Oxford University Press's Blog, page 699

February 17, 2015

Another side of Yoko Ono

The scraps of an archive often speak in ways that standard histories cannot. In 2005, I spent my days at the Paul Sacher Foundation in Basel, a leading archive for twentieth-century concert music, where I transcribed the papers of the German-Jewish émigré composer Stefan Wolpe (1902-1971). The task was alternately exhilarating and grim. Wolpe had made fruitful connections with creators and thinkers across three continents, from Paul Klee to Anton Webern to Hannah Arendt to Charlie Parker. An introspective storyteller and exuberant synthesizer of ideas, Wolpe narrated a history of modernism in migration as a messy, real-time chronicle in his correspondence and diaries. Yet, within this narrative, the composer had also reckoned with more than his share of death and loss as a multiply-displaced Nazi-era refugee. He had preserved letters from friends as symbols of the ties that had sustained him, in some cases carrying them over dozens of precarious border crossings during his 1933 flight. By the 1950s, his circumstances had calmed down, after he had settled in New York following some years in Mandatory Palestine. Amidst his mid-century papers, I was surprised to come across a cache of artfully spaced poems typewritten on thick leaves of paper, with the attribution “Yoko Ono.” The poems included familiar, stark images of death, desolation, and flight. It was only later that I realized they responded not to Wolpe’s life history, but likely to Ono’s own. The poems inspired a years-long path of research that culminated in my article, “Limits of National History: Yoko Ono, Stefan Wolpe, and Dilemmas of Cosmopolitanism,” recently published in The Musical Quarterly.

Yoko Ono befriended Stefan Wolpe and his wife the poet Hilda Morley in New York City around 1957. Although of different backgrounds and generations, Wolpe and Ono were both displaced people in a city of immigrants. Both had been wartime refugees, and both endured forms of national exile, though in different ways. Ono had survived starvation conditions as an internal refugee after the Tokyo firebombings. She was twelve when her family fled the city to the countryside outside Nagano, while her father was stranded in a POW camp. By then, she had already felt a sense of cultural apartness, since she had spent much of her early childhood shuttling back and forth between Japan and California, following her father’s banking career. When she began her own career as an artist in New York in the 1950s, Ono entered what art historian Midori Yoshimoto has called a gender-based exile from Japan. Her career and lifestyle clashed with a society where there were “few alternatives to the traditional women’s role of becoming ryōsai kenbo (good wives and wise mothers).” Though Ono eventually became known primarily as a performance and visual artist, she identified first as a composer and poet. After she moved to the city to pursue a career in the arts, Ono’s family disowned her. It was around this time that she befriended the Wolpe-Morleys, who often hosted her at their Upper West Side apartment, where she “loved the intellectual, warm, and definitely European atmosphere the two of them had created.”

In 2008, I wrote a letter to Ono, asking her about the poems in Wolpe’s collection. Given her busy schedule, I was surprised to receive a reply within a week. She confirmed that she had given the poems to Wolpe and Morley in the 1950s. She also shared other poems and prose from her early adulthood, alongside a written reminiscence of Wolpe and Morley. She later posted this reminiscence on her blog several months before her 2010 exhibit “Das Gift,” an installation in Wolpe’s hometown Berlin dedicated to addressing histories of violence. The themes of the installation trace back to the earliest phase of her career when she knew Wolpe. During their period of friendship, both creators devoted their artistic projects to questions of violent history and traumatic memory, refashioning them as a basis for rehabilitative thought, action, and community.

Guggenheim Museum, 88th St. & 5th Ave., New York City. Under construction II, 12 November 1957. Gottscho-Schleisner, Inc., photographer. Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Guggenheim Museum, 88th St. & 5th Ave., New York City. Under construction II, 12 November 1957. Gottscho-Schleisner, Inc., photographer. Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Virtually no historical literature acknowledges Ono’s and Wolpe’s connection, which was premised on shared experiences of displacement, exile, and state violence. Their affiliation remains virtually unintelligible to standard art and music histories of modernism and the avant-garde, which tend to segregate their narratives along stable lines of genre, medium, and nation—by categories like “French symbolist poetry,” “Austro-German Second Viennese School composition,” and “American experimental jazz.” From this narrow perspective, Wolpe the German-Jewish, high modernist composer would have little to do with Ono the expatriate Japanese performance artist.

What do we lose by ignoring such creative bonds forged in diaspora? Wolpe and Ono both knew what it was to be treated as less than human. They had both felt the hammer of military state violence. They both knew what it was to not “fit” in the nation—to be neither fully American, Japanese, nor German. And they both directed their artistic work toward the dilemmas arising from these difficult experiences. The record levels of forced displacement during their lifetimes have not ended, but have only risen in our own. According to the most recent report from the UN High Commissioner on Refugees, “more people were forced to flee their homes in 2013 than ever before in modern history.” Though the arts cannot provide refuge, they can do healing work by virtue of the communities they sustain, with the call-and-response of human recognition exemplified in boundary-crossing friendships like Wolpe’s and Ono’s. And to recognize such histories of connection is to recognize figures of history as fully human.

Headline image credit: Cards and poems made for Yoko Ono’s Wish Tree and sent to Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden (Washington), 7 November 2010. Photo by Gianpiero Actis & Lidia Chiarelli. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Another side of Yoko Ono appeared first on OUPblog.

