtations with women, but it’s likely that most of his flirting was merely part of playful friendships. Such appears to be the case with a teenage girl he befriended in London in 1772, Georgiana Shipley. He gave her a pet squirrel named Mungo as well as a snuff box with his portrait painted on the lid. He declared himself “your affectionate friend” and she was even more effusive: “The love and respect I feel for my much-valued friend are sentiments so habitual to my heart that no time nor circumstance can lessen the affection.” (Photo credit: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.)

Gilbert Stuart and Sarah Wentworth Morton

Gilbert Stuart is best known for his portraits of presidents, but his friendship with Boston writer Sarah Wentworth Morton prompted his only known poetry. Gilbert created three portraits of Sarah, one of which he kept for himself. She published a poem praising his artistry, beginning with “Stuart, thy portraits speak with skill divine.” He replied that her poetry created “a cheering influence at my heart” and that ultimately poetry was superior to painting. This was a friendship between a very talented pair! (Photo credit: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.)

Elizabeth Graeme Fergusson and Benjamin Rush

The doctor and writer Benjamin Rush had a long friendship with one of Philadelphia’s smartest women, Elizabeth Graeme Fergusson. Elizabeth wrote Benjamin frequently from her country estate but sometimes worried she didn’t receive enough letters in return. As she wrote in a poem she sent him in 1793, “One Letter a week she surely might claim,/ To keep alive Friendship; and fan its pure Flame.” He may not have written as often as she would like, but he admired her greatly. She was, he said after her death, “a woman of uncommon talents and virtues” who was “beloved by a numerous circle of friends and acquaintances.” (Photo credit: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.)

Eliza Parke Custis and Marquis de Lafayette

The Marquis de Lafayette formed a lasting bond with George Washington during the American Revolution, and his affections later extended to Washington’s step-granddaughter Eliza Parke Custis. Lafayette was a father figure for Eliza, whose own father died when she was young. Eliza confided her troubles in him and he wrote long letters in reply offering advice and affection. The pair wrote each other for years, with Lafayette conveying his “paternal love” and “most affectionate respectful attachments.” (Photo credit: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.)

Featured image: Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States, Howard Chandler Christy (1940). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The post Love stories of America’s founding friends appeared first on OUPblog.

10 fun facts about the harp

The Harp is a string instrument of very ancient lineage that is synonymous with classical music and cupid’s lyre. Over the years, the harp has morphed from its primitive hunting bow shape to its modern day use in corporate branding. Across the globe, each culture has its own variation of this whimsical soft-sounding instrument. Check out these ten fun facts about the harp.

1. The harp is one of the oldest instruments in the world. It dates back to around 3000 B.C. and was first depicted on the sides of ancient Egyptian tombs and in Mesopotamian culture.

Floor pavement representing female dancers. Marble mosaic, ca. 260 AD (Sasanian Era). From the iwan of the so-called palace of Shapur at Bishapur, Iran. Excavated by Roman Ghirshman, ca. 1939–1941. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Floor pavement representing female dancers. Marble mosaic, ca. 260 AD (Sasanian Era). From the iwan of the so-called palace of Shapur at Bishapur, Iran. Excavated by Roman Ghirshman, ca. 1939–1941. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.2. Nowhere is there a larger variety of harps than in Africa. The harp has a place in the traditions of nearly 150 African peoples.

3. The word harpa was first used around the year 600 and is a generic term for stringed instruments. The verb harp means to talk on and on about one subject similar to a harpist plucking the same string over and over.

4. With a range of one to 90 strings per instrument, the harp can be classified into two main categories: the frame harp and the open harp.

5. A modern harpist plays using only the first four fingers on each hand. They pluck the strings near the middle of the harp using the pads of their fingers. Irish harpists use their fingernails to pluck the wire strings.

6. The rapid succession of musical notes played on a harp is called arpeggio and the sweeping motion of the hands across the strings is termed glissando.

7. Once an aristocratic instrument played for royalty, harpists were challenged with being able to evoke three distinct emotions from their audience: tears, laughter, and sleep.

