Susan Higginbotham's Blog: History Refreshed by Susan HIgginbotham, page 15

October 31, 2012

Lord Thomas Howard: Died October 31, 1537

Happy Halloween! For Lord Thomas Howard, however, All Hallow’s Eve was not a happy day. Since I shared his story on Facebook, I thought I’d post it here as well.

On October 31, 1537, Lord Thomas Howard died in the Tower of an ague. Thomas, a younger half-brother of Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, had been imprisoned in July 1536 for secretly marrying Lady Margaret Douglas, Henry VIII’s niece. Just a few days before his arrest, he had been jousting as part of the celebrations following his brother William’s wedding.

In his deposition on July 8, 1536, Thomas admitted that he had loved Margaret “about a twelvemonth,” during which period he had given her a cramp-ring, while she had given him her portrait and a diamond. Thomas said that they had contracted their marriage after Easter.

Thomas was not tried for treason, but was convicted through parliamentary attainder, a process which avoided the messiness of a public trial. In the attainder, he was accused of having “false craftily and traitorously . . . imagined and compassed, that in case our said Sovereign Lord should die without heirs of his body, which God defend, that then the said Lord Thomas, by reason of a marriage in so high a blood, and to one such which pretendeth to be a lawful daughter to the said Queen of Scots eldest sister of our said Sovereign Lord, should aspire by her to the Dignity of the said Imperial Crown of this realm.” The attainder concluded by declaring that Thomas would be executed, though in fact no moves were made to put him to death.

Margaret Douglas was also taken to the Tower, but was not attainted. After she fell ill, she was moved to Sion Abbey, where she lived rather comfortably. She and Thomas may have found a way to exchange love poems during their imprisonment, which appear in the collection of verses known as the Devonshire Manuscript.

At about the time of Thomas’s death, Margaret was released, just in time to take a leading role in Jane Seymour’s funeral procession. The chronicler Charles Wriothesley reported that she took Thomas’s death “very heavily.” Henry VIII allowed Thomas’s mother, the Dowager Duchess of Norfolk (known to us mainly for her allegedly lax supervision of Katherine Howard), to take his body, provided that she buried him “without pomp.”

Later, Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, would commemorate his uncle in verse. He wrote:

“For you yourself doth know, it is not long ago,

Since that for love, one of the race did end his life in woe,

In tower both strong and high, for his assured truth,

Whereas in tears he spent his breath, alas, the more the ruth.

This gentle beast likewise, who nothing could remove,

But willingly to seek his death for loss of his true love.”

October 29, 2012

Bring Out the Bodies and Move ‘Em: Some Modest Proposals

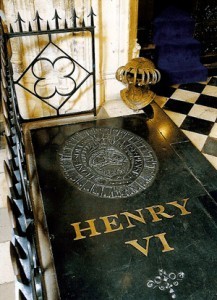

Henry VI’s resting place at Windsor. But maybe not for long . . .

Over the last few weeks, the topic of where Richard III (if the remains at Leicester prove to be his) should be reburied has been the subject of intense (and rather emotional) debate, centering around where the king would have preferred to have been buried. My modest proposal on Facebook that he be divided up in truly medieval style–one quarter at Leicester, one quarter at York, one quarter at Fotheringhay, one quarter at Westminister, and the head awarded to the highest-bidding Ricardian–was, sadly, not heeded by the authorities, so the debate still rages.

It will not be until December, as I understand, that the testing on the remains at Leicester will be completed, so there’s plenty of time to determine where the presumed Richard III will have his final resting place. So in the meantime, why not offer another candidate for reburial? Ladies and gentlemen, I give you Henry VI.

(First, you might say that as an American, it is really none of my business where the British government buries its dead monarchs. I beg to differ. As an American, it is my First Amendment right to express an opinion on anything I want. So sit back and drink your tea and listen.)

Henry VI, in case you might have forgotten, died in the Tower, supposedly of “sheer displeasure and melancholy” but most likely with the assistance of an agent of Edward IV, on the evening of May 21, 1471, hours after the return of the triumphant Yorkist king to London. He was buried at Chertsey Abbey. Later, Richard III ordered that he be moved to St. George’s Chapel at Windsor, where he remains today.

Now, St. George’s Chapel is a perfectly respectable resting place for a former king, but it doesn’t seem to have been where Henry himself wanted to rest. According to later depositions, Henry went to Westminster Abbey in the presence of witnesses and scouted out possible burial spots, even going so far as to pace out the distance himself with “his own feet.” So since we know Henry wanted to be buried at Westminster, why shouldn’t we right this centuries-old wrong and put the man in his preferred resting spot?

In fact, I think it’s time the entire Lancastrian royal family was reunited. Prince Edward, Henry’s son, fell at the battle of Tewkesbury and was buried in the abbey there. He has been made to spend eternity staring up at the Yorkist emblem of the Sun in Splendor, which really seems unfair for the young man to have to go through. Oh, sure, it’s a beautiful abbey and all, and he has the Despensers and the Duke of Clarence to keep him company, but doesn’t a man’s feelings count for anything?

And what of Margaret of Anjou? Having lived her last years in obscurity, she was buried at Angers, where no trace of her tomb remains. It’s true that she asked in her will to be buried by her parents at Angers, but that’s before she realized that later generations might be so accommodating of her true last wishes. Let’s bring Margaret back to her menfolk!

And speaking of the Woodvilles (OK, we weren’t, but on this blog we always speak of the Woodvilles at some point), Anthony Woodville made it clear in his will that he wanted to be buried at Westminster, at least before he found out that he was to be executed at Pontefract. Since Richard didn’t bother to give him a proper trial in front of his peers, can’t we at least set things a little right by giving Anthony the burial of his dreams? (Especially if Richard himself gets to be moved to York.)

And speaking of the Tudors (because it’s always fun to speak of the Tudors), think of all those poor souls executed at the Tower, some on very dubious grounds. Imagine the excitement if Anne Boleyn was brought up and reburied! Maybe we could take her to Windsor, where Henry VIII is buried with Jane Seymour, just to irritate Great Harry. (After all, with Henry VI moved to Westminster, there will be some room at Windsor for Anne.)

So what are we waiting for? Let’s start digging!

October 24, 2012

Three Diseases in One Body: Frances, Duchess of Suffolk, Gets Sick

In August 1552, Frances Grey, Duchess of Suffolk, fell seriously ill, forcing her husband, Henry Grey, Duke of Suffolk, to make a mad dash from court to her bedside. On August 26, Suffolk wrote a hasty letter to William Cecil to explain his abrupt departure. As printed in part by Agnes Strickland (I have a photograph of the letter, but can’t make out the duke’s handwriting well enough to transcribe it myself), the letter reads, “This shall be to advertise you that my sudden departing from the court was for that I had received letters of the state my wife was in, who, I assure you, is mo liker to die than to live. I never saw a more sicker creature in my life than she is. She hath three diseases. The first is a hot burning ague, that doth hold her twenty-four hours, the other is the stopping of the spleen, the third is hypochondriac passion. These three being enclosed in one body, it is to be feared that death must needs follow. . . . From Richmond, the 26 of August, by your most assured and loving cousin, who, I assure you, is not a little troubled.”

What was ailing Frances in August?

“Hot burning ague” is self-explanatory. As for “stopping of the spleen,” a 1656 book of remedies entitled The Skilful Physician, edited in a modern edition by Carey Balaban et al., explains: ”And sometimes [the spleen] is greater, fuller, or grosser than it ought to be, by overmuch melancholy that is not natural, caused of the dregs of the blood engendered in the liver, & doth hinder generation of good blood, wherethrough the members become dry, for default of good nourishing. And therefore the patient is called splenetic, which ye may know by that, that after meat they have pain in their left side and are always heavy, and hath their faces sometimes inclining unto blackness.”

In his 1615 manual The English Housewife (edited in a modern edition by Michael Best), Gervase Markham gave the following remedy for “stopping of the spleen”: “Take fennel seeds and the roots, boil them in water, and after it is cleansed put to it honey and give it the party to drink, then seethe the herb in oil and wine together, and plasterwise apply it to the side.”

“Hypochondriac passion” gave Suffolk some trouble; he apparently changed his mind about the spelling of the first word, crossing it out and then rewriting it. As for what it was, its meaning appears to have changed over the years; what Frances had was not what we would describe as hypochondria. While I couldn’t find much about the disease as it was known in Frances’s day, later sources abound with descriptions of it. In the eighteenth century, at least, it was much confused with something called the hysteric passion, which, as Richard Brookes noted in 1765 in The General Practice of Physic, was a different malady altogether:

The hysteric differs from the hypochondriac Passion, inasmuch as that the latter is a tedious Disease, and requires a tedious Cure. The Hysteric Passion attacks Women who are pregnant, in Childbed; Widows who are full of Blood, after some grievous Passion of the Mind, or Maids after a sudden Suppression of the menstrual Flux ; and yet it may be so certainly cured as never to return. It likewise oftentimes comes on so suddenly, violently, and at unawares, that, being deprived of all Sense and Motion, they immediately fall down, which the Hypochondriac are not subject to. The Hysteric likewise have this peculiar, that they may soon be brought to their Senses, only by burning Feathers under their Nose. In hysteric Cases, the Belly and Navel are drawn inward; in the Hypochondriac they stand out. . . . .nor have [those suffering from hypochondriac passion] such frequent tainting Fits, nor an Apprehension of Suffocation, nor Strangling, as the Hysteric; nor, last of all, are any of these in Danger of being laid out for dead.

Brookes went on to explain:

The Hypochondriac Passion is a spasmatico-flatulent Affection of the Stomach and Intestines, arising from an Inversion or Perversion of their peristaltic Motion, and, by Consent of Parts, throwing the whole nervous System into irregular Motions, and disturbing the whole animal Economy.

This Disease is attended with such a Train of Symptoms, that it is a difficult Task to enumerate them all; for there is no Function, or Part of the Body, that is not soon or late a Sufferer by it’s Tyranny. It begins with Tensions, and windy Inflations of the Stomach and Intestines, especially under the spurious Ribs of the left Hypochondrium, in which a pretty hard Tumour may sometimes be perceived.

With regard to the Stomach, there is a nausea, a Loathing of Food, an uncertain Appetite, sometimes quite decayed, and sometimes strong; the Aliments are ill digested, breeding acid and viscid Crudities ; there is a pressing heavy Pain in the Stomach, chiefly after Meals; a spasmodic Constriction of the Gullet, a frequent Spitting of limpid Phlegm, an Impediment in Swallowing, a violent Heart-burn, a Heat at the Stomach, very acid Belchings, a Reaching to vomit, Vomiting, bringing up such acid Stuff, that the Teeth are not only set on an Edge thereby, but the very Linen or Sheets are sometimes corroded.

As if these weren’t enough, Brookes goes on industriously to list a host of other unpleasant symptoms, which include bloody stools, difficulty urinating, difficulty breathing, headaches, double vision, sweating, a burning tongue, and a “plentiful Excretion of Spittle.” Not surprisingly:

At length the animal Functions are impaired; the Mind is disturbed on the most trivial Occasions, and is hurried into the most perverse Commotions, Inquietudes, Anxieties, Terror, Sadness, Anger, Fear, or Diffidence. The Patient is prone to entertain wild Imaginations, and extravagant Fancies; the Memory grows weak, and the Reason fails.

Brookes went on to say that the condition affected those who were “soft, lax, and flabby” or who were “naturally languid.” He added that the disease also affected “those who lead sedentary lives, and study too hard; insomuch that this is the peculiar disease of the learned.” (But wasn’t Frances supposed to have spent all of her time on a horse when she wasn’t beating her studious daughter?)

There was hope, however, for the eighteenth-century sufferer. To treat the condition, Brookes recommended (among other remedies) laxatives made of various herbs, but warned, “If there is a great deal of acid Filth in the Stomach, Crabs’ Eyes alone will purge.”

The paroxysms associated with the disease were to be treated by “tepid Pediluvia, made of Wheat Bran, Water, and Camomile-Flowers. The Feet must be put pretty deep within.”

The foot bath sounds rather pleasant, but alas, Brooks had another treatment as well: “If there is a disposition to an hemorrhoidal Flux, Leeches should be applied every month to the Anus.”

With the leeches having made their appearance in a place where most people would prefer not to have leeches, we shall say good-bye to our friend Brookes and make a happy return to the twenty-first century. As for Frances, her husband’s fears were for naught: if she tried her own era’s version of these or Brookes’ other suggested remedies, they must have worked, for she was well enough the following February to greet the Lady Mary when she came to visit Edward VI’s court. She was to live another seven years. History does not record whether she had another attack of hypochondriac passion, but for her sake, I hope not.

October 3, 2012

Making Babies and Dressing Meat: Visits from the Family, Tower-Style

While those imprisoned at the Tower in Tudor England could expect to receive official visitors, such as royal officials charged with the task of interrogating them, or spiritual visitors, brought in to give comfort or in some cases for the monarch’s own purposes, some lucky individuals got to receive more welcome sort of visitors—their own loved ones.

The following is by no means an exhaustive account of those Tudor prisoners who received visits from family members—only the ones I ran across in researching Her Highness, the Traitor.

Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, imprisoned by Henry VIII, was allowed by Edward VI’s council to receive visits from his wife, the Duchess of Norfolk, and his daughter Mary Fitzroy, the Duchess of Richmond, in February 1550. Since the duke and his wife had been estranged in the years before his imprisonment, one wonders whether Norfolk was particularly enthusiastic about the prospect of meeting her. Perhaps the Lieutenant of the Tower, who was to be present during these visits, was required as a referee! The Duchess of Richmond, however, had been diligently working to get her father set free, and had succeeded in making his lodgings more comfortable by getting tapestries hung and his windows glazed, so she was probably a welcome sight to her aging father. The council seems in fact to have given the Duchess of Richmond permission to visit her father before the official order was given: On December 15, 1549, Richard Scudamore reported that the duchess had been allowed by the council to visit Norfolk and had sat with him the day before “by the space of ii long howres.”

Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, was confined twice in the Tower. Scudamore reported that during his first imprisonment, which lasted from October 1549 to February 1550, the Duchess of Somerset spent Christmas Day of 1549 with her imprisoned husband “to his no little coumfort.”

The Duchess of Somerset herself was sent to the Tower as a prisoner in October 1551, shortly after her husband was imprisoned for a second time. In June 1552, the privy council ordered that Lady Page, her mother, be allowed to “resort to” her now-widowed daughter, the Duke of Somerset having been executed in January 1552. Lady Page must have been a particularly devoted mother, for rather than simply visiting her daughter, she appears to have moved into the Tower with her. A list of the duchess’s “diets” while in the Tower indicates that while the lieutenant was given an allowance for the duchess’s expenses, he was not given such for “the lady Page, being for the most part with the said Duches.”

When Mary came to the throne, both the Duke of Norfolk and the Duchess of Somerset were released from captivity, but the ill-fated attempt to put Lady Jane Grey on the throne brought a host of prisoners to take their places. I have found nothing to indicate that John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, Jane Grey, or her husband Guildford Dudley were allowed to receive family visitors, but other captives were more fortunate. In September 1553, several ladies were given permission by the privy council “to have access unto their husbands, and there to tarry with them so long and at such times as by [the lieutenant of the Tower] shall be thought meet.” The ladies included the wives of Ambrose and Robert Dudley, the wife of Francis Jobson, the wife of Sir Henry Gates, and the wife of Sir Richard Corbett. In addition, the Tower chronicler reported that about this time, the wife of John Dudley, Earl of Warwick (Northumberland’s eldest son), was allowed to visit her husband. Nothing indicates that the Duchess of Northumberland was allowed to visit her imprisoned sons, although she would spent the next months working mightily to get them freed.

One man had already succeeded in persuading the council to allow him a spousal visit: the aged Sir Edward Montague, the chief justice of the common pleas. In August 1553, he was allowed not only the privilege of taking the open air, but “to suffer the Lady, his wife, in consideration of his weakness, to repair to him at convenient times to dress his meat.”

Finally, what of those couples who were prisoners in the Tower at the same time? There is no indication that the Duke and Duchess of Somerset, imprisoned in October 1551, were allowed to meet before the duke’s execution in January 1552. Contrary to the movie Lady Jane, which depicts Jane Grey and Guildford being allowed to spend their last night on earth together engaging in passionate pre-execution sex, nothing indicates that the couple met privately during their imprisonment, although they saw each other at their joint trial in November 1553 and might have glimpsed the other strolling about the Tower grounds on other occasions. Indeed, Jane is said to have refused the chance to embrace and kiss her husband before their deaths, on the ground that it would only increase the couple’s misery and that they would meet shortly elsewhere.

Jane’s younger sister, Katherine, and her husband Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford, were imprisoned in 1561 for marrying without Elizabeth I’s consent. In 1462, Edward bribed his guards to allow him to visit his wife on two occasions. The couple made good use of their time, for the result of their visits, Thomas Seymour, was born on February 10, 1563.

Sources:

Acts of the Privy Council of England.

Susan Brigden, “The Letters of Richard Scudamore to Sir Philip Hoby, September 1549-March 1555,” Camden Miscellany XXX (1990).

Leanda de Lisle, The Sisters Who Would Be Queen.

John Gough Nichols, “Anne, Duchess of Somerset.” Gentleman’s Magazine, April 1845.

John Gough Nichols, ed., The Chronicle of Queen Jane and Two Years of Queen Mary.

September 23, 2012

The Fighting Woodvilles

One of the more bizarre anti-Woodville statements I have read online is that the Woodvilles took no part in the Wars of the Roses—the implication being that they stood by and let others do the fighting. I hope this post, dealing with the military record of Richard Woodville, first Earl Rivers, and his sons, will show just how nonsensical that statement is.

Richard Woodville, first Earl Rivers

Knighted on May 19, 1426 by the young Henry VI, who also knighted Richard, Duke of York on that day, Richard Woodville spent much of his military career serving against the French. He is said to have been taken prisoner at Gerberoy in 1435, but was serving under William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk, the following year. In 1439, he was among those troops coming to the relief of Meaux; in 1441, he came to the relief of Pontoise. He first played a military role on English soil in 1450, when he was among those commissioned to suppress Jack Cade’s rebellion.

Lord Rivers became Lieutenant of Calais around December 1451. When the Duke of York, then serving as Protector for the mentally ill Henry VI, appointed himself Captain of Calais in 1454 in place of Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, the garrison, serving under Rivers and Lionel, Lord Welles, refused to acknowledge his authority. Only Somerset’s death at the first battle of St. Albans in 1455 enabled York’s allies to take control of Calais. Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, entered Calais as its captain in July 1456, and Rivers surrendered his post.

Following the flight of York and Warwick abroad in 1459, the new Duke of Somerset, Henry Beaufort, attempted to dislodge Warwick from Calais. Rivers, stationed at Sandwich, was in the midst of preparing a fleet to come to his aid when on 19 January 1460, John Dynham made a surprise attack. He dragged Lord Rivers, his lady, and their eldest son, Anthony, from their beds and bundled the men upon a ship bound for Calais. Upon their arrival, they were paraded by torchlight before Salisbury, Warwick, and March, who improved the occasion by taunting the men with their comparatively lowly origins.

How long Rivers and his son remained prisoners is unknown, but there is no record of them fighting again until the battle of Towton in March 1461, when they fought against the new king, Edward IV. As reported by the chronicler Waurin:

There, Edward had scarcely time to regain his position under his banner when Lord Rivers and his son with six or seven thousand Welshmen led by Andrew Trollope, and the Duke of Somerset with seven thousand men more, charged the Earl of March’s cavalry, put them to flight and chased them for eleven miles, so that it appeared to them that they had won great booty, because they thought that the Earl of Northumberland had charged at the same time on the other flank, but he failed to attack soon enough, which was a misfortune for him as he died that day. In this chase died a great number of men of worth to the Earl of March [Edward IV] who, witnessing the fate of his cavalry was much saddened and angered: at which moment he saw the Earl of Northumberland’s battle advancing, carrying King Henry’s banner; so he rode the length of his battle to where his principal supporters were gathered and remonstrated with them.

Edward IV, of course, scored a victory at Towton, after which Anthony Woodville was mistakenly reported dead and Rivers was said to have fled with Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou to Scotland. In fact, Anthony was very much alive, and if Rivers went to Scotland, he did not stay there long. Like many Lancastrians, the Woodvilles gave up on Henry VI’s cause after that battle and pledged their allegiance to Edward IV.

Towton seems to have been the last military engagement of Rivers. Following the shocking marriage of his daughter Elizabeth to the king in 1464, he was made Earl Rivers and treasurer of England. He and his son John were executed in 1469, entirely illegally, at the orders of the Earl of Warwick.

Anthony Woodville

Anthony, as noted earlier, was captured with his father at Sandwich in 1460 and fought at Towton in 1461. His first military engagement as a Yorkist was in December 1461, when he and the Earl of Kent besieged Alnwick.

In 1470, Warwick, having rebelled against Edward IV, set off for Calais and sent Sir Geoffrey Gate to Southampton to retrieve his ship, the Trinity, from its dock at Southampton. Edward, however, was ready for him and had already ordered Anthony to guard Southampton. Unlike the debacle at Sandwich years before, Anthony was ready for attack. He captured a number of their ships and many of those on board. Barred from Calais, Warwick turned to piracy and captured about forty vessels, fourteen of which were later lost to Anthony and Hans Voetken after a fight at sea where five to six hundred men were killed.

The following year, Anthony fought at Barnet. His role there is unrecorded, but P. W. Hammond suggests that he might have commanded the reserve. He certainly seems to have played an active part there, for in a newsletter, the merchant Gerhard von Wesel reported that “the duke of Gloucester and Lord Scales [Richard, Duke of Gloucester and Anthony Woodville] were severely wounded, but they had no harm from it, God be praised.”

Anthony did not accompany the king’s forces to the next battle at Tewkesbury, but remained in London, which he and the Earl of Essex defended against a Lancastrian attack by the Bastard of Fauconberg. Though Lynda Pidgeon minimizes Anthony’s role, stating that he only “helped ” defeat Fauconberg, contemporaries were not so dismissive, as Arlene Okerlund notes in her biography of Anthony’s sister. The Historie of the Arrivall of Edward IV reported:

And, so after continuing of much shot of guns and arrows a great while, upon both parties, the Earl Rivers, that was with the Queen, in the Tower of London, gathered unto him a fellowship right well chosen, and habiled, of four or five hundred men, and issued out at a postern upon them, and, even upon a point, came upon the Kentish men being about the assaulting of Aldgate, and mightily laid upon them with arrows, and upon them with hands, and so killed and took many of them, driving them from the same gate to the water side.

The Crowland chronicler also singled out Anthony for praise:

God, however, being unwilling that a city so renowned, and the capital of the whole kingdom of England, should be delivered into the hands of such wretches, to be plundered by them, gave to the Londoners stout hearts, which prompted them to offer resistance on the day of the battle. This they were especially aided in doing by a sudden and unexpected sally, which was made by Antony, earl Rivers, from the Tower of London. Falling, at the head of his horsemen, upon the rear of the enemy while they were making furious assaults upon the gate above-mentioned, he afforded the Londoners an opportunity of opening the city gates and engaging hand to hand with the foe; upon which they manfully slew or put to flight each and every of them. Then might you have seen all the remnants of this band of robbers hastening with all speed to their ships and other hiding-places.

Anthony even rated a poetic tribute in “On the Recovery of the Throne by Edward IV”:

The earl Rivers, that gentle knight,

Blessed be the time that he borne was!

By the power of God and his great might,

Through his enemies that day did he pass.

The mariners were killed, they cried “Alas!”

***

God would the earl Rivers there should be;

He purchased great love of the commons that season;

Lovingly the citizens and he

Pursued their enemies, it was but reason,

And killed the people for their false treason . . .

In July 1471, Anthony wanted to Portugal to fight the Saracens, a request that according to John Paston angered the king, who grumbled that when he “has most to do, then the Lord Scales will soonest ask leave to depart, and when that it is most because of cowardice.” Since Anthony would have been leaving an England at peace to fight abroad, it is hard to understand why this has been taken as proof by Pidgeon that Anthony shied away from the reality of combat.

Whether Anthony actually went to Portugal is unclear. John Paston reported that men said that he left on Christmas Eve, but that Paston himself was not certain of it. If he did go, he did not stay long, for in April 1472, Anthony and his younger brother went to Brittany—at Anthony’s own expense–with a thousand men in order to repel a French invasion. The French withdrew in August 1472.

The one battle Anthony can be said to have shirked was in 1476, when Anthony, who was traveling about Europe, visited Charles, Duke of Burgundy, in his camp. The duke was preparing to fight the Swiss. The Milanese ambassador, Giovanni Pietro Panigarola, reported on June 9 that Anthony planned to stay two or three days before returning to England. On June 11, however, he wrote, “M. de Scales, brother of the Queen of England, has been to see the duke and offered to take his place in the line of battle. But hearing the day before yesterday that the enemy were near at hand and they expected to meet them he asked leave to depart, saying he was sorry he could not stay, and so he took leave and went. This is esteemed great cowardice in him, and lack of spirit and honour. The duke laughed about it to me, saying, He has gone because he is afraid.” Whatever Anthony’s motives—it may simply be that he realized this was not his fight—his decision was a fortunate one, for at the battle of Murten that ensued on June 22, the duke lost several thousand men. He himself was killed at the battle of Nancy only six months later.

In March 1483, Antony asked his business agent, Andrew Dymmock, to send him the patent given to him by the king to “raise people, if need be, in the march of Wales.” This request has been given sinister connotations by some, who have proposed on the scantest of evidence that Anthony was paving the way to poison Edward IV and seize power through his nephew, Prince Edward. In fact, trouble was brewing with both Scotland and France, and it is more likely that Anthony was simply preparing for the eventuality that it would be necessary to raise troops. In the event, he would never get the chance, but was taken prisoner by Richard, Duke of Gloucester just weeks later when trying to bring Edward V to London to be crowned king. He was executed without proper trial on June 25, 1483.

Richard Woodville, third Earl Rivers

Very little is known about Richard Woodville, who became Earl Rivers after the death of his older brother Anthony. In 1462, he was pardoned by Edward IV for his adherence to the Lancastrian cause, so it is possible that he had fought at Towton with his father and brother Anthony. In 1469, he captured Thomas Danvers, an accused Lancastrian plotter. He is not documented as fighting at Barnet or Tewkesbury or in London beside his brother, but it is possible that he took part but was simply too insignificant to mention.

In the autumn of 1483, Richard Woodville was among the rebels against Richard III who rose at Newbury. Why he escaped execution along with other rebels is unknown; perhaps he went into sanctuary. He is not mentioned as being present at Bosworth, but he was restored to his estates by the victorious Henry VII. Nothing indicates whether he was present at Stoke. He died on March 4, 1461, the only one of the five Woodville brothers to die neither violently nor in sanctuary.

John and Lionel Woodville

John was executed alongside his father on the orders of the Earl of Warwick in 1469. Like his brother Richard, he may have fought at Towton, but there is no mention of it.

Lionel was educated for the Church and became Bishop of Salisbury in 1482. Along with his brother Richard, he joined the rebellion against Richard III in 1483: he, Walter Hungerford, Giles Daubenay, and John Cheyne planned an uprising at Salisbury. The rebellion, of course, failed, and Lionel fled to sanctuary at Beaulieu Abbey, where he died in 1484.

Edward Woodville

The youngest of the Woodville brothers, Edward, is the Woodville with the most colorful—and ultimately fatal—military career.

Edward made his first recorded military appearance in April 1472, when he accompanied Anthony to Brittany with 1,000 archers. Ten years later, when Richard, Duke of Gloucester, led an army against the Scots, Edward Woodville served as one of Richard’s lieutenants, with five hundred men in his contingent; when he passed through Coventry, the town contributed twenty pounds in lieu of men. Ironically, Richard made him a knight banneret on July 24, 1482.

In 1483, when Philippe de Crèvecoeur, known as Lord Cortes, took advantage of Edward IV’s death to raid English ships, Edward V’s council appointed Edward Woodville to deal with this French threat. On April 30, he took to sea with a fleet of ships. That same day, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, and Henry, Duke of Buckingham, took Anthony Woodville and others prisoner at Northampton, claiming on very dubious grounds that the Woodvilles had been plotting against them.

Edward and his fleet gathered at Southampton, where Edward seized ₤10,250 in English gold coins from a vessel there, claiming that it was forfeit to the crown. Meanwhile, having gained control of the young king, the future Richard III appointed men to seize Edward Woodville. According to Mancini, the Genoese captains of two of the ships, fearing reprisals against their countrymen in England if they disobeyed Gloucester’s orders, encouraged the English soldiers on board to drink heavily, then bound the befuddled men in with ropes and chains. With the Englishmen immobilized, the Genoese announced their intent to return to England, and all but two of the ships, those under the command of Edward Woodville himself, followed suit. Rosemary Horrox, however, suggests more prosaically that this vinous tale aside, the majority of Edward’s captains simply recognized Gloucester’s authority as protector and obeyed his orders accordingly.

Edward Woodville—perhaps with his gold coin seized at Southampton, unless he had had the misfortune to place it on one of the deserting ships—sailed on to Brittany, where he joined Henry Tudor. When Henry sailed to England in the autumn of 1483 to join the ill-fated rebellion against Richard III, it seems likely that Edward would have been with him, since his brothers Richard and Lionel were involved in the rebellion and his brother-in-law the Duke of Buckingham was the highest-ranking rebel. In the event, Henry sailed into Poole harbor but, suspecting that the friendly soldiers who urged him to disembark were supporters of Richard III, sailed back to Brittany.

Henry made a rather more successful voyage to England in 1485. The Crowland chronicler described Edward as one of his leaders at the battle of Bosworth: a “brother of Queen Elizabeth and a most courageous knight.” A few weeks after the Tudor victory at Bosworth, Edward was granted Porchester and the Captaincy of the Isle of Wight, which included the lordship of Carisbrooke Castle.

A quiet life on the English coast, however, did not appeal to Edward. In 1486, calling himself “Lord Scales,” he went to fight the Moors in Granada, serving in the armies of Ferdinand and Isabella. At Loja, he and his forces were successful in putting the Moors to flight, but the encounter cost Edward his front teeth. He is said to have said to a sympathetic Queen Isabella, “Christ, who reared this whole fabric, has merely opened a window, in order more easily to discern what goes on within.” Edward was sent home to England with a rich array of gifts, including twelve horses, two couches, and fine linen.

The next year saw Edward in battle again, this time in England against forces led by John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, in support of Lambert Simnel, a young pretender to the throne. After three days of skirmishing near Doncaster, Edward’s troops were forced to retreat through Sherwood Forest to Nottingham. At the Battle of Stoke, however, where Edward Woodville commanded the right wing, victory went to Henry VII.

In May 1488, Edward “either abhorring ease and idleness or inflamed with ardent love and affection toward the Duke of Brittany,” as Hall’s chronicle has it, asked Henry VII to allow him to assist the duke in fighting the French. Henry VII, who hoped for peace with France, refused the request, but Edward ignored this and returned to the Isle of Wight, where he raised four hundred “tall and hardy personages” and sailed to Brittany. Henry then reconsidered and decided to send Woodville reinforcements, but the French arrived in Brittany before this could be done. At St. Aubin-du-Cormier on July 27, 1488, Edward Woodville fought his last battle. Almost all of his troops perished, as did Edward himself—the last fighting Woodville.

Sources:

Michael Bennett, Lambert Simnel and the Battle of Stoke.

Calendar of State Papers, Milan.

Norman Davis, ed., The Paston Letters.

English Heritage Battlefield Report: Towton 1461.

Louise Gill, Richard III and Buckingham’s Rebellion.

P. W. Hammond, The Battles of Barnet and Tewkesbury.

Mary Dormer Harris, ed., The Coventry Leet Book.

Michael Hicks, Warwick the Kingmaker.

Susan Higginbotham, The Woodvilles (forthcoming).

Rosemary Horrox, Richard III: A Study in Service.

Eric Ives, “Andrew Dymmock and the Papers of Antony, Earl Rivers, 1482-3.” Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, 1968.

Hannes Kleineke, “Gerhard von Wesel’s Newsletter from England, 17 April 1471.” The Ricardian, 2006.

Arlene Okerlund, Elizabeth, England’s Slandered Queen.

Lynda Pidgeon, “Antony Wydeville, Lord Scales and Rivers: Family, Friends and Affinity.” Parts 1 and 2. The Ricardian (2005 and 2006).

Nicholas Pronay and John Cox, eds., The Crowland Chronicle Continuations, 1459–1486.

Charles Ross, Edward IV.

Cora Scofield, The Life and Reign of Edward the Fourth.

Richard Vaughan, Charles the Bold.

Christopher Wilkins, The Last Knight Errant.

Thomas Wright, ed., Political Poems and Songs Relating to English History.

September 20, 2012

10 Most Peculiar Things I Have Heard Since the Leicester Dig

As anyone who is reading this blog knows, last week, following an archaeological dig at Leicester, a skeleton was unearthed that may well prove to be that of Richard III. Needless to say, this has led to a flurry of online discussion about Richard and, of course, the age-old question of whether he was responsible for the deaths of his nephews.

This has generated some thoughtful commentary, but it has also generated some magnificently peculiar (or just stupid) statements, ten of which I have thoughtfully preserved below. Read ‘em and cringe.

Richard III was a martyr.

Henry VII had only a rudimentary command of English.

The bones found in the Tower and identified as those of the princes were actually those of chimps.

One of the sets of bones found in the Tower was that of a commoner with rickets. (How could they tell that the unclothed bones belonged to a commoner, you might ask? Presumably, he had a “C” carved into his skull.)

The skeleton found at Leicester shows signs of scoliosis; therefore, it cannot be Richard because the Tudors said that Richard had deformities, and anything the Tudors said about Richard was wrong.

Richard did not execute women or bishops; therefore, he could not have killed the princes. (Henry VII did not execute women or bishops either, but he of course is fingered as a prime suspect.)

Edward IV’s sons were not kept prisoners in the Tower because the Tower of London was not a “true prison” until Tudor times. (Among others, this would surprise Gruffudd ap Llywelyn, Roger Mortimer and his uncle, Eleanor de Clare, Charles, Duke of Orleans, Edmund Beaufort, first Duke of Somerset, Edmund Beaufort, third Duke of Somerset, Henry VI, Margaret of Anjou, and Henry Holland, Duke of Exeter, all of whom were imprisoned there well before anyone started humming “Greensleeves.”)

Titulus Regius was Henry VII’s document overturning the Act of Succession.

The Leicester’s skeleton’s feet may have been chopped off because the grave was not the right length.

Richard III was the last English king.

September 8, 2012

Lady Elizabeth Scales: First Wife of Anthony Woodville

Anthony Woodville, Earl Rivers, married twice: the first time to Elizabeth Scales, the second time to Mary FitzLewis. This post is about his first wife, Elizabeth Scales.

Elizabeth was the daughter of Thomas, Lord Scales, and his wife, whose name is spelled variously as Ismania, Ismanie, and Esmania. Ismania was a daughter of a Cornishman named Whalesburgh. Described in Anthony’s inquisitions postmortem as 24 or more at her father’s death in 1461, Elizabeth Scales was born around 1437. Besides Elizabeth, Lord Scales and his wife had a son, Thomas, who predeceased his father.

Elizabeth Scales’ mother was one of the principal attendants of Henry VI’s queen, Margaret of Anjou, receiving forty pounds per annum in 1452-53.

Lord Scales, born around 1399, had a long record of military service in France, where he remained almost continually from 1424 to 1449. He was made lieutenant-general of western Normandy in 1435; it is possible that Elizabeth was born there. At Rouen in 1442, Lord Scales had served as a godfather at the christening of the future Edward IV.

Lord Scales was at his principal manor at Middleton at Christmas 1445 when the mayor and council presented a nativity play there, with a cast that included a John Clerk as the Virgin Mary and a person with the surname of Gilbert as the angel Gabriel. The nine-year-old Elizabeth would have been at an age to enjoy this thoroughly.

Elizabeth’s father had strong ties with the Woodville family from early on. Created a Knight of the Garter in 1425, Lord Scales nominated Anthony’s father, Richard Woodville, Lord Rivers, as a Garter knight in 1450. That same year, Lord Scales and Lord Rivers were among the men appointed by the king to put down Jack Cade’s rebellion. Interestingly, when Richard, Duke of York—whose son Lord Scales had stood godfather for in 1442—placed his grievances before the king that autumn, Lord Scales and Lord Rivers accompanied him.

Lord Scales, however, remained loyal to Henry VI during the upheavals of the 1450’s. In the summer of 1460, when the exiled Earls of March, Warwick, and Salisbury returned to England with the intention of seizing power, Lord Scales and Robert, Lord Hungerford, held the Tower for the king. Besieged by the Yorkists, the forces inside the Tower had cast wild fire and shot guns into the city, to the injury of “men and women and children in the streets,” as reported by the English Chronicle. When the Yorkists, having defeated the Lancastrians at Northampton, returned to London with Henry VI in their power, Scales and Hungerford surrendered on 19 July.

Uncertain how he would fare in the hands of the Londoners, Scales, accompanied by three others, found a boat late that evening and rowed toward Westminster, with the intention of taking sanctuary there. Tipped off by a woman who recognized Lord Scales, a group of boatmen surrounded him, murdered him, and dumped his naked body at St. Mary Overy at Southwark, where he lay for several hours before his godson the Earl of March (later Edward IV) came upon the scene and arranged a proper burial for him. It was, as the English Chronicle noted, a “great pity” that “so noble and worshipful a knight,” who had served so valiantly in France, should meet such an ignominious death.

Chroniclers seldom bothered to record the reactions of the wives and daughters of those slain during the Wars of the Roses, and they made no exception in the case of Elizabeth Scales. By this time, she was a widow, having been married previously to Henry Bourchier, the second son of the Earl of Essex by the same name. His death probably took place in August 1458. If any children were born to the couple, they did not survive.

Exactly when Elizabeth married Anthony Woodville is unknown, but contrary to what is sometimes claimed, it is beyond dispute that the marriage took place well before Anthony’s sister became the queen of England. The couple had certainly married before 4 April 1461, when William Paston reported mistakenly that that Anthony, Lord Scales—the title that Anthony took in right of Elizabeth—had been killed at the battle of Towton. Richard Beauchamp, Bishop of Salisbury, writing three days later, also reported that the dead included “Anthony, son of Lord le Ryver, who was recently made Lord le Scales.”

Earlier, following the Lancastrian victory at the second battle of St. Albans on 17 February 1461, the Londoners had included Jacquetta Woodville, Duchess of Buckingham, and Lady Scales in a delegation sent to Margaret of Anjou to beg for mercy for the city. Does “Lady Scales“ refer to Elizabeth or to her mother? Ismania had been prominent among Margaret’s ladies and would thus be a natural candidate for the task of negotiating with the queen, but it is not certain that she was still alive at this date; there is no indication that she held any lands in dower or jointure, as she would have if she had survived her husband. It may be, then, that “Lady Scales” refers to Elizabeth Scales and that she had joined Jacquetta, Anthony’s mother, in the negotiations.

Whether Anthony and Elizabeth’s parents helped bring the couple together, or whether the couple initiated their marriage on their own, is unknown. Elizabeth’s inheritance as Scales’ only child gave her an obvious attraction for Anthony, and his own status as the eldest son gave him an obvious attraction for Elizabeth, but there is nothing to indicate whether personal attraction played a role in the marriage as well. It is not certain how great the age difference between the pair was. Anthony was listed in his mother’s 1472 post-mortem inquisition as being “of the age of thirty years and more,” which would put his birth date at around 1442 (to Elizabeth’s probable birth date of 1437), but “the more” allows plenty of hedge room and leaves open the possibility that he was born earlier in his parents’ marriage, which took place by 23 March 1537.

Elizabeth’s inheritance included lands in Norfolk, Cambridgeshire, Hertfordshire, Essex, and Suffolk. The heart of the Scales estate was Middleton, near Bishop’s Lynn (later King’s Lynn). The town of Lynn often sent gifts of wine to Lord and Lady Scales, whose minstrels also appear in the records.

Lady Scales features in the records of John Howard, who later became the Duke of Norfolk. In September 1464, Howard rewarded her messenger for bringing him a letter from Elizabeth. While the king was at Reading in November, Howard lent Elizabeth, who was there with her husband, 8s 3d to play at cards. The party moved on to spend Christmas at Eltham with the king; there, on 1 January 1465, Howard gave 12d to “my lord Scales chyld.” Anne Crawford has pointed out that the “child” was probably a page who was bringing a New Year’s gift to Howard from Anthony and Elizabeth, as opposed to the offspring of either Lord or Lady Scales, although Anthony did have an illegitimate daughter.

Meanwhile, of course, Elizabeth Woodville, Anthony’s sister, had married Edward IV, the godson of Thomas, Lord Scales. Lady Scales was prominent among the attendants of her sister-in-law the queen. In 1466-67, like the queen’s sister Anne, who was married to William, Viscount Bourchier, Lady Scales received forty pounds per annum for her services (the same rate that her mother had received when serving Margaret of Anjou).

In 1466, Anthony and Elizabeth engaged in a series of complex legal maneuvers to ensure that if Elizabeth predeceased Anthony without having borne him a child, the Scales estates would stay in Anthony’s hands instead going to Elizabeth’s heirs. While this did have the effect of subverting the normal laws of inheritance, there is no reason to assume that Elizabeth would have preferred that the land go to her rather distant cousins instead of to her husband.

When Edward IV’s sister Margaret traveled to Burgundy to marry its duke, Charles, in July 1468, Anthony Woodville served as her presenter. Prominent among the English ladies accompanying Margaret to her wedding was Lady Scales. The marriage took place with all of the ceremonial splendour one could expect of the Burgundian court. It certainly overawed John Paston, who wrote in a letter home, “And as for the duke’s court, as of lords, ladies and gentlewomen, knights, squires and gentlemen, I have never of no like to it, save King Arthur’s court. And by my trowth, I have no wit nor remembrance to write to you, half the worship that is here.”

Anthony and Elizabeth’s return to England was soon followed by tragedy: in August 1469, Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, having rebelled against Edward IV and taken the king temporarily into his custody, ordered the executions of Anthony’s father, Earl Rivers, and of his younger brother John—executions that were entirely illegal, as both Earl Rivers and John had been supporting the king that Warwick himself still recognized as his ruler. Anthony and Elizabeth now had in common the fact that each had suffered the murder of a father.

The continuing political upheaval led to Edward IV fleeing England in the autumn of 1470. With him into exile went a number of loyal supporters, including Anthony. Where Lady Scales spent the next few months is unknown. She may have joined her mother-in-law, Jacquetta, and Queen Elizabeth in sanctuary at Westminster, but I know of no source placing her there.

After Edward scored a Yorkist victory at Barnet, he returned to London briefly before marching out to encounter Margaret of Anjou’s forces. Anthony Woodville and the Earl of Essex (Elizabeth Scales’ father-in-law from her first marriage) were left to defend London from an attack by the Bastard of Fauconberg. Queen Elizabeth and her children were lodged in the Tower for their safety; perhaps Elizabeth Scales was with them.

Edward IV was back on his throne in May 1471, but Elizabeth Scales had little time to enjoy the peace that followed. According to Anthony’s inquisitions post mortems, she died on September 2, 1473. Anthony married Mary FitzLewis in around 1480. He was executed on orders of the future Richard III at Pontefract on 25 June 1483.

In his will, written at Sheriff Hutton two days before his death, Anthony, having left the Scales lands to his brother Edward, asked that 500 marks be used for prayers for the souls of Lady Scales, her brother Thomas, and the souls of all of the Scales family. In an unsympathetic article about Anthony, Lynda Pidgeon states that in his will, Anthony “makes no affectionate mention of [Elizabeth] or desire to be buried beside her” and that he appeared to do only the bare minimum to provide for her soul and those of others. Pidgeon concludes, “The will was business like: it met the requirements of his soul and those of his family and little else. . . . Perhaps he simply did not have feelings for anyone else.” This judgment overlooks the fact that many if not most wills of the period are businesslike documents, without sentimental effusions; it also fails to consider that Anthony, unlike testators expecting to meet a natural death or preparing for the eventuality of dying honorably in battle, was under the enormous stress of facing execution for a crime he most likely did not commit. Moreover, as one who was about to be executed, he could expect his lands to be forfeit to the crown and would have to hope that arrangements would be made to pay his debts and to honor his bequests; he was hardly in a position to make extravagant provisions for the dead. As it was, it does not appear that his will was ever admitted to probate during Richard III’s reign.

Anthony, possibly anticipating that he would be brought south for the trial before his peers that was his right as an earl, initially asked in his will that if he died beyond the River Trent, he be buried in the chapel of the Lady of Pewe at Westminster. At the end of his will, having apparently learned by then that he would be executed at Pontefract, he asked that he be buried there before an image of the Virgin Mary with his nephew Richard Grey, who was also facing execution. Anthony’s failure to request burial beside his first wife (whose burial place is not known) need not show lack of affection for her; it may simply indicate a strong devotion to the Virgin that took precedent over earthly attachments. Moreover, as a condemned man he could not expect that the crown would go to the expense and trouble of bringing his body to lie beside that of Lady Scales, unless she happened to have been buried at a place that was convenient for her husband’s burial.

In 1485, following the defeat of Richard III at Bosworth, the heirs to the Scales lands were determined. One was Sir William Tyndale; the other was John de Vere, Earl of Oxford, a diehard Lancastrian who had been instrumental in bringing Henry VII to the throne.

Sources:

Helen Castor, ‘Scales, Thomas, seventh Baron Scales (1399?–1460)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article..., accessed 9 Sept 2012]

Complete Peerage

Anne Crawford, Yorkist Lord: John Howard, Duke of Norfolk, c. 1425-1485. London: Continuum, 2010.

Henry Harrod, Report on the Deeds and Records of the Borough of King’s Lynn. London: Simpkin, Marshall & Co., 1874.

Susan Higginbotham, The Woodvilles (manuscript in progress).

Historical Manuscripts Commission, The Manuscripts of the Corporations of Southampton and King’s Lynn. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1887.

Ian Lancashire, Dramatic Texts and Records of Britain: A Chronological Topography to 1558. Cambridge University Press, 1985.

Lynda Pidgeon, “Antony Wydevile, Lord Scales and Earl Rivers: Family, Friends, and Affinity.” Part 2. Ricardian, 2006.

A. R. Myers, Crown, Household and Parliament in Fifteenth Century England. London: Hambleton Press, 1985.

James Ross, John de Vere: Thirteenth Earl of Oxford 1442-1513. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2011.

The National Archives

September 3, 2012

Guest Post Alert: Eleanor Cobham

I just wanted to stop by and let you know that I have a guest post up over at Madame Guillotine’s blog. (Madame Guillotine has written The Secret Diary of a Princess, about the young Marie Antoinette, which I read a while back and thoroughly enjoyed. She also has a lot of fascinating posts on her blog, so stick around and explore!) My post is about Eleanor Cobham, one of several great ladies in fifteenth-century England to be accused of witchcraft.

August 30, 2012

Fifteen Aids to Grey

A couple of months ago, I did the following guest post on the lovely Sharon Kay Penman’s blog as part of my blog tour for Her Highness, the Traitor. Although I’ve come across a couple of blog posts and books that have reassured me that the following rules are being followed faithfully, it’s still important to be vigilant. So here is a reprise of my Rules for Writing About Lady Jane Grey. As you can never have too many rules in writing historical fiction, I’ve added several. They work perfectly fine for writing nonfiction too, incidentally, especially if you leave out those distractions known as citations.

A portrait of two people who aren’t Frances Grey and Adrian Stokes. This, of course, means that you should model Frances and Adrian on this portrait. Got it?

1. Frances Grey, Jane’s mother, must always be portrayed as grossly obese. The fact that the portrait that this depiction is based upon is not actually of Frances is entirely immaterial. Helpful Hint: Have Frances gnaw on a big turkey leg to underscore your point.

2. Jane Grey must be whipped by her parents at least twice in your novel: once before her wedding day and once before that as a warm-up whipping. The truly dedicated novelist will even allow the Greys to whip their daughter after she becomes queen, just to remind the reader who’s boss. (Be sure to dwell in loving detail on the welts caused by the lashing.)

3. Guildford Dudley can be either effeminate or brutish, depending on your preference. (The experienced novelist can make him both effeminate and brutish, but this isn’t recommended for beginners.) Whether you’ve made him effeminate or brutish, however, Guildford must behave like a sniveling weakling on his way to the scaffold. Bonus: If you ever write about the Wars of the Roses, Guildford’s character can be recycled for use as Edward of Lancaster’s. All you need to do is change the names and costumes.

4. Mary, Jane’s supposedly dwarfish sister, must be hidden away by her parents, who will refer to her at every convenient occasion in the novel as a freak or a monster, preferably to Mary’s face. Ignore the temptation to Google, which will bring you to records showing that Mary Grey accompanied her family on social visits, including one to Princess Mary. Google is your enemy here.

5. Adrian Stokes, Frances Grey’s second husband, must be half Frances’s age. The fact that there is a source showing his precise date of birth, making him only two years younger than Frances, must be studiously ignored. Don’t worry: ignoring the records about Mary Grey will have given you ample practice in doing this. Susan’s Special Tip: Have Frances sleep with Adrian during her marriage to Henry Grey, as well as with the odd stable boy or two. Susan’s Even More Special Tip: Have Henry Grey sleep with Adrian as well, as well as with the odd stable boy or two.

6. Speaking of Frances Grey, it is well known that Frances was the only person in Tudor England, or indeed in England before the twentieth century, to hunt for sport. If Frances isn’t committing Bambi-cide within ten pages of the opening of your novel, while Jane and the local chapter of PETA look on in horror, you need to do a rewrite.

7. While it is important to make Jane’s parents uncaring, brutal, and stupid, the novelist should not go overboard and make them downright evil, because true evilness must be held in reserve for the Duke of Northumberland. If the reader doesn’t come away thinking that “evil Northumberland” is a tautology, you have failed utterly as a writer and need to beg to have your day job back.

8. Edward VI must be sickly from birth; however, he must not die a natural death, but must be poisoned at the hands of Northumberland (who must be, remember, evil). Don’t forget to have Northumberland switch the king’s body with that of a murdered nobody; omitting this detail is the sort of carelessness that can trip up an unwary novelist.

9. Jane must be meek, mild, and terrified of her elders. Ignore the letter written by Jane to Thomas Harding in which she denounces the poor man as the “deformed imp of the devil” and the “stinking and filthy kennel of Satan.” Jane was probably just having a bad day.

10. Jane’s dreadful parents must be bitterly resentful of her scholarship and must attempt to drag her away from her books at every possible juncture. Disregard the fact that Jane’s father was a patron of scholars, and by all means don’t complicate things by making the reader wonder why, if Jane’s parents hated their daughter’s learning so much, they simply didn’t dismiss her tutors and confiscate her books and prevent her from corresponding with and receiving visits from scholars. Historical fiction should not be complicated.

11. The only happy period in Jane Grey’s life must be when she is living with Katherine Parr, who must also be made to single-handedly imbue Jane with a love for learning. (If you can make Thomas Seymour take a break from molesting the Lady Elizabeth long enough to have him menace Jane, the more the merrier–but don’t overdo it. Even Jane gets one happy period in her life, remember.)

12. Mary I can be allowed some strength of character just long enough to fight the (evil, don’t forget) Northumberland for her throne. Immediately afterward, however, she must turn into a pathetic, lovesick drip, who sends Jane to her death solely to guarantee her marriage to Philip of Spain. (Who can be evil too. But not as evil as Northumberland.)

13. Mrs. Ellen must be Jane’s childhood nurse, devoted to her charge through thick and thin. You say that no contemporary source actually describes Mrs. Ellen as Jane’s childhood nurse? Shut your mouth or Frances will come from her grave to give you some nips and bobs.

14. Jane must be portrayed as frail and delicate, not only because nice girls are frail and delicate, but because it gives Mrs. Ellen the opportunity to nurse her. See? I told you she was Jane’s old nurse.

15. Finally, the “P” words—“puppet” and “pawn”—are vital when writing about Jane Grey. Using just one is the mark of the amateur; the astute novelist will use them both. If you can use them both in the same sentence, why are you reading this list?

August 19, 2012

Jane Grey and Katherine Parr

Read about Katherine Parr or Jane Grey, and you’ll soon come across the statement, in various guises, that when Jane Grey came to live with Katherine Parr, Katherine gave Jane the maternal nurturing of which she had been deprived. It was then, the story usually goes on, that Jane first found acceptance of her intellectual gifts. Katherine Parr’s death, the story dolefully concludes, was therefore not only a tragedy for Katherine but for Jane, who was returned to her dreadful parents and consigned once again to a life of misery.

Read about Katherine Parr or Jane Grey, and you’ll soon come across the statement, in various guises, that when Jane Grey came to live with Katherine Parr, Katherine gave Jane the maternal nurturing of which she had been deprived. It was then, the story usually goes on, that Jane first found acceptance of her intellectual gifts. Katherine Parr’s death, the story dolefully concludes, was therefore not only a tragedy for Katherine but for Jane, who was returned to her dreadful parents and consigned once again to a life of misery.

As with so many aspects of Jane Grey’s story, fiction in this instance has heavily intruded upon fact.

First, as Leanda de Lisle has pointed out, the story that the nine-year-old Jane was part of Katherine Parr’s household in 1546 and was a witness to Katherine Parr’s famous confrontation with Henry VIII following Katherine’s learning of her imminent arrest is a product of Victorian confusion of “Lady Lane” with “Lady Jane.” The passage in question, as reported by John Foxe, places Lady Lane, not Lady Jane, at the scene: “And so first cōmaundyng her Ladyes to conuey away their bookes, which were agaynst the law, the next night folowyng after supper, shee (wayted upon only by the Lady Harbert her sister and the Lady Lane, who caried the candell before her) went vnto the kynges bead chamber, whom she found sittyng and talkyng with certeine Gentlemē of his chamber.” Nothing places Jane Grey in Katherine Parr’s court during Henry VIII’s reign, though her mother, Frances, was among the queen’s ladies and might have brought young Jane to visit at court from time to time. (When Frances’s widower, Adrian Stokes, died, a portrait of Katherine Parr was among his household furnishings. If this came from Frances, perhaps she herself had been fond of the queen.)

Second, it is often forgotten that Jane was not Katherine Parr’s ward: she was Thomas Seymour’s. According to the deposition of Jane’s father, Henry Grey, then Marquis of Dorset, Seymour approached him shortly after Henry VIII’s death to propose that Jane be put into his care so that Seymour could promote Jane’s marriage to the young Edward VI. Dorset, having agreed to Seymour’s proposal, sent for Jane, “who remained in [Seymour's] house from that time continually until the death of the Queen.” Susan James, one of Parr’s biographers, has suggested that Jane remained at Thomas’s house at Seymour Place even after Seymour’s marriage to Katherine Parr became public and that she did not join the queen’s household until after the Lady Elizabeth left it in May 1548. This may be the case; there is certainly no mention of Jane’s presence in the accounts of the sexually charged horseplay between Seymour and Elizabeth, and Jane never gave a deposition about the relations of Seymour and the princess when Seymour later fell from grace. On the other hand, it seems more likely that once Seymour and Katherine made their marriage public, Jane would have spent at least some time with the rest of the “family”–Seymour, Katherine, and the Lady Elizabeth–at Chelsea and Hanworth instead of remaining constantly at Seymour Place.

In early 1548, after Elizabeth’s tutor died, Elizabeth succeeded in getting Roger Ascham appointed as her new tutor. It may have been then that Jane made the acquaintance of Ascham, who would visit her at Bradgate several years later and record their meeting for posterity.

Sadly, while we know little of Jane’s relationship with Katherine during the queen’s life, we do know that Jane served as chief mourner at Katherine’s funeral: “Then, the Lady Jane, daughter to the lord Marquis [of] Dorset, chief mourner, led by a[n] estate, her train borne up by a young lady.” This may be a sign that Jane and Katherine had become close; on the other hand, it may simply be that Jane was chosen for the role because she was the highest-ranking lady available on relatively short notice.

There is one intriguing hint of a close relationship between Katherine and Jane, however: the prayer book that Jane carried to the scaffold. Janel Mueller, who has published a scholarly edition of Katherine’s writings, believes that the prayer book is in Katherine’s handwriting and that it was therefore created by the queen herself. Mueller posits that the prayer book was given as a keepsake by the queen to Jane, although if it was indeed Katherine Parr’s, it is also possible that Thomas Seymour, to whom Katherine left all of her goods, gave it to Jane.

It is certainly probable that the queen and Jane, both of whom enjoyed intellectual pursuits, found pleasure in each other’s company and that Jane admired and respected the queen. Probable–but not recorded. The bare facts above are all that is known about Jane’s relationship with Katherine Parr. The rest of the oft-told tale–that in Katherine’s care, Jane found happiness for the first time in her young life, that Katherine’s encouragement helped Jane to blossom as a scholar, that Katherine became a mother figure to Jane, that Jane was unhappy to return home–is romantic embroidery, perfectly reasonable in fiction but irritating when it intrudes itself into nonfiction.

Sources:

Eric Ives: Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Mystery

Susan James, Kateryn Parr: The Making of a Queen

Leanda de Lisle: The Sisters Who Would Be Queen

Janel Mueller, ed., Katherine Parr: Complete Works and Correspondence

Linda Porter: Katherine the Queen: The Remarkable Life of Katherine Parr

P. F. Tytler, England under the Reigns of Edward VI and Mary