Susan Higginbotham's Blog: History Refreshed by Susan HIgginbotham, page 3

January 19, 2022

Postmortem Photography: An Appreciation

WARNING: This post contains photos of dead persons, though none are sensational or gruesome. If you are upset by such things, please skip this post.

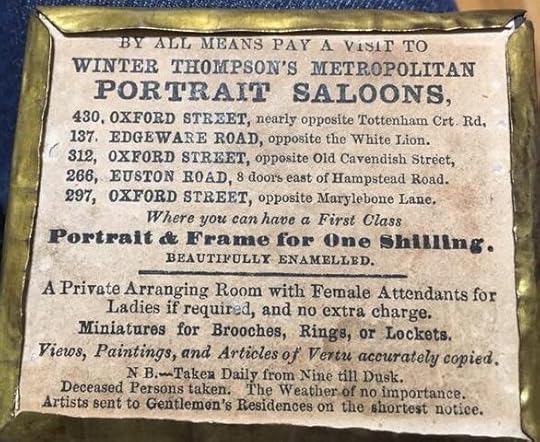

Advertisement on back of cased photo

Advertisement on back of cased photoA few years back, I began collecting nineteenth-century photographs. In doing so, I have acquired a number of postmortem photographs. I find them moving and in many cases quite beautiful. Except for one, all of the photos in this post are from my own collection. I have included several from the twentieth century, for no better reason than that I like them.

Unfortunately, the Internet has encouraged the proliferation of a number of myths about these photographs, chiefly the notion that the Victorians posed their dead to appear alive, using stands, wires, hooks, or any ingenious and/or weird device you care to name. In fact, the stands visible in many photographs from the era were used to help living people remain still. Nor did the Victorians paint eyes on corpses, as claimed in some articles; they did, however, often touch up eyes on photos, usually because a living subject blinked or had blue eyes that did not photograph well. Most postmortem photos from the era show the subject in dignified repose, although some younger children are held by a parent and some subjects are placed in a seated position. A very few postmortem photographs depict the subject being held up by another person. The best rule of thumb is that if a person looks alive, he or she is; if a person looks awkwardly posed, he or she was awkwardly posed.

[image error]The articles that feed the public misinformation often invent elaborate explanations as to why the Victorians took photos of the dead. Some claim that photography was so expensive that families of middling or no means would splurge for a photograph only when a loved one died. In fact, photography, though like other new technologies expensive at the outset, became more and more affordable as the century went on. As one photographer commented to a Chicago newspaper in 1885, “Photographs are so cheap now that nearly everybody gets them, and it is but rarely that death overtakes a man who has not left a negative behind him.” Anyone who was too poor to have a photo of a living family member would likely be too poor to have one taken of a dead one. What is true, though, is that many postmortem photos are of young children, whose parents may not gotten around to taking a photo or never had a chance to do so while the child was alive.

Others, especially those who regard the Victorians as dreary, prudish ghouls, attribute the photos to the era’s preoccupation with death. Yet the Victorians also took photographs of pets, livestock, natural scenes, nudes, graduates, wedding parties, paintings, inanimate objects, ships, buildings, and monuments—pretty much any subject you can think of. Postmortem photos, though not rare, are a distinct minority of the many, many photographs that survive from the nineteenth century. And while the practice of postmortem photography began in the nineteenth century, it certainly did not end there. Postmortem photographs continued to be taken throughout the twentieth century and are still taken today; indeed, a volunteer organization specializes in photographing stillborn or short-lived infants for their grieving parents.

The best explanation for these photos would seem to be the simplest: the Victorians took photographs of their dead because they could. Many, of course, were content to remember their loved one as they had appeared in life, and never felt the need for that final photo. Others did, like abolitionist author Harriet Beecher Stowe, who lost a son, Samuel Charles Stowe, in the summer of 1849. Stowe wrote to her husband, “My Charley—my beautiful, loving, gladsome baby, so loving, so sweet, so full of life and hope and strength—now lies shrouded, pale and cold, in the room below. Never was he anything to me but a comfort. He has been my pride and joy. Many a heartache has he cured for me. Many an anxious night have I held him to my bosom and felt the sorrow and loneliness pass out of me with the touch of his little warm hands. Yet I have just seen him in his death agony, looked on his imploring face when I could not help nor soothe nor do one thing, not one, to mitigate his cruel suffering, do nothing but pray in my anguish that he might die soon.” This daguerreotype of little Charley, owned by Radcliffe’s Schlesinger Library, is a poignant commemoration of his short life.

Held by Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe College

Held by Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe CollegeStowe’s fellow abolitionist, William Lloyd Garrison, also suffered the death of a son, Charles Follen Garrison, in 1849. On June 20, 1849, he wrote to a friend, Elizabeth Pease, about his loss: “You have the daguerrian likenesses of Fanny [living] and Lizzie [a postmortem photo]—I wish it were in my power to send you one of Charley. But we never had his taken, though we thought of doing so a hundred times. Why I did not have one taken before his interment, I can hardly tell; perhaps because he was more altered in appearance than Lizzie. But I now lament that I did not get an artist to make an attempt.”

Garrison concluded, “In the cycle of ages, the death of one person–of millions of persons–however beloved, or whatever their characteristics, is a very insignificant event; but in its sphere and immediate relationships, it is weighty, trying, momentous.” That, I believe, is what these photographs capture.

Sources:

Annie Fields, ed., Life and Letters of Harriet Beecher Stowe

Walter M. Merrill, ed., No Union With Slave-Holders: The Letters of William Lloyd Garrison, Vol. III.

December 19, 2021

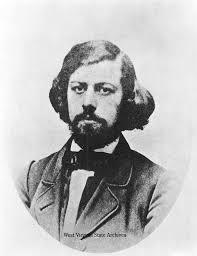

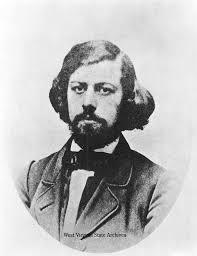

August Bondi

One of John Brown’s followers in Kansas was August Bondi (1833-1907), a Viennese Jew whose family had immigrated to the United States in 1848 and settled in St. Louis. Just before his family left Vienna, Bondi participated in the student uprising in that city.

In 1855, eager for adventure, Bondi came to the territory of Kansas, where he soon met John Brown’s sons and later Brown himself. Falling ill that same year, he went to Missouri to recuperate, but returned to Kansas in May 1856, just in time to stumble upon the encampment of the Browns, who had turned out to defend the city of Lawrence from an attack by pro-slavery forces. Learning that the city had already been sacked, John Brown proceeded to order the killings of five pro-slavery settlers. Young Bondi did not participate, but later said that he had been directed to stay behind to carry messages to the men’s families. He was on hand, however, for the battle of Black Jack, the first armed clash between pro- and anti-slavery forces in Kansas, where John Brown and his men defeated a force led by Henry Pate. Bondi recalled,

When we followed Captain Brown up the hill towards the “Border Ruffians'” Camp, I next to Brown and in advance of Weiner [Theodore Weiner, another Jewish immigrant], we walked with bent backs, nearly crawled, that the tall dead grass of the year before might somewhat hide us from the “Border Ruffian” marksmen, yet the bullets kept on whistling. Weiner was 37 and weighed 250 lbs. I, 22 and lithe. Weiner puffed like a steamboat, hurrying behind me. I called out to him, “Nu, was meinen Sie jetzt?” (Well, what do you think of it now?) His answer, “Was soll ich meinen? (What should I think of it?) ‘Sof odom muves” (Hebrew for “the end of man is death,” or, in modern phraseology, “I guess we’re up against it”).

In spite of the whistling of the bullets, I laughed when he said, “Machen wir den alten Mann sonst broges.” (Look out, or we’ll make the old man [Brown] angry.)

John Brown’s list of participants at Black Jack (including “A Bondy”)

John Brown’s list of participants at Black Jack (including “A Bondy”)When Pate surrendered, Bondi asked him for his powder flask, which he kept, along with the 1812 musket he had carried, “like a sacred relic.” In the days after the battle, Bondi recalled in his autobiography, he and Brown’s other youthful followers discussed a plan to declare the territory of Kansas independent of the United States, but Brown, overhearing the talk, stifled it with the words, “Boys, no nonsense.”

Later in the summer, Bondi recalled, Brown and his men raided, ironically enough, the home of a pro-slavery militia captain named “Capt. Brown.” Bondi recalled, “We took his cattle, about fifty head, and while searching the house for clothing, a young woman, his daughter, just berated the abolitionists for all out. Amongst her other remarks, I caught this one: ‘No Yankee abolitionist can ever kiss a Missouri girl.’ As she uttered these words, I spied a litter of hound pups in the corner of the kitchen. I picked up one and said, ‘I would kiss a hound pup before I would kiss a Missouri girl,’ and I kissed the pup.”

Bondi last saw Brown at the end of September 1856: “[J]ust before sunup, I noticed a lonely rider crossing the Branch and coming up the California trail to the house. As he came nearer I saw it was Capt. Brown. He stopped without dismounting and told me that he was on the road to Iowa where his people intended to winter. . . . [A]s the sun rose we shook hands and he went on.” Later, Bondi eulogized Brown thusly:

We were united as a band of brothers by the love and affection towards the man who, with tender words and wise counsel, in the depths of the wilderness of Ottawa Creek, prepared a handful of young men for the work of laying the foundation of a free commonwealth. He constantly preached anti-slavery. He expressed himself to us that we should never allow ourselves to be tempted by any consideration, to acknowledge laws and institutions to exist as of right, if our conscience and reason condemned them.

In Leavenworth in May 1860, Bondi met an old acquaintance, who introduced him to a friend named George Einstein. Bondi stayed overnight at the Einstein residence, where he met George’s sister, Henrietta. After just a few hours’ acquaintance, he proposed via letter. The couple were married at the end of June. In due time they had a baby, whom they transported in a converted box due to the lack of a proper baby carriage in the territory. This was to be the first of ten children born to the couple.

Bondi fought for the Union in the Civil War and was wounded; his war journal recounts not only military deeds but his return of a green silk dress to a ladies’ academy from which it was stolen and a truce that allowed Yankees and Rebels to collect melons from a patch. After the war, Bondi worked variously as a merchant, an attorney, and a judge. Eventually, he and his family settled in Salina, Kansas, where, Bondi noted, his wife and his mother hosted the first children’s party held in that town. In his old age, he paid a visit abroad, writing, “From the moment I reached Europe I found it to be a country of large beer glasses and small coffee cups.”

While visiting St. Louis on September 30, 1907, Bondi collapsed in the street with a heart attack. His funeral, held at Salina’s Masonic Temple, included both Jewish and Masonic rites. Later, his children published his autobiography, a wonderful blend of political and martial exploits, family history, and minutiae.

Sources:

August Bondi, Autobiography of August Bondi, Wagoner Printing Company, 1910.

Leon Hühner, “Some Jewish Associates of John Brown,” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society, No. 23 (1915), pp. 55-78.

(Images from the Kansas Memory site.)

November 28, 2021

The Death of Francis J. Meriam

On November 28, 1865, Francis Meriam, one of John Brown’s men, died in a New York City boardinghouse at age 28.

The grandson of Francis Jackson, a prominent Boston abolitionist, Meriam had been one of those left behind in Maryland on guard duty while John Brown and most of his other men proceeded to Harpers Ferry. Realizing that all was lost, Meriam and others escaped through the mountains, with Meriam ultimately boarding a train near Chambersburg and ending up in Canada. Physically frail, blind in one eye through a youthful accident, and mentally erratic, Meriam nonetheless served in the Union army. In 1863, he was with the 21st U.S. Colored Infantry, for which he served as acting captain. The following year, he enlisted as a private with the 59th Massachusetts Infantry and was wounded in the right leg at Spotsylvania in May 1864, after which he was hospitalized for months. During the war, he had married Minerva Caldwell, said to have been of mixed race, but the marriage foundered. Minerva graduated from the New England Female Medical College in Boston in 1865.

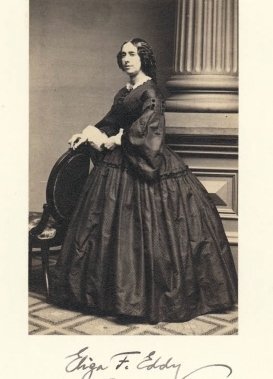

Little is known about Meriam’s postwar activities, and for years his former associates were uncertain as to exactly what had happened to him. Richard Hinton, an early biographer of Brown, believed in 1899 that Meriam had died “in Mexico of battle wounds.” But this letter held at Harvard’s Houghton Library, written by his mother, Eliza Jackson Eddy, to Wendell Phillips from Rome on April 25, 1866, tells the actual story:

“You probably had not heard of the death of Francis when you wrote. I read a letter from Lizzie [Francis’s sister] in March stating that it had been so long a time that they had heard nothing from Francis that they all felt uneasy, that brother James [Jackson] went on to New York, to the house where he was last boarding, and the description they gave of a person having suddenly died there of heart disease, corresponded so much with that of Francis that he showed them a photograph & they said he was the same; he had assumed another name, which his wife had heard him mention as intending to take. . . . It was so sad after all the poor boy had suffered, he should have been alone at last. . . .

“Francis was with me at the Pavilion a day or two previous to my leaving [for Europe] & saw me off, on board the steamer. I have the mournful satisfaction of having seen him what I could before I left. I hope he is now in a sphere better adapted for his happiness & progress.”

Ironically, in the days after the raid on Harpers Ferry, Meriam had been reported dead, possibly as a ruse by his friends to provide cover while Francis made his way to Canada. On that occasion, condolences poured into the home of Francis’s family in Boston. Theodore Parker, who had helped finance Brown’s activities, wrote to Eliza Eddy, “To the emancipation of American bondmen you have contributed your first-born son: not a drop of his blood is wasted. He himself is immortal, and has passed to that higher world we shall all enter on before long.” But Meriam’s actual death passed almost unnoticed, although Phillips did relay the news to Brown’s widow. Not even his burial place is known to us, although it seems likely that given the circumstances, his body would have been taken to the morgue and, having gone unclaimed for the prescribed time, ended up in one of New York City’s potters’ fields, perhaps on Ward’s Island. Thus, the wealthiest of Brown’s recruits–he contributed $600 in gold to the cause–in all probability lies in a pauper’s grave.

[image error]October 13, 2021

Shopping with Francis J. Meriam

On October 13, 1859, 21-year-old Francis J. Meriam leftBarnum’s City Hotel in Baltimore to goon a shopping trip.

The grandson of Francis Jackson, a prominent Boston abolitionist, Meriam had read of John Brown’s exploits in Kansas and may have even gone out there to join him, although he never caught up with Brown. In October 1859, however, Lewis Hayden, a black abolitionist who had been recruiting men for Brown’s cause, heard that Brown was badly in need of money. While walking in the streets of Boston, Hayden ran into Meriam, whom he knew to be well supplied with cash, having inherited a respectable sum from his father. Thrilled to be of help, Meriam agreed to give $600 to the cause–provided that he was allowed to join his hero. This was somewhat problematic, for Meriam (for whom I have a considerable soft spot) was not an ideal conspirator. Having lost an eye in a youthful accident, he was also in frail health, both mental and physical, and at the time had conspicuous blotches on his face, which the “wanted” notices that were put out for him later claimed were due to syphilis. Understandably, Brown’s Boston supporters were less than enthusiastic about this new recruit (Franklin Sanborn judged that he was “as fit to be in the enterprise as the Devil to keep a powder house”). Nonetheless, $600 was nothing to sneeze at, and Meriam was sent on his way down South.

At Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, where he boarded for a short time with John Kagi, another of Brown’s men, Meriam took the notion to have his will drawn up (he left his money to the abolitionist cause). The young man then proceeded to Baltimore, where he checked into the fashionable Barnum’s (which in 1861, ironically, would later be the headquarters of a plot to assassinate the soon-to-be inaugurated Abraham Lincoln; it was also a favored lodging of one John Wilkes Booth).

At the hotel on the evening of October 12, Meriam wrote a letter to his doctor, an osteopath by the name of Dr. David Thayer: “I telegraphed to you from Harrisburg yesterday, requesting you to send me at once by Adams Express four times the quantity of medicine you first gave me. . . . I did this so as to have enough and a package or two to loose [sic] as I may be where I cannot receive more medicine.” After detailing his symptoms for a couple of paragraphs, Meriam added, “I know you will want to write to me to warn me of the danger but I shall be of[f] before you can reply to this. I will try to save myself from exposure as much as possible that may or may not be very much.”

The next day, Meriam arose and went to the establishment of Schaeffer & Loney on Hanover Street, where he requested a whopping forty to fifty thousand military percussion caps. Edward Schaeffer later testified before a congressional committee, “We had on hand only about twenty and one fourth thousand at the time. He objected a little to the price we asked, but said he would see whether he could make up the quantity. I told him there were other houses in the city who kept them. As he went out of the store, he passed by where samples of spades and shovels were hanging up, and wished to know the price of spades and shovels. I suspected that he was furnishing supplies for some filibuster expedition, though I knew that New Orleans and New York were generally the places where they got up those expeditions. Still, the appearance of the young man was unfavorable, and I refused to give him the price of the spades and shovels. I walked with him towards the door, and told him there were other houses in the city where he could probably procure a supply of them, and he went out.”

Despite this unfriendly reception, Meriam returned onOctober 14 and bought the percussion caps. By this time, as Schaefferrecounted, his nerves were clearly getting the better of him: “Meriam’s manner appeared to berather excited. He pulled out his money, which was in $20 gold pieces; andthere were $14 or $15 of change coming to him, and in his hurry he went offwithout getting it. The young man called him back and gave him the change.”

On October 15, Meriam arrived at Harpers Ferry, where,bearing a large trunk, he stopped at the Wager House hotel, dined, and, as the New York Herald later reported, wrote anumber of letters, “taking peculiar pains to prevent any one from seeingwhat he had written.” Presently, one of John Brown’s sons arrived to takeMeriam and his bounty to the Kennedy Farm in Maryland. It was the only timeMeriam would see Harpers Ferry: when the raid commenced the next evening, hewas among those appointed to remain on guard duty in Maryland. It was anassignment that would save his life: with considerable help from John Brown’sson Owen, he made it through the hills alive and escaped to Canada.

September 18, 2021

Coming in December!

My latest novel, John Brown’s Women, will be published on December 7, 2021! It will be available in both paperback and electronic editions; for now, you can pre-order the electronic version on Amazon or at Barnes and Noble.

From the back cover:

As the United States wrestleswith its besetting sin—slavery—abolitionist John Brown is growingtired of talk. He takes actions that will propel the nation toward civil warand thrust three courageous women into history.

Wealthy Brown, married to JohnBrown’s oldest son, eagerly falls in with her husband’s plan to settle inKansas. Amid clashes between pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers, Wealthy’sadventure turns into madness, mayhem, and murder.

Fifteen-year-old Annie Brown isthrilled when her father summons her to the farm he has rented in preparationfor his raid. There, she guards her father’s secrets while risking her heart.

Mary Brown never expected to bethe wife of John Brown, much less the wife of a martyr. When her husband’sdaring plan fails, Mary must travel into hostile territory, where she finds theeyes of the nation riveted upon John—and upon her.

Spanning three decades, John Brown’s Women is a tale of love andsacrifice, and of the ongoing struggle for America to achieve its promise ofliberty and justice for all.

March 28, 2021

Ladies with Hatchets

Mound City circa 1873-1874. Kansas Historical Society

Mound City circa 1873-1874. Kansas Historical SocietyIn 1861, the citizens of Mound City, Kansas, had a nuisance on their hands: a saloon that served its customers indiscriminately.

According to William Mitchell’s Linn County, Kansas: A History, two inebriated soldiers had frozen to death while trying to make their way back to their posts, and another drunken soldier had shot a nurse, necessitating the amputation of part of her arm. Mrs. Ira Height, a merchant’s wife, decided that something had to be done.

On December 10, 1861, five young women, armed with axes and hatchets, arrived at the saloon. They were Amelia and Drusilla Botkin and Emma, Sarah, and Mary Wattles. Augustus Wattles, the father of the three Wattles sisters, had been a friend of abolitionist John Brown during the latter’s days in Kansas. The imprisoned Brown had remembered the Wattles family fondly to his wife in a letter dated November 16, 1859, and had mentioned “dear gentle Sarah Wattles” in particular.

Having met Mrs. Height in the town, gentle Sarah and the rest entered the bar, where the morning’s first customer was already being served, and proceeded to business. As described by Mitchell, “They first attacked the bottled goods behind the bar. Armed with a long-necked bottle, one of the girls standing on the bar would make a swipe at a whole row of bottles, smashing them and scattering their contents over the bar and floor. They broke jugs and other containers, chopped holes in kegs and poured whisky on the floor.” By the time the women had finished their work in both the front room and back room, they were nearly ankle-deep in whisky, a problem Drusilla Botkin solved by chopping a hole in the floor. When one of the saloon owners protested to Sarah, she responded, “I never did you as great a kindness as that which I am doing now.”

As this was occurring a crowd, largely sympathetic to the women, had collected to observe the goings-on, and a whisky seller from Leavenworth joined the spectators. Sarah Wattles took advantage of his distraction to walk up to his wagon, which contained barrels and kegs equipped with faucets, and to open all of the faucets so that his whisky flowed out upon the ground. When the furious seller threatened to strike Sarah, Amelia Botkin brandished her hatchet at him, and some of the citizens went so far as to put a rope around his neck. He was finally permitted to leave unharmed after being made to promise never to return to Linn County.

Their work accomplished, the young ladies, “almost drunk from the whisky fumes,” returned home. Mitchell wrote, “Their method may have been a little bit irregular. Undoubtedly it was heroic, but it was effective and it met the hearty approval of the good people of Linn County.” Decades later, Carrie Nation would visit her own “hatchetations” upon saloons.

According to her obituary, Sarah Wattles had wanted to attend Harvard but found its doors barred to women. She married a physician, Dr. Lundy Hiatt, and began her own medical studies, after which the couple practiced medicine together in Kansas and in Texas until his death in 1892. While in Texas, Sarah petitioned the Constitutional Convention of 1875 to extend the vote to women. Sarah later returned to Mound City, where she continued to work as a physician, and died at her niece’s house in Kansas City in 1910.

Newspaper ad for Sarah’s medical practice

Newspaper ad for Sarah’s medical practice

February 24, 2021

Two Letters from John Brown, Jr.

A couple of years ago, I acquired these two letters written by John Brown, Jr., to Franklin Sanborn in 1885 and 1895. John, Jr., was the oldest son of the abolitionist John Brown, and Sanborn had been one of the senior Brown’s backers known as “The Secret Committee of Six.” Sanborn later published a biography of John Brown, along with a number of articles, and the 1885 letter references some publisher’s proofs he sent to John Jr. for his input.

John Brown, Jr., ca. 1888 (Kansas Memory site)

John Brown, Jr., ca. 1888 (Kansas Memory site)Born in Hudson, Ohio, in 1821, John Jr. worked variously as a schoolteacher, as a phrenological lecturer, as his father’s assistant in the wool business, and as a farmer before he went to the territory of Kansas in 1855. An outspoken abolitionist who was elected to the territory’s Free-State legislature (not recognized by the federal government), he did not participate in his father’s 1856 “Pottawatomie massacre,” where five pro-slavery settlers were murdered, but he was arrested nonetheless. Already in the throes of a mental breakdown at the time of his arrest, he was maltreated and for a while lost touch with reality altogether. He spent much of the summer and early fall of 1856 in prison, where he regained his sanity. After being released on bail, he returned to Ohio. Although he helped store and ship weapons, raise funds, and recruit men for his father’s famous Harpers Ferry raid, he did not go to Virginia himself and thus was spared his father’s fate.

After the Civil War broke out, John Jr. helped recruit troops and served as a captain with the Company K of the Kansas Seventh. He developed crippling rheumatism, however, and left the service in 1862. He, his wife, Wealthy, and their son, Johnny, moved to Put-in-Bay, Ohio, from where these two letters were written, and grew grapes. A daughter, Edith, was born after the war. John Jr. spent the rest of his life in Put-in-Bay. By 1893, he was suffering from heart trouble, which was still plaguing him when he wrote to Sanborn in January 1895. On May 2, 1895, just a few months after the second letter was written, John Jr. suffered a fatal heart attack.

Letter 1

Put-in Bay, O, Feby 16, 1885

My Dear Friend

The last mail (Saturday evening) brought me the first twelve pages of the “proof.” The wrapper appeared to fit so loosely that I fear some portion of what you did send is lost. I have read it carefully and added a “note” as you will see. Yesterday I took it over to Gibraltar and read it to Owen [John’s younger brother, who served as a caretaker at the estate of the wealthy financier Jay Cooke]. We are all much pleased with the beginning, and that you have included in this the little autobiography of our old dear Grandfather [Owen Brown, Sr., the elder John Brown’s father] as written by himself. I notice in the proof, absence of any mention in that memoir of the birth of my Uncle, Oliver O. Brown (Lemuel’s father). Was this overlooked in copying, or did it fail to appear in Grandfather’s manuscript? Don’t know if this omission can now be supplied. I wrote to Aunt Marion Hand in regard to this, last evening.

A few days since I wrote her sending the first, second and fourth of the six questions you sent to me and by last mail I received in reply the following, dated at Wooster, Ohio, the 12th.

“Your letter of the 9th received, and I hasten to reply. As it regards my Father’s letters to your Father, and replies, I think they are scattered among the different families. I do not remember to have seen one of your Grandfather’s letters to your Father. Sometime after Father’s decease when Mother was about to leave the old home, and had found places for articles of furniture that she did not wish to take, Jeremiah [a half-brother of the senior John Brown] did take the desk which must have had most of the papers that Father had retained. The first time I was at his house after this, he said to me that Father’s death was there, and we looked it over together, I taking some of your Father’s and two or three of Brother Salmon’s letters, some of which you have. Where there have been so many changes as in our family within the last thirty years, it would be difficult to find correspondence unless it was special: still there must be in that old desk (if fire has not eaten it up) some of what you seek. I will write to Lucy [here John Jr. adds a footnote to Sanborn explaining, “i.e., Jeremiah’s daughter at Hudson, O”] to day asking her to send you what she can find. I do not know whether I sent you or Ruth [John Jr.’s sister] all I had, but will ascertain, as it will be in Wellington if I have any left. As to your Father’s going as Surveyor to Virginia, Rev. John Keep of Oberlin was one of the oldest Trustees of Oberlin at the time, and his son, Rev. Theodore Keep now living in Oberlin, I think could probably tell more than any other person now living, of what there was in connection with that gift of land to the College. [John Brown had been engaged by Oberlin College to survey some land it held in what is now West Virginia.]

“Brother Salmon was editor of the New Orleans Bee, a large paper, one half in French, one half in English. I remember it well, but do not think a copy could be found short of New Orleans. It would date back to 1829, 30, 31, 32 and 33: 1833 the year of his death. I do not remember the street or locality in which it was published. Perhaps you may have friends going to the Exposition that would take the trouble to enquire and perhaps find the paper still published.”

I send you the only letters I have of Uncle Salmon. When read, please return them to me.

By Wednesday’s mail I will send you what I have written in reply to your questions.

Yours–John Brown, Jr.

Letter 2

Put-in-Bay Ohio Jan. 28, 1895

Monday

Dear Friend:

Yours of the 24th inst. did not arrive until today owing to severe storm rendering it impossible to cross with small boat from Catawba Island until this morning. Our last mail before to day, reached here on Thursday the 24th.

The Steamer American Eagle laid up here on the 5th of this month. Since then we have had no steamboat crossing and in consequence the mails have been extremely irregular, and crossing by passengers with small boat iron clad with runners attached for service either in open water or on ice strong enough has been not only difficult but dangerous. Have reckoned much on you visiting us, and greatly regret that I cannot send you a more favorable report of our situation as to travel. Should the weather remain cold for a few days so that the ice on the channels could become thick and strong enough to resist high wind and waves I should feel like urging you to secure a new experience, that of crossing one of the channels of Lake Erie with horse and sleigh. As it is I cannot ask you to take the extra risks and incur extra expense, but hope for a visit at a more favorable time. The Eagle is not likely to be brought out before the opening of navigation in the spring.

My family are enjoying pretty good health this winter except myself and even in my case the very painful attacks of neuralgia of the heart are not quite so frequent, but I am greatly troubled with shortness of breath, a rather new phase of the old difficulty perhaps.

Should you meet Mrs. Stearns, please say to her that her very precious letter was duly received and I hope to send her a word in reply soon.

With sincere regards to you all and hoping to yet receive a visit from yourself and Mrs. Sanborn I am ever

Faithfully your friend,

John Brown, Jr.

To: F. B. Sanborn Esqr.

G.P.O.

C B & 2 R.Rd.

Chicago,

Ills.

September 28, 2020

Another Boardinghouse, Another Conspiracy

In 1865, a widowed Washington, D.C., boardinghouse keeper named Mary found herself at the center of a conspiracy: to kidnap President Lincoln. When the conspiracy plot turned into an assassination plot, Mary Surratt paid with her life, being hanged on July 7, 1865.

Nearly six years earlier, however, another widowed boardinghouse keeper named Mary was embroiled in a conspiracy that would rock the nation. Her name was Mary Ritner, and the conspirators were John Brown and his men.

Described by a former boarder, Franklin Keagy, as “one of the most intellectual and worthy women of her age,” Mary Ritner shared Brown’s views on slavery, if not his methods. Mary Ritner’s father-in-law, Joseph Ritner, who had been the governor of Pennsylvania from 1835 to 1839, had spoken out against slavery, and her husband, Abraham Ritner, a railroad conductor, was said to have been a conductor on the Underground Railroad as well. Abraham had purchased a house on King Street in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, in 1849, and died just two years later, leaving Mary Ritner with a young family to support. She enlarged the house and, like many a widow before and after her, opened it to paying guests for whom she provided food and lodging.

Just about 60 miles from Harpers Ferry, Chambersburg’s accessibility by rail made it an ideal location for John Brown, who throughout the summer and fall of 1859 used Chambersburg to receive arms and supporters, which he then transported to his base at the Kennedy Farm near Sharpsburg, Maryland. Much of the groundwork was done by John Kagi, who lodged on Mrs. Ritner’s first floor under the name of John Henri. Trained as a lawyer, Kagi had worked as a journalist and had first encountered Brown in Kansas.

Room Occupied by John Kagi

Room Occupied by John KagiWhile Kagi was a long-term lodger, staying in the Ritner house from the summer of 1859 until just before the Harpers Ferry raid in October 1859, John Brown (using the name of “Isaac Smith”), his sons, and his other men were frequent short-term guests. Brown and the others made regular trips by wagon between the Kennedy Farm and Chambersburg; on the trips south, the wagon would be laden with weapons, supplies, and recruits to the cause. It was during one of his visits to Chambersburg that Brown tried, in vain, to enlist an old friend, Frederick Douglass, in the plot.

The Room Where John Brown Slept

The Room Where John Brown SleptBy all accounts, Brown and his men (who claimed to be prospecting for ore) were model lodgers. Abstaining from both alcohol and tobacco, Kagi read aloud to his busy landlady and taught songs and penmanship to her children. When a neighbor’s dog came to ravage Mrs. Ritner’s garden, Kagi summarily shot the unfortunate canine (it didn’t help that the neighbor was a notorious “slave-catcher,” who would hunt down fleeing enslaved people and collect the reward). The Ritner children were particularly fond of Brown, who when leaving town would allow them to ride in his wagon a mile or so before dropping them off and continuing on his way.

The Ritner Parlor (Portrait of Joseph Ritner)

The Ritner Parlor (Portrait of Joseph Ritner)Whether Mrs. Ritner had her suspicions about her boarders is unknown, although a rumor that the group was engaged in counterfeiting reached the ears of one of the Ritner girls and a friend, who peeked through a keyhole only to find the men examining a map. It’s hard to believe that the landlady didn’t wonder about her lodgers, especially in the last few weeks of their stay, when Francis J. Meriam, a blue-blooded, physically frail, and emotionally unstable Bostonian who hardly fit the description of a mineral prospector, began lodging with Kagi, or when John Brown suddenly turned up in his wagon seeking lodgings for a female boarder–Virginia Kennedy Cook, whose husband, John Cook, had ensconced himself in Harpers Ferry to gather intelligence for Brown.

In any case, when John Brown and his men at last struck on October 16, 1859, the news of the raid, and its disastrous end, traveled fast to Chambersburg. Soon, those raiders who had managed to escape began making their way to the place besides the Kennedy Farm they knew best–Mrs. Ritner’s. The Chambersburg Valley Spirit reported that Albert Hazlett actually made it into the boardinghouse, where he conversed with Virginia Cook before fleeing, having first discarded a pistol in the yard. (He was later captured, extradited to Virginia, and hanged.) Presently, another party of fugitives, consisting of John Cook, Owen Brown, Francis Meriam, Charles Tidd, and Barclay Coppoc, turned up at Mrs. Ritner’s. As Owen Brown later wrote:

As we drew nearer and nearer Chambersburg, I told the boys, as I had told them before, that it was not fair to expose Mrs. Ritner. She had probably disavowed any knowledge of us, and it would be very easy to get her into trouble, without benefiting ourselves; but they would go. In the outskirts of Chambersburg, finally, we stopped by a house on the corner of the street which led to Mrs. Ritner’s. Merriam, who had over-exerted himself, dropped down in the middle of this street, and lay with his luggage for a pillow. It was just before the break of day. As Tidd and Coppoc left us, I charged them, with all the earnestness I had, to come right back if they got no answer, and especially to make no alarm. They knocked at the door, but received no reply. Then Tidd went down into the garden and got a bean-pole and thumped on the second-story window. Mrs. Ritner put her arm out of the window and motioned him away. At which he said, “Mrs. Ritner, don’t you know me? I am Tidd.”

“Leave, leave!” came back in a frightened whisper.

“But we are hungry,” insisted Tidd.

“I couldn’t help you if you were starving,” she whispered back again. “Leave; the house is guarded by armed men!”

Tidd dropped his bean-pole, and the two came back to where we were lying in the street.

(Cook later left the group in search of provisions, and met the same fate as Hazlett. The other members of the group managed to avoid capture.)

Mrs. Ritner’s Bedroom Windows

Mrs. Ritner’s Bedroom WindowsMrs. Ritner’s prudence paid off. Whatever she knew or might have guessed, she did not suffer any consequences. Instead, she continued to run the boardinghouse. At the time of the 1860 census, she had three boarders living with her. That same year, she hosted a penmanship class. (Kagi, killed at Harpers Ferry, would no doubt have approved.)

The landlady’s luck held out during the Civil War. In July 1864, the Rebels burned much of Chambersburg after its citizens failed to come up with $100,000 in gold or $500,000 in cash. Yet the Ritner house, just outside of the commercial area, was untouched by the flames. Instead, Mary Ritner’s daughter recalled, Mrs. Ritner offered shelter to a neighbor who had not been so fortunate.

By 1865, however, Mrs. Ritner was ready for a change. She sold her house in August and moved to New England, where she spent the rest of her life, dying on May 2, 1894 in Weston, Massachusetts. Years later, one of her daughters recalled, “I remember how loyal Mother was to [John Brown]. She did not like to have people call him a fanatic.”

Selected sources:

Franklin Keagy, “Biographical Sketch of John Henry Keagy.”

Ralph Keeler, “Owen Brown’s Escape from Harpers Ferry,” Atlantic Monthly (March 1874).

Virginia Ott Stake, John Brown in Chambersburg.

John W. Wayland, John Kagi and John Brown.

September 23, 2020

A Stop by the (First) Washington Monument

A few days ago, my family and I stopped by Maryland’s own Washington Monument–the first such structure erected to honor George Washington.

In 1859, John Brown’s son Owen, fleeing with others after the raid at Harpers Ferry, stopped by the monument as well. In an interview by Ralph Keeler published in the March 1874 of the Atlantic, he recalled:

“When at last we reached the woods, we found them too sparse for our purpose, and went on and up the mountain, still finding no safe camping-ground. On the summit we came upon a sort of monument, or perhaps an observatory, in the shape of an unfinished tower. A white rag was flying from a pole at the top of it. Satisfying myself that no one was about, I went up the winding stairs to take a view of the surrounding country. The others were too much fatigued to go with me. I could see what I took to be the outskirts of Boonesboro’, and enough of the valley we had crossed to give me a vivid idea of the danger we had escaped. Horsemen were scampering hither and thither on the highways, and the whole country, it seemed, was under arms. Descending hastily, I had little difficulty in impressing upon the boys how necessary it was that we should be in concealment. And still we followed along the ridge of that mountain-top for as much as three miles in broad daylight without finding a safe place. We at one time passed not far from an inhabited house, – fortunately unobserved. Finally, as we were about to sink under fatigue, we came to a large fallen tree, and made our bed in the forks of that. Tired as I was, I spent an hour cutting laurel bushes and sticking them into the ground at distances from one another. Laurel you know, will not wilt; and so with care the shrubs were made to conceal us, and look as if they grew there naturally. We were soon all fast asleep, and got through the day safely.”

Ultimately, one of Owen’s companions, John Cook, left the group in search of provisions and was captured, sent to Virginia, and hanged. Owen, however, made it through safely. A bachelor, he eventually moved to California and died in Pasadena in 1889 (photo from Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library).

July 7, 2020

Why Isabelle d’Angoulême is hard to love: Guest Post by Sharon Bennett Connolly

I’m delighted to welcome Sharon Bennett Connolly back to my blog! I’ve known Sharon since her blogging days, and was delighted when she began to publish her biographies of historical women, including her brand-new one, Ladies of Magna Carta. Today’s woman, Isabelle of Angoulême, is one who’s long intrigued me. Over to Sharon!

At first sight, it is easy to have sympathy for Isabelle of

Angoulême. When I started researching her for Ladies of Magna Carta: Women

of Influence in Thirteenth Century England, I was expecting to be able to

go some way to redeeming her reputation. She was married at a very young age –

she was no more than 12 and may have been as young as 10 – to ‘Bad’ King John,

the man who would later be accused of murdering his own nephew and left a woman to starve in his dungeons.

Isabelle

d’Angoulême was the only child of Audemar, Count of Angoulême and Alice de

Courtenay. Her mother was the daughter Peter de Courtenay, lord of Montargis

and Chateaurenard, and a cousin of king Philip II Augustus of France. Through

her Courtenay family connections, Isabelle was related to the royal houses of

Jerusalem, Hungary, Aragon and Castile. When John set his sights on her, Isabelle

was betrothed to Hugh IX de Lusignan: the chronicler Roger of Howden maintained

that Isabelle had not yet reached the age of consent, which was why she was

still only betrothed to Hugh, rather than married to him. The marriage between

Isabelle and Hugh was intended to put to bed, literally, a long-running, bitter

rivalry between the Lusignans and the counts of Angoulême. It would also unite

neighbouring regions in Aquitaine, posing a threat to Angevin power in the

region. This could have effectively cut Aquitaine in two, jeopardising the

stability of the borders of Poitou and Gascony. John could not help but see the

threat posed by the impending marriage and sought to put a stop to it. Count

Audemar, it seems, was quite receptive to the suggestion that he abandon the

Lusignan match if it meant that his daughter would become a queen.

In

the early years of their marriage, John appears to have treated Isabelle more

like a child than a wife, which she still was, and she was financially

dependent on him. When she was not at court with the king, Isabelle spent time

at Marlborough Castle or in the household of John’s first wife, Isabella of

Gloucester, at Winchester. Isabella’s allowance was raised from £50 to £80 a

year, to pay for the extra expenses incurred by housing the queen.

It appears that Isabelle was an

unpopular queen, guilty by her association with the excesses and abuses of

John’s regime. It was in this light that John’s marriage to

Isabelle was seen as the start of England’s woes, with some of the blame

falling unfairly on the young queen. Contemporary sources reported that John

spent his mornings in bed with the queen, when he should have been attending to

the business of the country, casting Isabelle as some kind of temptress,

irresistible to the king. The fact that Isabelle did not give birth to her

first child until 1207, when she was in her late teens, puts the lie to these

sources, suggesting that she and John

did not consummate the marriage in the first few years. After 16 years together, the

couple had 5 children; Henry III, Richard of Cornwall, Isabella, Joan and the

youngest, Eleanor, who was born in 1215 or 1216.

While her movements were

restricted and closely controlled during her marriage to John, the situation

did not improve for Isabelle following John’s death in 1216. Their 9-year-old

son Henry was now king, but Isabelle was excluded from

playing a role in the regency government; her unpopularity in England and lack

of political experience were major factors. Moreover, she had had limited

contact with her children: they lived in separate households and Isabelle was

not responsible for their supervision or education, which added to her

isolation. Almost

as soon as Henrys crowned, Isabelle started making arrangements to go home, to

Angoulême, of which she was countess in her own right. In 1217 she left England.

Once in her own domains,

Isabelle was to arrange the wedding of her daughter, Joan. Joan had been betrothed, at the age of 4, to Hugh X

de Lusignan, Count of La Marche and the son of Hugh IX, the man who had been

betrothed to Isabelle before John married her. In 1220 Isabelle shocked England, and probably the

whole continent, when she scandalously married her daughter’s betrothed herself.

Poor 9-year-old Joan’s erstwhile fiancé was now her

stepfather! Worse was to come, however, when the little princess was not

returned to her homeland, as might have been expected, but held hostage, by Isabelle

and Hugh, to ensure Hugh’s continued control of her dower lands, and as a

guarantee to the transfer of her mother’s dower, which the English government

was withholding against the return of Joan.

Stalemate.

Isabelle wrote to

her son, Henry III, to explain and justify why she had supplanted her own

daughter as Hugh’s bride, claiming ‘…lord Hugh of

Lusignan remained alone and without heir in the region of Poitou, and his

friends did not permit our daughter to be married to him, because she is so

young; but they counselled him to take a wife from whom he might quickly have

heirs, and it was suggested that he take a wife in France. If he had done so,

all your land in Poitou and Gascony and ours would have been lost. But we,

seeing the great danger that might emerge from such a marriage – and your

counsellors would give us no counsel in this – took said H[ugh], count of La

Marche, as our lord; and God knows that we did this more for your advantage

than ours…’

Ironically, Isabelle

had now achieved that which King John had hoped to avoid; the union of La

Marche and Angoulême, splitting Angevin Aquitaine down the Little Joan was

finally returned to England towards the end of 1220, but the arguments over

Isabelle’s English lands continued throughout the 1220s and beyond. Isabelle

would not retire in peace and in 1224 she and Hugh betrayed Henry by allying

themselves with the King of France. In exchange for a substantial pension, they

supported a French invasion of Poitou (the lands in France belonging to the

King of England, her son). They were reconciled with Henry in

1226 and Isabelle met her first-born son for the first time in more than twelve

years in 1230, when Henry mounted a futile expedition to Brittany and Poitou.

Isabelle and Hugh, however, continued to play the kings of France and England

against each other, always looking for the advantage. In 1242, for example,

when Henry III invaded Poitou, Hugh X initially gave support to his English

stepson, only to change sides once more, precipitating the collapse of Henry’s

campaign. Isabelle herself was implicated in a plot

to poison King Louis IX of France and his brother, only to be foiled at

the last minute; the poisoners claimed to have been sent by Isabelle. There is

no evidence of Isabelle denying the accusation, but she never admitted her

guilt, either.

Isabelle’s second marriage proved even

more unstable than her first, shaken by Hugh’s frequent infidelities and

threats of divorce. Isabelle enjoyed greater personal authority within her

second marriage; where she had issued no charters whilst married to King John,

as Hugh de Lusignan’s wife, the couple issued numerous joint charters. Her difficult

relationship with France added to Isabelle’s marital problems. In one instance,

Isabelle was offended by the queen of France when she was not offered a chair

to sit, in the queen’s presence, regardless of the fact she herself was a

crowned and anointed queen. Following this insult, in 1241, Isabelle castigated

Hugh de Lusignan for supporting a French candidate to the county of Poitou,

ahead of her son, Henry III. In retaliation, Isabelle stripped Lusignan Castle

of its furnishings and refused to allow her husband into her castle at

Angoulême for three days.

Despite the rocky relationship,

Isabelle and Hugh had nine children together, including Aymer de Lusignan and

William de Valence. Many of his Lusignan half-siblings would later cause

problems for Henry III, having come to England to seek patronage and

advancement from their royal half-brother.

As

contemporaries described her as ‘more Jezebel than Isabel’, accused her of

‘sorcery and witchcraft’, Isabelle of Angouleme’s reputation as a heartless

mother and habitual schemer seems set to remain. Married to King John whilst

still a child, she was castigated as the cause for the loss of the majority of John’s

continental possessions and the subsequent strife and civil war; one could

easily sympathise with her lack of love for England. That Isabelle abandoned

the children of her first husband within months of his death, and her apparent

willingness to betray her son for her own ends goes some way to destroy the

compassion one may have felt for her.

That being said, Isabelle d’Angoulême is a

fascinating character!

Author bio:

Sharon Bennett Connolly has been fascinated by history her whole

life. She has studied history academically and just for fun – and even worked

as a tour guide at historical sites. For Christmas 2014, her husband gave her a

blog as a gift – www.historytheinterestingbits.com – and Sharon started

researching and writing about the stories that have always fascinated,

concentrating on medieval women. Her latest book, Ladies of Magna Carta:

Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England, released in May 2020, is

her third non-fiction book. She is also the author of Heroines of the

Medieval World and Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest.

Sharon regularly gives talks on women’s history; she is a feature writer for All

About History magazine and her TV work includes Australian Television’s ‘Who

Do You Think You Are?‘

Links:

Blog:

https://historytheinterestingbits.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Thehistorybits/

Twitter:

@Thehistorybits

Pen & Sword

Books: https://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/Ladies-of-Magna-Carta-Hardback/p/17766

Amazon: mybook.to/LadiesofMagnaCarta