Susan Higginbotham's Blog: History Refreshed by Susan HIgginbotham, page 13

March 6, 2013

Exciting Stuff!

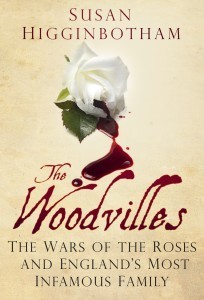

I wanted to mention several things that I’m excited about. First and foremost, here’s the cover design for my forthcoming nonfiction book about the Woodville family. Love it! The book will be released by the History Press in October of this year and is available for pre-order at Amazon UK.

Second, the Historical Novel Society is having its North American conference in St. Petersburg, Florida from June 21-23. If you haven’t signed up, now’s the time to do so! I’ll be part of a panel called “The Feisty Heroine Sold into Marriage Who Hates Bear-Baiting: Clichés in Historical Fiction and How to Avoid Them.” This is a great conference for authors, readers, and publishing professionals, so hope to see you there!

Third, my friend Sarah over at Sarah’s History Blog is celebrating Women’s History Month with a series of posts, some by Sarah and some by guests. There’s already some great posts up, and more are on the way! I’m doing a guest post at the end of the month–probably on Alice de la Pole, Duchess of Suffolk. Do stop by–it’s a great blog.

February 25, 2013

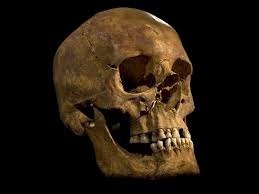

The Ten Stupidest Things I’ve Heard Since Richard III’s Remains Were Identified

Richard III’s skull. If it had eyes, they’d probably be rolling.

Since the remains found at Leicester were identified a few weeks ago, I’ve been compiling a list of the most dimwitted online comments related to this. I’m pleased to say that my list includes comments from people of differing nationalities, showing that stupidity is a truly global phenomenon.

Henry Tudor was jealous of Richard’s good looks.

The heresy of stating that the identification will not stifle debate about Richard’s character: “some people will doubt the Second Coming.”

The lead osteologist on the Leicester dig is a Tudor spy.

Richard III invented bail, abolished press censorship, and established the postal service.

Richard III’s reconstructed face shows that he was incapable of murdering his nephews.

Leicester cannot be trusted with Richard’s remains because the city “misplaced” them for 500 years.

A query as to whether those of Richard III’s “descendants” who wish to bury him in York might have recourse within the European Court of Human Rights.

A headline in The Daily Mail: “Richard III’s Ancestors Demand York Burial.”

Elizabeth II has not allowed DNA testing of the bones identified as belonging to the princes in the Tower because she is trying to hide something.

A query whether Richard’s DNA could be implanted inside someone and used to grow an exact replica of him.

February 16, 2013

Bridget of York: A Royal Nun

A while back, I wrote a blog post about the christening of Bridget, Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville’s youngest child. Here are a few more details about her life.

Bridget, as my post indicated, was born on November 10, 1480, and was christened the next day at Eltham. Her paternal grandmother, Cecily, Duchess of York, and her oldest sister, Elizabeth, were her godmothers at the baptismal font. Margaret, Lady Maltravers, a younger sister of Elizabeth Woodville, served as godmother at the confirmation. William Waynefleet, Bishop of Winchester, was the baby’s godfather. Bridget was most likely named after St. Bridget of Sweden. This may have been at the prompting of her grandmother Cecily, a deeply pious woman, but her parents might have chosen the name on their own: Edward IV had patronized the Brigittine house at Syon and had made use of the saint’s Revelations to support his claim to the throne.

The first mention of Bridget after her birth comes in 1483, when she is recorded as “being sick in the same wardrobe” and as receiving “two long pillows of fustian stuffed with down and two pillow beres of Holland cloth” for her use. The record is included with those related to the coronation of Richard III and Anne Neville, but Anne Sutton and Peter Hammond, following the interpretation of Sir Nicholas Harris Nicolas, point out that it probably dates to the period between Edward IV’s death on April 9 and Elizabeth Woodville’s flight into sanctuary on April 30-May 1. The Great Wardrobe, as they note, had its own site at Castle Baynard Ward and had been used to lodge members of the royal family in the past, including Margaret of York in 1468 and Edward IV himself in July 1480. Alternatively, perhaps Bridget, falling sick in sanctuary, was allowed to spend her illness in the greater comfort of the wardrobe.

Bridget certainly was with her mother and sisters in sanctuary, for on March 1, 1484, Elizabeth agreed with Richard III that her five daughters, Elizabeth, Cecily, Anne, Katherine, and Bridget, would leave their refuge. Richard swore that they would be “in surety of their lives” and that he would not imprison them “within the Tower of London or other prison”; he promised that he would “marry such of them as now being marriageable to gentlemen born.”

Richard III was killed at Bosworth before he could get around to arranging any match for Bridget, whose sister Elizabeth married the new king, Henry VII. Instead of making her own marriage, Bridget ended up entering the priory of Dartford, where she became a nun. It was unusual, but not unprecedented, for the daughter of an English king to take the veil: Edward I’s daughter Mary had taken the veil at Amesbury. Bridget’s own first cousin Anne de la Pole, whose parents were John de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk, and Elizabeth, a sister of Edward IV, took the veil at Syon and became its prioress. According to C.F.R. Palmer, Bridget entered Dartford in 1490, an event he associates with her mother’s withdrawal into Bermondsey Abbey, but in fact Elizabeth Woodville had gone to Bermondsey in 1487.

Why Bridget became a nun is unknown. It has been suggested that her veiling was part of Henry VII’s supposed attempt to suppress the line of the house of York, but as Henry allowed all of Bridget’s older sisters to marry, there would seem little point in preventing Bridget’s own marriage. Perhaps Bridget had been intended for the life of a nun from a young age, or perhaps she had some disability that ruled out marriage and children. Another possibility, of course, is that Bridget was a deeply pious girl who desired to take the veil.

A Dominican house located sixteen miles outside of London in Kent, Dartfort Priory is described by Paul Lee as one of the ten wealthiest and largest nunneries in England. During Bridget’s time at Dartford, the nunnery was under the charge of Elizabeth Cressner, who served as prioress from 1489 to 1536. The nunnery, the only house of Dominican nuns in England, observed the Rule of St. Augustine, which as Paul Lee notes “detailed a life of strict poverty, chastity, communal charity and obedience.” Lee also notes that “[e]nclosure of the nuns was strict, in principle, and there is no hint of scandal involving nuns leaving the monastic confines.” The priory did allow secular boarders, however, and both girls and boys were educated there.

In 1492, Bridget emerged from Dartford to attend the funeral of her mother; her older sisters Anne and Katherine participated in the services as well. Three years later, Bridget’s paternal grandmother, Cecily, Duchess of York, made her will. She left Bridget three books: a copy of the Legenda Aurea, a life of St Katherine of Sienna, and “the boke of St Matilde,” all of which, as Alison Spedding points out, figured in the “Orders and Rules” drawn up by the duchess for her own religious observances.

Elizabeth of York’s household accounts for 1502-03—the last year of the queen’s life—indicate that the queen sent money to her younger sister at Dartford; accounts for previous years do not survive. On July 6, 1502, a servant of the queen’s delivered 66 shillings and eight pence (3l 6s 8p) to the prioress. In September, the queen paid for the costs of another servant who had ridden from Windsor to Dartford “to my Lady Bridget.” Another payment of 66 shillings and eight pence was made to Bridget in March 1503.

Bridget did not live long enough to see the dissolution of Dartford. According to John Weever in Ancient Funeral Monuments, Bridget died around 1517 and was buried at Dartford: “She took the habit of religion when she was young and so spent her life in contemplation unto the day of her death.”

One question remains: did Bridget bear an illegitimate daughter, known as Agnes of Eltham, as claimed on some Internet sites? When this assertion (which has since been removed) appeared in the Wikipedia entries for Bridget and Agnes, I checked the two sources named and found that neither even mentioned Bridget or Agnes, much less substantiated the Wikipedia editor’s allegations. Nor do Elizabeth of York’s published privy purse expenses show any payments to Agnes of Eltham, despite claims to the contrary. Given these circumstances, it seems most likely that the allegations about Bridget arose from someone’s attempt to claim a fraudulent descent from Edward IV–at the cost of the reputation of a royal nun.

Sources:

C.A.J. Armstrong, “The Piety of Cecily, Duchess of York,” in his England, France and Burgundy in the Fifteenth Century (1983) (reprint of a 1942 article).

Mary Anne Everett Green, “Bridget, Seventh Daughter of Edward IV,” in her Lives of the Princesses of England, vol. 4.

Paul Lee, Nunneries, Learning and Spirituality in Late Medieval English Society: the Dominican Priory of Dartford (2001).

Sir Nicholas Harris Nicolas, Privy Purse Expenses of Elizabeth of York: Wardrobe Accounts of Edward the Fourth: With a Memoir of Elizabeth of York, and Notes (1830).

C.F.R. Palmer, “History of the Priory of Dartford, in Kent.” Archaeological Journal, vol. 36 (1879).

Pauline Routh, “Princess Bridget.” The Ricardian (June 1975).

Alison J. Spedding, “‘At the King’s Pleasure’: The Testament of Cecily Neville.” Midland History (Autumn 2010).

Anne F. Sutton and P. W. Hammond, The Coronation of Richard III: The Extant Documents (1983).

Anne F. Sutton and Livia Visser-Fuchs with R. A. Griffiths, The Royal Funerals of the House of York at Windsor (2005).

February 10, 2013

Richard III, the Advocate of a Free Press?

Hyde Park Speakers’ Corner. Richard III didn’t invent this either.

As my Facebook friends know, in the wake of the positive identification of the remains at Leicester as being Richard III’s (a wonderful find, by the way), I’ve indulged in a Girl-Scout-cookie eating game each time someone falsely claims that Richard III invented bail. That’s been a lot of cookies, folks!

A few days ago, however, I was floored to see an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal by historian Andrew Roberts, who claims, “here is a monarch who abolished press censorship, invented the right to bail for people awaiting trial . . .”

Abolished press censorship?

Richard III owned a variety of books and seems to have actually read them, instead of having them just for show. When his only Parliament passed “anti-alien” legislation placing restrictions on the commercial activities of aliens within England, those aliens involved in importing, selling, producing, or printing books were specifically exempted. We do not know whether this exemption was added at the initiative of the king himself or whether others advocated for it. What we do know is that it seems to have thoroughly confused Roberts, who wrote in another piece, this time for The Daily Mail, “[h]e also lifted restrictions on books and printing presses — effectively abolishing press censorship some 500 years before Lord Leveson tried to reintroduce it.” In fact, there had been no restrictions on books and printing presses to lift; the exemption from the anti-alien legislation simply maintained the status quo and allowed the affected readers—mainly scholars, clergy, and other learned men who needed material that had not been translated into English—to continue to obtain books from abroad and from aliens working inside England. The legislation had nothing to do with censorship, or the lack thereof.

Far from abolishing censorship, Richard III, as his crown was threatened from forces within and without England, showed himself on several occasions to be concerned with keeping his subjects from speaking their minds too freely. Forced in March 1485 to deny poisoning his queen in order to marry his niece, he proclaimed, “And what person that from henceforth tell or report any of this aforesaid untrue surmised talking, that the said person therefore be had to prison unto the actor be brought forth of whom the said person heard the said untrue surmised tale &c.”

A month later, Richard in a proclamation to the city of York noted that there were “divers seditious and evil disposed persons” who were “sow[ing] seed of noise and disclaindre [slander] against our person, and against many of the lords and estates of our land to abuse the multitude of our subjects and avert their minds from us if they could by any means attain to that their mischievous intent and purpose; some by setting up of bills, some by messages and sending forth of false and abominable language and lies; some by bold and presumptuous open speech and communication one with other.” He ordered that if someone “find any person speaking of us, or any other lord or estate of this our land otherwise than is according to honor, truth, and the peace and rightfulness of this our realm, or telling of tales and tidings whereby the people might be stirred to commotions and unlawful assemblies, or any strife and debate arise between lord and lord, or us and any of the lords and estates of this our land, they take and arrest the same person unto the time he have he brought forth him or them of whom he understood that that is spoken and so proceeding from one to other unto the time the furnisher, actor and maker of the said seditious speech and language be taken and punished according to his deserts, and that whoever first find any seditious bill set up in any place he take it down and without reading or showing the same to any other person bearing it forthwith unto us or some of the lords or other of our council.”

The most famous seditious writing of Richard III’s reign, of course, was William Collingbourne’s famous ditty:

The cat, the rat, and Lovell our dog

Rule all England under a hog.

The “cat, rat, and dog”’ were William Catesby, Richard Ratcliffe, and Francis, Viscount Lovell; the “hog” referred to Richard’s emblem of the white boar. Collingbourne was arrested in the autumn of 1484. While his most serious offense was writing to Henry Tudor and urging him to invade, he was also accused of “devising certain bills and writing in rhyme, to the end that the same being published might stir the people to a commotion against the king.” Around December, he was hanged, drawn, and quartered—not a great day for freedom of speech.

None of this, of course, should be taken to mean that other medieval English kings were less harsh than Richard in this respect. Henry VI and Edward IV similarly prosecuted defendants for speaking against the government. But Roberts’ notion that Richard was an early advocate for free speech is, to put it impolitely, sheer tripe.

Sources:

J. G. Bellamy, The Law of Treason in England in the Later Middle Ages

P. W. Hammond and Anne F. Sutton, Richard III: The Road to Bosworth Field

Anne F. Sutton and Livia Visser-Fuchs, Richard III’s Books

February 3, 2013

Leicester Dig Countdown Day 1!

February 1, 2013

Leicester Dig Countdown Day 2!

January 31, 2013

Leicester Dig Countdown Day 3!

January 30, 2013

Leicester Dig Countdown Day 4!

January 29, 2013

Leicester Remains Countdown Day 5!

January 28, 2013

Leicester Dig Countdown: Day 6

Officially, I’m still on hiatus, but as you probably know, the identity of the remains found at Leicester will be revealed on February 4. Therefore, since I’m doing a countdown on Facebook, I thought I’d do it here as well.