8. The harp has been Ireland’s national symbol since the thirteenth century.

9. The popular Irish beer, Guinness, also features a harp as its symbol.

Guinness da Bar, by Morabito92. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Guinness da Bar, by Morabito92. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.10. In the 20th century, historians and harp aficionados garnered wide-spread interest in reviving the harp and in 1990, the Historical Harp Society was founded and based in North America.

Headline image credit: Celtic Harp. Photo by Holzwurm52. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post 10 fun facts about the harp appeared first on OUPblog.

Self-knowledge: what is it good for?

Marvin is a delusional dater. He somehow talked the gorgeous Maria into going on a date with him, and today is the day. Maria is way out of Marvin’s league but he lacks self-knowledge. He thinks he is better looking, better dressed, and more interesting than he really is. Yet his illusions about himself serve a purpose. They give him self-belief and as a result the date goes better than it would have done otherwise. Maria is still out of Marvin’s league, but is at least impressed by his nerve and self-confidence, if not by his conversation.

The case of the delusional dater suggests that self-knowledge doesn’t necessarily make you happier or more successful, at least in the short term. According to social psychologists Timothy Wilson and Elizabeth Dunn, there are physical and mental benefits associated with maintaining slight or moderate self-illusions, such as believing one is more generous, intelligent, and attractive than is actually the case. There are some truths about ourselves which, like Marvin, we are better off not knowing.

Real world examples of the benefits of moderate self-illusions are not hard to find. In my experience as a university teacher, average students who believe they are better than that tend to work harder and do better than average students who know their own limitations. Studies of HIV-positive men have shown that they are more likely to practice safe sex if they believe they are unlikely to get AIDS. Sometimes positive self-illusions can be even self-fulfilling. Studies of women at weight loss clinics have shown they are more likely to lose weight if they believe they are going to lose weight.

My favourite example of the power of self-illusions is a famous study of snake-phobic subjects who were played what they believed were the sounds of their own heartbeats as they were shown slides of snakes. In fact, instead of their own racing hearts, they were played the steady heartbeats of someone with no fear of snakes. As a result, the snake-phobic subjects inferred that they weren’t that scared of snakes after all and became less snake-phobic.

Knowledge of how generous, attractive, or frightened you are might not sound like “self-knowledge.” We like to think of self-knowledge as something deeper, as knowledge of the “real you.” But the real you isn’t something apart from your thoughts, motives, emotions, character traits, values and personality. Knowledge of these things is knowledge of the “real you,” and the question remains why knowledge of the real you should matter. Most of us have heard of the ancient command to “Know thyself” but few have dared to ask what good it does.

Abstract Reflections, photo by Francisco Antunes, CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr

Abstract Reflections, photo by Francisco Antunes, CC-BY-2.0 via FlickrLow-end explanations of the value of self-knowledge say that self-knowledge is a good thing because it makes you happier or more successful. High-end explanations say that the real point of self-knowledge is that having it enables us to live more authentic and meaningful lives. From this standpoint it doesn’t matter if self-knowledge doesn’t guarantee happiness or success. That was never the point of “Know thyself.”

High-end explanations of the value of self-knowledge are seductive but don’t really work. To be authentic is to be true to yourself, and you might wonder how you can be true to yourself, to who you really are, if you don’t know yourself. Actually, it’s easy to show that authenticity is possible without self-knowledge. Suppose the opportunity arises to cheat in a card game but you don’t cheat because you aren’t a cheat. In refraining from cheating you are being true to yourself but what makes you refrain from cheating is the fact that you aren’t a cheat. You don’t need to know you aren’t a cheat for you not to cheat. You can be true to yourself regardless of whether you know yourself.

Socrates said the unexamined life is not worth living. Could this be why self-knowledge matters? The idea that self-knowledge has something to do with finding meaning in your life is promising but controversial. There is plenty of evidence that people find their life choices more meaningful when they are consistent with the kind of person they think they are, but the kind of person you think you are may be quite different from the kind of person you actually are. Being mistaken about the kind of person you are needn’t prevent you from finding your life meaningful on its own terms.

Am I saying that self-knowledge is worthless? Not at all. What I’m saying – and this might be a surprising thing for a philosopher to be saying – is that self-knowledge is overrated in our culture. The truth of the matter is not that you can’t live authentically, meaningfully, or happily without self-knowledge, but that a modicum of self-knowledge might, depending on the circumstances, improve your prospects of living in these ways. While self-knowledge is no guarantee of happiness, you are unlikely to do well in life if you are grossly self-ignorant. Marvin’s self-illusions might get him through his date with Maria but in the longer term he will save himself the pain of repeated rejection if he stops kidding himself.

“While self-knowledge is no guarantee of happiness, you are unlikely to do well in life if you are grossly self-ignorant.”

The same applies to talentless contestants of reality TV talent shows. It’s hard not to think that delusional contestants who believe they can sing like Michael Jackson would in the end live happier lives if they learned to handle the truth about themselves. How can you plan your life if you are completely clueless about what you are good at? At some point, you need to come to terms with the real you, and the challenge is to figure out how to do that.

Writing in the 17th century, René Descartes saw self-knowledge as strictly first-personal, as the product of a special kind of mental self-examination. Descartes was wrong. We aren’t unbiased observers of our own inner selves, and the studies suggest that the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves aren’t to be trusted. We all like to think well of ourselves.

A better bet is to try to see yourself through the eyes of others. When it comes to the real you, your friends, colleagues, and nearest and dearest probably have deeper insights than you do. The self-knowledge you get by social interaction is indirect and third-personal but that’s okay. For example, you might not think that you are generous but if everyone you are close to thinks that you are tight with money then that trumps your self-conception. In this case, other people know the real you better than you know the real you.

Of course, seeing ourselves through the eyes of others can be hard to do, especially when their opinion is unflattering. That’s one of many factors which make worthwhile self-knowledge so hard to get. So if self-knowledge is something which matters to you then here is some practical advice: try to accept that reliable self-knowledge is not something you can get by self-examination. Instead, try to see yourself as others see you, and give up any idea that you are always the best judge of the real you. Even with the help of others, a degree of self-ignorance is unavoidable. But if self-ignorance is part of the human condition, so is the ability to get by without really knowing ourselves.

This article originally appeared in LUX Magazine.

The post Self-knowledge: what is it good for? appeared first on OUPblog.

February 13, 2015

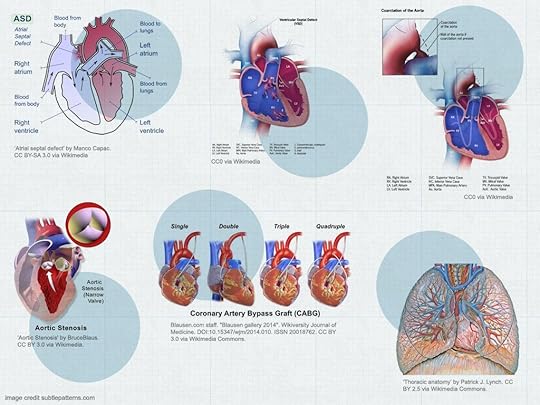

February is Heart Month

February is Heart Month in both the United States and the United Kingdom. It is a time to raise awareness of heart and circulatory diseases. Heart Month highlights all forms of heart disease, from certain life-threatening heart conditions that individuals are born with, to heart attacks and heart failure in later life.

To mark Heart Month, we have created the interactive image below to demonstrate different cardiovascular and thoracic surgical procedures from the Multimedia Manual of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, selected by the Editor-in-Chief, Professor Marko I. Turina. Cardio-thoracic surgery deals specifically with the treatment of diseases affecting organs inside the chest, the heart, and lungs. Heart conditions, which may be treated through cardio-thoracic surgery, include heart valve disease and congenital heart disease.

Heading image: Human heart and circulatory system By bryan Brandenburg. CC BY-SA 3.0 via

A toast to your unconscious mind

We like to think that we can control the contents of our mind, but if we watch ourselves think, we will quickly realize that this isn’t so.

If you don’t believe me, try this experiment. Sit in a quiet room for five minutes, during which time you stare at a blank wall and try to empty your mind of thoughts. Unless you are an exceptional person, you won’t succeed. You might find yourself thinking about what you will have for dinner or about something your significant other said—or failed to say.

You might also have experienced the ideas-from-without phenomenon while doing a crossword puzzle. You needed, say, a three-letter word meaning eggs. You pondered the clue for a minute and drew a complete blank. And then, when you had given up on the puzzle and turned your attention to other things, the answer came to you: ova!

And of course, while you are sleeping, your mind is periodically filled with ideas not of your choosing. We call them dreams, and they can be wildly creative. A gopher singing the blues! How crazy is that?

What is the source of all these ideas? Your unconscious mind.

For your unconscious mind, coming up with answers to crossword puzzle questions is child’s play. It can also solve complex problems. Indeed, if you think back, you will realize that your unconscious mind was the source of some of your best ideas. It saw connections you didn’t see, and it considered possibilities you didn’t consider. As a result, it was able to solve problems that boggled your conscious mind.

It is easy, however, to downplay the role your unconscious mind plays in your mental life. This is because your conscious mind is perfectly happy to take credit for the gems that your unconscious mind hands it. But face it, without the ongoing efforts of your unconscious mind, your conscious mind would flounder.

Once you admit that your unconscious mind is the source of whatever brilliance you possess, you can take steps to extract the maximum possible benefit from your association with it. What you will quickly discover is that it can’t be ordered about.

You can’t, for example, wake up one morning and say, “Unconscious mind, today I want you to prove Goldbach’s Conjecture,” one of the great unsolved problems of mathematics. On hearing this request, your unconscious mind will simply laugh—not that you will realize that it is doing so.

What you must instead do is interest your unconscious mind in working on a problem by working on it with your conscious mind. It might take hours, days, or even weeks of unsuccessful conscious effort before your unconscious mind takes an interest. You will know that it has because you will start experiencing aha moments with respect to that problem.

The period when you are trying to interest your unconscious mind in a problem can be deeply frustrating. A writer might sit there for days or weeks writing a draft of a novel, knowing from experience that there is little chance that the words she has written will make it into the final draft. Instead, they will be thrown away when inspiration strikes and the structure of the novel is finally revealed to her. When this finally happens, she might describe the event as a visit from her muse.

Mathematicians also know from experience that the first step in proving a theorem is to fill wastebaskets with failed attempts at proving it. They know that such efforts are simply the price that must be paid to get their unconscious mind interested in a theorem so that it can reveal the trick to proving it.

Writers and mathematicians undertake their conscious efforts knowing that even if their unconscious mind takes an interest in a problem, there is a chance that it won’t deliver the goods. What has happened, in such cases, is that their conscious mind—which as we have seen isn’t that bright—has foolishly chosen to work on a problem that is so difficult that not even their brilliant unconscious mind can solve it.

Because serious problem-solving starts with this leap of faith, it makes it that much sweeter when your unconscious mind does deliver the goods. It is like watching a magic show in which you are both the magician and the audience. And if you have any humility at all, you will, at the dinner you have to celebrate “your” breakthrough insight, drink a toast to your unconscious mind.

Headline image credit: Pensive woman. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post A toast to your unconscious mind appeared first on OUPblog.

Antibody cancer therapy: a new age?

In 1998 the biotech company Genentech launched Herceptin for the treatment of certain types of breast cancer. Herceptin was an example of a ‘therapeutic antibody’ and was the first of its type for cancer treatment. Antibodies are proteins in our immune system that can target abnormal cells (or bacteria, toxins, viruses, etc.) in the body, and on arriving at the target can set in motion a whole set of biological events that in principle can remove or degrade to a non-dangerous state the abnormal cells.

Frequently, antibodies that we should produce as a natural response to cancer cells that may develop in an organ or tissue are somehow either inhibited from forming, or where they do form are poorly effective at destroying the cancer. To combat this ineffectiveness, specific antibodies against targets on the cancer cell can be made in the laboratory and then reintroduced into the human body, causing the cancer cell to ‘self-destruct’, or become sensitized to natural immune processes that aid the cancer cell killing.

In commenting on the efficacy of such antibodies in the treatment of cancer, delivered to an international antibody conference in San Diego in December 2012, Professor Dane Wittrup (MIT) reminded the audience how limited the response rate (~10%) of current antibody therapies has been. While there may be different views on the reasons for this, we can be reasonably certain that it is due, in part, to some or all of the following: the development of tumor resistance after repeated therapy, the presence of side effects serious enough to warrant interruption or even cessation of treatment, or limited antibody efficacy in the real tumor environment. Despite the investment of billions of dollars in antibody research it is clear that the human immune system still retains many secrets, the decoding of which has been, and continues to be, a long and complex process.

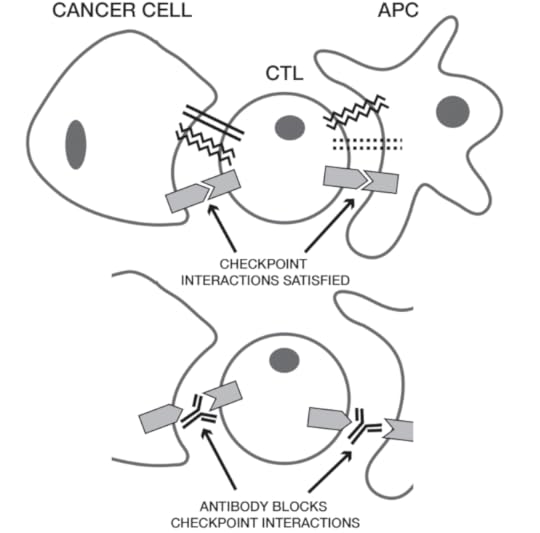

Current antibody therapies target specific ‘circuits’ in cancer cells that are important for the growth of the cancer, either shutting down or blocking key points in specific cellular circuitry, thereby reducing the cancer cell viability. Unfortunately, a cancer is a population of cells and as the inhibitory antibodies move into attack mode, biological changes within the cancer cells over time can activate alternative survival circuits that allow the cancer to evade the antibody effects, effectively becoming ‘resistant’. (For example, some breast cancers are known to become resistant over time to repeated treatment with Herceptin.) To counteract this effect, therapeutic modalities have been developed where two antibodies targeting different sites (circuits) within the cells, or an antibody coupled with a highly toxic drug or toxin molecule, are being adopted. While more effective than the single antibody approach, there is still a heavy hitting part of the immune system, the so-called Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte, or CTL (‘T’ for thymus-derived) mediated response, that often stands idle while the antibody arm of the immune system goes about its work. Why might that be?

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, research groups working at research laboratories in Marseille and a pharmaceutical company in Princeton described two new proteins associated with cells of the immune system that appeared to regulate their activity, allowing them to discriminate between normal tissues and abnormal tissues such as cancer cells. These new proteins were named ‘immune checkpoint receptors’ and are now known to be instrumental in deciding whether or not CTLs become active. When CTLs receive the correct activation signal, they are primed to engage an abnormal target with a view to destroying it in what is part of the ‘adaptive immune response’. Within the cells of the immune system, these checkpoint receptors are part of a complex activating and damping signaling system involving a receptor and a second molecule (or ‘ligand’) that interacts with the receptor in a sort of pas de deux. When the two find each other, as in normal tissues, a CTL attack is prevented (if this did not happen, an autoimmune response could be initiated). So, if the same ligand signal is somehow offered by a tumor cell masquerading as a normal cell, the ‘call to attack’ signals will be overridden and a CTL assault will not occur. In many tumors, just such biochemical changes are known to occur that fool the immune system into ‘thinking’ that the tumor consists of normal human cells thus avoiding attack by CTLs.

Figure 1 by Anthony R. Rees

Figure 1 by Anthony R. ReesAs with many aspects of biological systems, the adaptive immune system is a balancing act between allowing effective immune responses to alien agents, such as bacteria, viruses, toxic molecules, and the like, and at the same time avoiding mounting similar responses to our own tissues, organs, and cells that could lead to ‘autoimmunity’. Immunologists use the term ‘tolerance’ to describe this protection that self-tissues and organs experience as the immune system goes about its work. Lupus erythematosus and multiple sclerosis are two examples of autoimmune responses where the normal regulatory controls have been interrupted and immune antibodies or cells have attacked normal, healthy tissues with often debilitating effects. It is currently thought that checkpoint receptors and their partner ligands play an important role in maintaining this tolerance state in normal healthy persons, preventing unwanted autoimmune responses.

But what if antibodies could be targeted to these checkpoint receptors, blocking the ability of the tumor cell to interact with the receptors on CTLs, and hijacking their deceptive “I am normal” signal? (see Figure 1). This would mean, of course, that in theory, any cell, normal or abnormal, could be a target for CTL killing since both types of cell would have their “I am normal” signal blocked. Dangerous? Possibly, if not controlled. Desirable? If a tumor is so aggressive (e.g. melanoma, pancreatic cancer, etc.) that some autoimmune side effects could be tolerated or clinically managed in order to rid the body of the cancer, perhaps the therapeutic modality would be justified.

Well, we can do better than ‘in theory’. In a recent study of patients with advanced melanoma, one of the most aggressive tumors known and refractory to most therapeutic regimes, two different antibodies against each of the two most characterized immune checkpoint receptors showed spectacular results. In summary, the Phase I/II clinical trial results showed that 40% of patients treated with the combined antibody therapy experienced tumor shrinkage, and 65% of patients experienced shrinkage or stable disease. While these results truly are impressive we cannot yet declare that the war against cancer is approaching resolution, despite the claims of some enthusiasts.

As I noted above, immune checkpoint receptors are important in avoiding immune responses to our own tissues and organs. If their regulatory role is undermined by antibody blockade then autoimmune effects could be anticipated. In fact, in all clinical trials so far conducted with antibodies against these targets, autoimmune responses have been seen, including colitis, dermatitis, hypophysitis, pneumonitis, and hepatitis. These are classes of side effects the clinical community is not accustomed to seeing during antibody therapy, and will require stringent observation during treatment while improved therapeutic regimes are developed that manage these autoimmune effects.

Despite the embryonic nature of this approach, we have truly entered a new age for antibody therapy. As with all checkpoints, two way traffic is ever present, and while in one direction there may be freedom, in the other may lie painful experiences that have to be managed. The key for the future success of this approach will be the development of immune strategies that allow the benefits of immune checkpoint inhibition in cancer treatment to be counterbalanced by clever therapy designs that avoid, or at least minimize, the associated disadvantages.

Header image: Breast cancer cell. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Antibody cancer therapy: a new age? appeared first on OUPblog.

5,000 years of the music of romance, courtship, and sex

How do you approach the history of love? Is it through psychology and the understanding of emotion? Is it through the great works of literature? Or is it through sound — from the chord that pulls the heart strings to the lyric that melts your heart?

But this music has a strange history of its own. We can trace our ‘saccharine’ comments to Ancient Rome and the language of servitude to the Convivencia. Discover the fascinating patterns in the history of love songs in the following timeline, based on the key findings and milestones from Ted Gioia’s Love Songs: The Hidden History.

Headline image credit: Music by Gustav Klimt. Public domain via WikiArt.

The post 5,000 years of the music of romance, courtship, and sex appeared first on OUPblog.

The King’s genes

On 25th March 2015, 530 years after his death, King Richard III of England will be interred in Leicester Cathedral. This remarkable ceremony is only taking place because of the success of DNA analysis in identifying his skeletal remains. So what sort of genes might a king be expected to have? Or, more prosaically, how do you identify a long dead corpse from its DNA? Several methods were used, and in particular the deduction of the skeleton’s probable hair and eye colour raises some interesting questions about future trends in forensic DNA analysis.

Richard III is one of England’s best known kings, largely due to the famous play of William Shakespeare in which he is portrayed as an evil villain. He only reigned for two years and was killed at the age of 32 at the battle of Bosworth in 1485. According to the historical records he was unceremoniously buried at Greyfriars Friary in Leicester. At some stage knowledge of the exact location of Richard’s burial was lost. But in 2012 excavations under a car park at the probable site of the former friary yielded “skeleton 1″. Suspicion of his royal identity was excited by the fact that the skeleton had a severely bent spine causing the right shoulder to be higher than the left. This well-known deformity of Richard was mentioned in a contemporary source, as well as by Shakespeare. Furthermore, the skeleton was male, the age was about right, it had evidently been killed in battle, and the radiocarbon date was consistent with death in 1485.

This was all very suggestive, but it was the DNA analysis that really proved the case. The work was led by a team at the University of Leicester, with participation by many other UK and European centres. It is important to note that this was not the normal type of forensic DNA identification, which relies on comparing a set of highly variable DNA markers to a database. Such analysis is fine so long as your suspect is in the database, but it is no use for identifying a long dead individual who is not in any database.

By far the best evidence for the identity of Richard III comes from the analysis of his mitochondrial DNA. Mitochondria are bodies found in every cell, responsible for the production of energy. They have their own DNA which is passed down the generations only through the female line. Barring the occasional new mutation, the DNA sequence of mitochondrial DNA should be identical from mother to daughter down a particular female line of descent. Like their sisters, males also carry the mitochondrial DNA of their mothers, but they do not pass it down to their own offspring.

Richard will have shared mitochondrial DNA with his sister, Anne of York. Two complete female lines of descent were traced back to Anne of York, one of 17 generations down to Michael Ibsen, a resident of London, and the other of 19 generations down to Wendy Duldig, formerly of New Zealand. Complete sequencing of their mitochondrial DNA showed a 100% match between skeleton 1 and of Michael Ibsen, and a single base change compared to Wendy Duldig. One change over this period of time is quite likely to be a new mutation. The sequence family (haplogroup) to which the mitochondrial DNA sequence belongs is a fairly rare one, so few other people in England in 1485 would have shared it and in fact the team has systematically ruled out all the other males of the period who might have shared it because of a common female lineage with Richard III. So this match is highly significant and is the best piece of evidence that the “skeleton 1″ is indeed King Richard.

By Bdna. gif: Spiffistan derivative work: Jahobr (Bdna.gif). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

By Bdna. gif: Spiffistan derivative work: Jahobr (Bdna.gif). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons Also applied was a newer method which is a technique for predicting the hair and eye colour of someone from their DNA. The most important variants affecting hair colour are mutations of a gene called MC1R, which encodes a cell surface receptor for a hormone. Individuals carrying variants of the MC1R gene with reduced function are likely to have red or blond hair rather than the normal dark hair. The pigmentation of the iris of the eye depends significantly on a gene called OCA2, encoding a protein which transports tyrosine into cells. Again variants of reduced function give less pigmented eyes, meaning that the colour is blueish rather than brownish. Recently a Dutch group created a forensic test based on variants at 24 genetic loci, of which 11 are in the MC2R gene and the rest in 12 other positions including the OCA2 gene. Identification of these 24 variants yields a fairly accurate prediction of hair and eye colour, and in the case of skeleton 1 the prediction was for blue eyes and blond hair. The existing portraits of Richard III all date from some time after his death but the older ones do indeed show light-coloured eyes and reddish-brown hair, an appearance which is consistent with the prediction.

These two types of analysis indicate two rather different senses in which we use the word “gene”. The sequence variants of the mitochondrial DNA, like those used in normal forensic identification, do not, in general, affect the characteristics of the individuals carrying them. The DNA changes often lie outside actual genes, in the regions of DNA between genes. They are better described as “markers” than as “genes”. But the hair and eye colour analysis is based at least partly on actual gene variants that might be expected to generate those visible characteristics.

How much further might this kind of analysis be pushed? Could the height, facial features or skin colour of a crime suspect be deduced from their DNA? The essential issue is the number of gene variants in the population that affect a feature. If it is relatively small, as with hair and eye colour, then prediction is possible. If it is very large, as for height, then it is not possible, because most of the variants affecting height have too small effects to be detectable. Most of the human characteristics that have been studied in this way have turned out to depend on a very large number of variants of small effect. So, contrary to popular perception, there are real limits to what is possible in terms of prediction of bodily features from DNA data. There will doubtless be some other features that are predictable, and these may eventually include skin colour. But unless a completely new approach is invented, it is unlikely that we shall ever see an identikit picture of a suspect generated from DNA at the crime scene.

Featured image credit: Stained glass, by VeteranMP. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post The King’s genes appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDid you say millions of genomes?Darwin’s dice [infographic]What’s love got to do with it?

Related StoriesDid you say millions of genomes?Darwin’s dice [infographic]What’s love got to do with it?

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers