Susan Higginbotham's Blog: History Refreshed by Susan HIgginbotham, page 16

August 13, 2012

The Children Who Predeceased Edward IV

When Edward IV died in April 1483, he was survived by two sons and five daughters. His eldest daughter, Elizabeth, would become Henry VII’s queen, his sons would disappear during Richard III’s reign, his daughters Cecily, Anne, and Katherine would marry, and his youngest daughter, Bridget, would become a nun. But what of the often-forgotten children–three of them–who died before their father?

Mary

The first of these children, Mary, was Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville’s second daughter, who was born at Windsor Castle in August 1467. She was christened on 12 August 1467, a couple months after the famous tournament between Anthony Woodville and the Bastard of Burgundy at Smithfield. Cardinal Bourchier, the Archbishop of Canterbury, was her godfather; her godmothers are not recorded, but perhaps Elizabeth’s younger sister Mary served as one of them, and gave the infant her name. A year later, in October 1468, Edward IV granted the queen an allowance of 400 pounds per year for the expenses of her two daughters, Elizabeth and Mary. Mary’s governess during her early years was Margaret, Lady Berners, who served the princess until Lady Berners’ death in 1475.

Edward IV, preparing for what would be an anticlimatic expedition to France in 1475, drew up his will. Like her sister Elizabeth, Mary was to have a marriage portion of ten thousand marks if she married in accordance with the wishes of her mother and the Prince of Wales. If she disparaged herself, her ten thousand marks would go toward her father’s debts. Edward IV did not intend his daughters to make a runaway match as he had.

Instead of making war on the French king, Louis XI, Edward IV ended up entering into a peace treaty with him. As part of the arrangements, Elizabeth of York was promised to Charles, the Dauphin of France. In the event that Elizabeth died before the marriage took place, Mary was to take her place as the Dauphin’s promised bride.

In July 1476, Edward IV reburied his father, Richard, Duke of York, who had been killed at the Battle of Wakefield on 30 December 1460. The reburial took place at Fotheringhay. Among those making offerings at the requiem mass were “the queen and her two daughters,” presumably her first two daughters, Elizabeth and Mary, who was almost nine at the time.

The next ceremony Mary was called upon in which to participate was probably more to the young girl’s taste than the burial of the grandfather she had never known. In January 1478, Mary’s four-year-old brother Richard, Duke of York, married an older woman, the five-year-old Anne Mowbray. As the little bride entered the chapel, the king, the queen, and their daughters Elizabeth, Mary, and Cecily waited for her under a canopy of cloth of gold.

In 1481, Mary, apparently no longer needed as a stand-in for her older sister’s engagement, was proposed as a bride for Frederick I of Denmark. Sadly, instead of becoming queen of Denmark, Mary died in May 1482 at Greenwich–eleven months before her father.

Mary’s burial at Windsor, also her birthplace, took place on 27-28 May 1482. Among the ladies present were Jane, Lady Grey of Ruthyn (Elizabeth Woodville’s sister), the widow of Sir Anthony Grey of Ruthyn; Joan, Lady Strange, a niece of Elizabeth Woodville who was married to George Stanley; and Katherine Grey, probably the daughter of Jane, Lady Grey. The chief mourner is not identified but may have been Jane, Lady Grey, the first woman named by the herald who recorded the funeral ceremonies.

Mary was buried alongside her little brother George. Her grave was excavated in 1810.

Margaret

Conceived several months after her father recovered his throne in 1471, poor little Margaret was born at Windsor on 10 April 1472 and died on 11 December 1472. She was buried at Westminster Abbey before St. Edward’s shrine. According to Mary Ann Everett Green, her Latin tomb inscription, translated into English, reads: “Nobility and beauty, grace and tender youth are all hidden here in this chest of death. That thou mayest know the race, name, sex and time of death, the margin of the tomb will manifest all to thee.”

George

Ralph Griffiths believes that George, Edward IV’s little-known third son, was born during 1477. He could have been named after Edward IV’s younger brother George, Duke of Clarence, though any such tribute to Clarence would have taken place before George’s arrest in June 1477. Griffiths also suggests that George might have been named for Saint George, prompted by Edward IV’s rebuilding of St. George’s Chapel at Windsor.

Edward IV named George as his lieutenant of Ireland on 6 July 1478 and appointed Henry, Lord Grey of Codnor as his deputy. Young George never got a look at the emerald isle. In March 1479 he died, probably a victim of the plague or another epidemic disease. Griffiths believes that the boy was staying at Sheen at the time of his death.

George’s half-brother by the queen’s first marriage, Thomas, Marquess of Dorset, attended George’s funeral at Windsor, as did his uncle, Anthony, Earl Rivers; John, Lord Strange, the husband of Elizabeth’s sister Jacquetta; John Blunt, Lord Mountjoy; Richard Hastings, Lord Welles; and Lord Ferrers of Chartley. By custom, Edward IV was not publicly present at his son’s funeral, although it is possible that he observed the proceedings from an enclosed space. He was issued a robe of blue, however, a color worn by Margaret of Anjou and Elizabeth of York when their mothers had died.

Sources:

James Gairdner, ed., The Paston Letters.

Mary Anne Everett Green, Lives of the Princesses of England

William Nichol, Illustrations of Ancient State and Chivalry

Cora Scofield, The Life and Reign of Edward the Fourth

Anne Sutton and Livia Visser-Fuchs with R. A. Griffiths, The Royal Funerals at the House of York at Windsor

Anne Sutton and Livia Visser-Fuchs with P. W. Hammond, The Reburial of Richard, Duke of York 21-30 July 1476

July 25, 2012

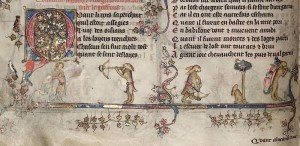

A Woodville Goes Book Shopping: The Romance of Alexander

I’ve been busy this week working on my nonfiction book about the Woodville family (perhaps you might have noticed a Woodville tinge to my posts here and on Facebook lately?). Anyway, I thought you’d enjoy seeing some images (available on Wikicommons) from the Romance of Alexander, Bodleian Library MS. Bodl. 264.

The book is a life of Alexander the Great in French verse. According to the Bodleian Library (where the entire manuscript can be viewed online), it was made by the Flemish illuminator Jehan de Grise and his workshop in 1338-44, with two sections added in England around 1400.

The Woodville connection of this lovely manuscript is that it was purchased by Elizabeth Woodville’s father, Richard Woodville, Lord Rivers. Near the back of the manuscript, Lord Rivers wrote, “This book belongs to Lord Richard de Wydeville, Lord Rivers, one of the companions of the very noble order of the Garter, and this Lord bought this book in the year of grace of 1466, the first day of the year, in London, and the fifth year of the coronation of the very victorious King Edward, the fourth of this name, and the second of the coronation of the very virtuous Queen Elizabeth, the day after Saint Maure’s Day.” Interestingly, the inscription, which appears on folio 274, is in French; the translation here is from Arlene Okerlund’s biography of Elizabeth Woodville, Elizabeth: England’s Slandered Queen.

With images like those below, Lord Rivers’ book must have afforded him hours of pleasure.

Folio 59r

Folio 81v

More smirking, armed hares

Folio 101v

July 12, 2012

When Was Elizabeth Woodville Born?

Nearly every biography of Elizabeth Woodville gives her birth date as being some time in 1437, the same year her parents, Jacquetta, Duchess of Bedford and her husband Sir Richard Woodville, were pardoned for their secret marriage. But where does the 1437 birthdate come from? From only one source–this portrait.

The portrait in question is labeled “1463″ (or at least, that’s the date I’m told it says; I can’t read it) and gives Elizabeth’s age as twenty-six (again, I can’t make it out myself)–hence the 1437 birth year. In a 1934 article in Burlington Magazine entitled, “The Early English School of Portraiture,” John Shaw suggested that it was done by John Stratford, who on July 8, 1461 was appointed as “the king’s painter.” Shaw described the veil in the portrait as a “widow’s veil” and suggested that the likeness was painted before Edward IV’s marriage to Elizabeth.

Based on this evidence, Elizabeth’s early biographer David MacGibbon wrote confidently, “All remaining doubts regarding the date of Elizabeth’s birth can now be said to have been finally dispelled by the inscription on the panel portrait of Elizabeth in the possession of Dr. W. A. Shaw of the Record Office. On this portrait, painted in 1463, her age is given as 26. This would make the year of her birth 1437.” More recently, David Baldwin in his biography of Elizabeth wrote, “Her date of birth is unknown, but a portrait dated 1463 indicates that she was then twenty-six.”

The label on the portrait is problematic, however. First, it is likely not contemporary. A label made in 1463 would surely identify Elizabeth as “Dame Elizabeth Grey,” her married name at the time, not as “Elizabeth Woodville.” Nor would it use the spelling “Woodville,” which is a modern spelling. A label made in 1464, after Elizabeth became queen, would likely say simply “Elizabeth” or “Elizabeth queen to Edward IV” or something of the sort.

Moreover, it is doubtful that the portrait dates from 1463. While John Stratford was indeed made the king’s painter in 1461, it is highly unlikely he would have been sent to take Lady Elizabeth Grey’s portrait in 1463. By all accounts, Edward IV’s marriage to Elizabeth was a secret match that took all of the country by surprise. This is hardly consistent with a scenario of Edward IV commissioning a portrait of Elizabeth the year before he married her. Moreover, in 1463 Elizabeth was in straitened circumstances after the death of her first husband, Sir John Grey, at the second battle of St. Albans in 1461. She was having difficulty recovering her dower and her sons’ inheritance; the following year, she would enlist William, Lord Hastings, in bringing her plight to the attention of the king. If she was on such terms with Edward IV in 1463 that he was having her portrait painted, she would have had no need of Hastings’ help in 1464.

The other possibility is that Edward IV had nothing to do with commissioning the portrait. But Elizabeth’s struggles over her dower indicate that she was not in a financial position to have her portrait taken in 1463. Nor were barons’ daughters in the habit of commissioning such portraits in the 1460′s, at least in England.

What about the “widow’s veil”? I am not an expert in medieval fashion by any means, but I see nothing in Elizabeth’s transparent veil to suggest that it was a mark of widowhood. Notably, Elizabeth is not wearing a barbe, the neck covering usually associated with medieval widow’s wear.

The most likely scenario, then, is that the portrait was made after Elizabeth became queen and that whoever labeled it, long after it was painted, was confused about when Elizabeth became queen. Whether Elizabeth was actually twenty-six when she sat for it is anyone’s guess.

So when was Elizabeth born? Even if the 1563 date on the portrait is discounted, it’s not impossible that she was born in 1537. According to an inquisition post mortem, Thomas Grey, Elizabeth’s oldest child, was born around 1455. Her youngest child, Bridget, was born on November 10, 1480. If Elizabeth was born in 1537, she would have been around 18 at the time of Thomas’s birth and 43 at the time of Bridget’s birth. Both dates are consistent with a 1437 year of birth. While 43 might seem a tad old for childbearing, Elizabeth’s own mother, Jacquetta, was recorded as being around seventeen at the time of her marriage to the Duke of Bedford in 1433, putting her birthdate at around 1416; her youngest child, Katherine, was born around 1458. Thus, she would have been about 42 when her childbearing ceased.

One source (albeit not strictly contemporary) suggests a later date of birth for Elizabeth, however. The following handwritten note by Robert Glover, Somerset Herald, on a late-fifteenth-century visitation (Visitations of the North, part 3, p. 57), which Brad Verity kindly called my attention to several years ago, may indicate the birth order of the Woodville children:

Richard Erie Ryvers and Jaquett Duchesse of Bedford hath yssue Anthony Erie Ryvers, Richard, Elizabeth first wedded to Sir John Grey, after to Kinge Edward the fourth, Lowys, Richard Erie of Riueres, Sir John Wodeuille Knight, Iaquette lady Straunge of Knokyn, Anne first maryed to the Lord Bourchier sonne and heire to the Erie of Essex, after to the Erie of Kent, Mary wyf to William Erie of Huntingdon, John Woodville, Lyonell Bisshop of Sarum, Margaret Lady Maltravers, Jane Lady Grey of Ruthin, Sir Edward Woodville, Katherine Duchesse of Buckingham

Anthony, the first child named in Glover’s list, was listed in his mother’s 1472 postmortem inquisition as being “of the age of thirty years and more,” which would put his birth date at around 1442, but the “and more” leaves plenty of hedge room and leaves open the possibility that he was born earlier than 1442. It is entirely possible, then, that he, not Elizabeth, was the oldest child. Unless new records surface, we’ll probably never know–but there are good reasons to doubt the inscription on the portrait as a source.

July 4, 2012

Reading to Grandmother

Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford

A while back when doing research on the Seymour family, I came across what I found was a rather amusing letter from Robert Tutt to Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford (the one who secretly married Katherine Grey). The ill-fated marriage and Katherine’s early death left the earl with two sons, Edward Seymour (Lord Beauchamp) and Thomas Seymour. In 1582, they were living with their paternal grandmother, Anne Seymour, Duchess of Somerset, at Hanworth.

The letter is dated June 10, 1582. Edward, born in the Tower of London on September 24, 1561, was a few months short of his twenty-first birthday when the letter was written; his younger brother Thomas, born in the Tower on February 10, 1563, was nineteen.

10 June, 1582. My humble dutie unto your honour remembered. It may please the same to be advertised that Her Grace remayneth still troubled with the cough which with her age maketh her feble and weak. Her Grace will not desire your [Lordship] retorne, but yet I know, willing enough to see your L. here; neyther request a Buck, but will take more [in] thankfull part one Buck voluntarily sent, especially at thys tyme of the yere, than a leash hereafter. And although your {Lordship] dothe conceyve, that it is no meat for Her Grace, being as she is, yet to have it in her house and to pleasure her neighbours and friends with venison at this tyme of the yere, it is no small pleasure. Those pinates whereof your [Lordship] maketh mention, Her Grace receyveth to ripen the flewme. Touching my Lord Beauchamp and Mr. Thomas, they continue for their dispositions after one sort. They have read my fellow Smith’s last letters in Latin, to Her Grace; and afterwards put the same into English to Her Grace, as your [Lordship] willed. With my L. Beauchamp Her Grace had speciall speeches, to what effect I know not, but without all doubt for his great good if he have a prepared mynde to follow grayve and sound counsels. Her Grace made him fetch his booke, entituled, ‘Regula Vitae,’ & out of the same to read the Chapiters ‘De veritate et mendaciis.’ Your L. shall do well in wonted manner to acknowledge her Grace’s great care of them and their well doing.

Now if your L. hath any meaning that Her Grace shall visit Totnam this summer, then is it necessaries your honour acquaint my fellow Ludloe with your L. determination therin: that all necessaries may be thought upon and provyded in tyme.

I rather like this business about the buck; it’s nice to know that the old duchess (who was in her seventies) still enjoyed having guests over to sup on venison. (The buck, however, might have another point of view altogether.)

The “Smith” referred to was probably Robert Smith, the sons’ tutor. Since the young men were reading Smith’s letters in Latin to the duchess, does this mean she understood Latin, or was she just an uncomprehending audience? The duchess and her husband had given their daughters an excellent humanist education, so it wouldn’t be surprising if at some point the duchess had learned Latin herself.

I have tried in vain to locate the Regula Vitae that young Lord Beauchamp was sent to read. I am convinced that I found it Google Books at one point, but I could be mistaken.

Finally, what, you may wonder, had Lord Beauchamp done to merit these “special speeches” from his grandmother? The speeches almost certainly involved his romantic life, for in 1581, Lord Beauchamp had fallen in love with a young lady named Honora Rogers, a kinswoman who had been in the duchess’s household. Although the Earl of Hertford was carrying on his own love affair at the time, with Frances Howard, one of the queen’s ladies, he was remarkably unsympathetic toward his son’s romance, especially when it transpired that Lord Beauchamp had married Honora. Hertford nicknamed Honora “Onus Blous” and directed an investigation of the couple’s courtship that would have done Thomas Cromwell proud. No Seymour servant or family member escaped interrogation, not even on Christmas day. Hertford also busied himself with jotting down memoranda of the young lady’s misdeeds, such as “when she was 15 or 16 years old in Barrowes she would pin up eggs in her smock so that her mistress should not find them.” It would be only after several years of family drama, in which the queen eventually intervened, that Lord Beauchamp and his wife were allowed to cohabit. Even the hapless Robert Smith was enlisted to write a letter to Beauchamp (in Latin, of course) urging him to follow his father’s wishes.

The duchess herself (who had sent for her grandsons in December 1581 “to profit their learning and virtuous exercises and to learn the truth from them of this last brabble”) called the hapless Honora a “baggage,” a fine word that in this usage really needs to make a reappearance. Eventually, however, she was reconciled with her grandson and his wife, for she remembered both in her will and left Honora “ a booke of gould kept in a grene purse, and a payer of bracelets without stones.” Hopefully, the book wasn’t Regula Vitae.

Sources:

Marjorie Blatcher, ed., Report on the Manuscripts of the Most Honourable the Marquess of Bath Preserved at Longleat, Vol. IV, Seymour Papers 1532-1686. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1968.

Rev. Canon J. E. Jackson, “Wulfhall and the Seymours,” Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine, 15 (1875). (Note: As Blatcher points out, Jackson misidentifies “Her Grace” in the letter quoted above as Elizabeth I.)

June 30, 2012

Here’s Margaret Beaufort!

Per a special request of a couple of my Goodreads friends, here’s Margaret Beaufort! She thought posing for Cosmopolitan was a little frivolous, but I convinced her that the articles were worthy of her august presence.

June 29, 2012

Margaret of Anjou on Cosmo

I put this on Facebook a couple of days ago, but for those of you who aren’t there, here’s Margaret of Anjou!

By the way, I’m finally winding down my blog tour. (You can find links to all of my stops on the bar on top of this page.) Now that things are relatively quiet again, I can do some more substantive posts for this blog, hopefully!

June 26, 2012

Even Jane Grey’s on Cosmopolitan!

I wanted to find a teen magazine for Jane, but all of the cover generators I found looked a little sketchy, so I stuck with the tried and true.

Karen over at A Neville Feast has some Cosmo girls of her own. A few more of my Facebook friends have done them as well, so if you’re over there, keep an eye out!

Cosmo Girl Isabella Pays a Visit! (And Two More Queens)

It’s been a long time since Isabella, Edward II’s queen, has paid a visit to this blog. In the early days, she used to stop by all of the time! Anyway, I was sure that a fashionable French lady like Isabella wouldn’t miss the chance to be on Cosmopolitan, and here she is!

And here, at last, are Wives One and Four:

June 24, 2012

The Cosmo Woodville Girl

June 23, 2012

More Tudor Cosmo Girls!

(I’ll try to add the other two wives soon, unless someone beats me to it! I know this may not be Katherine Howard’s portrait, but the other alternative didn’t work well with the cover generator.)