Susan Higginbotham's Blog: History Refreshed by Susan HIgginbotham, page 12

July 30, 2013

Twelve Rules for Writing About the House of Lancaster: A Writer’s Guide

As I mentioned in my last post, I’ve been looking at the search terms that people use to reach my website and blog. It’s becoming alarmingly clear that while authors of Wars of the Roses books and screenplays are fairly adept at creating Yorkist characters (keywords: noble, strong, beautiful, loyal), some are still a little shaky on how to manage Lancastrian ones. So here, without further ado, are some tips that can work not only for fiction, but for some nonfiction as well:

As I mentioned in my last post, I’ve been looking at the search terms that people use to reach my website and blog. It’s becoming alarmingly clear that while authors of Wars of the Roses books and screenplays are fairly adept at creating Yorkist characters (keywords: noble, strong, beautiful, loyal), some are still a little shaky on how to manage Lancastrian ones. So here, without further ado, are some tips that can work not only for fiction, but for some nonfiction as well:

If a Lancastrian character is tolerably good-looking, he or she must spoil the effect by sneering a lot.

Ideally, all Lancastrian marriages should be consummated by rape, or something very near to it, but at the very least, the experience must be a miserable one for one or preferably both parties. Remember, there is no such thing as Good Lancastrian Sex, only Bad Lancastrian Sex. (Unless, of course, incest is involved. See below.)

If a Lancastrian mother loves her son, she must also harbor a subconscious (or not so subconscious) desire to sleep with him.

Young Yorkist men must work hard at mastering the knightly arts because they have lofty chivalric ideals and long to prove their courage. Young Lancastrian men must work hard at mastering the knightly arts because they are psychotics who want to kill and maim people.

Yorkists must have big friendly dogs that follow them around worshipfully. Lancastrians must snap the necks of little birdies just for the fun of it.

A devoutly religious Yorkist woman must be described as pious. A devoutly religious Lancastrian woman must be described as a fanatic.

If a Yorkist should change sides (God forbid), it must be only for the purest of motives and must occur after agonizing soul-searching. If a Lancastrian must change sides, it’s because he’s a sneaky little rat.

If something untoward happens to a Yorkist, the retaliation by his family must be treated as necessary to uphold the family honor and to exact justice. If something untoward happens to a Lancastrian, the retaliation by his family must be treated as an act of mindless vengeance by twisted people who just can’t let bygones be bygones.

Any gossip about the sexual proclivities of a Lancastrian woman should not only be treated as unvarnished truth, but should be embroidered upon generously.

Ideally, a Lancastrian baby should be illegitimate, but if not, he or she must be the product of Bad Lancastrian Sex.

A Yorkist who marries a much younger woman must be treated as acting in accordance with the mores of his time. A Lancastrian who marries a much younger woman must be treated as a pedophile.

Formidable Yorkist women must be portrayed as strong, courageous matriarchs. Formidable Lancastrian women must be portrayed as domineering harpies.

July 29, 2013

An Update, and Some Public Service Announcements

It’s been a while since I mentioned any news about my books, so I wanted to give you an update on what’s going on (and, alas, what’s not going on) with me.

First, the good news: my first nonfiction book, The Woodvilles, will be published in October in the UK and in January in the US. You can find a description of the book, plus an excerpt and ordering information, here. I’m setting up a tour of my favorite blogs as my publication date grows closer, so keep an eye on this space!

Second, I’m excited to note that my novel about Katherine Woodville and her husband, The Stolen Crown, will be coming out as an audiobook on August 12. John Lee and Alison Larkin are the narrators. I shall have to buy a copy to see what Harry and Kate sound like!

Now for the bad news. Some of you have been expecting my novel on Margaret Douglas, Countess of Lennox. This isn’t happening, at least as a full-length book. I am a novelist who has to love my main characters, and with Margaret, the older she got, the harder I found it to connect with her. I couldn’t connect with anyone around her either, which made matters even worse. After a rather embarrassingly long and very frustrating period, I finally had to throw up my hands and admit that this was a project that was not meant to be.

I do find the younger Margaret likable, and it may be possible to salvage a shorter work about her from what I’ve written so far. I’ll be looking over what I have and seeing if this is viable. If it is, I’ll probably make it available on Amazon; if it’s not, I won’t inflict it upon you, but will instead consign it to my computer’s version of an attic.

And now back to the good news! I’m back to writing about the character I should have been writing about all along, and the writing is going much better. My characters are chatting in my head, in contrast to the stony silence I got from Margaret and the gang, and I find myself thinking about them when I’m brushing my teeth and walking the dogs (not, fortunately, at the same time). Until I get a lot further along, I’m keeping mum on the details, though.

Finally, I’ll be doing a search terms post soon. Til then, as a public service announcement, here are short (and straight) answers to some questions that keep popping up in searches for my blog:

did Edward of Lancaster rape Anne Neville?

There’s not the slightest evidence he raped his wife, or anyone else.

did henry vii rape elizabeth of york?

There’s not the slightest evidence that he raped Elizabeth of York, or anyone else.

was margaret of anjou having sex with her son?

There’s not the slightest evidence that she . . . Well, you get the picture.

did henry the 8th king of england wear glasses?

Yes, he did. A number of pairs are listed in the inventory of his goods. (And before someone asks, there’s not the slightest bit of evidence that he raped any of his wives. Or his son. Or his daughters.)

July 26, 2013

Guest Post by Sarah: The Martyrdoms of Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley

My, this blog has been quiet lately! I’ve been busy with the page proofs for The Woodvilles (due out in October in the UK and January in the US), but now that things are quieter I hope to be blogging more.

Now that I’ve made my excuses, I’m pleased to be hosting a guest post by my friend Sarah about a very dark time in English history:

The Martyrdoms of Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley

On October 16th, 1555, Queen Mary I of England sent two protestant bishops, Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley, to the stake in Oxford. They had long been in service to the crown and supported the reforms in religion introduced under Henry VIII and his son, Edward VI, but unfortunately Mary I was determined to restore Catholicism. Restoring Catholicism was not easy; indeed, big change in any state is not easy, and these men were two of around 300 that lost their lives to the cause.

Hugh Latimer was born between 1485 and 1491 in Thurcaston, Leicestershire. He was an only son, but had six sisters, and was born into a farming family. Not a lot is known of his early years, though he was educated well enough to attend Christ’s College at Cambridge University at around the age of 14. In February 1510 he was awarded a fellowship to Clare College, became a Master of Arts in April 1514, and was ordained a priest of the Roman Catholic faith in July 1515. Hugh remained true to Catholicism and spoke out against religious reform in his early years as a priest. In 1524, his friend Thomas Bilney asked Hugh to hear his confession of the new faith and following the confession, Hugh himself became a reformer. He said of his conversion-

“To say the truth, by his confession I learned more than before in many years. So from that time forward I began to smell the Word of God, and forsook the school-doctors and such fooleries.”

Hugh began to preach his new faith openly, causing upset within the Catholic church in England. The Bishop of Ely banned him from preaching in his diocese and accused him openly of heresy. Hugh was brought before Cardinal Wolsey, who decided Hugh was not a heretic and restored his licence to preach. Hugh became good friends with Thomas Cranmer, who would later become Archbishop of Canterbury. Both Hugh and Thomas were supporters of King Henry VIII’s divorce from Catherine of Aragon and marriage to Anne Boleyn. Through this support, Hugh gained royal favour and was richly rewarded, becoming the Bishop of Worcester in 1535.

Hugh, along with other reformers, had many enemies of the Catholic faith at court, though he was protected by his friendships with King Henry and Thomas Cranmer. However, King Henry was to grow uncomfortable with extreme reformation and passed the Act of Six Articles in 1539. This Act supported traditional Catholic doctrine, including confirmation of transubstantiation and clerical celibacy. Hugh refused to sign the Act and resigned his bishopric, remaining in disgrace until Henry VIII died in 1547.

Nicholas Ridley was born in the early 1500s, the second son of Christopher Ridley. Nicholas received a good education; he was literate, learnt Greek and was taught theology, studying at Pembroke college, Cambridge in 1518 and gaining a masters degree in 1526. After he completed his study in England, Nicholas went to France to further his education, studying at the Universities of Louvain and Paris, and became an ordained priest. In 1529, he was appointed junior treasurer of the college at Cambridge, then became a chaplain.

Nicholas signed the royal decree in 1534, denouncing the Pope’s supremacy over the church. He firmly believed that the Bishop of Rome had no more authority in England than any other foreign bishop and was supportive of his king and the royal supremacy; something that would have kept him high in favour and earned him the king’s trust.

In 1537, Nicholas’ career in the church advanced further when he was appointed a chaplain to Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, and the following year he became Bishop of Herne. Nicholas was also uncomfortable with the Act of the Six Articles, though he was in no danger as he was unmarried and still believed in the transubstantiation. Nicholas’ church career progressed further over the next few years, as he was appointed Canon of Canterbury and became one of King Henry VIII’s chaplains. He accused of heresy in 1543, but was soon cleared of the charges.

King Henry’s son, Edward VI, became King of England upon the death of Henry VIII in January 1547. Edward was only nine, but was clever for his age and a staunch protestant, and the reformation of religion in England during his reign took off very quickly. The Act of the Six Articles was repealed and Hugh began to preach once again. In 1549, men from Devon and Cornwall rose up against the reforms in the ‘Prayer Book Rebellions’; these rebellions were quickly crushed by Edward’s council and reform continued. Hugh remained an active preacher and campaigner throughout Edward’s reign. He was a friend of Edward Seymour, Edward VI’s uncle and Lord Protector, and was present at the execution of Thomas Seymour.

Mary I, painted aged 28

Edward made Nicholas Bishop of Rochester. Nicholas removed altars in his church, replacing them with plain tables, he established reformed, protestant teachings and abandoned his belief in transubstantiation. He also helped Thomas Cranmer write the Common Book of Prayer. He examined the beliefs of Edmund Bonner and Stephen Gardiner; they were removed from their offices in the church and imprisoned in the Tower of London for their Catholic beliefs. Nicholas took over Edmund’s diocese as the Bishop of London in 1550.

Edward VI became ill in the spring of 1553. His condition rapidly worsened and he made his will in June. His main concern was the succession; Edward’s heir was his fiercely Catholic half sister Mary, who was likely to undo all of the reforms he had worked hard to achieve. Edward changed the Act of Succession of his father, declaring Mary and his other half sister, Elizabeth, illegitimate and unfit to rule; in their place, he named his cousin, Lady Jane Grey, as his heir. Nicholas signed the letters patent of Edward’s decision before the boy king died on July 6th that year.

On July 9th, Nicholas preached a sermon at St Paul’s Cross in London. He told the people listening of King Edward’s death and the contents of the Third Act of Succession. He said Mary and Elizabeth were bastards, unfit to rule the country and proclaimed Lady Jane Grey as Queen of England. Jane entered London the next day, though she did not remain queen for very long as Mary raised an army and claimed her throne, winning it back on June 19th. Jane Grey was imprisoned in the Tower of London, and would later be executed. Nicholas went to beg Queen Mary’s pardon for his proclaimation, where he was quickly arrested and sent to the Tower.

In September 1553 other leading reformers, Hugh included, were arrested and also imprisoned in the Tower of London. Both Hugh and Nicholas were moved to Oxford to be examined by Mary’s council, which included the now free Stephen Gardiner, and were found guilty of heresy in April 1554. They were offered a chance to recant their heresies and save their lives- they refused, and as a result were sentenced to be burnt alive.

The burning of Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley, as shown in Actes & Monuments

The men were to die on October 16th, 1555, sharing a stake in Oxford. Hugh died very quickly, with the words:

“Be of good comfort, Master Ridley, and play the man, we shall this day light such a candle by God’s Grace in England, as (I trust) shall never be put out.”

Nicholas was not so lucky. Death did not come quickly to him, as the wood was piled too high around him. Only the bottom of his body burnt, leaving his top half and the gunpowder around his neck untouched. Nicholas cried out for some of the faggots around him to be removed, with the desperate words, “I cannot burn!”. Eventually the wood around him was removed and the lower faggots caught fire properly, the flames lit his gunpowder and his suffering was over.

-

Select further reading:

John Foxe, Actes and Monuments, Oxford University Press, 2009 print edition

Anna Whitelock, Mary Tudor: England’s First Queen, Bloomsbury books, 2010

H.F.M. Prescott, Mary Tudor: The Spanish Tudor, Phoenix books, 2003 [1940]

Linda Porter, Mary Tudor: The First Queen, Piatkus, 2009

Peter Wallace, The Long European Reformation, Palgrave Macmillan, second edition, 2012

John Schofield, Cromwell to Cromwell: Reformation to Civil War, The History Press, 2011

-

Sarah is currently studying for a Bachelor of History with Latin degree at an English university and regularly blogs at her site Henry III (link: henrythethirdofengland.wordpress.com )

June 26, 2013

Thomas Tuddenham’s Torrid Tale

A little while back, I did a guest post about Alice de la Pole, Duchess of Suffolk, for Sarah’s History Blog. One of Alice’s madcap adventures in the late 1440′s involved going in disguise to Lakenham Wood in the company of several other people, including Thomas Tuddenham, a prominent (and unpopular) supporter of William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk. At this time, Tuddenham was an unmarried man–but his marital history, as examined by Roger Virgoe in his article, “The Divorce of Sir Thomas Tuddenham,” was an unusual one.

According to Virgoe’s article (from which all that follows is taken), Thomas married Alice Wodehouse, the daughter of his guardian John Wodehouse, in about 1418, when Thomas was about seventeen. For several years, the couple lived together. Alice bore a son–but unfortunately, as Alice freely admitted, the father was not Thomas but Richard Stapleton, John Wodehouse’s chamberlain. The boy died soon thereafter. Alice and Thomas formally separated, and sometime before 1429, Alice entered a Augustine nunnery in Norfolk with the unprepossessing name of Crabhouse. John Wodehouse died in 1431.

There matters rested until 1436, when William Alnwick, Bishop of Norwich, began proceedings in the ecclesiastical courts to inquire into the couple’s marriage. As Virgoe points out, the proceedings , though formally instituted by the bishop, were probably initiated by Tuddenham himself, perhaps because he wanted to remarry.

Soon a parade of witnesses came before the commissioners appointed by the bishop to investigate the matter. Alice herself, clad demurely in her nun’s habit, appeared first, accompanied by Joan Wygenhale, the prioress of Crabhouse, and Joan Kervyle, a fellow nun there. Alice told the commissioners that Thomas had treated her with “conjugal affection” for eight years, except in one important respect: “for carnal knowledge which he never had of her during those eight years nor before nor after, and thus they were never one flesh.” She admitted that during her marriage to Thomas, she had given birth to the son of Richard Stapleton. Alice was then asked whether she had taken the nun’s habit, to which Alice replied that her present appearance indicated that she had.

Joan the prioress, age 52, then testified that Alice had often said, before and after taking the veil, that Thomas had never had carnal knowledge of her. The prioress added, however, that Alice’s father had told his daughter, through intermediaries, that she should not say this. Nonetheless, Alice persisted in saying on several occasions that there had been no consummation, which begs the question of what the nuns of Crabhouse were talking of when they should have been praying.

Asked whether the bishop had known of Alice taking the veil, Joan Wygenhale (who, incidentally, was notable during her tenure as prioress for the building projects she undertook) said that she did not know. She added, though, that Alice had shown her “a certain notarial instrument in which was contained the summary of the divorce made between her and Thomas.”

Among the other witnesses appearing before the commissioners was Beatrice, the wife of Thomas Fulthorp, who testified that Thomas and Alice had cohabited in her house for over two years and that they had treated one another with conjugal affection. She testified that she had seen them “many times together lying on one bed; but she could not say whether there was carnal knowledge between them.” Asked whether she had heard either spouse say that carnal knowledge had not taken place, Beatrice replied that she “never heard Alice say so except when Tuddenham and Alice were in discord, which happened often during the two years.”

Beatrice also informed the commissioners that she had witnessed the birth of Alice’s son and that her then husband, John Shuldham, and John Wodehouse’s wife Alice had served as the boy’s godparents.

Thomas himself testified that he and Alice had treated each other as husband and wife “save for sexual intercourse which he never had with her during those years, nor before nor after.” Asked whether he wished to live in perpetual chastity, he “solemnly declared that he did not,” but wished to be able to remarry. On December 7, 1437, he was declared free to do so.

In spite of this, Thomas never did remarry. Perhaps his marital history made him an undesirable partner, or perhaps the proceedings had dampened his enthusiasm for reentering the marital lists. He nonetheless remained a powerful, though controversial, figure. In 1458, he was made the treasurer of Henry VI’s household.

Thomas’s luck ran out, however, in 1462, when the new king, Edward IV, ordered the arrests of various men, including John de Vere, Earl of Oxford, Aubrey de Vere (Oxford’s heir), and Thomas Tuddenham. Accused of plotting with the exiled Lancastrians, the men were given a summary trial in the constable’s court before the holder of that office, John Tiptoft, Earl of Worcester, and were beheaded at Tower Hill on charges of high treason. Tuddenham’s turn on the scaffold took place on February 23, 1462. His body was buried at the Austins Friars in London; his head probably was set on London Bridge.

Alice, meanwhile, remained at Crabhouse. She was still there in 1475, when Tuddenham’s sister Margaret Bedingfeld, who had inherited her brother’s estates, left her ten marks.

Sources:

British History Online, House of Austin Nuns: The Priory of Crabhouse.

Cora Scofield, The LIfe and Reign of Edward the Fourth.

Roger Virgoe, “The Divorce of Sir Thomas Tuddenham,” Norfolk Archaelology, 1969 (collected in Caroline Barron et al., eds., East Anglian Society and the Political Community of Late Medieval England: Selected Papers of Roger Virgoe.

June 13, 2013

The Ten Warning Signs You Might Be a Bride of Gloucester

As most regular readers of this blog have gathered, I’m not a great admirer of Richard III, though I find the man and his times fascinating and am very grateful for the work of the Richard III Society in making more information about both available. And while I’m not keen on the man himself, I do have a number of Ricardian friends, with whom I have passed many entertaining and enlightening moments online (and sometimes offline as well).

There is, however, a very small subset of Ricardians whose feelings for Richard III go far beyond the bounds of mere admiration or interest. For this minority, someone (not me, sadly) has coined the brilliant phrase, the “Brides of Gloucester.” For these folks, nothing but abject, slavish devotion to the king will do, and woe betide anyone who might hold a different opinion.

Now, having read this far, you might be sitting up straighter and worrying, “Could I, with my boar badge and my penchant for white roses, be a Bride of Gloucester?” In order to ease your mind (or not, as the case may be), I therefore am providing you with a public service. If you can answer three or more of these questions with “yes,” you may want to find a new interest, such as learning to become a tattoo artist. (No, a portrait of Richard III would NOT look good tattooed on your back. Don’t even think about it. At least have the decency to settle for a simple white rose.) If you can’t–you’re in the clear. Heck, you might even come to have a sneaking admiration for Margaret Beaufort.

Richard III’s portrait hangs in a more prominent position in your house than that of your partner or children.

When you refer to “Dickon,” all of your friends know whom you’re talking about.

You feel a certain antipathy toward Anne Neville, but can’t quite figure out why.

When someone refers to a holy day, you assume he means October 2.

When you think of an evil man, the image that comes to mind is not Adolf Hitler, but William Shakespeare.

Your dog is named Lovell.

You call in sick on August 22.

You fantasize about seeing your loved one with one shoulder higher than the other.

You have lost at least one friend over whether Richard should be buried in Leicester or York.

You cry out “Richard” when you climax, and your partner doesn’t even notice anymore.

May 29, 2013

Two Woodville Family Markers

When I got on my blog last night to approve a comment, I realized that I haven’t posted here in over a month! So I thought I would make amends with a quick post about two grave markers of Woodville family members.

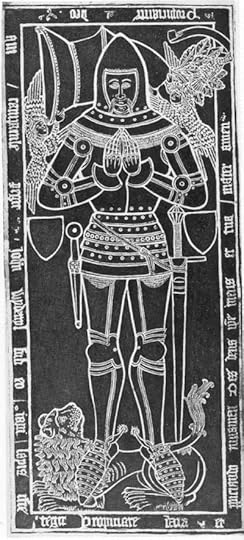

The first marker, an incised slab, can be found at the Church of St. Mary the Virgin at Grafton Regis. It depicts John Woodville, who died in the early 1400′s. Through his son Richard, he was Elizabeth Woodville’s great-grandfather. An inscription credits him with building the church’s bell tower (shown below the marker).

Copyright © 2002 Monumental Brass Society (MBS)

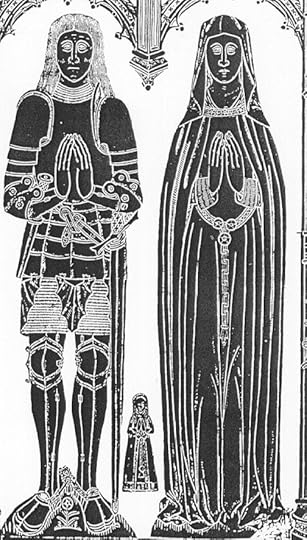

The second marker, a brass found at St. John the Baptist Church in Hillingdon, depicts Jacquetta, Lady Strange, a younger sister of Elizabeth Woodville, and her husband, John. Unlike those of her other sisters, Jacquetta’s marriage did not take place in the wake of Elizabeth’s match to Edward IV in 1464. Instead, Jacquetta married John Strange, Lord Strange of Knokyn, by March 27, 1450. Their daughter Joan (the small figure depicted on the brass) married George, the heir of Thomas Stanley. George is best known for having been taken hostage by Richard III to guarantee the loyalty of the Stanleys at Bosworth, a gambit which failed.

Copyright © 2002 Monumental Brass Society (MBS)

The photographs of both brasses are from the picture library of the Monumental Brass Society.

April 17, 2013

Katherine Plantagenet, Richard III’s Illegitimate Daughter

I was surprised to see that although Wikipedia has an entry on John, Richard III’s illegitimate son, there was no entry for his illegitimate daughter, Katherine Plantagenet. This may be because while little is known about John, even less is known about Katherine.

To start with, we do not know when John or Katherine were born or the identity of their mothers. It is often confidently asserted by admirers of Richard III that the children were born before his marriage, and while it seems likelier than not that Katherine at least was the product of his bachelor days, it is impossible to say this with certainty. We do not even know whether the children had the same mother.

Historian Rosemary Horrox, however, has identified a possible candidate as Katherine’s mother: Katherine Haute, who received an annuity of five pounds from Richard’s estates in East Anglia. Horrox suggests that Katherine was the wife of James Haute, a kinsman of Elizabeth Woodville. Had young Richard, Duke of Gloucester, wishing to make honorable provision for a former mistress, sought the queen’s help in arranging a suitable match for her? If so—and this is, of course, no more than speculation—it is yet another factor undermining the claim that the relationship between Richard and the queen was hostile before 1483.

Nothing is known about Katherine Plantagenet’s early years, or where she spent them. She is not named in the records of Richard’s coronation as one of the ladies receiving robes for the occasion. Richard’s seizure of the throne in 1483, however, wrought a vast change in Katherine’s own fortunes: the following year, she married an earl.

William Herbert, Earl of Huntington, born in 1455, was the heir of William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, who had been captured at the battle of Edgecote and executed on the orders of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, in 1469. Whereas Pembroke had been a powerful and valued supporter of Edward IV, gaining his earldom (and Warwick’s enmity) as a result, the younger William Herbert had enjoyed little royal favor once he reached his majority. D. H. Thomas has suggested that William was inept or, more kindly, that William was dogged by ill health. Indeed, as early as 1483, when he was only about twenty-eight, he made his will.

Herbert had no reason to regret the passing of Edward IV. Although his first wife, Mary, had been a younger sister of Elizabeth Woodville, she had died several years before, so any benefit from the connection had died with her. Indeed, for the benefit of Edward IV’s heir, Prince Edward, Herbert had been forced in 1479 to exchange his earldom of Pembroke for the less valuable earldom of Huntingdon. From the start, then, he was a natural ally of Richard III, whose coronation he attended, bearing Queen Anne’s scepter. He may have served as chamberlain to Richard’s only legitimate son, Edward.

On February 29, 1484, Richard III and William Herbert entered into an indenture arranging the marriage of William to Katherine Plantagenet. The indenture, transcribed by D. H. Thomas, reads,

This indenture made at London the last day of February in the first year of the reign of our sovereign lord King Richard the Third, between our said sovereign lord King Richard the Third on the one party, and the right noble lord William, earl of Huntingdon, on the other party, witnesseth that the said earl promiseth and granteth to and with our said sovereign lord the king that, before the feast of St. Michael next coming [September 29, 1484], by God’s grace he shall take to wife Dame Katherine Plantagenet, daughter to our said sovereign lord; and before their marriage to make or cause to be made to her behalf a sure, sufficient, and lawful estate of certain manors, lordships, lands and tenements in England to the yearly value of two hundred pounds over all charges, to have and to hold to him and to the said Dame Katherine and the heirs of their two bodies lawfully begotten in manner and form following: [that] is to wit, remainder to the right heirs of the said earl’s. For the which our said sovereign lord the king granteth to the said earl and to the said Dame Katherine to make or cause to be made before the said day of marriage a sure, sufficient, and lawful estate of manors, lordship, lands, and tenements over all reprise, to have to them and to their heirs males of their two bodies lawfully begotten; that is to wit, lordships, manors, lands, and tenements in possession at that day to the yearly value of six hundred marks, and manors, lordships, lands, and tenements in reversion after the death of Thomas Stanley, knight, Lord Stanley, to the yearly value of four hundred marks. And in the mean our said sovereign lord granteth to the said earl and Dame Katherine an annuity of four hundred marks yearly to be had and perceived to them from Michaelmas last, during the life of the said Lord Stanley, of the revenues of the lordships of Newport, Brecknock, and Hay in Wales by the hands of the receivers of them for the time being. And over this our said sovereign lord granteth to make and bear the cost of the said marriage at the day of the solemnization thereof. In witness whereof our said sovereign lord to that one part of these indentures remaining with the said earl hath set his signet, and to that other part remaining with our said sovereign lord the said earl hath set his seal the day and year abovesaid.

Richard III duly granted William and Katherine (still referred to as “Dame Katherine Plantagenet”) the annuity of 400 marks from the lordships of Newport, Brecknok, and Hay on March 8, 1484. The next grant, in May 1484, speaks of Katherine as William’s wife. Another grant followed on March 8, 1485.

These bare financial records are all that we know of Katherine’s life during her father’s brief reign. Whether she was old enough to consummate her marriage, whether she was happy in it, and whether she was close to her father are matters that can be only guessed at. Probably she would have spent much of her married life at Raglan Castle, the Herbert family seat in Monmouthshire.

In 1485, William Herbert played no part in impeding Henry Tudor’s march through Wales, nor is he recorded as having fought for his father-in-law at Bosworth. It may be, as D. H. Thomas suggests, that he simply had no military capacity; alternatively, Thomas suggests, Herbert might have been reluctant to move against Henry, who as his father’s ward had spent some time in the Herbert household as a youth. There was also the possibility that Henry would have married William’s sister if he had been unable to marry his first choice of bride, Elizabeth of York. If William did nothing to hinder Henry Tudor, he seems to have done nothing to help him either, for William himself did not receive a pardon until September 22, 1486.

Until recently, the Wikipedia article on Richard III claimed that following the battle of Stoke in June 1487, Katherine was “almost certainly arrested at Raglan Castle.” The Wikipedia editor gave no supporting evidence for this assertion, nor have I found any. Indeed, there is no evidence that either the earl or the countess was involved in the rebellion or that they were out of favor with the king at this point.

William Herbert attended Queen Elizabeth’s coronation in November 1487. The herald who recorded the event noted that “at that time the substance of all the earls of the realm were widowers or bachelors,” and named William, Earl of Huntingdon, as one of the widowers. When Katherine had slipped out of the world is unknown, as is so much else about her. It has been speculated that she died in childbirth, but if she did bear her husband any children, none survived the earl, who himself died in the summer of 1490 “in ye flower of his age.”

ETA: Erika Millen on Facebook pointed out that Horrox suggests in her Oxford Dictionary of English Biography entry on Richard that rather than Katherine dying, Herbert might have repudiated his marriage after Henry VII came to power. In that case, the “widower” would refer to Huntington’s first marriage, to Mary Woodville.

Sources:

Calendar of Patent Rolls

Emma Cavell, ed., The Heralds’ Memoir 1486-1490.

Peter Hammond, “The Illegitimate Children of Richard III,” in J. Petre, ed., Richard III: Crown and People.

Michael Hicks, Anne Neville.

Rosemary Horrox, Richard III: A Study in Service

Rosemary Horrox and P. W. Hammond, eds., British Library Harleian Manuscript 433.

D. H. Thomas, “The Herberts of Raglan as Supporters of the House of York,” Ph.D. dissertation, 1967.

March 31, 2013

More Richard III News: Missing Feet Spark Investigation

I thought that some of you might be interested in the latest salvo in the “Richard III Reburial Wars” that I saw earlier today in the British press:

Missing Feet Spark Investigation

Following the recent petition for judicial review of the decision to bury the remains of Richard III in Leicester, the Richard III Coalition, a new organisation of the Plantagenet king’s admirers and collateral descendants, has called for an investigation of the loss of the king’s feet.

When the skeletal remains were recovered underneath a car park at Leicester last year, they were intact except for the feet. Although the archaeological team involved with the dig believes that the feet were destroyed when a Victorian outhouse was built on the site of the church in which the king was originally buried, the Coalition is skeptical. ‘Richard III has been subject to numerous indignities over the years, and we believe that the loss of his feet should not be taken lightly,’ explained Coalition spokesperson Francis Hawkins. ‘We think this is something that demands further investigation.’

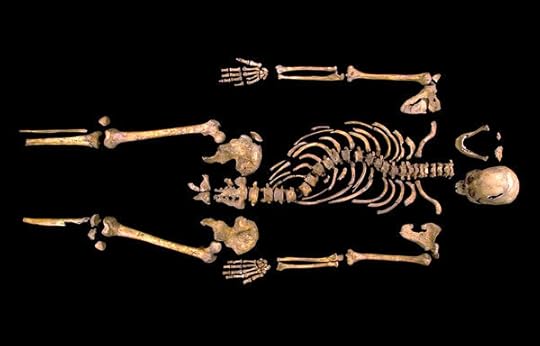

No feet under: The king’s skeletal remains.

Asked why he doubted the official explanation for the missing feet, Hawkins said, ‘This blaming the Victorians seems a bit too convenient, to be frank. I believe there are two likely explanations for the disappearance. The first is that the feet were hacked off immediately after the battle of Bosworth, probably on the orders of Edward Woodville to give to his mother, Elizabeth. We know that Elizabeth was an ardent practitioner of witchcraft, and it’s likely she used the feet in some sort of satanic ritual. We need someone learned in the practices of medieval witchcraft to tell us exactly what the feet might have been used for, and once we have that knowledge, and begin digging deeper into the records, I think everything will lock into place. It won’t be easy to find confirmation—we know that the Tudor usurper destroyed hundreds of thousands of records—but if we know what we’re looking for, we’ll at least have a head start.’

Elizabeth Woodville. Did she use the king’s feet for dark purposes?

The second possibility, Hawkins said, is that the feet were destroyed when the skeletal remains were removed from their centuries-old resting place. ‘This is an ugly possibility, but it needs to be looked into,’ Hawkins said. ‘Was it negligence, or was it perhaps a souvenir hunter or a thief? Richard’s feet may be standing on someone’s desk. I think somebody needs to be monitoring eBay and other auction sites as well.’

Hawkins bristled when asked whether he was accusing the archaeological team of wrongdoing. ‘As an admirer of Richard III, the king who invented bail, the right to jury trial, and the presumption of innocence, I would never soil anyone’s good name without cause,’ he said. ‘That’s for Tudor propagandists. But I don’t think we should blindly trust the team either. Richard trusted the Stanleys, and look where that got him.’

Rita Davis, a Coalition member who describes herself as Richard’s seventeenth great-niece, added, ‘As the relations of King Richard, who are proud to call him “Uncle”, we just want answers, which was what he would have wanted. We do know that Richard’s feet were important to him. His wardrobe accounts show that he spent a lot of money on shoes, for him and for Anne and poor little Ned as well. I think he would be very distressed if he were reburied with no effort to solve the mystery of his feet. I would certainly be upset if my feet were lost.’

The man wearing the short doublet and green hat in this illustration may be Richard III, exhibiting his taste for fine footwear.

Knowing that the mystery may never be solved, the Coalition in the meantime has commissioned a reconstruction of the king’s feet, which it hopes to unveil in the summer. ‘While it’s difficult to tell a man by his feet, you can tell a lot about a man’s feet by the man,’ said Hawkins. ‘Richard’s feet, as reconstructed, will reflect the essence of the man. Richard was a proven soldier, not a dilettante like Anthony Woodville or a coward like Henry Tudor. His feet would have been rough and callused. This is not a king who had pedicures.’

Preliminary work for a reconstruction of Richard III’s feet is underway

The Coalition will be raising funds and public awareness about its cause in the weeks to come. Said Gail Markham, the Coalition’s director of social media, ‘I’ve poured my heart and soul into this cause, because ever since I read The Daughter of Time last year, I’ve dreamed of standing face to face with Richard. When I realized he wouldn’t have any feet to stand on, I was devastated. It was almost as if they murdered Dickon all over again.’

The Coalition plans to launch its campaign tomorrow with hourly tweets from its Twitter account, www.twitter.com/the-king’s-feet.

March 30, 2013

Guest Post on Alice de la Pole, Duchess of Suffolk

Stopping by to let you know that I have a guest post today about Alice de la Pole, Duchess of Suffolk, on Sarah’s History Blog. Alice was fascinating to research–I hadn’t realized that she was actually put to trial before Parliament–and I hope you’ll find the post interesting! You’ll find many other great posts on Sarah’s blog as well.

March 15, 2013

Jacquetta, Duchess of Bedford by Mark Satchwill

I’ve been putting together illustrations for my book on the Woodvilles. Although most of the illustrations will be from contemporary or near-contemporary sources, no contemporary likeness of the grande dame of the family, Jacquetta, Duchess of Bedford, exists. The chronicler Enguerrand de Monstrelet described her as lively (frisque), beautiful, and gracious, but otherwise there’s no guidance as to what she looked like.

With that in mind, I thought it would be neat to have a modern artist, Mark Satchwill, supply me with his own imagined portrait of Jacquetta. The only guidance I gave was that there should be some family resemblance to Elizabeth Woodville and that the drawing should portray Jacquetta as a young woman–about the time she secretly married Richard Woodville. You can see the finished product a little closer to my publication date in October, but here in the meantime is a pencil sketch:

Mark previously did a drawing of Margaret of Anjou for me, and much as I loved it, I think I love the one of Jacquetta even better! You can see some of Mark’s other work on his Facebook page, on his blog, and on his website.