Susan Higginbotham's Blog: History Refreshed by Susan HIgginbotham, page 5

April 15, 2019

Guest Post by Heather R. Darsie: When Anne Met Henry

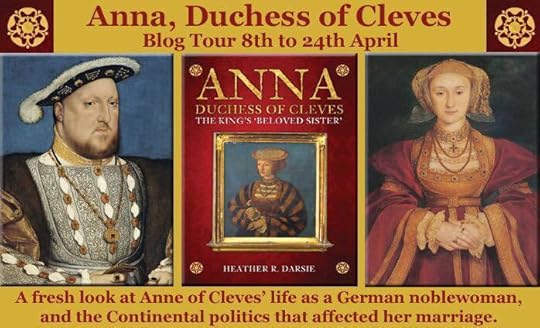

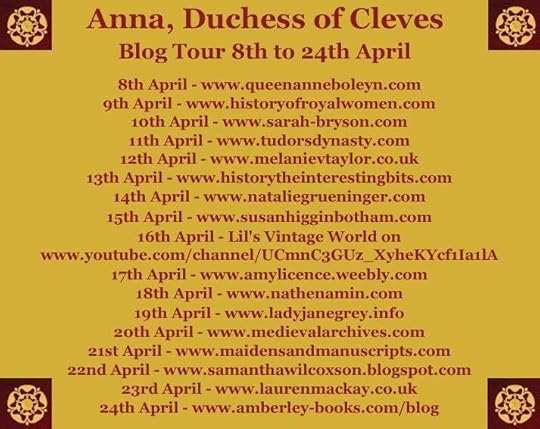

I’m delighted to be one of the stops on Heather R. Darsie’s blog tour for her new biography of Anne of Cleves, one of the least-studied of Henry VIII’s six wives. Over to Heather:

Anna of Cleves Meets Henry VIII: An Excerpt

By Heather R.

Darsie

I have always been

intrigued by the claims that Anna was horribly disappointing to Henry at their

first meeting. I knew that most information about their relationship came out

during the annulment proceedings in late June to early July 1540. Given the

timing, I thought it was suspicious. Imagine my delight when a German account,

written a few days after Anna and Henry’s first meeting and not six months

later and for nefarious purpose, had significantly different facts in it. The

letter was sent to Anna’s brother Wilhelm. He and their mother the widowed

Duchess Maria were likely eager to hear how the new Queen Consort of England

was doing.

“Anna was resting at Rochester on 1

January 1540 when she was informed of a visitor. Anna had met many of her new

subjects and was surely exhausted by the time she arrived in Rochester, and

less attentive than usual due to her fatigue. Anna encountered hundreds of

English people who were appointed to meet her, including numerous peers of the

realm and their personal entourages. Perhaps she was spending some of her time

at Rochester daydreaming about meeting Henry or going over how she would greet

Henry in the English language. She would not have the opportunity to follow

through with any of those plans.

Anna received that unexpected visitor on

1 January 1540, and the German and English accounts of the first meeting

between Anna and Henry differ from each other. Olisleger, an eyewitness,

dispatched a letter to Duke Wilhelm within a few days following the meeting.

According to Olisleger, while Anna was at Rochester watching a bull-baiting

with her German lords, Henry came to call on her after lunch with ten or twelve

of his gentlemen. This presumably included Sir Anthony Browne, Henry’s Master

of Horse, who was deposed at the annulment trial later on that year. It was New

Year’s Day 1540, and the excited groom could not wait to meet his bride. Henry

and his men were dressed as private persons. Henry entered the room and greeted

Anna, which may have unsettled her. After all, Anna was used to the culture of

the Frauenzimmer, so having strange men come into her

presence without proper preparation could have caught her off guard.

Anna invited this private person, a representative

of the King, to dine with her. Afterward, he presented Anna with a gorgeous

gift ‘from the King’ for New Year: a crystal goblet, the lid and foot of which

were completely gilded and inlaid with diamonds and rubies. Another golden band

encircled the goblet, also with inlaid rubies and diamonds. Afterward, Henry

and Anna enjoyed banqueting together. Henry stayed over to the next day, 2

January 1540, though at a separate location so as not to offend Anna’s virtue.

He and his men broke their fast with Anna and her gentlemen. Henry then

returned to Greenwich. Anna herself departed for Dartford with her train later

that day. It is unclear at what point Henry made his identity known to Anna.

Hall’s Chronicle described the meeting:

‘the king which sore desired to see her

Grace accompanied with no more then [sic] 8 persons of his privy chamber, and

both he and they all appareled in marble coats privily came to Rochester, and

suddenly came to her presence, which therewith was somewhat astonied: but after

he had spoken and welcomed her, she was most gracious and loving countenance

and behavior him received and welcomed on her knees, whom he gently took up and

kissed: and all that afternoon, communed and devised with her, and that night

supped with her, and the next day he departed to Greenwich, and she came to

Dartford.’”

Excerpt from Anna, Duchess of Cleves: The King’s ‘Beloved

Sister’, by Heather R. Darsie, copyright Amberley Publishing 2019; pgs.

110-112. All rights reserved.

April 3, 2019

Mr. Helm Goes to Washington–And Then to Montgomery

In March 1861, one of many job-seekers arrived at the White House, looking for patronage at the hands of the new President, Abraham Lincoln. Unlike many, this one was successful. Ultimately, though, he turned down the offer–and ended up fighting, and dying, for the Confederacy.

The job-seeker was Benjamin Hardin Helm, who was married to Mary Lincoln’s half-sister Emily Todd. A native of Elizabethtown, Kentucky, Helm (“Hardin” to his friends) was a West Point graduate. While stationed in Texas, he became ill and ended up resigning from the army. After studying law in Louisville, Kentucky, and at Harvard, he set up shop as a lawyer. At the time Lincoln became President, Hardin and Emily were living in Louisville with their two young daughters.

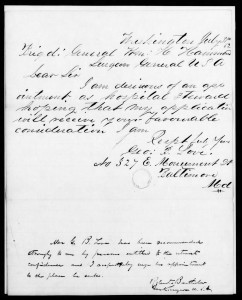

But with a brother-in-law in the

White House, either Hardin or Emily saw an opportunity. So in March 1861,

Hardin composed this letter to a fellow Kentuckian, Joseph Holt, the outgoing

Secretary of War. (Holt would later prosecute those accused of conspiring to

assassinate President Lincoln.) As far as I know, it has not been published

before:

Louisville, KY

March 14, 1861

Hon. Joseph Holt

Washington City, D.C.

Sir

I hope you will pardon me for intruding myself upon your notice at this time. I have presumed (I hope not too far) upon the friendly relations that have heretofore existed between yourself & my father’s family to write this letter requesting a favor at your hands.

I have been for some time an applicant for the position of Pay-Master in the United States Army and I presume my application is now on file in the Adjutant General’s office, at least I was so informed by an officer in that department. I graduated at the Military Academy at West Point in 1851 and refer you to the Cadet Register of that date for my standing in my class. I served some time in the Army after I graduated. I contracted bad health while serving in Texas and was compelled to resign my commission. Since the restoration of my health I have been anxious to return to service.

I understand that a position has lately opened in the Pay department by the resignation of Major Macklin [Sackfield Maclin]. Will you do me the great favor & use your influence with the President & Secretary of War to procure for me the position made vacant by the resignation above mentioned.

I shall feel grateful to you for any assistance you can give me in this matter.

I am with much respect

Your obd’t servant

Ben Hardin Helm

Hardin no sooner sent this letter, though, than he decided that more drastic action was needed. On March 21, 1861, Elizabeth Todd Grimsley, who had been invited to spend time with her cousin Mary Lincoln at the White House, wrote to yet another Todd, John Todd Stuart, “Mr. Hardin Helm came yesterday wants to return to the army.” (Elizabeth, a divorcee, was hoping for a postmaster’s position. Her wish was not fulfilled.)

In the White House, as the country grew more jittery over the prospect of war, Hardin made himself useful. Referring to Hardin mistakenly as “Captain Todd,” Colonel Charles P. Stone, who was quietly seeing to the defense of the President’s House, explained in 1885:

From the first I took, under the orders of the general-in-chief, especial care in guarding the Executive Mansion; without, however, doing it so ostentatiously as to attract public attention. It was not considered advisable that it should appear that the President of the United States was for his personal safety obliged to surround himself by armed guards. Mr. Lincoln was not consulted in the matter. But Captain Todd, formerly an officer of the regular army, who was, I believe, the brother-in-law of Mrs. Lincoln, was then residing in the Presidential Mansion, and with him I was daily and nightly in communication, in order that, in case of danger, one person in the President’s household should know where to find the main body of the guard, to the officer commanding which Captain Todd was each night introduced. Double sentries were placed in the shrubbery all around the mansion and the main body of the guard was posted in a vacant basement room from which a staircase led to the upper floors.

A person entering by the main gate and walking up to the front door of the Executive Mansion during the night could see no sign of a guard ; but from the moment any one entered the grounds by any entrance, he was under the view of at least two riflemen standing silent in the shrubbery, and any suspicious movement on his part would have caused his immediate arrest ; and inside, the call of Captain Todd would have been promptly answered by armed men. The precautions were taken before Fort Sumter was fired on as well as afterward.

Meanwhile, President Lincoln was quite happy to gratify his brother-in-law. On April 16, 1861, he wrote Simon Cameron, the Secretary of War, to remind him that he had requested some time ago that Hardin get the appointment and that he still wished it for Hardin. Even before the nomination was formalized, it had leaked to the Louisville Daily Courier, which reported on April 20, 1861: “Col Ben. Hardin Helm, of this city has been appointed Paymaster of the army by President Lincoln.”

But the news was premature. The nation was now at war, and Hardin, from a slaveholding family, had begun to have second thoughts about his allegiances. According to a story that circulated in the 1890s, which Helm’s daughter Katherine repeated in her biography of Mary Lincoln, Helm asked the President for more time to consider the offer. While mulling it over, he happened to stumble upon Colonel Robert E. Lee, who confided to Helm that Lee himself had just resigned his commission in the United States Army to side with his native Virginia. Asked for advice, Colonel Lee replied, “My mind is too much disturbed to give you any advice. But do what your conscience and honor bid.”

The Lee story, though it has been widely accepted, seems a little too good to be true. There doesn’t appear to have been any opportunity for the men to have crossed paths before: While both were West Pointers, they were not contemporaries as students there, and Hardin had graduated from West Point long before Lee returned there as its superintendent. It’s hard, then, to imagine Lee confiding to someone who at best might have been a passing acquaintance. Whatever the truth of this story, however, Helm ended up reaching a decision similar to that of Lee. He refused President Lincoln’s offer, which had been made official on April 25, 1861, and returned to Kentucky. Soon, he was headed to Montgomery, Alabama (then the capital of the Confederacy) with letters of introduction to Jefferson Davis. The Confederate president, however, thought that Helm’s services would be better spent in pressing Kentucky to secede from the Union. But Hardin would not remain a civilian for long. By the fall of 1861, he had left his Louisville home behind and was encamped with other Confederates at Bowling Green. His choice proved to be a fatal one: Hardin was mortally wounded in September 1863 at the battle of Chickamauga. Lincoln’s secretary John Hay, recording his death, recalled that Helm had “spent some time with the family here and was made a paymaster by the President.”

Even as his widow mourned him,

she began to craft an alternative story about the paymaster job–one that

endures today. A clipping of an obituary of Hardin in Emily Helm’s papers,

apparently published by an Atlanta paper, gives precise and accurate details of

his civilian and military career that surely must have come from Emily, who had

arrived in Atlanta for Hardin’s funeral and stayed there for a few days afterward.

Hardin, the obituary states, “was approached with proffers of high

position in the Federal army when the war first broke out, but he never

entertained such bribes, preferring rather to labor and suffer in the cause of

liberty with his own people.” Henceforth, in all tellings of the paymaster

story, it would be President Lincoln, eager to keep Hardin in the Union, who

had invited Hardin to Washington and pressed him to take the paymaster position.

Hardin’s lobbying for the position would be discreetly forgotten. As the

narrator of The First Lady and the Rebel

(coming in October 2019) states, the truth was simply too complicated.

Sources:

Stephen Berry, House of Abraham: Lincoln and the Todds, a

Family Divided by War.

Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner

Ettlinger, eds., Inside Lincoln’s White

House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay.

Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, vol. 4.

James B. Conroy, Lincoln’s White House: The People’s House in Wartime.

General Orders of the War Department, Embracing the Years 1861, 1862,

and 1863, vol. I.

Elizabeth Grimsley letters,

Special Collections, Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library

Richard E. Hart, “Elizabeth Jane Todd Grimsley and The Illinois Todds,” For the People, Winter 2013.

Benjamin Hardin Helm service file (retrieved from fold3.com).

Emilie Todd Helm papers, Kentucky

Historical Society.

Katherine Helm, Mary, Wife of Lincoln.

Joseph Holt Papers, Library of

Congress.

“Lincoln and Helm,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 7, 1892

(reprinted from Washington City Herald).

Charles P. Stone, “Washington

in March and April, 1861,” Magazine

of American History, Vol. XIV, July-December 1885.

March 16, 2019

The Great Couch Dust-Up: A Letter from Phoebe Yates Pember to Emily Todd Helm

While doing research for The First Lady and the Rebel, my forthcoming novel about Mary Lincoln and her Confederate half-sister, Emily Todd Helm, I visited the Kentucky Historical Society in Frankfort to look through Emily’s papers. Among the many wartime letters addressed to Emily is this one from a famous correspondent: Phoebe Yates Pember, who served as matron of Richmond’s Chimborazo Hospital during the latter part of the Civil War. As far as I know, no historian has noted the connection between the two women.

Phoebe Yates Pember

Phoebe Yates PemberPhoebe was born to Jacob and Fanny Levy in Charleston, South

Carolina, in 1823. Before the war, she married Thomas Pember, a Bostonian, who

died of consumption in Aiken, South Carolina, in July 1861, only thirty-six.

Widowed and childless, Phoebe returned to live with her parents, who spent the

war in Marietta, Georgia, close to Atlanta. As this letter and others make

clear, she was unhappy with this arrangement and was eager to secure an

appointment to serve in one of the Confederacy’s hospitals. Just a few weeks

after this letter was written, she got her wish and was making her preparations

to move to Richmond.

Emily Todd Helm and her husband, lawyer Benjamin Hardin

Helm, were living in Louisville, Kentucky when the war broke out. Hardin, as he

was called, joined the Confederate army and was eventually made a brigadier

general. Emily and her daughters followed him South, sometimes staying with her

sisters in Selma, Alabama (where Emily gave birth to her son in May 1862), sometimes

boarding with others or living in hotels. At some point, as the letter from

Phoebe shows, Emily stayed with Phoebe and her family. It is unclear when she

was in Marietta, but my own belief is that she was there after August 1862,

when her brother Alexander Todd was killed in a friendly-fire incident outside

of Baton Rouge. During the same incident, Hardin’s horse fell upon him, badly

injuring Hardin’s leg. As Marietta in the 1860s was a health resort, Hardin

might have well gone there to recuperate, accompanied by his family.

Emily Todd Helm

Emily Todd HelmWhether Emily, who was widowed the following year when Hardin was killed at Chickamauga, saw Phoebe again I do not know, but she would have had the chance in March 1865, when President Lincoln allowed Emily, who had returned to Kentucky, to cross into Richmond to recover some cotton that Hardin had stored in various Southern warehouses. Emily left Richmond shortly before it fell, while Phoebe remained at her post at Chimborazo. After the war, she traveled and published her memoirs of her time as a hospital matron as A Southern Woman’s Story: Life in Confederate Richmond. In 1959, Bell Irvin Wiley republished the memoir, along with a number of Phoebe’s letters. Phoebe died in 1913; Emily died in 1930. Other letters of Phoebe’s are held by the University of North Carolina, but I have not seen them. (They sound intriguing: at one point, Phoebe, traveling through Europe, met Oscar Wilde.)

As far as I know, the letter below has not been published

before. Thanks to my Facebook friends who helped me with one puzzling word! (If

anyone notices any mistakes in my transcription, please let me know.)

Marietta, 3 November

1862

I am almost disheartened dear Mrs. Helm writing letters, as

none of them reach their destination, and it is more to satisfy my conscience

than from any idea that this may reach you that I write. Mrs. Nott having left

for Mobile I was the happy recipient of your letter and Mrs. Anzi shared its

contents with me. Dr. Nott arrived a

week after his wife’s departure and followed her home where they will remain

until driven out by the Yankee fleet. Adele is very anxious to get her mother

to consent to carry her on immediately, but besides other reasons, she herself

has been quite sick with a touch of scarlet fever. I think they call it roseola,

or some name of that kind. I heard that

Mrs. Hays arrived the night after you left, but did not see her, for I was so

much harassed by events occurring just at that time that I only went out of my

room for meals. We have had many changes since

you left. Mrs. Duncan was telegraphed for to go to her husband lying

very ill at Knoxville, and Mrs. Gen. Lovell

took your place at the dinner table. Major Goodwin arrived much to the

happiness of his disconsolate wife and by mutual contributions we had a supper

in Mrs. Anzi’s room which was of such magnificent proportions that it almost

put us in mind of the feast in the bible

which “Balazzar gave unto a thousand of his lords.” We had

stewed oysters, and cheese biscuits and sardines, cherries in their own juice, and preserved

peaches, all from old Kentuck, and brought out with Bragg’s army, added to this

a bottle of delicious sauterne wine from New Orleans. Are you not sorry that

you left us? Mrs. Yandell came last night and dear Mrs. Maury who I love so

much is expected tonight. Hiram is disposed of fever, I believe because Mrs.

Hiram has taken care to leave him in Atlanta. She made her appearance here for

one day and looked like a bleached pea hen.

I think

you will be surfeited with gossip, so I mean to tell you a little of myself,

knowing that you will take some interest. Dr. Nott has done all for me

that he can, written to Mrs. Randolph and other friends, but he says the proper

person to apply to is Dr. Moore the surgeon general, with whom he is

unacquainted. I await in great anxiety the answer to these letters as I have

also written to a great many friends. If I could find any one acquainted with

me who knew Dr. Moore personally I could

manage a great deal better. You will see that Congress has made provision for

so many Hospitals, having each a Superintendent, and two Vice Superintendents,

I read are the arrangements in a paper that Dr. Nott sent me. If in any way you

can help me by advice or through friends I know you will.

There

have been some excitements since you left, the most annoying to me the move I

made into a small room at the head of the stairs, too small for a bedstead, so

I brought my old couch, soon appeared that Ishmaelite Hoffman, who informed me

that it must be taken back as Miss Gentry intended sharing my sister’s room and

bed and required the couch to rest on. You may imagine how indignant I was when

I found that I was turned out for this purpose, so I refused to give it up.

However, he had it taken out, and the whole house became in an uproar, so much

so that one of the ladies told Mary Gentry that they advised her as a friend

not to take my place in my sister’s room public opinion being so much against

her that no one would notice her, and the next day the couch came back and Miss

G. remained where she was. However, with

her usual delicacy, she boasts that if she wished she would have kept it. I

am still in Coventry.

You must

not show this feminine, scandal filled letter to anybody, for I was thrown so

intimately with you and felt your kindness so greatly that I cannot feel as if

you are a stranger, only known a few

weeks. Besides I was in so much trouble and my mind so harassed when you were

here that I was selfish and weak in seeking sympathy. You must put a kind

construction upon all I did.

Mrs. Anzi

and Goodwin beg to be remembered to you and so would many I believe did they

know I was writing. Mrs. Conner (?) is now with Mrs. Harding, and she takes

long walks to gather the autumn leaves. There are great fears entertained that

Col. Gentry is lost, as no one has heard

anything of him for some time, the last news was that he was flirting

desperately with Mrs. Greenhow, though it is kept a secret in deference to

Mary’s feelings. What a punishment it would be to her if the old campaigner

married him. Gen. Hardee passed through last night, he think that the army will

operate in middle Tennessee try to get ahead of Buell at Nashville, and then

try Kentucky again. He looks badly and so do all of the officers, but says the

army is in fine condition. How is Gen. Helm, you quite ignore him, have you

quarreled and separated and how long? I am sorry I have no printed copy of the

Tennessee song, but have written it for you, I wish someone would set it to

music. Good-bye write to me again when

you have time and inclination, for I hope we shall meet again, and tell me of

your movements so that I can reply. With much love truly yours

Phoebe Y. Pember

February 24, 2019

An Outtake: The Lincolns Meet the Strattons

During the editing of The First Lady and the Rebel, some sacrifices had to be made, and the following is one of them: a deleted scene where the Lincolns play host to Charles and Lavinia Stratton, better known as Mr. and Mrs. Tom Thumb. So here it is!

“You should wear pink more often,

Molly,” the President said. “It becomes you.”

Paying these sort of compliments was quite out of character for Mr. Lincoln, but then, the evening was very much out of character for him–and the entire war-weary Union. General Tom Thumb, Mr. P. T. Barnum’s Lilliputian wonder, had married the equally Lilliputian and arguably even more wondrous Miss Lavinia Warren on February 10, and for days, the war had been eclipsed by the small couple’s large nuptials, held in New York’s fashionable Grace Church with the cream of society in attendance. Afterward, the pair had held their reception at Mary’s favorite New York hotel, the Metropolitan. Mary had ordered a splendid pair of Chinese fire screens for the couple, but her contribution had paled beside those of ladies like Mrs. Vanderbilt, who gave a coral and gold brooch set, earrings, and studs, and Mrs. Roosevelt, who gave a 127-piece dinner set of porcelain and gold. But those ladies could not host the newlyweds at the White House, as Mary had most gladly agreed to do when Mr. Barnum, a steadfast Republican and supporter of the President, had suggested it.

