Oxford University Press's Blog, page 711

January 18, 2015

World Religion Day 2015

Today, 18 January 2015 marks World Religion Day across the globe. The day was created by the Baha’i faith in 1950 to foster dialogue and to and improve understanding of religions worldwide and it is now in its 64th year.

The aim of World Religion Day is to unite everyone, whatever their faith, by showing us all that there are common foundations to all religions and that together we can help humanity and live in harmony. The day often includes activities and events calling the attention of the followers of world faiths. In honour of this special day and to increase awareness of religions from around the world, we asked a few of our authors to dispel some of the popular myths from their chosen religions.

* * * * *

Myth: Quakers are mostly silent worshippers

“If you are from Britain, or certain parts of the United States, you may think of Quakers as a quiet group that meets in silence on Sunday mornings, with only occasional, brief vocal messages to break the silence. Actually, between eighty and ninety per cent of Quakers are “pastoral” or “programmed” Friends, with the majority of these living in Africa (more in Kenya than any other country) and other parts of the global South. The services are conducted by pastors, and include prayers, sermons, much music, and even occasionally (in Burundi, for instance) dancing! Pastoral Quaker services sometimes include a brief period of “unprogrammed” worship, and sometimes not. Quaker worship can be very lively!”

— Stephen W. Angell is Leatherock Professor of Quaker Studies, Earlham School of Religion and editor of The Oxford Handbook of Quaker Studies

* * * * *

Myanmar, monks and novices, by Dietmar Temps, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr

Myanmar, monks and novices, by Dietmar Temps, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via FlickrMyth: Zen as the Buddhist meditation school

“Zen is known as the Buddhist school emphasizing intensive practice of meditation, the name’s literal meaning that represents the Japanese pronunciation of an Indian term (dhyana). But hours of daily meditative practice are limited to a small group of monks, who participate in monastic austerities at a handful of training temples. The vast majority of members of Zen only rarely or perhaps never take part in this exercise. Instead, their religious affiliation with temple life primarily involves burials and memorials for deceased ancestors, or devotional rites to Buddhist icons and local spirits. Recent campaigns, however, have initiated weekly one-hour sessions introducing meditation for lay followers.”

— Steven Heine is Professor of Religion and History, Director of the Institute for Asian Studies, at Florida International University, and author of Zen Skin, Zen Marrow: Will the Real Zen Buddhism Please Stand Up?

* * * * *

Myth: Atheists have no moral standards

“This was a common cry in the nineteenth century – the British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli made it – and it continues in the twenty-first century. Atheists respond in two ways. First, if you need a god for morality, then what is to stop that god from being entirely arbitrary? It could make the highest moral demand to kill everyone not fluent in English – or Hebrew or whatever. But if this god does not do things in an arbitrary fashion, you have the atheist’s second response. There must be an independent set of values to which even the god is subject, and so why should the non-believer not be subject to and obey them, just like everyone else?”

— Michael Ruse is Lucyle T. Werkmeister Professor of Philosophy and Director of the Program in the History and Philosophy of Science, at Florida State University and an editor of The Oxford Handbook of Atheism

* * * * *

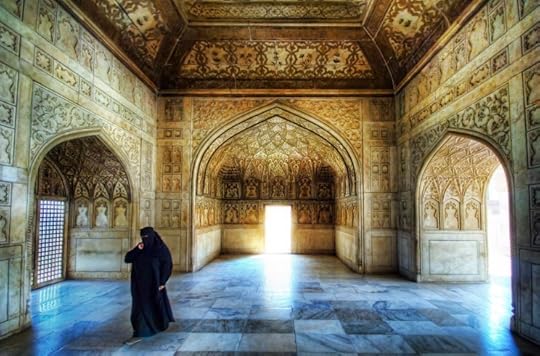

Floating through the temple, by Trey Ratcliff. CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0 via Flickr

Floating through the temple, by Trey Ratcliff. CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0 via FlickrMyth: Islam is a coercive communitarian religion

“Claims of an Islamic state to enforce Sharia as the law of the state are alien to historical Islamic traditions and rejected by the actual current political choices of the vast majority of Muslims globally. Belief in Islam must always be a free choice and compliance with Sharia cannot have any religious value unless done voluntarily with the required personal intent of each individual Muslim to comply (nya). Theologically Islam is radically democratic because individual personal responsibility can never be abdicated or delegated to any other human being (see e.g. chapters and verses 6:164; 17:15; 35:18; 39:7; 52:21; 74:38 of the Quran).”

— Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na‘im is Charles Howard Candler Professor of Law at Emory University, and author of What Is an American Muslim? Embracing Faith and Citizenship

* * * * *

Myth: Are Mormons Christians?

“Are Mormons Christian? Yes, but with greater similarity to the Church before the fourth century creeds gave it its modern shape. Mormons believe in and worship God the Father, but deny the formulas which claim he is without body, parts, or—most critically—passions. Latter-day Saints accept his Son Jesus Christ as Savior and Redeemer, but reject the Trinitarian statements making him of one substance with the Father. Mormons accept the Bible as the word of God, but reject the closed canon dating from the same era, just as they believe that God continues to reveal the truth to prophets and seeking individuals alike.”

— Terryl Givens is Professor of Literature and Religion at the University of Richmond, and author of Wrestling the Angel, The Foundations of Mormon Thought: Cosmos, God, Humanity

* * * * *

Religion in Asia, by Michaël Garrigues, CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0 via Flickr

Religion in Asia, by Michaël Garrigues, CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0 via FlickrMyth: Hinduism is tied to Southern Asia

“One myth about Hinduism is that it is an ethnic religion. The assumption is that Hinduism is tied to a particular South Asian ethnicity. This is misleading for at least three reasons. First, South Asia is ethnically diverse. Therefore, it is not logical to speak of a single, unified ethnicity. Second, Hinduism has long been established in Southeast Asia, where practitioners consider themselves Hindu but not South Asian. Third, although the appearance of ‘White Hindus’ is a phenomenon rather recent and somewhat controversial, the global outreach of Hindu missionary groups has prompted scores of modern converts to Hinduism throughout Europe and the Americas. In other words, not all Hindus are South Asian.”

— Kiyokazu Okita is Assistant Professor at The Hakubi Center for Advanced Research and Department of Indological Studies, Kyoto University, and author of Hindu Theology in Early Modern South Asia

* * * * *

Headline image credit: Candles, photo by Loren Kerns, CC-by-2.0 via Flickr

The post World Religion Day 2015 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIs yoga Hindu?Why causality now?What is it like to be depressed?

Related StoriesIs yoga Hindu?Why causality now?What is it like to be depressed?

Why causality now?

Head hits cause brain damage, but not always. Should we ban sport to protect athletes? Exposure to electromagnetic fields is strongly associated with cancer development. Should we ban mobile phones and encourage old-fashioned wired communication? The sciences are getting more and more specialized and it is difficult to judge whether, say, we should trust homeopathy, fund a mission to Mars, or install solar panels on our roofs. We are confronted with questions about causality on an everyday basis, as well as in science and in policy.

Causality has been a headache for scholars since ancient times. The oldest extensive writings may have been Aristotle, who made causality a central part of his worldview. Then we jump 2,000 years until causality again became a prominent topic with Hume, who was a skeptic, in the sense that he believed we cannot think of causal relationships as logically necessary, nor can we establish them with certainty.

The next major philosophical figure after Hume was probably David Lewis, who proposed quite a controversial account saying roughly that something was a cause of an effect in this world if, in other nearby possible worlds where that cause didn’t happen, the effect didn’t happen either. Currently, we come to work in computer science originated by Judea Pearl and by Spirtes, Glymour and Scheines and collaborators.

All of this is highly theoretical and formal. Can we reconstruct philosophical theorizing about causality in the sciences in simpler terms than this? Sure we can!

One way is to start from scientific practice. Even though scientists often don’t talk explicitly about causality, it is there. Causality is an integral part of the scientific enterprise. Scientists don’t worry too much about what causality is – a chiefly metaphysical question – but are instead concerned with a number of activities that, one way or another, bear on causal notions. These are what we call the five scientific problems of causality:

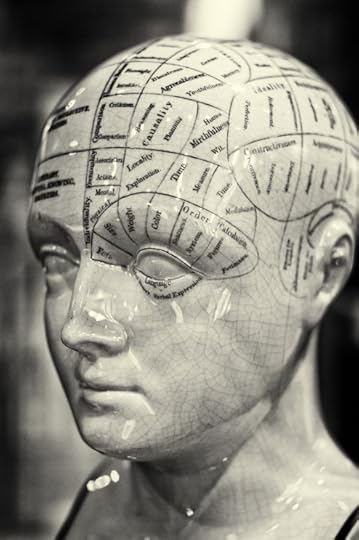

Phrenology: causality, mirthfulness, and time. Photo by Stuart, CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0 via Flickr.

Phrenology: causality, mirthfulness, and time. Photo by Stuart, CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0 via Flickr.Inference: Does C cause E? To what extent?

Explanation: How does C cause or prevent E?

Prediction: What can we expect if C does (or does not) occur?

Control: What factors should we hold fixed to understand better the relation between C and E? More generally, how do we control the world or an experimental setting?

Reasoning: What considerations enter into establishing whether/how/to what extent C causes E?

This does not mean that metaphysical questions cease to be interesting. Quite the contrary! But by engaging with scientific practice, we can work towards a timely and solid philosophy of causality.

The traditional philosophical treatment of causality is to give a single conceptualization, an account of the concept of causality, which may also tell us what causality in the world is, and may then help us understand causal methods and scientific questions.

Our aim, instead, is to focus on the scientific questions, bearing in mind that there are five of them, and build a more pluralist view of causality, enriched by attention to the diversity of scientific practices. We think that many existing approaches to causality, such as mechanism, manipulationism, inferentialism, capacities and processes can be used together, as tiles in a causal mosaic that can be created to help you assess, develop, and criticize a scientific endeavour.

In this spirit we are attempting to develop, in collaboration, complementary ideas of causality as information (Illari) and variation (Russo). The idea is that we can conceptualize in general terms the causal linking or production of effect by the cause as the transmission of information between cause and effect (following Salmon); while variation is the most general conceptualization of the patterns of difference-making we can detect in populations where a cause is acting (following Mill). The thought is that we can use these complementary ideas to address the scientific problems.

For example, we can think about how we use complementary evidence in causal inference, tracking information transmission, and combining that with studies of variation in populations. Alternatively, we can think about how measuring variation may help us formulate policy decisions, as might seeking to block possible avenues of information transmission. Having both concepts available assists in describing this, and reasoning well – and they will also be combined with other concepts that have been made more precise in the philosophical literature, such as capacities and mechanisms.

Ultimately, the hope is that sharpening up the reasoning will assist in the conceptual enterprise that lies at the intersection of philosophy and science. And help decide whether to encourage sport, mobile phones, homeopathy and solar panels aboard the mission to Mars!

The post Why causality now? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat is it like to be depressed?“Sorry mate, I didn’t see you”: perceptual errors and inattentional blindnessAccusation breeds guilt

Related StoriesWhat is it like to be depressed?“Sorry mate, I didn’t see you”: perceptual errors and inattentional blindnessAccusation breeds guilt

January 17, 2015

Hey everybody! Meet Sonia!

Please welcome another newbie to the Social Media team at Oxford University Press, Sonia Tsuruoka, who joined the gang in January 2015 as an OUPblog Deputy Editor and Social Media Marketing Assistant! She has been working at OUP since June 2014.

When did you start working at OUP?

I started as a social media intern the summer before my senior year of college. A year later, I hopped over to Online Marketing for a full-time job, where I grappled with all things HTML. Now, I’m back where I started (at the very same desk I had when I was an intern!), and couldn’t be happier.

What is your typical day like at OUP?

No day is exactly the same in social media, which is the beauty of it! Between handling standard editorial stuff for the OUPBlog, I could be doing anything from researching poetic rhetoric to hunting for Richard Dawkins gifs.

What is the strangest thing currently on or in your desk?

The best Secret Santa gift I have ever received.

Facebook shot glasses. Photo by Sonia Tsuruoka.

Facebook shot glasses. Photo by Sonia Tsuruoka.What drew you to work for OUP in the first place?

A lot of people think the publishing industry draws bookworms like moths to a flame. My answer will probably not change that suspicion.

What’s your favourite book?

Moby Dick—I’m a huge Herman Melville enthusiast. I’ve even visited the New Bedford Whaling Museum, and I have a wooden box inscribed with “and the great flood gates of the wonder world swung open…then it collapsed, and the great sea shroud of the sea rolled on.”

What was your first blog post ever?

For my first post, I blogged about the politics of “slum tourism.” Then I wrote a retrospective on William Ernest Henley’s “Invictus.” I was a double major in Political Science and Writing Seminars, so I’m always bouncing back and forth between both worlds.

If you didn’t work in publishing, what would you be doing?

I’d have trouble deciding between political speechwriter, sleep-deprived English professor, and full-time Marilynne Robinson groupie.

What are you reading right now?

Right now, I’m working my way through books written by two professors I had the amazing privilege of working with in the Johns Hopkins’ Writing Seminars program—Return Fire by Glenn Blake and Sparks from a Nine-Pound Hammer by Steve Scafidi. Great people, and even better writers. There’s just something so arresting about the Southern poetic.

Open the book you’re currently reading and turn to page 78. Tell us the title of the book, and the third sentence on that page.

“There is a long bridge over these waters, and as you drive across, you can look to the south and see where the Old River and the Lost River become the Old and the Lost.” (Return Fire, Glenn Blake)

What is your favourite word?

It would be a toss-up between saudade and schadenfreude. There’s such loveliness outside the English language.

If you could trade places with any one person for a week, who would it be and why?

Bruce Springsteen. I think this is every native New Jerseyan’s dream.

Most obscure talent or hobby?

Totally random, but I can recite Matthew Arnold’s “Dover Beach” by heart. To this day I have no idea how this happened.

The post Hey everybody! Meet Sonia! appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat is it like to be depressed?Fear vs terror: signal crimes, counter-terrorism, and the Charlie Hebdo killingsAre wolves endangered with extinction in Alaska?

Related StoriesWhat is it like to be depressed?Fear vs terror: signal crimes, counter-terrorism, and the Charlie Hebdo killingsAre wolves endangered with extinction in Alaska?

What is it like to be depressed?

How are we to understand experiences of depression? First of all, it is important to be clear about what the problem consists of. If we don’t know what depression is like, why can’t we just ask someone who’s depressed? And, if we want others to know what our own experience of depression is like, why can’t we just tell them? In fact, most autobiographical accounts of depression state that the experience or some central aspect of it is difficult or even impossible to describe. Depression is not simply a matter of the intensification of certain familiar aspects of experience and the diminution of others, such as feeling more sad and less happy, or more tired and less energetic. First-person accounts of depression indicate that it involves something quite alien to what — for most people — is mundane, everyday experience. The depressed person finds herself in a ‘different world’, an isolated, alien realm, adrift from social reality. There is a radical departure from ‘everyday experience’, and this is not a localized experience that the person has within a pre-given world; it encompasses every aspect of her experience and thought – it is the shape of her world. It is the ‘world’ of depression that people so often struggle to convey.

My approach involves extracting insights from the phenomenological tradition of philosophy and applying them to the task of understanding depression experiences. That tradition includes philosophers such as Edmund Husserl, Edith Stein, Martin Heidegger, Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Jean-Paul Sartre, all of whom engage in ‘phenomenological’ reflection – that is, reflection upon the structure of human experience. Why turn to phenomenology? Well, these philosophers all claim that human experience incorporates something that is overlooked by most of those who have tried to describe it — what we might call a sense of ‘belonging to’ or ‘finding oneself in’ a world. This is something so deeply engrained, so fundamental to our lives, that it is generally overlooked. Whenever I reflect upon my experience of a chair, a table, a sound, an itch or a taste, and whenever I contrast my experience with yours, I continue to presuppose a world in which we are both situated, a shared realm in which it is possible to encounter things like chairs and to experience things like itches. This sense of being rooted in an interpersonal world does not involve perceiving a (very big) object or believing that some object exists. It’s something that is already in place when we do that, and therefore something that we seldom reflect upon.

The Concern by Alex Proimos. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The Concern by Alex Proimos. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia CommonsDepression, I suggest, involves a shift in one’s sense of belonging to the world. We can further understand the nature of this once we acknowledge the role that possibilities play in our experience. When I get up in the morning, feel very tired, stop at a café on the way to work, and then look at a cup of coffee sitting in front of me, what do I ‘experience’? On one account, what I ‘see’ is just what is ‘present’, an object of a certain type. But it’s important to recognize that my experience of the cup is also permeated by possibilities of various kinds. I see it as something that I could drink from, as something that is practically accessible and practically significant. Indeed, it appears more than just significant – it is immediately enticing. Rather than, ‘you could drink me’, it says ‘drink me now’. Many aspects of our situation appear significant to us in some way or other, meaning that they harbor the potentiality for change of a kind that matters. We can better appreciate what experiences of depression consist of once we construe them in terms of shifts in the kinds of possibility that the person has access to. Whereas the non-depressed person might find one thing practically significant and another thing not significant, the depressed person might be unable to find anything practically significant. It is not that she doesn’t find anything significant, but that she cannot. And the absence is very much there, part of the experience – something is missing, painfully lacking, and nothing appears quite as it should do. In fact, many first-person accounts of depression explicitly refer to a loss of possibility. Here are some representative responses to a questionnaire study that I conducted with colleagues two years ago, with help from the mental health charity SANE:

“I remember a time when I was very young – 6 or less years old. The world seemed so large and full of possibilities. It seemed brighter and prettier. Now I feel that the world is small. That I could go anywhere and do anything and nothing for me would change.”

“It is impossible to feel that things will ever be different (even though I know I have been depressed before and come out of it). This feeling means I don’t care about anything. I feel like nothing is worth anything.”

“The world holds no possibilities for me when I’m depressed. Every avenue I consider exploring seems shut off.”

“When I’m not depressed, other possibilities exist. Maybe I won’t fail, maybe life isn’t completely pointless, maybe they do care about me, maybe I do have some good qualities. When depressed, these possibilities simply do not exist.”

By emphasizing the experience of possibility, we can understand a great deal. Suppose the depressed person inhabits an experiential world from which the possibility of anything ever changing for the better is absent; nothing offers the potential for positive change and nothing draws the person in, solicits action. This lack permeates every aspect of her experience. Her situation seems strangely timeless, as no future could differ from the present in any consequential way. Action seems difficult, impossible or futile, because there is no sense of any possibility for significant change. Her body feels somehow heavy and inert, as it is not drawn in by situations, solicited to act. She is cut off from other people, who no longer offer the possibility of significant kinds of interpersonal connection. Others might seem somehow elsewhere, far away, given that they are immersed in shared goal-directed activities that no longer appear as intelligible possibilities for the depressed person. We can thus see how the kind of ‘hopelessness’ or ‘despair’ that is central to so many experiences of depression differs in important respects from more mundane feelings that might be described in similar ways. I might lose hope in a certain project, but I retain the capacity for hope — I can still hope for other things. Some depression experiences, in contrast, involve erosion of the capacity for hope. There is no sense that anything of worth could be achieved or that anything good could ever happen — the attitude of hope has ceased to be intelligible; the person cannot hope.

Of course, it should also be conceded that depression is a heterogeneous, complicated, multi-faceted phenomenon; no single approach or perspective will yield a comprehensive understanding. Even so, I think phenomenological research has an important role to play in solving a major part of the puzzle, thus feeding into a broader understanding of depression and informing our response to it.

Heading image: Depression. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post What is it like to be depressed? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories“Sorry mate, I didn’t see you”: perceptual errors and inattentional blindnessIs yoga Hindu?Gait disturbances can help to predict dementia in older adults

Related Stories“Sorry mate, I didn’t see you”: perceptual errors and inattentional blindnessIs yoga Hindu?Gait disturbances can help to predict dementia in older adults

Fear vs terror: signal crimes, counter-terrorism, and the Charlie Hebdo killings

Signal crimes change how we think, feel, and act — altering perceptions of the distribution of risks and threats in the world. Sometimes, as with the recent assassinations and mass shootings in France, sending a message is the intention of the criminal act. The attackers’ target selection of the staff of Charlie Hebdo magazine, and that of taking and killing Jewish hostages, was deliberately designed to send messages to individuals and institutions.

Researchers examine social reactions to different kinds of crime events and the signals they send to a range of audiences. The aim is to determine how and why certain kinds of incidents and situations generate fear and anxiety responses that travel widely and, by extension, how processes of social reaction to such events are managed and influenced by the authorities.

The murder of Lee Rigby in London in 2013 can be understood as a signal crime as it triggered concern amongst the general public and across security institutions, owing to the macabre innovation of the killers in undertaking a brutally simple form of assault. Analysis of the crime has identified a number of key components to the overarching process of social reaction. Observing how events have unfolded in France, the collective reactions have followed a similar trajectory to what happened in London.

In the wake of both incidents there was ‘spontaneous community mobilisation’ as ordinary people sought to engage in collective sense-making of what had actually happened, coupled with collective action ‘to do something’ to evidence their opposition. Widespread use of social media platforms helped spread rumours as attempts were made to follow updates in the story; rapid moves were made to secondary conflicts as acts of criminal retaliation were committed against symbolic Muslim targets.

One prominent type of intervention evident in both cases has been a call from senior figures within security institutions and governments to urgently provide the authorities with enhanced legal powers, especially for digital and online surveillance. This is part of a wider reaction pattern that we might label ‘the legislative reflex’. This term seeks to capture how – following a terrorist atrocity and the public concern it induces – politicians who need to be seen to be ‘doing something’ almost automatically reach for new laws as their principal response. The presence of this reflex is evidenced by the fact that since 9/11, in the United Kingdom we have seen the introduction of a significant number of new laws including:

The Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001, allowing for detention without trial (later overturned by the courts)

The Terrorism Act 2006, which extended the detention of suspects without charge from 14 to 28 days

The Counter-Terrorism Act 2008, under which police were permitted to continue questioning suspects after charge

The Terrorist Asset-Freezing Act 2010

The Counter-Terrorism and Security Bill, which is currently being debated by peers in the House of Lords

What we can detect here is how fear of not being able to protect against potential attacks is being mobilised to justify new preventative anti-terror legislation. In effect, public and political fear is being deployed to shape the reaction to terrorism, where reaching for new legislation has become part of the societal response to terrorist attacks.

However, it increasingly appears that this approach is inadequate and that we are dealing with a social problem that we cannot solve by legal means alone. Indeed, a more nuanced and sophisticated approach to counter-terrorism policy development would probably look elsewhere for solutions. After all, in both the French cases and that of Drummer Rigby, it transpired that the perpetrators were well known to the authorities as presenting a risk. Rather than creating legislative fixes to collect more intelligence, research suggests the focus must be on finding effective policy solutions to three inter-linked ‘wicked problems’ that have been identified in issues of radicalization and home-grown extremism.

The first of these, mentioned earlier, concerns the ability of the politics of counter-terrorism to resist the allure of introducing new security measures that might corrode levels of integration and cohesion. Over the long-term, over-reaction to terrorist provocations can be as harmful as the initial act itself.

This connects to the second ‘wicked problem’: tension between the tactical and strategic response to countering violent extremists. The police and security services focus upon stopping violent acts, often engaging with individuals whose ideas are not coherent with liberal democratic traditions. Preventing or stopping these acts does not reduce the longer term influence of these radical ideas.

Thirdly, all plausible theories of radicalisation into violent extremism identify a pivotal role played by ‘non-violent extremists': those who do not engage in violence directly, but whose ideas and rhetoric influence others to do so. These create a ‘mood music’ of ideas, values, and beliefs that presents violence as a permissible means to an end. In the wake of the killings in France, there has been a widespread call across Europe to protect the right to freedom of speech. However, this freedom will also be used by those motivated to undertake mass killings. Current counter-terrorism policy struggles with what to do with individuals who steer and propagate the radicalisation of others by engaging in activity that is troublesome and unpleasant, but not necessarily illegal.

One of the principal institutional effects of high profile signal crimes is to implant a political imperative to consider what can be done to predict, pre-empt, and prevent similar atrocities in the future. However, it is increasingly clear that it is not going to be possible to prevent all such attacks. Developing a conceptually robust evidenced understanding of how and why our collective processes of reaction occur in the ways they do, and the institutional effects that such assaults induce, seems vitally important if we are to collectively manage our reactions better when the next attack comes.

Headline image credit: Paris rally in support of the victims of the 2015 Charlie Hebdo shooting, 11 January 2015. Photo by “sébastien amiet;l”. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Fear vs terror: signal crimes, counter-terrorism, and the Charlie Hebdo killings appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCharlie Hebdo and the end of the French exceptionIs yoga Hindu?“Sorry mate, I didn’t see you”: perceptual errors and inattentional blindness

Related StoriesCharlie Hebdo and the end of the French exceptionIs yoga Hindu?“Sorry mate, I didn’t see you”: perceptual errors and inattentional blindness

Are wolves endangered with extinction in Alaska?

Wolves in the panhandle of southeast Alaska are currently being considered as an endangered species by the US Fish and Wildlife Service in response to a petition by environmental groups. These groups are proposing that the Alexander Archipelago wolf (Canis lupus ligoni) subspecies that inhabits the entire region and a distinct population segment of wolves on Prince of Wales Island are threatened or endangered with extinction.

Whether or not these wolves are endangered with extinction was beyond the scope of our study. However our research quantified the genetic variation of these wolves in southeast Alaska which can contribute to assessing their status as a subspecies.

Because the US Endangered Species Act (ESA) defines species as “species, subspecies, and distinct population segments”, these categories are all considered “species” for the ESA. Although this definition is not consistent with the scientific definition of species it has become the legal definition of species for the ESA.

Therefore we have two questions to consider:

Are the wolves in southeast Alaska a subspecies?

Are the wolves on Prince of Wales Island a distinct population segment?

The literature on subspecies and distinct population segment designation is vast, but it is important to understand that subspecies is a taxonomic category, and basically refers to a group of populations that share an independent evolutionary history.

Taxonomy is the science of biological classification and is based on evolutionary history and common ancestry (called phylogeny). Species, subspecies, and higher-level groups (e.g, a genus such as Canis) are classified based on common ancestry. For example, wolves and foxes share common ancestry and are classified in the same family (Canidae), while bobcats and lions are classified in a different family (Felidae) because they share a common ancestry that is different from foxes and wolves.

Wolf in southeast Alaska. Photo credit: Kristian Larson, the Alaska Dept of Fish and Game (Wildlife Conservation Division, Region I). Image used with permission.

Wolf in southeast Alaska. Photo credit: Kristian Larson, the Alaska Dept of Fish and Game (Wildlife Conservation Division, Region I). Image used with permission.Subspecies designations are often subjective because of uncertainty about the relationships among populations of the same species. This leads many scientists to reject or ignore the subspecies category, but because the ESA is the most powerful environmental law in the United States the analysis of subspecies is of great practical importance.

Our results and other research showed that the wolves in Southeast Alaska differed in allele frequencies compared to wolves in other regions. Allele frequencies reflect the distribution of genetic variation within and among populations. However, the wolves in southeast Alaska do not comprise a homogeneous population, and there is as much genetic variation among the Game Management Units (GMU) in southeast Alaska as there is between southeast Alaska and other areas.

Our research data showed that the wolves in southeast Alaska are not a homogeneous group, but consist of multiple populations with different histories of colonization, isolation, and interbreeding. The genetic data also showed that the wolves on Prince of Wales Island are not particularly differentiated compared to the overall differentiation in Southeast Alaska and do not support designation as a distinct population segment.

The overall pattern for wolves in southeast Alaska is not one of long term isolation and evolutionary independence and does not support a subspecies designation. Other authors, including biologists with the US Fish and Wildlife Service, also do not designate wolves in southeast Alaska as a subspecies and there is general recognition that North America wolf subspecies designations have been arbitrary and are not supported by genetic data.

There is growing recognition in the scientific community of unwarranted taxonomic inflation of wildlife species and subspecies designations to achieve conservation goals. Because the very nature of subspecies is vague, wildlife management and conservation should focus on populations, including wolf populations. This allows all of the same management actions as proposed for subspecies, but with increased scientific rigor.

Headline image credit: Alaskan wolf, by Douglas Brown. CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Are wolves endangered with extinction in Alaska? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMaking the case for history in medical educationGait disturbances can help to predict dementia in older adultsThe shape of our galaxy

Related StoriesMaking the case for history in medical educationGait disturbances can help to predict dementia in older adultsThe shape of our galaxy

January 16, 2015

Is yoga Hindu?

Given that we see yoga practically everywhere we turn, from strip-mall yoga studios to advertisements for the Gap, one might assume a blanket acceptance of yoga as an acceptable consumer choice.

Yet, a growing movement courts fear of the popularization of yoga, warning that yoga is essentially Hindu. Some Christians, including Albert Mohler (President of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary), Pat Robertson (television evangelist and founder of the Christian Coalition of America), and the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith of the Roman Catholic Church, warn about the dangers of yoga given the perceived incompatibility between what they believe is its Hindu essence and Christianity. Some well-known Americans, such as Mohler, add that yoga’s popularization threatens the Christian essence of American culture. Hindu protesters, most notably represented by the Hindu American Foundation (HAF), criticize yoga insiders for failing to recognize yoga’s so-called Hindu origins and illegitimately co-opting yoga for the sake of profit.

Protesters rely on revisionist histories that essentialize yoga as Hindu, ignoring its historical and lived heterogeneity. By the end of the first millennium C.E., however, a variety of yoga systems were widespread in South Asia as Hindu, Buddhist, Jains, and others prescribed them. Following the twelfth-century Muslim incursions into South Asia and the establishment of Islam as a South Asian religion, even Muslim Sufis appropriated elements of yoga. Therefore, throughout its premodern history, yoga was culturally South Asian but did not belong to any single religious tradition. Rather than essentializing premodern yoga by reifying its content and aims, it is more accurate to identify it as heterogeneous in practice and characteristic of the doctrinally diverse culture of South Asia.

Antoinettes Yoga Garden. Photo by Robert Begil. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

Antoinettes Yoga Garden. Photo by Robert Begil. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.The history of modern postural yoga, a fitness regimen made up of sequences of often-onerous bodily postures, the movement through which is synchronized with the breath, also problematizes the identification of yoga as Hindu. That history is a paragon of cultural encounters in the process of constructing something new in response to transnational ideas and movements, including military calisthenics, modern medicine, and the Western European and North American physical culture of gymnasts, bodybuilders, martial experts, and contortionists. Yoga proponents constructed new postural yoga systems in the twentieth century, and nothing like them appeared in the historical record up to that time. In other words, the methods of postural yoga were specific to the twentieth century and would not have been considered yoga prior.

In short, recent scholarship has shown that the type of yoga that dominates the yoga industry today—modern postural yoga—does not have its so-called “origins” in some static, “classical,” Hindu yoga system; rather, it is a twentieth-century transnational product, the aims of which include modern conceptions of physical fitness, stress reduction, beauty, and overall well-being. Hence recent scholarship on yoga, both historical and lived, attends to the particularities of different yoga traditions, which vary based largely on social context.

Nevertheless, protesters against the popularization of yoga, in strikingly similar ways, are polemical, prescriptive, and share misguiding orientalist and reformist strategies that essentialize yoga as Hindu. Interestingly though, the two protesting positions emerge as much from the cultural context—that is, consumer culture—that they share with popularized yoga as from a desire to erect boundaries between themselves and yoga insiders. For example, protesters participate in the same consumer dialect, assuming the importance of “choosing” a fitness regimen that fits one’s personal lifestyle and serves the goal of self-perfection. The protesters positions, in other words, are as much the products of the social context they share with postural yoga advocates as popularized yoga itself.

Image Credit: Yoga. Photo by Matt Madd. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Is yoga Hindu? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOn the notion of a “creator” of modern yogaThe commodification and anti-commodification of yogaIs yoga religious?

Related StoriesOn the notion of a “creator” of modern yogaThe commodification and anti-commodification of yogaIs yoga religious?

A Motown music playlist

On 12 January 1959, Berry Gordy, Jr. founded Tamla Records in Detroit, Michigan. A year later it would be incorporated with a new name that became synonymous with a sound, style, and generation of music: Motown. All this week we’re looking the great artists and tracks that emerged from those recording studios. Previously, we spoke to Charles Randolph-Wright, the Director of Broadway’s Motown the Musical, which closes on Sunday, 18 January 2015; Larvester Gaither examined the role of Duets, Girl Groups, and Solo artists in Motown.

More than half a century after its founding, Motown is still remembered by fans, musicians, and historians as the mover and shaker of its generation. From The Temptations’ “My Girl” to Marvin Gaye’s “I Heard It Through The Grapevine,” its reverberating influence is recognized even today, echoed in modern hits like Mark Ronson and Bruno Mars’ wildly popular “Uptown Funk.” Revisit the soulful croons, hypnotic hooks, and infectious beats that kickstarted not only a record label, but a revolutionary musical movement. Get on up and move your feet to these funky grooves and classic Motown beats!

Headline image credit: 1960s music studio. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post A Motown music playlist appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWomen’s contributions to the making of Motown: Solo artistsWomen’s contributions to the making of Motown: Girl GroupsWomen’s contributions to the making of Motown: The Duets

Related StoriesWomen’s contributions to the making of Motown: Solo artistsWomen’s contributions to the making of Motown: Girl GroupsWomen’s contributions to the making of Motown: The Duets

‘Persia’ and the western imagination

Iran has long had a difficult relationship with the West. Ever since the Islamic Revolution of 1979 overthrew the monarchy and established an Islamic Republic, Iran has been associated in the popular consciousness with militant Islam and radical anti-Westernism. ‘Persia’ by contrast has long been a source of fascination in the Western imagination eliciting both awe and contempt that only familiarity can bring. Indeed if ‘Iran’ seems altogether alien to us, ‘Persia’ seems strangely familiar. There are few cultural icons or aspirations that we would associate with Iran; there are by contrast quite a few we would relate to Persia, most obviously carpets, the occasional cat and for the truly affluent, caviar. That these two words would elicit such dramatically different associations is all the more striking because they are describing the same place. Persia is simply the name inherited from the Greeks and the Romans for the great empire to the East that its inhabitants came to know as ‘Iran’. Persia, from the province of Pars, was not unknown to the Iranians but they would not have used it to apply to the entirety of their state.

Yet Persia reminds us that Iran is not as unfamiliar to us as we might imagine. Quite the contrary. The Persians serve an almost unique function in the Western narrative, being present at the birth and some might argue, the creation of a distinctly Western civilisation. If the Greeks under the influence of Herodotus, first defined history as a conflict between ‘East’ and ‘West’, identified as the Persian and the Greeks, it was a model reinforced with some vigour by the Romans whose own political expediency ensured that many nuances in the relationship were smoothed out to provide a reassuring narrative of confrontation between an increasingly civilised West and barbaric East. Yet if the Romans held up the Persians as a mirror upon which to reflect their own glories, the mirror was never quite as untarnished as its proponents would have liked to believe: the Persians were never quite the antithesis of the West that some sought to portray. The relationship, as the Greeks might have protested, was a good deal more subtle and a great deal more intimate.

This is perhaps best exemplified by the attitude towards the Persian king Cyrus the Great, widely admired in the Greek world as the ideal king whose political wisdom was fictionalised for posterity by Xenophon in his Cyropaedia, or ‘Education of Cyrus’. Cyrus, real or imagined was to have a profound influence on the political elites of the Western world from the renaissance through to the Enlightenment, while his role as a ‘messiah’ in the Old Testament has ensured an enduring affection among Christians, intriguingly among the Protestant variety that populated North America where the name remains popular.

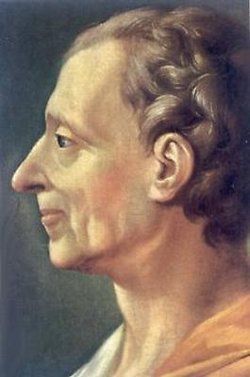

Charles Montesquieu, by After Jacques-Antoine Dassier (1715–1759). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Charles Montesquieu, by After Jacques-Antoine Dassier (1715–1759). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Indeed the ancient Persians, for all their antagonism retained nobility that made them attractive to their Western protagonists. So much so, that when Montesquieu sought ‘discussants’ to critique the condition of Western – in this case French – state and society, he produced his ‘Persian Letters’. The Persians in the Western imagination were sufficiently ‘civilised’ to perform this role. They were educated and had good ‘manners’; were proficient in poetry to the highest standard and, as Cyrus himself exemplified, were masters of the art of landscape gardening, indicative of man’s power over and connection with nature. Indeed the Old Persian word for walled garden has given us our word for ‘paradise’.

It is striking how many Renaissance princes sought to emulate these characteristics and achievements. Yet by the end of the Enlightenment, as Western power grew to surpass that of the Persians, and travellers became reacquainted with the country and its people, old prejudices were redefined for the modern era. The Iranians were not quite like the Persians of their imagination but there was a convenient explanation to hand. The Persians of old were undoubtedly civilised but they had succumbed to decadence and hence decay. They had in sum become excessively civilised and indulgent; exotic yet effete. This explained their predicament and reconciled the apparent contradiction of being both civilised and barbarous at the same time.

Gibbon, perhaps like Herodotus before him, had found a means of reconciling contradictory tendencies, not only in defining the Persians but in explaining the Western relationship with them. A relationship that has been far from confrontational and much more symbiotic than some might suspect. Persia represents at once an ideal and the dangers ever-present in the corruption of that ideal. Persia – and by extension Iran – has been part of the grand narrative of the ‘West’ since its inception: it is neither as alien, nor indeed as foreign, as we may like to think.

Featured image credit: Apadana of Persepolis, by F. Ameli A Persian. CC BY-SA-2.5 via Wikimedia Commons

The post ‘Persia’ and the western imagination appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMinerals, molecules, and microbesMisunderstanding World War IIOminous synergies: Iran’s nuclear weapons and a Palestinian state

Related StoriesMinerals, molecules, and microbesMisunderstanding World War IIOminous synergies: Iran’s nuclear weapons and a Palestinian state

January 15, 2015

Gait disturbances can help to predict dementia in older adults

About 500,000 Canadians are living with Alzheimer’s disease or a related dementia. This number is expected to soar to 1.1 million within 25 years. To date, there is no definitive way for health care professionals to forecast the onset of dementia in a patient with memory complaints. However, new research provides a glimmer of hope.

As a geriatrician, I have been looking at walking speed and variability as a predictor of dementia’s progression and whether it is associated with physical changes in the brain.

The “Gait and Brain Study” is a longitudinal cohort study funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). It assessed up to 150 seniors with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) — a pre-dementia syndrome — in order to detect an early predictor of cognitive and mobility decline, and progression to dementia.

While walking has long been considered an automatic motor task, emerging evidence suggests cognitive function plays a key role in the control of walking, avoidance of obstacles, and maintenance of navigation.

Drs. Michael Borrie (middle) and Manuel Montero-Odasso (right) performing a gait assessment of the data about gait speed and variability. Courtesy of author.

Drs. Michael Borrie (middle) and Manuel Montero-Odasso (right) performing a gait assessment of the data about gait speed and variability. Courtesy of author.In our recent research, my team asked people with mild cognitive impairment to walk on a specially-designed mat linked to a computer. The computer recorded the individual’s walking gait variability and speed. This information was then compared to their walking gait while simultaneously performing a demanding cognitive task, such as counting backwards or doing calculations while walking (“walking-while-talking”).

It was subsequently determined that some specific gait characteristics are associated with high variability, particularly during walking-while-talking. These gait abnormalities were more marked in MCI individuals with the worst episodic memory and with executive dysfunction revealing a motor signature of cognitive impairment.

If confirmed in subsequent studies, these gait changes can be an effective predictor of cognitive decline and may eventually help with earlier diagnoses of dementia.

Finding early dementia detection methods is vital. In the future, it is conceivable that we will be able to make diagnoses of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias before people even have significant memory loss. We believe that gait, as a complex brain-motor task, provides a golden window of opportunity for researchers to see brain function. The high variability observed in people with mild cognitive impairment can be seen as a “gait arrhythmia,” predicting mobility decline, falls, and now, cognitive impairment. Our hope is to combine these methods with promising new medications to slow or halt the progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia.

Image Credit: Elderly person walking CC0 via Pixabay

The post Gait disturbances can help to predict dementia in older adults appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTensions in French Muslim identitiesMaking the case for history in medical educationAdderall and desperation

Related StoriesTensions in French Muslim identitiesMaking the case for history in medical educationAdderall and desperation

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers