Susan Higginbotham's Blog: History Refreshed by Susan HIgginbotham, page 9

November 11, 2014

Sister to Two Kings: Anne, Duchess of Exeter

(In an attempt to streamline my website and avoid duplication, I am going to be deleting some pages from my website and posting them on my blog instead. Here’s an article on my website that appeared some time ago.)

Anne, Duchess of Exeter, sister to Edward IV and Richard III, was the oldest of the children of Richard, Duke of York, and Cecily Neville. She was born on August 10, 1439, at Fotheringhay—the same castle in which her youngest surviving sibling, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, would be born in 1452. In 1446, when she was six, she was married to fifteen-year-old Henry Holland, who would shortly become the second Duke of Exeter. The Duke of York offered a large marriage portion—4,500 marks–probably because Henry VI was childless at the time, putting the young Henry Holland in line for the throne. Only 1,000 marks of the portion were paid. It was a poor investment in any case, for Exeter proved to be solidly Lancastrian. He also seems to have been exceptionally quarrelsome, falling out with his father-in-law and with all manner of people during the 1450’s and serving time in the Tower. Among those with whom he seems not to have gotten on well with was his own wife. The couple had one child, Anne Holland, but evidently lived most of their lives apart.

Exeter was attainted in 1461 and eventually joined Margaret of Anjou in exile abroad. Meanwhile, the Duchess of Exeter was granted the duke’s Holland inheritance for life. For a brief time beginning in 1464, she had the custody of the nine-year-old Harry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham, a ward of the crown. Edward IV married Elizabeth Woodville later that year. Probably around Easter 1465, he transferred Harry to the care of his queen, whose youngest sister Harry married.

The Duchess of Exeter’s young daughter, Anne, had been promised in marriage to George Neville, a nephew of Richard Neville, the Earl of Warwick. George at the time had the potential to be a quite wealthy young man, as the Earl of Warwick had no sons and the Neville lands were entailed in the male line. Elizabeth Woodville, however, wanted the heiress Anne for her own eldest son, Thomas Grey. She paid the Duchess of Exeter 4,000 marks to break the contract with the Neville family. This was certainly sharp business practice on the queen’s part, but it was hardly unusual for the times: rich young heirs and heiresses were hot commodities. Certainly Elizabeth could not have made the arrangement without the approval of Edward IV, the Duchess of Exeter’s brother. The Duchess of Exeter was no less keen to look after her own interests than the queen: as part of the marriage arrangements, the Holland inheritance was settled on little Anne, with a remainder interest in the duchess herself and in the heirs of her own body.

During the Readeption of Henry VI in 1471, the Duke of Exeter moved back into his London house of Coldharbour, which had been granted to the Duchess of Exeter during his exile. Probably the Duchess of Exeter prudently took herself off to one of her other residences during this period.

The Duke of Exeter fought with the Earl of Warwick’s troops at Barnet in 1471. There he was badly injured and was left for dead on the battlefield until a servant discovered signs of life in him and took him to a surgeon. He was later smuggled into sanctuary at Westminster Abbey, but Edward IV removed him and imprisoned him in the Tower of London. While her husband was still a prisoner, in 1472, the Duchess of Exeter took the opportunity to have their marriage annulled on November 12. Presumably the Church did not recognize allegiance to the house of Lancaster as a basis for an annulment, but the actual grounds are not known.

The duchess soon remarried. Like her brother the king, she married a social inferior—in her case, Thomas St. Leger, a knight who may been her lover for some time. As Anne Crawford notes, Edward IV had been showing St. Leger a great deal of favor for many years, including a substantial grant of eight manors in the early 1460’s. He was no gigolo, however; he served Edward IV militarily and administratively for years.

In 1474, the duchess’s child by the Duke of Exeter died, triggering the duchess’s remainder interest in her lands. The following year, Edward IV set off on an expedition to France, which ended in a peace treaty instead of the anticipated military engagement. Anticlimactic for most people, the expedition was fatal to one—the Duke of Exeter. He had been released from the Tower and allowed to join the expedition, presumably so he could prove his loyalty to the king in battle, but on the return journey, he was drowned. Whether his death was accidental or murder is unknown, though rumors of the latter abounded.

The Duchess of Exeter had a daughter by Thomas St. Leger in late 1475 or in January 1476. The little girl, named Anne like her mother and her deceased half-sister, soon became motherless, for the duchess died on January 12 or 14, 1476, possibly in or soon after childbirth. She was buried in the Chapel of St. George at Windsor.

Following his wife’s death, St. Leger remained on good terms with his brother-in-law the king. In 1478, as part of the festivities surrounding the marriage of Edward IV’s younger son to Anne Mowbray, he was made a Knight of the Bath. He served as Edward IV’s controller of the mint and as master of the king’s harthounds. In 1481, he was granted a license to found a perpetual chantry of two chaplains at the Chapel of St. George, in memory of his wife. He never remarried.

Thomas Grey, the Marquess of Dorset, who had married the Duchess of Exeter’s eldest daughter, Anne Holland, had remarried after the young girl’s death and now had a son of his own, who was contracted to young Anne St. Leger. The arrangement under which Anne was deemed the heir to the Exeter estates was formalized in an Act of Parliament in January 1483. Richard Grey, Dorset’s younger brother, also benefited from the Act, in which part of the Exeter inheritance, worth about 500 marks, was set aside for him. The loser in this transaction was Ralph, Lord Neville, who was the heir of the Holland family, although since the Duke of Exeter had been attainted, the crown had some justification in treating his inheritance as it liked.

This arrangement fell apart when Richard III took the throne in July 1483. Thomas St. Leger attended the new king’s coronation and was given cloth of silver and velvet for the occasion, but he was soon afterward deprived of his positions of master of harthounds and controller of the mint. His daughter, meanwhile, was ordered to be handed over to the Duke of Buckingham. Perhaps, as Michael Hicks has suggested, Buckingham had the girl in mind as a bride for his own eldest son. This never came to pass either, of course, for both St. Leger and Buckingham ended up in rebellion against the new king.

St. Leger has been criticized for his lack of loyalty to Richard III, but Richard, having removed him from his offices, had given him no reason to remain loyal. Moreover, St. Leger had been unshakably faithful to Edward IV and, like many of the other rebels, was undoubtedly distressed at Edward V having disappeared from sight after having been deprived of his crown.

Unlike many of the rebels, who gave up the fight after Buckingham’s execution on November 2, St. Leger continued the fight in Exeter, but was ultimately captured. He was executed on November 13, 1483, at Exeter Castle, despite the offer of large sums of money on his behalf. St. Leger, described by the Crowland chronicler as a “most noble knight,” was buried with his wife Anne at Windsor. They are depicted below:

One last bit of business remained: the disinheritance of Anne St. Leger. In 1484, Richard III’s only Parliament overturned the acts under which Anne had been declared the heir to the Exeter estates. The beneficiary, however, was not the Exeter heir, Ralph Neville, but the crown itself.

Poorer but still well connected, Anne St. Leger ultimately married Sir George Manners, Lord Ros. Their eldest son, Thomas Manners, became the first Earl of Rutland. It is this earl’s countess who is credited with telling the supposedly sexually naive Anne of Cleves, “Madam, there must be more than this, or it will be long or we have a duke of York, which al this realm most desireth.”

In September 2012, the skeleton of a man supposed to be Richard III was uncovered at Leicester. DNA from the descendants of the Duchess of Exeter and her second husband will be used to identify the remains—thus, ironically, Thomas St. Leger will hold the key to identifying the body of the man who sent him to his death.

November 4, 2014

Finished! And a Timely Excerpt

I just hit “send” on the completed manuscript of my Mary Surratt novel, Hanging Mary. There will be a few tweaks to come, no doubt, but I’m pleased with how it turned out. (The characters would not echo my sentiments.)

Since I finished this up on Election Day in the United States, I’d thought I’d post a timely excerpt: Mary Surratt, her daughter Anna, and her boarders Nora Fitzpatrick and Louis Weichmann, awaiting the results of the 1864 Presidential election between incumbent President Abraham Lincoln and General George B. McClellan.

“Whom did you vote for, Mr. Weichmann?” Anna asks.

“Now, Anna,” I say, “That is Mr. Weichmann’s sacred right not to say.” I am curious to hear the answer myself, however.

“I voted for the man I thought would serve the country best,” Mr. Weichmann says.

“I hope President Lincoln is defeated.” Anna puts in. “He is a hideous man.”

”Father saw him once. He said he has very kind eyes.”

”Your father sees everyone, Miss Fitzpatrick.”

”Indeed, he does. There’s hardly a soul in Washington he doesn’t know, at least by sight. But he only glimpsed the President riding to his summer place. I rather hope he wins.” Miss Fitzpatrick puts her chin on her hand and sighs. “It is such a pity to live in the capital city, and have to find out the election results in the morning just as if we were in Kansas or something. I wish we could stand out by the White House and wait. If we had an escort, we could go.”

This is such a naked appeal to Mr. Weichmann, I cannot help but smile and wonder how many such sad-eyed petitions Mr. Fitzpatrick has heard over the years. Fortunately, Mr. Weichmann reacts as hoped. “I can escort you and the other ladies there, if you like.”

”Oh, would you please, Mr. Weichmann?”

“I’ll go too,” Anna says. “Even though I won’t be able to endure it if that creature wins.”

”Which he probably will,” I warn her.

”It will be a long wait, perhaps, and it is a miserable night,” Mr. Weichmann adds.

“We’ll wrap up well,” Miss Fitzpatrick promises. “Mrs. Surratt, won’t you come? It will be lonely sitting here all by yourself.”

Touched, I say, “I will be delighted to.”

So, bundled up and carrying umbrellas, which knock against each other as we make our way down the muddy street, we head under Mr. Weichmann’s protection to the White House, in front of which a crowd of white and black, male and female, has already gathered. The club rooms and the hotels, Mr. Weichmann tells us, are the best place to await news, but they are not suitable places outside of which for ladies to linger.

Even where we stand, however, news arrives regularly, in the form of men, some more sober than others, who come to yell out the latest returns. Most are in favor of President Lincoln, which invariably meet with chorus of “Huzzah!” in which Miss Fitzpatrick at first refrains from joining out of consideration for Anna, though even the latter appears to be caught up in the atmosphere. By the fifth or sixth time, however, Miss Fitzpatrick forgets herself and cheers with the rest.

”I wish Johnny were here,” my daughter says, stamping her boots to keep her feet warm. “How sad to be at that dreary tavern when there is so much excitement here.”

As the night wears on and it becomes clear that the President’s re-election is assured, we are preparing to go home when a group of men, bearing the Pennsylvania flag, push their way through the crowd and began to sing:

Yes we’ll rally round the flag, boys, we’ll rally once again,

Shouting the battle cry of freedom,

We will rally from the hillside, we’ll gather from the plain,

Shouting the battle cry of freedom!

The Union forever! Hurrah, boys, hurrah!

Down with the traitors, up with the stars;

While we rally round the flag, boys, rally once again,

Shouting the battle cry of freedom!

”There is a Southern version of this song too,” Anna hisses. “Johnny taught it to me.”

”For goodness sake, child, don’t sing it here.”

“I’ll hum it,” Anna decides, and does so.

The Pennsylvanians having stopped singing, and Anna humming, the former begin yelling for the President to appear—which, presently, he does, leaning his head out the window as the crowd yells and Miss Fitzpatrick gives a yelp of delight.

”Hideous!” mutters Anna.

”Oh, hush, you’ll get us cast into prison,” Miss Fitzpatrick says good-naturedly. “He looks kind, just as Father said. Don’t you think so, Mrs. Surratt?”

”I can’t make out his features,” I admit. “My vision is not like it used to be.”

We fall silent as the President begins speaking. “I am thankful to God for the approval of the people, but, while deeply grateful for this mark of their confidence in me, if I know my heart, my gratitude is free from any taint of personal triumph. I do not Impugn the motives of anyone opposed to me. It is no pleasure to me to triumph over any one. But I give thanks to the Almighty for this evidence of the people’s resolution to stand by free government and the rights of humanity.”

“The rights of darkies,” mutters Anna, and turns away, her nose in the air, leaving us no choice but to follow her. As we walk home, pressing close to Mr. Weichmann as drunks weave too closely to us, I feel my own pang of sadness.

Lincoln has carried the State of Maryland.

October 29, 2014

Guest Post by Kathryn Warner: Edward II and the Despensers

I’m so pleased to welcome my friend Kathryn Warner for her new biography of Edward II. I’ve been looking forward to a book like this for years, and what better person than Kathryn to write it?

Kathryn and I first met online a number of years ago, when I published my first novel, The Traitor’s Wife, about Eleanor de Clare, Edward II’s favorite niece and the wife of his favorite, Hugh le Despenser the younger. Given that, what better topic for this guest post than Edward II and the Despenser family? Over to Kathryn:

King Edward II of England (reigned 1307 to 1327) is famous, or infamous, for his reliance on male ‘favourites’, the best known of whom is Piers Gaveston, whom Edward made earl of Cornwall and who was beheaded by a group of the king’s aggrieved barons in June 1312. The last of the favourites, Hugh Despenser the Younger, is not nearly so well-known, even though he was far more politically powerful than Piers Gaveston and helped bring about the king’s downfall and his own in 1326/27. Rather curiously, Edward II also had some kind of intense relationship near the end of his reign with Hugh Despenser’s wife – who happened to be his own niece, Eleanor de Clare.

Hugh Despenser the Younger was born sometime in the late 1280s as the elder son of Hugh Despenser the Elder, stepson of the earl of Norfolk and later earl of Winchester (1261-1326) and Isabel Beauchamp (1260s-1306), daughter and sister of earls of Warwick and first cousin of the earl of Ulster. Hugh the Younger made a splendid marriage in May 1306 when Edward I arranged and attended his wedding to his eldest granddaughter Eleanor de Clare, thirteen-year-old daughter of the earl of Gloucester and Edward I’s second daughter Joan of Acre. Hugh and Eleanor’s relationship seems to have been successful, as they had at least ten children together in their twenty-year marriage: Hugh, Edward, Gilbert, John, Isabel, Joan, Eleanor, Margaret, Elizabeth and an unnamed boy who died young in 1321.

Edward II was always very fond of Eleanor de Clare Despenser, his eldest niece and only eight years his junior. Early in his reign, he paid her expenses even when she was out of court, a sign of great favour, and in 1310 paid a messenger a generous sum of money for bringing him news of her. In 1311/12, and probably in the years before and after as well (records don’t survive), Eleanor was a lady-in-waiting in the household of Edward’s young queen Isabella of France. Edward also showed great favour to Eleanor’s father-in-law Hugh Despenser the Elder, twenty-three years his senior, who remained utterly loyal to him from the beginning to the end of his reign and whom he may have seen as a father figure. The king’s undoubted affection for Hugh the Elder and Eleanor, however, did not extend to Hugh Despenser the Younger, whom the king seems barely to have noticed before 1318. Hugh the Younger, for the first few years of Edward II’s reign, allied himself with his maternal uncle Guy Beauchamp, earl of Warwick, one of the king’s most implacable enemies, rather than with his royalist father. Hugh’s recklessness and disregard for rules – leaving England in 1310 to go jousting without royal permission, seizing possession of Tonbridge Castle in 1315, punching another baron in the face in front of the king in 1316 – cannot have helped to endear him much to Edward either.

All of that changed drastically in and after 1318, when the barons appointed Hugh as chamberlain of Edward’s household – a very influential position, as the chamberlain controlled access to the king, both in person and in writing. The later chronicler Geoffrey le Baker writes that Edward II was intensely indignant at this appointment as he hated Hugh, and although this is probably an exaggeration, it is apparent that the king had never been remotely fond of Hugh, even though the latter was his nephew by marriage (albeit only about three to five years his junior) and the son of one of his most loyal supporters. What followed next is a fascinating turnaround: By 1320, Edward had become infatuated with Hugh and fell over himself to do anything he could for him, however politically inexpedient. Hugh’s land-grabbing in South Wales, which Edward encouraged and facilitated, led to the Despenser War in May 1321 and the destruction of Hugh’s and his father’s lands throughout England and Wales, after which he and Hugh the Elder were perpetually exiled from the country in August 1321. Edward II, however, managed to bring them back to England in February 1322. Victorious over their baronial enemies, who were killed in battle, executed, imprisoned or fled the country, success went to Edward and Hugh’s heads, and for the next few years they proceeded to rule the country capriciously and tyrannically. Hugh, high in the king’s favour and untouchable, took any lands he felt like by illegal and quasi-legal methods, including his sister-in-law Elizabeth de Clare’s, and even imprisoned the young noblewoman Elizabeth Comyn until she consented to hand some of her lands over to him.

By the mid-1320s, Edward II and Hugh Despenser the Younger had hardly any allies left, and the country seethed with rebellion and discontent. Either unaware or uncaring of the grand forces ranged against them, Edward and Hugh seemingly went out of their way to make more enemies, and made the terrible mistake of alienating Edward’s queen, Isabella, who loathed Hugh, his intrusion into her marriage and his persuading the king to confiscate her lands and even banish her from his company. Isabella, sent to France in 1325 to negotiate a peace settlement between her husband and her brother Charles IV, refused to return, and with the king’s son and heir Edward of Windsor under her control, began a relationship or a political alliance with Roger Mortimer. He was an English baron who had escaped from the Tower of London in 1323, and was the king’s most dangerous enemy and a man whose family had a long vendetta against the Despensers. Isabella demanded that Edward send Hugh away from him, so that she could return to him safely. Edward refused. Pope John XXII sent envoys to king and queen to try to resolve their conflict. Still Edward refused to send Hugh away from him. In alliance with the count of Hainault and Edward II’s half-brother the earl of Kent, who loathed Hugh Despenser, Isabella and Roger planned an invasion of England to bring down Hugh and his father, now earl of Winchester. It is interesting to note that at the time of the invasion in 1326, the annals of Newenham Abbey in Devon referred to Edward and Hugh Despenser as rex et maritus eius, ‘the king and his husband’.

Edward II had another very close companion and ally in the mid-1320s: his niece, Eleanor Despenser, née de Clare. A Flemish chronicler stated openly that Edward and Eleanor were having an incestuous affair, and the later English chronicler Henry Knighton made the rather cryptic comment that while Isabella was in France in 1325/26, Eleanor was treated as though she were Edward’s queen. The evidence of Edward’s last chamber account of July 1325 to October 1326 indicates that the two were extremely close and regularly exchanged letters and gifts, spent considerable time together and dined together privately. In early December 1325 Edward, at Westminster, sailed along the Thames to Sheen to pay a quick visit to Eleanor, and gave her a remarkably generous gift of 100 marks (sixty-six pounds). A few days later, he made an offering of thirty shillings to the Virgin Mary to give thanks for the fact that God had granted Eleanor ‘a prompt delivery of her child’. Eleanor sent Edward some rich items of clothing at this time, and a little later sent him a palfrey horse with all equipment as his New Year gift. The two spent part of the summer of 1326 sailing along the Thames together and also spent time in Windsor. When Edward and Hugh Despenser fled from hostile London in early October 1326 following the invasion of his queen and Roger Mortimer, Edward left Eleanor in charge of the Tower, a sign of his trust in her. Edward II’s unpopular regime quickly collapsed in the face of opposition: Hugh Despenser and his father the earl of Winchester were grotesquely executed on the orders of Queen Isabella and Roger Mortimer on 27 October and 24 November 1326, and in January 1327, Edward was forced to abdicate his throne to his fourteen-year-old son Edward III. Eleanor Despenser was imprisoned, released then imprisoned again in the late 1320s, and died in 1337, having made a second marriage to William la Zouche, lord of Ashby in Leicestershire.

It is impossible to know for certain what kind of personal relationships Edward II had with Hugh and Eleanor Despenser, how he felt about them and how they felt about him, whether their relationships were sexual or romantic or not. It would be fascinating to know how Edward and Hugh’s relationship changed in and after 1318, how Edward became so dangerously infatuated with a man he had known for many years and to whom he had always previously been indifferent. It would also be fascinating to know whether he and Eleanor had a relationship which went beyond the usual one of uncle and niece. We can only speculate, but clearly both Hugh and Eleanor Despenser were very important people in Edward II’s life, and the king’s infatuation with Hugh and refusal to send him away even when faced with an invasion of his kingdom brought about his own downfall.

Kathryn Warner’s new book, ‘Edward II: The Unconventional King’, is available to buy now at the Amberley website and at Amazon US and Amazon UK. Visit Kathryn’s blog here.

Kathryn’s Blog Tour Schedule

28/10/2014 – Christy Robinson at Rooting for Ancestors blogspot will be posting a general introduction to Edward II and his ancestry, and a brief overview of his reign.

29/10/2014 – Peter at Medievalists.net will be posting a guest post about Edward II and his children.

30/10/2014 – Susan Higginbotham will be posting on her blog about Edward’s relationship with his niece Eleanor de Clare and her husband Hugh Despenser, his chamberlain and ‘favourite’.

31/10/2014 – Gareth Russell will be posting an author interview on his blog, ‘Confessions of a Ci-Devant’.

01/11/2014 – Jen has a blog about Piers Gaveston and will be posting a guest post by Kathryn about Edward and his relationship with Piers.

02/10/2014 – Annette at Impressions in Ink will be posting a guest post about Edward II’s household.

03/10/2014 – Becky Cousins at The Medieval World will be posting a guest post on ‘Edward II and his Rustic Pursuits’.

04/10/2014 – Olga at Nerdalicious will be finishing off the blog tour with an author interview and a prize giveaway!

October 28, 2014

Watch This Space!

Yes, things have been mighty quiet here, but for a very good reason: I am almost finished with my new novel, Hanging Mary (the official title). It’s the story of Mary Surratt, the first woman hanged by the United States government, and her young boarder, Nora Fitzpatrick.

Once Mary is duly hanged, l’ll be posting here more regularly and updating my sadly neglected website. And since my next two contracted projects are nonfiction books about Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, and Margaret of Anjou, you can look forward to a thoroughly eclectic mix of medieval/Tudor and American Civil War posts here. (Fun fact: Did you know that John Wilkes Booth spent several years of his childhood in a house named Tudor Hall, built by his actor father?)

In the meantime, here’s an old photograph of the house where much of the events of Hanging Mary take place: the Surratt boardinghouse at 541 H Street in Washington, DC (now 604 H Street, and home of the Wok and Roll Restaurant. Best Wok and Roll Google review: “Every time I go here, I feel like killing President Lincoln.”).

And last but definitely not least, my Edward II buddy from way back, Kathryn Warner, has just published a biography of—you guessed it—Edward II! She’ll be stopping by here on October 30 as part of her blog tour, so please remember the date!

September 22, 2014

Hand of Fire Blog Tour: A Guest Post by Judith Starkston

I’m pleased to be a part of Judith Starkston’s blog tour for her first novel, Hand of Fire. While this isn’t a period I’m well versed in, this guest post made me eager to learn more about it, and I bet you’ll be interested as well! Over to Judith:

The Trojan War: Myth or History?

I set my debut novel within the Trojan War. Hand of Fire tells Briseis’s story, the captive woman who sparked the bitter conflict between Achilles and Agamemnon and thus holds a central position in the plot of Homer’s Iliad. Despite her importance to the action of this war poem, she receives only a few lines and remains largely an enigma—so I gave her a long overdue voice and life.

While my purpose in writing Hand of Fire was to tell a compelling tale, I also wanted to reflect accurately the history of this time and place. At the very least, it seems fair to ask did a Trojan War ever happen or is Homer’s famous war the stuff of legend?

The ancient Greeks certainly viewed the war as something true from their long ago past, complete with a thousand Greek ships beached in front of the great walled city for ten years. The romantics among you will have to give up the numbers of ships and that long stretch of ten years because both sums are highly unlikely if not downright impossible. However, if you define “Trojan War” as a series of major and/or repeated attacks by Mycenaean Greeks on Troy at the end of the Late Bronze Age, then that seems historically possible. The evidence is by no means definitive, but it’s looking better all the time.

The evidence falls into two categories: textual and archaeological.

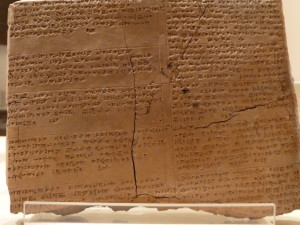

Textual? you say. What texts would those be? Clay tablets written in Hittite and several other languages with cuneiform script, which looks like closely-packed bird tracks. These Bronze Age archives have been found at sites throughout the area which is now modern Turkey, but the majority come from the capital of the Hittite Empire called Hattusa, not too far from modern Ankara. Troy, on the western coast of Turkey, was often a vassal state to the Hittite Empire and is a sort of cultural cousin to the Hittites.

While no tablets have been found in Troy, we have several treaties and letters from Hattusa that pertain to Troy, which the Hittites called Wilusa (a variant of Ilion, the other Greek name of Troy). Some of these also mention conflicts involving the Greeks, called Ahhiyawa by the Hittites. Unfortunately from the perspective of answering how historical the Trojan War was, none of these conflicts quite matches up to what we need.

In a couple cases it sounds like the Greeks fought with the Trojans against the Hittites. But in other cases, it appears the Greeks were the aggressors against the Trojans with the Hittites coming to Troy’s defense. One of these possibilities even has the tantalizing mention of a Trojan king named Alaksandu—so close to Alexander, of stealing Helen fame. With each of the tablets concerning Greeks and Troy, there are problems identifying the conflict as the Trojan War, as we know it.

However, this clay-based evidence does demonstrate that Greeks were causing trouble and fighting near Troy. It is reasonable to believe that there were numerous large and small conflicts over time that could have been collapsed into one epic war either to make a better tale or because over the centuries that’s how this conflict got remembered. The Hundred Years War was a messy series of conflicts, not one big war, and it did not last exactly one hundred years, so these Homeric “fudges” aren’t such a leap. Many scholars are willing to accept this understanding.

We are all hoping just the right tablet is sitting in one of the storerooms waiting to be translated. There are so many, and more coming from digs all the time. We may need patience not imagination to solve this question via texts.

Then there’s the archaeological evidence. Fortunately the site of Troy, which was disastrously excavated in the 19th century by Schliemann, has been rescued and given a modern “makeover” by Manfred Korfmann and his successors. We now can say some fairly definitive things about Troy and a possible Trojan War.

In short, the correct layer of Troy, dated to about 1200-1150 BCE, variously identified as VIIa or VIi (same level just two systems of labeling), was destroyed by a great fire caused by war. There are abandoned piles of catapult projectiles and unburied bodies, so we know the Trojans lost. They’d have picked up the valuable ammunition and stowed it away if they won, not to mention buried their dead. There are other destruction layers, at least one by earthquake, but this burning of VIIa seems to match what we need rather conveniently. This particular level has the most impressive fortification walls, large paved streets, skillfully squared stonework and all the other signs of a wealthy Bronze Age city at its peak. It also reveals a city under threat. The most vulnerable of the gates into the citadel was walled up and there are other signs of shoring up any weak spots in the defenses. Troy is a baffling site to the uninitiated, but when someone like Korfmann explains what all that jumble reveals, I hear a pretty darn good case. It helps that proving the Homeric connection was never Korfmann’s purpose, but he realized that this mattered to a lot of people, so he tried to summarize what the evidence said.

In a 2004 article for Archaeology, an online publication of the Archaeology Institute of America, Korfmann gave his answer to the question, “Did the Trojan War really happen?” In his final summary he put it this way:

“According to the archaeological and historical findings of the past decade especially, it is now more likely than not that there were several armed conflicts in and around Troy at the end of the Late Bronze Age. At present we do not know whether all or some of these conflicts were distilled in later memory into the “Trojan War” or whether among them there was an especially memorable, single “Trojan War.” However, everything currently suggests that Homer should be taken seriously, that his story of a military conflict between Greeks and the inhabitants of Troy is based on a memory of historical events—whatever these may have been. If someone came up to me at the excavation one day and expressed his or her belief that the Trojan War did indeed happen here, my response as an archaeologist working at Troy would be: Why not?”

In writing this post I pulled evidence from three works:

The Trojan War: A Very Short Introduction by Eric Cline (highly recommended)

“Was There a Trojan War?” by Manfred Korfmann found at this link: http://archive.archaeology.org/0405/etc/troy.html

“Troia in Light of New Research” a lecture by Manfred Korfmann which can be found at this link: http://www.uni-tuebingen.de/troia/eng/fachliteratur.html

You can buy Judith’s novel at the following links:

September 3, 2014

Guest Post by Debra Bayani: The Supposed Daughters of an Earl

I’m pleased to be part of a blog tour for Debra Bayani, author of a new biography: Jasper Tudor: Godfather of the Tudor Dynasty! Jasper Tudor has always intrigued me, and I’m eager to learn more about him. Here’s Debra!

Very often I receive messages and comments on my posts from people, mostly women, saying they are descended from Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke and later Duke of Bedford, through his daughters Helen/Ellen or Joan. They claim to be his 17th great-great-grand daughter or his 18th great-grand niece, sometimes even a few times removed – something which would be lovely if only it were true. It is entirely understandable that someone would be pleased and proud to think themselves to be related to such an heroic person, but it does, however, surprise me that, when I try to explain that the chance of being an actual ‘relative’ of Jasper is very slight, people react as if I’m deliberately offending them or trying to undermine their castles in the air. I need hardly say that this is certainly not the case at all. I hope that the following explanation will make the position clear.

It is alleged that, sometime in the 1450s, Jasper had a love affair with a certain Welshwoman named Mevanvy ferch Daffydd from Gwynedd and by her had two illegitimate daughters, Helen or Ellen and Joan, both said to have been born in Snowdonia. Joan, supposed to have been born in 1453, is said to have married William ap Yevan (son of Yevan ap William and Margaret Kemoys) by whom she had twin sons called Morgan and John ap William(s) born in Lanishen, Wales, in 1479. It is believed that Joan herself died while giving birth, but Morgan, in 1499, married Thomas Cromwell’s sister Katherine Cromwell in Putney Church, Norwell, Nottinghamshire, and so became fourth-generation ancestor to Oliver Cromwell. Jasper’s alleged second daughter, Helen or Ellen, is said to have been born in 1459 and married, after 1485, to William Gardiner (son to Thomas Gardiner and Anna de la Grove), a cloth merchant who became a spearman for the Lancastrians at the Battle of Bosworth. As a blood relation of the winning side Sir William’s trade as a clothier was much enhanced by the custom of aristocratic and even royal buyers. Helen/Ellen and William Gardiner had at least one son, Stephen Gardiner, who became a well-known figure under the Tudor monarchy during Henry VIII’s reign, and four daughters. Lately it has been questioned whether or not this Stephen Gardiner was in fact their son and another individual, Thomas Gardiner, has also been suggested.

In spite of this, there is no actual proof whatsoever that Jasper’s relationship with Mevanvy ever took place. There is, of course, a possibility that she was his mistress until around the early 1460s; but there is no mention of any other children he had with her. In fact, there is no official or contemporary mention at all of his daughters – not even Jasper’s will refers to the girls or Mevanvy – and there is no evidence for their existence in any remaining contemporary source. The earliest known reference is in William Dugdale’s Baronage of England dating to 1676, but this gives only Ellen as Jasper’s illegitimate daughter and again does not mention Mevanvy. Dugdale simply reports Jasper as ‘leaving no other issue than one illegitimate Daughter, called Ellen, who became the Wife of William Gardner, Citizen of London’, a statement based on a book of a contemporary of Dugdale’s. I have been unsuccessful in finding out where this Mevanvy was first mentioned. There is, however, a novel by Betty King called The Lord Jasper, first published in the 1970s, where the relationship of Jasper and Mevanvy was given clear field (as well as that with Margaret Beaufort).

It appears probable that this relationship and Mevanvy were invented by a novelist trying to romanticise the life of the man who seems to have lived a life of service to others rather than indulging in his own pleasures.

Selected Sources:

William Dugdale, The Baronage of England, vol.3 (London, 1676)

Betty King, The Lord Jasper (Leicester: Ulverscroft, 2001)

Jasper Tudor, Godfather of the Tudor Dynasty is now available in colour and black & white editions on all the Amazon websites and Book Depository.

Click here for Book Depository

Debra Bayani is a researcher and writer, living in the Netherlands with her husband and children. She previously studied Fashion History and History of Art. She has been interested in history as far as she can remember with real passion for the Middle Ages and the Wars of the Roses, and has spend many years researching this period. Currently she is working on a visitor’s guide to places connected to the Wars of the Roses. Debra’s debut non-fiction book, the first biography on the subject, ‘Jasper Tudor, Godfather of the Tudor Dynasty’, was published in 2014.

Her website can be found at: www.thewarsoftherosescatalogue.com and she is the admin of the coordinating Facebook page The Wars of the Roses Catalogue and her author page on Facebook.

August 30, 2014

Thomas Grey, Marquis of Dorset, Elizabeth Woodville’s Oldest Son

This is a repost of a guest post I did last year for the excellent Lady Jane Grey Reference Guide. Speaking of guest posts, look for one here soon by Debra al-Bayani about one of my favorite Tudors, Jasper!

Stepson to the King

Elizabeth Woodville’s first husband was Sir John Grey, the son of Edward Grey, Lord Ferrers of Groby, and his wife, Elizabeth. Depending on which postmortem inquisition one believes, Thomas Grey was born around either 1451 or 1455, but the latter date seems more probable, as jointure arrangements were being made for Elizabeth Woodville in January 1455, suggesting that she had married only recently.

Thomas’s father was killed in 1461 at the second Battle of St. Albans, leaving Elizabeth with two sons, Thomas and Richard. As Lady Ferrers of Groby had remarried, young Thomas’s inheritance was in some jeopardy, a situation Elizabeth Woodville sought to remedy in 1464 by agreeing with William, Lord Hastings that Thomas would marry one of Hastings’ as-yet-unborn daughters or nieces. As it turned out, however, Hastings’ assistance proved unnecessary, for that same year, Elizabeth attracted the interest of a far more powerful protector: Edward IV himself. Young Thomas suddenly found himself the stepson of the King of England.

Soon after Elizabeth Woodville’s royal marriage, her unmarried sisters each were provided with nobly born husbands, and Thomas Grey joined in the marital sweepstakes as well. His bride was Anne Holland, the only child of Edward IV’s sister Anne, Duchess of Exeter, and her estranged husband Henry Holland, Duke of Exeter.. Young Anne, a child like Thomas, had been slated to marry George Neville, a nephew of the powerful Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, but Elizabeth Woodville preempted the Neville match by paying the Duchess of Exeter 4,000 marks for her daughter’s marriage. Thomas and Anne married in October 1466 at Greenwich. Unfortunately, the marriage was short-lived, as Anne Holland died by 1474.

According to the Tudor chronicler Edward Hall, in 1471, Thomas Grey got his first recorded taste of battle at Tewkesbury, when he along with William, Lord Hastings, led the rearguard. Hall also claims that Grey joined the Duke of Clarence, the Duke of Gloucester, and Hastings in murdering Henry VI’s seventeen-year-old son, Edward of Lancaster, after the battle. Earlier sources, however, suggest that Edward died either in the battle proper or the rout.

On August 14, 1471, Thomas was created Earl of Huntingdon. Before June 6, 1474, he married Cecily Bonville, the heiress to the Bonville and Harington estates. Cecily was also the stepdaughter of William, Lord Hastings, who sold Cecily’s marriage to Elizabeth Woodville for 2500 marks, a fee which was later satisfied when Edward IV cancelled a debt owed to him by Hastings. On April 18, 1475, Thomas was made a Knight of the Bath, as were his younger brother Richard Grey and his royal half brothers, Prince Edward and Richard, Duke of York. After dinner, Thomas was created Marquis of Dorset and dined in his robes. That same year, he took part in Edward IV’s anticlimactic expedition to France. In July 1476, Dorset participated in the ceremonial reburial of the king’s father. Throughout Edward’s reign, he served on royal commissions. Dorset became a Knight of the Garter in 1475 or early 1476.

In 1478, Dorset participated in the jousts following the marriage of his half-brother Richard, Duke of York. As Dorset made his entrance, his helmet was carried by Henry, Duke of Buckingham. Following Dorset were five coursers, their rich trappers “emramplished with A’s of gold curiously embroidered” and a void courser for the accomplishment of his arms. He had the unhappy duty in 1479 of attending the funeral of Edward IV’s youngest son, George. In 1480 he assisted at the christening of the youngest royal child, Bridget.

On September 16, 1480, Dorset was granted the wardship and marriage of the Duke of Clarence’s orphaned heir, Edward, Earl of Warwick. Although W. E. Hampton suggests that Dorset might have neglected his ward, thereby causing him to become feeble-minded, there is scant evidence that Warwick was feeble-minded and none at all that Dorset mistreated him. Equally unfounded is the allegation that Dorset locked up young Warwick in the Tower. Most likely Warwick lived on Dorset’s estates in the country. As Dorset had many daughters, Warwick was probably intended to marry one of them.

In 1482, Edward IV’s youngest brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, led an expedition into Scotland. Dorset served as one of his lieutenants, as did Elizabeth Woodville’s younger brother Edward. If there was any friction between Gloucester and these members of the Woodville family, it left no trace in the records.

Exile

The pivotal year of 1483 began on a high note for Dorset. Anthony Woodville, Earl Rivers, Dorset’s uncle, arranged in March 1483 for Dorset to take over his position as deputy constable of the Tower. It has been suggested that this was part of a scheme on the Woodvilles’ part to poison Edward IV and seize power, but this theory rests on rather shaky evidence. There seems to have been nothing secretive about Rivers’s and Dorset’s arrangements, which may have been simply been designed to augment the income of Dorset, who had a large family to support and to marry off. Dorset was indeed preoccupied at this time with arranging the marriage of his eldest son to Anne St. Leger, the daughter of Anne, Duchess of Exeter, by her second husband.

All these plans, of course, went for naught, for in April 1483, Edward IV died and was succeeded by his twelve-year-old son, Edward. At the time of the king’s death, three of the key players were absent: Edward V and his governor, Anthony Woodville, who were both at Ludlow Castle, and Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who was in the North. In their absence, the council debated the shape the minority government would take—without, according to Dominic Mancini, waiting for the arrival of Gloucester, who would surely have an opinion on the matter. Dorset is said to have brushed off his fellow councilors’ concerns with the contemptuous reply of, “We are so important, that even without the king’s uncle we can make and enforce these decisions.”

Dorset had an enemy on the king’s council: his stepfather-in-law, William, Lord Hastings. Mancini, an Italian who happened to be visiting England during the fateful spring and summer of 1483, claimed that Dorset and Hastings had a “deadly feud” based on the mistresses they had attempted to steal from each other. Hastings and Dorset’s uncle Anthony Woodville were also on bad terms. Hastings, therefore, hurried to make common cause with Gloucester against the Woodvilles. With the help of Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham, Gloucester seized Anthony Woodville and Dorset’s brother, Sir Richard Grey, as they were traveling with Edward V to London.

When Dorset and his mother heard the news, they tried to raise troops, according to Mancini, before Elizabeth fled into sanctuary. Dorset likely accompanied her there, although Gloucester himself believed that he was at large. Mancini also reported a rumor that Dorset, his mother, and his uncle Edward Woodville had made off with the royal treasury, but the evidence does not support the rumor. Gloucester was, however, seizing Woodville property, including that of Dorset: Simon Stallworth reported in June that “Where so ever can be found any goods of my lord Marquis is taken.” Elizabeth Shore, known to us as “Jane,” was arrested around this time, possibly in connection with Dorset, as she was alleged to be his mistress.

On June 13, Hastings attended a council meeting at the Tower, only to be seized and summarily executed on Gloucester’s orders. At about this time, Mancini reported, Gloucester learned that Dorset had left sanctuary, “and, supposing that he was hiding in the adjacent neighborhood, he surrounded with troops and dogs the already grown crops and the cultivated and woody places, and sought for him, after the manner of huntsmen, by a very close encirclement, but he was never found.” Soon afterward, Gloucester, having declared that Edward V, Richard, Duke of York, and their sisters were illegitimate, took the throne as Richard III. He first executed Anthony Woodville and Dorset’s brother Richard Grey.

As rumors began to circulate that the sons of Edward IV had been murdered, a rebellion against the new king broke out in the autumn of 1483 with the aim of putting an obscure exile, Henry Tudor, on the throne. Dorset emerged from hiding to join the rebellion. Richard III sent out a proclamation offering 1,000 marks in money or 100 marks in land for anyone who captured Dorset, whom he claimed “not fearing God, nor the peril of his soul, hath many maids, widows, and wives damnably and without shame devoured, deflowered, and defouled, holding the unshameful and mischievous woman called Shore’s Wife in adultery.”

The rebellion, including Dorset’s rising at Exeter, failed. Despite the price on his head, Dorset evaded capture and fled to Brittany, where he joined Henry Tudor in his exile. The Duke of Brittany granted Dorset and his men 400 livres a month.

In the spring of 1485, however, Dorset’s own mother, Elizabeth Woodville, who had agreed the previous year to release her daughters from sanctuary, sent a startling message to her son: she advised him to abandon Henry Tudor’s cause and return to Richard III’s England. Richard had executed Dorset’s uncle Anthony and his younger brother Richard; his royal half-brothers had disappeared, their fate still a mystery today. Dorset, therefore, had cause to be wary of this offer, sincere as it might have been. Nonetheless, “partly despairing for that cause of Earl Henry’s success, partly suborned by King Richard’s fair promises,” Dorset set off to England, to the dismay of his fellow exiles, who feared that he would reveal their secrets to King Richard. One fellow exile, Humphrey Cheney, tracked Dorset to Compiégne and urged him to abandon his plan to return home. Even though Dorset gave in to Cheney’s entreaties, his moment of weakness meant that he would never enjoy Henry Tudor’s trust again. When Henry invaded England later that year, he left Dorset behind as human collateral for money he had borrowed to finance his expedition.

Under Suspicion

The victorious Henry Tudor, now Henry VII, treated Dorset gingerly after the latter’s return to England. His attainder was reversed, but he was not summoned to Henry VII’s first Parliament, and he lost the grants and wardships he had acquired under Edward IV. He and his wife, however, assisted at the christening of Henry’s first child, Prince Arthur.

In 1487, though, Dorset found himself a prisoner in the Tower. A group of conspirators had latched upon a young boy, known as Lambert Simnel, whom they claimed was Edward, Earl of Warwick. The genuine Warwick, in fact, had been shut up in the Tower since the beginning of Henry’s reign, but Henry was taking no chances with Dorset, Warwick’s former guardian. As Francis Bacon wrote, “He sent the Earl of Oxford to meet [Dorset] and forthwith to carry him to the Tower; with a fair message nevertheless that he should bear that disgrace with patience, for that the King meant not his hurt, but only to preserve him from doing hurt either to the King’s service or to himself.” Even though the rebellion was soon put down, Dorset seems to have remained in the Tower until after the coronation of Henry’s queen, Dorset’s half-sister Elizabeth, in November 1487.

After his release, Dorset still remained under a cloud. On June 4, 1492, he was obliged to convey his lands to feoffees and to sign an indenture stating that if he committed treason or misprision of treason (concealment of treason), the feofees would hold the lands for the use of the king. He was also required to grant the king the wardship and marriage of his eldest son. A later indenture of 1496 was probably a less restrictive version of the 1492 arrangement.

On June 8, 1492, four days after Dorset entered into this indenture, his mother died at Bermondsey. Dorset and his wife both attended her funeral.

Last Years

Whether or not Henry’s suspicions of Dorset had been justified, Dorset behaved himself. He joined Henry VII on his expedition to France in the autumn of 1492 and helped suppress the Cornish insurrection in 1497. In 1495, he sat on the panel before which William Stanley was indicted for treason. Dorset continued to attend court: the king lost a pound to him in “playing at the butts” in 1495.

Dorset had a knack for spotting talent. Impressed by his three sons’ schoolmaster at Magdalen College at Oxford, Dorset invited the young man to spend Christmas with the family, then later presented him with the living of the Somerset rectory of Limington. It was not the last history would hear of Thomas Wolsey.

On September 20, 1501, Dorset died. In his will, dated August 30, 1501, he asked that he be buried at the collegiate church of Astley in Warwickshire. He requested prayers for the soul of his father, for his mother the queen, for Edward IV, for his wife (presumably his first wife, Anne Holland, as his second wife outlived him by many years), for his own soul, and for all Christian souls. Cecily, Marchioness of Dorset, who had borne her husband seven sons and eight daughters during their marriage, remarried but later requested burial beside Dorset at Astley. Dorset’s lands included Astley, Grafton, and Bradgate, the latter the manor most strongly associated with Lady Jane Grey.

Dorset may have also left an illegitimate daughter, Mary, referred to in the will of Elizabeth Neville, Lady Scrope of Masham, who gave “Mary, daughter in base unto Thomas Grey Marquess Dorset, my bed that the said Lord Marquess was wont to lie in, & all the parcel that belong thereto, & all the apparel of the same chamber.” While it is possible that the Thomas Grey referred to in the will, made in 1513-14, was Dorset’s son by the same name, the “was wont to lie in” language, harking back to bygone days, suggests that Dorset himself is the likelier candidate.

Conclusion

The Marquis of Dorset remains an elusive figure, whose willingness to abandon Henry’s cause to make his peace with Richard III has given him a perhaps exaggerated reputation for fickleness and disloyalty. He did, after all, have a family in England to tempt him back, as well as a bereaved mother. His sexual exploits, as described by Mancini and Richard III, also raise eyebrows, but there may well have been a propaganda element at work where the wilder claims are concerned. To his credit, Dorset seems to have borne his equivocal status during Henry VII’s reign with grace. Polydor Vergil, who had no obvious need to gild his reputation, called him “vir bonus et prudens.” One wonders what this early patron of Wolsey would have made of his learned great-granddaughter, Lady Jane.

July 10, 2014

Twelve Tips for Winning an Online History Argument

Let’s face it, history discussions on Facebook (and other social media) can be rough.

But there’s really no need to stress, because here are twelve handy lines for you to whip out whenever you’re on the verge of losing a historical discussion. Use any of the following, hit “send,” and your opponents, reduced to dejected silence, will gather up what’s left of their shredded dignity and slink off to FarmVille.

Well, it could have happened. We’ll never know.

You weren’t there, and neither was I.

It’s Tudor propaganda.

I’ve been reading about this period for 30 [40/50/60] years.

My parent/sibling/spouse/partner/child is a historian, I’ll have you know.

I know it’s from a novel, but there has to be some truth to it or the author wouldn’t have written it that way.

I saw it in a book. Look it up.

[Insert historical figure from 18th century or earlier] was my grandparent.

I was [insert any historical figure, provided he or she was reasonably attractive and very well known] in a previous life. I just sense what happened.

I’m entitled to my opinion.

I don’t have time to read that.

History is written by the victors.

N.B. : None of these lines need be deployed alone, but can be combined (and augmented with use of ALL CAPS and lots of exclamation points!!!!!).

Happy discussing!!!!!

July 4, 2014

The Will of Margaret Douglas, Countess of Lennox

As readers of this blog know (I was going to say “regular readers,” but this blog has been a bit, er, irregular over the past few months), I’m very fond of wills. When I was researching Margaret Douglas, Countess of Lennox, for a now-defunct project, I had her will transcribed, and it’s been sitting forlornly in my files ever since. So here it is! I’ve modernized the spelling and broken it into paragraphs for ease of reading.

Margaret died on March 9, 1578, having made her will on February 26, 1578. Note that the new year officially began on March 25, so Margaret gives the date of her will as 1577. She was buried at Westminster Abbey at the expense of Queen Elizabeth. Later, King James VI and I (the King of Scots mentioned by Margaret) erected a monument to his grandmother’s memory.

In the name of God Amen I Margaret Countess of Lennox widow late wife of Matthew Earl of Lennox Regent of Scotland deceased, being of good and perfect mind and remembrance and in good health of body (thanks be to Almighty god) the six and twentieth day of February in the year of our lord God a thousand five hundred seventy and seven [new style date: 1578] and in the twentieth year of the reign of our sovereign lady Elizabeth by the grace of God queen of England France and Ireland defender of the faith etc do make, ordain and declare this my present last will and testament in manner and form following

First I bequeath my soul unto Almighty God my savior and redeemer, And my body to be buried in the great church of Westminster in the monument, sepulcher or tomb, already bargained for, and appointed to be made and set up in the said church. Also I will that the body of my son Charles shall be removed from the church of Hackney and laid with mine both in one vault or tomb in the said church of Westminster / And I give appoint and bequeath for my burial and funerals to be bestowed and employed thereupon the sum of twelve hundred pounds alias one thousand two hundred pounds of lawful money of England to be made and furnished of my plate household stuff and movables to be sold therefore / And I will that forty pounds of the said twelve hundred pounds shall be given and distributed to the poor people at the day of my burial / And that there be one hundred gowns furnished and given to a hundred poor women at the said day of my burial to be paid for and furnished of the said sum of Twelve hundred pounds.

Also I give and bequeath to the king of Scots for a remembrance of me his Grandmother my new fielde [field? filled?] bed of black velvet embroidered with flowers of needle work with the furniture thereunto belonging as curtains, quilt, and bedstead, but not any other bedding there unto / And the same to be delivered to the said king within six months after my decease if God shall grant him then to be living.

Also I give and bequeath to Margaret Wilton my woman (if she be with me in service at the time of my death) the sum of fifty pounds of lawful money And to every other servant of mine (as well women as men) that at the time of my decease shall be in my service ordinary, one year’s wages according to the rate of their entertainment they then have of me yearly. Also I give and bequeath to old Mompesson my servant (if then at my death he shall be living) twenty pounds of lawful money / All and every which sums I will to be made raised paid and satisfied of my household stuff with in any my houses wheresoever to be sold therefore within one year next after my burial and Funerals performed as aforesaid / Also I give and bequeath to Thomas Fowler my servant for his good and faithful service done to me and mine many years past all and every my stock of sheep as well young as old of all sorts and kinds / And now in the use and custody of Lawrence Nessebett, Symonde Doddesworth and Rowland Fothergill and every or any of them within and upon my lordship of Settrington in the County of York being in number eight hundred at six score to the hundred / And where I owe unto the said Thomas Fowler my servant seven hundred threescore eighteen pounds and fifteen shillings of lawful money of England upon the determination of his last account made and cast up by my auditor at my audit held at Michaelmas last past which debt I acknowledge to be due and owing to him by me I will that the same sum of money as my due debt be paid and satisfied to the said Thomas Fowler of my goods, chattels, plate and jewels / Also I give and bequeath to the said Thomas Fowler all my clocks, watches, dials with their furnitures.

And I make ordain will constitute and appoint John Kaye of Hackney Esquire and the said Thomas Fowler my full and lawful executors / And I give and bequeath to the said John Kaye for his pains forty pounds to be made of my goods as aforesaid / And I will, ordain and provide my very good Lords William Lord Burghley Lord Treasurer of England, and Robert Earl of Leicester my overseers / And I give and bequeath to them for their pains viz to the said Lord Treasurer my Ring with four diamonds set square therein black enameled and to the said Earl of Leicester my chain of pomander beads netted over with gold / And my tablet with the picture of King Henry the eighth therein / All the rest of my jewels goods chattels movable and unmovable, my funerals and legacies performed and my due debts paid I give and bequeath to the Lady Arbell Daughter of my son Charles deceased / Provided always and I will that where the one of my said Executors Thomas Fowler hath for sundry and divers bargains made for me and to my use by my appointment, authority and request entered into sundry bonds and covenants of warranties in sundry sorts and kinds that by law he may be challenged and constrained to answer and make good the same he the said Thomas Fowler my said executors shall out of my said goods, chattels movables plate and jewels whatsoever be answered allowed satisfied recompensed and kept harmless from any loss recovery forfeiture actions suits demands whatsoever may be and shall be of and from him my said executor lawfully recovered and obtained by any person or persons at any time or times after my decease / And provided also and I will that the rest and portion of my jewels, goods or movables whatsoever shall fall out to be shall remain in the hands, custody and keeping of my said executor Thomas Fowler until the said Lady Arbell be married or come to the age of fourteen years, to be then safely delivered to her if God shall send her then and so long to be living.

In witness whereof, and that this is my lawful last will and testament made and determined advisedly by good deliberation, and upon good considerations / I the said Lady Margaret being in good and perfect health and memory have put here unto my hand and seal of arms, the day and year above expressed and specified / witnesses to the same these persons hereafter subscribing their names.

Memorandum that whereas this will was sealed up with a label and the seals of D. Huicke and D. Caldwall set unto or upon the same label the eleventh of March 1577 [1578] the said D. Huicke and D. Caldwell were present at the breaking up of the same label and did acknowledge the same to be sealed with their seals / And that the testament within written was before them and others whose names be endorsed, acknowledged by the within named Lady Margaret to be her last will and testament / In the presence of me William Drurye Doctor of the law and other witnesses underwritten Robert Huicke Richarde Caldwall, Robert Boys N. Paine, Robert Weldoms / Witnesses to this her grace’s last will and Testament are we whose names be underwritten Margery Will[ia]ms Robert ?Hewicke, Richarde Caldwall, John Wolpe, Lawrence Nessebett / Will[ia]m Mompesson

Translation of the probate

This testament was proved at London before master William Drurye, doctor of laws, commissary of the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, on the 27th day of the month of March in the year of the lord 1578 by the oath of Thomas Fowler, the executor, named in this will. To whom was committed the administration, etc, sworn, etc, well, etc, with John Key, the other executor, renouncing [the will].

May 28, 2014

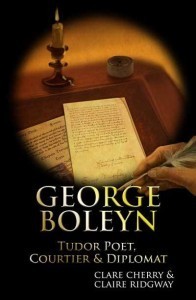

George Boleyn Virtual Book Tour, Day 4: A Guest Post and a Giveaway!

I’m delighted to be part of the George Boleyn Virtual Blog Tour for Clare Cherry and Claire Ridgway’s new biography of George Boleyn, a figure whose accomplishments and talents are too often overlooked, as we learn here. I’m also delighted to be able to offer a giveaway of one copy of their book! To be eligible, leave a comment here before June 5 (U.S. time), and I’ll pick a winner the following day.

And now, over to Clare and Claire!

George Boleyn: A single-minded and ruthless Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports

In June 1534, Henry VIII appointed George Boleyn as Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports and Constable of Dover Castle.

The Cinque Ports is a group of port towns on the southeast coast of England. The original five were Sandwich, Dover, Hythe, New Romney and Hastings, but Winchelsea and Rye were also added. The port towns were of strategic importance for the defence of the country from potential foreign invasion. As such, they were responsible for the fitting-out and manning of ships for the transport of the King’s army, and defence of the coast. In return, they received extensive immunities and liberties, which they guarded jealously. Every ambitious man in England wanted the distinction of being granted the position of Lord Warden, so much so that the post was held by princes of the realm such as Edward I, the Duke of Gloucester (later Richard III) and Henry VIII himself prior to becoming King. Ominously, the Duke of Buckingham had held the post prior to his execution in 1521 on trumped up charges of treason. In the sixteenth century, it was the most powerful appointment of the realm. The Lord Warden had “lieutenant’s powers of muster” and admiralty jurisdiction along the coast, and served as the Crown’s agent in the ports. His responsibilities included collecting taxes, arresting criminals and returning writs. He held court in St James’ Church, near Dover Castle, and the jurisdiction was similar to that of Chancery. The merging of the Constableship of Dover Castle with the office of Lord Warden meant that the Lord Warden also had a garrison at his disposal.

The appointment was made by the Crown, and the Lord Warden’s first loyalty was to the sovereign, who was often intolerant of any rival jurisdiction. This resulted in the Lord Wardens having conflicting loyalties, because they were also bound by their oath of office to maintain and defend the ports’ liberties. The ports looked to their Lord Wardens to be their protectors against external pressures, in particular those exerted by the Crown. This was not an easy balancing act for any Lord Warden, let alone one who was the King’s brother-in-law. George Boleyn’s position as Lord Warden meant that when he was not abroad on embassy, much of his time would have been spent in Dover. His influence is referred to in correspondence between England and Calais. The post was not a sinecure, and he was not merely a figurehead; he took a very active role. For example, in April 1535, two men, Robert Justyce and his son James, were ordered to make certain payments together with further penalties for other misbehaviour, including a verbal refusal to make payment to the complainants as ordered. On 8 May Sir Richard Dering wrote to Lord Lisle complaining that he was being blamed by the Justyce’s for the making of the order, when it was in fact “my Lord Warden’s own personal act and judgement, sitting in court, and sitting with him then there present Sir William Haute and Sir Edward Ryngeley, knights and divers other gentlemen”, whereby George “commanded them both to prison”. Dering goes on to say that George:

Not only at his departing from the Castle did straitly command me, but also by his several letters in like manner did command me that they both should satisfy the said parties complainants their demands adjudged and also pay the penalties and moreover be bound with sufficient sureties for their good abearing before they should depart out of prison.

Eventually, the two men paid the sums they were ordered to pay, less sums which the complainants relaxed, and were thereby released by Dering, even though they had not given the sureties George had ordered. Dering also discharged them from part of the penalties they had been ordered to pay.

The fact that the complainants themselves relaxed part of the judgement suggests that the amount awarded by the young Lord Warden had been excessive. Upon hearing the judgement, Robert Justyce had exclaimed that “he would rather be cut in two with a sword than pay the demands the complainants adjudged or pay the penalties” – hence the Lord Warden’s decision to command themto prison. Robert Justyce had been foolish enough to challenge the authority of George Boleyn in a court full of high-ranking officials, and such audacity could not be allowed. The fact that George sentenced both father and son to prison confirms our view of him as a young man capable of a single-minded ruthlessness, particularly when openly challenged. In this instance he went further. Not only did he verbally reiterate his orders to Dering, he also did so in several letters. This was not simply a question of making an example of the men. George was obviously furious, and he pursued the matter with a single-mindedness bordering on the vindictive. By the tone of Dering’s letter, and from his actions, he clearly thought the Lord Warden had over reacted. He wrote to Lisle, “Of my own zeal, good will, and contrary to the commandment of my said Lord Warden, I have… set them both at liberty”. However, he does express anxiety as to the “non-doing”, of the Lord Warden’s commandments.

In November 1534, there were signs of a rather fraught relationship between George Boleyn, as Lord Warden, and Thomas Cromwell. Cromwell had attempted to undermine the young Lord and the following letter shows George’s unrestrained indignation:

On Sunday last the mayor of Rye and others were with me at court, and I have taken such order and direction with them as I trust is right and just. I have commanded the mayor to return to Rye, and see the matter ordered according to the order I have taken in it before. He now advertises me that you have commanded him to attend you, and not obey this order. If you have been truly informed, or will command the mayor to declare you the order I have taken, I trust you will find no fault in it. Touching the last complaint put up to you by one of London, I never heard of it before; but when the mayor goes down he may cause the other party to appear before you at your pleasure.

Cromwell had countermanded one of George’s orders given as Lord Warden, and this was something the young Lord was not prepared to tolerate. The young man was not only angry, but also probably humiliated at being made to look as if he were subservient. The tone of the letter is quite obviously self-righteous indignation. Dangerously, he was not afraid to show his anger to the King’s chief minister, or to make no attempt to camouflage his displeasure.

For George Boleyn to have undertaken the position of Lord Warden would be today’s equivalent of appointing a 30 year-old with no legal experience as a leading High Court judge. The Boleyn self-assurance and self-confidence meant that the high responsibility was merely viewed as a challenge to be embraced. To be able to undertake the role with panache and competency would further endorse the perception held both by the court and the general public that the Boleyn brother was an intelligent and gifted young man in his own right, not one who had to rely on his sister for preferment.

George clearly embraced the role of Lord Warden. Examples of writs he issued and examples of his influence are contained in the state papers. The energy and efficiency required to fulfil the duties of Lord Warden, while still maintaining a political and ambassadorial role and a high court profile, confirm what a hardworking and remarkable young man George Boleyn was.

Notes and Sources

Fleming, Peter, Anthony Gross, and J. R. Lander. Regionalism and Revision: The Crown and Its Provinces in England, 1200-1650. Bloomsbury Academic, 1998., 124.

Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 7: 922 (16), 1478.

St Clare Byrne, Muriel, ed. The Lisle Letters. Vol. 2. University of Chicago Press, 1981., p180, p480–481.