Bob,

visiting from school but in a sulk over Mary’s continuing refusal to allow her

son to put himself in the way of being blown to pieces, loftily refused to

attend, but his friends the presidential secretaries did, looking jauntily

jaded as they strolled into the Green Room. Secretary of War Stanton was there,

looking so mild and cheerful that Mary barely recognized him. The Secretary of

the Treasury, Salmon Chase, arrived a bit early, all the better, Mary surmised,

for Miss Chase, his daughter, to sweep her skirts around to the best effect.

As

the President had noted, Mary, eschewing

mourning for the occasion, had worn a pink silk gown with a multitude of

flounces, while her consort wore a black suit, well cut, with white kid

gloves–an unfortunate color for his large hands, but one dictated by

fashion. Beside them was Tad, who though

willing to be guided by his older brother in many areas was not in this one. He

tugged at his father’s hand. “Pa! Do you think they’ll come in a little carriage,

pulled with little horses?”

The

President gave this thought, as he did to all of Tad’s questions. “I don’t

think so, Son. It wouldn’t be safe among all of the regular-sized carriages. I

imagine they’ll travel in the usual manner, with some adjustments for their

situation.”

Tad

nodded. “I guess that’s true.”

The

clock struck eight, and Edward flung open the door. “Mr. and Mrs. Charles

Stratton!”

Mr. and Mrs. Stratton entered. Mary had seen their photographs–they could be bought at any photographer’s studio, like those of the Lincolns–but she still was disposed to admire the couple’s chief charm: their proportionality, so that each was a miniature of a full-sized adult. Dressed in their wedding clothes–a broadcloth suit with a while silk vest and blue undervest for the groom, a white satin gown with a two-yard train for the bride, whose parure of diamonds caused her neck, ears, and wrists to glitter as she moved–the couple made their way at a stately pace toward the President, who had to bend to take their hands. “Mr. and Mrs. Stratton, I wish you much happiness in your union.” He then presented them to Mary, who rather to her chagrin did not have to bend much at all to greet her guests.

Tad

gave each spouse’s hand a hearty shake. “Delighted to make your

acquaintance,” he said. He titled his head toward Mary. “Mother, if

you were a little woman like Mrs. Stratton, you would look just like her.”

Miss

Chase gave a distinct titter, but Mary, considering that Mrs. Stratton was only

about twenty years of age, with an intelligent and engaging face and with a

fine head of dark hair that unlike Mary’s had no touches of gray, chose to take

Tad’s words as a compliment, which they certainly were. “Indeed, I think

you are right, Tad.” She smiled at Mrs. Stratton. “And I am of no

great height myself. I think you will agree that we small people depend very

much on our brains.”

Mrs.

Stratton laughed. “You are certainly right about that!”

“Tell me about your travels, Mr. Stratton,” the President prompted as the Strattons joined them on the couch, Tad making a great point of arranging their refreshments so as to be within easy reach. “Mrs. Lincoln wishes to go to Europe when we leave this place, and I have a hankering to see it myself.”

Mr.

Stratton, who had been touring since he was a small boy, happily obliged, and

Mary listened with some envy as he told of his meeting with Queen Victoria, who

had been in deep mourning since the death of her husband, Prince Albert, in

1861 and showed no inclination to come out of it. The President had written a

letter of condolence to her, which despite the regrettable occasion for it had

rather pleased Mary–imagine, being in a position to comfort royalty! “I

hope she will receive us when we tour Europe,” Mrs. Stratton said. “I

am sure she would enjoy seeing my husband again, and I of course have never met

her, as this will be my first time abroad.”

“I

am sure she will want to see the two of you, having taken so much interest in

Mr. Stratton as a lad,” Mary said. “Maybe you will be what draws her

out of her seclusion.”

“I daresay she loved Prince Albert dearly, but there is such a thing as excessive mourning,” Miss Chase said decidedly. “It is rather self-indulgent.”

December 19, 2018

Photo Wednesday: A Girl from an Album

For my photo Wednesday, here’s a photograph of an unnamed young girl from an album I own. Victorian photograph albums range from the simple to the elaborate–some even played music! Sadly, many have been broken up by photo dealers–understandably, as many albums are in poor condition, and selling photographs individually is often more profitable–but it’s great fun to look through the surviving ones.

December 12, 2018

My Small Mary Lincoln Gallery

As promised last week, I intend to keep this blog more active. Lately, on Facebook, I’ve been posting Victorian and Edwardian photographs from my collection on Wednesdays, so I shall start doing the same here.

Today, in honor of Mary Lincoln’s 200th birthday tomorrow, I am posting four images of her that I own. Although composite images of Mary with her husband and sons were created during her lifetime, Mary never sat for a photograph with her husband, as far as we know. It is often said that this was because Mary was self-conscious about the disparity in the couple’s heights, but this seems unlikely, as photographs of couples from this period often get around this by showing the man sitting and the woman standing. Perhaps the Lincolns, like a number of other couples from the period, simply never felt the need to have a joint photograph.

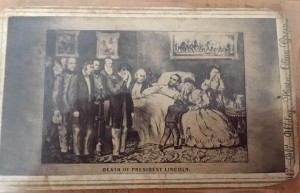

The third image depicts Mary in mourning for her son Willie, who died in the White House. The fourth is one of many depictions of Lincoln’s deathbed at the Petersen House across from Ford’s Theatre; like most, it contains a number of embellishments (such as the weeping Tad Lincoln, who was not at the house).

December 5, 2018

Update!

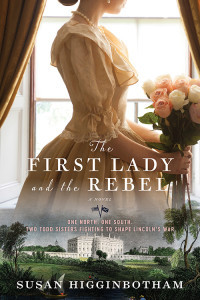

With apologies for not being here much lately, I do have some pleasing news: my seventh novel, The First Lady and the Rebel, about Mary Lincoln and her younger sister Emily Todd Helm, will be out in the fall of 2019! Stay tuned for ordering information. In the meantime, here’s the cover, which I hope you’ll like as much as I do:

I have been trying to think of ways of keeping this blog active, which has been difficult since working on my book has had to take priority, and will in the case of my upcoming books as well. So I’ve decided at least once a week, I will get on the blog to share a nineteenth-century photograph from my collection. I will also try to share more tidbits from my research, which now that The First Lady and the Rebel is in the hands of my publisher has been centering on the American abolitionist John Brown and his family (not to be confused with Queen Victoria’s attendant by the same name). So here’s to seeing more of you in the future!

August 13, 2018

The Strange, Sad Case of George B. Love

On April 21, 1865, as part of its coverage of President Lincoln’s assassination and its aftermath, the Washington Evening Star reported the arrival of the captured George Atzerodt in Washington. In addition, the Star noted that a man had been detained for questioning at Fort Thayer after repeatedly trying to break through the picket lines surrounding Washington. The man, however, would never be questioned. Instead, he took a penknife and slit his jugular vein.

The “mysterious suicide,” the Star concluded, must have been involved in the assassination plot. Such a supposition was not entirely unreasonable; after all, Ella Starr, John Wilkes Booth’s mistress, had attempted to kill herself days before, and Lewis Powell reportedly made a suicide attempt days later.

The next day, the Star reported the identity of the mysterious suicide: George B. Love, a hospital steward who had been dismissed from his post. Backing away somewhat from its original claim, the Star conceded that “mortification at his disgraceful position may have had something to do with his suicide.” Picked up by other newspapers, the story circulated around the country for a few days before fading into obscurity.

But the Star was not entirely mistaken. Whatever the cause of his tragic death, Love did have a connection to the assassination plot’s leading man, John Wilkes Booth.

George B. Love was born to James and Ann Love in Harford County, Maryland, on September 2, 1837. In 1850, he lived in Bel Air with his parents and four sisters; his father was a shoemaker. Not far from Bel Air, of course, was Tudor Hall, the home of the Booth family, and two of the Booth boys—Joseph and John—attended Bel Air Academy. A classmate, George Y. Maynadier, recalled in 1902 that George B. Love attended the school as well. Barely disguising the former pupil’s identity as “G__ L__,” Maynadier stated:

At the time when John Wilkes and Joseph A Booth were pupils at the Academy, there lived in Bel Air a family by the name of L___ (I do not for obvious reasons mention the name.) The eldest son, almost the age of John Wilkes Booth, was also a pupil at the Academy and intimate with the latter. He was likewise the most notorious of all the boys and young men at school or in the village, as the ringleader of everything desperate and reckless. In those days I was afraid of him, as all the smaller boys were, who often “tasted his specialty” in the shape of a cuff on the head or a punch in the ribs and so forth–consequently, it may be that he was not so desperate and bad as I thought him to be, but simply reckless and thoughtless of consequences.

Sometime after 1850, the Loves moved to Baltimore, where George’s parents would spend the rest of their lives. George’s sisters married men in maritime trades, while George became a druggist. (It would have been gratifying to report that he was a classmate of David Herold, a Georgetown College pharmacy student, but Georgetown records show no signs of George Love’s having studied at the institution.) On June 12, 1860, George married seventeen-year-old Caroline Jennings Starr in Baltimore’s Wesley Chapel. Carrie, as she was called, was the daughter of John Taylor Starr and the former Caroline Smith. John Taylor Starr appears to have been somewhat disreputable, at least in his youth; in January 1841, a chivalrous Baltimorean seized him after he insulted several young ladies in the street. After spending a week in jail, the penitent Starr, who was said to have been intoxicated at the time, was fined twenty dollars. By August 1848, he had separated from his wife, who took her three children, Carrie, Catherine, and Henry, and moved in with her mother.

On July 31, 1862, George, giving his address as 327 E. Monument Street in Baltimore, wrote to Brig. General William H. Hammond, Surgeon General of the United States, requesting an appointment as a hospital steward. Roberts Bartholomew, assistant surgeon, noted that the young man came highly recommended and advised his appointment, which was duly made on August 8, 1862. George was assigned to Camp Parole in Annapolis, a way station for Union soldiers who had been released from Confederate prisons. It was not a place for the faint-hearted. The former prisoners arrived in deplorable condition, suffering from starvation and disease, while the surrounding town was filled with rough characters and shady establishments. Among those who passed through the camp was one Boston Corbett, who spent a few days there in January 1865 before being returned to his regiment. Corbett would turn up at Garrett’s farm in Virginia on April 26, 1865, with fatal consequences for Booth.

George’s career proved to be a checkered one. In December 1863, he was court-martialed on charges of absence without leave, neglect of duty, and disobedience of order, all connected with an incident where he had left the camp on the evening of Saturday, September 19, 1863, and not returned until the morning of September 23, 1863, having apparently spent the time in Annapolis. In a rather convoluted statement provided to the court, George claimed that he had been ill with a fever during the time in question and that he had previously asked permission to leave camp, apparently to be with “my family only 2 miles distant who I have to protect & provide for.” He asked the court to “consider that all I have in the world is my character which has always been above reproach.” George, who had been employed in the camp dispensary, was found guilty on all specifications and was sentenced to forfeiture of one month’s pay and a reprimand.

In 1865, George found himself facing a second court-martial, this time on charges of “conduct prejudicial to good order and military discipline” and “breach of arrest.” The first specification claimed that on December 15, 1864, George demanded that the camp sutler, Jones and Crowley, pay him a percentage of his purchases of articles for the hospital. George was accused of having said, “I can starve the patients or overfeed them as I think proper, and I can make up to you in a month or even a week what you would give me. I have been accustomed to receive a percentage from those of whom I purchased articles for the hospital.” The sutler’s witnesses testified that George, explaining that his $400 salary was hardly enough to live on, had stated that his commission was usually five percent, but he would ask the sutler only for two and a half percent on its sales of such commodities as butter, eggs, crackers, oysters, mackerel, and milk.

The other three specifications claimed that on February 13, 15, and 16, 1865, George, having been placed under arrest, had stolen off to the city of Annapolis. There, testimony revealed, he had had the ill luck of being spotted by Colonel Adrian Root, the camp commander. As described by witnesses, his trips to town were hardly riotous; an ambulance driver testified that he had driven George to a store there on several occasions, then driven him back to camp.

Through his Baltimore lawyer, George mounted a vigorous defense. To the sutler’s testimony that he had asked for a percentage and that George had stopped dealing with the sutler after his request was refused, he offered evidence that the sutler had furnished inferior goods and that after complaints, George had begun buying supplies from a grocer in Annapolis, whom he had not asked for a percentage. To the charges of escape, he presented testimony from Steward Edward Von Myck, who had also testified for the government, that Von Myck, unfamiliar with Annapolis, had entreated George to accompany him there on several occasions prior to the ones for which he was charged. Von Myck testified that on their first excursion, George had gone inside Adams Express to ship a dead soldier’s goods; on the second, he had helped Von Myck transport a corpse; and on the third, he had shown Von Myck the grocer’s establishment with which the hospital was to deal.

Despite his lawyer’s efforts, George was found guilty of all charges. This time, on April 5, 1865, he was sentenced to be dishonorably discharged and to forfeit all pay that was due him. In addition, a notice of the conviction and sentence was to be inserted in his county of residence. The Baltimore Sun carried the notice on April 11.

After his discharge, George arranged with Adams Express on April 13 to send his trunk to John Taylor Starr, his father-in-law, in Baltimore; on April 18, he wrote a curt note, dated from Annapolis, requesting that Steward Von Myck send his valise to 257 N. Eden Street in Baltimore, the residence of John Taylor Starr. That same day, he left Annapolis. On April 19, clad in a new officer’s fatigue coat, gray pantaloons and vest, new underclothing “in double,” and fine calf boots, he made his attempt to break through the picket lines that ended in his arrest and suicide. His personal effects consisted of $320, his ill-used penknife, two Army discharges with conflicting information, a watch and chain, and a receipt from H. Stockbridge of Baltimore for legal services. Five feet ten, with light, curly hair and beard, small feet, and delicate hands, he was said, correctly, to have been an educated man.

What drove George to take his life remains a mystery. The most logical assumption is that despondent over his court-martial and the prospect of returning to his family in disgrace, he snapped. Still, other questions come to mind. Had the assassination of President Lincoln filled him with despair? Did he panic upon being detained, fearful that his connection with Booth would be discovered and implicate him in the assassination plot? Did he indeed possess some knowledge of the kidnapping or assassination conspiracy? After all, Booth had drawn two other school friends, Samuel Arnold and Michael O’Laughlen, into his web; it is possible that he tried to lure another. And why was George trying to break through the picket lines in the first place? Might he have been trying to commit “suicide by picket”? None of these questions are answerable, and it is possible, of course, that George’s death was caused by factors unknown to us. Maynadier, recalling the story in 1902, had no insight to offer, but simply commented that it was a “curious coincidence” that Love, as an old friend of Booth, should have acted as he did. “‘I tell the tale as ’twas told to me,’ is all the comment I have to make” was his coy conclusion.

In the end, though, the simplest explanation is probably the best. Not a year and a half before, George had written, “all I have in the world is my character”; now it must have seemed to the young man that he had lost everything.

But despite having left Camp Parole under a shadow, George was not without defenders there. After the Baltimore American mentioned George’s death and the suspicions surrounding him, D. R. Keigwin, a clerk at Camp Parole Hospital, wrote a letter to the editor:

In the American of this morning is a notice of the arrest and subsequent suicide of George B. Love; and the impression is conveyed that he was in some way concerned in the murder of our beloved President, or in the attempted murder of Secretary Seward.

Such was by no means the case, as he was in this hospital until Tuesday, April 18, as scores can testify, and he deplored the horrible tragedy, and could scarce find words to express his detestation of the horrid crime. He has been a hospital steward here for nearly three years, is a native of your city, and was greatly respected by the many who have known him here, and who read with sad hearts the news of his terrible, unexpected death.

May God in his mercy be near the wife and parents left to mourn his loss, and sustain them in this terrible bereavement.

The coincidence of Love’s in-laws and Booth’s mistress sharing the same surname—Starr—was not lost on another George, Lieutenant George P. Richardson, who on April 26 sent Colonel Olcott a newspaper clipping about Ella Starr’s suicide attempt along with the papers found on Love. The authorities do not seem to have found a connection between the various Starrs, however, and neither have I, although all hailed from Baltimore.

On April 25, George’s funeral was held at his father-in-law’s house at the North Eden Street address mentioned above. The notice of his death contained a poignant verse:

This languishing head is at rest,

Its thinking and aching are o’er;

His quiet, immovable breast,

Is heaved by affliction no more.

George was buried at Baltimore Cemetery. Located at the terminus of North Avenue, it is a few blocks from its much better-known neighbor, Green Mount Cemetery, to which the body of George’s school chum John Wilkes Booth would be moved in 1869. While Baltimore Cemetery contains a few elaborate memorials, it is by and large the preserve of those nineteenth-century Baltimoreans who labored with their hands. Still, its imposing, Gothic gate and upward slopes make the approach to the cemetery an impressive one, particularly now that its surrounding neighborhood is dingy and decayed.

Ann Love, George’s mother, died in July 1882 at the home of one of George’s sisters. James Love, who had spent the Civil War years in Baltimore’s police force, was employed in the House of Refuge, a home for delinquent boys, for many years before his death in 1899 at age eighty-eight. One wonders if his son’s troubled history influenced his later career.

After her husband’s death, Carrie, George’s widow, supported herself by working as a “tailoress,” along with her sister Kate. Around 1871, she married Robert A. Clarke, a widowed grocer with five children. A fervent Democrat who was active in local politics, Robert, who died in January 1914, was so determined to vote despite his illness toward the end of his long life that he had two friends carry him to the polls. Henry Starr, Carrie’s brother, served as one of Robert’s pallbearers. Carrie and Robert had one son, George R. Clarke, who worked as a clerk before his death at age twenty-nine in December 1900. As Robert already had a son named George W. Clarke from his first marriage, it seems likely that Carrie named her son in honor of her first husband.

On August 5, 1914, Carrie died at age seventy-three. The years had left her comfortably off: she had two houses, furniture, jewelry, and cash to distribute among her friends and relations. In Baltimore Cemetery, she and her husband Robert share a well-preserved tombstone, next to the weathered, barely legible marker of their son. Adjacent to George R. Clarke’s grave sits a third tombstone, which appears to have been erected about the same time as Robert and Carrie’s and likewise is in excellent repair. Inscribed “Asleep in Jesus,” it marks the grave of George B. Love, resting eternally near the bride of his happier days.

1850 U.S. census; tombstone of George B. Love.

Southern Aegis, March 7, 1902; Terry Alford, Fortune’s Fool, New York: Oxford University Press, 2015, pp. 209-10.

Baltimore Sun, July 18, 1860; 1860 and 1900 U.S. Censuses; Last Will and Testament of Robert Andre Clarke.

Baltimore Sun, January 4 and 11, 1841.

Baltimore Sun, August 22, 1848; 1850 U.S. census.

Letters Received by the Adjutant General, 1861-1870; Army Register of Enlistments, 1798-1914 (on fold3 database).

R. Rebecca Morris, A Low, Dirty Place: The Parole Camps of Annapolis, MD 1862-1865. Linthicum, Md.: Anne Arrundell County Historical Society, 2012, pp. 60, 62.

Scott Martelle, The Madman and the Assassin, Chicago Review Press, 2015, p. 57.

National Archives, RG 153, File No. NN-869.

National Archives, RG 153, File No. 00-509; Civil War: U.S. Army Civil War and Reconstruction Era Court Martial Records. Headquarters Middle Department, General Orders No. 68.

William C. Edwards and Edward Steers Jr., The Lincoln Assassination: The Evidence. Urbana and Chicago: The University of Illinois Press, 2009, p. 1101; Baltimore Sun, April 25, 1865.

Evening Star, April 21, 1865.

Baltimore American, April 23, 1865, reprinted in the New York Daily Herald, April 25, 1865.

Edwards and Steers, pp. 1100-01.

Baltimore City Paper, September 17, 2003, cited in http://www.germanmarylanders.org/ceme....

Baltimore Sun, July 31, 1882; Southern Aegis, February 24, 1899.

1870, 1880, 1900, and 1910 federal censuses; Woods’ Baltimore City Directory, 1867; Baltimore Sun, April 6, 1863, December 11, 1900, and January 18, 1914; death certificate of George R. Clarke.

Baltimore Sun, August 7, 1914; Will of Caroline J. Clarke.

[This was originally published in the Surratt Courier, August 2018.]

October 31, 2017

Guest Post by Sharon Bennett Connolly: Joan, Lady of Wales

I’m delighted to be hosting Sharon Bennett Connolly, a friend of mine and the author of Heroines of the Medieval World. Today Sharon shares with us an extract about Joan, Lady of Wales, a historical figure who’s fascinated me since I first learned about her.

Extract from Chapter 4: Scandalous Heroines about Joan, Lady of Wales

Following her father’s death in October 1216, Joan continued to work towards peace between Wales and England. She visited Henry in person in September 1224, meeting him in Worcester; Joan seems to have had a good relationship with her half-brother, evidenced by his gifts to her of the manor of Rothley in Leicestershire, in 1225, followed by that of Condover in Shropshire, in 1226. An extant letter to Henry III, addressed to her ‘most excellent lord and dearest brother’ is a plea for him to come to an understanding with Llywelyn. In the letter, Joan uses her relationship with Henry to try to ease the mounting tensions between the two men. She describes her grief ‘beyond measure’ that discord between her husband and brother had arisen out of the machinations of their enemies, and reassures her brother of Llywelyn’s affection for him. In the mid-1220s, Henry acted as a sponsor, with Llywelyn, in Joan’s appeal to Pope Honorius III to be declared legitimate; in 1226 her appeal was allowed on the grounds that neither of Joan’s parents had been married to others when she was born.

Joan and Llywelyn’s marriage appears to have been, for the most part, a successful one. Joan’s high-born status, as the daughter of a king, brought great prestige to Gwynedd. As a consequence, her household was doubled from four to eight staff, including a cook who could prepare Joan’s favourite dishes. Llywelyn seems to have valued his wife’s opinion; as we have seen, he often made use of her diplomatic skills and relationship with the English court and he often consulted her on other matters. Her influence extended to Welsh legal texts, which, from this period onwards, included French words. Joan’s position was strengthened even further by the arrival of her children. Sometime between 1212 and 1215, her son, Dafydd, was born; in 1220 he was recognised as Llywelyn’s heir by Henry III, officially supplanting his older, illegitimate, half-brother, Gruffudd, who was entitled to his father’s lands under Welsh law. The move received papal approval in 1222. As a result, in 1229 Dafydd performed homage to Henry III, as his father’s heir. A daughter, Elen, was probably born around 1210, as she was first married in 1222, to John the Scot, Earl of Chester. Her second marriage, in 1237 or 1238, was to Robert de Quincy. Joan may have been the mother to two more of Llywelyn’s daughters, Gwladus and Margaret, although they may have been the daughters of a mistress. Gwladus was married to Reginald de Braose. Her stepson, William (V) de Braose, was to play a big part in Joan’s scandalous downfall in 1230.

Joan’s life in the first quarter of the 13th century had been exemplary; she was the ideal medieval woman, a dutiful daughter and wife, whose marriage helped to broker peace, if an uneasy one, between two countries. She had fulfilled her wifely duties, both by providing a son and heir and being supportive of her husband to the extent that she should not be included in the roll call of scandalous women – however, in 1230, everything changed. William de Braose was a wealthy Norman baron with estates along the Welsh Marches. Hated by the Welsh, who had given him the nickname Gwilym Ddu, or Black William, he had been taken prisoner by Llywelyn in 1228, near Montgomery. Although he had been released after paying a ransom, de Braose had returned to Llywelyn’s court to arrange a marriage between his daughter, Isabella, and Llywelyn’s son and heir, Dafydd. During this stay, William de Braose was ‘caught in Llywelyn’s chamber with the King of England’s daughter, Llywelyn’s wife’.

William de Braose was publicly hanged, either at Crogan near Balsa, or possibly near Garth Celyn, on 2 May 1230. Joan, however, escaped with her life and was imprisoned in a tower at Llywelyn’s palace of Garth Celyn. We cannot say how long the affair had lasted, whether it was a brief fling in 1230, or had started when de Braose was a prisoner of Llywelyn in 1228. Joan’s position in the 1220s had appeared unassailable but this scandal rocked Wales, and England, to the core. She was no young girl struggling to come to terms with her position in life; she was about forty years old, had been Llywelyn’s consort for twenty-five years and had borne him at least two children when the affair was discovered. Contemporaries were deeply shocked at Joan’s betrayal of her husband; indeed, following this scandal, Welsh law identified the sexual misconduct of the wife of a ruler as ‘the greatest disgrace’. However, there was no question over the legitimacy of her children, who had been born at least fifteen years before. The most surprising thing about the whole affair, moreover, is Llywelyn’s response. His initial anger saw William de Braose hanged from the nearest tree, and Joan imprisoned in a tower. This rage, however vicious, was remarkably brief.

Maybe it was due to the strength of the previous relationship between Llywelyn and Joan, or maybe it was the high value placed on Joan’s diplomatic skills and her links with the English court; but within a year the terms of Joan’s imprisonment had been relaxed and just months after that, she was back on the political stage. Llywelyn appears to have forgiven her; the couple were reconciled and Joan returned to her life and position as Lady of Wales.

Sharon Bennett Connolly has been fascinated by history for over 30 years now and even worked as a tour guide at historical sites, including Conisbrough Castle. Born in Yorkshire, she studied at University in Northampton before working in Customer Service roles at Disneyland in Paris and Eurostar in London.

She is now having great fun, passing on her love of the past to her son, hunting dragons through Medieval castles or exploring the hidden alcoves of Tudor Manor Houses.

Having received a blog as a gift, History…the Interesting Bits, Sharon started researching and writing about the lesser-known stories and people from European history, the stories that have always fascinated. Quite by accident, she started focusing on medieval women. And in 2016 she was given the opportunity to write her first non-fiction book, Heroines of the Medieval World, which was published by Amberley in September 2017. She is currently working on her second non-fiction book, Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest, which will be published by Amberley in late 2018.

Links: Blog

Facebook

Twitter: @Thehistorybits

October 7, 2017

Guest Post: A New Mother by Melita Thomas

Good morning! I’m pleased to be hosting Melita Thomas, author of The King’s Pearl: Henry VIII and His Daughter Mary, on her blog tour. Today Melita, who runs the site Tudor Times, will be blogging about Mary’s relationship with Margaret, Countess of Salisbury. Over to Melita, and thanks for stopping by!

As well as Mary’s own beloved mother, Katharine of Aragon, she also had five step-mothers, and was emotionally close to at least two of them, but the greatest female influence in her youth, other than Katharine, was her governess, Lady Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury.

Margaret was of the highest blood in England, being the niece of King Edward IV, and thus the cousin of Katharine’s new mother-in-law, Elizabeth of York. Early in the reign of Henry VII, he had arranged for Margaret, with her dangerous Yorkist blood, to marry his loyal cousin, Sir Richard Pole. Sir Richard held a senior officer in the household of Katharine’s first husband, Prince Arthur, and the couple accompanied Katharine and Arthur to the Marches of Wales in 1501, remaining there until Arthur’s untimely death. Thus, Margaret became one of Katharine’s first, and longest-lasting, English friends.

Following Henry VIII’s accession and speedy marriage to Katharine, the new queen quickly brought her old friend, now widowed, to the court. It may well have been at Katharine’s urging that Henry granted Margaret’s petition to inherit her great-grandmother’s earldom of Salisbury. This inheritance made Margaret, now Countess of Salisbury, one of the greatest magnates in England. In 1516, she stood as godmother to Mary at the princess’ confirmation in a ceremony immediately following her baptism.

Lady Salisbury’s outlook was traditional and conservative. Places in her household were sought after for the daughters of the nobility and she spent much of her time in the usual pursuits of great landowners – arranging marriages for her children, endless litigation over landholdings and rigorous religious observance. Two of her sons, Henry, Lord Montagu, and Arthur Pole, were in the king’s circle of friends, while a third, Reginald, was educated, both at home and in Europe, at Henry’s expense. Lady Salisbury pulled off a dynastic coup with the wedding of her daughter, Ursula, to Lord Henry Stafford, heir to the Duke of Buckingham. Once duchess, her daughter would rank only after Queen Katharine, the French queen and Mary.

Reflecting her rank, impeccable reputation and character, and the affection in which Katharine held her, Lady Salisbury was appointed as governess some time before 1 May 1520, when Mary was just past her fourth birthday. It was Lady Salisbury who presided over Mary’s household whilst the king and queen were in France at the Field of Cloth of Gold. Whilst they were absent, Mary, at Richmond, received a visit from the council, headed by the Duke of Norfolk. They found her to be ‘right merry, and in prosperous health and state, daily exercising herself in virtuous pastimes’.

Margaret then had to prepare her charge for a visit from three envoys of the King of France, sent to check on the health of the princess, who was betrothed to his son, the Dauphin François. Mary was on her best behaviour, flanked by lords spiritual and temporal and a full suite of ladies, led by Lady Salisbury. This was Mary’s opportunity to demonstrate her careful training and Lady Salisbury must have had her heart in her mouth – if Mary behaved badly, her governess would be discredited. Fortunately, Mary was not a shy child and, with great aplomb, she welcomed her visitors,

‘with most goodly countenance, proper communication, and pleasant pastime in playing at the virginals, [so] that they greatly marvelled and rejoiced the same, her young and tender age considered.’

She then offered them strawberries, wafers and wine and Lady Salisbury could be satisfied that her training was paying off.

Within a year, however, Lady Salisbury had been removed from her post. The Duke of Buckingham, her daughter’s father-in-law, and probably the only man in England (not excluding Henry!) whom Margaret would have felt to be her equal, was accused of treason and executed. Margaret and her family were tainted by association – her son, Lord Montagu went off to the Tower, and her daughter, Ursula, now faced an uncertain future.

Over the following years, Henry relented towards Margaret’s family. Montagu was released, and in 1525, when Mary’s extensive new household was being formed to accompany her to the Welsh Marches, where she was to preside over the Council for Wales, just as Arthur had done, twenty-five years before, Lady Salisbury was re-installed as Lady Governess.

Together with the Bishop of Exeter, who was to be President of the Council, Lady Salisbury had overall responsibility for Mary. Amongst Mary’s other attendants were some of Lady Salisbury’s family – her granddaughter Katherine; her daughter-in-law Constance, and Constance’s daughter. Elizabeth.

Lady Salisbury had detailed instructions, headed with the following injunction:

‘First, principally, and above all other things, the Countess of Salisbury being Lady Governess, shall according to the singular confidence that the kings’ highness hath in her, give most tender regard to all such things as concern the person of the said princess, her education, and training in all virtuous demeanour.’

For the next eight years, Lady Salisbury supervised Mary’s every move. Religious practice formed a great part of daily life for everyone, and Lady Salisbury probably instituted the punctilious attendance at Mass that Mary followed for the rest of her life. Mary’s numerous visits whilst she was in the Marches to Worcester Cathedral are recorded in the Prior’s book, and he lists the gifts given by both Mary and Lady Salisbury – with rank being preserved by Mary offering more: two gold crowns for tapers at Candlemas 1526, compared with Lady Salisbury’s one.

Mary’s health, as the only legitimate child of the king, was a matter of deep concern. In April 1526, Lady Salisbury agreed with the Bishop, that none of the Princess’ councillors should be allowed into her presence, for fear of infection, which was raging. They were concerned that if the epidemic reached Hartlebury Castle, where Mary was currently housed, there would be nowhere for her to go, as infection had crept into her other houses at Tickenhill and Ludlow. In the face of the contagion, instructions were given for the Princess’ Council to make a monthly enquiry into her health – consulting Lady Salisbury and Mary herself.

It was an accepted part of noble education, that young women should be placed in the household of a lady of as high a rank as possible. In return for their service, the lady would supervise them, manage their education, take an interest in their marriages, and promote them where possible. Lady Salisbury’s supervision of Mary’s household was exemplary. She attended to every detail as is clear from a letter she wrote to Anne Rede, whose daughter was one of Mary’s attendants, regarding the young woman’s marriage. Lady Salisbury’s strictness and rectitude meant that, even after she ceased to be Mary’s governess, young women were still placed with her. Not for Mary the lax supervision that her half-sister, Elizabeth, encountered in her adolescence, ending with her good name being smirched by Sir Thomas Seymour.

In early 1528, it was decided that Mary should be recalled from the Marches to ‘reside near the king’s person’. Naturally, Lady Salisbury returned with her, but as the annulment case began to gather steam in 1528, Mary, who had been ill with small-pox, was again housed away from court with Lady Salisbury. We do not know when Mary was informed about her father’s attempts to have his marriage to her mother annulled, or who told her, but it might well have been Lady Salisbury.

From August 1531, Mary was parted from her mother, but Lady Salisbury was still in post, inculcating in Mary her own values of traditional religion, and a mixture of obedience to the king, and a determination to stand up for her rights – she was involved in an ongoing dispute with the king, over some of her landholdings. Her stubbornness in adhering to her rights (even though, legally, her position was questionable) may have influenced Mary.

Life proceeded as usual for Mary, other of course, than the stress produced by the knowledge of her mother’s unhappiness, and the ban on seeing Katharine, until the summer of 1533, when Mary and Lady Salisbury were at Newhall (or Beaulieu as it was also known) in Essex. A message came to Mary’s chamberlain, John, Lord Hussey, that he was to hand over Mary’s jewels to one of Mary’s ladies, Frances Aylmer, who was to deliver them to Thomas Cromwell, Master of the King’s Jewels.

Hussey took the order to Lady Salisbury, who immediately made difficulties. She claimed there was no inventory of the jewels, and it was as much as Hussey could do to get her to produce the items and inventory them herself in front of him, but she refused to hand them over to Frances Aylmer without an express warrant from the king. Hussey wrote to Cromwell, requesting further instructions as he could not override Lady Salisbury.

A royal command soon arrived, followed in late August by one for plate, both that of the king’s that Mary might hold, and her own. Mary’s Clerk of the Jewels showed that she did not have any belonging to the king – at least, there was none noted in the inventory he had agreed with his predecessor on coming into office. As for Mary’s own items of plate, Lady Salisbury claimed they were all necessary when Mary was ill.

Mary saw these delaying tactics, and learnt from them – whenever she received an order she did not like, she would reject it until she had had it in an express letter or warrant from the king.

Henry was angered by Lady Salisbury’s attitude. He probably expected that she should be more grateful to him – he had been very generous to her and to her family in the past. He was certain that her influence was leading Mary astray, and, after the birth of Elizabeth, he determined that Mary must be separated from her governess.

Orders came that Mary was to travel to Hatfield, to a subordinate position in Elizabeth’s retinue. Lady Salisbury, on being told that the household was to be broken up, offered to go with Mary and provide staff for the princess at her own expense. This offer was firmly rejected, and Mary was now separated from a woman whom she described to the ambassador, Eustace Chapuys, as her ‘second mother’.

Mary spent two and a half years in misery within Elizabeth’s household. All requests for her to be allowed to see either Katharine or Lady Salisbury were rejected, even when she was gravely ill. Indeed, Henry described Lady Salisbury as a ‘foolish woman’ who would not have been able to care for Mary in her ill-health as well as the newly-appointed Lady Shelton. A far cry from his reliance on Lady Salisbury’s care of his daughter ten years before.

It was not until she had finally capitulated in 1536 to Henry’s demands that she recognise that her parents’ marriage had been invalid and that she was illegitimate, that Mary was allowed to return to the court. Lady Salisbury’s whereabouts during the period is unknown, but shortly after Mary had acquiesced to Henry’s demands, she came to court and attracted a crowd of thousands. Henry, on asking why a crowd was forming, was told that they hoped to see Mary in company with her old governess.

Although it is likely that Mary saw Lady Salisbury whilst at court with Queen Jane Seymour, there is no record of a meeting. Mary was now permitted to choose her own attendants , but she was too wise to ask for the return of Lady Salisbury – perhaps also, aged twenty, she did not feel the need to put herself under the dominion of a governess again.

In later 1538, the countess was put under house arrest, and the following year incarcerated in the Tower of London. She was executed without trial on 27th May 1541. Again, there is no record of Mary’s reaction, but we can presume she was deeply upset at the news.

During her Mary’s own reign, Reginald, Lady Salisbury’s son, became her archbishop of Canterbury, and Lady Salisbury’s granddaughter, Katherine, mentioned above, was ‘restored in blood’.