Susan Higginbotham's Blog: History Refreshed by Susan HIgginbotham, page 20

December 21, 2011

Christmas at Tilty: 1549

In November and December 1549, the Marquess and Marchioness of Dorset, Henry and Frances Grey, were on the move. On November 24, 1549, ten gentleman came from London to escort Frances and her three daughters, Jane, Katherine, and Mary, to visit the Lady Mary (that is, the future Mary I). The ladies broke their journey at Tilty, the Essex home of George Medley, Henry Grey's older half-brother. After breakfast on November 26, they journeyed on to visit Mary, perhaps at Beaulieu. Was this, perhaps, the occasion on which Jane is said to have refused Mary's gift of an elaborate gown, or on which she made a sarcastic comment when one of Mary's ladies genuflected before the Host?

After visiting Mary, Frances and her daughters seem to have gone to London, where they would have learned that Henry Grey, thanks to the downfall of Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, had been admitted to the king's privy council. Catherine and Mary headed back to Tilty, where they had cousins, on December 2. On December 16, Henry, Frances, and Jane went from London to Tilty, along with John Grey, Henry's younger brother. (Henry Grey seems to have been close to his brothers: George Medley, John Grey, and Thomas Grey all were involved in Wyatt's rebellion with Henry in 1554, and Thomas Grey was to die upon the scaffold a few weeks after Henry did.)

On Christmas Day of 1549, the Greys were still at Tilty, where "divers of the country" dined. Five players and a boy came, along with the Lord of Oxford's players. Perhaps Henry Grey also brought his dancing horse and his bear to the Christmas festivities, which lasted until January 9, 1550.

Later in January, the family went to Walden to visit Henry Grey's widowed sister, Elizabeth Audley. Lady Audley returned to Tilty with the Grey family. Later, she and her niece Catherine Grey went back to Walden, but they later joined the rest of the group at Tilty again. At last, on January 31, 1550, a gentleman from the Lady Mary came to dine at Tilty.

All this proves several things: (1) Contrary to some accounts, the supposedly hunchbacked Mary Grey wasn't hidden away by her family, but was brought along on visits. (2) Despite the prevailing notion that the Dorsets were an unloving family, they seem to have enjoyed family get-togethers. (3) George Medley must have been quite the host. One wonders what the poor man's bank account looked like on February 1.

All this might sound as if the Greys were enjoying a jolly English Christmas season, but the Greys' detractors have managed to give this visit a sinister cast. By moving the Tilty festivities to 1551-52 instead of the actual date of 1549-50, and by noting a comment in a letter dated February 8, 1552, that Jane Grey had just "recovered from a severe and dangerous illness," they arrive at the conclusion that all this traveling made poor little Jane gravely ill. As Agnes Strickland mournfully put it in her Lives of the Tudor Princesses, "The equestrian journeys which Lady Jane was forced to perform with her family in the winter of 1551 were fatiguing enough to have injured the health of a strong man. . . . All these migrations, for a delicate girl of fifteen, had the natural effect of making her very ill."

It is hard to out-Strickland Strickland, but Mary Luke in her so-called biography of Jane, The Nine Days Queen, gamely does just that. After a lengthy, and entirely fictitious, interlude where Katherine Brandon, Duchess of Suffolk, and Jane enjoy long, woman-to-woman talks in the country, Luke treats us to this: "It was at the end of one such tiring and cold journey that Jane, feverish and weak–and uneasily aware that she was inconveniencing her parents–took to her bed. She was now almost fifteen and not constitutionally strong. . . . It all had an effect, and, as her mother had done months before, Jane now became seriously ill. Mrs. Ellen and Mrs. Tylney spent hours at her bedside; her parents and sisters remained absent for fear of contamination."

Aside from the misdating of the the Tilty visit, this short passage is remarkable for its errors and inventions. First, all we know about Jane's early 1552 illness is that it was considered severe and dangerous; we have no idea what Jane's thoughts were at the time, nor do we know that her parents avoided her bedside or that her ladies spent hours there. Second, Frances fell ill months after Jane (in August 1552), not months before her. Third, there's no evidence that Jane was "not constitutionally strong."

All this goes to show that if one is determined to make one historical figure a martyr and others villains, all one has to do is confuse a couple of dates and turn a busy round of seasonal visits into a death march.

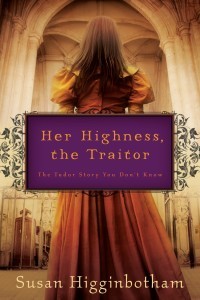

But on a cheerier note, Happy Holidays! I'll try to blog at least once more before the year ends, but in case I don't, or in case you're away from your computer, here's to a great 2012 for all of us. Look for Her Highness, the Traitor in June. Incidentally, there's a scene in it set at Tilty, where Frances makes a fool of herself with her new master of horse. And that's all I'm saying.

Sources:

Mary Bateson, ed., Records of the Borough of Leicester. Vol. 3.

Historical Manuscripts Commission, The Manuscripts of Lord Middleton.

Eric Ives, Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Mystery.

Leanda de Lisle, The Sisters Who Would Be Queen

Hastings Robinson, ed., Original Letters Relative to the English Reformation. Vol. 2

December 17, 2011

The Lord of Misrule Comes to Court: 1551/52

In December 1551, as Edward VI's uncle Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, sat in the Tower of London awaiting execution, the king's court was preoccupied with another matter entirely: the Lord of Misrule. Some time before Christmas, John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, sent a letter "scribbled in haste" to Thomas Cawarden, the Master of the Revels, announcing the appointment of George Ferrers as Lord of Misrule, to serve for the twelve days of Christmas. Ferrers was a courtier and poet who later contributed to A Mirror for Magistrates, described by Scott Lucas as a "compendium of tragic monologues" by a series of historical personages.

Ferrers began his reign by, as he recalled later, "coming out of the moon." Despite this auspicious start, not all went smoothly at first. Ferrers wrote to complain to Cawarden that although his own costume was satisfactory, the same could not be said for the apparel of the gentlemen who were to accompany him on his grand entry into London. Cawarden also was expected to come up with, among other items, "counterfeit harness and weapons," a hobby-horse, eight vizers for a "drunken masque," and eight daggers and swords for the same purpose. Meanwhile, lest Cawarden fail to get the point of Ferrers's missive, the king's council, including the Duke of Northumberland, wrote a stern letter on January 3, 1552, expressing its disapproval of Cawarden's having "prepared not aptly" for the Lord of Misrule's entourage.

The beleaguered Cawarden, however, eventually rose to the occasion, and the Lord of Misrule's entry into London was a memorable one. As reported by the diarist Henry Machyn:

The iiij day of Januarii was mad a grett skaffold in Chepe hard by the crosse, agaynst the kynges lord of myssrule cumyng from Grenwyche; and landyd at Towre warff and with hym yonge knyghts and gentyllmen a gret nombur on horsebake sum in gownes and cotes and chynes abowt ther nekes, every man havyng a balderyke of yelow and grene abowt ther nekes, and on the Towre hyll ther they went in order, furst a standard of yelow and grene sylke with Sant Gorge, and then gonnes and skuybes, and trompets and bagespypes, and drousselars and flutes, and then a gret compeny all in yelow and gren, and docturs declaryng my lord grett, and then the mores danse dansyng with a tabret, and afor xx of ys consell on horsbake in gownes of chanabulle lynyd with blue taffata and capes of the sam, lyke sage men; then cam my lord with a gowne of gold furyd with fur of the goodlyest collers as ever youe saw, and then ys . . . and after cam alff a hundred in red and wyht, tallmen of the gard, with hods of the sam coler, and cam in to the cete; and after cam a carte, the whyche cared the pelere, the a . . . , [the] jubett, the stokes, and at the crose in Chepe a gret brod skaffold for to go up; then cam up the trumpeter, the harold, and the doctur of the law, and ther was a proclamasyon mad of my lord's progeny, and of ys gret howshold that he kept, and of ys dyngnyte; and there was a hoghed of wyne at the skaffold, and ther my lord dranke, and ys consell, and had the hed smyttyn owt that every body mytht drynke, and money [?] cast abowt them, and after my lord's grase rod unto my lord mer and alle ys men to dener, for ther was dener as youe have sene; and after he toke his hers, and rod to my lord Tresorer at Frer Austens, and so to Bysshopgate, and so to Towre warff, and toke barge to Grenwyche.

With the Duke of Somerset soon to die (he was executed on January 22), the scene at the scaffold, which included props such as stocks, manacles, a "heading ax," and a "heading block," was tasteless, to put it mildly, and more offense was to come. As reported by Jehan Scheyfve, the imperial ambassador:

[The Lord of Misrule] was accompanied by about 100 persons of the same description; and besides several witty and harmless pranks, he played other quite outrageous ones, for example, a religious procession of priests and bishops. They paraded through the Court, and carried, under an infamous tabernacle, a representation of the holy sacrament in its monstrance, which they wetted and perfumed in most strange fashion, with great ridicule of the ecclesiastical estate. Not a few Englishmen were highly scandalised by this behaviour; and the French and Venetian ambassadors, who were at Court at the time, showed clearly enough that the spectacle was repugnant to them.

Despite this lack of political correctness, or perhaps because of it, the Lord of Misrule was a hit at court. As the chronicler Grafton wrote of Ferrers:

Which Gentleman so well supplyed his office, both in shew of sundry sightes and devises of rare invention, and in act of divers enterludes and matters of pastime, played by persons, as not onely satisfied the common sorte, but also were very well liked and allowed by the counsayle and other of skill in the like pastimes: But best of al by the yong king himselfe, as appered by his princely liberalitie in rewarding that seruice.

Ferrers was indeed such a success that he was invited to reprise his role: in September 1552, the council wrote to Cawarden to announce Ferrers' appointment for the Christmas season of 1552/53. Soon, Ferrers was planning the festivities, which would include a "Triumph of Cupid" (with Venus and Mars also featured) for Twelfth Night of 1553. Sadly, the Christmas and New Year's of 1552 and 1553 would be the last ones Edward VI and the Duke of Northumberland would spend on earth.

Sources:

Sydney Anglo, Spectacle, Pageantry, and Early Tudor Policy. Second Edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997.

Calendar of State Papers, Spain, Volume 10: 1550-1552.

Jennifer Loach, Edward VI. Yale University Press, 1999.

H. R. Woudhuysen, 'Ferrers, George (c.1510–1579)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article..., accessed 17 Dec 2011]

Alfred John Kempe, The Loseley Manuscripts and Other Rare Documents.

John Gough Nichols, ed., The Diary of Henry Machyn.

December 4, 2011

Gifts to the King

As you're doing your holiday shopping, I thought you'd enjoy seeing this list of New Year's presents given to Henry VIII on January 1, 1532. A word about dating is necessary here: the new year officially began on March 25, but the custom of giving New Year's presents on January 1 was still observed. Christmas presents weren't given.

Those who gave the king a gift could generally count on one in return, usually in the form of a gilt cup, bowl, or pot. One person, however, was conspicuously excluded from the king's bounty in 1532: the queen, Catherine of Aragon. As Eustace Chapuys reported, Catherine tried to give her husband a present, to no avail:

The Queen having been forbidden to write letters or send messages to the King, and yet wishing to fulfil her duty towards him in every respect, caused to be presented to him on New Year's Day, by one of the gentlemen of the chamber, a gold cup of great value and singular workmanship, the gift being offered in the most humble and appropriate terms for the occasion. The King, however, not only refused to accept the present, but seemed at first very angry with the gentleman who had undertaken to bring it. Yet it appears that two or three hours afterwards the King himself desired to see the cup again, praised much its shape and workmanship, and fearing lest the gentleman of his chamber who had received it from the Queen's messenger should take it back immediately—in which case the Queen might have it presented again before the courtiers (devant tout le monde), when he (the King) could not well refuse its acceptance—he ordered the gentleman not to give the cup back until the evening, which was accordingly done, and it was then returned to the Queen. The King, moreover, has sent her no New Year's gift on this occasion, but has, I hear, forbidden the members of his Privy Council, as well as the gentlemen of his chamber, and others to comply with the said custom.

Chapuys also reported that Henry had not sent gifts to Catherine of Aragon's ladies or to Princess Mary, although the list indicates that Mary did in fact receive gifts: two gilt pots, three gilt bowls with a cover, and a gilt layer.

The most important woman in Henry's life in 1532, of course, was Anne Boleyn, and as Chapuys reported, she was not forgotten:

The King has not been equally uncourteous towards the Lady from whom he has accepted certain darts, worked in the Biscayan fashion, richly ornamented, and presented her in return rich hangings for one room, and a bed covered with gold and silver cloth, crimson satin, and embroidery richer than all the rest.

Eric Ives indicates that the "darts" were probably boar spears.

Here's what others, ranging from an unnamed "dumb man" to Henry's sister, gave to the king. Their gifts included Parmesan cheese, various birds and beasts, gold and silver items, homemade items, and the always welcome, if unimaginative, present of money:

By the French queen [Henry's sister Mary, Duchess of Suffolk], a pair of writing tables with a gold whistle.

Bishops.— Canterbury, 2 plain gilt pots, 111½ oz. York, 50l. in a purple velvet purse. Carlisle, 2 rings with a ruby and a diamond. Winchester, a gold candlestick; and the bishops of Durham, Exeter, Chester, Hereford, Lincoln, London, Llandaff, Ely, Rochester, and Bath, sums of money from 20 mks. to 50l. in purses or gloves; the bishop of Ely giving in addition a hawk.

Dukes and Earls.—Lord Chancellor, a walking staff, wrought with gold. The duke of Richmond, —. The duke of Norfolk, a woodknife, a pair of tables and chessmen, and a tablet of gold. The duke of Suffolk, a gold ball "for fume" (for perfume?), 8¾ oz. The marquis of Exeter, a bonnet trimmed with aglets and buttons and a gold brooch. The earl of Shrewsbury, a flagon of gold for rosewater, 9¾ oz. The earl of Oxford, 10 sovereigns in a glove, 11l. 5s. The earl of Northumberland, a gold trencher, 8 oz. 1 dwt. The earl of Westmoreland, a St. George on horseback, of gold, 1½ oz. The earl of Rutland, a white silver purse, 6l. 13s. 4d. The earl of Wiltshire [Anne Boleyn's father], a box of black velvet, with a steel glass set in gold. The earl of Huntingdon, 2 greyhound collars, silver gilt. The earl of Sussex a doghook of fine gold. The earl of Essex, —. The earl of Worcester, a doublet of purple satin embroidered. The earl of Derby, 2 bracelets of gold enamelled blue, 5 oz. 3½ q.

Lords.—Lord Chamberlain, a pair of silver gilt candlesticks. Darcy, 6l. 13s. 4d. in a crimson satin purse. St. John's, a gold salt and a dozen of carpets. Lisley, 20l. lacking 6d., in a blue satin purse. Edmond Haward, —. Dawbeney, a piece of cameryk. Awdeley, a goodly sword, the hilt and pommel gilt and garnished. Stafford, a gold doghook. Mounttague, a piece of camerik. Mountyoie, an ivory coffer, garnished with silver gilt. Mountegill, a garter, buckle, and pendant of gold. Curson, 12 swans. George Grey, —. Rocheford [Anne Boleyn's brother George], 2 "hyngers" gilt, with velvet girdles. Wyndesour, a gold tablet with a small chain. Delawarre, —. Hussey, 7l. 10s. in a black purse. Morley, a book covered with purple satin. Souche, a fine shirt of camerik.

Duchesses and Countesses.—The old duchess of Norfolk, "The birth of our Lord in a box." The young duchess of Norfolk, a gold pomander. Lady Margaret Angwisshe, —. Lady marques Dorset, a great buckle and pendant of gold. Lady marques Exeter, a gilt cup with a cover. Countess of Shrewsbury, —. Lady of Salisbury, 2 pieces of camerik. Countesses of Kent, a corse for a garter. Wiltshire [Anne Boleyn's mother], a coffer of needlework, containing 6 shirt collars, 3 in gold and 3 in silver. Westmoreland, a brace of greyhounds. Huntingdon, 2 shirts. Worcester, 2 shirts with black work. Rutland, a piece of camrik. Derby, a black velvet girdle with gold buckles, pendants and bars.

Ladies.— Lady Powes, a dozen hawk's hoods of silver. Sandes, a gilt cup with a cover. Rocheford [Jane Boleyn, Anne's sister-in-law], 2 velvet and 2 satin caps, 2 being trimmed with gold buttons. Fitzwilliams, a comb of "ybanes." Mountegill, a diamond ring. Old lady Guldford, a garter with gold buckle and pendant. Young lady Guldford, a fine shirt. Lady Shelton, a garter of stoole work. Old lady Bryan, a dog collar of gold of damask with a lyalme. Lady Stannope, a regestre of gold. Verney, a regestre for a book. Lucye, 2 greyhound collars with studs and turrets, silver gilt. Kyngston, a shirt of camrik. Russell, a shirt wrought with black work. Russell, of Worcester, a shirt wrought with gold. Calthrop, a box with flowers of needlework and six Suffolk cheeses. Wyngfeld, a fine shirt. Cambage, a shirt with a black collar. Oughtrede, a fine shirt with a high collar. Browne, a shirt of camerik. Mary Rocheford, a shirt with a black collar.

Chaplains.—Abbots, viz., Glastonbury, —; Westminster, "Our Lady Assumption, and a crimson velvet purse, 22l. 10s."; Reading, 20l. in a white leather purse Peterborough, 20l. in a purse like a call of gold; St. Alban's, 30 sovereigns in a purse, 33l. 15s.; Ramsey, 20l. in a white bladder purse. The Master of the Rolls, —. The abbot of Abingdon, 20l. in a white leather purse with gold buttons. The abbot of St. Mary Abbey of York, 22l. 10s. The prior of Christchurch of Canterbury, 20l. in a glove. The prior of Tynnemouth, —. Peter Vannes secretary, 2 cushions very fine with needlework. The dean of the Chapel, a white satin purse with 7l. 17s. 6d. The dean of St. Stevens, a red leather purse with 10l. Dr. Fox, almoner, a piece of arras. Dr. Lupton, 10l. in a red leather purse. Dr. Rawson, 7l. in a red velvet purse. Mr. Sidnour, 20 mks. in a red leather purse. Dr. Wolman, 11l. 5s. The Princess's schoolmaster, a book. The archdeacon of Richmond, a standing cup. Dr. Bell, a ring with a ruby graven.

Gentlewomen.—Mrs. Hennege, a shirt.

Knights.—Sir Wm. Fitzwilliams, treasurer of the Household, a black greyhound and tirrets of gold. Sir Henry Guldford, comptroller of the Household, a gold tablet. Sir Bryan Tewke, treasurer of the Chamber, six "soufferanes" in a red satin purse, 6l. 15s. Sir Hen. Wyatt, 11l. 5s. in a red leather purse. Sir Edw. Nevyle, a piece of cloth enclosed within a Turkey box. Sir John Daunse, five sovereigns in a white paper, 5l. 12s. 6d. Sir John Gauge, a gold tablet hand in hand. Sir Arthur Darcy, a pair of virginals. Sir Edw. Seymer, a sword, the hilts gilt with "kalenders" upon it. Sir Wm. Kyngston, a bonnet with gold aglets and buttons. Sir Edw. Baynton, a black velvet cap garnished with aglets and buttons of gold, enamelled white, and a brooch upon it. Sir Antony Browne, a gold tablet with a dial in it. Sir John Aleyn, a salt with a trencher for eggs, silver gilt, 24½ oz. Sir Ric. Weston, a casket and a tablet of Mary Magdalen. Sir John Nevyle, a woodknife with a sheath and girdle of velvet. Sir Fras. Bryan, a black velvet bonnet with a chain, aglets, and a brooch of gold. Sir Thos. Cheyne, a gilt cup of assay, 7 oz. Sir Ric. Page, —. Sir Nic. Caroo, a gilt cup of assay, 7 oz. 1½ q. Sir Thos. Palmer, a tablet of gold, with a devise of Adam and Eve, and an hanging pearl thereat. Sir John Russell, a box for perfume, silver and gilt. Sir Edw. Guldeford, a falcon. Sir Geo. Lawson, 2 "rakkyng geldynges;" one grey, the other black bay. Sir Nic. Harvey, a ring with a seal of a George with a dial in the same.

Gentlemen.—Henry Norres, a cup with a cover, gilt, 49 oz. 1½ q. Robt. Amadas, 6 sovereigns in a white paper, 6l. 15s. Mr. Sulliard, a gilt salt with a cover. Cromewell, a ring with a ruby; and a box with the images of the French king's children. [John] Wellisborne, "a pair of carving knives, containing 8 pieces," with ivory hafts, garnished with silver and gilt. Thos. Hennege, a silver gilt cup, 27 oz. 1½ q. John Calvacant, a gilt chest with 44 alabaster pots, and a box full of fine thread. Geo. Ardyson, a piece of fine cambric. Domyngo, a ring set with a pointed diamond. Penyson, a shaving cloth wrought with "leyd worke," and a comb case of ebony. Dr. Bentley, a gold tablet with a pomander. Chr. Myllinour, a gold brooch with a flower. Wm. Knevett. Thos. Warde, a woodknife. Young Weston, 5 javelins. Bastard Fawkonbrige, a black silk girdle, with buttons and tassels. Wm. Lokke, mercer, a cupboard of plate. Antony Cassydony, triacle and a cheese of Parmasan. Jerome Molyne and Mathew Barnard, a pair of beads with perfume. Goron Bartinis, Italian, a gold ring fashioned like a rose. Alerd Jueller, a goodly shaving cloth. Lee, gentleman usher, —. Rawlyns, a spear of Calais, a sword with a sheath of black velvet. Antony Antonys, —. Fras. Borrone, milliner, a brooch of gold. Harman Hull, an Easterling, a leopard. Lucas Gunner, a standish of alabaster. Wm. Kendall, a case with 47 figures gilt. Hubbert of St. Kateryns, 3 partriches of Portingale and Marmylade. Thos. Flower, a salt silver gilt standing upon a dragon, 21 oz. A dumb man, a jowl of sturgeon. Vincent Woulf, 2 long and 2 round targets. Bartholomew Tate, a shaving cloth embroidered with gold, and an ivory comb case. Thos. Alford, a cambric shirt. Skydmour, 6 doz. trenchers. Stephen Andrew, a beast called a civet.

So did these presents to the king give you any ideas for your shopping list?

Sources:

Calendar of State Papers, Spain

Eric Ives, The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn

Letters and Papers of Henry VIII

Neil Samman, The Henrician Court During Cardinal Wolsey's Ascendancy, c.1514-1529. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Wales, 1988.

November 28, 2011

The Real Adrian Stokes

Following the execution of her first husband, Frances Grey, Duchess of Suffolk, married a commoner, Adrian Stokes. Stokes has usually been depicted in nonfiction and fiction as a poorly educated boy-toy, who disappeared into obscurity following the death of his wife. The real Adrian Stokes, however, was quite different.

To begin with, it is a myth that Adrian was much younger than Frances: a friend of his, the antiquary Lawrence Nowell, recorded his date of birth to the hour: 8 p.m. on March 4, 1519. This makes him less than two years younger than his bride, born on July 16, 1517. He is identified in some sources as being a Welshman, but I have found nothing to support this. The entry for him on the History of Parliament site suggests that he was a son of Robert Stokes of Prestwold. He had two known brothers, William and Anthony Stokes, and named a Robert Price (or Aprice) as his cousin and a John and Francis Gates as his kinsmen.

By 1547, Adrian was serving in France at the garrison of Newhaven in the Pale of Calais. He was the marshal of Newhaven and, along with William, Lord Stourton, and Sir Richard Cavendish was a member of the council there. In August 1549, Newhaven fell to the French. The king's council ordered in January 1550 that Adrian and the ten men who had served under him receive their wages.

John Gray, a younger brother of Henry Grey, Marquis of Dorset (later Duke of Suffolk), had been the deputy of Newhaven, and it may have been this connection that brought Adrian into the marquis's household—assuming that he was in it at all, for his exact position is murky. Elizabeth I's biographer William Camden simply described him as a "mean gentleman," whom Frances married "to her dishonor, but yet for her security," but does not name him as holding any particular role in the Suffolk household. Elizabeth herself once asked Bishop de Quadra what King Philip would think if she married one of her "servitors," as the Duchess of Suffolk and the Duchess of Somerset had done, but as Katherine Brandon, Duchess of Suffolk, had also married a member of her household, it is unclear whether Elizabeth was referring to Frances or to Katherine. Leicester's Commonwealth, the anonymous libel against Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, does expressly identify Adrian as Frances's horse-keeper, and it may be accurate on this point.

Nothing else is heard of Adrian until he married Frances Grey, Duchess of Suffolk, whose husband had been executed on February 23, 1554. According to a postmortem inquisition for Frances taken in 1560, Adrian and Frances married on March 9, 1554, at "Kayhoe [Kew] in the county of Surrey." The date has recently been called into question, but given the preciseness of the information contained in the inquisition, and the other dates it supplies, it seems more likely than not that the 1554 date was correct, especially since the information could have easily have come from Adrian himself. Interestingly, Frances's stepmother, Katherine, Duchess of Suffolk, held a life interest in a house at "Kayho," yet another variation on the spelling of "Kew." Perhaps Katherine, who herself had married one of her servants, Richard Bertie, had had a hand in Frances's marriage, and had offered her home for the ceremony?

What motivated the couple to marry is unknown. William Camden commented that the marriage was "to [Frances's] dishonor, but yet for her security," and it is quite possible that the duchess married beneath her in order to distance herself from the throne. Adrian's motives might be dismissed as mercenary, since he gained a titled, wealthy wife, but it should be remembered that in March 1554, just weeks after the deaths of Frances's daughter Jane and her husband, Frances's position was precarious. She could not be certain that she herself would not be implicated in her husband's treason or that she would be allowed to retain any of her property. Thus, she was not the most desirable of brides at the time. Perhaps Adrian married her because he believed she needed a protector.

It is possible that Frances and Adrian kept their marriage secret for a while, since a grant of land from the queen in May 1554 mentions only Frances, not Adrian, and the imperial ambassador wrote in April 1555 that it had been suggested that Frances marry the Earl of Devon. In any case, by at least July 1557, the couple was known to be married, as they were mentioned together in grants of land.

Agnes Strickland writes that on November 20, 1554, Frances gave birth to a daughter, Elizabeth, who died that same day. Strickland cites no source for this claim, and I have not found anything to corroborate it. Frances's postmortem inquisition does state that she and Adrian had a daughter named Elizabeth, but it says that the child was born on July 16, 1555, and that she died on February 6, 1556. The inquisition indicates that the couple had "others lawfully begotten" as well, but gives no particulars. If there were other children besides Elizabeth, none survived the marriage.

Elizabeth Stokes is said in the postmortem inquisition to have been born and died at Knebworth in Hertfordshire. Frances had no connection to the manor that I have found; it was in the hands of the Lytton family. Perhaps Frances and Adrian were leasing the manor? Frances was not hard up for land; in April 1554, she was granted a number of manors by the crown for life, chiefly Beaumanor in Leicestershire. Perhaps the little girl had been born at Knebworth while Frances was attempting to travel to Leicestershire and was too sickly to be moved to Frances's own estates.

Contrary to legend, there is no record of Queen Mary objecting to Adrian and Frances's marriage or of her deeming Frances unfit to raise her daughters, though Frances does seem to have spent little time at court after her marriage. If one of Frances's motives in marrying Adrian was to demonstrate her lack of ambition for the crown, it would be hardly surprising if Frances chose to avoid the court. Her daughter Katherine Grey, however, did at some point become one of Mary's ladies, and Frances was successful in introducing her first husband's niece, Margaret Willoughby, at court. Mary eventually found a place for Margaret in Elizabeth's household.

On November 17, 1558, Mary died, leaving the throne to her sister Elizabeth. When the new queen opened her first Parliament on January 12, 1559, Adrian was a member of the House of Commons, representing Leicestershire. The records of the 1559 Parliament, which are described on the History of Parliament website as defective, do not indicate on what committees he served.

Sadly, while Adrian's prestige was increasing, his wife's health was failing. By early November 1559, Frances was setting her affairs in order. On November 9, 1559, she executed her will, which left all of her property in Adrian's hands and appointed him her sole executor. She died on November 21, 1559, and was buried at Westminster Abbey on December 5, 1559. In 1563, Adrian erected a tomb to her memory. Its Latin inscription reads, as translated by the Westminster Abbey site, "Dirge for the most noble Lady Frances, onetime Duchess of Suffolk: naught avails glory or splendour, naught avail titles of kings; naught profits a magnificent abode, resplendent with wealth. All, all are passed away: the glory of virtue alone remained, impervious to the funeral pyres of Tartarus [part of Hades or the Underworld]. She was married first to the Duke, and after was wife to Mr Stock, Esq. Now, in death, may you fare well, united to God." If Adrian composed the inscription himself, as seems quite likely, he had plainly been educated in the classics.

Meanwhile, while serving Mary, Katherine Grey had fallen in love with Edward Seymour, the young Earl of Hertford. About a year after Frances's death, Katherine and Hertford secretly married. When the heavily pregnant Katherine revealed the couple's secret, the outraged Queen Elizabeth ordered her to be imprisoned in the Tower. In the investigation that followed, Adrian Stokes was one of those called upon to give depositions. According to Adrian, he and Frances had discussed the possibility of the couple marrying, after which Adrian approached Hertford and advised him to talk with members of the queen's council who could intervene on his behalf. Frances, meanwhile, had Adrian draft a letter to the queen in which Frances stated that the marriage was the only thing she desired before her death and that it would be an occasion for her to die the more quietly. Katherine Grey testified that Adrian advised Frances to write to the queen but that Frances was so sick that she never wrote the letter and died soon thereafter. One wonders if Frances would have been able to persuade the queen to allow the couple to marry had she lived a little longer.

The imprudent behavior of his stepdaughter did not harm Adrian's standing with the queen. In 1563 he was allowed to continue leasing Beaumanor, where he and Frances had spent part of their married life. Through the law of tenancy by curtesy, he also held a life interest in Frances's estates in Lincolnshire, Warwickshire, and Somerset.

As the owner of the manor of Astley in Warwickshire, Adrian pulled the spire off Astley's church for its lead, to the dismay of the inhabitants, who complained that "he had caused the tall and costly spire of their church, made of timber, together with the battlements, al covered with lead, to be pulled down, being a landmark so eminent in that part of the woodland, where the ways are not easy to hit, that it was called the Lanthorn of Arden; as also of the two fair aisles, and a goodly chapel called St. Anne's chapel adjoining, the roofs of which were also leaded, by reason of which sacrilegious action, the steeple, standing in the midst, took wet, and decayed (and afterwards fell to the ground)."

In 1565, Adrian's other stepdaughter, Mary Grey, followed her older sister's example and married without the queen's permission. Since Mary's choice of husband, Thomas Keys, sergeant porter to the queen, was well beneath her in rank, Mary might have thought that the marriage, like that of her mother to Adrian, would not provoke the queen. Unfortunately, she guessed wrong, and she and her husband were both imprisoned, Thomas in the Fleet and Mary in various private houses.

Adrian now had two stepdaughters in royal custody for marrying without royal permission. There is no indication that he petitioned for their release, but it is very unlikely that he would have succeeded. Katherine Grey died in 1568, a captive to the end of her life.

Throughout the 1560's, Adrian served on various commissions in Leicestershire. In 1571 he was again elected to Parliament for Leicester. He served on committees on religion and church government, treasons, abuses in conveyancing, the order of business, respite of homage and church attendance, apparel, and corrupt presentations.

On April 10, 1572, Adrian received a general license to marry Anne Throckmorton, the widow of Sir Nicholas Throckmorton and the daughter of Sir Nicholas Carew. Like that of Frances, Anne's family was tainted with treason. Her father had been executed during Henry VIII's reign for his suspected involvement in the Exeter conspiracy, and her husband Nicholas Throckmorton had spent some time under house arrest for supposedly encouraging Mary, Queen of Scots to marry the Duke of Norfolk. Nicholas had died the previous year when he fell ill while visiting Robert Dudley, the Earl of Leicester. Anne Throckmorton was left with six sons, the eldest of whom was not of sound mind, and one daughter, Elizabeth. While Adrian Stokes was her social inferior, the match was a good one for the widowed Anne in material terms. She and Adrian probably had known each other for many years, as Anne had served as Jane Grey's proxy at the christening of Guildford Underhill on the last day of Jane's brief reign as queen.

Soon after Adrian's remarriage, Mary Grey, whose husband had died, was allowed to go free. For a few months, she lived with Adrian and his new family before settling into her own house in London. Mary died in April 1578. In her will, she left Adrian's wife a silver gilt bowl with a cover.

In 1573, Walter Devereux, Earl of Essex, prepared to go into Ireland. Stokes wrote from Beaumanor on June 24, 1573, to tell him that he thanked God that the earl was going "because I am fullie perswaded your jorney shalbe greatlie to the service of God, for that you shall drive out those which knoweth not God, and plant in those that shall drive out those which knoweth not God, and plant in those that shall lyve in his feare."

The Gray's Inn Admission Register shows that in 1574, Adrian was one of several men admitted as readers at the request of Sir Christopher Yelverton. Francis Hastings, who was a younger brother of Henry Hastings, Earl of Huntingdon, and who often served with Adrian on local commissions, was also admitted at this time at Yelverton's request.

In 1574, William Lambarde presented Adrian with four maps that had belonged to Adrian's friend Laurence Novell, who had died in 1570.

Adrian served the crown at the local level in the 1570's and 1580's. In 1576, the queen's privy council directed him and Francis Hastings to inform themselves about the nefarious doings of "one Tomson, professing to be a refiner of gold." In the following year, he was serving as the keeper of the queen's park at Brigstock. When Nicholas Allen, one of Stokes' servants, was awaiting trial for killing one of Lord Mordant's servants, the privy council warned the justices of assizes that if Allen was found guilty, they should not give judgment for his execution until "her Majesty shall signifie her further pleasure." Lord Mordant himself, who had been unlawfully hunting in the park, was warned by the privy council not to offer any occasion of quarrel to Stokes, his friends, or his servants.

Walter Mildmay, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, wrote to Adrian on February 6, 1581, asked him to settle a dispute between Adrian Farneham of Quarndon, a minor, and his tenants in Barrow over common pasturage rights.

Arthur Throckmorton, the second son of Adrian's wife Anne, kept a journal, and it is because of this that we have a glimpse into Adrian's personal life during the period after his second marriage. In 1579, Adrian gave Arthur five pounds, which Arthur spent on fine clothing, including carnation silk stockings. That summer, Adrian served as godfather to Henry Cavendish's son; Arthur acted as his proxy. (Henry Cavendish was the son of Bess of Hardwick, who had been close to Frances.) While Arthur was visiting Beaumanor that summer, Adrian and Anne received many visitors, including Thomas Wilkes, a clerk of the queen's privy council, and Cavendish. Stokes and his wife visited George Hastings, another younger brother of the Earl of Huntingdon, and went hunting in his park at Gopsall. After Adrian and Anne returned to Beaumanor, they were visited by Lord and Lady Cromwell and their daughter; the couples then went to the Earl of Bedford's on a hunting trip and killed a buck. That October, Arthur recorded that he "fell out" with Adrian, though by the next spring the two were exchanging letters. In September 1582, Arthur, in debt following a tour abroad, received presents from Adrian and his mother. Later that autumn, Arthur stayed at New Wark, a house Adrian owned at Leicester. In March 1583, George Hastings and his wife again visited Beaumanor.

Meanwhile, in 1582, Adrian assigned his interest in the lease of Beaumanor to his brother William and to their cousin, Robert Apyrce, on the condition that after Adrian's death they provide maintenance to John and Francis Gates, two kinsmen of Adrian's who were studying at the university, and to three of Adrian's servants.

Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth's Principal Secretary, wrote a letter to Sir Ralph Sadler on October 6, 1584, advising him that he should keep a watchful eye on Mary, Queen of Scots, and that if his own servants were not well furnished with "dagges" or "petronells," he should procure some from the well-affected gentleman in that county. Walsingham believed that none would better furnish him than Adrian Stokes, but noted that he dwelled somewhat far off.

In April 1585, Arthur Throckmorton was informed by the Earl of Leicester that Adrian was dead. Arthur hurried to Beaumanor only to discover that the report was a false one. Adrian, however, was probably seriously ill, for he made his will on April 15, 1585. On November 2, 1585, he died at age sixty-six.

Adrian asked to be buried in the chapel of Beaumanor without any pomp or solemnity "as yt hath bene used in the Papistes tyme." He left Anne his manor and lordship of Langacre in Devonshire, all of the goods and furniture in his houses in London and at Brigstock, the lease and interest in his house at Leicester and the goods there, and those plate and goods at Beaumanor specified in an inventory. To his stepdaughter Elizabeth Throckmorton he left a bed in the duchess's chamber, with the furniture to be given to her on her marriage (Elizabeth would later secretly marry Sir Walter Ralegh, making her the third stepdaughter of Adrian to incur the queen's wrath for marrying on the sly.) He left his horse "Grey Goodyeare" to Robert Throckmorton and his horse "Grey Babington" to George Hastings. Stokes left the rest of his goods to his brother William, who was sixty. He appointed his friend George Hastings (who became the Earl of Huntingdon a decade later following the death of his childless brother) and Sir Walter Mildmay to be the supervisors of his will.

The goods at Beaumanor left to Anne Throckmorton included 1290 ounces of plate. Adrian's goods at his London house included a pair of virginals, a picture of a French king, a Book of Martyrs, and portraits of Katherine Parr, Mary I, and the "French Queen" (Frances's mother. Mary Tudor). Perhaps the last lady, who had married once for policy and once for love, might have sympathized with Frances's choice of a second husband.

Sources:

C 142/128/91 (inquisition postmortem for Frances, Duchess of Suffolk).

Acts of the Privy Council of England.

Mary Bateson, ed., Records of the Borough of Leicester.

Carl T. Berkhout, "Adrian Stokes, 1519-1585." Notes and Queries, March 2000.

Calendar of Patent Rolls.

Calendar of Scottish Papers.

Joseph Lemuel Chester and Sir GeorgeJohn Armytage, eds., Allegations for Marriage Licenses Issued by the Bishop of London, 1520 to 1610.

Joseph Foster, ed., Gray's Inn Admission Register: 1521-1887.

The History of Parliament (online entry for Adrian Stokes).

Joseph Jackson Howard, ed., Miscellanea Genealogica et Heraldica.

C. S. Knighton, ed., Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, Mary I, 1553-1558.

Leicester County Council, Record Office Catalogue.

Leanda de Lisle, The Sisters Who Would Be Queen.

National Archives.

John Nichols, The History and Antiquities of the County of Leicester.

A. L. Rowse, Ralegh and the Throckmortons.

November 13, 2011

Was Henry VIII Having an Affair with the Duke of Buckingham's Sister?

In May 1510, Henry VIII is supposed to have strayed from the marital bed of Catherine of Aragon, taking as his partner Anne, Lady Hastings, a sister of Edward Stafford, Duke of Buckingham. Indeed, book after book confidently asserts that Anne was Henry's mistress, at least for a short time.

In May 1510, Henry VIII is supposed to have strayed from the marital bed of Catherine of Aragon, taking as his partner Anne, Lady Hastings, a sister of Edward Stafford, Duke of Buckingham. Indeed, book after book confidently asserts that Anne was Henry's mistress, at least for a short time.

Anne was the younger daughter of Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham (executed in November 1483 for rebelling against Richard III) and Katherine Woodville, the youngest sister of Elizabeth Woodville, Edward IV's queen. Anne's husband, George Hastings, became the first Earl of Huntingdon in 1529. His grandfather, William, Lord Hastings, had also been executed by Richard III.

George was born in 1486/87; Anne could have been born no later than 1484, making her some years the senior of Henry VIII, born in 1491. Anne and George were newlyweds in May 1510, having been married in December 1509. It was Anne's second marriage; she was the widow of Sir Walter Herbert, the illegitimate son of William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke.

Elizabeth, Anne's older sister, was married to Robert Radcliffe, Lord Fitzwalter. Both women served Catherine of Aragon, and this was where the trouble started. As Don Luis Caroz, the Spanish ambassador, reported on May 28, 1510 (the brackets are those of the State Papers, Spanish editor):

What lately has happened is that two sisters of the Duke of Buckingham, both married, lived in the palace. The one of them is the favourite of the Queen, and the other, it is said, is much liked by the King, who went after her. Another version is that the love intrigues were not of the King, but of a young man, his favourite, of the name of Conton, who had been the late King's butler. This Conton carried on the love intrigue, as it is said, for the King, and that is the more credible version, as the King has shown great displeasure at what I am going to tell. The favourite of the Queen has been very anxious in this matter of her sister, and has joined herself with the Duke, her brother, with her husband and her sister's husband, in order to consult on what should be done in this case. The consequence of the counsel of all the four of them was that, whilst the Duke was in the private apartment of his sister, who was suspected [of intriguing] with the King, Conton came there to talk with her, saw the Duke, who intercepted him, quarrelled with him, and the end of it was that he was severely reproached in many and very hard words. The King was so offended at this that he reprimanded the Duke angrily. The same night the Duke left the palace, and did not enter or return there for some days. At the same time the husband of that lady went away, carried her off, and placed her in a convent sixty miles from here, that no one may see her. The King having understood that all this proceeded from the sister, who is the favourite of the Queen, the day after the one was gone, turned the other out of the palace, and her husband with her. Believing that there were other women in the employment of the favourite, that is to say, such as go about the palace insidiously spying out every unwatched moment, in order to tell the Queen [stories], the King would have liked to turn all of them out, only that it has appeared to him too great a scandal. Afterwards, almost all the court knew that the Queen had been vexed with the King, and the King with her, and thus this storm went on between them. I spoke to the friar about it, and complained that he had not told me this, regretting that the Queen had been annoyed, and saying to him how I thought that the Queen should have acted in this case, and how he, in my opinion, ought to have behaved himself. For in this I think I understand my part, being a married man, and having often treated with married people in similar matters. He contradicted vehemently, which was the same thing as denying what had been officially proclaimed. He told me that those ladies have not gone for anything of the kind, and talked nonsense, and evidently did not believe what he told me. I did not speak more on that subject. I spoke with him in order to try whether I could not in this or that manner discuss with him some pending affairs, and [to remind him] that he never ought to consider me as a stranger in these matters, but until this time I have not found him serviceable to me. He is stubborn, and as the English ladies of this household as well as the Spanish who are near the Queen are rather simple, I fear lest the Queen should behave ill in this ado. She does so already, because she by no means conceals her ill will towards Conton, and the King is very sorry for it.

"Conton" is identified by the editor as William Compton, Henry VIII's groom of the stool. A detail that is often added to this tale is that upon catching Compton, Buckingham bellowed, "Women of the Stafford family are no game for Comptons, no, nor for Tudors either!" The quotation does not appear in the ambassador's report, however, and in fact it seems that Buckingham never actually said this. Rather, the comment was first made by Catherine's biographer Garrett Mattingly in his description of the incident: "Whether out of loyalty to the Queen or to her family, the elder sister alarmed her brother, who surprised the gallant Compton in the younger's chamber. Buckingham was furious. Women of the Stafford family were no game for Comptons, no, nor for Tudors either." At some point, historians began putting Mattingly's comment directly into Buckingham's mouth, presumably thinking that it was something the choleric duke might have said.

But was Anne actually Henry's mistress? Nothing in the ambassador's report, which is the sole source for this incident (an abbreviated version appears in the Letters and Papers of Henry VIII), indicates how far their relationship, if any, had actually gone. They could have been lovers, or they could have been progressing toward an affair that was cut short by the intervention of Anne's sister and the duke. Alternatively, they could have just as easily been having a harmless flirtation or playing at the game of courtly love–and, of course, it is also possible that nothing untoward at all had been going on between the king and Anne. Henry's anger could have been caused by annoyance that Anne's sister and brother were upsetting the queen with their suspicions, or irritation that Buckingham was reprimanding one of his favorite courtiers, and Katherine's anger could have been at Henry's dismissing one of her favorite ladies. Still, for the New Year of 1513, the king presented Anne with a silver-gilt cup weighing over thirty ounces. This was a large gift for one of the queen's ladies, as Neil Samman points out, but the list is not complete, as Samman also notes; it represents the work of only one of several goldsmiths employed to make gifts from the king that year. Anne's gift was dwarfed by that given to Catherine of Aragon: two great pots weighing over 575 ounces and costing over 143 pounds. Moreover, both Anne and her sister Elizabeth gave Henry New Year's gifts in 1513, so it is possible that Elizabeth received an unrecorded gift comparable to that of her sister.

Anne's name continued, however, to be linked with that of William Compton, even after 1513 when he married a lady with the unmelodious name of Werburga, who was the widow of Sir Francis Cheyne and the daughter of Sir John Brereton. At some unspecified date, according to Barbara Harris, Compton took the sacrament as proof that he had not committed adultery with Anne. Whether or not this was true, in 1523, Compton made a will in which he left Lady Hastings a life interest in part of his land, which, as Harris notes, was highly unusual for a man to do for a woman who was not a close relation. Compton, who died of the sweating sickness in 1528, also specified that masses be said for the souls of the king, the queen, and Lady Hastings, as well as the souls of himself and his wife.

Whatever happened or did not happen between Anne, Henry, and Compton, Hastings appears to have borne a great deal of affection toward Anne. In a 1525 letter quoted by Harris, he wrote, "with all my whole heart, I recommend me unto you as he that is most glad to hear that you be merry and in good health," and in his will he treated her most generously and named her as one of his executors. The couple had eight children; their eldest son, Francis, was born in 1513/14. Their grandson Henry Hastings, the third Earl of Huntington, married Katherine Dudley, the youngest surviving daughter of the Duke of Northumberland, as part of the triple wedding that starred Guildford Dudley and Jane Grey. Another Hastings grandchild, Mary, received a proposal from Ivan the Terrible, much to her dismay; fortunately, Queen Elizabeth shared Mary's distaste for the match and fended off the czar.

Sources:

Calendar of State Papers, Spanish

Claire Cross, The Puritan Earl: The Life of Henry Hastings, Third Earl of Huntingdon, 1536-1595.

Barbara J. Harris, English Aristocratic Women, 1450-1550.

Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII

Garrett Mattingly, Catherine of Aragon

Beverly A. Murphy, Bastard Prince: Henry VIII's Lost Son.

Neil Samman, The Henrician Court During Cardinal Wolsey's Ascendancy, c.1514-1529. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Wales, 1988.

November 7, 2011

Did Katherine Howard Say That She Would Rather Die the Wife of Thomas Culpeper?

In case you think you're going mad, yes, this post did originally appear on another blog. I set up a separate blog entitled "Tudor Myths and Misconceptions," but after giving it some thought, I've decided it's impractical (and slightly insane) to try to maintain two blogs. So the post you saw on the other blog appears below, and I'll be deleting the other blog. (What I said on the other blog about wanting guest posts about Tudor myths still holds true, though.)

What I have retained, however, is my new Facebook page, Tudor Myths and Misconceptions. Hope you'll join us there!

And here, without further ado, is my post on Katherine Howard.

According to many books and websites, Katherine Howard, standing on the scaffold on February 13, 1542, pronounced, "I die a queen, but I would rather die the wife of Thomas Culpeper." Myth or fact?

The story that Katherine Howard said the words above comes from the anonymous Chronicle of King Henry VIII, better known to us as the Spanish Chronicle, which was translated from the Spanish and edited by Martin Hume.

When she mounted the scaffold she turned to the people, who were numerous, and said, "Brothers, by the journey upon which I am bound I have not wronged the King, but it is true that long before the King took me I loved Culpepper, and I wish to God I had done as he wished me, for at the time the King wanted to take me he urged me to say that I was pledged to him. If I had done as he advised me I should not die this death, nor would he. I would rather have him for a husband than be mistress of the world, but sin blinded me and greed of grandeur, and since mine is the fault mine also is the suffering, and my great sorrow is that Culpepper should have to die through me." Then she turned to the headsman and said, " Pray hasten with thy office." And he knelt before her and asked her pardon, and she said, "I die a Queen, but I would rather die the wife of Culpepper. God have mercy on my soul. Good people, I beg you pray for me." And then, falling on her knees, she said certain prayers, and the headsman performed his office, striking off her head when she was not expecting it. She was carried to the Tower Church, and buried near Queen Anne.

As John Schofield notes in The Rise and Fall of Thomas Cromwell, however, the Spanish Chronicle "is far too cavalier with facts, dates and details to be a credible witness." Among other obvious inaccuracies, it turns Katherine Howard into Henry VIII's fourth wife and makes Anne of Cleves his fifth, describes George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford, as a duke, and has Cromwell, executed in 1540, investigating the adultery charges against Katherine Howard in 1541. It also depicts Culpeper, who was executed in December 1541, two months before Katherine's death, as dying the day after Katherine's execution. The words the chronicler attributes to the queen, then, have to be viewed with great skepticism.

A far more historically likely account of Katherine's last words was written on February 15, 1542, by the merchant Ottwell Johnson in a letter to his brother John. After discussing some herrings and wine he had bought for his mother and some business matters, Ottwell wrote:

And for news from hence, know ye, that, even according to my writing on Sunday last, I see the Queen and the lady Retcheford suffer within the Tower, the day following; whose souls (I doubt not) be with God, for they made the most godly and Christians' end that ever was heard tell of (I think) since the world's creation, uttering their lively faith in the blood of Christ only, with wonderful patience and constancy to the death, and, with goodly words and steadfast countenance, they desired all Christian people to take regard unto their worthy and just punishment with death, for their offences against God heinously from their youth upward, in breaking of all his commandments, and also against the King's royal majesty very dangerously; wherefor they, being justly condemned (as they said), by the laws of the realm and Parliament, to die, required the people (I say) to take example at them for amendment of their ungodly lives, and gladly obey the King in all things, for whose preservation they did heartily pray, and willed all people so to do, commending their souls to God and earnestly calling for mercy upon Him, whom I beseech to give us grace with such faith, hope, and charity, at our departing out of this miserable world, to come to the fruition of his Godhead in joy everlasting. Amen.

Other contemporary reports echo Johnson's. Eustace Chapuys, the imperial ambassador, wrote on February 25, 1542, simply, "After [Katherine's] body had been covered with a black cloak, the ladies of her suite took it up and put it on one side. Then came Mme. de Rochefort, who had shewn symptoms of madness until the very moment when they announced to her that she must die. Neither the Queen nor Mme. de Rochefort spoke much on the scaffold; all they did was to confess their guilt and pray for the King's welfare and prosperity." The French ambassador, Charles de Marillac, wrote to Francis I on the day of the execution, "The Queen was so weak that she could hardly speak, but confessed in few words that she had merited a hundred deaths for so offending the King who had so graciously treated her." It's hard to imagine that either of the ambassadors would have resisted mentioning the fact if Katherine had indeed declared that she wished to have died as Culpeper's wife.

Even a stopped clock tells the time right twice a day, and the Spanish Chronicle's account of Katherine's comments about Culpeper can't be ruled out entirely. Given the chronicle's other glaring mistakes, however, its account of Katherine's last words deserves to be taken with a very large shaker of salt.

Sources:

Calendar of State Papers, Spain, Vol. 6, pt. I

Chronicle of King Henry VIII of England, ed. Martin Andrew Sharp Hume

Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Vol. 17

November 5, 2011

The Horsey Master Stokes and the Gullible Mr. Marples

Where would the history of Lady Jane Grey and her family be without the intrepid Victorians? I came across this gem today while looking up a reference for Adrian Stokes. It's from a piece in the 1885-86 Proceedings of the Liverpool Literary and Philosophical Society called "A Noble Family of the Middle Ages" by one Josiah Marples, and professes to be nonfiction. Sadly, the author's source was the infamous Tablette Booke of Ladye Mary Keyes, a novel by Flora Francis Wylde that has fooled many a person, including most recently David Baldwin in his biography of Elizabeth Woodville, into citing it as a genuine memoir of Mary Grey.

There are a number of historical groaners in the excerpt below, but I'll just point out a few places where history and Mr. Marples part company. In reality, Frances died before her daughter Katherine Grey was put in the Tower and before her daughter Mary began her relationship with her future husband, Thomas Keyes; Frances married Adrian Stokes during Queen Mary's reign, not during Queen Elizabeth's; and the "aunt Eleanor" referred to here, Frances's younger sister, had died in the 1540′s.

___________

While Mary [Grey] was thus occupied with her attendance on the queen, and her practising on the virginalls, and, shall we add, her conversations with the porter [Keyes], her mother, the proud duchess, now approaching her fiftieth year, found it necessary to take much horse exercise, which had become fashionable, as the queen had caused to be introduced a new saddle, "on which," says Lady Mary, "a body was to sit side-ways." One day, however, the startling news came that the duchess had not returned from her ride, and further enquiry showed that her frequent excursions in the company of her "Master of the Horse" had resulted, as such rides have frequently resulted since, in a marriage between the Tudor duchess and her lowborn groom, Adrian Stokes. Poor Mary, well might she say " a bodye might have struck me down with a straw."

Katherine [Grey], in the Tower, took the matter a little more philosophically, and chuckled over the fact that "henceforth there will be no more talk of the renowned Tudor race from the lips of our Lady Mother, lest a Tudor ghost should arise, and with his mailed gauntlet, strike her dearly beloved, Master Adrian Stokes, nigh unto death." The duchess soon showed that if she had made a bad choice she would abide by it, for she wrote to Mary and told her of her marriage, and said that, as she preferred seclusion with her dear husband, she should henceforth live at Bradgate. She recommended Mary to follow her example and get married, and she concluded by saying she did not wish her, nor even Katherine, her favourite daughter, to visit her until they could accept Adrian Stokes as their father, with proper reverence and submission. It was quite anticipated that Elizabeth would have sent the couple to the Tower, but as, singularly enough, she was at the time supposed to have her own eyes fixed upon her "Horsekeeper," the Earl of Leicester, she said little about it, only expressing her astonishment that her aunt should have so demeaned herself. Alas, a very few months were sufficient to unmask the man, who turned out to be a common, ill-bred, "horsey" fellow, who sacrificed everything to his own low and vulgar tastes, broke horses on the lawn, and had the house full of dogs, while his poor wife—erst the proud duchess – was broken in health and spirit. At length Mary was sent for, and she and her aunt Eleanor, the Countess of Cumberland, went down with all speed, only to find the poor duchess lying at the point of death. While they were in her chamber, nearly heartbroken, they heard a great noise in the next room, and soon the door was thrust open by Stokes, who strode in with "good een to you bothe: I hope I see your ladyshippes well; looke at my poore ould woman now, isn't she bad? Beg pardon, ladies, for being covered before ye. But have a good heart, wife, you ain't a-goinge to drop on your race course yet." The duchess motioned him to leave the room,— "What! am I to go? Very well, have your own way, and live the longer," then adding, with a broad grin, "But a year agone things was different; I had no need to be trotted back like a lame horse. It 'b very good of your ladyshippes to come so far, so pray make yourselves right welcome—no formes here, all the bodyes do as they like." Soon after he left the room, with an awkward sort of reverence, slammed the door after him, and then they "heard his whistle on the back-stairs, calling to a number of great, huge, uncouth dogs, who barked and whined for many minutes afterwards as never did we hear afore." Mary adds, "Oh, that Master Stokes was an awful creature." The duchess lived only two days longer. Her first husband's brother, Lord John Grey, came the next day, and gave orders for the funeral after her death, for Stokes had gone for comfort to the brandy bottle, and was, of course, unfit to transact any business. The duchess's maid told Mary that some papers of importance were in the writing cabinet, and they were delighted to find, in a secret drawer, a deed of gift, legally drawn up and witnessed, giving Bradgate, and all its lands, to Lord John Grey, so that Master Stokes had to return to the mire from which he ought never to have been raised.

November 1, 2011

Lancastrian Jokes

My web hosting service shows me the search terms people use to reach my website. Among last month's was "Lancastrian jokes."

Well, to get to the point, I felt very sorry for this poor soul, trawling the Internet in a perhaps vain search for Lancastrian jokes. So I decided to come to the rescue with these. Who said the House of Lancaster wasn't a barrel of laughs?

Knock knock!

Who's there?

Ida.

Ida who?

Ida given up Maine long before this if you'd only asked sooner.

****

Doctor, doctor, I need an heir!

Don't stand here telling me about it—talk to your queen!

****

What is black and white and red all over?

A Lancastrian zebra!

****

Why did the Lancastrian cross the road?

To defect to Edward IV.

****

How many Lancastrians does it take to change a light bulb?

Seven. One to change the light bulb, one to pray with King Henry for the welfare of the new light bulb, two to bring the Duke of Suffolk and the Duke of Somerset their own light bulbs, two to hold Queen Margaret's train while she watches the bulb being changed, and one to stand against the door so the Duke of York doesn't find out.

October 30, 2011

Some Coronation Expenses for Henry VII

On October 30, 1485, Henry VII was crowned the first Tudor king of England. I'm on a non-writing-related deadline at the moment, so this will be a brief post, but I thought you might enjoy reading about some of the expenses for his coronation, taken from English Coronation Records by the splendidly named Leopold George Wickham Legg:

Item bought of M Chaderton prest a Furre of Ermyns powdered wt a longe trayne for a mantell

Item bought of Richard Swan Skynner xlij tymbre menever pure for the kinges Surcot of blue clothe

Item xxvij yerdes di purpulle veluet for a Robe of purpulle veluet

Item xlj yerdes crymsm veluet for my lorde of Oxforde Robe

Item bought of william Redy mercer iiij yerdes white clothe of golde for the bordour of the trappour of the Rede Roses

Item iij yerdes clothe of golde for the bastard somerset [This was Charles, the illegitimate son of Henry Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, executed in 1464.]

Item bought of Robert White mercer vi yerdes crymsyn veluet for the Dragons and rede roses of a trappour

Item xj yerdes di blue veluet for my lorde of dudley [This seems to have been the 85-year-old John Sutton, Baron Dudley, grandfather of Edmund Dudley and great-grandfather to John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland]

Item vj yerdes di crymsyw veluet for the crosse of Saint George

Item bought of Cecyly Walcot Silkwoman xxviij vnces frenge of gold and Silke for the canopye

Item xvj yerdes Riban of silk for leding Rayns

Item lxxj vnces of hangyng spangels of siluer and double gilt

Item to Thomas Madynwelle brawderer for enbraudering of a trappour of saint Edwards Armez

Item to hugh Wright brawderer for enbrawdering a trappour wt Fawcons

Item to henry Robert Brawderer for enbrawdring of a trappour of Cadwallader Armez

Item for trasshes in Westminster halle

Item bought of Robert boylet vMI j quarter gilte nailles for the stage at Westminster

Item viij Sadilles coueved in crymsyn veluet and ij saddles coueved in veluet for my lorde of bokingham and his broder [These were the seven-year-old Edward Stafford, Duke of Buckingham, and his younger brother, Henry Stafford. The young duke was made a Knight of the Bath before the coronation.]

Item deliuered to a francheman for to bye ij yerdes di of satyn for a doublet for hymself by the kinges commaundemente

October 21, 2011

More on Frances Brandon's Portraits

After writing my last post, I thought I would mention some of the various portraits that have been identified as depicting Frances Grey (née Brandon), Duchess of Suffolk. None has been authenticated as a portrait of her, but here's a look at the various candidates:

The painting below is by far the one most usually associated with Frances. For centuries, it was misidentified as a portrait of her and her second husband, Adrian Stokes. Recent scholarship has identified it as one of Mary Neville and her son, Gregory Fiennes, but centuries of error die hard. As dozens of books, nonfiction and fiction alike, have relied on this painting in depicting Frances's physical appearance (and even her personality), it's likely that it will be associated with Frances for years to come. (Incidentally, the myth that Adrian Stokes was half Frances's age rests largely upon this portrait; Stokes was actually only a couple of years Frances's junior. Before joining her household he was the marshal of Newhaven in France, where he commanded ten men until the fortress fell to the French in 1549.)

The drawing below by Hans Holbein was labeled "The Marchioness of Dorset" after Holbein's death in 1543. John Cheke, Edward VI's tutor, is said to have provided the labels for many of the portraits. Unfortunately, from 1533 to 1541, there were two Marchionesses of Dorset, Frances and her mother-in-law, Margaret Grey, née Wotton. Art historians have generally identified this portrait as being of Margaret rather than of Frances. Moreover, as Eric Ives has pointed out, the lady is carrying a walking stick, which seems an unlikely implement for Frances, who was only twenty-six at the time of Holbein's death, to be holding. The walking stick can be seen more clearly in the finished painting:

The next Holbein sketch, labeled "The Duchess of Suffolk" is usually identified as being that of Frances's stepmother, Katherine Brandon, Duchess of Suffolk. As Ives points out, Frances did not become a duchess until November 1551, so if Cheke made his identifications of the Holbein portraits before then, it would rule Frances out as a possible subject. If he made his identifications after that date, however, it is possible that "Duchess of Suffolk" referred to Frances rather than Katherine. The Holbein can be compared to the miniature of Katherine Brandon shown below it.

In his study of Frances's father, Charles Brandon, S. J. Gunn referred to the Holbein sketch below as being one of Frances, her daughters Jane and Katherine, and Charles's two sons by his marriage to Katherine Brandon. Gunn based his statement on Paul Ganz's identification of the sketch. As Dr. John Stephan Edwards pointed out when I asked him about the sketch, however, the British Museum dates this piece to 1532-33, before either Frances's children or the Brandon boys were born. It seems unlikely, then, that Frances is the sitter in this pleasant domestic scene.

In her biography Bess of Hardwick, Mary Lovell reproduced the portrait below as being one of Frances. This painting, which Lovell credited to the Royal Collection, can be found all over the Internet, identified as Frances, but I have found absolutely nothing about its date, the identity of the artist, or where it is held. Neither Ives nor Leandra de Lisle mentions it as a likeness of Frances. The ruff looks to me like something from the later part of the century (Frances died in 1559). If anyone knows anything about the provenance (there's just something nice and tweedy about the word "provenance," isn't there?) of this painting, please comment!

Finally, one undisputed image of Frances does exist: the effigy on her tomb at Westminster Abbey. Adrian Stokes, her widower, obviously hired an excellent craftsman to pay a last tribute to his duchess.