Susan Higginbotham's Blog: History Refreshed by Susan HIgginbotham, page 8

March 31, 2015

A Petition to Rebury Anne Boleyn

With Richard III in his final resting place, things have become rather quiet lately, leading me to turn my thoughts to another controversial royal: Anne Boleyn.

It's Time.

Anne, of course, was briefly exhumed in the nineteenth century during renovations in the Tower’s Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula, but the Victorians, missing a grand opportunity, quietly reburied her. Isn’t it time we considered digging her up again and giving her a proper burial elsewhere?

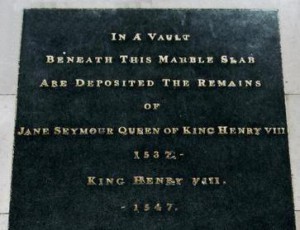

Think, for instance, how dull it is going to be now that no one is fighting about where to bury Richard III. With an Anne Boleyn reburial, we have several candidates for a reburial site, all no doubt with their partisans to start Facebook groups, organize petitions, bring actions for judicial review, harass all those who don’t agree, and in general act like four-year-olds on steroids. St. Peter’s at Hever, by her father? Westminster Abbey, by her daughter? Windsor, where she can sneer in death at Henry VIII and his vapid Jane Seymour?

Room for one more?

And there’s the matter of religion, always guaranteed to bring out the best in people. Anne was receptive to certain aspects of Protestantism but died a Catholic. Imagine the fuss over the shape her church service will take!

There’s nothing like a good reburial to stir up an argument over a person’s character, and Anne already has her advocates and her detractors who can most mildly be described as passionate. Just think of all the fun once a reburial heats up this debate, and more partisans, having read a novel or two about Anne and therefore learned all there is to know about her, join in!

Of course, there’s that sixth finger to consider. The Victorians found no sixth finger on the body they identified as Anne’s. Without a sixth finger, will there be a debate as to whether we have the right body? Can a conspiracy theory develop as to the whereabouts of that supposed finger? You bet! I’m simply rubbing my hands in glee.

Inevitably, exhuming Anne is going to stir up the strange story that Anne was Henry VIII’s own daughter. Since every bizarre rumor is clearly rooted in truth, this would be the perfect time to obtain some DNA to determine whether this could be true. (This might entail disturbing Henry VIII as well, but after being so mean to Anne, doesn’t he deserve it?)

Finally, there is the delicious prospect of a reconstructed head of Anne Boleyn to contemplate. If it can be made to look as nearly like Natalie Dormer as possible, all the better.

Can the reconstruction live up to Natalie? We'll see!

Now other people have mentioned the idea of reburying Anne (not to mention a posthumous pardon–what fun that could lead to), so I will not claim complete credit for this idea, but will modestly share the stage with others in the event this comes to pass, as it surely will with all of the history-loving world bored out of their skulls with no one to rebury. Just be sure to invite me to the reburial service, and I’ll be there in the VIP section, wearing my best white dress.

To sign my new petition demanding Anne’s reburial, click here.

March 20, 2015

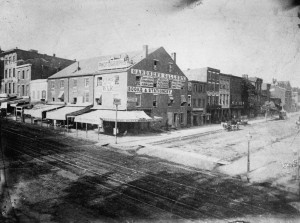

The Carte de Visite and the Lincoln Assassination

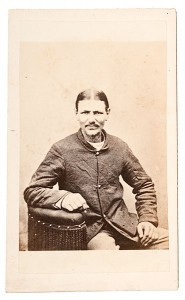

Lately, I’ve developed a weakness for cartes de visite—the small photographs that were prized during the last half of the nineteenth century—and have amassed a tiny collection of them, including one of my favorites here of an unidentified lady.

As noted by the American Museum of Photography, cartes de visite (CDVs, as they are commonly abbreviated by collectors) were albumen prints mounted on cards usually measuring 2-1/2″ x 4″. Patented in 1854 by Parisian photographer Andre Adolphe Disderi, CDVs did not become popular in the United States until the end of the decade. Their small size and sturdiness meant that a sitter could buy multiple copies of his or her photograph for a reasonable price–10 to 25 cents apiece– then easily mail them to distant friends and relatives. The American Civil War added to their popularity, as men had their pictures taken before going off to war and in turn carried the portraits of loved ones with them.

Once one began to accumulate CDVs, of course, one had to put them somewhere. Album makers like D. Appleton & Co. hastened to fill this need, informing newspaper readers, “No drawing room table of the day can be considered furnished without its ‘Photographic Album.’”

Not only ordinary people had their photographs taken. Photographic galleries sold CDVs of celebrities–politicians, actors, writers, singers, royalty, generals, and so forth. John Towles wrote, “Everybody keeps a photographic album, and it is a source of pride and emulation among some people to see how many cartes de visite they can accumulate from their friends and acquaintances. . . . But the public supply of cartes de visite is nothing to the deluge of portraits of public characters which are thrown upon the market, piled up by the bushel in the print stores, offered by the gross at the bookstands, and thrust upon our attention everywhere.” Queen Victoria was both a subject and a collector (“such an amusement–such an interest,” she said). Abraham and Mary Lincoln had their own album, bound in fine leather, although Mary lost her enthusiasm for the pastime after the Lincolns’ son Willie died in 1862.

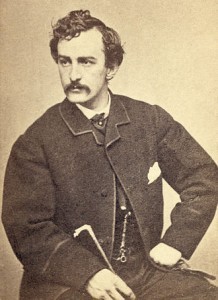

Ubiquitous as CDVs were, it’s not a surprise that they even figured into the Lincoln assassination. The assassin himself, the popular actor John Wilkes Booth, had CDVs of five ladies on his person when he was trapped in a barn and fatally shot in Virginia: Lucy Hale, his secret fiancée, and four actresses, Alice Grey, Effie Germon, Helen Western, and Fannie Brown. (As Lucy was the daughter of a New Hampshire senator, her link to the assassin was kept from the public.) The five CDVs (including Lucy’s, shown below) can be seen at the Ford’s Theatre museum in Washington.