The Grand Budapest Hotel and the mental capacity to make a will

Picture this. A legendary hotel concierge and serial womaniser seduces a rich, elderly widow who regularly stays in the hotel where he works. Just before her death, she has a new will prepared and leaves her vast fortune to him rather than her family.

For a regular member of the public, these events could send alarm bells ringing. “She can’t have known what she was doing!” or “What a low life for preying on the old and vulnerable!” These are some of the more printable common reactions. However, for cinema audiences watching last year’s box office smash, The Grand Budapest Hotel directed by Wes Anderson, they may have laughed, even cheered, when it was Tilda Swinton (as Madame Céline Villeneuve Desgoffe und Taxis) leaving her estate to Ralph Fiennes (as Monsieur Gustave H) rather than her miffed relatives. Thus the rich, old lady disinherits her bizarre clan in what recently became 2015’s most BAFTA-awarded film, and is still up for nine Academy Awards in next week’s Oscars ceremony.

Wills have always provided the public with endless fascination, and are often the subject of great books and dramas. From Bleak House and The Quincunx to Melvin and Howard and The Grand Budapest Hotel, wills are often seen as fantastic plot devices that create difficulties for the protagonists. For a large part of the twentieth century, wills and the lives of dissolute heirs have been regular topics for Sunday journalism. The controversy around the estate of American actress and model, Anna Nicole Smith, is one such case that has since been turned into an opera, and there is little sign that interest in wills and testaments will diminish in the entertainment world in the coming years.

“[The Vegetarian Society v Scott] is probably the only case around testamentary capacity where the testator’s liking for a cooked breakfast has been offered as evidence against the validity of his will.”

Aside from the drama depicted around wills in films, books, and stage shows, there is also the drama of wills in real life. There are two sides to every story with disputed wills and the bitter, protracted, and expensive arguments that are generated often tear families apart. While in The Grand Budapest Hotel the family attempted to solve the battle by setting out to kill Gustave H, this is not an option families usually turn to (although undoubtedly many families have thought about it!).

Usually, the disappointed family members will claim that either the ‘seducer’ forced the relative into making the will, or the elderly relative lacked the mental capacity to make a will; this is known as ‘testamentary capacity’. Both these issues are highly technical legal areas, which are resolved dispassionately by judges trying to escape the vehemence and passion of the protagonists. Regrettably, these arguments are becoming far more common as the population ages and the incidence of dementia increases.

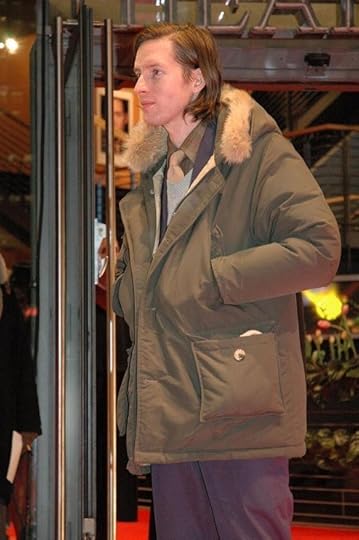

Wes Anderson, director of The Grand Budapest Hotel. By Popperipopp. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Wes Anderson, director of The Grand Budapest Hotel. By Popperipopp. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The diagnosis of mental illness is now far more advanced and nuanced than it was when courts were grappling with such issues in the nineteenth century. While the leading authority on testamentary capacity still dates from a three-part test laid out in the 1870 Banks v Goodfellow case, it is still a common law decision, and modern judges can (and do) adapt it to meet advancing medical views.

This can be seen in one particular case, The Vegetarian Society v Scott, in which modern diagnosis provided assistance when a question arose in relation to a chronic schizophrenic with logical thought disorder. He left his estate to The Vegetarian Society as opposed to his sister or nephews, for whom he had a known dislike. There was evidence provided by the solicitor who wrote the will that the deceased was capable of logical thought for some goal-directed activities, since the latter was able to instruct the former on his wishes. It was curious however that the individual should have left his estate to The Vegetarian Society, as he was in fact a meat eater. However unusual his choice of heir, the deceased’s carnivorous tendencies were not viewed as relevant to the issues raised in the court case.

As the judge put it, “The sanity or otherwise of the bequest turns not on [the testator’s] for food such as sausages, a full English breakfast or a traditional roast turkey at Christmas; nor does it turn on the fact that he was schizophrenic with severe thought disorder. It really turns on the rationality or otherwise of his instructions for his wills set in the context of his family relations and other relations at various times.”

This is probably the only case around testamentary capacity where the testator’s liking for a cooked breakfast has been offered as evidence against the validity of his will.

For lawyers, The Grand Budapest Hotel’s Madame Céline Villeneuve Desgoffe und Taxis is potentially a great client. Wealth, prestige, and large fees for the will are then followed by even bigger fees in the litigation. If we are to follow the advice of the judge overseeing The Vegetarian Society v Scott, Gustave H would have inherited all of Madame Céline’s money if she was seen to be wholly rational when making her will.

Will disputes will always remain unappealing and traumatic to the family members involved. However, as The Grand Budapest Hotel has shown us, they still hold a strong appeal for cinema audiences and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future.

Feature image: Reflexiones by Serge Saint. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post The Grand Budapest Hotel and the mental capacity to make a will appeared first on OUPblog.

February 16, 2015

How disease names can stigmatize

On 10 February 2015, the long awaited report from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) was released regarding a new name — Systemic Exertion Intolerance Disease — and case definition for chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). Because I was quoted regarding this report in a , in part due to having worked on these issues for many years, hundreds of patients contacted me over the next few days.

The reaction from patients was mixed at best, and some of the critical comments include:

“This new name is an abomination!”

“Absolutely outrageous and intolerable!”

“I find it highly offensive and misleading.”

“It is pathetic, degrading and demeaning.”

“It is the equivalent of calling Parkinson’s Disease: Systemic Shaking Intolerance Disease.”

“(It) is a clear invitation to the prejudiced and ignorant to assume ‘wimps’ and ‘lazy bums.’”

“The word ‘exertion,’ to most people, means something substantial, like lifting something very heavy or running a marathon – not something trivial, like lifting a fork to your mouth or making your way across the hall to the bathroom. Since avoiding substantial exertion is not very difficult, the likelihood that people who are not already knowledgeable will underestimate the challenges of having this disease based on this name seems to me extremely high.”

Several individuals were even more critical in their reactions — suggesting that the Institute of Medicine-initiated name change effort represented another imperialistic US adventure, which began in 1988 when the Centers for Disease Control changed the illness name from myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) to chronic fatigue syndrome. Patients and advocacy groups from around the world perceived this latest effort to rename their illness as alienating, expansionistic, and exploitive. The IOM alleged that the term ME is not medically accurate, but the names of many other diseases have not required scientific accuracy (e.g., malaria means bad air). Regardless of how one feels about the term ME, many patients firmly support it. Our research group has found that a more medically-sounding term like ME is more likely to influence medical interns to attribute a physiological cause to the illness. In response to a past blog post that I wrote on the name change topic, Justin Reilly provided an insightful historical comment: for 25 years patients have experienced “malfeasance and nonfeasance” (also well described in Hillary Johnson’s Osler’s Web). This is key to understanding the patients’ outrage and anger to the IOM.

So how could this have happened? The Institute of Medicine is one of our nation’s most prestigious organizations, and the IOM panel members included some of the premier researchers and clinicians in the myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome arenas, many of whom are my friends and colleagues. Their review of the literature was overall comprehensive; their conclusions were well justified regarding the seriousness of the illness, identification of fundamental symptoms, and recommendations for the need for more funding. But these important contributions might be tarnished by patient reactions to the name change. The IOM solicited opinions from many patients as well as scientists, and I was invited to address the IOM in the spring regarding case definition issues. However, their process in making critical decisions was secretive, and whereas for most IOM initiatives this is understandable in order to be fair and unbiased in deliberations, in this area — due to patients being historically excluded and disempowered — there was a need for a more transparent, interactive, and open process.

So what might be done at this time? Support structural capacities to accomplish transformative change. Set up participatory mechanisms for ongoing data collection and interactive feedback, ones that are vetted by broad-based gatekeepers representing scientists, patients, and government groups. Either the Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Advisory Committee (that makes recommendations to the Secretary of US Department of Health and Human Services) or the International Association of ME/CFS (the scientific organization) may appoint a name change working group with international membership to engage in a process of polling patients and scientists, sharing the names and results with large constituencies, and getting buy in — with a process that is collaborative, open, interactive, and inclusive. Different names might very well apply to different groups of patients, and there is empirical evidence for this type of differentiation. Key gatekeepers including the patients, scientists, clinicians, and government officials could work collaboratively and in a transparent way to build a consensus for change, and most critically, so that all parties are involved in the decision-making process.

Headline image credit: Hospital. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post appeared first on OUPblog.

Education, metaphorically speaking

What do we think education means? What do we believe are teaching’s purpose, status, and function in society? A useful way to reflect on our pre-conceptions and assumptions about anything is to step back and consider the metaphors we automatically apply when thinking or speaking of it. This is a particularly useful exercise for the trainee teacher, who, for obvious reasons, is likely to frame teaching primarily in terms of a performance – something that is observed, analysed, graded and, if all goes well, given the pedagogic equivalent of a five star review. For the experienced teacher, this same metaphor will re-emerge from time to time in the face of inspections, institutional self-evaluations, and peer observations; but it is likely to become obsolete as newer, more productive ideas about teaching develop over time.

A dominant metaphor can not only tell us about how the teacher positions herself in relation to her role, but also about how that role is regarded by society. We talk increasingly, for example, of a teacher ‘delivering’ the curriculum. The teacher is construed here as a delivery agent, a go-between whose role is to present to learners a curriculum which has been conceived, devised, and constructed elsewhere. The idea of delivery in itself suggests a one way process that discounts the possibility of dialogue, critical enquiry, and mutual learning. So could there be a potential contradiction here between this concept of the role and our wider understandings of what it means to be a professional? And if so, will the teacher who is encouraged to see their function primarily in terms of ‘delivery’ experience any less satisfaction in their work than the teacher who would describe their professional practice in terms of ‘nurture and nourishment’? These are interesting questions; and part of the answer, of course is that most experienced teachers will view their role differently over time and according to circumstance; some days it’s an endless postal round and on others it’s all the joy of conducting the Royal Philharmonic through Beethoven’s Ninth.

This is not just a question of language; nor is it a roundabout way of posing the key question about the primary purpose of education: whether it is to serve the economy, or to nurture the potential of each individual, or – somehow – to do both. As Lakoff and Johnson (1980) point out, our entire conceptual system is in its very nature metaphorical. We think in metaphors and they play a large part in defining the way we perceive our everyday reality. When we talk of a teacher ‘conducting’ a lesson, therefore, we’re introducing a whole range of assumptions about role and function, and at the same time applying judgements about value, which are quite different to those we may infer when we hear of a lesson being ‘delivered’.

