Oxford University Press's Blog, page 705

February 3, 2015

Selma and re-writing history: Is it a copyright problem?

A few days ago The Hollywood Reporter featured another interesting story concerning Martin Luther King or – to be more precise – his Martin Luther King leaning on a lectern, 1964. Public domain via Library of Congress.

There is fairly abundant case law on fair use as applied to biographies. With particular regard to the re-creation of copyright-protected works (as it would have been the case of Selma, should Oyelowo/King had reproduced actual extracts from King’s speeches), it is worth recalling the recent (2014) decision of the US District Court for the Southern District of New York in Arrow Productions v The Weinstein Company.

This case concerned Deep Throat‘s Linda Lovelace biopic, starring Amanda Seyfried. The holders of the rights to the “famous [1972] pornographic film replete with explicit sexual scenes and sophomoric humor” claimed that the 2013 film infringed – among other things – their copyright because three scenes from Deep Throat had been recreated without permission. In particular, the claimants argued that the defendants had reproduced dialogue from these scenes word for word, positioned the actors identically or nearly identically, recreated camera angles and lighting, and reproduced costumes and settings.

The court found in favour of the defendants, holding that unauthorised reproduction of Deep Throat scenes was fair use of this work, also stressing that critical biographical works (as are both Lovelace and Selma) are “entitled to a presumption of fair use”.

In my opinion reproduction of extracts from Martin Luther King’s speeches would not necessarily need a licence. It is true that the fourth fair use factor might weigh against a finding of fair use (this is because the Martin Luther King estate has actually engaged in the practice of licensing use of his speeches). However the social benefit in having a truthful depiction of King’s actual words would be much greater than the copyright owners’ loss. Also, it is not required that all four fair use factors weigh in favour of a finding of fair use, as recent judgments, e.g. Cariou v Prince or Seltzer v Green Day, demonstrate. Additionally, in the context of a film like Selma in which Martin Luther King is played by an actor (not incorporating the filmed speeches actually delivered by King), it is arguable that the use of extracts would be considered highly transformative.

In conclusion, it would seem that in principle that US law would not be against the reproduction of actual extracts from copyright-protected works (speeches) for the sake of creating a new work (a biographic film).

This article originally appeared on The IPKat in a slightly different format on Monday 12 January 2015.

Featured image credit: Dr. Martin Luther King speaking against war in Vietnam, St. Paul Campus, University of Minnesota, by St. Paul Pioneer Press. Minnesota Historical Society. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Selma and re-writing history: Is it a copyright problem? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA brief history of Data Privacy Law in AsiaState responsibility and the downing of MH17Bob Hope, North Korea, and film censorship

Related StoriesA brief history of Data Privacy Law in AsiaState responsibility and the downing of MH17Bob Hope, North Korea, and film censorship

February 2, 2015

An estate tax increase some Republicans might support

In his State of the Union address, President Obama proposed several tax increases aimed at affluent taxpayers. The President did not suggest one such increase that some Republicans might be persuaded to support: limit the estate tax deduction for bequests to private foundations. In light of the significant economic and political power wielded by the families which control such foundations, it is compelling to limit the estate tax charitable deduction for bequests to such foundations.

As I discuss in a recent paper in the Florida Tax Review, the federal estate tax charitable deduction is unlimited. In contrast, the federal income tax charitable deduction includes detailed limitations which restrict the proportion of an individual taxpayer’s income which may be deducted as a charitable contribution. Through these limits, the income tax charitable deduction implements the ethic that everyone – even taxpayers who devote their entire incomes to charity – should pay some federal income tax.

The federal estate tax should be amended to similarly restrict an estate’s charitable deduction to a percentage of the estate. Then, every estate large enough to trigger federal estate liability would pay some estate tax, even if that estate devolves in its entirety upon charitable recipients.

In the current political environment, this change does not seem feasible. However, it might be possible to garner bi-partisan support for a less sweeping reform, namely, an estate tax charitable deduction limit only applicable to bequests to private foundations.

On the one side are the policy of encouraging charitable bequests to maintain a vibrant charitable sector and the recognition that resources transferred to charity do not directly descend to the decedent’s family. On the other hand, the public fisc has legitimate claims for the services it provided during the decedent’s lifetime. The estate tax is the final accounting for the governmental benefits the decedent received while alive. Most importantly, bequests to a private foundation often, in dynastic fashion, perpetuate substantial economic and political power for the decedent’s family which controls that foundation.

Many private foundations are admirable institutions. I am a fan of the Gates Foundation and of the Buffett family’s charitable efforts. These private foundations appear to be well run, genuinely charitable enterprises.

However, other private foundations are considerably less commendable. Such foundations often serve the thinly-disguised political and economic interests of the families controlling them. Even laudable foundations, like the Gates and Buffett foundations, entail considerable political and financial power for the Gates and Buffett families.

William Gates, Sr., is an attorney and a leader of Responsible Wealth, a coalition of wealthy individuals who favor a federal estate tax. Attorney Gates has written eloquently of the need for federal estate taxation. Few, if any, Republicans will join his call for retaining the federal estate tax.

But some Republicans may be concerned about the realities of private foundations. Looking at these realities, Republicans and Democrats might agree that the estate tax charitable deduction should be limited for bequests to private foundations including the Gates and Buffett families’ foundations.

Image Credit: “Tax.” Photo by Alan Cleaver. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post An estate tax increase some Republicans might support appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCongress should amend and enact the Marketplace Fairness Act“Lame Duck” session of Congress should pass Multi-State Worker Tax Fairness ActThe parsonage allowance and standing in the state courts

Related StoriesCongress should amend and enact the Marketplace Fairness Act“Lame Duck” session of Congress should pass Multi-State Worker Tax Fairness ActThe parsonage allowance and standing in the state courts

Groundhogs are more than just prognosticators

February 2nd marks Groundhog Day, an annual tradition in which we rouse a sleepy, burrowing rodent to give us winter-weary humans the forecast for spring. Although Punxsutawney Phil does his best as an ambassador for his species, revelers in Gobbler’s Knob and elsewhere likely know little about the true life of a wild groundhog beyond its penchant for vegetable gardens and large burrow entrances. In celebration of the only mammal to have its own holiday, I share with you eight lesser-known facts about groundhogs.

1. Groundhogs, whistlepigs, woodchucks, all names for the same animal. Depending on where you live, you might have heard all three of these names; however, woodchuck is the scientifically accepted common name for the species, Marmota monax. As the first word suggests, the woodchuck is a marmot, a genus comprised of 15 species of medium-sized, ground-dwelling squirrels. Although woodchucks are generally solitary and live in lowland areas, most marmot species live in social groups in mountainous parts of Europe, Asia, and North America.

2. How much wood would a woodchuck chuck? As a biologist who studies woodchucks, this is the number one question I am asked about my study species. To set the record straight, woodchucks do not actually chuck wood! In fact, the name “woodchuck” is actually thought to derive from the Native American word for the animal, not because of the species’ association with wood. Although they may chew or scent mark on woody debris near their burrows, they do not cut down trees (unlike their cousin, the American beaver, Castor canadensis).

3. Woodchucks are the widest-ranging marmot, and are able to adjust to a variety of habitats and climates to survive. Woodchucks are found in wooded edges, agricultural fields, residential gardens, and suburban office parks as far north as Alaska, eastward throughout Canada, and as far south as Alabama and Georgia. The weather extremes of these areas range from subzero winters to scorching summers, thus woodchucks must employ unique physiological strategies to survive. Woodchucks are considered urban-adapters because of their ability to live around humans by taking advantage of anthropogenic food sources such as garden landscaping and managed vegetation.

“Groun[d]hog Day from Gobbler’s Knob in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania.” Photo by Anthony Quintano. CC by 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“Groun[d]hog Day from Gobbler’s Knob in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania.” Photo by Anthony Quintano. CC by 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.4. Woodchucks are considered the largest true-hibernators. As herbivores, woodchucks have very little to eat during the winter months when most vegetation has died. To save energy during the winter, woodchucks hibernate. The timing of this slowdown is thought to depend partly on photoperiod, which varies by latitude. They generally seek hibernacula under structures or in wooded areas protected from wind. Prior to hibernating, a woodchuck will go in and out of the burrow for a few days to a few weeks, foraging to build up fat stores until entering one last time to plug the burrow entrance behind them with leaves and debris. As a true hibernator, the body temperature of a woodchuck can drop to just a few degrees above that of the burrow, their breathing decreases, and their heart rate slows to around 10 beats per minute. Although they rarely exit the burrow, hibernating woodchucks awake every 10 days or so, hang out in their burrows, and then go back sleep after a few days. The length of the hibernation season can range from just 75 days, to over 175 days, depending on their location. They emerge in early spring, and generally breed soon after.

5. Woodchucks dig complex underground burrow systems, in which they rest, rear young, and escape from predators. If you are a homeowner who has had a woodchuck on your property, you are probably familiar with the large and numerous holes that woodchucks dig in the ground. These many entrances are used as “escape hatches” for a woodchuck to quickly go underground at the first sign of a threat. As escape is their best line of defense, rarely will a woodchuck forage more than 20 meters from a burrow entrance. Underground, burrow systems are comprised of multiple tunnels, some up to 13 meters in length and over 2 meters deep, that lead to multiple chambers, including bedroom chambers, and even a latrine burrow (woodchucks rarely defecate above ground to avoid attracting predators). Based on our research, woodchucks can use up to 25 different burrow systems, likely moving around to avoid predators, look for mates, and find new foraging spots.

6. Woodchucks can swim and climb trees. Although their portly body shape does not suggest agility, woodchucks can move quickly when they really need to. To avoid predators, woodchucks are able to swim short distances across creeks and drainage ditches, and are able to climb trees. They have even been spotted on rooftops and on high branches of mulberry trees, foraging on berries.

7. Woodchucks vocalize. The origin of the name “whistle pig” comes from the high-pitched, loud whistle woodchucks emit when threatened, likely to warn offspring or other adults of an approaching predator. In addition to the whistle, woodchucks will chatter their large incisors as a threatening reminder of the strength of their bite.

8. Woodchucks are easy to observe. My favorite characteristic about woodchucks is that their size (about the size of a house cat) and daytime activity patterns make them easy to observe. Unlike most mammals, you can easily spot them foraging in open fields and roadsides and they generally will tolerate the presence of humans at a distance. If you live in the woodchuck’s native range, keep your eyes peeled for these large squirrels, grab your binoculars, and take a minute to watch them forage and vigilantly observe their environment. It’s a fun way for kids and adults alike to test their skills as a wildlife biologist!

Image Credit: “Groundhog.” Photo by Matt MacGillivray. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Groundhogs are more than just prognosticators appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesState responsibility and the downing of MH17Kin selection, group selection and altruism: a controversy without end?The Vegetarian Plant

Related StoriesState responsibility and the downing of MH17Kin selection, group selection and altruism: a controversy without end?The Vegetarian Plant

State responsibility and the downing of MH17

Two hundred and ninety-eight passengers aboard Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 were killed when Ukrainian rebels shot down the commercial airliner in July 2014. Because of the rebels’ close ties with the Russian Republic, the international community immediately condemned the Putin regime for this tragedy. Yet, while Russia is certainly deserving of moral and political blame, what is less clear is Russian responsibility under international law. The problem is that international law has often struggled assigning state responsibility when national borders are crossed and two (or more) sovereigns are involved. The essence of the problem is that under governing legal standards, a state could provide enormous levels of military, economic, and political support to another state or to a paramilitary group in another state – even with full knowledge that the recipient will thereby violate international human rights and humanitarian law standards — but will not share any responsibility for these international wrongs unless it can be established that the sending state exercised near total control over the recipient.

The leading caselaw in this area has been handed down by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) but what adds another layer of complexity to the present situation is that the Ukraine and Russia are both parties to the European Convention; it is possible that the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) might well provide a different answer.

To be clear, this article concerns itself only with determining Russian responsibility for the downing of MH17. Following this tragic event, approximately five thousand Russian troops took part in what now appears to have been a limited invasion of areas of the Ukraine. Thus, there are elements of both “indirect” and “direct” Russian involvement in the Ukraine, although only the former will be addressed. The larger point involves the legal uncertainty when states act outside their borders and in doing so contribute to the violation of international human rights standards.

International Court of Justice

The two leading cases regarding transnational or extraterritorial state responsibility have been handed down by the International Court of Justice. In Nicaragua v. United States (1986) Nicaragua brought an action against the United States based on two grounds. One related to “direct” actions carried out by US agents in Nicaragua, including the mining of the country’s harbors, and on this claim the Court ruled against the United States. The second claim was based on the “indirect” actions of the United States, namely, its support for the contra rebels who were trying to overthrow the ruling Sandinista regime. Nicaragua’s argument was that because of the very close ties between the United States and the contras, the former should bear at least some responsibility for the massive levels of human rights violations carried out by the latter.

The Court rejected this position employing an “effective control” standard, which in many ways is much closer to an absolute control test. Or to quote from the Court itself: “In light of the evidence and material available to it, the Court is not satisfied that all the operations launched by the contra force, at every stage of the conflict, reflected strategy and tactics wholly devised by the United States” (par. 106, emphases supplied).

Nearly a decade later, the International Court of Justice was faced with a similar scenario in the Genocide Case (Bosnia v. Serbia). The claim made by Bosnia was that because of the deep connections between the Serbian government and its Bosnian Serb allies, the former should have some responsibility for the acts of genocide carried out by the latter. Yet, as in Nicaragua, the ICJ ruled that Serbia had not exercised the requisite level of control over the Bosnian Serbs. Thus, the Court ruled that Serbia was not responsible for carrying out genocide itself, or for directing genocide, or even for “aiding and assisting” or “complicity” in the genocide that occurred following the overthrow of Srebrenica. However, in a part of its ruling that has received far too little attention, the Court did rule that Serbia had failed to “prevent” genocide when it could have exercised its “influence” to do so, and that it had also not met its Convention obligation to “punish” those involved in genocide due to its failure to fully cooperate with the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia.

Perevalne, Ukraine – March 4, 2014: Russian soldier guarding an Ukrainian military base near Simferopol city. The Russian military forces invaded Ukrainian Crimea peninsula on February 28, 2014. © AndreyKrav via iStockphoto

Perevalne, Ukraine – March 4, 2014: Russian soldier guarding an Ukrainian military base near Simferopol city. The Russian military forces invaded Ukrainian Crimea peninsula on February 28, 2014. © AndreyKrav via iStockphotoTurning back to the situation involving MH17, while no action has yet been filed with the International Court of Justice (and perhaps never will be filed), according to the Nicaragua-Bosnia line of cases any attempt to hold Russia responsible for the downing of MH17 would appear likely to fail for the simple reason that the relationship between the Russian state and its Ukrainian allies was nowhere near as strong as the relationship between the United States and the contras (Nicaragua) or that between the Serbian government and its Bosnian Serb allies (Genocide Case). The point is that if responsibility could not be established in these other cases it is by no means likely that it could be established in the present situation.

European Court of Human Rights

Because Russia and the Ukraine are both parties to the European Convention of Human Rights, what also needs to be considered is how the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) might address this issue if a case were brought either under the inter-state complaint mechanism, or (more likely) by means of an individual complaint filed by a family member killed in the crash.

Although the European Court of Human Rights has increasing dealt with cases with an extraterritorial element, in nearly every instance the claim has been based on European states carrying out “direct” actions in other states – whether it be NATO forces dropping bombs in Serbia and killing civilians on the ground (Bankovic), or Turkish officials arresting a suspected terrorist in Kenya (Ocalan), or British troops killing civilians in Iraq (Al-Skeini) – rather than instances where the Convention states have acted “indirectly.” The most pertinent ECtHR case is Ilascu v. Russia and Moldova where the applicants (Moldovan citizens) claimed they were arrested at their homes in Tiraspol by security personnel, some of whom were wearing the insignia of the former USSR. Unlike the ICJ’s “effective control” standard, the ECtHR ruled that Russia had exercised what it termed as “effective authority” or “decisive influence” over paramilitary forces in Moldova and because of this they bore responsibility for violations of the European Convention suffered by the applicants. Thus, on the basis of Ilascu, there is at least some possibility that due to the “effective authority” or the “decisive influence” that Russia appeared to exercise over its Ukrainian rebel allies, the ECtHR, unlike the ICJ, could assign responsibility to Russia for the downing of MH17.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding the immediate international condemnation of the Putin regime following the MH17 tragedy, international law seems to exist in a totally removed from international opinion and consensus. Under the caselaw of the International Court of Justice, Russia would appear not to be responsible for the downing of MH17 on the basis that it would be difficult to establish that the Russian government had exercised the requisite level of “effective control” over its Ukrainian rebel allies. On the other hand, if a case were brought before the European Court of Human Rights, there is at least some chance of establishing Russian responsibility on the basis of the Court’s previous ruling in Ilascu, although it should be said that this is not a particularly strong precedent.

The larger point is to ask why state responsibility is so difficult to establish when international borders are crossed and states act in another country, at least indirectly, as in the present situation. The key element ought to be the extent to which a state has acted in a way that leads to violations of international human rights and humanitarian law standards. Employing such a standard, it would be eminently clear – would it not? – that Russia would be at least partly responsible because of its strong relationship with Ukrainian rebels that were both armed (by Russia) and dangerous, and which had already shown a complete disregard for international law.

The post State responsibility and the downing of MH17 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEssential considerations for leadership in policing (and beyond)Judicial resistance? War crime trials after World War IKin selection, group selection and altruism: a controversy without end?

Related StoriesEssential considerations for leadership in policing (and beyond)Judicial resistance? War crime trials after World War IKin selection, group selection and altruism: a controversy without end?

Trains of thought: Bob

Tetralogue by Timothy Williamson is a philosophy book for the commuter age. In a tradition going back to Plato, Timothy Williamson uses a fictional conversation to explore questions about truth and falsity, knowledge and belief. Four people with radically different outlooks on the world meet on a train and start talking about what they believe. Their conversation varies from cool logical reasoning to heated personal confrontation. Each starts off convinced that he or she is right, but then doubts creep in. During February, we will be posting a series of extracts that cover the viewpoints of all four characters in Tetralogue. What follows is an extract exploring Bob’s perspective.

Bob is just an ordinary guy who happens to be scared of witches. His beliefs are strongly rooted in personal experience, and this approach brings him to blows with the unyelidingly scientific Sarah.

Sarah: That’s unfair! You don’t expect all the scientific resources of the Western world to be concentrated on explaining why your garden wall collapsed, do you? I’m not being dogmatic, there’s just no reason to doubt that a scientific explanation could in principle be given.

Bob: You expect me to take that on faith? You don’t always know best, you know. I’m actually giving you an explanation. (Mustn’t talk too loud.) My neighbour’s a witch. She always hated me. Bewitched my wall, cast a spell on it to collapse next time I was right beside it. It was no coincidence. Even if you had your precious scientific explanation with all its atoms and molecules, it would only be technical details. It would give no reason why the two things happened at just the same time. The only explanation that makes real sense of it is witchcraft.

Sarah: You haven’t explained how your neighbour’s muttering some words could possibly make the wall collapse.

Bob: Who knows how witchcraft works? Whatever it does, that old hag’s malice explains why the wall collapsed just when I was right beside it. Anyway, I bet you can’t explain how deciding in my own mind to plant some bulbs made my legs actually move so I walked out into the garden.

Sarah: It’s only a matter of time before scientists can explain things like that. Neuroscience has made enormous progress over the last few years, discovering how the brain and nervous system work.

Bob: So you say, with your faith in modern science. I bet expert witches can already explain how spells work. They wouldn’t share their knowledge around. Too dangerous. Why should I trust modern science more than witchcraft?

Sarah: Think of all the evidence for modern science. It can explain so much. What evidence is there that witchcraft works?

Bob: My garden wall, for a start.

Sarah: No, I mean proper evidence, statistically significant results of controlled experiments and other forms of reliable data, which science provides.

Bob: You know how witches were persecuted, or rightly punished, in the past. Lots of them were tortured and burnt. It could happen again, if they made their powers too obvious, doing things that could be proved in court. Do you expect them to let themselves be trapped like that again? Anyway, witchcraft is so unfashionable in scientific circles, how many scientists would risk their academic reputations taking it seriously enough to research on it, testing whether it works?

Sarah: Modern science has put men on the moon. What has witchcraft done remotely comparable to that?

Bob: For all we know, that alleged film of men on the moon was done in a studio on earth. The money saved was spent on the military. Anyway, who says witchcraft hasn’t put women on the moon? Isn’t assuming it hasn’t what educated folk call ‘begging the question’?

Sarah: I can’t believe I’m having this conversation. Do you seriously deny that scientific journals are full of evidence for modern scientific theories? Isn’t all of that evidence against witchcraft?

Bob: How do we know how much of that so-called evidence is genuine? There have been lots of scandals recently about scientists faking their results. For all we know, the ones who get caught are only the tip of the iceberg.

Sarah: Well, if you prefer, look at all the successful technology around you. You’re sitting on a train, and I notice you have a laptop and a mobile phone. Think of all the science that went into them. You’re not telling me they work by witchcraft, are you?

Bob: Lots of modern science and technology is fine in its own way. I went to hospital by ambulance, not broom, thank goodness. None of that means modern science can explain everything.

Have you got something you want to say to Bob? Do you agree or disagree with him? Tetralogue author Timothy Williamson will be getting into character and answering questions from Bob’s perspective via @TetralogueBook on Friday 6th March from 2-3pm GMT. Tweet your questions to him and wait for Bob’s response!

The post Trains of thought: Bob appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThomas Aquinas and GodFree will, libertarianism, and luckFluorescent proteins and medicine

Related StoriesThomas Aquinas and GodFree will, libertarianism, and luckFluorescent proteins and medicine

February 1, 2015

A lifetime in the library

From regular after school browsing trips throughout primary school to attending Leamington Library’s book club as their youngest member, libraries have always provided me with a home away from home. In honour of the upcoming National Libraries Day (Saturday, 7 February 2015), I took a trip down memory lane to play tribute to some of the ways libraries have enriched and supported me.

My earliest memories of libraries include hours spent in the bright and cosy library in my primary school, and an even vaguer recollection of marvelling at the ingenuity of a travelling library dedicated to delivering books to residents of rural areas on the Isle of Mull.

While the libraries of my hometown (now sadly declined in number) were mundanely static by comparison, they more than made up for this with their content. A large format version of Janet and Allan Ahlberg’s picturebook Each Peach Pear Plum was an early favourite, and a few years later I enlisted my mum to give her approval so the librarians could issue me books from outside the children’s section.

“Free Library, Technical and Art School, Royal Leamington Spa.” Photo by David Stowell. CC by SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“Free Library, Technical and Art School, Royal Leamington Spa.” Photo by David Stowell. CC by SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Partly in emulation of Roald Dahl’s Matilda, I tackled my public library’s children’s summer reading challenges with gusto, determined not just to meet but to surpass the target of reading six books over the school holidays. The library offered a wide array of choices, introducing me to Japanese manga and providing reading material to satisfy a recurring graphic novel fixation, as well as ensuring I didn’t have to fork out for each installment in long-running series such as Lemony Snicket’s Series of Unfortunate Events.

As I progressed through school, libraries supported my research as well as entertainment needs. At 11, I was one of the few students in my class who looked forward to weekly ‘library lessons’. Among other research skills we were taught to understand and navigate the Dewey Decimal System, just one of the many methods of library classification I later found used in the libraries of Oxford University.

In library lessons it was the silent reading time at the end of each session, and the opportunity to withdraw a new book – especially if a new green box had arrived from the Warwickshire Schools Library Service – which I most eagerly awaited. Thanks to the efforts of my school librarian, for several years I was able to follow the Carnegie Medal, reading each book on the shortlist and voting in a local schools’ version of the award. It’s great to see this scheme still exists around the country, even offering schoolchildren the opportunity to meet shortlisted authors.

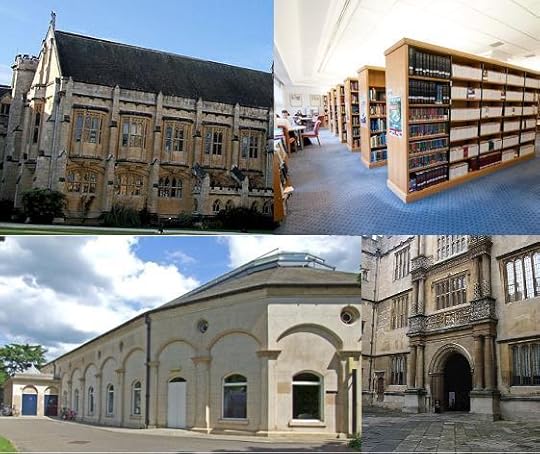

Clockwise: “Mansfield” (Photo by HiraV at the English language Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0), “OUP” (courtesy of Rachel Brook),”Pump Rooms” (Photo by Dennis Turner, CC BY-SA 2.0), “Courtyard of the Bodleian Library” (Photo by Zach A, CC BY 2.0) via Wikimedia Commons.

Clockwise: “Mansfield” (Photo by HiraV at the English language Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0), “OUP” (courtesy of Rachel Brook),”Pump Rooms” (Photo by Dennis Turner, CC BY-SA 2.0), “Courtyard of the Bodleian Library” (Photo by Zach A, CC BY 2.0) via Wikimedia Commons. I love libraries for a constantly growing list of reasons, including a commonplace appreciation for a quiet place to study or write, and an enthusiasm for cheap access to an impressively large and diverse DVD collection (thank you Oxford Central Library). Yet it’s the kindness and seemingly infinite knowledge of librarians that continues to make the most significant impact. From simply always knowing which books are shelved where, to generously loaning me a rare copy of Jane Austen’s unfinished Sanditon, libraries and librarians have helped me immeasurably.

Perhaps it’s my great respect for librarians – and probably also my days as a student librarian at school – that’s turned me into a zealous protector of library regulations. Throughout university I was renowned for disapproving of extended chatting or – gasp – receiving phone calls in the library, and refused to bow to peer pressure and flout the ‘no eating’ rule in my college library.

It’s not just the ways we use libraries that develop, but also libraries themselves. Budget cuts are a sad reality which force libraries to adapt, but they continue to excel in providing entertainment and inspiration. Libraries allow readers to broaden both intellectual and experiential horizons, and can even create reading communities which link diverse members of society.

What do libraries mean to you? Share your own library memories below.

Image Credit: “Library books.” Photo by timetrax23. CC by SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post A lifetime in the library appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCatching up with Sara Levine, Multimedia ProducerCollege Arts Association 2015 Annual Meeting Conference GuideLet the people speak! Devolution, decentralization, deliberation

Related StoriesCatching up with Sara Levine, Multimedia ProducerCollege Arts Association 2015 Annual Meeting Conference GuideLet the people speak! Devolution, decentralization, deliberation

Let the people speak! Devolution, decentralization, deliberation

Democratic pressure is building, cracks and fault-lines are emerging and at some point the British political elite will have to let the people speak about where power should lie and how they should be governed. ‘Speak’ in this sense does not relate to the casting of votes — the General Election will not vent the pressure — but to a deeper form of democracy that facilitates both ‘democratic voice’ and ‘democratic listening’.

In the wake of the Scottish referendum on independence the UK is undergoing a rapid period of constitutional reflection and reform. The Smith Commission has set out a raft of new powers for the Scottish Parliament, the Chancellor of the Exchequer has signed a new devolution agreement with Greater Manchester Combined Authority, the Deputy Prime Minister has signed an agreement with Sheffield City Council, and the Cabinet Committee on Devolved Powers has reported on options for change in Westminster. One critical component of this frenetic period of reform has been the absence of any explicit or managed process for civic engagement even though the Prime Minister’s statement on the 19 September 2014 emphasized that ‘It is also important we have wider civic engagement about how to improve governance in our United Kingdom, including how to empower our great cities. And we will say more about this in the coming days’.

The days and months have passed but no plan for civic engagement has been announced.

In the meantime, calls for a citizen-led constitutional convention have been made with ever increasing regularity and volume. Petitions have been submitted, letters to the papers have been published, a huge number of citizen groups have come together around the idea and all of the main political parties — apart from the Conservatives — have committed themselves to establishing a constitution convention should they form or be part of the government after the 7 May 2015. But even in relation to the Conservative Party — conservative by name, conservative by nature — the pressure to let the people speak is gradually being acknowledged. The Government’s ‘command paper’ on English devolution, published on 16 December 2014, made reference to a constitutional convention as a means of civic engagement (though it fell short of a full commitment).

Edinburgh Scottish Parliament by Klaus with K. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Edinburgh Scottish Parliament by Klaus with K. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Such instruments of deliberative democracy may be distinctly ‘foreign’ and at odds with the elitist British political tradition, with the culture and rituals of a traditional power-hoarding democracy and with the predilection for ‘muddling through’ that defined British politics in the twentieth century. But we are no longer in the twentieth century. ‘Muddling through’ is no longer good enough. The traditional power-hoarding model of British democracy has been hollowed-out and, as a result, new relationships between the governors and the governed must be put in place. The recently published Future of England Survey 2014 provides evidence for this argument with its conclusion that people in England see a ‘democratic deficit’ in the way they are governed (‘devo-anxiety’), and that one dimension of that deficit is a desire for civic engagement. This conclusion focuses attention on the notion of ‘nexus politics’ in which the traditional institutions and processes of democratic politics must somehow engage with, channel and respond to an increasing array of more dynamic bottom-up explosions of democratic energy.

In facing new democratic challenges the UK is by no means unique and arguments in favour of deliberative democracy have been made by scholars including Robert Goodin, John Dryzek, and Tina Nabatchi for decades.

But the recent flurry of devolutionary deals has fuelled democratic discontent in those parts of the UK that seem untouched, unloved and mis-understood by the main political parties. The sudden appearance of cabinet and shadow cabinet members seeking to ingratiate themselves with the ‘Northern powerhouses’ of Manchester, Sheffield, and Leeds has been a sight to behold. But now the time has come to ‘let the people speak’. The issue of holding a constitutional convention has shifted from the periphery of constitutional debates in the UK to the very core. Meanwhile the likelihood of a hung parliament after 7 May and the inter-party deals that will be required to form a coalition, plus the existence of unresolved and urgent constitutional questions which require resolution provides the necessary political backdrop for the establishment of a constitutional convention. How the convention might operate, where it would be based, how convention members would be selected, the use of the final report or recommendations are all second-order issues where experiments in other countries and test-cases in the UK can offer answers. The main question is whether the political elite is really willing to embrace change, take a few risks and let the people speak.

Heading image: Houses of Parliament by By Alvesgaspar (self-made, stitch from 4 photographs). CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Let the people speak! Devolution, decentralization, deliberation appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLooking beyond the Scottish referendumLearning to love democracy: A note to William HagueThomas Aquinas and God

Related StoriesLooking beyond the Scottish referendumLearning to love democracy: A note to William HagueThomas Aquinas and God

Thomas Aquinas and God

One of the benefits of contemporary atheism is that it has brought to the forefront of modern consciousness the demand that believers offer some reason for the belief that they have. Of course, this demand is nothing new, and it even has scriptural support behind it, with St. Peter insisting that Christians ought always be prepared to give a reason for their hope (1 Peter 3:15). Accordingly, the Christian tradition has always cherished and promoted the cultivation of wisdom so that Christianity may be a reasonable belief to hold. Contemporary atheism has brought to the fore the same demand that belief should be reasonable, and so contemporary Christians ought to show that their belief is indeed so.

St. Thomas Aquinas is a man whose name is practically synonymous with the endeavour to show that the religious belief he adopts is a reasonable one to hold. While he is not the only person to whom we can turn in the history of Christian thinkers to meet the demand of the reasonableness of faith, he is certainly a major figure. One of Aquinas’s more well-known journeys into philosophical thinking is in the realm of arguments for the existence of God. His famous five ways from the Summa Theologiae have been anthologised and commented on almost ad nauseam. The five ways represent the thought of Aquinas at the height of his philosophical powers, making use of a lifetime’s research into the different philosophical issues that are at work therein. However, given such a focus, it is common for many non-specialists to believe that the five ways are Thomas’s only proofs for the existence of God, or that they are the only ones worth considering. Not only that, given that they are a reflection of a mature mind making use of philosophical principles developed elsewhere, the five ways can come across as quite dense, with undefended premises, and are thereby often thought to be subject to easy refutation. This is inevitable when assessing the mature work of any important thinker, since that work will always make use of key themes developed elsewhere in his philosophy.

In my work I’ve offered an interpretation and defence of the proof of God from the De Ente et Essentia; for the latter proof is developed in quite an early work and emerges within the context of Thomas’s articulation of the metaphysical nature of reality. Hence the proof in De Ente is relatively easy to follow for the non-specialist. It centers upon Thomas’s characteristic notion of esse – a term that has no ready translation into English and is often translated as “existence” or “act of existence.” What is at the heart of Thomas’s notion of esse is that it is the principle by which something is something rather than nothing, i.e. it is that by which a thing exists. Esse is distinct from the essences of all things of a nature capable of being multiplied. Given that essence and esse are really distinct in things, Thomas reasons that esse is caused in such things. Now if esse is caused in such things the question is, what is the nature of the cause of esse? Is it another thing in which essence and esse are distinct or is it something in which they are not so distinct? If the former then what is the cause of the esse of that? And if the latter, then we have arrived at something that is simply esse, i.e. something whose essence is simply to be. So Thomas sets up a causal regress in the line of esse, and the goal of the proof is to establish that there is something that is simply esse itself, whose essence is to be.

Photo by Lawrence OP. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

Photo by Lawrence OP. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr. In order to achieve his goal, Thomas must establish that the causal regress in the line of esse terminates in a primary cause whose essence is its esse; and so we enter upon the whole discussion of whether or not there can be an infinite regress. Surprisingly, Thomas is not a thinker who simply thinks an infinite regress impossible; rather, Thomas holds that we need to consider the nature of the causal series in question, and then consider whether or not it can be infinite. Thomas distinguishes between two types of causal series: per accidens and per se. He argues that the former is potentially infinite whereas the latter is necessarily finite. His reasons for concluding to the latter are complex, but they center upon the fact that in a per se series, the causality of the series is not possessed by any of the posterior causal relata, whereas in the per accidens series it is. So in the example of a per se series where a mind moves the hand to move a stick to move the stone, the causality of the hand, stick, and stone, i.e. the motion, is not possessed intrinsically by any of them, but is so by the mind. Hence, the mind is the primary cause in that series. On the other hand, in the per accidens series of a father producing a son who produces a son and so on, each member has the causality of the series in himself, i.e. the ability to beget a son.

Given these distinctions, Thomas reasons that in per se series, there must be a cause of the causality of the series, otherwise there is no causality in the series. Consequently, if there were no primary cause of the per se series, there would be no causality in the series, in which case it would fail precisely as a causal series. The same is not the case for the per accidens series because there is no need for a cause of the causality of the series, in which case it is potentially infinite.

When it comes to the causal series in which esse figures, Thomas locates that in a per se framework since esse as a causal property is not possessed by any essence/esse composite essentially. Thus, the causal series in which esse figures is a per se series, and has a primary cause, otherwise the causality of the series, i.e. esse, would have no cause, in which case nothing in the series would exist.

Just as the mind in the mind-hand-stick-stone series is something that possesses the causality of the series essentially, and that’s why it can be the primary cause of the series, so too the primary cause of the series in which esse is the causal property possesses esse essentially, i.e. there is no distinction between essence and esse therein, in which case it is esse itself. As the primary cause of esse, esse itself is that from which all things derive their esse; in which case nothing would be without having received esse from this cause. Hence esse itself is the unique primary cause of the existence of all things. And this is what we understand God to be.

The post Thomas Aquinas and God appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFree will, libertarianism, and luckEssential considerations for leadership in policing (and beyond)Fluorescent proteins and medicine

Related StoriesFree will, libertarianism, and luckEssential considerations for leadership in policing (and beyond)Fluorescent proteins and medicine

Free will, libertarianism, and luck

Do we have free will? Free will is one of the central topics in philosophy, both historically and in the present. The basic puzzles of this topic are easily felt. For instance, it’s easy to wonder whether factors beyond our control — our genetic constitution, the environment in which we were brought up, and so on — might be among the causes of our behavior. In the light of this, we might wonder whether it’s really possible for us to act freely or, instead, whether everything we do is ultimately shaped by these factors in such a way that undermines our free will.

In contemporary philosophical discussions, this concern is crystallized as a concern about the relationship between free will and causal determinism. Causal determinism is the view that for any given time, a complete statement of the facts at that time, together with a complete statement of the laws of nature, entails every truth as to what happens after that time. On this issue, the basic divide among philosophers is between compatibilism and incompatibilism. Compatibilists believe that free will is compatible with determinism, whereas incompatibilists argue that free will is incompatible with determinism. According to incompatibilists, if our actions are causally determined, then we can’t act freely.

One view about free will that has recently received a lot of scholarly attention is the libertarian view of free will. Libertarianism about free will, which is completely distinct from libertarianism as a political doctrine, is the view that people do have free will, but that this freedom is incompatible with determinism. Thus, libertarians are incompatibilists who think that free will exists. (You could, of course, be an incompatibilist who thinks that free will doesn’t exist — a so-called “free will skeptic.”) In short, if libertarianism is true, then people sometimes act without being causally determined to do so.

In many ways, libertarianism is a natural view to hold about free will. After all, it seems obvious to most of us that we have free will, and many people believe that there’s a clear incompatibility between free will and determinism. But despite this appeal, many philosophers are skeptical of libertarianism. They think that there are powerful reasons to think that this view is false.

One especially prominent objection to libertarianism is the “luck objection.” According to this objection, if our actions aren’t causally determined, then our actions or crucial facts about our actions become matters of luck or chance in a way that undermines our free will. To illustrate, suppose that you have a choice between telling the truth or lying, and you decide to tell the truth. In order for your decision to be a free action, then, according to libertarians, it can’t be causally determined by past events. However, what follows from it not being causally determined is that it was open, up until the time you decided as you did, that you wouldn’t decide that way — that is, it was open, keeping everything else fixed up until that moment, that you would decide to lie instead.

In many ways, libertarianism is a natural view to hold about free will.

To appreciate the concern this raises, we can engage in a philosophical thought experiment. Given that your decision to tell the truth wasn’t causally determined, it follows that there’ll be a nearby possible world with the same laws of nature and with the same past up to the moment of decision in which you (or your counterpart) decide differently — you decide to lie rather than decide to tell the truth. But since the laws of nature and the past up to the time of decision are the same in both worlds, then there’s nothing about you — no change in your circumstances or change of mind — that could explain this difference in decision. And if there’s nothing that could explain this difference, then it seems that your deciding to tell the truth rather than deciding to lie is just a matter of (good) luck on your part. But if it’s just a matter of luck that you decided to tell the truth rather than deciding to lie, then surely your decision to tell the truth can’t be a freely-willed action. Or so proponents of the luck objection contend.

There are a number of ways in which libertarians might respond to this objection. For instance, they might deny that the lack of an explanation of the difference between the two decisions entails that the difference is a matter of luck. Or they might deny that the difference’s being a matter of luck entails that your actual decision to tell the truth was not freely made. But these responses remain controversial. And the fate of libertarian views more generally remains controversial as well.

Headline Image Credit: Jubilee Maze, Symonds Yat. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Free will, libertarianism, and luck appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesImmoral philosophyEssential considerations for leadership in policing (and beyond)Fluorescent proteins and medicine

Related StoriesImmoral philosophyEssential considerations for leadership in policing (and beyond)Fluorescent proteins and medicine

January 31, 2015

Catching up with Sara Levine, Multimedia Producer

Another week, another great staff member to get to know. When you think of the world of publishing, the work of videos, podcasts, photography, and animated GIFs doesn’t immediately come to mind. But here at Oxford University Press we have Sara Levine, who joined the Social Media team as a Multimedia Producer just last year.

When did you start working at OUP?

I started working at OUP this past August, three months after completing my Master’s degree at Georgetown University’s Communication, Culture and Technology Program.

How did you get started in multimedia production?

I’ve been drawing comics and making short videos since I was a kid. My first big hit was in high school. I wrote, directed, filmed, and edited a parody of Wuthering Heights called “Withering Estates.” I played Heathcliff. No, it’s not on YouTube.

What is your typical day like at OUP?

My workdays at OUP vary depending on the projects that I’m currently working on. I’m usually filming, animating, drawing, recording audio, editing footage, or multi-tasking any of the above.

“Sara as Heathcliff.” Drawing by Sara Levine.

“Sara as Heathcliff.” Drawing by Sara Levine.What will you be doing once you’ve completed this Q&A?

After I complete this Q&A I’m going to continue making illustrations for an animated short I’m producing for the Oxford Dictionaries YouTube channel.

What gear or software are you obsessed with right now?

I learn something new about Adobe After Effects every time I use it. The unlimited amount of techniques and shortcuts in After Effects seems daunting at first, but I really enjoy exploring everything it can do.

What are you reading right now?

I just started reading Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. I have a bad habit of reading books too quickly (developed over years of tearing through Harry Potter books on their release dates), so I’m trying to pace myself with this one.

“Batwoman.” Drawing by Sara Levine.

“Batwoman.” Drawing by Sara Levine.What’s your favorite book?

Instead of one favorite book, I’m going to list five of my favorite comics:

Batwoman: Elegy by Greg Rucka and J.H. Williams III

The Long Journey by Boulet

Pancakes by Kat Leyh

Skim by Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki

Fun Home by Alison Bechdel

Which book-to-movie adaptation did you actually like?

I was surprised at how much I enjoyed teen movies that are modern adaptations of older works. Films like Clueless, She’s the Man, O, Easy A, and 10 Things I Hate About You are very clever and sometimes overlooked because of their target demographic.

“Sara’s backpack.” Drawing by Sara Levine.

“Sara’s backpack.” Drawing by Sara Levine.What is in your backpack right now?

A Maruman Mnemosyne sketchbook, a Wacom Intuos 2 tablet, Orlando, a manual for the Canon C100, a pencil case, a red umbrella, a disposable rain poncho, a pear, and a small bag of gluten-free pretzels.

Most obscure talent or hobby?

I’m not sure how obscure this is, but I played the French horn for about eight years. The experience gave me very powerful lungs and some great French horn jokes.

What do you do for fun?

I make more multimedia, of course! You can find my doodles, comics, .gifs, and videos under the handle “morphmaker” on Twitter, Tumblr, Vimeo, and Deviantart. I also run a podcast with my sister. It’s called Sara & Allison Talk TV. We discuss television shows and web series that feature central female characters and include elements of fantasy, action, and science fiction.

The post Catching up with Sara Levine, Multimedia Producer appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCollege Arts Association 2015 Annual Meeting Conference GuideEssential considerations for leadership in policing (and beyond)Judicial resistance? War crime trials after World War I

Related StoriesCollege Arts Association 2015 Annual Meeting Conference GuideEssential considerations for leadership in policing (and beyond)Judicial resistance? War crime trials after World War I

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers