Susan Higginbotham's Blog: History Refreshed by Susan HIgginbotham, page 2

July 25, 2023

New Research on Ernestine Rose

In researching my forthcoming novel on Ernestine Rose, I quickly found that biographers knew little about her family–only the names of her husband William Ella Rose and the three nieces that she named in her last will and testament. Knowing that genealogical information is far more accessible now than it was to her biographers, I set off to discover what I could. To my delight, I managed to identify Ernestine’s parents, four of her siblings, and one of her two children–and stumbled across a secret as well. (Hint: William Ella Rose, Ernestine’s beloved husband, was her second husband.) After all this digging, I decided to publish my research in a peer-reviewed article. I was also able to trace William Rose’s ancestry back to the seventeenth century–not bad considering how common his surname is.

Many of the records mentioned in the article can be found here for those with access to Ancestry USA. I am happy, however, to share any records that are not available there.

Incidentally, although none of Ernestine Rose’s New York City residences have survived (as far as I know), several of her lodgings in England remain. In 1871, the Roses lived at 24 Paragon in Bath. (Decades before, Jane Austen had visited an aunt at 1 Paragon.)

July 15, 2023

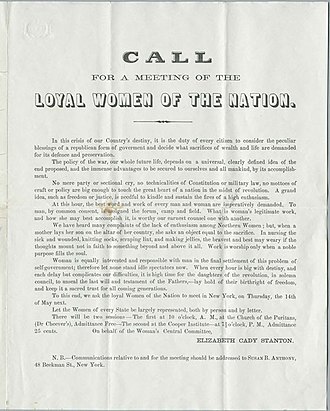

Stanton and Anthony Caught Up in the Draft Riots

National Portrait Gallery: Stanton and Anthony photographed by Napoleon Sarony ca. 1870

National Portrait Gallery: Stanton and Anthony photographed by Napoleon Sarony ca. 1870In July 1863, the infamous “draft riots” roiled New York. Among those caught up in the violence were the two people most associated with the nineteenth-century women’s rights movement: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s husband, Henry Stanton, had been appointed Deputy Collector of the New York Custom House in 1861. Elizabeth Cady Stanton seized this opportunity to move from Seneca Falls to the metropolis with her family. In 1863, the family was living at 75 West 45th Street.

To their frustration, women’s rights advocates had paused their activities during the Civil War, but in 1863, Stanton and Anthony conceived the Woman’s National Loyal League, to press for the expanded emancipation of slaves. As secretary of the organization, Anthony established an office at the Cooper Institute and lodged with the Stanton family.

On July 13, 1863, the draft riots, which would last for a terrifying four days before being put down with the aid of Union troops, began with an attack on the assistant provost marshal’s office at Third Avenue and 47th Street. Soon the mob began to vent its hostility on New York’s blacks, killing at least ten as well as a white woman defending her mixed-race child. Many more fled the city, some never to return. Among the rioters’ targets was the Colored Orphan Asylum, which they burned to the ground, although the children escaped. Estimates of the total number of people killed in the riots vary, but the official toll was 119.

Susan B. Anthony wrote to her family on July 15, 1863:

“These are terrible times. The Colored Orphan Asylum which was burned was but one block from Mrs. Stanton’s, and all of us left the house on Monday night. Yesterday when I started for Cooper Institute I found the cars and stages had been stopped by the mob and I could not get to the office. I took the ferry and went to Flushing to stay with my cousin, but found it in force there. We all arose and dressed in the middle of the night, but it was finally gotten under control.”

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, writing to Ann Smith, the wife of her cousin Gerrit Smith, from Johnstown, New York, on July 20, 1863, gave a more detailed description of the violence, during which her son Daniel (“Neil”) was seized by the mob as a “three-hundred-dollar fellow”—meaning that he could avoid the draft by paying for a substitute:

“Dear Cousin Nancy,-

“Last Thursday I escaped from the horrors of the most brutal mob I ever witnessed, and brought my children here for safety. The riot raged in our neighborhood through the first two days of the trouble largely because the colored orphan asylum on Fifth Avenue was only two blocks away from us. I saw all those little children marched off two by two. A double portion of martyrdom has been meted out to our poor blacks, and I am led to ask if there is no justice in heaven or on earth that this should be permitted through the centuries. But it was not only the negroes who feared for their lives. Greeley [Horace Greeley, the editor of the New York Tribune] was at Doctor Bayard’s a day and night for safety, and we all stayed there also a night, thinking that, as Henry, Susan, and I were so identified with reforms and reformers, we might at any moment be subjects of vengeance. We were led to take this precaution because as Neil was standing in front of our house a gang of rioters seized him, shouting: ‘Here’s one of those three-hundred-dollar fellows!’ I expected he would be torn limb from limb. But with great presence of mind he said to the leaders as they passed a saloon: ‘Let’s go in, fellows, and take a drink.’ So he treated the whole band. They then demanded that he join them in three cheers for ‘Jeff Davis,’ which he led with apparent enthusiasm. ‘Oh,’ they said, “he seems to be a good fellow; let him go.’ Thus he undoubtedly saved his life by deception, though it would have been far nobler to have died in defiance of the tyranny of mob law. You may imagine what I suffered in seeing him dragged off. I was alone with the children, expecting every moment to hear the wretches thundering at the front door. What did I do? I sent the servants and the children to the fourth story, opened the skylight and told them, in case of attack, to run out on the roof into some neighboring house. I then prepared a speech, determined, if necessary, to go down at once, open the door and make an appeal to them as Americans and citizens of a republic. But a squad of police and two companies of soldiers soon came up and a bloody fray took place near us which quieted the neighborhood.”

Illustrated London News

Illustrated London NewsStanton’s fears that her house might be targeted, though unrealized, were not unfounded. Julia Gibbons, whose abolitionist family’s home had been vandalized earlier that year after the family illuminated it in honor of the Emancipation Proclamation, wrote to her mother on July 15, “The rioters yesterday gutted our house completely.” Her father, James Sloan Gibbons, added, “I had a revolver in my desk. Left the house only thirty minutes to get a paper, and on my return, the mob had possession. I went in among them and up to my desk, making room, as I entered towards the library, for the villain who had our mattress; but seeing that the place was fully in possession of the mob, with my pistol in hand, I could go no further. . . . Those grand widowed mothers . . . who sent their only, or all their sons, to the war, have mortal and incurable wounds—we, only a scratch. I am ashamed to have deserved no more.”

Sources:

Iver Bernstein, The New York Draft Riots

Sarah Hopper Emerson, ed., Life of Abby Hopper Gibbons: Told Chiefly Through Her Correspondence

Lori Ginzburg, Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Leslie M. Harris, “The New York City Draft Riots of 1863” (online excerpt from In the Shadow of Slavery)

Ida Husted Harper, The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony

George Theodore Stanton and Harriot Stanton Blanch, eds., Elizabeth Cady Stanton as Revealed in Her Letters, Diary, and Reminiscences

July 7, 2023

Within the Golden Ball of St. Paul’s

In nineteenth-century London (and apparently into the 1960s), it was possible for the venturesome to climb all the way to the interior of the golden ball surmounting St. Paul’s Cathedral in London (right below the cross). One of those who made the effort was the intrepid feminist Ernestine Rose, who along with her husband was traveling abroad in the summer of 1856. Ernestine wrote in a letter to the Boston Investigator on July 6, 1856, “In St. Paul’s, after seeing the library, we went up to the Whispering Gallery, the clock, and the ball under the cross. It is 510 feet from the crypt; twelve persons can stand in it, but from the street it looks as small as the head of a child.”

Charles Dickens, Jr. (as you may have guessed, the eldest son of the Inimitable) wrote in his 1879 Dictionary of London, “[T]he clock is worth a visit, though we do not advise persons with delicate ears to approach it about the time of its striking the hour. Above is a stone gallery, whence, if the day be clear, a fair view of London and the Thames may be obtained; but if the visitor be still more ambitious, he may ascend more winding stairs, and reach the golden gallery far away above the dome. Thence upwards he may climb more steps until he reach the ball, an expedition which may be undertaken once in youth, but hardly ever again.” (Ernestine Rose, it should be noted, was well into middle age.)

Writing in the magazine Little Folks in 1883, James A. Manson left this daunting description of the ascent:

“Only fifty-six more steps, making altogether 560 steps from the marble pavement beneath, and we arrive at the Golden Ball. This part of our journey demands the utmost care, and I am fully prepared to corroborate the guide-book, which naïvely asserts that our goal ‘is reached with some difficulty, especially by ladies.’ The fifty-six steps in question are composed of three wooden ladders, very upright, and at least one of which has but a single banister, the other consisting of a rope. Here you will find yourself within some cross iron-work, and when you have managed to climb this, you will be able to look into the dark jaws of the Golden Ball. This immense ornament is six feet in diameter, and two and a half tons in weight. It will hold, so I have heard, four, or even more, people; but nobody who has ascended thus far need run the risk of climbing into it. On the top of the ball stands the famous glittering cross, which weighs one ton and a half, and is thirty feet high. Of ‘queer’ places it would be hard to discover one better befitting this epithet than the Golden Ball of St. Paul’s, and its approach. The access is so dark, and the ladders so steep, that great care is needed to avoid making a false step. These things make timid folk more timid, and cause even the stouter-hearted to be unusually cautious.

“In due course the return journey is resumed, and though going downward is much easier than climbing up, we are not displeased to find ourselves once more safe and sound on terra firma.”

None too soon, methinks.

(Engraving by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd from Wikipedia)

May 8, 2023

An 1860 Letter From John Brown, Jr.

A while back, I was fortunate enough to acquire this letter written by John Brown, Jr., the oldest son of the abolitionist John Brown, just a few months after his father’s ill-fated raid on Harpers Ferry and his subsequent execution. John writes from his Ohio home to his family in North Elba, New York: his married sister, Ruth Brown Thompson; his stepmother, Mary; his half-sisters, Annie, Sarah, and Ellen; his half-brother Salmon Brown; and his widowed sister-in-law Isabel “Bell” Brown. Presumably he anticipated that the letter would be handed around freely; hence the “cousins.”

John Jr. had not been to Harpers Ferry, but had hidden and shipped weapons for his father. After the raid, he refused to testify before a congressional committee investigating the incident.

In his letter, John Jr. refers to the death of Martha, the widow of his half-brother Oliver. Martha, whose husband was killed during the raid, died just weeks after giving birth to a short-lived girl. Watson Brown, another half-brother, also perished during the raid. His widow, Bell, had given birth to Watson’s son, Freddy, not long before the raid. (Sadly, Freddy would die as a toddler.)

“Mr. Redpath” was journalist James Redpath, who was writing a biography of John Brown. Barclay Coppoc and Owen Brown (John Jr.’s younger brother) had been among John Brown’s men but had not gone to Harpers Ferry, having been left behind in Maryland to guard a stash of weapons. Realizing that their cause was lost, they escaped into the hills. Barclay Coppoc, whose brother was executed for his role in the raid, later joined the Union Army. He died in a train accident that may have been the result of Confederate sabotage. Jeremiah was Jeremiah Brown, a younger half-brother of the elder John Brown. One of the few prosperous members of the Brown family, Jeremiah was living in Hudson, Ohio.

Annie and Sarah, John Jr.’s half-sisters, attended Franklin Sanborn’s school in Concord, Massachusetts, although Annie, traumatized by recent events, stayed for only a short time before coming back to North Elba. She returned the following year, however. John Jr. and Wealthy’s son Johnny had broken his leg the year before.

The rumored move to Worcester that John Jr. feared never took place, nor did he and his wife and son, Wealthy and Johnny, move to North Elba. Instead, John Jr. and his family settled in Put-in-Bay, Ohio. The others moved at various times to California. All remained there except for Salmon Brown, who later moved to Portland, Oregon, and Jason Brown, who returned in his old age to Ohio.

In his letter, John quotes from William Cowper’s 1785 poem “The Task.”

Photo from my collection

Photo from my collectionDorset Ashtabula Co. O[hio]

March 26th 1860

Dear Sister Ruth Mother Brothers Sisters and Cousins

I have yours informing me of the death of our dear Sister Martha. My heart bleeds again, though my Faith assures me that she is now in that better land, where she finds “rest” on the bosom of love. You say she was something of a believer in Spiritualism. The name of “Spiritualist” conveys an idea so indefinite that almost every one gets a different idea from it. If to believe that Death is but a stepping stone to a higher mode of existence that we take with us into that state of being all that we now are, except the grosser material form—that, after death the disembodied are yet near to earth and earthly friends interested in them in proportion to the strength of their love, and often communicating their thoughts and emotions, especially through silent impression—that in that state of being the spirits of the departed are subject to the laws of progression and retrogression as here; I say if to believe this is to be “a spiritualist” then I am one. If to believe all that comes to us is labeled “from spirits,” then I am not one.

You will see by the paper I sent you that Mr. Redpath, Barclay Coppoc, and Owen are with me. The two latter are now absent from here for a few days but will soon return.

The negative of Oliver’s Photograph was accidentally broken so we shall now have to depend on a copy. Jeremiah took the one I have of Oliver to Cleveland and had copies taken which are very good though much darker than the original picture. If I can procure one I will send to you.

I am very glad that Annie and Sarah are at Mr. Sanborn’s school. Have sent Annie a paper also; will write her soon. I should write much oftener if it were not for the constant stream of company we have and so much besides to do.

Mr. Redpath said there has been some talk of our folks moving from North Elba and establishing some where in the vicinity of Worcester Mass. I do hope not. From the necessities of the case the family would be forced into a class of society which in a pecuniary respect at least they could not stand with as equals. The desire to be equal so far as externals go would be “irrepressible” and would insensibly lead into an extra expense of living which would not be counter-balanced by the advantages which some may fancy would be gained by such change of location. Our family were not made to shine in the drawing-rooms of wealth and distinction—the wild and rugged “Adirondacks” with their pure air, clear streams and placid lakes constitute our most natural surroundings. It is so for me and mine at least.

Every day serves to strengthen my determination to make my home among those granite peaks as soon as possible. I sigh “for a lodge in some vast wilderness; some boundless contiguity of shade.”

I am very anxious to obtain a picture of Watson, where can I? Dear Sister Bell, I want to see you and your little son and all of you, so much more than I can say. But I must wait ‘till I’m better able to meet the expense of the journey to see you.

Johnnie is now able to walk quite well again, though he still favors that leg some yet. –Wealthy will write as soon as she can take a spare moment. Our comers and goers keep her too busy.

My warmest love to all, and believe me always

Your affectionate son and brother

John Brown Jr.

February 24, 2023

Mother Knows Best

Ernestine Rose, the subject of my novel-in-progress, was a contemporary of Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Ernestine was much closer to Susan B. Anthony, who accompanied Ernestine to Washington, D.C., in 1854, defended Ernestine against those who would have kept her off the platform because of her open atheism, and visited Ernestine, a recent widow, in London in 1883. Ernestine was also on good terms with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, however, and the two women were instrumental in getting the New York State legislature to pass an act in 1848 granting married women certain property rights.

While researching my novel, I came across this anecdote by Margaret Stanton Lawrence, a daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. It is contained in a typescript, “Who Was Elizabeth Cady Stanton? My Mother, part. 2,” at Vassar College’s digital library.

“At one time mother was much troubled at the way her boys swore, so she took council with sweet little Lucretia Mott, who was her guest, and with Miss [Susan B.] Anthony . . . So when the family gathered for the next meal, Lucretia, in her trim white Quaker cap and ‘kerchief, said ‘Elizabeth, may I give thee some of this damn chicken?’ The boys all looked amazed, but as none of the ladies cracked a smile, and as the oaths, from the lips of the three women, flew thick and fast, the youngsters joined in and enjoyed the fun. This was kept up for three meals; at the fourth meal, however, some distinguished guests were present, who had been let into the secret. . . .

” . . . The boys were distressed, as they served the guests [as they had been taught by their mother to do in lieu of reliable servants], to see the look of disapproval on Governor [William] Seward’s and Gerrit Smith’s faces as their hostess and her two Quaker friends ripped out their oaths. So when they got their mother alone, they gathered around her and with tears in their eyes said: ‘Oh, mother, what will the Governor and Cousin Gerrit think, hearing you swear like that?’ ‘Well,’ she said, ‘you boys all do it, and so we thought we would also; don’t you like to hear us? . . . If you boys will stop swearing, I will also.’ And they did.”

(Photo of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and her foul-mouthed kids from Wikipedia.)

December 21, 2022

Moving Day: New York Style

Early feminist Ernestine Rose, the heroine of my novel-in-progress, and her husband William changed residences multiple times during the more than 30 years they resided in New York City, which means that they frequently had to cope with what was known as Moving Day.

Harpers Weekly, 1859

Harpers Weekly, 1859Until well into the 20th century, most residential leases in New York City expired on May 1, meaning that on that day, much of the population would be changing houses simultaneously. Diarist George Templeton Strong wrote on May 1, 1844, “Never knew the city in such a chaotic state. Every other house seems to be disgorging itself into the street; all the sidewalks are lumbered with bureaus and bedspreads to the utter destruction of their character as thoroughfares, and all the space between the sidewalks is occupied by long processions of carts and wagons and vehicles omnigenous laden with perilous piles of moveables.”

1856 cartoon via Wikipedia

1856 cartoon via WikipediaVisiting Englishwoman Frances Trollope wrote in her Domestic Manners of the Americans: “On the 1st of May the city of New York has the appearance of sending off a population flying from the plague, or of a town which had surrendered on condition of carrying away all their goods and chattels. Rich furniture and ragged furniture, carts, waggons, and drays, ropes, canvas, and straw, packers, porters, and draymen, white, yellow, and black, occupy the streets from east to west, from north to south, on this day. Every one I spoke to on the subject complained of this custom as most annoying, but all assured me it was unavoidable, if you inhabit a rented house. More than one of my New York friends have built or bought houses solely to avoid this annual inconvenience.”

Moving Day (in Little Old New York), artist unknown, ca. 1827 (The Met)

Moving Day (in Little Old New York), artist unknown, ca. 1827 (The Met)The New York Times observed on April 30, 1873, “To one class alone is the day an era of rejoicing. It is the carman’s harvest. For once his nag is looking spruce and hearty, his truck is newly painted, and his face beams with smiles.”

In 1849, the New York Atlas produced this ditty, which was picked up by other newspapers, in honor of the occasion:

July 23, 2022

Girl-Watching on Fifth Avenue

I couldn’t resist this charming poem and accompanying illustrations, apparently given as a contribution to a scrapbook in the early 1860s. (Sadly, I have only this page, not the rest of the scrapbook.)

In case you have difficulty reading the poem, here’s a transcription:

I’ve been requested in this book

To write lines old or new

By one I gained a knowledge of

On the 5th Avenue.

(The street where Harry Alxxn (?) walks

On pleasant afternoons

With sundry showy specimens

Of young female Balloons.)

‘Tis thought the ladies seldom love

A specimen of “Mose”,

But some an interest take I fear

In “Metamora Hose.”

For fear someone the hose carthouse

To find would have to search

It stands directly opposte

The Twenty-First Street Church

And in the window o’er the door

Young men on the alert

Look out, I think, with longing eyes

To get a chance to flirt.

