Susan Higginbotham's Blog: History Refreshed by Susan HIgginbotham, page 7

March 8, 2016

Mary Surratt’s Loyal Daughter: Anna Surratt

The second of John and Mary Surratt’s three children, Elizabeth Susanna Surratt was born on New Year’s Day, 1843, and was christened on December 10 of that year at St. Peter’s Church in Washington, D.C. For most of her life, she would be known simply as “Anna.”

Though married to a non-Catholic, Mary Surratt had been sent to a Catholic boarding school in Alexandria, Virginia, as a girl, and was determined that her children should receive similar educations, a resolve strengthened by the domestic discord caused by her husband’s alcoholism. In an undated letter, she wrote to her former priest, Father Joseph Finotti, to ask if he could help her get her “dear little daughter in school on as cheap a scale as possible without the child feeling any inconvenience from it, as you know dear father it will all have to come through and by my own management.” On January 15, 1855, she was able to report that Anna had been at school for three months at Saint Mary’s Female Institution in Bryantown, Maryland, headed by Miss Winifred Martin, and that the girl was “delighted with her Teachers and improves very fast.” Indeed, Anna made her first appearance in the Washington press in 1855 when a Daily National Intelligencer article detailing the end-of-year awards ceremony mentioned her as the recipient of several medals. Anna remained at school, continuing to win awards, until July 1861, when she returned home at the end of the school year. (Ironically, given the fact that she was later described as a “furious secessionist,” one of the award ceremonies featured her performing “The Star Spangled Banner,” vocally and on piano.)

John Surratt, Sr., died in August 1862. While his death may have been a relief to Mary Surratt, Anna, writing on September 16, 1862, to a school friend named Louise Rule, showed only sadness: “I will not attempt to depict here the anguish the deep grief that almost burst my heavy heart’s Strings when I looked upon my father after death and knew that he could not hear or see me. The suddenness of his death has almost caused me to frown upon the will of a Just God.” Anna asked for a picture of her friend, adding, “I know you do not want mine in such a dismal color as Black.”

Two years later, Mary Surratt decided to lease her tavern in Maryland to a tenant and to move to 541 H Street in Washington, where her husband had acquired a house years before. Anna accompanied her mother, who opened her home to boarders. Mary’s decision was probably motivated chiefly by economics, as she was in debt and Maryland had recently approved a constitution freeing its slaves, but she may have also had Anna’s prospects in mind as well. Though a twenty-one-year-old woman who had not yet married was far from being considered an “old maid,” to use the parlance of the day, it was certainly time to be thinking of marriage, and moving to the city would give Anna the opportunity to meet a variety of eligible men. There was also a dearth of male protectors at the tavern, as Mary’s older son, Isaac, had enlisted in the Confederate army and her younger son, John, was often off on clandestine missions for the South. With coaches bearing strangers stopping at the tavern, Anna would have been vulnerable to sexual predators who might be passing through.

But Mary Surratt’s move to the city proved fatal when John Surratt brought home a visitor, the actor John Wilkes Booth. Anna and a slightly younger boarder, Nora Fitzpatrick, were thrilled by their new acquaintance. Writing to his cousin, Belle Seaman, on February 6, 1865, John indicated that he and Anna were looking forward to attending a party. He added, “I have just taken a peep in the parlor. Would you like to know what I saw there? . . . Anna sitting in corner, dreaming, I expect, of J. W. Booth. Well, who is J. W. Booth? She can answer the question. . . . But hark ! the door-bell rings, and Mr. J. W. Booth is announced. And listen to the scamperings of the —. Such brushing and fixing.”

Louis Weichmann, a school friend of John Surratt’s who had become one of Mary’s boarders, may have had a romantic interest in Anna, although he was preparing for the priesthood, somewhat reluctantly, to fulfill the wishes of his mother. In a letter to Weichmann on February 15, 1865, someone signing herself as “Clara” (probably Clara Pix Ritter), wrote, “I hope you will bring dear Miss S. with you to call on me. I could love her for yr sake & her brother’s . . . I know & feel Miss S_ is worthy of you.” Weichmann’s feelings, assuming that Clara was writing in good faith, were apparently not reciprocated: Weichmann later claimed that Anna had hit him over the head with a brush because he had gone downstairs wearing blue pants. He also told a coworker, Gilbert Raynor, that a young lady at the boardinghouse “had slapped him in the face on account of having a political quarrel with her.”

Anna was sleeping in an attic room with her visiting cousin, Olivia Jenkins, when police arrived in the predawn hours of April 15, 1865, to search the house for suspects in the assassination of President Lincoln. Finding neither Booth nor John Surratt, who was also a suspect, in the house, they departed. At breakfast that morning, Weichmann would later claim, Anna declared that “the death of Lincoln was ‘no worse than that of the meanest n—– in the army. I told her that I thought she would find out differently.”

Assuming that Anna did make this remark, Weichmann would soon be proven right. On the evening of April 17, another group of men arrived at the boardinghouse, this time to take Anna, her mother, Olivia, and Nora into custody. The women were taken to the Carroll Annex of the Old Capital Prison, where Anna would be incarcerated until May 31, 1865. On April 30, she was separated from her mother when Mary was moved to the Old Arsenal Penitentiary, where she would spend the remaining weeks of her life.

The search of Mary’s boardinghouse turned up several suspicious items relating to Anna, including a collection of photographs of Confederate officials and generals, which Anna claimed had been given to her by her father, a framed popular print called “Morning, Noon, and Night” behind which Anna secreted a photograph of John Wilkes Booth, a card bearing the Virginia motto Sic semper tyrannus, and some scribblings on a letter to Anna of her name and Booth’s. Anna claimed that she had hidden the photograph of Booth because her brother was upset that she had it, that she also owned photographs of Union generals, and that the card had been given to her by a lady.

At the conspiracy trial on May 30, Anna testified for her mother’s defense. As the questioning progressed, Anna, who had not seen her mother for a month, became increasingly agitated, looking about and asking, “Where’s Ma?” The government, realizing that nothing would be gained from cross-examining the distraught young woman, allowed her mother’s attorney to lead her off the stand to an adjoining room, where she collapsed. Following her release from prison the next day, she was allowed to sit in the courtroom near her mother, to the evident benefit of both, and to visit with her. On June 20, General John Hartranft, who was in charge of Mary and her fellow defendants, gave Anna permission to stay with Mary, who had fallen ill. Anna would be her mother’s almost constant companion until Mary was hanged on July 7.

Not until July 6 did the condemned prisoners learn they were to die the next day. Anna spent the next twenty-four hours trying to save her mother’s life, visiting the White House twice in an effort to get President Johnson to halt the execution. Her pleas failed, and Anna had to hasten back to the Old Arsenal prison in time to bid her mother farewell. William Doster, who represented Lewis Powell, later claimed that Anna watched her mother’s hanging up until the point the noose was put around Mary’s neck, at which time she fainted; on the other hand, John Brophy, a family friend who had helped Anna in her endeavors to save Mary, said that he had been told not to allow Anna to witness the awful event. From that day on, Anna’s mission would be to give her mother a Christian burial–a goal she would not attain until 1869. Meanwhile, Mary and the three men who were hanged with her were buried at the Arsenal, near the body of the man who had brought them to ruin–John Wilkes Booth.

Orphaned, Anna returned to the house on H Street, which was soon lost to creditors. Her brother John, a suspect in the assassination, had escaped abroad but was finally brought back to face trial in 1867. Many believed he had abandoned his mother to her fate, but Anna remained loyal to John, visiting him in prison and reportedly confiding to a friend, Anna Ward, that “if John were hung, she knew she would die, for then, the last tie that bound her shattered heart to earth, would be broken.” Fortunately for Anna, the jury was unable to agree on a verdict, and John ultimately went free.

On February 3, 1869, Anna wrote to President Johnson, whose White House term was ending, and asked permission to rebury her mother in consecrated ground. President Johnson granted this request (as he did a similar one by John Wilkes Booth’s family). At last, on February 9, 1869, Anna accompanied her mother’s remains to Washington’s Mount Olivet Cemetery, where Mary Surratt was given a proper Catholic burial. Among those at the service were Anna’s older brother, Isaac; John Surratt had gone to South America after his trial and had not yet returned to the country.

The Evening Star reported in February 1867 that before her brother’s trial, Anna had been working as a governess in the home of Captain Gwynn of Prince George’s County. Shortly after the reburial, the Baltimore Sun reported that Anna had moved to that city and taken an examination to work as a teacher in the city’s public schools. Anna’s teaching career was a brief one, however, for on June 16, 1869, Anna married William Tonry, a chemist employed by the government. The two had been keeping company for some time, and William had assisted in the arrangements for Mary Surratt’s reburial.

Both of Anna’s brothers attended the wedding, held in Washington’s St. Patrick’s Church. Father Jacob Walter, who had attended Mary Surratt on the scaffold and presided over her reburial, officiated at this happier occasion. After the wedding, William and Anna, the latter clad in a “light drab traveling dress,” left for a bridal tour in New York.

The honeymoon was short-lived. Soon after the wedding, William Tonry was dismissed from his job, in what many believed was an act of petty retaliation by the government for his marriage to Mary Surratt’s daughter. He rebounded, however, and by 1870 was running his own laboratory in Baltimore, where the couple would spend the rest of their lives. His career prospered, and he testified as an expert witness at a number of trials. A graduate of Georgetown College, he was awarded an honorary doctorate from it. He and Anna had five children, four of whom lived to adulthood and survived their parents.

After her marriage, Anna stayed well out of the public eye, letting her husband speak for her about her mother’s death on the rare occasion when it was necessary. In 1880, a reporter for the Evening Star described Anna as follows: “She is rather tall, and her thin, small pleasant face is plainly marked with lines of severe suffering. She Is easy In her manners, and has a clear, yet subdued voice. Her hair, which was once an auburn color, is slightly streaked with grey.”

By the time Anna died on October 24, 1904, public opinion largely regarded Mary Surratt as the innocent victim of prosecutorial zeal, and Anna was remembered, in the words of the Baltimore American, for her “utmost devotion and self-sacrifice in the closing hours of Mrs. Surratt’s life.” After a funeral at St. Ann’s Catholic Church in Baltimore, she was buried next to her mother at Mount Olivet. A little less than a year later, William Tonry died and was also laid to rest with his wife and mother-in-law at Mount Olivet.

January 29, 2016

The Schoolteacher and the Surratt Family

The failed conspiracy to kidnap President Lincoln in 1865, and the conspiracy to assassinate him which grew out of the first, drew a host of disparate people into their orbit. Among them was a Catholic schoolteacher named Anna F. Ward.

Born in 1834 (according to her death certificate), Anna Ward emigrated with her parents, William and Elizabeth Ward, from Ireland as a child; her sister, Margaret Mary, was born in Baltimore in 1841. By 1860, Anna was working as an assistant teacher at St. Mary’s Female Institute in Bryantown, Maryland, where Mary Surratt’s daughter, Anna Surratt, was a pupil. Left in debt after her husband died in 1862, Mary was in arrears on Anna Surratt’s tuition long after her daughter left school; in 1863, she made a payment to the headmistress through Anna Ward. In 1865, Anna Ward testified that she had known Mary for six to eight years.

Mary and her children moved from their tavern in Prince George’s County, Maryland, to Washington, D.C., in the fall of 1864. Anna Ward had also moved to the city, where she was employed in 1864-65 as a teacher at the Visitation School for Girls at 10th and G Streets. A pupil of Anna’s, Harriet Riddle Davis, described Anna years later as “a tall, angular young woman” with a “stern, even haggard” face and a “restless, nervous way of looking about.” She added that Anna had a “certain breezy energy in her way of teaching that made even the most idle among us know that there could be no trifling.”

When not at her teaching duties, Anna Ward occasionally visted Mary Surratt at her H Street boardinghouse. Anna also was an acquaintance of Mary’s son John, who evidently found the respectable schoolmarm to be a useful cover for his treasonous activities. In December 1864, John Surratt had met the well-known actor John Wilkes Booth, and the men had begun plotting the kidnapping of President Lincoln. In March 1865, it became necessary to find another conspirator, Lewis Powell, a place to stay in Washington, and the Herndon House, a large boardinghouse, was chosen as his residence. Louis Weichmann, a resident of Mary Surratt’s boardinghouse and a friend of John Surratt, testified:

Q. Do you remember having gone with John H. Surratt to the Herndon House for the purpose of renting a room?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. What time was that?

A. It must have been on or about the 19th of March.

Q. For whom did he wish to rent this room?

A. He went to the door, and inquired for Mrs. Mary Murray; and when Mrs. Mary Murray came, he stated that he wished to have a private interview with her. She did not seem to comprehend; and said he, “Perhaps Miss Anna Ward has spoken to you about this room. Did she not speak to you about engaging a room for a delicate gentleman, who was to have his meals sent up to his room?” Then Mrs. Murray recollected: and Mr. Surratt said that he would like to have the room for the following Monday.

Testifying for the defense at the same trial, Anna Ward admitted to inquiring about a room at the Herndon House, but did not know exactly when, other than it could have been February or March. She denied knowing that the room was for a man, and claimed that she did not know who the room was for.

News of the surrender at Appomattox reached Washington on April 10. That day, Harriet Riddle Davis recalled, Anna “came to the school jaded and excited, and after locking the door, got us little children around her and made her, to me, never-forgettable prayer. She prayed for eight lost souls about to be sent into eternity. She prayed for a city about to be plunged into darkness. Meantime the guns around the city were booming out the surrender.”

Anna dismissed her bewildered students. That same day, according to Louis Weichmann, she came to the Surratt boardinghouse bearing a letter from John Surratt, who was then in Canada on business for the dying Confederacy, which he had served as a courier. Anna testified later that during his stay in Canada John Surratt had sent her four letters, two addressed to her and two to be delivered to Mary Surratt. John Wilkes Booth had also stopped by the boardinghouse and, as reported by Weichmann, took an interest in the letter, asking Anna to let him see the address of “that lady” again. “When Booth and Miss Ward had departed, Miss Anna Surratt said, ‘Mr. Weichmann, here is a letter from brother John,’ and I read the letter which Booth had returned to Miss Ward. No lady’s name was mentioned in it.” John Surratt, Weichmann surmised in his memoir, was using Anna “as a tool, and appeared to have adopted the plan of sending his letters in her care instead of forwarding directly to his own home.”

On April 14, Good Friday, Anna Ward brought a second letter from John Surratt to his mother. Its contents, as recalled by Weichmann, were innocent enough: Surratt admired the city of Montreal, mentioned that he had bought a French pea jacket, and complained about the high cost of lodging. Mary Surratt was not home to receive this missive; she had gone to her tavern in Maryland. John Lloyd, her tenant, would later testify that Mary told him to have some guns and whiskey ready for a party who would call for them that evening. That night, John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Lincoln, and Booth duly stopped by the tavern afterward to get the items named by Mary.

Mary Surratt was arrested on April 17. Later, a former slave named Rachel, aka Eliza Hawkins, testified that she went to the boardinghouse on the morning of Tuesday, April 18, to get her young daughter, a servant there, and was told by the soldiers guarding the house that anyone who went there could not come out. She testified that Anna Ward was detained after coming to the boardinghouse that day. Anna’s detention must have been brief, because she was back at her job on May 1, when General Augur ordered two officers to “at once proceed to the convent Cor. of 10th and ‘G’ St. this city and examine the baggage of Miss Annie Ward, Teacher and arrest her.” One can safely guess that having a lay teacher hauled away by soldiers was a novel occurrence at the convent.

Anna was probably not confined for long. Despite the evidence that Anna had helped to secure lodgings for Lewis Powell–who had tried to murder Secretary of State William Seward at the same time Booth was shooting Lincoln–and the fact that she had been the intermediary for letters between John Surratt and his mother, she was not charged with any crime, although the government took the opportunity to cross-examine her about her actions at the conspiracy trial of 1865, where she testified for the defense. Much of her testimony concerned Mary Surratt’s poor eyesight, which her attorneys were using to explain why Mary had not recognized Powell, who had lodged with her, when he turned up at the boardinghouse on April 17. Anna claimed that she knew that Mary was near-sighted because she was too: “[O]n one occasion, something was pointed out to me, and I was laughed at for not seeing it, as it was pretty close by; and she then said she supposed I was something like herself.”

Neither Anna’s testimony nor anyone else’s saved Mary from the gallows. John Surratt, meanwhile, had gone into hiding when he realized he was a suspect in Lincoln’s assassination. Having fled abroad, he was eventually captured and was brought to trial in 1867. Anna was not called by either side to testify, although her name came up at trial on several occasions. She was not entirely hidden from public view that year, however. On September 9, 1867, she wrote a letter to President Johnson, telling him that in February, a man calling himself Mr. Morrison had come to the boardinghouse where she lived and said that he was in possession of information that could acquit John Surratt and wanted a meeting with him. Anna, rightfully wary, advised the man to speak to Surratt’s lawyers, but Morrison persisted in trying to get Anna Ward to introduce him to Anna Surratt. Anna Ward concluded that the man was attempting to implicate President Johnson in the assassination of his predecessor.

After this communication, Anna Ward resumed her quiet life. For years, she worked as a music teacher in Washington. Her widowed father, who died in 1879, willed his house to Anna and her sister (who worked as a Treasury clerk), and the two women lived together at 230 Maryland Avenue N.E. until 28 September 1916, when Anna died at age 82. She was buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery, where Mary Surratt was also buried. Her sister survived until 1925.

Harriet Riddle Davis, who due to Anne’s continued residence in Washington had concealed Anna’s name in giving a speech about her wartime recollections in 1900, wrote an article in 1922 in which she revealed Anna’s identity. Writing that Anna’s prayer had frightened her but that no one at the time had paid her any mind, she added, “It was not till two years later, when John H. Surratt was captured and brought to trial, that my story was recalled, or had any meaning for anybody. The trial was over, the jury was out, and my father [who was involved in the prosecution] feeling much depressed and sure that Surratt would be acquitted, said in my hearing, ‘If we could only have got hold of Anna Ward and put her on the stand we might have forced the truth.’ At the name, I again felt all the old horror, and again repeated my story — It was too late.”

Marker at Mount Olivet for Anna’s parents. Photo courtesy Kathy Wolfe.

Sources:

Harriet Riddle Davis, “Anna Ward’s Prayer: An Unwritten Chapter of the Assassination,” The Magazine of History: With Notes and Queries, 1922.

Harriet Riddle Davis, “Civil War Recollections of a Little Yankee,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. Vol. 44/45 (1942/1943).

William C. Edwards and Edward Steers, Jr., eds., The Lincoln Assassination: The Evidence.

The Papers of Andrew Johnson: September 1867-March 1868.

Ben Perley Poore, ed., The Conspiracy Trial For the Murder of the President, and the Attempt To Overthrow the Government By the Assassination of its Principal Officers.

The Trial of John Surratt.

Laurie Verge, “Who Was Annie Ward?” Surratt Courier, July 2008.

Louis Weichmann, A True History of the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln and of the Conspiracy of 1865.

December 22, 2015

The Christmas Shopping Trip that Never Was

On December 23, 1864, Louis Weichmann left his Washington, D.C., boardinghouse to do some Christmas shopping for gifts for his sisters. Instead, he was waylaid by history.

Weichmann, age twenty-two, was employed in the War Department. In the fall of 1864, a friend and former classmate, John Surratt, told Weichmann that his widowed mother, Mary, was planning to lease her farm and tavern in Prince George’s County, Maryland, and move to Washington, D.C., where her late husband had acquired a house at 541 H Street some years before. She planned to open her house to boarders; would Weichmann like to move in? Weichmann, lonely in his present lodgings, gladly accepted the opportunity to share his friend’s home.

Since leaving school, John Surratt had been helping his mother with her Maryland property. His main occupation, however, had been carrying clandestine messages for the Confederacy, for the Surratts, like most of their neighbors in Prince George’s County, were southern sympathizers. Indeed, the tavern was a “safe house” for those engaged in missions for the South. Still, the Confederate cause looked bleak in December 1864, and according to Weichmann, Mary Surratt had urged her son to get a “real” job. He would begin working for Adams Express Company, the UPS of its day, on December 30.

After dinner at the boardinghouse, Weichmann and John, who shared a room and indeed a bed there (a common sleeping arrangement at the time), set off to take a stroll and to do some Christmas shopping. As they passed by the Odd Fellows’ Hall on Seventh Street, a man called out John Surratt’s name. He was Dr. Samuel Mudd, a doctor who owned a farm in Charles County, Maryland and who had a prior acquaintance with John Surratt. Dr. Mudd too was with a companion: a pale, dark-haired, and strikingly handsome man whose name Weichmann understood as “Mr. Boone.” Had Weichmann been a regular theatergoer, he would have recognized the man as the actor John Wilkes Booth.

The National Hotel (Library of Congress)

The four men exchanged pleasantries, and Booth invited them to his rooms at the National Hotel, where he ordered milk punch and cigars for the quartet. Then, after some idle chit-chat, Booth, Mudd, and Surratt went into the hall, leaving Weichmann to enjoy his cigar in solitude. Soon the three returned, but rather than rejoin Weichmann, they gathered around a table and talked quietly amongst themselves, Dr. Mudd having explained that they were discussing the sale of Dr. Mudd’s farm to Booth. During their conversation, Weichmann, seated alone on a sofa by the window, noted that Booth made some marks on the back of an envelope, which the sharp-eyed Weichmann thought were straight lines. When the trio wrapped up their private conversation, the party adjourned to the Pennsylvania Hotel, where Dr. Mudd, in Washington to do some shopping himself, was staying with a relative. This time, Dr. Mudd and Weichmann chatted together on a settee in the hotel’s public room while Surratt and Booth talked by the fire, the latter amusing Surratt by exhibiting letters and photographs to him.

Around half past ten, the party broke up. Whatever the others had said to each other during their conversation, Weichmann at least was unaware of the cataclysmic effect his new acquaintance would soon have on the nation. For now, all Weichmann knew was that his Christmas shopping would have to wait another day.

Sources:

Benjamin Perley Poore, ed., The Conspiracy Trial for the Murder of the President, and the Attempt to Overthrow the Government by the Assassination of Its Principal Officers.

Edward Steers, Jr., ed., The Trial: The Assassination of President Lincoln and the Trial of the Conspirators.

Robert K. Summer, The Assassin’s Doctor: The Life and Letters of Samuel A. Mudd.

U.S. Government Printing Office, The Trial of John H. Surratt in the Criminal Court for the District of Columbia.

Louis J. Weichmann (Floyd E. Risvold, ed.), A True History of the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln and of the Conspiracy of 1865.

September 23, 2015

Sarah Slater and Her Souvenir Spoons: Her Last Will and Testament

As those who are familiar with the goings-on at Mary Surratt’s boardinghouse know, one of the more intriguing characters to pass through its doors was a veiled lady named Sarah Slater, a courier for the Confederate government who traveled on several occasions with Mary’s son John. Known as the “French lady” because of her excellent command of the language, Sarah frequently made the journey from Richmond to Montreal, where a number of Confederate operatives were stationed and where Sarah could use her linguistic skills to pass herself off as a local.

Although Sarah’s name was brought up frequently during the Lincoln assassination conspiracy trial, she was never imprisoned or called as a witness. During the trial, Connecticut newspapers identified the mysterious veiled lady as the former Sarah Antoinette Gilbert, born on January 12, 1843, at Middletown, Connecticut, and married to a North Carolina-born dancing master, Rowan Slater, but no one else followed up on this scoop at the time, and Sarah remained literally veiled in mystery until 1982, when famed assassination researcher James O. Hall painstakingly traced her history from birth until her disappearance from the scene in 1865.

Nearly thirty years passed until two other researchers, John F. Stanton and Dr. Jeanne Christie, added further details to Sarah Slater’s story. Having settled in New York City, Sarah divorced her husband, Rowan Slater, in 1866. Subsequently, she married a Mr. Long, and then a William W. Spencer, both of whom she survived. She died on June 20, 1920, in the unexotic locale of Poughkeepsie, New York, and was buried in the Poughkeepsie Rural Cemetery beside her mother and her sister.

Sarah left a will, dated April 8, 1920. As wills are a favorite topic of this blog, I thought I’d give you some highlights of Sarah’s–and as a further treat, I’m placing a scanned image of the original, held at the Dutchess County, New York, Courthouse, on my website.

Sarah first provided for headstones for her own grave and for those of her sister and her mother. As you can see here, they were duly erected–but note the discrepancy between the year of birth on the tombstone and that mentioned above. Either the person who gave instructions to the stonemason was confused, the stonemason made a mistake, or Sarah, like many ladies of her time, saw no reason to be strictly truthful about her age.

Next, Sarah (who was childless) distributed some of her personal belongings. To her friend Frank H. Sincerbeaux, she left two vases in French gilt, painted by Jerome. Margaret Derr, who served as Sarah’s executor, received a gold lorgnette and chain. Helen Drummond got a pair of diamond earrings, a gold watch set in diamonds, and all of Sarah’s souvenir spoons. Mrs. James Warring Gilbert was willed a tortoise shell comb with a gold back, a gold thimble, and an old ivory fan. Frances C. Kolla, Sarah’s niece, got a gold chain and locket set with diamonds, a bracelet, and a stickpin with pearls. James W. Gilbert and Joseph W. Gilbert, Sarah’s nephews, received all of Sarah’s pictures, including her photograph albums.

Sarah then left a number of cash bequests: $1,000 to Margaret Derr; $150 to Mrs. Jennie Fellows; $150 to nephew James W. Gilbert; $300 to nephew Joseph W. Gilbert; $150 each to nephews Robert Gilbert and Oliver Gilbert; and $200 to niece Frances C. Kolla. Sarah directed that her clothing be divided between Margaret Derr and Frances Kolla.

The rest of Sarah’s real and personal property (the “residue”, as it is known in legalese) went to Frances Kolla, Joseph Gilbert, and James Gilbert.

The years and the deaths of various family members had left Sarah comfortably off. Sarah owned land in Hudson County, New Jersey, and in Lenoir County, North Carolina; she also held a mortgage on 8659 19th Street in Brooklyn. James W. Gilbert’s attorney claimed that Sarah owned land in Florida as well. In the same document, he listed numerous items of jewelry that Sarah owned, including a diamond locket, an ebony pearl pin, a watch fob with the initial “S”, her third husband’s service pin, cameo pins, watch fobs, and cuff buttons, gold lockets, and a garnet brooch. As for Sarah’s souvenir spoons, although it is pleasant to think of her picking up spoons for her collection as she traveled from place to place carrying her clandestine messages, such spoons did not become popular until the 1890’s.

Sarah did not owe significant debts at her death. The biggest expense was $593.30 for Ida Chatterton, who had attended Sarah for a couple of months during her final illness.

The beneficiaries who were not related to Sarah came from differing walks of life. Frank H. Sincerbeaux, who had a wife and children and who was active in the Boy Scouts, was a Yale-educated lawyer with a handsome home in Forest Hills, Queens. Twenty-year-old Helen Drummond lived with her parents in East Orange, New Jersey; by 1930, she was working as a magazine editor. Thirty-one-year-old Mrs. James W. Gilbert was the wife of Sarah’s nephew James. Mrs. Gilbert, whose first name was Chloe, lived in Hazleton, Pennsylvania with her husband, a salesman for a brokerage firm, and their eight-year-old son. Jennie Fellows (nee Hogan) born around 1859, was the widow of John Albert Fellows, and lived in East Orange. Margaret Derr, who was born around 1865 and lived on 47 E. 21st Street in Manhattan with her husband George Derr, ran a large boardinghouse at that address. As Sarah chose her for her executor, she must have been particularly close to her, or had a high regard for her administrative abilities. What brought Sarah in touch with this diverse group of people is anyone’s guess. Equally unknown is what these friends and her relatives knew of her adventurous past.

Sarah never did take to the lecture circuit or publish her memoirs, and her will gives little sense of a connection between her older and her younger selves. Perhaps, though, in two of the friends she chose to remember in her will–an older woman running her own business and a younger woman about to embark upon a career–we can get a glimpse of the daring rebel who carried secrets from Richmond to Canada.

Sources:

James O. Hall, “The Saga of Sarah Slater.” Reprinted in In Pursuit of: Continuing Research in the Field of the Lincoln Assassination (Surratt Society, 1990).

John F. Stanton, “A Mystery No Longer: The Lady in the Veil.” Surratt Courier, August 2011 and October 2011.

Will and probate file for Sarah A. Spencer, Surrogate’s Court, Dutchess County, NY.

August 16, 2015

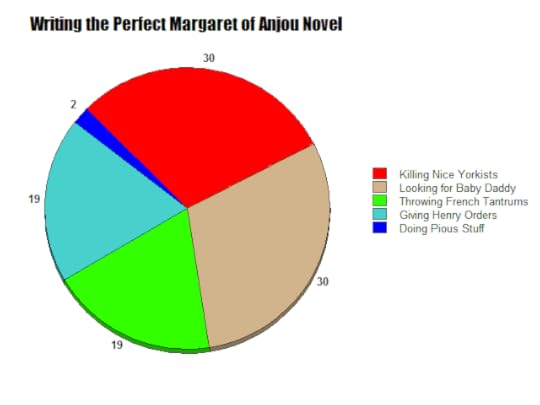

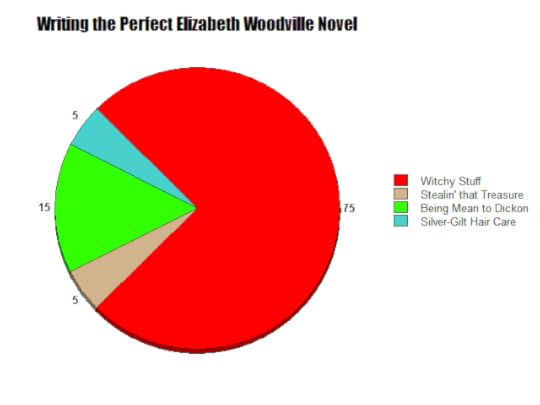

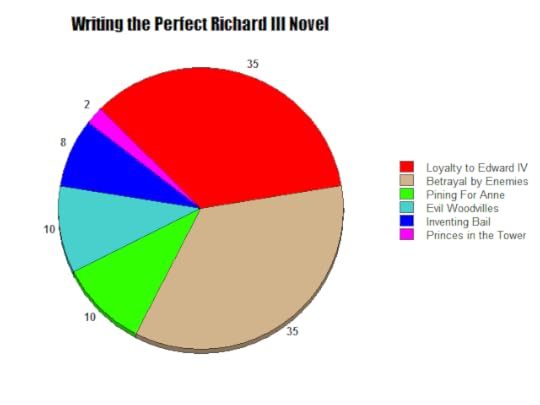

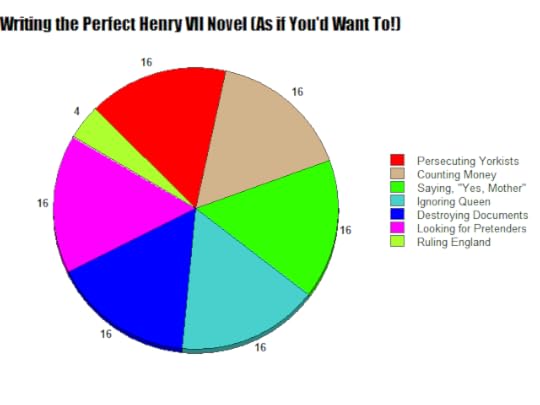

It’s Easy as Pie (Chart) to Write Wars of the Roses/Tudor Fiction!

Inspired by this pie chart about how to write a novel about Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond, I decided to post a few of my own helpful pie charts on my Facebook page. As not everyone hangs out there, I’m putting them here as well (plus a couple of brand-new ones). Just heed the charts carefully, and you too can get a piece of the publishing pie!

Some of my Facebook friends have created their own pie charts, so check them out on my Facebook page!

August 6, 2015

Mary Surratt’s Boarders

In the fall of 1864, Mary Surratt, a widow from Prince George’s County, Maryland, moved to Washington, D.C. and opened her property at 541 H Street (the light-colored house below) to boarders. Mary’s late husband, John, had acquired the house years before as part of a land deal.

So who were the people Mary chose to fill her house on H Street? We’ll save the transients–those who stayed for only a few days, two of whom shared the gallows with Mary–for another time. Here are the seven lodgers who were in Mary’s house for the long term:

Louis Weichmann. Age twenty-two, Louis Weichmann had gone to school with Mary’s son John, and the men had kept up the friendship they formed there. An aspiring priest, Louis had recently got a job as a clerk in the War Department. Finding his lodgings in a large boardinghouse to be lonely, he eagerly accepted John Surratt’s invitation to share John’s bedroom–indeed, his bed, although such sleeping arrangements were common at the time and did not raise eyebrows as they would today. The two men occupied the back bedroom on the house’s third story.

Weichmann’s observations of the goings-on at the Surratt boardinghouse would turn him into a star witness at the conspiracy trial that followed President Lincoln’s assassination. How much he knew of John Surratt’s activities, and how loyal he truly was to the Union, remain hotly debated topics even today.

The events of 1865 ended Weichmann’s aspirations for the priesthood (which may not have been that strong to begin with). He returned to his hometown of Philadelphia, where for many years he held a patronage job with the government until a change of administration cost him his position. His brief marriage to Annie Johnson, a temperance activist, ended in separation. Following the loss of his government job, Weichmann moved to Anderson, Indiana, where some of his siblings were living, and opened a business school. He died in 1902, having left a memoir that was not published until 1975.

Nora Fitzpatrick. Nora, a twenty-year-old fresh out of the convent school of Georgetown Visitation, was a native of Washington, D.C., and the daughter of a widowed bank messenger. As Nora’s father himself was in lodgings, apparently with no suitable quarters for Nora, he placed her with Mary Surratt, probably through a mutual acquaintance. Nora shared a bed with Mary Surratt, who had her bedroom in the back of the house’s second story, and sometimes with Anna Surratt as well, although on the night of the assassination, Anna was sharing an attic room with her visiting cousin.

Along with Anna Surratt, Nora bought a photograph of her exciting new acquaintance, John Wilkes Booth, and kept it in her album, where it would be found by detectives searching the boardinghouse. Along with John Surratt, Lewis Powell, and another boarder, young Mary Apollonia Dean, Nora attended Ford’s Theatre on March 15, 1865, sitting in the same box in which President Lincoln was shot a month later. Booth, who had arranged this visit for Surratt and Powell to familiarize themselves with the layout of the theater in preparation for what was then a kidnapping scheme, stopped by the box.

At the conspiracy trial, Nora testified for both the government and the defense; she reprised her testimony at John Surratt’s trial two years later. She was prominent at Mary Surratt’s reburial in 1869.

In 1870, Nora married Alexander Whelan, a widower with two young daughters, and bore him three sons, but the marriage broke down. So, too, did Nora’s mental health, for in 1885 she was committed by her brother to the Government Hospital for the Insane, now known as St. Elizabeths. Nora died there of tuberculosis in 1896. Her psychiatric diagnosis was “chronic melancholia.” She is buried near her parents in Washington’s Mt. Olivet Cemetery, not very far from Mary Surratt’s grave.

Signature of Nora as a married woman

The Holohan family. John T. Holohan, his wife, Eliza (nee Smith) and their children, Mary Catherine and Charles, moved into the boardinghouse in February 1865. The family occupied two rooms in the front of the third story. According to famed assassination researcher James O. Hall, records show that Eliza once accused her husband of assault. A recollection by one of Mary Surratt’s descendants has it that the couple had just reconciled after a separation before they came to live with Mary.

John Holohan worked as a stonecutter, but in 1865 was also involved in procuring substitutes for those wanting to evade service in the Union army. Business was good enough for him to have plenty of greenbacks on hand when John Surratt, heading up to Canada after the fall of Richmond, needed some gold pieces changed. Along with John Surratt, Louis Weichmann, George Atzerodt, and David Herold, on March 18, 1865, John Holohan attended the play The Apostate, starring John Wilkes Booth, who gave his last performance that evening.

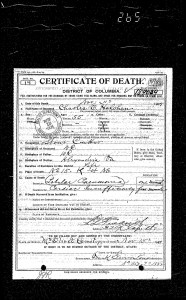

Marriage record for John and Eliza Holohan

Eliza Holohan was friendly with both Mary and Anna, although she testified that she knew Anna better. On the evening of the assassination, she and Mary set out for Good Friday services at church, but the two women turned back home on account of the dreary weather. Booth once sent a telegram to Louis Weichmann, which Mrs. Holohan delivered to him at his office.

Of all of the boarders, Charles Holohan, who was about eleven, left the most insubstantial mark in the record; he may have been the life and soul of the parlor, for all we know, but none of his activities during his stay with Mary Surratt seems to have been recorded. His older sister, Mary Holohan, who was about thirteen in 1865, is known only for what she did not do: she was invited to go to the theater in March, but declined because she was preparing for her First Communion, leaving Nora to take her place.

After the assassination, John Holohan and Weichmann were required by detectives to help search for John Surratt, a journey that ultimately took them to Canada, but the mission failed. Both Mr. and Mrs. Holohan testified at the conspiracy trial. Although Mrs. Holohan moved in with her mother after the assassination, the Holohans returned to the boardinghouse after Mary Surratt’s hanging, apparently in order to help Anna Surratt. The boardinghouse, however, was soon lost to creditors.

John Holohan, then working as a stone cutter, died of cancer on July 3, 1877. Eliza Holohan succumbed to tuberculosis on March 6, 1889; she was employed as a “sewer of books.” Charles Holohan, who had followed his father into the stone-cutting business, died of pneumonia on November 11, 1909. He had married Catherine Culthane in 1885. Mary C. Holohan married Francis Shafer, a printer. The last surviving Surratt boarder, Mary died on February 1, 1927, of a cerebral hemorrhage. All of the family was buried at Mount Olivet.

Mary Apollonia Dean. This splendidly named little girl, a day student at the nearby Visitation School for girls, was about ten when she joined the Surratt household. Her mother, Mary Dean, lived near Alexandria, Virginia, a short distance from Washington.

Where young Mary slept in the boardinghouse is unrecorded. Along with Nora Fitzpatrick, she went to the theater in March 1865 with John Surratt and Lewis Powell. Before the assassination, she left Washington to spend the Easter holiday with her family, and never returned to the boardinghouse. On April 24, 1865, her mother asked the mayor of Washington to help her recover her daughter’s trunk from her H Street lodgings.

On December 19, 1872, in Fairfax County, Virginia, Mary Apollonia Dean married the even more splendidly named Napoleon Bonaparte “Harry” Grant. Then, on February 18, 1894, tragedy struck: Harry, who was employed as an engineer on the Richmond and Danville Railroad, was fatally injured when a freight train and a work train collided near Proffits, Virginia. A widow with two children, Mary Grant received $2,000 from a fraternal organization and $4,000 from her husband’s employer, but she was shattered by her husband’s death. Just three months later, on May 14, 1894, she died. The Alexandria Gazette reported that she had never recovered from the shock her nervous system received from her husband’s death, and that “her death is believed to have been the result of the poignant sorrow and shattered nerves from which she had ever since suffered.” Just a few weeks later, her administrator auctioned off her household goods, which included “two fine parlor sets” and carpets. Husband and wife were buried in Alexandria’s St. Mary’s Catholic Cemetery.

So here they are–seven ordinary, middle-class roomers, all of whom would likely have vanished quietly into obscurity had it not been for the events of April 14, 1865.

July 17, 2015

Two Letters from a Grieving Daughter

Whatever one believes about the guilt or innocence of Mary Surratt, her daughter, Anna, is surely deserving of our sympathy. On July 6, 1865, she had been given the horrifying news that her mother would be executed; the following day, despite Anna’s desperate efforts to beg for her life, the sentence was carried out.

Anna was left not only to grieve, but had to figure out how to salvage a future for herself. Her mother had gone to the gallows heavily in debt; most of the boarders at the H Street townhouse once frequented by John Wilkes Booth had gone elsewhere; and John Lloyd, the tenant who rented the Surratt tavern in southern Maryland, had his own troubles, having been imprisoned and given testimony at the conspiracy trial which revealed him as a hopeless alcoholic. Neither of Anna’s two brothers could help her: Her older brother, Isaac, had been serving with the Confederate army and had yet to make his way home, and her younger brother, John, was a fugitive who himself was in danger of hanging if he were caught. Anna would have to rely on her mother’s relations and family friends to get through the coming months.

Meanwhile, however, Anna had one immediate goal: giving her mother a proper burial. Accordingly, on July 8, 1865, the day after her mother’s death, she roused herself and wrote this letter (held by the Library of Congress):

July 8, 1865

Secretary Stanton

War Department

Secretary,

I make my last appeal to the authorities, that is, that they will allow me to receive the remains of my mother. She lived a Christian life, died a Christian death, and now don’t refuse her a Christian burial. If it be in your power I know you will allow me her body immediately.

Yours Respectfully

Anna Surratt

This favor at your hand will be remembered.

July 8, 1865

Edwin Stanton, Secretary of War, was not inclined to give in to this appeal, however. Mary Surratt had had her sympathizers, and the last thing he wanted was to see them flocking to her grave and giving her the status of a martyr. Only in 1869, when President Johnson at last allowed Anna to bury her mother in a place of her own choosing, would Anna get her wish.

The next day, Anna wrote another letter, this time to General John Hartranft, who had been in charge of the Old Arsenal Prison where Mary Surratt spent her last weeks.

.Washington D.C.

July 9, 1865

Genl. Hartranft

Genl. Hancock told Mr. Holohan [a boarder at the H Street house] that you had some things that belonged to my poor Ma, which, with my consent you would deliver to him. Don’t forget to send the pillow upon which her head rested and her prayer beads, if you can find them–these things are dear to me.

Someone told me that you wrote to the President stating that the prisoner Payne had confessed to you the morning of the Execution that Ma was entirely innocent of the President’s assassination and had no knowledge of it. Moreover, that he did not think that she had any knowledge of the assassination plot, and that you believed that Payne had confessed the truth. I would like to know if you did it because I wish to remember and thank those who did Ma the least act of kindness. I was spurned and treated with the utmost contempt by everyone at the White House.

Remember me to the officers who had charge of Ma and I shall always think kindly of you.

Yours respectfully–

Anna Surratt

On July 16, 1865, General Hartranft, preparing to leave his post, informed General Hancock that he had turned over the effects of the executed prisoners to their relatives. Anna had succeeded in one mission at least.

Sources:

Stanton Papers, Library of Congress

Edward Steers and Harold Holzer, The Lincoln Assassination Conspirators: Their Confinement and Execution as Recorded in the Letterbook of John Frederick Hartranft.

July 7, 2015

July 6-7, 1865

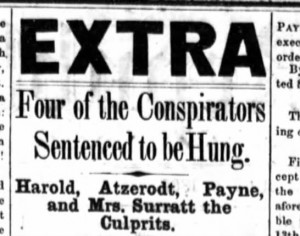

On July 6, 1865, General John F. Hartranft, who had been placed in charge of Washington, D.C.’s Old Arsenal Prison, went from cell to cell, informing Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell (known at the time by his alias of Lewis Payne), George Atzerodt, and David Herold that they had been condemned to die for their roles in the assassination of President Lincoln–and that the executions would take place the following day. (The other four defendants, sentenced to imprisonment, would not learn of their sentences until after the hangings took place.) Soon, the newsboys of Washington began shouting the tidings, and workers at the Old Arsenal began building a scaffold for four.

The condemned were each allowed to ask for clergy to support them in their final hours. Mary Surratt chose two priests: Father Jacob Walter of St. Patrick’s Church, and Father Bernadine Wiget of St. Aloysius’s Church. They hastened to the prison to prepare Mary for her impending death.

In the sweltering summer heat of Washington, Anna Surratt, Mary’s daughter, went to the White House to beg for her mother’s life, but was refused a meeting with the President, who referred her to Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt, who had been the chief prosecutor. Holt referred her back to the President. Frederick Aiken and John Clampitt, the inexperienced attorneys who had been entrusted by senior counsel Reverdy Johnson with most of Mary’s defense, did not learn of their client’s sentence until that afternoon. They telegraphed Reverdy Johnson for advice, and were told to seek a writ of habeas corpus. At 2 a.m. on the morning of July 7, Judge Wylie from the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia, awakened from sleep, signed the writ. For a few hours, it appeared that Mary would cheat the hangman.

On the eve of the hangings, the man appointed to carry out the executions, Captain Christian Rath, fashioned three nooses with seven turns apiece. Wearying of his task, he made only five turns on the fourth noose–that intended for Mary Surratt. Given the likelihood of a pardon due to Mary’s age and sex, he reasoned, it would not be needed.

On the morning of July 7, 1865, Anna Surratt, accompanied by an unnamed female friend, went to the White House to once again beg an audience with the President. Also at the White House were John Brophy, a family friend of the Surratts who was convinced of Mary’s innocence, and Charles Mason, who appears to have no connection to the family but who did not wish to see a woman hang. None were allowed access to the President. John T. Ford, the operator of the theater where Lincoln had been shot, wrote to the President on Mary’s behalf, to no avail.

As Anna and the others waited at the White House, a lady appeared: Adele Douglas, the widow of Senator Stephen Douglas. Pushing her way past the guards, who could hardly stop one of Washington’s grand dames in her tracks, Mrs. Douglas made her way upstairs. No one knows what she said to the President, but he was unmoved by her pleas for Mary Surratt’s life. When the senator’s widow returned downstairs in defeat, John Brophy begged her to try again. She did, with no success. As President Johnson had also suspended the writ of habeas corpus obtained earlier that morning, time and hope were running out.

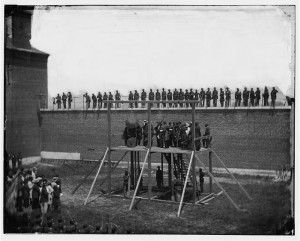

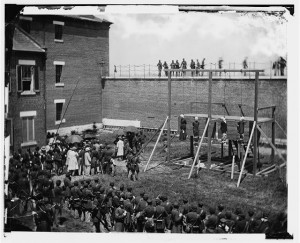

Defeated, Brophy and Anna returned to the Old Arsenal, outside of which vendors were selling cakes and lemonade to those filling the streets near the compound–although only a few possessed the passes that would allow them go inside the prison walls to see the hangings. Anna joined the others who were saying their farewells to the condemned–Herold’s sisters, Atzerodt’s brother and common-law wife, the defendants’ lawyers. None of Powell’s relations was there to bid him good-bye. Powell’s lawyer. learning his client’s identity, had written to his father in Florida, but the letter did not arrive until the day before the executions. Meanwhile, photographer Alexander Gardner stationed his camera in place, ready to capture the hangings for posterity.

At around 1:00 p.m., the four prisoners, escorted by soldiers and accompanied by their spiritual advisors, processed to the newly built scaffold, where four chairs and four nooses awaited them. Mary Surratt, her face veiled, the skirts of her black dress dragging on the ground, led the procession. The prisoners took their seats and listened as their death warrants were read and the clergy offered prayers. Umbrellas were raised to protect Mary and some of the others on the scaffold from the blistering midday sun.

The preliminaries over, the four prisoners were made to stand as they were bound with strips of cloth, then fitted with a noose and a white hood. Lieutenant Colonel William McCall, who had Mary in his charge, carefully removed her veil and bonnet and replaced it with the noose and hood. It was the first time the federal government would hang a woman.

At around 1:25, Captain Rath clapped his hands three times–the signal for the soldiers standing underneath the scaffold to knock out the props which held the scaffold trap doors in place. The four condemned plunged to their deaths. Mary and Atzerodt died almost instantaneously, but the two youngest conspirators, Herold and Powell, struggled for minutes, Powell trying to lift himself into a sitting position. After about seven minutes, even he gave up life.

About twenty minutes later, the defendants were pronounced dead, then cut down. Nearby, their coffins and freshly dug graves awaited them. But theirs were not the first burials at the prison. One corpse already lay in its grave there–that of John Wilkes Booth, the assassin who had brought the four to their deaths.

April 15, 2015

Lincoln Remembered in Washington, D.C.

It’s a beautiful spring evening in Washington, D.C., way too nice to be sitting in a hotel room, but I had a marvelous two days and wanted to talk about them while they were fresh in my mind. (Apologies for the substandard photography.)

When I heard that Ford’s Theatre was planning a round-the-clock tribute from April 14 to April 15 to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Lincoln’s assassination, I was determined to get up to Washington , as I was too young to care about the 100th anniversary and probably won’t be around for the 200th anniversary. So as my husband was kind enough to accommodate me, here I am!

I got excited as soon as I approached my hotel in the afternoon of April 14 and saw two young women in hoop skirts getting out of a taxi. The hotel, which is just a block from Ford’s Theatre, played host to many Civil War reenactors , here to depict some of the witnesses to this most tragic night in American history.

As the crowds began to fill the block of 10th Street on which the theater sits, Ford’s Theatre presented “Now He Belongs to the Ages: A Lincoln Commemoration.” I was one of the lucky ones who had tickets to this event (which was also live-streamed via the Internet). There were many wonderful moments, such as opera diva Alyson Cambridge performing a piece from Faust that Lincoln would have heard during one of his many evenings at Ford’s Theatre, the young actress Lauren Williams reading Julia Taft’s recollection of Lincoln’s relationship with his son Tad, and the cast performing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” but perhaps my favorite part was singer Judy Collins blowing a kiss to the empty presidential box, then inviting the audience to join her in singing “Amazing Grace.”

In the midst of “Old Hundredth,” the Federal City Brass Band fell silent, marking the time at which Booth’s bullet struck Lincoln. We filed downstairs to find the street packed with a crowd holding candles aloft as reenactors playing figures such as actress Laura Keene and actor Harry Hawk recounted the events of the terrible night.

The vigil lasted all night, but I confess to leaving around midnight to catch a few hours’ sleep. At five in the morning, though, I was up to tour the theatre and to see its special exhibit: “Silent Witnesses: Artifacts of the Lincoln Assassination.” For the first time, objects associated with the tragic event—the contents of Lincoln’s coat pocket, his Brooks Brothers greatcoat, Mary Lincoln’s beautiful velvet cape, fragments from the gowns of Mary, her guest Clara Harris, and Laura Keene, Booth’s derringer, and more—were brought together for all to behold.

If you’ve been to Ford’s Theatre, you know that the block it sits on is thoroughly commercialized, with a souvenir store on one corner and a diner known as the Lincoln Waffle Shop. What better place to get a bite to eat after the exhibit than the waffle shop?

I then rejoined the growing crowd in the street. At 7:22 a.m., re-enactor emerged from the Petersen House, where Lincoln was taken to die, to announce the President’s death. There followed a beautiful ceremony where the National Park Service laid a wreath at the Petersen House in memory of the President. Even though this ceremony was taking place during Washington’s rush hour, with cars honking and construction machinery humming, it was if those of us on 10th Street were truly transported back in time for a little while.

With the main part of the ceremony at Ford’s over, I went to the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Spring, Maryland, which has its own collection of artifacts, including the fatal bullet that wreaked so much havoc.

Back in Washington, I went to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, where the barouche that carried President and Mrs. Lincoln is on loan from the Studebaker National Museum.

Finally, I made one last stop at the Newseum, which sits on the site of the National Hotel, where John Wilkes Booth was living at the time of the assassination. There were all the editions of the New York Herald from April 15, 1865, breaking the story of the assassination and adding details (as well as a false report of Booth’s capture) as they became available.

So there ended my Lincoln-related activities for the day. One thing that really struck me was the mix of people I saw who are passionate about Lincoln and about history, like the tattooed young woman in front of me at the theater who showed up in a beautiful Victorian gown, the people crowding around a historian being interviewed as if he were a rock superstar, the woman who brought flowers all the way from Germany for her own tribute to the President, and the many people I saw close to tears this morning. Whatever your historical passion is, I hope that if a similar opportunity comes your way, you will seize it. You won’t regret it.

April 3, 2015

April 3, 1865: Richmond Falls, and John Surratt Departs

One hundred and fifty years ago today, on April 3, 1865, Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the Confederacy, fell to the Union.

The day before, Jefferson Davis and his cabinet had fled the city, having authorized the burning of warehouses and supplies that might prove useful to the approaching Union army. Winds spread the fire, destroying much of the city’s business district. Resident Sallie Putnam wrote, “As the sun rose on Richmond, such a spectacle was presented as can never be forgotten by those who witnessed it. . . . The fire was progressing with fearful rapidity. The roaring, the hissing, and the crackling of the flames were heard above the shouting and confusion of the immense crowd of plunderers who were moving amid the dense smoke like demons, pushing, rioting and swaying with their burdens to make a passage to the open air. From the lower portion of the city, near the river, dense black clouds of smoke arose as a pall of crape to hide the ravages of the devouring flames, which lifted their red tongues and leaped from building to building as if possessed of demoniac instinct, and intent upon wholesale destruction. All the railroad bridges, and Mayo’s Bridge, that crossed the James River and connected with Manchester, on the opposite side, were in flames.”

The electrifying news of Richmond’s fall arrived in Washington, D.C., that same day, sending the federal city into a frenzy of celebration which would gain even more momentum with Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox on April 9. During the heady days from April 3 to April 14, Washingtonians lit up their public and private buildings, held parades, and struck up tunes. The saloons, oyster bars, and music halls were packed.

Not all Washingtonians were in a mood to celebrate, however. In the evening of April 3, John Surratt, who had been acting as a courier for the dying Confederacy, turned up at his mother’s boardinghouse. Having just been in Richmond on a mission, he was stunned to hear that the Confederate government had abandoned the city. He also learned that federal detectives were looking for him, having recently arrested one of his fellow couriers.

In any case, John Surratt had a mission to complete: before Richmond fell, Judah Benjamin, the Confederate Secretary of War, had given him some dispatches to carry to Southern exiles in Montreal. Accordingly, John, having spent a short time at his mother’s house, went out to eat with one of the boarders, his friend Louis Weichmann, then checked into a Washington hotel. The next morning, he left on his journey to Canada, his dispatches safely hidden in a biography of the abolitionist John Brown. He would never see his mother again, and he would not return to Washington again until 1867, when he was brought there as a prisoner to stand trial for his alleged role in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Weichmann would be one of the chief witnesses against him, as he had been at Mary Surratt’s trial in 1865.

Here is a short excerpt from Hanging Mary, as told by Mary Surratt’s boarder Nora Fitzpatrick:

So it came to be that on April 3, 1865, I was sitting by a soldier’s bed, reading to him from Les Misérables (a great favorite among the men), when one of the doctors, a most dignified and reserved man, ran into the ward, threw his hat into the air, and bellowed, “Richmond has fallen!”

There would be no more reading that day.

Some men cheered, and some men cried. Some began to pray, and others just sat in silence, not yet able to grasp the fact that the war at last was nearly at an end. I had been at school when it had started, and I could still remember the nuns gathering us together and praying for a quick end to it. Now, four Aprils later, their prayers were at last being answered.

I slipped out of the hospital and into a city that was going wild. Men were embracing each other in the street; men in uniform were being hoisted up and carried by cheering crowds. Clerks were abandoning their offices; shops were shutting. Who could sit at a desk or stand behind a counter on a day like this? The only people who seemed to be working were the newsboys, and all they had to do was stand still and pocket the money as the extras they held were snatched from their hands. Even if they had tried to shout, they wouldn’t have been heard through the salutes of guns, the ringing of church bells, and the bands that appeared as if out of nowhere to strike up “Yankee Doodle.”

***

I went upstairs and was reading in the parlor, Mr. Rochester purring in my lap, when Mrs. Surratt and her son went into her bedroom.

Presently, Mrs. Surratt emerged. “Nora, dear, do you have some cologne I can use for Johnny? His head is still pounding.”

I nodded and went into the bedroom, where Mr. Surratt was sprawled out on a sofa, looking rather Byronic. My cologne, straight from Paris, had been a Christmas gift from my father. I wore it on special occasions, such as to the theater—and,I confess, on my last few hospital visits to poor Private Flanagan. Once or twice, I had seen him sniff appreciatively.

After I pulled the cologne from my trunk, Mrs. Surratt dabbed some on Mr. Surratt’s temples with her handkerchief. “Try to rest a little, Son,” she said tenderly. “You have been wearing yourself to rags with your travels.”

We left Mr. Surratt alone on the sofa. An hour or so later, he emerged looking much refreshed and bounded upstairs. When he returned, he had Mr. Weichmann, still wearing the blue pants that had so offended Anna, in tow. “Weichmann and I are going for oysters.”

“Why, you just ate,” Anna said.

“Yes, but there’s nothing like destruction and doom to whet a man’s appetite for oysters. Don’t wait up for us, Ma.”