Susan Higginbotham's Blog: History Refreshed by Susan HIgginbotham, page 4

June 18, 2020

The Sister Who Dated Lincoln First: Frances Todd Wallace

In the 1830s, Miss Frances Todd, living with her married

sister Elizabeth Edwards in Springfield, Illinois, went out once or twice with

one of the town’s up-and-coming lawyers, but found him to be insufficiently

social, so the relationship, if it ever amounted to that, fizzled out.

Fortunately, Frances’s younger sister, Mary, was more impressed with the

lawyer, Abraham Lincoln.

The second daughter of Robert Todd and Eliza Parker, Frances

was born on Short Street in Lexington, Kentucky, on March 7, 1817. Little is

known of her as a child, although a cousin, Elizabeth L. Norris, remembered

that she preferred Mary’s company to Frances’s because Frances “was

taciturn, and seemed cold & reserved.”

(Silver spoon belonging to Frances held by the Illinois State Museum. I have not found a verifiable image of Frances.)

In 1825, Eliza died after giving birth to her sixth child to survive infancy, George. Robert Todd remarried in 1826. Mary had a famously fraught relationship with her stepmother, Elizabeth Humphreys, but Frances’s feelings on the matter are unknown.

The oldest of the Todd girls, Elizabeth, married Ninian Edwards, a student at Lexington’s Transylvania College, in 1832. Not long afterward, his father died, and the not-quite-newlyweds moved to Springfield, to which Elizabeth, one by one, invited her unmarried sisters. As the second sister, Frances was first in line to visit the fine Edwards mansion perched on Springfield’s so-called Aristocracy Hill. It was there that Frances, hearing her brother-in-law talk of a Mr. Lincoln, asked Ninian to invite him over. Ninian obliged, but Frances, as she would recall decades later, was not smitten. Mr. Lincoln “was not much for society.” Frances found a more congenial companion in the form of a physician/druggist, Dr. William S. Wallace, a transplant from Pennsylvania whom she married on May 21, 1839. Born August 10, 1802, he was considerably her senior. Elizabeth hosted the wedding–“quite an affair” in Frances’s words. Frances recalled wearing a white satin gown, which she later lent to Mary for a time. The Reverend Charles Dresser conducted the Episcopalian service.

(The Ninian Edwards house. Illinois Digital Library.)

After her grand wedding, Frances moved with her new husband to Springfield’s Globe Tavern. Soon afterward, Mary took her place in the house on Aristocracy Hill, and when Mary married Lincoln in November 1842, the Lincolns would move into the Wallaces’ former lodgings at the tavern. Unlike Frances, the Lincolns insisted on a small, private wedding with little notice, and Elizabeth and Frances had to scramble to get a respectable feast ready. Frances contributed a ham and made the wedding cake.

The Lincolns and the Wallaces were close. Abraham and Mary’s

third son, William Wallace “Willie” Lincoln, was named for Frances’s

husband, and Frances in turn named her eldest surviving daughter Mary. Lincoln

enjoyed stopping by William’s drugstore and swapping stories, and Frances told

William Herndon, Lincoln’s law partner turned biographer, that Lincoln was fond

of the Wallaces’ daughter Mary. Frances often stopped by the Lincolns’ house,

where Lincoln would read “funny things” as well as selections from

Shakespeare. Distressed at the Lincolns’ barren front yard at their home at

Eighth and Jackson Street, Frances planted flowers there.

After Mary’s wedding, a fourth Todd sister, Ann, arrived in

Springfield as a guest of Elizabeth Edwards. She married a merchant, Clark

Smith.

By 1858, Frances and William had five children: Mary, William, Fanny, Edward, and Charles.

After Lincoln was elected President, a “levee” was

held at the Lincoln home on February 5, 1861. Mary played the hostess, with the

help of four of her sisters: Elizabeth,

Frances, Ann, and a half sister from Kentucky, Kitty Todd. A correspondent

wrote, “I thought, when looking

upon the lovely group of the Todd family, how proud old Kentucky would

have felt if she could have been present to witness the position in which her

son and daughters were placed.”

Dr. Wallace accompanied the incoming President on his railroad journey to Washington, but Frances appears to have stayed home. Mary later used her influence to get Dr. Wallace an appointment as a paymaster, a kindness that caused the first known friction between the sisters when Frances, in Mary’s view, proved insufficiently grateful. Writing to her cousin Elizabeth Todd Grimsley on September 29, 1861, Mary grumbled, “Notwithstanding Dr. W– has received his portion, in life, from the Administration, yet Frances always remains quiet. E[lizabeth Edwards] in her letter said—Frances often spoke of Mr. L.’s kindness—in giving him his place. She little knows, what a hard battle, I had for it—and how near, he came getting nothing.” Nonetheless, after Willie Lincoln died in March 1862, Mary was eager to have her namesake, Frances’s daughter, come to Washington to stay with her. Elizabeth Edwards, who had been summoned to Washington after Willie’s death, urged Frances to allow her daughter to come, assuring her that Mary would treat her niece well and that due to the hot Washington summers and Mary’s seclusion, it would not be necessary to assemble a special wardrobe for the visit. Mary Wallace must have accepted the invitation, or a later one, as her obituary described her as having spent time with the First Lady at the White House.

William F. Wallace, Frances’s oldest son, enlisted in the

Union army in February 1864, serving in Company I of the Seventh Illinois

Infantry. Unlike his uncle Abraham, he survived the war. On November 15, 1865, Mary

Wallace wed John P. Baker, whose brother, Edward Baker, had married Elizabeth

Edwards’ daughter Julia.

Dr. Wallace died on May 27, 1867. Two more losses followed:

Frances’s son Charles died of “brain fever” in 1874, at age 15, and

Fanny died of the same malady at age 32 in 1882.

Her husband’s death seems to have left Frances in rather straitened circumstances, about which she was sensitive. When Mary Lincoln, having been released from her short stay at a private asylum, returned to Springfield to live with Elizabeth Edwards, the latter wrote to Robert Lincoln on December 1, 1875, that Mary had bought a shawl and dress to give to Frances as a Christmas gift. Elizabeth informed Robert, “I told her, she would find it difficult to have them accepted, and it proved so. You understand the proud nature of that Aunt.” She added that it was “only in the seasons of her darkest sorrow” that she and Ann had been able to offer substantial financial help to Frances. In 1876, however, Mary succeeded in getting Frances to accept $600 for new carpets for her home.

On August 2, 1876, Mary wrote to Myra Bradwell, a lawyer who

had been instrumental in securing her release from the asylum, that she and

Frances would be leaving for San Francisco the next day. Whether Mary and

Frances actually made this trip is unclear, but by October 1876, Mary was in

Europe, where she remained several years before

returning to Springfield. While abroad,

she continued her generosity to Frances, taking considerable trouble in 1877 to

make certain that a trunk full of woolen goods from France was sent safely to

her needy sister. Frances finally received the trunk in March 1878.

In 1882, Mary Lincoln died in Springfield, leaving three

sisters there: Elizabeth, Ann, and the widowed Frances. The latter, Elizabeth

noted in an undated letter to her half-sister Emily Todd Helm, lived in a

“cozy cottage,” presumably her house

on 1013 South Second Street, to which she had moved after her husband’s

death.

Following Elizabeth’s death in 1888 and Ann’s in 1891,

Frances was the last of Mary’s full sisters still alive. On August 14, 1899,

Frances followed them to the grave. Like her sisters, she was buried in

Springfield’s Oak Ridge Cemetery. Her obituary described her in glowing terms:

“The precept that it is more blessed to give than to receive was

exemplified in her daily life. Her quiet home was a central place for the

entire neighborhood, and young and old alike loved to seek her society. The

delight she felt in the companionship of her neighbors was reciprocated to the

fullest degree.”