Booth’s celebrity as an actor and his striking looks, of course, meant that his own CDV was much in demand long before he committed the crime of the century. Among the many admiring ladies who bought his picture were Anna Surratt, whose mother, Mary, kept a Washington, D.C., boardinghouse frequented by Booth, and Nora Fitzpatrick, a twenty-year-old boarder. One day in the spring of 1865, Nora, who had had her photograph taken, went with Anna Surratt to pick up the finished product. Seeing CDVs for sale of their exciting new acquaintance, Booth, each lady purchased one.

After the assassination, when suspicion fell upon the occupants of the boardinghouse, Mary Surratt, Anna Surratt, Nora Fitzpatrick, and Mary’s visiting niece were arrested and the boardinghouse searched. Detectives found Nora’s CDV of Booth concealed between two others in her album, while another detective, lifting a popular print entitled “Morning, Noon, and Night” off a mantelpiece, found that someone had punched a hole through the back of the frame and concealed Anna’s CDV of Booth inside. The searchers also found a number of CDVs of Confederate leaders and generals, which cast further doubt as to the loyalties of the inmates of the boardinghouse. As it turned out, the CDVs belonged to Anna, who when testifying for her mother’s defense during the conspiracy trial was questioned about her collection:

Q. [Exhibiting to the witness the picture of “Morning, Noon and Night,” already in evidence.] Do you recognize that picture as ever having belonged to you?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Was it your picture?

A. Yes, sir: it was mine, given to me by that man Weichmann.

Q. Was any other picture ever attached to it?

A. I put one of J. Wilkes Booth behind it.

Q. What was your object in doing that?

A. I went one day with Miss Honora Fitzpatrick to a daguerrean gallery to get her picture (she had had it taken previously), and we saw some of Mr. Booth’s there; and having met him before, and being acquainted with him, we got two of the pictures and took them home. When my brother saw them, he told me to tear them up and throw them in the fire; and that, if I did not, he would take them from me; and I hid them.

Q. Did you own any photographs or lithographs of the leaders of the Rebellion—Davis, Stephens, and others?

A. Yes, sir. Davis, Stephens, Beauregard, Stonewall Jackson, and perhaps a few others.

Q. Where did you get these?

A. My father gave them to me before his death; and I prized them on his account, if on nobody else’s.

Q. Did you own any photographs in the house at that time, of Union generals?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Who were they?

A. General McClellan, General Grant, and General Joe Hooker.

Anna’s eclectic taste in CDVs, sadly for her, did nothing to save her mother from the gallows.

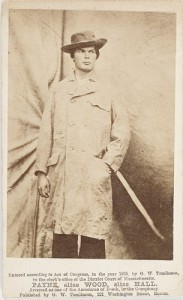

Prior to their trial, six of the eight suspects–George Atzerodt, Lewis Powell (known during the trial by his alias of Lewis Payne), Samuel Arnold, David Herold, Michael O’Laughlin, and Edman Spangler–were photographed by Alexander Gardner while they were being held prisoner. Soon Gardner was doing a brisk business in selling CDVs of the gloomy or sullen-looking men, such as the one of Lewis “Payne” shown below. Fake CDVs also circulated, like that of Mary Surratt, who had not had her picture taken by Gardner and who kept her face concealed by a veil during her trial.

As for Booth, the public’s horror at his crime did nothing to reduce the demand for his CDV, to the disgust of the government, which banned its sales on May 2, 1865, but rescinded the order on May 26, 1865. Meanwhile, Boston Corbett, the sergeant who had fatally shot Booth in Virginia, soon found his own image for sale, although the fanatically religious Corbett, who had taken the extreme measure of castrating himself to avoid going sexually astray, was an unlikely celebrity.

Naturally, some of these cartes de visite play a role in my forthcoming novel, Hanging Mary. Look for it next year!

Sources:

American Museum of Photography

Dorothy Meserve Kunhartdt and Philip B. Kunhardt, Jr., Matthew Brady and His World.

Mark E. Neely, Jr., and Harold Holzer, The Lincoln Family Album.

Benjamin Perley Poore, ed., The Conspiracy Trial for the Murder of the President and the Attempt to Overthrow the Government by the Assassination of Its Principal Officers.

James L. Swanson and Daniel R. Weinberg, Lincoln’s Assassins, Their Trial and Execution.

February 16, 2015

New Website Material for Hanging Mary

I’ve been tinkering a bit with my website. For my forthcoming novel (for which I hope to be able to post cover art soon), I’ve added a list of further reading as well as a PDF article about my research on Nora Fitzpatrick, much of which concerned Nora’s later life and thus didn’t make it into the novel. So take a look, especially if you’re one of those snowed in or about to be snowed in!

February 13, 2015

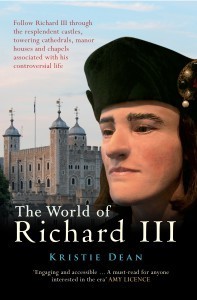

The World of Richard III: Kristie Dean’s Blog Tour

I’m absolutely delighted to welcome Kristie Dean to my blog as part of her tour! Her new book, The World of Richard III, focuses on the places associated with Richard III. If you’re preparing to go to England for the reburial next month, or if you’ll be an armchair traveler this time, do pick up a copy.

And now, over to Kristie with an excerpt from her book!

“The discovery of a new location for the battle between Richard and Henry Tudor made this an exciting section to write. As new information is found, we may have to change our understanding of the battle even more. The visitor centre at Bosworth is one of the best I have seen, and it helps keeps visitors up-to-date on the current research”

Kristie Dean

Bosworth, Leicestershire

Give me my battle-axe in my hand,

Set the crown of England on my head so high!

For by Him that shope [shaped] both sea and land,

King of England this day will I die!

The Ballad of Bosworth Field

In 2005 a grant was awarded for a battlefield survey of Bosworth Field, and after several years of hard work the battlefield site was discovered in 2009. With the discovery of this new site for Bosworth, scholarship was turned on its head. Previously accepted facts are being re-examined in the light of archaeological evidence. It may be years before a completely accurate account of troop deployments may be deduced.

At the beginning of August, Henry Tudor set sail either from Honfleur or Harfleur bound for England. Surrounded by a group of displaced Lancastrians, he came ashore near Milford Haven in Pembrokeshire. According to Fabyan, once Henry made it ashore he dropped down and kissed the soil of England. On 11 August Richard, learning of Tudor’s arrival in England, began ordering men to meet him in Leicester. After organising his troops, Richard rode out of Leicester with ‘great pomp, wearing his diadem on his head’.

As Henry and his men were marching south on Watling Street towards London, Richard was heading to intercept them. He marched from Leicester and made his camp near the battlefield, either near Sutton Cheney or on Ambion Hill, as suggested by Glenn Foard and Anne Curry in Bosworth 1485: Battlefield Rediscovered. Vergil says Richard encouraged his troops the night before the battle and ‘with many woords exhortyd them to the fight to coome’.

As the morning of 22 August dawned, Richard awoke to face his last day. The Croyland Chronicle says that Richard’s chaplains were not ready to celebrate Mass. Tradition has it that Richard may have taken Mass at Sutton Cheney church. It is hard to believe that a man as pious as Richard would have skipped Mass, especially on such an important day.

Henry is believed to have camped near Merevale Abbey. Later records indicate that he paid the surrounding villages for damages to their land. The next morning he moved towards Richard’s army.

The two armies would meet on Fenn Lane between Dadlington, Stoke Golding and Shenton. This location is about three kilometers away from Ambion Hill.

According to Vergil, after Richard assembled his men, his line was of ‘wonderful length so full replenished both with footmen and horsemen that to the beholders afar it gave a terror for the multitude’. Accounts differ as to how many men each army had amassed, but Richard had the larger army.

As the two armies clashed, Richard’s scouts noticed that Henry and a small group of men were moving away from the main army. Richard probably decided that killing Henry would make for a quick end to the battle and charged across the battlefield directly at Henry. Making his way into the thick of the fray, Richard managed to kill William Brandon, Henry’s standard bearer, as he tried desperately to reach Henry.

At this moment, Stanley reached a decision and his troops headed for Richard, pushing him back into the marsh and forcing him to fight on foot. Richard fought valiantly but he was struck down. He fell ‘like a spirited and most courageous prince … in battle on the field and not in flight’. After the discovery of his body, scientists determined that Richard had a number of injuries to his skull. The exact location where Richard was struck down is not known, although Henry issued a proclamation saying that it was at a place known as ‘Sandeford’. Recent archaeological work in a field unearthed a boar badge near what was part of the medieval marsh. This fascinating find may mean that this was the location where Richard met his end.

With Richard’s death, the cause was lost, and many of his men surrendered or fled. Vergil says that after his victory Henry made for the nearest rising ground. Here he gave the nobility and gentlemen ‘immortal thanks’ while the soldiers cried out ‘God save King Henry!’ It was here that Stanley took Richard’s crown, which had been found in the field, and placed it on Henry’s head. Today the accepted location for this event is Crown Hill. Henry then proceeded towards Leicester.

Richard’s body, stripped of clothing, was slung across a horse’s back. Examination of his bones shows that he was subject to many wounds. These would have been exposed for all eyes to see as he was taken back to Leicester. The Croyland Chronicle says that many insults had been offered to the body and it was carried to Leicester with ‘insufficient humanity’. The reign of the last Plantagenet king of England was over, and the reign of the Tudors had begun.

The World of Richard III by Kristie Dean is published by Amberley Publishing, 2015. The book is available to buy at all good bookstores, as well as online at the Amberley website, Amazon and The Book Depository.

February 12, 2015

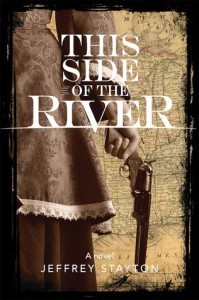

Guest Post by Jeffrey Stayton, Author of This Side of the River

Today I’m happy to be hosting Jeffrey Stayton, who’s written a novel set in the immediate aftermath of the American Civil War called This Side of the River. Over to Jeffrey!

Nostalgia

One of the most difficult aspects of writing historical fiction, especially about the Civil War, is the fact that too often the language of honor and glory from the era works its way into these narratives at the expense of portraying the actual horrors of war. Although This Side of the River is a work of fiction (and speculative history at that), I ruthlessly researched in university, state and county archives for years before even formulating the first drafts. What I found most important to me was not so much the dates, the names, nor even battle descriptions so much as how each writer expressed himself or herself in their respective memoirs, letters-to-home and war-journals and diaries. I soon created a document where all of these interesting words, mispronunciations and unusual turns of phrase were placed for safekeeping. It was important for me to know that if you though a road was passable back then, you more likely than not said it was “practicable.” My favorites were fun expressions, such as the oath, “May rosined lightning strike me dead” if I tell a lie. Those details found their way into the final draft that is now This Side of the River.

What struck me next came much later in drafting this novel. Not long after the Afghan and Iraq Wars were waged, we began seeing men and women return from battle suffering from PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) syndrome. They returned in large numbers because our medical science is advanced enough to allow more dying soldiers to live, yet our civilization has not yet advanced to where we recognize that war is not simply “all Hell” as Gen. William T. Sherman famously put it: war is waste. It is a waste of “blood and treasure” and more often wars beget wars, setting the stage for the next conflict with similar bloody outcomes. So I grew interested in how Civil War soldiers suffering from PTSD dealt (or couldn’t) deal with the trauma. I learned that the term for this syndrome was often called, “nostalgia” or “soldier’s heart,” though many still regarded such things as an expression of simple cowardice. At the same time, my novel, which had been an 1861-1865 narrative, was turning into a post-Civil War story set in the summer of 1865. I felt like the post-apocalyptic South was a better environment for expressing “nostalgia” not only in soldiers, like Cat Harvey, but also the civilians who survived Sherman’s March to the Sea, like the warrior-widows who advance my story.

All of this I obviously found fascinating, though I had to look for other source material than simply Civil War documents. I began reading war-stories from many 20th and 21st Century conflicts to access the horrors of warfare without the veiled language of honor and glory getting in the way, whether this was Tim O’Brien’s Vietnam War story-cycle The Things They Carried or Ishmael Beah’s account of being a child soldier in the Congo in A Long Way Gone. What is clear is that the adults who should have protected their children from such bloodshed nonetheless insist on enlisting these boys, many literally children, into their wars. And then we expect them to somehow metabolize those horrors for the rest of their lives and grow to become good citizens. It is simply sick.

Finally, This Side of the River went through thousands of pages (I’m not exaggerating here) before I found page one of what would become my novel. By then I knew I was telling the story of Cat Harvey, a nineteen-year-old who had committed war crimes with a Confederate black-ops unit known as Shannon’s Scouts. What little we know of them speaks to the dark heart of the matter—pointblank shootings, reenslavement of recently freed slaves—and those were the things documented. I imagined even worse crimes primarily for two reasons. Whenever Gen. Joe Wheeler rode with Col. Shannon and his scouts, he rode under the alias, “Priv. Johnson.” Why did he do this? What were they doing that required this name change? Moreover, I was struck by the fact that Col. Shannon himself declined a Texas newspaperman’s encouragement to write his memoir about the Scouts heroic deeds. Shannon declined, citing that some Confederate sympathizing Northerners would be punished for their involvement. This somehow rang false to me as I read it. In a time when every soldier, especially colonels and generals, wrote of his heroic deeds in the Civil War, why not Alexander Shannon? This is where historical record ends and speculative historical fiction begins I suppose. So I found that I not only needed to explore this heart of darkness in Civil War lore, I needed to tell it in a style that dramatized it: the mosaic narrative. Once I began letting the various Georgia war-widows tell their stories, a shattered, cubistic portrait of Cat Harvey emerged that I felt worked.

I’ll leave it for the readers to decide on that one.

Synopsis:

This Side of the River is a novel set in in Georgia in the summer of 1865, after Confederacy has collapsed. A contingent of war widows who have survived Sherman’s March have armed themselves and rallied around a teenage Texas Ranger named Cat Harvey in order to ride north to Ohio and burn Gen. Sherman’s home to ashes. It is a story about trauma, revenge and redemption. What happens when they light out for Ohio is a terrible, doomed odyssey that forces these young women to ask the darker questions of the human condition.

Bio:

Jeffrey Stayton grew up throughout Texas and lived in Mississippi before landing in Tennessee where he’s lived with his wife in Memphis for the past four years. The southern author releases his first literary noir novel in February 2015, the 150th anniversary year of the Civil War’s end. This Side of the River was inspired by his question of what would have happened if the war-widows of Georgia took up arms in the aftermath of the Civil War?

He earned his Ph.D. in English from the University of Mississippi and specializes in 20th Century American literature.

He writes poetry, has written book reviews for the Missouri Review and has published stories in StorySouth, Lascaux and Burningword Literary Journal. His original story “Pepper” won the Bondurant Award for Fiction, and his story “Chisanbop” appeared in the Best of Carve Magazine.

He is a scholar and teacher of Modernist, Southern and African-American literature, often teaching women’s literature courses as well. His passion for Latin American literature brought Stayton and his wife on a hike across northern Spain on the Camino de Santiago where he brushed up on his Spanish.

When not writing and teaching, he’s in his studio working on oil paintings.

Having at one point performed standup comedy, Stayton embarks on a unique book tour in Winter 2015 gearing up to be as entertaining as the pages within his literary fiction.

January 24, 2015

Guest Post and Giveaway: Adrienne Dillard, Author of Cor Rotto

I’m delighted to welcome Adrienne Dilliard, author of Cor Rotto: A Novel of Catherine Carey, to my blog! Here’s the blurb for Adrienne’s novel, her first:

The dream was always the same … the scaffold before me. I stared on in horror as the sword sliced my aunt’s head from her swan-like neck. The executioner raised her severed head into the air by its long chestnut locks. The last thing I remembered before my world turned black was my own scream.

Fifteen year-old Catherine Carey has been dreaming the same dream for three years, since the bloody execution of her aunt Queen Anne Boleyn. Her only comfort is that she and her family are safe in Calais, away from the intrigues of Henry VIII’s court. But now Catherine has been chosen to serve Henry VIII’s new wife, Queen Anne of Cleves.

Just before she sets off for England, she learns the family secret: the true identity of her father, a man she considers to be a monster and a man she will shortly meet.

Interested in reading Adrienne’s novel? Just comment below before February 1, and I’ll choose a winner! Anyone is welcome to enter regardless of where you live.

And now, over to Adrienne for her guest post!

Cor Rotto: A Farewell Letter

Relieve your sorrow for your far journey with joy of your short return, and think this pilgrimage rather a proof of your friends, than a leaving of your country. The length of time and distance of place, separates not the love of friends, nor deprives not the show of good will. An old saying, when bale is lowest, boot is nearest; when your need shall be most you shall find my friendship greatest. Let others promise, and I will do, in words not more in deeds as much. My power small, my love as great as them whose gifts may tell their friendship’s tale, let will supply all other want, and oft sending take the lieu of often sights. Your messenger shall not return empty, nor yet your desires unaccomplished. Lethe’s flood hath here no course, good memory hath greatest stream. And to conclude, a word that hardly I can say, I am driven by need to write, farewell, it is which in one way I wish, the other way I grieve.

Your loving cousin and ready friend,

Cor Rotto

One of the first things I came across in my research of Catherine Carey was this lovely farewell letter from Catherine’s cousin, the future Queen Elizabeth I. Her heartfelt words made such a lasting impression upon me that eventually, when the time came to name my work in progress, I could think of no better phrase to describe the losses in Catherine’s life than the one that Elizabeth chose to end her missive – Cor Rotto – Heart Broken.

Elizabeth’s words give us a pretty clear indication of her affection for Catherine, but what isn’t as clear is when this letter was written and, by extension, when the Knollys family fled England. Many historians have placed the date of the Cor Rotto letter to the autumn of 1553. I agreed with the assumption that the Knollys fled based on this date initially due to a piece of research I came across in Queen Elizabeth I: Selected Works edited by Steven W. May. May indicates that the scribal copy in the Catalogue of Lansdowne Manuscripts in the British Museum included a leaf endorsed in Lord Burghley’s hand, “1553 Copy of a letter written by the Lady Elizab; Grace to the Lady Knolles.” Knowing the articulate Lord Burghley’s close connection to Elizabeth, I could think of no better source than he.

On the surface, a date of 1553 seems to be accurate. Queen Mary had already ascended the throne and we have record of Francis Knollys going abroad in September 1553. It would seem natural that Catherine would accompany him. However, a closer look at Catherine’s reported births gave me pause. Per Francis Knollys’ Latin Dictionary, we know that Francis the younger was born August 14, 1553. Knowing the intricacies of birthing procedure in Tudor England, it seemed very unlikely to me that Catherine would be setting off on such a journey only a month after the birth of her latest child. It is possible that her churching had not even taken place by the time that Francis left so she may have even been in her confinement.

As we follow the trail of historical documents, Francis surfaces in Geneva in November of 1553. A letter dated November 20 from John Calvin to Pierre Viret details a visit from Sir Francis and his son, Henry and praises Henry for his ‘piety and holy zeal’. There is no mention of Catherine, but that isn’t enough to prove that she didn’t accompany her husband and son because it is highly unlikely that she would have been invited to the audience with Calvin.

This is the last documentation we have of Sir Francis abroad until the winter of 1556 when he is enrolled as a student at the University of Basle. In 1554, Queen Mary appointed Sir Francis as Constable of Wallingford Castle. While being out of the country wouldn’t necessarily preclude him from carrying out his duties, we can safely assume that he was home by October of 1554 in time for Catherine to, once again, be with child.

The first documentation we have of Catherine abroad is in June 1557. She is mentioned with Sir Francis as a member of John Weller’s household in Frankfurt with a maid and five of their children. Prior to this, as I stated earlier, we find Sir Francis listed as a student at the University of Basle in 1556 where he is living in a dorm environment with several other male students. An environment that Catherine was definitely not living in.

Though the dating on Elizabeth’s poignant letter would indicate that Catherine fled 1553, as many historians have assumed, the evidence we have seems to point to a much later date. The question then is whether the letter is misdated or there was a miscommunication with Elizabeth regarding the departure of her cousin.

While the date of a letter might not seem to be of the highest significance in the grand scheme of history, for a novelist it can change the entirety of a story. Did the Knollys family flee immediately because the fear of their new queen was great enough to risk Catherine’s health or was the threat deemed low enough that Sir Francis felt comfortable leaving his family in England while he scouted the new settlements?

Unfortunately, the players no longer live to tell the tale so we have to take into consideration the surrounding circumstances to come to a fair conclusion. I was not convinced that Catherine fled with her husband and son in 1553, but I was also not convinced that a man like Burghley would make a mistake of at least three years in the dating of Elizabeth’s correspondence.

Like any other writer, I tried to imagine myself in the early months of Mary’s reign. In the environment of chaos and fear, it seemed almost certain that misinformation would be common as plans were made by the Reformers in this new and untested reign. The conclusion I came to is that Francis may have initially planned to take Catherine and their family with him, but decided at the last minute that the threat from Queen Mary wasn’t as great as he had anticipated.

Any number of conclusions can be drawn from the information we have, but the one thing we can be sure of is the high regard in which Elizabeth held her cousin, Catherine and the deep grief she felt at the news of her departure. Elizabeth was sure to make good on her word. Upon the return of Francis and Catherine to England, Francis was immediately made a Privy Councilor and given the posts of Vice Chamberlain of the Queen’s Household and Governor of Portsmouth. Catherine found herself serving the Queen in the Privy Chamber and would go on to be First Lady of the Bedchamber and one of the queen’s closest confidantes.

References:

(2005) Queen Elizabeth I: Selected Works edited by Steven W. May.

Garrett, Christina Hallowell (1938/1966/2011) The Marian Exiles: A Study in the Origins of Elizabethan Puritanism

Adrienne Dillard, author of Cor Rotto: A Novel of Catherine Carey, is a graduate with a Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Studies with emphasis in History from Montana State University-Northern.

Adrienne has been an eager student of history for most of her life and has completed in-depth research on the American Revolutionary War time period in American History and the history and sinking of the Titanic. Her senior university capstone paper was on the discrepancies in passenger lists on the ill-fated liner and Adrienne was able to work with Philip Hind of Encyclopedia Titanica for much of her research on that subject.

Cor Rotto: A Novel of Catherine Carey is her first published novel.

January 19, 2015

Dear Cousin: John Surratt’s Letters to Bell Seaman

On at least five occasions, John Surratt, the youngest son of Mary Surratt, put pen to paper to write to his second cousin, Isabel (“Bell”) Seaman, who lived with her family in Washington, Pennsylvania.

The first three letters (the second has no year) were written by John from his family’s tavern in Surrattsville, Maryland, where he lived with his mother and his older sister, Anna. (The oldest of Mary Surratt’s three children, Isaac, was fighting for the South in Texas.) Following the death of Mary’s husband in 1862, John took over his father’s position as the local postmaster, but lost it in November 1863 due to disloyalty to the Union. Despite his confidence in his first letter that he would gain his position back, he never did, as the government was quite right to have its suspicions about young John, who would soon be carrying illicit mail for the Confederacy. Indeed, the tavern itself was a “safe house” for those running the blockade between the Union and the Confederacy.

In the fall of 1864, Mary Surratt made the momentous (and utterly disastrous) decision to lease the tavern and to move to Washington, D.C., where her husband had purchased a house at 541 H Street some years before. Mary took in boarders at the house, two of whom, Nora Fitzpatrick and Mary Appolonia Dean, are mentioned in John’s fourth letter. (For those of you who remember the cat-naming contest on this blog last year, this letter is the source for Nora’s cat.) The most notable aspect of John’s fourth letter, however, is its breezy mention of “J. W. Booth,” who in the past few weeks had become a frequent caller at the boardinghouse. His visits were no secret, but his purpose was: he and John Surratt were plotting to kidnap President Lincoln, which they would attempt a little over a month after John wrote to his cousin. Their scheme failed, however, when the President changed his plans.

On April 3, 1865, the day that Richmond fell, John Surratt, traveling from Richmond to Montreal with messages from the dying Confederacy, stopped at his mother’s boardinghouse in Washington. Believing that federal authorities were looking for him, he spent just a couple of hours at the boardinghouse before checking into a hotel. The next day, he left Washington on his way to Canada. He never saw his mother again.

Four days after John Surratt wrote his fifth letter to Bell Seaman from Montreal (omitting his surname), President Lincoln was shot, and John Surratt was suspected of having a hand in his murder. Among those who would be visited by federal authorities over the next few days was young Bell Seaman, whose letters from John were seized. Bell herself wrote a letter to Anna Surratt on April 20, telling her that John’s April 10 letter had been seized and that she believed that the letter’s Montreal address cleared John of the President’s murder. Bell’s letter was seized from the post office before it reached Anna, who by this time was being held in prison with her mother.

John’s claim in his fourth letter that he was going to Europe, though it proved untrue at the time, was prescient, for after his mother was hanged in July 1865, John fled Canada and went overseas, where he remained until he was finally captured and tried in 1867. The jury was unable to reach a verdict, and after an attempt to try him on another charge failed due to a technicality, John went free. Did he resume his correspondence with his cousin Bell? If he ever did, it was probably not with the flirtatious banter of before, as Bell married an Alexander Murray Henry in 1870, while John himself married Mary Victorine Hunter in May 1872. John lived until 1916, but Bell did not survive the 19th century; she died in May 1886, a month before her husband, who was working on the Panama Canal, died in Colombia.

Letter 1

Surrattsville, Maryland, December I6, 1863.

Miss Bell Seaman: —

Dear Cousin — “To live, is to learn,” which has been fully verified by the contents of your rather surprising letter. I must confess, my dear Cousin, that your letter was short, sweet, and to the point. Unkindness is something, Cousin Bell, I have never yet been willfully guilty of, yet no doubt you construed my letter to that effect. “Judge ye not, and ye shall not be judged,” is a wise maxim, and one to which I always well look. “Look before you leap.”

“Satisfied in my conclusions,” is the sentence in which you find so much fault. Well, ma chère Cousin, to explain those four words, it is necessary to retrace our steps to a certain letter you wrote me, which contained something about “having more principle than to hold an office under a Government you pretend to despise.” In fact, you concluded that I was a hot-headed rebel, one belonging to the horned tribe, for they tell me they have horns, and that I ought not to hold an office under this poor busted up Union, consequently my being superseded, “satisfied you in your conclusion.” Is it not so, my dear Cousin ? Do tell me, won’t you ? I sincerely hope now, Cousin, that you are really satisfied in your conclusions about my meaning.

Anna started for Steubenville, Ohio, last Monday week, and has arrived safely, but I believe lost her trunk. I arrived from Washington a few hours ago, and found your letter awaiting me. I have proved my loyalty, so that it cannot be doubted, and will regain my office as P. M. Joy is mine! Cousin Bell, I expect you think I am a hard case. Without doubt I am the crossest, most ill-contrived being that ever was. Just ask Anna, when you see her, for a description of your Cousin.

Pardon my conclusion, but I am getting really sleepy. It is now ten o’clock, an hour after my bed-time, for I go by the old saying, “Early to bed, and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise.” Ma sends her love to you and family. Write soon, as nothing gives me greater pleasure than to receive a letter from you.

Your Cousin,

J. Harrison Surratt

Letter 2

Surratt’s Villa Md.

May

Cousin Bell,

It seem as if our correspondence is destined to be stopped, yet I will make another attempt in the hope that I may succeed in eliciting a few lines from you. Anna told me that you had gone to Steubenville to school. No doubt you are already beginning to count the days to your vacation; even hours–minutes. That was I used to do when I was at school.

“Tell John Surratt I’m mad with him” was the very hard message I received upon meeting my deus letters sent to me by my very dear cousin Bell. I’m in hopes you will not be put in the insane asylum, where all mad people are generally placed. Cos you will please excuse this scrawl, as my pen will scarcely write at all, and I have the shakes so badly, by seeing a certain young lady pass by, in company with my ___ Charlie. We are all very well, with the exception of your humble servant, who has at present a severe attack of the spring fever. Half past nine and Anna not out of bed yet. What do you think of that? That is her usual hour. I’m afraid you are the same way inclined. Cousin Bell write to me if you please. Ma & Anna send their love to you and family.

Your cousin

Jno. Harrison Surratt

Letter 3

Surratt’s Villa, Maryland, August 1, 1864.

My Dear Cousin Bell — You ask me if we have warm weather in Maryland, My Maryland. If you have it to such a degree as you represent it, up North, what must it be in our hot-headed South? Yes, Coz, if we had you down here we would soon convert yon into “sugar,” and then use you to sweeten our dispositions. You know ’tis the extremely hot weather that makes us “Rebs” so savage, cruel, and disagreeable. Yes, Cousin Bell, it is so warm that we can neither eat, sleep, sit down, stand up, walk about, and in fact, to sum the whole in a nutshell, it is too warm to do any thing.

So you think I have a great deal of assurance. I am sorry to say you are the first one that ever told me so. On the contrary, I am a very bashful, and perfectly unsophisticated youth. As every thing pleases you, I am overjoyed to know that you are pleased with me, as very few young ladies take a fancy to me. I am really delighted. You have told me more than ever woman dared to tell. Coz. Bell, you ask me why I do not get married? Simply because I can find no one who will have me. Often have they vowed, yes. But —

“This record will forever stand — Woman, thy vows are traced in sand.” — Bryon.

If you know of any lovely angel, in human form, desirous of a “matrimonial correspondence,” just tell her to indite a few lines to your humble Cousin, and I can assure her she will not be sorry for it.

August 10th. — Well, Coz., I have just been on a visit of a week’s duration. It always takes me about two weeks to write a letter. Ma and Anna are sitting in the hall enjoying the evening breeze, whilst I am sitting over my desk, almost cracking my brain in order to find something to fill up these pages, for, Cousin Bell, you must have perceived, long before this, that I am a poor letter writer. I had almost forgotten to tell you that I called on your friend. Mr. Wm. Underwood, at the Carver Hospital. He has nearly recovered from his wound, though it has not yet quite healed. He intended going home in a week or two, and perhaps he may be there now, as it has been over a week since I saw him.

Have you heard from your Uncle James lately ? There has been some very hard fighting out West recently, and you know, Cousin Bell, that the foe has very little regard where he directs his bullets. May God preserve him, and grant that he may see the end of this unholy war without harm. At what time does your vacation arrive ? Doubtless you look forward to that time with a great deal of impatience.

I am very sorry to think that it is your intention to become an old maid. The horrible creatures! curses upon society! a perfect plague! always meddling with affairs that do not concern them ! This is my opinion of old maids. I express it to you, because you have not yet arrived at that state of misery and despair. They are looked upon down our way as unnatural beings — something forsaken by God, man, and devil. So beware! Coz., I met a gentleman from Washington County, Pennsylvania, by the name of Stevenson, who is very well acquainted with the name of Surratt — so he says. Do you know any thing of him ? He is a very nice man, and a perfect gentleman. Have you heard any thing of the Rebel Captain, I have not heard from him for some time?

Really, I must bring my tiresome letter to a close. Every thing looks like starvation. Very encouraging, is it not? I hope you will answer soon, as nothing gives me greater pleasure than to receive a letter from yon. Cousin Bell, I am not prone to flatter, so you must believe what I say. Ma and Anna send their love to you. I wish you knew Ma, I know you would like her. Neither of us is like her. My brother resembles her very much. He is the best looking of the family. That is saying a good deal for myself. Excuse this miserable scrawl, as I have to dip my pen in the stand at every word. Anna has just commenced playing the “Hindoo Mother.” I would advise you to get it. It is really beautiful. Good-by. I hope to see you before many months.

Your Cousin,

J. Harrison Surratt.

“To whom shall we Grant the Meade of praise?” Hal ha!

Letter 4

Washington, D. C, February 6, 1865.

Miss Bell Seaman : —

Dear Cousin — I received your letter, and not being quite so selfish as you are, I will answer it, in what I call a reasonable time. I am happy to say we are all well, and in fine spirits.

We have been looking for you to come on with a great deal of impatience. Do come, won’t you ? Just to think, I have never yet seen one of my cousins. But never fear, I will probably see you all sooner than you expect. Next week I leave for Europe. Yes, I am going to leave this detested country, and I think, perhaps, I may give you all a call as I go to New York. Do not be surprised, Cousin Bell, when you see your hopeful Cousin. Truly you may be surprised.

I have an invitation to a party, to come off next Tuesday night. Anna and myself intend going, and expect to enjoy ourselves very much. I have been to a great many this winter, so that they are beginning to get common; but as this is something extra, I looked forward with a great deal of impatience. I wish you were, in order that I might have the pleasure of introducing you to regular country hoe-down. I know you would enjoy it.

There is no news of importance, save the burning of the Smithsonian Institute, which, of course, you have heard of. His Excellency Jefferson Davis and Old Abe Lincoln couldn’t agree, as sensible persons knew beforehand; and now I hope people are satisfied, and hope they will make up their minds to fight it out to the bitter end.

“Show no quarter.” That’s ” my motto.”

Cousin Bell, try and answer me in a few days at least, as I would like very much to hear from you before I leave home for good. I do not know what to think of our mutual Miss Kate Brady. Byron justly remarks —

” This record will forever stand —

“Woman, thy tows are traced in sand.”

I have just taken a peep in the parlor. Would you like to know what I saw there ? Well, Ma was sitting on the sofa, nodding first to one chair, then to another, next the piano. Anna sitting in corner, dreaming, I expect, of J. W. Booth. Well, who is J. W. Booth? She can answer the question. Miss Fitzpatrick playing with her favorite cat — a good sign of an old maid — the detested old creatures. Miss Dean fixing her hair, which is filled with rats and mice.

But hark ! the door-bell rings, and Mr. J. W. Booth is announced. And listen to the scamperings of the —. Such brushing and fixing.

Cousin Bell, I am afraid to read this nonsense over, so, consequently, you must excuse all misdemeanors. We all send love to you and family. Tell Cousin Sam. I think he might write me at least a few lines.

Your Cousin,

J. Harrison Surratt,

541 H Street, between 6 and 7 Streets.

Letter 5

Montreal, CE April 10th 1865

My dear Cousin

You may be surprised to receive a letter from me dated Montreal, yet it is so. I have been here for a week or so. I hope you are well. It has been so long since I heard from you that you seem almost a stranger.

Canada is a fine country for ice, snow and cold weather, which I yet experience to a great extent. Montreal is really a beautiful city and what pleases me more there are a great many pretty girls here. It is more than probable that I shall lose my heart with some of them and then I ask myself have I one to give away? The answer comes back fully satisfactory. It is more than probable I shall give you a call as I return from Canada, but is very doubtful, as I am always in a hurry. I supposed you have not yet moved.

I am enjoying myself to my heart’s content. Nothing in the wide world to do but visit the ladies and go to church. How are you Grant and Lee? I always knew the old Confederacy would to up the spout, and the flag that Washington left us would wave again o’er North and South.

For special reasons you can direct your letters as below. Write soon as I would like to hear from you all very much.

Your cousin

John Harrison

St. Lawrence Hall

Montreal, CE

Sources:

“Away from Home: Alexander Henry Dies and Leaves His Children a Fortune,” Wheeling Register, August 28, 1886, p. 4.

General L.C. Baker, History of the United States Secret Service, 1867 (letters 1, 3, and 4)

William C. Edwards and Edward Steers, Jr., The Lincoln Assassination: The Evidence (letters 2 and 5).

William Seaman, “Bell’s Letters,” The Surratt Courier, March 1978.

December 23, 2014

Merry Christmas, and An Excerpt!

Merry Christmas, and a Happy New Year! I’ve been busy revising my forthcoming novel, Hanging Mary, for the publisher. Here’s a seasonal excerpt for you, set at Mary Surratt’s boardinghouse 150 years ago on Christmas Eve, 1864:

The men had gone out the previous night, Mr. Weichmann to buy some presents for his sisters and Mr. Surratt to offer him his invaluable advice, as he put it, and had stayed out until past their usual hour. Mr. Surratt yawned as he sat down. “Ma, you didn’t wait up for us last night.”

“Should I have? I trusted that Mr. Weichmann would keep you out of trouble.”

“If you had, I would have told you who I met last night.”

“So now you can tell all of us,” Anna said.

“As I was planning to. But you must guess. Who do you think Weichmann and I met in the street?”

“The President?”

“Old Abe? Who cares? No, try again.”

“Mrs. Sprague?” Anna suggested, naming Kate Chase, the recently married daughter of the even more recently appointed Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. One of the most beautiful women in Washington, and now one of the richest, her wedding had been the talk of the town last year.

“No, those dainty slippers would never touch the mud, although I’d much rather meet her on the street than Old Abe any day. You try, Miss Fitzpatrick.”

I shrugged. There were so many important people in Washington one might glimpse. “John Wilkes Booth,” I said idly.

“Why, how did you guess?”

I dropped my fork. “Him? The actor? Him?”

If you had put a young lady from New Orleans, a young lady from Boston, a young lady from Richmond, a young lady from Cleveland, a young lady from Baltimore, and a young lady from Washington together, the one thing they would have agreed upon, before they scratched each other’s eyes out, was that John Wilkes Booth was one of the handsomest men in America. Any woman worthy of her sex, and I was no exception, could rhapsodize for hours upon his curling black hair, his soulful black eyes, his beautiful skin, and his fine physique—even those women who hadn’t actually had the privilege of seeing him in person. I was among the lucky ones, for the previous year, he had played at Ford’s Theatre, and as I had been at school in Georgetown at the time, I had plagued my father until he agreed to take me. As the play had been Richard III, Mr. Booth’s looks had not shone to their best advantage, since he was forced by the role to assume a hunchback and to scowl a great deal. Even so, I had had to repress a smile when Lady Anne informed Richard that he was a foul toad. I had gone to bed that night thoroughly convinced that such a lovely man could not have possibly killed his nephews, although of course the play said that he did.

“You truly met John Wilkes Booth,” I repeated.

“Yes. Mr. Weichmann and I were by Odd Fellows Hall when we saw Dr. Mudd from Bryantown. You probably know Dr. Mudd from when you were at school there, Anna.”

“I do, he treated one of my classmates when she fell sick. But what’s Dr. Mudd to me? I want to hear about Mr. Booth.”

“Well, to get to the Booth, you must step through the Mudd. Dr. Mudd hailed us and introduced his companion—who, if you’re clever, you might deduce was Mr. Booth.”

“I thought his name was Mr. Boone at first,” Mr. Weichmann admitted.

“Oh, Mr. Weichmann.” Anna sighed. “You are such a stick.”

“How does he look close up?” I asked.

“I’m not a connoisseur of men’s looks, Miss Fitzpatrick, but I think most would call him very handsome. Perhaps more so in person than onstage, since there’s not the gaslight or the makeup to intrude.”

I gazed raptly into space.

“So what happened next? Did you continue on?”

“Goodness, no, sister! It gets better. Mr. Booth invited the three of us to his rooms at the National Hotel, and we sat and had milk punch—”

“And smoked cigars,” Anna said. “I smell them on you and Mr. Weichmann.”

“Yes, well, we men like our cigars, you know. If you wish to marry you will have to learn to tolerate them, or else die an old maid. Anyway, we drank our milk punch, smoked our fiendish cigars, and talked awhile. Afterward, we went onto Dr. Mudd’s rooms at Pennsylvania House—he came to town to see some relatives—and talked some more. And that is it, except that Mr. Booth has promised to call upon us here sometime.”

“Truly?”

“So he said. Mind you, he didn’t say precisely when.”

“We shall have to keep the place spotless at all times, Ma,” Anna said. “Thank goodness the furniture in the parlor is new—I couldn’t bear to see Mr. Booth sitting here in shabby surroundings.”

“He travels a great deal, and must stay in all sorts of places,” I said. “Perhaps he will be willing to make some allowances.”

“Nay, Miss Fitzpatrick, that will not do. We must be in readiness to receive him at any possible moment, and the house must be in a state of nearly palatial splendor.” Mr. Surratt studied his egg thoughtfully. “Perhaps we should not serve any meals here, lest the smell of cooking offend him.”

“Johnny, stop tormenting the young ladies,” Mrs. Surratt said. “This is a perfectly respectable house, and a clean one too, if I must say so myself, and there is no reason Mr. Booth, if he comes, should not be pleased. He will not, of course, be expecting a grand house.”

“Well, I might have added a staircase or two in my description of it, and a bay window. Is it too late to bring a builder over?”

November 15, 2014

Search Terms–They’re BAAAAACK!

what does Mary Boleyn look like today

In all honesty, probably not very good.

why they thought anne boleyn was a witch for kids

To be followed by “Why They Thought Anne Boleyn was an Adulteress for Kids.”

It might be good to narrow this one down just a tad.

how ot adress a letter to henry vii

“Dear Usurper” might be inadvisable.

mini richard feet

Perfect for hanging on the Christmas tree.

I am in love with richard the third

Hallmark is working on a card for this now.

Richard III tattoo

They say it’s getting all of the little pointy things on the crown done that hurts the most.

anybody with the last name higginbotham naked photos

Plainly an ill-advised ploy to check for Richard III tattoos.

November 12, 2014

Excerpts from Hanging Mary!

Last night, after a great deal of cutting and pasting of HTML, I managed to create a spot on my website’s menu bar for Hanging Mary–along with excerpts! Check them out here. I’ll be adding a “Further Reading” link for the book soon as well.

You may notice that I’ve taken some pages off my website, as they duplicate posts on this blog and are making the website unwieldy (particularly when cutting and pasting HTML is required). If you haven’t noticed, that’s yet another reason for removing the pages!