Oxford University Press's Blog, page 710

January 20, 2015

The economics behind detecting terror plots

Editor’s note: This post was written by Edward H. Kaplan before the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attacks in Paris on 7th January 2015.

How many good guys are needed to catch the bad guys? This is the staffing question faced by counterterrorism agencies the world over. While government officials are quick to proclaim “zero tolerance” for terrorism, unlimited resources are not made available to prevent terror attacks, nor should that be the case. Indeed, as with most public policy decisions, the appropriate staffing level depends upon both the benefits and costs of fielding counterterrorism agents.

The benefits derive from successfully interdicting terror attacks and averting the damage such attacks impose in deaths, injury, property and infrastructure damage, and more generally population fear and anxiety. While intensifying both covert and overt counterterror intelligence efforts does lead to greater detection, as with many other economic activities, there are diminishing returns to effort: doubling the number of agents will not lead to a doubling of the detection rate, and indeed the marginal detection rates fall rapidly as the number of counterterror agents grows.

And as the number of counterterror agents grows, so does the cost of detecting terror plots. However, unlike detection levels, the marginal cost of adding additional agents stabilizes, for all agents must be trained, outfitted, and compensated. These simple economic considerations are sufficient to suggest that there is a socially optimal counterterror staffing level, which in turn implies a socially efficient detection level for terror plots. So, while government officials contend that even one terror attack is one too many, economics suggests that there is an optimal fraction of terror attacks to prevent that equates the marginal benefits and costs of detection, and this optimal fraction could be significantly less than unity.

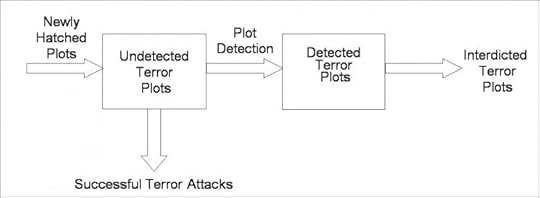

How to operationalize the concepts described above is another matter, for unlike many production processes, it is not easy to observe the relationship between counterterror agent staffing on the one hand, and terror plot detection on the other. However, progress in this area has been made thanks to methods borrowed from queueing theory, which is applied widely to study staffing problems in situations ranging from telephone call centers to hospitals to manufacturing facilities to air traffic control. As shown in the figure below, newly hatched terror plots can be construed as “customers” who “arrive” to a service system.

Terrorism diagram, by Edward H. Kaplan. Used with permission.

Terrorism diagram, by Edward H. Kaplan. Used with permission.Upon arrival, a new plot is undetected, and will remain so until it is detected, or matures to an actual terror attack, whichever happens first. The number of counterterror agents drives the rate with which plots are detected, but of course the total number of detected plots also depends upon the actual number of plots that exist. Once a plot is detected, it can be interdicted, thus this terror queue framework provides the link between the number of counterterror agents fielded on the one hand, and the number of terror plots that are detected and interdicted on the other.

There are still details that must be specified to complete the analysis, and it is in these details that a recent ten year study of all Jihadi terror plots in the United States provides important data. From an analysis of court records including the testimony of undercover operatives in addition to suspect confessions or observed attack details, it was possible to approximate the starting dates for a sample of terror attacks in addition to the observed dates of actual attack or plot detection, whichever came first. From these data, an interesting hypothesis emerged: when is a terror plot more likely to be detected? The answer is that as a plot edges closer to the moment of execution as a terror attack, there is more activity on the part of would be attackers, and this increased level of activity provides more opportunities for counterterror agents to detect an attack. This idea can be formalized by stating that the instantaneous chance that an undetected plot is detected is proportional to the instantaneous chance this same plot executes as an attack. In language more familiar to economists and statisticians alike, the plot detection hazard is proportional to the attack hazard, which gives rise to what is known as a proportional hazards model. The Jihadi plot data mentioned above are consistent with this hypothesis, which greatly simplifies the relationship between agent staffing levels on the one hand and the fraction of terror plots that are detected on the other.

FBI headquarters in Washington D.C., by Aude. CC-BY-SA-2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

FBI headquarters in Washington D.C., by Aude. CC-BY-SA-2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.With this new model in hand, what remains is a valuation step – what is the marginal benefit of preventing a terror attack, and what is the marginal cost of assigning an additional agent? Both of these quantities can be estimated from the terrorism literature. For example, data suggest the typical number of persons killed and injured in terror attacks in Europe, Israel and the United States, well-known economic studies have estimated the value of a statistical life, and a more recent study has established that on average, the disability adjusted life years (DALYs) lost per terrorism injury are equivalent to 0.57 of the DALYs lost due to a death from terrorism. On the cost side, the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) provide information regarding the salaries and benefits received by FBI special agents, who comprise the principal counterterror detection force in the United States.

Applying the model to the United States leads to an interesting and perhaps counterintuitive result. The Jihadi plot data report that 80% of these plots were interdicted prior to attack. If one uses this observation to calibrate the proportional hazards relation between attack and detection discussed above, the model suggests an optimal staffing level of only 2,080 agents. It is interesting that in 2004, the FBI reported that 2,398 of 11,881 special agents were devoted to counterterrorism. As of October 2013, the FBI reported that their total number of special agents increased to 13,598, though the number allocated to counterterrorism was not stated.

There are additional analyses one can conduct using the framework developed above. For example, while most of the plots in the United States sample discussed above were “lone wolf” attempts by individuals or small groups to wreak havoc, it is well known that many terrorist organizations behave in strategic fashion and are able to adapt their behavior to counterterror policy and tactics. This leads to a game theoretic model where strategic terrorists who understand how socially efficient staffing works modify their own attempted attack rates in accord with their own benefit-cost calculus. In this game, the resulting optimal terror plot detection level depends upon the costs and benefits that terrorists assign to terror attacks, which provides yet another example of how strategic terrorists can manipulate counterterror agencies (or governments more broadly) to achieve their objectives.

The post The economics behind detecting terror plots appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesReplication redux and Facebook dataAre wolves endangered with extinction in Alaska?Understanding the local economic impacts of projects and policies

Related StoriesReplication redux and Facebook dataAre wolves endangered with extinction in Alaska?Understanding the local economic impacts of projects and policies

Does the class come out of the person after the person comes out of the class?

Does the class come out of the person after the person comes out of the class? This question asks us to think about social class inequality in a new way. It asks us to think not only of how much inequality exists in the United States, but how long inequality affects individuals. It also asks us to think of class not just as what we have — money, wealth, an occupation, an education — but also in terms of more personal characteristics — perceptions of who we are, what we want, and how to live our everyday lives. These personal characteristics are not trivial. They are judged by employers, schools, and potential friends; they can have profound effects on our opportunities.

So does the class come out of the person after the person comes out of the class? A study of individuals with working-class roots who graduate from college, enter the professional workforce, marry a spouse who has spent his or her entire life in the middle-class, and raise a family in a middle-class community indicates that the answer is no. Despite immersion in a new class, people with working-class roots still prefer different approaches to daily life than people with middle-class roots, even when they share a class position as adults. Moreover, not only are there differences, but the differences are systematic. College-educated adults with working-class roots generally prefer a laissez-faire lifestyle — one in which they can go with the flow, live in the moment, and feel free from self-imposed constraints. College-educated adults with middle-class roots, on the other hand, tend to prefer a managerial style — they prefer to organize, plan, and oversee. These differences span many aspects of individuals’ lives, including how they want to spend money, attend to paid work, allocate housework, raise their children, engage in downtime, and express emotions.

South San Jose by Sean O’Flaherty. CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

South San Jose by Sean O’Flaherty. CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.These differences are revealing. They show that to do well in America’s schools, universities, and workplaces, assimilation to middle-class norms is not required. At the same time, there are likely opportunities that working-class-origin adults miss due to their cultural differences from the middle-class. Workplaces often have unspoken norms that valorize middle-class culture, and upwardly mobile individuals with working-class roots are at risk of being penalized for not knowing or abiding by these norms. In this way, the long arm of social class socialization can even limit the opportunities of the people who embody the very idea of the American Dream.

The unlikeliness of taking the class out of the person after taking the person out of the class also sheds light on timely political debates. Commentators such as Charles Murray and David Brooks advocate stemming social class inequality by having the rich rub shoulders with the poor. They believe that if the rich preach what they practice, the poor will change their mindsets and inequality will be alleviated. The effectiveness of such programs must be questioned if four years of college, decades of professional work, and thousands of days married to a person born into another class does not take the class out of the person after taking the person out of the class. A more effective strategy may be to follow the lead of some of the middle-class spouses married to partners with working-class roots by appreciating the diversity of approaches that come from growing up in different class conditions.

The post Does the class come out of the person after the person comes out of the class? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMartin Luther King, Jr. on courage, equality, and justiceReplication redux and Facebook dataSovereign equality today

Related StoriesMartin Luther King, Jr. on courage, equality, and justiceReplication redux and Facebook dataSovereign equality today

Salamone Rossi as a Jew among Gentiles

Grove Music Online presents this multi-part series by Don Harrán, Artur Rubinstein Professor Emeritus of Musicology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, on the life of Jewish musician Salamone Rossi on the anniversary of his birth in 1570. Professor Harrán considers three major questions: Salamone Rossi as a Jew among Jews; Rossi as a Jew among Christians; and the conclusions to be drawn from both. Previous installments include “Salamone Rossi, Jewish musician in Renaissance Mantua” and “Salamone Rossi as a Jew among Jews”.

As a Jewish musician working for the Mantuan court, and competing for the favors that its Christian musicians and composers hoped to gain, it was only inevitable for Rossi to have been considered an intruder. His talents as composer and violinist must have been so remarkable that the dukes decided to keep him in their service over the course of almost forty years, from 1589 to 1628. In his publications he was designated an ebreo, but the very fact that he published so widely suggests that the quality of the music must have been more important than his Judaism.

Still, in Rossi’s dealings with the authorities, his Judaism was a bone of contention. For one thing, because of Jewish holidays and the Sabbath, Rossi was not always available when needed. For another, he could not be expected, when asked to do so, to write music to texts with Christian content. We know from a letter of Claudio Monteverdi that the ducal palace ran concerts of chamber music on Friday evenings, yet Rossi, who observed the Sabbath, would not have been present. We also know that of the various composers who were asked to write music for La Maddalena, a “sacred representation” about the sins and penitence of Mary Magdalen, Rossi was the only one to be assigned, at his request, a secular poem. The piece he wrote for it was “Spazziam pronte”.

ISIS’s unpredictable revolution

ISIS’s unpredictable revolution

Top 10 commercial law cases of 2014

Commercial law experienced an eventful year in 2014, but what were the most significant cases? Read our run-down of some of the biggest cases from the past 12 months to see if you agree with us:

1. Apple Inc. wins decade-long anti-trust class action

In December 2014, Apple won a long-running class action that was brought against them in 2005. The company was accused of monopolizing the digital music market and violating U.S. anti-trust statutes by reconfiguring its DRM system, which prevented mp3 compatibility with competitors. After 10 years of no judgement, and a recorded video statement from the late Steve Jobs, a jury ruled in Apple’s favour.

2. Russian oligarchs in mining row

A dispute between Russian aluminium businessman, Vasily Anisimov and the late Badri Patarkatsishvili’s family was settled in March 2014. The family alleged that they were entitled to 20% of Mr Anisimov’s mining company, claiming that the two businessmen agreed Mr Anisimov would invest in mining company Metalloinvest’s forerunner, Mikhailovsky. A deal was reached over the $1.8bn case just days before it was to go to trial.

3. Burwell vs. Hobby Lobby

A landmark decision made by the U.S. Supreme Court has allowed for-profit corporations to be exempt from certain laws on the grounds of religious beliefs held by company owners. The lawsuit was filed by Hobby Lobby owners, David and Barbara Green, who objected to having to provide contraceptives to employees through a health insurance plan, which they felt contravened their religious beliefs. The court ruled in their favour in June. This is the first time a court has recognised a for-profit corporation’s claim of religious beliefs.

Hobby Lobby in Mansfield, Ohio, by Nicholas Eckhart. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Hobby Lobby in Mansfield, Ohio, by Nicholas Eckhart. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.4. Accolade Wines in construction strife

In what was a huge £170m case in the Technology and Construction Court, Accolade Wines claimed against the company that built its bottling plant in 2010 for property damage and business interruption. Accolade Wines sued contractor VolkerFitzpatrick after finding problems with the floor slabs in their Bristol warehouse, which is the biggest wine warehouse in Europe. VolkerFitzpatrick denied the defects were due to their work.

5. Oracle Corp vs. Google

In May 2014 the Federal Circuit revised a decision made in 2012 that said Application Programming Interfaces (APIs or “Android operating systems”) are not copyrightable. Despite ruling in 2012 that if APIs were subject to copyright, this could allow a particular company to have control over “a utilitarian and functional set of symbols”, which could in turn prevent innovation within the technology industry. The Federal Circuit, however, decided in May that Java’s APIs are copyrightable, and Google’s case has gone back to trial.

Google’s café, by brion. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

Google’s café, by brion. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.6. America Broadcasting Companies vs. Aereo

Industrious start-up Aereo came up with a unique business opportunity by streaming broadcast network television programming online for a fee. The business was sued by a group of broadcasters and the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that their service violated copyright laws. The decision ultimately, of course, put Aereo out of business.

7. Tyre-d of price-fixing

A group of tyre manufacturers claimed against the Dow Chemical Company for damages over £170m, for price-fixing on polyurethane chemical products. Dow appealed the decision in October 2014, but this was denied by the 10th Circuit in the U.S in one of the most significant verdicts last year. The European Commission fined 10 companies more than £396m in this price-fixing case, including Shell and Bayer, as well as Dow.

Tyre, by William Warby. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Tyre, by William Warby. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.8. Bancroft vs. Weil Gotshal & Manges

In what will be the first time a U.S. company defends itself in a London court, private equity group Bancroft is suing American law firm, Weil Gotshal & Manges, for negligence in a claim worth an estimated £10m. The case is based on a claim that it was not explained during Weil Gotsham & Manges’ advise on Bancroft’s purchase of a 94% stake in ice cream company, Frost, that the group would not have voting control in the new company. The case was settled at £3m.

9. The National Grid take on a cartel

In June 2014 a group of companies were taken to trial in London after the European Commission identified a cartel relating to Gas Insulated Switchgear (GIS). Companies involved were fined €750m by the Commission while National Grid sought £360m in damages.

10. Mineworker pensioners take on RBS

RBS is currently in the firing line in one of the most significant post-recession pieces of litigation, as 77 claimants take the bank to task. The bank is accused of issuing “mis-statements and omissions” in its prospectus for the RBS April 2008 rights issue, as well as portraying themselves as being in a good financial position despite this not being the case. The claimants include pension scheme trustees, local authorities and investment funds. The total amount the bank is being sued for is estimated at over £3bn.

Featured image credit: UK Festival of Fireworks , by David Carter. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr

The post Top 10 commercial law cases of 2014 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy must we pay attention to the law of pension trusts?A guide to European cartelsSovereign equality today

Related StoriesWhy must we pay attention to the law of pension trusts?A guide to European cartelsSovereign equality today

January 19, 2015

Martin Luther King, Jr. on courage, equality, and justice

Each January, Americans commemorate the birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr., reflecting on the enduring legacy of the legendary civil rights activist. From his iconic speech at the 1963 March on Washington, to his final oration in Memphis, Tennessee, King is remembered not only as a masterful rhetorician, but a luminary for his generation and many generations to come. These quotes, compiled from the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, demonstrate the reverberating impact of his work, particularly in a time of great social, political, and economic upheaval.

On courage:

“A riot is at bottom the language of the unheard.”

Where Do We Go From Here? (1967) ch. 4

“If a man hasn’t discovered something he will die for, he isn’t fit to live.”

Speech in Detroit, 23 June 1963, in James Bishop The Days of Martin Luther King (1971) ch. 4

“Cowardice asks the question, ‘Is it safe?’ Expediency asks the question, ‘Is it politic?’ Vanity asks the question, ‘Is it popular?’ But Conscience asks the question, ‘Is it right?’”

Speech, 1967; in Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr. (1999) ch. 30

On equality:

“I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood…I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character.”

Speech at Civil Rights March in Washington, 28 August 1963, in New York Times 29 August 1963; see also jackson 413:13

“Returning hate for hate multiplies hate, adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars. Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.”

Strength to Love (1963) ch. 5, pt. 2

On justice:

“Judicial decrees may not change the heart; but they can restrain the heartless.”

Speech in Nashville, Tennessee, 27 December 1962, in James Melvin Washington (ed.) A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings of Martin Luther King, Jr. (1986) ch. 22

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Letter from Birmingham Jail, Alabama, 16 April 1963, in Atlantic Monthly August 1963

“We shall overcome because the arc of a moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

Sermon at the National Cathedral, Washington, 31 March 1968, in James Melvin Washington A Testament of Hope (1991); see obama 571:3, parker 585:12

On inaction:

“The Negro’s great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the White Citizens Councillor or the Ku Klux Klanner but the white moderate who is more devoted to order than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice.”

Letter from Birmingham Jail, Alabama, 16 April 1963, in Atlantic Monthly August 1963

“We will have to repent in this generation not merely for the hateful words and actions of the bad people, but for the appalling silence of the good people.”

Letter from Birmingham Jail, Alabama, 16 April 1963

Image Credit: Tribute to Martin Luther King, Jr. Photo by U.S. Embassy New Delhi. CC by ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Martin Luther King, Jr. on courage, equality, and justice appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories10 quotes to inspire a love of winterSovereign equality todayOf black holes, naked singularities, and quantum gravity

Related Stories10 quotes to inspire a love of winterSovereign equality todayOf black holes, naked singularities, and quantum gravity

Replication redux and Facebook data

Replication redux, by Nathaniel BeckIntroduction, from Michael Alvarez, co-editor of Political Analysis

Recently I asked Nathaniel Beck to write about his experiences with research replication. His essay, published on 24 August 2014 on the OUPblog, concluded with a brief discussion of a recent experience of his when he tried to obtain replication data from the authors of a recent study published in PNAS, on an experiment run on Facebook regarding social contagion. Since then the story of Neal’s efforts to obtain this replication material have taken a few interesting twists and turns, so I asked Neal to provide an update — because the lessons from his efforts to get the replication data from this PNAS study are useful for the continued discussion of research transparency in the social sciences.

When I last wrote about replication for the OUPblog in August (“Research Replication in Social Science”), there was one smallish open question (about my own work) and one biggish question (on whether I would ever see the Kramer et al., “Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks”, replication file, which was “in the mail”). The Facebook story is interesting, so I start with that.

After not hearing from Adam Kramer of Facebook, even after contacting PNAS, I persisted with both the editor of PNAS (Inder Verma, who was most kind) and with the NAS through “well connected” friends. (Getting replication data should not depend on knowing NAS members!). I was finally contacted by Adam Kramer, who offered that I could come out to Palo Alto to look at the replication data. Since Facebook did not offer to fly me out, I said no. I was then offered a chance to look at the replication files in the Facebook office 4 blocks from NYU, so I accepted. Let me stress that all dealings with Adam Kramer were highly cordial, and I assume that delays were due to Facebook higher ups who were dealing with the human subjects firestorm related to the Kramer piece.

When I got to the Facebook office I was asked to sign a standard non-disclosure agreement, which I dec. To my surprise this was not a problem, with the only consequence being that a security officer would have had to escort me to the bathroom. I then was put in a room with a Facebook secure notebook with the data and R-studio loaded; Adam Kramer was there to answer questions, and I was also joined by a security person and an external relations person. All were quite pleasant, and the security person and I could even discuss the disastrous season being suffered by Liverpool.

I was given a replication file which was a data frame which had approximately 700,000 rows (one for each respondent) and 7 columns containing the number of positive and negative words used by each respondent as well as the total word count of each respondent, percentages based on these numbers, experimental condition. and a variable which omitted some respondents for producing the tables. This is exactly the data frame that would have been put in an archive since it contained all the data needed to replicate the article. I also was given the R-code that produced every item in the article. I was allowed to do anything I wanted with that data, and I could copy the results into a file. That file was then checked by Facebook people and about two weeks later I received the entire file I created. All good, or at least as good as it is going to get.

Intel team inside Facebook data center. Intel Free Press. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Intel team inside Facebook data center. Intel Free Press. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. The data frame I played with was based on aggregating user posts so each user had one row of data, regardless of the number of posts (and the data frame did not contain anything more than the total number of words posted). I can understand why Facebook did not want to give me the data frame, innocuous as it seemed; those who specialize in de-de-identifying private data and reverse engineering code are quite good these days, and I can surely understand Facebook’s reluctance to have this raw data out there. And I understand why they could not give me all the actual raw data, which included how feeds were changed and so forth; this is the secret sauce that they would not like reverse engineered.

I got what I wanted. I could see their code, could play with density plots to get a sense of words used, I could change the number of extreme points dropped, and I could have moved to a negative binomial instead of a Poisson. Satisfied, I left after about an hour; there are only so many things one can do with one experiment on two outcomes. I felt bad that Adam Kramer had to fly to New York, but I guess this is not so horrible. Had the data been more complicated I might have felt that I could not do everything I wanted, and running a replication with 3 other people in a room is not ideal (especially given my typing!).

My belief is that that PNAS and the authors could simply have had a different replication footnote. This would have said that the code used (about 5 lines of R, basically a call to a Poisson regression using GLM) is available at a dataverse. In addition, they could have noted that the GLM called used the data frame I described, with the summary statistics for that data frame. Readers could then see what was done, and I can see no reason for such a procedure to bother Facebook (though I do not speak for them). I also note a clear statement on a dataverse would have obviated the need for some discussion. Since bytes are cheap, the dataverse could also contain whatever policy statement Facebook has on replication data. This (IMHO) is much better than the “contact the authors for replication data” footnote that was published. It is obviously up to individual editors as to whether this is enough to satisfy replication standards, but at least it is better than the status quo.

What if I didn’t work four blocks from Astor Place? Fortunately I did not have to confront this horror. How many other offices does Facebook have? Would Adam Kramer have flown to Peoria? I batted this around, but I did most of the batting and the Facebook people mostly did no comment. So someone else will have to test this issue. But for me, the procedure worked. Obviously I am analyzing lots more proprietary data, and (IMHO) this is a good thing. So Facebook, et al., and journal editors and societies have many details to work out. But, based on this one experience, this can be done. So I close this with thanks to Adam Kramer (but do remind him that I have had auto-responders to email for quite while now).

On the more trivial issue of my own dataverse, I am happy to report that almost everything that was once on an a private ftp site is now on my Harvard dataverse. Some of this was already up because of various co-authors who always cared about replication. And on stuff that was not up, I was lucky to have a co-author like Jonathan Katz, who has many skills I do not possess (and is a bug on RCS and the like, which beats my “I have a few TB and the stuff is probably hidden there somewhere”). So everything is now on the dataverse, except for one data set that we were given for our 1995 APSR piece (and which Katz never had). Interestingly, I checked the original authors’ web sites (one no longer exists, one did not go back nearly that far) and failed to make contact with either author. Twenty years is a long time! So everyone should do both themselves and all of us a favor, and build the appropriate dataverse files contemporaneously with the work. Editors will demand this, but even with this coercion, this is just good practice. I was shocked (shocked) at how bad my own practice was.

Heading image: Wikimedia Foundation Servers-8055 24 by Victorgrigas. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Replication redux and Facebook data appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGary King: an update on DataverseAre wolves endangered with extinction in Alaska?Cold War air hijackers and US-Cuban relations

Related StoriesGary King: an update on DataverseAre wolves endangered with extinction in Alaska?Cold War air hijackers and US-Cuban relations

Sovereign equality today

To speak of sovereign equality today is to invite disdain, even outright dismissal. In an age that has become accustomed to compiling “indicators“ of “state failure,” revalorizing nineteenth-century rhetoric about “great powers,” and circumventing established models of statehood with a nebulous “responsibility to protect,” sovereign equality seems little more than a throwback to a simpler, less complicated era.

To be sure, as a general principle, sovereign equality remains foundational to both customary and conventional international law. Article 2(1) of the UN Charter retains its nominally sacrosanct status, a foundational point of reference for a modern international law that promised to do away with the “standard of civilization”. Similarly, all the other classic articulations of independence and non-interference, especially the 1970 Friendly Relations Declaration, continue to be invoked, often with much the same spirit of solemnity.

Yet a great deal has also changed in recent decades. We have grown familiar to hearing that borders are no longer what they once were (or what, at any rate, they were once imagined to be). Traversed by goods, services, people, and capital, not to mention information, territorial frontiers have been characterized by wave upon wave of globalization theory as “fluid” and “porous”. Likewise, conventional legal models of recognition and jurisdiction have come under intense criticism. Among other things, the colonization of large chunks of international law scholarship by political science has generated a large literature on “rogue states”.

Not surprisingly, such developments have put the very idea of sovereign equality under pressure. And this, in turn, has had significant systemic consequences for international law as a whole.

Of course, sovereign equality is not without its problems. The principle has legitimated the very injustice it is purportedly designed to combat, enshrouding real inequality in a purely notional equality. After all, in itself, a bare assertion that states are equal and endowed with the same legal personality does remarkably little to rectify actually existing inequalities. Worse still, “rights of sovereignty” have been invoked to justify all manner of abuses, typically by national elites determined to augment and consolidate their class power.

Part of the difficulty here is that far from being inherently “progressive”, sovereign equality is a concept with a rather murky pedigree. While its roots reach back centuries, the principle assumed strong doctrinal form during the nineteenth century by way of the Concert of Europe’s commitment to the European balance of power. This commitment was typically premised upon the impermissibility of intervention in “civilized” states and the permissibility of intervention in “uncivilized” and “semi-civilized” regions. That is hardly an ideal foundation for an emancipatory principle.

All of this is true. But it is also worth keeping in mind that sovereign equality has frequently furnished politically and economically weaker states with a measure of protection against aggression and intervention. As a response to de facto inequality, international lawyers instinctively prioritize de jure equality. Absent such insistence on formally equal rights and obligations, it is often assumed, the will and interests of some states would be subordinated to the will and interests of other states, with predictably dire implications for international legal order.

To underscore the significance of sovereign equality today is not to cling to an outdated mode of conceiving international relations. Nor is it to deny that sovereign power has its “dark sides”. It is simply to stress the need for greater appreciation of the fact that sovereignty may under certain circumstances provide a buffer against some of the most direct and explicit forms of inter-state violence. It is worth recalling that the history of international law is to no small degree the history of attempts to secure recognition for (one or another account of) sovereign equality. This is anything but a puerile pursuit.

Headline image credit: Map of the world. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Sovereign equality today appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFear vs terror: signal crimes, counter-terrorism, and the Charlie Hebdo killingsInternational Law at Oxford in 2014Is international law just?

Related StoriesFear vs terror: signal crimes, counter-terrorism, and the Charlie Hebdo killingsInternational Law at Oxford in 2014Is international law just?

Of black holes, naked singularities, and quantum gravity

Modern science has introduced us to many strange ideas on the universe, but one of the strangest is the ultimate fate of massive stars in the Universe that reached the end of their life cycles. Having exhausted the fuel that sustained it for millions of years of shining life in the skies, the star is no longer able to hold itself up under its own weight, and it then shrinks and collapses catastrophically unders its own gravity. Modest stars like the Sun also collapse at the end of their life, but they stabilize at a smaller size. But if a star is massive enough, with tens of times the mass of the Sun, its gravity overwhelms all the forces in nature that might possibly halt the collapse. From a size of millions of kilometers across, the star then crumples to a pinprick size, smaller than even the dot on an “i”.

What would be the final fate of such massive collapsing stars? This is one of the most exciting questions in astrophysics and modern cosmology today. An amazing inter-play of the key forces of nature takes place here, including gravity and quantum forces. This phenomenon may hold the secrets to man’s search for a unified understanding of all forces of nature, with exciting implications for astronomy and high energy astrophysics. Surely, this is an outstanding unresolved mystery that excites physicists and the lay person alike.

The story of massive collapsing stars began some eight decades ago when Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar probed the question of final fate of stars such as the Sun. He showed that such a star, on exhausting its internal nuclear fuel, would stabilize as a “White Dwarf”, about a thousand kilometers in size. Eminent scientists of the time, in particular Arthur Eddington, refused to accept this, saying how a star can ever become so small. Finally Chandrasekhar left Cambridge to settle in the United States. After many years, the prediction was verified. Later, it also became known that stars which are three to five times the Sun’s mass give rise to what are called Neutron stars, just about ten kilometers in size, after causing a supernova explosion.

But when the star has a mass more than these limits, the force of gravity is supreme and overwhelming. It overtakes all other forces that could resist the implosion, to shrink the star in a continual gravitational collapse. No stable configuration is then possible, and the star which lived millions of years would then catastrophically collapse within seconds. The outcome of this collapse, as predicted by Einstein’s theory of general relativity, is a space-time singularity: an infinitely dense and extreme physical state of matter, ordinarily not encountered in any of our usual experiences of physical world.

Cradle of stars, photo by Scott Cresswell CC-by-2.0 via Flickr

Cradle of stars, photo by Scott Cresswell CC-by-2.0 via Flickr As the star collapses, an ‘event horizon’ of gravity can possibly develop. This is essentially ‘a one way membrane’ that allows entry, but no exits permitted. If the star entered the horizon before it collapsed to singularity, the result is a ‘Black Hole’ that hides the final singularity. It is the permanent graveyard for the collapsing star.

As per our current understanding of physics, it was one such singularity, the ‘Big Bang’, that created our expanding universe we see today. Such singularities will be again produced when massive stars die and collapse. This is the amazing place at boundary of Cosmos, a region of arbitrarily large densities billions of times the Sun’s density.

An enormous creation and destruction of particles takes place in the vicinity of singularity. One could imagine this as ‘cosmic inter-play’ of basic forces of nature coming together in a unified manner. The energies and all physical quantities reach their extreme values, and quantum gravity effects dominate this regime. Thus, the collapsing star may hold secrets vital for man’s search for a unified understanding of forces of nature.

The question then arises: Are such super-ultra-dense regions of collapse visible to faraway observers, or would they always be hidden in a black hole? A visible singularity is sometimes called a ‘Naked Singularity’ or a ‘Quantum Star’. The visibility or otherwise of such super-ultra-dense fireball the star has turned into, is one of the most exciting and important questions in astrophysics and cosmology today, because when visible, the unification of fundamental forces taking place here becomes observable in principle.

A crucial point is, while gravitation theory implies that singularities must form in collapse, we have no proof the horizon must necessarily develop. Therefore, an assumption was made that an event horizon always does form, hiding all singularities of collapse. This is called ‘Cosmic Censorship’ conjecture, which is the foundation of current theory of black holes and their modern astrophysical applications. But if the horizon did not form before the singularity, we then observe the super-dense regions that form in collapsing massive stars, and the quantum gravity effects near the naked singularity would become observable.

“It turns out that the collapse of a massive star will give rise to either a black hole or naked singularity”

In recent years, a series of collapse models have been developed where it was discovered that the horizon failed to form in collapse of a massive star. The mathematical models of collapsing stars and numerical simulations show that such horizons do not always form as the star collapsed. This is an exciting scenario because the singularity being visible to external observers, they can actually see the extreme physics near such ultimate super-dense regions.

It turns out that the collapse of a massive star will give rise to either a black hole or naked singularity, depending on the internal conditions within the star, such as its densities and pressure profiles, and velocities of the collapsing shells.

When a naked singularity happens, small inhomogeneities in matter densities close to singularity could spread out and magnify enormously to create highly energetic shock waves. This, in turn, have connections to extreme high energy astrophysical phenomena, such as cosmic Gamma rays bursts, which we do not understand today.

Also, clues to constructing quantum gravity–a unified theory of forces, may emerge through observing such ultra-high density regions. In fact, the recent science fiction movie Interstellar refers to naked singularities in an exciting manner, and suggests that if they did not exist in the Universe, it would be too difficult then to construct a quantum theory of gravity, as we will have no access to experimental data on the same!

Shall we be able to see this ‘Cosmic Dance’ drama of collapsing stars in the theater of skies? Or will the ‘Black Hole’ curtain always hide and close it forever, even before the cosmic play could barely begin? Only the future observations of massive collapsing stars in the universe would tell!

The post Of black holes, naked singularities, and quantum gravity appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesStardust making homes in spaceTime as a representation in physicsWhat is it like to be depressed?

Related StoriesStardust making homes in spaceTime as a representation in physicsWhat is it like to be depressed?

January 18, 2015

Seeing things the way they are

A few really disastrous mistakes have dominated Western philosophy for the past several centuries. The worst mistake of all is the idea that the universe divides into two kinds of entities, the mental and the physical (mind and body, soul and matter). A related mistake, almost as bad, is in our philosophy of perception. All of the great philosophers of the present era, beginning with Descartes, made the same mistake, and it colored their account of knowledge and indeed their account of pretty much everything. By ‘great philosophers’, I mean Locke, Berkeley, Hume, Descartes, Leibniz, Spinoza, and Kant. I am prepared to throw in Hegel and Mill if people think they are great philosophers too. I called this mistake the “Bad Argument”. Here it is: We never directly perceive objects and states of affairs in the world. All we ever perceive are the perceptual contents of our own mind. These are variously called ‘ideas’ by Descartes, Locke, and Berkeley, ‘impressions’ by Hume, ‘representations’ by Kant, and ‘sense data’ by twentieth century theorists. Most contemporary philosophers think they have avoided the mistake, but I do not think they have. It is just repeated in different versions, especially by a currently fashionable view called ‘Disjunctivism’.

But that leaves us with a more interesting problem: What is the correct account of the relation of perceptual experience and the real world? The key to understanding this relation is to understand the intentionality of perception. ‘Intentionality’ is an ugly word, but we can pretty much make clear what it means; a mental state is intentional if it represents, or is about, objects and states of affairs in the world. So beliefs, hopes, fears, desires are all intentional in this sense. ‘Intending’ in the ordinary sense just names one kind of intentionality, along with beliefs, desires, etc. Such intentional states are representations of how things are in the world or how we would like them to be, etc., and we might say therefore that they have “conditions of satisfaction” — truth conditions in the case of belief, fulfillment conditions in the case of intentions, etc.

The biologically most basic and gutsiest forms of intentionality are those where we don’t have mere representations but direct presentations of objects and states of affairs in the world, and part of intentionality is that these must be causally related to the conditions in the world that they present. Perception and intentional action are direct presentations of their conditions of satisfaction. In the case of perception, the conditions of satisfaction have to cause the perceptual experience. In the case of action, the intention in action has to cause the bodily movement. So the key to understanding perception is to see the special features of the causal presentational intentionality of perception. The tough philosophical question is to state how exactly the character of the visual experience, its phenomenology, determines the conditions of satisfaction.

How then does the intentional content fix the conditions of satisfaction? The first step in the answer is to see that perception is hierarchical. In order to see higher level features, such that an object is my car, I have to see such basic features as color and shape. The key to understanding the intentionality of the basic perceptual experience is to see that the feature itself is defined in part by its ability to cause a certain sort of perceptual experience. Being red, for example, consists in part in the ability to cause this sort of experience. Once the intentionality of the basic perceptual features is explained, we can then ask the question of how the presentation of the higher level features, such as seeing that it is my car or my spouse, can be explained in terms of the intentionality of the basic perceptual experiences together with collateral information.

How do we deal with the traditional problems of perception? How do we deal with skepticism? The traditional problem of skepticism arises because exactly the same type of experience can be common to both the hallucinatory and the veridical cases. How are we supposed to know which is which?

Image Credit: Marmalade Skies. Photo by Tom Raven. CC by NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Seeing things the way they are appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy causality now?What is it like to be depressed?“Sorry mate, I didn’t see you”: perceptual errors and inattentional blindness

Related StoriesWhy causality now?What is it like to be depressed?“Sorry mate, I didn’t see you”: perceptual errors and inattentional blindness

ISIS’s unpredictable revolution

The editors of Oxford Islamic Studies Online asked several experts the following question:

The world has watched as ISIS (ISIL, the “Islamic State”) has moved from being a small but extreme section of the Syrian opposition to a powerful organization in control of a large swath of Iraq and Syria. Even President Obama recently admitted that the US was surprised by the success of ISIS in that region. Why have they been so successful, and why now?

Sociologist Charles Kurzman of the University of North Carolina shares his thoughts.

Revolutions have been surprising experts for generations. After the Iranian Revolution of 1979, for example, the CIA commissioned a report into why it had predicted, 100 days before the fall of the monarchy, that the Shah‘s regime would ride out the protests. During the “Arab Spring” uprisings in 2011, President Obama reportedly chastized the intelligence community for not having warned him in advance. Academics have a similarly checkered track record.

The reason is that revolutions are inherently unpredictable. They depend on the interactions and perceptions of large numbers of people at moments of confusion when normal routines and institutions are breaking down.

After a revolution, though, it is common to demand explanations that make the unexpected seem inevitable. Many experts are happy to satisfy our desire for a causal narrative, selecting evidence from the run-up to revolution that might serve as a sort of retroactive prediction.

So why did a revolutionary group calling itself al-Daula al-Islamiyya fi’l-’Iraq wa’l-Sham (the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria) manage to occupy territory in Syria and Iraq in 2013 and 2014? I might point to its extreme violence (though the Iraqi and Syrian governments were capable of extreme violence as well), or its ideology of self-sacrifice (also visible among other Syrian revolutionary groups), or the support it received from foreign governments (no greater than the support that the governments received), or its leaders’ strategic brilliance (knowable only post hoc), or any number of other factors. These are stories we tell to make ourselves feel that the world is an orderly place, where even the events we find most outrageous or troubling can be tamed through the causal logic of social science.

The real story of the revolution is that one group with weapons persuaded other groups with weapons to surrender or retreat, instead of shooting back. It persuaded large numbers of unarmed civilians to obey them or flee, instead of mobbing the revolutionaries and handing them over to other groups with guns. Those moments of conquest, enacted in confusion and panic with lives on the line—that is how this revolution occurred.

This is part two of a series of articles discussing ISIS. Part one is by Hanin Ghaddar, Lebanese journalist and editor. Part two is by Shadi Hamid, fellow at the Brookings Institution.

Headline image: Yemeni Protests 4-Apr-2011 by Email4mobile. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post ISIS’s unpredictable revolution appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIdeology and a conducive political environmentISIS is an outcome of a much bigger problemFull-circle in the Middle East?

Related StoriesIdeology and a conducive political environmentISIS is an outcome of a much bigger problemFull-circle in the Middle East?

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers