Susan Higginbotham's Blog: History Refreshed by Susan HIgginbotham, page 17

June 23, 2012

The Tudor Cosmo Girl

I shared this on my Facebook page this morning, but I thought those of you who don’t “do” Facebook might enjoy it:

June 18, 2012

A Seer, A Prophet, or a Witch?: A Guest Post by Sandra Byrd

While I’m away from my blog doing my tour, I’m pleased to welcome Sandra Byrd as my guest poster! Sandra is the author of The Secret Keeper, a new novel about Juliana St. John, a young woman with the gift of prophecy who joins the court of Katherine Parr. I’ve downloaded The Secret Keeper to Mr. Kindle, and it looks great! Anyway, here’s Sandra!

While I’m away from my blog doing my tour, I’m pleased to welcome Sandra Byrd as my guest poster! Sandra is the author of The Secret Keeper, a new novel about Juliana St. John, a young woman with the gift of prophecy who joins the court of Katherine Parr. I’ve downloaded The Secret Keeper to Mr. Kindle, and it looks great! Anyway, here’s Sandra!

Six women in the Bible are expressly stated as possessing the title of prophetess: Miriam, Deborah, Huldah, Noahdiah and Isaiah’s wife. Philip is mentioned in Acts as having four daughters who prophesied which brings the number of known prophetesses to ten. There is no reason to believe that there weren’t thousands more, undocumented throughout history, then and now. According to religious tradition, women have often been powerful seers and that is why I’ve included them in my current novel: The Secret Keeper: A Novel of Kateryn Parr.

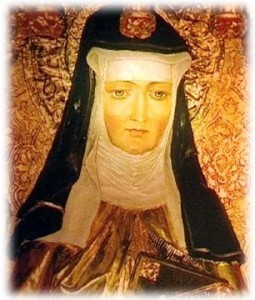

Hundreds of years before the renaissance, which would bring about improved education for women, Saint Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) wrote medicinal texts and composed music. She also oversaw the illumination of many manuscripts and wrote lengthy theological treatises. But what she is best known for, and was beatified for, were her visions.

Hildegard said that she first saw “The Shade of the Living Light” at the age of three, and by the age of five she began to understand that she was experiencing visions.[1] Although she was understandably reluctant to share her visions she continued to receive them, understanding them to be from God and, in her forties, was instructed by Him to write them down. She said, ” I set my hand to the writing. While I was doing it, I sensed, as I mentioned before, the deep profundity of scriptural exposition… I spoke and wrote these things not by the invention of my heart or that of any other person, but as by the secret mysteries of God I heard and received them in the heavenly places. And again I heard a voice from Heaven saying to me, ‘Cry out therefore, and write thus!”[2]

Spiritual gifting is not given for the edification of the person receiving it, but for the church at large. Hildegard wrote three volumes of her mystical visions, and then exegeted them biblically herself. Her theology was not, as one might expect, shunned by the church establishment of the time, but instead Pope Eugenius III gave her work his approval and she was published in Paris in 1513.

Spiritual gifting is not given for the edification of the person receiving it, but for the church at large. Hildegard wrote three volumes of her mystical visions, and then exegeted them biblically herself. Her theology was not, as one might expect, shunned by the church establishment of the time, but instead Pope Eugenius III gave her work his approval and she was published in Paris in 1513.

Several centuries later, Julian of Norwich continued Hildegard’s tradition as a seer, a mystic, and a writer. In her early thirties, Julian had a series of visions which she claimed came from Jesus Christ. In them, she felt His deep love and had a desire to transmit that He desired to be known as a God of joy and compassion and not duty and judgment. Her book, Revelations of Divine Love, is said to be the first book written in the English language by a woman.[3] She was well known as a mystic and a spiritual director by both men and women. The message of love and joy that she delivered is still celebrated today; she has feast days in the Roman Catholic, Anglican, and Lutheran traditions.

It had been for good cause that Hildegard and Julian kept their visions to themselves for a time. Visions were not widely accepted by society as a whole, and women in particular were often accused of witchcraft. This risk was perhaps an even stronger danger in sixteenth and seventeenth century England when “witch hunts” were common. While there is no doubt that there was a real and legitimate practice of witchcraft occurring in some places, the fear of it whipped up suspicion where no actual witchcraft was found. Henry the VIII, after imprisoning Anne Boleyn, proclaimed to his illegitimate son, among others, that they were all lucky to have escaped Anne’s witchcraft. The evidence? So obviously bewitching him away from his “good” judgment.

It had been for good cause that Hildegard and Julian kept their visions to themselves for a time. Visions were not widely accepted by society as a whole, and women in particular were often accused of witchcraft. This risk was perhaps an even stronger danger in sixteenth and seventeenth century England when “witch hunts” were common. While there is no doubt that there was a real and legitimate practice of witchcraft occurring in some places, the fear of it whipped up suspicion where no actual witchcraft was found. Henry the VIII, after imprisoning Anne Boleyn, proclaimed to his illegitimate son, among others, that they were all lucky to have escaped Anne’s witchcraft. The evidence? So obviously bewitching him away from his “good” judgment.

In that century, the smallest sign, imagined or not, could be used to indict a “witch”. A gift handling herbs? Witchcraft. An unrestrained tongue? Witchcraft. Floating rather than sinking when placed in a body of water when accused of witchcraft and therefore tested? Guilty for sure. Women with “suspicious” spiritual gifts, including dreams and visions, had to be particularly careful. And yet they, like Hildegard and Julian before them, had been given just such a gift to share with others. And share they must.

One women in the court of Queen Kateryn Parr is strongly believed to have had a gift of prophecy. Her name was Anne Calthorpe, the Countess of Sussex. One source possibly hinting at such a gift can be found at Kathy Emerson’s terrific webpage of Tudor women:[4] Emerson says that Calthorpe, “was at court when Katherine Parr was queen and shared her evangelical beliefs. Along with other ladies at court, she was implicated in the heresy of Anne Askew. In 1549 she was examined by a commission “for errors in scripture” and that “the Privy Council imprisoned two men, Hartlepoole and Clarke, for “lewd prophesies and other slanderous matters” touching the king and the council. Hartlepoole’s wife and the countess of Sussex were jailed as “a lesson to beware of sorcery.”

According to religious tradition women have often had very active prophetic gifts; we are mystical, engaging, and intuitive. I admire our sisters throughout history who actively, risk-takingly, used their intellectual and spiritual gifts with whatever power they had at hand.

[1] Bennett, Judith M. and Hollister, Warren C. Medieval Europe: A Short History (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001), 317.

[2] Hildegard von Bingen, Scivias, trans. by Columba Hart and Jane Bishop with an Introduction by Barbara J. Newman, and Preface by Caroline Walker Bynum (New York: Paulist Press, 1990) 60–61.

[3] http://www.julianofnorwich.org/vision...

[4] http://www.kateemersonhistoricals.com...

May 27, 2012

Anne Boleyn and the Charge of Witchcraft: A Guest Post by Claire Ridgway

As I mentioned a couple of days ago, I’m delighted to welcome Claire Ridgway to my blog! Claire’s new nonfiction book, The Fall of Anne Boleyn: A Countdown is a concise day-by-day look at the events leading up to the execution of Henry VIII’s most famous queen.

Claire is also offering a surprise to one lucky person who comments here before before midnight on May 30, US Eastern Standard time: an Anne Boleyn wine stopper! And as a bonus, I’ll throw in a copy of Her Highness, the Traitor (in which Anne Boleyn makes a cameo appearance to give some helpful advice to one of the heroines).

So without further ado, here’s Ms. Ridgway to point out that sometimes, a hare is just a hare.

In the lead-up to the anniversary of Anne Boleyn’s execution on the 19th May, I noticed lots of Tweets and Facebook comments referring to Anne Boleyn being charged with witchcraft, in addition to treason, adultery and incest. I bit my tongue and sat on my hands, resisting the urge to point out the glaring error in these posts. Then, as I was sitting there itching to reply, I saw Hilary Mantel’s article in The Guardian newspaper. Its title: “Anne Boleyn: witch, bitch, temptress, feminist” – face palm!

Now, Mantel was not actually suggesting that Anne was a witch or that she had been charged with witchcraft. In fact, Mantel writes, “Anne was not charged with witchcraft, as some people believe. She was charged with treasonable conspiracy to procure the king’s death, a charge supported by details of adultery”, and she is correct, Anne was not charged with witchcraft. But, Anne Boleyn’s name is too often linked with witchcraft and many people, even Tudor history buffs, assume that she was charged with it. It’s no wonder that people make that assumption when Anne’s portrait is on the wall at Hogwarts (not to be taken seriously though), the 2009 Hampton Court Palace Flower Show had a Witch’s Garden to represent Anne Boleyn and The Other Boleyn Girl depicted Anne Boleyn dabbling in witchcraft, taking a potion to bring on the miscarriage of a baby (which turns out to be monstrously deformed) and having a “witch taker” help to bring her down. You only have to google “Anne Boleyn witchcraft” to find sites claiming that Anne was charged with witchcraft and executed for witchcraft, or mentions of her having an extra finger and moles all over her body, which could have been seen as “witch’s teats” and the marks of a witch. Even an article on the BBC site refers to her being accused of being “a disciple of witchcraft”.

Some non-fiction authors and historians give credence to the witchcraft theory. In her biography of Anne Boleyn, Norah Lofts writes of Anne bearing a mole known as the ‘Devil’s Pawmark” and making a “typical witch’s threat” when she was in the Tower, claiming that there would be no rain in England for seven years. Lofts explains that seven was the magic number and that witch’s were thought to control the weather. What’s more, Anne had a dog named Urian, one of Satan’s names, and she managed to cast a spell on Henry which eventually ran out in 1536, hence his violent reaction, “the passing from adoration to hatred”. Lofts goes even further when she writes about the story of Anne haunting Salle Church in Norfolk, where, according to legend, Anne’s body was really buried. Loft writes of meeting the sexton of the church who told her of how he kept vigil one year on 19th May to see if Anne’s ghost appeared. He didn’t see a ghost, but he did see a huge hare “which seemed to come from nowhere”. It jumped around the church before vanishing into thin air. According to Lofts “a hare was one of the shapes that a witch was supposed to be able to take at will” and she pondered if it was indeed Anne Boleyn.

That all sounds rather far-fetched, but reputable historian Retha Warnicke also mentions witchcraft in her book on Anne, writing that sodomy and incest were associated with witchcraft. Warnicke believes that the men executed for adultery with Anne were “libertines” who practised buggery and, of course, Anne and George were charged with incest. Warnicke also thinks that the rather lurid mentions in the indictments of Anne procuring the men and inciting them to have sexual relations with her was “consistent with the need to prove that she was a witch”. She continues, saying that “the licentious charges against the queen, even if the rumours of her attempted poisonings and of her causing her husband’s impotence were never introduced into any of the trials, indicate that Henry believed that she was a witch.” Now, Henry VIII may well have said “ that he had been seduced and forced into this second marriage by means of sortileges and charms”, but I don’t for one second believe that Henry was convinced that Anne was a witch. If he had believed it, then surely Cromwell would have used it to get Henry’s marriage to Anne annulled. If Anne was a witch then it could be said that Henry had been bewitched and tricked into the marriage, that the marriage was, therefore, invalid. Anne Boleyn was charged with adultery, plotting the King’s death and committing incest with her brother, George Boleyn, Lord Rochford. There was no mention or suggestion of witchcraft or sorcery in the Middlesex or Kent indictments and at her trial, Anne was found guilty of committing treason against the King – again, no mention of witchcraft. Although witchcraft was not a felony or a crime punishable by death until the act of 1542, a suggestion of witchcraft could still have helped the Crown’s case and served as propaganda. I believe that the details of the indictments were simply there for shock value, rather than to prove that Anne was a witch.

So, where does the whole witchcraft charge come from if it was not mentioned in 1536? Well, I think we can put some of the blame on the Catholic recusant Nicholas Sander, who wrote “Rise and Growth of the Anglican Schism” in 1585, while in exile during the reign of Elizabeth I, Anne Boleyn’s daughter. In his book, Sander describes Anne Boleyn as having “a projecting tooth”, six fingers on her right hand and “a large wen under her chin” – very witch-like! He also writes that Anne miscarried “a shapeless mass of flesh” in January 1536. This “shapeless mass” was turned into “a monster”, “a baby horridly malformed, with a spine flayed open and a huge head, twice as large as the spindly little body”, by historical fiction writer Philippa Gregory and was used to back up the idea that Anne had committed incest and dabbled in witchcraft. However, Sander’s words have to be judged as Catholic propaganda, as an attempt to denigrate Elizabeth I by blackening the name of her mother. Sander was only about six years of age when Anne died, so he could hardly have known her, and he was a priest, not a courtier, so would not have heard court gossip about Anne. None of Anne’s contemporaries mention an extra finger, projecting tooth or wen, and even Anne’s enemy, Eustace Chapuys, describes her miscarriage as the loss of “a male child which she had not borne 3½ months”. He would surely have mentioned it being deformed, if it was, and I’m sure that Chapuys would also have mentioned any physical deformities that Anne possessed. He nicknamed her “the concubine” and “the putain”, or whore, so he wasn’t afraid of saying what he thought!

While I cannot prove that Anne Boleyn was a witch, I can cast doubt on this belief. Norah Lofts’ claims can easily be refuted. Anne’s mole was simply a mole, her dog was named after Urian Brereton (brother of William Brereton, who gave the dog to Anne), Anne’s mention of the weather in the Tower was simply the ramblings of a terrified and hysterical woman, and the hare was simply a hare! As for Retha Warnicke’s views, I have found no evidence to prove that the men executed in May 1536 were homosexual and the only evidence for the deformed foetus is Nicholas Sander. Also Henry’s words concerning “sortileges and charm” were more likely to have been bluster, rather than a serious accusation. He also said that Anne had had over 100 lovers and that she had tried to poison his son, Fitzroy, and his daughter, Mary. The bluster of an angry and defensive man, I believe, and not something to take seriously.

In conclusion, witchcraft was not something that was linked to Anne Boleyn in the sixteenth century, so I feel that it is about time that people stopped talking about Anne and witchcraft in the same breath. Let’s get the facts straight.

Sources:

Richard Bevan, Anne Boleyn and the Downfall of her Family, BBC History website – http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/tudors/anne_boleyn_01.shtml

Calendar of State Papers, Spain, Volume 5, Part 2: 1536-1538, note 59

Philippa Gregory, The Other Boleyn Girl, Harper, 2007

Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 10: January-June 1536, note 284

Norah Lofts, Anne Boleyn, Orbis Publishing, 1979

Hilary Mantel, Anne Boleyn: witch, bitch, temptress, feminist, The Guardian, 11 May 2012

Nicholas Sander, Rise and Growth of the Anglican Schism, 1585

Retha Warnicke, The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn, Cambridge University Press, 1989

May 25, 2012

The Duchesses Go on Tour, and the Queen Pays a Visit

A week from today, Her Highness, the Traitor, my novel about Frances Grey, Duchess of Suffolk, and Jane Dudley, Duchess of Northumberland, will go on sale here in the United States (June 29 in the UK), and I’m excited! Beginning on June 1, the publication date, I’ll be going on a blog tour. You can find the schedule here. It’s subject to changes and additions, of course, but I’ll keep it up to date.

A week from today, Her Highness, the Traitor, my novel about Frances Grey, Duchess of Suffolk, and Jane Dudley, Duchess of Northumberland, will go on sale here in the United States (June 29 in the UK), and I’m excited! Beginning on June 1, the publication date, I’ll be going on a blog tour. You can find the schedule here. It’s subject to changes and additions, of course, but I’ll keep it up to date.

I also wanted to mention that Claire Ridgway, who has an excellent blog on the much-maligned Anne Boleyn, is also doing her own blog tour for her new nonfiction book, The Fall of Anne Boleyn. She’ll be kicking off the tour with a visit here on Monday, May 28! I’ve had a chance to preview her post, and you’ll enjoy it thoroughly. Claire is offering a special surprise, so be sure to stop by!

May 22, 2012

A Triple Wedding at Durham Place: May 1553

Henry Hastings, Earl of Huntingdon

On May 25, 1553–not May 21, as is often reported–a triple wedding took place at Durham Place, the Duke of Northumberland’s London house. The couples were Guildford Dudley and Jane Grey, Henry Herbert and Katherine Grey, and Henry Hastings and Katherine Dudley. (Note the profusion of Henrys and Katherines and pause for a moment of sympathy for the historical novelist.) Guildford was the son of the Duke of Northumberland, John Dudley; Jane was the daughter of Henry Grey, Duke of Suffolk. Henry Herbert was the heir of William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke; Katherine was the Duke of Suffolk’s second daughter. Henry Hastings was the heir of Francis Hastings, the Earl of Huntingdon; Katherine Dudley was Northumberland’s youngest surviving daughter.

The wedding preparations had been underway since at least April 24, 1553, when the master of the king’s wardrobe was ordered to provide parcels of tissues and cloth of gold and silver to the couples, as well as to Frances, Duchess of Suffolk (Jane and Katherine Grey’s mother) and to Jane, Duchess of Northumberland (Guildford and Katherine Dudley’s mother). Also on the list was Elizabeth Parr (née Brooke), the Marchioness of Northampton. Her husband, William Parr, the Marquess of Northampton, was the brother of the late queen, Katherine Parr. As Eric Ives has pointed out, William Cecil credited the marchioness with promoting the match between Guildford and Jane, and her presence on the list of those receiving apparel suggests that Cecil was correct.

In the eerie sort of recycling that was typical of the era, much of the apparel came from the forfeited goods of Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, who had been executed in 1551, and his widow Anne, Duchess of Somerset, who was a prisoner in the Tower. A few months later, when Mary I took the throne, the Duchess of Somerset would be among those allowed to pick from Northumberland’s own forfeited goods.

With the couples properly dressed, the next step was the entertainment. This Northumberland provided for on May 20, 1553, when he wrote a letter to Sir Thomas Cawarden, Master of the Revels. Northumberland asked Cawarden to arrange two masques, one of men and one of women, for the wedding, which was to take place “Thursday next,” i.e., May 25, 1553. With his usual attention to detail, the duke specified that the costumes be “rich” and “seldom used.”

Edward VI, who was seriously ill, did not attend the wedding, nor is there any indication that his sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, were present. The imperial ambassador, Jehan Scheyfve, who described the nuptials as being celebrated with “great magnificence and feasting,” wrote that René de Laval de Boisdauphin, the outgoing French ambassador, was present on both days of the two-day festivities. Claude de L’Aubespine, secretary to the French king, was present on the second day, as was the Venetian ambassador. Giovanni Commendone wrote that the guests included “large number of the common people and the most principal of the Realm.”

Stephen Perlin, a Frenchman, was visiting England at the time of the wedding and later recalled his travels there. (Patriotically, he praised London as “one of the most beautiful, largest and richest places in the whole world”—”after Paris.”) Describing the wedding between the children of the Dukes of Northumberland and Suffolk as a “great festival,” he added with the benefit of several years’ hindsight, “Who would have thought that fortune would have turned her robe, and exercised her fury upon these two great lords?”

The members of the wedding party were indeed the victims of fortune’s fury. In a few months, the absent king and the Duke of Northumberland would be dead; by the following year, the Duke of Suffolk, Jane Grey, and Guildford Dudley would follow them to the grave. The marriage of Henry Herbert and Katherine Grey would be hastily annulled, and the match-making Marchioness of Northampton would be deprived of a husband by the government of Mary I, which forced the Marquess of Northampton to return to his previous wife, Anne Bouchier, whom he had divorced. (William Parr would be allowed to return to Elizabeth Brooke during Elizabeth I’s reign.)

One of the three couples who wed on May 25, however, kept both their heads and their marriage: Henry Hastings and Katherine Dudley. Though Katherine Dudley, who was probably still a child when she married Henry Hastings, was worthless as a bride after her father was executed on August 22, 1553, the Hastings family seems to have made no attempt to dissolve the marriage. Hastings succeeded to his father’s earldom in 1560. He and his countess, Katherine, were childless, but took charge of a number of young people during their forty-two-year marriage, which ended only with the earl’s death in 1595. Queen Elizabeth herself went to the bereaved countess to comfort her, but Katherine’s grief was such that one observer wrote that “my lady continueth in such sorrow and heaviness as greater cannot be in any creature living, certainly it is such that except the Lord in short time work some alteration, I fear it will endanger her life.” Evidently the Lord did work an alteration, for Katherine lived another twenty-five years, dying in James I’s reign in 1620.

Sources:

Calendar of State Papers, Spanish.

Claire Cross, The Puritan Earl. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1966.

Francis Grose et al., The Antiquarian Repertory, Vol. IV. London: Edward Jeffery, 1809.

Eric Ives, Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Mystery. Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

Diarmaid Macculloch, ed. and trans., The Vita Mariae Angliae Reginae of Robert Wingfield of Brantham. Camden Miscellany, Camden Fourth Series, Vol. 29, 1984.

C. V. Malfatti, trans. and pub., The Accession, Coronation, and Marriage of Mary Tudor as Related in Four Manuscripts of the Escorial. Barcelona, 1956.

May 5, 2012

The Fortunate Sir Richard Page

On May 8, 1536, Sir Richard Page had arguably the worst day of his life: he found himself a prisoner in the Tower, caught up in the flurry of arrests that would end in the deaths of Anne Boleyn, her brother, and four other men. Page, along with his fellow arrestee Thomas Wyatt, would emerge from the Tower with head intact. Who was the mysterious Sir Richard, the man who served Henry VIII and both his sons and who came so close to losing his life in 1536?

Page’s parentage is unknown. He had a sister, Margaret Page, whose married name was Margaret Smart, and cousins named John Carleton and Anthony Sondes. Page also refers in a letter to William Fitzwilliam, whose father had been a merchant tailor and the sheriff of London, and his wife, Anne, the daughter of Richard Sapcote of Elton, Huntingdonshire, as his nephew and his niece, but it is not clear which spouse was Page’s blood relation. In the 1520’s, he worked his way up through the ranks of royal servants, serving as Vice Chamberlain to Henry VIII’s natural son, Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond, whose arms he was tasked with devising.

Page sat on commissions of the peace in Middlesex and Surrey in 1526. In July 1528, he wrote to Cardinal Wolsey to report on the difficulties of Sir Thomas Cheyny, who was evidently embroiled in a dispute: the king had decreed that Cheyny “shall never come into the Chamber until he has confessed his fault and agreed with Mr. Russell; for he will have no grudge amongst his gentlemen.”

In April 1529, as a gentleman of the privy chamber, Page received an annuity of a hundred pounds. That same year, he was knighted “at the Parliament time.” On December 3, 1530, as a knight of the body, Page received a grant of the site of the late priory of St. Leonard, Thoby, Essex, and the manors of Thoby and Bluntzwall, Essex, once the property of the dead and attainted Cardinal Wolsey.

It was the hapless Wolsey who gives us Page’s first association with Anne Boleyn. On May 17, 1530, Thomas Cromwell wrote to Wolsey, “”Mr. Page received your letter directed unto my lady Anne, and delivered the same. There is yet no answer. She gave kind words, but will not promise to speak to the King for you.”

It was likely sometime around this period that Page married. His bride was Elizabeth Bourchier, who had three previous marriages to Henry Beaumont, a husband known only as Verney, and Edward Stanhope. By her last two marriages she had had a daughter each: Katheryn Verney and Anne Stanhope. In 1557, when Elizabeth died, she was survived by her daughter by Page, Elizabeth Skipwith, who was aged 30 or more.

Though we know little of Richard himself, his access to the powerful meant that he wrote to intercede on behalf of other people, such as his letter on behalf of his unfortunate niece:

23 Sept. 1534 1180. Sir Ric. Page to Cromwell.

Whereas you promised me at Langley to be good to my nephew Fitzwilliam concerning the misordering of his wife and other gentlewomen by the butcher of Hoddesdon if it be proved that he struck her, it will be duly proved by Mr. Cook, my nephew Fitzwilliam and Mr. Ogle. The butcher did not only strike my niece, but beat her with his fist, so that she fell in a swoon, and he rudely handled Mrs. Cook and other gentlewomen. If you are too busy to attend to this, be good master to their husbands when it is brought into the Star Chamber or elsewhere. As they are his tenants, my lord of Essex will do what he can to stop the punishment. Woodstock, 23 September.

You have honored ladies and gentlewomen too much to see them take shame by a villain.

[The story behind this letter requires a blog post in itself, and will duly receive one.]

Several of Page’s letters figure in the Lisle correspondence. On October 15, 1533, he wrote to Honor Lisle, the wife of Arthur Plantagenet, Lord Lisle (the illegitimate son of Edward IV) on behalf of Thomas Stockwhite, who had fallen into debt. Writing from the royal palace of Greenwich, Page explained, “The poor man dwelleth by me and hath a house full of children, and if he be troubled all they are like to fare much the worse or perish.” He added, “Here is no news but that the King’s Highness and the Queen’s Grace are merry.” (Anne Boleyn, now queen, had recently given birth to the future Elizabeth I.)

On June 13, 1535, Page enlisted Lord Lisle’s help in trying to collect two debts: a fifteen-year-old debt from Lord Edmund Howard, whose daughter Katherine would be Henry VIII’s fifth queen, and one from Francis Hastings. Page hoped that Lord Lisle could “take some order with him” for the debt from Howard, and thought that if “your lordship will be somewhat round with” Hastings, he would soon pay up.

Lord Lisle himself wrote to Page on April 22, 1536, asking Page to be his ally in a matter involving the “Spear rooms” at Lisle’s disposal at Calais. Page, however, would soon be in no case to answer him. According to the lost journal of Antony Antony, notations from which were preserved by Thomas Tourneur, on May 8, 1536, Page was imprisoned in the Tower, where Anne Boleyn, accused of adultery, had gone as a captive a few days before.

Neither Page nor Thomas Wyatt, who was also arrested, was ever charged with a crime, and what entangled Page in this royal scandal remains a mystery. On May 12, 1536, John Husee wrote to Lord Lisle that Henry Norris, Francis Weston, William Brereton, and Mark Smeaton had been arraigned and condemned to die. He added, “Mr. Page and Mr. Wyatt are in the Tower, but as it is said, without danger of death: but Mr. Page is banished the King’s presence and Court for ever.” The next day, however, Husee was less certain. He reported that a “Harry Webbe” might be arrested in the West County and noted “some other say that Wyat and Mr. Page are as like to suffer as the others.” On May 19, 1536, having reported the executions of Anne and the rest, he wrote, “And touching Mr. Page and Mr. Wyat, they remain still in the Tower. What shall become of them, God knoweth best.”

By July 18, 1536, however, Page was a free man. That day, he wrote to Lady Lisle:

Good Madam, I most heartily that you for your kind remembrance, which is to me as welcome as anything can be; and do ascertain you that I am long ago at liberty and the King my good and gracious lord, but hitherto I have not greatly essayed to be a daily courtier again. And the King being so much my good lord as to give me liberty, I am more meet for the country than the Court. And to such a poor cabin as I have there, there is no lady nor gentlewoman in England shall be more welcome than ye shall be; beseeching you, if your chance be to come into these parts, ye will so take it, and me too. For yours shal I be, with all the service that may lie in my possible power. And pray your good ladyship to make my hearty recommendations unto my good lord your husband.

From London, this xviiith day of July.

by yours most bouwnden,

R. Page

Just as we don’t know what brought Page to the Tower, we don’t know what he or his friends did to clear his name. The fact that he was able to clear his name, though, raises an interesting question: Was there a genuine belief that Anne and her circle were guilty? As G. W. Bernard has pointed out, the fact that Page and Wyatt were released without having been charged suggests there was a good-faith investigation and that guilt was not necessarily a foregone conclusion. Furthermore, if the charges against Anne and her circle were trumped up and the Seymours were among the clique attempting to destroy these people, as some have claimed, Page was an unlikely victim. His stepdaughter, Anne Stanhope, had married Edward Seymour by 1535 and had been chaperoning Jane Seymour when she received visits from Henry VIII. It has been suggested that it was the Seymour connection that saved Page from execution, but in light of this connection, why imprison him in the first place unless there was a genuine suspicion that he was guilty? This is not to say that Page, Anne Boleyn, or any of the rest were actually guilty, but it may be that Henry VIII and/or Thomas Cromwell thought that they were and proceeded accordingly.

Wisely for him but sadly for us, Page seems to have maintained a judicious silence about the events of 1536. His discretion served him well, for by November 1536 he had been made sheriff of Surrey and Sussex. By June 1537, he was entertaining the Lady Mary (the future Mary I) at his home, where the king’s sackbut played and was rewarded by Mary. That same month, Lady Page sent cream and strawberries to the Lady Mary, who must have enjoyed them, for Page sent more strawberries to her later that month. In 1544, he was appointed as chamberlain at Hampton Court for Prince Edward. When Prince Edward became king, Page was appointed as one of his governors while Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, Lord Protector over the young Edward VI, went to Scotland in 1547. Page’s appointment was resented by Thomas Seymour, Edward VI’s other uncle, who was later quoted as saying that he disliked “the protector not appointing him to have governance of the king before so drunken a soul as Sir Richard Page.” No evidence corroborates Thomas Seymour’s description of Richard Page as a drunkard, and it seems rather unlikely that Henry VIII would have entrusted Prince Edward to the care of such a man.

Page, however, was not destined to serve Edward VI long, for he died in February 1548. In his will, dated September 22, 1547, he asked that he be buried at either the church of St. Mary on the hill besides Bishopgate in London, of which he was a patron, or at the parish church of Flamstede, where he had a manor. Most of his bequests went to his widow and to his daughter Elizabeth Skipwith: their gifts included a hundred pounds in old angels. Page had several granddaughters by Elizabeth Skipwith, two of whom were named Mabel and Frances. He gave his stepdaughter Katheryn Verney twenty pounds toward her marriage. Page left nothing to his other stepdaughter, Anne Seymour, but Anne, now the Duchess of Somerset, hardly needed anything. To the Protector himself Page gave a silver and gilt cup enameled after the antique fashion, with five lions standing upon castles to bear up the foot.

Somerset was executed in 1551, along with Lady Page’s stepson Michael Stanhope. Richard Page’s stepdaughter, Anne, was imprisoned in the Tower and remained there until Queen Mary’s reign. Had Richard Page not died when he did, he might well have been caught up in the events that led to Somerset’s imprisonment and execution. As it was, he died in his bed—once again, a lucky man.

Sources:

Will of Richard Page, PROB 11/34

G. W. Bernard, Anne Boleyn, Fatal Attractions. Yale University Press, 2010

Catharine Davies, ‘Page, Sir Richard (d. 1548)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article..., accessed 5 May 2012]

Matthew Davies, ‘Fitzwilliam, Sir William (1460?–1534)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Sept 2010 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article..., accessed 5 May 2012]

Muriel St. Clare Bryne, ed., The Lisle Letters. University of Chicago Press, 1981.

Eric Ives, The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn. Blackwell Publishing, 2005.

C. S. Knighton, ed., Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series of the Reign of Edward VI, 1547-1553, Preserved in the Public Record Office. London: HMSO, 1992.

Letters and Papers of Henry VIII

Mary Ann Lyons, ‘Fitzwilliam, Sir William (1526–1599)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article..., accessed 5 May 2012]

Frederick Madden, ed., Privy Purse Expenses of the Princess Mary. London: William Pickering, 1831.

George William Marshall, ed., The Visitations of the County of Nottingham in the years 1569 and 1614. London, 1871.

Beverley A. Murphy. Bastard Prince: Henry VIII’s Lost Son. Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2001.

John Gough Nichols, Literary Remains of King Edward the Sixth. Part I. London: J. B. Nichols and Sons, 1857.

‘Parishes: Flamstead’, A History of the County of Hertford: volume 2 (1908), pp. 193-201. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/repo... Date accessed: 05 May 2012.

State Papers, Henry VIII, Vol. I, Parts 1 and 2, 1831.

J. A. Tregelles, A History of Hoddesdon in the County of Hertfordshire. Hertford: Stephen Austin & Sons, Limited, 1908.

April 30, 2012

Search Terms and a Little Back-Patting

Hi! I’m working on a substantive post, so stay tuned for it, but in the meantime, I thought I’d post some search terms. I also wanted to mention that my new novel, Her Highness, the Traitor, will be published on June 1 and that I’ll be doing a blog tour. I’ll post the schedule here.

I was also thrilled to see the results of this survey of historical fiction readers. I’m in some august company!

Without further ado, here are some search terms for you:

anne boleyn barbie doll

Mattel tried to make a prototype, but the sixth finger kept breaking off, and the neck knob was too small.

profiles and cecily woodville telephone number

Silly, everyone knows that the Woodvilles had unlisted telephone numbers.

what group might henry vii be apart of on facebook ?

Henry VII didn’t have much use for Facebook. He preferred Twitter.

was queen elizabeth nice to margaret beaufort

No. She wouldn’t let her “friend” her on Facebook.

margaret of anjou what was she scared of

Menopause.

corpse of unsuitable friend

Mother always told me to choose my corpses wisely.

how was the medieval divorce

OK. Could have used a little more litigation.

pictures of jane shore

Rumor has it that these were found underneath Richard III’s mattress following the Battle of Bosworth.

history of Robitussin

If that’s not a blockbuster in the making, I don’t know what is.

April 18, 2012

It’s a Boy! No, It’s a Girl! Some Seymour Birth Dates

While looking for something else this morning, I made the mistake of looking in the Lisle letters and got completely sidetracked by the question of the birthdates of the older children of Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, and his second wife, Anne Stanhope. Since this has blown a good part of the day, I thought I would at least get a blog post out of it.

According to eminently respectable sources, including the Complete Peerage, Edward Seymour, then Lord Beauchamp, and Anne had a son who was born shortly before February 22, 1537, his baptismal date. Other less reputable sources claim that the son was born on October 12, 1537 (the same day Jane Seymour bore Henry VIII his son). Which of these dates is correct?

Neither, it appears.

As a letter from John Husee to Lady Lisle shows, there was indeed a Seymour child baptized on February 22, 1537—but the baby was a girl. The tip-off is the identity of her godparents: Jane Seymour, the Lady Mary (that is, Princess Mary, Henry VIII’s daughter), and the Lord Privy Seal. Children had three godparents: two of their own gender and one of the other. The baby’s gender is further confirmed by Mary’s privy purse expenses, which indicate that the princess gave Lady Beauchamp’s nurse 20 shillings at the christening in February. This entry does not give the child’s gender, but a subsequent entry, in November 1537, records that one of Anne’s servants brought one of her daughters to see Mary, “my lady being godmother to the same.” (Note the “one of” her daughters; this becomes important later.)

Anne Seymour had not been yet been churched as of March 11, 1537 (Lady Lisle was waiting for some goods which could not be sent until the churching took place). Mary traveled back and forth to visit Anne Seymour in March 1537, probably to the churching, as she gave Anne’s nurse another ten shillings on that occasion. As Anne would not have been allowed to resume sexual relations with her husband until the churching, which probably took place shortly after March 11, any child born to her in October 1537 would have been seriously premature. It appears likely, however, that no child was born to the Seymours in October 1537, because in fact their next child was born in March 1538. Most likely, the October 1537 birth date arises from confusion with that of Edward VI.

On March 20, 1538, Henry VIII’s accounts mention a warrant given to a goldsmith for “a certain cup given at the christening of the earl of Hertford’s son.” (Edward Seymour had been made Earl of Hertford after Edward VI’s birth in October 1537.) That a child was born to the Seymours this spring is confirmed by Lady Mary’s privy purse expenses, which show that in April 1538, she reimbursed Lady Kingston for money laid out at two christenings she had attended: one for the Countess of Sussex (Mary Arundell) and one for the Countess of Hertford. The sum—a combined total of seventy shillings for both countesses—is more generous than that given out at the February 1537 christening, even when divided into half to account for the Countess of Sussex’s child. This again suggests that Mary’s latest Seymour godchild was a boy, since boys usually inspired more generous gifts than girls.

A draper’s bill for July 17, 1538, mentions “my Lord, my Lady, my young Lord,” the latter presumably being the infant Lord Beauchamp.

The boy born in 1538 does not appear to have survived childhood. On May 22, 1539, Anne Seymour gave birth to a second son, Edward, who was christened at Beauchamp Place and whose godfathers were the Duke of Suffolk and the Duke of Norfolk. This was the Seymour son who grew up to become the Earl of Hertford, as evidenced by a letter describing the earl as 13 in 1552. (The keeper of Ludgate and Aldgate received 8 pence for “letting John Smith in and out in the night when he went for Mris Midwife.”)

All this, however, leaves us with a problem. Anne and Edward Seymour’s daughter Anne, whom we’ll call Anne II to save everyone’s sanity, is generally thought to have been born in 1538, but as we’ve seen, the child born in March 1538 was a boy, and another child can’t be squeezed in between March 1538 and May 1539. This must mean that Anne II was the girl born in February 1537. Or was she? Mary’s privy purse expenses indicate that on November 30, 1537, a gentlewoman of Lady Hertford’s brought two Seymour girls to visit the princess, and another November 1537 entry mentioned earlier refers to “one of” Lady Hertford’s daughters. Since nothing indicates that twins were born in February 1537, it seems that another Seymour girl had been born before February 1537. Because Edward Seymour and Anne Stanhope were married no later than March 9, 1535, there would have certainly been time for them to have two daughters born by November 1537. If Anne II was born in early 1536, she could have been named for Anne Boleyn, Henry’s current queen. (Indeed, given Anne Boleyn’s fate and subsequent image problem, “Anne” seems an odd name for a Seymour girl to have been given in February 1537, although Anne II could have been named after her mother.) This would mean that Margaret Seymour, the second Seymour daughter, was the girl born in February 1537. All this fits in nicely with an inventory dated in 1539 or 1540, which mentions the beds of Lady Anne and Lady Margaret, and with the purchase of a primer (a prayer book) for Lady Anne sometime between August 22, 1539, and December 31, 1539. The latter purchase would seem somewhat premature if Anne II had been born in 1538, but seems quite reasonable if she was born in 1536.

In sum, it seems certain that no son was born to the Seymours in 1537, that a son instead of a daughter was born in 1538, and that Anne Seymour didn’t get much of a break between babies. No wonder she was cranky!

All of these calculations come too late, by the way, to be reflected in my upcoming novel, in which Anne II is depicted, in line with conventional wisdom, as having been born in 1538. Forget you saw this post, please, when you read my book.

Sources:

Marjorie Blatcher, ed., Report on the Manuscripts of the Most Honourable Marquess of Bath Preserved at Longleat. Vol. IV. Seymour Papers 1532-1686. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1968.

Muriel St. Clare Bryne, ed., The Lisle Letters. Vols. 4 and 5. University of Chicago Press, 1981.

The Rev. Canon J. E. Jackson, “Wolfhall and the Seymours.” Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine, XV (1875).

Letters and Papers of Henry VIII.

Frederick Madden, ed., Privy Purse Expenses of the Princess Mary. London: William Pickering, 1831.

National Archives SE/VOL. X/8 22 Aug.-31 Dec. 1539

April 16, 2012

The Death of Anne Seymour, Duchess of Somerset

Hi, there! Between taxes and a lovely weekend in Washington, D.C., with the family, I haven’t had much time to blog, but I did want to stop in and commemorate the death of Anne Seymour, Duchess of Somerset. She’s an important character in Her Highness, the Traitor (coming out on June 1!), and I’m seriously considering giving her a novel to herself. What would you think of that?

Anne died at Hanworth in Middlesex on Easter Sunday, April 16, 1587. Her epitaph claims that she was ninety, but her year of birth has been more recently estimated as 1510, which seems more likely given her gynecological history (she bore her last child in 1550, after which her childbearing was interrupted by her husband’s imprisonment in October 1551 and execution in January 1552).

Anne herself had been arrested soon after her husband was seized and remained as a prisoner in the Tower until August 1553, when she was released by Mary I, with whom she had long been friendly. Over the next years, she managed to rebuild her fortunes; Retha Warnicke gives the value of her goods and moveables at her death as £9,829 19s 8d.

In 1600, William Dethick, Garter principal king of arms, recalled the duchess’s funeral:

At the sompteous and stately funeralls of the last Anne duchesse of Somerset, which were performed by the right honorable Edward earle of Hertford hir executor, anno 1587, there was a portraieture of the same duchesse made in robes of her estate, with a coronicall to a duchesse, and the same representation bore under a canopie; and all the other ceremonyes accomplished; and bycause there was no duchesse to assist thereat, the queen’s majesty gave her royal consent that the countesse of Hartford his wife should have all honour done to her after that estate during the funeral. As by warrant directed to me under her majesty’s hand appears.

The Earl of Hertford, who had married Frances Howard some years after his first marriage to Katherine Grey landed both of the spouses in the Tower, erected a fine tomb to his mother’s memory in the Chapel of St. Nicholas. The English epitaph, which fills four plaques, reads:

Here lieth entombed,

ANNE,

The noble Dutchess of Somerset,

Dear Spouse unto the renowned Prince

Edward, Duke of Somerset,

Earl of Hertford, Viscount Beauchamp,

And

Baron Seymour.

Companion

0f the most famous knightly Order of the Garter,

Uncle to King Edward the Sixth,

Governor of his Royal Person,

And most worthy Protector

Of all his Realms, Dominions, and Subjects.

Lieutenant-General of all his Armies,

Treasurer, and Earl-Marshal of England,

Governor, and Captain,

Of

The Isles of Guernsey, and Jersey;

Under whose prosperous Conduct,

Glorious Victory

Hath been so often, so fortunately

Obtained,

Over the Scots,

Vanquished at Edinburgh, and Leith,

And

Musselborough Field.

A Princess

Descended of noble Lineage,

Being

Daughter to the worthy Knight,

Sir Edward Stanhope,

By Elizabeth his Wife, that was Daughter to

Sir Foulke Bourchier,

Lord Fitz Warren:

From whom

Our Modern Earls of Bath are sprung.

Son was he

To William, Lord Fitz Warren,

That was Brother to Henry, Earl of Essex,

And William their Sire,

Sometime Earl of Eu, in Normandy.

Begat on Anne, the sole Heir of

Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester,

Younger Son, to the mighty Prince

Edward the Third,

And of his Wife Elinore;

Co-heir unto

The 10th Humprey De Bohun,

That was

Earl of Hereford, Essex, and Northampton,

High-Constable of England.

This Lady bare many Children, To wit,

Edward Earl of Hertford, Henry, and

A younger Edward;

Anne Countess of Warwick,

Margaret, Jane, Mary, Katherine,

And Elizabeth.

And with firm Faith in Christ,

And in most mild Manner,

Render’d she her Life

At Ninety Years of Age,

On Easter-Day, the 16th of April.

1587.

The Earl of Hertford, Edward her eldest Son,

In this doleful Duty careful and diligent,

Doth consecrate this Monument to his dead Parent;

Not for her Honour wherewith living she did abound,

And now departed, flourisheth;

But for the dutisul Love he beareth her,

And for his last Testisication thereof.

The photograph here shows Anne’s effigy, but the tomb itself is much larger. A photograph of the entire tomb can be found here.

Sources:

William Dethick, Garter. “Of the Antiquity of Ceremonies Used at Funeralls.” in Thomas Hearn, ed., Collection of Curious Discourses, Volume I, 1773.

Retha Warnicke, Wicked Women of Tudor England: Queens, Aristocrats, Commoners. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.