‘Twas in this walk of flirts and fops

We two exceptions met,

And though our acquaintance there began

We do not feel regret.

No, though our old friend Mrs. Green

May smile and call me flat,

If another chance I should have

I’d wave and touch my hat.

“Mose,” in case you were wondering (I certainly was) refers to “Mose the Fireboy,” a legendary character associated with the “B’hoy” culture of the Bowery. He was the hero of several plays and novels; the illustration below, from the Harvard Theater Collection via Wikipedia, shows him as played by actor Frank Chanfrau. The “Metamora Hose” was a volunteer fire squad located at the corner of 21st Street and Fifth Avenue.

July 9, 2022

“Hidden Mothers”: Hiding in Plain Sight in Victorian Photography

A while back, I posted on the solemn subject of Victorian postmortem photography. Here’s a more lighthearted aspect of nineteenth-century photography: the phenomenon of what collectors have nicknamed the “hidden mother.”

Contrary to legend, having a picture taken didn’t mean that the subject had to stand still for minutes at a time, except in the earliest days of photography. Yet even with comparatively short exposure times, a wiggly subject could mar a photograph, and what subjects were squirmier than infants and young children? So if a parent wanted an image of his or her little darling by himself or herself, and the child was either too young, too nervous, or just plain too ornery to cooperate, an adult–such as a parent, a servant, or a photographer’s assistant–would be called to duty.

Cartoon from the May 5, 1888, Harper’s Bazar (spelled then without the extra “a”)

Cartoon from the May 5, 1888, Harper’s Bazar (spelled then without the extra “a”)The photograph below is the epitome of the “hidden mother” genre, with the adult obscured by a drape of some sort. As they are the strangest-looking to our eyes, they are the most popular among collectors. It’s likely, though, that the parent who received this would mentally screen out the covered figure and focus only on the child.

Other photographers and clients chose a less suffocating approach by simply obscuring the adult as much as possible through the matte.

And then there were those who didn’t do much hiding at all, leaving stray hands, feet, and other vestiges of the adult in the photograph.

Why, some have asked, didn’t the Victorians simply photograph parent and child together, eliminating the need for subterfuge? Well, of course, they did–there are numerous nineteenth-century photos showing parents with their babies or toddlers, such as this lovely couple with their slightly blurry child.

But just as is the case now, there were proud mamas and papas who insisted on a separate photo of their offspring–and in an imperfect world, the “hidden mother” was the most practical solution. As the caption on back indicates, “The best that could be done with such a fidgety young gentleman.”

(All photos from my collection. Thanks to Beverly Wilgus for calling my attention to the cartoon.)

April 21, 2022

Robert Dale Owen’s “Marriage Declaration.”

Wisconsin Historical Society

Wisconsin Historical SocietyOn April 12, 1832, in New York City, thirty-year-old Robert Dale Owen married nineteen-year-old Mary Jane Robinson. The son of reformer and socialist Robert Owen, Robert Dale Owen shared his father’s views and was a writer and a publisher. He also served in the Indiana legislature and Congress, was the American ambassador to the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies during the Pierce administration, served on the Freedman’s Inquiry Commission during the Civil War, advocated for the right of women to vote, and was instrumental in establishing the Smithsonian Institution. The year before his marriage, he had published “Moral Physiology,” a treatise on birth control, in which he wrote, “That chastity which is worth preserving is not the chastity that owes its birth to fear and to ignorance. If to enlighten a woman regarding a simple physiological fact will make her a prostitute, she must be especially predisposed to profligacy.”

New York Academy of Medicine

New York Academy of MedicineIn letters to Nicholas Trist written from Mary Jane’s family home in Petersburg, Virginia, Robert praised his fiancée’s mathematical abilities and noted that she was a recent convert to vegetarianism, having read Shelley’s “Queen Mab.” He described Mary Jane as having “a degree of originality of thought & independence of character which I had never, I believe, met with in a girl of nineteen before.” For her part, Mary Jane had attended a lecture by Robert and told her sister when she came home that she had seen the man she intended to marry.

Having drawn up a marriage contract, Robert and Mary Jane were married by a justice of the peace. A friend who attended the ceremony on a half-hour’s notice stated that there was nothing in the couple’s dress that would distinguish them as a groom or bride. Before the ceremony, Robert wrote the following letter, which he circulated among his friends:

NEW YORK, Tuesday, April 12, 1832.

This afternoon I enter into a matrimonial engagement with Mary Jane Robinson, a young person whose opinions on all important subjects, and whose mode of thinking and feeling, coincide, in so far as I may judge, more intimately with my own, than do those of any other individual with whom I am acquainted.

We contract a legal marriage, not because we deem the ceremony necessary to us, or useful, in a rational state of public opinion, to society; but because, if we became companions without a legal ceremony, we should either be compelled to a series of dissimulations which we both dislike, or be perpetually exposed to annoyances, originating in a public opinion, which is powerful though unenlightened; and whose power, though we do not fear or respect it, we do not perceive the utility of unnecessarily braving. We desire a tranquil life, in so far as it can be obtained without a sacrifice of principle.

We have selected the simplest ceremony which the laws of this state recognize, and which, in consequence of the liberality of these laws, involves not the necessity of calling in the aid of a member of the clerical profession, a profession the credentials of which we do not recognize, and the influence of which we are led to consider injurious to society. The ceremony, too, involves not the necessity of making promises regarding that over which we have no control, the state of human affections in the distant future, nor of repeating forms which we deem offensive, inasmuch as they outrage the principles of human liberty and equality, by conferring rights and imposing duties unequally on the sexes.

The ceremony consists simply in the signature, by each of us, of a written contract in which we agree to take each other as husband and wife according to the laws of the State of New York, our signatures being attested by those friends who are present.

Of the unjust rights which, in virtue of this ceremony, an iniquitous law tacitly gives me over the person and property of another, I cannot legally, but I can morally divest myself. And I hereby distinctly and emphatically declare that I consider myself, and earnestly desire to be considered by others, as utterly divested, now and during the rest of my life, of any such rights, the barbarous relics of a feudal and despotic system, soon destined, in the onward course of improvement, to be wholly swept away; and the existence of which is a tacit insult to the good sense and good feeling of this comparatively civilized age.

I put down these sentiments on paper this morning as a simple record of the views and feelings with which I enter into an engagement, important in whatever light we consider it; views and feelings which I believe to be shared by her who is this afternoon to become my wife.

Robert Dale Owen.

I concur in these sentiments.

Mary Jane Robinson

Don Blair Collection at the University of Southern Indiana’s David L. Rice Library

Don Blair Collection at the University of Southern Indiana’s David L. Rice LibraryRobert and Mary Jane had six children before Mary Jane’s death in 1871. Robert remarried in 1876 and died the following year.

Sources:

Boston Investigator, June 15, 1832

Richard William Leopold, Robert Dale Owen: A Biography (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1940).

Rosamond Dale Owen, “Robert Dale Owen and Mary Robinson,” in Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan Brownell Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage, and Ida Husted Harper, eds., History of Woman Suffrage: 1848-1861 (New York: Fowler & Wells, 1881).

Louis Martin Sears, “Some Correspondence of Robert Dale Owen.” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Dec., 1923, Vol. 10, No. 3 (Dec., 1923), pp. 306-324.

March 19, 2022

Goodreads Giveaway

Do you have a Kindle and a Goodreads account? If so, now is your chance to win a free Kindle edition of John Brown’s Women! Entry is free, as are Goodreads accounts; if you enter the book will be added to your “Want to Read” shelf, and if you win, the book will be sent to your designated device. That’s all! Giveaway ends on March 31.

John Brown’s Womenby Susan Higginbotham

John Brown’s Womenby Susan HigginbothamGiveaway ends March 31, 2022.

See the giveaway details at Goodreads. Enter Giveaway