Metaphors can also succinctly encapsulate certain expectations or models of educational practice. A good example here is Paulo Freire’s description of the hierarchical and instrumental approach to teaching and learning as a ‘banking’ model. Here, the teacher is seen as the repository and dispenser of knowledge, and the learner as recipient; an unequal power relationship in which knowledge or skill is viewed as a commodity and which offers no potential for genuine development either of the learner or the teacher. We might contrast this with the metaphor of education as exploration, a joint enterprise and mutually fulfilling adventure undertaken by teacher and learners together. And then there is the metaphor of the farm or the garden in which the teacher nurtures successive ‘crops’ of learners; or even the image that sometimes surfaces of education as war, in which the teacher is pitted against the learners in a battle of wills to subdue, shape, and eventually socialise them. Indeed, the metaphors we find ourselves inhabiting can provide us with insight into just what it is we think education is for.

Image Credit: Teacher by Kevin Dooley. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Education, metaphorically speaking appeared first on OUPblog.

An interview with the Editors of Global Summitry

Global Summitry is a new journal published by Oxford University Press in association with University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and Rotman School of Management. The journal features articles on the organization and execution of global politics and policy. The first issue is slated to publish in summer 2015. We sat down with editors Alan Alexandroff and Don Brean to discuss the changing global summitry field and their plans for the journal’s digital scope, including audio podcasts, and videos.

* * * * *

What new approaches will Global Summitry bring to its field?

Global Summitry is concerned with examining today’s international governance in all of its dimensions. The Journal, it is hoped, will describe, analyse, and evaluate the evolution, the contemporary setting, and the future of collaboration of the global order. Global Summitry has emerged to capture contemporary global policy-making in all its complexity.

Global Summitry is dedicated to raising public knowledge of the global order and its policy outcomes. The Journal seeks informed commentary and analysis to the process and more particularly, the outcomes of global summitry. Global Summitry will feature articles on the organization and execution of global politics and policy from a variety of perspectives — political, historical, economic, and legal — from academics, policy experts, and media personnel, as well as from distinguished officials and professionals in the field.

How has the field changed in the last 25 years?

There has been dramatic change in the global order and its actors. The ending of the Cold War and the demise of the Soviet Union left the United States as the last superpower. The end of the Cold War saw the rise of global governance and the primary leadership of the United States. Increasingly, the problems of the international system focused on growing economic and political interdependence questions. Alongside the formal institutions of international organization — the UN and Bretton Woods systems — new informal institutions — the G7/8, APEC, EAS, NSS, and the G20 — emerged to meet the growing challenges — climate change, development, human rights and justice, nuclear material security, global poverty and development, and global security. And, with the traditional great powers, we saw the emergence of the new large emerging market states, like Brazil and India, but most spectacularly, China.

Palais des Nations by Eferrante. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Palais des Nations by Eferrante. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Today global governance involves a variety of actors — international organizations, both formal, and informal, states, transgovernmental networks, and select non-state entities. All of these actors are involved in the organization and execution of global politics and policy today. Global summitry today is concerned with the architecture, the institutions and, most critically, the political behavior and outcomes in coordinated global initiatives. We will reach out to scholars from all across the globe from the traditional academic centers, to the new centers in the BRICS and the New Frontier states for commentary and insights into the global order.

What do you hope to see in the coming years from both the field and the journal?

The global summitry field will chronicle, we hope, how international governance meets the challenges of economic and political interdependence. But attention will also be directed to understanding how we meet the growing geopolitical tensions that have appeared — conflict with Russia in Europe, the new tensions in East Asia, the growing disorder in the Middle East that have created consequences well beyond that region. Global Summitry will bring expert description, analysis, and evaluation to a field that until now has not been a stand-alone focus of inquiry by researchers, policy analysts, media and officials from across the globe.

What are your plans to innovate and engage with your audience?

We see a multi-platform world evolving for all academic publishing. As a result, from the commencement of Global Summitry, we intend to present information through all contemporary digital means. The Journal intends to provide a steady stream of academic and policy articles of course but we are determined to offer video interviews with our experts, policy makers, and media guests. We also intend to provide podcast presentations and discussions. As various digital platforms evolve, we anticipate evolving as well.

The post An interview with the Editors of Global Summitry appeared first on OUPblog.

Trains of thought: Roxana

Tetralogue by Timothy Williamson is a philosophy book for the commuter age. In a tradition going back to Plato, Timothy Williamson uses a fictional conversation to explore questions about truth and falsity, knowledge and belief. Four people with radically different outlooks on the world meet on a train and start talking about what they believe. Their conversation varies from cool logical reasoning to heated personal confrontation. Each starts off convinced that he or she is right, but then doubts creep in. During February, we will be posting a series of extracts that cover the viewpoints of all four characters in Tetralogue. What follows is an extract exploring Roxana’s perspective.

Roxana is a heartless logician with an exotic background. She would much rather be right than be liked, and as a result she argues mercilessly with the other characters.

Roxana: You appear not to know much about logic.

Sarah: What did you say?

Roxana: I said that you appear not to know much about logic.

Sarah: And you appear not to know much about manners.

Roxana: If you want to understand truth and falsity, logic will be more useful than manners. Do any of you remember what Aristotle said about truth and falsity?

Bob: Sorry, I know nothing about Aristotle.

Zac: It’s on the tip of my tongue.

Sarah: Aristotelian science is two thousand years out of date.

Roxana: None of you knows. Aristotle said ‘To say of what is that it is not, or of what is not that it is, is false, while to say of what is that it is, or of what is not that it is not, is true’. Those elementary principles are fundamental to the logic of truth. They remain central in contemporary research. They were endorsed by the greatest contributor to the logic of truth, the modern Polish logician Alfred Tarski.

Bob: Never heard of him. I’m sure Aristotle’s saying is very wise; I wish I knew what it meant.

Roxana: I see that I will have to begin right at the very beginning with these three.

Sarah: We can manage quite well without a lecture from you, thank you very much.

Roxana: It is quite obvious that you can’t.

Roxana: It is quite obvious that you can’t.

Zac: I’m afraid I didn’t catch your name.

Roxana: Of course you didn’t. I didn’t say it.

Zac: May I ask what it is?

Roxana: You may, but it is irrelevant.

Bob: Well, don’t keep us all in suspense. What is it?

Roxana: It is ‘Roxana’.

Zac: Nice name, Roxana. Mine is ‘Zac’, by the way.

Bob: I hope our conversation wasn’t annoying you.

Roxana: Its lack of intellectual discipline was only slightly irritating.

Bob: Sorry, we got carried away. Just to complete the introductions, I’m Bob, and this is Sarah.

Roxana: That is enough time on trivialities. I will explain the error in what the woman called ‘Sarah’ said.

Sarah: Call me ‘Sarah’, not ‘the woman called “Sarah” ’, if you please.

Bob: ‘Sarah’ is shorter.

Sarah: Not only that. We’ve been introduced. It’s rude to describe me at arm’s length, as though we weren’t acquainted.

Roxana: If we must be on first name terms, so be it. Do not expect them to stop me from explaining your error. First, I will illustrate Aristotle’s observation about truth and falsity with an example so simple that even you should all be capable of understanding it. I will make an assertion.

Bob: Here goes.

Roxana: Do not interrupt.

Bob: I was always the one talking at the back of the class.

Zac: Don’t worry about Bob, Roxana. We’d all love to hear your assertion. Silence, please, everyone.

Roxana: Samarkand is in Uzbekistan.

Sarah: Is that it?

Roxana: That was the assertion.

Bob: So that’s where Samarkand is. I always wondered.

Roxana: Concentrate on the logic, not the geography. In making that assertion about Samarkand, I speak truly if, and only if, Samarkand is in Uzbekistan. I speak falsely if, and only if, Samarkand is not in Uzbekistan.

Zac: Is that all, Roxana?

Roxana: It is enough.

Bob: I think I see. Truth is telling it like it is. Falsity is telling it like it isn’t. Is that what Aristotle meant?

Roxana: That paraphrase is acceptable for the present.

Have you got something you want to say to Roxana? Do you agree or disagree with her? Tetralogue author Timothy Williamson will be getting into character and answering questions from Roxana’s perspective via @TetralogueBook on Friday 20th March from 2-3pm GMT. Tweet your questions to him and wait for Roxana’s response!

The post Trains of thought: Roxana appeared first on OUPblog.

February 15, 2015

Getting to know Alan Goldberg, Demand Planner

From time to time, we try to give you a glimpse into our offices around the globe. This week, we are excited to bring you an interview with Alan Goldberg on our Demand Planning team in New York. Alan has been working at the Oxford University Press since March 2014.

What drew you to work for OUP in the first place? What do you think about that now?

I wanted to stay within publishing and I knew how prestigious the Oxford name is. I still feel that way.

What are the biggest changes you’ve seen in the publishing industry since working at OUP?

Digital. It’s why I got laid off from Google/Zagat. Depending on who you talk to, print is either dead, dying, or in its death throes. From my chair, print is doing pretty well for itself.

If you didn’t work in publishing, what would you be doing?

I would like to work in music for either Rhino Music or Trojan Records.

Tell us about one of your proudest moments at work.

I don’t remember when it was exactly, but I was fairly new. My boss said, “you are diligent, pragmatic, and dedicated. You fit right in!”

What is the strangest thing currently on or in your desk?

Would a sponge be strange? I have a sponge in a shallow bowl to wash my dishes. I don’t do communal sponges (I’m a tad germaphobic.).

Alan Goldberg

Alan Goldberg What are you reading right now?

Sonic Youth’s Daydream Nation by Michael Stearns. It’s in the 33 1/3 series.

What’s your favorite book?

It’s tough picking one favorite. The Roald Dahl Omnibus came to mind.

Open the book you’re currently reading and turn to page 75. Tell us the title of the book, and the third sentence on that page.

“But at one point we were playing a show at CBGB’s, a punk matinee show.” (Sonic Youth’s Daydream Nation, Michael Stearns)

If you could trade places with any one person for a week, who would it be and why?

I would love to know what it is like to be as creative as Robert Pollard. For the past 25+ years, the man has written well over 1,000 songs.

If you were stranded on a desert island, what three items would you take with you?

A satellite phone so someone can rescue me!

What is your favorite word?

Gherkin. I like how it sounds.

What is in your desk drawer?

Office supplies, over the counter medications and plenty of napkins!

Most obscure interest/hobby?

Perhaps my taste in music. I enjoy indie rock, heavy metal (like thrash metal, death metal, etc), ska and reggae from the 1960’s and 70’s, classic country, soul and rock. I can appreciate a band like Entombed as well as Toots & the Maytals.

Longest book ever read?

For Whom The Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway.

Favorite animal?

French bulldog.

The post Getting to know Alan Goldberg, Demand Planner appeared first on OUPblog.

Choosing a president in a new democracy: lessons from Eastern and Central Europe

In his famous statement about the perils of presidentialism, Juan Linz argued that newly emerging democracies ought to avoid adopting a presidential form of government. One of Linz’s reasons had to do with the winner-take-all-nature of presidential elections. By definition, such elections are zero-sum games where the losing candidates have little to no prospect of sharing in executive power. By having a single indivisible and powerful executive office, presidential elections amplify the gap between winning and losing, and can contribute to creating and deepening political divisions, which is precisely what a new democracy ought to minimize.

At the same time, having the people elect the head of their state directly can strengthen the legitimacy of the democratic foundations of the new constitutional order. When conducted in a fair, free, and transparent manner observing the highest standards of electoral integrity, direct presidential elections can play an important role in aiding the development of civic and political values such as electoral participation, competitiveness, and accountability. If the population is not imbued by such values, the new democratic system may soon hollow out and become a procedural mechanism with no substantive values informing and guiding it.

An intermediate constitutional solution is the adoption of a semi-presidential system of government, which, according to scholars like Maurice Duverger and Robert Elgie, is characterized by a presidency that is elected directly by the people but that is also considerably weaker in power and authority than the chief executive of a presidential system of government. The relative weakness of the semi-presidential head of state is underscored by the fact that the office shares executive power with the prime minister who, as the head of government, is responsible to the legislature. Semi-presidentialism often becomes an attractive constitutional choice in new democracies precisely because it has the advantage of encouraging popular participation in the political system without concentrating too much power in a single executive office.

Budapest Parliament by Mike Gabelmann. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr

Budapest Parliament by Mike Gabelmann. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr The experience of the ten post-communist democracies in Eastern and Central Europe is an excellent case in point. At the time of their transition to democracy in the early 1990s, only half of the ten states had a semi-presidential executive: Bulgaria, Lithuania, Poland, Slovenia, and Romania. The remaining five states (the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, and Slovakia) remained parliamentary systems with both the prime minister and the president elected by the legislature. By 2015 Hungary, Estonia, and Latvia have remained the only three cases with indirectly elected heads of state. At first Slovakia, in 1998, and then the Czech Republic, in 2012, enacted constitutional changes to move from indirect to direct presidential elections. In both of these cases, the adoption of direct presidential elections was the result of repeated failures by parliament to ensure a smooth and efficient process. In Slovakia, the National Council was unable to elect a president after several unsuccessful rounds of balloting in 1998, whereas in the Czech Republic both the 2003 and the 2008 elections were characterized by legislative tumult leading to renewed calls for delegating the choice of president to the people.

What can constitutional designers and engineers learn from the history of presidential elections in the post-communist region? Insofar as political stability and legitimacy are concerned, there are three important lessons:

The semi-presidential model is a reliable and good constitutional choice as long as the formal powers of the head of state are kept modest. Some of the most serious constitutional battles between a directly elected president and the legislature took place in the three states where the head of state had the greatest formal powers (Lithuania, Poland, and Romania). However, while subsequent constitutional changes in these states modified the term or the powers of the president, none of them did away with the directly elective nature of the office. Indirect presidential elections can be a major source of political instability, and loss of public trust in the legislature, unless the rules of the game are kept efficient. The examples of Slovakia and the Czech Republic showed that inclusive and consensus-oriented rules do not work in the long run. In both cases, the constitution required that the winning candidate obtain a highly qualified majority of votes, which proved to be extremely difficult, or even impossible, in an already fragmented multi-party parliament. Efficient rules for indirect presidential elections ought to combine a simple majority threshold for winning with a fixed number of rounds in which the election must be completed. As the cases of Hungary and Estonia show, efficient rules will typically favor the candidate of the incumbent governing coalition and as such will further concentrate executive power in its hands. However, this may be a small price to pay relative to the instability that can be caused by the failure of consensus-oriented inclusive rules.In short, the post-communist cases suggest that the ideal form of choosing the president of a new democracy may be either direct election by the people or indirect election by parliament using efficient, result-oriented rules and procedures. While presidentialism as a constitutional system may be perilous for the stability of a new democracy, as Juan Linz argued, there is also a great danger in adopting parliamentary processes of presidential election which can themselves become the source of political instability.

The post Choosing a president in a new democracy: lessons from Eastern and Central Europe appeared first on OUPblog.

The 10 best shows for music directors, in no particular order, for several reasons

Listing the ten best shows for a music director to work on is as subjective as choosing the ten greatest composers, or painters, or novelists, so it’s worthwhile to stipulate some qualities the winners must have, subjectively speaking. Yet these qualities can only reveal themselves by working through the reasoning of what makes a show a music director’s favorite.

Of the many musicals I’ve attended in recent years, among the most enjoyable and perhaps the funniest was Monty Python’s Spamalot. The music cues come fast and furious, and in all varieties, from classical quodlibets to Spike Jones-like punctuations–a true challenge for the music director to keep up and maintain the comic timing. Yet despite such diversity of style, despite the expertise of the orchestrations, regardless of the virtuosity of the players in the pit, the music is so fully integrated into the fabric of the comedy that it almost ceases to have a discrete identity of its own. It acts more as laugh-enhancer to the goings-on onstage.

