Oxford University Press's Blog, page 691

March 7, 2015

Understanding modern Greece: a Q&A

Depending on who you are, you may think of Greece as the country that we know today or you may think of that ancient conglomerate of city-states from long ago. In arguing that Greece—or modern Greece—is, in fact, a trailblazer of sorts, Stathis N. Kalyvas, author of Modern Greece: What Everyone Needs to Know, gives us some very compelling insights for us to consider.

What is Greece’s lesser-known record of achievements?

Greece has frequently innovated, overcoming disasters and performing above expectations. It has a consistent record of punching above its weight. It was the first “new” nation to emerge out of the Ottoman Empire and it spearheaded an early democratic revolution, ushering in a long stretch of stable parliamentary rule. Military coups did take place, but the country experienced only three relatively short breaks in democratic governance from 1864 to the present: 1922–1929, 1936–1945, and 1967–1974. Despite difficulties, democracy was sustained by an egalitarian social structure, which was itself the outcome of a remarkably comprehensive and successful land reform. Greece was alone among its Balkan neighbors to escape communism. Its economic takeoff in the 1950s was so impressive that it became known as the “Greek economic miracle.” The 1974 transition to democracy set an example of how to peacefully exit autocracy and prosecute its leaders. Despite its current problems, Greece is a prosperous democracy and arguably the most successful post-Ottoman state.

What explains the love-hate relationship between Greece and the West?

The most sensitive issue in the relationship between Westerners and Greeks was the link between ancient and modern Greece. Every attempt to challenge this relationship—most famously by the Austrian writer Jakob Philipp Fallmerayer, who suggested in 1830 that modern Greeks were the descendants of Slavic peoples—caused an intense emotional reaction in Greece. The link between ancient and modern Greece remains a sensitive issue in Greece today, as it is simultaneously a cornerstone of Greek national identity and an expression of the nation’s pronounced insecurity.

How did democracy come to Greece?

Like most of its European contemporaries, the Greek state began life under a regime of absolute monarchy. Therefore, it is surprising to observe how quickly and smoothly democratic institutions were introduced and adopted in Greece. To be sure, these institutions did not emerge under ideal conditions. Greece lacked a well-functioning state, a sizable bourgeois class, a tradition of aristocratic representative institutions, an industrial working class, a strong liberal intellectual milieu, and a vigorous urban culture—all factors associated with the rise of democracy in nineteenth-century Europe. However, it did enjoy an important advantage, one that has been linked to the rise of democratic regimes: a relatively egalitarian social structure associated to the absence of a large landowning class.

“Greek flag.” Photo by Trine Juel. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

“Greek flag.” Photo by Trine Juel. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.What was the impact of the Great Depression?

In the economic history of Greece, the period between 1928 and 1932 stands outs as a time during which the drive for modernization gained substantial momentum. Under the premiership of Venizelos, the Greek government implemented a forceful “developmentalist” program that continued where Trikoupis’s program had stopped, turning the state into a much more forceful and proactive economic actor. The creation, for instance, of the Agricultural Bank of Greece in 1929 was a key element in the modernization of agriculture. The achievements brought by these measures were substantial, but their promise was only partially fulfilled because Greece was hit by an economic tempest unleashed by the 1929 US stock market crash and the Great Depression. Despite this, Greece managed to orchestrate a surprisingly effective response to the disaster, one largely based on economic autarky and the stimulation of the domestic market.

What was the effect of populism on social norms and behavior in Greece?

Greek society has always been highly suspicious of the state, which is seen as a hostile, extractive, and repressive entity. “Regulations, whenever they happened to interfere with individual and family self-interest, were obstacles to be overcome, not rules to be obeyed,” historian W.H. McNeill observes. “The more formidable the regulation, the more energetic the effort to escape its incidence and the greater the occasion for bribery.” As a result, society sought to deny state resources both by withholding them (e.g., evading taxation) and appropriating them (e.g., taking over public land). This behavior made sense in times of scarcity and limited political representation, but it is much harder to explain, let alone justify, under conditions of democracy and relative plenitude.

Image Credit:”Oia, Greece.” Photo by Jon Rawlinson. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Understanding modern Greece: a Q&A appeared first on OUPblog.

Religion and security after the Charlie Hebdo shootings

On 6 January 2015, I led a major event in the British Parliament at Westminster to launch and promote a recently completed survey of academic analysis and its policy implications, Religion, Security, and Global Uncertainties. The following day in Paris, the Houachi brothers shot dead twelve people in their attack on the magazine Charlie Hebdo, professedly to avenge its alleged insults to the Prophet Muhammad.

One of the central messages both of our report and of the presentations at its launch is that there is no simple cause and effect mechanism whereby “dangerous” ideas lead people to violent action. This insight remains very imperfectly understood as is apparent in both policy and media responses to recent events in France, Belgium, and Denmark which have emphasized both the heightening of hard security and the affirmation of the right of Charlie Hebdo and its sympathizers to continue to offend Muslims. The polarization of fanaticism against “free speech”, with the implication that the latter needs to be upheld by ever greater securitization, is unhelpful and potentially counterproductive.

The danger of a response that focuses on “Islamist extremism” as characterized rather stereotypically in the December 2013 Report of the Prime Minister’s Taskforce on Tackling Extremism in the UK is that it demonizes attitudes and beliefs that may be held by many mainstream and non-violent Muslims, such as legitimate criticism of Western interventions in the Islamic world. If Muslims are left feeling that views of this kind cannot be articulated in the public sphere while at the same time others are free to ridicule the Prophet, antagonism towards the perceived double standards that they face is likely only to grow. Hence the endeavor to seek out potential violent extremists risks accentuating the very problem it is intended to avert.

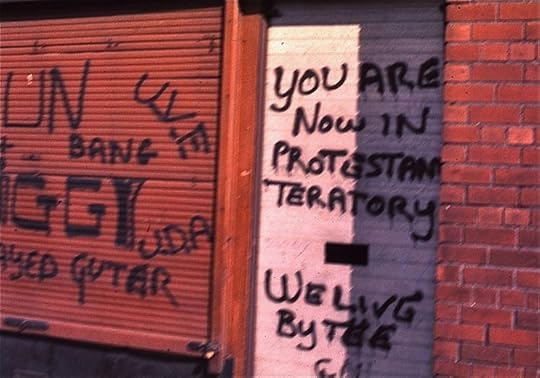

Protestant graffiti in Belfast, Northern Ireland, 1974, during The Troubles by GeorgeLouis. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikipedia.

Protestant graffiti in Belfast, Northern Ireland, 1974, during The Troubles by GeorgeLouis. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikipedia.It may well be useful to apply some of the lessons learned in Northern Ireland. Here the characteristic terrorist in the Troubles was a marginal rather than core adherent of their religious tradition, and specifically religious motivation was seldom a significant factor in their actions. Nevertheless the abiding use of the labels “Catholic” and “Protestant” to define the opposing forces in the conflict has engendered an enduring sense of estrangement and confrontation between contiguous communities. This is epitomized by the continuing need for “peace walls” in Belfast. Moreover the Northern Ireland experience also showed that communities that are subjected to a harsh securitized response are more rather than less likely to condone violent actions even when they do not actively support them.

There is an obvious tension, well explored by Martin Innes in his recent contribution to this blog, between the professional and political imperatives for the security forces to avert imminent terrorist attacks and the need for longer term policies that will mitigate the danger of such threats in the future. The emphasis of our report is though on the importance of understanding “security” in broad terms of enduring social stability rather than merely in narrow terms of identifying and controlling “clear and present danger”. To that end we particularly advocate the promotion of greater religious literacy, among policy-makers, the media, and the general public, as a means to avert unjustified but polarizing fears and to facilitate the identification of genuinely dangerous individuals. A better shared understanding of religion in general, and especially of the problematic interactions between global Islam and Western secularity, is much needed.

In particular, not only is there is a need not only better to appreciate the internal diversity of Islam, but also to recognize that secularity itself takes many different forms. The explicit secularism of French republicanism contrasts with the neutrality towards religion enshrined in the First Amendment to the American Constitution, and with the acceptance that religion still has a recognized if limited public role that is implicit in the continuing establishment of the Church of England.

The world beyond Western Europe is seeing a striking resurgence of religion, of Christianity as well as of Islam. In this context it is vital to recognize that short-term “security” measures are no substitute for serious long-term reflection on how a secular Europe can best live with its own substantial religious minorities.

Image credits: Cologne rally in support of the victims of the 2015 Charlie Hebdo shooting by Elya. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Religion and security after the Charlie Hebdo shootings appeared first on OUPblog.

Remembering women sentenced to death on International Women’s Day

In May 2014, in Sudan, Meriam Ibrahim was sentenced to death for the ‘crime’ of ridda (apostacy) and to 100 lashes for the ‘offence’ of zena (sexual immorality). The case generated international outrage among those who care about women’s rights and religious freedom. The penalty of death for behaviours that should never be criminalised caused indignation among retentionists as well as abolitionists. But the execution of women for acts deemed to be immoral is not unusual in some countries in the Middle East and Africa. This case appalled us primarily because of her status as a mother and the human rights implications for the protection of the family and the welfare of children. Mrs Ibrahim was pregnant while being held in prison with her 20-month-old son. She gave birth to her second child later in May, restrained by shackles.

Meriam’s case not only caused a global social media campaign, but it provoked an uncompromising stance from the United Nations, the European Union, foreign ministers from various governments, and the British parliament. Just a month after giving birth, the Court of Appeal in Khartoum North quashed her convictions and Miriam was released from custody to be reunited with her husband. The young family were soon on their way to the United States.

On International Women’s Day, it’s worth reflecting on the many other women around the world who are held in prisons, in sometimes dire conditions, who do not escape this cruel and inhuman treatment. They await their executioner, with little fuss made about them.

In the United States there are 59 women on death row, though only 15 have been executed since the reinstatement of capital punishment in 1976. Just a few weeks ago, Kelly Gissendaner made her last plea for clemency to the Georgia parole board, but few outside of this southern state will have heard about her. Linda Carty came dangerously close to execution in 2011 and still remains on death row, fighting for a retrial. She is better known to British people due to the efforts to overturn her apparently unsafe conviction made by the UK-based human rights charity, Reprieve, which works on behalf of British people imprisoned overseas. However, media reports remain few and far between and do not generate the public interest aroused by Meriam Ibrahim’s case.

As another middle-aged, British woman, without young dependents, Lindsay Sandiford similarly receives less attention. Lindsay – like the ‘Bali two’ Australians, Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran – awaits imminent execution in an Indonesian jail. Sentenced for drug smuggling, they are at the mercy of an Indonesian president who has made clear that he will deny clemency appeals from those convicted for drug offences. In stark contrast to the eagerness of politicians in Europe and the United States to assist Meriam, the British government has refused to fund legal advice and representation for Lindsay Sandiford.

Elsewhere in Asia, few people outside of Japan noticed when Sachiko Eto, an alleged ‘cult leader,’ was executed in 2012 following her conviction for murder. There remain six women on death row in Japan. One of them is Hayashi Masumi, a middle-aged woman convicted of poisoning a curry served at a 1998 summer festival in Wakayama (a rather unusual case, and a possible miscarriage of justice, but unlikely to generate international media interest). In the absence of young children, women are less ‘media-friendly’.

Dove. CC0 via Pixabay.

Dove. CC0 via Pixabay.Although there is no international norm barring the sentencing to death and execution of women in general, they have been exempted altogether from capital punishment in a few countries—mainly those associated with the former Soviet system. But they have been executed recently in Iran (at least 30 in 2013, the majority for drug trafficking), Vietnam, Afghanistan, Indonesia, and fairly frequently in China. In Saudi Arabia many women are beheaded for the types of behaviours for which Meriam Ibrahim was sentenced.

Article 6 (5) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights does not protect pregnant women from being sentenced to death but it does protect them from being executed. In 1984 the Economic and Social Council Resolution (1984/50; Safeguard 3) extended this protection from execution while those that were pregnant are ‘new mothers’. These safeguards have been almost universally accepted.

Almost all retentionist countries have introduced legislation to prohibit the execution of pregnant women. Indeed, in recent years there have been no reports of pregnant women or mothers with recently born children being executed. However, in some highly secretive jurisdictions, the picture is not entirely clear. For example, according to the International Federation for Human Rights pregnant women have reportedly undergone forced abortion in prison camps before being executed in North Korea.

The Death Penalty Worldwide website lists 33 countries that sentence pregnant women to death but delay the execution until after delivery and for varying periods while the infant is young; 22 countries always commute a death sentence that would have been imposed on a pregnant woman; six countries give the courts discretion as to whether the death sentence should be commuted immediately or after the woman’s delivery; and in 23 countries it is unclear as to whether the practice was immediate commutation to life or other long period of imprisonment or delay. Several countries – including Vietnam and Jordan – have commuted death sentences where a woman who was not pregnant when sentenced to death is later found to be pregnant.

Once a woman has given birth, some countries (such as Kuwait) automatically commute the sentence to imprisonment for life. However, not all do and the laws of several countries specify no minimum period before a woman who has given birth may be executed: the execution is merely ‘stayed’. Others set specific periods (40 days in Indonesia and Morocco; two months in Egypt and Libya; three months in Jordan and Bahrain; two years in Yemen, the Maldives and Thailand; and three years in the Central African Republic).

It is not easy to make the case that women should be ineligible for the death penalty in countries that have not abolished. They are not vulnerable in the way that juveniles, the mentally ill, and the learning disabled are. However, there is a growing concern about the emotional plight and care of children whose parents have been sentenced to death, as demonstrated by a recent Quaker report, Lightening the Load. In 2013 the UN Human Rights Council considered whether imposing the trauma of a death sentence or execution on a parent is a violation of the rights of the child under the International Covenant. This issue is unresolved, but while there is growing concern about the collateral abuses of human rights inevitably caused by the imposition of the death penalty, we should use this day to remember all mothers around the world who live under the shadow of death, no matter how old their children are. While we do, we should not forget all the other women and men who suffer this cruel and inhuman treatment.

The post Remembering women sentenced to death on International Women’s Day appeared first on OUPblog.

A quiz on nineteenth century nuns

In 1858, German Princess Katharina von Hohenzollern entered the strict Franciscan convent of Sant’Ambrogio della Massima. Instead of finding the solitude and peace she was looking for, she stumbled across a sex scandal of ecclesiastical proportions filled with poison, murder, and lesbian initiation rites. Based on Hubert Wolf’s vividly reconstructed telling of the scandal, we’ve created a short quiz where you can try your hand and unravel the secrets of the Sant’Ambrogio convent.

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Interested in finding out more about the Nuns of Sant’Ambrogio? Check out the author’s previous post about re-telling this scandalous story in the twenty-first century.

Featured image credit: St Peter’s, Rome, by Phillip capper. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A quiz on nineteenth century nuns appeared first on OUPblog.

March 6, 2015

Reflections on the ‘urge to collect’

In the most recent issue of the Oral History Review, Linda Shopes started an important discussion about changes she has seen in the field of oral history. Below, we bring to you a continuation of this conversation through an email interview. If you haven’t read her article, “‘Insights and Oversights’: Reflections on the Documentary Tradition and the Theoretical Turn in Oral History”, you can access it at the link above. If you’d like to chime into the discussion, you can comment below or on our Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or G+ pages.

In your article you suggest oral historians should focus on curating as opposed to collecting. Can you talk a bit about what that process looks like? What would it mean to create an oral history project that sets out to curate instead of collect?

What I am suggesting here is something like “less is more” or maybe “less so we can do better.” While there’s always room for more interviews on poorly documented subjects, do we really need more interviews to add to the hundreds – probably thousands – we already have with World War II veterans, for example? Maybe we do, but before embarking on them, I’d like to hear a justification. And I’d like planners to think about creative ways of getting in and around the topics at hand, of extending them outward. It seems to me that many interviews are very constricted in scope. Of course, I understand why a classroom or local history project might like to undertake a veterans project, but then I’d ask, is the quality of these interviews sufficient to warrant the time and money necessary to preserve them permanently and make them accessible? How many collections are already languishing in archives with little attention to what’s needed to maintain their physical integrity or to develop appropriate finding aids and means of access – not because staff are careless or inattentive but because there simply aren’t the resources to do so?

As I think I said in the article, “to create an oral history project that sets out to curate instead of collect” means that, at the outset, the value of the project is clearly articulated – the “so what?” question answered carefully. This would include a search for other interviews on the subject and, if they exist, an assessment of whether more interviews are really needed. It means rigorous assessment of interviews during the course of the project – not just at the end, and based on that assessment, appropriate adjustments of method. It means that the scope of the project includes making the interviews accessible – not just physically accessible but intellectually accessible, adding value by developing mechanisms for facilitating and encouraging use. To me “curate” means both caring for interviews and exercising critical judgment about quality, a measure of selectivity. But to be clear, I do understand that repositories may have missions and collecting practices that aren’t especially hospitable to this approach. I am speaking more or less of what to me would be a preferred practice, not a policy that everyone might wish or be able to implement. But I think it’s an idea worth discussing.

I just wish people would slow down a bit and consider the urge to collect.

It seems like there are two problems with the drive to collect oral histories: a lack of critical analysis of the interviews, and the sheer magnitude of interviews available, making it harder to find the “good stuff.” Which problem are you more concerned with?

It seems to me that they are inseparable: If by critical analysis of interviews you mean that we have collections that have never been assessed for quality, that has certainly been the case, a situation related in part to the “sheer magnitude” problem. If you mean that interviews themselves have never been used in a critical study, that too is certainly the case and linked in part to both the lack of access and the “sheer magnitude” issue. Of course, saying this doesn’t obviate the fact that someone working on a given topic may be frustrated by the lack of extant interviews pertinent to that topic. The reverse is also true: finding the “good stuff” is in part related to “lack of critical analysis,” especially in the first sense noted here.

More generally, I’d say doing interviews is the “sexy” part of oral history. I just wish people would slow down a bit and consider the urge to collect. Particularly they need to ask: Why is it important to interview on this particular topic? What are the unanswered questions and how can interviews address them? How can we incorporate quality control in the oral history process? How can we facilitate access and use once the interviews are done? I know that sometimes the urgency of the moment may make consideration of these issues a luxury, but I believe it’s necessary to do so.

But if pressed to choose between the two problems you point out, I’d have to say the former. Partly it’s temperamental – quality at the outset seems of primary importance to me, with the challenge of wading through piles of material to find the gold less so. It’s a problem researchers often face with sources in general. But I also think that if we were more rigorous in developing high quality interviews, we’d have fewer interviews to have to work though. And more “good stuff” in those that are available.

Towards the end of your article you say, “part of our job, I submit, is to make clear the connections between the ‘I’ of the interview and the ‘we’ of the rest of the world.” Can you talk about ways or places you’ve seen this done well?

I’m still working out what I mean by that statement – it points towards what I’ll take up in a second essay. Partly, I mean that we need to get oral history out of the archives and do something with it. And that can take many forms, from books to websites, films to dramatic presentations, public dialogues to walking tours. Partly, I mean that while each person’s story is, of course, unique, it’s also part of a larger story of life at a particular time and place and encodes a whole range of underlying relationships and structures. And we need to draw attention to that. Partly, I mean what Paul Thompson said: “All history depends ultimately upon its social purpose.” Of course, even an interview buried in an archive for decades serves a social purpose, but I mean something more active – we need to put oral history to work in the present to inform and inspire, to give depth and meaning to everyday experiences, to engage with and support broader issues and concerns.

But thinking about what you’ve quoted back to me, I’d have to confess that it was, at least in part, provoked by my discontent with the sort of so-called theoretical work I critiqued earlier in the essay – obscurantist work that does little work in the world. But perhaps I implied that oral historians aren’t making the connections I’m suggesting – they are. The Densho Project, which uses oral history to raise awareness about the incarceration (their preferred term) of Japanese Americans during World War II and larger questions of equal justice in a democracy, comes to mind immediately. And the work of participants in the Groundswell network, who use oral history to further social change. I just read Amy Starecheski’s article in the current issue of the Oral History Review – that’s another example. Also the work of winners of OHA’s Stetson Kennedy prize.

I’d like to think that the books published in Palgrave Macmillan’s Studies in Oral History series, which I coedited for several years, have social meaning. D’Ann Penner and Keith Ferdinand’s Overcoming Katrina: African American Voices from the Crescent City and Beyond has been used in various public forums addressing the social – as opposed to environmental – consequences of the hurricane. Also, interviews in Desiree Hellegers’s No Room of Her Own: Women’s Stories of Homelessness, Life, Death, and Resistance are being crafted into play to raise public awareness about the causes and conditions of homelessness among women. In each case, the oral historians were motivated by a clear social purpose. And going back a few decades, there’s the work of people like Jeremy Brecher, whose Brass Valley project relied largely on oral history to reframe the public debate about deindustrialization in Connecticut’s Naugatuck Valley, and Jack Tchen, whose interviews with Chinese laundrymen in New York in the 1980s were the seed of what became the Museum of Chinese in America.

There is something intrinsic to oral history that matters beyond simply adding to the store of information we have about our world.

I hear rumors that you’re working on a follow up piece to “Insights and Oversights” for an upcoming issue of the Oral History Review. Care to tease us with some of the details here?

As I’ve suggested, I’m still working out the ideas in that piece. But in general, what I’m doing is considering some of the issues that arise when we move oral history out of the archives and into the public sphere, looking at the presentational form I’m most familiar with – that is, publications. I’ll look at some of the ethical issues at stake, the sometimes conflicting claims on our work, and how various authors have addressed them. What I’m arguing, I think (and I have to thank OHR editor Kathy Nasstrom for seeing this in an early draft), is that there is something intrinsic to oral history that matters beyond simply adding to the store of information we have about our world. And that has consequences for our work.

Image Credit: “Video Tape Archive Storage” by DRs Kulturarvsprojekt. CC by SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Reflections on the ‘urge to collect’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Excellence in residency education

A middle-aged man was recently admitted to a Midwest hospital for “refractory congestive heart failure.” He had been followed in the hospital’s out-patient clinic for two years with that diagnosis. Yet, he continued to retain fluid and gain weight, despite optimal treatment for congestive heart failure. Finally, when his abdomen and scrotum had become so bloated that it was painful for him to put on his pajamas, he went to the emergency room at midnight, and from there he was admitted to the hospital. On the floor, his doctors made a startling discovery: he did not have heart disease, as presumed, but kidney disease. Clues to the kidney disease had in fact been present from the time the patient first started visiting the hospital’s clinic. With the correct diagnosis, the patient’s fluid retention was successfully addressed.

The above case illustrates a fundamental truth of medical practice: good doctors need to be able to think, not merely to follow protocols. Excellence in medical practice requires asking such questions as “what is the evidence to support a diagnosis or treatment plan?,” “what else could something be?,” and wondering “why?,” not just “what should we do?” Developing these skills is the purpose of residency education.

Although the public can be confident in the work of all accredited residency programs, it is also well known that some do a better job of producing skilled physicians than others. Success rates on the various specialty board examinations vary among programs, as does the frequency with which graduates of different programs subsequently achieve leadership positions in practice or in academic medicine.

Sailors examine patient during residency at Naval Medical Center San Diego. Official Navy Page from United States of America MCSN Joseph A. Boomhower/US Navy. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Sailors examine patient during residency at Naval Medical Center San Diego. Official Navy Page from United States of America MCSN Joseph A. Boomhower/US Navy. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.What accounts for these differences among residency programs? Certainly, it is not with anything that can be readily measured. All programs have adequate physical facilities, enough beds and teachers, good clinical laboratories and libraries, and sufficient formal lectures and teaching conferences. Had they not, they would not have been accredited by the relevant Residency Review Committees. The structural characteristics of residency programs do not provide the answer.

Rather, the differences in educational quality among residency programs result from differences in their learning environment. Facts and procedures can be taught in school-child fashion from lectures and demonstrations. This is not the case, however, for higher intellectual abilities such as clinical judgment, analytical rigor, creative capacity, or the ability to manage uncertainty. Clinical judgment cannot be learned from books. Rather, it involves informal learning from conversations, discussions, reflection, role modeling, and absorption of the values and attitudes of the faculty. The better these elements, the stronger the residency program.

The most important informal learning is that acquired from discussions about specific cases. Examples of such exchanges include conversations with attending physicians or consultants about complex patients in whom the treatment of one problem might exacerbate another, discussions with fellow house officers and faculty at lunch or dinner, conversations with the attending surgeon while scrubbing or during the course of an operation, informal discussions with a faculty member about the flaws in a recent paper or about his current research, or discussions at residents’ report about not just how to make the diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus but also about whether there was sufficient evidence to make the diagnosis and begin treatment in the patient admitted last night (and if not, what needed to be done to make the diagnosis or establish the presence of a lookalike condition). Studies of residency programs have also observed that discussions at strong programs regularly explore the underlying science, examine the rationale for current practices, foster critical thinking, and encourage exploration of the unknown. In contrast, teaching at weaker programs rarely engages in those activities, focusing instead on practical topics, particularly patient management of the more common problems.

In short, excellence in residency education is not a matter of formal curricula, lectures, or books, as valuable as these devices might be as educational supplements. Rather, excellence depends on the intangibles of the learning environment: the skill and dedication of the faculty, the ability and aspirations of the house officers, the opportunity to assume responsibility in care with a manageable number of patients, the freedom to pursue intellectual interests, and the presence of high standards and high expectations of the house staff. With these elements properly in place, excellence is assured, and residency education can continue to occupy a legitimate place in the university.

Heading image: RCSI Bahrain students taking a group photo following the 2013 White coat ceremony. By Mohamed CJ. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Excellence in residency education appeared first on OUPblog.

Behind-the-scenes at the UK Law Teacher of the Year Award

Professor Jane Holder of University College London has been named UK Law Teacher of the Year 2015. The prestigious national teaching award, which is sponsored by Oxford University Press, was presented at a lunch event held on Friday, 27 February 2015.

Jane Holder is a professor of environmental law at University College London (UCL) and impressed the judges with her innovative teaching and real-world impact to win the £3,000 prize money. All six finalists for the award were present at the awards event, along with the four members of the judging panel and last year’s winner Luke Mason. On being presented with the award, Holder thanked her mother and husband for their support, and went on to explain how being shortlisted for the award had made her think critically about teaching. “The Law Teacher of the Year award is so meaningful because you go through the process of really thinking about your teaching – both the good bits, and the bits that can be improved – and it offers a valuable opportunity to learn from the other nominees”.

The other finalists were:

Paula Blakemore, Birkenhead Sixth Form College

Ama Eyo, Bangor University

Emily Finch, University of Surrey

Esther McGuinness, Ulster University

Nick Taylor, University of Leeds

2015 Law Teacher of the Year Jane Holder

Finalist Ama Eyo (Bangor University) chats to judge Alison Bone

before the lunch event

Paula Blakemore of Birkenhead Sixth Form College with one of her former students

Nick Taylor (University of Leeds)

before the event

Ulster University’s Esther McGuinness

talks to event guests before the announcement

Emily Finch, University of Surrey,

in conversation during the drinks reception

The four-member judging panel ramp up the tension before the announcement

L-R: Alastair Hudson, Marianne Lightowler, Alison Bone, Andreas Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos

Outgoing Law Teacher of the Year, Luke Mason,

speaks about the impact a great teacher can have

Prize money for the winner of the 2015 Law Teacher of the Year Award

Judge Alison Bone talks about finalists Emily Finch and Paula Blakemore

Emily Finch hears comments from her students and colleagues

Feedback from students puts a smile on Paula Blakemore’s face

Jane Holder laughs at the description of her windswept campus visit

Andreas Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos

recounts visiting Jane Holder and Esther McGuinness during the judging process

Esther McGuinness

listens to Andreas Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos’ summary of her teaching session

Judge Alastair Hudson

describes his campus visits to Bangor and Leeds

Nick Taylor

listens to comments from students, colleagues, and the head of the School of Law at Leeds

Ama Eyo

with her guests Professor Dermot Cahill and Stephen Clear

All the 2015 finalists pose for a photo

Winner Jane Holder with the judging panel

The post Behind-the-scenes at the UK Law Teacher of the Year Award appeared first on OUPblog.

How to win the 2015 General Election

The political campaigns are heating up in the UK ahead of the 2015 General Election on May 7th. As each political party desperately tries to secure the votes needed to win the election, the following extract from British Politics: A Very Short Introduction by Tony Wright, describes the importance of the party system in British politics.

If you want to win votes and get elected in Britain, at least in general elections, then you had better get a party. The occasional and isolated exceptions only prove the rule. Before the 2010 general election, in the wake of the parliamentary expenses scandal, there was speculation that independent candidates might do unusually well, but in the event this did not happen. Elected politicians have a wonderful capacity for persuading themselves that their electoral success is to be explained by their obvious personal qualities, but the evidence is all against them. Overwhelmingly, it is the party label that counts. British politics is party politics. This is another of the big truths. Yet parties themselves are becoming weaker and the traditional party system is less secure. This is something to which it will be necessary to return.

Following the 1997 election, legislation was introduced (Registration of Political Parties Act 1998) to enable parties to register their title to their name, and to similar names that might confuse the voters. The significance of this legislation was not what it contained, which was relatively minor, but the fact that (p. 71) legislation on political parties had been introduced at all. This was a major constitutional departure. The role of political parties might be one of the big truths of British politics, but it was a truth that had hitherto not dared to speak its name. Apart from some small housekeeping provisions, the existence of political parties was a closely guarded constitutional secret. This was like describing a car without mentioning that it had an engine.

It was not until 1969 that party names were even allowed to appear on ballot papers, finally exploding the fiction that it was individuals rather than parties who were being voted for. In the House of Commons the fiction is still maintained by the absence of any party designation in the way that MPs are formally described. They are simply the ‘Honourable Member’ for a particular constituency. The real business is done through a mysterious device known as the ‘usual channels’, curiously absent from the textbooks, where the party managers carve things up between themselves away from the decorous party-blind formalities of the chamber. But party has now come in from the constitutional cold. The legislation on party registration has been followed by a raft of other measures—on party list electoral arrangements for devolved assemblies and for the European Parliament, and regulation of party funding backed by a new commission—that bring the parties and the party system into full view.

“So the secret is out. In Britain, party rules.”

So the secret is out. In Britain, party rules. There might be argument about the extent to which the state should interfere with how voluntary associations like parties order their internal affairs, but not with the centrality of party to the operation of the political system. Tony Blair became prime minister because in 1983, just three weeks before the general election, a few members of the Trimdon branch of the safe Labour constituency of Sedgefield persuaded the 83-strong general committee of the local party, by the wafer-thin margin of 42 to 41, to add the young (p. 72) barrister’s name to the shortlist from which it was selecting a parliamentary candidate. This is a vivid illustration of the way in which the parties act as the gatekeepers and recruiting agents of British political life. With no separation of powers, governments are formed from among the tiny pool of politicians who belong to the majority party in the House of Commons. Even coalition government only extends the pool slightly. These politicians are there not primarily because of the electorate but because of a prior election held by a small party ‘selectorate’, whose choice is then legitimized by the wider electorate.

In other words, the parties control the political process. While this is a feature of political life almost everywhere, in Britain the control exercised by the parties is exceptionally tight. Ever since Jonathan Swift satirized a Lilliputian world divided between High-Heelers and Low-Heelers (the issue at stake being the size of heels on shoes) and Big-Enders and Little-Enders (where the dispute is over which end of an egg should be broken first), the party question has been endlessly debated. Some saw party in terms of the evils of faction and sectionalism; others as (in Edmund Burke’s words) ‘a body of men united, for promoting by their joint endeavours the national interest, upon some particular principles in which they are all agreed’. The movement from loose associations of interests and persons to tightly organized electoral and parliamentary machines is the story of the development of the modern party system. It was a development that transformed political life. In the 1840s Sir James Graham, Peel’s Home Secretary, described ‘the state of Parties and of relative numbers’ as ‘the cardinal point’, for ‘with a majority in the House of Commons, everything is possible; without it, nothing can be done’.

Featured image credit: Polling station, Southwark, London. By secretlondon123. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post How to win the 2015 General Election appeared first on OUPblog.

March 5, 2015

The Oxford Comment – Episode 20 – Living with the Stars

Everything is connected. Animals and asteroids, bodies and stardust, heartbeats and supernovas—all of these arise from a common origin to form the expanse of the universe, the fiber of our being. So say our guests of this month’s Oxford Comment, Karel Shrijver, an astronomer who studies the magnetic fields of stars, and Iris Schrijver, a physician and pathologist, both of whom draw upon their expertise to uncover new dimensions of understanding.

We sat down for a captivating discussion with the co-authors of Living with the Stars: How the Human Body is Connected to the Life Cycles of the Earth, the Planets, and the Stars, delving into the history of the universe and the miraculous systems at work both within us and all around us.

Image Credit: “Star Trails” by Marjan Lazarevski. CC by ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The Oxford Comment – Episode 20 – Living with the Stars appeared first on OUPblog.

Country music and the press

At least a decade prior to the recording of the first “hillbilly” records in the 1920s, journalists were writing about rural music-making in the United States, often treating the music heard at barn dances, quilting bees, and other rural social events as curious markers of local color. Since the emergence of country music as a recorded popular music in the 1920s, though, the press’s fascination with the genre has not waned. Writers for mainstream national publications, music trade publications, and fan magazines alike have not only documented the genre’s rich history in the United States and abroad, but also captured prevailing attitudes about the genre. Surveying nearly a century of writings on country music, it becomes clear that the press’s interest in the genre has focused on three primary topics: (1) the lifestyles of leading country recording and broadcasting stars, (2) the business of country music, and (3) country music’s place in American culture.

Almost from the outset, the lifestyles of country singers fascinated radio listeners and record buyers. A 1938 essay by journalist Paul Hobson, for instance, presents a profile of songwriter and internationally-known artist Carson Robison, who prefers outdoor work on his ranch in Poughkeepsie, New York to life in the songwriters haven of Manhattan. Similarly, in a 1955 feature in Country & Western Jamboree, writer Murray Nash profiles honky tonk singer Kitty Wells, who is perhaps best known for her 1952 recording of the feminist anthem “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels.” Nash neutralizes her strong female character by describing her as “the best wife and mother in the business.” Rolling Stone contributor Vanessa Grigoriadis’s 2009 profile of Taylor Swift similarly works to break down the celebrity façade of the internationally recognized country-pop superstar by describing Swift’s “very pink, very perfect life.” Taken together, it becomes clear that journalists have played an essential role in establishing a country artist’s personal credibility in a genre that prides itself on its relevance to “common” people.

Just as journalists work diligently to cast country musicians as people just like you and me, they have also demonstrated a strong interest in the riches that could be gained from musical practices that were often described as unsophisticated. Just a few short years after the first hillbilly recordings were made, Talking Machine World, a publication that was read widely by audio enthusiasts and industry insiders alike, explored “what the popularity of hill-billy songs means in retail profit sensibilities,” suggesting that public “desire for something different… can be taken advantage of by both the popular publisher and record maker.” An oft-cited 1944 Saturday Evening Post essay by Maurice Zolotow similarly points to the profits garnered by a wartime “hillbilly boom” that witnessed some recordings selling more than a million copies. Many of these reporters seemed to be flabbergasted by country music’s widespread popularity and the profits that it generated, but one might just as easily read a sort of American rags-to-riches story into their descriptions of country music’s transition from a vernacular music to a commercial one.

Country music’s origins—or, at least, perceptions of those origins—play an equally important role in the ways that journalists discuss the genre’s place in American society. For some commentators, such as Musical America contributor Linton K. Starr, country music was the product of “untutored” rural people who spun yarns and lived simple lives of rural bliss (although one of the fiddlers profiled in the piece, Fiddlin’ John Carson, was a resident of metropolitan Atlanta at the time). For Washington Post contributor George F. Will, country music’s strong association with the white rural working-class would make the emergence of African American country singer Charley Pride in the late 1960s seem to be a noteworthy anomaly: “Your basic country music audience is white, and disproportionately rural and southern. You would not think of it as a promising audience for a black man.” When Kyle Ryan, writing about the millennial alternative country movement for Punk Planet in 2005, the rise of “hot country” music—as heard in the work of Garth Brooks, Shania Twain, and others in the 1990s—was a threat to country music’s authenticity, a threat that demanded an “alternative” form of music that was “more traditional than mainstream country music.”

Country music journalists have played a central role in shaping discourses around the genre. As documentarians, they have captured prevailing attitudes about country music aesthetics, politics, and economics, among other subjects. As editorialists, they have argued about country music’s place in contemporary society, as well as the place of its audiences in American culture. Journalistic essays serve as one valuable tool in helping us understand country music’s complex musical and social histories.

Headline Image: Musician with banjo. CC0 via Pixabay

The post Country music and the press appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers