Susan Higginbotham's Blog: History Refreshed by Susan HIgginbotham, page 10

May 17, 2014

If Margaret, Why Not Cecily?

I belong to several Wars-of-the-Roses-related groups on Facebook, and every week or so, the inevitable question arises: Did Richard III murder his nephews? Each time, at least one person comments that Richard did not; rather, the murderer was Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond. After all, we’re told, she was a ruthlessly ambitious woman who would do anything to put her son, Henry Tudor, on the throne.

But there was another formidable matriarch in England in 1483, one who almost never gets named as a suspect, but who arguably had as good a motive , means, and opportunity as Margaret. Her name? Cecily, Duchess of York, mother to Edward IV and Richard III.

Before I go further (and before some of you start writing indignant comments), let me make myself clear: I do not believe that the Duchess of York was responsible for the deaths of her grandsons. I do not believe that Margaret Beaufort was responsible for their deaths either. Rather, I am writing simply to point out that if one can entertain the idea that Margaret was a murderer, logic dictates that one should also entertain the idea that Cecily was one. Why?

Before I go further (and before some of you start writing indignant comments), let me make myself clear: I do not believe that the Duchess of York was responsible for the deaths of her grandsons. I do not believe that Margaret Beaufort was responsible for their deaths either. Rather, I am writing simply to point out that if one can entertain the idea that Margaret was a murderer, logic dictates that one should also entertain the idea that Cecily was one. Why?

Cecily’s objection to her son Edward IV’s marriage to Elizabeth Woodville is well known, and there’s little indication that she ever warmed to her daughter-in-law. On these lines, it has been suggested that she supported her son Richard III’s bid for the throne, preferring to see him as king instead of her half-Woodville grandson Edward V. Assuming for the sake of argument that Cecily did indeed approve of Richard III’s actions, it stands to reason that she would want to see him remain on the throne once he got there. The plot to free Edward V and his brother from the Tower that emerged soon after Richard’s coronation could well have made Cecily to decide to help Richard’s cause by eliminating her grandsons.

Cecily had at least as good means and opportunity to kill Edward IV’s sons as did Margaret Beaufort, and quite probably better ones. As the mother of two kings, Cecily would have had the best of connections at court, and her house in London would have given her contacts in the city as well. Even if she couldn’t get into the Tower herself, she certainly had as much ability as did Margaret Beaufort to gain access to those who could. Indeed, as the boys’ grandmother, she had a perfectly plausible excuse to visit them in the Tower (perhaps taking them some poison-laced treats), unlike their more distant relation Margaret.

Furthermore, if Margaret Beaufort arranged for the deaths of Edward IV’s sons during Richard III’s reign in order to advance the cause of her son Henry Tudor, she was taking an enormous risk: if caught, she faced imprisonment at best, execution at worst, and her actions could have been used to discredit her son, putting paid to his chances of gaining support for his invasion. If Cecily, on the other hand, arranged for the boys’ deaths, she ran comparatively little risk, for even if Richard did not welcome such meddling, it would have hardly benefited him to publicize the fact that his own mother killed her grandsons.

One could argue that Cecily was too pious to arrange for the deaths of two innocent boys. But Margaret was equally pious, and those who argue for her guilt have never allowed this to stand in their way.

Cecily and Margaret had each known more than her share of trouble. The daughter of a possible suicide, Margaret was a widow and a mother by age fourteen. From 1455 to 1471, her male Beaufort relatives were killed one by one by the Yorkists, and her only son grew up in exile abroad. Cecily herself suffered the deaths in battle of her husband and her son Edmund, the execution of her son George, and the demise of a number of her children by natural causes. If life had hardened Margaret, there is every reason to believe that it hardened Cecily as well.

Moreover, the men in Cecily’s life had shown themselves to be ruthless when the occasion demanded it: her husband, Richard, Duke of York, had taken the opportunity to rid himself of Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, on the streets of St. Albans; her son Edward had ordered the execution of his own brother George; and her son Richard had executed William, Lord Hastings, without a trial. Perhaps Cecily, convinced that she was acting for the good of the realm, followed their example. Perhaps she even decided to take the sin of murder upon herself to spare Richard the responsibility.

Of course, there is a glaring difficulty in assigning guilt to Cecily: lack of evidence. No contemporary source suggests that Cecily had a hand in the deaths of Edward V and his younger brother. But no contemporary source suggests that Margaret did either. As the evidence stands today, neither the duchess nor the countess could be convicted in a court of law of murder. Yet whereas as far as I know only one or two rather obscure novels have cast Cecily in the role of murderess, Margaret (thanks largely in part to the television series “The White Queen”) has become a leading suspect, often crowding out Richard III and the perennial favorite, Buckingham.

Asked for evidence of her guilt, those implicating Margaret point rather vaguely to her ambition and her devotion to her son and, more specifically, to her role in the rebellion of October 1483. But while one could try to build a case for Margaret’s guilt upon this shaky foundation, it certainly doesn’t rule out Cecily as an alternative suspect.

As I said earlier, I do not believe that either Margaret or Cecily was responsible for the deaths of the Princes in the Tower. But for those who are convinced that Margaret was responsible, I leave with a parting thought. Motherly love is among the strongest of motivators. If maternal feeling could have driven Margaret to commit infanticide in order to bring her only son to the throne, why couldn’t it have driven Cecily to commit infanticide to keep her last surviving son there?

May 4, 2014

Mary Surratt’s Reconstructed Courtroom

As you know, I’m currently writing a novel about Mary Surratt and one of her boarders, Nora Fitzpatrick. To my delight, the room in which Mary and seven other accused conspirators were tried, located in Grant Hall on the Fort McNair army base, has been reconstructed. Last Saturday, it was open to the public (and will be so again in August, November, and February). This is the courtroom as it appeared in a contemporary sketch:

This is the reconstructed area where the conspirators (who were not allowed to testify) sat during their trial, which was a military rather than a civilian proceeding. A heavily veiled Mary Surratt sat at the far left, a short distance from the seven male defendants–Lewis Powell, David Herold, George Atzerodt, Ned Spangler, Samuel Arnold, Michael O’Laughlen, and Dr. Samuel Mudd–and their guards. One of the tour guides is in front of the chair in the area where Mary would have sat.

These are the tables where the judges and the press sat (press on the left, judges on the right). Witnesses testified while standing in the box.

A sizable audience of spectators (both men and women) squeezed into the courtroom to watch the proceedings. Bear in mind that this was the era of the spittoon and of the hoop skirt, and that temperatures in a Washington, D.C., summer commonly rise into the 90′s, accompanied by high humidity, and you can imagine just how miserable everyone here was.

This is the building in which the courtroom is housed (on the third floor).

The building you see here is what remains of a much larger complex of buildings known as the Old Arsenal Penitentiary. There the eight accused conspirators were held prisoner before, during, and after the trial, which dragged on from mid-May 1865 to late June 1865. If you looked out of these windows on July 7, 1865, as Nora does in my book, this is what you would have seen:

Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt were hanged that day. The other four were sentenced to hard labor and imprisoned at the Dry Tortugas in Florida. They were eventually pardoned and released, except for Michael O’Laughlen, who died of yellow fever there.

This photograph, part of the exhibit inside the courtroom, shows Grant Hall as it appears today superimposed upon the scene of the hanging photographed by Alexander Gardner. Note the modern-day tennis court close to the gallows, which were constructed specially for the executions of the conspirators:

Mary and the four other conspirators were buried on the Arsenal grounds, where the man who had dragged them into trouble in the first place, John Wilkes Booth, had already been secretly buried. Eventually, the families of the dead were allowed to retrieve and rebury the bodies. Mary’s children took her body to Mount Olivet Cemetery in Washington, D.C., where her modest gravestone receives the occasional tribute from a visitor.

April 9, 2014

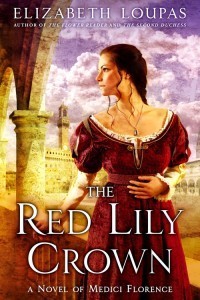

Guest Post by Elizabeth Loupas: Mithridates

I’m pleased to welcome a guest to my blog today: Elizabeth Loupas, whose new novel, The Red Lily Crown: A Novel of Medici Florence, was published this month. Elizabeth’s subject today is mithridates, about which I knew nothing until I read this fascinating post. Over to Elizabeth!

One of the most mysterious and sought-after substances in medieval and Renaissance alchemy was called a mithridate—a universal antidote, which supposedly protected the person who took it from every conceivable kind of poison. Considering the danger of poison in many of the royal and noble courts of the day (up to and including the Vatican), a genuine mithridate was worth a fabulous price.

Was there such a thing?

Well, no, not really—from our twenty-first-century vantage point, we can look back and smile at the thought of our credulous forebears, believing an alchemist’s concoction could protect them from poison. It’s rather like the supposed powers of the unicorn’s horn or the toadstone (neither of which had anything to do with the creature they were named for). But alchemy in the middle ages and the Renaissance was the research science of the day, and there’s a grain of validity in the idea of taking a substance which consists of infinitesimal doses of fifty or sixty different poisons, and thus building up some form of immunity to at least some of them. After all, many of our “miracle drugs” today are poisonous in large enough quantities, and at the same time, the more we take of them, the more we build up a resistance, rendering smaller doses ineffective.

So the idea of a mithridate isn’t entirely mythical.

Why was it called a mithridate?

There was an ancient (134-63 BC) king of Pontus named Mithridates VI, the Great. His father (Mithridates V, of course) was assassinated by poison, so Mithridates VI came up with the idea of making himself immune to poison by regularly taking sub-lethal doses of different poisonous substances. There are different descriptions of his “universal antidote” in ancient literature: in Celsus’ De Medicina (probably written around the time of the Roman Emperor Augustus) it’s called Antidotum Mithridaticum. Here’s his rather astonishing recipe:

“But the most famous antidote is that of Mithridates, which that king is said to have taken daily and by it to have rendered his body safe against danger from poison. It contains costmary 1·66 grams, sweet flag 20 grams, hypericum, gum, sagapenum, acacia juice, Illyrian iris, cardamon, 8 grams each, anise 12 grams, Gallic nard, gentian root and dried rose-leaves, 16 grams each, poppy-tears and parsley, 17 grams each, casia, saxifrage, darnel, long pepper, 20·66 grams each, storax 21 grams, castoreum, frankincense, hypocistis juice, myrrh and opopanax, 24 grams each, malabathrum leaves 24 grams, flower of round rush, turpentine-resin, galbanum, Cretan carrot seeds, 24·66 grams each, nard and opobalsam, 25 grams each, shepherd’s purse 25 grams, rhubarb root 28 grams, saffron, ginger, cinnamon, 29 grams each. These are pounded and taken up in honey. Against poisoning, a piece the size of an almond is given in wine. In other affections an amount corresponding in size to an Egyptian bean is sufficient.”

A lot of these things aren’t actually poisonous—cardamom, anise, saffron, ginger, cinnamon, which sound like a recipe for spice cookies—but presumably they were in the recipe to make the “active ingredients” more palatable.

Pliny the Elder, in his Naturalis Historia (written a few years after De Medicina), does credit Mithridates with originating the idea of taking a tiny dose of poison every day, in order to render oneself immune to poison. On the other hand, he didn’t have much use for the supposed recipes for Mithridates’ antidote:

“The Mithridatic antidote is composed of fifty-four ingredients, no two of them having the same weight, while of some is prescribed one sixtieth part of one denarius. Which of the gods, in the name of Truth, fixed these absurd proportions? No human brain could have been sharp enough. It is plainly a showy parade of the art, and a colossal boast of science.”

Mithridates himself might have agreed, because his own recipe (as quoted by Pliny) appears to have been:

“…two dried walnuts, two figs and twenty leaves of rue were to be pounded together with the addition of a pinch of salt; he who took this fasting would be immune to all poison for that day.”

Which doesn’t sound very effective, unless one expected to be poisoned with rue.

Many classical works were lost and ignored in the early Middle Ages. Not so with Celsus and Pliny—their encyclopedia-like compendia were just practical enough that they were preserved and copied, and incorporated into the arcane literature of alchemy. As the centuries passed alchemists made their formulas for mithridates more complicated, rather than less—this made them more mysterious and, of course, more expensive. Ingredients were often written down in code—the fictional mithridate I created for The Red Lily Crown, called sonnodolce, is composed of ingredients identified by the four colors of the most ancient alchemy texts, black, white, yellow and red.

Eventually mithridates were considered to be a precaution against the plague as well as against poison. They were generally kept in elaborate vessels consistent with their supposed value. Here’s a picture of a sixteenth-century Milanese jar used to hold a mithridate:

http://www.getty.edu/art/gettyguide/artObjectDetails?artobj=1407

I first became intrigued by Mithradates VI when I read A Shropshire Lad, A.E. Housman’s collection of poetry. Shropshire seems worlds and millennia away from ancient Pontus, but in “Terence, This is Stupid Stuff” Housman wrote of Mithridates:

And easy, smiling, seasoned sound,

Sate the king when healths went round.

They put arsenic in his meat

And stared aghast to watch him eat;

They poured strychnine in his cup

And shook to see him drink it up:

They shook, they stared as white’s their shirt:

Them it was their poison hurt.

—I tell the tale that I heard told.

Mithridates, he died old.

The last line still gives me a chill. Mithridates, he died old. Although sadly, Mithridates didn’t exactly die old. When he was finally defeated by his own son, who sided against him with the Romans, legend says that he attempted to kill himself by drinking poison, and found he could not die. Eventually he was dispatched, at his own request, by a Roman officer. True? No one knows for certain.

Whether the intricate alchemical mithridates of the Middle Ages and Renaissance actually saved anyone from poisoning and allowed them to truly “die old,” it’s impossible to say. But the kings and popes and noblemen who paid huge prices for them believed in them. There is some medical merit in the idea of building up a resistance to a drug by taking small, and possibly increasing, doses. So somewhere in history there may indeed be a thwarted poisoner, and an intended victim whose miraculous, expensive mithridate in “a piece the size of an almond” kept him—or her—safe to live another day.

April 1, 2014

New Book Announcement!

I’m sorry I haven’t posted for a while, but I’ve been busily researching/writing my work in progress. I did, however, want to stop by and tell you about a contract I just signed for a new novel, which I have to complete in 2016. Its working title is The Milk of Human Kindness, and here’s the working blurb:

When Cecily, Duchess of York, bears a frail little son, Richard, no one expects him to live more than a few days. But under the loving nourishment of Avice, a young wet nurse, Richard not only survives but thrives. A bond is formed between them that will be broken only with Richard’s death at Bosworth Field.

As Richard grows into a deeply principled man, dismayed by his brother’s corrupt court and the dominance of the greedy Woodvilles, Avice is always there to offer him her unconditional support and love. Richard, in turn, is Avice’s only comfort as her own son drifts into a life of crime. When Richard has to make the most difficult decision of his life–one that will change the course of history–it is Avice to whom he turns for advice.

Told by Avice, The Milk of Human Kindness offers a fresh perspective on Richard III by the woman who loved him best–and who inspired him to create the system of bail that we all enjoy today.

You can pre-order The Milk of Human Kindness at Amazon at the link here.

March 1, 2014

If Anne Boleyn Cared About Queenship, She Should Have Stopped Being Queen

Anne Boleyn, known chiefly as the mother of Elizabeth I

A short while ago, an author of literary mysteries, Lynn Shepherd, devoted a Huffington Post column (titled “If JK Rowling Cares About Writing, She Should Stop Doing It”) to the decidedly peculiar idea that the enormously popular J. K. Rowling should stop writing adult fiction in order to give “other writers, and other writing, room to breathe.” Rowling, Shepherd graciously allowed, could return to writing for children: “By all means keep writing for kids, or for your personal pleasure – I would never deny anyone that – but when it comes to the adult market you’ve had your turn.”

I won’t comment further on this, except to observe that perhaps only a literary novelist, used to receiving accolades from other literary novelists, could have possibly thought that her post would be met with delighted cries of “How witty and clever!” I’ll also observe that Shepherd’s published books, two of which were inspired by Charles Dickens’ Bleak House and Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park, one of which is based on the lives of Percy Bysshe Shelley and his wife Mary Shelley, wouldn’t have been possible if Dickens, Austen, and the Shelleys had thoughtfully stopped writing in order to give other writers room to breathe. No, instead, I’ll ponder this: what if a few historical figures had followed Shepherd’s advice?

1. Richard III

Soon after taking the throne, Richard III, concerned that Richard I and Richard II as well as his brother Edward IV will be overshadowed, decides to step down and let his nephew Edward V be crowned after all. Allowed by his nephew to retire to his northern estates, Richard devotes the rest of his life to sheep farming and dies in relative obscurity. Future generations hopelessly confuse Richard, Duke of Gloucester, with Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, and obsess about Edward V’s very colorful sex life.

2. Anne Boleyn

Having failed to deliver on her promise of a son, and not wishing to overshadow other sixteenth-century women, Anne offers to step aside so that Henry VIII can find another wife. Delighted at her gracious retreat, Henry helps to free Anne’s old beau Henry Percy from his own marriage, allowing Anne to become the new Countess of Northumberland. Anne promptly bears Northumberland twin boys but only gets to gloat for a few days before dying of childbed fever. Jane Seymour, without Anne’s beheading to learn from, spends rather too much time alone with her brother Thomas and dies on the scaffold.

3. Abraham Lincoln

Not wishing to overshadow other Presidents, Lincoln decides not to run for a second term and retires to Springfield, where he accumulates rather too many cats and Mary Todd Lincoln accumulates rather too many bonnets. Salmon Chase, the next President, not only refuses to go to the theater on Good Friday, April 14, but on any other occasion. Unable to find any opportunity to assassinate President Chase (and not wishing to overshadow other assassins), John Wilkes Booth finally gives up his plan and marries Lucy Hale. He lives long enough to play the lead in a silent version of King Lear, but neither this nor any of his other silent films have been preserved.

January 19, 2014

We Have Winners!

The cat-naming committee convened this morning, and, after giving the matter great thought, selected a name:

Rochester!

Several of you thought of this name, so there are multiple winners. Congratulations, Evelyn Dangerfield, Cyndi Williamson, Julia, Jayne Smith, and Libby Hunt! (Some of entries were via e-mail or private message on Facebook, so you won’t see all of them in the comments. None of the comments were published until after the contest ended.)

“Cecilia” by Katy was a very close second, so Katy will also be getting a copy of the published book.

Thanks for entering, everyone! Now to turn to the important question of what Rochester should look like . . .

January 9, 2014

A Night at the Theater with Jane Shore

Everyone is doing great with the cat-naming contest. Keep those entries coming–you have until the fifteenth, after which Kitty shall no longer be nameless!

For those of you who are wondering, I’ll still be dealing with medieval/Tudor topics on this blog, albeit mixed in with topics related to the book I’m currently writing–one set in Civil War America. Today’s post happens to have a foot in both camps.

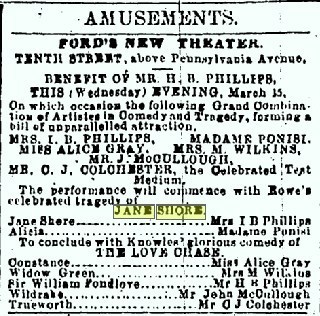

In the winter and spring of 1865, John Wilkes Booth and a handful of his companions were plotting to kidnap President Lincoln. One of those involved in the kidnap plot was young John Surratt, whose mother, Mary, ran a boarding house in Washington. With the idea of kidnapping the president, a frequent theatergoer, as he watched a play, the conspirators decided to scout out the theater by taking in a performance. Accordingly, John Surratt and another plotter, Lewis Powell (staying at the boardinghouse in the guise of a Baptist minister, and using an alias), escorted two of Mrs. Surratt’s boarders, nineteen-year-old Nora Fitzpatrick (whose cat you’re busy naming) and ten-year-old Catholic schoolgirl Mary Apollonia Dean, to Ford’s Theatre on March 15, 1865.

The idea, according to another boarder, Louis Weichmann, had been to take the youngest boarders to the theater, but as the second-youngest girl on the premises was preparing for her first Communion, Nora was chosen in her place. Weichmann, who would be a star government witness at both Mary Surratt’s trial in 1865 and her son’s in 1867, was already in a suspicious frame of mind, having seen John Surratt and Paine at the house that very afternoon surrounded by bowie knives, spurs, and revolvers. He claimed that John Surratt refused to include him in the theater party for what Surratt said were “private reasons.”

The party had a carriage for the short ride from the boardinghouse at H Street between 6th and 7th Streets to the theater at 10th Street. John Surratt had a ten-dollar ticket for a box seat. Although Nora at trial claimed not to be able to remember where the box was located, beyond thinking it was an upper seat, the box may well have been the presidential one, which consisted of two adjoining boxes with the partition between them removed on those occasions when the President decided to take in a play. At some point in the performance, Booth visited the box and had a private talk with the men.

Nora in her testimony was never asked the name of the play the party saw, but thanks to Mary Apollonia, who chatted to Weichmann about her evening at the theater, we know it: Nicholas Rowe’s Jane Shore, first performed in 1714. In fact, as the Washington Evening Star advertisement below shows, the play was part of a double bill of one tragedy and one comedy. No one ever mentions the second play, The Love Chase, which must not have made much of an impression on young Mary Apollonia.

“Jane” Shore (actually named Elizabeth; the first name was the invention of playwright Thomas Heywood), of course, was the mistress of Edward IV. The daughter of John Lambert, a London mercer, she had married a William Shore, another mercer, but the marriage was annulled because of his impotence. Following Edward IV’s death, she was said by Thomas More to have become the mistress of William, Lord Hastings, while Richard III claimed that she was being held in adultery by Thomas Grey, Marquis of Dorset. For reasons which are not entirely clear–most likely her association with Dorset, a wanted man at the time, although More claims that she was accused of plotting with Elizabeth Woodville against Richard–she was jailed at the king’s orders. Later, however, when Richard’s solicitor, Thomas Lynom, fell for her charms, Richard allowed her to leave prison and marry him. Lynom went on to serve the Tudors after Richard’s defeat at Bosworth, and he and Elizabeth had a child or children together. According to More, she was still alive in 1526-27, albeit reduced to poverty. Lynom had died in 1518.

Rowe’s play–described by Rowe himself as a “she-tragedy”–tells a very different version of “Jane’s” story. When the play opens after Edward IV’s death, the evil Duke of Gloucester is chortling over his triumphs over the Woodville faction, and Jane is regretting her fall from virtue and bewailing the sexual double standard:

Mark by what partial justice we are judg’d;

Such is the fate unhappy women find,

And such the curse entail’d upon our kind,

That man, the lawless libertine, may rove,

Free and unquestion’d through the wilds of love;

While woman,—sense and nature’s easy fool,

If poor, weak, woman swerve from virtue’s rule;

If, strongly charm’d, she leave the thorny way,

And in the softer paths of pleasure stray;

Ruin ensues, reproach and endless shame,

And one false step entirely damns her fame;

In vain, with tears the loss she may deplore,

In vain, look back on what she was before;

She sets, like stars that fall, to rise no more.

No “merry mistress” here!

Hoping that he will intercede with Gloucester to restore her land to her, Jane turns to Hastings, who attempts to force himself upon her. She is saved by the intervention of a servant, Dumont, who in fact is Jane’s disguised husband. His boldness toward a social superior earns Dumont a stay in prison. Jane then takes her case directly to Gloucester, who tells her that Hastings opposes his plan to seize the throne. Horrified, Jane praises Hastings for his loyalty to Richard’s nephews and refuses Richard’s demand that she use her wiles to win over Hastings to Richard’s side. Richard then condemns Jane:

Go, some of you, and turn this strumpet forth!

Spurn her into the street; there let her perish,

And rot upon a dunghill. Through the city

See it proclaim’d, that none, on pain of death,

Presume to give her comfort, food, or harbour;

Who ministers the smallest comfort, dies.

Her house, her costly furniture and wealth,

We seize on, for the profit of the state.

Away! Be gone!

Meanwhile, Jane’s false friend Alicia, spurned by Hastings because of his infatuation with Jane, lies to Gloucester that Jane has persuaded Hastings to plot against him. Gloucester, of course, orders Hastings’ execution, but Hastings is given time for a long farewell scene with Alicia, who confesses her guilt and received his forgiveness. Unfortunately, Hastings’ last words for Alicia are a warning for her not to wrong Jane. A bitter Alicia determines to make Jane share her misery.

Actress Sarah Siddons as Jane Shore

Newly released from prison, Dumont/Shore hears from his friend Belmont of Jane’s public penance and destitution and determines to reveal his true identity to her. Meanwhile, Jane, exhausted and famished, seeks shelter from Alicia, who refuses to aid her. Belmont then leads in Shore, who reveals his identity to the fainting Jane and offers her his forgiveness and his protection. Gloucester’s henchmen rush in to arrest the men for aiding Jane, but Shore, realizing Jane is near death, breaks free, allowing Jane to die in his arms. A grieving Shore orders the king’s men:Now execute your tyrant’s will, and lead me

To bonds or death, ’tis equally indifferent.

Belmont is left to expound the moral:

Let those, who view this sad example, know

What fate attends the broken marriage vow;

And teach their children, in succeeding times,

No common vengeance waits upon these crimes,

When such severe repentance could not save

From want, from shame, and an untimely grave.

No doubt Nora and Mary Apollonia took heed, although one suspects that young Mary Apollonia might have been puzzled by some aspects of the story.

After the show, the men escorted their female companions home, and then headed back out again, lingering at the boardinghouse just long enough for Surratt to grab a pack of playing cards. For the ladies, the night had ended; for the men, it was just beginning.

January 2, 2014

Name Nora’s Cat! A Contest

Happy New Year! As promised, it’s time for this blog’s first (and perhaps only) cat-naming contest!

Onslow, clearly thinking very hard about this contest

Here’s the background: one of my heroines in my novel in progress, Nora, is known to have had a cat. We don’t know anything else about the cat, including its name. So I thought for a little fun, I would let my readers have a contest to name the cat. The rules are simple: leave your cat name in a comment or if you prefer, e-mail me privately at mail at susanhigginbotham dot com. You have until January 15 to enter, after which an impartial panel, consisting of my husband and my daughter, will choose the name from an anonymous list I submit to them. The winner gets a mention in the acknowledgments of my novel (working title, The Assassin’s Kiss), a signed copy of the novel, and, of course, his or her choice of name being used in the novel itself. (As I’m still in the early stages of writing, the winner’s gratification will be delayed, but I hope it’ll be worth it.)

A few guidelines:

The cat can be either female or male, depending on the name.

No description of the cat’s appearance exists, so this too can be tailored to the name.

My heroine is a 19-year-old Irish-American Catholic, well educated at Catholic girls’ schools and gently reared.

My heroine is fond of novels, especially those of Charlotte Brontë.

The cat will make its appearance sometime in 1864.

The novel is set in Washington, D.C.

Most of my heroine’s friends and acquaintances sympathize with the South, but it would be inconvenient for the plot for Nora to have a cat with a blatantly pro-Confederate name (e.g., “Stonewall.”)

That’s it! Rest assured that Onslow and Stripes, as well as our dogs, will be cheering you on from the futon.

Stripes, devotedly holding down a box top.

Update: In order to give everyone a fair shake, I will not publish comments until after the contest is over. If the winning name is a duplicate (that is, suggested by several entrants), all will get acknowledgments and books.

December 23, 2013

Merry Christmas, and Happy New Year!

I may be blogging again before the year is out, but just in case I don’t make it and/or you’re too busy to stop by, I wanted to wish all of my blog readers a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. Boswell and Dudley are celebrating in style in their Christmas sweaters, as you can see:

My first nonfiction book, The Woodvilles, is coming out in hardback this January in the United States (it’s already available as an e-book and in printed and electronic form in the United Kingdom).

The historical novel I’m currently working on (working title, The Assassin’s Kiss) is taking me in quite a new direction: it’s set not in medieval or Tudor England, but in 1865 Washington, D.C., and not a single person gets his head chopped off. On the other hand, one heroine ends up on the gallows, while another ends up in an insane asylum. My clever Facebook friends have guessed one heroine, can you? Look for more posts connected with my work in progress in 2014!

After the New Year, I’ll be offering my readers something that I’ve never done before: the chance to name one of my characters. Not a human character, all of whom have been supplied with names by history, but a feline one. The winner will get an acknowledgment in my novel as well as a signed copy. So be thinking of good 19th-century American cat names!

I hope that 2014 is a great year for all of you.

December 13, 2013

Guest Post by Lauren Johnson: Daughter of York: The Life of Anne of York

Some time ago, author Lauren Johnson generously offered to do a guest post about a lady I’ve always found intriguing: Anne, Duchess of Exeter, the oldest sister of Edward IV and Richard III. (In truth, I find her husband, the erratic Henry Holland, Duke of Exeter, intriguing as well, and wish we knew more about him.) Lauren is a historical researcher and is also the author of The Arrow of Sherwood, a novel about the origins of Robin Hood. Check out her website, as well as her Twitter and Facebook accounts.

Without further ado, here’s Lauren!

With the recent confirmation that the body found in a Leicester car park was indeed Richard III this king of the House of York is once again big news. But the woman whose genes passed through more than five centuries of descendants to end up on a DNA stick that identified the bent-spined skeleton has been completely overlooked in the media melée. Through nothing more than genetic good fortune this forgotten noblewoman, Richard III’s elder sister, has become one of the most important figures in recent history of the Wars of the Roses.

But who was Anne of York?

As is so often the case with medieval women, the little we know of Anne’s childhood is all constructed around the men in her life. She was the eldest daughter of Richard, duke of York, and through him inherited the royal blood of Edward III. In 1446, at the grand old age of seven, she married another child with blue blood, her father paying an astonishing 4,500 marks for the privilege. Her husband was the sixteen-year-old Henry Holland, heir to the Duke of Exeter. Even at this early stage, before the ‘Wars of the Roses’ could truly be said to have begun, her father had one eye on the royal succession. Henry VI had been king for 24 years, married for two and there was no sign yet of an heir – nor would there be until 1453. By uniting his daughter to Holland’s Lancastrian claim on the throne (his grandmother was Henry IV’s sister) York set up a potential rival for the accession, should Henry VI die childless.

Whether the marriage was happy in its early days is uncertain. After his father’s death Holland became York’s ward and presumably visited his child wife even if they did not cohabit. However, his youth was blighted by money troubles and his own reckless nature. The wealth he inherited from his father was barely half that expected of a duke, and the twin burdens of a long-lived stepmother clinging onto large chunks of his inheritance and the loss of his French estate in the closing stages of the Hundred Years War, impoverished him still further. The 1450s, when Anne reached an age to live with her husband and presumably become involved in his decisions, was tainted by a prolonged dispute between Holland and the powerful Lord Cromwell, during which Holland allied himself with an enemy of his wife’s family. This was to be the first – but far from last – instance when Anne found herself torn between her own family and her husband’s politics. In 1454, during Henry VI’s madness and York’s protectorate, Holland led an uprising asserting his own claim on the throne. His father-in-law led the efforts to suppress the rising and had Holland imprisoned in Pontefract Castle. Henry VI’s recovery early the following year meant Holland’s release but in the wake of the first battle of St Albans between York’s supporters and his rivals in the King’s Court – presumably now numbering Holland among them – the Duke of Exeter was once more imprisoned in Wallingford Castle in June 1455.

At the outbreak of sustained violence that marked the true commencement of the Wars of the Roses in 1459-61 Holland sided with his Lancastrian kinsman, Henry VI. Anne’s husband fought the forces of her own Yorkist family at the battles of Bloreheath, Northampton, second St Albans and Towton, playing a crucial role in some of the grimmest conflicts on English soil for centuries. At Northampton Anne’s brother, Edward, earl of March, led his army in torrential rain, the water so deep it prevented Henry VI’s forces from using their guns, and of the 300 men killed many drowned in the swollen river as they tried to escape.

The ordeal of Towton was even worse, as the contemporary Crowland Chronicler recorded:

‘They, accordingly, engaged in a most severe conflict, and fighting hand to hand with sword and spear, there was no small slaughter on either side… (The Lancastrian) ranks being now broken and scattered in flight, (the Yorkist) army eagerly pursued them, cutting down the fugitives with their swords, just like so many sheep for the slaughter, made immense havoc among them for a distance of ten miles, as far as the city of York… The blood, too, of the slain, mingling with the snow which at this time covered the whole surface of the earth, afterwards ran down in the furrows and ditches along with the melted snow, in a most shocking manner, for a distance of two or three miles.’

Anne played no part in these battles but as Holland’s wife she would expect to suffer from the consequences of her husband’s activities. When her brother, Edward inherited their father’s royal claim and became Edward IV in 1461 Holland was condemned as a traitor. The law in England was supposed to separate a wife’s property from her husband’s in cases where the husband is ‘attainted’ – stripped of his inheritance – for treason. However, repeatedly the records prove that this ideal was not followed. The most important factor in whether or not a woman suffered the loss of her estates as a result of her husband’s attainder seems to have been her own relationship with the ruling regime, and in this area Anne had an advantage. She had little to tie her to his fate and apparently little concern for his well-being. How long she had distanced herself from him is unclear, but with the victory of the Yorkist cause she severed ties with her loyal Lancastrian husband.

It is known that some women continued to support their rebel husbands during exile from the Yorkist regime, and the government’s stranglehold on certain noblewomen’s finances was intended to impoverish them to such a state that financial aid became impossible. Clearly Anne was suspected of no such marital loyalty. Before 1461 was out the Duchess of Exeter was granted the majority of her husband’s estates. This seriously contravened expected legal practice. The Duke’s lands should have passed to the Crown and Anne should not even have been entitled to the lands she and Holland held jointly, never mind his personal inheritance. A series of amendments to her claims on these estates throughout the 1460s point to the effective termination of Anne and Holland’s relationship, and her determination to provide for herself independently of him. These amendments ensured not only her tenure of the Exeter estate for life, but also the inheritance of her daughter – or, crucially, any further heirs of her body. She had successfully wrestled her husband’s inheritance completely away from his line.

The reason for Anne’s insistence on the rights of her own heirs – presuming they would not also be the heirs of Holland – becomes clearer in 1472. In that year the Duchess of Exeter divorced her husband and swiftly remarried Thomas St Leger. Thomas’s origins are obscure but it would be a reasonable assumption that he had served in her household, the source of many lower status second husbands in this era. The pair had been engaged in a relationship for some time and perhaps Anne waited to divorce Holland because she knew divorce law was heavily weighted against the woman. According to common law she ought to have lost her dower rights – a third of her husband’s estate – when she divorced him. Furthermore, from 1469-71 Edward IV, Anne’s main source of influence, was engaged in another breakout of rebellion, being toppled from power only to return more assertive than ever. With her brother’s restoration Anne could once again evade the legal constraints that hampered most women. She took possession of the entirety of her first husband’s lands, the divorce entirely overlooked. The Duke of Exeter was left so poor that one chronicler reported him ‘begging his pittance from house to house’ in Burgundy, too destitute even to afford hose.

In the arena of her daughter’s marriage – a litmus test for any noble’s political acuity – Anne proved herself sensitive to the winds of political change. Anne the younger was first contracted to the male heir of Richard Neville, earl of Warwick, her powerful ‘king-making’ cousin. However, by 1466 the ascendancy of Anne’s sister-in-law, Queen Elizabeth Wydville meant the termination of the Neville alliance in favour of a new marriage to Wydville’s son, Thomas Grey. Lands were settled jointly on Grey and Young Anne and the Queen paid 4,000 marks for the privilege. Clearly the Duchess of Exeter drove a hard bargain. Warwick’s subsequent rebellion and defeat by Edward IV proved Anne’s change of allegiance had been wise. Unfortunately, the marriage yielded little long-term benefit, for Young Anne died before February 1474.

Anne of York died in January 1476, sixteen weeks after the birth of a daughter with Thomas. This child, also called Anne, inherited the Exeter estate thanks to 15 years of assiduous effort on her mother’s part. In 1481 Thomas St Leger founded a perpetual chantry at Windsor Castle, where his wife was buried, and named it in his late wife’s honour. There, he instructed, prayers were to be offered to the souls of Anne and Thomas, to Anne’s mother and father, to Queen Elizabeth Wydville and to Edward IV. Anne’s loyalty to her own family continued even beyond the grave.

It is somehow fitting that a woman whose life was so embroiled in the decisions and actions of her male relatives should have held the key to the mystery of her brother’s last resting place, and that even now she is still overshadowed by those men. But Anne of York was a remarkable woman. In an age not famed for the freedom of female movement she managed to circumvent inheritance and divorce law, free herself from a dynastic union to marry her lover, and showed considerable political acumen in navigating the pitfalls and reversals of the Wars of the Roses. She proved herself as ruthless and self-serving a magnate as any of the sons of York.

This information was drawn from my thesis, The Impact of the Wars of the Roses on Noblewomen (unpublished Masters thesis, University of Oxford, 2007). The most important sources used regarding Anne were:

Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Edward IV, AD 1461-1467 (London, 1897)

Cockayne, G.E., The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct, or Dormant, 13 volumes, (eds.) V. Gibbs, H.A. Doubleday, D. Warrand, H. de Walden, T. Evelyn Scott-Ellis, G. White, R.S. Lea (London, 1910-1959)

Crawford, A., ‘Victims of Attainder, The Howard and de Vere Women in the Late Fifteenth Century’, Reading Medieval History, XV (1989)

Given-Wilson, C., et al (eds.), The Parliament Rolls of Medieval England. Internet version, at http://www.sd-editions.com/PROME (Scholarly Digital Editions, Leicester, 2005) Accessed, May 2007.

Hall, G.D.G. (ed.), The Treatise on the Laws and Customs of England Commonly Called Glanvill (London, 1965)

Hicks, Michael, ‘Holland, Henry, second duke of Exeter (1430–1475)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article..., accessed 20 Feb 2013]

Pollock, F. & Maitland, F.W. , History of English Law (Cambridge, 1968), 2 Volumes

Power, E. (ed. M. M. Postan), Medieval Women (Cambridge, 1975)

Pronay, N. & Cox, J. (eds.), Crowland Chronicle Continuations: 1459-86 (London, 1986)

Plucknett, T.F.T., Concise History of the Common Law (London, 1956)

Joel T. Rosenthal, ‘Aristocratic Marriage and the English Peerage, 1350-1500: Social Institution and Personal Bond’, Journal of Medieval History, 10 (1984)

Scoble, A.R. (ed.), The Memoirs of Philippe de Commines, lord of Argenton, Volume I (London, 1855)

Strachey, J., Pridden, J., Upham, E. (eds.), Index to the Rolls of Parliament Comprising the Petitions, Pleas and Proceedings of Parliament from Ann. VI Edward I to Ann. XIX Henry VII (AD 1278-AD 1508) (London, 1832)

Ward, J.C., English Noblewomen in the Later Middle Ages (London, 1992)