Are the shows that music directors are partial to leading from the podium perhaps not the best ones to view from the house as an audience member or critic? Most music directors, it seems, prefer directing musical material with its own distinction.

That’s why many readers are probably expecting the top of this list to be occupied by the musical jewels that always seem to outshine the rest, and are likely the offhanded choices of just about any music-director-on-the-street you might ask: West Side Story, Sweeney Todd, South Pacific, Cabaret, Guys and Dolls, Gypsy, Fiddler… And isn’t it interesting that as the list continues, that the best scores seem to coincide with the best stories; they are inseparably connected to the best musical theater works, the best overall entertainments. A great book marks the finest examples of the form, and great scores masterfully accompany these great stories or themes, just as Spamalot’s does. There have been many excellent, crafty scores alongside librettos that have not sufficiently engaged their audiences–and those shows have rarely succeeded–but seldom has there been a great musical without an outstanding score.

For a music director, it’s about the sparks that fly when music and drama collide and collaborate; that’s what makes the job exciting. Therefore, I will, after all, include Spamalot among my top ten, for the same reasons I cited above to argue against it. It seems impossible that the music director-conductor of that show could ever get bored in performance, what with the variety of musical involvement, and the charming music is very much a part of the outrageous humor.

Stephen Sondheim on piano with Leonard Bernstein and Carol Lawrence (on far right) standing amongst female singers rehearsing for the stage production West Side Story, 1957. Copyright: The New York Public Library. NYPL Digital Collections.

Stephen Sondheim on piano with Leonard Bernstein and Carol Lawrence (on far right) standing amongst female singers rehearsing for the stage production West Side Story, 1957. Copyright: The New York Public Library. NYPL Digital Collections. And yes, the great scores (some, but not all of them–I’ll tell you why in a moment) belong on the list, if for no other reason than the pure musical satisfaction they provide music directors. West Side Story is there because, well, because the score is not only unthinkably beautiful and profoundly interesting, but is also a seminar on music theory and composition. Sweeney Todd, too, because nothing can touch that unique sound, that combination of dark and light, the stuff that waves of goosebumps are made of. Both of these scores are also musically challenging for all involved: singers, musicians, and music directors. On the other hand, though you may adore a lush, sophisticated work such as The Most Happy Fella or The Bridges of Madison County, you might be prone to disconnecting from the emotional content, which are diluted by threadbare (albeit emotional) story lines. Instead, I’ll include something comparably original and musically intelligent, Carousel, which though certainly corny by today’s standards, is still a marvel of lyricism, and of connection of music to story. I’m sure many readers would want to add their own favorites in its slot.

Music directors covet music with “groove,” especially since groove began to dominate popular music in the mid-20th century. Nothing is more satisfying than rocking out with a great band in front of an audience that is really into the proceedings. Perhaps the deepest grooves in musical theater history have belonged to a handful of authentically rock/pop shows–among them Hedwig and the Angry Inch, Rocky Horror, Mamma Mia!, Tommy, Rent, Jesus Christ Superstar, Spring Awakening, In The Heights, and now Hamilton. I’ll disqualify Tommy and Heights due to my bias as an alumnus of their Broadway productions. Hedwig is a whole different animal, with its onstage band and few songs; Mamma Mia! has a silly story; and Spring Awakening’s music direction is subtle and overshadowed by its remarkable staging and storytelling, so let’s just narrow the list down to Rent and Superstar. I give the nod to Jesus Christ Superstar because its music calls upon all the influences of its time–rock, R&B, blues, psychedelia, etc.–while retaining a true classical heart and a tenacious theatrical bent. It’s nearly through-composed, and the conductor plays keyboards, keeping him or her busily occupied throughout. Almost all of this is true of Rent too, so let’s keep them both on the list.

As for onstage bands: Ain’t Misbehavin’ or Smokey Joe’s Cafe. Both are a just a gas to lead, the music director gets to show off at the piano a bit, and the spirit and music of the shows tend to evince stellar performances from their singers and players, as well as rowdy approval from audiences. Take your pick; it’s a tossup.

Let’s add shows that get better the more you view them. The Music Man, for example, has brilliant construction, sharp characterizations, and a glorious score, featuring intricate melodic connections and spectacular dance arrangements. And because they so epitomize the musical theater form, it’s almost impossible to exclude A Chorus Line or Chicago. I’m choosing A Chorus Line on the list because of its scant 100 minute duration (no intermission), which for working stiffs, gets many music directors home at a quite reasonable hour. (I was also tempted to include Little Shop of Horrors for this reason, and because it is a brilliantly crafted musical with a great, grooving score, but again, as an alum of the original production, I am biased.)

Any show that you yourself help to arrange or create as music director, any show that you truly care for, is probably your darling. It could be the show you arranged for your local theater club, or a revue you did with your favorite singer. Shows that you work hard on get under your skin, into your soul, and never leave you. Nine years after departing Broadway’s The Lion King, I still have Lion King ear worms.

Any of the shows I list might be compromised by an irresponsibly reduced orchestration, or an unjustifiable or unattractive synthetic musical element. I am considering them are their ideal, pristine, original or very-close-to-it versions. So here they are, in an order that I will change countless times after posting this blog article:

10. Rent

9. Spamalot

8. Carousel

7. A Chorus Line

6. The Music Man

5. Tie: Ain’t Misbehavin’ and Smokey Joe’s Cafe

4. Jesus Christ Superstar

3. Sweeney Todd

2. West Side Story

1. Your own personal Lion King, whatever it may be–the show that is closest to your heart.

Headline Image: Music Notes. CC0 Public Domain License via Pixabay

The post The 10 best shows for music directors, in no particular order, for several reasons appeared first on OUPblog.

February 14, 2015

Why green growth?

There is universal acknowledgment of the fact that India needs to come back on the path of high economic growth quickly. Although GDP grew at an unprecedented annual average rate of growth of almost 7.7% during the past decade (the highest for any democracy in the world), the last two years have been disappointing. High economic growth rates fuelled by high rates of investment are essential because they generate huge revenues for the government, which can then be utilised for social welfare and infrastructure expansion programmes. Of course, it goes without saying that rapid growth alone is not enough. It must be of a nature that creates increasing productive employment opportunities and it must be inclusive as well so that more and more sections of society benefit visibly and tangibly from it.

There is a yet another dimension to economic growth, in addition to its being rapid and inclusive. And this is that economic growth has to be ecologically sustainable as well. India simply cannot afford the “grow now, pay later” model that has been adopted by most other countries, including China and Brazil. This is for at least four pressing reasons.

First, no country is going to add another 40-50 crore to its current population of about 124 crore by the middle of this century as India is destined to do. (By contrast, China will add just about 2.5 crore over the same period to its current population of about 150 crore.) We cannot compromise the prospects for our coming generations by our impatience and greed today.

Second, there is no country that faces the type of multiple vulnerabilities to climate change, both current and future as India does. This is because of its dependence on the monsoon, its very large population living in coastal areas who are vulnerable to increase in mean sea levels, its reliance on the health of the Himalayan glaciers for water security, and its preponderance of extractable natural resources like coal and iron ore in dense forest areas (more extraction means more deforestation that aggravates climate change).

Third, environment is increasingly becoming a public health concern. From unprecedented industrial and vehicular pollution to the dumping of chemical waste and municipal sewage in rivers and water-bodies, the build up to a public health catastrophe is already visible. People are already suffering in a variety of ways and environmental deterioration has emerged as a major cause of illness.

Darjeeling, 29 April 2007. photo by Shreyans Bhansali. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via thebigdurian Flickr.

Darjeeling, 29 April 2007. photo by Shreyans Bhansali. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via thebigdurian Flickr.Fourth, most of what is called environmentalism in India is not middle class “lifestyle environmentalism” but actually “livelihood environmentalism” linked to daily issues of land productivity, water availability, access to non-timber forest produce, protection of water-bodies, protection of grazing lands and pastures, preservation of sacred places, etc.

Environmental concerns are, therefore, not part of some foreign plot or conspiracy by some NGOs to keep India in a state of perpetual poverty. It is an imperative we ignore at our own peril. It is not just a matter of increasing the contribution of renewables to our energy supply. Much more important are investment and technology choices in industry, agriculture, energy, transport, construction, and other sectors of the economy. In April 2014, the Planning Commission’s expert on low carbon strategies for inclusive growth submitted its final report. In the debate on the future of the Planning Commission, this report vital to our future has unfortunately been ignored. The report concludes on the basis of its detailed sectoral analysis that low carbon inclusive growth is not just desirable but is also eminently feasible even though it will require additional investments.

The Modi government, like its predecessors, has stressed its resolve to integrate environmental concerns into the mainstream of the process of economic growth. This is admirable but we must recognise that at times there will be trade-offs between growth and environment, occasions when tough choices will necessarily have to be made — choices that may well involve saying “no”. It is when you work the integration in practice, that you confront contradictions, complexities, and conflicts that cannot be brushed aside. They have to be recognised and managed sensitively as part of the democratic process.

The debate is really not one of environment versus development but really be one of adhering to rules, regulations, and laws versus taking the rules, regulations ,and laws for granted? When public hearings means having hearings without the public and having the public without hearings, it is not a environment versus development issue at all. When an alumina refinery starts construction to expand its capacity from one million tons per year to six million tons per year without bothering to seek any environmental clearance as mandated by law, it is not a “environment versus development” question, but simply one of whether laws enacted by Parliament will be respected or not. When closure notices are issued to distilleries or paper mills or sugar factories illegally discharging toxic wastes into India’s most holy Ganga river, it is not a question of “environment versus development” but again one of whether standards mandated by law are to be enforced effectively or not. When a power plant wants to draw water from a protected area or when a coal mine wants to undertake mining in the buffer zone of a tiger sanctuary, both in contravention of existing laws, it is not a “environment versus development” question but simply one of whether laws will be adhered to or not.

By all means we must make laws pragmatic. By all means we must have market-friendly means of implementing regulations. By all means, we must accelerate the rate of investment in labour-intensive manufacturing especially. But mockery should not be made of regulations and laws. Indian civilisation has always shown the highest respect for biodiversity. Therefore, it should not be difficult for us to become world leaders in green growth. This is an area of strategic leadership where India can show the way to the world. Both the champions of “growth at all costs” and the crusaders for ecological causes must work together to enable India to attain this position.

Headline image credit: Between Sissu and Keylong, Manali-Leh Highway, Himachal Pradesh, Indian Himalayas. Photo by Henrik Johansson. CC BY-NC 2.0 via henrikj Flickr.

The post Why green growth? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers