Susan Higginbotham's Blog: History Refreshed by Susan HIgginbotham, page 14

December 31, 2012

Happy New Year!

Happy New Year, everyone! If you had a bad 2012, I hope 2013 is much better, and if you had a good 2012, I hope 2013 outdoes it!

As you probably know, in medieval and Tudor England, the gift-giving day was not Christmas Day but January 1. The Ryalle Book, a manual for royal practices which David Starkey dates partially to Edward IV’s reign, spells out how the king and queen were to receive their presents:

On New Year’s Day in the morning, the King, when he cometh to his foot-sheet, an usher of the chamber to be ready at the chamber door; and say: ”Sire, here is a year’s gift coming from the Queen.” And then he shall say: ”Let it come in, Sire.” And then the usher shall let in the messenger with the gift, and then after that the greatest estates’ servant as is come, each after other as they be estates ; and after that done, all other lords and ladies after the estates that they be of. And all this while the King must sit at his foot-sheet. This done, the chamberlain shall send for the treasurer of the chamber, and charge the treasurer to give the messenger that bringeth the queen’s gift, and he be a knight, the sum of ten marks, and he be a squire, eight marks, or at the least 100 shillings, and the king’s mother 100 shillings, and those that come from the king’s brethern and sisters, each of them six marks, and to every duke and duchess, each of them five marks, and every earl and countess 40 shillings. This being the rewards of them that bringeth the year’s gifts. For I report me unto the king’s highness, whether he will do more or less: for this I know hath been done. And this done, the King to to make him ready, and go to his service in what array that him liketh.

The queen was likewise to sit at her foot-sheet, with her chamberlain and ushers performing the same tasks as the king’s. As her gifts would not be expected to be “all things so good as the King’s,” the rewards she would give to bearers would likewise be less generous.

As the excerpt above indicates, The Ryalle Book sometimes veers into the first person, where the author recalls the practice of an earlier court—apparently, as Starkey notes, that of Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou. That couple, the author of The Ryalle Book writes, arose earlier than was their usual custom on New Year’s Day and lay in bed to receive their gifts, remaining in bed “as long as it pleased them” to accept their presents. As Starkey writes, “We think of Henry VI and Queen Margaret as Shakespeare’s tragic couple; here we see them (still in their thirties) behaving like excited children on Christmas morning, up early and inspecting their presents in bed.”

Sources:

E. Grose, The Antiquarian Repertory, vol. I (1807).

David Starkey, “Henry VI’s Old Blue Gown: the English Court under the Lancastrians and Yorkists,” The Court Historian (1999).

December 24, 2012

A Christmas Newsletter from Jane Seymour

Merry Christmas, and a Happy New Year! Owing to my deadlines for my books, I will probably be blogging very sporadically, if at all, until I have met them. I did, however, want to leave you with a little tidbit, plus an exciting discovery.

In 1536, Henry VIII and his queen, Jane Seymour, spent Christmas at Greenwich, but could not travel there by barge as they usually did, so the court instead rode through the city of London to its destination. “The cause of the kings rydinge through London was because the Tames was so frosynne that there might no boots [boats] goe there on for yse [ice].”

Yet despite the cold, Jane, who had long been in the custom of writing an annual Christmas newsletter, continued to produce it once she was queen. I have transcribed the newsletter, long buried in the National Archives of the United Kingdom, just for my blog readers:

My dearest friends,

Well, what a year! Who would have guessed last December at Wolf Hall that I would be writing this year’s newsletter as a married woman? (I hope it’s not too catty to remember that a certain person said that I would never marry well. I think I married well enough, don’t you?)

Marriage was a big adjustment for both of us (well, maybe not so much for Harry), but I’m happy to report that both of us are settling in now. Oh, we have our moments (Harry is a bit touchy about some subjects, I’ve learned, especially about things up North and about a certain person), but don’t all married people?

Ned and Tom are doing well also. Ned and his wife Nan really like Ned’s new title (just between us, I think Nan likes it even more than Ned does). Now that I’m married, I like to tell Tom that he should settle down one of these days and get a wife of his own. He says he’s still looking!

One thing I do wish I could report is that I was expecting, but I haven’t seen any signs of that yet. Tom says, “Just keep on trying, sis, and have fun!” He’s such a scamp, that Tom, and I do admit that trying is pretty fun. In the meantime, I have my redecorating to keep me busy. Some people say that a certain person had good taste in her décor, but I don’t see that at all—if you want everything to look French, why not just go to France?

As for my stepdaughters, Nan warned me that things could be a little rough in a blended family, but really, I think things are going marvelously. Mary and I get on just like a house afire, and although little Elizabeth had a bit of an attitude at first, you can hardly blame the poor child, can you? Tom is very kind to her, and says that she is going to be a very pretty girl when she gets older. Of course, anything is bound to be an improvement over a certain person—but I really shouldn’t have such thoughts over Christmas, should I? Anyway, I’m sure Harry will find the girls good husbands sooner or later. I know Mary is a little impatient—but as I told her just the other day, I had to wait a bit, and look how well things worked out in the end!

My best wishes for you this Christmastide,

Jane

Like Jane, I hope that the holidays are wonderful for all of you, and that 2013 will be a time of happiness for you.

December 18, 2012

The Next Big Things: Woodvilles and Stuarts

As you might have noticed, there is a blog meme going about called “The Next Big Thing,” where authors answer questions about their works in progress and tag other authors to do the same. I was tagged by the wonderful Brian Wainwright, whose novels Within the Fetterlock and The Adventures of Alianore Audley I thoroughly enjoyed. I especially enjoyed the former because of the Despenser connection!

Anyway, here are the questions and my answers:

What is the working title of your next book?

I have two in progress: The Woodvilles (nonfiction) and The Lennox Jewel (historical fiction about Margaret Douglas, Countess of Lennox, grandmother of the Stuart dynasty).

Where did the idea come from for the books?

With regard to The Lennox Jewel, I was casting about for a proposal and realized that not much had been written about Margaret–she’s the subject of an older novel called The Green Salamander, but otherwise she’s been largely neglected in favor of her daughter-in-law, Mary, Queen of Scots.

As for The Woodvilles, my third and fourth novels are set during the Wars of the Roses, and in researching them I realized that there was a real need for a well-researched nonfiction book about this family. There have been biographies of Elizabeth Woodville and a biography of Edward Woodville, and a number of articles on various aspects of the family in scholarly journals, but no commercially published book about the family as a whole. I kept hoping that someone would write one, and one day, I thought, well, why not me?

What actors would you choose to play the part of your characters in a movie rendition?

I’m terrible at questions like this; I simply don’t go to the movies that often, and I tend to hear my characters rather than see them anyway. But the male actors better be HOT.

What is the one sentence synopsis of your book?

One sentence? Cruel and unusual punishment! For The Lennox Jewel:

Sent to the court of her uncle, Henry VIII, to escape the political turmoil of Scotland, Margaret Douglas is enveloped in Anne Boleyn’s glamorous circle, where she finds her first love—and learns at a terrible cost the dangers of being too near to the throne. But when Henry’s daughter Elizabeth comes to power, Margaret seizes the chance to chart not only her own destiny, but that of a new dynasty.

The Woodvilles: The upstart family whose marriages brought them to the throne of England–at a terrible price.

Will your book be self-published or traditionally published?

The Lennox Jewel will be published by Sourcebooks, The Woodvilles by the History Press. Both are traditional publishers.

How long did it take you to write the first draft of the manuscript?

I’m still writing both of them.

What other books would you compare this to within your genre?

The Lennox Jewel is comparable to other biographical fiction, including my own novels. The Woodvilles is sort of like David Loades’ The Boleyns, except that his book about the Boleyns and mine is about the Woodvilles. I may not be able to say anything that profound for another twenty years.

Who or what inspired you to write this book?

It was Margaret’s own fascinating story that inspired me to write The Lennox Jewel. As for The Woodvilles, anyone who reads this blog knows I frequently post about the family, and it occurred to me that there’s a real need for a book that not only tells the story of the entire family, but sifts through all the myths and unsubstantiated rumors about them–the Woodvilles stealing the royal treasury, Jacquetta ruining Sir Thomas Cooke just to acquire a tapestry, Elizabeth Woodville ordering the execution of the Earl of Desmond, Elizabeth concealing the king’s death from Richard, Duke of Gloucester, and so on.

What else about the book might pique the reader’s interest?

Margaret Douglas isn’t an obscure character by any means, but her younger days are often overlooked in favor of her later years, when she was intriguing for her son to marry the Queen of Scots. My novel spends a great deal of time on the younger Margaret.

Similarly, other than Elizabeth, the members of the Woodville family have been comparatively neglected. Did you know that Anthony Woodville was William Caxton’s first patron in England? That Edward Woodville was praised for his valor by Ferdinand and Isabella?

And now it’s time for tagging! I’ve asked my friend DeAnn Smith to tell us about her upcoming novel, about Elizabeth Woodville’s daughter Anne, once she gets her website together.

I’m hopelessly bad at tagging, and I know a lot of people are very busy with the holidays, so I’d simply like to invite anyone who hasn’t participated, and who wants to, to consider himself or herself tagged, and join in!

December 14, 2012

The Last Search Terms Post of 2012

elizabeth woodville richard iii affair

Well, that explains a lot.

susan higginbotham disney

With my two cats and two dogs as my cute talking sidekicks.

bad news of susan higginbotham

Does this mean Disney won’t be making the movie after all?

katherine woodville is a same sex marriage supporter

She tried for years to get Edward IV and William, Lord Hastings to come out of the closet, but they just didn’t think England was ready.

why wasnt margaret of anjou popular

She didn’t wear the right clothes or have the right phone.

who advised edward ii info for kids

To be followed by the picture book: Edward and Hugh’s Very Bad Day

did catherine parr dislike anything

Nope. Not even asparagus.

what was katherine howard like was she nice

She was swell! Just ask Catherine Parr.

what happened to edward seymour when he died

Primary sources are almost are in agreement that he stopped living.

why did henry vii destroy titulus regius

His mother, Margaret Beaufort, had taken up origami, and it was the closest piece of paper handy.

how to make a paper anne boleyn hat

Just ask Margaret Beaufort.

December 11, 2012

Ten Reasons to Love the Tudors, and a Giveaway!

Lately online, I’ve seen people here and there complaining that they’re tired of the Tudors, or simply don’t like them. Some people simply can’t forgive the Tudors for supplanting the gentle, peace-loving, Maypole-dancing Plantagenets (particularly the saintly Richard III), while others are just sick of the Tudors because they’ve been such an enduringly popular subject of books, films, and television.

Admit it. You do love him.

But what, you say? You like the Tudors? You like reading about them? You might even have the stray Tudor collectible in your house? Never fear! You’re not alone. Here are ten reasons to proudly stand up and proclaim your Tudorphilia.

On Twitter, “Tudor” takes up a lot fewer characters than “Plantagenet.”

If you don’t like one of Henry VIII’s wives, there’s always five more to choose from.

They made great execution speeches.

The Tudors had Charles Brandon, Robert Dudley, and Sir Walter Ralegh. Richard III had Francis Lovell. Ever heard anyone talk about the sheer animal magnetism of Francis Lovell? Neither have I.

It is almost impossible to look bad in a Tudor gown.

Without “Greensleeves,” what tune would “What Child Is This” have been set to?

When you say you’re reading a book about Henry VIII, the chances are very slim you’ll have to explain who he is.

Without Shakespeare, young men trying to figure out whether they should avenge their father’s death at the hands of their uncle would be at a total loss as to which literary character to compare themselves to, and star-crossed lovers would be seriously short of role models.

The market for reproduction “B” pendants with pearls hanging from them would be practically nonexistent.

Admirers of Richard III would have no one to blame for propaganda.

And since you probably like Tudor novels as well, here’s your chance to win mine! For the holidays, I’m giving away two signed copies of Her Highness, the Traitor, my novel about Frances Brandon, Duchess of Suffolk, and Jane Dudley, Duchess of Northumberland. (Naturally, I’m not giving both of them to the same person.) You can enter on my blog, by commenting on this post on Facebook, or by commenting on it on Goodreads. Contest ends on midnight December 18, US Eastern Standard Time. Good luck, and I hope you’ll be getting some Tudor books for the holidays!

December 2, 2012

The Half-Hanged Man: A Guest Post by David Pilling

I’d like to welcome a guest poster, David Pilling, to my blog! Although my recent research has centered on the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, my first two novels were set in the fourteenth century, so it’s great to see some more novels written during this period. Here’s David!

Susan has very kindly given me a guest spot to talk about my new historical novel, “The Half-Hanged Man”. This is a tale of high adventure and romance set during the Hundred Years War between England and France.

I’ve wanted to write about the latter half of the 14th century for a long time. Even by medieval standards, this was a brutal and bloody era, with much of Europe plunged into dynastic wars. England under her warrior-king, Edward III, was at war with France and Scotland, and Spain and Italy were riven by internal conflicts. The constant fighting and general chaos offered rich pickings to savvy mercenary captains such as Sir John Hawkwood, Bertrand du Guesclin, Hugh Calveley and Robert Knolles, all of whom succeeded in making a fat profit while Christendom burned.

The Half-Hanged Man is the story of one such captain, though a fictional one. Like many of his peers, Thomas Page is a commoner, destined to rise to brief greatness by virtue of wielding a nifty sword. The book also follows the story of the Spanish courtesan known as the Raven of Toledo, and of Hugh Calveley, a particularly ruthless soldier and black-armoured giant with flaming red hair and incisors he had specially sharpened to terrify the French!

Throw into the mix are any number of battles and sieges, including the Battle of Auray (see pic above) in 1364, where the Franco-Bretons and Anglo-Breton armies hammered the life out of each other for possession of the Duchy of Brittany.

Below is an excerpt of Hugh Calveley’s memories of the epic Battle of Najéra…

Excerpt:

“I led my portion of the rearguard across the open ground to the right of the prince’s battalion, and surged into the first company of Castilian reinforcements as they tried to arrange into a defensive line. They were well-equipped foot with steel helms and leather jacks, glaives and axes, but demoralised and unwilling to stand against a charge of heavy horse. I skewered a serjeant in the front rank with my lance and rode over him as the men behind him scattered, yelling in fear and hurling their banners away as they ran.

If all the Castilians had behaved in such a manner, we would have had an easy time of it, but now Enrique flung his household knights into the fray. It had started to rain heavily, sheets of water blown by strong winds across the battlefield, and a phalanx of Castilian lancers on destriers came plunging out of the murk, smashing into the front rank of my division. A lance shattered against my cuisse, almost knocking me from the saddle, but I kept my seat and slashed at the knight with my broadsword as he hurtled past, chopping an iron leaf from the chaplet encircling his basinet, but doing no other damage.

My men held together under the Castilian charge, and soon there was a fine swirling mêlée in progress. I was surrounded by visored helms and glittering blades, men yelling and horses screaming, and glimpsed my standard bearer ahead of me, shouting and fending off two Castilians with the butt of his lance. Another Englishman rode in to help him, throwing his arms around one of the Castilians and heaving him out of the saddle with sheer brute strength, and then a fresh wave of steel and horseflesh, thrown up by the violent, shifting eddies of battle, closed over them and shut off my view.

I couldn’t bear to lose my banner again, and charged into the mass of fighting men, clearing a path with the sword’s edge. A mace or similar hammered against my back-plate, sending bolts of agony shooting up my spine, and my foot slipped out of the stirrup as I leaned drunkenly in the saddle, black spots reeling before my eyes.”

Intrigued? See the links to the Kindle and paperback below:

Paperback

Kindle

And links to my blog and joint website:

http://pillingswritingcorner.blogspot...

November 30, 2012

Heads Up! (Or Should It Be Heads Off?)

Nothing of substance to say, except that you can get the electronic version of Her Highness, the Traitor cheap today! It’s $2.99 in the United States and £1.99 in the UK.

Happy reading!

November 20, 2012

The Maligned Frances Grey, Duchess of Suffolk

On November 21, 1559, Frances, Duchess of Suffolk, died, age 42. (Strype gives the date as November 20.) An account of her death and her burial can be found here.

When I was doing my blog tour for Her Highness, the Traitor, I did a guest post for Claire Ridgway over at the Anne Boleyn Files about Frances’s historical reputation and the great extent to which it is undeserved. Claire has kindly allowed me to repost it here in honor of Frances’s death anniversary:

Few Tudor women—with the exception of Anne Boleyn—have become as enshrouded with myth as Frances Grey (née Brandon), Marchioness of Dorset and later Duchess of Suffolk, the mother of Lady Jane Grey. Stories abound of her greed, ruthlessness, gluttony, unbridled ambition, and cruelty.

As I found when reading Leanda de Lisle’s excellent biography of the Grey sisters and when conducting my own research for Her Highness, the Traitor, the real Frances Grey bears no resemblance to the lurid tales about her. Only in our own time has she become a controversial and loathed figure.

Frances Grey was the daughter of Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, and Henry VIII’s sister Mary, known as the French queen because of her brief marriage to Louis XII. Frances was born at Hatfield on July 16, 1517. In the spring of 1533, Frances married Henry Grey, Marquis of Dorset. Born on January 17, 1517, Henry was just a few months older than his new bride. With the death of Frances’s young half-brothers in 1551, Henry Grey was created Duke of Suffolk.

Probably in the spring of 1537, Frances gave birth to a girl, Jane, named after Henry VIII’s latest queen, Jane Seymour. Jane was the nineteen-year-old Frances’s third child: a son and a previous daughter died young.

It is with Jane’s birth that writers of popular nonfiction begin to wreak havoc with Frances’s reputation. Hester Chapman writes that the “Dorsets were disappointed at not having a son” when Jane was born, and goes on to state that Frances Grey “could not forgive” her daughters for their sex. Alison Weir writes that Henry Grey “regarded [Jane] as a poor substitute for the son who had died young before her birth.” In her truly execrable biography of Jane Grey, Mary Luke devotes two entire paragraphs to Frances’s longing to bear her husband a male child, ending with her “sobbing heartbreakingly” when she discovers she has borne a girl. Mary Lovell in her biography Bess of Hardwick writes that after the death of the Greys’ son, Frances gave birth to her daughters, “to whom their parents made it abundantly clear that they were a major disappointment.” None of these writers cite a source for their claim, for the very good reason that there is none. Frances and her husband might well have hoped for a son—parents of their class generally did—but there’s simply no evidence that they did not greet the birth of a daughter with happiness, particularly when the infant thrived instead of following her siblings to the grave. As Eric Ives points out, Henry and Frances Grey were not in the public eye when their most famous daughter was born, and neither her date of birth nor her place of birth has been recorded, much less her parents’ reactions to her arrival in the world.

Henry VIII died in 1547. Shortly afterward, the Greys performed the first act for which history has damned them—agreeing to Thomas Seymour’s request that they put Jane Grey in his wardship, in the hopes that Thomas would broker a match between Jane and the young king, Edward VI. This has been taken as proof of the Greys’ insatiable ambition, but what noble parent, given the opportunity to match their daughter with a king, would have passed up the chance? Like any other girl of her class, Jane would have been brought up with the expectation that she would marry for the good of her family. This was a two-way street: Jane would have also expected that her parents do their best for her future by marrying her to a high-status groom. Whether Jane was aware of these plans for her is unknown, but there is no reason to assume that the possibility of marriage to the king, her first cousin, would have displeased her.

It was in August 1550, however, that Frances made the biggest mistake of her life, at least in terms of her historical reputation. She went hunting with the rest of the household, and left her daughter Jane behind to greet a visitor, Roger Ascham. It was then that Jane made her famous complaint about her parents, recalled by Ascham years later, after Jane and her parents were all dead:

“For when I am in presence either of father or mother; whether I speak, keep silence, sit, stand, or go, eat, drink, be merry, or sad, be sewing, playing, dancing, or doing any thing else; I must do it, as it were, in such weight, measure, and number, even so perfectly, as God made the world; or else I am so sharply taunted, so cruelly threatened, yea presently sometimes with pinches, nips, and bobs, and other ways (which I will not name for the honour I bear them) so without measure misordered, that I think myself in hell, till time come that I must go to Mr Elmer; who teacheth me so gently, so pleasantly, with such fair allurements to learning, that I think all the time nothing whiles I am with him. And when I am called from him, I fall on weeping, because whatsoever I do else but learning, is full of grief, trouble, fear, and whole misliking unto me. And thus my book hath been so much my pleasure, and bringeth daily to me more pleasure and more, that in respect of it, all other pleasures, in very deed, be but trifles and troubles unto me.”

The impact of Ascham’s recollection on Frances’s reputation simply cannot be understated. Historians and novelists alike have used it to construct an image of Jane’s entire childhood as more Dickensian than anything that Dickens himself could have imagined, brightened only by Jane’s brief stay at Katherine Parr’s household. Any possibility that the adolescent Jane, like other intelligent adolescents, might have been exaggerating her complaints, that she might have spoken less harshly of her parents with time and maturity, or that her parents might have had genuine cause (by contemporary standards) for disciplining her has been ignored by all but a handful of writers.

Not content to extrapolate from Jane’s complaints, writers—even those professing to write nonfiction—have invented instances of Frances’s cruelty that simply have no historical basis. Mary Luke’s supposed biography of Jane treats us to vignettes of Frances shaking her infants. (Jane, adding an extraordinary memory to her other gifts, is even depicted by Luke as recalling the shakings.) Mary Lovell in her biography of Bess of Hardwick (a friend of Frances) tells us of Frances’s cruelty to her lower servants, despite the fact that none are on record of complaining about her. (Indeed, the only servant of Frances of which we know anything, Adrian Stokes, became her second husband.)

Frances’s one recorded absence on a hunting trip has given rise to its own series of legends. Although no one actually knows whether Frances enjoyed hunting or whether she went on hunting trips merely out of a sense of social obligation, this has not stopped authors like Hester Chapman from droning on about “her tireless enjoyment of open-air sports and indoor games,” or Alison Weir from assuring us that Frances was “never happier than when she was on horseback,” or Mary Luke from writing, “At Bradgate she could slaughter and maim to her heart’s content.” Luke also mentions the Greys’ dining “in the hall hung with the heads of Lady Frances’ unfortunate victims.” One can only hope that Luke was referring to deer.*

Even Jane’s fine education, so amply on display when Ascham visited, has been used against Frances and her husband. While other Tudor parents who gave their daughters classical educations are praised for their enlightened notions regarding women, the Greys’ education of Jane is treated as part of a long-term scheme to put their daughter upon the throne or, by more generous writers, as the Greys’ way of compensating for not having a living son. Some writers even depict the Greys as resenting Jane’s intellectual activities. Henry Grey’s patronage of scholars and his reputation as a man who was proud of his own learning are blithely ignored by these writers, as is the fact that had the Greys disapproved of their daughter’s fondness for learning, all they had to do was dismiss her tutors and take away her books. Instead, they allowed her to correspond internationally and to receive visits from scholars—even to skip the famous hunting trip of 1550.

Those who accuse Frances of being a cruel mother, of course, can also point to the fateful spring and summer of 1553, when Jane married Guildford Dudley and when the dying Edward VI made Jane his heir. Scholars have argued endlessly over whether the marriage was simply a standard aristocratic marriage or whether more sinister purposes were involved, and whether it was Edward VI himself or the Duke of Northumberland who originated the plan to put Jane on the throne, but no contemporary source suggests that Frances, whose claim to the throne was better than her own daughter’s, influenced these events. Jane Grey herself, writing in the Tower after Mary I had reclaimed the throne, put no blame on her own parents. Although some Italian sources maintain that Jane’s parents beat her in order to force her to marry Guildford, English sources tell no such lurid tale, and Jane never claimed that she had been physically forced to marry Guildford, although it certainly would have served her interests with Mary to be able to say so.

Following Mary I’s bloodless victory over Jane’s forces, Jane was imprisoned, as was her father. Frances traveled to Mary’s lodging and persuaded the new queen to free Henry Grey. It has been supposed that Frances made no attempt to beg for Jane’s freedom, but it may simply be that Frances asked but was refused. Likewise, Frances is not recorded as visiting Jane in prison, but her counterpart the Duchess of Northumberland, who is well known to have been working actively to get her sons released, is not recorded as paying such visits either. Frances seems to have been on good terms with Mary, her first cousin and her godmother, and perhaps she was working quietly behind the scenes in hopes of persuading Mary to free Jane. We can only speculate.

Any chance that Mary would spare Jane’s life, however, evaporated when Henry Grey joined Wyatt’s rebellion, after which Mary believed it necessary to execute Jane and Guildford for her continued security. (The notion that Mary executed Jane simply to guarantee that Philip of Spain would marry her is not borne out by the diplomatic correspondence.) Frances was not implicated in the rebellion. Again, there is no record of Frances pleading for Jane’s life, but there is no particular reason to believe that she didn’t. The fact that no farewell letter from Jane to Frances survives has been taken as proof that Jane disliked Frances so much that she chose not to write to her, but Michelangelo Florio, Jane’s Italian tutor, stated that Jane did in fact write to Frances. The letter may have been lost, or Frances may have chosen to destroy it.

Jane was executed on February 12, 1554, and Frances’s husband Henry Grey was executed on February 23, 1554. According to Frances’s postmortem inquisition, she married Adrian Stokes, variously identified as her master of horse, her steward, or her equerry, on March 9, 1554. Frances’s hasty marriage so soon after the executions of her husband and her daughter has been taken as proof of her heartless nature, but at least one near contemporary, Elizabeth I’s early biographer William Camden, believed that Frances made the match “to her dishonor, but yet for her security.” Marrying a commoner distanced Frances and her surviving children from the crown, ensuring that Mary would not see them as a threat.

Which brings us to The Picture. For centuries, the portrait shown here, of a stout, middle-aged woman and a much younger man, was identified as a portrait of Frances Brandon and Adrian Stokes. In Our Mutual Friend, Charles Dickens commented on Mrs. Wilfer’s “remarkable powers as a physiognomist; powers that terrified [her husband] when ever let loose, as being always fraught with gloom and evil which no inferior prescience was aware of.” Where Frances is concerned, popular historians have outdone Mrs. Wilfer. Hester Chapman, for instance, waxes eloquent: “In the picture of her and her second husband, painted shortly before her death, the small, piercing grey eyes have sunk, the reddened swollen cheeks hang in stiff folds, and the expression is one of greedy complacency. It is the face of a woman not so much coldly indifferent to the feelings of others as actively cruel.” The problem for Chapman, and others who have followed her lead, is that their efforts were sorely misdirected: the portrait in question was properly identified a number of years ago. It is not one of Frances and Adrian at all, but one of Lady Mary Neville and her son, Gregory Fiennes. The only depiction of Frances which can be identified with certainty, in fact, is the handsome effigy on her tomb, which, no doubt to the disappointment of her modern-day detractors, does not provide any opportunity for the Mrs. Wilfers of the world to wax sinister.

Frances is in a strange position, for unlike Anne Boleyn, Frances was not a controversial figure in her day. None of Frances’s contemporaries are known to have disliked her; when Sir Richard Morison groused about “Lady Suffolk’s heats” in May 1551, he was referring to Frances’s stepmother, the sharp-tongued and quick-tempered Katherine Brandon, and not to Frances, who did not hold the Suffolk title until later that year. No contemporary is on record as regarding Frances as an unusually harsh mother; even Roger Ascham, having repeated Jane’s remarks, did not see fit to criticize Jane’s parents, but moved on to his real subject— “why learning should be taught rather by love than fear.” Indeed, soon after Jane’s death, Frances was entrusted with the care of her husband’s niece, Margaret Willoughby, whose friends commented approvingly on Frances’s success in introducing the young girl at court. Even Mary Lovell is forced to acknowledge Bess of Hardwick’s apparent affection for Frances.

So what happened? What made Frances Grey one of the most intensely hated figures from Tudor history? One explanation is offered by Leanda de Lisle, who noted that as Jane’s reputation as a helpless, meek victim developed over the centuries, Frances’s reputation devolved in parallel fashion: “From the early eighteenth century, Frances became the archetype of female wickedness.”

But there is another reason, I think, why Frances has become such a loathed figure, at least among women – and that is Jane herself. Jane, the girl who preferred reading a book to hunting with the family, is the thinking girl’s heroine. She is the sort of girl who hated gym class, who hated going to family gatherings and having to make small talk with her dreary relations, who spent her lunch hour hiding out in the library. She is the sort of a girl who grows into a reader and, often, into a writer. When female readers and authors come across Jane’s complaint to Roger Ascham, they do not picture just Jane, but themselves.

In that situation, poor Frances doesn’t stand a chance.

*Apropos of Frances’s hunting, I can’t find it on Google now, but one book aimed at the academic market suggested in dead seriousness that if Frances were alive today, she would be a member of the National Rifle Association. The looniest reference to Frances’s supposed mania for outdoor pursuits I have ever come across, however, is a book, again nonfiction, which claimed that Frances was so fond of riding, she dressed Jane in jockey silks.

November 14, 2012

A Woodville Abroad: Anthony, Earl Rivers, in Italy

Galeazzo Maria Sforza, Duke of Milan. Did Anthony visit him? While abroad, did he develop a taste for parti-colored hose?

In the autumn of 1475, following Edward IV’s entry into the Treaty of Picquigny with Louis XI of France, Anthony, Earl Rivers, decided to do some traveling. Already he had gone on pilgrimage to Santiago: this time, his destination was Italy.

Edward IV, Anthony’s brother-in-law, paved the way. On October 1, 1475, he wrote a letter to Galeazzo Maria Sforza, Duke of Milan, informing him that Rivers, “one of his chief confidants and the brother of his dear consort,” would be traveling to Rome and would like to visit Milan and other places belonging to the duke, as well as the duke himself if it were convenient. Was Edward IV planning to have his brother-in-law conduct a little diplomacy?

Sadly, we do not have a detailed description of Anthony’s travels, or an account of whom he visited, but several years later, William Caxton, whose printing press Rivers patronized, recalled in his epilogue to The Cordyale (translated by Rivers) that Anthony had been on pilgrimage to Rome, to shrines in Naples, and to St. Nicholas at Bari. He had also obtained a papal indulgence for the Chapel of Our Lady of the Pew at Westminster, where Anthony hoped to be buried.

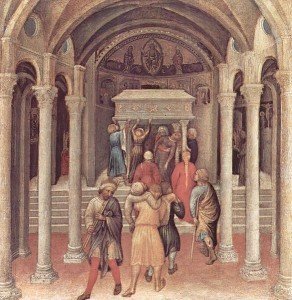

Gentile da Fabriano, Pilgrims at St. Nicholas at Bari

All did not go smoothly for the English traveler, however. On March 7, 1476, Francesco Pietrasancta, Milanese Ambassador to the Court of Savoy, reported to the Duke of Milan that all of Rivers’ money and valuables had been stolen at the Torre di Baccano and that Queen Elizabeth was sending a royal servant to Rome with letters of exchange for 4,000 ducats. The ambassador took the occasion to ask the unnamed servant about Edward IV’s lifestyle. “The king devotes himself to his pleasures and having a good time with the ladies” was the reply.

Anthony’s misadventures had also come to the attention of John Paston, who wrote on March 21, 1476, that Lord Rivers “was at Rome right well and honorably” and had traveled twelve miles outside the city when he was robbed of all of his jewels and plate, which were worth at least a thousand marks.

The saga of Anthony’s jewels did not end there, however. On May 10, 1476, the Venetian Senate issued this sinister-sounding decree:

That for the purpose of ascertaining the truth as to this theft, in the neighbourhood of Borne, of the precious jewels and plate belonging to Lord Anthony Angre Lord Scales, brother of the Queen of England, and for the discovery of the perpetrators and of the distribution made of the property,—Be the arrest of Nicholas Cerdo and Vitus Cerdo, Germans, Nicholas Cerdo, and Anthony, a German of Schleswick, dealer in ultramarine, (arrested by permission from the Signory,) ratified at the suit of the State attorneys; and as they would not tell the whole truth by fair means, be a committee formed, the majority of which to have liberty to examine and rack them all or each; and the committee shall, with the deposition thus obtained, come to this Council and do justice.

Three days later, the Senate issued another decree, showing that when traveling abroad, it was extremely helpful to have royal connections:

Lord Scales, the brother-in-law of the King of England, has come to Venice on account of certain jewels of which he was robbed at Torre di Baccano, near Borne. Part of them having been brought hither and sold to certain citizens, he has earnestly requested the Signory to have said jewels restored to him, alleging in his favour civil statutes, enacting that stolen goods should be freely restored to their owner. As it is for the interest of the Signory to make every demonstration of love and good will towards his lordship on his own account, and especially out of regard for the King, his brother-in-law,—Put to the ballot, that the said jewels purchased in this city by Venetian subjects be restored gratuitously to the said lord; he being told that this is done out of deference for the King of England and for his lordship, without his incurring any cost.

As the affair is committed to the State attorneys.—Be it carried that they be bound, together with the ordinary councils, to dispatch it within two months, and ascertain whether or not the purchasers of the jewels purchased them honestly. Should they have been bought unfairly, the purchasers to lose their money. While, if the contrary were the case, Toma Mocenigo, Nicolo de Ca de Besaro, and Marin Contarini shall be bound as they themselves volunteered to pay what was expended for the jewels, together with the costs, namely, 400 ducats. These moneys to be drawn for through a bill of exchange by these three noblemen on the consul in London, there to be paid by the consul and passed by him to the debit of the factory on account of goods loaded by Venetians in England on board the Flanders galleys (Ser Antonio Contarini, captain,) on their return to this city; and in like manner to the debit of the London factory here, on account of goods loaded on board the present Flanders galleys (Ser Andrea de Mosto, captain), bound to England, on their arrival in those parts. If the attorneys and the appointed councils fail to dispatch the matter as above, they shall be fined two ducats each; yet, on the expiration of the said term, the said three noblemen shall be bound to pay the moneys above mentioned.

Having recovered part of his jewels, Anthony resumed his travels. (As his stay had been an expensive one, it may be that the Venetians were not entirely sorry to see him on his way.) In June, he arrived at the camp of Charles, Duke of Burgundy, who was preparing to fight the Swiss. Giovanni Pietro Panigarola, the Milanese ambassador, reported on June 9 that Anthony planned to stay two or three days before returning to England. On June 11, however, he wrote, “M. de Scales, brother of the Queen of England, has been to see the duke and offered to take his place in the line of battle. But hearing the day before yesterday that the enemy were near at hand and they expected to meet them he asked leave to depart, saying he was sorry he could not stay, and so he took leave and went. This is esteemed great cowardice in him, and lack of spirit and honour. The duke laughed about it to me, saying, He has gone because he is afraid.” Whatever Anthony’s motives—it may simply be that he realized this was not his fight—his decision was a fortunate one, for at the battle of Morat that ensued on June 22, the duke lost thousands of men, and would lose his own life at the battle of Nancy six months later. Anthony’s decision to shirk this one battle meant that he would return to England with his life, if not all of his goods, intact.

Sources:

Calendar of State Papers, Milan

Calendar of State Papers, Venice

Norman Davis, ed., The Paston Letters

Cora Scofield, The Life and Reign of Edward IV

November 10, 2012

A Royal Christening: Bridget of York, November 11, 1480

On November 10, 1480, Elizabeth Woodville bore her last child–Bridget, named after St. Bridget of Sweden. Bridget may have been intended for the Church; in any case, she eventually became a nun at Dartford Priory.

The day after her birth, Bridget was christened at the chapel of Eltham. Her godmothers at the baptismal font, as the following account indicates, were her paternal grandmother, Cecily, Duchess of York, and her oldest sister, Elizabeth. Margaret, Lady Maltravers, a younger sister of Elizabeth Woodville, served as godmother at the confirmation. William Waynefleet, Bishop of Winchester, was the baby’s godfather. Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond, had the honor of bearing the infant. (The next royal christening would be that of Margaret’s own grandson, Arthur Tudor.)

A detailed description of Bridget’s christening has survived and was reprinted by an “F.M.” in the 1831 Gentleman’s Magazine. I have modernized the spelling when possible.

. . . the twentieth year of the reign of King Edward IV on St. Martin’s Eve was born the Lady Bridget, and christened on the morning of St. Martin’s Day in the Chapel of Eltham, by the Bishop of Chichester in order as ensueth:

First a hundred torches borne by knights, esquires, and other honest persons.

The Lord Maltravers, bearing the basin, having a towel about his neck.

The Earl of Northumberland bearing a taper not lit.

The Earl of Lincoln the salt.

The canopy borne by three knights and a baron.

My lady Maltravers did bear a rich crysom pinned over her left breast.

The Countess of Richmond did bear the princess.

My lord Marquess Dorset assisted her.

My lady the king’s mother, and my lady Elizabeth, were godmothers at the font.

The Bishop of Winchester godfather.

And in the time of the christening, the officers of arms cast on their coats.

And then were lit all the foresaid torches.

Present, these noble men ensuing:

The Duke of York.

The Lord Hastings, the king’s chamberlain.

The Lord Stanley, Stewards of the King’s house.

The Lord Dacre, the queen’s chamberlain, and many other estates.

And when the said princess was christened, a squire held the basins to the gossips [the godmothers], and even by the font my Lady Maltravers was godmother to the confirmation.

And from thence she was borne before the high altar. and that solemnity done she was borne eftsoons into her parclosse, accompanied with the estates aforesaid.

And the lord of Saint Joans [probably John St. John, according to Pauline Routh] brought thither a spice plate.

And at the said parclose the godfather and the godmother gave great gifts to the said princess.

Which gifts were borne by knights and esquires before the said princess turning to the queen’s chamber again, well accompanied as appertaineth, and after the custom of this realm.

I can’t leave this post without mentioning that recently, I have seen several people claim that Bridget was the mother of an out-of-wedlock child, Agnes of Eltham. The Wikipedia article about Agnes which makes this claim cites two sources–one a scholarly article about John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, the other Jeffrey Hamilton’s book on the Plantagenets. In fact, neither source even mentions Bridget or Agnes, much less claims that they were mother and daughter. I have no idea if this tale has any basis in fact, but given the Wikipedia author’s cavalier use of sources, I’m skeptical, to put it politely.

Sources:

“F.M.,” “Christening of the Princess Bridget, 1480.” Gentleman’s Magazine, January 1831.

Pauline E. Routh, “Princess Bridget.” The Ricardian, June 1975.

Anne F. Sutton and Livia Visser-Fuchs with R.A. Griffiths, The Royal Funerals of the House of York at Windsor. Richard III Society, 2005.