Selected Sources:

Stephen Berry, House of Abraham: Lincoln and the Todds, a Family Divided by War

Jason Emerson, Mary Lincoln’s Insanity Case: A Documentary History

Katherine Helm, Mary: Wife of Lincoln

Eugenia Jones Hunt, My Personal Recollections of Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln

Wayne C. Temple, Mrs. Frances Jane (Todd) Wallace Describes Lincoln’s Wedding

Justin G. Turner and Linda Levitt Turner, eds., Mary Todd Lincoln: Her Life and Letters

June 5, 2020

The Other Henry and Clara

(Originally published in The Surratt Courier, a publication of the Surratt Society)

Among its other consequences, Abraham

Lincoln’s assassination would upend the lives of not one, but two young couples

named Henry and Clara. The first—Henry Rathbone and his stepsister/fiancée,

Clara Harris—are well known; the second, Henry Ritter and his new bride, Clara

Pix, are much less so. While April 14, 1865, did not have the devastating

long-term effect upon the Ritters that it would upon the couple who accompanied

the Lincolns to Ford’s Theater, it would earn the newlyweds a stay in Old

Capitol Prison.

Clara

Pix was born around 1838 to Christopher Hodgson Pix and his wife, Matilda Gould,

in Newcastle upon Tyne in the north of England. Soon after that, the family—Christopher,

Matilda, and their three children, Charles, Clara, and Fanny—made the

transatlantic journey to the United States, where a fourth child, Vincent, was

born in the then-Republic of Texas.[1]

The family settled in Galveston, where Christopher Pix worked as a merchant and

later invested in real estate. Galveston’s Pix Building, a three-story brick

building on Postoffice Street, is a reminder of his importance in the city’s

history.[2]

Before

the Civil War broke out, Clara’s brother Charles made a marriage that would

earn him a footnote in Texas history: to Sarah “Sallie” Ridge, a

full-blooded Cherokee. It was her second marriage; the previous one, to George

Washington Paschal, had ended in divorce. Forty-one-year-old Sarah brought a

house and six slaves to the marriage, which took place in 1856 at the home of

former Texas Republic President Mirabeau Lamar; nineteen-year-old Charles is

said to have brought nineteen dollars to it. Sarah traded her house for five

hundred acres at Smith Point, where the couple ran a cattle ranch. By 1880,

however, the marriage had broken down and Sarah sued for divorce. After a

judgment that gave her impecunious husband half the marital property, Sarah,

with the help of her daughter, was able to persuade the judge to allow her to

keep her ranch—a rare outcome at a time when married women had few property

rights.[3]

Charles

and Sarah Pix’s marital troubles were far from being the first in the Pix

family, and by no means would be the last. By 1859, Christopher and Matilda Pix

had separated, and Matilda took her younger children, Clara, Fanny, and

Vincent, up north. At the time of the 1860 census, they were living in

Springfield, Massachusetts, and would spend the next few years flitting between

there, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C., where Clara had an uncle, John

Gould, working as a government clerk. This was almost certainly John A. Gould,

an Englishman who in 1860 was sixty-five and had been living in Washington,

D.C., for decades. While an investigator combing through Gould’s letters five

years later would conclude that Gould was probably a young man, his age is

consistent with Clara’s description of him as having worked for the government

“for many years.”[4]

The 1860 census shows that Gould had a household of young children, so someone

reading his letters might well have assumed that he was a young family man.

At some point, Clara made the acquaintance of two men, Louis Weichmann and John Surratt. (Mary Surratt, who was Weichmann’s landlady and John’s mother, would later hang, convicted of being part of John Wilkes Booth’s conspiracy to assassinate Abraham Lincoln.) Where and how Clara met the men is unknown. Because Weichmann, like John Gould, was a War Department employee, it seems most likely that Clara’s uncle introduced her to Weichmann, who in turn introduced her to John Surratt, who shared a room with Weichmann at Mary Surratt’s boardinghouse. Alternatively, Clara could have met Weichmann, whose family lived in Philadelphia, during her residence in that city, or she could have somehow met John Surratt during his travels to New York on behalf of the Confederacy. Yet another possibility is that Gould, who can be assumed from his burial in Washington’s Mount Olivet Cemetery to have been at least a nominal Catholic, met Weichmann or someone in the Surratt family through church, leading to an introduction to Gould’s niece.

In

any case, Clara seems to have hit it off with both men. Weichmann appears to

have confided to her his romantic interest in his landlady’s pretty,

accomplished daughter, Anna—an awkward state of affairs given the fact that

Weichmann was ostensibly preparing to be ordained as a Catholic priest. For his

part, John Surratt, having apparently discovered that Clara’s political

leanings were with her former state of Texas and the South, likely recruited

her as an agent through which correspondence could be sent under cover.

In

early 1865, however, Clara had other things to occupy her mind besides her

clandestine activities. In the fall or winter of 1864-65, she had started

working as a governess for the Ritter family, and she soon found a suitor in

the person of Henry Theodore Ritter, a young stockbroker. Born on July 27,

1842, Henry was the only surviving son of Dr. Washington T. Ritter, a wealthy

physician, and his wife, Mary Post Ritter. In 1860, he and his two younger

sisters, Catherine and Agnes, were living in their parents’ house in the

Morrisiana section of the Bronx. Two servants attended to the family’s needs.

It was a comfortable home in which to live—and in which to marry into.

Like

many other enthusiastic young men, Henry Ritter had enlisted in the Union army

after the attack on Fort Sumter. Signing up for three months, on April 20,

1861, he joined the 71st New York Infantry.[5]

His unit, Company F, fought in the First Battle of Manassas, an encounter which

Ritter described in vivid detail in a letter to his uncle dated July 23, 1861.

Writing from the safety of the Washington Navy Yard, Ritter recalled:

The Alabama regt. were opposed to us & the Georgia Regt. had attempted to take us in flank but were met by the First Rhode Island. Wheeling to face them during the action I saw one our Regt. fall without his head his canteen falling off him with the sound of water in it. I threw mine away & took his. [6]

Understandably,

after this taste of battle, Ritter, his three months’ enlistment ending on July

30, 1861, was content to return to New York and to his desk job. As the war

dragged to a conclusion, therefore, he was not slogging through fields in the

South but courting the family’s new governess, undeterred by her Southern

proclivities and the fact that she was about four years his senior.

As

the Union veteran and the Confederate sympathizer prepared for their wedding,

Clara wrote a breezy letter on February 15, 1865, to her old friend in

Washington, Louis Weichmann, to inform him that she and “Dr. & Mrs.

R.” would be coming to Washington on February 23 or 24. Requesting that

her impending visit be kept a secret, Clara inquired about her uncle and his

family and added that she and Weichmann would talk over “surprising” her

uncle. She asked Weichmann about a trip he had made to Baltimore in January,

asked why “Mr. S.” had not been to New York or whether he was still

at home, and referred to unexplained “annoyances” that had caused

Weichmann to make a trip to Philadelphia. Clara devoted much of the letter,

however, to hinting none-too-subtly at Weichmann’s interest in a “Miss

S__tt,” writing, “You see I understood your affectionate remark about

Mr. S___tt & the conclusion, ‘I love him, indeed I do, & his ___ too.

‘” Insisting that she could love “dear Miss S.,” undoubtedly

Anna Surratt, “for yr sake & her brother’s; two of my best kindest,

and most sincere W.C. Friends,” Clara suggested that he bring Anna to call

upon her. Rather dramatically, she added, “The distance that will separate

us after our possible interview on the ’23rd’ or ’24th’ will be far greater

than ever . . . we shall no longer be able to correspond, though the ties of

friendship will ever remain unchanged.”[7]

The

“Clara letter,” as assassination researchers call it, has proved a

bit of a red herring. While Elizabeth Steger Trindall, a proponent of the

theory that Mary Surratt was wrongfully convicted, identified Clara Pix as the

author of the letter early on, and saw nothing in it other than corroboration

of Weichmann’s purported interest in Anna Surratt, others have found in it

something more sinister. Michael W. Kauffman, who suggested that the letter was

penned by the Confederate courier Sarah Slater, regarded it as a deeply

compromising document that could have destroyed Weichmann as a defense witness:

“Certainly ‘Clara’ was privy to some personal secrets, such as Weichmann’s

bisexuality and his unrequited love for Anna Surratt. More to the point,

though, she was a Confederate insider, and her letter strongly implies that the

prosecution’s star witness was one as well.” William C. Edwards and Edward

Steers, Jr., wrote, “The letter reads like a loosely coded message dealing

with John Surratt.”[8]

Yet given the tendency of nineteenth-century men to express their feelings for

their male friends more floridly than would be conventional among heterosexual men

today, it seems an enormous stretch of the imagination to see in the letter a

hint of bisexuality on Weichmann’s part, and his romantic interest in Anna

Surratt could have been used by the government to cast him sympathetically as a

reluctant witness just as it could have been used by the defense to cast him as

a vengeful one. While Clara’s interest in John Surratt’s whereabouts could

certainly connect her with John’s covert activities, nothing in the letter

suggests that Weichmann knew more about his comings and goings than would be

expected of Surratt’s close friend and roommate. Finally, the coy hints and

references in the letter all make perfect sense when one considers what was to

take place shortly: Clara’s marriage to Henry Ritter, which was evidently to be

kept secret from her uncle and perhaps other members of her family until she

and Henry’s parents, Dr. and Mrs. Ritter, arrived in Washington. The

“distance” that would separate Clara from Weichmann after February 23

or 24 was presumably the impropriety of a newly married woman continuing to

write to a bachelor friend.

On

February 20, 1865, Clara and Henry married at Manhattan’s Church of the

Ascension, in a service officiated by Rev. J. Cotton Smith.[9]

Whether they traveled to Washington afterward, much less had the promised

meeting with the hapless Weichmann, is unknown, but their honeymoon,

figuratively speaking, would be brief. In a mere matter of weeks, the newlyweds

would find themselves in a heap of trouble.

Following

President Lincoln’s assassination, John Surratt, learning that he was a

suspect, fled to Canada, pursued by Washington detectives and a reluctant Louis

Weichmann. In Montreal, Officer James McDevitt intercepted a letter requesting

someone at St. Lawrence Hall, a hotel popular with the Confederate underground,

to forward any correspondence addressed to John Harrison to a Captain Navarro

of New York City. “John Harrison” was the alias of John Surratt, and

the name he had used to register when he checked into the hotel on April 18. Upon

returning to the United States without John Surratt, McDevitt handed the matter

of the mysterious Navarro to Officer G. Walling of the New York Police

Department.[10]

On

May 3, an excited Walling wrote to McDevitt to inform him that a couple had

come to the New York post office inquiring for letters to Navarro. When the

clerk said there were none, and that in any case an order would be required for

a third party to receive the letter, the lady explained that Captain Navarro

was dead and that she wished to forward his letters to his widow. The man,

giving a card identifying himself as H. T. Ritter, then requested that any

letters be sent to his office, and the couple left. Tailed by a clerk, the pair

walked to Ritter’s office at 80 Beaver Street, where, Walling reported,

“They parted . . . and the clerk tried to pipe her off but she beat

him.” Walling recommended the couple’s arrest. The matter passed to D. R.

P. Bigley, who on May 6, 1865, wrote to Lafayette Baker at the War Department.

Presently, Major General John A. Dix ordered that the Ritters be brought in for

questioning, a task that fell to Major Charles O. Joline.

Joline

found Henry Ritter to be cooperative. He readily declared that Clara had told

him that her mother, Matilda Pix of Philadelphia, had asked her to call for

letters to Captain Navarro and that he had come along, leaving his business

card under the circumstances described above. Clara, called in afterward, was

another matter, as Joline wrote: “I found it very difficult indeed to get

any answers or explanations from her which appeared at all reasonable or coherent.”

Clara stated that around April 3 or 4, a lady, signing herself “Navarro” and claiming to be the mother of the deceased Captain Navarro, had written to her in Philadelphia, addressing her by her maiden name, and asked her to call for letters to Captain Navarro, to be delivered to the captain’s widow, but had not told her where she was to send the letters. Someone, perhaps Clara’s mother, had forwarded the letter to Clara, who had waited a month before calling for the letters, due to the distance of the post office, the bad weather, and a spell of ill health. Asked by Joline why someone from Philadelphia would want her to get letters from New York, Clara responded that she had been given instructions to call for letters at both cities, presumably because she had formerly traveled between them very frequently. She stated that she did not know either a Captain nor a Mrs. Navarro, but thought that the captain was a Union officer. At about that point Henry, good citizen that he was, piped up to remind his bride that she had sent a newspaper to a Eugene Navarro. Clara then admitted to sending Navarro a newspaper, but said that she did not know him but had been told by a person whose name she could not recall that Navarro was a prisoner at Johnson’s Island in Ohio and that she had sent the paper because he was a fellow Texan. When Joline suggested that Navarro might have escaped and written to her himself, Clara exclaimed that he “was too good a Christian to do that.” Asked how she knew that this stranger was a Christian, Clara said that in Washington City, she had been told that he had sent for sermons, tracts, and newspapers. She had not heard this through her uncle, John Gould, but thought someone in the Lincoln Hospital in Washington had told her about Navarro’s reading tastes.

An

exasperated Joline wrote, “Not the least remarkable part of the statement

is the fact stated by her that she received a letter of the king mentioned,

from one stranger to another, about the letters of another stranger to be

called for in two cities & that she did not show the letter to her husband,

or tell him that she had received it; that she kept it a month before she

called for letters as directed; & that she did not request her husband who

passes the Post Office at least twice a day to call for them for her.”

Adding that Henry had not heard of Clara’s wish to call for the letters until

the pair were riding an omnibus downtown the morning of May 3, Joline concluded

that Henry was innocent of all involvement in the matter.

While

Joline sat writing his report on May 14, Officer Bigley paid a call, bearing

the news that while he had been guarding the Ritter residence, Clara had at last

admitted, under urging from Henry, that it was she who had written the letter

to Canada instructing that John Harrison’s letters be sent to Captain Navarro.

Better yet, Clara confessed to knowing John Harrison and to knowing that he was

John Surratt. With that, the couple soon found themselves bound for Old Capitol

Prison in Washington, Clara as a prisoner “for holding communication with

Surratt and acting as his agent” and Henry, whom Major Gen. John A. Dix

believed to be “entirely innocent,” as a witness.[11]

Committed

to prison on May 15, Clara was questioned again. An unsigned memorandum by her

interrogator, hidden in the depths of the National Archives until it was

discovered by Arnold Lee Gladwin in 1937,[12]

reads as follows:

May 15, 1865

Memorandum: Mrs. Henry T. Ritter of New York. Formerly Miss Clara Pix probably of Texas. Appears to have come north before the War. Resided in Washington, Philadelphia & Springfield Mass. Went to New York last fall or winter as governess in family of Dr. Wm. Ritter and married a relative of his Feb. 20 1865. Letters written by herself to parties South but not sent for want of opportunity show that she is a thorough rebel but contain nothing to criminate further herself or anyone else. Pieces of rebel poetry, printed & manuscript show the same thing.

A number of letters from John Gould of Wash[ington], who signs himself her uncle; apparently a young man & occupying some situation under Govmt. Application from Gould to Adj. Genl Thomas, dated Ord. Office June 30 1862 request to be transferred from Or. to A.G. Dept. In one of Gould’s letters dated Aug. 20 64 he speaks of having returned to his desk and being embarrassed by the clerks inquiring after his niece & how he liked Phil[adelphia]. He says he had to cut their questions short to avoid telling “fibs” and “in fact I could not give any account of a place I never was at.” Among friends of her mentioned by Gould is a Mr. Weichmann. A letter of Mrs. R. directs her correspondent to address her under cover to Major John Gould, who she says occupies the same position she once filled, and expects her correspondent to understand that as she does not wish to say what the position is. During her stay in Wash. she was connected with Rev. D. Hall’s church & has a letter of introduction from D. H. S. Rev. W. McKnight of Springfield Mass dated Dec. 19, 1860. Her family appears to have been in very straitened circumstances.[13]

Henry,

meanwhile, took the opportunity to write a note to Clara, which was apparently

intercepted, as it was found with the memorandum of her interrogation. It reads

simply, “Clara, I love you. Do you me. Henry T. Ritter.”[14]

In

the event, Clara’s penchant for rebel poetry and her helpfulness to John

Surratt were not enough to merit additional attention from the Government. She

was released on May 16, with her husband giving his assurances that he would do

all in his power to prevent her from holding further communications with rebels

or their sympathizers and that Clara’s conduct to the United States government

would be good.[15]

Nothing further is heard of Clara in association with the assassination or with

John Surratt; she did not appear at either the conspiracy trial or John

Surratt’s trial, and Louis Weichmann’s posthumously published memoir has

nothing to say of his old friend.

Back

in New York, Henry and Clara settled back into normalcy and in due time had two

children: Washington Ritter, born on November 7, 1866, and Agnes, born on March

6, 1868.[16]

In 1870, the United States census shows them living together in Morrisania

along with an Irish servant. But all was not well in the Ritter house. In

November 1873, or perhaps 1874, Henry and Clara went their separate ways.[17]

All

we know of the couple’s breakup comes from the divorce case filed by Henry in

the Superior Court of Cook County, Illinois, in March 1880, alleging desertion.

As Clara did not respond, we have only Henry’s side of the story. At any rate,

Henry, who stated that he had been residing in Chicago since January 1, 1879,

and was employed as a clerk in the produce exchange, claimed that he was in the

habit of leaving his house for three or four days and that when he returned

from one such trip, he found that his furniture had been sold, the house closed,

and his wife “cleared out.” A witness, Walter Chisholm of New York

City, indicated that this happened in November 1873 or 1874. Henry Nason of

Montclair, New Jersey, recalled that the desertion occurred in November 1873.

He added that Clara had deserted her two children as well, leaving them in the

care of a justice of the peace. Henry Ritter testified that he had had no

communication with Clara since and that he had received no reply to letters

written to Clara, in places where he supposed she might be found, and to her

brothers. He stated that he was supporting his children, who were living with

his mother.

The

divorce was granted on May 22, 1880. Free to remarry, Henry wasted no time in

doing so; by the time the census taker arrived in June, Henry was back in New

York City, boarding on Tenth Avenue with a second wife, Mary Lewis. A decidedly

hands-off father, Henry left his two children in the care of his sister,

Catharine Appleton, and her husband, William, at their residence at Franklin

Avenue in the Bronx. Henry and his second bride were not childless for long,

however: their son, Henry Ludlow Ritter, was born in Manhattan on March 26,

1881.[18]

As

for Clara, ironically enough given her supposed desertion of her children, the Galveston Daily News would later credit

her with founding the city’s orphanage. Around 1879, the paper explained, Clara

began caring for orphans in her home, an endeavor that attracted the notice of

prominent citizens, who began raising funds for a permanent orphans’ home.

Clara was selected as matron of the institution on July 1, 1880.[19] Indeed,

the city directory for 1881-82 lists the “widowed” Clara as the

matron of Galveston’s Island City Orphan’s Home, located at 17th street and

Avenue F.[20]

After that, however, Clara disappears from the city directory until 1888-89,

when she is listed as residing with Charles S. Pix.[21]

She seems to have lived a peripatetic existence: in 1890, a family acquaintance

told a newspaper reporter that she summered at Newburgh and Port Jervis in New

York and wintered at Wilmington, North Carolina, as well as Galveston. The

reporter was also informed that Clara was receiving $1,800 per year in alimony

from Henry Ritter.[22]

How

much contact Clara had her with her children after she and her husband parted

ways is unknown, but in 1890, there would be a family reunion of sorts when her

son, Washington T. Ritter, paid a visit to Galveston. Unfortunately, the

circumstances were less than ideal.

Like

his father, Washington worked in the financial sector. On February 9, 1887, at

age twenty, he had married seventeen-year-old Mary Florence Johnson, evidently

with a sense of urgency, as their eldest son was born a few weeks later.[23]

Two more children soon followed. Although family photographs posted on the

Ancestry site show Mary to have been a pretty, slender young woman, Washington

was not cut out for a life of quiet domesticity.

On September 27, 1890, the New York Herald proclaimed the perfidy of Young Ritter Thief and Wife Deserter. Washington Ritter, it turned out, had not only embezzled from his employer, he had taken off with a young lady named Mamie Zaun, a twenty-year-old blonde of “Teutonic lineage” whose parents lived on 26th Street. Needless to say, this tale involving sex, money, and an upper-class gent proved irresistible to the New York papers, and was picked up nationally. The Herald’s reporter trooped around the New York metropolitan area, interviewing the wronged wife and her mother, Washington’s business associates, Mamie’s parents, and Henry Ritter. Depending on who told the story, either Mamie had corrupted Washington, or Washington had corrupted Mamie; in any case, Washington had moved his wife and children to a humble abode in Yonkers, New York, and shacked up with Mamie. An avid yachtsman, Washington on the eve of his disappearance had told his friends that he was going to take the train to Stamford, Connecticut, and board his yacht (aptly named the Restless), which had awaited his arrival to no avail.[24]

Henry

Ritter took all of this excitement with aristocratic detachment. Professing to

be surprised by these goings-on, he told the Herald reporter, “I have been

learning a good deal about my son in the last few months, but you know a good

deal more about him than I. I really saw Washington very seldom.”

Mrs.

Johnson, Washington’s mother, predicted that Washington and his paramour had

fled to Galveston, and this suspicion proved correct: the couple was arrested

while strolling down Church Street. They had been staying with Charles Pix, Clara’s

brother, whose divorce from Sarah Ridge, amid accusations of infidelity on his

part, likely gave him a certain sympathy for his nephew’s plight. With Mamie

dramatically asserting she would stand by Washington, the couple agreed to

return to New York, where Washington was locked up in the Tombs, New York

City’s jail.

What

Clara, Washington’s mother, thought of all this is unrecorded. According to

Mary Florence Ritter, Washington’s estranged wife, Washington had introduced

Mamie to Clara as his wife during his brief sojourn in Galveston, but no

reporter appears to have succeeded in interviewing Clara.

Although

Mary Florence Ritter was unforgiving—the final straw seems to have been her

discovery that Henry Ritter had two fine portraits on his wall of Washington

and Mamie despite having professed to know little about his son—Lady Justice was

more sympathetic. In November 1890, Washington was allowed to plead guilty to

grand larceny for the theft of $100. After a witness from the stock exchange

testified that his character had been unblemished until he met Mamie, and his

former employer testified that his uncle had agreed to give him employment,

Washington was given a suspended sentence and released. He obediently moved to

Galveston, while Mamie appears to have vanished into obscurity.[25] In

Texas, Washington worked with his uncle Charles Pix and, rather endearingly,

served as vice president for the local chapter of the American Society for the

Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. He died young, of an abscess of the liver, on

November 12, 1896. His tombstone in Galveston’s New City Cemetery, bears an

anchor, presumably a tribute to his prowess as a yachtsman.[26]

Earlier

in 1896, Clara’s father had died in London, having gotten into the habit of

spending his summers in England. He was 84, which had not deterred him from

remarrying the year before his death. Whether he and Clara were close is

unknown, but her son’s death, at least, would have ended the year on a dismal

note for her. She is reported to have been living in Washington, D.C., at the

time her father died; one wonders if she ever looked up her old acquaintances

John Surratt and Anna Surratt Tonry, both of whom were married and living in

Baltimore.[27]

Four

years later, Galveston—at that time Texas’s leading city—was devastated by the

hurricane of 1900.[28]

Whether Clara was present for the disaster, which killed anywhere from 6,000 to

12,000 people, is unknown, but her brother Charles was among the thousands

killed.[29]

Clara had stayed with Charles at times—the 1898 Galveston city directory, the

last in which Clara appears before 1900, shows them each living at 1528 Avenue

M—and he had helped her wayward son, so Clara must have keenly felt the loss.[30]

Back

in New York, Henry Ritter was having his own difficulties. His second marriage,

to Mary Lewis, had not been a success, and the couple had separated. When Mary died

in 1892, her son by Henry Ritter, Henry Ludlow Ritter (whom we may call by his

nickname of “Harry” to minimize confusion), inherited her estate. He did

not move in with his father, but stayed with the Van Orden family, who were

cousins, and with guardians.[31]

As an adult, he worked for a few months as a bookkeeper, but his health broke

down, and he died of consumption on August 27, 1900, only nineteen years of

age. He appeared to be on friendly terms with his father and the latter’s third

wife, whom he visited occasionally at their Bronx residence. Thus, Henry Ritter

was in for a surprise when he became aware of his son’s will:

After all my lawful debts are paid I give, devise and bequeath unto my dear friend Martina Wilkins Van Orden, all my property of whatsoever kind and wheresoever situated and by whomsoever held of which I may die possessed in consideration of and compensation for the kind unselfish care and attention she has bestowed upon me during all the years since my mother died and previous thereto, I have left my property as above, remembering the fact that my father would be my natural representative, but he has done nothing for my support since my mother’s death and his efforts have been directed to my detriment rather than to my benefit during these years.

A

maiden lady some years Harry’s senior, Martina, or “Tina” as Harry

called her, wasted no time in probating the will, the contents of which were

soon made public.[32]

But Henry Ritter was not one to take this dying insult, and the loss of Harry’s

tidy estate of between $5,000 and $5,500, quietly. He contested the will. Soon

the story of Henry Ritter’s disinheritance at the hands of his own son made the

out-of-town papers. (One wonders if Clara saw the stories.) One of the

witnesses in the court proceedings was Henry and Clara’s widowed daughter,

Agnes Deady, who testified to Harry’s friendly relationship with his father. But

Henry lost the will contest, and the decision was affirmed on appeal. He may

have needed the money; the 1900 federal census indicates that he was working as

a clerk for the health department. In the 1905 state census, he is listed as a

“disinfector.”

Although

Henry’s third wife, the former Mary Adelaide Cook, was considerably his junior,

she died in July 1905 at age forty-one. For once, Henry Ritter had no successor

waiting in the wings. Instead of remarrying, he entered the New York State

Soldiers and Sailors Home in Bath in June 1906. Opened on Christmas Day of

1878, the home boasted a bowling alley and operated its own farm, although

Henry was probably not in good enough shape to either bowl or farm. He was

suffering from failing eyesight, a left inguinal hernia, heart and kidney

disease, and rheumatism. Henry, who had been receiving a pension for his brief

Civil War service, attributed the hernia to an injury he had received when jumping

across a brook during Bull Run.[33]

On

April 17, 1908, Henry died at the home in Bath. He was buried in its cemetery.

As

for Clara, little can be gleaned about her last years. She appears regularly in

Galveston city directories from 1906 onward, suggesting that she was spending

most of her time in that island city. Clara lived at several addresses in Galveston,

finally settling at 1114 M 1/2 Street, where she died of “old age

senility” on January 23, 1924. Like her only son, she was buried at New

City Cemetery, far from where her married life began in Manhattan.[34] The

hapless newlyweds who had been caught up in a conspiracy had long lived

separate lives, but perhaps in their last years, each reflected on those

strange days in 1865.

[1] Texas State

Board of Health, death certificate for Clara Pix Ritter; 1850 U.S. census; obituary for Christopher S. Pix

in the Galveston Daily News, June 28,

1896; https://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marke....

[2]

https://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marke...

[3] Bayton Sun, July 21, 1985;

http://www.houstontimeportal.net/thal....

[4] District of

Columbia Board of Health, death certificate of John A. Gould; Union Provost Marshal’s

File, 1861-1867, War Department Collection of Confederate Records, Record Group

109, Entry 465, National Archives, Washington, D.C.; William C. Edwards and Edward

Steers, Jr., The Lincoln Assassination:

The Evidence (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2009), pp.

1105-06.

[5] Record for

Henry T. Ritter in Ancestry.com. U.S. National Homes for Disabled Volunteer

Soldiers, 1866-1938 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations

Inc, 2007.

[6] Transcription

by National Park Service Ranger Chris Bryce found at

http://nps-vip.net/history/letters/ri.... While the website refers to

Henry “F.” Ritter, this appears to be a misreading, as Henry T.

Ritter was the only person by that name in Company F at that time.

[7] Edwards and

Steers, pp. 1329-30. The editors state that the letter was found among Booth’s

papers at the National Hotel rather than among Weichmann’s papers, but the

basis for this statement is unclear. Id.

at p. 1329 n.1.

[8] Elizabeth

Steger Trindall, Mary Surratt: An American Tragedy (Gretna, LA: Pelican

Publishing Company, Inc., 1996), p. 255 n. 36; Michael W. Kauffman, American Brutus (New York: Random House,

2004), pp. 362 & 469 n.24; Edwards and Steers, p. 1329 n.1.

[9] New York Times, February 22, 1865;

Edwards and Steers, p. 1106.

[10] For this and

what follows, see Edwards and Steers, pp. 1104-09.

[11] Lee A. Gladwin,

“Clara Pix Ritter: Confederate Agent” in Prologue: The Journal of the National Archives (Fall 2007), p. 20.

[12] Gladwin, p. 23.

[13] Union Provost

Marshal’s File, 1861-1867, War Department Collection of Confederate Records,

Record Group 109, Entry 465, National Archives, Washington, D.C. The 1876 Official Register of the United States,

p. 231, indicates that John A. Gould was still working in the Adjutant

General’s Office as of September 30, 1875. His death certificate indicates

that he died on February 18, 1876, age

83.

[14] Gladwin, p. 23.

[15] Gladwin, p. 23;

Clara Ritter and Henry T. Ritter Files, Union Provost Marshals’ File Of Papers

Relating To Individual Civilians, Record Group 109, NARA M-345, National

Archives (retrieved from Fold3).

[16] Tombstone of

Washington Ritter, New City Cemetery, Galveston, TX; New York City Municipal

Deaths, 1795-1949, Family Search.

[17] Chicago Tribune, March 6, 1880. For what

follows see Superior Court of Cook County, Illinois, Chancery Division, Case

No. S-75400.

[18] New York City

Bureau of Vital Statistics, Henry Ludlow Ritter birth certificate.

[19] Galveston Daily News, November 13, 1921,

and November 16, 1895.

[20] Morrison & Fourmy’s General Directory of

the City of Galveston: 1881-1882,

pp. 80, 292.

[21] Morrison & Fourmy’s General Directory of

the City of Galveston: 1888-1889, p. 330.

[22] New York

Herald, September 27, 1890; Galveston Daily News, June 28, 1896.

[23] New York City

Marriage Records, 1829-1940, Family Search database; 1900 census entry for Mary

Florence Johnson Ritter and her children in Yonkers, NY.

[24] For this and

what follows see New York Herald,

September 27, 1890; New York Herald,

September 28, 1890; Evening Telegram,

September 27, 1890; New York Times,

September 28, 1890; New York Herald,

October 1, 1890; New York Herald, October 10,

1890; The Press, October 16, 1890; New York Tribune, November 26, 1890.

[25] Henry Ritter

told a reporter that he would support Mamie because her family had disowned her. If so, Eva Zaun, Mamie’s

mother, may have had a change of heart; her will, made in 1892, provides for

the remainder of her estate to go to her children, without listing them by name

or excluding any by name. Will of Eva Zaun, Ancestry.com, New York, Wills and

Probate Records, 1659-1999.

[26] Morrison & Fourmy’s General Directory of

the City of Galveston; 1893-94; Galveston

Daily News, November 22, 1896.

[27] Galveston Daily News, June 28, 1896.

[28] John Burnett,

“The Tempest at Galveston,” NPR broadcast, November 30, 2017,

https://www.npr.org/2017/11/30/566950...

[29]

https://www.galvestonhistorycenter.or...

[30] Ancestry.com,

U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995.

[31] For what

follows see City of New York, Death Certificate No. 2013 for Mary C. Ritter; 1900

federal census; New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division, First Department, In the Matter of Proving the Last Will and

Testament of Henry Ludlow Ritter, Papers on Appeal, No. 506 (1901); In re Ritter, 1901 N.Y. App. Div. LEXIS

1384; 62 A.D. 618; 71 N.Y.S. 1147.

[32] New York Times, August 30, 1900.

[33] Ancestry.com, U.S.

National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, 1866-1938, Bath, Register p.

394/11200; Henry T. Ritter, pension application no. 1277371, certificate no. 1052726,

Record Group 15, National Archives, Washington, D.C.;

https://www.nps.gov/places/bath-branc....

[34] Ancestry.com,

U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995; Death certificate for Clara Pix Ritter.

November 9, 2019

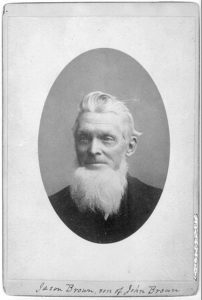

Jason Brown’s “Honey Moon”

As part of my research into my novel-in-progress, John Brown’s Women, I came across this delightful letter from Jason Brown, John Brown’s second son, to his sister Ruth Brown, in the Edwin Cotter Collection held by the State University of New York at Plattsburgh. (The SUNY letter is a photocopy of an original; where the original is I have no idea.)

In 1847, John Brown had yet to gain fame as an abolitionist; if he was known for anything at the time, it was for raising sheep. For several years, he had been in a business partnership with Simon Perkins, an Akron, Ohio, grandee who was one of the founders of that city. Believing that wool-growers were being fleeced by manufacturers, John Brown persuaded Perkins that the partners should open a wool commission house in Springfield, Massachusetts. By the time Jason wrote his letter in August 1847, most of the large Brown family had moved to Springfield. Jason and his unmarried brother Owen stayed behind to manage the Perkins-Brown flock in Akron, while Ruth remained at the Grand River Institute in Austinburg, Ohio, where she attended school.

Both Jason and his older brother, John Brown, Jr., married in July 1847. John Jr. wed Wealthy Hotchkiss, whom he had met while attending Grand River Institute, and promptly moved with his bride to Springfield to work as a clerk for his father. Jason Brown married an Akron girl, Ellen Sherbondy (referred to in the letter as “Eleanor”–the only time I have seen her named as such). For reasons that are not clear, at least some of the Browns seem to have disapproved of Jason’s marriage: John Jr., for one, openly advised against it, as Jason noted in a letter dated September 9, 1847: “You recollect you sent me a letter from Austinburg awhile ago which predicted an unhappy and miserable life for me if I married Ellen; that letter I put into the fire, but remember, I did not burn my affection for you with it.”

Ruth, however, seems to have been more welcoming of Jason’s bride. Accordingly, Jason wrote to her as follows:

Akron Aug 28 1847

Dear Sister

I received your excellent letter of the 5th in good season and would have replied sooner, but being without the material to make a good letter (i.e., the reddy [?]) till now, I delayed. I own that I have been rather slack about my promise to write you, but it is not because I have forgotten you. No I hope I have more of a heart to forget you in two months time, but I have sometimes thought that you would be willing to forget me if I married Miss Eleanor, but your precious letter convinced me to the contrary. You wanted me to own up and tell you all about my matters. I will with a promptitude that becomes a boy of my cloth with so good a wife as I have. Ruth you never dreamed that I could get one so wholehearted and worthy as she is. I should be proud of having you see her with me at that Antislavery Fair out yonder if it was in my power to do so, but I cannot. Owen is going to leave me in a few days and then you had been believe I shall have enough to do. You must excuse me if I write some nonsense for I can’t help it I do feel so greeable here. You said in your letter that you “was very much surprised [to] hear that I was going to be married so soon, but supposed it was all for the best”. So I supposed a good while ago, but now I know it is for the very best. If I sinned in so doing, I sinned willfully, and my blood (not cold blood) is upon my own head. Eleanor sends her love. Says she thought you would be lonesome there, after John and Wealthy left you, but says she suspects by the long and pleasant rides that you tell of, that you have found a friend that sticks closer than a Brother. Hopes you will bring Mr. Warren out here in some of your rides, says she thinks it would be “perfectly right.” I received a letter from John a few days since, dated Aug. 12th he says all are well, &c. and that Wealthy can appreciate the beauty of Springfield (I suppose he means John) and that they had but just go through the Honey Moon. Now this is not the case with me, I have but just got the Wool off my eyes so that I can see the Honey Moon in its true light and glory. Fulfill your promise to Eleanor and write her that letter and write me a word in due season. I enclose $3.00 and am sorry that I cannot send you more; I would willingly if I had it. I believe from John’s account of Mr. Warren that he is a wholesouled young man. Go ahead Brethering and Sisters.

J.

While Jason mentions Ruth’s rides with a “Mr. Warren” (perhaps Jones K. Warren, a fellow student of Ruth’s), Ruth ended up marrying Henry Thompson, whom she met when the Browns moved to Essex County, New York, in 1849.

In 1855, Jason and Ellen traveled to Kansas; tragically, their son Austin fell ill with cholera while aboard a steamer and had to be hastily buried in Missouri. Though the couple continued on their journey, their son’s death was only the start of their troubles in “Bleeding Kansas,” where anti-slavery and pro-slavery settlers vied with increasing violence for control of the territory. Following the “Pottawatomie massacre” of five pro-slavery settlers by John Brown Sr. and a few others in 1856, Jason, who had not been involved in the murders, was arrested and his cabin was burned to the ground. He and Ellen, along with their remaining son, returned to Ohio that same year. Nonetheless, Jason’s taste for life out west had not been quenched; later, he moved to California. Ellen, however, stayed put in Akron, where she kept house for her widowed son, Charles. As Jason wrote to Franklin Sanborn on August 18, 1886, “She was always opposed to my coming here and said she could never leave Akron again, to live in the west after trying ‘that Kansas move’. I cannot blame her as I have always believed that a wife has the same right to decide where her home shall be; as a husband.”

By August 1894, when he gave a presentation to the Summit County Horticultural Society about his experiences with growing California grapes, Jason had returned to Akron, probably because of Ellen’s failing health. She died there on August 15, 1895, of heart disease. After her death, Jason returned to California, but spent his declining years in Ohio, where he died on December 24, 1912.

Photo of Ellen Brown from Walter Arnold Jackson Collection, Ohio Genealogical Society; photo of Jason Brown from Library of Congress.

October 1, 2019

Blog Tour

Today is publication day for my latest novel, The First Lady and the Rebel! I’m kicking it off with a blog tour run by Amy Bruno’s excellent Historical Fiction Virtual Book Tours. Please stop by!

Blog Tour Schedule

Tuesday, October 1

Review at Gwendalyn’s Books

Wednesday, October 2

Review at Faery Tales Are Real

Review & Guest Post at Clarissa Reads it All

Thursday, October 3

Review at Broken Teepee

Review at Stephanie’s Novel Fiction

Friday, October 4

Review at Donna’s Book Blog

Saturday, October 5

Review at So Many Books, So Little Time

Monday, October 7

Review at Hooked on Books

Interview at Reading the Past

Tuesday, October 8

Review at The Lit Bitch

Wednesday, October 9

Review at Just One More Chapter

Thursday, October 10

Review at Unabridged Chick

Friday, October 11

Interview at Unabridged Chick

Review at View from the Birdhouse

Saturday, October 12

Review at Jorie Loves a Story

Monday, October 14

Review at 100 Pages a Day

Interview at Jorie Loves a Story

Tuesday, October 15

Review at Passages to the Past

September 24, 2019

The First Lady and the Rebel: An Outtake

Like most novels, The First Lady and the Rebel underwent revisions on its path to publication (look for it on October 1!). This is the epilogue in the first draft. It was replaced by one that I felt was more in keeping with the focus of the novel: the relationship between the two Todd sisters of the title, Mary Lincoln and Emily Todd Helm.

Emily Todd Helm as an older woman (Kentucky Digital Library)

Epilogue

October 1911

Emily had hesitated about accepting Dr. Shaw’s kind invitation to address the convention. “Just a few words of welcome,” Dr. Shaw had written. It wasn’t as if Emily had become shy in her old age; if anything, she was more outspoken. But all of her public appearances thus far had related to the war. There were the regular reunions of the Orphan Brigade, which she delighted in attending, even though by now the number of attendees was getting sadly small. Whereas in the old days, the talk at the reunions had focused on the battles and the brave men like Hardin and Mac who had died in them, now the conversation centered around those who had died in their offices and in their fields and tucked up comfortably in their beds.

And there were the Lincoln events. Of her siblings, only George and Margaret had survived the nineteenth century, and Margaret’s death a few years before had left Emily as the last living sister of Mary Lincoln. So it was Emily the reporters turned to when some anniversary or the other brought Mary to mind, and it was Emily who had been asked to lift the drape from the statue of Lincoln when it was unveiled in his birthplace of Hodgenville, Kentucky. Robert had been there too. (Poor Robert! From the way some people talked now, he had enjoyed committing his unfortunate mother to that private asylum, when Emily and every person with sense knew that it had broken his heart.) Unused to the Kentucky heat after all his years in Vermont, he’d had become faint and had had to retire to the special train that had brought them there. Emily hadn’t even wilted, as she’d been pleased to tell Kate, Dee, and Ben Junior, who tended to fuss over her these days like the children none of them had ever had. (A slight sore spot with Emily where Kate and Ben Junior were concerned, as they could have at least made an effort by finding someone to marry. But then, Emily hadn’t exactly set them an example, having never remarried. Not only could no man measure up to Hardin, but at some point, maybe after she’d finally sold her cotton and bought a house all by herself, or maybe during all those years when she had worked as the postmistress for Elizabethtown, she had realized that she rather liked being answerable to no one.)

In a way it was good that Dr. Shaw wasn’t inviting her to yet another war-related event, because these always brought up questions that Emily struggled to answer. What exactly had the South been fighting for? Might slavery had faded of its own accord without the cost of so many men’s lives? Was the country better for all that bloodshed? Would North and South ever really understand each other? In the end, it was easier not to answer such questions at all. Instead, whenever a reporter approached her, she stuck to talking about people. People like Maggie, who had turned up back in Lexington after the war and looked after the children until she had married, although Emily admitted to herself that it was probably Kentucky more than anything that had brought her back. People like her brother-in-law the President. People like Hardin. People like her sister Mary.

In any case, reporters seldom asked Emily about anything other than those people she’d known. They saved the more complicated questions for the men they interviewed. As if half of America couldn’t form an intelligent thought about events that had affected them as much as anybody.

She thought of the sermon that had been preached at Mary’s funeral, back in 1882, about the two trees so intertwined so that when the first was struck by lightning, the second had essentially died at the same time, even though it lingered in its withered state for years afterward. It was a beautiful sermon, and Emily had understood the point: that Mary had all but died the night of her husband’s assassination. And in a sense she had, Emily knew; she’d never been quite the same, and certainly the last few months of her life she had been a pathetic figure, never leaving her room at the Edwards house and passing her days digging through her dozens of trunks. Still, Emily thought the minister could have given Mary more credit for carrying on all these years. She’d gotten Tad the education that had been neglected during his father’s lifetime, traveled twice through Europe, wrestled a pension from the hands of a stingy government. She hadn’t just withered like a pathetic skinny tree.

And neither had Emily. Neither had most of the war widows she knew, and she certainly knew a lot of war widows. Surely they deserved a little credit.

So with all that in mind, she had accepted Dr. Shaw’s invitation to say a few words of welcome, and here she sat, decked in a yellow sash and blushing a bit as Dr. Shaw introduced her.

She stepped to the podium, first adjusting her large hat. (In her prime, ladies had wore most of their clothes around their hips. Now it seemed they wore them on their heads.) For a moment, she hesitated–she’d never had to give a full-fledged speech, even a short one.

Then she was astounded to see the entire assembly rising, the mass of them almost obscuring the signs they held, VOTES FOR WOMEN. With their expectant eyes upon her, Emily cleared her throat and found her voice.

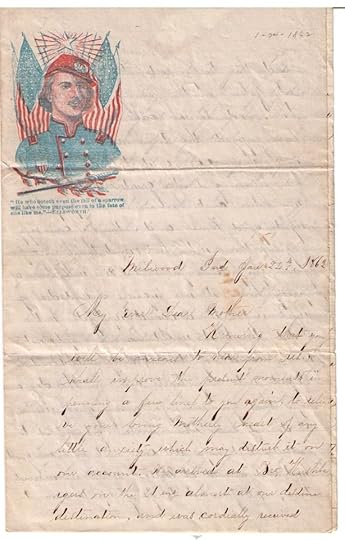

August 13, 2019

Life Goes On

I bought this 1862 letter mainly because of the patriotic letterhead, which depicts Elmer E. Ellsworth, an early casualty of the Civil War, shot while he was exiting the Marshall House hotel in Alexandria after removing a Confederate flag from its roof. As the transcript shows, however, it’s a nice reminder of how ordinary life in America went on even while the war continued to rage.

Dated from the hamlet of Milwood in Kosciusko County, Indiana, the letter is written by a new bride, “Frank” Jones, with a postscript from her husband, J.R. Jones. There was a John R. Jones in the 1860 census in the area who listed himself as a schoolteacher, and who lived with a man named William, so he might be the new husband here. I haven’t been able to trace the couple beyond that, though.

Here is a transcript (original spelling retained):

Milwood, Ind. Jan. 24, 1862

My ever Dear Mother

Knowing that you will be anxious to hear from us, I shall

improve the present moments in perusing a few lines to you again, to relieve

your loving Motherly heart of any little anxiety which may disturb it on our

account. We arrived at Bro. Hershberger’s on the 21st almost at our [apparently

superfluous word] destination, and was cordially received had the turkey roste

that they had promised John on the evening of our arrival. Have made several calls with our neighbors

have enjoyed the time as well I suppose as I well can, and this day Jones took me sleighing on the great

west to see my new house, and home. He has prepared a right good house and I

think I can enjoy myself there with him, and think in a few years if fortune

favors us we will have a pretty home, it will require a good deal of work until

it is cleared up yet. Mother I did think it would have been pleasant if you and

my other dear friends could have stepped into my house with me this day and

hope that you will before a very great while. I do not know when we will get

moved to ourselves but hope we can next week. Our goods had not arrived at

Warsaw when we arrived there. Mr. Jones intends going up tomorrow to see after

them, and to get a stove which I suppose they have got along by this time. We have

very good sleighing here. I have had quite a number of slay-rides since we

landed had been to church last evening. They got up a sled load of us and away

we went. His Bro. Wm. preached. I don’t see much difference in there church to

ours and people seem very sociable. I also enjoyed myself very pleasantly at

Sister Susans they have now a very nice opening and a beautiful place to live,

and appear to be getting along well. O Mother I did wish you could have been

with us. I now you could not have helped but enjoyed yourself. They took us

around slaying to see the neighborhood I liked the neighborhood very much.

Mother I must now close hoping you are enjoying life pleasantly and have a good

girl with you. I now close by saying I am well, and shall now introduce my

husband. — My love to all the good people and let us hear from you often.

Yours with a daughters love.

Mother [Stump?] as Frank has written about all perhaps that

would be interesting to you at present therefore I shall only add a line. We

are pretty near the same here now as when I left. Hope this will find you enjoying life

comfortably and in good health. Frank is very cheerful and enjoys good health

no more at present yours truly J. R. Jones.

We shall write again as soon as we get moved and fairly set

up.

July 30, 2019

Benjamin Hardin Helm’s Last Will and Testament

As long-term readers of this blog will know, I’m fond of wills, and I was pleased to find that one major character in The First Lady and the Rebel, Emily Todd Helm’s husband Benjamin Hardin Helm, left one behind. (Abraham Lincoln, married to Emily’s sister Mary, died intestate.)

Emily and Hardin, early in their marriage (Kentucky Digital Library)

Emily and Hardin, early in their marriage (Kentucky Digital Library)A graduate of West Point, Hardin, as he was called, made his will on May 13, 1861, with the expectation that he would soon be joining the Confederate army. Just a few days before, he had procured letters of introduction to Jefferson Davis. Sometime between the date of his will and May 19, 1861, he turned up in Montgomery, Alabama, then the Confederate capital, but the Confederate president urged him instead to return to his native Kentucky and to work to bring the state into the Confederacy. Hardin dutifully returned to Louisville, but by the fall of 1861 had joined the rebel forces. Commanding the storied “Orphan Brigade” (so-called because its Kentucky soldiers could not return to their native state, which stayed in the Union), Hardin was mortally wounded at the battle of Chickamauga in September 1863.

Hardin’s will is a short and simple one. Notably, although it is occasionally claimed that Hardin, who practiced law in Louisville before joining the Confederate army, owned no slaves, his will belies that, as do letters and family lore that mention two slaves: Margaret, who looked after Emily’s children, and Phil, who accompanied Hardin to war.

I B. H. Helm do publish this as my last will and testament.

I will and bequeath to my beloved wife Emily T. Helm during her life or widowhood all my property consisting of slaves, money, notes and accounts to be used by her in rearing and educating our children. At the death of my said wife or if she should marry again, then my property is to be equally divided between our children. If our children should die without issue then it is my will that my said wife take the property herein devised absolutely. I appoint and constitute my said wife Emily T. Helm Executrix of this my last will & testament. In witness I have this the 13th day of May 1861 set my hand.

B.H. Helm

Hardin’s death left his widow and three young children in straitened circumstances, with little to call their own except for the pay due to Hardin as a brigadier general, some receipts for cotton and tobacco he had stored in various warehouses in the South, and Phil and Margaret.

Hardin’s grave at the Helm family cemetery in Elizabethtown, Kentucky

Hardin’s grave at the Helm family cemetery in Elizabethtown, KentuckyA family story has it that after his master’s death, Phil made his way across the Union lines and returned to Kentucky, where after emancipation he worked as a hack driver. Margaret was a different story. At the time of her husband’s death, Emily, who had followed her husband south, was in Georgia. Having made the decision to return to Kentucky, she soon learned that Margaret could not accompany her, at least not as a slave. Accordingly, Margaret remained in the South, probably with one of Emily’s married sisters in Selma, Alabama; what became of her after the war is unknown.

Emily, meanwhile, obtained a pass to return to Kentucky, but balked at signing the required oath of loyalty to the Union. At that point, her brother-in-law Abraham Lincoln stepped in and ordered that Emily come to the White House. After an awkward, week-long visit with the Lincolns in December 1863, Emily at last returned to Kentucky. There, in Louisville on December 30, 1863, she was able to admit Hardin’s will to probate. She would spend the rest of the war attempting to get her cotton out of the South so it could be sold in the North–a task she was still engaged in on April 14, 1865, when her brother-in-law was assassinated.

The widowed Emily (Kentucky Digital Library)

The widowed Emily (Kentucky Digital Library)While Hardin’s will envisioned the possibility that Emily would remarry, this never came to pass. Emily died on February 20, 1930 at age 93, having outlived her husband over 66 years.

July 1, 2019

A Visit to North Elba

One of the greatest thrills for a historical novelist is being able to walk in his or her characters’ footsteps by visiting the places where they once lived. I first got this privilege while writing The Traitor’s Wife, when I visited the De Clare/Despenser stronghold of Caerphilly Castle, and most recently when researching my novel in progress about the women associated with the abolitionist John Brown.

Brown was a restless man, who at various times as an adult lived in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Massachusetts, Kansas, New York, and Maryland. Some residences associated with him have long since vanished, but others remain, such as the John Brown house in Akron, Ohio, the Kennedy Farm in Washington County, Maryland, and the John Brown Farm in North Elba, New York. It was at the North Elba farm, the last house owned by John Brown, that his wife Mary and his younger children were living at the time of the Harpers Ferry raid in 1859. There, Mary and her children received the terrible news that the raid had failed, that two of John and Mary’s sons, Oliver and Watson, had been killed there, and that John had been taken prisoner. It was there that John–who had spent little time at the farm himself, having followed his sons to Kansas and then pursued the militant abolitionism that would lead to his fatal raid–was laid to rest. Although he had urged Mary to remain at the farm after his death, this was not a wish that Mary would heed. Tired of the harsh winters in North Elba and seeking better opportunities for her daughters, she sold the farm and made the hazardous journey by wagon train to California in 1864. In 1882, during a cross-country trip, she returned to North Elba to witness the burial of her son Watson, whose remains had been appropriated by a medical college after the Harpers Ferry raid and had fallen into the hands of an Indiana physician during the Civil War. Mary died in California in 1884.

The Brown farmhouse was altered somewhat after Mary sold it, but as maintained today by New York State, it still gives a vivid sense of the Browns’ sojourn there. Going there was a moving experience for me.

May 27, 2019

A Memorial Day Tribute to Charles P. Tidd and Carrie Cutter

This Memorial Day, I’m remembering, Sgt. Charles P. Tidd, and his friend and nurse, Carrie Cutter, both of whom died in service to their country.

Tidd, one of John Brown’s raiders, evaded capture after the raid. After the Civil War broke out, he enlisted in the 21st Massachusetts Infantry under the assumed name of Charles Plummer. He never saw battle, but died of typhoid fever on February 8, 1862, aboard the steamer Northerner while the battle of Roanoke Island raged nearby. Nursing him was his friend Carrie Cutter, who had accompanied her father, surgeon Calvin Cutter, to war. Carrie wrote to Charles’s sister Evelyn Tidd, “Our Charlie is now in the spirit world.” Tidd is believed to be the “Charles Coledge” buried at New Bern National Cemetery, the name being changed to protect his grave from desecration.

From Find-A-Grave

From Find-A-GraveCarrie’s stepmother, Eunice P. Cutter, who had known Tidd since the days of the Kansas border wars, read a tribute to him in 1888 at a veterans’ reunion. “Sergeant Tidd dared to do right as he understood his Bible, dared to be true to his convictions, ‘to loose the bands of wickedness, to undo heavy burdens, and to let the oppressed go free;’ his ardent zeal often led him into peril.” (Worcester Daily Spy, August 24, 1888.)

Charles P. Tidd, Kansas State Historical Society

Charles P. Tidd, Kansas State Historical SocietyAnnie Brown Adams, who had gotten to know Tidd while serving as her father’s housekeeper and lookout at the raiders’ headquarters in Maryland, recalled years later for Oswald Garrison Villard that her friend “had not much education, but good common sense. After the raid he began to study, and tried to repair his deficiencies. He was by no means handsome. He had a quick temper, but was kind-hearted. His rages soon passed and then he tried all he could to repair damages. He was a fine singer and of strong family affections.”

As for Carrie, when Dr. Cutter, an abolitionist who had been active in Kansas before the war, joined the 21st Massachusetts Infantry as its surgeon, Carrie, an educated young lady who had attended Mount Holyoke, went south with her father and served as his secretary and as a nurse. Having sat beside Tidd in his dying moments, nineteen-year-old Carrie attended to the sick and wounded after the battle of Roanoke Island but contracted typhoid fever and died on the Northerner on March 24, 1862. She asked to be buried next to her friend “Charlie.” A manuscript at the Library of Congress containing biographical notes about Carrie, probably assembled by her stepmother, recalls, “Twice she was asked by her father during her sickness if she regretted coming out, should she not recover. She replied with more than her usual decision and emphasis, ‘Most surely not.'”

Styled “the Florence Nightingale of the 21st,” Carrie was buried with military honors at Roanoke Island and was later moved to the New Bern National Cemetery, where she lies today. She is also commemorated at the Elm Street Cemetery in her birthplace of Milford, New Hampshire.

From Find-A-Grave

From Find-A-Grave From New Bern Historical Society

From New Bern Historical Society

May 20, 2019

What’s New?

Recently, I added this nifty carte-de-visite to my modest collection of Lincoln memorabilia–a memorial photograph that’s a composite of photos taken during his presidency.

Aside from what’s new in my collection, what’s new in my writing? While awaiting publication of The First Lady and the Rebel (coming in October!) I’ve been busy working on another novel, this one dealing with three women in the life of the abolitionist John Brown: his stoic, hardy second wife, Mary Brown, his progressive-minded daughter-in-law Wealthy Hotchkiss Brown, and his tempestuous, fiercely devoted daughter Annie Brown. Combined, their stories span a continent, although two of my characters found themselves just miles from my Maryland home: Annie, when she served as her father’s “watchdog” at his headquarters at the Kennedy Farm in Maryland prior to the raid on Harper’s Ferry, and Mary, when she traveled to Virginia to visit her husband on the night before his execution.

I’ll be posting more about these women (and the men in their lives) in the future. In the meantime, here are a few photographs related to Annie Brown, who later married a Samuel Adams. (If the third photograph looks as if it has been altered, it has been: in the original photograph, which can be seen on the Ancestry website, Annie is posing with two of her children.)

The Kennedy Farm

The Kennedy Farm Annie Brown, depicted in an exhibit at Harpers Ferry.

Annie Brown, depicted in an exhibit at Harpers Ferry. Annie Brown Adams, early 1870s, from the Library of Congress

Annie Brown Adams, early 1870s, from the Library of Congress