Susan Higginbotham's Blog: History Refreshed by Susan HIgginbotham, page 21

October 17, 2011

Mary Boleyn or Frances Brandon?

In her new book on Mary Boleyn, Alison Weir devotes an appendix to the subject of portraiture, including the identity of the sitter in this well-known painting, usually identified as one of Mary Boleyn:

Weir writes that because the sitter was wearing ermine, the portrait is unlikely to have been Mary Boleyn, because ermine was a "fur reserved exclusively for royalty and peers of the realm." She also notes that six versions of the portrait exist and questions whether there would have been sufficient interest in Mary to merit multiple copies. Instead of Mary Boleyn, Weir suggests, this may be a portrait of Frances Brandon, made to mark her marriage to Henry Grey.

I don't pretend to have researched Tudor costume, Tudor portraiture, or Tudor sumptuary laws in depth, but my search of what materials I have on hand doesn't suggest that the wearing of ermine was as restricted as Weir claims. In her book Rich Apparel, Maria Hayward summarizes the four acts of apparel enacted during Henry VIII's reign. By 1533, sable had been restricted to the king and his family, while black genette or lynx was restricted to dukes, marquesses, earls, and their children, or barons unless they were a knight of the Garter. Ermine, however, is not mentioned at all.

Notably, Elizabeth, Lady Vaux, wife of Thomas Vaux, a mere baron, is shown below conspicuously wearing ermine, which suggests that the fur wasn't reserved for the highest echelons of the nobility. (Fun Queen of Last Hopes fact: Thomas Vaux was the grandson of Margaret of Anjou's devoted lady-in-waiting, Katherine Vaux.) Here is Lady Vaux showing off her stoats:

Hayward also notes that an Elizabeth Speke left in her will a black satin gown "purfled [edged] with powdered ermines." It therefore seems to me that the ermine in itself isn't enough to rule out Mary Boleyn as the subject of the first portrait, especially since Mary gained status after her father was made a viscount in 1525 and an earl in 1529. Whether there was sufficient interest in Mary for multiple copies of the portrait to be made is another question, but I would think the same objection would apply to Frances, who is known to us today mainly because of her daughter. In any case, if the portrait is not one of Mary, it could be of any number of ladies who were sufficiently well-off to afford ermine.

October 7, 2011

New Nonfiction

I've been meaning to post for some time about the nonfiction books dealing with the Wars of the Roses and the Tudors that have caught my eye lately. Many of them have just recently been published. Here they are, more or less in historical order:

Susan Curran, The English Friend: A Life of William de la Pole, First Duke of Suffolk. As readers of The Queen of Last Hopes know, Suffolk was one of the narrators of the novel, and I was miserable for days after having to send him to his tragic fate. I read much of Curran's book on my Kindle today, and found that it told Suffolk's story movingly and sensitively. (I did wonder at the absence of a couple of books from the references cited, notably John Goodall's God's House at Ewelme, but on the whole I was quite impressed.) Curran, incidentally, is also the author of a historical novel, The Heron's Catch, which includes Suffolk as a major character.

Philippa Gregory, David Baldwin, and Michael Jones, The Women of the Cousins' War. This book, intended as a companion to Gregory's historical fiction, contains biographical essays about Jacquetta Woodville (by Gregory), Elizabeth Woodville (by Baldwin), and Margaret Beaufort (Jones). I've done no more than skim this in places, but am looking forward to it, particularly the portion by Jones, a specialist on the Beaufort family.

James Ross, John de Vere: Thirteenth Earl of Oxford, 1442–1513. This is an academic biography of the earl who helped Henry VII win the day at Bosworth Field. I've been able to read a library copy of it and will be begging hubby for a copy of my own for my birthday. It's a fascinating book about a relatively neglected figure from the Wars of the Roses.

Thomas Penn, Winter King: The Dawn of Tudor England. When I first saw the blurb for this book, I thought it was a novel, but it is in fact nonfiction about the reign of Henry VII, particularly about its last years. I haven't had a chance to do more than glance at it, but it looks to be a good read.

Erin Sadlack, The French Queen's Letters: Mary Tudor Brandon and the Politics of Marriage in Sixteenth-Century Europe. I've only read bits and pieces of this, but it looks to be invaluable. It includes all of Mary Tudor's extant manuscript letters, with the French ones translated into English.

Alison Weir, Mary Boleyn: The Mistress of Kings. I read this for the Historical Novels Review (review to appear in the November issue). I didn't agree with all of the author's conclusions, and much about Mary remains speculative, but I did think that Weir made a good effort to separate myth from fact.

Janel Mueller, Katherine Parr: Complete Works and Correspondence. This includes letters written to Katherine Parr as well as her own writings. Mueller's book also has an account of Katherine's funeral and an inventory of her goods. Incidentally, Mueller believes from handwriting comparison that the prayer book which Jane Grey wrote messages in and carried to the scaffold was originally written by Katherine Parr. Accordingly, the book contains a complete transcription of the prayer book. (I was surprised to realize just how tiny the prayer book is.)

John Edwards, Mary I: England's Catholic Queen. This is a new biography of Mary, as you can guess from the title. I'm about halfway through it and am finding it fascinating. A full review by a specialist on Mary can be found here.

Susan Doran and Thomas S. Freeman, Mary Tudor: Old and New Perspectives. This is a collection of essays about Mary I, as you might expect. I haven't been able to do more than glance at a couple, but I'm looking forward to an in-depth reading of it.

Is there any new nonfiction that's caught your eye? How about fiction?

September 30, 2011

So, Sir, When Did You Stop Raping Your Wife?

A few weeks ago, I received a copy of Philippa Wiat's 1983 novel about Katherine Grey, Five Gold Rings. The novel opens with a chapter showing Katherine's older sister, Lady Jane Grey, being cajoled, whipped, and finally raped by a man whose identity is concealed from the reader until the last line in the chapter: it is her father.

This episode is entirely fictitious; while there are certainly sins that could be laid at the door of Henry Grey, Duke of Suffolk, incest and rape are not among them. The incident has little connection to the rest of the plot, most of which centers around Katherine Grey's love affair with and marriage to the Earl of Hertford. It is apparently there only to arouse the reader's loathing for the duke.

As a reader, I seem to be noticing more of these sort of episodes in historical fiction lately—incidents with no historical basis and with little literary justification for their existence. While I haven't read enough of these episodes, fortunately, to speak of them as a trend, I've seen enough of them to be disturbed. A novel I recently read about Cleopatra Selene, for instance, had Octavian attempting to rape the preteen heroine shortly after her mother's suicide, stopping only at the urging of his companion. I've previously mentioned in this blog a novel set during the Wars of the Roses where a young and saintly Richard, Duke of Gloucester, witnesses a drunken William Hastings rape a virgin peasant girl, whom he has drugged; the girl later dies of the effect of the drug. The same author in another novel depicts John Morton as lusting after choirboys; in yet another one, Henry VII orders Elizabeth of York to have premarital sex with him so that he can test her virginity. I'm not at all knowledgeable about Octavian, but I can attest from my own research that there's no evidence whatsoever that Hastings was a rapist, that Morton was a pedophile, or that Henry VII forced Elizabeth of York into his bed.

Far more common, however, are novels that stop short of making their villain a sexual predator, but depict him as a brute in the marital bed. This is usually done by having a man consummate his marriage in a style that is little short of rape. With some historical figures, such scenes are almost a given: for instance, novelists are fond of having the newlywed Guildford Dudley deflower Jane Grey in this manner (the possibility that Jane might have enjoyed or at least tolerated sexual relations with a young and reputedly good-looking man being too painful a notion for many to entertain). Likewise, novelists, particularly admirers of Richard III, often have Edward of Lancaster brutally initiate Anne Neville into marriage, which not only underscores the hopelessly evil nature of the House of Lancaster but gives Anne's second husband, the Duke of Gloucester, a fine opportunity to demonstrate his immense sensitivity when Providence finally places Anne in his bed. Such scenes have made it to the screen as well: in the miniseries "The Tudors," George Boleyn, who would clearly rather be with a male partner, gets his marriage to Jane Parker off to a particularly bad start. Again, these episodes are ahistorical; we have no idea of what happened between these couples in bed.

So why include these scenes in novels? In the right hands, depicting sexual assault can be powerful and disturbing: In Sharon Penman's The Sunne in Splendour, for instance, there's a scene very early in the book where a young servant girl is dragged off by Lancastrian troops and raped. That episode serves a purpose: it illustrates the horrors that war inflicts upon innocent bystanders, and it is also based upon fact, as the chronicles record that there was rape at Ludlow. The episodes like those involving the Duke of Suffolk, however, fulfill no similar purpose; they could have been left out of the novels in question without anything being lost thereby. Their sole raison d'être appears to be to make characters who are already being portrayed as villains several shades more black or (in the case of Hastings) to prevent the reader from according him any sympathy when he later dies at the hands of the saintly Duke of Gloucester.

Those men who are depicted as novelists as behaving brutally in the marital bed are a somewhat different matter. In one of my own novels, I have a man rape his wife: it is an aberration by a decent man in what has been a mostly happy marriage, and occurs at a time when the spouses are furious at each other and under great stress. In some novels and historical films, those husbands who start off treating their wife badly do improve with time. (Even George Boleyn in "The Tudors" has a lovable side.) It is the other cases—those where the man's behavior toward his wife is simply a continuation of his villainous behavior in every other sphere of his life, and where there's no historical basis for such a characterization—that I find objectionable.

Writing about sexual relations between historical figures is a delicate matter, of course. With many historical couples, we can only guess about whether their marriage was happy or otherwise, and we know even less about what went on in the most intimate part of their lives. Some invention, therefore, is inevitable, and indeed inescapable if we are to write a readable novel. But for the responsible novelist, that literary license shouldn't extend to ascribing sexual crimes or misdeeds to men that history never attributed to them simply because it's too much trouble to add a few shades of gray to a character's color palette.

September 27, 2011

Frances Grey's Date of Remarriage, Revisited

A while back, I wrote a post about the myths about Frances Grey, Duchess of Suffolk. One of those I mentioned was the date of her remarriage to Adrian Stokes. Recently, as I noted, historians have leaned toward the idea that the marriage took place in 1555, instead of in 1554, just weeks after the executions of her husband and her daughter Jane.

The other day, however, I stumbled upon the inquisition postmortem that apparently is the source of the 1554 story—an inquisition that took place in Warwickshire on May 7, 1560, and of which a certified copy was made on February 14, 1600. The inquisition, as printed in the Calendar of State Papers, states, "That the Duke of Suffolk died at London, 1st Mary, and the land remained in the hands of the Duchess, when on 9 March, 1 Mary, 1554, she married Adrian Stokes; that they had issue a daughter Elizabeth, born at Knebworth, co. Herts, 16 July, 1 & 3 Philip and Mary, 1555, who lived till 7 Feb following, and then died at Knebworth. That the said Frances died at London, 21 Nov., 2 Eliz., 1559, Stokes surviving her."

Naturally, this didn't please me, since my novel, reflecting current thought, has Frances and Adrian marrying in 1555. So I hit the National Archives and came up with three documents mentioning Frances's marriage. The first, found at C 142/128/91, appears to be the same inquisition referred to above, as it was taken "in the second year of the reign of Elizabeth" and involves the same lands in the county of Warwick and was taken before the same commissioners. It gives a 1554 date for the marriage:

And the same Frances, duchess of Suffolk, named in the said writ, being thus seised of the premises, on the 9th day of March in the first year of the said late Queen Mary, at Kayhoe in the county of Surrey, took as her husband Adrian Stokes, esquire, by virtue of which the same Adrian Stokes and the aforesaid Frances the duchess, his wife, were seised of the aforesaid college, manors, rectories and other premises with appurtenances in their demesne as of fee tail as in the right of the same duchess, viz of the aforesaid college and other premises with appurtenances, specified in the aforesaid letters patent, to the aforesaid duchess and the heirs of the body of the said late Henry, duke of Suffolk, and the aforesaid Frances the duchess lawfully begotten, and of the aforesaid manor of Monkeskyrby, Brockeste, Walton, Paylton, Straydeston, Newbolde, Horborough, Lawford, Eysnell, Woolvey, Copston, Rookebye and Willey, and the other premises with appurtenances to the aforesaid duchess and the heirs of her body lawfully begotten. And the same Adrian Stokes and Lady Frances, duchess of Suffolk, his wife, being thus seised of the aforesaid college, manor and other premises, as is aforesaid, afterwards had issue, viz one daughter called Elizabeth among others lawfully begotten. Which same Elizabeth on the 16th day of July in the first and third years of the reigns of King Philip and the said late Queen Mary, at Knebworth in the county of Hertford, was born and begotten and lived in the world from the aforesaid 16th day of July until the 7th day of February then next following, on which day the aforesaid Elizabeth at Knebworthe, aforesaid, died. And the said jurors say further that the aforesaid Adrian Stokes and Frances, duchess of Suffolk, being thus seised of the premises, as is aforesaid, afterwards, viz on the 21st day of November in the second year of the said now lady queen, the same Frances died at the city of London seised thereof as of estates tails, and the aforesaid Adrian Stokes survived her and kept himself within the aforesaid manor of Monkeskyrby and the other premises in Monkeskyrby, Brockest, Walton, Paylton, Streytiston, Newbolde, Horbury Magna, Horbury Parva, Lawforde, Eysenell, Wolvey, Scopton, Rougby, Newneham, Wythybroke, Marson Jubytt, Cosforde, Happesforde, Halfpathe, Brinkeley and Wylley, and in Crycke and Sharisforde, aforesaid, as tenant by the curtesy of England, with remainder thereof to the right heirs of the body of the said Frances lawfully begotten. . . . And the said jurors say further that Lady Katherine Grey and Lady Mary Grey are the daughters and next heirs both of the bodies of the said Henry, late duke of Suffolk, and Lady Frances his wife lawfully begotten and of the said Frances, duchess of Suffolk. And that the aforesaid Lady Katherine at the time of the death of the said duchess of Suffolk was of the age of 19 years. And that the aforesaid Lady Mary Grey at the time of the death of the said duchess was of the age of 14 years.

The second document (WARD 7/14/93), an inquisition "taken at Borne in the county of Lincolnshire on the 15th day of March in the 16th year of the reign of our lady Elizabeth" (March 15, 1574), simply states that "being seised in an estate tail, [Frances] took as her husband a certain Adrian Stokes, esquire, and died on around the 11th day of November in the first year of the reign of our now lady queen, after whose death the said Adrian Stokes kept himself inside as tenant by curtesy of the kingdom of England." Note that the date of death differs from the date in the Warwick inquisition.

The third inquisition (C 142/254/2) "taken at Wincaunton in the aforesaid county [Somerset] on the third day of April in the 40th year of the reign of our Lady Elizabeth" (April 3, 1598), gives no date for Frances and Adrian's marriage. It too gives Frances's death date as November 11, 1559. Maddeningly, it states that "the aforesaid Adrian had issue of the body of the same Frances lawfully begotten between them," but gives no particulars.

With the only inquisition which gives specifics stating that Frances and Adrian were married in 1554 and that they had a child in 1555, the case might appear to be closed. Inquisitions post mortem, however, aren't infallible, as the conflicting death dates here—November 21 in the Warwick inquisition, November 11 in the ones from Lincolnshire and Somerset—neatly attest.

Moreover, Elizabeth Stokes' birthdate is given as July 16—which happens to be Frances's own birthdate. It's certainly possible that Frances and her daughter shared a birthday, but this does make one wonder if there was some confusion on the part of the jurors.

Furthermore, none of the contemporary records I have found from 1554 refer to Frances as being then married to Adrian Stokes. In a letter dated from London on March 15, 1554, John Banks wrote to Henry Bullinger in eulogistic terms about the recent deaths of Lady Jane and her father, but made no mention of Frances's remarriage, which surely would have merited a disapproving line or two had it taken place by then. An entry in the Calendar of Patent Rolls dated April 10, 1554, records that the crown granted Frances a life estate in Beaumanor and other properties; the grant makes no mention of Adrian, as would have been necessary had Frances been married to him. On May 8, 1554, Queen Mary's privy council allowed the Duchess of Suffolk (presumably Frances and not her fiercely Protestant stepmother, Katherine Brandon, Duchess of Suffolk) to use the House of Croydon; again, no mention is made of Adrian. Indeed, as late as April 20, 1555, Simon Renard, the imperial ambassador, wrote to the emperor Charles, "It has been proposed that Courtenay [Edward Courtenay, Earl of Devon, recently released from prison] might be married to the widow of the last Duke of Suffolk, who comes next to the daughter of Scotland in line of succession to the crown. If this is done, it will make Elizabeth very jealous, and would give rise to much dissention in the kingdom if the Queen died without issue." It seems unlikely that those suggesting Frances as a possible bride for the Earl of Devon would not have heard of the matter if she had been already married the year before to Stokes. (Ungallantly, Simon Renard continued, "But I hear that Courtenay would rather leave the country than marry her.")

All in all, then, I'm inclined to think that the Warwick inquisition postmortem got the date of Frances's marriage, and the date of the birth of her daughter Elizabeth Stokes, wrong. In other words, I'm going to stick with writing the story that I have written. Still, I do care about historical accuracy, so if anyone runs across any further evidence supporting the 1554 date, feel free to let me know—but do it gently, please.

September 22, 2011

Did Jane Grey's Parents Resent Her Because She Was Not a Boy?

Firmly enshrined in the pages of popular nonfiction about Lady Jane Grey is the notion that her parents resented her and her sisters because they were not sons. Hester Chapman writes that the "Dorsets were disappointed at not having a son" when Jane was born, and goes on to state that Frances Grey "could not forgive" her daughters for their sex. Alison Weir writes that Henry Grey "regarded [Jane] as a poor substitute for the son who had died young before her birth." In her truly execrable biography, Mary Luke devotes a whole two paragraphs to Frances's longing to bear her husband a male child, ending with her "sobbing heartbreakingly" when she discovers she has borne a girl. Mary Lovell in her biography Bess of Hardwick writes that after the death of the Greys' son, Frances gave birth to her daughters, "to whom their parents made it abundantly clear that they were a major disappointment." None of these writers cite a source for their claim, for the very good reason that there is none.

It is true, of course, that Henry and Frances Grey had lost two children, one a boy, in infancy before Jane's birth. Frances had married Henry Grey in the spring of 1533 and gave birth to Jane sometime in 1537, probably in the spring. Thus, by the time Jane was conceived, Frances had already lost two children in a fairly short period of time, which could hardly have been encouraging as Frances waited to see whether her next baby would also be short-lived. She and her husband might well have hoped for a son—parents of their class generally did—but there's simply no evidence that they did not greet the birth of a daughter with happiness, particularly when the infant survived instead of following her siblings to the grave. As Eric Ives points out, Henry and Frances Grey, the young Marquis and Marchioness of Dorset, were not in the public eye when their most famous daughter was born, and neither her date nor her place of birth has been recorded, much less her parents' reactions to her arrival in the world.

An extension of the story that the Greys were hugely disappointed in their daughters' sex is that having resigned themselves to their lack of sons, they began scheming to use their daughters as pawns from their infancy on. Lovell takes this story even further, writing that when the Greys' son was born, "the delighted parents planned to achieve their ambitions of great power and riches through the marriage of this hapless baby to either Princess Mary or Princess Elizabeth." Not only is this entirely fictitious, it's nonsensical: assuming that the Greys' son was born around 1534, Mary was eighteen, hardly a suitable bride for an infant, and was then being treated as illegitimate. Nor were Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn likely to countenance the marriage of Princess Elizabeth to an English cousin when a great match could be made abroad.

As for the Greys' daughters, there was nothing shameful in their parents wanting to marry them well; it was what noble parents did with their daughters, and what daughters expected. Moreover, what is often overlooked is that for the first few years of their marriage, Henry and Frances Grey were still very much under the thumb of their own parents. The couple had married in the spring of 1533, when Frances, born in July 1517, was not quite sixteen; Henry Grey, born in January 1517, was just six months older than his bride.

When Henry's widowed mother, Margaret Grey, Marchioness of Dorset (née Wotton), and Frances's father, Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, arranged the couple's marriage, it was agreed that Suffolk would support the pair until Henry Grey came of age. A cash-strapped Suffolk tried to renege on this agreement, but Margaret would have none of it: she enlisted Thomas Cromwell in her fight and succeeded in forcing the duke to back down. Meanwhile, a letter from Margaret dated February 4, 1534, indicates that after his marriage Henry Grey had stayed at court, where Margaret asked Cromwell to rebuke him if he happened to see the seventeen-year-old "either any large playing, or great usual swearing, or any other demeanour unmeet for him to use, which I fear me shall be very often." Frances, meanwhile, was staying "in the country; or else she and her train to be with me where I am." Henry Grey was still apparently at court a year later, for on February 5, 1535, Margaret again wrote to Cromwell, thanking him "for the great goodness that my son marquis daily findeth in you, praying you so to continue to him, and that he from time to time may have your good counsel when you shall see need."

Since Jane would have been conceived in 1536, and Frances had given birth to two children already by that time, Henry and Frances obviously spent some time together, though where they lived is unclear, for Henry's mother was in possession of the family estates. Losing their first two children in infancy when the parents themselves were little more than youngsters surely must have tried the couple's marriage, especially if the pair was frequently apart. To make matters worse, Henry's relationship with his mother was strained, and Frances's own mother had died in 1533, soon after Frances's wedding.

In October 1537, the future Edward VI was born, and the Greys—Margaret, Henry, and Frances—were all eager to attend the christening, where Margaret had been expected to carry the young prince. Unfortunately, a servant reported to Henry VIII that there had been plague at Croydon, where Margaret was staying with her son-in-law Lord Matravers. The king wasted no time barring Margaret and her family from attending the christening of his long-hoped-for son, even though Henry Grey protested that he had not been with his mother, but at Stebbing (a Grey manor), and that Frances had been staying with Lady Derby. Sadly, the next royal event the couple would attend was Jane Seymour's funeral.

As mentioned earlier, Henry Grey finally came of age in 1538 and received livery of his estates in July of that year, although he and his mother continued to quarrel about his inheritance until at least 1539, with the rancor typical of such disputes and with Cromwell as a probably reluctant middleman. Thus, it was not until July 1538—well after the birth of Lady Jane—that Henry and Frances were truly on their own. In 1537, then, far from plotting in Lord and Lady Macbeth–like fashion to put their daughter on the throne, the pair were perhaps more likely dreaming of the day when they would at last be the lord and lady of their own manor.

Sources

Mary Anne Everett Green, Letters of Royal and Illustrious Ladies of Great Britain

S. J. Gunn, Charles Brandon

Eric Ives, Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Mystery

Letters and Papers of Henry VIII

Leanda de Lisle, The Sisters Who Would Be Queen

Barbara J. Harris, English Aristocratic Women, 1450-1550

September 18, 2011

The Death and Burial of Frances, Duchess of Suffolk

In 1559, the chronicler Henry Machyn, a merchant and a parish clerk who faithfully recorded details of heraldic funerals, wrote, "The v day (of) Dessember was bered in Westmynster abbay my lade Frances the wyff of Harec duke of Suffolke, with a gret baner of armes and viij banar-rolles, and a hersse and a viij dosen penselles, and a viij dosen skockyons, and ij haroldes of armes, master Garter and master Clarenshux, and mony morners."

Photo by lisby1. Used via Creative Commons license.

Frances, Duchess of Suffolk, mother to the late Lady Jane Grey as well as to Katherine and Mary Grey, had been ailing since at least November, when she made her will:

In the name of God, Amen. I ladye Fraunces Duches of Suffolke, wife to Adryane Stockes esquyer, considering howe uncerteyn the howre of deathe is, and how certeyne ytt ys that every creature shall dye when ytt shall please God, being sicke in bodie but hole in mynde, thankes be to Almightie God; and considering with my self that the said Adrian Stockes my husbande is indebted to dyvers and sundrye persones in greate somes of money, and also that the chardge of my funeralles, if God call me to his mercye, shalbe greate chardges to hym, mynding he shall have, possesse, and enjoye all goodes, catalles, as well reall as personall, as all debtes, legacies, and all other thinges whatsoever I may give, dispose, lymytt, or appoynt by my last will and testament for the dischardge of the saide debtes and funeralles, do ordeyne and make this my present last will and testament, and do by the same constitute and make the saide Adryane Stockes my husbande my sole executor to all respectes, ententes, and purposes. In wytnes whereof I have hereunto putt my hande and seale the ix th daye of November, in the furst yere of the reigne of our soveraigne ladye Elizabeth, by the grace of God quene of Englande, Fraunce, and Irelande, defendour of the faythe, &c. Fraunces Suffolke.

Sealed and delyvered in the presence of. these under wrytten: Roberte Wyngfelde, Edmund Hall, Frauncis Bacon, and Robert Cholmeley.

Proved before the keeper of the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, 28th of November, 1559, by the oath of Justinian Kidd, proctor of Adrian Stockes.

One of these witnesses is of particular interest: Robert Wingfield. Could this be Robert Wingfield of Brantham, who wrote the Vita Mariae Angliae Reginae, a highly sympathetic account of Mary's recovery of her throne? Wingfield did take pains in his chronicle to note that Frances was "vigorously opposed" to her daughter Jane's match with Guildford Dudley, "but her womanly scruples were of little avail." He also had ties with Lady Jane's famous visitor, Roger Ascham, whom he described in the Vita as "my very good friend."

A postmortem inquisition on May 7, 1560, gives the date of Frances's death as November 21, 1559, making her 42 at the time of her decease. (John Strype, however, gives her date of death as November 20.)

On December 3, 1559, Elizabeth directed Sir Gilbert Dethicke, Garter King at Arms, and William Harvey, Clarencieux King at Arms, to augment Frances's arms by quartering the royal arms with them. Archibald Barrington reproduced the queen's letter to Garter:

Trusty and well-beloved, we greet you well, letting you to understand that for the good zeal and affection which we of long have borne to our dearly-beloved cousin, the Lady Frances, late Duchess of Suffolk, and especially for that she is lineally descended from our grandfather, King Henry VII., as also for other causes and considerations as thereunto moving, in perpetual memory of, thought fit, requisite, and expedient, to grant and give unto her and to her posterity, an augmentation of our arms, to be borne with the difference to the same by us assigned, and the same to bear in the first quarter, and so to be placed with the arms of her ancestors—viz., "our arms within a border, gobony, or and az.," which shall be an apparent declaration of her consanguinity unto us. Whereupon we will and require you to see the same entered into your registers and records, and at this funeral to place the same augmentation with her ancestor's arms, in banners bannerols, lozenges, and escutcheons, and otherwise when it shall be thought meet and convenient.

The details of Frances's funeral, which took place two days later, can be found in a manuscript in the College of Arms. John Strype summarized the account as follows:

December the 5th, the duchess of Suffolk, Frances, sometime wife of Henry, late duke of Suffolk, was buried in Westminster-abbey. Mr. Jewel (who was afterwards bishop of Sarum) was called to the honourable office to preach at her funerals, being a very great and illustrious princess of the blood; whose father was Brandon, duke of Suffolk, and her mother Mary, sometime wife of the French king, and sister to king Henry VIII. She, the said Frances, departed this life November the 20th, in the second year of the reign of queen Elizabeth; not in the sixth of her reign, as Mr. Camden hath put it; led into that mistake, I suppose, by the date on her monument; which indeed shewed not the year of her death, but of the erection of that monument to her memory, by her last husband Mr. Stokes. She was buried in a chapel on the south side of the choir, where Valens, one of the earls of Pembroke, was buried. The corpse being brought and set under the hearse, and the mourners placed, the chief at the head, and the rest on each side, Clarenceux king of arms with a loud voice said these words; "Laud and praise be given to Almighty God, that it hath pleased him to call out of this transitory life unto his eternal glory the most noble and excellent princess the lady Frances, late duchess of Suffolk, daughter to the right high and mighty prince Charles Brandon, duke of Suffolk, and of the most noble and excellent princess Mary, the French queen, daughter to the most illustrious prince king Henry VII." This said, the dean began the service in English for the communion, reciting the ten commandments, and answered by the choir in pricksong. After that and other prayers said, the epistle and gospel was read by the two assistants of the dean. After the gospel, the offering began after this manner: first, the mourners that were kneeling stood up: then a cushion was laid and a carpet for the chief mourners to kneel on before the altar: then the two assistants came to the hearse, and took the chief mourner, and led her by the arm, her train being borne and assisted by other mourners following. And after the offering finished, Mr. Jewel began his sermon; which was very much commended by them that heard it. After sermon, the dean proceeded to the communion; at which were participant, with the said dean, the lady Catharine and the lady Mary, her daughters, among others. When all was over, they came to the Charter-house [Frances's residence of Sheen] in their chariot.

Leanda de Lisle writes that Katherine Grey, Frances's oldest surviving daughter, was her chief mourner, a role Frances herself had played at her own mother's funeral. (A chief mourner had to be the same sex as the deceased, so a spouse could not play the role.)

Adrian Stokes erected a fine monument to Frances, which still exists today, in 1563. The Westminster Abbey website identifies it as possibly being by Cornelius Cure. It contains inscriptions in English and Latin, the first of which reads: "Here lieth the ladie Francis, Duches of Southfolke, daughter to Charles Brandon, Duke of Southfolke, and Marie the Frenche Quene: first wife to Henrie Duke of Southfolke and after to Adrian Stock Esquier." The Westminster Abbey website translates the Latin inscription as follows:

Dirge for the most noble Lady Frances, onetime Duchess of Suffolk: naught avails glory or splendour, naught avail titles of kings; naught profits a magnificent abode, resplendent with wealth. All, all are passed away: the glory of virtue alone remained, impervious to the funeral pyres of Tartarus [part of Hades or the Underworld]. She was married first to the Duke, and after was wife to Mr Stock, Esq. Now, in death, may you fare well, united to God.

The fact that the inscription does not mention Frances's daughters has been taken by some of a final proof of the duchess's supposed failings as a mother, but it should be remembered that when Stokes erected this monument, Katherine Grey was a prisoner of the Crown for her presumption in having married Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford, without royal permission. Stokes had been one of those questioned about the events leading up to the clandestine marriage. Katherine's place in the royal succession was also a very delicate subject in the 1560′s. Thus, assuming that Stokes made a conscious decision not to mention Frances's daughters on her tomb, he was most likely not being disrespectful but prudent.

Sources

Archibald Barrington, Lectures on Heraldry.

Leanda de Lisle, The Sisters Who Would Be Queen

John Gough Nichols, The Diary of Henry Machyn.

John Gough Nichols, Wills from Doctor's Commons.

John Strype, Annals of the Reformation and Establishment of Religion.

September 12, 2011

Buttons and Books: Some Goods of John Dudley, Viscount Lisle (d. 1554)

While looking for something else over the weekend, I stumbled upon these excerpts from an inventory of the goods of John Dudley, Viscount Lisle, later Earl of Warwick. John was the oldest surviving son of John Dudley, Earl of Warwick, who became the Duke of Northumberland in 1551.

In 1871, Henry Thomas Riley published excerpts from the inventory in the Second Report of the Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts. The comments in brackets are those of Riley, who was under the mistaken impression that the goods were those of John's father. According to Barrett Beer in Northumberland: The Political Career of John Dudley, Earl of Warwick and Duke of Northumberland, the complete inventory can now be found at Bodleian MS Add. C94, and I hope to obtain a transcript of it one day.

The younger John Dudley, by then the Earl of Warwick, was imprisoned along with his father and his brothers after the ill-fated attempt to put Lady Jane Grey on the throne. He was tried and sentenced to death at the same time as his father, but was spared execution. Warwick died on October 20, 1554, just days after his release from the Tower, at Penshurst, the home of his sister Mary and her husband, Henry Sidney. He was the Dudley brother who carved the famous graffito in the Beauchamp Tower seen here.

The inventory here was not made in connection with John's imprisonment, but was made several years earlier by a Dudley servant, J. Hough. Hough carefully noted his master's possessions and their subsequent fate.

Here are some selections from the excerpts mentioned by Riley. With this first batch, I enjoyed learning how shirts could be recycled. (Not even gifts from one's mother were sacred):

Two [shirts] made in handkerchers at Peudley, 1548 Julii 20.

Item, iii shirts, wherof one was made in bagg to put my Lordes shirtes in, at Canburie, 1548 Mar. 10.

Item, a shirt of blackworke, which my Lady Duddeley yave my Lord, cut in to handkerchers at London, 1550 December 22.

John's brother Robert must have enjoyed getting this:

Item, a velvet cote sett with roses and ragged staves of goldsmithes worke, whiche my Lady of Warwick had at Enveld, and yaue the cote to Sir Robert Duddeley, 1548 Janu. 8.

Some of the inventory is taken up with the fate of John's buttons:

Item, xxxii poynted buttons, yeven to Mr. John Seamour for a 1 velvet capp with xix pare of agglets, 1547 Apr. 8.

(John Seymour was probably the illegitimate brother of Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset.)

Item, 4 dosen and 8 damascene buttons syxe cornerd, wherof 2 dosyn were yeven to Mr. Gildford Duddeley at Westmister, 1550 Maii 18.

Item, 4 buttons were cut of my Lords gowne in the privie chamber by Mr. Fuwilliams [Fitz-William], and never gottin againe, 1550 June 29.

Item, 36 buttons of goold, sex cornerd, and black enamiled changed for 31 pare of black enamiled agletes: which agletes and 8 pare mo of the same makying and bought the same tyme, and 39 black enamiled buttons, all sett on a velvet cap, were stollen, cap and all, at Hatfeld, 1550 June 24.

Young John seems to have been parted from his caps on several occasions:

Item, a black velvet cap, lost [in a wager] to Mr. John Seamour at Reading, 1550 Aug. 12.

Item, a black velvet capp lost at my Lord of Huntintones, 1550 October 23.

Item, a velvet cap, lost in laye to Jakes Granado, at Westminster, for running at the ring, 1550 June 6.

One wonders if someone in the laundy at Ely House didn't have slippery fingers:

Item, 6 shirtes . . . wherof 2 were lost at the landry at Ely House, 1550 Sept. 15.

John also possessed an impressive array of books, which show that his tastes were broad:

Item, thone part of Tullie.

Item, Locci [? " Flacci," meaning Horace] et Aeneadas.

Item, Anthonius Luscus.

Item, a boke to play at Chistis, in Aglishe.

Item, a bokc to speake and write Frenche.

Item, 2 bokes of Cosmografye.

Item, a old paper boke.

Item, Hormans Volgaries [Vulgaria].

Item, the Kyngis Grammar.

Item, Sidrack and King Bockus.

Item, a plaine declaration of the Crede.

Item, Carmen Buco Oolpkurnii [Bucolicum Calphurnii]

Item, a paper boke.

Item, Epistles from Seneca to Paule.

Item, aponapis [?] of Mr. Mohsons.

Item, a Frenche boke of Christ and the Pope.

Item, a boko of Arthmetrik in Lattyn.

Item, a Tragidie in Anglishe of the unjust supremicie of the Bisshope of Rome.

Item, a Play of Love [by John Heywood].

Item, a play called the 4 pees [P's, by Heywood].

Item, a play called Old Custome.

Item, a play of the Weither [by Heywood].

Item, a boke to write the Roman hand.

Item, a paper boke of Synonimies.

Item, a Greke Grammar.

Item, a Catachismus.

Item, Apothegmata.

Item, the Debate between the Heraldes [? temp. Richard II., recently published].

Item, Tullies Office.

Item, Sententiae Yeterum Poetarum.

Item, a boke of Phisick, in Greeke.

Item, Aurilius Augustinus.

Item, a boke of Conceits.

Item, a Italian boke.

Item, a Italian boke.

Item, ad Herenium.

Item, a Terence.

Item, an Exposition of the Crede, in French.

Item, a Testament in Frenche, covered with black velvet.

Item, an Anglishe Testament.

Incidentally, an additional light is shed on John's intellectual interests by his contemporary and friend John Dee, the mathematician and astrologer. In his Preface to Euclid, Dee wrote of John Dudley:

Who was a yong Gentleman, throughly knowne to very few. Albeit his lusty valiantnes, force, and Skill in Chiualrous feates and exercises: his humblenes, and frendelynes to all men, were thinges, openly, of the world perceiued. But what rotes (otherwise,) vertue had fastened in his brest, what Rules of godly and honorable life he had framed to him selfe: what vices, (in some then liuing) notable, he tooke great care to eschew: what manly vertues, in other noble men, (florishing before his eyes,) he Sythingly aspired after: what prowesses he purposed and ment to achieue: with what feats and Artes, he began to furnish and fraught him selfe, for the better seruice of his Kyng and Countrey, both in peace & warre. These (I say) his Heroicall Meditations, forecastinges and determinations, no twayne, (I thinke) beside my selfe, can so perfectly, and truely report. And therfore, in Conscience, I count it my part, for the honor, preferment, & procuring of vertue (thus, briefly) to haue put his Name, in the Register of Fame Immortall.

To our purpose. This Iohn, by one of his actes (besides many other: both in England and Fraunce, by me, in him noted.) did disclose his harty loue to vertuous Sciences: and his noble intent, to excell in Martiall prowesse: When he, with humble request, and instant Solliciting: got the best Rules (either in time past by Greke or Romaine, or in our time vsed: and new Stratagemes therin deuised) for ordring of all Companies, summes and Numbers of mẽ, (Many, or few) with one kinde of weapon, or mo, appointed: with Artillery, or without: on horsebacke, or on fote: to giue, or take onset: to seem many, being few: to seem few, being many. To marche in battaile or Iornay: with many such feates, to Foughten field, Skarmoush, or Ambushe appartaining: And of all these, liuely designementes (most curiously) to be in velame parchement described: with Notes & peculier markes, as the Arte requireth: and all these Rules, and descriptions Arithmeticall, inclosed in a riche Case of Gold, he vsed to weare about his necke: as his Iuell most precious, and Counsaylour most trusty. Thus, Arithmetike, of him, was shryned in gold: Of Numbers frute, he had good hope. Now, Numbers therfore innumerable, in Numbers prayse, his shryne shall finde.

September 7, 2011

How Old Was Guildford Dudley? (Beats Me.)

One of the many failings of Lady Jane Grey's contemporaries, for the purposes of a novelist at least, is that no one bothered to write down the age of Guildford Dudley. Secondary sources give his age at his death as anywhere from seventeen to nineteen.

One clue exists as to Guildford's age, however: his godfather. Two letters indicate that Guildford's godfather was Diego Hurtado de Mendoza, a Spanish diplomat, poet, and book collector. Sir Richard Morrison wrote in a letter to Guildford's father, the Duke of Northumberland, on April 11, 1553, "Don Diego has promised to write to your Grace. I think my Lord Guildford, your son and his godson, shall have a fair genet from him." Later, after Guildford had married Jane Grey, Morrison and Sir Philip Hoby reported that Don Diego, having heard (mistakenly) that Guildford was to be crowned as king, said, "I was his godfather, and would as willingly spend my blood in his service as any servant he hath."

When would Don Diego have crossed paths with the Dudley family in order to have served as Guildford's godfather? On March 21, 1537, the Emperor Charles V ordered Don Diego to England to arrange a marriage between Princess Mary and the Infant Don Luis of Portugal. On June 6, 1537, Thomas Cromwell informed Thomas Wyatt that Don Diego had arrived in England the Wednesday after Pentecost and had met Henry VIII at Hampton Court. Don Diego remained in England until the end of August 1538. In February 1538, he had grumbled, "I am in good health, and yet, though there has been no cold weather this winter, I am as frozen and dead with it as if I had been living in Russia. . . . I must confess that, although this is pretty good living for one who is somewhat used to it, I would much rather prefer being at Barcelona."

John Dudley, who as David Loades put it was still "a minor office-holder and middle-ranking courtier" as of early 1537, seems unlikely to have had any contact with Don Diego before the latter's arrival in England. Other than being part of of Wolsey's large entourage in an embassy to France in 1527, he had had no diplomatic experience. Probably, then, it was after Don Diego came to England that he somehow met John Dudley and agreed to be his son's godfather.

If life were simple, this would put Guildford's birth between May 1537 and September 1538, making him about the same age, or even younger, than his bride, who Eric Ives has deduced was probably born in the spring of 1537. Alas, though, it is not entirely certain that Diego was the godfather at Guildford's christening: he could have been the godfather at Guildford's confirmation. If a bishop was present, a child could be christened and confirmed on the same day, as was Prince Edward, who had one godmother and two godfathers "at the font" and a third godfather at the confirmation. If no bishop was present, the confirmation would take place at some later time.

The future queen Mary was called upon to be a godmother at both christenings and confirmations–and she performed this service for the Dudleys both in January 1537, when she served as godmother at the confirmation of an unnamed Dudley daughter, and in March 1537, when she served as godmother at the christening of an unnamed Dudley son. On the latter occasion, Mary gave monetary presents to Jane Dudley's nurse and to her midwife. Is it possible that the boy christened in March 1537 was Guildford, and that Don Diego served as his godfather when he was confirmed some months later? One can only speculate. The infant boy christened in March 1537 could not have been Robert Dudley, who was likely born in 1532 or 1533, but it could have perhaps been Henry Dudley, the youngest Dudley son who survived to adulthood. Henry Dudley was old enough to accompany his father on his excursion against Mary's forces in 1553 and to be arrested and tried for treason, so he must have been born no later than the 1530′s. To complicate matters even further, the boy christened in 1537 could have been a son who did not survive to adulthood.

In the end, then, Guildford's age remains a muddle. We do know one thing for certain, however: his godfather was HOT . And he collected books. It doesn't get much better than that, ladies.

. And he collected books. It doesn't get much better than that, ladies.

September 5, 2011

Was Lady Jane Grey Precontracted to the Earl of Hertford?

In The Children of Henry VIII, Alison Weir writes that while John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, was planning for Lady Jane Grey to marry his son Guildford, "Jane was already betrothed to Edward Seymour, Lord Hertford, the fifteen-year-old son of the late Duke of Somerset, but her parents had no qualms about breaking this precontract." Other nonfiction accounts of Jane Grey make a similar claim, and a number of novelists have gone so far as to invent a romance between Jane and Edward Seymour.

Born on May 22, 1539, Edward Seymour was the heir of Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, who served as Lord Protector for the underage Edward VI. Beginning in 1547, when his father achieved his dukedom, young Edward Seymour was styled as the Earl of Hertford. The "romance" between him and Jane, two years his elder, can handily be dismissed as pure invention. But is there truth to the assertion that the two had a precontract of marriage?

In January 1549, Somerset's younger brother, Thomas Seymour, the Lord Admiral, was arrested for treason. Jane's father, Henry Grey, then the Marquis of Dorset, was deposed about what he knew of Thomas Seymour's activities. Thomas Seymour had acquired Jane's wardship and had promised to use his influence to help the Dorsets marry Jane to Edward VI, which had dangerously entangled Henry Grey with Thomas Seymour. Questioned by the Protector in 1549, Dorset seems to have tried to placate Somerset by offering his daughter as a bride for his son: "For the Maryage off your Graces Sune to be had with my Doghter Jane, I think hyt not met to be wrytyn, but I shall at all Tynes avouche my saying."

Somerset may well have wanted such a marriage for his eldest son. In his own deposition, the Marquis of Northampton reported, "Also when the sayd Lord Admirall came laste to London, he tolde me in hys owne Gallerye, that ther wolde be moch ado for my Lady Jane, the Lord Marques Dorsett's Dowghter; and that mi Lord Protector and my Lady Somerset wolde do what they colde to obtayne hyr of my sayd Lord Marques for my Lord of Hertforde." Somerset certainly had every reason to hope for a match between Jane and Hertford: aside from Jane's high rank, she was receiving a fine humanist education, which Somerset was also giving his own daughters. On a more cynical note, Somerset would later be accused of wanting to marry one of his own daughters to King Edward, and marrying Jane to Hertford would eliminate her as a rival for the king's hand.

Though various authors state that Somerset and Dorset were negotiating for Jane's marriage in 1550 or 1551, before Somerset's own arrest for treason in October 1551 and his execution in January 1552, I have yet to see any give a source for this story. Indeed, John ab Ulmis, writing from Jane's home of Bradgate on May 29, 1551, believed that Jane was to be "given in marriage to the king's majesty." There is, however, a hint that negotiations for a match between Jane and Hertford did take place at some point. On August 16, 1553, following the failed attempt to put Jane on the throne, the imperial ambassadors wrote: "As to Jane of Suffolk, whom they had tried to make Queen, [Queen Mary] could not be induced to consent that she should die; all the more because it had been found that there could be no marriage between her and Guilford, the son of the Duke [of Northumberland], as she was previously betrothed by a binding promise that entailed marriage to a servitor of the Bishop of Winchester." Could this refer to Hertford? Hertford had not been placed with the Bishop of Winchester, Stephen Gardiner, who had spent much of Edward VI's reign as a prisoner in the Tower and had been released only days before. In a letter to John Calvin, however, Thomas Norton reported that following the execution of Somerset, the thirteen-year-old Hertford had been sent to live with William Paulet, the Marquis of Winchester. It is possible, then, that the ambassadors confused the Bishop of Winchester with the Marquis of Winchester and that the reference to the unnamed servitor was to Hertford. The ambassadors, however, had their doubts as to whether there had been such a promise. They added, "It might be feared that the marriage to the Bishop of Winchester's servitor had been put forward hypocritically in order to save [Jane's] life."

If there was indeed a binding promise between Jane and Hertford, no further mention of it was made. Moreover, as Leanda de Lisle has pointed out, when the legality of Hertford's marriage to Jane's younger sister, Katherine, was investigated some years later, a precontract with Jane was not raised as a ground for invalidating it. Jane herself, in her letter to Queen Mary explaining the events of the summer of 1553, made no claim that her marriage to Guildford was invalid based on a previous betrothal. Indeed, she signed herself in the last days of her life as "Jane Dudley." All in all, it appears that if there were negotiations for the marriage of Jane and Hertford, they never were completed, and that when Jane married Guildford, she did so with no preexisting marital entanglements.

Sources:

Susan Doran, 'Seymour, Edward, first earl of Hertford (1539?–1621)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2010 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article..., accessed 5 Sept 2011]

Samuel Haynes, A Collection of State Papers Relating to Affairs in the Reigns of King Henry VIII, King Edward VI, Queen Mary, and Queen Elizabeth. Vol. I. London: William Bowyer, 1740.

Eric Ives, Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Mystery. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

Leanda de Lisle, The Sisters Who Would Be Queen: Mary, Katherine, and Lady Jane Grey. New York: Ballantine Books, 2008.

Hastings Robinson, Original Letters Relative to the English Reformation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1846 and 1847.

Royall Tyler, ed., Calendar of State Papers, Spain, vol. 11.

September 3, 2011

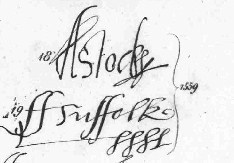

Signatures of Frances Grey and Adrian Stokes

I 've already posted this on my Facebook page, but I thought you might enjoy seeing it here if you don't frequent Facebook. These signatures of Frances, Duchess of Suffolk, and her second husband, Adrian Stokes, are from a 1559 deed they signed. They can be found in John Nichols' The History and Antiquities of the County of Leicester, which was published in four volumes over the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and which can be found online here.